Abstract

The ways people think about urban nature affect how people engage with and support nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation in cities. While geographical and socio-demographic characteristics are known to influence people’s thoughts about urban nature, there is little knowledge on how these perceptions can shift over time, especially in response to major events that disrupt the human-nature relationship (such as hurricanes, wildfires, and pandemics). Considering urban trees are a key nature-based solution in cities, this study explores the shift in people’s perceptions about urban trees before and after the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns. We also assessed how urban context and socio-demographics influenced this shift. Using Melbourne, Australia, as a case study, we delivered an online panel survey based on validated psychometrics about urban trees in summer 2020 (pre-COVID-19 lockdowns) and again in summer 2023 (post-COVID-19 lockdowns). The survey helped us explore temporal changes related to values and beliefs associated with urban forests and trees. Our results showed a change in two perceptions, with a 2% decrease in the importance of urban trees for nature (p = 0.02, r = 0.04) and a 4.3% increase in negative beliefs about trees (p < 0.01, r = 0.08) in 2023, compared to 2020. These shifts were greatest in outer urban areas. Furthermore, we observed that most socio-demographic groups rated the importance of the natural values lower and rated negative beliefs about urban trees higher in 2023, compared to 2020. While previous studies have found people had a more positive connection to urban nature during COVID-19 lockdowns, our study highlights that perceptions of urban trees may shift over time, which can lead to future changes in community support and engagement with urban forest management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cities are increasingly investing in urban trees, as they provide a wide variety of ecosystem services that improve the climate resilience, liveability and sustainability of cities, such as urban cooling, stormwater retention and habitat for biodiversity1,2,3. For example, a rapidly growing number of cities are introducing urban tree planting targets to improve climate resilience and long-term urban sustainability4,5. These investments often focus on both planting new trees across the city, as well as maintaining and protecting existing trees, over decades. Urban forest investments rely heavily on community support to be successful. Though urban trees provide many environmental services to humans regardless of how people think or feel about them6, if urban forest managers do not account for the needs and experiences of the community, these urban forest initiatives may decrease other aesthetic, cultural and health wellbeing benefits7. Furthermore, people’s decisions about trees, including what species to plant, and where and how to plant them, influence urban ecosystem structures and functions, and are guided by these needs and experiences8,9. Therefore, to support successful, long-term urban forest management, it is crucial to understand and account for how people think about urban trees, and how these perceptions may shift over time.

A better understanding of how people’s perceptions relate to specific ecological structures in their neighbourhood, such as trees, how these perceptions change over time, and the reasons for these changes, is needed. By perceptions, we mean how people cognitively process their experiences with the urban natural environment, including urban trees10. The cognitive model is a useful way to describe perceptions in terms of abstraction, number, and ease of change11,12. The model describes perceptions as (i) values, or what is important to people; (ii) beliefs, or what people accept as true, such as positive and negative consequences of something; and (iii) attitudes and preferences, or people’s judgement or disposition towards things and how much they like things10,11,13,14. Values and beliefs are regarded as more abstract cognitive constructs that are fewer in number. Values and beliefs develop over long time periods and are not easily changed11,13. Attitudes and preferences are less abstract, influenced by values and beliefs and more numerous and variable11,13. Understanding community perceptions of urban trees can help us better understand the decisions people make, including their level of support for urban forestry15, the structures and functions of urban forests they want or expect, such as their attitude towards the planting and removal of trees16 and their preference for large or small trees17,18.

Our understanding of people’s perceptions of urban trees and how they shift over time is limited. While many studies have explored perceptions towards place-specific natural environments, such as urban green spaces, extrapolating these findings to specific elements of these environments, such as trees, which are widespread and which can become abstract symbols of nature, may be premature. Urban trees can be present in urban environments not deemed green spaces, such as verges and parking lots, and therefore people’s perception of urban green spaces may not accurately represent perceptions towards urban trees in general. Furthermore, most research on how people think about urban trees is based on a moment in time and the socio-environmental and demographic influences upon these perceptions. Nonetheless, a few insights can be learned from the perception of greenspace studies. For example, perceptions of urban greenspace can change over time due to changes in lifestyle, such as retirement or moving to a location that is greener19,20,21. Changes in mental health or moving from a rural to an urban context can also shift how a person perceives urban greenspace22. It is then likely that perceptions of urban trees can shift over time. But extrapolating findings for green spaces, to specific ecological elements found throughout the urban landscape, as trees are, is premature. Also, it is often unclear whether shifts in perceptions are temporary responses to disruptive events or permanent. The social lockdowns in response to the COVID-19 pandemic23 are an example of disruptive events leading to a shift in perceptions of greenspace. During these lockdowns, many people spent more time in local green spaces to exercise, socialise and seek stress relief, and many people developed more positive perceptions of these spaces24,25,26,27. Whether these shifts in perceptions persisted after COVID-19 disruptions ended is unknown.

