Abstract

The reproducible synthesis of nano- and -micro particles is a critical step in multiple synthetic and industrial processes. Microfluidic synthesis offers numerous advantages for development of precise, reliable, and industrially useful synthesis protocols. However, the influence of different synthetic variables on reproducibility in microfluidic synthesis is underexplored. In this work, we systematically study the influence of key synthetic parameters on the microfluidic synthesis of four Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (ZIFs): ZIF-7, ZIF-8, ZIF-9, and ZIF-67. Utilizing a coiled tube microfluidic setup, we explore the influence of key synthetic parameters such as reagent concentration, stoichiometry, aging time, and nine modulators (pH-altering agents, surfactants, and polar polymers). Most importantly, we evaluate the impact of these variables in combination with the role of mixing, using the Dean flow model. Lastly, we focus on the reproducibility problems that a coiled reactor presents at specific flowrates and how these problems can be recognized and avoided. Overall, the insights collected from this work inform the design of synthetic protocols and enhance material reproducibility and control in microfluidic nano- and micro-particle synthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The overall goal of nanoscience and nanotechnology is to create materials with unique properties for currently unsolved scientific problems, industrial optimizations and societal needs1,2,3. The strength of these materials, lays in the combination of material and size-dependent properties, arising at the micro- and nano-scale. In order to fine tune and optimize the final properties of the obtained particles is crucial to control their size and morphology4,5,6,7,8. This directly relates to the synthetic control we have over the particle synthesis, that is, ultimately, the most direct and reliable control over the final material properties9,10,11,12,13,14. In this regard, continuous flow methods, and in particular microfluidic synthesis, offer various advantages for the synthesis of high-quality nanoparticles15,16,17,18,19. Microfluidic setups allow for precise control of synthetic variables, presenting various advantages over traditional bench-top particle synthesis, such as better temperature control, ease of scale up and automation, affording particles of better quality and available in bulk, resulting in a platform that allows and promotes scalability and versatility in the synthetic methodology. Overall, the high control on experimental variables leads to high reproducibility in microfluidic nanoparticle synthesis20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29.

However, microfluidic setups are not necessarily easy to tune in order to obtain the desired particle properties (e.g. particle size and morphology). In particular, the mixing of the reagents in microfluidic setups represents one of the main challenges. In microscale reactors such as tubes and chip-based channels, the individual precursor solutions tend to form parallel streams, resulting in suboptimal mixing and restricted reagent diffusion from the two solutions, in particular regarding continuous flow devices, as droplet based reactors can count on the development of Taylor flow in each drop.30 However, continuous flow devices present several advantages in terms of practicality and efficiency, as they do not require additional pumps or flow regulators for the second fluid, their setup in simpler and more straightforward, the energy used to heat or cool the apparatus is fully used on the reaction medium, and there is no need to further purify the products by separating the inert media, that can still contaminate or be contaminated by the reagents or products of the reaction, leading to extra steps and further waste of resources30,31,32,33.

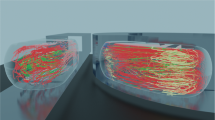

Importantly, while the passive mixing strategies enhance mixing, predicting their effects without intricate and costly fluid dynamic simulations is extremely difficult. Introducing simple circular bends in tube- or chip- based microfluidic reactors (Fig. 1) leads to comparable improvements in mixing, but these effects are much easier to predict and control when analyzed trough the Dean model15,34,35,36,37,38,39,40.

The presence of circular bends leads to the generation of two orthogonally stacked counterrotating vortices aligned with the liquid flow and perpendicular to the channel curvature; this is due to the differential velocity of the fluids, induced by the slight change in microreactor length due to the channel curvature. This principle was first mathematically modelled by physicist William R. Dean38 with a straightforward equation that bears his name: (Eq. 1):

where De: Dean Number, ρ: fluid density, Q: flow rate, µ: dynamic viscosity, d: diameter of the tube, Rc: radius of curvature, and Re: Reynolds Number.

The Dean flow (quantified by the Dean number, De) ensures rapid and enhanced mixing of the precursors and it therefore impacts the physicochemical properties (e.g. size, shape, and morphology) of particles. In a previous work, we investigated multiple coil reactors with different geometries and demonstrated that the De is in fact a better descriptor than flow rate, as setups with different radii of curvature would lead to consistent results, in terms of particle size and size distribution, when using the same De, while maintaining the same flow rate between different setups lead to particles of different dimensions15. By the evaluation and control afforded by the Dean model, this impact can be applied as an effective tool to control the product of microfluidic synthesis.

Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs), a subcategory of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), are an important class of nanoporous materials41. ZIFs are typically composed of soft metal ions coordinatively linked with the nitrogen atoms of imidazolate linkers to form three-dimensional porous structures, resulting in more than a hundred ZIFs reported till date42,43,44,45. ZIF topologies are determined by the substituents on the imidazole ring and, as the name suggests, are topologically equivalent to zeolites, owing to their M-Im-M bridge angle of 145° which resembles the Si-O-Si bridge motif found in zeolites.

ZIFs were chosen for our study for four main reasons: (i) their well-known chemistry that facilitates morphological/compositional controllability; (ii) their particle size and morphology are very sensitive to various reaction conditions (e.g. reagent concentration), making it easier to observe the impact of component mixing; iii) the inexpensive reagents, fast reactions and mild reaction conditions (room temperature, neutral pH) of this material class, makes ZIFs optimal systems for setup testing and reactor benchmark; and iv) ZIFs represent one of the most studied, developed and interesting MOFs subclasses, not only due to their synthesis and properties, but also their wide array of applications44,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53.

Notably, there are several works reported demonstrating synthesis of ZIFs particles via microfluidic method, however, it is important to understand the broader picture regarding the influence of various synthetic variables toward materials properties54,55,56,57,58,59. These differential trends arise mainly due to the intrinsic differences in synthetic conditions such as solvent, temperature, stoichiometry etc. However, most of the reported description of the experimental setup do not include the radius of curvature of the reactor bends or coils, creating a series gap for experimental researchers as this information can play crucial role in dictating the final size, size distribution and morphology of the obtained particles. To this end, in our previous study, we have highlighted the key role of this parameter toward the particle’s formation, which means many of reported studies lack in enough information to be fully reproducible along with the role of this factor in their individual synthetic outcomes.

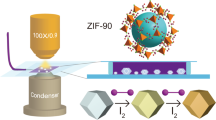

In this work, we systematically chose four ZIFs (ZIF-8, ZIF-67, ZIF-7, and ZIF-9; Fig. 2) representing combinations of two different metals and linkers, thus enabling the assessment of the role of each component in the synthesis outcome. Note-worthy to mention, this work is one of the rarest efforts toward systematic evaluation of the different synthetic and chemical parameters influencing the size, shape and morphologies of diverse ZIF-nanoparticles via microfluidic synthesis. In particular, we examine and highlight the role of several synthetic variables including the concentration and stichometry of the precursors, reaction aging time, various chemical modulators (e.g. pH-altering agents, surfactants, and polar polymers) in combination with the role of Dean Flow mixing strength, and their combined effect in dictating the size, shape and morphologies of ZIF nano- and microparticles (Fig. 1). Last but not least, key issues in microfluidic systems that influence reproducibility are systematically studied and listed to help future researchers address and avoid such issues.

Results and Discussion

The ZIF-platform of this study

We chose two metals (zinc and cobalt) and two imidazole-based linkers (2-methylimidazole, 2MI, and benzimidazole, BM), which are paired to create four different ZIFs (Fig. 2). The metals were selected for their ubiquitous presence in ZIF systems, as combined, these two metals are present in more than 90% of ZIFs. The selection of the organic linkers was more complex; while the linkers should be as different as possible, the reaction conditions between different materials should present common grounds (in particular regarding solvent and temperature), in order to allow us to draw direct comparisons. For this reason, the choice was guided by differences in steric hindrance, polarity and pKof the labile proton, while maintaining good solubility in methanol at room temperature. These combinations allow us to evaluate the impact of the linker and the metal over the synthesis while uniformly exploring other variables.

ZIF-8 and ZIF-67 were synthetized with zinc and cobalt respectively using 2MI as linker, while ZIF-7 and ZIF-9 resulted from the combination of zinc or cobalt with BM as linker. It is important to note that the metal/ligand combinations used to produce ZIF-7 and −9 can also form a different topology (ZIF-11 and ZIF-12)44 which, to the best of our knowledge, cannot be obtained at room temperature and are therefore excluded from this study. Our investigation focused on a single microfluidic setup, a 1.5 m microchannel (750 μm in diameter) coiled around a 4.8 mm mandrel. The use of coiled reactors in microfluidic synthesis can be beneficial for several reasons: (i) they produce the most dramatic dean flow effects; (ii) they can create larger nanoparticles at higher flow-rates; and (iii) their compact form allows for easier scale-up15.

In order to investigate the Dean flow impact over particle synthesis, for each combination of chemical variables, three different flow-rates corresponding to De = 20, 60 and 100 were studied. After the products of each run were filtered and washed twice with methanol, the samples were divided two aliquots that were aged for either 30 min or 24 h in order to assess aging impact.

