Abstract

Fruits and vegetables account for around a third of all food loss and waste. Post-harvest, retail and consumer losses and waste could be reduced with better ripeness assessment methods. Here we develop a sub-terahertz metamaterial sticker (called Meta-Sticker) that can be attached to a fruit to provide insights into the edible mesocarp’s ripeness without cutting into the produce. The fruit acts as a complex multilayer substrate to Meta-Sticker and, when excited by sub-terahertz signals, generates two distinct resonances: localized dipole resonance that correlates with the exocarp’s refractive index; and propagating plasmon resonance that penetrates into the mesocarp and resembles the rare phenomenon of ‘extraordinary transmission’. The Meta-Sticker accurately predicted the ripeness of different fruits with a cumulative normalized root mean square error of 0.54% of the produce tested. This study offers a non-invasive, low-cost and biodegradable solution for accurate ripeness assessment with applications in distribution optimization and food waste reduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

According to the United Nations, nearly half of the fruits and vegetables produced annually worldwide are wasted, which could feed more than a billion people1,2,3. In the United States, around 30–40% of the food supply is never eaten, hence wasting the resources used to produce this2,3. Besides economic consequences, food waste also has several negative environmental impacts including unnecessary landfilling and increasing the greenhouse effect4,5. Moreover, the Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that fruit and vegetable waste accounts for the greatest loss and waste among different food groups, accounting for 31.5% of production6,7. Globally, fruit and vegetable waste costs economies around US$1 trillion8. However, to date, there is a persistent lack of widely accessible and non-invasive fruit-quality/ripeness estimation technology, which would benefit both the food industry and consumers. Supplementary Note I provides details on the chemical and physiological changes that take place during ripening, and describes the limitations of existing ripeness estimation technologies, including wireless electromagnetic sensing, conventional spectroscopy and hyperspectral imaging.

Recently, the sub-terahertz (sub-THz) band, which refers to frequencies roughly between 100 and 300 GHz, has shown promise for non-invasive wireless assessment of fruit quality. First, due to their millimetre/sub-millimetre scale wavelengths, these bands offer enhanced sensing resolution compared with microwaves and lower millimetre-wave regimes9. Second, unlike light- and vision-based techniques, sub-THz signals penetrate beyond the exocarp and can assess ripeness in the mesocarp. Third, THz and sub-THz signals are sensitive to water, sugar and humidity10,11 and can correlate fruit ripening with water and sugar concentration in different layers. Fourth, sub-THz radiation is non-ionizing and hence its radiation does not damage the fruit. Finally, due to the emerging exploration of sub-THz bands for 6G communication, there exist several off-the-shelf devices that support the transmission and reception of signals in this regime12,13,14.

Despite the exciting potential of sub-THz wavelengths for fruit ripeness sensing, merely inferring ripeness from the transmission/reflection of these signals through/from the fruit is not effective. The reason is rooted in the physics of wave propagation. The high absorption loss of sub-THz signals as they traverse through the fruit prevents conventional THz spectroscopy11,15. Furthermore, the reflection of these signals from the fruit body will mostly capture exocarp signatures because the amount of refracted power that enters the mesocarp is orders of magnitude smaller (Supplementary Note I). This problem is exacerbated with rough exocarp textures which cause diffuse scattering10,16. Failing to capture mesocarp signatures remains one of the major constraints of existing non-invasive ripeness-measuring techniques. Fruit often starts to degrade from the inside: a change in water concentration in the mesocarp results in sudden changes in its quality, and bacterial–fungal attacks affect the mesocarp without showing any effect on the exocarp17. Moreover, the use of toxic chemicals, pesticides, fertilizers, adulterants, etc., primarily affects the exocarp of fruits and vegetables.

This study presents Meta-Sticker, a unique passive and low-cost solution for non-invasive fruit ripeness sensing. Meta-Sticker is a metamaterial-based printable sticker that consists of sub-wavelength metallic meta-atoms that is designed to resonate at sub-THz bands. The sticker is attached to the fruit, which acts as the substrate for the meta-atoms. This study regards fruit in a more realistic manner as a multilayer reflecting media comprising exocarp, mesocarp, etc. The metamaterial is carefully designed such that when attached to a multilayer reflective substrate (that is, fruit) it excites two distinct resonances: localized plasmon-based dipole resonance; and lattice-dependent propagating plasmon resonance. The dipole resonance has limited penetration inside the fruit and is confined inside the exocarp only. Hence, this resonance is utilized to characterize the properties of the exocarp. More interestingly, propagating plasmon resonance captures the chemical signature attributed to the mesocarp and exocarp as it can traverse deeper into the inner body of the fruit (similar to the rare phenomenon of ‘extraordinary transmission’). Because the dielectric properties of fruit vary as it matures, both resonances experience a noticeable frequency shift that can be used to infer fruit ripeness metrics.