Previous studies have found that people’s perceptions of urban trees are influenced by urban context and socio-demographics, but our understanding of how these variables interact over time remains limited. Urban context can influence perceptions due to different nature or tree experiences, or the characteristics of the trees within different locations. For example, Gwedla and Shackleton28 and Conway et al.29 found that perceptions of urban trees varied among South African and Canadian cities, respectively, and Su et al.30 found that perceptions of urban trees change along the urban-rural gradient in Toronto, Canada. Socio-demographic characteristics also influence how people relate to and experience urban trees. For example, a study in Melbourne, Australia, found that people who speak a language other than English and were not born in Australia assigned a greater psychological and environmental value to urban trees than other social groups31. Furthermore, several studies have found that during COVID-19 lockdowns, more positive perceptions of urban greenspace were associated with certain socio-demographics and urban context25,27. Therefore, while urban context and socio-demographic variables could influence perceptions, our understanding of their combined influence and role in shifting perceptions of urban trees over time is still premature.

Understanding how socio-demographics and urban contexts interact with shifting perceptions of urban trees over time in response to disruptive life events, such as COVID-19 lockdowns, will provide specific information on perceptions of urban trees, rather than green spaces in general, that will help maintain the relevance of urban forestry to local communities. If perceptions of urban trees are changed long term, this suggests that people’s support and preferences for urban tree programs may also change, affecting the success of these programs. It is crucial for long-term urban forestry to recognise and respond to any shifts or changes in community perceptions of urban trees to ensure success.

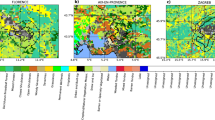

In this study, we use cross-sectional survey data on people’s perceptions of urban trees to explore if perceptions across a population changed long-term after COVID-19 lockdowns, compared to before, and how the associations between perceptions and socio-demographic identity and urban context also shifted over time. We used the Greater Melbourne Area (GMA), Australia, as a case study due to the stringent COVID-19 lockdown restrictions experienced within this region32. We repeated the same survey on perceptions of trees for the GMA: once in February 2020 (pre-COVID-19 restrictions) and again in March 2023 (more than a year after COVID-19 restrictions ended). As this was a cross-sectional study that aimed at exploring how perceptions shifted across the GMA in general, and not a longitudinal study, individuals surveyed within the population for each survey did differ. The perceptions we surveyed were values (a measure of people’s environmental values that focuses on the reasons for valuing concrete aspects of nature), and beliefs (the negative and positive social, ecological, and environmental consequences of having trees in cities), as values and beliefs are known to shape attitudes and preferences14. Socio-demographic variables and knowledge of trees were also collected in the survey. We conducted the survey across ten Local Governmental Areas (LGAs) within the GMA that varied in distance from the city centre, to capture inner, middle and outer urban areas (Fig. 1). We compared the results from the two surveys to determine if there has been a significant change in (a) how people perceive urban trees, and (b) if these changes in perceptions were associated with socio-demographic identities or urban context.

Results

Sample demographics

We received 1693 responses for the 2020 survey and 1646 responses for the 2023 survey. The demographics of respondents were similar to the general GMA population, except that the number born in Australia, who had a university degree or identified as female, was comparatively higher than the GMA average (Table 1). Changes in social profiles between 2020 and 2023 did change, but the changes were similar across the inner, middle and outer LGAs (see the Supplementary Material for further details).

General findings

In both 2020 and 2023, the survey respondents assigned a high level of importance to values associated with urban trees. Of the four value themes, the social value of urban trees was assigned the highest level of importance, closely followed by the natural value, in both 2020 and 2023 (Table 2). There was a higher agreement with positive beliefs than negative beliefs related to urban trees in both 2020 and 2023 (Table 2). The survey respondents also assigned low levels of personal knowledge on trees (Table 2).

