Abstract

Achieving the goals and actions of SDG11 ‘Sustainable Cities and Communities’ requires targeted sustainability and climate policies, and skilled and focused implementation. What are the roles and required skills of sustainability professionals in this implementation? In-depth interviews with 20 Australian sustainability professionals in public and private sector roles examined barriers and facilitators for implementation of SDG11-related climate and sustainability policies and programs. Results indicate that sustainability professionals, with their high levels of knowledge of climate science and actions, are relied on for specialist advice. Sustainability professionals were found to act as facilitators or intermediaries, linking and championing action within their organisations and between built environment sectors. Likewise, sustainability professionals were found to act as change agents facilitating transitions towards stronger urban sustainability and climate action. While they are pivotal for many organisations’ effectiveness, their work is often reliant on their ‘intervention’ skills of persuasion, as much as wider organisational power.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cities are key contributors to greenhouse gas emissions and other environmental impacts including air quality and other forms of pollution1. Urban areas are also increasingly exposed to the worsening impacts of climate change. Cities and built environments therefore are critical locations for climate and sustainability action, as recognised in the inclusion of an urban-focused sustainable development goal1. Climate change and sustainability action in cities is being planned, influenced and implemented by governments, private sector organisations and businesses, as well as residents and community groups. While economic and political factors are significant influences on climate change and sustainability, there is a wide range of issues impacting the implementation of actions and responses. Cities are often overseen by multiple levels of government (in Australia there are federal, state and local governments), each with distinct roles, responsibilities and powers. Likewise, the complexity of the creation, maintenance and renewal or decommissioning of urban environments means that there are multiple sectors and actors, as well as multiple stages involved in these urban processes2.

This urban complexity points to the importance of “interdisciplinarity inherent in, and necessary for climate change responses across built environment planning, design and management”3. To facilitate climate change and sustainability planning and implementation, professional roles such as sustainability and climate change officers have been created in governments, consultancies and private sector organisations to foster the required interdisciplinary and cross-sector action4. In a recent study of the property sector in Australia, the frontrunner organisations—those most advanced and ambitious in their climate change actions—were found to employ dedicated sustainability professionals and sustainability teams, which led the analysis and dissemination of climate change knowledge and increased implementation of mitigation and adaptation strategies5.

The emergence of sustainability as a distinct professional sector has occurred within the last 50 years, following the publication of the Brundtland report (1987), and the Rio Earth Summit (1992)6. Awareness of environmental issues and impacts had begun rising in the second half of the 20th century, particularly prompted by publications of books such as Silent Spring7, which highlighted environmental damage caused by chemical (mis/over)use, and reports such as Limits to Growth8, which focused on resource over-consumption. These reflected on and prompted further recognition of human impacts on the environment, at both local and global scales. In 1972 in Stockholm, Sweden, the UN Conference on the Human Environment addressed these topics and others including acid rain, whaling and radioactive waste9. This conference arguably led to and underpinned notable global negotiations and environmental outcomes including Montreal Protocol banning use of ozone depleting chemicals9. Further global environmental reports included the World Conservation Strategy (UNEP 1980) and the Brundtland report6.

To mark the 20 year anniversary of the UN Stockholm Conference in 1972, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) (known as the Rio Earth Summit) was held in 1992; the summit created the framework that underpins many of the influential global governance approaches to sustainability, including new global treaties on climate (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)) and biodiversity (Convention on Biological Diversity) and a multilateral and multisectoral agenda for sustainable development action (Agenda 21)4. Further global environmental and sustainable development conferences were held, including in Johannesburg in 2002, and Rio +20 in 2012, at which the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were initiated, to replace the eight Millenium Development Goals1. On 25th September 2015, the SDGs were adopted by all member states of the United Nations, as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The Agenda and the 17 goals attempt to bring together environmental protection with social and economic dimensions, recognizing that “ending poverty must go hand-in-hand with strategies that build economic growth and addresses a range of social needs including education, health, social protection, and job opportunities, while tackling climate change and environmental protection”1.

Yet despite more than 50 years of conferences, strategic planning and international treaties, environmental degradation is increasing. There is also recognition of the intersecting, interconnected nature of these environmental challenges, including climate change, biodiversity extinction and pollution10. Baste and Watson11 argue that.

“none of the internationally agreed environmentally targets for climate and biodiversity have been met and the situation is becoming more dire with each passing year. Unless these issues are addressed in the next 5–10 years none of the 2030 sustainable development goals will be achieved. Human knowledge, ingenuity, technology and cooperation need to be mobilized in such an effort” (p. 1).

In 2022, the Stockholm +50 conference, held on the 50 year anniversary of the first Stockholm conference, highlighted the dramatically increased urgency of action and magnitude of the global environmental issues9; it is possible that without the environmental sustainability efforts since the first global conference in Stockholm, environmental crises could be significantly worse12.

