Abstract

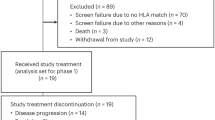

Features of constrained adaptive immunity and high neoantigen burden have been correlated with response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). In an attempt to stimulate antitumor immunity, we evaluated atezolizumab (anti-programmed cell death protein 1 ligand 1) in combination with PGV001, a personalized neoantigen vaccine, in participants with urothelial cancer. The primary endpoints were feasibility (as defined by neoantigen identification, peptide synthesis, vaccine production time and vaccine administration) and safety. Secondary endpoints included objective response rate, duration of response and progression-free survival for participants treated in the metastatic setting, time to progression for participants treated in the adjuvant setting, overall survival and vaccine-induced neoantigen-specific T cell immunity. A vaccine was successfully prepared (median 20.3 weeks) for 10 of 12 enrolled participants. All participants initiating treatment completed the priming cycle. The most common treatment-related adverse events were grade 1 injection site reactions, fatigue and fever. At a median follow-up of 39 months, three of four participants treated in the adjuvant setting were free of recurrence and two of five participants treated in the metastatic setting with measurable disease achieved an objective response. All participants demonstrated on-treatment emergence of neoantigen-specific T cell responses. Neoantigen vaccination plus ICI was feasible and safe, meeting its endpoints, and warrants further investigation. ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT03359239.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All raw DNA and RNA sequencing files are available under restricted access from the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) repository under accession code phs003922.v1.p1. Data access can be requested through dbGaP. Additional individual deidentified participant data are not available. The study protocol is available in the Supplementary Information. The remaining data are available within the article and Supplementary Information or upon request from the corresponding author. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Stein, J. P. et al. Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer: long-term results in 1,054 patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 19, 666–675 (2001).

Bajorin, D. F. et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus placebo in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 2102–2114 (2021).

Galsky, M. D. et al. Atezolizumab with or without chemotherapy in metastatic urothelial cancer (IMvigor130): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 395, 1547–1557 (2020).

Mariathasan, S. et al. TGFβ attenuates tumour response to PD-L1 blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature 554, 544–548 (2018).

Saxena, M., van der Burg, S. H., Melief, C. J. M. & Bhardwaj, N. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat. Rev. Cancer 21, 360–378 (2021).

Schumacher, T. N. & Schreiber, R. D. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science 348, 69–74 (2015).

Sahin, U. et al. Personalized RNA mutanome vaccines mobilize poly-specific therapeutic immunity against cancer. Nature 547, 222–226 (2017).

Rojas, L. A. et al. Personalized RNA neoantigen vaccines stimulate T cells in pancreatic cancer. Nature 618, 144–150 (2023).

Ott, P. A. et al. An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine for melanoma patients. Nature 547, 217–221 (2017).

Ott, P. A. et al. A phase Ib trial of personalized neoantigen therapy plus anti-PD-1 in patients with advanced melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, or bladder cancer. Cell 183, 347–362 (2020).

Weber, J. S. et al. Individualised neoantigen therapy mRNA-4157 (V940) plus pembrolizumab versus pembrolizumab monotherapy in resected melanoma (KEYNOTE-942): a randomised, phase 2b study. Lancet 403, 632–644 (2024).

Gubin, M. M. et al. Checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy targets tumour-specific mutant antigens. Nature 515, 577–581 (2014).

Marron, T. U. et al. Abstract LB048: an adjuvant personalized neoantigen peptide vaccine for the treatment of malignancies (PGV-001). Cancer Res. 81, LB048 (2021).

Rizvi, N. A. et al. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 348, 124–128 (2015).

Pant, S. et al. Lymph-node-targeted, mKRAS-specific amphiphile vaccine in pancreatic and colorectal cancer: the phase 1 AMPLIFY-201 trial. Nat. Med. 30, 531–542 (2024).

Anker, J. et al. Antitumor immunity as the basis for durable disease-free treatment-free survival in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 11, e007613 (2023).

Saxena, M. et al. PGV001, a multi-peptide personalized neoantigen vaccine platform: phase I study in patients with solid and hematological malignancies in the adjuvant setting. Cancer Discov. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-24-0934 (2025).

Kodysh, J. & Rubinsteyn, A. OpenVax: an open-source computational pipeline for cancer neoantigen prediction. in Bioinformatics for Cancer Immunotherapy: Methods and Protocols (ed. Boegel, S.) 147–160 (Springer, 2020).