Differences in perceptions by urban context

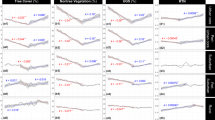

Results from Mann–Whitney U-tests, effect sizes (r) and visual violin plots identified some significant comparable variations in values and beliefs between 2020 and 2023 among the respondents. Among the values, there was a significant decrease of 2% in the mean level of importance assigned to natural values of urban trees from 2020 to 2023 from the survey respondents across the GMA (p = 0.024, r = 0.04). When the respondent data were grouped based on LGA type, this significant decrease in mean perceived natural values was only observed in the outer LGAs (p = 0.024, r = 0.05), where a decrease of 3% was observed (Fig. 2).

Violin plots showing the level of importance assigned to each value theme (A–D) by the survey participants, aggregated by LGA context (inner, middle, outer), as well as the entire study area (all LGAs), and showing statistical differences between the 2020 and 2023 survey responses based on the Mann–Whitney U-test. The average (circle), interquartile range (box), median (horizontal line), and overall data distribution is shown. The asterisks indicate a significant p value for the independent Mann–Whitney U-tests: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Among beliefs, there was a significant comparable increase in negative beliefs about urban trees across the GMA (p < 0.001, r = 0.08), particularly within the middle and outer LGAs where increases of 4.4% and 5%, respectively, were observed in mean negative beliefs (Fig. 3). Self-reported knowledge in trees decreased between 2020 and 2023, with this decrease significant only in the inner (p = 0.01, r = 0.142) and outer LGAs (p < 0.001, r = 0.095). (Fig. 4).

Violin plots showing the level of agreement assigned to positive beliefs (A) and negative beliefs (B) regarding urban trees by the survey participants, aggregated by LGA context (inner, middle, outer), as well as the entire study area (all LGAs), and showing statistical differences between the 2020 and 2023 survey responses based on the Mann–Whitney U-test. The average (circle), interquartile range (box), median (horizontal line), and overall data distribution is shown. The asterisks indicate a significant p value for the independent Mann–Whitney U-tests: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Violin plots showing the personal knowledge of trees assigned by the survey participants, aggregated by LGA context (inner, middle, outer), as well as the entire study area (all LGAs), and showing statistical differences between the 2020 and 2023 survey responses based on the Mann–Whitney U-test. The average (circle), interquartile range (box), median (horizontal line), and overall data distribution is shown. The asterisks indicate a significant p value for the independent Mann–Whitney U-tests: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Differences in perceptions within socio-demographic groups

We found that perceived values significantly changed between 2020 and 2023 within specific socio-demographic groups. People who rent, are under the age of 40, do not have a university education and identify as female all experienced significant decreases in mean ratings for natural values of urban trees between 2020 and 2023 (Table 3). Nearly all socio-demographic groups experienced an increase in negative beliefs towards urban trees between 2020 and 2023, with only people who own a home, over the age of 40, and not identifying as female, not experiencing a significant change (Table 4). We found that significant associations between perceived values and socio-demographic groups remained similar in 2020 and 2023, with a few exceptions (see supplementary material). In 2020, home ownership was significantly associated with lower levels of agreement for the natural value of urban trees (p = 0.01), compared to not owning a home, but this association was not significant in 2023. Among beliefs, speaking a language other than English was only associated with higher negative beliefs in 2023 (p = 0.01), and not 2020.

Discussion

Understanding how perceptions of urban trees change over time can improve our knowledge on the relationships between people and urban nature. Our results demonstrate that small shifts in the values and beliefs that people associate with urban trees occurred over the three years considered in this study. These shifts also varied across urban context, and socio-demographic identities.

The importance people assigned to the natural values of urban trees decreased by 2%, and negative beliefs regarding urban trees increased by 4.3% between 2020 and 2023. These were the only two significant shifts in values and beliefs, but the effect sizes were small, indicating a small change. While small, the decrease in natural values and increase in negative beliefs still suggests that residents now perceive trees more for the disservices they provide, such as costs to manage, and damage and mess they cause33. There may be many explanations for these shifts, and we can speculate on some possible mechanisms. For instance, while people likely found stress relief from urban nature during COVID-19 lockdowns, since restrictions have lifted, many people’s lives have changed, which may have led to people assigning less importance to nature. Indeed, since COVID-19 restrictions ended, Australia, like much of the world, has experienced a cost-of-living crisis, which has increased financial stress across the population34. This stress may be leading people to be more concerned with the economic risks and costs associated with urban trees, perhaps leading to an increase in negative beliefs about nature35. Furthermore, previous studies have found that during times of social disconnection, people can place more value on the aspects of nature that provide active community connection, which could indicate why people place less importance on the nature value of urban trees, which is related to valuing trees for nature’s sake36,37.