With the increasing global governance focus on sustainability and sustainable development, from at least the turn of the 21st century, came an associated focus on the need for sustainability professionals, with the appropriate range of skills, knowledge and capacity to plan, manage and implement sustainability-related conventions, strategies, targets and action plans4. Reflecting the complexity and diversity of sustainability challenges and opportunities, sustainability professionals work across a range of roles, with differing responsibilities in diverse organisations4,13,14, making a succinct definition of the profession, and its associated roles and responsibilities difficult. Increasingly, sustainability professionals and sustainability teams are driving the planning and implementation of actions that are called for in global sustainability-focused treaties and conventions such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs); the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement (UNFCCC); and the Convention for Biological Diversity (CBD)9.

Education for sustainability has also considerably developed15. In a report on learning and teaching standards for sustainability in higher education in Australia, four areas or domains of knowledge and learning were identified: transdisciplinary knowledge; systemic understanding; skills for environment and sustainability; and ethical practice16. Holdsworth and Thomas17 reinforce the necessity for sustainability education to be future-oriented, arguing that a focus on ‘capability’ development, rather than assessment of competence (which focuses on what has been achieved), is necessary to equip graduates for sustainability professions that must grapple with complex problems, beyond existing, known or historical situations. Likewise, interdisciplinary teaching settings have also been promoted as a necessary grounding for sustainability education and professional development18.

There is also a growing focus on how climate change is addressed in sustainability education, with some studies highlighting the necessity for building skills to assess scientific information and findings, and to empower students to undertake climate actions19. Hurlimann et al.20 argued that climate change education must address both climate science and social science perspectives including political, economic and social dimensions of transformative responses. However, Monroe et al.19 also noted that there were few programmes documented that intentionally took a multi- or transdisciplinary approach to climate change education, indicating an opportunity for both further research as well as curriculum/education development.

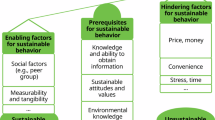

Sustainability professionals require a range of skills and competencies in their delivery of their (varied) roles. MacDonald et al.14 researched the job roles and competencies of local government sustainability managers in Canada, focusing on “the qualifications (who), job responsibilities and work activities (what), as well as the sustainability management competencies that experienced professionals identify as most valuable for performing their sustainability manager job (how)”. They identified 11 key competencies, including communication, change management, collaboration, strategic and systems thinking and project management14. Venn et al.21 examined the competencies of senior sustainability professionals in Belgium, and identified two complementary competency clusters: sustainability research competencies (such as knowledge, and critical and strategic thinking skills) and sustainability intervention competencies (including implementation, collaboration and communication).

‘Intervention competencies’ are fundamental to sustainability professionals’ roles as ‘intermediaries’ in facilitating sustainability transitions (including climate change action); ‘intermediaries’ are sustainability actors who mediate, coordinate, link or network between different sectors, levels of government, stakeholders, activities and stages in sustainability or climate change action13. Extending the focus on the skills of actors in sustainability transitions, Fohim and Jolly22 focussed on the social skills of ‘institutional entrepreneurs’ involved in the introduction of sustainable planning practices in Switzerland. They identified key dimensions of social skills, including empathic, analytical, translational, framing, tactical, organisational and timing skills, and associated different skills with the different phases in sustainability transitions (pre-development; take-off; acceleration; and stabilisation)22. Hilger et al.23 identified 15 different types of roles of actors involved in transdisciplinary research for sustainability. ‘Boundary management’ (including coordinator, choreographer, facilitator, and associated communication roles of communicator, results disseminator) and ‘knowledge co-production’ (including knowledge co-producer, intermediary, data supplier, field expert, practice expert and trouble-maker’) form two key categories of roles23.

For effectiveness, sustainability professionals require both knowledge and intervention skills: in addition to their knowledge of scientific/technical dimensions of sustainability and climate change, their social, organisational and strategic skills contribute to steering, facilitating and influencing transition processes. These skills and contributions can be understood as the individual dimensions of sustainability professionals; also important in the achievement of sustainability and climate change action are the contextual factors—organisational and societal—in which these professionals work22,24. For example, ‘policy success factors’ highlight the importance of leadership and champions, community support, building alliances and networks, amongst other factors in underpinning effective policy development, adoption and implementation25.

With the increasing urgency for climate change action—“our world needs climate action on all fronts—everything, everywhere, all at once”26, the role of sustainability professionals in facilitating, driving and enabling effective responses is increasingly important15. However, amongst the research examining sustainability and climate change action in the built environment, there is little research that focuses specifically on sustainability as a profession, and the roles, barriers and facilitators for these key actors.

This paper aims to contribute to existing knowledge by presenting research examining the roles of sustainability professionals, as well as the barriers and facilitators they experience, in planning and implementing climate change action in Australian cities. The results are based on interviews with sustainability professionals working in the public and private sectors in Australian cities.

