Abstract

CD19-negative relapse occurs in ~30% of persons with relapsed or refractory large B cell lymphoma (LBCL) who respond to axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel; CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy). In this phase 2 single-arm study, 26 participants with chemorefractory LBCL received axi-cel in combination with rituximab. The primary endpoint was investigator-assessed complete response rate; select secondary endpoints included duration of response (DOR), axi-cel pharmacokinetics and safety. The complete response rate was 73%. Median DOR was 26.0 months; 46% of participants had an ongoing response at data cutoff. Peak CAR T cell (normalized by tumor burden) and rituximab area-under-the-curve levels were elevated in participants with complete or ongoing response. Axi-cel plus rituximab treatment led to durable responses with no new safety signals despite persistent B cell aplasia and pharmacokinetics of axi-cel were unaffected, indicating that dual targeting of CD19 and CD20 is a feasible and safe approach to potentially limit antigen escape. ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT04002401.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapies have demonstrated notable benefit in persons with aggressive, chemorefractory B cell lymphoma (BCL) for whom prognosis was traditionally poor1,2. Approximately 30–40% of persons relapse with or are refractory to standard first-line chemoimmunotherapy, with most relapses occurring within the first 2 years. A limited proportion of persons benefit from salvage high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT)3.

Axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) is an autologous CD19-directed CAR T cell therapy approved for persons with relapsed or refractory large BCL (R/R LBCL)4. Clinical benefit of axi-cel in persons with R/R LBCL after ≥2 lines of therapy was demonstrated in the pivotal ZUMA-1 trial, with an overall response rate (ORR) of 83% and a median overall survival (OS) of 25.8 months (median follow-up of 63.1 months)5. On the basis of improved event-free survival compared to standard-of-care chemoimmunotherapy in the ZUMA-7 trial, axi-cel was also approved in persons with LBCL who are refractory to or relapsed within 12 months of first-line chemoimmunotherapy6. Despite the curative potential of axi-cel for a proportion of participants with R/R LBCL, 15% of participants experienced progressive disease (PD) or stable disease (SD) as a best response and only 31% of participants had an ongoing response with axi-cel with long-term follow-up in ZUMA-1, indicating that there is a remaining unmet need for novel treatment approaches for these persons5.

Resistance mechanisms, particularly those resulting from antigen loss or modulation, may limit responses with axi-cel in some persons with R/R LBCL7,8. CD19-negative relapse occurs in ~30% of persons who have a response to axi-cel. However, biopsies obtained at relapse have shown persistent CD20 expression on tumor cells7, suggesting that CD20 may be a viable target for dual-antigen-targeting approaches designed to minimize antigen escape with CD19-directed therapies7. Recently, two CD20 × CD3 bispecific T cell-engaging antibodies were approved for the treatment of persons with R/R LBCL, indicating that strategies targeting CD20 with T cell-mediated therapies are effective for these persons (including for those previously treated with CD20-directed therapies)9,10,11. In preclinical murine models, dual targeting of CD20 and CD19 with rituximab and CAR T cells, respectively, augmented the antitumor activity of CAR T cells and mitigated loss of efficacy from CD19 antigen escape12.

Herein, outcomes are reported from the phase 2 ZUMA-14 (NCT04002401) study, the objective of which was to assess the preliminary safety and efficacy of axi-cel plus rituximab in adult participants with refractory LBCL. To support contextualization of these findings, a descriptive comparison of outcomes among participants in ZUMA-14 versus the ZUMA-1 cohort 1 (axi-cel monotherapy in participants with R/R LBCL) is included.

Results

Participants

Between November 18, 2019 and November 6, 2020, 27 participants were enrolled, of whom 26 were included in the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population (Fig. 1). One participant who was enrolled and underwent leukapheresis did not receive axi-cel treatment on study given development of a thrombus as a result of disease progression; this participant later received axi-cel as a compassionate-use therapy.

Of the 36 participants who underwent screening, 27 met the criteria for leukapheresis and 9 were deemed ineligible. At the end of study, 13 participants continued into the long-term follow-up period, 10 died (8 because of PD and 2 because of secondary malignancy), 2 withdrew consent and 1 was lost to follow-up.

At the data cutoff date of March 28, 2023, the median duration of actual follow-up (time from axi-cel infusion to death or last date known alive) was 25.1 months (range: 2.7–37.1 months). In total, 15 of 26 participants (58%) completed rituximab treatment (six doses) and 24 (92%) completed ≥3 doses. Among all participants who did not complete rituximab treatment, PD was the reason for rituximab discontinuation.

The median age was 62.5 years (range: 38–82 years); 19 of 26 participants (73%) were white, three (12%) were Asian and four (15%) were identified as ‘other’ race (Table 1). In total, 14 participants (54%) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 1. Most participants had stage III or IV disease (81%), had an age-adjusted international prognostic index (aaIPI) total score of 1–2 (85%) and were refractory to ≥2 prior therapies (73%). Five participants (19%) had primary refractory disease. Baseline characteristics of participants enrolled in ZUMA-14 and ZUMA-1 cohort 1 are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Efficacy

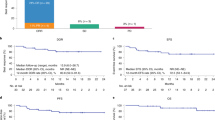

In total, 23 of 26 participants (88%) achieved an investigator-assessed objective response with axi-cel plus rituximab (Fig. 2a). For the primary endpoint, a best overall response of complete response (CR) occurred in 19 participants (73%; 95% confidence interval (CI), 52%–88%). At the data cutoff date, 12 participants (46%; all with a CR) had an ongoing response and 11 participants (42%) relapsed (Extended Data Fig. 1). At 1 month after axi-cel infusion, 73% of participants achieved CR and 42% reached partial response (PR). Seven participants (27%) converted from a PR to a CR (median time from PR to CR, 242 days (range: 75–346 days)); six of these seven participants received all six doses of rituximab. Neither of the two participants with SD converted to a CR. All PR-to-CR conversions occurred ≥100 days after axi‑cel infusion.

a, Best overall response in the mITT population (all participants treated with axi-cel and ≥1 cycle of rituximab after axi-cel treatment, n = 26). Numbers in brackets reflect the proportion of patients with the indicated response. Objective responses were assessed by the investigator per Lugano classification38. b, Kaplan–Meier estimates of DOR, PFS and OS for the mITT population.

Median duration of response (DOR) and progression-free survival (PFS) were 26.0 months (95% CI, 2.6–not estimable) and 23.6 months (95% CI, 3.4–not estimable), respectively (Fig. 2b). Event-free rates for DOR at 12 and 24 months were 65.2% (95% CI, 42.3–80.8%) and 54.5% (95% CI, 31.5–72.7%), respectively. The 12-month and 24-month PFS rates were 57.7% (95% CI, 36.8–73.9%) and 48.2% (95% CI, 27.6–66.2%), respectively. At the data cutoff date, median OS was not reached (NR) (95% CI, 25.8–not estimable; Fig. 2b). The OS rate was 76.9% (95% CI, 55.7–88.9%) at 12 months, 72.9% (95% CI, 51.4–86.1%) at 24 months and 52.2% (95% CI, 27.3–72.2%) at 36 months. Nine participants (35%) received subsequent therapies after progression with axi-cel, including rituximab or radiotherapy (n = 2 each, 8%; Supplementary Table 2). Clinical outcomes from ZUMA-1 cohort 1 in relation to those from ZUMA-14 are reported in Supplementary Table 3.