The decrease in natural values and increase in negative beliefs were greatest within the outer LGAs. Urban context can play an important role in how people perceive nature, but can also contribute to conflicts between people and nature31. People often move to outer suburbs due to increasing property prices and cost-of-living within the inner suburbs38. With the cost-of-living crisis, it is likely that lower socio-economic households have moved to the outer suburbs post-COVID-19 lockdowns39. Additionally, our finding that knowledge of trees has decreased significantly in the outer suburbs also suggests that more households are moving to these outer suburbs due to cost-of-living pressure rather than to increase exposure to nature. This profile of people within the outer areas may perceive trees as a liability. This raises a significant challenge for urban forest management in these areas over time.

The decrease in natural values observed between 2020 and 2023 was also being driven by renters, people over the age of 40, people without a university education, and people who identify as female. On the other hand, the increase in negative beliefs about urban trees was being driven by nearly every socio-demographic group, except homeowners, people aged over 40, and people who didn’t identify as female. Furthermore, people with a university-level education perceived a higher value of urban trees than those without a university education in 2023, but not in 2020. This echoes studies of urban greenspace use during COVID-19 lockdowns that found that people with a university degree were more likely to visit these spaces regularly as compared to people without a degree25,40. These results all indicate that shifts in perceptions of urban trees over time vary among socio-demographic groups. Accounting for various socio-demographic groups is a way to understand the flexibility of perceptions about urban trees, as well as their permanence over short or long terms. Furthermore, identifying which socio-demographic groups are experiencing negative shifts in perceptions of urban trees over time can allow for more targeted community engagement to improve support for urban trees.

This study demonstrates that the COVID-19 lockdowns may have caused shifts in people’s perceptions of urban trees. A study conducted in Melbourne found that positive perceptions of urban greenspace increased during COVID-19 lockdowns as compared to those held before40. Studies conducted in other cities have also documented more positive perceptions of urban greenspace during COVID-19 restrictions26,40. Our study suggests that any positive shift in the perception of urban trees was temporary and replaced by a small negative shift in urban tree perceptions in the two years after COVID-19 lockdowns ended. However, when these previous studies were implemented, the COVID-19 restrictions were still ongoing, and the cause and effect were likely conflated, as people were asked if COVID-19 made them visit green spaces more. In our study, the cause and effect were confounded and assumed, with perceptions about urban trees becoming more negative in the years after the COVID-19 restrictions had lifted, as compared to before restrictions were introduced. Furthermore, values and beliefs are not easily changed11,13, so the results observed in this study, where only some value dimensions and negative beliefs changed after COVID-19 restrictions ended, is reasonable. However, we recognise that we cannot determine that this shift was solely caused by COVID-19 lockdowns, as our study was not designed as a controlled experiment. Society disruptions are a continuous feature of modern urban life, with the cost-of-living crisis that followed the COVID-19 lockdowns also likely to have influenced the changes in perceptions observed34.

Our 2020 and 2023 survey samples both had higher proportions of Australian-born, university-educated and female participants compared to the census data for the GMA. These observed disparities are common in urban nature surveys25,30. To address this challenge, future studies could explore statistical adjustments, such as weighting and selecting sub-samples of data, to increase similarity between the survey sample and census data. Moreover, as this was a cross-sectional study, we did not survey the same people in 2020 and 2023, although we did survey samples from the same LGAs for both years. Therefore, our study captures changes in community perceptions overall, but not how changes in the perceptions of individual people changed over time. Longitudinal studies could shed further light on individual shifts in perceptions of urban trees and allow for further exploration of the causal mechanisms that are underpinning temporal shifts in perceptions, as well as untangle the degree of influence that urban context and socio-demographic variables each have on shifting perception and whether these two factors are interacting with one another. Integrating economic data and personal wellbeing data for survey respondents when analysing the survey data will also enable further exploration of the impact of the cost-of-living crisis on perceptions of urban trees that we hypothesise here.

