Abstract

Urban land-change forecasts can facilitate understanding causes and consequences of land changes due to urbanization. Yet, we do not know why these forecasts are generated, how reliable they are, and what they collectively tell us about future urbanization. Through a systematic review, we identified 601 papers reporting urban land-change forecasts: 518 papers for 322 case-study locations in 73 countries, 71 for large regions, and 12 for global analysis. In 44% of these, the motivation is simply forecasting future urban land. Accuracy and uncertainty assessments continue to be neglected. An ensemble of global forecasts suggests urban land may range from about 0.9(1) to over 2.5(5) million km2 by 2050(2100). Forecasts from the Global South are increasing but understanding of future urban land expansion remains uneven across city sizes and geographies. Progress on real-world relevance, reliability, and representativeness of urban land-change forecasts will greatly advance their potential to inform policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The physical expansion of urban areas leads to lasting impacts on landscapes and livelihoods1. Urban land expansion as well as the concentration of people, economic activity, and resources in urban areas impact many aspects of the Earth system from biogeochemical cycles to local climate to biodiversity2 while putting disproportionately large portions of human population and infrastructure at risk from natural hazards3. However, these same factors also present an unprecedented window of opportunity to chart realistic paths for urbanization towards global sustainability4. Understanding the social, economic, and biophysical dynamics behind urban land change and how these may unfold into the future is critical to navigate the multitude of trade-offs between the opportunities and challenges brought about by urbanization.

In this respect, forecasting urban land change can be instrumental in developing a deeper, integrated understanding of the dynamic processes underlying, and consequences of, changes in urban land composition and configuration5 and how these may unfold in the future6. Therefore, urban land change models (LCMs), as virtual laboratories to test our assumptions on processes and patterns of urban land change, hold significant potential to help better understand how socio-economic processes and biophysical factors lead to urban land change and hence help uncover the interactions of urbanization with broader global change processes2,4,7,8. To date, there have been several reviews of urban LCMs. Most of these reviews covered in depth the mechanistic details of various methodological approaches9,10,11,12,13 while others focused on aspects of inputs and drivers14,15, performance16, or assessment17 of various urban LCMs (see Supplementary Note 1). Consequently, each of these reviews had a limited emphasis on particular aspects and practices of urban land change modeling. However, there has been little attention on urban land-change forecasts themselves in terms of their representativeness of geographical and temporal trends of urbanization, their reliability, and motives behind their development.

Here we present a comprehensive synthesis of urban land-change forecasts, based on a systematic review, guided by three questions: (1) To what extent, do the existing urban land change forecasts capture the geographical and temporals trends in urban land change? (2) How reliable are these forecasts? (3) Why are they generated? Based on our findings, we then propose future directions for urban land change forecasts to remain relevant and informative to address the intensifying challenges that urbanization and broader environmental changes bring on.

Results

Global urban forecasts range widely

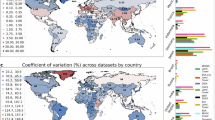

Out of the 601 papers included in our systematic review (Supplementary Fig. 1; see Methods), twelve presented global forecasts, most published over the last five years (Supplementary Table 1). Six and seven of these papers, respectively, presented forecasts to 2050 and 2100 using scenarios aligned with the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) of the IPCC (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 2). There is broad agreement among these forecasts that 1) urban land expansion will be significant, especially in developing regions and 2) by 2100, we expect the least urban expansion under SSP1 (sustainability) and the most under SSP5 (fossil fuel-intensive development).

Seven of the twelve global forecasts developed based on SSPs have forecasts for 2050 (a); six for 2100 (b). Regional breakdown according to the IPCC. (A) Gao & O’Neill (2020), (B) Chen et al. (2020), (C) Li et al. (2019), (D) Huang et al. (2019), (E) Chen et al. (2022), (F) Gao & Pesaresi (2021), (G) Li et al. (2021), (H) Mean across all forecasts, (I) Median across all forecasts.

However, there is substantial variation among the forecasts, not only across the five SSPs but also among the studies for any given SSP. Across the five SSPs, the forecasted global urban land ranges from about 0.9 million to over 2.2 million km2 in 2050 and from 1.0 million to over 4.5 million km2 in 2100 (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2). The median share of global urban land that is in developed countries is expected to change, from around 38% in 2015, to anywhere from 23% (SSP2) to 39% (SSP1) in 2100. The ranges across the studies are also large: The widest range of forecasted global urban land for a particular SSP is observed among those for SSP5 (1.3 million km2 to 4.6 million km2) whereas the narrowest is observed for SSP3 (regional rivalry) (1.0 million km2 to 2.0 million km2). Even for SSP3 with the narrowest range, the difference between the highest and lowest forecasted urban land in 2100 is more than the largest estimate for urban land cover circa 2015. Similarly wide ranges exist in each region across the SSPs as well as across the forecasts for each SSP (Fig. 1). Notably, even for Developed Countries, whose urban transition is generally considered complete, new urban land area could range from 23,000 (SSP3) to 573,000 km2 (SSP5) by 2050, and from 38,000 (SSP3) to 1.7 million km2 (SSP5) by 2100.

Almost half of all local studies come from only three countries

Over 85% of the papers have specific case study locations (i.e., reports forecasts for a single city or a metropolitan area as opposed to global, regional, or country-wide forecasts). Between 2002 and 2009, each year, fewer than three papers with local case studies were published and they constituted nearly 70% of all papers published. Since then, the average number of papers with local case studies published each year reached 40 (84%) with particularly large increases over the last three years (Supplementary Fig. 2). The corresponding percentage of regional (country-wide or larger) forecasts, on the other hand, decreased from about 30% to 12%; still, over half of all regional forecasts were published in the last three years.