Preliminary screening of the four reactions, performed with a metal:ligand:solvent ratio of 1:2:1000, showed strong differences in the behaviour of the different materials. ZIF-8 reproduced the previously reported results15, while ZIF-67 quickly fouled and clogged the microreactor (even with weak mixing), highlighting a much faster reactivity of cobalt toward 2MI (Fig. 3 and S6). We were able to collect a fraction of the desired volume of the combined solutions before the reactor clogged, and the particles resulted to be very large, approximately 1.2 μm in diameter at De 20. Stronger mixing increased particle size, leading to a wider size distribution and faster clogging.

For ZIF-7 and ZIF-9, a completely different trend was observed. In both cases, the particles obtained after 30 min of aging were extremely small and amorphous (Figure S3). When aged for 24 h, much larger particles were obtained for both ZIFs, with a craggy morphology and good crystallinity. Interestingly, the surface roughness of the particles aged for 24 h aged suggests they formed via aggregation of smaller particles, while the sharp edges and similar angles suggest a strong influence of the crystal structure during the agglomeration process.

The effects of reagent stoichiometry, concentration, and the Dean flow

The role of reagent stoichiometry proved to be crucial for tuning particle size and modulating the impact of Dean flow. Because of the incompatibility of ZIF-67 synthesis at reagents ratio of 1:2:1000, we employed lower metal to linker ratios: 1:4, 1:8 and 1:12 in order to keep the metal concentration consistent with ZIF-8. To provide a qualitative interpretation of the observed trends and help the reader to interpret reactor behaviour and to apply the Dean model as a tool for better reactor and reaction optimization, we propose the following rationale, based on the general trends observed.

In the case of ZIF-67, the gradual decrease in different ratios led to lower particle sizes (from ≈800 nm for 1:4 to ≈400 nm for 1:12) and sharper size distribution (Fig. 4 and S7). However, the crystallinity at a 1:12 ratio worsened noticeably (Figure S2). Although ZIF-8 showed a similar decrease in particle size, size distribution remained constant (from ≈90 nm to ≈ 600 nm for 1:2 at De 20 and 100 respectively, to constant ≈80 nm for 1:4 and ≈70 nm for 1:8) (Figure S8). Next, we analysed the effect of reagent concentration at each stoichiometric ratio. In this regard, ZIF-8 synthetized with a 1:4 ratio behaves similarly to 1:2 samples, with increased particle size with increasing concentration (Figure S10, S11). It is worth noticing that the effect of De at this stoichiometric ratio seems to depend strongly from reagent concentrations, with a more marked effect at 1:4:500 (from ≈80 nm at De 20 to ≈220 nm at De 100) than 1:4:1000 (constant at ≈80 nm), where almost no effect can be detected. ZIF-67 showed similar behaviour to the 1:8 samples, but with higher irregularities in particle size and size distribution at 1:4 (Fig. 5, S9) and a much lower and more inconsistent impact of De on the synthesis at higher concentrations. The overall difference between ZIF-8 and -67 can be explained by the faster reactivity of cobalt, as hypothesized during the preliminary screening. This difference in reactivity not only affects the synthesis, but also the impact of the De on the reaction. ZIF-8 at 1:4 exhibits a much less prominent Dean flow effect at high concentrations, which becomes negligible at 1:4. This behaviour can be rationalized considering that the nucleation and growth behaviour of the particles following the LaMer model. While reagents are depleted during the reaction, the concentration of the excess one does not drop as sharply, thus extending the time of particle nucleation. As more particles are nucleated, the growth rate diminishes as the limiting reagent (zinc) concentration is already much lower and a larger number of particles are growing at the same time. However, ZIF-67 was found to exhibit the opposite behaviour at 1:8:1000: particle size decreased (from ≈540 nm at De 20 to ≈370 nm at De 100) with the increasing De (thus with stronger mixing), while at higher concentrations (1:8:500), the size increases slightly at higher De values (from ≈580 nm at De 20 to ≈630 nm at De 100).

This behaviour is in apparent contradiction with the observations for ZIF-8, but this discrepancy can be explained by considering the faster reaction rate: in faster reactions, reagent diffusion (which is almost exclusively controlled by the mixing) is more important. At low concentrations and De (slow diffusion) the cobalt reacts before it can completely mix with the linker. This limits particles nucleation as the reagent concentration at the solution interface will be decreased compared to the nucleation threshold of the particles, and thus the one that have been nucleated in the first portion of the reactor will further grow. By increasing mixing, this threshold moves in favour of the linker, allowing more efficient nucleation at high De and resulting in smaller particles as more nuclei will compete for the same resources. At higher concentrations or with closer to stoichiometric (1:2) reagent ratios, this effect will not affect the reaction because reagent concentration will always sustain fast nucleation and growth of the particles (up to reactor fouling).