Even a small increase in negative perceptions of urban trees could impact community support and engagement for urban forestry, a key aspect of climate adaptation. Increases in negative perceptions could lead to a lack of support for tree management, leading to vandalism and public opposition to tree planting7. As a single urban tree can cost US $748 in management and provide US $886 in benefits over 20 years41, and many cities aim to increase the number of urban trees by thousands, if not millions, even small changes in perceptions could have a significant impact on urban tree management. Knowing where more negative perceptions are occurring can also help focus urban tree management. For example, an urban forest management plan implemented in an outer LGA of Melbourne that aimed to increase the number of street trees may have garnered majority support from the local community before COVID-19 restrictions or cost-of-living pressures, but community support may have waned over the past few years. To account for these shifts in perceptions of urban trees over time, it is important that urban forestry builds strong relationships with community groups, and that adaptive management is integrated into activities such as tree planting, tree maintenance and monitoring, and that community consultation is consistent over time42,43. Potential actions include tailoring community outreach to emphasise the benefits of urban trees in geographical areas with increasing negative perceptions towards urban trees, or to target socio-demographic groups with increasing negative perceptions.

Overall, our results, using the GMA as a case study, suggest that changing social and economic situations could lead to changing perceptions of urban trees across urban landscapes globally. These temporal shifts in perceptions of urban nature can influence the success of nature-based solution investments in cities. For example, increasing negative perceptions of urban trees over time could lead to increasing conflicts between communities and urban trees and reduce the ability of local councils to implement nature-based solutions focused on urban trees. Any understanding of community perceptions must be complemented with enhanced community engagement. Engaging local urban communities is a key aspect for delivering nature-based solutions in cities and ensuring not only that these solutions are supported by the community, but also that the community is part of the decision-making and delivery.

Methods

Study area

The GMA is located in southeast Victoria, Australia (Fig. 1). The GMA is a defined metropolitan area with a population of 5.2 million people44. Culturally, the GMA contains a diverse population, with 40% of residents not born in Australia, which is 10% higher than the national average44. English is the primary language within the region, with 61.1% of the population primarily speaking English45. The GMA has a warm summer temperate climate with no dry season (Koppen climate classification Cfb). The western side of the GMA is located within the South Volcanic Plain Bioregion, while the east is located within the Southeast Coastal Plain46.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, residents within the GMA experienced strict lockdowns. Between 7 July and 15 September 2020, all residents of the GMA experienced stay-at-home orders of varying intensities to slow the spread of COVID-1932. During this period, the GMA residents experienced 6 weeks of the most stringent COVID-19 stay at home orders in the world, with residents required to adhere to a night curfew, to remain at home except for permitted reasons (such as essential shopping, 1 hour of exercise, medical care and essential work), only travel within 5 km of their residence and maintain a social distance of 1.5 m from others32. A further four shorter lockdowns were introduced in 2021, with the GMA experiencing a total of 263 cumulative days under stay-at-home orders between July 2020 and October 202132. A study by Astell-Burt and Feng40 found that GMA residents had more positive perceptions of urban greenspace during this period, and Li et al.47 found that exposure to greenspace during COVID-19 lockdowns in Melbourne improved mental wellbeing. The strictness and duration of the COVID-19 restrictions experienced in the GMA, combined with the evidence of increased positive perceptions of urban greenspace during this time, make this region an ideal case study to explore if changes in people’s lives can lead to persistent long-term changes in their perceptions of urban trees.

The GMA is composed of 31 LGAs. These LGAs vary in urban density and distance to the urban centre, and thus can be used to capture a gradient of inner to outer urban zones. For this study we selected 10 LGAs to conduct our study within (Fig. 1). As each LGA has its own urban forest management plan, which can include different tree species and management, limiting the LGAs assessed allowed us to better control for the range of urban tree management present, while still capturing the inner, middle and outer urban zones of the GMA.

Survey design and sampling strategy

This study was part of a larger research effort to collect long term empirical data on people’s perceptions of urban nature, with a focus on urban forests. To do this, we have designed a survey on perceptions of urban trees (details below). The first survey was delivered from January to March 2020 (before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organisation on March 11, 202048). We delivered the same survey again in March to April 2023 (approximately 1.5 years after the last stay-at-home order in the GMA was lifted on October 21, 202132). The survey and both deliveries of the survey were approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Melbourne (Reference numbers 1750822.1 and 2023-25875-37924-4).