Results

A brief overview of the interviewees’ job titles and roles is first provided (Table 1). Following this, key barriers and facilitators that interviewees highlighted they faced in their climate change and sustainability roles are identified. These barriers and facilitators apply both at an individual and contextual scale, the latter including factors within their organisations as well as with external stakeholders and communities. The barriers and facilitators are addressed together, because the interviewees highlighted that frequently they are ‘two sides of the same coin’ (Table 2). To reflect the rich data and insights provided by participants, selected quotes have been included throughout to illustrate the key elements (participants are numbered to indicate their contributions).

Sustainability professionals’ roles in Australia

Of the twenty sustainability professionals interviewed, there were twenty different position titles, reflecting the varied and diverse roles that sustainability professionals fill. The position titles reflect different organisational structures (and therefore different structural or departmental locations for sustainability and climate change teams), spanning both strategic planning and operations or implementation (Table 1). This highlights that sustainability roles are framed to respond to local contexts and organisational priorities; are often required to have cross-cutting, cross-sectoral or interdisciplinary coverage; yet potentially also suggests that even after 50 years since the UN Stockholm conference, sustainability still doesn’t have a clear professional identity.

While the position titles reflect considerable diversity of roles, climate change has arguably accelerated the consolidation of ‘sustainability’ as a distinct profession and a distinct sector within organisations. Bick and Keele27 in their research on city government environmental planning, found that the terms climate change and sustainability are used interchangeably. In this research, ‘climate change’ officers were usually located within ‘sustainability’ teams. Indeed, the integration of sustainability and climate change roles and functions within organisations may support more effective climate change actions. Frantzeskaki et al.28 highlight that urban sustainability requires integrative solutions, and emphasise that sustainability action requires “systems’ thinking, value and place thinking and transitions/transformations thinking” (p.1). Likewise, calls for climate change responses that integrate mitigation and adaptation29 require integrative solutions, that can potentially be better supported by sustainability professionals who intentionally work across sectors.

Sustainability professionals interviewed for this research reinforced that their role is to facilitate integrated action within their organisations and across the built environment:

This is the role that sustainability professionals have, … [an] integration role. A lot of these different disciplines … are thinking about their area and their delivering. They might be delivering very well in their area but they are missing opportunities … you need that integrated approach (17)

The sustainability lead, your role is to try and integrate the sustainability throughout the entire delivery of that project (6)

There are substantial demands on sustainability professionals’ knowledge, skills and competencies in fulfilling their roles and responsibilities. The following section presents findings on the key barriers and facilitators in the achievement of their roles and responsibilities.

Barriers and facilitators

The key barriers and facilitators to effective climate change and sustainability actions identified by the interviewees are summarised in Table 2, grouped into individual and contextual barriers/facilitators across themes adapted from14,21. First, individual barriers and facilitators are discussed—those that relate to interviewees’ own skills and knowledges. Then, the range of contextual barriers and facilitators is highlighted. While many professionals require knowledge specific to their professions, and rely on intervention and collaboration skills, the results of this research focus specifically on the sustainability and climate change requirements of interviewed professionals. Likewise, while the contextual factors identified apply to a range of professions, the results discussed in the following sections highlight how these themes present barriers and facilitators specifically for sustainability and climate action.

Individual barriers and facilitators

The key individual factors identified related to knowledge, and ‘intervention’ (facilitation, or communication) skills. Knowledge skills relate to understanding of both science and implementation aspects of sustainability and climate change action. Intervention skills include the interrelated skills of interpersonal collaboration, capacity building, strategic planning and political awareness21.

Interviewees’ self-assessment of their own level of knowledge of climate change and sustainability science was highlighted as both a barrier—when participants lacked confidence that their knowledge was either sufficiently complete or up-to-date, as well as a facilitator—when they felt confident in being able to develop and communicate strategies, plans and programmes:

A lot of early climate resilience statements and climate risk mitigations could be subjective. I guess it doesn’t build trust when it looks a bit loose and rubbery and uncertain…. I think we’ve still got a lot of work to do to help objectify it, measure it, quantify it, so people trust it (14)

Interviewees also highlighted uneven information availability and specific areas where knowledge and experience are less well-developed or missing, particularly for climate change impacts and adaptation-related topics:

There is a lot more information available on the mitigation side than there is the adaptation side (4)

You can do a business case for energy efficiency, you can use your energy bill, rates as inputs and then measure the outcome … You can do your return on investment, net present value, and blah, blah. With adaptation, it’s just uncertainty on top of uncertainty (4)

Interviewees pointed to both the volume of new information and the challenges of staying up-to-date with the latest science and research:

The climate space is moving so, so quickly. You know, the latest IPCC report … they are chunky, chunky documents with a lot of content there. … There’s a lot of pre-digested information from different sources and even just staying across the latest news and all of that (17)