Safety

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) of any grade were reported in all 26 participants (100%; Table 2). Grade ≥3 TEAEs occurred in 24 participants (92%) and grade 5 events other than disease progression occurred in two participants (8%; both were acute myeloid leukemia). The most common TEAEs and serious TEAEs are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Prolonged cytopenias (on or after day 30) occurred in 14 participants (54%), including ten participants (38%) with grade ≥3 events. Grade ≥3 prolonged neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and anemia were reported in nine participants (35%), three participants (12%) and four participants (15%), respectively. Absolute neutrophil, lymphocyte, leukocyte, platelets and hemoglobin levels were measured from the time of leukapheresis to month 24 after axi-cel infusion. Absolute neutrophil and leukocyte levels reached nadirs on day 5 after axi-cel infusion and were largely recovered by day 10 (Extended Data Fig. 2a). A substantial decrease in lymphocytes was observed after administration of lymphodepleting conditioning therapy on day –5 that partially recovered by day 10 but remained depressed until month 24. Modest declines in hemoglobin levels (Extended Data Fig. 2b) and platelets occurred from day 0 through day 21 and day 14, respectively.

Infections occurred in nine participants (35%), including bacterial infection (n = 1, 4%; grade 1), which was also considered an AE of special interest (AESI). Grade ≥3 infections, including pneumonia (n = 3), sepsis (n = 2), COVID-19 pneumonia (n = 1), cystitis (n = 1) and viral pericarditis (n = 1), occurred in 23% of participants. Hypogammaglobulinemia, an AESI, was reported in six participants (23%), with a worst severity of grade 1–2. Six participants (23%) received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) supplementation and five (19%) received IVIG for hypogammaglobulinemia.

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) was reported in 25 participants (96%) (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 4) and all events had a worst severity of grade 1 (n = 14, 54%) or grade 2 (n = 11, 42%). The most common symptoms of CRS (≥25% of participants with CRS) were pyrexia (25 of 25, 100%) and hypotension (ten of 25, 40%). The median time to onset of the first CRS event was 4.0 days (range: 1.0–7.0 days) after axi‑cel infusion and the median duration of CRS events was 5.0 days (range: 2.0–15.0 days).

In total, 16 of 26 participants (62%) experienced neurologic events with worst severity of grade 1 (n = 10, 38%), grade 2 (n = 2, 8%) or grade 3 (n = 4, 15%). The most common symptoms of neurologic events (≥25% of participants with neurologic events) were confusional state (ten of 26, 38%) and tremor (seven of 26, 27%). The median time to onset of the first neurologic event was 6.0 days (range: 2.0–12.0 days) after axi‑cel infusion and the median duration of these events was 7.0 days (range: 1.0–39.0 days).

Steroids and tocilizumab were the most common treatments used to manage symptoms of CRS (eight of 25 (32%) and 20 of 25 (80%), respectively) or neurologic events (nine of 16 (56%) and three of 16 (19%), respectively). All CRS events and neurologic events resolved with a median time to resolution of 8.0 days (range: 4.0–16.0 days) and 12.5 days (range: 4.0–43.0 days), respectively.

Pharmacology and translational assessments

Pharmacokinetics

Peak CAR T cell levels (median: 40.3 cells per µl), area under the curve (AUC) from days 0 to 28 (AUC0–28, cells per µl × days: 376.8) and the time to peak CAR T cell expansion (median: 8 days) after axi‑cel infusion in ZUMA-14 were consistent with observations in ZUMA-1 cohort 1 (Fig. 3a). When normalized to baseline tumor burden (sum product of diameters), median peak CAR T cell levels were higher in participants who achieved a CR as a best response compared to those who achieved a PR or who had SD or PD (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Participants who had an ongoing response also had higher median peak CAR T cell levels compared to those who relapsed or did not respond (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Median rituximab levels were elevated in the blood of all participants before axi-cel infusion and increased further with additional dosing, correlating with the number of doses (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Median rituximab AUC from days −5 to 133 (AUC−5–133) was higher in participants who had a CR (2.38 × 107 ng ml−1 × days) or an ongoing response (2.35 × 107 ng ml−1 × days) at the data cutoff date compared to those who had a PR (1.41 × 107 ng ml−1 × days) or relapse (1.57 × 107 ng ml−1 × days) or did not have a response (8.16 × 106 ng ml−1 × days; SD or PD), respectively (Fig. 3b,c). Notably, in participants who received the maximum six doses of rituximab, all achieved CR and the majority remained in ongoing response (Extended Data Fig. 4b,c). Rituximab peak levels and median time to peak rituximab concentration were comparable irrespective of best overall response or ongoing response (Extended Data Fig. 4d,e).

a, Median peak CAR T cell concentrations (cells per µl) over time are shown for ZUMA-14 (blue line; n = 26) and ZUMA-1 cohort 1 (black line; n = 77). Axi-cel PK was assessed in the safety analysis population (all participants treated with axi-cel). Data are presented as median values; whiskers indicate the first and third quartiles. In ZUMA-14, median peak CAR T cell levels, AUC0–28 and median time to peak CAR T cell expansion were 40.3 cells per µl (interquartile range (IQR): 13.6–95.6), 376.8 cells per µl × days (IQR, 136.3–895.3) and 8 days (IQR, 8–8), respectively. b,c, Rituximab AUC–5–133 in blood by best response (b) and response status (c; participants with an ongoing response, those who relapsed and those who did not respond) at the data cutoff date are shown for ZUMA-14. Associations of rituximab AUC with response to therapy were analyzed in the mITT population (n = 26). One participant with ongoing response was lost to follow-up at the time of data cutoff and was excluded (from c). For b,c, box plots show the first quartile, median and third quartile and the lower and upper whiskers show the minimum and maximum values, excluding outliers, respectively.

Pharmacodynamics

Key serum analytes associated with inflammation, immune modulation, proliferation, cell trafficking and effector function were significantly induced after axi-cel infusion (measured from baseline through week 4); median peak interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, interferon (IFN)γ and IL-2 levels were increased >20 fold from baseline (Fig. 4). Several peak analyte concentrations were significantly associated with treatment-emergent grade ≥2 CRS and neurologic events (P < 0.05). IL-15, IL-6, IL-10, C–X–C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10), IL-8 and granzyme B were positively associated with grade ≥2 CRS and neurologic events in both ZUMA-14 and ZUMA-1 cohort 1. Associations between grade ≥2 CRS and peak levels of ferritin, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), IL-2 receptor alpha (IL-2Rα), IL-7 and IFNγ that were reported in ZUMA-1 cohort 1 were not observed in ZUMA-14. Likewise, associations between grade ≥2 neurologic events and peak levels of IL-2, ferritin, IL-1RA, IL-2Rα, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and granulocyte‑macrophage colony‑stimulating factor (GM-CSF) reported in ZUMA-1 cohort 1 were not observed in ZUMA-14.