The survey utilises a systematic random sampling approach that ensures both geographic and demographic representativeness. To ensure geographic representativeness, ten LGAs within the GMA were selected to deliver the surveys, within represented inner, middle and outer urban zones. The chosen LGAs consisted of one inner high-density LGA (City of Melbourne), four middle suburban LGAs (Monash, Boroondara, Merri-Bek, Brimbank) and five outer peri-urban LGAs (Melton, Hume, Whittlesea, Casey, Cardinia) (Fig. 1). A target of 2000 responses was set for each survey, with specific response targets set for each LGA, based on their population size (see supplementary material for LGA-specific response targets). Demographic representativeness was achieved by sourcing responses from people representing diverse demographic profiles. We delivered both surveys as web-based self-administered surveys, which allowed parameters to be set that ensure demographic representativeness. We used a panel survey company (PureProfile) to deliver both surveys, as the panel company had access to over 1 million panellists. The survey participants self-selected for the survey and were compensated financially by the panel company, with the compensation amount reflecting the estimated 10 min required to complete the survey. All participants were 18 years or older and provided written consent by checking a box indicating their agreement to participate in the survey.

Survey content

The survey contained questions designed to measure people’s values and beliefs. The measures were based on existing and validated multi-dimensional scales.

We measured values by adapting the Valued Attributes of Landscape Scale (VALS) developed by Kendal et al.49. The VALS is a psychometric measure of people’s environmental values that focuses on the reasons for valuing concrete aspects of nature, such as a particular natural element (e.g. everyday trees in your suburb) rather than more abstract notions of nature (e.g. nature in general). We used an adapted VALS multi-dimensional scale that contained 16 items. Each item was rated on a 5-point scale of importance. The items were grouped into four value themes that people can attribute to urban trees: cultural, social, identity and natural (see the supplementary material for the full list of items).

We measured beliefs using the adapted lists of the negative and positive aspects of urban trees by Kendal et al.14. This resulted in a multi-dimensional scale of 26 items, 13 items measuring positive beliefs and 13 items measuring negative beliefs, all related to the social, ecological, and environmental consequences of having trees in cities. Each item was rated by the degree of agreement on a 5-point scale (see the supplementary material for the full list of items).

We also accounted for knowledge of trees by using a 4-item scale that measures knowledge in common trees species, and planting and caring for trees14. Each item was rated on a 5-point knowledge scale.

Finally, we collected socio-demographic data for each survey participant. Data collected included housing situation (rent or own home), education level attained, cultural diversity (language spoken at home; country born in), age (decade born), gender and the LGA of residence. Data collected for age was used to calculate the median age based on the decade of birth and the year of data collection.

Full survey content is provided in the supplementary material.

Data analysis

We analysed the 2020 and 2023 survey data in the same way. The data were first cleaned to remove blank rows. For the multi-dimensional scales (values, beliefs and knowledge in trees), we conducted factor analyses to create easier to manipulate variables, here called themes (see Table 2 for results). Full details of the factor analysis can be found in Ordóñez et al.50.

We used mean analyses to determine if values, beliefs and knowledge in trees had changed between the 2020 survey (pre-COVID-19 lockdowns) and the 2023 survey (post-COVID-19 lockdowns), using the approach applied by Su et al.30 and Conway et al.29. All measures, for both 2020 and 2023, tested positive for non-normality (p < 0.05) using the Shapiro–Wilk test. We used Mann–Whitney U to test for significant differences between 2020 and 2023 for the complete datasets, and then sub-datasets based on the urban context (inner, middle or outer LGA). We used violin plots to visually compare the distribution of data between the two years.

We also used mean analyses to study changes in values, beliefs and knowledge in trees between 2020 and 2023 within socio-demographic groups, and between socio-demographic groups, as demonstrated in Su et al.30. We converted the socio-demographic data into binary measures, for example, “Age” was converted to “Aged over 40” (yes/no). We then conducted Mann–Whitney U-tests for the 2020 and 2023 survey data, comparing the mean ratings of values, beliefs and knowledge in trees for each binary socio-demographic variable. The p values from the tests were used to determine if there were statistically significant differences among socio-demographic responses for each year.

We used R v.4.3.1 to perform all statistical analysis51.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available, but restrictions apply to protect the privacy of survey participants and so are not publicly available. The data is available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of the University of Melbourne's Human Ethics Committee.