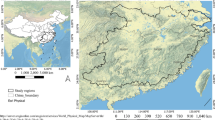

Forecasts of urban land have been reported for a total of 322 distinct case study locations from a total of 73 distinct countries since 1996, the first year an urban LCM was published (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3B). In line with the increasing number of papers published every year, a larger number of distinct case study locations from a larger number of distinct countries appeared in the literature over time. Still, one third of all case study locations in our review are in China (100 case study locations) followed with a wide margin by India (42 case study locations) and Iran (23 case study locations) (Supplementary Fig. 3C). The case study locations from these three countries constitute 45% of the total number of unique case study locations in our review. In comparison, there are only 25 and 12 case-study locations, respectively, from Africa and South America. Nigeria and Egypt accounted for over one-third of all case-study locations (and 47% of case studies) in Africa (Supplementary Figs. 3B-C, 4). Among the case study locations, Wuhan in China ranks first with the highest number of case studies (n = 28), followed by Beijing (12 case studies), and Tehran and Tianjin (10 case studies each) (Supplementary Table 3).

The locations of case study sites and the number of case studies for each are shown along with the total number of case study sites in each country with at least one case study site. Countries with no case study sites are shown in light gray. Altogether, we identified 522 case studies for 322 case study locations from 73 countries.

Most case study locations are cities with over 2 million inhabitants

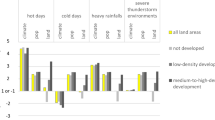

There is also a clear bias across the forecasts towards large urban areas (i.e., more than 2 million in population) (Fig. 3). The number as well as the proportion of cities studied in each city-size category increase with increasing city size for all the regions combined, which also broadly holds for individual regions. This large-city bias is most apparent in China, India, and the North America but also in Africa and Europe. Overall, cities larger than 2 million people constitute 50 percent of case study sites in our review although these cities constitute only 14 per cent of the total number of cities with a population larger than 300,000 people18.

Accuracy of most forecasts is poorly evaluated

While the proportion of forecasts without any information on their accuracy at all has tended to decrease over the past decade (Supplementary Fig. 5), they still constitute almost one-fifth of the papers in our review (Fig. 4). Further, that decrease seems to be compensated largely by reporting of Kappa only, a misleading and outdated measure of accuracy19 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Together, the two groups account for nearly half of all the papers. On the other hand, for about 25% of the forecasts, more than one measure of accuracy are reported (Fig. 4). Not reporting any accuracy measure or reporting only Kappa’s use as the sole accuracy measure is the most common among local forecasts compared to regional and global ones (Supplementary Fig. 6). Another prevailing issue in the urban land change forecasts is the reporting of only the agreement between reference and simulated urban at the end time point of the validation interval, and not the agreement between reference change and the simulated change during that interval21. This may be misleading because such comparison fails to describe the change over the validation interval.

An UpSet plot depicts intersections among four or more intersecting sets20. Thus, in an UpSet plot, the rows correspond to the sets (here, distinct groups of accuracy assessment approaches), and the columns to the intersections among these sets (including portions of the sets with no intersection with any other). FOM Figure of Merit, AUC Area Under the Curve, ROC Relative Operating Characteristics, TOC Total Operating Characteristic. ‘Agreement’ stands for various indices of agreement. ‘Accuracy’ includes Overall Accuracy, Producers Accuracy, Locational or Spatial Accuracy, User’s Accuracy, and Percent Correct.

Calibration and validation intervals collectively span from late 1960s to early 2020 s (Supplementary Fig. 7). However, from the mid-1980s to early 2000s and from the late 1990s to mid-2010s are the most frequently covered intervals for calibration and validation, respectively. From the mid-2010s to 2030 is the most frequently covered interval for forecasts with a steep decline after 2030 and then another after 2050. There are a few studies (n = 15), most global, that present forecasts out to 2100. Still, nearly half of all the papers do not report either a calibration or a validation interval (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 7). Furthermore, even among those that report at least one of the two, most adopt forecast horizons that are several times longer than the sum of their calibration and validation intervals (Fig. 5).

311 and 274 papers, respectively, did not report sufficient information to determine the validation and calibration intervals used. 269 reported neither calibration nor validation. The inset shows the ratio of forecast interval to the sum of validation and calibration intervals in the papers that reported a calibration and/or a validation interval, grouped by the spatial scale of analysis. The box-plots show the upper and lower quartiles and the median. The red dashed line is one-half line that corresponds to the one-half rule-of-thumb mentioned in the text. The number of papers in each group shown at the top of each corresponding box-plot.

Uncertainty is largely neglected

Nearly 60 percent (354 out of 601) of the papers did not implement any analysis to explore the implications of uncertainty either in their data or in their assumptions. Of the rest, most (n = 238) incorporated a scenario approach to address uncertainty or for policy analysis (Fig. 6; Supplementary Table 4). A few studies (n = 15) also analyzed stochasticity in their modeling framework to capture the uncertainty in the various input data or in the processes represented in their models, six of them together with scenario analysis; however, even fewer reported the range of uncertainty in their probabilistic forecasts. Implementation of scenarios and stochastic approaches have increased slowly over the past decade. Still, less than half of the studies published over the past three years of the time frame of our review did so (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Less than 40 percent of local and regional studies incorporated a scenario approach (Supplementary Fig. 9A). Papers from China had the most variety in the types of scenarios implemented followed by the US (five and four, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 9B). On the other hand, ten out of twelve global studies accounted for uncertainty in their forecasts, by employing stochasticity (three studies), scenario analysis (nine studies) or both (two studies) (see Supplementary Table 1).