Results

Sub-THz Meta-Sticker

Figure 1a shows a schematic of fruit multilayer sensing using the Meta-Sticker. A wireless transceiver sends sub-THz wireless signals to the passive metamaterial sticker attached to the fruit and collects the reflection profile. The image of a sample Meta-Sticker is shown in Fig. 1b. An optical microscopic image of our fabricated Meta-Sticker is shown in the inset of Fig. 1b. The specifics of the meta-atom design, simulation and fabrication are provided in Methods. The attachment of Meta-Sticker to the fruit has an ‘inverted arrangement’, implying that the metallic resonators are in direct contact with the fruit body and the base acts as a superstrate. The reason for using such an arrangement is to maximize the sensitivity of Meta-Sticker (Supplementary Note II). The high-level idea is to utilize the fruit as a natural substrate for the resonating sticker. As the dielectric properties of fruit change over time (attributed to factors such as ripening, rotting and alterations in quality), a distinctive spectral signature emerges in the Meta-Sticker’s resonances. These spectral patterns can be harnessed to deduce the fruit’s dielectric properties and mapped to the well-known quality metrics in the food industry, namely, Brix (Bx) and dry matter (DM).

a, Overview of Meta-Sticker’s operation: a sub-THz scanner excites the Meta-Sticker and captures the reflection spectra. Here, k refers to direction of propagation of sub-THz signal. E and H imply the directions of associated electric field and magnetic field components of sub-THz electromagnetic waves, respectively. b, An example of a fabricated Meta-Sticker. Inset: optical microscopic image of our fabricated Meta-Sticker. c, The measured reflection spectra of Meta-Sticker when attached to a fruit sample exhibit two resonances: localized plasmon-based dipole resonance (fDP); and propagating plasmon resonance (fPP). d, Simulated electric field distribution inside the fruit at different resonances fDP and fPP. The result shows that fDP captures the local exocarp-level information while the plasmon penetration is much deeper for fPP, providing insights into the physiology of the interior of the fruit.

Resonance profiles of Meta-Sticker

The careful design of meta-atoms combined with the unique dissipative multilayer medium of the fruit as the substrate creates two fundamentally distinct resonances when Meta-Sticker is excited (Fig. 1c): localized plasmon-based dipole resonance (fDP), which is excited at around 121 GHz; and lattice-dependent propagating plasmon resonance (fPP), which is excited at around 222 GHz. Resonance frequencies vary depending on the fruit quality across different varieties. Interestingly, these two resonances have different effective penetration depths into the fruit, and they provide complementary information about the fruit’s condition. To better understand the utility of these resonances to characterize fruit’s multilayers, Fig. 1d illustrates the simulated electric field distributions of Meta-Stickers at fDP and fPP frequencies. As shown, for fDP, plasmons are mostly confined to the exocarp, near the individual meta-atoms (and hence are termed localized plasmons). In contrast, for fPP, plasmons penetrate deeper into the fruit and across the fruit surfaces (and hence, are termed propagating plasmons); thus, they can carry information about dielectric changes attributed to ripening in the mesocarp. The exact penetration depth of the propagating plasmon depends also on the geometry of the meta-atoms. In Meta-Sticker, we have used cut-wire resonators because these can capture the maximum signature from the depth of the fruit by its resonance (plasmon penetration). The factors considered and relevant discussions regarding the choice of resonating geometry can be found in Supplementary Note III.

As the fruit ripens, both resonances shift, a signature that we use for inferring the underlying Bx and DM. In general, fDP mostly captures the signature of chemical changes in the exocarp, while fPP captures the signatures of both the exocarp and mesocarp. Next, we characterize a model for both resonances as a function of the refractive indices at the various layers of the fruit (natural substrate). As shown in Fig. 1d, left, the induced plasmons for fDP are mostly localized on the exocarp. Indeed, our simulation analysis suggests that the plasmon penetration depth of fDP lies within 100 µm when the exocarp’s refractive index is 2.0–4.0 (ref. 18). This can be seen from our microscopic imaging of various types of fruit, which reveals exocarp thicknesses of around 170 µm (for pear) to 450 µm (for mango) (Supplementary Note IV). This confirms that the fundamental resonance fDP primarily characterizes the chemical changes happening inside the exocarp. We can write fDP as follows:

where Ls and Cs are the effective inductance and capacitance, respectively, of the meta-atoms; f0 is the fundamental resonance frequency of Meta-Sticker in free space (not attached to the fruit); and neff is the effective refractive index (as seen through fundamental resonance), which can be written as

where nEx and nsuper are the effective refractive indices of the exocarp and superstrate (that is, paper), respectively. This is because the periodic meta-atoms are sandwiched between the superstrate and the peel (exocarp) of the fruit.