The heat map depicts the median fold change of serum cytokine or chemokine levels from baseline over time (regardless of statistical significance). Analytes included are those that were elevated after axi‑cel infusion in >50% of participants, with a >2-fold change in peak level from baseline (magnitude of fold change indicated by purple shading). Median peak serum concentrations and AUC levels significantly associated with grade ≥2 CRS or grade ≥2 neurologic events in ZUMA-1 cohort 1 and ZUMA-14 are indicated with blue or gray boxes, respectively (nominal P < 0.05) and denoted with * (associated with peak levels) or ^ (associated with AUC levels) when association was observed only for one correlate. Peak serum concentration was defined as the maximum value from baseline to day 28. Nominal two-sided P values were calculated from the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, a rank-based nonparametric test for two groups (grade ≥2 versus grade 1 or none). NE, neurologic event.

B cell depletion after axi-cel treatment

The median frequency of circulating B cells was inversely proportional to median CAR T cell levels over time (Fig. 5a). B cell aplasia was more pronounced between months 3 and 12 in ZUMA-14 compared to ZUMA-1 cohort 1, as assessed by the proportion of participants who had no detectable circulating B cells (Fig. 5b). None of the evaluable participants in ZUMA-14 had detectable B cells through month 6 and 13 of 14 participants (92.9%) did not have detectable B cells at month 12. Despite more pronounced B cell aplasia through month 12, the proportion of participants with infections (any grade) through month 12 in ZUMA-14 (21.4%, three of 14) was lower compared to ZUMA-1 cohort 1 (42.9%, 12 of 28) (Fig. 5c) among evaluable participants and this lower rate of infections persisted through month 18 (33.3%, four of 12 versus 43.5%, ten of 23, respectively). The proportions of participants with hypogammaglobulinemia (any grade) were comparable among evaluable participants in ZUMA-14 and ZUMA-1 cohort 1 (month 12: 14.3%, two of 14 versus 17.9%, five of 28; month 18: 25.0%, three of 12 versus 17.4%, four of 23, respectively; Fig. 5d).

a, Median percentage B cells of leukocytes (orange) and median CAR T cell levels (cells per µl) for evaluated participants (green) over time are depicted. Data are presented as the log median ± 95% CI. For months 0.5, 1, 3 and 6, CAR T cells were specifically evaluated on days 14, 28, 105 and 180, respectively. b, Frequency of participants with no detectable circulating B cells among all evaluable participants at a given visit are shown for ZUMA-14 (blue line) and ZUMA-1 cohort 1 (black line). c, Proportion of participants with infections in ZUMA-14 (blue) and ZUMA-1 cohort 1 (black) among the total number of evaluable participants at a given visit. d, Proportion of participants with hypogammaglobulinemia in ZUMA-14 (blue) and ZUMA-1 cohort 1 (black) among the total number of evaluable participants at a given visit.

Minimal residual disease

Minimal residual disease (MRD) measured by circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) was assessed in all participants with available samples (20 of 26, 77%). Associations between MRD status and response were analyzed on day 28 and at months 3 and 5 (Supplementary Table 5). In total, 12 of 20 participants were MRD negative by ctDNA on day 28 and had a best response of CR, including three participants with subsequent relapse. Eight of nine participants (88.9%) with ongoing response at the data cutoff date had MRD negativity on day 28 and at month 3 (negative predictive value of 72.7% on day 28 and at month 3).

Among eight participants with detectable MRD at day 28, five participants had a best response of CR (n = 3) or PR (n = 2). Two of those with a CR had a late conversion from a PR on day 161 and at month 9. Four of the five participants who initially achieved a CR or PR experienced relapse by the data cutoff date. Of the six participants who initially achieved PR and later converted to CR, five attained MRD negative status at month 3 before conversion to CR, while one participant did not have a month 3 readout. The remaining two participants were MRD positive on day 28 and had disease progression within 3 months (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Receiver operator curves for ongoing response suggest that MRD positivity on day 28 (AUC = 0.7944) and at month 5 (AUC = 1.000) may predict subsequent relapse (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Among participants whose disease relapsed, MRD positivity on day 28 correctly predicted relapse in four of seven (57%) participants. In participants who did not respond to treatment, MRD positivity on day 28 predicted nonresponse in three of three (100%) participants. The positive predictive value (for participants who relapsed or who did not respond) was 87.5% on day 28, 66.7% at month 3 and 100% at month 5. For participants who were MRD positive before or at relapse, the median time from MRD detection to relapse was 45 days.

Baseline tumor transcriptomic profiling

Transcriptomic analysis of baseline tumor biopsies was performed in 13 participants, of whom five had ongoing response (CR, n = 5), six relapsed (CR, n = 5) and two were nonresponders at the data cutoff date. Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) found cytotoxicity, natural killer (NK) cell activity and receptor-related signatures to be significantly enriched in participants with ongoing response (nominal P < 0.05; Fig. 6a and Extended Data Fig. 6). Consistent with these signatures, differential gene expression analysis (DESeq) also identified individual genes related to NK or NKT cells or cytotoxicity13,14,15, including CD27, CD28 and GZMA, to be among the most differentially expressed transcripts that were upregulated in participants with ongoing response versus others, whereas individual genes implicated in protumorigenic B cell function and/or poor prognosis in diffuse LBCL (DLBCL)16,17,18,19,20,21, including BTLA and FOXP1, were downregulated (P < 0.05) in participants with ongoing response (Fig. 6b).

a, Enrichment of gene sets as defined in the Nanostring immune exhaustion panel. Data were analyzed by response status (participants with an ongoing response at the data cutoff date (n = 5) versus others (participants who relapsed and those who did not respond; n = 8)); nominal P values are reported. b, Enrichment of genes related to NK cells, NKT cells, cytotoxicity and tumorigenic B cells analyzed by response status (participants with an ongoing response at the data cutoff date (n = 5) versus others (participants who relapsed and those who did not respond, n = 8)); nominal P values are reported. c, Percentages of distinct T cell subsets in axi-cel products from participants with CR (n = 19) versus others (n = 7). In a,b, data were obtained from bulk RNA-seq evaluation of baseline FFPE tumor biopsy samples. In c, data were obtained from preinfusion axi-cel products. All box plots show the first quartile, median and third quartile and the lower and upper whiskers show the first quartile − 1.5× the IQR and third quartile + 1.5× the IQR, respectively. The association between gene set enrichment scores and participants’ ongoing response status was evaluated by performing a two-sided, unpaired t-test between the two groups. For each comparison, nominal (nonadjusted) P values are provided when significant. AP1, activator protein 1; BLNK, B cell linker; BTLA, B and T lymphocyte attenuator; CTLA4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4; DAP12, DNAX-activating protein of 12 kDa; FOXP1, forkhead box protein P1; GAB1, growth factor receptor bound protein 2-associated binding protein 1; GZMA, granzyme A; IRF4, interferon-regulatory factor 4; JAK, Janus kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; NKG7, NK cell granule protein 7; PD1, programmed cell death protein 1; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; RAR, retinoic acid receptor; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TCR, T cell receptor; TGF, transforming growth factor; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

