Abstract

Nanoscale molecular transport governs mass diffusion and responsiveness in soft porous crystals, where guest adsorption induces host deformation and alters rigidity. Surface-mediated adsorption generates inhomogeneous adsorbate distributions, leading to spatial variations in stiffness—elastic heterogeneity—whose role in adsorption kinetics remains poorly understood. Here, we show that elastic heterogeneity governs adsorption kinetics, giving rise to size-dependent uptake, surface creasing, and anomalous dynamic scaling distinct from established scaling laws. Stress relaxation near corners accelerates adsorption, while on surfaces, creases emerge at flexible unadsorbed regions compressed between rigid adsorbed domains. The resulting lateral correlations of adsorbates exhibit a breakdown of scale invariance between global and local fluctuations. These findings provide a mechanistic foundation for controlling adsorption and deformation kinetics via elastic heterogeneity. Our work opens a route to engineering responsive materials, where mechanical feedback is harnessed to control cooperative molecular transport and drive macroscopic shape changes under external perturbations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transport phenomena govern the structure, dynamics, and function of systems spanning physics, chemistry, biology, and materials science1. Among these, mass transport plays a central role in processes ranging from droplet formation in biological cells2, ionic conduction in batteries3,4, hydrogen uptake in metals5, and solvent permeation in gels and soils6,7,8, to molecular diffusion in porous materials such as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)9,10,11,12,13. Designing materials with tunable responsiveness to external stimuli requires a fundamental understanding of the material parameters that regulate molecular transport14,15,16. Recent advances in quantum chemistry, molecular dynamics simulations, and continuum modelling have elucidated how host-guest interactions influence adsorption energetics and the dynamic response of the framework17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. However, although these approaches provide microscopic insight, building predictive theoretical frameworks that bridge molecular-scale mechanisms and macroscopic kinetics remains a major challenge. Cooperative transport among guest molecules, combined with local structural flexibility, gives rise to spatio-temporal heterogeneity in material properties, making the system intrinsically non-uniform. This non-uniformity leads to heterogeneous and size-dependent adsorption through surface-controlled uptake, as extensively observed in MOFs experimentally and numerically21,23,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Such adsorption behaviour leads to complex spatio-temporal dynamics and presents a major challenge for predicting and controlling uptake processes. Establishing physical principles to address such mesoscopic heterogeneity is therefore essential for engineering MOF-based devices with enhanced functionalities, including water harvesting33, catalysis34, sensors35, biomedicines36, and artificial molecular machines37.

One major origin of adsorption heterogeneity arises from the coupling between molecular uptake and the elastic responses of the host framework10,20,22,24. In soft porous crystals—mechanically flexible MOFs—strong host-guest interactions lead not only to substantial structural deformation but also to spatial variations in rigidity, referred to as elastic heterogeneity38,39,40. This mechanical heterogeneity gives rise to cooperative effects, which manifest as pattern formation, including domain formation and superlattice ordering, mediated by long-range elastic interactions in the host framework19,27,41. However, the impact of elastic heterogeneity on adsorption kinetics, in both bulk and near-surface regions, remains poorly understood.

To uncover the underlying principles governing heterogeneous adsorption kinetics, it is crucial to determine whether these dynamics obey universal scaling laws. Scaling concepts from interfacial growth phenomena42,43,44—such as swelling-deswelling in gels7,39,45,46 and epitaxial thin-film growth39,47,48—have revealed self-affine evolutions governed by elasticity and interfacial tension. Given that adsorption in soft porous crystals involves surface-mediated transport coupled to elastic stress, it is natural to explore whether similar scaling descriptions apply. Establishing such scaling laws would provide a unified framework for understanding how elastic heterogeneity and the resulting cooperative guest transport govern adsorption kinetics.

However, to extract scaling exponents, it is necessary to perform large-scale simulations of adsorption kinetics with statistically converged ensemble averaging. Because soft porous crystals consist of metallic nodes and organic linkers, molecular dynamics involving many unit cells remain computationally demanding19,21,23.

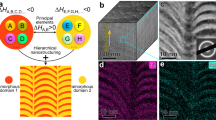

In this paper, we examine the scaling behaviour of adsorption kinetics in a soft porous crystal by performing dynamic Monte Carlo simulations on a coarse-grained lattice model (see Methods for details). The model captures the elastic deformation of soft porous crystals, as schematically illustrated in Fig. 1a. Each lattice site can adsorb at most one guest particle, and particles hop to adjacent sites while subject to excluded volume constraints. Adsorption occurs only from the bottom boundary, mimicking directional uptake. The model includes two key material parameters: the rigidity change factor K, and the lattice expansion ratio λ. Specifically, K > 1 and λ > 1 correspond to local lattice hardening and expansion upon adsorption, respectively. We mainly focus on the representative case of expansion and hardening, (K, λ) = (3, 1.4), where heterogeneous adsorption kinetics becomes pronounced, as schematically displayed in Fig. 1b. Under different parameter conditions, qualitatively distinct patterns are observed (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c). In the expansion and hardening case, three characteristic features are observed. The first one is size-dependent uptake. As shown in Fig. 1b, two major adsorption domains form at the bottom corners, whereas smaller domains appear along the surface away from the corners. Since the corner contribution to the overall uptake is larger in smaller systems, the uptake rate shows size dependence. Second, a creasing pattern is observed on the surface. The unadsorbed regions on the surface are sandwiched and compressed by harder adsorption domains, leading to the formation of elastic creases. Finally, the adsorption distribution exhibits a characteristic time evolution known as anomalous scaling. This anomalous scaling is distinct from superroughening and intrinsic anomalous scaling49,50. The adsorption kinetics depend sensitively on temperature T and adsorption chemical potential μ. The anomalous scaling is observed above the spinodal curve of the phase diagram, which is shown in Fig. 1c (see Methods for numerical details to obtain the phase diagram and Methods for the Landau theory). As described later, adsorption kinetics at the surface are classified using a dynamic scaling ansatz. The obtained scaling exponents for selected T and μ are displayed in Fig. 1c (Table 1 for details).

a The setup of molecular adsorption kinetics. Guest particles, represented by orange spheres, enter from the bottom boundary (y = 0), indicated by the magenta line. Lattice expansion and hardening occur due to interactions between the host matrix and guest particles. The other boundaries, represented by the green lines, do not allow the entrance and exit of particles, whereas stress relaxation occurs to satisfy stress-free boundary conditions. Inside the host matrix, guest particles move under the influence of other particles and the host’s elasticity. The interparticle interaction is governed by simple exclusion, where each matrix site can adsorb at most one guest particle. b Pattern formation and elastic creasing during adsorption in the spinodal region. Adsorbed (desorbed) regions are displayed in orange (grey). Molecular adsorption proceeds faster at the two bottom corners, whereas adsorption domains appear at the bottom surface. The domains at the corners grow both laterally and vertically as x* ~ t1/2 and h ~ t1/2, respectively. Unadsorbed regions between domains exhibit creasing to relax mechanical stresses with the correlation length ξ ~ t1/3. The domain morphology satisfies an anomalous dynamic scaling relation. c Thermodynamic phase diagram for (K, λ) = (3, 1.4) with respect to temperature T and adsorption chemical potential μ. The solid line represents the equilibrium phase boundary between the adsorbed and desorbed phases. The dashed lines represent the transition points under quasi-equilibrium simulations with increasing μ ( + μ) and decreasing μ ( − μ), exhibiting hysteretic behaviour. Dynamic scaling exponents (α, β, 1/z) for several (T, μ) are also displayed (Table 1).

