Abstract

Ceramic matrix composites (CMCs) play an important role in various load-bearing applications. However, fabricating CMCs with both high toughness and stiffness, which are normally mutually exclusive properties, is challenging. Here, we develop an SiOC composite film reinforced with nanoscale tungsten-based particles with a structure and property gradient by integrating hybrid nanoparticle inkjet printing and selective laser sintering. Mechanical results of the resulting SiOC-WOx films exhibit a stiffness-toughness co-enhancement, including a 2-fold improvement in hardness and modulus, and a 3.8-fold better fracture toughness than the matrix material. Moreover, the films exhibit interfacial bonding strengths of up to 86.6 MPa and operate stably at 1050 °C. This performance is attributed to a gradient in the metal-to-ceramic composition and uniformly dispersed self-assembled nanoscale reinforcing particles. This nanoparticle laser sintering method could be used to prepare other materials with structure and property gradients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ceramic films are indispensable in the fabrication of reinforced coatings, which serve as robust protectors of metallic substrates against wear, corrosion, and high-temperature creep. These ceramic-reinforced metallic materials find extensive applications across a diverse array of industries, including aerospace1,2, precision sensors3, and energy storage4. To cater to the varied demands of these applications, a multitude of coating techniques has been employed to fabricate ceramic thin films. These methods include physical and chemical vapor deposition5,6, laser deposition7, and spraying8 techniques. While these approaches are prevalently utilized in numerous industrial applications for thin film fabrication, they encounter significant challenges when composite structures or controlled multi-component are required in two-dimensional films9.

Since the traditional ceramic materials have low fracture toughness and tensile strength, which would give rise to a sudden plastic deformation when carrying heavy loads10, the composite materials such as ceramic matrix composites (CMCs) that would notably enhance the ceramic toughness attract significant research attentions in recent years. The matrix phase of the CMC material is reinforced by the doping phases which are normally composed of fibers or nanoparticles (NPs)11,12. These multiphase nanoparticles undergo sintering, resulting in a distinctive distribution structure within the CMC components, endowed with enhanced toughness and strength13,14. Recent years have witnessed the utilization of advanced CMC materials in sophisticated components such as brake discs for high-speed rail, combustor liners and guide vanes for aero-engines, etc.15. However, almost all the applications of CMCs in industry are in component (bulk materials) level, where the thin film CMC application is relatively rare, because the conventional thin film deposition techniques are not compatible with composite thin film preparation16.

Gradient materials, which combine multiple materials on demand to achieve synergistic properties, show potential for enhancing the photovoltaic, thermoelectric, and mechanical properties of materials. For instance, Albert et al.17 explored high-temperature amalgamation of superconducting rare-earth barium copper oxide precursor solutions encompassing distinct rare earth elements through the ink-jet printing technique. Similarly, Zhang et al.18 delved into the preparation of gradient films, and they prepared gradient compositional alloy films by mixing Ru and Pt ink streams on-site using an aerosol jetting method. Building on this foundation, they extended their efforts to craft gradient thin films founded on multi-species and multi-dimensional material gradients9. In addition to the direct-writing technique, Lu et al.19 applied powder feed laser additive manufacturing to fabricate gradient glasses with high strength and tensile ductility in a stacked layer approach. Furthermore, the application of a reinforced ceramic film on the surface of a metal substrate becomes particularly appealing when it exhibits gradient properties. Upon the fabrication of a ceramic layer with gradient properties, it serves the dual purpose of a protective layer and a transition layer, effectively addressing the interfacial bonding issues arising from mismatches in the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE)20. Hence, the development of gradient ceramic films with meticulously controlled compositions and properties, leveraging the high throughput capabilities of directly written hybrid nanoparticles, holds significant promise for advancement in reinforced ceramic film21,22.

To sum up, the existing ceramic matrix composites suffer from the well-known trade-off between toughness and stiffness, which leads to difficulties in balancing the mechanical properties of ceramic materials. When it comes to ceramic films, the interfacial bonding strength enhancement is a critical issue. To improve the toughness and interfacial bonding strength of ceramic coatings/films simultaneously, we developed SiOC-WOx CMC films with gradient properties in this work. The external surface of SiOC-WOx film consists mainly of a dense glass phase SiO2 with high hardness and oxidation resistance, while the internal layer gradually transitions to a metallic state. The method of laser sintering hybrid nanoparticles, as proposed in this study, is anticipated to be broadened to encompass different varieties of metallic, semiconducting, and insulating ceramic nanomaterials for the production of gradient films.

Results and discussions

Developments of SiOC-WOx CMC self-gradient films

In the current work, the SiOC-WOx gradient-property films were prepared with the ink-jet printing method, where the nano-ink of functional materials was deposited in a specific pattern. The SiC and W NPs were dispersed in the mixture of isopropyl alcohol and ethylene glycol, which formed the nano-ink suspension for printing (Fig. 1a). An ink-jet printing system was employed to deposit the nano-ink on the target surface (Fig. 1b). After the evaporation of the solvent, the residual nanoparticles on the target substrate were sintered with a laser into a densified film (Fig. 1c). Supplementary Fig. 1 presents a photo of SiC and W hybrid nanoparticles deposition and SiOC-WOx film after laser sintering. The gradient performance of the film could be established in two levels. First, as shown in Fig. 1d, the stratification of SiC and W NPs was generated due to the density difference during the evaporation of sessile nano-ink droplets. Second, as shown in Fig. 1e, the variations of energy distribution and oxygen content in the laser sintering drives a diverse degree of sintering and oxidation in different depths, which gave rise to a gradient performance of the film. More details can be found in the “Methods" section.

a–c Schematic diagram for the fabrication of SiOC-WOx gradient CMC films with ink-jet printing and laser sintering. d, e Two mechanisms of self-gradient establishment. In the ink-jet printing, the SiC and W nanoparticles are deposited in a transitional manner in the depth direction due to the large density difference. In the laser sintering, the oxidation and densification of CMC vary in the depth direction.