References

Endreny, T. A. Strategically growing the urban forest will improve our world. Nat. Commun. 9, 1160 (2018).

Turner-Skoff, J. B. & Cavender, N. The benefits of trees for livable and sustainable communities. Plants People Planet 1, 323–335 (2019).

Tyrväinen, L., Pauleit S., Seeland, K. & de Vries, S. Benefits and uses of urban forests and trees. Urban forests and trees: A reference book 81–114 (Springer, 2005).

McPherson, E. G., Simpson, J. R., Xiao, Q. & Wu, C. Million trees Los Angeles canopy cover and benefit assessment. Landsc. Urban Plan. 99, 40–50 (2011).

Yao, N. et al. Beijing’s 50 million new urban trees: strategic governance for large-scale urban afforestation. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 44, 126392 (2019).

Roman, L. A. et al. Beyond “trees are good”: disservices, management costs, and tradeoffs in urban forestry. Ambio 50, 615–630 (2021).

Roman, L. A. et al. Stewardship matters: case studies in establishment success of urban trees. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 14, 1174–1182 (2015).

Moskell, C. & Broussard Allred, S. Integrating human and natural systems in community psychology: an ecological model of stewardship behaviour. Am. J. Community Psychol. 51, 1–14 (2013).

Johnson, L. R. et al. Conceptualizing social-ecological drivers of change in urban forest patches. Urban Ecosyst. 24, 633–648 (2021).

Rossi, S. D., Byrne, J. A., Pickering, C. M. & Reser, J. Seeing Red” in national parks: how visitors’ values affect perceptions and park experiences. Geoforum 66, 41–52 (2015).

Stern, P. C., Kalof, L., Dietz, T. & Guagnano, G. A. Values, beliefs, and proenvironmental action: attitude formation toward emergent attitude objects. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 25, 1611–1636 (1995).

Schultz, P. W. The structure of environmental concern: concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. J. Environ. Psychol. 21, 327–339 (2001).

Schultz, P. W. & Zelezny, L. Values as predictors of environmental attitudes: evidence for consistency across 14 countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 19, 255–265 (1999).

Kendal, D. et al. Public satisfaction with urban trees and their management in Australia: the roles of values, beliefs, knowledge, and trust. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 73, 127623 (2022).

Jones, R. E., Davis, K. L. & Bradford, J. The value of trees: factors influencing homeowner support for protecting local urban trees. Environ. Behav. 45, 650–676 (2012).

Kirkpatrick, J. B., Davison, A. & Daniels, G. D. Resident attitudes towards trees influence the planting and removal of different types of trees in eastern Australian cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 107, 147–158 (2012).

Avolio, M. L., Pataki, D. E., Trammell, T. L. E. & Endter-Wada, J. Biodiverse cities: the nursery industry, homeowners, and neighborhood differences drive urban tree composition. Ecol. Monogr. 88, 259–276 (2018).

Camacho-Cervantes, M., Schondube, J. E., Castillo, A. & Macgregor-Fors, I. How do people perceive urban trees? Assessing likes and dislikes in relation to the trees of a city. Urban Ecosyst. 17, 761–773 (2014).

Sang, A. O., Knez, I., Gunnarsson, B. & Hedblom, M. The effects of naturalness, gender, and age on how green space is perceived and used. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 18, 268–276 (2016).

Lin, F. et al. Residents’ living environments, self-rated health status and perceptions of urban green space benefits. Forests 13, 9 (2022).

Mahmoudi Farahani, L. & Maller, C. Perceptions and preferences of urban greenspaces: a literature review and framework for policy and practice. Landsc. Online 61, 1–22 (2018).

Cleary, A. et al. Changes in perceptions of urban green space are related to changes in psychological well-being: cross-sectional and longitudinal study of mid-aged urban residents. Health Place 59, 102201 (2019).

Onyeaka, H. et al. COVID-19 pandemic: a review of the global lockdown and its far-reaching impacts. Sci. Prog. 104, 1–18 (2021).

Grima, N. et al. The importance of urban natural areas and urban ecosystem services during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 15, e0243344 (2020).

Da Schio, N. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use of and attitudes towards urban forests and green spaces: exploring the instigators of change in Belgium. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 65, 127305 (2021).

Ugolini, F. et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use and perceptions of urban green space: an international exploratory study. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 56, 126888 (2020).