Results

Nucleation and spinodal adsorption

The adsorption kinetics is classified into three distinct processes, as shown in Fig. 2. When the chemical potential μ is in the metastable region (I in Fig. 1c), nucleation-growth is observed: Adsorption domains at surfaces nucleate stochastically due to thermal fluctuations, and then the domains grow diffusively. Because the corner region can relax mechanical stress more easily than the surface region, corner nucleation occurs more frequently than surface nucleation. Thus, only the corner nucleation occurs when the chemical potential is far below the spinodal point, as shown in Fig. 2a, whereas surface nucleation also occurs when approaching the spinodal point, as shown in Fig. 2b (Supplementary Movies 1 and 2). Before nucleation occurs, the adsorption fraction nads(t) grows as nads(t) ~ tγ with γ < 1/2, because the nucleation is a stochastic event (see Methods for the definition of nads(t)). After the corner nucleation occurs, γ exhibits a crossover to 1 due to the domain growth in both the x and y directions with t1/2, as described in the next section (Supplementary Fig. 2).

a Snapshots at t = 16,000, 64,000, 128,000, 256,000 for (T, μ) = (0.1, 0.9). When the desorbed state is metastable, domain nucleation of adsorbates occurs at the corners, while adsorbed domains do not grow at the surface (Supplementary Movie 1). The red arrows point to nucleations at the corners and to a transient adsorption domain in the surface region. b Snapshots at t = 8000, 32,000, 64,000, 128,000 for (T, μ) = (0.1, 0.95). When the chemical potential approaches the spinodal point, surface nucleation also occurs (Supplementary Movie 2), as indicated by red arrows. c Snapshots at t = 4000, 8000, 32,000, 64,000 for (T, μ) = (0.1, 1.2). When the desorbed state is unstable, molecular adsorption exhibits a spinodal-type growth (Supplementary Movie 3). Adsorbed domains grow with a characteristic wavenumber. Because unadsorbed regions between adsorbed domains are softer, creases appear in the unadsorbed regions to reduce elastic energy, as indicated by red arrows. The parameters for all panels are: Lx = 192, K = 3.0, λ = 1.4.

Above the spinodal point (II in Fig. 1c), on the other hand, the desorbed state becomes linearly unstable, resulting in spinodal-type domain growth. Adsorption domain growth occurs both at the corners and on the surface. However, adsorption at the surface does not proceed homogeneously, as shown in Fig. 2c (Supplementary Movie 3). Coexistence of adsorbed and desorbed regions is observed. Because the desorbed sites have a smaller lattice size and are more flexible, they deform more easily than the adsorbed sites to reduce overall elastic energy, which results in the creasing of the host framework. As adsorption proceeds further, the adsorption domains merge into large clusters, and then the creasing points exhibit coarsening. In the supercritical region (III in Fig. 1c), the host’s elasticity is no longer the dominant factor, and the adsorption process becomes diffusion under simple exclusion. In the following, we focus on the spinodal growth, whose growth law and scaling properties are governed by elastic heterogeneity.

Here, it is worth noting that the morphology of the observed patterns depends on the simulation conditions and the model parameters (Supplementary Fig. 1d–f and Supplementary Movies 4–6), while the boundary condition does not affect qualitative features (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Adsorption distribution

For spinodal growth in Fig. 2c, the scaling properties of the adsorption fraction nads(t) can be understood by separating the contributions of the corner and surface growths. The time evolution of adsorption distribution along the x direction n(x; t) is displayed in Fig. 3a (see Methods for the definition of n(x; t)). In this figure, averages of 300 independent runs are taken. n(x; t) exhibits two peaks near the corners and a plateau in the central surface region. Although adsorption proceeds heterogeneously on the surface (Fig. 2c), the position of the creasing points (unadsorbed regions) is sample dependent, resulting in the smooth distribution of n(x; t). As time proceeds, the peak position of n(x; t) shifts inward, which results from the lateral growth of the corner domains.

a Spatial distribution of the adsorbed particle fraction with respect to x in adsorption processes. Averages of 300 independent simulation runs are taken. b The scaling plot \(\widetilde{n}(x{t}^{-1/2})=n(x;t){t}^{-1/2}\). c System size dependence of the adsorption fraction in adsorption processes. The solid curves represent Eq.(1), where A = 0.000831(16) and B = 0.000578(54) are obtained by the fitting of the Lx = 768 data. d Spatial distribution of the adsorbed particle fraction in desorption processes. e System size dependence of the adsorption fraction in desorption processes. The desorption decrease is slower than t1/2, which is shown by the solid curve. Different colours in (a, b, d) represent different times t and colours in (b, d) correspond to those shown in (a). Error bars in (a, b, d) are represented as shades. Different colours in (c, e) represent different system sizes Lx. Colours in panel e correspond to those in (c). The following parameters are used: K = 3.0, λ = 1.4, and T = 0.1. a–c are for μ = 1.2 (adsorption), while d, e are for μ = 0.3 (desorption). The system size is Lx = 768 in (a, b, d).

The contribution of the corner growth on nads(t) is quantified by a scaling plot \(\widetilde{n}(x{t}^{-1/2})={t}^{-1/2}n(x;t)\), which is shown in Fig. 3b. The collapse of \(\widetilde{n}(x{t}^{-1/2})\) for different t implies that both the peak height and position are scaled as t1/2. Hence, the contribution of the corner growth to nads(t) is proportional to t. \(\widetilde{n}(x{t}^{-1/2})\) increases steeply for xt−1/2 ≲ 0.4, so the length of the corner region x*(t) is defined as x*(t) = 0.4t1/2. Note that x*(t) does not depend on the horizontal system size Lx (Supplementary Fig. 4), implying that the corner contribution to nads(t) is proportional to t1/2 × 2x*(t)/Lx ~ t/Lx for x*(t) ≲ Lx/2. For x > x*(t), data collapse in Fig. 3b implies n(x; t) ~ t1/2 in the surface region. Hence, the surface contribution is proportional to t1/2 × (Lx − 2x*(t))/Lx for x*(t) ≲ Lx/2. Thus, the time dependence of nads(t) for x*(t) ≲ Lx/2 reads

where A and B are constants. Eq.(1) implies that guest adsorption becomes more efficient when Lx becomes smaller, which is confirmed in Fig. 3c. In the figure, nads(t) increases faster for smaller system sizes. The solid curve represents the fitting of nads(t) using Eq.(1) for the Lx = 768 data. The fitted curve agrees with the data for smaller Lx in the early stage, whereas deviation is observed when x*(t) becomes comparable to Lx/2. For x*(t) ≳ Lx/2, the domains at both corners interact with each other, resulting in the suppression of the lateral domain growth, whereas the growth in the y direction remains unaffected. Accordingly, nads(t) follows t1/2 at the late stage until the adsorbed domains reach the upper boundary (y = Ly). The time t*(Lx) at which Eq.(1) deviates from nads(t) is of the form \({t}^{* }({L}_{x})=c{L}_{x}^{2}\), which indicates \({x}^{* }({t}^{* })=0.4\sqrt{c}{L}_{x}\). By setting c = 0.65, t*(Lx) is calculated to be 24000 and 54000 for Lx = 192 and 288, respectively, showing a good agreement with those estimated from Fig. 3c.