Kyi, C. et al. Therapeutic immune modulation against solid cancers with intratumoral Poly-ICLC: a pilot trial. Clinical Cancer Res. 24, 4937–4948 (2018).

Robertson, A. G. et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cell 171, 540–556 (2017).

Verma, V. et al. PD-1 blockade in subprimed CD8 cells induces dysfunctional PD-1+CD38hi cells and anti-PD-1 resistance. Nat. Immunol. 20, 1231–1243 (2019).

Mørk, S. K. et al. Dose escalation study of a personalized peptide-based neoantigen vaccine (EVX-01) in patients with metastatic melanoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 12, e008817 (2024).

Latzer, P. et al. A real-world observation of patients with glioblastoma treated with a personalized peptide vaccine. Nat. Commun. 15, 6870 (2024).

Chen, X., Yang, J., Wang, L. & Liu, B. Personalized neoantigen vaccination with synthetic long peptides: recent advances and future perspectives. Theranostics 10, 6011–6023 (2020).

Alspach, E. et al. MHC-II neoantigens shape tumour immunity and response to immunotherapy. Nature 574, 696–701 (2019).

Pavlick, A. et al. Combined vaccination with NY-ESO-1 protein, poly-ICLC, and montanide improves humoral and cellular immune responses in patients with high-risk melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 8, 70–80 (2020).

Joseph, R. W. et al. Baseline tumor size is an independent prognostic factor for overall survival in patients with melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 4960–4967 (2018).

Huang, A. C. et al. T-cell invigoration to tumour burden ratio associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature 545, 60–65 (2017).

Galsky, M. D. et al. Extended follow-up results from the CheckMate 274 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, LBA443 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 alterations and response to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer. Eur. Urol. 76, 599–603 (2019).

Rubinsteyn, A. et al. Computational pipeline for the PGV-001 neoantigen vaccine trial. Front. Immunol. 8, 1807 (2017).

Roudko, V. et al. Shared immunogenic poly-epitope frameshift mutations in microsatellite unstable tumors. Cell 183, 1634–1649 (2020).

Cimen Bozkus, C., Blazquez, A. B., Enokida, T. & Bhardwaj, N. A T-cell-based immunogenicity protocol for evaluating human antigen-specific responses. STAR Protoc. 2, 100758 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Genentech provided funding for this study but had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. This work was supported in part through the computational and data resources and staff expertise provided by Scientific Computing and Data at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award grant UL1TR004419 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (to M.D.G. and N.B.). This work was also supported by the NCI of the National Institutes of Health under award number P30 CA196521 (to M.D.G. and N.B.). N.B. is an extramural member of Parker Institute of Cancer Immunotherapy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D.G., N.B. and A.R. contributed to conceptualization. J.F.A., M.S., J.K., M.M., O.H., S.A.N., H.R.S., A.R., N.B. and M.D.G. contributed to data curation. J.F.A., M.S., J.K., A.R., R.P.S., N.B. and M.D.G. contributed to formal analysis. A.M.S., N.B. and M.D.G., contributed to funding acquisition and resources. J.F.A., M.S., J.K., A.M.K., N.B. and M.D.G. contributed to investigation. J.F.A., M.S., J.K., T.O., Y.K., R.B., A.R., R.P.S., N.B. and M.D.G. contributed to methodology. M.M., O.H., N.B. and M.D.G. contributed to project administration. J.K., T.O. and A.R. contributed to software. N.B. and M.D.G. contributed to supervision. J.F.A., M.S., J.K., N.B. and M.D.G. contributed to validation and visualization. J.F.A., M.S., N.B. and M.D.G. contributed to paper preparation. All authors reviewed the paper before submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.M.S. is the chairman, CEO, scientific director and cofounder of Oncovir. R.P.S. is a paid consultant and equity holder at GeneDx and is the CEO and founder of Panacent Bio. N.B. has served as an advisor or board member for Carisma Therapeutics, CureVac, Genotwin, DC Prime, Rome Therapeutics and Tempest Therapeutics, has stock options in Genotwin, DC Prime and Vaccitech, has served as a consultant for Merck Research Laboratories, has received research support from Harbour Biomed Sciences and is an extramural member of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy. M.D.G. has received research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Dendreon, AstraZeneca, Merck and Genentech and has served as a consultant to Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, EMD Serono, SeaGen, Janssen, Numab, Dragonfly, GlaxoSmithKline, Basilea, UroGen, Rappta Therapeutics, Alligator, Silverback, Fujifilm, Curis, Gilead, Bicycle, Asieris, Abbvie and Analog Devices. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cancer thanks Roger Li, Yohann Loriot and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Sequencing pipeline and overlapping peptide selection.