For ZIF-7 and -9, the lower ratios were found to exhibit no change in the behaviour, confirming slow reactivity which cannot be influenced by the mixing behaviour of the microfluidic setup. However, this does not mean that the process is not important for these materials, as it befits in terms of scalability, reproducibility and automatization still apply.

Role of the aging time

Particle aging is, to some extent, a forced step for common microfluidic setups, as the combined solutions exiting the microreactor need to be collected and the particles separated and washed in batches. This presents a challenge in terms of uniformity if the needed aging time is very little. Results will not be uniform if the delay between collection of the first and last particles is comparable or larger than the aging time of the solution. To minimize this difference, we chose to use batches of 5 ml of reaction mixture and wait for at least 30 min prior filtration and washing of the particles, while maintaining the suspension under stirring to avoid sedimentation and clumping of the solids. Longer aging times are straightforward to implement and control. Interestingly, ZIF-8 and ZIF-67 exhibit similar behaviour during aging: the particle size and size distribution remain constant, while the particle morphology changes slightly. Particles aged for 30 min present a truncated rhomb dodecahedron morphology, presenting square faces instead of sharp vertexes, while particles aged for 24 h are perfect rhomb dodecahedrons, with sharper edges, to the point of slightly concave faces. On the other hand, ZIF-7 and ZIF-9 were obtained as very small, non-crystalline particles after 30 min of aging. The particles coalesce over time to form much larger solids (Fig. 6). The final particles present similar morphologies for the two materials, although much less regular and defined than ZIF-8 and ZIF-67. The particles are discoids of variating thickness, with craggy edges that seem to follow crystalline planes in their sharp but seemingly random edges. Moreover, many of particles are composed of multiple discoids protruding from each other following crystal planes to form complex shapes, some resembling desert roses. Further, we followed the particles aggregation process by taking a sample of the same reaction mixture after the standard 30 min and 24 h, and at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 h (Fig. 6). Again, this showed a difference in kinetics between zinc and cobalt: ZIF-7 formed the first aggregates at 4 h and was fully coalesced by 6 h, while ZIF-9 formed aggregates already at 1 h and was fully aggregate at 2 h.

The influence of modulators

Modulators are chemical species, usually small molecules (charged or neutral), or polymers, that influence the nucleation and growth of MOF particles but are not a constituent of the final product. Modulators can alter the synthesis outcomes in three main ways: (i) by altering the reactivity of the linker and/or the metal precursor - for example by facilitating the deprotonation of the linker and thus promoting framework reticulation, or by complexing with the metal center and slowing the nucleation and growth of the material; (ii) by establishing an equilibrium between the framework material and the soluble species to reduce the nucleation and growth rate of the material and allowing the correction of defects during reticulation, which improves the crystallinity of the final product; and (iii) by interacting with the material surfaces after nucleation, thus reducing the material’s growth rate. As modulators can potentially influence the reaction from multiple aspects, their effect is not trivial to study and predict, with most studies relying on a trial-and-error iterative procedure to optimize material synthesis.

From the ZIF chemistry perspective, modulators are extremely important in bench-top synthesis for optimizing particle size, size distribution, and final morphology, but their role in microfluidic synthesis is still largely unexplored. To address this knowledge gap, some of the most common bench-top modulators were selected to determine and understand their impact on ZIFs formation. Depending on their chemical features and theoretical influence over the synthesis, the modulators can be classified into three categories: (i) pH altering, (ii) surfactants, and (iii) polar polymers (Fig. 7).

For details see Table S2.

Modulators altering the pH

ZIFs synthesis are fairly sensitive to pH, and both ZIF-8 and ZIF-67 must be synthesized under neutral or slightly basic conditions; acidic or strongly basic conditions hinder ZIF formation. Hence, three weak bases were selected as pH modulators: triethylamine (TEA), sodium acetate (SA) and sodium benzoate (SB) to study their effects (Fig. 7). As expected, TEA (being the strongest base) found to have the strongest effect on the particle size, reducing it to much smaller dimensions for both ZIF-8 and ZIF-67 at any De (from ≈30 to ≈70 nm, Fig. 8 and Figure S13). Moreover, TEA strongly reduced the Dean flow influence over the particle size for ZIF-8 and completely suppressed it for ZIF-67 (Figures S13 and S14). This is to be expected, as higher pH conditions lead to faster nucleation and thus lower the impact of mixing. Surprisingly, both SA and SB found to exhibit opposite effects for ZIF-8, leading to much higher enlargement of the particles (Fig. 8 and S13). This behaviour can be attributed to the lower impact of the pH toward two metal salts. The carboxylate groups of both modulators can interact with zinc ions, thus slowing the reaction at low De. Both SA and SB did not show any significant effects on the synthesis of ZIF-67, thus confirming that the effect was not due to the influence of the linker deprotonation from the pH variations, but rather to their interactions with the metal salt.