The time evolution of x*(t) depends on thermodynamic parameters (T, μ). For larger μ, for example, x*(t)/t1/2 becomes larger, implying that the lateral domain growth at the corner becomes faster as μ increases. In the limit μ → ∞, the domains at both corners merge immediately, indicating that the contribution of the corner lateral growth (the second term of Eq.(1)) vanishes. Thus, the domain growth law for μ → ∞ is t1/2 (Supplementary Fig. 2). It is also worth noting that when deformation upon adsorption does not occur, i.e., K = 1 and λ = 1, lattice elasticity is irrelevant due to the absence of effective guest-guest interaction, resulting in diffusive growth t1/2 (Supplementary Fig. 5).

For desorption processes, the corner contribution exhibits a different tendency. Fig. 3d shows the spatial distribution n(x; t) in a desorption process. The desorption of guest particles is slower near the corners than in the surface region. As a result, nads(t) decreases slower than t1/2. This trend is enhanced for smaller system sizes, as shown in Fig. 3e. The opposite trend between adsorption and desorption kinetics arises from elastic heterogeneity, as explained by the Eshelby inclusion problem, a well-known concept in metallurgy38,39. In alloys, it has been shown that elastic energy is reduced when harder domains embedded in a softer matrix have an isotropic shape, whereas softer domains in a harder matrix prefer an anisotropic, flattened shape. Since the adsorbed sites are more rigid than desorbed sites, this argument also holds in our systems40,41. In the adsorption process, the adsorbed domains become isotropic, separated by unadsorbed narrow regions. Then, surface adsorption is slower than the corner adsorption when taking a statistical average. In the desorption process, on the other hand, the morphology of the desorbed domains becomes anisotropic, where desorbed sites form elongated, narrow channels, which penetrate into the bulk (Supplementary Fig. 1d and Supplementary Movie 4). Then, surface desorption is faster than the corner desorption when taking a statistical average. Thus, elastic heterogeneity is responsible for the asymmetry in the adsorption and desorption kinetics. Furthermore, the model parameters (K, λ) control the role of elastic heterogeneity. When the adsorbed sites become more flexible, i.e., K < 1, the adsorption-desorption kinetics remain asymmetric, but exhibit the opposite tendency (Supplementary Figs. 1e, f and 6, and Supplementary Movies 5 and 6).

Anomalous scaling

We now focus on the creasing formation in the surface region, as shown in Fig. 2c. By mapping the adsorption configuration onto the distribution along the x direction n(x; t) (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8, where n(x; t) from an individual run is displayed), the creasing pattern can be interpreted as the roughening of the n(x; t) profile. This roughness is characterised by three physical quantities: spatial correlation function C(ℓ; t), adsorption deviation W(ℓ; t), and the structure factor S(k; t) (see Methods for their definitions). These quantities are computed for each independent run and then averaged over 300 runs to evaluate the statistical properties of the spatial fluctuations of n(x; t). The dynamic scaling analysis yields the scaling exponents characterising heterogeneous adsorption: the roughness exponent α, the growth exponent β, the dynamic exponent z, the anomalous growth exponent \({\beta }^{{\prime} }\), the local roughness exponent αloc, and the spectral roughness exponent αs. The presence of \({\beta }^{{\prime} }\), αloc ( ≠ α), and αs indicates the anomalous scaling (see Methods for details). Scaling exponents obtained in this study are summarised in Table 1, where those in interfacial growth systems are also displayed for reference; Edwards-Wilkinson (EW) and Kardar-Parisi-Zhang (KPZ) models obey standard dynamic scaling, the linear molecular-beam-epitaxy model obeys superroughening, and the random diffusion model obeys intrinsic anomalous scaling42,43,49,51. Our model exhibits an anomalous scaling distinct from theirs, as described below.

It should be noted that n(x; t) in our model does not correspond to the height of an “interface” measured from the bottom boundary, whereas dynamic scaling analysis is conventionally applied to the interface of interfacial growth models such as EW and KPZ models. In the present study, a sharp interface cannot be clearly defined because of the presence of voids in the growing clusters and strong interactions between domains separated by these voids (Fig. 2c). Therefore, we employ n(x; t) as the relevant quantity for examining dynamic scaling.

The spatial correlation function C(ℓ; t) is presented in Fig. 4a. There are two notable features in C(ℓ; t). (i) C(ℓ; t) has a maximum at ℓ = ℓpeak(t), representing the typical distance between adsorbed domains and unadsorbed creases. As shown in Fig. 4b, the peak position is scaled as ℓpeak(t) ~ t1/z with 1/z = 0.321(17), which is close to 1/3. The growth law t1/3 is characteristic of mass-conserved ordering dynamics39. This suggests that the lateral coarse-graining of adsorbed domains is governed by the internal redistribution of adsorbed particles under effective attractive interactions arising from elastic heterogeneity. Therefore, we adopt z = 3 in the following. (ii) For sufficiently large ℓ, spatial correlation vanishes so that C(ℓ; t) converges to time-dependent plateau values Cplateau(t), which represent the variance of n(x; t). From Fig. 4b, Cplateau(t) ~ t2β with the growth exponent β = 0.392(1). The scaling relation α = βz yields α ≃ 1.176. The scaling function \(\widetilde{C}(\ell {t}^{-1/z})=C(\ell ;t){\ell }^{-2\alpha }\) reads

where the crossover length r* = ℓpeak(t)t−1/3 ≅ 0.345. \(\widetilde{C}(r)\) for r ≪ r* does not exhibit a plateau, indicating α < αloc. αloc satisfies the scaling relation \({\alpha }_{{\rm{loc}}}=(\beta -{\beta }^{{\prime} })z\simeq 0.426\), where \({\beta }^{{\prime} }=0.250(4)\) from Fig. 4b. For r ≲ 0.1, however, the slope slightly deviates from − 2(α − αloc). The deviation arises from the discreteness of our model, which becomes non-negligible below five lattice spacings (Supplementary Fig. 9). This effect reflects the fact that the morphology of small adsorption domains in the lattice model is strongly constrained by the underlying lattice structure40,41.