Policy options in scenarios are typically defined by the researchers themselves. Only about 7% (44 papers) formulate their scenarios to understand how specific local, regional, or national plans influence urban land expansion and resulting socio-economic, environmental, or land-use implications in their respective case study locations. Of the papers that utilized a scenario approach, the SSPs inform a majority of the global papers while only a few regional and local ones utilized them (Supplementary Tables 1 and 4, Supplementary Fig. 9A).

None of the forecasts incorporated heterogeneity in urban land use

None of the studies reported forecasting different categories of urban land uses, built-up densities, or verticality of urban built-up land. Several studies, however, conducted quantitative accuracy assessment of the forecasted spatial patterns of urban land expansion (Supplementary Fig. 10). Yet, only few of them included specific mechanisms (often patch-based approaches) to specifically forecast spatial patterns of urban land expansion (see Supplementary Data 2).

Nearly half the studies do not state any particular motivation beyond forecasting urban expansion

Forty-four % of all the papers in our review did not state any explicit implication or methodological novelty (i.e., developing a new land change model or significantly altering an existing model) as their main motivation for developing the forecasts (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 11). Furthermore, their percentage among papers published each year has remained about the same over the last ten years of our study period (Supplementary Fig. 11B). Of the rest, urban impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services constitute the main motivation in nearly 16% of the papers (95 papers). Another 12% focus on more than one impact and typically in the context of trade-offs. Notably, only 3% of the papers developed forecasts of urban expansion to specifically study climate-related implications such as urban heat island effect. Those that presented a methodological improvement as their motivation made up a little over 16%.

The breakdown by motivation is broadly similar across local, regional, and global forecasts (Supplementary Fig. 9A). Among the local case-study locations though, those in China collectively present the widest diversity of motivation (Supplementary Fig. 9B). Case studies from China constitute the largest share of those studies with an emphasis on loss of croplands as well as among those that highlight biodiversity or other ecological impacts, climate-related impacts, or trade-offs (typically between environmental protection vs. economic development) of forecasted urban land expansion. Case studies from the U.S. follow China in terms of the diversity of motivation. In contrast, most studies from the rest of the world did not state a clear motivation beyond forecasting future urban land expansion.

Discussion

Our findings highlight that, despite large increases in the number of forecasts published every year, developing a robust understanding of future urban land expansion and of its social, economic, and environmental consequences remain elusive for at least five reasons: 1) the dramatic unevenness in coverage of urban forecasts across countries at varying stages of urban development, and across city sizes; 2) lack of rigor in accuracy assessment; 3) insufficient recognition of uncertainty; 4) lack of representation of heterogeneity in urban land uses and spatial patterns; and 5) lack of a clear purpose behind forecasts. We also identify five major strategies to address these issues.

First, there is a dramatic unevenness in the coverage of urban forecasts across countries at different stages of urban development and across cities of varying sizes. While the global forecasts provide a well-rounded understanding on broad patterns of future urban expansion across the world and at large regional and continental scales, there is huge unevenness in geographical distribution of local urban land change forecasts (Fig. 2). Gaps in geographic coverage are especially acute where urbanization has been and expected to continue to be rapid such as Sub-Saharan Africa22 but also in Central and South America23. There is also an undue emphasis on forecasting physical expansion of large cities at the expense of those with small to medium population sizes (i.e., less than 2 million in population) (Fig. 3). Small-sized urban areas with fewer than 1 million people already account for nearly 60% of the world’s urban population18. Furthermore, it is the small to medium sized cities that have been driving urban expansion patterns in many parts of the world over the past forty years1,24,25. One can argue that it is impractical to attain representative samples that would lead to statistically meaningful conclusions across the spectrum of all city sizes; however, what our review reveals is that even the distribution of the number of cities studied deviate from the distribution of cities across the spectrum indicating a bias towards understanding future urban land change dynamics in larger cities around the world.

Furthermore, the newer approaches and methods in model development typically come from studies from the US and China, but the production of papers seem to be mainly from the rest of the world, primarily Iran, India, and Türkiye (see Supplementary Note 1; Supplementary Figs. 3D, E, 12). While, collectively, this body of work contributes to improving our understanding and insight into future urban expansion, the uptake of the newer methods and approaches is evidently much slower compared to the increase in the number of studies.

Overall, our collective understanding remains poor regarding the likely trajectories and implications of future urban expansion in some of the most rapidly urbanizing parts of the world and contributes to the broader bias in the global production of urban data25,26. Therefore, we need urban land change forecasts conducted from a wider range of geographies and city sizes, especially across large swaths of lands where urbanization is expected to progress rapidly, for example in Sub-Saharan Africa with its own social, economic, cultural, and biophysical contextual factors27,28. These, however, should be coupled with efforts to overcome the evident disconnect between those who have the capacity to develop new models or improve the existing ones and those who may lack this capacity but have the knowledge on the local context of urban development. The Global Land Programme (https://glp.earth/), that aims to establish closer ties among interdisciplinary communities of science and practice for the study of land systems and related sustainability solutions, is a suitable venue to bridge these disconnected communities of scholars and practitioners and cultivate knowledge sharing among them.

Second, many forecasts lack rigor in their accuracy assessment. Failure to report any calibration or validation measures persists, a finding that aligns with an earlier review of calibration and validation practices in land-change modeling29. Worse, those papers that do not report any accuracy measure at all for their urban expansion forecasts and those that rely solely on Kappa still constitute about half of all papers published in the last few years. The use of Kappa as the sole measure of accuracy continues likely because the good accuracy assessment practices remain unfamiliar or impractical to a large –and growing– body of modelers30.

