Abstract

Non-magnetic materials exhibiting large spin-Hall effect (SHE) are eagerly desired for high-performance spintronic devices. Here, we report that non-equilibrium Cu-Ir binary alloys with compositions beyond the solubility limit are candidates as spin-Hall materials, even though Cu and Ir do not exhibit remarkable SHE themselves. Thanks to non-equilibrium thin film fabrication, the Cu-Ir binary alloys are obtained over a wide composition range even though they are thermodynamically unstable in bulk form. We investigate the SHE of Cu-Ir by exploiting a combinatorial technique based on spin Peltier imaging, and find that the optimum Ir concentration for enhancing SHE is around 25 at.%. We achieve a large spin-Hall angle of 6.29 ± 0.19% for Cu76Ir24. In contrast to Cu-Ir, non-equilibrium Cu-Bi binary alloys do not show remarkable SHE. Our discovery opens a new direction for the exploration of spin-Hall materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Generation and detection of spin current (Js), which is the flow of spin angular momentum, are the keys for spintronics. In order to improve the device performance, highly efficient conversion between charge current (Jc) and Js is indispensable. A way for the conversion from Jc to Js is to exploit the spin-Hall effect (SHE)1,2,3,4,5, which is expressed as

where jc and js are charge current density and spin current density, respectively, αSH is the spin-Hall (SH) angle, e (<0) is the electric charge of an electron, \(\hbar\) is the reduced Planck constant, and s is the quantization axis of electron spin. When Jc flows in a nonmagnet with large spin–orbit interaction, up-spin and down-spin electrons are scattered in opposite directions. This results in a Js flow without a net charge current flow in the transverse direction to Jc. Equation (1) means that αSH corresponds to the conversion efficiency, and a nonmagnet showing large αSH is a building block of contemporary spintronics.

Many recent studies have been devoted to the materials development to get larger αSH, and found a variety of SH materials, which are not only limited to nonmagnetic metals5 but also include topological insulators6,7, and ferromagnets8,9,10,11,12,13. Among them, heavy metals such as Pt14,15,16, Ta17,18, and W19 are representatives of SH materials at present because those simple heavy metals have potential to be incorporated into the existing spintronic device architecture. Apart from the usage of elemental nonmagnetic metals, element doping and alloying are also effective ways to develop SH materials, e.g. Cu–Ir20,21,22,23,24, Cu–Bi25, Cu–Pt26,27,28, Au–Pt29,30, and Au–W31. Cu–Ir system is an interesting SH material because neither Cu nor Ir exhibits remarkable SHE32. Niimi and co-workers20 investigated the SHE of Ir-doped Cu with the Ir concentration range between 1% and 12%, which exhibited the large αSH of ~2.1%. They mentioned that the predominant mechanism of SHE for the Ir-doped Cu was skew scattering. It was also reported that the Cu doped with a very small amount of Bi (<0.5%) also shows even larger SHE25. These Cu-based SH materials are also advantageous from the viewpoint of practical applications because of its compatibility to the standard integrated circuit interconnection technology21. In spite of the attracting features of Cu-based binary alloys, the comprehensive study on SHE for them is very limited. This limitation for the Cu–Ir might be because the solubility limits are narrow at both Cu-rich and Ir-rich sides, which are <10%, in the Cu–Ir binary phase diagram33. Although Cramer et al.23 recently reported the investigation of SHE for the Cu–Ir alloys in a wide composition range, the magnitude and the mechanism of SHE, and the detailed structures have not been understood for the non-equilibrium Cu–Ir alloys beyond the solubility limit.

In this paper, we report a comprehensive study on the SHE of Cu–Ir binary alloys by combining “high-throughput screening based on thermal imaging for composition-spread films” and “accurate evaluation using harmonic Hall voltage measurement”. We utilize the spin Peltier effect (SPE)34,35, which is the phenomenon of a heat current generation in linear response to Js injection in a magnetic insulator/SH material junction, as a probe of the spin-charge current conversion in the SH material layer since the magnitude and the sign of temperature modulation due to the SPE (ΔTSPE) are determined by the spin-charge current conversion. The active infrared emission microscopy called the lock-in thermography (LIT)35,36,37,38,39,40,41 allows us to visualize ΔTSPE, and to reveal the spatial distribution of ΔTSPE in the composition-spread films. We show the magnitude of SHE is maximized at the non-equilibrium phase that is not thermodynamically stable in the bulk phase diagram. After the high-throughput screening of SH material, the αSH value at the optimum composition is evaluated. In addition to the Cu–Ir, the non-equilibrium Cu–Bi binary alloys are also prepared and their SHE is examined for comparison.

