Abstract

Most studies investigating the relationship between green exposure and academic performance have been conducted in high-income countries, leaving a significant knowledge gap regarding this association in low- and middle-income settings. Given the distinct urban landscapes, educational systems, and social contexts in these regions, it remains unclear whether previous findings can be generalized. This study addresses this gap by examining the association of urban greenery with academic performance in Brazil. We analyzed a large-scale dataset with individual-level academic performance data from about 3 million Brazilian students, incorporating two greenness metrics—normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and tree cover—across three buffer sizes (300 m, 500 m, and 1000 m). We estimated associations using primary and sensitivity analyses while distinguishing between essay and general subject scores. Our findings indicate that tree cover is more consistently associated with better academic performance than NDVI, suggesting that structural attributes of greenery, such as shade and biodiversity, may play a crucial role in learning environments. The effects were stronger for essay scores compared to general subjects. Furthermore, smaller buffer sizes (300 m) showed more robust associations, emphasizing the importance of immediate green exposure near schools. This study provides compelling evidence that urban greenery, particularly tree cover, supports academic success among Brazilian students. These findings have significant implications for policymakers and urban planners, reinforcing the need to integrate green spaces into school environments to promote equitable access to nature and optimize educational outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Green spaces are increasingly recognized as essential components of urban environments, providing numerous benefits for human health and well-being1. Access to natural environments has been associated with improved mental and physical health2,3, reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression4, lower risks of cardiovascular diseases5,6, and improved cognitive functioning7,8. As urbanization increases globally, understanding the role of green spaces in promoting well-being has become a key public health and urban planning concern.

One of the main pathways through which green spaces influence human health is the reduction of environmental stressors. Urban greenery can mitigate air pollution9,10, reduce noise levels11,12, and buffer the negative effects of extreme heat13,14, all of which contribute to better health outcomes. Additionally, the presence of green areas promotes physical activity15,16 and facilitates social interactions17, both of which are crucial for maintaining mental and physical well-being. Psychologically, exposure to nature has been linked to enhanced cognitive restoration and stress reduction, as proposed by the attention restoration theory18 and the stress recovery theory19, respectively. These mechanisms suggest that green spaces can play a fundamental role in shaping various health outcomes across different age groups, sex, socioeconomic status and urban form.

A growing body of research has linked green exposure to a range of cognitive-related outcomes, consistent with mechanisms proposed by attention restoration theory and stress recovery theory18,19. In school-based experiments, brief “green breaks” led to greater gains in sustained and selective attention and working memory (but not impulse control) and higher perceived restorativeness compared with breaks in built settings20. In early childhood cohorts, closer residential greenness shows benefits: an interquartile-range increase within 50–100 m around the home was associated with lower odds of hyperactivity and better attention/psychomotor speed and visual recognition/working memory on Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery tasks in children aged 4–6 years21. Among 6–12-year-olds, NDVI in 300 m related to better numerical working-memory performance in the younger group, although results were not uniformly consistent and mediation by air pollution or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder was not supported22. At the population level, sparser greenness (lowest decile of NDVI) was associated with a higher risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder versus the highest decile (incidence rate ratio ≈1.55, 95% CI 1.46–1.65; attenuated but persisting at ≈1.20, 95% CI 1.13–1.28), and every 0.1 decrease in NDVI corresponded to about a 3% higher attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder risk in fully adjusted models23. Complementing these behavioral outcomes, laboratory–naturalistic work indicates that the visual quality of urban green scenes predicts positive affect and electroencephalography alpha/theta patterns consistent with relaxation/mindfulness, supporting plausible psychophysiological pathways24.

The relationship between green spaces and academic performance has been examined across multiple designs and spatial scales. A landmark school-environment study reported that classroom/cafeteria views with more nearby natural features (trees, shrubs) were associated with higher standardized test scores, graduation rates, and intentions to attend college, and emphasized the importance of proximity/visibility of greenery to learning spaces25. Multi-site investigations generally find that greener school surroundings relate to better test performance (e.g., English and Mathematics) across grades26,27,28. More recent student-level analyses in a South American capital reported that increased school greenness was associated with higher math and reading scores and higher odds29 of meeting learning targets, with heterogeneity across school sectors26. By contrast, a German longitudinal study observed no consistent associations between residential/school greenspace and grades across two cohorts, despite some signals in one city that were inconsistent in sensitivity analyses27,30,31.

Systematic reviews32,33; consolidate evidence from multiple contexts. These reviews reveal that most studies employ observational, cross-sectional designs, often relying on remotely sensed vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI) or land-use datasets to quantify green exposure. The level of analysis varies, but is predominantly aggregated at the school or neighborhood scale, with fewer studies using individual-level data. In terms of geographic focus, the literature is concentrated in high-income countries, especially in North America and Europe, with far fewer investigations conducted in low- and middle-income countries. While these reviews identify consistent positive associations between greener environments and better academic performance, they also highlight persistent limitations, including the predominance of cross-sectional designs and reliance on aggregated exposure measures that may mask substantial variability within schools. Previous studies have highlighted that, beyond environmental influences such as green spaces, a wide range of factors contribute to academic achievement. Family background and household resources, school quality and management, gender differences, and regional disparities are among the most important determinants identified in the literature34,35,36,37,38. These structural and social dimensions interact with environmental conditions to shape educational outcomes. Recognizing these multiple determinants is therefore essential for situating the potential contribution of green exposure to student performance, given that these factors are pathways or identified moderators that influence the greenness-achievement link.