Preinfusion product phenotyping

Consistent with prior analysis of axi-cel products in DLBCL22,23, T cell immunophenotyping of axi-cel products in ZUMA-14 showed that participants who achieved a CR had significantly higher frequencies of naive (P = 0.011) and central memory (P = 0.026) CAR T cells in their products compared to participants who did not have a CR (Fig. 6c). Whereas participants who did not have a CR had a significantly higher frequency of effector memory CAR T cells (P = 0.015) in their axi-cel products compared to those who had a CR.

Discussion

Axi-cel has demonstrated notable clinical benefit and improved survival in persons with R/R LBCL5,6; however, resistance mechanisms including antigen escape may limit successful outcomes in some persons. CD20 has been a well-established, clinically validated therapeutic target in B cell malignancies for treatments based on antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) or complement-mediated mechanisms (for example, rituximab)24. Recently, CD20 × CD3 bispecific T cell-engaging antibodies have demonstrated the success of targeting CD20 in T cell-mediated approaches for persons with LBCL9,10. An alternative approach targeting both CD19 and CD20 antigens may decrease the selection pressure for escape variants, thus minimizing antigen-negative relapse. Phase 1 studies of CD19/CD20 bispecific CAR T cells showed promising response rates and retention of CD19 expression on tumor cells in participants with R/R B cell malignancies25,26.

In ZUMA-14, axi-cel was combined with rituximab to evaluate the feasibility and safety of the CD19 and CD20 dual-targeting approach in LBCL. The 24-month OS and PFS rates in ZUMA-14 were 72.9% and 48.2%, compared to 45.5% and 32.8%, respectively, in ZUMA-1 cohort 1. Among participants with a response, the proportion remaining in response at month 24 was 54.5% in ZUMA-14 compared to 39.8% in ZUMA-1 cohort 1. The combination of axi-cel with rituximab elicited a high CR rate of 73% and durable PFS in participants with refractory LBCL, with 24 months of follow-up. Participants treated with axi-cel monotherapy in ZUMA-1 cohort 1 had a CR rate of 53%, with 24 months of follow-up. Although the efficacy reported here for ZUMA-14 appears favorable compared to ZUMA-1 cohort 1 (axi-cel in participants with LBCL), there were differences between the studies. Notably, participants in ZUMA-1 cohort 1 overall had higher risk status, more heavily pretreated disease and higher baseline tumor burden compared to ZUMA-14 (ref. 2). Further limitations of ZUMA-14 include the small sample size, a relatively limited duration of follow-up and disproportionate racial demographics, which may preclude stringent comparison of clinical results with ZUMA-1.

Incidence of grade ≥3 prolonged cytopenias (at ≥30 days after axi-cel infusion) in ZUMA-14 was similar to ZUMA-1 (38%)27, indicating that the addition of rituximab did not exacerbate the incidence of severe cytopenias. In ZUMA-14, postinfusion decreases in neutrophil and hemoglobin levels (of any grade) recovered in most participants by day 28. Despite the prolonged B cell aplasia, rates of grade ≥3 infections in ZUMA-14 (23%) were comparable to those in ZUMA-1 cohort 1 (26%)27. Use of IVIG was comparable in ZUMA-14 (23%) and ZUMA-1 cohort 1 (26%). In ZUMA-14, there were no grade ≥3 CRS events and 15% of participants had grade ≥3 neurologic events; all events resolved on study and were manageable with established treatment algorithms. Although the incidence of grade ≥3 CRS and neurologic events appeared to be improved compared to ZUMA-1 cohort 1 (grade ≥3 CRS, 13%; grade ≥3 neurologic events, 29%)5, these improvements may be because of advances in management of these well-recognized AEs since ZUMA-1 was initiated (for example, use of tocilizumab and earlier corticosteroid use)28,29.

The pharmacokinetics (PK) of axi-cel in ZUMA-14 was comparable to axi-cel monotherapy in ZUMA-1, indicating that the addition of rituximab did not impact the kinetics of in vivo CAR T cell expansion after axi‑cel infusion. Tumor-burden-adjusted axi-cel PK and rituximab exposure (AUC) showed positive associations with CR and ongoing response. This PK–efficacy relationship was consistent with the observation that the association between PK and efficacy was stronger in participants with higher tumor burden in second-line or greater LBCL6,23. As expected, the recovery of circulating B cells in participants treated with axi-cel plus rituximab was inversely proportional to CAR T cells over time.

Our analysis suggests that MRD is predictive of relapse in participants with refractory LBCL treated with axi-cel plus rituximab, although the small number of participants with MRD positivity (n = 8) limits the interpretation of this finding. This observation was consistent with the results from a prospective study evaluating MRD status as a prognostic factor for relapse with axi-cel, which showed that MRD had a positive predictive value for relapse (88%) in participants who had a PR or SD on day 28 (ref. 30). Given that the sensitivities of MRD assays in lymphoma may vary (1 × 10−4 to 1 × 10−6)31,32, standardized methods for reporting MRD may be needed. Our data support the relevance of using MRD measured by ctDNA for identifying residual disease that may predict relapse in participants with refractory LBCL.

Tumor transcriptomic analysis suggested that increased NK cell and T cell infiltration at baseline may correlate with ongoing response. The presence of NK cells may suggest that NK-cell-driven ADCC could enhance rituximab-mediated antitumor activity and act complementary to axi-cel effector function33. A deeper analysis and validation to confirm whether endogenous tumor-infiltrating NK cells may have a role in driving responses in participants treated with axi-cel plus rituximab is warranted.