The mechanical and electrical properties of SiOC-WOx films are closely related to the ratio of composition and the degree of sintering. The SiC, which guarantees the high hardness and insulation of films, is difficult to be sintered/melted by Nd:YAG laser due to its low fracture toughness and low absorptance to 1064 nm radiation23. To improve the absorptance of nanoparticles and thus increase the sintering temperature, the use of W NPs with high melting points as absorbers. The results demonstrate that optimal performance with minimal porosity can only be achieved through sintering with an appropriate laser energy density (Ed ≈ 60 J/mm2) at suitable SiC and W molar ratios (around 1:1). The variation of sintering state with component ratio and laser energy density is discussed as follows.

Figure 2a summarizes the typical SEM images of the sintered film with a variety of laser energy density, Ed, and molar ratio of SiC and W. When the laser energy density is relatively low (Ed = 30 J/mm2), the preliminary necking of nanoparticles can be observed due to the surface diffusion. A large porosity reveals a poor sintering state at such low energy density. However, the porosity of the sintered sample reduces once the W NPs is added (designed molar ratios of SiC:W = 2:1) compared to the pure SiC. The results can be inferred that the W NPs served as the absorber of laser24. Once the energy density is elevated to Ed = 45 J/mm2, the necking of pure SiC is promoted. Similarly, adding W NPs shows a lower porosity and larger size of grains, which represents a better sintering state. Notably, once the ratio of SiC:W = 1:1, a unique state of sintering is established, in which the pores disappear and a “rock-embedded” pattern is observed. The embedded “rocks” may serve as the reinforcement phase to form composite material in the macroscopic view. This pattern cannot be observed in the cases of a higher percentage of W. In the case of Ed = 60 J/mm2, the embedded “rocks” are smaller in size, more spherical in shape, and distributed more uniformly. The macroscopic observation of the SiOC-WOx films also exhibits excellent uniformity without cracks (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). However, once the energy density increases to Ed = 75 J/mm2, the “rock-embedded” pattern is no longer existing according to the SEM image. Furthermore, the peeling off of the sintered layer was observed in the experiments, indicating that the layer was over-sintered.

a Significant micro-morphological differences are observed with different sintering materials (with different ratios of SiC:W) and different sintering energy (Ed). With an increase in the content of W NPs, the porosity of the sintered body decreases, indicating that W serves as the laser absorber that facilitates sintering. b A unique “rock-embedded" dense morphology is formed in the case of SiC:W = 1:1, Ed = 45 J/mm2 and 60 J/mm2. The EDS image reveals that the spherical “rock" is enriched with element W. c The uniformity of the “rock-embedded" pattern should be induced by the mixing in the “melting pool" during the sintering.

To further examine the characteristics of the “rock-embedded” pattern, the slice of the sintered sample was tested with TEM and EDS. As shown in Fig. 2b, the element Si is uniformly distributed in the sample whereas the element W is only distributed in the area of the embedded “rock”. The results suggest that the matrix phase of the sintered composite material is enriched in elemental Si (either SiC or its oxidized phase), where the reinforcement phase ("rocks”) may be W or its oxide. The mechanism of the “rock-embedded” pattern formation can be inferred as follows. As shown in Fig. 2c, during the sintering process, the lower melting point phase (SiC) melts to a large extent while the higher melting point phase (W) remains solid (the physical parameters of SiC, W bulk and nanomaterials were calculated and summarized in Supplementary Table 1), resulting in the formation of a melting pool that contains both liquid and solid materials25. Moreover, due to the Gaussian beam of the laser, a large temperature gradient as well as a surface tension gradient could be formed from the center to the edge of the melting pool26,27. Therefore, a Marangoni convection could be generated28, which results in an internal melt flow that promotes the rearrangement of the solid phase nanospheres, leading to their uniform distribution. Moreover, the increase of Ed facilitates the elevation of the temperature gradient, further optimizing the distribution uniformity and dopant homogeneity.

Gradient composition and composite structure

Although the distributions of elements Si and W can be determined with EDS, as shown in Fig. 2b, the specific substances that contain those two elements, are still unknown. Thus, characterizations such as XPS, SIMS, etc. are further conducted. As shown in Fig. 3a, the XPS survey spectra of sintered films underscore the dominance of O, W, Si, and C elements on the film surface, confirming the credibility of the sample and the occurrence of oxidation. The specific narrow-spectrum analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3) of the O1s reveals that the atom ratio of W:Si is around 3:7, contrasting to the ratio of 1:1 in the original nano-ink, which verifies the formation of gradient deposits of SiC and W NPs. With the aid of argon ion beam etching technique, a depth direction analysis could be conducted to measure the elemental fractions of Si and W in the depths of 0 (surface), −20, −40, and −60 nm. The specific narrow-spectrum analysis Si reveals that the Si-C peak is absent and the percentage of Si-O is 100% at the surface (h = 0 nm), as shown in Fig. 3b, indicating a complete oxidation at the interface, but it reduces to 83.6% in the depth of h = −20 nm. The ratio of Si–C:Si-O almost does not change with a further increase in depth. However, the results show that the surface is completely covered by WO3 since the percentage of W6+ is 100% at h = 0 nm. Unlike the ratio of Si-C:Si–O, the ratio of W6+:W4+:W consistently changes with an increase in depth from 0 to 60 nm. The percentage of singlet W changes from 9.8% to 18.6%, where the W6+ reduces from 67.2% to 53.9% comparing the data of h = −20 and −40 nm. Compared to XPS, which is only able to characterize the variations of elements in a small depth of sample (less than 10 nm), the SIMS technique can test a much wider range of depth (0 > h > 750 nm, in current work) yet with less quantitative data. As shown in Fig. 3c, a turning point of h = −20 nm can be distinguished for all the five tested ions, which indicates that the oxidation mainly happens in the thin layer beneath the surface. The SIMS results are also in accordance with the XPS results (Fig. 3b), where an abrupt change of Si-O percentage and W valence state between h = 0 and −20 nm is observed. Furthermore, on the one hand, the intensity of Si+ and SiO+ approaches a constant value with an increase in depth, so that the XPS conclusion that the percentage of Si–C and Si–O is almost constant at −20 nm > h > −60 nm can be generalized to h > −750 nm. A 3D distribution of ionic strengths based on SIMS data is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4 for a more visual representation of the elemental gradient distribution. The matrix, beneath 20 nm, is amorphous SiOC, which is a SiO4−xCx building block formed by the diffusion of external oxygen atoms into the silicon carbide lattice29,30, known for its outstanding high-temperature stability and mechanical properties31. The chemical formula can be approximated as SiO(1.32−1.48)C(0.26−0.34) based on the XPS semiquantitative results32,33. On the other hand, an apparent decrease of the intensity of \({{{{{{{{\rm{WO}}}}}}}}}_{2}^{+}\) or WO+ are observed, indicating that the degree of oxidation of W is reducing along the depth. Overall, the matrix phase (SiOC) exhibits a sudden decrease in oxidation with increasing depth, the reinforcing phase (WOx), however, shows a gradual decrease.