Results

Structure of Cu–Ir composition-spread film

The Cu–Ir composition-spread films were prepared on a ferrimagnetic yttrium–iron garnet (YIG) substrate with the size of 10 mm × 10 mm by the combinatorial sputtering system (CMS-3200, Comet, Inc.). A schematic illustration of the film sample is displayed in Fig. 1a. The wedge-shaped Cu and Ir layers were alternately deposited using the linear moving shutter and the rotating substrate holder. After depositing one wedge-shaped layer the substrate was rotated by 180°, and the next wedge-shaped layer was deposited. The thickest part in each layer was designed to be 0.5 nm. In other word, one Cu/Ir pair has the thickness of 0.5 nm, where the Cu and Ir layers were naturally mixed without any heating process. Finally, we obtained the composition-spread films having the Ir concentration (xIr) range from 0 at.% (pure Cu) to 100 at.% (pure Ir). By repeating the deposition of 0.5 nm-thick Cu/Ir pair 20 times, 40 times, and 60 times, the samples with the total thicknesses (t) of 10, 20, and 30 nm, respectively, were obtained. An important point here is that all the layers were deposited at room temperature in order to prevent from the appearance of thermodynamically stable phase. In the blanket film sample used for structural characterization, the gradient of composition was formed in the length of 8.0 mm, which is laterally sandwiched with the pure Cu and Ir regions, i.e. 0.6 mm for the pure Cu, 8.0 mm for the composition-spread region, and 0.6 mm for the pure Ir. The position in the blanket film (yF) was defined as shown in Fig. 1a.

a Schematic illustration of the blanket film sample used for the structural characterization, where the wedge-shaped Cu and Ir layers were alternatively deposited using the linear moving shutter on the yttrium–iron-garnet (YIG) substrate. yF is the position in the blanket film. b yF dependence of xIr for the Cu–Ir composition-spread film with the thickness (t) of 30 nm measured by electron probe x-ray microanalysis. c X-ray diffraction profiles for t = 30 nm measured at different yF. The profiles are vertically shifted for clarity. d Lattice constant a obtained from the Cu–Ir 111 reflection as a function of yF. The inset shows a versus xIr. e (left) Cross-sectional high-resolution transmission electron microscope image, where the length of write scale bar is 25 nm, (center) element analyses of Cu and (right) Ir by the energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscopy for the film sample with t = 30 nm at yF = 3 mm.

Figure 1b shows the yF dependence of Ir concentration (xIr) for the Cu–Ir composition-spread film with t = 30 nm measured by electron probe x-ray microanalysis (EPMA). It is confirmed that xIr is varied with the position. Although in the Cu-rich region (yF ≤ 4 mm) xIr almost linearly increases with yF, the position dependence deviates from the tendency in the Ir-rich region (yF ≥ 5 mm). At present, we have no clear explanation for this rapid increase of xIr at the Ir-rich region. The x-ray diffraction (XRD) profiles for t = 30 nm measured at different yF are shown in Fig. 1c, where the observed peaks come from the Cu–Ir 111 reflections. It is noted that the XRD peak angle continuously shifts as yF is varied, i.e. xIr is increased. In addition, no remarkable peak splitting is observed at all the positions. These facts suggest that the lattice constant of single-phase alloys is continuously varied. In other words, the Cu–Ir solid solutions are formed at the overall compositions, and the non-equilibrium phase appears at the compositions that are out of the solubility limit of the bulk phase diagram. Figure 1d displays the yF dependence of the lattice constant a. The yF dependence of a shows the continuous change, and the plot of a versus xIr in the inset of Fig. 1d suggests the linear relationship between a and xIr, meaning that the Vegard’s law42 is satisfied. Figure 1e shows the cross-sectional high-resolution transmission electron microscope image for t = 30 nm together with the element analysis of Cu and Ir by the energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscopy for the film samples at yF = 3 mm. From the element mappings, the Cu and Ir atoms are uniformly distributed. Therefore, one sees that neither segregation nor phase separation exists remarkably.

Thermal imaging of SPE

In order to evaluate the SHE of Cu–Ir composition-spread films, we carried out the SPE measurement using the LIT. As reported previously41, this LIT-based SPE measurement enables us to do systematic and high-throughput screening of SH materials. SPE is the phenomenon giving rise to the temperature modulation due to the interaction of Js and spontaneous magnetization (M). As depicted in Fig. 2a, for the present Cu–Ir/YIG junction, Js generated via the SHE of Cu–Ir interacts with M of YIG, which modulates the temperature of the Cu–Ir/YIG junction. According to the previous works on SPE34,35,39,40,41, the heat current (Jq) generated by SPE and the resultant ΔTSPE are proportional to αSH. Therefore, by measuring the ΔTSPE, one can obtain information on the magnitude and sign of the SHE of Cu–Ir.

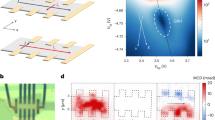

a Concept of the spin-Hall effect (SHE)-induced spin Peltier effect (SPE). For the present Cu–Ir/YIG junction, the SHE in Cu–Ir converts the charge current (Jc) into the spin current (Js). The Js interacts with magnetization (M) of YIG, which results in the heat current (Jq) flow across the Cu–Ir/YIG junction. b Illustration of device for the SPE measurement, which consists of two wires with the width of 0.4 mm. The position in the device was denoted by yD. c Lock-in thermography (LIT) conditions for the SPE and d Joule heating measurements. e Amplitude (ASPE) and phase (ϕSPE) images of SPE-induced temperature modulation for t = 30 nm at Jc = 10 mA with the lock-in frequency (f) of 25 Hz. These images were obtained by using the images at the external magnetic field (Bext) of 0.1 and −0.1 T, where Bext was applied along the in-plane x direction, in order to exact the Bext-odd component. f Amplitude (AJoule) and phase (ϕJoule) images of Joule-heating-induced temperature modulation for t = 30 nm at Jc0 = 1 mA and ΔJc = 1 mA with f = 25 Hz. Bext was not applied. g ASPE and h AJoule as a function of yD in the left Cu–Ir wire with t = 30 nm at f = 25 Hz. These line profiles were obtained by averaging the data points in the 0.2 mm-wide central region of the wire. i Resistivity (ρ) of Cu–Ir wire with t = 30 nm as a function of yD.

