Abstract

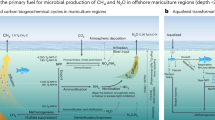

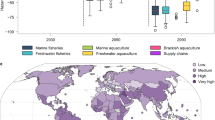

Carbon removal from the atmosphere is needed to keep global mean temperature increases below 2 °C. Here, we develop a model to explore how alkalinity production through enhanced iron sulfide formation in low-oxygen aquatic environments, such as aquaculture systems, could offer a cost-effective means of CO2 removal. We show that enhanced sulfide burial through the supply of reactive iron to surface sediments may be able to capture up to a hundred million tonnes of CO2 per year, particularly in countries with the highest number of fish farms, such as China and Indonesia. These efforts could largely offset the carbon footprint associated with their aquaculture industry. Enhanced sulfide burial could directly benefit both fish farms and surrounding ecosystems by removing toxic sulfide from aquatic systems, providing an addition to durable global CO2 removal markets and a path towards large-scale, carbon-neutral aquatic food production.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data for the areas of fish farms were obtained from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Code availability

All model code and configuration files are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13286633 (ref. 50).

References

Tollefson, J. IPCC says limiting global warming to 1.5 °C will require drastic action. Nature 562, 172–174 (2018).

Metz, B. et al. (eds) Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005).

Geden, O. An actionable climate target. Nat. Geosci. 9, 340–342 (2016).

Rogelj, J. et al. Scenarios towards limiting global mean temperature increase below 1.5 °C. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 325–332 (2018).

van Vuuren, D. P. et al. Alternative pathways to the 1.5 °C target reduce the need for negative emission technologies. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 391–397 (2018).

Schenuit, F. et al. Carbon dioxide removal policy in the making: assessing developments in 9 OECD cases. Front. Clim. 3, 638805 (2021).

Beerling, D. J. et al. Potential for large-scale CO2 removal via enhanced rock weathering with croplands. Nature 583, 242–248 (2020).

Garnett, T. Where are the best opportunities for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the food system (including the food chain)? Food Policy 36, S23–S32 (2011).

Vergé, X. P. C., De Kimpe, C. & Desjardins, R. L. Agricultural production, greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation potential. Agric. For. Meteorol. 142, 255–269 (2007).

Mrówczyńska-Kamińska, A., Bajan, B., Pawłowski, K. P., Genstwa, N. & Zmyślona, J. Greenhouse gas emissions intensity of food production systems and its determinants. PLoS ONE 16, e0250995 (2021).

Boysen, L. R., Lucht, W. & Gerten, D. Trade-offs for food production, nature conservation and climate limit the terrestrial carbon dioxide removal potential. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 4303–4317 (2017).

Moriondo, M., Giannakopoulos, C. & Bindi, M. Climate change impact assessment: the role of climate extremes in crop yield simulation. Clim. Change 104, 679–701 (2011).

Vogel, E. et al. The effects of climate extremes on global agricultural yields. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 054010 (2019).

Bach, L. T., Gill, S. J., Rickaby, R. E. M., Gore, S. & Renforth, P. CO2 removal with enhanced weathering and ocean alkalinity enhancement: potential risks and co-benefits for marine pelagic ecosystems. Front. Clim. 1, 7 (2019).

Feng, E. Y., Koeve, W., Keller, D. P. & Oschlies, A. Model-based assessment of the CO2 sequestration potential of coastal ocean alkalinization. Earth’s Future 5, 1252–1266 (2017).

Jorgensen, B. B. & Kasten, S. in Marine Geochemistry (eds Schulz, H.D. & Zabel, M.) 271–309 (Springer, 2006).

Jørgensen, B. B., Findlay, A. J. & Pellerin, A. The biogeochemical sulfur cycle of marine sediments. Front. Microbiol. 10, 849 (2019).

Reithmaier, G. M. S. et al. Alkalinity production coupled to pyrite formation represents an unaccounted blue carbon sink. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 35, e2020GB006785 (2021).

Aumont, O. & Bopp, L. Globalizing results from ocean in situ iron fertilization studies. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GB002591 (2006).

Berner, R. A. Early Diagenesis: A Theoretical Approach (Princeton Univ. Press, 1980).

Dale, A. et al. A revised global estimate of dissolved iron fluxes from marine sediments. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 29, 691–707 (2015).

Holmer, M. & Frederiksen, M. S. Stimulation of sulfate reduction rates in Mediterranean fish farm sediments inhabited by the seagrass Posidonia oceanica. Biogeochemistry 85, 169–184 (2007).

Karjalainen, J., Mäkinen, M. & Karjalainen, A. K. Sulfate toxicity to early life stages of European whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus) in soft freshwater. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 208, 111763 (2021).

Fakhraee, M., Planavsky, N. J. & Reinhard, C. T. Ocean alkalinity enhancement through restoration of blue carbon ecosystems. Nat. Sustain. 6, 1087–1094 (2023).

Tank Culture of Tilapia. The Fish Site https://thefishsite.com/articles/tank-culture-of-tilapia (2005).

MacLeod, M. J., Hasan, M. R., Robb, D. H. F. & Mamun-Ur-Rashid, M. Quantifying greenhouse gas emissions from global aquaculture. Sci. Rep. 10, 11679 (2020).