Next, we investigate the nature of the propagating plasmon resonance (fPP). This resonance imprints the plasmonic response to the depth of the substrate, specifically inside the mesocarp of the fruits (Fig. 1d, right). In terms of its excitation, such resonance (fPP) is generated due to the strong interaction between neighbouring meta-atoms and the induction of surface plasmons. The plasmons generate secondary electric fields that enhance the signal transmission inside the fruit. Such behaviour is analogous to the rare phenomenon of ‘extraordinary transmission’ that is usually observed in perforated metallic sheets19,20. This phenomenon also violates Bathe’s classical aperture theory. It is worth noting that such a phenomenon is usually not observed in conventional metallic or plasmonic metasurfaces21. However, in our case, when meta-atoms are directly attached to the fruit (which is a partially conducting multilayered substrate), the entire arrangement forms a multireflecting cavity22. Now, depending upon the constructive interference between the reflection waves coming from multiple partially conducting layers of the fruit, the effective reflection is enhanced at a specific wavelength. In Meta-Sticker, this surface lattice resonance can be modelled using the following relation20:

where i ,j are the integers that define the orders of diffraction in meta-atoms, c is the speed of light in free space and P is the periodicity of Meta-Sticker’s resonators. nPP is the effective substrate refractive index, which is characterized by resonance fPP and can be written as:

where χ is the flesh (mesocarp) contributing factor (FCF, as seen by the frequency fPP). Note that the FCF captures the ability of propagating plasmon resonance (fpp) to infer the signature of the mesocarp regime. A higher value of FCF implies better penetration of wireless signals to the depth of the mesocarp, and vice versa. In other words, the FCF signifies the effective sub-THz absorption characteristics in the exocarp regime. For a lower absorption of exocarp, one would expect a larger value of χ, and vice versa.

According to equations (1)–(4), extracting the refractive index of the inner mesocarp (that is, nMe) from the measured fPP and fDP requires knowledge of the FCF (that is, χ), which is itself unknown in practice. In particular, the FCF is a non-linear function of the refractive indices (nEX, nMe) and the peel thickness (dEx). Therefore, if dEx is known, the only unknown parameter will be nMe. We emphasize that estimating the thickness of the peel is straightforward and can be inferred from temporal analysis of the reflection profile, that is, \({d}_{\mathrm{Ex}}=\frac{c{\tau }_{\mathrm{Ex}}}{2{n}_{\mathrm{Ex}}}\), where τEx is the time delay between the first and second reflection time pulses.

Therefore, the only unknown parameter in equation (4) is the refractive index of the mesocarp. Because there is no closed-form equation for χ, we conduct EM simulations of our Meta-Sticker attached to a two-layer substrate with estimated nEx and dEx for the exocarp layer and the unknown value of nMe. Specifically, we find the optimum value of nMe such that the simulated propagating plasmon response is closest to the corresponding measured profile:

where \({\widetilde{f}}_{\mathrm{PP}}\) and fPP are the propagating plasmon resonance frequencies obtained from simulation and measurement, respectively. Figure 2a summarizes our ripeness inference framework. As explained above, our scheme maps the reflection spectra of Meta-Sticker to the layered refractive index of peel and flesh. In practice, the well-adopted ripeness metrics in the food industry are Bx and DM. Hence, we translate \({\widetilde{n}}_{\mathrm{Me}}\) to Bx and DM using linear regression. The exact form of the regression model is dependent on the type of fruit and requires a one-time calibration.

a, A block diagram of our end-to-end system: a sub-THz scanner measures the reflected signal from the Meta-Sticker. We extract the localized plasmon (dipole) and the propagating plasmon resonances in the reflection spectra. The two-resonance phenomenon occurs due to the inhomogeneous and dissipative dielectric properties of the fruit as the substrate for Meta-Stickers. We translate the measured resonances to the refractive index of the exocarp and mesocarp layers, providing an in-depth and non-invasive insight into the physiological stage of the fruit’s multilayers. Finally, the refractive indices of the mesocarp are mapped to well-known fruit quality metrics (Bx and DM) to estimate the ripeness of the fruit. b, Our experimental set-up for collecting reflection signals from fruits over 20 days from 30 different persimmons, pears and mangoes.