It is past time to move beyond misleadingly simple measures of accuracy such as Kappa and embrace tools that more correctly capture the particulars of assessing the accuracy of urban land change forecasts31. There are several methods and measures that would, compared to Kappa, give a correct indication of the extent to which a model’s output agrees with observed land change. These include estimates of per-class accuracy and the confusion matrix30. The essential principle is, however, to use measures that will be unbiased and consistent estimates of accuracy, which depends on selecting a proper sampling approach to report the reliability of the reference data, which in turn depends on the particular application32. Nonetheless, at a more fundamental level, it is also important to approach model assessment as a process of building confidence in the model and its forecasts with respect to a set of specific objectives33. As opposed to validation that tends to be interpreted as a binary decision, building confidence is a gradual process of developing trust in the output of a model that it is an adequate representation of the real-world dynamics. Such gradual confidence building, akin to model credibility34, is achieved not only through statistical tests, but it also entails creating an understandable description of the real system with the participation of all stakeholders involved35.

Third, there is insufficient recognition of uncertainty in the forecasting process. All forecasts are subject to error or variability in the data sources and implicit or explicit assumptions built into the model. Yet, there is a remarkable lack of emphasis on accounting for the uncertainty in the urban land change forecasts even though the importance of various sources of uncertainty –from stochasticity36 to incomplete knowledge on underlying processes37– in land change has long been recognized. In particular, the implicit assumption about non-stationarity (that is, assuming the past can be used to predict the future) can be a significant source of uncertainty in forecasts29,38. The false sense of certainty single forecasts of land change convey belies a blindness to variety and surprise, that can be misleading at best and costly at worst. After all, surprises, such as an economic shock, an abrupt change in policies that regulate land use, or major technological advances that may change how people commute can all significantly alter how much and what patterns of urban land change would occur where. Furthermore, regardless of how satisfactory the estimated values of the accuracy measures appear to be, the longer the forecast interval (or the larger the ratio of forecast interval to the sum of calibration and validation intervals), the wider is the cone of uncertainty associated with the forecasts.

Employing scenario analysis is a practical way to address and communicate the range of possibilities the future holds, including surprise events39. However, even when a common set of scenario narratives are employed, methodological differences including differences in assumptions employed across the studies can lead to wide disagreements among the forecasts for any given scenario. This is evident in the case of the global forecasts: while differences in the forecasts across the five SSPs reflect the range of well-documented pathways regarding future social, economic, and technological changes, the wide ranges within each SSP reflect differences in numerous methodological choices across the studies that are not always as well-documented.

Several approaches to incorporate uncertainty in LCMs have long been available, from scenario analysis40,41 to sensitivity analysis39,42 to probabilistic approaches36,43,44 to multi-model ensembles45,46. On the other hand, error propagation (or propagation of uncertainty), a long-established approach in simulation modeling to quantify contribution of variability in various parameters in a model to the variability in resulting forecasts47,48, is yet to be adopted by (urban) land change modelers. Ultimately, there is a need to develop methods that are tailored to land-change analysis49 to assess non-stationarity in spatio-temporal data50,51 and even to incorporate non-stationarity in land change forecasts. Assessing non-stationarity in the historic data would inform whether a model with non-stationary components is called for, the kinds of scenarios to be employed, and selection of the forecast horizon so that the resulting forecasts are useful to make sense of the future. The first hurdle in this respect, procuring and processing historic land-change data that are long enough to capture potential trends, seasonality, or other patterns that might indicate non-stationarity, is eased by increasing availability of remotely sensed imagery such as the freely available Landsat archive and methods that can process hundreds of images for land change mapping. Finally, more attention needs to be paid to the calibration and validation intervals in relation to the forecast horizon. A rule-of-thumb in forecasting literature, that the forecast interval should be half the length of the historical-data interval52, provides useful guidance in setting the forecast horizon in relation to the calibration and validation intervals. In essence, a humble recognition that the past only partially dictates the future should lead to more concerted efforts to reflect the inherent uncertainty in the forecasts due to our imperfect understanding of the real-world processes and due to potentially trend-bending future surprises.

Fourth, existing forecasts often fail to represent the heterogeneity of urban land uses and their spatial patterns. Only a few studies in our review attempted to explicitly forecast composition and spatial configuration of future urban land uses including built-up densities despite their importance for a range of issues from urban heat island effect53 to energy use54 to biodiversity55. Urban loss (i.e., shrinkage of urban footprint) is also not represented in the forecasts in our review. In addition to the increasing importance of accounting for future changes in spatial configuration of urban land, it is also increasingly untenable to treat all urban land uses with a single ‘urban’ label considering our improved understanding of social, economic, and political processes leading to urban land change and of social and environmental implications of composition and spatial configuration of various urban land uses across landscapes6,56,57.

Consequently, urban LCM practice needs to increasingly incorporate the richness of urban land uses and land-change patterns58. The ability to represent the heterogeneity of urban land uses and patterns is also closely related to the spatial resolution of the forecasts. We note that there are modeling studies that incorporated various urban land-uses59 or built-up densities60, however, without a focus on how in the future these might change. The approaches presented in these studies can be employed to forecast future urban land expansion patterns in more thematic detail. Depending on the spatial extent under consideration (e.g., single metropolitan area vs global) and the purpose of the study, selecting an appropriate spatial resolution will also be an important factor in the ability to adequately represent urban land heterogeneity in forecasts.