Axi-cel plus rituximab demonstrated feasibility of a regimen that targets both CD19 and CD20 in participants with LBCL. Although a mechanistic understanding of CD19/CD20-negative relapses and evaluation of antigen escape are critical areas of investigation, only one paired preinfusion and postprogression (after axi-cel infusion) biopsy was obtained in this study. The limited number of samples, therefore, precluded such investigations and highlights the difficulty that investigators have generally encountered in obtaining these specimens in clinical trials of CAR T cell therapy. Dual targeting of CD19 and CD20 with bispecific CAR T cells in B cell malignancies is a treatment modality being studied to mitigate antigen escape as a resistance mechanism25,26,34. At least two different approaches to target multiple antigens using CAR T cell therapy are being investigated, including the use of either tandem or bicistronic CAR constructs34,35,36. Tandem CARs consist of two antigen-binding domains on the same CAR construct, which may lead to challenges with antigen recognition. Bicistronic CARs allow the expression of two constructs with different antigen-binding domains on the same T cell34. Both of these alternative approaches, which provide dual-targeting treatment intrinsic within the CAR design, offer distinct advantages over combinatorial treatment strategies of CAR T cell therapy with antibody-based therapy, like rituximab, as the latter involves multiple infusions and prolonged treatment duration3,9,10,35,36. KITE-363, a bicistronic CD19/CD20-directed CAR construct containing both CD28 (on the anti-CD19 CAR) and 4-1BB (on the anti-CD20 CAR) signaling domains, and KITE-753, a rapidly manufactured version of KITE-363, are currently being evaluated in a phase 1 study in participants with R/R BCL (NCT04989803)37.

Although synergistic effects from axi-cel plus rituximab were largely equivocal in this study, exploratory results from ZUMA-14 showed that axi-cel plus rituximab provided durable responses with no new safety signals in participants with refractory LBCL. Together with the translational findings, these outcomes suggest that dual targeting of CD19 and CD20 is a feasible and safe approach to potentially address the ongoing challenge of antigen escape. Overall, results from ZUMA-14 support the continued optimization of dual CD19/CD20-targeting approaches, including bicistronic CD19/CD20-directed CAR constructs, for persons with chemorefractory aggressive BCL.

Methods

Study design and participants

ZUMA-14 (NCT04002401) was an open-label, multicenter, single-arm phase 2 study in participants with refractory LBCL conducted at eight sites in the United States (a complete list of study sites, including the number of participants enrolled, is provided in Supplementary Table 6). Eligibility criteria were similar to ZUMA-1 (ref. 2). Eligible participants were ≥18 years of age with histologically confirmed LBCL and chemotherapy-refractory disease (defined as either primary refractory disease, no response to ≥2 lines of therapy or refractory disease after ASCT). The anticipated enrollment in the study was approximately 30 participants, which was qualitatively informed by the target sample size estimation to allow the safety profile of the combination treatment strategy to be elucidated; the target sample size was not a prerequisite to ending study accrual. Participants were recruited for the study by investigators at each site and enrollment was open to all eligible participants, irrespective of sex and/or gender (which were not considered in the study design). All participants provided written informed consent and this trial was conducted in accordance with ethical principles from the Declaration of Helsinki and applicable International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The study protocol and amendments were approved by the institutional review board at each participating site. The study protocol is included in the Supplementary Information.

Treatments and procedures

As previously described2, enrolled participants underwent leukapheresis at a participating treatment center to obtain T cells for axi-cel manufacturing performed at the sponsor’s facility. Bridging therapy before lymphodepletion was not permitted. Participants received lymphodepleting chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide 500 mg m−2 per day plus fludarabine 30 mg m−2 per day) for 3 days before axi-cel infusion. Axi-cel was given as a single intravenous infusion of autologous CAR T cells at a target dose of 2 × 106 CD19-directed CAR T cells per kg. Participants received rituximab (375 mg m−2) by intravenous infusion 5 days before axi-cel administration, on day 21 after axi‑cel infusion and then every 28 days for a total of 6 doses. Recommendations for the management of axi-cel-related toxicities, including CRS, neurologic events and cytopenia were provided in the investigator brochure. Recommendations for rituximab-related toxicities, including infusion reactions, were included in the package insert.

Endpoints and assessments

The primary endpoint was investigator-assessed CR rate for CRs achieved at any time during the study per Lugano classification38. Secondary endpoints included investigator-assessed ORR (defined as a CR or PR) and DOR per Lugano classification38, PFS, OS, safety and axi-cel PK. Pharmacodynamic assessments, including cytokine and chemokine profiles and associations with efficacy and safety endpoints, cytopenias and B cell aplasia were evaluated as exploratory endpoints.

AEs, including TEAEs, were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for AEs (CTCAE, version 5.0) through the end of the treatment period (until 30 days after the final dose of rituximab or 3 months after axi-cel infusion, whichever was longer). AESIs included CRS, neurologic events, prolonged cytopenia (neutropenia, thrombocytopenia or anemia present on or after 30 days after infusion) bacterial infection, hypogammaglobulinemia, secondary malignancies and autoimmune disorders. AESIs were reported for 24 months after axi-cel infusion or until disease progression, whichever occurred first (except for secondary malignancies, which are monitored for 15 years after treatment).

Tumor measurements

Tumor measurements were performed by positron emission tomography or computed tomography scans at screening or within 28 days of enrollment, as well as on day 28, day 105 and day 180.

Product characterization by flow cytometry

Axi-cel products were evaluated by flow cytometry for percentage of CD3, CD4, and CD8 T cells and also memory phenotypes (Tnaive, Tcm, Tem and Teff as defined by CCR7 and CD45RA). Testing was performed by Kite using a validated protocol. Cryopreserved samples were rapidly thawed in a 37 °C water bath and washed with cell staining buffer (BioLegend, 420201, lot B305438). Sample viability and cell density were measured using a Vi-cell. Cell densities were adjusted to 5 × 106 viable cells per ml in BioLegend cell staining buffer. Cells were aliquoted into 96-well plate at a final density of 1 × 106 viable cells per test. Cells were stained for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark with the following commercially available fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies: CD3 BV421 clone SK7 (BioLegend, 344834, lot B280578, dilution 1:200), CCR7 FITC clone G043H7 (BioLegend, 353216, lot B232796, dilution 1:40), CD45RA APC clone HI100 (BioLegend, 304112, lot B238560, dilution 1:40) and CD8 APC-H7 clone SK1 (BD Biosciences; 641400, lot 0253359, dilution 1:20). FcR blocking reagent (human; Miltenyi Biotec, 130-059-901, lot 5200703099) was added 1:8 to the antibody master mix before incubating with cells. Following incubation with antibody master mix, cells were stained with 7-AAD viability solution (BD Biosciences, 559925, lot 9179218) at 1:25 dilution with BioLegend cell staining buffer and incubated in the dark for 5 min before acquiring on a BD FACS Canto II. All primary antibodies were validated per manufacturer testing protocols, as documented within their respective technical datasheets and websites, and passed quality control testing and validation, including specificity, precision and titration (linearity). Technical datasheets for each lot can be obtained from the respective manufacturers’ website.

MRD

MRD was assessed using ctDNA on day 28 and at months 3 and 5, before analysis by next-generation sequencing using the clonoSEQ assay (Adaptive Biotechnologies). Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor biopsy samples were required for calibration and used to establish dominant rearranged IgH (variable–diversity–joining or diversity–joining), IgK or IgL receptor gene sequences tracked over time in ctDNA. MRD positivity was defined as any detectable rearrangement and MRD negativity was defined as no evidence of rearrangement. MRD positivity was reported above the limit of detection (observations were required to have 95% reproducibility).