a Spatial correlation function C(ℓ; t) exhibits a maximum at ℓpeak(t) and a plateau Cplateau(t) for large ℓ. b Time evolution of ℓpeak(t), Cplateau(t), and C(1; t), obtained from the correlation function C(ℓ; t) shown in (a). They exhibit power-law behaviours, yielding the dynamic exponent 1/z = 0.319(18) ≃ 1/3, growth exponent β = 0.392(1), and anomalous growth exponent \({\beta }^{{\prime} }=0.250(4)\), respectively. The positive \({\beta }^{{\prime} }\) indicates anomalous dynamic scaling. Data in the interval [8000, 128000] are used for the fitting. c Scaling plot \(\widetilde{C}(\ell {t}^{-1/3})=C(\ell ;t){\ell }^{-2\alpha }\), where α = βz represents the global roughness exponent. d, Adsorption deviation W(ℓ; t). e Scaling plot \({\widetilde{W}}_{1}(t{\ell }^{-3})=W(\ell ;t){\ell }^{-\alpha }\) exhibits a crossover between distinct slopes β = 0.391(1) and \({\beta }^{{\prime} }=0.252(3)\) at tℓ−3 ≃ 24.4. f Another scaling plot \({\widetilde{W}}_{2}(\ell {t}^{-1/3})=W(\ell ;t){t}^{-\beta }\). Data collapse for ℓt−1/3 ≲ 0.1 yields the local roughness exponent αloc = 0.424(4), which corresponds to \((\beta -{\beta }^{{\prime} })z\). g, Structure factor S(k; t). h Scaling plot \(\widetilde{S}(k{t}^{1/3})=S(k;t){k}^{2\alpha +1}\) using the global roughness exponent α collapses for kt1/3 ≲ 1, whereas a plateau is observed at kt1/3 ~ 1. i Another scaling plot \(\widetilde{S}(k)=S(k;t){t}^{-2{\beta }^{{\prime} }}\) using the anomalous growth exponent \({\beta }^{{\prime} }\). The slope reads k−2α−1 for k ≲ 10−1, whereas deviation from both k−2α−1 and \({k}^{-2{\alpha }_{{\rm{loc}}}-1}\) is confirmed for k ≳ 10−1, though there is a good data collapse. Different colours in (a, c, d, f–i) represent different times t. Colours in panels without legends correspond to those shown in (a). Different colours in (e) represent different lengths ℓ. The parameters for all panels are: Lx = 768, K = 3.0, λ = 1.4, T = 0.1, and μ = 1.2.

Compelling evidence for anomalous scaling is obtained by examining the adsorption deviation W(ℓ; t), as shown in Fig. 4d–f. The scaling functions \({\widetilde{W}}_{1}(t{\ell }^{-z})={\ell }^{-\alpha }W(\ell ;t)\) and \({\widetilde{W}}_{2}(\ell {t}^{-1/z})={t}^{-\beta }W(\ell ;t)\) are displayed in Fig. 4e, f respectively. Good data collapse is confirmed, indicating the existence of scaling functions. From the figure, the scaling functions read

where the crossover points \({u}^{* }=t{\ell }_{{\rm{peak}}}^{-z}={({r}^{* })}^{-1/z}\cong 24.4\) and v* = r*. The growth and anomalous growth exponents are determined as β = 0.391(1) and \({\beta }^{{\prime} }=0.252(3)\) from Fig. 4e, and the local roughness exponent is determined as αloc = 0.424(4) from Fig. 4f, which agrees with those obtained by the scaling analysis for the correlation function.

It is known that αloc < 1 is a feature of intrinsic anomalous scaling (see Methods for details)49. However, the scaling of the structure factor S(k; t) shows a different behaviour. To see this, the time evolution of the structure factor is presented in Fig. 4g. The structure factor has a distinct peak, yielding the correlation length ξ = 1/kpeak. The peak corresponds to the peak of the spatial correlation function C(ℓ; t). In accordance with C(ℓ; t), the peak of the structure factor shifts to lower wavenumbers and its height increases with time. Therefore, we regard ℓpeak as the correlation length ξ. From the scaling arguments, the scaling function \(\widetilde{S}(k{t}^{1/z})={k}^{2\alpha +1}S(k;t)\) is given by

where w* = t1/z/ξ(t) = 1/r*50. As shown in Fig. 4h, \(\widetilde{S}(k{t}^{1/z})\) exhibits a plateau near kt1/z ~ 1, implying αs = α ≠ αloc. This feature is known for superroughening rather than intrinsic anomalous scaling, though αloc = 1 is required for superroughening. Thus, anomalous scaling in our model deviates from both intrinsic anomalous scaling and superroughening. It should be noted that the scaling plot \(S(k;t){t}^{-2{\beta }^{{\prime} }}\) at high wavenumbers (k ≳ 0.1) deviates from both −2α − 1 and −2αloc − 1, as shown in Fig. 4i. As in the case of C(ℓ; t), the deviation results from the discreteness of our model.

It is worth noting that the deviation of the scaling observed in our model from both intrinsic anomalous scaling and superroughening cannot be attributed to the time evolution of the length of the surface region. As long as the surface region is sufficiently longer than the correlation length ξ, the time dependence of the surface region does not alter the scaling behaviour except for S(k; t) at the low-wavenumber regime (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11).

The scaling exponents in Fig. 4 depend on (T, μ), as shown in Fig. 1c and Table 1 (Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13). Furthermore, with increasing T and μ, the scaling exponents exhibit a crossover to supercritical values β = 1/4 and 1/z = 0: no characteristic length scale exists. In this region, characteristic domain growth with elastic creasing does not occur because the adsorption chemical potential and thermal fluctuations are much greater than the elastic energy. In the crossover region between spinodal and supercritical regions, W(ℓ; t) cannot be scaled by any dynamic exponent, so that 1/z is not well-defined (Supplementary Fig. 12). It is also worth noting that the dynamical exponents depend on the simulation conditions and material parameters (K, λ), where the anomalous scaling does not necessarily hold (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 14).

Discussion

In this study, we identified two key features of molecular adsorption in soft porous crystals using a simple model incorporating elastic heterogeneity. First, surface effects enhance adsorption near corners due to local stress relaxation. This trend is consistent with experimental reports showing that surface and thin-film adsorption differ qualitatively from bulk behaviour28,29, resulting in size-dependent uptake25,32,52. Second, we observed anomalous adsorption scaling that deviates from both superroughening and intrinsic anomalous scaling. The anomalous scaling is characterised by scale separation between small and large length scales, resulting from cooperative adsorption-induced elastic creasing in the host framework. The inhomogeneous adsorption resembles simulation studies of MOFs using more realistic intermolecular potentials21,23. Thus, MOFs with large breathing transitions, which produce significant elastic stresses, are candidates for observing the creasing instability and anomalous scaling40. To validate our model and identify relevant materials, it will be essential to examine the relationship between changes in elastic properties—elastic moduli in particular—and molecular rearrangements in host frameworks upon adsorption using experimental techniques, quantum mechanical calculations, and molecular dynamics simulations.