Another essential aspect of urban form in this respect is verticality. A recent study found evidence of a profound shift, particularly, in large urban areas, from spreading out towards building up in recent decades61. While there are studies on how to incorporate the vertical growth in urban LCMs62, these are in initial stages of development and a serious implementation of such an approach in a real case study remains as an important advance to be attained. The growing availability of 3D datasets of urban areas63, while challenges remain in their fidelity that need to be overcome, will surely facilitate this advance.

Finally, many forecasts are produced without a clearly defined purpose limiting their utility to inform about implications of future urban land expansion. Despite the uneven coverage of the various geographies around the world, the studies in our review potentially provide valuable information on future urban expansion trends in a diversity of contexts from around the world. However, in many cases, the implications of these forecasts are left completely unaddressed. Together with the unevenness in forecasts across geographies, and city sizes, this prevents reaching a locally based but broader understanding of the nature and scale of the likely impacts of future urban land expansion across varying geographies. For example, it has by now become clear that urban areas have already started to and will continue to bear the brunt of impacts from climate change64. Yet, only 3% of the papers in our review used the forecasts they developed to study climate-related implications of future urban land expansion.

Urban land change modeling can support efforts to imagine transformative futures for urban areas65 by providing the analytical scaffolding to test implications of these imagined futures. Given that global sustainability hinges on the multiple modes of interaction between urbanization and global change, it is important to explore broader social, economic, and ecological implications of urban land change. Important challenges await future urban environments with vital significance for sustainability: How much material and energy would be needed to construct the new urban land? How is the wildlife-urban interface expected to change across biomes and ecosystems? How will the exposure and vulnerability of urban residents and infrastructure to natural hazards likely to change? These are just a few of the outstanding challenges for which we need to develop strategies and solutions to address as our world continues to urbanize and climate change takes its hold. Urban land change forecasts could contribute to developing such strategies and solutions by informing where, how much, and in what configuration and composition we expect urban land change to occur under various future scenarios. Progress along the five areas we identified will help ensure urban land change forecasts can inform strategic decision-making across spatial scales as demanded by the multifaceted nature of the urbanization and global-change interactions.

Methods

For this review, we followed the guidelines asserted in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement66,67,68. The PRISMA 2020 Reporting Checklist is provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Search strategy

We systematically searched the Web of Science database and extracted relevant records that reported the development of spatial forecasts of urban land change. We searched for peer-reviewed journal articles written in English, indexed in Web of Science, and available online by December 31, 2022. We excluded any review articles, conference proceedings, and articles published in languages other than English. The search was restricted to articles published before December 31, 2022. The initial searches took place in August 2021, and we set a weekly alert to update with the most recent relevant publications. The final list of records was updated on October 04, 2023.

We defined a set of keywords composed of (a) type of settlements and location, (b) focus of the modeling work, (c) type of work, and (d) spatial aspect of LCM. We conducted a bibliographic analysis to examine the frequency and coverage of the keywords in relation to the search results. We calibrated the keywords to enhance the coverage and include a broad spectrum of literature focusing on LCM to forecast urban growth.

The final search strings used in Web of Science were the following (TS = Topic Search):

-

(1)

TS = (urban* OR city OR cities OR metro* OR megalo* OR built* OR settl*)

-

(2)

TS = (predict* OR project* OR forecast* OR simulat*)

-

(3)

TS = (change* OR expansion* OR growth* OR sprawl*)

-

(4)

TS = ((land* OR spati* OR spat*) AND model*)

-

(5)

TS = (1) AND (2) AND (3) AND (4)

Screening

The initial search retrieved 13,861 records from the Web of Science database. After removing the duplicate records (n = 59) from the entire list, we then screened the remaining 13,802 records in a web-based systematic review platform, Rayyan69, and excluded 12,833 records that did not explicitly state its focus on urban areas or did not include ‘urban’ ―or any other relevant terms, e.g., ‘built environment’ (see Supplementary Table 5 for detailed breakdown of records returned)― as one of the major land cover classes in the three screening fields (i.e., title, abstract, keywords). If any article failed to state the use of LCM approaches as part of the methods in the screening fields, we excluded those as well.

We then reviewed the full texts of the remaining records (n = 969) and eliminated an additional 368 articles that did not comply with these four criteria:

-

(1)

at least one spatially explicit LCM approach is used;

-

(2)

urban land is one of the land types considered;

-

(3)

used the model to forecast to a period in the future (relative to the base year);

-

(4)

does not simply re-use existing urban land forecasts that were already published in a peer-reviewed journal.

We did not include studies that used aspatial forecasts of urban land expansion including those that used classical economical-based models that generate equilibrium solutions using coarse spatial units29,70. For simplicity, we refer to the models included in our review as ‘urban LCMs’ throughout the rest of this article. We used the institutional subscription of Texas A&M University (TAMU) to Web of Science and open-access availability of any articles to access the full-text of the documents. If it is not available through any medium, we excluded those articles from the review (n = 11). After screening the full texts based on the above criteria, we were left with 601 articles. The review steps with the article numbers –total, excluded, and included– are shared in a PRISMA diagram (Supplementary Fig. 1). The citation information of the papers included in our review along with the coded information are included in Supplementary Data 2.

Data extraction

Once the selection of the papers based on the inclusion criteria was completed, we used a predesigned matrix to extract specific information from the papers. For each study, the extracted data include:

-

(1)

geographical locations of the case studies,

-

(2)

spatial and temporal scales of the forecast,

-

(3)

motivation –or purpose– of the study,

-

(4)

calibration and validation measures,

-

(5)

calibration, validation, and forecast intervals,

-

(6)

how uncertainty in the forecasts is accounted for, and

-

(7)

how spatial patterns of urban land were quantified.