Despite the growing interest in this field, several research gaps remain. First, many studies have focused on school-level greenery, assessing the amount of vegetation around educational institutions, rather than evaluating how green exposure affects individual students. A previous study in Brazil, for example, analyzed the relationship between green spaces and academic performance at the school level, but did not account for individual-level variations39. Second, most of the evidence on this topic comes from high-income countries, particularly in North America and Europe, while research in Latin America—and specifically in Brazil—remains scarce. Given Brazil’s diverse environmental and socio-economic conditions, studying this relationship in a developing country context is crucial to understanding the generalizability of these findings.

Our study directly addresses these gaps by employing a large-scale, individual-level dataset of nearly 3 million students over two decades in Brazil, a middle-income country where research on this topic remains scarce. By comparing two greenness metrics (NDVI and tree cover) across multiple buffer sizes, and by distinguishing between essay and general subject scores, we extend the literature methodologically and substantively. To address these gaps, this study aims to investigate the impact of green exposure on academic performance at the individual level, using nationwide ENEM data from 2000 to 2020 linked to satellite-derived greenness around schools.

Results

Table 1 presents the demographic and educational characteristics of the 2,887,965 students included in the analytical sample. The majority of students were female (58.08%), while male students comprised 41.92% of the sample. Most students attended public schools (81.5%), with only 18.5% enrolled in private institutions. Regarding school location, the vast majority of students (98.25%) were enrolled in urban schools, whereas only a small proportion (1.75%) attended rural schools. These descriptive statistics highlight key sociodemographic patterns in the study population, reflecting the predominance of urban and public school students in the dataset. The higher representation of female students aligns with general trends observed in Brazilian educational assessments, where female participation in standardized exams is typically higher than that of males. Similarly, the overwhelming presence of urban students mirrors the broader demographic distribution in Brazil, where urbanization rates are among the highest in the world.

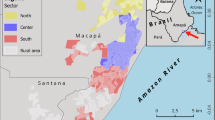

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for student academic performance, green exposure indices, environmental covariates, and student age over the study period (2000–2020). Students’ general subject scores in the ENEM exam had a mean of 778.69 (SD = 964.57), ranging from 0 to 1,000, with a median of 500 and a right-skewed distribution, as indicated by a third quartile (Q3) of 660. Essay scores had a mean of 392.05 (SD = 273.98), with a median of 480 and Q3 of 600, while the lower quartile (Q1) was notably low at 62, suggesting substantial variation in student performance. Green exposure, measured using the NDVI and tree cover percentages across different buffer sizes, showed slightly increasing NDVI values with buffer size (mean values of 0.24, 0.25, and 0.26 for 100 m, 500 m, and 1000 m buffers, respectively) and relatively low tree cover percentages (mean values ranging from 0.12 at 300 m to 0.17 at 1000 m). Figure 1 shows the spatial distribution of academic performance and green exposure in Brazil.

Environmental covariates exhibited substantial variation, with wind speed averaging 2.89 m/s (SD = 0.58) but reaching an extreme maximum of 84.52 m/s, precipitation averaging 3.84 mm per day (SD = 0.95) with a maximum of 22.19 mm, and temperature showing a mean of 21.78 °C (SD = 2.22), ranging from 0 °C to 47 °C, capturing Brazil’s broad climatic differences. Student age had a mean of 19.14 years (SD = 5.20), with a median of 18 years and an interquartile range between 17 and 19 years (Table 2).

The effects of green exposure on student-level academic performance in Brazil demonstrate varying associations between NDVI and tree cover at different buffer distances (300 m, 500 m, and 1000 m) with students’ performance in essay writing and general subjects (Fig. 2). At a 300 m buffer, NDVI was not significantly associated with essay scores (β = 0.02, 95% CI: −0.04 to 0.07) and positively associated with general subject scores (β = 0.02, 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.03). Tree cover at 300 m was positively associated with both essay scores (β = 0.09, 95% CI: 0.04–0.15) and general subjects (β = 0.03, 95% CI: 0.02–0.04), suggesting that increased tree cover in close proximity to students may enhance academic performance. At a 500 m buffer, the results for NDVI indicated a negative association with essay scores (β = −0.06, 95% CI: −0.11 to −0.01) and a null association with general subject scores (β = 0, 95% CI: −0.01 to 0.01). Tree cover at this distance, however, showed an insignificant positive association with essay scores (β = 0.04, 95% CI: −0.01 to 0.09) and a positive association with general subjects (β = 0.02, 95% CI: 0.01–0.03). At the largest buffer of 1000 m, NDVI showed a stronger negative relationship with essay scores (β = −0.11, 95% CI: −0.15 to −0.06) and a null association with general subjects (β = −0.01, 95% CI: −0.02 to 0). Tree cover at 1000 m showed a slightly insignificant negative association with essay scores (β = −0.03, 95% CI: −0.08 to 0.01) and general subjects (β = 0, 95% CI: −0.01 to 0). Overall, these findings suggest that tree cover within 300 m is positively associated with student performance, particularly in essay writing. However, NDVI at larger buffer distances (500 m and 1000 m) appears to have a negative or null association with academic outcomes, indicating that the type and proximity of green exposure may play an essential role in influencing students’ academic performance.