a, Schematic depicting DNA sequencing of tumor and normal tissue or peripheral blood, RNA sequencing from tumor tissue, and HLA typing to vaccine peptide selection. Created in Biorender. Galsky, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/r06n376. b, Schema of overlapping peptide pools correspond to a vaccine synthetic long peptide used for stimulating PBMCs.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Neoantigen-specific T cell activity.

a, IFNγ SFCs/million plated PBMCs at each timepoint for all peptides. N = 87 for Pre, N = 87 for Prime, N = 77 for Boost, N = 47 for Post. Statistical significance was determined by Kruskal-Wallis test corrected for multiple comparisons using Dunn’s test. Adjusted P = < 0.0001 for Pre vs. Prime, Pre vs. Boost, and Pre vs. Post. The dashed line indicates the mean value at each timepoint. b, Immunogenic peptide count for each patient at each timepoint. IFNγ SFCs/million plated PBMCs for responsive peptides for each patient in the c, adjuvant or d, metastatic cohort at each evaluable timepoint. Biospecimens were not available for analysis of GU011, GU001, GU006, and GU012 at the Post timepoint, and GU010 at the Boost timepoint. Metastatic setting n = 6 patients, adjuvant setting n = 3 patients.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Baseline peptide immunogenicity.

a, IFNγ SFCs/million plated pre-treatment PBMCs for all neoantigen OLP pools. The dashed line depicts the threshold for response. Responsive peptides are labeled. n = 87 total peptides. b, IFNγ SFCs/million plated PBMCs at each timepoint for the responsive peptides identified in a. c, Flow cytometry detection of peptide responsiveness among pre-treatment CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. The dashed line depicts the threshold for response. Responsive peptides are labeled. n = 56 total peptides. d, Flow cytometry analysis at each timepoint for the responsive peptides identified in c.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Vaccine peptide hydrophobicity and immunogenicity.

Each vaccine peptide is represented in this figure by the maximum GRAVY score observed within any contiguous stretch of 7 amino acids. The plot depicts the mean with standard error of the mean. N = 48 for non-responsive peptides, N = 39 for responsive peptides. Statistical significance was determined by the two-tailed unpaired t-test. P = 0.0076.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Induction of tetanus helper peptide responses after treatment.

a, IFNγ spot forming cells (SFCs)/million plated PBMCs at each timepoint after stimulation with tetanus helper peptide. The plot depicts the mean with standard error of the mean. N = 9 for Pre, N = 9 for Prime, N = 7 for Boost, N = 6 for Post. Statistical significance was determined by Kruskal-Wallis test corrected for multiple comparisons using Dunn’s test. Adjusted P = 0.0026 for Pre vs. Prime, adjusted P = 0.0004 for Pre vs. Boost, adjusted P = 0.0085 for Pre vs. Post. b, Flow cytometry analysis of CD4+ (left) and CD8+(right) T cell response to tetanus helper peptide at each timepoint. Patients representative of each line are listed.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Induction of polyfunctional CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses.

Percent of neoantigen OLP-pools that induced a positive CD8+ or CD4+ T cell response by production of IFNγ, TNFα, or IL-2 secretion. Patients listed in blue for the adjuvant cohort, purple for the metastatic cohort. Metastatic setting n = 3 patients, adjuvant setting n = 3 patients.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Epitope mapping deconvoluting neoantigen specific T cell responses.

a, IFNγ and TNFα positive CD8+ and CD4+ T cells at baseline to C5D1 for patient GU002. Data is normalized to MOG. b, Representative flow cytometry plots for patient GU002. Percent of CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responsive OLPs for c, GU002 (N = 27 OLPs) or d, all evaluated patients. N = 5 patients, N = 141 OLPs. Peptide (Pep), overlapping peptide (OLP), myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 and study protocol.

Supplementary Table 1

List of the selected neoantigens including gene names, variant information and the peptide sequences synthesized for vaccination.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Numerical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Saxena, M., Anker, J.F., Kodysh, J. et al. Atezolizumab plus personalized neoantigen vaccination in urothelial cancer: a phase 1 trial. Nat Cancer 6, 988–999 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-025-00966-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-025-00966-7

This article is cited by

-

Progress in cancer vaccines enabled by nanotechnology

Nature Nanotechnology (2025)