Implementation

We evaluate the performance of Meta-Sticker through extensive over-the-air experiments using 30 fruits (persimmons, pears and mangoes; 10 samples of each fruit) to represent a variety of structures, surface properties and exocarp thicknesses. We note that our approach can be applied to other kinds of fruit, yet more measurements are needed to accurately translate the Meta-Sticker resonances to ripeness metrics for each desired fruit type. Figure 2b shows our experimental rail-like set-up on which we placed different fruits. Details regarding data collection and experiment processes are given in Methods. The geometry and periodicity of the meta-atoms are optimized such that Meta-Sticker exhibits a free-space resonance of 210 GHz. The fabrication accuracy and robustness of all 30 Meta-Stickers are discussed in Supplementary Note V. We present the temporal reflection properties of fruits (persimmons, pears and mangoes) with and without Meta-Stickers in Supplementary Note VI. Our experimentally observed time pulses prove that fruits are essentially a multilayer dissipative media having distinct chemical properties and different maturity cycles (see the relevant discussions in Supplementary Note VI).

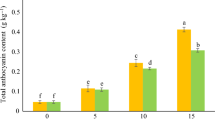

Our system relies on the frequency shift in both resonances captured by Meta-Sticker to characterize the inner ripeness or quality of the fruit. We measured the spectral profile of different types of fruits as they go through the cycle of unripe to ripe and overripe in 20 days (Supplementary Note VII). The resonance shifts for both localized dipole and propagating plasmon modes are shown in Fig. 3a,b, respectively. We see a clear reduction in the resonating frequencies, which implies an increase in the refractive index as the ripening of fruits results in the conversion of starch into sugar molecules and the breaking of large cell walls to smaller molecules that contain more water. Indeed, both fDP and fPP exhibit substantial and distinct frequency shifts (around 86–144 GHz and 210–250 GHz, respectively, across different fruits), offering unique insights into the fruit’s multilayers. Furthermore, the considerable amount of spectral variation suggests that both resonances are highly sensitive to the inherent chemical changes inside the fruit that contribute to ripening; therefore, extracting accurate ripeness metrics from such spectral patterns is indeed feasible.

a,b, The overall change in the Meta-Sticker’s dipole resonance (fDP) (a) and propagating plasmon resonance (fPP) (b). A clear reduction in resonance frequency is observed as the fruit matures. This is a result of the conversion of starch to sugar and the accumulation of water and other substances. The results indicate that there is a correlation between fruit ripeness status and the observed resonances from Meta-Sticker. c, Estimated refractive indices of exocarp during the ripening of different fruits demonstrating a monotonic increase over time and as the fruit transitions from unripe to rotten post-harvest. d–f, Estimated refractive indices of mesocarp during the ripening of persimmon (d), pear (e) and mango (f). We observe a tight correlation between the Bx readings and the estimated nMe, which indicates the potential of our estimation framework for predicting Bx. The error is higher for mango because the measured DM values do not vary while the fruit matures and rots. Such changes inside the fruit are not observed by specialized NIR sensors, possibly because the mango exocarp is much thicker and more absorptive. Notably, such changes are evident with our sub-THz Meta-Sticker, where the estimated refractive index increases consistently as the fruit ripens.

Refractive index extraction

Next, we estimate the refractive indices of fruits’ multilayers (exocarp and mesocarp) using our proposed framework. One challenge in this evaluation is to find ground truth values for refractive indices. Unfortunately, acquiring the ground truth refractive indices of exocarp and mesocarp requires an invasive process (such as extracting the juice) which itself disturbs the natural post-harvest ripening process. Instead, we exploit commercial specialized ripeness sensors with near-infrared (NIR) technology that provide the Bx or DM readings (Supplementary Note VIII). Figure 3c shows the estimated refractive index of the exocarp (nEx). An increasing trend of nEx is observed as the fruit matures, which is consistent over different types of fruits. Our findings regarding the FCF and the thickness of the exocarp are discussed in Supplementary Note IX.

Next, Fig. 3d–f demonstrates the trends of measured Bx/DM with the NIR sensor and the estimated refractive indices of mesocarp (nMe) over time and as the fruit matures post-harvest. Overall, we observe that the refractive index is highly correlated with Bx/DM. In particular, the conversion of starch to sugar during the maturing phase would yield higher Bx/DM readings and an increase in refractive index as expected (because the refractive index of sugar is higher than that of starch). Note that Bx measurements for mangoes do not show a reliable trend as these fruits mature, possibly due to the limitation of the NIR sensors to penetrate through thicker peels (Supplementary Note VIII). We further observe higher fluctuations in DM readings in mangoes. We suspect this is a limitation of the NIR sensor: NIR frequencies may not penetrate through the thick and highly absorptive exocarp of mangoes, causing higher errors. Nevertheless, the overall trend of DM is more indicative than Bx for mangoes. Hence, we have considered DM for mangoes for further analysis and ripeness estimation. However, such challenges can be alleviated substantially by using the sub-THz resonance (fPP) of Meta-Sticker (Supplementary Note X). Therefore, from Fig. 3, we can conclude that ripening causes prominent physiological changes in the mesocarp that are well captured by extracting the refractive index of the mesocarp.