Maurer, M. et al. Effects on perceptions of greenspace benefits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Local Environ. 28, 1279–1294 (2023).

Gwedla, N. & Shackleton, C. M. Perceptions and preferences for urban trees across multiple socio-economic contexts in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Landsc. Urban Plan. 189, 225–234 (2019).

Conway, T. M. et al. Comparison of Canadian urban forest perceptions indicates variations in beliefs and trust across geographic settings. Ecosyst. People 20, 2355272 (2024).

Su, K., Ordóñez, C., Regier, K. & Conway, T. M. Values and beliefs about urban forests from diverse urban contexts and populations in the Greater Toronto area. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 72, 127589 (2022).

Ordóñez, C. et al. The role of diverse cultural identities in the perceived value of urban forests in Melbourne, Australia, and implications for urban ecosystem research and practice. Ecol. Soc. 28, 3 (2023).

Auton, J. C. & Sturman, D. Individual differences and compliance intentions with COVID-19 restrictions: insights from a lockdown in Melbourne (Australia). Health Promotion Int. 37, 1–10 (2022).

Drew-Smythe, J. J. et al. Community perceptions of ecosystem services and disservices linked to urban tree plantings. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 82, 127870 (2023).

Tsiaplias, S. & Wang, J. The Australian economy in 2022-2023: Inflation and higher interest rates in a post-COVID-19 world. Aust. Econ. Rev. 56, 5–19 (2022).

Riedman, E. et al. Why don’t people plant trees? Uncovering barriers to participation in urban tree planting initiatives. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 73, 127597 (2022).

Wilkerson, M. L. et al. The role of socio-economic factors in planning and managing urban ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 31, 102–110 (2018).

De la Barrera, F. et al. People’s perception influences on the use of green spaces in socio-economically differentiated neighborhoods. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 20, 254–264 (2016).

Butt, A. Exploring peri-urbanisation and agricultural systems in the Melbourne region. Geogr. Res. 51, 204–218 (2013).

Colic-Peisker, V. & Peisker, A. Migrant residential concentrations and socio-economic disadvantage in two Australian gateway cities. J. Sociol. 59, 365–384 (2023).

Astell-Burt, T. & Feng, X. Time for “Green” during COVID-19? Inequities in green and blue space access, visitation and felt benefits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 2757 (2021).

Ping et al. The economic benefits and costs of trees in urban forest stewardship: a systematic review. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 29, 162–170 (2018).

Hale, J. D. et al. Delivering a multi-functional and resilient urban forest. Sustainability 7, 4600–4624 (2015).

Barron, S. et al. What do they like about trees? Adding local voices to urban forest design and planning. Trees, For. People 5, 100116 (2021).

ABS. Regional Population, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/regional-population/latest-release (2024).

ABS. Greater Melbourne—2021 Census All Persons QuickStats (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra); https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/2GMEL (2024).

DCCEEW. Australia’s Bioregions (IBRA) (Australian Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, Canberra); https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/land/nrs/science/ibra (2023).

Li, A., Mansour, A. & Bentley, R. Green and blue spaces, COVID-19 lockdowns, and mental health: an Australian population-based longitudinal analysis. Health Place, 83, 103103, (2023).

WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. World Health Organisation. https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19 (2024).

Kendal, D. et al. The VALS: a new tool to measure people’s general valued attributes of landscapes. J. Environ. Manag. 163, 224–233 (2015).

Ordóñez, C., Kendal, D., Livesley, S. J. & Conway, T. M. Measuring and modelling values, beliefs and attitudes about urban forests in Canada and Australia. Cities 155, 105406 (2024).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria); https://www.r-project.org/ (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the following people for their feedback on the design of the surveys: Dave Kendal, of Future Nature Pty Ltd Australia; Tenley Conway, Kristen Regier, and Nidhi Subramanyam of the University of Toronto, Canada; and Ian Mell of the University of Manchester, UK. The authors also thank the company Pure Profile for their support in delivering the surveys. This study was funded by a Manchester-Melbourne-Toronto Research Fund grant and an Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Partnership grant (#LP160100780). The funders played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceptualised and designed the work. MCD conducted the analysis and wrote the original draft. SJL and COB helped interpret the results and contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dade, M.C., Livesley, S.J. & Barona, C.O. People’s perceptions of urban trees are more negative after COVID-19 lockdowns. npj Urban Sustain 5, 42 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-025-00230-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-025-00230-y