For geographical locations, we extracted data on specific locations –cities, urban agglomerations with longitude and latitude– and the country. For motivation or purpose focus, we initially extracted the study objective and the work output. Based on the stated study objectives and reported results, we grouped the papers based on whether they focused solely on generating urban land change forecasts, introduced any methodological advance, or used the forecasts to study and understand certain aspects of land systems and impacts of land change. For calibration and forecast, we extracted the reported start and end years, and intervals, if any. For validation, in addition to the years and intervals, we also extracted what measure was employed to quantify the accuracy of the forecasts. Based on the methodology, we extracted addressing uncertainty in two ways –whether the modeling approach itself incorporated stochasticity or whether any scenario-based approaches were adopted to address uncertainty in forecasting. For spatial configuration and patterns of urban land, we extracted data on whether the studies used any metrics to quantify heterogeneity and connectivity, and whether they classified distinct urban land uses –i.e., high-density residential, low-density residential, commercial, and industrial. We extracted the platform used to analyze spatial configurations and heterogeneity and the metrics used in the process.

We also extracted information on specific modeling approach and whether the modeling approach used was novel. To this end, we coded modeling approaches used in the specific study, and whether they used an existing model, developed, and proposed a new methodology or modified an already developed model.

Data analysis and synthesis

To understand the spatial distribution of case studies across spatial scales, we classified the study sites into three categories –local, regional, and global– based on the location and extent of the study area. ‘Local” included all studies with specific case study locations with forecasts for a single city or metropolitan area; ‘regional’ included studies with large regional or country-scale studies; and ‘global’ included all studies with global-scale study extent. We geolocated all the unique local case study sites using longitudes and latitudes. If any study had multiple case study locations, each location was recorded. In addition to the ‘geography’ data type in Excel, we also used Google Maps and Esri ArcGIS World Geolocator as necessary. For large urban agglomerations or province/state-level studies, we used the largest cities and/or respective capital cities as the location (Fig. 2). Each of these case study locations, with their respective frequency and countries, were then mapped to visualize the geographic distribution of local case study sites and countries. We also classified the cities in the local case study sites into five categories by population size. We compared their frequency in each category to that of urban areas with a population over 300,000 people in the World Urbanization Prospect (WUP) database for the top five countries with the most case study locations as well as, all the regions and continents 71 (Fig. 3).

We categorized the papers in our review based on the stated motivation for developing the forecasts as well as their spatial and temporal scales. This information allowed us to gain insight into to the extent to which these forecasts were developed to inform addressing concerns raised in the literature in relation to the expansion of urban lands2,4. Based on the stated objectives and reported results, we grouped the stated motivation into eight categories –land cover only (i.e., no other purpose or implications was stated), methodological improvement, implications for biodiversity and ecosystems, implications for agriculture and croplands, implications for transportation, implications for climate change and carbon emissions, implications for socio-demographics, and mixed/trade-offs between at least two implications. For simplicity, we focused on the primary motivation or purpose stated in the papers.

In the context of land-change models, accuracy assessment measures the extent to which a land-change model’s outputs align with observed changes in land use and land cover over time. Thus, a high accuracy indicates that the model captures the essential processes and patterns of the system from the calibration through the validation intervals at the spatial and temporal resolutions of the analysis. Accuracy can be assessed through various statistical measures and comparisons with historical data31,32. Considering there is a wide range of accuracy assessment approaches, we were interested in the relative prevalence of these approaches among the urban land change studies. Since Kappa and Kappa-based indices are historically the most prevalent and most criticized validation measures19,72, we classified studies based on whether they used only Kappa, used Kappa with other measures, or did not employ any accuracy assessment measures at all. We also categorized the accuracy assessment measures to understand the temporal patterns in their use in evaluating the accuracy of urban land change forecasts.

Since uncertainty is associated with any predictive modeling practice, we also scrutinized the identified studies on how they addressed and incorporated uncertainty in their models. In addition to coding the forecasts in terms of whether they were stochastic and whether they were scenario-based, we categorized how the authors defined the scenarios and what type of outcome they attempted to capture with the scenarios. In classifying the scenarios, we considered whether the authors incorporated any of the IPCC or UN-defined set of scenarios –such as Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs), Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)–, incorporated a range of values for model parameters to generate varying outcomes, devised scenarios representing official policies and plans, or defined the scenarios themselves based on the study goals. Finally, we examined whether urban areas were further categorized into distinct land classes in the forecasts (e.g., high density, low density, or residential, commercial, and industrial, or formal vs informal). Complete descriptions of coding categories and corresponding data from the papers in our review are included in Supplementary Data 2. Citation information of the papers excluded during the full-text eligibility stage is provided as Supplementary Data 3.

As a supplemental analysis, we also studied the papers in terms of the modeling approaches they used (see Supplementary Note 1). To this end, we followed the modeling categorization used in the National Research Council (NRC) report on Land Change Modeling73. However, unlike the report, we kept track of machine-learning-based models as a separate category apart from other statistical approaches; since the publication of the report, the former have matured significantly to be treated separately from more conventional statistical approaches (e.g., logit regression) (Supplementary Table 6; Supplementary Figs. 12–14). Further, we also coded whether the papers in our review use an existing model (after reparameterization), modify one (i.e., going beyond reparameterization typically by modifying the underlying algorithmic structure), or propose a completely new urban LCM (Supplementary Figs. 12, 15, 16).

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files.