The results from the primary and sensitivity analyses further explore the relationship between green exposure and student-level academic performance in Brazil by considering different model specifications and subgroups (Fig. 3). Across all buffer distances (300 m, 500 m, and 1000 m), tree cover consistently shows a positive association with both essay and general subject scores, particularly in the log-transformed models, reinforcing the findings from the primary analysis. NDVI, however, tends to have a more variable effect, with negative associations observed in several cases, particularly at larger buffer distances. Sensitivity analyses accounting for school-only, individual-only, and environmental-only factors suggest that the positive influence of tree cover remains robust across different model adjustments. Subgroup analyses reveal some variations, with stronger positive effects of tree cover seen in private schools and urban settings, whereas the negative effects of NDVI appear more pronounced in public schools and rural areas. Standardized models further confirm the relative strength of these associations, highlighting tree cover as a more consistent predictor of academic performance than NDVI.

Discussion

Our findings contribute to the growing body of literature on the relationship between green exposure and academic performance, supporting previous studies that have identified positive associations between natural environments and cognitive development40,41,42. Prior research has suggested that exposure to greenery can enhance concentration43,44, reduce stress45, and improve cognitive functioning7,20,46, ultimately benefiting academic outcomes47,48,49. In line with studies conducted in high-income countries, our results indicate that green spaces, particularly tree cover, are positively associated with academic performance. However, the observed effects of NDVI were less consistent, which contrasts with some findings in the literature that have reported positive effects of broader vegetation indices.

Taken together, our results converge with findings from studies conducted largely in high-income contexts that report positive associations between urban greenery and academic outcomes40,41,42,50,51,52,53,54. In particular, the stronger and more consistent signal for tree cover relative to NDVI mirrors evidence that structured, woody vegetation (e.g., street trees and park canopies) is more closely tied to cognitive and educational benefits than broader vegetation indices50,51,52,53,54. At the same time, our mixed NDVI results and the greater salience of shorter buffers (e.g., 300 m) echo reports that the educational benefits of greenness are highly local, with effects attenuating as buffers expand to include vegetation that students do not routinely experience or access32,55,56,57.

Our study extends this literature by providing large-scale evidence from Brazil, a middle-income and ecologically diverse country undergoing rapid urbanization and characterized by marked inequalities in access to high-quality green infrastructure. In this context, tree cover around schools likely delivers shade, microclimate regulation, and restorative visual stimuli in ways that are especially consequential under warmer, sunnier conditions and in neighborhoods where formal parks are scarce. Moreover, differences in municipal resources, school surroundings, and neighborhood safety may affect actual contact with greenery, helping to explain why tree cover—which better captures structured, street-level and school-adjacent vegetation—shows more consistent associations with performance than NDVI, which can include inaccessible or non-woody vegetation55. These features highlight both the commonality of greenery’s benefits across settings and the uniqueness of how those benefits manifest in Brazil’s urban and socioeconomic landscape.

One key aspect of our findings is the stronger and more consistent association between tree cover and academic performance compared to NDVI. This could be due to the fact that tree cover is a more refined metric that captures structured green environments, such as parks and street trees, which may provide direct cognitive benefits through shade, temperature regulation, and esthetic appeal50,51,52,53,54. In contrast, NDVI measures overall vegetation density, including non-woody vegetation such as grass or agricultural fields, which may not provide the same psychological and environmental benefits55. Moreover, NDVI captures all vegetation within the buffer, including private or restricted areas that students cannot access, further limiting its relevance for academic outcomes. Tree cover, by comparison, is more likely to represent structured greenery in urban school surroundings where students interact with nature in meaningful ways, such as shaded schoolyards or urban parks. These differences highlight the importance of considering specific types of green exposure rather than relying solely on broad vegetation indices when assessing the educational benefits of nature.

Our results also suggest that green exposure has a stronger association with essay performance compared to general subjects. One possible explanation is that essay writing requires cognitive skills such as creativity, critical thinking, and sustained attention (Deane et al., 2008), which are particularly sensitive to environmental influences. Green exposure has been linked to improved executive functions58,59,60, which play a crucial role in complex cognitive tasks such as writing. In contrast, performance in general subjects may rely more heavily on rote memorization and structured learning, which may be less influenced by environmental factors. Additionally, essay writing often involves prolonged periods of concentration and reduced cognitive fatigue, which aligns with the psychological benefits of green spaces, such as stress reduction and mental restoration61. These findings suggest that certain academic skills, particularly those requiring deep cognitive engagement, may be more susceptible to environmental enhancements than others.

Another important aspect of our findings is the variation in effect sizes across different buffer distances, with stronger associations observed at shorter distances (e.g., 300 m). This suggests that immediate surroundings, such as the greenery within walking distance of schools and homes, may play a more critical role in academic performance than broader green environments. Short-distance buffers are more likely to capture the everyday exposure of students to nature, including the presence of trees along streets, within schoolyards, or in nearby parks. In contrast, larger buffer distances may include green areas that students do not regularly interact with, diluting their potential benefits. The stronger associations at smaller buffer sizes also align with previous studies indicating that local green spaces have the most direct impact on cognitive and psychological well-being32,56,57. These findings reinforce the importance of prioritizing green infrastructure in the immediate surroundings of schools and residential areas to maximize potential academic benefits.