Participants also reflected on the responsibility of needing to be well-informed on recent science and research, as they were relied upon by their colleagues across their organisations to be able to understand and communicate this knowledge on behalf of all:

They are mostly on board but at the same time, it’s an add-on, something they’re asking me for, rather than actively going out and searching and understanding it themselves (1)

In terms of ‘intervention skills’, participants discussed requirements for their roles to build connections across their organisation:

Collaborations and partnerships … thinking about being more interdisciplinary. Trying to make sure we’re always thinking about things from a whole range of different perspectives (1)

Interviewees also highlighted the intervention skills required to effectively advocate and push for climate change actions:

You need to be credible and influence what that professional is going to do (6)

I know we don’t have that being driven by our architects or builders, it’s us pushing that through (1)

Contextual barriers and facilitators

Contextual barriers and facilitators relate to wider organisational, cultural or political and policy dimensions that can act to constrain or foster effective climate change action. The key barriers and facilitators identified by interviewees included (listed in order of frequency of mention): Leadership, champions and community support; strategic and organisational factors; provision (or lack of) resources; market and economic factors; regulation (or lack of); and technical factors (related to materials and practices). These are discussed below, with key quotes from interviewees to illustrate.

Interviewees highlighted how the existence of organisational leaders who champion climate change action can create an enabling environment and promote broader organisational support, interest and commitment:

the Mayor, councillors and executive, they’re really focused on climate change. It’s a key thing. They get it’s an emergency … They’re absolutely committed, across a broad level of actions and have put their money where their mouth is (3)

You’ve got to have some local champion, local leader who will be prepared to make that hard call (5)

The role of community support and activism to push local government decision-makers towards stronger action was also discussed:

Having the community applying pressure and then having the councils applying the pressure is making it easier for us to be heard (8)

Community surveys of what’s important to people after COVID: greening and climate rose in importance. That really resonated across the organisation for key executive understanding the different policy pieces and the actions (3)

However, political election cycles and short-term decision making can reduce willingness to take strong climate action:

The political component as well because they’re short timeframes. No-one wants to be the person that turns around and says we’re not allowing off street parking or we’re going to phase out car use or we’re going to do this or that when you’ve only got three or four years (3)

The experience of impacts associated with climate change can act to galvanise community concern and promote increased actions. This is echoed in recent research on the translation of exposure to impacts—or reports of impacts—into motivating climate action30. However, interviewees also discussed the slower cumulative changes and impacts and how they created a challenge for mounting arguments of urgency of action:

With climate, it’s long term. Sometimes it’s small cumulative effects. Yes, sometimes it’s a massive—a flood or a bushfire. But they don’t happen as much as the water slowly getting closer and closer to the edge of my house. What am I going to do about that? That’s our biggest problem (9)

Also associated with the themes of leadership (or lack of) were discussion of whose responsibility it is to take climate change action. Interviewees reported on views amongst colleagues, stakeholders and community members that climate change action is perceived to be ‘someone else’s job’, or that action should happen somewhere else, or at some time in the future, reflecting a general resistance to change:

Anything around climate response has always been considered an add-on, rather than an integrated element of anything that we do. Often people perceive it as a bit of a burden or something that somebody else wants us to do, rather than it being something that we actually absolutely need to do because it’s going to have a better outcome for everybody (1)

A key barrier is lethargy or inaction or selfishness (3)

With a lot of people it’s ‘not on my watch’. Either it’s not in my time that I’m going to be in this role, this job or this organisation, or in my life. We deal with quite a few people who say just wait until I’m dead, it’s 10 years or so, maybe 20 and then you can do whatever you like, but until then, I really don’t want this change to happen (3)

The strategic and organisational factors identified as both barriers and facilitators related to interviewees’ roles in planning for and responding to climate action across the organisation, including facilitating integrated action and advocating for stronger responses (the latter links to individual ‘intervention skills discussed in the previous section):

Then one guy from the council said there’s no appetite for that. I said but that’s the whole thing, you’ve got to make the appetite. It doesn’t matter if there’s appetite or not (5)

Strategic and organisational factors also related to the skills and capacities (or lack of) of the organisation as a whole, to plan for and implement effective action:

Some companies are guilty of green washing but most companies are guilty of green wishing, as in they set ambitious targets that they have no idea how to deliver on (11)

Interviewees highlighted their roles in bringing a more comprehensive or broad scale approach to climate change planning and action:

Because we talk about climate change and sometimes there’s physical impacts but there’s a whole range of other legal, economic, financial, social impacts that we need everyone to be aware of and not just thinking about a lot of rain or a big storm or heatwaves. It’s not just about that (1)

A key barrier for some interviewees was the lack of resources allocated to their roles by their organisations, an issue particularly experienced in smaller organisations, and in smaller, less well-resourced rural local governments:

It’s just we have small teams so we’re trying to get everything done (2)

Interviewees identified broader financial and market-based factors which both hamper and facilitate increased climate change action:

It probably just comes down to cost at the end of the day. Years gone by it would be scepticism, but I don’t think that’s an issue anymore (18)

The new, innovative or untested aspects of some climate change responses, and use of new technologies creates financial uncertainties which is also perceived as a barrier to action:

There’s always a higher cost for one-offs. You’re inventing, breaking, creating, re-building, fixing, discarding (16)

The challenge associated with factoring the avoidance of future loss from future impacts to justify current expenditure was highlighted:

It’s more about having a short term view, where addressing climate adaptation is more expensive than not addressing it; not having the decision-making and the thought processes of a whole-of-life picture and understanding it’s an investment in the future and likely to be the lowest cost option (18)

An associated challenge related to the lack of market-based mechanisms to ensure equitable action and responses:

The market will drive a lot of this but the market doesn’t care about people, which is a problem (7)

Insurers are going to drive the change largely, when people realise they can’t get insurance on their house (3)

The existence of policy mechanisms to drive action was highlighted as a key enabler, and lack of effective regulation, or lack of enforcement of regulation as a key barrier:

There’s also a whole range of policy, regulation, carrots and sticks, that could be supporting this … that we don’t really have yet in Australia (1)

Finally, the availability, knowledge and uptake of sustainable materials, technologies and designs were identified as necessary facilitators, and the continued supply of unsustainable materials a key barrier to climate change action. Interviewees highlighted the challenges in shifting ‘business -as-usual’ processes and practices, and the ways in which these processes and practices were supported by the continued supply and use of unsustainable materials and designs:

They’re creating these horrible hot boxes highly dependent on power and air conditioning to make them liveable. But they’re cheap to build (5)

You see it in housing industry, some great examples … but then you’ve got the whole momentum of shit housing that’s built up over time and it just keeps trudging on (20)

Sustainability professionals as policy entrepreneurs and intermediaries

Sustainability professionals’ reflections on what their roles entail and how they achieve outcomes point to their policy ‘entrepreneurship’31. Policy entrepreneurs have been defined as ‘energetic actors who engage in collaborative efforts in and around government to promote policy innovations’32. To achieve these innovations, policy entrepreneurs’ work involves framing the problem, having a solution ready and identifying and exploiting opportunities (including politicians’ interests and motivations) to propose and promote these31. Mintrom and Rogers33 elaborate and provide additional detail on the key roles for change agents in sustainability transitions: “(1) Clarify the problem and articulate a clear vision; (2) Engage others to identify workable solutions and implementation pathways; (3) Secure support from influential stakeholders; (4) Establish effective monitoring tools and learning systems; (5) Foster long-term relationships of trust and mutual support; and (6) Develop narratives that support on-going action” (pp 4-5). Importantly, sustainability professionals’ work relies on the ability to engage others and secure support both within their organisations and more broadly with other levels of government, amongst community members, suppliers, clients and so on—roles termed ‘intermediaries’ in sustainability transitions research for example34,35,36.

Our interviews with Australian sustainability professionals reinforce their awareness of their key role as ‘change agent’33 and of the importance of these functions and the development of associated skills to enable effective action. This section presents their skills and capacities in the context of their roles as entrepreneurs and intermediaries. Interviewees discussed the integration of innovations to embed climate change innovation into ongoing approaches and across life stages of projects:

we want them to do something differently, it’s generally informed by some sort of business case. … you consistently have to justify your own existence and demonstrate that whatever you’re proposing saves people money. [It] often comes back to questions around costs and benefits (4)

we have to be as flexible and adaptive as possible as everything changes around us (1)

The intermediary roles of sustainability professionals to link personnel, planning and actions across their organisations were highlighted:

We’ve looked at inherent risks and now we’ll be going back to staff to look at residual risks, what actions we need to take to ensure climate change risks are managed and fully integrated into the corporate system (2)

cross sectorial work to join up the dots between architects and real estate agents, builders and planners and landscape architects and all that. We all tend to speak in different languages … People don’t understand what each other are talking about … [so our role includes] translating (14)

Yet there was also questioning of whether sustainability and climate change knowledge and expertise should be held within the one team or department only, or whether it should be distributed across the organisation—or in other words whether climate change expertise should become baseline, universal knowledge as climate change approaches are increasingly ‘mainstreamed’ into organisations’ planning and operation:

as climate change grows in breadth and level of complexity, and as we seek to become more mature in how you’re managing it, you’ve got this tension between moving from a model where you have concentrated expertise in one team to having distributed expertise across the whole organisation (11)

Interviewees were increasingly cognisant of their professional responsibilities to communicate and advocate for effective climate change action:

it’s becoming much more widely recognised that to be meeting the core requirements of your professional services obligations, there are decisions that you now need to be making about the integration of climate and if the client doesn’t want to do that, then we consider that to be a breach of our professional standards and we don’t proceed with it (11)

The knowledge, skills and attributes required to fulfil these entrepreneurial/intermediating roles range from technical and scientific knowledges, finance and budgeting, communication, advocacy and building collaborations and alliances32. Frantzeskaki37 also identified skills such as systems thinking and creativity, as well as ‘diplomatic’ skills, that are required to support transitions for climate change action. Fohim and Jolly22 also highlighted the importance of ‘social skills’ including empathic, analytical, tactical and organisational skills of organisational ‘entrepreneurs’ in enabling sustainability transitions.