Ripeness estimation

Finally, we exploit linear regression to map nMe to Bx/DM. Specifically, we exploit 90% of the collected samples (selected randomly) to extract the regression parameters and test our accuracy in Bx/DM prediction on the remaining samples. We repeat this process ten times (each time randomly choosing the training set again) and report the average of estimates in Fig. 4 against the ground truth values. We observe an overall agreement between the two. More specifically, for persimmons, we achieve a normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) of 0.33%. Similarly, the NRMSE values are 0.81% and 0.48% for pears and mangoes, respectively. Interestingly, the estimation accuracy is not uniform during different fruit ripeness cycles. In particular, we observe higher errors during the first 100 h and also after 350 h of measurements. This might be because the NIR sensor we used is optimized for use in the ripening cycle and might not provide accurate results when the fruit unripe or during the post-ripe (rotting) phases. The limitation of NIR sensing becomes more evident for thicker exocarps (for example, mangoes), for which it shows an almost negligible variation of DM values over 20 days between unripe and rotten (Fig. 4c). The above arguments are also validated by the coefficient of determination (R2) estimation, which provides a statistical estimate of how our model predicts the real Bx and DM values. R2 can be calculated by the simple formula given in ref. 23. We achieve R2 of 0.9369, 0.9597 and −9.8554 (up to four decimal places) for persimmons, pears and mangoes, respectively. The R2 value of mangoes also highlights the limitation of NIR sensing for thicker exocarp fruits. Interestingly, Meta-Sticker provides a definite advantage over the NIR sensor by capturing the ripeness signature of the mesocarp that estimates the timestamp of measurement with reasonable accuracy of NRMSE ≈ 9.88% and R2 ≈ 0.8509 (Supplementary Note X). Indeed, the consistent spectral shift of Meta-Sticker despite the higher thickness of mangoes is a testament to its robust performance. Nevertheless, the accepted quality estimation error in the food industry is 10% (ref. 24). The average NRMSE error of our proposed technique is 0.54% on average, which has a negligible impact on taste and is imperceptible to consumers. This accuracy is achieved despite the low-cost and non-invasive nature of our proposed Meta-Sticker.

a–c, Ripeness of persimmon (a), pear (b) and mango (c) in terms of Bx (a,b) and DM (c) as measured by Meta-Sticker.

Discussion

Meta-Sticker provides a non-invasive, scalable and accurate solution for fruit multilayer characterization. This periodic sub-THz resonating sticker is attached to the fruit, which acts as its substrate and excites two resonances (namely dipole resonance (fDP) and propagating plasmon resonance (fPP)) with distinctive penetration properties. Meta-Sticker probes the different layers (exocarp and mesocarp) of fruits, providing multiple consecutive reflection pulses in the temporal domain. Through modelling, simulation and experimental evaluations, we have demonstrated that changes in fruit quality (ripeness), the thicknesses of the various layers of the fruit, and the layers’ refractive indices are captured with Meta-Sticker. We optimized the meta-atom architecture for maximum sensitivity with respect to the underlying substrate. We showed that the resonance profile is solely a function of the substrate and the geometry of meta-atoms and not environmental factors such as fruit distance and orientation, which makes this approach a promising solution for mobile handheld devices. Meta-Sticker is an ultralow-cost, flexible and biodegradable tool for non-destructively characterizing the different constitutive layers of fruits, vegetables and plants, and for estimating the quality of various agricultural and commercial products with reasonable accuracy.

Most importantly, contrary to all existing strategies, the approach presented in this study enables independent inferences at different layers of fruits (exocarp and mesocarp) in a non-invasive manner. In other words, this approach extracts the ripeness of the edible regime (mesocarp) by decoupling the contribution of the exocarp layer from the dielectric inferences. Furthermore, our previous study25 demonstrated the potential of using low-cost stickers to enhance the induced dipole moment leading to valuable inferences about the exocarp of fruits. The accuracy of such inferences is comparable to THz reflection spectroscopy of the bare fruit body, albeit demanding much less spectral bandwidth. However, our previous effort only utilized the fundamental or localized dipole mode, and hence was limited to tracking the outer layer of fruit (that is, the exocarp). In contrast, this study takes a major step forward by enabling non-invasive mesocarp information extraction (leveraging the observed unique phenomenon of propagating plasmon response), which has remained unsolved by conventional reflection spectroscopy or our previous study. We provide a thorough description of the comprehensive modelling of this phenomenon, extensive simulations, details of Meta-Sticker fabrication and large-scale experiments.