Despite these important findings, our study has several limitations. First, the observational nature of our research prevents us from establishing causality. While we controlled for multiple confounding factors, unmeasured variables such as socioeconomic status, school infrastructure, and teaching quality may still influence the observed associations. This limitation suggests that future studies should incorporate experimental or longitudinal designs to better isolate causal effects. An additional limitation is the absence of direct individual-level socioeconomic measures such as family income or parental education, which are known to be important predictors of ENEM performance. Although these variables were not available in the dataset, our multilevel modeling strategy partially mitigates this limitation by accounting for unobserved school-level heterogeneity and spatial clustering of students. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that residual confounding by unmeasured socioeconomic factors cannot be entirely ruled out. Another potential source of bias is related to unobserved individual characteristics, such as innate cognitive ability, which may influence both residential choice and academic outcomes. For example, families with higher socioeconomic resources and children with higher academic potential may be more likely to live in greener neighborhoods, which could contribute to the associations observed in this study. Although our modeling strategy, covariate adjustment, and sensitivity analyses help mitigate this concern, the absence of direct measures of cognitive ability and detailed household socioeconomic information means that residual confounding cannot be fully excluded. Future research linking educational records with richer socioeconomic and cognitive datasets will be critical to further disentangle the causal pathways between green exposure and student achievement. Another limitation is that our measures of green exposure rely on remote sensing data, which do not account for individual interactions with green spaces. This means that although tree cover and NDVI provide useful environmental indicators, they do not capture students’ actual experiences with nature. This limitation implies that future research should incorporate behavioral data, such as time spent in green areas, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between green exposure and academic outcomes. A further limitation concerns the availability of tree cover data, which was only accessible for the year 2020. While tree cover tends to change relatively slowly and large-scale shifts are uncommon over short periods—particularly in urban environments—localized deforestation or afforestation events may nonetheless have occurred during the study period. Such local dynamics could introduce some exposure misclassification and should be considered when interpreting our findings. Lastly, our study focuses on a specific population and geographic context, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other regions with different environmental and educational conditions. Future research should explore whether similar patterns hold in different cultural and climatic settings.

Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. It provides robust evidence using a large-scale dataset, allowing for a comprehensive analysis of the relationship between green exposure and academic performance. One of the key strengths of our study is the large sample size, which enhances the statistical power and reliability of our findings. Additionally, we utilized individual-level academic data rather than aggregated school-level performance, ensuring a more precise assessment of the relationship between green exposure and educational outcomes. Another major strength is that our study was conducted in Brazil, making it, to our knowledge, the first study of its kind in this context. Most previous research on this topic has been conducted in high-income countries, where environmental and educational conditions differ significantly from those in middle-income settings. By providing evidence from Brazil, our findings contribute to a more globally representative understanding of how green spaces influence education, particularly in urban and socioeconomically diverse environments. Furthermore, by considering different green metrics (NDVI and tree cover), multiple buffer sizes, and both primary and sensitivity analyses, we were able to identify consistent patterns and refine our understanding of how greenery influences education. Our study also underscores the importance of local green infrastructure, reinforcing the need for urban planning policies that prioritize tree cover in school environments.

To conclude, our study provides strong evidence that exposure to green spaces, particularly tree cover in the immediate surroundings of schools, is positively associated with academic performance. These findings contribute to a growing body of literature emphasizing the role of urban greenery in fostering cognitive development and academic success. Given the rapid urbanization in many parts of the world, including Brazil, our results underscore the need for urban planners and policymakers to prioritize the integration of green spaces into school environments and surrounding areas. Enhancing tree cover near educational institutions could serve as a low-cost, scalable intervention to improve student well-being and academic outcomes, particularly in urban settings where children may have limited access to natural spaces. Investing in urban greenery not only benefits educational attainment but also promotes broader public health and environmental sustainability.

Methods

Student-level academic performance

Student performance data were obtained from the National Institute of Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira (known as INEP), an institution affiliated with the Brazilian Ministry of Education. The primary source of academic performance data was the National High School Exam (known as ENEM), a nationwide standardized examination used for university admissions and educational assessment. On average, approximately 4.5 million students participate in the ENEM each year, representing around 50% of the high school student population in Brazil. This study covers a twenty-year period from 2000 to 2020, allowing for a comprehensive longitudinal analysis of academic performance in relation to green exposure.

The ENEM examination consists of multiple-choice tests assessing mathematics, natural sciences, human sciences, and language skills, along with an essay component that evaluates writing proficiency and critical thinking (INEP, 2020). In this study, academic performance was categorized into two measures: an aggregated score for the multiple-choice tests, representing general subject performance, and a separate essay score. In the Brazilian context, ENEM results are most widely communicated and interpreted using two complementary measures: an essay score and an aggregated multiple-choice score. These indicators provide consistent measures across years, unlike disaggregated subject-specific scores, which vary in structure over time and are only fully standardized in more recent years. For these reasons, we focused on these two complementary measures.

Additional variables included in the dataset comprised the year of examination, student age, sex, and municipality of residence. Furthermore, information on school attributes, including geocoded school locations, school management type (public or private), and whether the school was situated in an urban or rural area, was integrated from the 2020 Educational Census provided by INEP.