Finally, several interviewees also acknowledged the emotional challenges of working on climate change and being the ‘holders’ of climate change knowledge, in the context of the increasingly concerning research on climate change impacts, and the urgent calls of scientists and activists for more ambitious action. Indeed some expressed the tension between needing to stay informed with current research, and the impacts of climate grief and anxiety that come with this knowledge38:

I think a lot of people aren’t sharing a lot of the papers unless there’s a real link that they can get some help with because otherwise it’s more doom scrolling. I think people are being mindful of others’ mental health, because there’s a lot of climate grief around (3)

I find it very challenging to maintain optimism and hope around the change that needs to take place. I can temper the way I talk about changes in climate and what it means to be on a RCP 8.5 trajectory. … I feel like I should be painting a much clearer picture of what that looks like. Even though it’s extraordinarily depressing. This is that tension - people move towards hope - and don’t respond well to fear. (17)

I sometimes will consciously not look at things. The latest IPCC report will come out and the media will be how bad things are. If I’m not in the right headspace, I’ll make a conscious decision to not dive into the latest information … there is a tension between keeping up-to-date but also, being self-aware that if I dive into that, I might feel quite anxious about it and not be in a good headspace (19)

All the doom and gloom, it’s overwhelming. I don’t delve into it too much because I struggle, I get sad (5)

Discussion

This paper has presented research into the barriers and facilitators experienced by Australian sustainability professionals. There is a wide range of roles and responsibilities amongst the professionals interviewed, and they identified a range of barriers and facilitators to implementing their roles. Indeed, this wide range reflects both the breadth (and lack of a clear succinct definition) for sustainability and climate professionals, as well as the complexity of built environment sustainability and climate change issues, challenges and opportunities. Nonetheless, the interviewees all shared a ‘sustainability professional’ identity, and pointed to a number of common (shared) insights and opportunities. This section discusses and reflects on these key findings.

Sustainability professionals are often responsible for progressing climate change action as well as sustainability objectives in their organisations. As such, this research is important and timely in understanding the challenges faced by these key actors as urgency for ambitious climate responses accelerates. The barriers and facilitators discussed relate to the professionals’ individual capacities for effectiveness, as well as to broader contextual barriers and facilitators of climate change action. While this research was limited in terms of number of professionals interviewed (20 sustainability professionals working in a range of organisations across Australia’s built environments), as qualitative research that sought to bring depth rather than breadth to the data, useful insights have been gained, that may be applicable to sustainability professionals more broadly. Further research would be useful to better understand the professional and educational backgrounds of these important professionals, and how developments can be made to existing curricula or generate professional development to assist in tackling some of the barriers faced by these professionals and share knowledge relating to the facilitators.

The key barriers and facilitators identified included those related to the professionals themselves: their knowledge and skills in climate change science and action, and social skills (building and facilitating alliances and collaborations; leadership and inspiration). While their own limitations and inexperience can serve as barriers for effective climate action, sustainability professionals play significant roles in facilitating climate action, and are heavily relied upon by their colleagues, clients and other stakeholders. The results point to the importance of maintaining up-to-date and science-informed knowledge and skills on climate change and sustainability, highlighting the necessity for both professional education and ongoing professional development, delivered by experts in the sustainability and climate action fields. The broader (or contextual) barriers and facilitators relate to the context in which the sustainability professionals work, including the structural (including political and economic factors) and institutional dimensions: policy; funding; timeframes; organisational priorities. Many of these barriers and facilitators are relevant beyond the Australian context in which this research has been conducted. The findings are applicable for built environment industries and governments in defining and creating sustainability roles, and helping them to provide an enabling environment for those roles to drive change towards stronger urban sustainability and climate action. Further research could also consider the strengths and weaknesses of having dedicated sustainability professionals and teams within organisations versus embedding sustainability expertise across the organisation.

While sustainability professionals may often lack direct decision making or budgeting capacity, their roles are consistent with those of policy entrepreneurs or intermediaries, who build influence and agency through persuasive communication, collaborations and alliances, from problem and solution framing through to implementation and scaling up actions. Our research indicates that sustainability professionals play key roles in driving climate action, while also navigating the knowledge that we are all facing existential threats of climate impacts.