Methods

Meta-Sticker fabrication

We fabricate the Meta-Sticker using a commercially available laminator and a toner-based laser printer by exploiting a technique called hot-stamping. This is a low-cost and easily deployable technique to fabricate patterned aluminium film on any flexible dielectric substrate such as papers, polymers and plastics26. The fabrication process is shown in Supplementary Note XI. First, we print patterns on glossy paper with a laser printer. Then, we attach lamination foil on the top of the paper (aluminum layer should be directly in touch with the toner). We pass the combined paper and foil through a laminator a few times for the best fabrication performance. Due to the induced heat in the laminator, the aluminium powder/film sticks to the toner and is eventually imprinted on the paper. Once we tear the aluminium foil, we can observe the desired wire-shaped patterns of aluminium. Our fabricated Meta-Sticker has a surface area of 3.07 × 3.07 cm2 to capture the entire incident THz beam spot. Meta-Stickers can be easily produced at scale using this method and could be deployed in grocery stores and other commercial places for monitoring fruit quality. We note that other flexible and transparent materials (such as plastic) can also be used as the sticker base. We chose paper because of the ease of fabrication; in addition, aluminium adheres better to glossy paper (versus normal paper), particularly with a low-cost office printer. The aluminium resonators are safe if consumed in reasonable quantities27. For the final version of Meta-Sticker used for our experiments, we fabricated and characterized 30 Meta-Stickers, each containing 50 × 50 meta-atoms with sub-wavelength cut-wire geometry having dimensions of two-dimensional periodicity (P) = 614 µm, length of wires (l) = 528 µm and width of wires (w) = 127 µm. Our Meta-Sticker is arranged on a flexible base that offers low cost and scalability. In addition, the paper is transparent in the sub-THz regime and results in negligible loss. We emphasize that the free-space response of Meta-Sticker includes only one resonance, but when these metasurfaces are attached to a multilayer fruit body, they exhibit two resonances with distinct characteristics. Moreover, the Meta-Sticker is flexible and is therefore bent when attached to the surface of a fruit. This may cause slight variation in the incident angle of sub-THz waves at different parts of the sticker. However, given the small form factor of Meta-Sticker, such variations are inherently limited. Furthermore, the resonance profile of Meta-Sticker is shown to be robust to small variations in incident angle and random configuration of the THz scanner with respect to the fruit (Supplementary Note XII).

Sub-THz scanner

We use a co-located sub-THz time domain spectroscopy transmitter and receiver to scan the spectral pattern of Meta-Sticker (Supplementary Note XI). This system produces an ultrashort pulse with a flat frequency response from 50 to 400 GHz with a spectral resolution of 1.22 GHz and a polarization extinction ratio of 20:1. The average output power from the transmitter is approximately 400 nW. Raw time-domain samples are collected and conventional signal-processing techniques such as averaging, time filtering and fast Fourier transform (FFT) are also applied to the obtained signals received from both bare fruits and the attached Meta-Stickers. We have created a rail-like set-up (Fig. 2b) to keep the location and orientation of fruit fixed over days. The fruits are placed on a polystyrene (transparent to sub-THz frequencies28) platform in random (but fixed) orientations. During the experiment, data are collected from the fruits every 12 h over 20 consecutive days. For each fruit, we have collected the reflected signals from the Meta-Sticker attached to the body of the fruit. We have also collected the reflection profile of the bare fruit body (without Meta-Sticker) for comparison. For each fruit category, we have collected 800 measurements, which accounts for a cumulative 1.7 terabytes of data to measure and process during this experimental campaign. We have made the dataset available online29. The experimentally obtained raw THz time-domain reflection signals are analysed using the commercial software MATLAB v.R2021a. Our inference framework incurs negligible computational load because it involves low-complexity signal-processing techniques, including FFT, peak detection and a precalibrated linear regression model. The fabrication cost of our Meta-Sticker (without mass production) is extremely low (a few cents). The computational cost is also negligible given the low-profile signal processing, that is, performing n-point FFT followed by resonating peak detection. We note that the sub-THz band has only recently been opened up by the Federal Communications Commission for 6G wireless transmission; hence, the commercially available transceivers (to scan Meta-Stickers) are not as mature as those for the visible-light and NIR regimes. Having said that, we believe that given widespread interest in sub-THz bands for 6G wireless networks30,31 and active research in sub-THz CMOS transceivers32,33, mobile transceivers will become pervasive in the near future. Indeed, early transceiver prototypes already exist for the band of interest34,35,36,37.