From a macroscopic perspective, the creasing instability observed in this study is reminiscent of pattern formation in polymeric gels39,45 and of mechanical instability in electrochemical storage materials such as hydrogen-metal alloys and battery electrodes5,39,53. Solvent adsorption and desorption in gels, accompanied by swelling and deswelling, also exhibit asymmetric patterns due to underlying elastic heterogeneity39,45,46. However, the coarsening law in gels follows ξ ~ t1/2 (z = 2), and creasing sites are stiffer; in contrast, our results show z = 3 and indicate that creasing sites are more flexible. These differences may arise from (i) gel softening upon solvent uptake and (ii) solvent saturation, which occurs in gels but not necessarily in soft porous crystals. To systematically compare these systems, poromechanics theory under unsaturated solvent conditions offers a promising framework8. Despite these differences, continuum models of adsorption in soft porous crystals, polymeric gels, and electrochemical storage materials share a common Ginzburg-Landau framework: elastic deformation of the host matrix coupled to guest uptake, incorporating spatial inhomogeneity39. Extending continuum theories to soft porous crystals may therefore provide deeper insights into the macroscopic and surface instabilities common to a wide class of responsive materials.

Methods

Model Hamiltonian

A coarse-grained square-lattice model, which incorporates adsorption-induced lattice expansion/contraction and hardening/softening, is employed in our Monte Carlo simulations40. The model consists of the translational degrees of freedom of the lattice nodes, ri (i = 1, 2, …, Nhost), and the guest variable in each plaquette, σ□ (□ = 1, 2, …, N□) taking 1 (adsorbed) or 0 (desorbed). Nhost and N□ are the number of lattice nodes and plaquettes, respectively. Nhost = (Lx + 1)(Ly + 1) and N□ = LxLy. Each lattice node interacts with the nearest-neighbour (NN) and the next-nearest-neighbour (NNN) nodes. The NN and NNN elastic potentials of distance r are given by \(\frac{1}{2}{(1-r)}^{2}\) and \(\frac{1}{2}{(\sqrt{2}-r)}^{2}\) when a guest particle is absent around the lattice nodes. Hence, the elastic potential of the plaquette □ is given by \({V}_{1}({{\boldsymbol{r}}}_{i\in \square })=\frac{1}{4}{\sum }_{{\rm{NN}}}{(1-{r}_{ij})}^{2}+{\sum }_{{\rm{NNN}}}\frac{1}{2}{(\sqrt{2}-{r}_{ij})}^{2}\), where ri∈□ represents the positions of lattice nodes composing the plaquette □. To incorporate the lattice expansion/contraction and hardening/softening, we add an elastic potential \({V}_{2}({{\boldsymbol{r}}}_{i\in \square })=k[\frac{1}{4}{\sum }_{{\rm{NN}}}{(1+\zeta -{r}_{ij})}^{2}+{\sum }_{{\rm{NNN}}}\frac{1}{2}{(\sqrt{2}(1+\zeta )-{r}_{ij})}^{2}]\) when the guest particle is accommodated in the plaquette. Thus, the Hamiltonian is given by

where μ is the chemical potential for the guest particle adsorption. μ depends on the guest-host interaction energy and the gas pressure of guest particles. When the plaquette is occupied by a guest particle, the elastic potential of the plaquette reads \({V}_{1}+{V}_{2}=K[\frac{1}{4}{\sum }_{{\rm{NN}}}{(\lambda -{r}_{ij})}^{2}+{\sum }_{{\rm{NNN}}}\frac{1}{2}{(\sqrt{2}\lambda -{r}_{ij})}^{2}]+{\mu }_{c}\), where λ = 1 + kζ/(1 + k) is a lattice expansion (λ > 1) or contraction (0 < λ < 1) parameter, K = 1 + k is a lattice hardening (K > 1) or softening (0 < K < 1) parameter, and μc = 3K(λ−1)2/(K − 1) is the equilibrium adsorption-desorption transition point at T = 0.

In our model, the chemical potential μ is spatially uniform and does not impose any site-dependent bias inside the host lattice. Guest dynamics inside the host framework are dictated solely by the elastic interactions arising from the host’s deformation and exclusion effects between guest particles (see method of dynamic Monte Carlo simulations). The effect of μ arises only at the entrance/exit boundary (see Fig. 1a).

Ensemble

For simulating a system in which the entire volume V is changed by guest adsorption, an osmotic ensemble is employed40,54. Control parameters in this ensemble are the temperature T, the chemical potential of guest particles μ, the number of nodes Nhost, and external mechanical pressure P. Gas pressure of guest particles is related to the chemical potential through the equation of state. However, by applying external force in addition to the gas pressure, we can treat μ and P as independent variables. The osmotic grand potential is defined as Ω = U − TS + PV − μNads, where U is the internal energy, S is the entropy, and Nads is the number of adsorbed particles. In the differential form, dΩ = − SdT + VdP − Nadsdμ + μhostdNhost, where μhost is the chemical potential of the host framework. We fix P = 0 for our convenience. In this study, particle adsorption proceeds from the bottom boundary; the density of guest particles becomes heterogeneous during the adsorption kinetics. Then, the bottom boundary is more swelled (contracted) than the top boundary when λ > 1 (λ < 1). To avoid the numerical difficulties arising from the lattice mismatch between the bottom and top boundaries, the open boundary condition, rather than the periodic boundary condition, is adopted.

Phase diagram

To obtain the phase diagram in Fig. 1c, we adopt a periodic boundary condition to reduce the surface effect, which alters the nature of the transition. When the periodic boundary condition is imposed, an additional degree of freedom, average swelling ratio a, is necessary to incorporate the dynamical change of the entire volume. Then the system volume is represented as V = aLxLy. Unit Monte Carlo step (MCS) consists of one Metropolis sweep for guest particles {σ□} and L-times Metropolis sweeps for lattice sites {ri}, and L-times Metropolis updates for the average swelling ratio a. The updates of ri and a are restricted to ∣Δri∣ < 0.1 and Δa < 0.01, respectively. The system size Lx = Ly = 24 is adopted.

The spinodal curves are obtained by standard Monte Carlo simulations for μ-increasing/decreasing with a change in chemical potential Δμ = 0.01 every 2 × 104 MCSs. Then, the hysteretic adsorption and desorption transitions are observed. Because metastable states are robust against thermal fluctuations, we regard each transition point as the spinodal point40.

Multicanonical Monte Carlo simulation is utilised to obtain the thermodynamic equilibrium phase boundary. Here, the Wang-Landau method is applied, which efficiently samples the density of energy states g(E)55,56. By adopting the weight proportional to e−g(E), all the energy states, including those which are rarely realized in canonical ensembles, are uniformly sampled. We obtain the energy histogram H(E) by multicanonical Monte Carlo simulation. Then, the equilibrium probability distribution of the energy at each temperature T is computed as P(E) = H(E)e−E/T+g(E)/∑EH(E)e−E/T+g(E). The equilibrium phase transition point is determined as the temperature at which an equally weighted double-peak probability distribution is realised.