The device for the SPE measurement is schematically illustrated in Fig. 2b. The composition-spread film was patterned into the device consisting of two wires with the width of 0.4 mm. One ends of the wires were electrically connected, such that the two wires were connected in series with Jc flowing along opposite directions. In the device for the SPE measurement, the gradient of composition was formed along the length of 8.0 mm as shown in Fig. 2b, and the position in the device was denoted by yD. The infrared radiation thermally emitted from the sample surface was detected while applying an ac Jc with rectangular wave modulation to the Cu–Ir wires. The LIT conditions for the SPE and Joule heating measurements are shown in Fig. 2c, d, respectively. The SPE signal was separated from the Joule heating contribution when the first harmonic response of the thermal images was fed without any dc current offset. For the measurement of Joule heating, on the other hand, the ac Jc together with a dc offset of Jc0 was applied to the Cu–Ir wires. Although both the SPE and Joule-heating contributions are included in the first harmonic response, the observed signals mainly come from the Joule-heating-induced temperature modulation (ΔTJoule) because ΔTJoule is much larger than ΔTSPE.

First, let us explain the SPE contribution in the Cu–Ir wires with t = 30 nm. Figure 2e shows the amplitude (ASPE) and phase (ϕSPE) images of SPE-induced temperature modulation at Jc = 10 mA with the lock-in frequency (f) of 25 Hz. These images were obtained by using the images at the external magnetic field (Bext) of 0.1 and −0.1 T, where Bext was applied along the in-plane x direction, in order to extract the Bext-odd component. The detailed procedure was reported in ref. 41, which is effective to subtract the B-independent background signals coming from the conventional Peltier effect because the Peltier coefficient of the composition-spread film varies from one position to another. The left and right Cu–Ir wires exhibit the opposite phase. Namely, the sign of the temperature modulation is reversed by reversing Jc. This fact coincides with the symmetry of SPE. The SPE-induced temperature modulation appears only within the wires and the thermal diffusion is suppressed. This is attributable to the dipolar heat sources placed near the sample surface by the SPE35,39,43. Figure 2g shows ASPE as a function of yD in the left Cu–Ir wire with t = 30 nm. ASPE shows the maximum at yD ~ 1.9 mm.

Next, the Joule-heating contribution is examined. Figure 2f shows the amplitude (AJoule) and phase (ϕJoule) images of Joule-heating-induced temperature modulation at Jc0 = 1 mA and ΔJc = 1 mA with f = 25 Hz. These images were observed without Bext. Since AJoule is increased and no sign change of ϕJoule is observed for the left and right wires, Joule heating increases the temperature of the Cu–Ir wires irrespective of the Jc direction, which is totally different from the SPE-induced temperature modulation. Similar to the SPE-induced temperature modulation, the spatial variation of AJoule outside the wires is suppressed owing to the high f. Therefore, the magnitude of AJoule provides us the information of local electric conductivity. Figure 2h plots AJoule as a function of yD in the left Cu–Ir wire with t = 30 nm. AJoule shows the maximum at yD ~ 2.1 mm, implying the increase in the resistivity (ρ) of Cu–Ir wire at yD ~ 2.1 mm. We also evaluated ρ directly using the conventional transport measurement, which is plotted in Fig. 2i. Consequently, Fig. 2h, i revealed the position-dependent ρ values along the y direction of wire. It is noted that yD ~ 2.1 mm exhibiting the maximum AJoule is the different position from yD ~ 1.9 mm for the maximum of ASPE.

Spin-Hall effect probed by SPE

The yD dependence of ASPE allows us to qualitatively discuss the Ir concentration dependence of αSH and SH conductivity (σSH) by assuming that the spin mixing conductance at the Cu–Ir/YIG interface and the spin diffusion length in the Cu–Ir do not show a remarkable position dependence. ΔTSPE/jc and ΔTSPE/E are proportional to αSH and σSH (=αSHσCu–Ir), respectively, where E is the electric field and σCu–Ir is the conductivity of Cu–Ir. ΔTSPE is given by the real part of the complex temperature modulation output by the LIT: ΔTSPE = ASPE cos(ϕSPE), because the phase delay due to thermal diffusion in the SPE signal is negligibly small35,39.