Axi-cel PK assessments by qPCR

Blood samples for assessment of CAR T cells were obtained on the day of axi-cel infusion (day 0) and on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 14, 21, 28, 49, 105 and 180. qPCR was used to measure the presence, expansion and persistence of transduced anti-CD19 CAR+ T cells in blood. CAR T cells were assessed as previously described2,39,40,41. For each participant, DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells collected before treatment and at multiple time points after treatment. DNA was extracted using a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen). DNA from each time point was amplified in duplicate with a primer and probe set that was specific for the anti-CD19 CAR.

Assessments of rituximab PK

Rituximab PK was assessed in blood samples before and after rituximab infusion on rituximab treatment days. A validated Gyrolab assay was performed by QPS for the determination of rituximab levels in human serum.

Pharmacodynamic cytokine and chemokine assessments

Levels of analytes, including homeostatic, proliferative, proinflammatory and immune-modulating cytokines, chemokines, effector molecules and angiogenesis and acute phase proteins, were evaluated in serum samples at various time points. Blood samples were also collected for analysis on the day of hospital readmission following any axi-cel-related AEs and then weekly through and including the day of discharge. An additional sample for analyte analysis was drawn at the onset of any grade ≥3 axi-cel-related toxicity, including CRS and neurologic events, and upon resolution of the event. Blood samples were also collected for evaluation at the time of disease progression before the initiation of subsequent anticancer therapy. Because of the timing of samples collected after infusion, the calculated values for peak, AUC and time to peak are considered estimates.

Participant biospecimens were analyzed using Meso Scale Diagnostics, V-PLEX Plus assays, including Vascular Injury Panel 2 (C-reactive protein, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, serum amyloid A and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1), Cytokine Panel 1 (GM-CSF, IL-5, IL-7, IL-12/23p40, IL-15 and IL-17A), Chemokine Panel 1 (CXCL10, also known as IFNγ-induced protein 10, monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)1, also known as C–C motif chemokine ligand 2, MCP4, macrophage-derived chemokine, macrophage inflammatory proteins 1α and 1β and thymus-regulated and activation-regulated chemokine) and Proinflammatory Panel 1 (IFNγ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 and TNF). Additional serum analytes were measured using the ProteinSimple (a Bio-Techne brand) human granzyme B Simple Plex Ella assay for granzyme B, the R&D Systems (a Bio-Techne brand) Quantikine immunoassays for IL-2Rα, IL-1RA and vascular endothelial growth factor and the Roche Immunoanalyzer ferritin assay for human ferritin. IL-23 had no detectable values within the quantitative range for all participants as measured by V-PLEX Plus Th17 panel 1 (Meso Scale Diagnostics).

Bulk RNA-seq analysis

FFPE tissue slides were processed for RNA extraction using the Quick-DNA/RNA FFPE kit (Zymo Research, R1009). RNA integrity was assessed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 using the RNA 6000 Pico kit (5067-1513). Total RNA was subjected to ribosomal RNA depletion followed by library preparation using Illumina stranded total RNA prep, ligation with Ribo-Zero plus kit (20040529). Four libraries were prepared with TaKaRa Bio’s SMARTer stranded total RNA-Seq kit v3-Pico input (634489) because of low mRNA yield. Final libraries were quantified using Qubit and the quality was assessed on the TapeStation 4150 using the Agilent high-sensitivity D1000 ScreenTape assay (5067-5584) and high-sensitivity D1000 reagents (5067-5585). RNA-seq libraries were pooled and subjected to a 55-bp paired-end sequencing run using the SP flow cell on Illumina’s NovaSeq 6000 platform.

Raw FASTQ data were preprocessed with BBDuk (version 38.94) to remove excess sequencing adaptors, followed by alignment to the GRCh38 human reference genome using the STAR aligner (version 2.7.3a). Read counts obtained from STAR output were analyzed using DESeq2 and GSVA R packages to identify the differences between participants with ongoing response and those who never responded or relapsed. GSVA was carried out on gene counts normalized by the variance stabilizing transformation method implemented in DESeq2 and by selecting a panel of 47 gene signatures representative of immune and oncogenic pathways (immune exhaustion panel, as defined by NanoString Technologies). The association between gene set enrichment scores and participants’ ongoing response status was evaluated by performing a two-sided, unpaired t-test between the two groups.

Statistical analysis

Participants who received an axi-cel infusion and ≥1 dose of rituximab after axi‑cel infusion were considered evaluable in the mITT population, which was the basis for all efficacy analyses. The safety population comprised all participants treated with axi-cel. No formal hypothesis was tested in this study. Descriptive statistics are reported for all endpoints. No data points were excluded from the analyses. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but not formally tested. Time-to-event endpoints were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method. Nominal P values for statistical comparisons of peak values for the serum analytes between two subgroups were calculated from the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

To support contextualization of the data, outcomes among participants in ZUMA-14 were compared to those from ZUMA-1 cohort 1. All results were compared descriptively without balance or matching of baseline participant and disease characteristics between the studies. Data were analyzed using SAS/STAT software (version 9.4), GraphPad Prism (version 9), R (version 4.5.1 with ggplot 2 package) and Python (version 3.11). As ZUMA-14 used an open-label, single-arm trial design, randomization and blinding were not relevant to the study design. The study protocol is sufficient for replicating the trial in the future, if necessary. Replication of the results in the study is not applicable because of the descriptive nature of the analysis in which no formal hypothesis testing was performed.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Gilead Sciences shares anonymized individual participant data upon request or as required by law or regulation with qualified external researchers based on submitted curriculum vitae and reflecting non-conflict of interest. The request proposal must also include a statistician. Approval of such requests is at Gilead Science’s discretion and is dependent on the nature of the request, the merit of the research proposed, the availability of the data, and the intended use of the data. Data requests should be sent to datasharing@gilead.com. The next-generation sequencing bulk RNA-seq profiling data produced on tissue biopsies from participants in ZUMA-14 that are discussed in this publication are available at Zenodo via https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16809020 (ref. 42). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Crump, M. et al. Outcomes in refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the international SCHOLAR-1 study. Blood 130, 1800–1808 (2017).

Neelapu, S. S. et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 2531–2544 (2017).

Sehn, L. H. & Gascoyne, R. D. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: optimizing outcome in the context of clinical and biologic heterogeneity. Blood 125, 22–32 (2015).

YESCARTA® (axicabtagene ciloleucel) suspension for intravenous fusion. Highlights of Prescribing Information. (Kite Pharma, 2025); https://www.gilead.com/-/media/files/pdfs/medicines/oncology/yescarta/yescarta-pi.pdf

Neelapu, S. S. et al. Five-year follow-up of ZUMA-1 supports the curative potential of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 141, 2307–2315 (2023).