Dynamic Monte Carlo simulations

We perform dynamic Monte Carlo simulations to study adsorption-desorption kinetics. The unit MCS during adsorption simulations consists of Nhost × Lx updates for lattice site positions and N□ updates for guest variables. In the former, a lattice node position ri and its trial position \({{\boldsymbol{r}}}_{i}^{{\prime} }={{\boldsymbol{r}}}_{i}+\Delta {\boldsymbol{r}}\) are randomly chosen, where ∣Δr∣ < 0.1 and bond intersection is rejected to preserve the square lattice configuration. The acceptance is determined by the Metropolis rule. In the latter, a plaquette □ and its neighbour \({\square }^{{\prime} }\) are randomly selected. The Kawasaki dynamics is adopted56, where a trial exchange of □ and \({\square }^{{\prime} }\) is evaluated under the Metropolis rule with the energy change \(({\sigma }_{{\square }^{{\prime} }}-{\sigma }_{\square })({V}_{2}(\{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}_{i\in \square }\})-{V}_{2}(\{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}_{i\in {\square }^{{\prime} }}\}))\), which is not affected by the chemical potential μ. If the plaquette □ is on the bottom boundary, a trial step also includes particle entrance/exit through the boundary. If particle entrance/exit is selected, σ□ is updated using the Metropolis rule with an energy change ΔE = (2σ□ − 1)[V2({ri∈□}) − μ], otherwise, the Kawasaki dynamics is adopted in the same manner as above. Before performing adsorption simulations, 48,000 single lattice-site updates are conducted to realise initial equilibrium states. The vertical system length is fixed to Ly = 48. For each parameter, 300 independent simulation runs are conducted to obtain their sample averages.

Adsorption distribution and correlation functions

The adsorption fraction and distribution are defined by nads(t) = (1/N□)∑□σ□(t) and n(x; t) = (1/Ly)∑yσ□(t), respectively. nads(t) in all figures are averaged over 300 independent runs. n(x; t) in Fig. 3, Supplementary Figs. 4 and 6 are averaged over 300 independent runs, whereas n(x; t) for a single run is displayed in Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8.

To quantify the inhomogeneity of n(x; t), the spatial correlation function C(ℓ; t), the adsorption deviation W(ℓ; t), and the structure factor S(k, t) are calculated. They are defined by

where ∑x is the summation over the surface region x*(t) < x < Lx − x*(t) − ℓ, ℓsurf(t) = Lx − 2x*(t) is the surface length unaffected by corner adsorption, \({\langle n(x;t)\rangle }_{\ell }={\sum }_{{x}^{{\prime} }=0}^{\ell }n(x+{x}^{{\prime} };t)/(\ell +1)\) denotes a segmental average, and \(\widetilde{n}(k;t)={\sum }_{x={x}^{* }(t)}^{{L}_{x}-{x}^{* }(t)}\Delta n(x;t){e}^{2\pi ikx}/\sqrt{{\ell }_{{\rm{surf}}}+1}\) is the Fourier transform of the adsorption distribution with \(\Delta n(x;t)=n(x;t)-{\sum }_{x={x}^{* }(t)}^{{L}_{x}-{x}^{* }(t)}n(x;t)/({\ell }_{{\rm{surf}}}(t)+1)\).

Dynamic scaling

Interfacial growth systems often exhibit self-affinity, meaning that interfacial fluctuations are statistically invariant under anisotropic scale transformations42,43. More precisely, under a lateral scale transformation x → bx, the interfacial fluctuation Δn(x; t) is rescaled as Δn → bαΔn. α is called the roughness exponent, restricted to α < 157. Since the time evolution must remain invariant under this transformation, the time t is rescaled as t → bzt, where z is called the dynamic exponent. Accordingly, under a temporal scale transformation \(t\to {b}^{{\prime} }t\), the lateral length scale and the interfacial fluctuation are rescaled \(x\to {b}^{{\prime} 1/z}x\) and \(\Delta n\to {b}^{{\prime} \beta }\Delta n\), respectively, where β = α/z is called the growth exponent. Thus, the scaling form of Δn reads \(\Delta n(x;t)={b}^{-\alpha }\Delta n(bx;{b}^{z}t)={b}^{{\prime} -\beta }\Delta n({b}^{{\prime} 1/z}x;{b}^{{\prime} }t)\). In experiments and numerical simulations on interfacial growth, these exponents are extracted from the dynamic scaling of C(ℓ; t), W(ℓ; t), and S(k, t), which are defined in Eqs. (7)–(9). The scaling forms are given by

All scaling functions, \(\widetilde{C}\), \({\widetilde{W}}_{1}\), \({\widetilde{W}}_{2}\), and \(\widetilde{S}\), are also characterised by α, β and z. Typical examples that exhibit self-affinity are the Edwards-Wilkinson58 and Kardar-Parisi-Zhang (KPZ) models59, whose scaling exponents are listed in Table 1.

However, self-affinity does not necessarily hold49,50. For example, an experiment on fluid imbibition into a porous medium reports anomalous scaling, in which local (short length scale) and global (large length scale) interfacial fluctuations are characterised by different roughness exponents60. In such cases, the global roughness exponent α is not restricted to α < 1. Anomalous scaling is characterised by three additional scaling exponents50: local roughness exponent αloc < α, anomalous growth exponent \({\beta }^{{\prime} } > 0\), and spectral roughness exponent αs, satisfying the scaling relation \({\alpha }_{{\rm{loc}}}=z(\beta -{\beta }^{{\prime} })\). αloc and \({\beta }^{{\prime} }\) appear in \(\widetilde{C}\) and \(\widetilde{W}\), whereas αs appears in \(\widetilde{S}\), as shown in Eqs. (2)–(5). Standard dynamic scaling is recovered when αloc = α, \({\beta }^{{\prime} }=0\) and αs = α. The anomalous scaling has been classified into superroughening and intrinsic anomalous scaling49. Superroughening is characterised by αloc = 1 and α > 1. The structure factor exhibits the ordinary scaling, i.e., αs = α. It is realised for a system possessing conservation laws51, such as the linear molecular beam epitaxy model61,62,63,64. In the case of intrinsic anomalous scaling, the local exponent αloc is directly linked to the spectral roughness exponent αs, i.e., αloc = αs. The local exponent takes αloc < 1 and α can take any value. It is realised for systems having nonlocality or quenched disorder51, e.g., the random diffusion model49, the fractional KPZ model with long-range spatially correlated noise65, and a fluid imbibition experiment60.

However, as shown in the main text, αloc < 1 < α and αs = α are realised in our model. Thus, adsorption kinetics in our model exhibits anomalous scaling distinct from both superroughening and intrinsic anomalous scaling.