Figure 3a, b show the ΔTSPE/jc and ΔTSPE/E as a function of xIr for t = 10, 20, and 30 nm, where xIr was estimated using the position dependence of xIr shown in Fig. 1b. ΔTSPE/jc exhibits the maximum value around xIr = 25 at.% while ΔTSPE/E is monotonically decreased as xIr is increased. These results suggest that αSH is enhanced around xIr = 25 at.%. Figure 3c is the plot of t dependence of ΔTSPE/jc for several Ir concentrations. t = 20 nm shows a larger ΔTSPE/jc than those for t = 10 and 30 nm. We have no clear reason for this t dependence at present.

In order to elucidate the mechanism of the enhanced αSH when xIr is increased up to 25 at.%, ΔTSPE/E versus σCu–Ir is summarized in Fig. 3d, where the data in the Ir concentration range from 0 to 25 at.% (hatched areas in Fig. 3a, b) were plotted for t = 10, 20, and 30 nm. This plot corresponds to σSH versus σCu–Ir. One can see that σSH remains to be almost constant regardless of σCu–Ir. This tendency implies that either the side jump process or the intrinsic mechanism due to the Berry curvature is a dominant mechanism for the SHE in the Cu–Ir. The details will be discussed later. An important finding is the enhanced αSH around xIr = 25 at.% that is definitely out of the solubility limit in the Cu-rich region of bulk phase diagram33.

Quantitative analysis of spin-Hall angle

Here we evaluate the SH efficiency for the Cu76Ir24 alloy, which is in the composition range showing the enhanced αSH, using the harmonic Hall voltage measurement44,45,46,47,48. For this quantitative measurement, we prepared a thin film consisting of Cu76Ir24 (t nm)|CoFeB (2 nm)|Al (2 nm) on the sapphire c-plane substrate, where the Cu76Ir24 is a wedge-shaped layer with t in the range from 1 to 19 nm, and the CoFeB is in-plane magnetized. The thin film was patterned into the Hall bar shape as illustrated in Fig. 4a. The in-phase first harmonic (Vω) and the out-of-phase second harmonic voltages (V2ω) were detected using two lock-in amplifiers under the application of ac current with the frequency of ω/2π = 172.1 Hz, allowing us to separately determine two kinds of torques acting on the CoFeB magnetic moment (m). In general, SHE gives rise to the damping-like (DL) torque pointing along m × (m × s) with a magnitude of BDL. Another torque mainly coming from the Rashba–Edelstein effect (REE) is called the field-like (FL) torque directed along m × s with a magnitude of BFL. By considering the dependence of Vω and V2ω on the in-plane field angle (θ, depicted in Fig. 4a), the following expressions of Rω and R2ω for the Hall resistance are obtained47,48:

where RPHE and RAHE are the resistance changes originating from the planar Hall effect (PHE) and the anomalous Hall effect (AHE), respectively. BOe and Bani are the Oersted field due to the current flow and the anisotropy field, respectively. \(R_{\nabla T}^0\) denotes the second harmonic Hall signal due to thermoelectric effects including the anomalous Nernst effect and spin Seebeck effect. Using the coefficients of C and D, Eq. (3) can be rewritten as

a Schematic illustration of Hall bar-shaped device together with the setup of harmonic Hall voltage measurement, where the stacking structure of thin film is Cu76Ir24 (t nm)|CoFeB (2 nm)|Al (2 nm) on the sapphire c-plane substrate. The in-plane field angle (θ) was rotated. b θ dependence of Rω and c R2ω for t = 5.8 nm with Bext = 0.1 T at 300 K. In b, the red open circles denote the measured data, and the black solid curve represents the result of fitting. In c, the orange open circles denote the measured data, and the blue curve is the result of fitting by cosθ. The green open circles represent the values subtracting the cosθ component from the measured data, and the black curve is the result of fitting by the cos2θ cosθ function. d Anomalous Hall loop with Bext applied normal to the device plane for t = 5.8 nm. e Coefficients C and f D of second harmonic Hall resistance (R2ω) as a function of the inverse of Bext + Bani and the inverse of Bext, respectively for t = 5.8 nm, where Bani is the anisotropy field. The solid lines are the results of fitting. g t dependence of the resistivity (ρ) of the Cu76Ir24. h Damping-like torque efficiency per unit applied electric field (\(\xi _{{\mathrm{DL}}}^{\mathrm{{E}}}\)) as a function of t, where the solid line is the result of fitting by Eq. (5). The error bars come from the standard deviation obtained by the linear fit in e.

Therefore, the measurement of in-plane field angular dependence enables us to separate the DL (mainly of SHE origin) contribution with thermoelectric effects and the FL (mainly of REE origin) contribution. Furthermore, DL contribution and the thermoelectric effects can be separated by investigating the Bext dependence.