Surfactants

Surfactants are commonly used in ZIF synthesis in order to modulate particle size and morphology of the materials60,61. These kinds of modulators primarily function via selectively adsorbing on certain crystal faces, thus inhibiting their growth. For this reason, the overall modulating effect can be expected to depend strongly on the type of surfactant, the extent of adsorptive binding and on which faces. The effects of surfactants can significantly slow down the reactions, spanning multiple days of heating and stirring. As the representative molecules for this class, we chose cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) and sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) for this study.

Considering the microfluidic synthesis is inherently faster than bench-top, it is surprising that ZIF-8 was found to be influenced by the presence of both modulators, although their effect on the obtained particles was opposite. The presence of CTAB found to result in enhanced Dean flow effect with larger particles at higher De ( ≈ 80 nm at De 20, ≈500 nm at De 60 and ≈1000 nm at De 100) along with a smoother and less sharp morphology (Fig. 9 and S15). SDS, on the contrary, led to a less consistent Dean flow effect, with larger particles at De 60 and smaller ones at De 100 than the unmodulated reaction. However, the difference is not as prominent as with CTAB (Fig. 9 and S15). Moreover, the modulation via surfactants found to be highly influenced by the type of metal centre as suggested by the outcome of the ZIF-67 particles (Figure S16). It this case, neither molecules did influence the overall size or morphology of the particles in an appreciable way, but led to a broader size distribution of the obtained particles.

Modulator retention can be a problem for future applications of the nanoparticles, as it can influence their physicochemical behaviour and colloidal stability. To investigate the problem, we chose to focus on the retention of the two surfactants tested, as with their hydrocarbon tails are strongly retained on the hydrophobic pores and surfaces of ZIFs. The washing protocol we used for all reactions (three washes with fresh methanol on the syringe filtered particles before redispersion) successfully washed away both CTAB and SDS from the particles, as attested by FTIR spectrometry (Figure S5).

Polar polymers

Apart from bases and surfactants, we envision to explore the modulating effects of polymeric modulators equipped with terminal reactive groups toward the nucleation and growth of ZIF particles. Their working process is similar to surfactants, as they get adsorbed on the material surfaces and limit their growth. In particular, we evaluated the effect of polyethylene glycol (PEG) as this polymer is widely utilized, cheap, biocompatible and can be achieved with a wide variety of molecular weights62,63. Moreover, we envision to focus on the modulating effect originating from the variation in molecular weight of PEGs via testing the same amount of unpolymerized ethylene glycol (EG) and three different PEG variants, in particular polymeric chains of 400, 1500 and 6000 units.

Interestingly, variation in molecular weight of same polymer found to have strong influence on the synthesis of ZIF-8 particles. In particular, utilization of EG and PEG lead to formation of larger particles with respect of the unmodulated reaction at high De, with softer morphology(Fig. 10 and S17). On the other hand, PEG induced a molecular weight-dependent reduction in particle size at high De: PEG400 which showed almost no effect over the unmodulated reaction (Fig. 10). While PEG6000 led to a strong reduction in particle size, in particular at De 100 with particles smaller than the unmodulated reaction, PEG1500 found to result in consistent trend with intermediate particles (Fig. 10 and S17). This trend can be well explained by the stronger interactions of longer polymers with the material surfaces, as longer and bulkier chains have slower desorption kinetics and provide better coverage to the particle they attach to. Once again, the reaction itself plays a central role in the modulator effect, as ZIF-67 particles synthetized with the conditions tested show little to no change with and without PEG, independent of chain length.

Modulator impact at different stoichiometries

All the data reported so far regards the two stoichiometries that show the stronger influence of the Dean flow during synthesis, with a metal to ligand ratio of 1:2 for ZIF-8 and 1:8 for ZIF-67. When investigating the impact of modulators on the ZIF synthesis at different stoichiometries, the results, as expected, show a reduced impact of the De over the synthesis, and an overall lower impact of the modulators. More specifically, we repeated the experiments presented in the previous section at 1:4:1000 for both ZIF-8 and ZIF-67 (figures S19 to S4). TEA was again the modulator with the highest impact by far, yielding much smaller particles than the unmodulated reaction for both ZIF-8 and 67 (Figure S19 and S20). A notable exception to the overall low impact of the other modulators at this stoichiometry, CTAB proved to change slightly the formation of ZIF-67, with a noticeable increase in the size of the obtained particles, scaling with the reaction De (Figure S22). Lastly, it is remarkable the similarity on effect of PEG-400 and PEG-6000 on ZIF-8 synthesis at this ratio: while at 1:2 the two led to particles that differed strongly in size and sharpness at high Des, at 1:4 the two molecular weights lead to extremely similar particles, indicating a strong influence of the chain length over the synthesis only if a strong effect of the Dean flow is already present (Figure S23).