Landau theory of adsorption transition coupled to elasticity

To understand the adsorption-desorption transition with hysteresis in Fig. 1c, it is convenient to construct a Landau free energy of the adsorption fraction ϕ (nads in the main text) coupled with elastic deformation. For this purpose, spatial inhomogeneity is not incorporated. Using the lattice displacement vector u, the elastic strains in two dimensions reade1=∇ ⋅ u, e2=∇xux− ∇yuy, and e4=∇xuy+∇yux. e1 is the volumetric strain, and e2 and e4 are the shear strains. In the absence of direct interactions between adsorbates, the Landau free energy reads

where \({f}_{0}(\phi )={k}_{{\rm{B}}}T[\phi \ln\phi +(1-\phi )\ln(1-\phi )]\) is the translational entropy of the adsorbates, μ is the adsorption chemical potential (not to be confused with the total chemical potential), and η represents the coupling between lattice deformation and molecular adsorption. η > 0 for the expansion case, and η < 0 for the contraction case. \({f}_{{\rm{el}}}(\phi ,e)=\frac{K(\phi )}{2}{e}_{1}^{2}+\frac{G(\phi )}{2}({e}_{2}^{2}+{e}_{4}^{2})\) is the isotropic elastic energy, where K is the bulk modulus and G is the shear modulus. By incorporating adsorption-induced lattice hardening/softening, the elastic coefficients K and G depend on ϕ as K = K0 + K1ϕ and G = G0 + G1ϕ. Under the mechanical equilibrium condition with stress-free boundary conditions, the space average of the free energy variation with respect to the elastic tensor vanishes, which yields 〈Ge2〉 = 〈Ge4〉 = 0, and 〈e1〉 = η〈ϕ/K〉.

When the system is at chemical and mechanical equilibrium, ϕ and e become homogeneous; hence, the Landau free energy reads

by eliminating the elastic field. The last term describes the attractive guest-guest interaction due to the presence of η. The chemical equilibrium is given by df/dϕ = 0, which reads

We consider three cases: (i) η = 0, that is, lattice expansion/contraction does not occur. The left-hand side increases monotonically with ϕ, yielding ϕ = 1/(1 + e−βμ) without a phase transition (Supplementary Fig. 5). (ii) η ≠ 0 and K1 = 0. Due to the second term, the l.h.s. does not increase monotonically when η2≥4kBTK, resulting in the appearance of a phase transition regardless of the sign of η. (iii) η ≠ 0 and K1 ≠ 0. The sign of the third term depends on the sign of K1. The elasticity-mediated attractive interaction is enhanced for K1 < 0, whereas it is suppressed for K1 > 0; thus, when adsorbed sites are more flexible than desorbed sites, they form a spatially connected cluster (Supplementary Fig. 1e), whereas adsorbed domains are separated by unadsorbed regions when adsorbed sites are more rigid (Fig. 2c).

It should be noted that, in general, the thermodynamic phase diagram does not necessarily correspond to the instability upon molecular adsorption through the surface, because the shear deformation near the surface is also important66. In the present study, however, the shear modulus and bulk modulus show the same dependence on adsorption fraction. Then the difference in macroscopic instability and surface instability points is negligible.

Thus, the Landau free energy without spatial inhomogeneity can describe the thermodynamic adsorption-desorption transition. However, it does not account for the adsorption kinetics we have investigated in this study. A detailed analysis of the Ginzburg-Landau free energy, incorporating spatial inhomogeneity, would offer deeper insights into the physical origin of the anomalous dynamic scaling discussed in the main text.

Data availability

Input files to generate all of the figures are openly available at GitHub (https://github.com/kmitsumoto51/mof_kinetics). All other raw and processed data generated during this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

The computer codes used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Mehrer, H.Diffusion in Solids: Fundamentals, Methods, Materials, Diffusion-controlled Processes (Springer Science & Business Media, 2007).

Lee, D. S., Wingreen, N. S. & Brangwynne, C. P. Chromatin mechanics dictates subdiffusion and coarsening dynamics of embedded condensates. Nat. Phys. 17, 531–538 (2021).

Mukhopadhyay, A. & Sheldon, B. W. Deformation and stress in electrode materials for Li-ion batteries. Prog. Mater. Sci. 63, 58–116 (2014).

Yabuuchi, N., Kubota, K., Dahbi, M. & Komaba, S. Research development on sodium-ion batteries. Chem. Rev. 114, 11636–11682 (2014).

Alefeld, G. & Völkl, J. (eds.) Hydrogen in Metals I (Springer, 1978).

Li, Y. & Tanaka, T. Phase transitions of gels. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 22, 243–277 (1992).

Doi, M. Gel dynamics. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 78, 052001 (2009).

Coussy, O.Mechanics and Physics of Porous Solids (John Wiley & Sons, 2010).

Mitra, S., Sharma, V. K. & Mukhopadhyay, R. Diffusion of confined fluids in microporous zeolites and clay materials. Rep. Prog. Phys. 84, 066501 (2021).

Horike, S., Shimomura, S. & Kitagawa, S. Soft porous crystals. Nat. Chem. 1, 695–704 (2009).

Horike, S., Umeyama, D. & Kitagawa, S. Ion conductivity and transport by porous coordination polymers and metal–organic frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 2376–2384 (2013).

Furukawa, H., Müller, U. & Yaghi, O. M. "Heterogeneity within order” in metal-organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 3417–3430 (2015).

Lim, D.-W. & Kitagawa, H. Proton transport in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 120, 8416–8467 (2020).

Krishna, R. Diffusion in porous crystalline materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 3099–3118 (2012).

Kärger, J., Ruthven, D. M. & Theodorou, D. N. Diffusion in Nanoporous Materials (Wiley-VCH, 2012).

Coudert, F.-X. Recent advances in stimuli-responsive framework materials: Understanding their response and searching for materials with targeted behavior. Coord. Chem. Rev. 539, 216760 (2025).

Odoh, S. O., Cramer, C. J., Truhlar, D. G. & Gagliardi, L. Quantum-chemical characterization of the properties and reactivities of metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 115, 6051–6111 (2015).

Guyer, R. A. & Kim, H. A. Theoretical model for fluid-solid coupling in porous materials. Phys. Rev. E 91, 042406 (2015).

Jawahery, S. et al. Adsorbate-induced lattice deformation in IRMOF-74 series. Nat. Commun. 8, 13945 (2017).

Gor, G. Y., Huber, P. & Bernstein, N. Adsorption-induced deformation of nanoporous materials—a review. Appl. Phys. Rev. 4, 011303 (2017).

Rogge, S. M., Waroquier, M. & Van Speybroeck, V. Unraveling the thermodynamic criteria for size-dependent spontaneous phase separation in soft porous crystals. Nat. Commun. 10, 4842 (2019).

Kolesnikov, A. L., Budkov, Y. A. & Gor, G. Y. Models of adsorption-induced deformation: ordered materials and beyond. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 34, 063002 (2022).

Schaper, L. & Schmid, R. Simulating the structural phase transitions of metal-organic frameworks with control over the volume of nanocrystallites. Commun. Chem. 6, 233 (2023).

Kolesnikov, A. L., Shkolin, A. V., Men’shchikov, I. E. & Gor, G. Y. Kinetics of adsorption-induced deformation of microporous carbons. Langmuir 40, 23806–23815 (2024).