Figure 4b, c show the θ dependence of Rω and R2ω, respectively, for t = 5.8 nm with Bext = 0.1 T at 300 K. From the θ dependence of Rω (Fig. 4b), we obtained RPHE = −0.09 mΩ. In Fig. 4c, the orange open circles denote the measured data, and the blue curve is the result of fitting by cosθ. The green open circles represent the values subtracting the cosθ component from the measured data, and the black curve is the result of fitting by the cos 2θ cosθ function. As seen in Fig. 4c, the θ dependence of R2ω is fitted by Eq. (4). We also measured the AHE with Bext applied normal to the device plane (Fig. 4d), and RAHE = 1.74 Ω and Bani = 0.9 T were obtained. The coefficient C (D) as a function of the inverse of Bext + Bani (the inverse of Bext) is plotted in Fig. 4e (Fig. 4f), where the large Bext was applied to do the correct estimation of the thermo-electric contribution. From the linear fits, BDL and BFL are evaluated to be 0.74 and 0.33 mT, respectively. According to the previous papers47,48, the DL torque efficiency (ξDL) and the FL torque efficiency (ξFL) are given by \({\xi}_{{\mathrm{DL}}} = \frac{{2e}}{\hbar }\frac{{B_{{\mathrm{DL}}}M_{\mathrm{{s}}}t_{{\mathrm{CFB}}}}}{{j_{{\mathrm{Cu}} - {\mathrm{Ir}}}}}\) and \({\xi}_{{\mathrm{FL}}} = \frac{{2e}}{\hbar }\frac{{B_{{\mathrm{FL}}}M_{\mathrm{{s}}}t_{{\mathrm{CFB}}}}}{{j_{{\mathrm{Cu}} - {\mathrm{Ir}}}}}\), where Ms is the saturation magnetization of CoFeB, which was experimentally obtained to be 800 kA m−1, tCFB is the CoFeB layer thickness, and jCu–Ir is the current density flowing in the Cu–Ir layer. With the parameters of Ms = 800 kA m−1 and jCu–Ir = 8.1 × 106 A cm−2, ξDL = 4.5% and ξFL = 2.0% were obtained for t = 5.8 nm. The accuracy in the estimation of ξFL should be noted here. The small cos2θ cosθ dependence in R2ω, which is attributed to the small RPHE, gives rise to the low accuracy for the estimation of ξFL. Also, one is aware of the apparent parabolic 1/Bext dependence of coefficient D in Fig. 4f. This is attributable to the unwanted cross talk between C and D in the fitting and a small imperfection in C, which is probably due to the slight misalignment or the experimental uncertainty, leads to a large relative error in D. This is another source of the low accuracy for the estimation of ξFL. In contrast to ξFL, the estimation of ξDL is not affected by the magnitude of RPHE. Hereafter, we will focus on the DL torque component, and evaluate αSH for the Cu76Ir24 from ξDL.

According to ref. 49, with the assumption that the interface spin transparency is <1 and the spin backflow is dominant at the well-ordered interface, the t dependence of ξDL per unit applied electric field, \(\xi _{{\mathrm{DL}}}^{\mathrm{{E}}} = {\xi}_{{\mathrm{DL}}}/\rho\), is expressed as

where λSD is the spin diffusion length of Cu76Ir24 and Re[GMIX] is the real part of the spin mixing conductance. Using the t dependence of ρ (Fig. 4g), \(\xi _{{\mathrm{DL}}}^{\mathrm{{E}}}\) is plotted as a function of t in Fig. 4h. From the fit to the data with Eq. (5) and the parameters of ρ = 261 μΩ cm and Re[GMIX] = 1 × 1015 Ω−1 m−2, σSH and λSD of the Cu76Ir24 were estimated to be (2.41 ± 0.07) × 104 [\(\hbar\)/2e] Ω−1 m−1 and 0.83 ± 0.14 nm, respectively. Finally, we obtained αSH = 6.29 ± 0.19% using the harmonic Hall voltages. In addition to the harmonic Hall voltage measurement, we carried out the spin-Hall magnetoresistance measurement (see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1), and estimated αSH = 6.95 ± 0.05% and λSD = 1.67 ± 0.04 nm. These values are close to the values obtained by the harmonic Hall voltage measurement. Then, we conclude that the Cu76Ir24 exhibits large αSH > 6%.

Since Bi-doped Cu is believed to be a good SH material25, we performed the same LIT-based SPE measurements using a Cu–Bi composition-spread film on the YIG substrate. In contrast to the Cu–Ir, the non-equilibrium Cu–Bi binary alloys do not show remarkable SHE (see Supplementary Fig. 2). According to ref. 25, doping a very small amount of Bi is effective to obtain the large SHE. On the other hand, this study examined the effect of alloying on SHE for the Cu–Bi over a wide composition range, and do not examine on the Cu-rich region with a very small amount of Bi. This is a possible reason why the present Cu–Bi does not exhibit the definite SHE. As a result, we found that the alloying is not effective for the Cu–Bi binary alloys.

Discussion

This work has three major achievements: (i) development of non-equilibrium Cu–Ir binary alloys beyond the solubility limit by the sputtering method, (ii) finding that the non-equilibrium Cu–Ir exhibits the large SHE although neither Cu nor Ir exhibits remarkable SHE, and (iii) elucidation of mechanism of SHE for the non-equilibrium Cu–Ir. Our comprehensive investigation revealed that the value of αSH shows the maximum around xIr = 25 at.%, which is much larger than the solubility limit. Even at such a non-equilibrium composition, we successfully obtained the single-phase Cu–Ir binary alloy. αSH > 6% obtained for Cu76Ir24 is comparable to or larger than that for Pt5.