Reproducibility limits of Dean Flow mixing

As discussed before, the mixing strength in the microreactor can strongly influence the reaction and the final products. In case of the Dean flow, an increase in strength and efficiency of the mixing is not linear, but it can be divided in three distinct phases: No vortexes formation for De from 0 to ≈40, for which the behaviour of the reactor is relatively same and a slight increase in turbulence at the increase of De can occur. Once the De is 60 or higher, the Dean vortexes are fully formed and the mixing is strongly enhanced, with a further increase at higher De. In between these two stable conditions we have a region at which the Dean vortexes are forming in an unstable way.

In Fig. 11, we report sets of five different reaction runs, performed at exactly the same conditions (1:2:500 and 1:2:1000) at De = 50. It is appreciable how the results vary, independently from the concentration of the precursors. The five samples synthetized at 1:2:500 and De 50 present size means between 420 and 690 nm, with an overall 0.5 deviation to size ratio (Figure S25). When compared to the same group of experiments conducted at De = 20 (that fall in between 100 and 150 nm and present a deviation to size ratio of 0.3) we can appreciate how strong this variation between experiments is. De = 100 presents a very similar picture, with sizes comprised between 690 and 910 nm, with a deviation to size ratio of 0.25. Furthermore, if we consider not all the particles obtained at De 100, but we remove the smaller, starved particles (that represent a small fraction of the sample) from the size distribution, we find median sizes comprised between 920 and 950 nm, with a ratio lower than 0.1. The same trends can be found at lower concentrations with even higher discrepancies, with deviation to size ratios of 0.4, 1.2 and 0.1 at De 20, 50 and 100 respectively (Figure S26).

ZIF-67 suffers the same problem, although the variation results lower, as the De influences less the particle size (with a difference of ≈350 nm between smallest to largest and a deviation to size ratio of 0.4). All in all, it can be concluded that there is no batch-to-batch reproducibility.

This seemingly random phenomenon can be explained by an “on-off” behaviour of the vortexes: by any reason (e.g. fluctuation in temperature, vibrations, impurities in the stream etc.), if the vortexes form, the result will be similar to the product of a reaction conducted at De 60 or even larger. But, in the case where the vortexes do not form, the resulted particles will be significantly smaller in size. This is one of the most important aspect to be careful of while using the Dean model. It is also worth noticing that the interval of De in which this behaviour occurs, can also vary in span and position, depending on the shape and area of the channel cross section as the reactor geometry and curved sections are intercalated by straight ones. To the best of our knowledge it appears between De 35 and 60 and can last up to 10 De, with earlier onsets in setups with larger cross sections64,65. At a more fundamental level, adequate knowledge and precise monitoring of this “grey zone” of reproducibility in a simple microfluidic setup (e.g. coiled tube) is highly important. Otherwise, the operator can accidentally set up an experiment with inconsistent outcome. If this irregularity is discovered, its addressing may still take a long time of troubleshooting, as the combination of radius of curvature and flowrate is not an immediate variable to control. If, on the contrary, this inconsistency is not caught, the issue will propagate to the next research steps.

Conclusions

In this work, we have explored the microfluidic synthesis of four ZIF systems and the potential influence of the reagent concentrations and stoichiometry, reaction aging time, diverse chemical modulators (pH-altering agents, surfactants, and polar polymers) on particle size, size distribution and morphology. In particular, the role of Dean flow mixing and it´s combined effect with these synthetic variables have been carefully studied. In this regard, all the variables found to impact the obtained ZIF-8 and -67 particles, while ZIF-7 and −9 particles followed a very different growth leading to homogeneous results at almost for all conditions except aging time. The reagent concentration found to have direct proportionality with particle size, irrespective of stoichiometry and mixing, while De retained its strong influence over ZIF-8 particle size. Variation in stoichiometry found to yield in smaller particles at ratios further from the stoichiometric one, but the influence of the De seemed to strongly vary depending on the ratio and the material. Alteration in aging of the ZIF-8 and -67 particles showed a slight change in morphology, while ZIF-7 and ZIF-9 could be obtained as crystalline materials only after a substantial amount of time (6 and 2 hours respectively). In addition, the role of nine different modulators has been investigated. Amongst the pH altering modulators, TEA influenced strongly both ZIF-8 and ZIF-67 synthesis, resulting in much smaller particles. On the other hand, different surfactants and polymers showed mixed influences on the particle synthesis. In particular, modulators influencing and directing the particle growth by adsorbing on the particle surfaces impacted the synthesis of ZIF-8 in different ways, with both increasing and diminishing of the particle’s dimensions and of the role of mixing. Overall, modulators are an important tool to fine tune particle size and size distribution in microfluidic synthesis, providing a further layer of control over the synthesis.