a XPS survey spectra underscore the dominance of O, W, Si, and C elements on the film surface. b XPS survey assisted with etching techniques is employed to characterize the sample in different depths (h = 0, −20, −40, and −60 nm). Aside from the external surface (h = 0), the oxidation of Si almost does not change with depth in the tested conditions. However, the oxidation of W decreases with an increase in depth. c SIMS characterization results (throughout 0 to −750 nm) show that the Si and W components change drastically in the very thin layer (around 20 nm beneath the surface) which is consistent with the XPS results. In the deeper region (−20 nm > h > −750 nm), the degree of oxidation of Si is almost constant while the oxidation of W decreases gradually. d TEM characterization of a sample slice at h = −6500 nm. Aside from the external surface, the “rock-embedded" morphology is also observed in the deep region of the sintered layer. e, f HRTEM and SAED images reveal that the W-abundant spherical phase is either W monocrystalline or polycrystalline W-composition. g Intensity unfolding treatment of a polycrystalline ring clarifies that the polycrystalline W-composition consists of W and WO3.

The previous characterizations reveal the contents of elements in each depth. However, a heterogeneous property is anticipated for the “rock-embedded” composite material even in the same depth. Therefore, it is important to investigate the variations of each substance in the same depth. Figure 3d shows the TEM imaging of a slice of sample in the depth of h = −6500 nm (bottom layer of the film with a thickness of 7200 ± 300 nm). As reported in Fig. 2b, the W element only exists inside the circular areas. In order to determine the specific substances inside the circles, the High-Resolution TEM (HRTEM) images were captured and the Selected Area Electron Diffraction (SAED) was performed. As shown in Fig. 3e, a clear lattice is observed, where the spacing can be precisely measured, the data suggest that the substance is W monocrystalline. The corresponding SEAD image shows a superlattice pattern, which also confirms a monomer substance. However, in some circular regions, irregular lattice arrangements are observed, as shown in Fig. 3f. The SAED image gives a ring pattern, and the data of intensity reveals that WO3 and W monomers coexist in this circular area, as illustrated in Fig. 3g.

Based on the characterization results discussed previously, the gradient properties of SiOC-WOx films can be demonstrated from three different aspects: Si-to-W atomic ratio, degree of oxidation, and grain size, as indicated in Fig. 4. Specifically, Fig. 4a shows an increasing trend in W content and a decrease in Si content in the deeper region of the film, according to the measurements of FIB-EDS (refer to the scanning path in Supplementary Fig. 5). These variations in the contents of W and Si are attributed to the different settling behaviors caused by the significant density difference between the two elements (Supplementary Table 1). Figure 4b illustrates the change in oxidation levels of Si and W is presented. It is observed that the oxidation of Si sharply decreases at the outermost surface (0 > h > −20 nm), while the oxidation of W decreases gradually. The decrease in oxygen partial pressure should be responsible for the reduction of oxidation of Si and W. The gradual decrease in the size of the WOx reinforced phase with depth (Fig. 4c) should result in variations of sintering temperature and oxidation. First, the significant laser absorption by the superalloy34 gives rise in a higher sintering temperature at the bottom of the film, which promotes grain refinement28. Second, the metal oxidation helps to increase grain size by incorporating oxygen atoms into the lattice structure35. Therefore, the lower oxidation in the inner layers may contribute to the reduction in grain size.

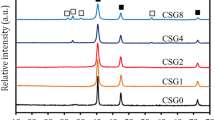

The high temperature generated by the laser on the surface of the substrate is considered to be the basis for powder bed fusion (a “layer-by-layer” additive manufacturing technology), which guarantees the strength of the component. Similarly, diffusion is the key to strengthening the bonding between the film and the substrate36. In order to determine whether the diffusion happens, the following experiments are conducted. After the laser sintering of the deposited layer of W and SiC NPs, the sintered film is sanded to show the bare substrate. Then the substrate is cleaned with propanol and is etched by a depth of 10 nm to further remove the residues of the sintered layer. Finally, the XRD is performed to characterize the material of the substrate after laser sintering. As shown in Fig. 5a, the WO3 peaks were observed, which could be attributed to the oxidation of the W monomer that diffused into the superalloy during the cleaning and etching process. In addition, the main peak of the nickel substrate shifted to a lower diffraction angle after the preparation of the gradient film (inset of Fig. 5a), which is an indication of the doping of larger heteroatoms (W) in the Ni-Cr-Fe system37. What is more, the relative intensities of the [Ni,Fe] and [Cr,Fe] main peaks changed, which could be a result of the solid solution. Figure 5b shows the cross-sectional morphology of SiOC-WOx film captured by FIB-SEM, where the local magnification shows the interface between the film and the superalloy in close proximity to each other, as well as the difference in the lightness and darkness of the film’s underlying layer due to the diffusion of the elements (the penetration of the [Fe, Cr, Ni] with a small atomic number into the film, which leads to the darkening).

a XRD analysis of the substrate (after removing the sintered CMC film) shows that the W element in the CMC film diffuses into the substrate of Inconel 625 superalloy since the peak of WO3 appears and the peaks of [Ni,Fe] and [Cr,Fe] shift to a smaller diffraction angle. b The tightly packed interfaces in the SEM images with permeable grayscale confirm elemental diffusion.