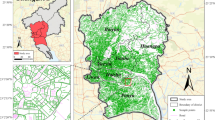

The initial dataset contained 91,587,649 records. To ensure data quality, multiple filtering steps were applied. Observations with missing exam scores or municipality information were excluded, reducing the dataset to 40,404,489 records. Subsequently, only schools with available geospatial data were retained to enable environmental linkage, resulting in a dataset of 7,084,024 observations. To enhance robustness in the analysis, we removed the observations with missing values in the covariates, including information on students’ sex, school management type (public or private school) and school location (rural or urban schools) and select only schools which had at least 4 participants in at last 4 years in the sample ensured the feasibility of including school fixed effects in the models. After applying this final criterion, the dataset was reduced to 2,887,965 individual-level observations, forming the analytical sample for this study. This final analytic sample included 8947 schools. The data reduction process is illustrated in Fig. 4. It is important to note that the ENEM is a high school exit exam, such that each year represents a new cohort of students. Individual students are therefore not tracked over multiple years, and our dataset should be considered a multi-year series of repeated cross-sectional snapshots rather than a true longitudinal panel of individuals. However, schools can be observed repeatedly across years, which allows us to capture temporal variation in school-level exposure to greenery and performance outcomes over two decades.

Previous research has shown that ENEM performance reflects a wide range of social, institutional, and contextual influences. Socioeconomic conditions, the availability of school resources, differences between public and private management, gender patterns in learning outcomes, and regional inequalities across Brazil all contribute to variation in student achievement34,35,36,37,38. In addition, recent studies have highlighted the role of environmental stressors such as ambient air pollution and wildfire in shaping cognitive functioning and standardized test performance62,63,64. These factors provide important context for interpreting the academic performance data used in this study.

Greenness

Green exposure was quantified using two remote sensing-based vegetation indices: the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and tree cover percentage. NDVI values were derived from the Sentinel-2 L2A dataset available through the Microsoft Planetary Computer, which provides global imagery in 13 spectral bands at 10–60 m spatial resolution and a revisit time of approximately five days. Data are processed to L2A (bottom-of-atmosphere) using Sen2Cor and distributed as cloud-optimized GeoTIFFs. Tree cover estimates were obtained from the European Space Agency (ESA) WorldCover dataset, also hosted on the Planetary Computer. This product provides global land cover classification at 10 m resolution, generated by combining Sentinel-1 radar and Sentinel-2 optical imagery, and follows the Land Cover Classification System (LCCS) developed by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). NDVI is a widely used measure of vegetation health and density, derived from satellite imagery, while tree cover percentage represents the proportion of land covered by tree canopy. NDVI data were collected for the entire study period from 2000 to 2020, allowing for a dynamic assessment of green exposure over time. However, tree cover data were only available for 2020.

Green exposure data were processed using the Greenness Exposure Assessment package (GreenExp_R) in R. To assign vegetation indices to students, NDVI and tree cover values were linked to the geospatial coordinates of schools, as provided by the INEP dataset. Specifically, for each student record, annual averages of green space metrics were assigned based on the year of the exam and the location of the school. Green exposure was calculated within three buffer zones—300 m, 500 m, and 1000 m—around each school, allowing for an assessment of green space effects at different spatial scales.

While NDVI data were available for the entire study period (2000–2020), tree cover data were only available for the year 2020. Given that tree cover changes relatively slowly over time, we assumed that the 2020 tree cover distribution could serve as a reasonable approximation for earlier years.

Socio-economic and environmental covariates

To account for potential confounding variables, environmental and socioeconomic factors were incorporated into the analysis. Environmental data were sourced from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) via the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS). The selected environmental variables included temperature, precipitation, and wind speed, all of which were aggregated at the municipal level. These data were originally available as daily gridded estimates. To align them with the academic dataset, we linked each school to its municipality of location and then aggregated the climate data at the municipal level. Specifically, values from all grid cells overlapping each municipality were averaged, and daily estimates were further averaged to produce annual means for the period 2000–2020. This process ensured that all environmental covariates were expressed consistently at the municipal scale and could be merged with student performance data.

These variables were chosen because they capture important aspects of climatic variation relevant to learning outcomes: temperature is directly linked to cognitive performance and exam scores65,66,67,68, precipitation can influence school attendance and outdoor exposure69,70, and wind speed affects both heat perception and the dispersion of air pollutants that may impair cognition71. Annual averages for these variables were computed for the entire 2000–2020 period to ensure consistency with the academic performance dataset.

Additionally, school-level demographic and socioeconomic covariates were included to control for variations in educational contexts. These variables encompassed school location (urban versus rural), school management type (public versus private), student sex, and student age. Although the ENEM dataset does not include detailed family-level socioeconomic measures such as parental education or household income, the available variables provide important proxies for capturing differences in educational opportunities.