Finally, the reproducibility limits of Dean flow mixing have been fully characterized. For materials strongly influenced by the Dean flow mixing, at De 50, the presence or absence of the Dean vortexes in the microreactor can lead to different particle size and quality. We have identified that control over the microfluidics setup as the key aspect for reproducibility: with a reliable and controllable setup, the microfluidic is a wonderful and extremely repeatable tool. However, without precise control, for example, not accounting the reactor mixing or, as in this case, for a non-predictable behaviour of the mixing at very specific conditions, the synthetic reproducibility might suffer.

We trust this work will help researchers interested in microfluidic synthesis of nano- and micro- particles or the development of reticular materials to better understand the challenges, pitfalls and great rewards that these two fields can bring to their studies, helping in the development of next-generation materials and fruitful synthetic methodologies.

Methodology

Synthesis of ZIF-materials

All the ZIF materials have been synthesized via following previously reported protocols with slight modifications44,45.

For the synthesis of each ZIF material, the total amount of solvent was divided into two to prepare the metal-solution and the ligand solution. Further, both the solutions were introduced to the reactor via pumping with two syringes (20 mL each) and the reactor geometry was specified for each reaction. All experiments were conducted by mixing of equal volumes of methanol solutions, with the reported flowrate obtained by setting each syringe pump to half the desired value. Importantly, the effective residence time was controlled by controlling the flowrates of the solutions. Further, liquid samples were collected while leaving out of the microfluidic reactor and collected in separate vials. All the collected samples were allowed to age for 30 min and/or 24 h under stirring (200 rpm) to complete the ZIF formation reactions. The as-synthesized white/purple crystalline solids were collected and segregated via filtration. All the solids were further thoroughly dispersed, washed, and stored in MeOH. All the synthesis and the purification steps were carried out at room temperature (21 + /- 2 °C). Modulators were used in a fixed molar ratio (1:2:1000:0.1 Metal:Linker:Methanol:Modulator) and dissolved directly in the linker solutions, that were then used as normal. Linker solutions were chosen over metal ones as different modulators may impact differently metal salts solubility and not all combinations tested were compatible with the ratios used, while the linker/modulator ones proved to be. Any further specific experimental parameters are mentioned in the subsequent sections.

ZIF-8: ZIF-8 was synthesized with the reagent combination of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (Zn) and 2-methylimidazole (2MI). Experiments were conducted at different concentrations and stoichiometric ratios of (Zn:2MI:MeOH)- 1:2:500; 1:2:750, 1:2:1000, 1:4:500; 1:4:750, 1:4:1000 and 1:8:1000.

ZIF-67: ZIF-67 was synthesized with the reagent combination of Co(NO3)2·6H2O (Co) and 2-methylimidazole (2MI). Experiments were conducted at concentrations and stoichiometric ratios of (Co:2MI:MeOH)- 1:2:1000, 1:4:500; 1:4:750, 1:4:1000, 1:8:500; 1:8:750, 1:8:1000 and 1:12:1000.

ZIF-7: ZIF-7 was synthesized with the reagent combination of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (Zn) and 1H-Benzo[d]imidazole (1HBI). Experiments were conducted at concentrations and stoichiometric ratios of (Zn:1HBI:MeOH)- 1:2:500; 1:2:750, 1:2:1000, 1:4:500; 1:4:750, and 1:4:1000.

ZIF-9: ZIF-9 was synthesized with the reagent combination of Co(NO3)2·6H2O (Co) and 1H-Benzo[d]imidazole (1HBI). Experiments were conducted at concentrations and stoichiometric ratios of (Co:1HBI:MeOH)- 1:2:1000, 1:4:500; 1:4:750, 1:4:1000, 1:8:500; 1:8:750, and 1:8:1000.

Data availability

All data supporting the study are available in the supplementary material of this article. Any further information is available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Li, Z., Barnes, J. C., Bosoy, A., Stoddart, J. F. & Zink, J. I. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 2590–2605 (2012).

Khandare, J., Calderón, M., Dagia, N. M. & Haag, R. Multifunctional dendritic polymers in nanomedicine: opportunities and challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 2824–2848 (2012).