Sakata, Y. et al. Shape-memory nanopores induced in coordination frameworks by crystal downsizing. Science 339, 193–196 (2013).

Kärger, J. et al. Microimaging of transient guest profiles to monitor mass transfer in nanoporous materials. Nat. Mater. 13, 333–343 (2014).

Cho, H. S. et al. Extra adsorption and adsorbate superlattice formation in metal-organic frameworks. Nature 527, 503–507 (2015).

Sakaida, S. et al. Crystalline coordination framework endowed with dynamic gate-opening behaviour by being downsized to a thin film. Nat. Chem. 8, 377–383 (2016).

Hosono, N., Terashima, A., Kusaka, S., Matsuda, R. & Kitagawa, S. Highly responsive nature of porous coordination polymer surfaces imaged by in situ atomic force microscopy. Nat. Chem. 11, 109–116 (2019).

Delen, G., Monai, M., Meirer, F. & Weckhuysen, B. M. In situ nanoscale infrared spectroscopy of water adsorption on nanoislands of surface-anchored metal-organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 1620–1624 (2021).

Yamada, E. et al. Three-dimensional visualization of adsorption distribution in a single crystalline particle of a metal-organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 9181–9190 (2024).

Watanabe, S. et al. Size-dependent guest-memory switching of the flexible and robust adsorption characteristics of layered metal-organic frameworks. Sci. Adv. 10, eadr1387 (2024).

Hanikel, N. et al. Evolution of water structures in metal-organic frameworks for improved atmospheric water harvesting. Science 374, 454–459 (2021).

Bavykina, A. et al. Metal–organic frameworks in heterogeneous catalysis: Recent progress, new trends, and future perspectives. Chem. Rev. 120, 8468–8535 (2020).

Kreno, L. E. et al. Metal-organic framework materials as chemical sensors. Chem. Rev. 112, 1105–1125 (2012).

Horcajada, P. et al. Metal-organic frameworks in biomedicine. Chem. Rev. 112, 1232–1268 (2012).

Danowski, W. et al. Unidirectional rotary motion in a metal–organic framework. Nat. Nanotech. 14, 488–494 (2019).

Eshelby, J. D. The determination of the elastic field of an ellipsoidal inclusion, and related problems. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 241, 376–396 (1957).

Onuki, A. Phase Transition Dynamics (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Mitsumoto, K. & Takae, K. Elastic heterogeneity governs asymmetric adsorption-desorption in a soft porous crystal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2302561120 (2023).

Mitsumoto, K. & Takae, K. Adsorption superlattice stabilized by elastic interactions in a soft porous crystal. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, L012029 (2024).

Krug, J. & Spohn, H. Kinetic Roughening of Growing Surfaces. In Godrèche, C. (ed.) Solids Far From Equilibrium, 479–582 (Cambridge University Press, 1991).

Barabási, A.-L. & Stanley, H. E.Fractal Concepts in Surface Growth (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Takeuchi, K. A. & Sano, M. Evidence for geometry-dependent universal fluctuations of the Kardar-Parisi-Zhang interfaces in liquid-crystal turbulence. J. Stat. Phys. 147, 853–890 (2012).

Tanaka, T. et al. Mechanical instability of gels at the phase transition. Nature 325, 796–798 (1987).

Matsuo, E. S. & Tanaka, T. Patterns in shrinking gels. Nature 358, 482–485 (1992).

Politi, P., Grenet, G., Marty, A., Ponchet, A. & Villain, J. Instabilities in crystal growth by atomic or molecular beams. Phys. Rep. 324, 271–404 (2000).

Aqua, J. N., Berbezier, I., Favre, L., Frisch, T. & Ronda, A. Growth and self-organization of SiGe nanostructures. Phys. Rep. 522, 59–189 (2013).

López, J. M., Rodríguez, M. A. & Cuerno, R. Superroughening versus intrinsic anomalous scaling of surfaces. Phys. Rev. E 56, 3993–3998 (1997).

Ramasco, J. J., López, J. M. & Rodríguez, M. A. Generic dynamic scaling in kinetic roughening. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 2199–2202 (2000).

López, J. M., Castro, M. & Gallego, R. Scaling of local slopes, conservation laws, and anomalous roughening in surface growth. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 166103 (2005).

Krause, S. et al. The effect of crystallite size on pressure amplification in switchable porous solids. Nat. Commun. 9, 1573 (2018).

Cogswell, D. A. & Bazant, M. Z. Coherency strain and the kinetics of phase separation in LiFePO4 nanoparticles. ACS Nano 6, 2215–2225 (2012).

Coudert, F.-X., Jeffroy, M., Fuchs, A. H., Boutin, A. & Mellot-Draznieks, C. Thermodynamics of guest-induced structural transitions in hybrid organic-inorganic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 14294–14302 (2008).

Wang, F. & Landau, D. P. Efficient, multiple-range random walk algorithm to calculate the density of states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 2050–2053 (2001).

Landau, D. P. & Binder, K. A Guide to Monte Carlo Simulations in Statistical Physics (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Amar, J. G., Lam, P.-M. & Family, F. Groove instabilities in surface growth with diffusion. Phys. Rev. E 47, 3242–3245 (1993).

Edwards, S. F. & Wilkinson, D. R. The surface statistics of a granular aggregate. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 381, 17–31 (1982).

Kardar, M., Parisi, G. & Zhang, Y.-C. Dynamic scaling of growing interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 889–892 (1986).

Soriano, J. et al. Anomalous roughening of viscous fluid fronts in spontaneous imbibition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 104501 (2005).

Herring, C. Surface Tension as a Motivation for Sintering. In Kingston, W. E. (ed.) The Physics of Powder Metallurgy, 143–179 (MacGraw-Hill, New-York, 1951).

Mullins, W. W. Theory of thermal grooving. J. Appl. Phys. 28, 333–339 (1957).

Wolf, D. E. & Villain, J. Growth with surface diffusion. EPL 13, 389–394 (1990).

Das Sarma, S. & Tamborenea, P. A new universality class for kinetic growth: One-dimensional molecular-beam epitaxy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 66, 325–328 (1991).

Xia, H., Tang, G. & Lan, Y. Numerical analysis of long-range spatial correlations in surface growth. Phys. Rev. E 94, 062121 (2016).

Onuki, A. Theory of phase transition in polymer gels. Adv. Polym. Sci. 109, 63–121 (1993).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kazumasa A. Takeuchi and Tetsuo Yamaguchi for valuable discussions. This work was supported by Inamori Research Grants and the JSPS KAKENHI Grant No. JP24K00594, JP25H01978, and JP25K17354.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.M. and K.T. conceived the project, K.M. performed numerical simulations and analysed the data, and K.M. and K.T. discussed the results and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mitsumoto, K., Takae, K. Elastic heterogeneity governs anomalous dynamic scaling in a soft porous crystal. Commun Phys 9, 36 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-026-02508-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-026-02508-8