Jones, A. R. et al. Climate-friendly seafood: the potential for emissions reduction and carbon capture in marine aquaculture. BioScience 72, 123–143 (2022).

Clark, M. A., Springmann, M., Hill, J. & Tilman, D. Multiple health and environmental impacts of foods. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 23357–23362 (2019).

Hu, F. et al. Development of fisheries in China. Reprod. Breed. 1, 64–79 (2021).

Oben, B., Molua, E. & Oben, P. Profitability of small-scale integrated fish–rice–poultry farms in Cameroon. J. Agric. Sci. 7, 11 (2015).

Suplee, M. & Cotner, J. Temporal changes in oxygen demand and bacterial sulfate reduction in inland shrimp ponds. Aquaculture 145, 141–158 (1996).

Poore, J. & Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 360, 987–992 (2018).

Holmer, M. Environmental issues of fish farming in offshore waters: perspectives, concerns and research needs. Aquacult. Environ. Interact. 1, 57–70 (2010).

Pester, M., Knorr, K.-H., Friedrich, M., Wagner, M. & Loy, A. Sulfate-reducing microorganisms in wetlands—fameless actors in carbon cycling and climate change. Front. Microbiol. 3, 72 (2012).

van der Welle, M. E. W., Cuppens, M., Lamers, L. P. M. & Roelofs, J. G. M. Detoxifying toxicants: interactions between sulfide and iron toxicity in freshwater wetlands. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 25, 1592–1597 (2006).

Kappler, A., Emerson, D., Gralnick, J., Roden, E. & Muehe, E. in Ehrlich’s Geomicrobiology (eds Ehrlich, H. L. et al.) 343–399 (Taylor & Francis, 2015).

Iron Ore. Australian Government www.ga.gov.au/scientific-topics/minerals/mineral-resources-and-advice/australian-resource-reviews/iron-ore (2020).

Haque, N. in Iron Ore 2nd edn (ed. Lu, L.) 691–710 (Woodhead Publishing, 2022).

Haque, N. & Norgate, T. Life Cycle Assessment of Iron Ore Mining and Processing (Woodhead Publishing, 2015).

Yermolenko, H. Australia has lowered its iron ore price forecast for 2022–2023. GMK Center https://gmk.center/en/news/australia-has-lowered-its-iron-ore-price-forecast-for-2022-2023/ (21 December 2022).

Seven countries with the largest iron ore reserves in the world in 2019. NS Energy www.nsenergybusiness.com/features/world-iron-ore-reserves-countries/ (29 June 2021).

Nanda, S., Reddy, S. N., Mitra, S. K. & Kozinski, J. A. The progressive routes for carbon capture and sequestration. Energy Sci. Eng. 4, 99–122 (2016).

Berner, R. A. Sedimentary pyrite formation. Am. J. Sci. 268, 1–23 (1970).

Kumar, E. & Kumar, A. Optimization of pollution load due to iron ore transportation-a case study. Proc. Earth Planet. Sci. 11, 224–231 (2015).

Rennert, K. et al. Comprehensive evidence implies a higher social cost of CO2. Nature 610, 687–692 (2022).

McFadden, B. R., Ferraro, P. J. & Messer, K. D. Private costs of carbon emissions abatement by limiting beef consumption and vehicle use in the United States. PLoS ONE 17, e0261372 (2022).

Middelburg, J. J. A simple rate model for organic matter decomposition in marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 53, 1577–1581 (1989).

Katsev, S. & Crowe, S. A. Organic carbon burial efficiencies in sediments: the power law of mineralization revisited. Geology 43, 607–610 (2015).

Zeebe, R. E. & Wolf-Gladrow, D. A. CO2 in Seawater: Equilibrium, Kinetics, Isotopes (Elsevier, 2001).

Fakhraee, M. MjFakh/Fish-Farms: v1. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13905188 (2024).

Frederiksen, M. S., Holmer, M., Díaz-Almela, E., Marba, N. & Duarte, C. M. Sulfide invasion in the seagrass Posidonia oceanica at Mediterranean fish farms: assessment using stable sulfur isotopes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 345, 93–104 (2007).

Holmer, M., Duarte, C. M. & Marbá, N. Iron additions reduce sulfate reduction rates and improve seagrass growth on organic-enriched carbonate sediments. Ecosystems 8, 721–730 (2005).

Egleston, E. S., Sabine, C. L. & Morel, F. M. M. Revelle revisited: buffer factors that quantify the response of ocean chemistry to changes in DIC and alkalinity. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GB003407 (2010).

Acknowledgements

N.J.P. acknowledges funding from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the Yale Center for Natural Carbon Capture.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: M.F. and N.J.P. Methodology: M.F. and N.J.P. Investigation: M.F. Visualization: M.F. Funding acquisition: N.J.P. Project administration: N.J.P. Supervision: N.J.P. Writing—original draft: M.F. and N.J.P. Writing—review and editing: M.F. and N.J.P.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Food thanks Neill Goosen, Bob Hilton and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Sensitivity analysis, Supplementary Tables 1–4, Figs. 1–5 and References.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fakhraee, M., Planavsky, N.J. Enhanced sulfide burial in low-oxygen aquatic environments could offset the carbon footprint of aquaculture production. Nat Food 5, 988–994 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-01077-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-01077-9

This article is cited by

-

Seaweed farms enhance alkalinity production and carbon capture

Communications Sustainability (2026)