Code availability

All R codes and the associated data used for the analyses and to generate the figures are provided in Supplementary Code 1.

References

Güneralp, B., Reba, M., Hales, B. U., Wentz, E. A. & Seto, K. C. Trends in urban land expansion, density, and land transitions from 1970 to 2010: a global synthesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 044015 (2020).

Bai, X. et al. Linking urbanization and the environment: conceptual and empirical advances. Ann. Rev. Environ. Resour. 42, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102016-061128 (2017).

Godschalk, D. R. Urban hazard mitigation: creating resilient cities. Nat. Hazards Rev. 4, 136–143 (2003).

Seto, K. C., Golden, J. S., Alberti, M. & Turner, B. L. Sustainability in an urbanizing planet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 8935–8938 (2017).

Meyfroidt, P. et al. Ten facts about land systems for sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2109217118 (2022).

Verburg, P. H. et al. Beyond land cover change: towards a new generation of land use models. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 38, 77–85 (2019).

Meyfroidt, P., Lambin, E. F., Erb, K.-H. & Hertel, T. W. Globalization of land use: distant drivers of land change and geographic displacement of land use. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 5, 438–444 (2013).

Güneralp, B., Seto, K. C. & Ramachandran, M. Evidence of urban land teleconnections and impacts on hinterlands. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 5, 445–451 (2013).

Li, X. & Gong, P. Urban growth models: progress and perspective. Sci. Bull. 61, 1637–1650 (2016).

Wu, N. & Silva, E. A. Artificial intelligence solutions for urban land dynamics: a review. J. Plan. Lit. 24, 246–265 (2010).

Santé, I., García, A. M., Miranda, D. & Crecente, R. Cellular automata models for the simulation of real-world urban processes: A review and analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 96, 108–122 (2010).

Musa, S. I., Hashim, M. & Reba, M. N. M. A review of geospatial-based urban growth models and modelling initiatives. Geocarto Int. 32, 813–833 (2017).

Chakraborty, A., Sikder, S., Omrani, H. & Teller, J. Cellular automata in modeling and predicting urban densification: revisiting the literature since 1971. Land 11, 1113 (2022).

Kim, Y., Newman, G. & Güneralp, B. A review of driving factors, scenarios, and topics in urban land change models. Land 9, 246 (2020).

Ahasan, R. & Güneralp, B. Transportation in urban land change models: a systematic review and future directions. J. Land Use Sci. 17, 351–367 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Kwan, M.-P. & Yang, J. A user-friendly assessment of six commonly used urban growth models. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 104, 102004 (2023).

Tong, X. & Feng, Y. A review of assessment methods for cellular automata models of land-use change and urban growth. Int. J. Geographical Inf. Sci. 34, 866–898 (2020).

UN. World Urbanization Prospects 2018, http://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/ (2018).

Pontius, R. G. & Millones, M. Death to Kappa: birth of quantity disagreement and allocation disagreement for accuracy assessment. Int. J. Remote Sens. 32, 4407–4429 (2011).

Lex, A., Gehlenborg, N., Strobelt, H., Vuillemot, R. & Pfister, H. UpSet: visualization of intersecting sets. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 20, 1983–1992 (2014).

Honnef, T. & Pontius, R. G. Best practices for applying and interpreting the total operating characteristic. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 14, 134 (2025).

Pieterse, E., Parnell, S. & Haysom, G. Towards an Africa Urban Agenda, 54 (United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) and United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), 2015).

Inostroza, L., Baur, R. & Csaplovics, E. Urban sprawl and fragmentation in Latin America: A dynamic quantification and characterization of spatial patterns. J. Environ. Manag. 115, 87–97 (2013).

Bell, D. & Jayne, M. Small Cities? Towards a Research Agenda. Int. J. Urban Regional Res. 33, 683–699 (2009).

Birkmann, J., Welle, T., Solecki, W., Lwasa, S. & Garschagen, M. Boost resilience of small and mid-sized cities. Nat. N. 537, 605 (2016).

Enora, R. & Acuto, M. Global urban policy and the geopolitics of urban data. Political Geogr. 66, 76–87 (2018).

Parnell, S. & Walawege, R. Sub-Saharan African urbanisation and global environmental change. Glob. Environ. Change 21S, S12–S20 (2011).

Acuto, M., Parnell, S. & Seto, K. C. Building a global urban science. Nat. Sustain. 1, 2–4 (2018).

van Vliet, J. et al. A review of current calibration and validation practices in land-change modeling. Environ. Model. Softw. 82, 174–182 (2016).

Foody, G. M. Explaining the unsuitability of the kappa coefficient in the assessment and comparison of the accuracy of thematic maps obtained by image classification. Remote Sens. Environ. 239, 111630 (2020).

Pontius, R. G. Metrics that Make a Difference: How to Analyze Change and Error (Springer, 2022).

Olofsson, P. et al. Good practices for estimating area and assessing accuracy of land change. Remote Sens. Environ. 148, 42–57 (2014).

Barlas, Y. & Carpenter, S. Philosophical roots of model validation: two paradigms. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 6, 148–165 (1990).

Balci, O. Principles of simulation model validation, verification, and testing. Trans. Soc. Comput. Simul. 14, 3–12 (1997).

Howick, S., Eden, C., Ackermann, F. & Williams, T. Building confidence in models for multiple audiences: the modelling cascade. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 186, 1068–1083 (2008).

Tobler, W. R. A computer movie simulating urban growth in the detroit region. Econ. Geogr. 46, 234–240 (1970).

Lambin, E. F. Modelling and monitoring land-cover change processes in tropical regions. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 21, 375–393 (1997).