Properties and performance of SiOC-WOx CMC self-gradient films

As aforementioned, the composition and other properties of the prepared SiOC-WOx film change along the depth of the film. The gradient film is normally corresponding to a gradient mechanical property, including hardness, Young’s modulus, etc. Therefore, the characterizations of the mechanical properties are important. In this work, the hardness and modulus of the films were evaluated with the continuous stiffness nanoindentation technique, as shown in Fig. 6a, b. The results show that the surface hardness of the gradient films could reach 20 GPa, which are comparable to those of glassy phase SiO2 even SiC ceramics, and are much higher than those of Inconel 625 superalloy (below 5 GPa)38. The extremely high surface hardness may benefit from the dual effect of WO3 doping enhancement as well as laser stamping enhancement. The variations of hardness and Young’s modulus of the films are similar. Both of the parameters decrease abruptly in the thin layer at the surface (0 > h > −20 nm), after which decreasing trend slows down considerably. This unique mechanical property is inextricably linked to the abrupt transition in the oxidation of the matrix. On one hand, the dense glassy phase SiO2 with high hardness on the surface has high hardness and wear resistance; on the other hand, the enriched WOx in the inner layer shows a lower Young’s modulus, which can be served as stress-absorbing material, thus reducing the risk of brittle fracture and damage to the surface with a high modulus.

a, b The hardness and modulus of SiOC-WOx films both decrease rapidly in a thin layer beneath the external surface (0 > h > − 60 nm). c Comparison of the SiOC-WOx film property with metal, glass47,48,49 and ceramic50,51,52,53,54,55,56 materials in Hardness-Modulus space. The film has a transitional property from ceramic (at the external surface) to metal (deep inside the film).

Since Fig. 6a, b shows the variations of E and H against depth, it is interesting to plot the data in the E–H space, as shown in Fig. 6c (five sets of data are averaged). Unlike homogeneous materials, whose mechanical properties are exhibited as fixed dots in the E–H space, the E–H dots of the gradient films are dispersed at different depths, and we fitted all the data points to obtain a curve of variation of the E–H properties of the gradient films with depth. The top of the curve represents the high hardness and high modulus of the film surface, and both E and H gradually decrease with increasing depth, which is closely related to the change of compositions inside the film. In addition, the hardness and modulus of the gradient films were compared to metal, glass, and ceramics. The gradient films exhibited ceramic/glass-like properties on the surface and metal-like properties in the internal layers. The specific “gradient mechanics properties” of SiOC-WOx are believed to be attributed to the variation of the composition and microstructure in the depth direction. Specifically, the oxidation variations (determined by XPS, Fig. 3b) and content fraction variations (determined by XPS and EDS, Supplementary Figs. 3, 6) of SiOC (matrix) and WOx (reinforcing phase), as well as the size of the spherical dopant, are responsible to the gradient properties of the films, as shown in Fig. 4e, f.

Based on Young’s modulus and hardness measured by the continuous stiffness method, the fracture toughness and interfacial bonding strength of the films were further investigated by nanoindentation and scratching techniques. The fracture toughness can be calculated by the classical formula proposed by Anstis et al.39,

where E and H are Young’s modulus and vickers hardness, respectively. P is the maximum indentation load, and c is the crack half-length. The nanoindenter is pressed in with P = 200mN, and the crack half-length is 2.3 μm (Supplementary Fig. 7). Since the indentation depth is about 200 nm, the average hardness and modulus of the gradient film at 0 > h > −200 nm are used for the calculation, which can be calculated from the results of the continuum stiffness test (E ≈ 20GPa, H ≈ 2GPa). The fracture toughness of the film can be calculated as KIC = 2.88MPa m0.5, which is 380% of the fracture toughness of the matrix.

It is widely accepted that strength and toughness are mutually exclusive40. Therefore, the extent of simultaneous enhancement in strength and toughness serves as a dependable metric for assessing the mechanical property improvements in composites41,42. Hence, we adopted the \(H/{H}^{{{{{{{{\rm{matrix}}}}}}}}}\cdot {K}_{{{{{{{{\rm{IC}}}}}}}}}/{K}_{{{{{{{{\rm{IC}}}}}}}}}^{{{{{{{{\rm{matrix}}}}}}}}}\) as an index to measure the combined enhancement of the mechanical properties from the matrix by the composite technology (hardness, which is positively correlated with strength, was chosen due to the difficulty of determining the strength of the film material) and the values of the gradient films were compared in H - K space with those of the other ceramic-based composites reported in the literature, as shown in Fig. 7a. The result shows that the composite strategy of SiOC-WOx thin films exhibits the maximum improvement in the integrated mechanical properties. As shown in Fig. 7b, the improvement in the integrated mechanical properties is attributed to the inclusion of ductile (metallic) inclusions in the ceramic matrix, where ductile phase toughening plays an important role43. The passivation of the crack tip when it reaches the ductile inclusions, the stress-releasing plastic deformation of the ductile particles in the crack growth process region, and the bridging effect of the ductile phase particles44 all hinder the crack expansion and thus enhance the film toughness, and these phenomena were observed in the SiOC-WOx films, as shown in Fig. 7b.

a Fracture toughness enhancement \({K}_{{{{{{{{\rm{IC}}}}}}}}}/{K}_{{{{{{{{\rm{IC}}}}}}}}}^{{{{{{{{\rm{matrix}}}}}}}}}\) and hardness enhancement H/Hmatrix of SiOC-WOx films relative to the matrix material. The fabricated SiOC-WOx film in this work exhibits distinguished properties compared to the common CMC materials22,35,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72. b Mechanism of ductile-phase toughening and crack extension analysis in SiOC-WOx CMC films. The crack expansion process of the SiOC-WOx CMC film confirms that the toughening is reached by fracture of ductile grains (I), exfoliation of ductile grains (II), plastic deformation of ductile grains (III), and crack-tip passivation (IV), which is in accordance with the classic theory of toughening.