Meta-Sticker simulation

We numerically investigate the reflection characteristics of cut-wire resonators (as used in Meta-Sticker) using commercial electromagnetic simulator software (CST Studio Suite, release version 2022.00, 23 August 2021). We simulated our structure using unit-cell boundary conditions for all the necessary considerations throughout this study and by using a frequency-domain solver. Far-field reflection is calculated with a Floquet port modelled with an ‘open (add space)’ boundary condition along the propagation direction with the background as a lossless air medium. For the calculation of the electric field at both fDP and fPP, we have examined the x–z cross-section, where wave propagation is along the z axis and incident polarization is along the y axis. Here, we have shown two adjacent resonators of our periodic geometry. In this manner, with the x–z cross-section, we depict the plasmons that are excited at periodic resonators and their near-field (inter-unit cell) interactions. The constant y plane for this calculation is set at the edge of the unit-cell cut-wire resonator, that is, y = +528/2 μm, where the length of the cut-wire is 528 μm and y = 0 is considered to be the centre of the cut-wire meta-atom.

Statistics and reproducibility

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in a previous publication25 and capture the breadth of fruit varieties. No data were excluded from the analyses. The experiments were not randomized. Data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The processed data generated in this study are available from figshare via https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27299859 (ref. 29). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

We have not developed custom codes for this manuscript. The code is available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

WFP. 5 facts about food waste and hunger. https://www.wfp.org/stories/5-facts-about-food-waste-and-hunger#:~:text=One%2Dthird%20of%20food%20produced,to%20feed%20two%20billion%20people (2020).

Melgar, D. How much food waste does America create and what can we do about it? https://pirg.org/articles/how-much-food-does-america-waste-and-what-can-we-do-to-stop-it/#:~:text=And%20according%20to%20the%20United,don't%20end%20up%20using (2023).

Food waste. https://www.goruvi.com/blogs/news/644-million-tons-of-wasted-fruits-and-veggies-each-year (2023).

Ritchie, H. Food waste is responsible for 6% of global greenhouse gas emissions. https://ourworldindata.org/food-waste-emissions (2020).

Istif, E. et al. Miniaturized wireless sensor enables real-time monitoring of food spoilage. Nat. Food 4, 427–436 (2023).

Malhotra, S. International day of zero waste: reducing loss and waste in fruit and vegetable supply chains. https://www.ifpri.org/blog/international-day-zero-waste-reducing-losses-fruit-and-vegetable-supply-chains (2023).

Tackling Food Loss and Waste: A Triple Win Opportunity. https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/FAO-UNEP-agriculture-environment-food-loss-waste-day-2022/en (FAO, 2022).

Bérengère, S. & Nair, A. Addressing the impacts of food loss and waste: climate change, food security, and the global economy. https://fpanalytics.foreignpolicy.com/2022/12/06/addressing-the-impacts-of-food-loss-and-waste/ (2023).

Koch, M., Mittleman, D. M., Ornik, J. & Castro-Camus, E. Terahertz time-domain spectroscopy. Nat. Rev. Methods 3, 48 (2023).

Jornet, J. M., Knightly, E. W. & Mittleman, D. M. Wireless communications sensing and security above 100 GHz. Nat. Commun. 14, 841 (2023).

Huang, H. et al. Terahertz spectral properties of glucose and two disaccharides in solid and liquid states. iScience 25, 104102 (2022).

Vitaly, P., Kurner, T. & Hosako, I. IEEE 802.15. 3d: first standardization efforts for sub-terahertz band communications toward 6G. IEEE Commun. Mag. 58, 28–33 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. A tutorial on terahertz-band localization for 6G communication systems. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 24, 1780–1815 (2022).

Ghasempour, Y., Shrestha, R., Charous, A., Knightly, E. & Mittleman, D. M. Single-shot link discovery for terahertz wireless networks. Nat. Commun. 11, 2017 (2020).

Markelz, A. G. & Mittleman, D. M. Perspective on terahertz applications in bioscience and biotechnology. ACS Photonics 9, 1117–1126 (2022).

Ma, J., Shrestha, R., Zhang, W., Moeller, L. & Mittleman, D. M. Terahertz wireless links using diffuse scattering from rough surfaces. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 9, 463–470 (2019).

Bouzayen, M., Latché, A., Nath, P. & Pech, J.-C. Mechanism of fruit ripening. Plant Dev. Biol.-Biotechnol. Perspect. 1, 319–339 (2009).

Hao, G., Liu J. & Hong, Z. Determination of soluble solids content in apple products by terahertz time-domain spectroscopy. In Proc. SPIE 8195, International Symposium on Photoelectronic Detection and Imaging 2011: Terahertz Wave Technologies and Applications (eds Zhang, X.-C. et al.) 819510 (SPIE, 2011).

Ebbesen, T. W. et al. Extraordinary optical transmission through sub-wavelength hole arrays. Nature 391, 667–669 (1998).