Methods

This qualitative research focused on the roles of sustainability professionals currently employed by Australian governments and businesses, to examine the barriers and facilitators they identify in their work on climate change and sustainability action in the built environment. The research focuses on the following research questions:

-

What are the organisational positions, roles or job titles of sustainability professionals?

-

What are the key barriers and facilitators to sustainability and climate change action faced by sustainability professionals?

To address these questions, we interviewed professionals employed across a range of organisation types in both the public and private sectors, and located in 5 different Australian states in Australia (Table 3). Invitations were sent to professionals located in all Australian states, but not all invited participants responded, and so there were no participants from South Australia, or from Northern Territory and Australian Capital Territory. To manage the scope of the research, we undertook 20 semi-structured interviews with the sustainability and climate professionals. The data collection sought to generate rich, detailed accounts of the interviewees’ experiences39 of their professional work. As this is qualitative research, the objective is to create rich insights from the interview participants rather than a broad representation of the field as a whole. It is possible that additional interviews, including with professionals in different locations within Australia or internationally, may generate additional insights. Nonetheless, some generalisable conclusions can be drawn from the findings39.

In Australia, all three levels of government (federal, state and local) undertake climate change policy-making and implementation, creating a complex policy environment requiring multi-level governance and coordination. In addition, alliances of local governments have formed in some regions and states to promote and facilitate action and build adaptive capacity, undertake experiments and push more ambitious action40. In addition to the work of governments, sustainability and climate change professionals are also employed by private sector consultancies and businesses. Participants were purposively recruited from professional contacts of the research team, with additional participants identified through snowball sampling39. All participants self-identified as working in the sustainability and/or climate action field within their organisations.

Nineteen semi-structured, online interviews were conducted with twenty interviewees between March 2021 and March 2022, with interviews digitally recorded and transcribed. An interview guide of questions allowed all members of the research team to individually undertake at least one of the interviews. The semi-structured interview guide defined common questions across all interviews and allowed some flexibility for the researcher to follow up particular threads or interesting aspects that arose during the interview. Interviews were of less than one hour duration. Interview questions, which were informed by the research themes and literature highlighted in the Introduction, asked participants about their role, key barriers and facilitators for climate change action they faced within their organisation and more broadly across the built environment. The research received research ethics approval from the University at which the researchers were based. All participants were provided with a Plain Language Statement which provided information about the project and how data would be collected, analysed and reported. All participants signed a consent form, consenting to their participation in the research and audio-recording of the interview.

Data was analysed using a content and thematic analysis approach, with both deductive and inductive coding used39. Transcriptions were uploaded to NVivo (QSR), and initial coding was undertaken by a research assistant. Following this, data was recoded by the research team, applying the analytical framework elements of individual (knowledge and intervention skills) and contextual (organisational or sectoral) factors presented in section 2.3, with inductive coding to also allow for new insights or codes that arose from this data rather than predetermined through the literature review.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the confidentiality of interview data, to protect study participant privacy, but further information may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

UN. Sustainable Development Goals. 17 goals to transform our world, https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (2023).

Hürlimann, A. C. et al. Towards the transformation of cities: a built environment process map to identify the role of key sectors and actors in producing the built environment across life stages. Cities 121, 103454 (2021).

Hürlimann, A. C. et al. Climate change preparedness across sectors of the built environment – a review of literature. Environ. Sci. Policy 128, 277–289 (2022).

Harding, R., Hendriks, C. M. & Faruqi, M. Environmental decision-making: exploring complexity and context. (Federation Press, 2009).

Warren-Myers, G., Hurlimann, A. & Bush, J. Climate change frontrunners in the Australian Property Sector. Clim. Risk Manag., 100340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2021.100340 (2021).

WCED. Our common future. World Commission on Environment and Development, United Nations. (Oxford University Press, 1987).

Carson, R. Silent Spring. (Houghton Mifflin, 1962).

Meadows, D., Meadows, D., Randers, J. & Behrens, W. W. The Limits to Growth. (Universe Books, 1972).

One Earth editorial team. Governance for sustainability. One Earth 5, 575–576 (2022).

UNEP. Making Peace with Nature: A scientific blueprint to tackle the climate, biodiversity and pollution emergencies., (United Nations Environment Program, Nairobi, 2021).

Baste, I. A. & Watson, R. T. Tackling the climate, biodiversity and pollution emergencies by making peace with nature 50 years after the Stockholm Conference. Global Environ. Change 73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102466 (2022).

Galaz, V. Global environmental governance in times of turbulence. One Earth 5, 582–585 (2022).

Fischer, L. B. & Newig, J. Importance of actors and agency in sustainability transitions: a systematic exploration of the literature. Sustainability (Switzerland) 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8050476 (2016).