As aforementioned, element W was shown to diffuse into the nickel-based superalloy substrate, which may enhance the interfacial bonding strength between the two. In support of the view, we determined the interfacial bonding strength by nano-scratching experiments (a diamond indenter is scratched across the film surface at a defined rate while increasing the load, Ft, applied to the indenter until the film peels off and the first plunge of the curve is observed at X = 0.28 mm, as shown in Fig. 8a). Based on the values of the critical load Lc, the width of the scratch groove dc, Poisson’s ratio νs and the friction coefficient μ, the bonding strength of the film can be calculated as follows,

where the critical load Lc = 0.053 ± 0.01 N (as shown in Fig. 8a), the scratch groove width dc = 0.037 mm, friction coefficient μ could be calculated by Eq. (3)45.

Where, hs and R are the in-situ scratch depth and indenter tip radius, respectively, which are determined (hs = 3446 nm, R = 2000 nm). However, the measurement of Poisson’s ratio for thin film materials is impractical. Notably, the Poisson’s ratio of common materials (including metals and ceramics) is generally distributed in the interval of 0.1 - 0.4. Thus, it is reasonable to assume a Poisson’s ratio of 0.25 ± 0.15 for SiOC-WOx films. Therefore, taking νs and μ into Eq. (2), σ = 86.6 ± 26.5 MPa can be calculated, which achieves the optimal level of interfacial bonding strength for the ceramic-based films fabricated on metal substrates (20 MPa < σ < 100 MPa)46,47.

The ceramics are widely used in high-temperature environments, especially in aerospace applications. Therefore, the stability of ceramic material in high-temperature environments is worth investigating. In current work, as shown in Fig. 8b the electrical resistance of the film is measured in a wide range of temperatures (20–1050 °C), which is compared with Al2O3, the good high-temperature insulating ceramic47. Typically, as the temperature increases, the insulation of the film decreases due to the elevated electron energy and the prominence of film defects, as seen in the change of resistance in Al2O3 films. However, the insulation of SiOC-WOx films improves with increasing temperature up to 400 °C, which may be due to the lower electrical activation energy produced by polariton conduction mechanism as a result of laser sintering48,49. Above 400 °C, the SiOC-WOx films show a similar trend to that of the Al2O3 films. At this stage, SiOC-WOx exhibits relatively high insulation resistance, which is less than an order of magnitude different from that of Al2O3 films. Moreover, with the increase of temperature, the insulating property of SiOC-WOx gradually approaches that of Al2O3 film (52% at 1050 °C, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8), demonstrating its good insulation and stability at high temperature. In summary, the SiOC-WOx film exhibits excellent integrated mechanical properties and high-temperature stability, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 2.

Conclusions

In this study, a ceramic matrix composite (CMC) films (amorphous SiOC matrix reinforced with nanoscale WOx particles) with gradient properties fabricated by laser sintering of hybrid nanoparticles is proposed. The findings could be summarized as follows.

-

(1)

Self-assembled composite structures embedded with uniformly dispersed nanoparticles. Attributed to the laser-induced liquid-phase melting flow, the CMC films with uniform “rock-embedded” morphologies could be prepared under a processing parameter (the nanoparticle ratio of SiC:W = 1:1 and the laser energy density of Ed = 60 J/mm2).

-

(2)

External surface with both high toughness and high strength. The fracture toughness and hardness of the film are 3.8 and 2.3 times of the matrix material, respectively. According to the characterizations, the good fracture toughness and the high hardness attribute to the “ductile-phase toughening" effect induced by the uniform doping of WO3 nanospheres and the formation of dense amorphous SiOC matrix, respectively.

-

(3)

Gradient properties and the associated high interfacial bonding strength and high-temperature stability. With an increase in depth, both the hardness and modulus decrease. The properties of the films gradually approach those of the metal substrate in the depth direction, which results in a relatively high bonding strength of 86.6 MPa at the interface and stable operation at 1050 °C. The gradient properties are attributed to the variations of the oxidation and densification of SiOC matrix phase and WOx reinforcing phase, and the high interfacial strength benefits partially from the enrichment of W close to the interface and partially from the elemental diffusion to the superalloy.

Methods

Nano-ink preparation

The preparation of SiC and W nano-ink was carried out by mixing ethylene glycol (99.9% purity, Macklin, China) and isopropyl alcohol (99.9% purity, Macklin, China) with a volume ratio of 3:5 as the solvent. The solutes used in the nano-ink were W and SiC NPs Deke Daojin, China) with an average size of 50 nm. The SiC-W hybrid nano-inks with various design molar ratios were prepared by weighing SiC and W NPs, aligning with the ratios depicted in Fig. 2a. The concentration of all nano-inks was 250 mg/ml. A small amount of polyvinylpyrrolidone powder, with a molecular weight of 58000 (99.99% purity, Macklin, China), was added as a suspension stabilizer at a concentration of 2.5 mg/ml. The mechanical dispersion of the nano-ink was carried out using an ultrasonic crusher (Scientz-IID, Scientz, China) at 150 W for 300 minutes. The temperature of the dispersion system was kept at 10 °C using a water bath. After the mechanical dispersion, the dispersed nano-inks were filtered through a 0.45 μmpore size polytetrafluoroethylene filter membrane to remove any large aggregated particles and produce fine SiC-W nano-inks suitable for ink-jet printing.