Prigogine, I. & Stengers, I. The End of Certainty (Simon and Schuster, 1997).

Swart, R. J., Raskin, P. & Robinson, J. The problem of the future: sustainability science and scenario analysis. Glob. Environ. Change Hum. Policy Dimens. 14, 137–146 (2004).

Huss, W. R. A move toward scenario analysis. Int. J. Forecast. 4, 377–388 (1988).

Jantz, C. A., Goetz, S. J. & Shelley, M. K. Using the SLEUTH urban growth model to simulate the impacts of future policy scenarios on urban land use in the Baltimore - Washington metropolitan area. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 31, 251–271 (2004).

Hamby, D. M. A review of techniques for parameter sensitivity analysis of environmental-models. Environ. Monit. Assess. 32, 135–154 (1994).

Wu, F. Calibration of stochastic cellular automata: the application to rural-urban land conversions. Int. J. Geograph. Inf. Sci. 16, 795–818 (2002).

Güneralp, B. & Seto, K. C. Futures of global urban expansion: uncertainties and implications for biodiversity conservation. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 014025 (2013).

Alexander, P. et al. Assessing uncertainties in land cover projections. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 767–781 (2017).

Tebaldi, C. & Knutti, R. The use of the multi-model ensemble in probabilistic climate projections. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 365, 2053–2075 (2007).

Heuvelink, G. B. M., Burrough, P. A. & Stein, A. Propagation of errors in spatial modelling with GIS. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 3, 303–322 (1989).

Gertner, G. Approximating precision in simulation projections: an efficient alternative to Monte Carlo methods. For. Sci. 33, 230–239 (1987).

Estoque, R. C. & Murayama, Y. A geospatial approach for detecting and characterizing non-stationarity of land-change patterns and its potential effect on modeling accuracy. Gisci. Remote Sens. 51, 239–252 (2014).

Yegin, M., Karakaya, G. & Kentel, E. Nonstationary frequency analysis of annual maximum flow series: climate change versus land use/land cover change. Water Resour. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-025-04277-5 (2025).

Li, J. D. & Burian, S. J. Effects of nonstationarity in urban land cover and rainfall on historical flooding intensity in a semiarid catchment. J. Sustain. Water Built Environ. 8 https://doi.org/10.1061/jswbay.0000978 (2022).

Saffo, P. Six rules for effective forecasting. Harv. Bus. Rev. 85, 122 (2007).

Zhou, X. & Chen, H. Impact of urbanization-related land use land cover changes and urban morphology changes on the urban heat island phenomenon. Sci. Total Environ. 635, 1467–1476 (2018).

Rickwood, P., Glazebrook, G. & Searle, G. Urban Structure and Energy—A Review. Urban Policy Res. 26, 57–81 (2008).

Alberti, M. The effects of urban patterns on ecosystem function. Int. Regional Sci. Rev. 28, 168–192 (2005).

Albert, C. H. et al. What ecologists should know before using land use/cover change projections for biodiversity and ecosystem service assessments. Regional Environ. Change 20, 106 (2020).

Mahendra, A. & Seto, K. C. Upward and Outward Growth: Managing Urban Expansion for More Equitable Cities in the Global South, 71 (World Resources Institute, 2019) www.citiesforall.org.

Liu, Y., Batty, M., Wang, S. & Corcoran, J. Modelling urban change with cellular automata: Contemporary issues and future research directions. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 45, 3–24 (2021).

Tang, J. Modeling urban landscape dynamics using subpixel fractions and fuzzy cellular automata. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 38, 903–920 (2011).

Raimbault, J. Calibration of a density-based model of urban morphogenesis. Plos One 13 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203516 (2018).

Frolking, S., Mahtta, R., Milliman, T., Esch, T. & Seto, K. C. Global urban structural growth shows a profound shift from spreading out to building up. Nat. Cities 1, 555–566 (2024).

Koziatek, O. & Dragicevic, S. iCity 3D: A geosimualtion method and tool for three-dimensional modeling of vertical urban development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 167, 356–367 (2017).

Chen, G., Zhou, Y., Voogt, J. A. & Stokes, E. C. Remote sensing of diverse urban environments: From the single city to multiple cities. Remote Sens. Environ. 305, 114108 (2024).

Revi, A. et al. in Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 535–612 (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Friend, R. M. et al. Re-imagining inclusive urban futures for transformation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 20, 67–72 (2016).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6, e1000097 (2009).

Moher, D. et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 4, 1 (2015).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 88, 105906 (2021).

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z. & Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 (2016).

Anas, A., Arnott, R. & Small, K. A. Urban spatial structure. J. Econ. Lit. 36, 1426–1464 (1998).

UN DESA. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision (UN, New York, 2019).

Pontius, R. G. Jr, Francis, T. & Millones, M. A call to interpret disagreement components during classification assessment. Int. J. Geographical Inf. Sci. 39, 1373–1390 (2025).

NRC. Advancing Land Change Modeling: Opportunities and Research Requirements, 152 (National Research Council, Washington, D.C., 2014).

Acknowledgements

This research was in part supported by funds from the Triads for Transformation (T3) Program of the President's Excellence Fund Initiative at Texas A&M University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.G. designed the research, led the study, secured funding, and wrote the initial draft with contribution from R.A. R.A. performed the analyses with contribution from B.G., prepared the figures, and provided additional edits. Both authors interpreted the results and approved the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Güneralp, B., Ahasan, R. Urban land-change futures: current understanding, challenges, and implications. npj Urban Sustain 6, 7 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-025-00308-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-025-00308-7