Statistical analysis

To address the main aim of this study, we applied mixed-effects regression models to examine the relationship between green exposure and academic performance. This approach was selected due to the hierarchical structure of the data, where students are nested within schools. The model specification included both fixed and random effects, allowing for an accurate representation of between-school and within-school variations. A random intercept was included for each school to account for unobserved school-level factors influencing student performance. Additionally, a random slope for green exposure (NDVI or tree cover) was specified at the school level, allowing the effect of green exposure on academic performance to vary between schools. This accounts for potential differences in how schools, due to their unique characteristics, mediate the relationship between environmental factors and student achievement. Also, this hierarchical specification ensures that students are not assumed to be spatially or socially evenly distributed. By nesting students within schools and including both random intercepts and random slopes for green exposure, the model explicitly accounts for clustering effects and allows the association between greenery and academic performance to vary across schools, thereby capturing spatial and institutional heterogeneity. This random-slope specification estimates a distribution of school-specific greenery effects—rather than a single national coefficient—thereby capturing spatial and institutional heterogeneity across Brazil while maintaining stable, partially pooled inference.

The dependent variable in the regression models was student performance in the ENEM, which was log-transformed to facilitate interpretation in terms of percentage change. The primary independent variable was green exposure, measured separately using NDVI and tree cover. Additional covariates included environmental factors such as temperature, precipitation, and wind speed, as well as school-related and individual characteristics, including school management type, school location, student sex, and student age. Year effects were modeled using splines to account for potential non-linear temporal trends.

To ensure robustness and explore potential variations in the relationship between green exposure and academic performance, stratified analyses were performed. The models were stratified based on the green exposure buffer size (300 m, 500 m, and 1000 m), the type of academic performance measure (Essay score vs. General subject scores), and the greenness metric used (NDVI vs. tree cover). All statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.1.3). The lme4 package was used to estimate the mixed-effects regression models. The core model used in our analysis was specified as follows:

where \(y\) is the academic performance (log-transformed ENEM score) for student i, for the subject z (General subjects and Essay), and school s; \({\beta }_{0}\) is the random intercept coefficient for subject z varying by school s; β1 represents the random slope coefficient for greenness metric (NDVI or tree cover) at the school level, allowing the effect of green exposure to vary across schools s; the other coefficients (β2, β3, β4, β5, β6, β7, and β8) represent the effects from the temperature, precipitation, wind speed, school location (rural/urban), school management (public/private schools), sex, and age, respectively.

To assess the robustness of the findings, we conducted several sensitivity analyses. One key concern was the variation in ENEM scoring scales across different years. The total possible ENEM score varied over time, with different maximum values applied in different years (e.g., some years ranged from 0 to 100, while others ranged from 0 to 500). To address this issue, we standardized the variable by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation for each year, transforming the score into an annual z-score with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. This approach ensures that performance scores are comparable across different years, mitigating potential biases introduced by inconsistencies in scoring scales. A secondary set of regression models was estimated using this standardized score to verify whether the main findings were robust to variations in the ENEM grading system.

Additionally, alternative models were tested by keeping key control variables to assess the potential influence of omitted-variable bias. Separate models were estimated keeping only (i) environmental variables (wind speed, temperature, and precipitation), (ii) individual demographic characteristics (student sex and age), and (iii) school attributes (urban/rural classification and public/private management). These sensitivity analyses ensured that the observed associations were not driven by specific modeling choices or variable selection, providing a more comprehensive assessment of the relationship between green spaces and academic performance.

Finally, we accounted for effect modification by stratifying the main model by public/private management, urban/rural classification and student sex.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to policies of the Ministry of Education in Brazil, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Reyes-Riveros, R. et al. Linking public urban green spaces and human well-being: A systematic review. Urban Urban Green. 61, 127105 (2021).

Jimenez, M. P. et al. Associations between nature exposure and health: a review of the evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021 18, 4790 (2021).

Triguero-Mas, M. et al. Natural outdoor environments and mental and physical health: relationships and mechanisms. Environ. Int. 77, 35–41 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Long-term exposure to residential greenness and decreased risk of depression and anxiety. Nat. Ment. Health 2, 525–534 (2024).

Liu, X. X. et al. Green space and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 301, 118990 (2022).

Keith, R. J., Hart, J. L. & Bhatnagar, A. Greenspaces and cardiovascular health. Circ. Res. 134, 1179–1196 (2024).

Jimenez, M. P. et al. Residential green space and cognitive function in a large cohort of middle-aged women. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e229306–e229306 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Air pollution as a risk factor for Cognitive Impairment no Dementia (CIND) and its progression to dementia: a longitudinal study. Environ. Int. 160, 107067 (2022).

Venter, Z. S., Hassani, A., Stange, E., Schneider, P. & Castell, N. Reassessing the role of urban green space in air pollution control. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2306200121 (2024).

Islam, A. et al. Impact of urban green spaces on air quality: A study of PM10 reduction across diverse climates. Sci. Total Environ. 955, 176770 (2024).

Dzhambov, A. M. & Dimitrova, D. D. Green spaces and environmental noise perception. Urban Urban Green. 14, 1000–1008 (2015).

Van Renterghem, T. Towards explaining the positive effect of vegetation on the perception of environmental noise. Urban Urban Green. 40, 133–144 (2019).

Song, J. et al. Do greenspaces really reduce heat health impacts? Evidence for different vegetation types and distance-based greenspace exposure. Environ. Int. 191, 108950 (2024).

Wong, N. H., Tan, C. L., Kolokotsa, D. D. & Takebayashi, H. Greenery as a mitigation and adaptation strategy to urban heat. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021 2, 166–181 (2021).

Klompmaker, J. O. et al. Green space definition affects associations of green space with overweight and physical activity. Environ. Res. 160, 531–540 (2018).