High-throughput ink-jet printing

The SiC-W nano-ink was deposited onto a flat superalloy substrate in the form of 20 μm diameter droplets using an ink-jet printer (Jetlab 4xl, MicroFab, America). Inconel 625 superalloy with excellent high-temperature mechanical properties was chosen as the substrate because of the testing needs for the high-temperature properties of SiOC-WOx thin films. Before ink-jet printing, the Inconel 625 substrate was cleaned using an ultrasonic cleaner with sequential treatments of isopropyl alcohol, ethanol, and ultrapure water for 3 min, followed by drying in a hot oven. To expedite solvent evaporation and enhance deposition uniformity, the substrate temperature was heated to 160 °C during the ink-jet printing, where a PID controller was employed to maintain the temperature. The deposition area is rectangular with 3 × 30 mm2 to verify the feasibility of depositing large-size line segments.

Selective laser sintering

The deposited nanoparticles are sintered with a single-mode pulsed laser (P50QB, Raycus, China) with a wavelength of 1064 nm, which is able to generate localized high temperatures in the surface layer of deposition. The pulse width of the laser is about 130 ns and a repetition frequency of about 80 kHz. The laser beam was controlled by a programmable Galvanometer Scanner (GS) system (RC1001-R, Jinhaichuang, China).

Characterizations

The characteristics of the gradient composite films are tested as follows. A field emission scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi SU8020, Japan) was employed for morphological observations. An X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (250XI, Thermo Fisher, USA; the source is a monochromatic Al Kα, hν = 1486.6eV, with the power of 150 W, beam spot of 650 μm, voltage of 14.8 kV, current of 1.6 A; the charge correction is performed with contaminated carbon C1s = 284.8 eV; the full-spectrum flux is 100 eV in steps of 1 eV, and the narrow-spectrum flux is 20 eV in steps of 0.1 eV) was used for compositional and content analyses. A secondary ion mass spectrometer (SIMS 5, Iontof, Germany) was used for compositional analyses; and an X-ray powder diffractometer (Bruker D8 Advance, Germany; a Cu target wavelength of 1.5406 Å, a tube current of 40 mA, a tube voltage of 40 kV; a sampled in a step-scan mode with a step of 0.02° and the scan rate is 4°/min). The composition and content were analyzed with a field emission transmission electron microscopy (FEI Talos F200, Thermo Fisher, USA) and an energy dispersive spectrometer (X-MAXe, Oxford, UK).

Additionally, the mechanical and electrical properties of the films were also characterized. The variation of film hardness and Young’s modulus with depth was tested by continuous hardness testing (TI 950, Hysitron, USA) using a nanoindenter (Berkovich indenter, radius of curvature 150 nm, nip angle 65.27°). The film’s resistance in the depth direction was measured using an insulation resistance tester (RK2683-N, Rek, China). The thickness of the film was 7200 ± 300 nm, which was measured with an optical superfield microscope (DSX1000, Olympus, Japan). The test resistance nodes were attached using a high-temperature conductive graphite adhesive and placed in a tube furnace (BTF-1400C, BEQ, China) to determine the high-temperature insulation of the films. By utilizing high-temperature conductive graphite to securely bond the wire to the surface of the film and the bottom of the substrate, as shown in Fig. 8b, where the metal substrate resistance can be disregarded. The tube furnace provides a controlled high-temperature environment, and thus high-temperature insulation resistance can be measured.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files. Further data supporting the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Padture, N. P. Advanced structural ceramics in aerospace propulsion. Nat. Mater. 15, 804–809 (2016).

Ogawa, T. et al. Spontaneously formed nanostructures in double perovskite rare-earth tantalates for thermal barrier coatings. Acta Mater. 216, 117152 (2021).

Huangfu, G. et al. Giant electric field–induced strain in lead-free piezoceramics. Science 378, 1125–1130 (2022).

Yunwei, C., Xiaoyan, Y., Yuanyuan, C., Li, h & Deqiu, Z. Review on ceramic-based composite phase change materials: preparation, characterization and application. Compos. B: Eng. 254, 110584 (2023).

Choi, D. S. et al. Ultrastable graphene-encapsulated 3 nm nanoparticles by in situ chemical vapor deposition. Adv. Mater. 30, 1805023 (2018).

Yuan, B. et al. Physical vapor deposition of graphitic carbon nitride (g-c3n4) films on biomass substrate: optoelectronic performance evaluation and life cycle assessment. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 813–822 (2022).

Pan, H. et al. Ultrahigh–energy density lead-free dielectric films via polymorphic nanodomain design. Science 365, 578–582 (2019).

Chen, F., Yan, K., Zhou, J., Zhu, Y. & Hong, J. Multilayer graphene and ß-si3n4 whisker-reinforced porous si3n4 ceramics by spark plasma incomplete sintering. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 823, 141770 (2021).

Zeng, M. et al. High-throughput printing of combinatorial materials from aerosols. Nature 617, 292–298 (2023).

Penilla, E. et al. Ultrafast laser welding of ceramics. Science 365, 803–808 (2019).

Wang, W. et al. Additive manufacturing of fiber reinforced ceramic matrix composites: advances, challenges, and prospects. Ceram. Int. 48, 19542–19556 (2022).

Wong, J. et al. Triplet fusion upconversion for photocuring 3d-printed particle-reinforced composite networks. Adv. Mater. 35, 2207673 (2023).

Li, L. Micromechanical modeling of cyclic non-closure hysteresis loops of fiber-reinforced ceramic-matrix composites considering variable matrix fragmentation density. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 805, 140795 (2021).

Lin, L. et al. Microstructure and compression properties of a dual-phase FeCoCrMn high-entropy alloy. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5 (2022).