Locke, F. L. et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel as second-line therapy for large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 640–654 (2022).

Plaks, V. et al. CD19 target evasion as a mechanism of relapse in large B-cell lymphoma treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel. Blood 138, 1081–1085 (2021).

Shah, N. N. & Fry, T. J. Mechanisms of resistance to CAR T cell therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 16, 372–385 (2019).

Dickinson, M. J. et al. Glofitamab for relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 2220–2231 (2022).

Thieblemont, C. et al. Epcoritamab, a novel, subcutaneous CD3 × CD20 bispecific T-cell-engaging antibody, in relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma: dose expansion in a phase I/II trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 2238–2247 (2022).

Liu, X., Zhao, J., Guo, X. & Song, Y. CD20 × CD3 bispecific antibodies for lymphoma therapy: latest updates from ASCO 2023 annual meeting. J. Hematol. Oncol. 16, 90 (2023).

Mihara, K. et al. Synergistic and persistent effect of T-cell immunotherapy with anti-CD19 or anti-CD38 chimeric receptor in conjunction with rituximab on B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 151, 37–46 (2010).

Vossen, M. T. M. et al. CD27 defines phenotypically and functionally different human NK cell subsets. J. Immunol. 180, 3739–3745 (2008).

Stoeckle, C. et al. Cathepsin W expressed exclusively in CD8+ T cells and NK cells, is secreted during target cell killing but is not essential for cytotoxicity in human CTLs. Exp. Hematol. 37, 266–275 (2009).

Croce, M., Rigo, V. & Ferrini, S. IL-21: a pleiotropic cytokine with potential applications in oncology. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 696578 (2015).

Dekker, J. D. et al. Subtype-specific addiction of the activated B-cell subset of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma to FOXP1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E577–E586 (2016).

Quan, L. et al. BTLA marks a less cytotoxic T-cell subset in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with high expression of checkpoints. Exp. Hematol. 60, 47–56.e41 (2018).

Maffei, R. et al. The dynamic functions of IRF4 in B cell malignancies. Clin. Exp. Med. 23, 1171–1180 (2023).

Yan, J. et al. Identification and validation of a prognostic prediction model in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 846357 (2022).

Li, C., Teruya, B., Bhavana, D. & Althof, P. Large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement involving lung. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 154, S152–S153 (2020).

Pappu, R. et al. Requirement for B cell linker protein (BLNK) in B cell development. Science 286, 1949–1954 (1999).

Filosto, S. et al. Product attributes of CAR T-cell therapy differentially associate with efficacy and toxicity in second-line large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-7). Blood Cancer Discov. 5, 21–33 (2024).

Locke, F. L. et al. Tumor burden, inflammation, and product attributes determine outcomes of axicabtagene ciloleucel in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 4, 4898–4911 (2020).

Singh, V., Gupta, D. & Almasan, A. Development of novel anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies and modulation in CD20 levels on cell surface: looking to improve immunotherapy response. J. Cancer Sci. Ther. 7, 347–358 (2015).

Larson, S. M. et al. CD19/CD20 bispecific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) in naive/memory T cells for the treatment of relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Discov. 13, 580–597 (2023).

Shah, N. N. et al. Bispecific anti-CD20, anti-CD19 CAR T cells for relapsed B cell malignancies: a phase 1 dose escalation and expansion trial. Nat. Med. 26, 1569–1575 (2020).

Locke, F. L. et al. Long-term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1–2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 20, 31–42 (2019).

Topp, M. S. et al. Earlier corticosteroid use for adverse event management in patients receiving axicabtagene ciloleucel for large B-cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 195, 388–398 (2021).

Oluwole, O. O. et al. Prophylactic corticosteroid use in patients receiving axicabtagene ciloleucel for large B-cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 194, 690–700 (2021).

Frank, M. J. et al. Monitoring of circulating tumor DNA improves early relapse detection after axicabtagene ciloleucel infusion in large B-cell lymphoma: results of a prospective multi-institutional trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 3034–3043 (2021).

Miles, B. et al. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) by clonoSEQ to monitor residual disease after axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) in large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL). J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 7547 (2023).

Kurtz, D. M. et al. Enhanced detection of minimal residual disease by targeted sequencing of phased variants in circulating tumor DNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 1537–1547 (2021).

Lo Nigro, C. et al. NK-mediated antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity in solid tumors: biological evidence and clinical perspectives. Ann. Transl. Med. 7, 105 (2019).

Lam, N. et al. Development of a bicistronic anti-CD19/CD20 CAR construct including abrogation of unexpected nucleic acid sequence deletions. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 30, 132–149 (2023).

Roddie, C. et al. Dual targeting of CD19 and CD22 with bicistronic CAR-T cells in patients with relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 141, 2470–2482 (2023).

Tong, C. et al. Optimized tandem CD19/CD20 CAR-engineered T cells in refractory/relapsed B-cell lymphoma. Blood 136, 1632–1644 (2020).

Nastoupil, L. J. et al. KITE-363: A phase 1 study of an autologous anti-CD19/CD20 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) B-cell lymphoma (BCL). J. Clin. Oncol. 40, TPS7579 (2022).

Cheson, B. D. et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 3059–3068 (2014).

Locke, F. L. et al. Phase 1 results of ZUMA-1: a multicenter study of KTE-C19 anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy in refractory aggressive lymphoma. Mol. Ther. 25, 285–295 (2017).

Kochenderfer, J. N. et al. Lymphoma remissions caused by anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells are associated with high serum interleukin-15 levels. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 1803–1813 (2017).

Wang, M. et al. KTE-X19 CAR T-cell therapy in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1331–1342 (2020).

Kite, a Gilead Company. Tumor transcriptomic profiling of tissue biopsies from patients in ZUMA-14. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16809020 (2025).

Lee, D. W. et al. ASTCT consensus grading for cytokine release syndrome and neurologic toxicity associated with immune effector cells. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 25, 625–638 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants who participated in this trial and their families, caregivers and friends, along with the trial investigators, coordinators and healthcare staff at each study site. We would like to acknowledge the following individuals from Kite: L. Huang for support during the revision process, including assistance with public data deposition, S. Filosto and S. Poddar for their contributions to bioinformatic analysis of bulk RNA-seq data, T. Huang, S. Bala and S. Chen for their contributions to FFPE sample processing and next-generation sequencing and J. Budka for performing product phenotype analysis. This study was funded by Kite, which participated in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation and writing of the report. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship. Medical writing support was provided by V. Nguyen of Avalere Health for initial manuscript development and A. Skorusa of Nexus Global Group Science for manuscript revision and reviewer response preparation; all writing support was funded by Kite. P.Strati is supported by the Leukemia Lymphoma Society Scholar in Clinical Research Career Development Program, the Sabin Fellowship Award and the Gilead/Kite Scholar in Clinical Research Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.Strati, R.S., F.N., H.X. and K.P. conceptualized the trial. P.Strati, L.L., P.Shiraz, L.E.B, O.O.O., M.U., A.R., R.S., H.X. and K.P. conducted the investigation. J.S., F.M., J.K., R.S. and T.Z. curated the data. T.Z., J.S., F.M., J.K., R.S. and H.X. analyzed and interpreted the data. F.N. and H.X. supervised the trial. All authors contributed to the writing, review and editing of the paper and provided final approval of this publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