Karmakar, S., Kumar, D., Varshney, R. K. & Roy Chowdhury, D. Magnetospectroscopy of terahertz surface plasmons in subwavelength perforated superlattice thin-films. J. App. Phys. 131, 223102 (2022).

Karmakar, S., Kumar, D., Varshney, R. K. & Roy Chowdhury, D. Strong terahertz matter interaction induced ultrasensitive sensing in Fano cavity based stacked metamaterials. J. Phys. D 53, 415101 (2020).

Vaughan, J. M. The Fabry–Perot Interferometer: History, Theory, Practice and Applications (Routledge, 2017).

Bucchianico, A. D. Coefficient of Determination (R2) (Wiley, 2008).

Afzal, S. S., Kludze, A., Karmakar, S., Chandra, R. & Ghasempour, Y. AgriTera: accurate non-invasive fruit ripeness sensing via sub-terahertz wireless signals. In Proc. 29th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking Association for Computing Machinery 61, 1–15 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2023).

Karmakar, S., Kludze, A. & Ghasempour, Y. Meta-Sticker: sub-terahertz metamaterial stickers for non-invasive mobile food sensing. In Proc. 21st ACM Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems 14, 335–348 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2024).

Guerboukha, H., Amarasinghe, Y., Shrestha, R., Pizzuto, A. & Mittleman, D. M. High-volume rapid prototyping technique for terahertz metallic metasurfaces. Opt. Express 29, 13806–13814 (2021).

Klotz, K. et al. The health effects of aluminum exposure. Dtsch. Ärztebl. Int. 114, 653 (2017).

Zhao, G., Mors, M. T., Wenckebach, T. & Planken, P. C. Terahertz dielectric properties of polystyrene foam. J. Opt. Soc. B 19, 1476–1479 (2002).

Karmakar, S., Kludze, A., Chandra, R. & Ghasempour, Y. Sub-terahertz metamaterial stickers for non-invasive fruit ripeness sensing. figshare. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27299859.v1 (2024).

Akyildiz, I. F., Ahan, K. & Shuai, N. 6G and beyond: the future of wireless communications systems. IEEE Access 9, 133995–134030 (2020).

Shafie, A. et al. Terahertz communications for 6G and beyond wireless networks: challenges, key advancements, and opportunities. IEEE Network 37, 162–169 (2023).

Kissinger, D., Kahmen, G. & Weigel, R. Millimeter-wave and terahertz transceivers in SiGe BiCMOS technologies. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 69, 4541–4560 (2021).

Preez, J. D., Sinha, S. & Sengupta, K. SiGe and CMOS technology for state-of-the-art millimeter-wave transceivers. IEEE Access 11, 55596–55617 (2023).

Karakuzulu, A., Ahmed, W. A., Kissinger, D. & Malignaggi, A. A four-channel bidirectional D-band phased-array transceiver for 200 Gb/s 6G wireless communications in a 130-nm BiCMOS technology. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 58, 1310–1322 (2023).

Lee, S. et al. An 80-Gb/s 300-GHz-band single-chip CMOS transceiver. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 54, 2577–2588 (2019).

Hara, S. et al. A 76-Gbit/s 265-GHz CMOS receiver with WR-3.4 waveguide Interface. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 57, 2988–2998 (2022).

Guo, K., Chan, C. H. & Zhao, D. Analysis and design of a 0.3-THz signal generator using an oscillator-doubler architecture in 40-nm CMOS. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I 69, 2284–2296 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The US National Science Foundation (grant CNS- 2313233) supported S.K., A.K. and Y.G.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K. created the Meta-Sticker design, performed theoretical analysis and simulations, and fabricated the Meta-Stickers. All the authors contributed to the design of these experiments. S.K. and A.K. built the measurement set-up, and acquired and analysed the data. S.K. and Y.G. wrote the main manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion and writing of the manuscript. R.C. helped with the problem definition and identifying the broader impact. Y.G. led the project. All authors contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Food thanks Hong-Bin Pu, Chuan-Qi Xie and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes I–XII and Figs. 1–12.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 3

Source data for Fig. 3 (main manuscript).

Source Data Fig. 4

Source data for Fig. 4 (main manuscript).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karmakar, S., Kludze, A., Chandra, R. et al. Sub-terahertz metamaterial stickers for non-invasive fruit ripeness sensing. Nat Food 6, 97–104 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-01083-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-01083-x

This article is cited by

-

Band folding unlocks high-density hidden modes for sub-terahertz cancer cell phenotyping

PhotoniX (2026)

-

Janus meta-imager: asymmetric image transmission and transformation enabled by diffractive neural networks

PhotoniX (2025)

-

On-the-shelf fruit ripeness monitoring using sub-terahertz plasmonic stickers

Nature Food (2025)