Liu, X., Shen, X., Gong, L. & Li, P. Multi-scale thermodynamic analysis method for 2d sic/sic composite turbine guide vanes. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 31, 117–125 (2018).

Sathish, M., Radhika, N. & Saleh, B. A critical review on functionally graded coatings: Methods, properties, and challenges. Compos. B: Eng. 225, 109278 (2021).

Queraltó, A. et al. Combinatorial screening of cuprate superconductors by drop-on-demand inkjet printing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 9101–9112 (2021).

Chen, J. et al. Printing noble metal alloy films with compositional gradient. Appl. Mater. Today 27, 101405 (2022).

Lu, Y. et al. Controllable additive manufacturing of gradient bulk metallic glass composite with high strength and tensile ductility. Acta Mater. 206, 116632 (2021).

Fan, X., Ma, X., Dang, X., Xue, J. & Cheng, L. In-plane thermal expansion behavior of dense ceramic matrix composites containing sibc matrix. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 40, 3414–3422 (2020).

Kim, C. K. et al. High-throughput metal 3d printing pen enabled by a continuous molten droplet transfer. Adv. Sci. 10, 2205085 (2023).

Soares, S. F., Fateixa, S., Trindade, T. & Daniel-Da-Silva, A. L. A versatile synthetic route towards gelatin-silica hybrids and magnetic composite colloidal nanoparticles. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 884–898 (2022).

Tolochko, N. K. et al. Absorptance of powder materials suitable for laser sintering. Rapid Prototyp. J. 6, 155–161 (2000).

Yap, C. Y. et al. Review of selective laser melting: materials and applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2 (2015).

Zhao, L., Macías, J. G. S., Douillard, T., Li, Z. & Simar, A. Unveiling damage sites and fracture path in laser powder bed fusion alsi10mg: Comparison between horizontal and vertical loading directions. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 807, 140845 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. A novel crack-free ti-modified al-cu-mg alloy designed for selective laser melting. Addit. Manuf. 38, 101829 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Laser powder bed fusion of poly-ether-ether-ketone/bioactive glass composites: processability, mechanical properties, and bioactivity. Compos. Sci. Technol. 231, 109805 (2023).

Gu, D. & Shen, Y. Direct laser sintered wc-10co/cu nanocomposites. Appl. Surf. Sci. 254, 3971–3978 (2008).

Scarmi, A., Sorarù, G. D. & Raj, R. The role of carbon in unexpected visco (an) elastic behavior of amorphous silicon oxycarbide above 1273 k. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 351, 2238–2243 (2005).

Wu, N., Wang, B. & Wang, Y. Enhanced mechanical properties of amorphous si oc nanofibrous membrane through in situ embedding nanoparticles. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 101, 4763–4772 (2018).

Su, R. et al. Accuracy controlling and mechanical behaviors of precursor-derived ceramic SiOC microlattices by projection micro stereolithography (PμSL) 3d printing. J. Adv. Ceram. 12, 2134–2147 (2023).

Pena-Alonso, R., Mariotto, G., Gervais, C., Babonneau, F. & Soraru, G. D. New insights on the high-temperature nanostructure evolution of SiOC and b-doped SiBOC polymer-derived glasses. Chem. Mater. 19, 5694–5702 (2007).

Luo, C., Tang, Y., Jiao, T. & Kong, J. High-temperature stable and metal-free electromagnetic wave-absorbing sibcn ceramics derived from carbon-rich hyperbranched polyborosilazanes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 28051–28061 (2018).

Chen, X., Zhang, M., Zhu, J., Tao, Z. & Qiu, L. Laser sintering of cu nanoparticles deposited on ceramic substrates: experiments and modeling. Addit. Manuf. 69, 103527 (2023).

Wozniak, J., Jastrzkebska, A., Cygan, T. & Olszyna, A. Surface modification of graphene oxide nanoplatelets and its influence on mechanical properties of alumina matrix composites. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 37, 1587–1592 (2017).

Tong, M., Fu, Q., Hu, D., Zhou, L. & Feng, T. Improvement of ablation resistance of CVD-HfC/SiC coating on hemisphere shaped c/c composites by introducing diffusion interface. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 41, 4067–4075 (2021).

Muthukumaran, S. & Gopalakrishnan, R. Structural, FTIR and photoluminescence studies of cu doped ZnO nanopowders by co-precipitation method. Opt. Mater. 34, 1946–1953 (2012).

Gao, Y. & Zhou, M. Superior mechanical behavior and fretting wear resistance of 3d-printed inconel 625 superalloy. Appl. Sci. 8, 2439 (2018).

Anstis, G., Chantikul, P., Lawn, B. R. & Marshall, D. A critical evaluation of indentation techniques for measuring fracture toughness: I, direct crack measurements. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 64, 533–538 (1981).

Launey, M. E. & Ritchie, R. O. On the fracture toughness of advanced materials. Adv. Mater. 21, 2103–2110 (2009).

Sun, C. et al. Embedding two-dimensional graphene array in ceramic matrix. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb1338 (2020).

Guo, L., Ma, Q. & Hu, Z. Fabrication, microstructure and high temperature stability of carbon fiber reinforced SiYOC composites. Ceram. Int. 47, 32104–32110 (2021).

Haag IV, J. V. et al. Characterization of ductile phase toughening mechanisms in a hot-rolled tungsten heavy alloy. Acta Mater. 204, 116523 (2021).

Mukhopadhyay, A. & Basu, B. Consolidation–microstructure–property relationships in bulk nanoceramics and ceramic nanocomposites: a review. Int. Mater. Rev. 52, 257–288 (2007).

Humood, M. et al. Influence of graphene reduction and polymer cross-linking on improving the interfacial properties of multilayer thin films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 1107–1118 (2017).

Li, C.-J. et al. The bonding formation during thermal spraying of ceramic coatings: a review. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 31, 780–817 (2022).