Wang, H. & Tassinary, L. G. Association between greenspace morphology and prevalence of non-communicable diseases mediated by air pollution and physical activity. Landsc. Urban Plan 242, 104934 (2024).

Huang, W. & Lin, G. The relationship between urban green space and social health of individuals: a scoping review. Urban Urban Green. 85, 127969 (2023).

Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 15, 169–182 (1995).

Ulrich, R. S. et al. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 11, 201–230 (1991).

Amicone, G. et al. Green Breaks: the restorative effect of the school environment’s green areas on children’s cognitive performance. Front Psychol. 9, 1–15 (2018).

Dockx, Y. et al. Early life exposure to residential green space impacts cognitive functioning in children aged 4 to 6 years. Environ. Int. 161, 107094 (2022).

Subiza-Pérez, M. et al. Residential green and blue spaces and working memory in children aged 6–12 years old. Results from the INMA cohort. Health Place 84, 103136 (2023).

Thygesen, M. et al. The association between residential green space in childhood and development of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a population-based cohort study. Environ. Health Perspect. 128, 1–9 (2020).

Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Sia, A., Fogel, A. & Ho, R. Features of urban green spaces associated with positive emotions, mindfulness and relaxation. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–13 (2022).

Matsuoka, R. H. Student performance and high school landscapes: examining the links. Landsc. Urban Plan 97, 273–282 (2010).

Jimenez, R. B. et al. School greenness and student-level academic performance: evidence from the Global South. Geohealth 7, e2023GH000830 (2023).

Requia, W. J. & Adams, M. D. Green areas and students’ academic performance in the Federal District, Brazil: an assessment of three greenness metrics. Environ. Res. 211, 113027 (2022).

Leung, W. et al. How is environmental greenness related to students’ academic performance in English and Mathematics?. Landsc. Urban Plan. 181, 118–124 (2019).

Ahmed, W. et al. Machine learning-based academic performance prediction with explainability for enhanced decision-making in educational institutions. Sci. Rep. 15, 26879 (2025).

Markevych, I. et al. Residential and school greenspace and academic performance: evidence from the GINIplus and LISA longitudinal studies of German adolescents. Environ. Pollut. 245, 71–76 (2019).

Rahai, R., Wells, N. M. & Evans, G. W. School greenspace is associated with enhanced benefits of academic interventions on annual reading improvement for children of color in California. J. Environ. Psychol. 86, 101966 (2023).

Browning, M. H. E. M., Rigolon, A., McAnirlin, O. & Yoon, H.(V. iolet) Where greenspace matters most: a systematic review of urbanicity, greenspace, and physical health. Landsc. Urban Plan 217, 104233 (2022).

Davis, Z. et al. The association between natural environments and childhood mental health and development: a systematic review and assessment of different exposure measurements. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 235, 113767 (2021).

Moraes, C. P. de, Peres, R. T., Barbosa, M. T. S. & Pedreira, C. E. Equidade e desempenho no Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio: Um estudo sobre sexo e raça nos municípios brasileiros. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 30 (2022).

De Oliveira Rubim, J. A., Mantovani, D. & Munhoz Alavarse, O. EXCLUSÃO DIGITAL E SEUS IMPACTOS SOBRE A PROFICIÊNCIA NO ENEM: UM ESTUDO COM CONCLUINTES DO ENSINO MÉDIO DE BAIXA RENDA ENTRE 2015 E 2023. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1590/SciELOPreprints.11680 (2025).

Jaloto, A. & Primi, R. Fatores socioeconômicos associados ao desempenho no Enem. Em Aberto 34 (2021).

Dutra, J. F., Firmino Júnior, J. B., Fernandes, D. Y. & de, S. Fatores que podem interferir no desempenho de estudantes no ENEM: uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Rev. Bras. Inf. Educ. 31, 323–351 (2023).

Melo, R. O., Freitas, A. C. de, Francisco, E. deR. & Motokane, M. T. Impacto das variáveis socioeconômicas no desempenho do Enem: uma análise espacial e sociológica. Rev. Adm. Pública 55, 1271–1294 (2021).

Requia, W. J., Saenger, C. C., Cicerelli, R. E., de Abreu, L. M. & Cruvinel, V. R. N. Greenness around Brazilian schools may improve students’ math performance but not science performance. Urban Urban Green. 78, 127768 (2022).

Stenfors, C. U. D. et al. Positive effects of nature on cognitive performance across multiple experiments: test order but not affect modulates the cognitive effects. Front. Psychol. 10, 438004 (2019).

Nguyen, L. & Walters, J. Benefits of nature exposure on cognitive functioning in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 96, 102336 (2024).

Rhee, J. H., Schermer, B., Han, G., Park, S. Y. & Lee, K. H. Effects of nature on restorative and cognitive benefits in indoor environment. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–9 (2023).

Kitch, J. C., Nguyen, T. T., Nguyen, Q. C. & Hswen, Y. Changes in the relationship between Index of Concentration at the Extremes and U.S. urban greenspace: a longitudinal analysis from 2001–2019. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023 10, 1–10 (2023).

Bijnens, E. M. et al. Higher surrounding green space is associated with better attention in Flemish adolescents. Environ. Int. 159, 107016 (2022).

Ashraf, K. et al. Examining the joint effect of air pollution and green spaces on stress levels in South Korea: using machine learning techniques. Int. J. Digit. Earth 17 (2024).