Finally, we complement the mechanism of SHE for the non-equilibrium Cu–Ir binary alloy. As shown in Fig. 3d, the plot of ΔTSPE/E versus σCu–Ir suggests that σSH keeps almost constant regardless of σCu–Ir. This indicates that either the side jump process or the intrinsic mechanism due to the Berry curvature is a dominant mechanism for the SHE in the Cu–Ir. It is worth noting that the previous work for the Ir-doped Cu reported that the skew scattering plays the dominant role for the SHE in the Ir-doped Cu with xIr < 12 at.%20. Therefore, the present non-equilibrium Cu–Ir binary alloy exhibits the SHE totally different from the Ir-doped Cu quantitatively and qualitatively. Our discovery suggests that a non-equilibrium alloy consisting of nonmagnets with negligible SHE has a potential as an SH material, and opens a new direction for the exploration of SH materials.

Methods

Fabrication of composition-spread Cu–Ir (Cu–Bi) film

The Cu–Ir (Cu–Bi) composition-spread films were fabricated on a YIG substrate at ambient temperature using DC magnetron sputtering with a base pressure of <6.0 × 10−6 Pa and a process Ar gas pressure of 0.4 Pa. The YIG substrate consists of a 23-μm-thick single-crystalline YIG (111) film uniformly grown on a single-crystalline Gd3Ga5O12 (111) substrate by means of a liquid phase epitaxy method. To improve the lattice matching between YIG and Gd3Ga5O12, a tiny amount of Y in YIG is substituted by Bi. The substrate was cut into a 10 × 10 mm2 square shape. As described in the main text, the Cu–Ir composition-spread films were prepared by repeating the following three processes: (1) deposition of a wedge-shaped Cu layer using the linear moving shutter, (2) rotation of the substrate by 180°, and (3) deposition of a wedge-shaped Ir layer using the linear moving shutter, where the total thickness of a Cu/Ir pair was designed to be 0.5 nm. The deposition of 0.5 nm-thick Cu/Ir pair was repeated 20 times, 40 times, and 60 times for the samples with total thicknesses of 10, 20, and 30 nm, respectively. All the layers were deposited at room temperature in order to prevent from the appearance of thermodynamically stable phase. The same deposition procedure was used for the Cu–Bi composition-spread films. The Cu (Ir) layers were deposited at a rate of 0.052 nm s−1 (0.034 nm s−1). For the LIT measurement, the composition-spread film was patterned into a rectangular shape with a size of 8.0 mm × 0.4 mm by sputtering the layers through a metallic shadow mask, where the composition gradient is along the 8 mm direction. All the films were capped with a 2-nm-thick Al film to prevent oxidation.

In addition to the composition-spread films, for the harmonic Hall voltage measurement, we prepared the thin film consisting of Cu76Ir24 (t nm)|CoFeB (2 nm)|Al (2 nm) on the sapphire c-plane substrate. The thickness of wedge-shaped Cu76Ir24 layer was continuously varied from 1 to 19 nm in the lateral length of 20 mm, where the Cu76Ir24 layer was formed by co-sputtering of Cu and Ir. We experimentally confirmed that the DL torque efficiencies were almost the same for the films prepared by alternate layer deposition method and the co-sputtering method, indicating that there is no difference in the properties between the composition-spread films and the films for the harmonic Hall voltage measurement. The composition of Cu76Ir24 was determined by the inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy. The thin film was patterned into the Hall bar shape through the use of photo lithography and Ar ion milling.

Structural characterization and magnetization measurement

For structural analysis of the composition-spread films, XRD was measured with a Rigaku SmartLab XRD diffractometer, using Cu-Kα1 radiation (λ = 0.15406 nm). The x-ray was incident on the sample in the Bragg–Brentano geometry as a parallel beam through a length limit slit of 0.5 mm in the direction perpendicular to the composition gradient and detected in a 2D detector (Rigaku PILATUS100K/R). The measurement was performed at different positions on the films along the composition gradient at an interval of 1 mm. The Ir (Bi) concentration of the Cu–Ir (Cu–Bi) composition-spread film was measured by EPMA (JEOL, JXA-8530F). The transmission electron microscope observation was carried out by using JEOL, JEM-ARM200F. The magnetic properties of the CoFeB layer were characterized using the vibrating sample magnetometer at room temperature.

LIT measurements

In the SPE and Joule-heating measurements based on the LIT, we applied a square-wave-modulated AC charge current (f = 25 Hz) with Jc to the Cu–Ir (Cu–Bi) layer and extracted thermal images oscillating with the same f. The first harmonic contribution of the obtained thermal images was transformed into the A and ϕ images through Fourier analysis. The A image shows the distribution of the magnitude of the temperature modulation generated by the SPE or Joule heating. The ϕ image shows the sign of the temperature modulation in the SPE measurements, while it gives the information about the time delay due to thermal diffusion in the Joule-heating measurements. In the SPE (Joule-heating) measurements, the DC offset of the square-wave-modulated AC charge current is zero (Jc/2). To enhance infrared emissivity, the surface of the samples was coated with insulating black ink with the high emissivity (>0.95), commercially available from Japan Sensor Corporation. The infrared radiation intensity detected by an infrared camera is converted into temperature information by the calibration method shown in ref. 50. All the LIT observations were carried out at room temperature and atmospheric pressure.