Yang, T. et al. Thermal shock resistance and bonding strength of novel-structured thermal barrier coatings with different microstructure. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 31, 1540–1555 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Preparation of defect-free alumina insulation film using layer-by-layer electrohydrodynamic jet deposition for high temperature applications. Ceram. Int. 47, 14498–14505 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Novel approach to tuning the physical properties of organic-inorganic hybrid semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 026405 (2006).

Segawa, H. et al. Exploration of high-hardness/low-melting borate glasses. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 1, 378–387 (2010).

Rosales-Sosa, G. A., Masuno, A., Higo, Y., Watanabe, Y. & Inoue, H. Effect of rare-earth ion size on elasticity and crack initiation in rare-earth aluminate glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 101, 5030–5036 (2018).

Guo, Y., Li, J., Zhang, Y., Feng, S. & Sun, H. High-entropy R2O3-Y2O3-TiO2-ZrO2-Al2O3 glasses with ultrahigh hardness, Young’s modulus, and indentation fracture toughness. Iscience 24 (2021).

Ye, B., Wen, T., Huang, K., Wang, C.-Z. & Chu, Y. First-principles study, fabrication, and characterization of (Hf0. 2Zr0. 2Ta0. 2Nb0. 2Ti0. 2) c high-entropy ceramic. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 102, 4344–4352 (2019).

Castle, E., Csanádi, T., Grasso, S., Dusza, J. & Reece, M. Processing and properties of high-entropy ultra-high temperature carbides. Sci. Rep 8, 8609 (2018).

Qin, Y. et al. A high entropy silicide by reactive spark plasma sintering. J. Adv. Ceram. 8, 148–152 (2019).

Peng, C. et al. Diffusion-controlled alloying of single-phase multi-principal transition metal carbides with high toughness and low thermal diffusivity. Appl. Phys. Lett.114 (2019).

Drdlik, D., Drdlikova, K., Hadraba, H. & Maca, K. Optical, mechanical and fractographic response of transparent alumina ceramics on erbium doping. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 37, 4265–4270 (2017).

Zhang, F., Li, L.-f & Wang, E.-z Effect of micro-alumina content on mechanical properties of al2o3/3y-tzp composites. Ceram. Int. 41, 12417–12425 (2015).

Zhang, X., Liang, S., Li, H. & Yang, J. Mechanical and optical properties of transparent alumina obtained by rapid vacuum sintering. Ceram. Int. 43, 420–426 (2017).

Bocanegra-Bernal, M. et al. Spark plasma sintering of multi-, single/double-and single-walled carbon nanotube-reinforced alumina composites: is it justifiable the effort to reinforce them? Ceram. Int. 42, 2054–2062 (2016).

Zhao, G., Huang, C., He, N., Liu, H. & Zou, B. Microstructure and mechanical properties at room and elevated temperatures of reactively hot pressed tib2–tic–sic composite ceramic tool materials. Ceram. Int. 42, 5353–5361 (2016).

Nie, X. & Lu, Q. Fracture toughness of ZrO2–SiC/MoSi2 composite ceramics prepared by powder metallurgy. Ceram. Int. 47, 19700–19708 (2021).

Tong, Y. et al. Microstructure and mechanical behavior of carbon fiber reinforced carbon, silicon carbide, and copper alloy hybrid composite fabricated by cu-si alloy melt infiltration. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 25 (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. Toughening mechanisms of Ti3SiC2-and Tib2-toughened sic matrix prepared via reactive melt infiltration. J. Mater. Res. 36, 1–11 (2021).

Ning, J., Zhang, J., Pan, Y. & Guo, J. Fabrication and mechanical properties of SiO2 matrix composites reinforced by carbon nanotube. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 357, 392–396 (2003).

Porwal, H. et al. Toughened and machinable glass matrix composites reinforced with graphene and graphene-oxide nano platelets. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 14, 055007 (2013).

Liu, L. & Shinozaki, K. Fracture toughness enhancement via sub-micro silver-precipitation in silica glass fabricated by spark plasma sintering. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 105, 1980–1991 (2022).

Kumar, K. et al. Improved mechanical performance and unique toughening mechanisms of udm processed epoxy-SiO2 nanocomposites. Polym. Compos. 42, 6000–6009 (2021).

Nino, A., Sasago, A., Sugiyama, S. & Taimatsu, H. Preparation of Si3N4-TaC and Si3N4-ZrC composite ceramics and their mechanical properties. Int. J. Refract. Hard Met. 37, 1587–1592 (2017).

Yung, D.-L., Cygan, S., Antonov, M., Jaworska, L. & Hussainova, I. Ultra high-pressure spark plasma sintered ZrC–Mo and ZrC-TiC composites. Int. J. Refract Hard. Met. 61, 201–206 (2016).

Liu, H.-L., Liu, J.-X., Liu, H.-T. & Zhang, G.-J. Contour maps of mechanical properties in ternary ZrB2SiCZrC ceramic system. Scr. Mater. 107, 140–144 (2015).

Ren, X. et al. Effect of zrc nano-powder addition on the microstructure and mechanical properties of binderless tungsten carbide fabricated by spark plasma sintering. Int. J. Refract. Hard Met. 48, 398–407 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 523B2055), the National Key Laboratory of Science and Technology on Aero-engine Aero-thermodynamics grant (2022-JCJQ-LB-062-0408).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiangyu Chen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft; Lu Qiu: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing—Review and Editing; Mengsen Zhang: Data Curation, Visualization, Investigation; Jia Huang: Methodology, Validation; Zhi Tao: Resources, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Christopher Tuck and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: John Plummer. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Qiu, L., Zhang, M. et al. Nanoparticle-reinforced SiOC ceramic matrix composite films with structure gradient fabricated by inkjet printing and laser sintering. Commun Mater 5, 96 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00533-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00533-0

This article is cited by

-

Curvature programmed inkjet printing enables adaptive deposition for Gaussian sintering lasers

Nature Communications (2026)