Dadvand, P. et al. Green spaces and cognitive development in primary schoolchildren. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 7937–7942 (2015).

Browning, M. H. E. M. & Locke, D. H. The greenspace-academic performance link varies by remote sensing measure and urbanicity around Maryland public schools. Landsc. Urban Plan 195, 103706 (2020).

Claesen, J. L. A. et al. Associations of traffic-related air pollution and greenery with academic outcomes among primary schoolchildren. Environ. Res. 199, 111325 (2021).

Kuo, M., Klein, S. E., Browning, M. H. E. M. & Zaplatosch, J. Greening for academic achievement: prioritizing what to plant and where. Landsc. Urban Plan. 206, 103962 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Global mapping of fractional tree cover for forest cover change analysis. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 211, 67–82 (2024).

Thorpert, P., Englund, J.-E. & Sang, ÅO. Shades of green for living walls—experiences of color contrast and its implication for aesthetic and psychological benefits. Nat. Based Solut. 3, 100067 (2023).

Klemm, W., Heusinkveld, B. G., Lenzholzer, S. & van Hove, B. Street greenery and its physical and psychological impact on thermal comfort. Landsc. Urban Plan. 138, 87–98 (2015).

Zhang, M. et al. Assessing the impact of fractional vegetation cover on urban thermal environment: a case study of Hangzhou, China. Sustain Cities Soc. 96, 104663 (2023).

Lee, H., Mayer, H. & Chen, L. Contribution of trees and grasslands to the mitigation of human heat stress in a residential district of Freiburg, Southwest Germany. Landsc. Urban Plan. 148, 37–50 (2016).

Martinez, A., de la, I. & Labib, S. M. Demystifying normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) for greenness exposure assessments and policy interventions in urban greening. Environ. Res. 220, 115155 (2023).

Liu, Y., Kwan, M. P. & Wang, J. Analytically articulating the effect of buffer size on urban green space exposure measures. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/13658816.2024.2400260. (2025).

Browning, M. & Lee, K. Within What Distance Does “Greenness” Best Predict Physical Health? A systematic review of articles with GIS buffer analyses across the lifespan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 675 (2017).

Ricciardi, E. et al. Long-term exposure to greenspace and cognitive function during the lifespan: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 11700 (2022).

Sánchez-Pérez, N., Gracia-Esteban, M., Santamaría-Gutiez, R. & López-Crespo, G. Contact with nature and executive functions: a pilot study with Spanish preschoolers. J. Child., Educ. Soc. 4, 234–248 (2023).

Buczyłowska, D. et al. Exposure to greenspace and bluespace and cognitive functioning in children—a systematic review. Environ. Res. 222, 115340 (2023).

Grigoletto, A. et al. Restoration in mental health after visiting urban green spaces, who is most affected? Comparison between good/poor mental health in four European cities. Environ. Res. 223, 115397 (2023).

Gardin, T. N. & Requia, W. J. Air quality and individual-level academic performance in Brazil: a nationwide study of more than 15 million students between 2000 and 2020. Environ. Res. 226, 115689 (2023).

Gardin, T. N. & Requia, W. J. The effect of wildfire smoke exposure on student performance: a nationwide study across two decades (2000–2020) and over 40 million students in Brazil. Neurotoxicology 108, 143–149 (2025).

Carneiro, J., Cole, M. A. & Strobl, E. The effects of air pollution on students’ cognitive performance: evidence from Brazilian University Entrance Tests. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 8, 1051–1077 (2021).

Park, R. J., Goodman, J., Hurwitz, M. & Smith, J. Heat and Learning. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 12, 306–339 (2020).

Goodman, J., Hurwitz, M., Park, J. & Smith, J. Heat and Learning. https://doi.org/10.3386/w24639 (2018).

Venegas Marin, S., Schwarz, L. & Sabarwal, S. Impacts of extreme weather events on education outcomes: a review of evidence. World Bank Res. Obs. 39, 177–226 (2024).

Li, X. & Patel, P. C. Weather and high-stakes exam performance: Evidence from student-level administrative data in Brazil. Econ. Lett. 199, 109698 (2021).

Bekkouche, Y., Houngbedji, K. & Koussihouede, O. Rainy days and learning outcomes: evidence from sub-saharan Africa. Preprint at https://univ-paris-dauphine.hal.science/hal-03962882/#:~:text=Our%20results%20suggest%20that%20student,likely%20to%20experience%20grade%20repetition (2023).

Ferreira de Lima, F. L., Barbosa, R. B., Benevides, A., Mayorga, F. D. & de, O. Impact of extreme rainfall shocks on the educational performance of vulnerable urban students: evidence from Brazil. EconomiA 25, 247–263 (2024).

Abbassi, Y., Ahmadikia, H. & Baniasadi, E. Impact of wind speed on urban heat and pollution islands. Urban Clim. 44, 101200 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Brazilian Agencies National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MCTI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the paper. Weeberb Requia: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project Coordination, Supervision, and Writing—Review & Editing.Thiago Gardin: Software, Writing—original, Validation, Data Curation, and Visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gardin, T.N., Requia, W.J. Green spaces and learning outcomes in 3 million Brazilian students. npj Urban Sustain 5, 100 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-025-00287-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-025-00287-9