P.Strati reports consultancy for Kite, Roche-Genentech, Hutchison MediPharma, ADC Therapeutics, Incyte Morphosis and TG Therapeutics and research funding from Sobi Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca-Acerta, ALX Oncology and ADC Therapeutics. L.L. reports consultancy for and travel support from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Merck, TG Therapeutics, Janssen, Epizyme, Kite, Celgene, Pharmacyclics, Bristol Myers Squibb, ADC Therapeutics, BeiGene and Seattle Genetics, speakers’ bureau participation for and travel support from Kite, BeiGene, Pharmacyclics, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Seattle Genetics, TG Therapeutics, Epizyme, Karyopharm, Celgene and Bristol Myers Squibb and participation on the data safety advisory board for TG Therapeutics, AbbVie, Pharmacyclics, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Seattle Genetics and ADC Therapeutics. P.Shiraz reports research funding from Kite and Orca Bio. L.E.B. reports honoraria from Kite, a consultancy or advisory role for Kite, Gilead and Roche, speakers’ bureau participation for Kite and AstraZeneca and research funding from MustangBio, Merck, Amgen and AstraZeneca. O.O.O. reports a consultancy or advisory role for Kite, Janssen, Pfizer, Novartis and Curio Science and honoraria and research funding from Kite. M.U. reports advisory board participation for Gilead and Stemline. A.R. reports honoraria from Cigna, Amgen and Takeda, a consultancy or advisory role for Amgen, AstraZeneca, GenMab, Novartis and Takeda and speakers’ bureau participation for Takeda. T.Z. and J.S. report employment with Kite. F.M. reports employment with and research funding from Kite and Gilead and stock or other ownership in Gilead. J.K. and H.X. report employment with Kite and stock or other ownership in Gilead. R.S. reports employment and leadership role with Kite and Atara, stock or other ownership in Gilead and Atara and patents, royalties and other intellectual property from Kite. F.N. reports prior employment with Kite and stock or other ownership in Gilead. K.P. reports consultancy for AbbVie, Adaptive Biotechnologies, ADC Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Caribou Biosciences, Fate Therapeutics, Genentech/Roche, Janssen/Pharmacyclics, Kite, Lilly/Loxo Oncology, Merck, MorphoSys, Sana Pharma and Xencor, research funding (to institution) from AbbVie, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Adicet Bio, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Caribou Biosciences, Century Therapeutics, CRISPR Therapeutics, Cargo Therapeutics, Fate Therapeutics, Genentech/Roche, Janssen/Pharmacyclics, Kite, Lilly/Loxo Oncology, Merck, Nurix, Sana Pharma and Xencor and speakers’ bureau participation for AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb and Kite.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cancer thanks Julio Delgado, Motomi Mori and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Swimmer plot of responses and survival status over time.

Safety analysis population (all patients treated with axi-cel). Objective responses were assessed by the investigator per Lugano Classification. Axi-cel, axicabtagene ciloleucel; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CR, complete response; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Laboratory results over time.

(A) Absolute neutrophil, lymphocyte, leukocyte, and platelet counts and (B) hemoglobin levels. The number of evaluable patients at each analysis visit is provided below the x-axis. Data are presented as median values; whiskers indicate Q1 and Q3. Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Peak CAR T-cell levels by response.

Peak CAR T-cell levels normalized to baseline tumor burden (SPD) by (A) best overall response and (B) ongoing response. Associations of CAR T-cell levels with response were analyzed in the mITT population (N = 26). One patient with ongoing response was lost to follow-up at the time of data cutoff and was excluded (from panel B). CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CR, complete response; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; SPD, sum product of diameters.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Analysis of rituximab levels and number of doses, including correlations with response.

Correlation between rituximab levels in blood and number of rituximab doses (A). Number of rituximab doses taken by patients by best response (B) and ongoing response (C). Peak rituximab levels in blood by (D) best response and (E) ongoing response. Peak rituximab levels were defined as the maximum rituximab level measured after axi-cel infusion. Responses were assessed in the mITT population (N = 26) and by the investigator per Lugano Classification. One patient with ongoing response was lost to follow-up at the time of data cutoff and was excluded (from panels C and E). For panels (D) and (E), box plots show Q1, median, and Q3, and the lower and upper whiskers show the minimum and maximum values excluding outliers, respectively. Axi-cel, axicabtagene ciloleucel; AUC, area under the curve; CR, complete response; mITT, modified intention-to-treat; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile; SD, stable disease.

Extended Data Fig. 5 MRD status.

(A) Swimmer plot of MRD status (assessed in all patients with available samples, n = 20/26) and objective responses over time. (B) ROC curves for ongoing response and MRD status at Day 28, Month 3, and Month 5. ROC curves of true-positive (sensitivity) versus false-positive (specificity) rates depict MRD predictive value at Day 28, Month 3, and Month 5 in the safety analysis population (N = 26). AUC, area under the curve; axi-cel, axicabtagene ciloleucel; CR, complete response; MRD, minimal residual disease; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; SD, stable disease.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Heatmap depicts enrichment scores of gene sets as defined in the Nanostring immune-exhaustion panel.

Transcriptomic analysis of baseline tumor biopsies was performed in 13 patients, of whom 5 had ongoing response (CR, n = 5), 6 relapsed (CR, n = 5), and 2 were non-responders at the data cutoff date. AKT, protein kinase B; AP-1, activator protein 1; BCR, B cell receptor signaling; CR, complete response; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4; DAP12, DNAX-activating protein of 12 kDa; GSVA, gene set variation analysis score; IL, interleukin; JAK, Janus kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NF-kB, nuclear factor kappa B; NK, natural killer; PD, progressive disease; PD1, programmed cell death protein 1; PI3K, phosphoinositide-3 kinase; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; PR, partial response; RAR, retinoic acid receptor; SD, stable disease; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TCR, T cell receptor; TGF, transforming growth factor; TLR, toll-like receptor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Redacted ZUMA-14 clinical trial protocol.

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables 1–6.

Source data

Source Data Figs. 2–6 and Extended Data Figs. 1–6

Source data for Figs. 2–6 and Extended Data Figs. 1–6.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Strati, P., Leslie, L., Shiraz, P. et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel in combination with rituximab for refractory large B cell lymphoma: the phase 2, single-arm ZUMA-14 trial. Nat Cancer (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-025-01102-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-025-01102-1