Harmonic Hall voltage measurement

The measurement was performed in a physical property measurement system (PPMS) equipped with horizontal rotator option. The device under test (a Hall bar) was wire-bonded on a standard holder designed for performing field scans within the azimuthal plane. A sinusoidal signal of amplitude 1 mA for the device with t = 2.2 nm and 5 mA for other devices and of frequency 13.7 Hz was applied using a Keithley 6221 DC and AC current source meter. The first and second harmonic Hall resistances were simultaneously measured by two NF LI5660 lock-in amplifiers.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Dyakonov, M. I. & Perel, V. I. Current-induced spin orientation of electrons in semiconductors. Phys. Lett. A 35, 459–460 (1971).

Hirsch, J. E. Spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 1834–1837 (1999).

Kato, Y. K., Myers, R. C., Gossard, A. C. & Awschalom, D. D. Observation of the spin Hall effect in semiconductors. Science 306, 1910–1913 (2004).

Wunderlich, J., Kaestner, B., Sinova, J. & Jungwirth, T. Experimental observation of the spin-Hall effect in a two-dimensional spin–orbit coupled semiconductor system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 047204 (2005).

Hoffman, A. Spin Hall effects in metals. IEEE Trans. Magn. 49, 5172–5192 (2013).

Mellnik, A. R. et al. Spin-transfer torque generated by a topological insulator. Nature 511, 449–451 (2014).

Fan, Y. et al. Magnetization switching through giant spin–orbit torque in a magnetically doped topological insulator heterostructure. Nat. Mater. 13, 699–704 (2014).

Miao, B. F., Huang, S. Y., Qu, D. & Chen, C. L. Inverse spin Hall effect in a ferromagnetic metal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 066602 (2013).

Wu, S. M., Hoffman, J., Pearson, J. E. & Bhattacharya, A. Unambiguous separation of the inverse spin Hall and anomalous Nernst effects within a ferromagnetic metal using the spin Seebeck effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 092409 (2014).

Seki, T. et al. Observation of inverse spin Hall effect in ferromagnetic FePt alloys using spin Seebeck effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 092401 (2015).

Gibbons, J. D., MacNeill, D., Buhrman, R. A. & Ralph, D. C. Reorientable spin direction for spin current produced by the anomalous Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Appl. 9, 064033 (2018).

Iihama, S. et al. Spin-transfer torque induced by the spin anomalous Hall effect. Nat. Electron. 1, 120–123 (2018).

Seki, T., Iihama, S., Taniguchi, T. & Takanashi, K. Large spin anomalous Hall effect in L10-FePt: symmetry and magnetization switching. Phys. Rev. B 100, 144427 (2019).

Saitoh, E., Ueda, M., Miyajima, H. & Tatara, G. Conversion of spin current into charge current at room temperature: inverse spin-Hall effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 182509 (2006).

Kimura, T., Otani, Y., Sato, T., Takahashi, S. & Maekawa, S. Room-temperature reversible spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 156601 (2007).

Liu, L., Moriyama, T., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance induced by the spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 36601 (2011).

Liu, L. et al. Spin-torque switching with the giant spin Hall effect of tantalum. Science 336, 555 (2012).

Kim, J., Sheng, P., Takahashi, S., Mitani, S. & Hayashi, M. Spin Hall magnetoresistance in metallic bilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 097201 (2016).

Pai, C.-F. et al. Spin transfer torque devices utilizing the giant spin Hall effect of tungsten. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 122404 (2012).

Niimi, Y. et al. Extrinsic spin Hall effect induced by iridium impurities in copper. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 126601 (2011).

Yamanouchi, M. et al. Three terminal magnetic tunnel junction utilizing the spin Hall effect of iridium-doped copper. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 212408 (2013).

Fert, A. & Levy, P. M. Spin Hall effect induced by resonant scattering on impurities in metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 157208 (2011).

Cramer, J. et al. Complex terahertz and direct current inverse spin Hall effect in YIG/Cu1−xIrx bilayers across a wide concentration range. Nano Lett. 18, 1064–1069 (2018).

Masuda, H., Seki, T., Lau, Y.-C., Kubota, T. & Takanashi, K. Interlayer exchange coupling through Ir-doped Cu spin Hall material. Phys. Rev. B 101, 224413-1–10 (2020).

Niimi, Y. et al. Giant spin Hall effect induced by skew scattering from bismuth impurities inside thin film CuBi alloys. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 156602 (2012).

Ramaswamy, R. et al. Extrinsic spin Hall effect in Cu1−xPtx. Phys. Rev. Appl. 8, 024034 (2017).

Tian, K. & Tiwari, A. CuPt alloy thin films for application in spin thermoelectrics. Sci. Rep. 9, 3133 (2019).

Wong, G. D. H. et al. Thermal behavior of spin-current generation in PtxCu1−x devices characterized through spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance. Sci. Rep. 10, 9631 (2020).