MacDonald, A., Clarke, A., Ordonez-Ponce, E. & Chai, Z. & Andreasen, J. Sustainability managers: The job roles and competencies of building sustainable cities and communities. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 43, 1413–1444 (2020).

Sharifi, A. Environmental sustainability and resilience—policies and practices. World Sustainability Ser. Part F3411, 1–13 (2024).

Phelan, L. et al. Learning and teaching academic standards statement for environment and sustainability. (Office for Learning and Teaching, 2015).

Holdsworth, S. & Thomas, I. Competencies or capabilities in the Australian higher education landscape and its implications for the development and delivery of sustainability education. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 40, 1466–1481 (2021).

Moosavi, S. & Bush, J. Embedding sustainability in interdisciplinary pedagogy for planning and design studios. J. Plan. Educ. Res., 0739456X211003639. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X211003639 (2021).

Monroe, M. C., Plate, R. R., Oxarart, A., Bowers, A. & Chaves, W. A. Identifying effective climate change education strategies: A systematic review of the research. Environ. Educ. Res. 25, 791–812 (2019).

Hurlimann, A. C., Cobbinah, P. B., Bush, J. & March, A. Is climate change in the curriculum? An analysis of Australian urban planning degrees. Environ. Educ. Res. 27, 970–991 (2021).

Venn, R., Perez, P. & Vandenbussche, V. Competencies of sustainability professionals: an empirical study on key competencies for sustainability. Sustainability (Switzerland) 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094916 (2022).

Fohim, E. & Jolly, S. What’s underneath? Social skills throughout sustainability transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 40, 348–366 (2021).

Hilger, A., Rose, M. & Keil, A. Beyond practitioner and researcher: 15 roles adopted by actors in transdisciplinary and transformative research processes. Sustainability Sci. 16, 2049–2068 (2021).

Upham, P., Bögel, P. & Dütschke, E. Thinking about individual actor-level perspectives in sociotechnical transitions: A comment on the transitions research agenda. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 34, 341–343 (2020).

Bush, J. The role of local government greening policies in the transition towards nature-based cities. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 35, 35–44 (2020).

Guterres, A. Secretary-General’s video message for press conference to launch the Synthesis Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (United Nations Secretary-General, 2023).

Bick, N. & Keele, D. Sustainability and climate change: understanding the political use of environmental terms in municipal governments. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustainability 4 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsust.2022.100145 (2022).

Frantzeskaki, N., McPhearson, T. & Kabisch, N. Urban sustainability science: prospects for innovations through a system’s perspective, relational and transformations’ approaches: This article belongs to Ambio’s 50th Anniversary Collection. Theme: Urbanization. Ambio 50, 1650–1658 (2021).

UNFCCC. Paris Agreement. (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015).

Skurka, C., Myrick, J. G. & Yang, Y. Fanning the flames or burning out? Testing competing hypotheses about repeated exposure to threatening climate change messages. Clim. Change 176, 52 (2023).

Cairney, P. Three habits of successful policy entrepreneurs. Policy Polit.46, 199–215 (2018).

Mintrom, M. So you want to be a policy entrepreneur?. Policy Des. Pract. 2, 307–323 (2019).

Mintrom, M. & Rogers, B. C. How can we drive sustainability transitions? Policy Design and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2022.2057835 (2022).

Frantzeskaki, N. & Bush, J. Governance of nature-based solutions through intermediaries for urban transitions – A case study from Melbourne, Australia. Urban Forestry Urban Greening, 127262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127262 (2021).

Kivimaa, P., Boon, W., Hyysalo, S. & Klerkx, L. Towards a typology of intermediaries in sustainability transitions: A systematic review and a research agenda. Res. Policy 48, 1062–1075 (2019).

Kivimaa, P. et al. Passing the baton: how intermediaries advance sustainability transitions in different phases. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 31, 110–125 (2019).

Frantzeskaki, N. Bringing transition management to cities: Building skills for transformative urban governance. Sustainability 14, 650 (2022).

Gergis, J. Humanity’s Moment: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope. (Black Inc, 2022).

Creswell, J. W. & Creswell, J. D. Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Sixth edn, (SAGE Publications, 2023).

Doyon, A., Moore, T., Moloney, S. & Hurley, J. Evaluating evolving experiments: the case of local government action to implement ecological sustainable design. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2019.1702512 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Research assistance was provided by Laura Cutroni and Josh Nielsen. Thanks to the interview participants who have contributed to this research. This research was funded by Australian Research Council Discovery Grant DP200101378.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.B. wrote the main manuscript text. J.B., A.H., A.M., S.M. and G.W.M. reviewed and edited the manuscript. J.B., A.H., A.M., S.M. and G.W.M. contributed to Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. A.H. led Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bush, J., Hürlimann, A., March, A. et al. Sustainability professionals’ roles in advancing action for climate change and sustainable cities. npj Urban Sustain 5, 60 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-025-00249-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-025-00249-1