Gu, B. et al. Surface-assisted spin Hall effect in Au films with Pt impurities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 216401 (2010).

Obstbaum, M. et al. Tuning spin Hall angles by alloying. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 167204 (2016).

Laczkowski, P. et al. Experimental evidences of a large extrinsic spin Hall effect in AuW alloy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 142403 (2014).

Ishikuro, Y., Kawaguchi, M., Kato, N., Lau, Y.-C. & Hayashi, M. Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction and spin–orbit torque at the Ir/Co interface. Phys. Rev. B 99, 134421 (2019).

Chakrabarti, D. J. & Laughlin, D. E. in Cu–Ir (Copper–Iridium), Binary Alloy Phase Diagrams 2nd edn, Vol. 2 (ed. Massalski, T. B.) 1426–1427 (1990).

Flipse, J. et al. Observation of the spin Peltier effect for magnetic insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 027601 (2014).

Daimon, S., Iguchi, R., Hioki, T., Saitoh, E. & Uchida, K. Thermal imaging of spin Peltier effect. Nat. Commun. 7, 13754 (2016).

Straube, H., Wagner, J.-M. & Breitenstein, O. Measurement of the Peltier coefficient of semiconductors by lock-in thermography. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 052107 (2009).

Breitenstein, O., Warta, W. & Langenkamp, M. Lock-in Thermography: Basics and Use for Evaluating Electronic Devices and Materials (Springer, Berlin and Heidelberg, 2010).

Wid, O. et al. Investigation of the unidirectional spin heat conveyer effect in a 200 nm thin yttrium iron garnet film. Sci. Rep. 6, 28233 (2016).

Daimon, S., Uchida, K., Iguchi, R., Hioki, T. & Saitoh, E. Thermographic measurements of the spin Peltier effect in metal/yttrium–iron-garnet junction systems. Phys. Rev. B 96, 024424 (2017).

Seki, T., Iguchi, R., Takanashi, K. & Uchida, K. Visualization of anomalous Ettingshausen effect in a ferromagnetic film: direct evidence of different symmetry from spin Peltier effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 152403 (2018).

Uchida, K. et al. Combinatorial investigation of spin–orbit materials using spin Peltier effect. Sci. Rep. 8, 16067 (2018).

Barrett, C. S. & Massalski, T. B. Structure of Metals: Crystallographic Methods, Principles and Data (Pergamon, 1980).

Yamazaki, T., Iguchi, R., Ohkubo, T., Nagano, H. & Uchida, K. Transient response of the spin Peltier effect revealed by lock-in thermoreflectance measurements. Phys. Rev. B 101, 020415(R) (2020).

Pi, U. H. et al. Tilting of the spin orientation induced by Rashba effect in ferromagnetic metal layer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 162507 (2010).

Kim, J. et al. Layer thickness dependence of the current-induced effective field vector in Ta|CoFeB|MgO. Nat. Mater. 12, 240–245 (2013).

Garello, K. et al. Symmetry and magnitude of spin–orbit torques in ferromagnetic heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 587 (2013).

Avci, C. O. et al. Interplay of spin–orbit torque and thermoelectric effects in ferromagnet/normal-metal bilayers. Phys. Rev. B 90, 224427 (2014).

Lau, Y.-C. & Hayashi, M. Spin torque efficiency of Ta, W, and Pt in metallic bilayers evaluated by harmonic Hall and spin Hall magnetoresistance measurements. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 56, 0802B5 (2017).

Nguyen, M.-H., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Spin torque study of the spin Hall conductivity and spin diffusion length in platinum thin films with varying resistivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 126601 (2016).

Uchida, K., Daimon, S., Iguchi, R. & Saitoh, E. Observation of anisotropic magneto-Peltier effect in nickel. Nature 558, 95–99 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank I. Narita for technical support to do the composition analysis and M. Isomura for substrate preparation. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) (JP18H05246), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (JP19H02585), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (JP20H00299), and JST CREST “Creation of Innovative Core Technologies for Nano-enabled Thermal Management” (JPMJCR17I1). The device fabrication was partly carried out at the Cooperative Research and Development Center for Advanced Materials, IMR, Tohoku University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.S. and K.U. conceived the idea, and planned and supervised this study. H.M. and R.M. carried out the sample preparation and the structural characterization with the help from Y.S., K.U., and T.S. The LIT measurement and its analysis were performed by H.M. and K.U. with input from R.I., and the harmonic Hall measurement was done by H.M. and Y.C.L. T.S. wrote the paper with input from K.U., R.M., Y.C.L., R.I. and K.T. All of the authors contributed to the understanding of physical mechanism.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Masuda, H., Modak, R., Seki, T. et al. Large spin-Hall effect in non-equilibrium binary copper alloys beyond the solubility limit. Commun Mater 1, 75 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-020-00076-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-020-00076-0

This article is cited by

-

Autonomous closed-loop exploration of composition-spread films for the anomalous Hall effect

npj Computational Materials (2025)

-

High-throughput materials exploration system for the anomalous Hall effect using combinatorial experiments and machine learning

npj Computational Materials (2025)