Andreo, J. et al. Reticular nanoscience: bottom-up assembly nanotechnology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 7531–7550 (2022).

Ploetz, E., Engelke, H., Lächelt, U. & Wuttke, S. The chemistry of reticular framework nanoparticles: MOF, ZIF, and COF materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1909062 (2020).

Wang, A. et al. Adv. Funct. Mater.2023, 2308589.

Long, J. R. & Yaghi, O. M. Chem. Soc. Rev., 2009, 38, 1213–1214.

Baig, N., Kammakakam, I. & Falath, W. Nanomaterials: a review of synthesis methods, properties, recent progress, and challenges. Mater. Adv. 2, 1821–1871 (2021).

Kuppler, R. J. et al. Potential applications of metal-organic frameworks, Coord. Chem. Rev. 253, 3042–3066 (2009).

Goesmann, H. & Feldmann, C. Nanoparticulate functional materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 1362–1395 (2010).

Pelaz, B. et al. Diverse applications of nanomedicine. ACS Nano 11, 2313–2381 (2017).

Verma, A. & Stellacci, F. Effect of surface properties on nanoparticle-cell interactions. small 6, 12–21 (2010).

Modena, M. M., Rühle, B., Burg, T. P. & Wuttke, S. Nanoparticle characterization: what to measure. Adv. Mater. 31, 1901556 (2019).

Lu, Q., Yu, H., Zhao, T., Zhu, G. & Li, X. Nanoparticles with transformable physicochemical properties for overcoming biological barriers. Nanoscale 15, 13202–13223 (2023).

Xu, M. et al. How Entanglement of Different Physicochemical Properties Complicates the Prediction of in Vitro and in Vivo Interactions of Gold Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 12, 10104–10113 (2018).

Yu, X. et al. Small Methods 2023, 2300603.

Hou, X. et al. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 1.

Whitesides, G. M. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature 442, 368–373 (2006).

Bhatia, S. N. & Ingber, D. E. Microfluidic organs-on-chips. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 760–772 (2014).

Convery, N. & Gadegaard, N. 30 years of microfluidics. Micro Nano Eng. 2, 76–91 (2019).

Thiele, M. et al. Gold nanocubes – Direct comparison of synthesis approaches reveals the need for a microfluidic synthesis setup for a high reproducibility. Chem. Eng. J. 288, 432–440 (2016).

Kang, H. W., Leem, J., Yoon, S. Y. & Sung, H. Jin Continuous synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles in a microfluidic system for photovoltaic application. Nanoscale 6, 2840–2846 (2014).

Volk, A. A., Epps, R. W. & Abolhasani, M. Accelerated development of colloidal nanomaterials enabled by modular microfluidic reactors: toward autonomous Robotic Experimentation. Adv. Mater. 33, 2004495 (2021).

Valencia, P. M. et al. Single-step assembly of homogenous lipid-polymeric and lipid-quantum dot nanoparticles enabled by microfluidic rapid mixing. ACS Nano 4, 1671–1679 (2010).

Kurt, S. K., Gelhausen, M. G. & Kockmann, N. Axial dispersion and heat transfer in a milli/microstructured coiled flow inverter for narrow residence time distribution at laminar flow. Chem. Eng. Technol. 38, 1122–1130 (2015).

Singh, J., Kockmann, N. & Nigam, K. D. P. Chem. Eng. Process 86, 78–89 (2014).

Habibey, R., Arias, J. E. Rojo, Striebel, J. & Busskamp, V. Microfluidics for Neuronal Cell and Circuit Engineering. Chem. Rev. 122, 14842–14880 (2022).

Hohmann, L. et al. Analysis of Crystal Size Dispersion Effects in a Continuous Coiled Tubular Crystallizer: Experiments and Modeling. Cryst. Growth Des. 18, 1459–1473 (2018).

Pitsalidis, C. et al. Organic Bioelectronics for In Vitro Systems. Chem. Rev. 122, 4700–4790 (2022).

Sart, S., Ronteix, G., Jain, S., Amselem, G. & Baroud, C. N. Cell Culture in Microfluidic Droplets. Chem. Rev. 122, 7061–7096 (2022).

Z. Li, et al. Sens. Actuators, A 2022, 344, 113757.

Lv, M. et al. Heteroaromatic organic compound with conjugated multi-carbonyl as cathode material for rechargeable lithium batteries. Sci. Rep. 6, 23515 (2016).

Zhang, K. et al. An efficient micromixer actuated by induced-charge electroosmosis using asymmetrical floating electrodes. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 22, 130 (2018).

Chen, K., Lu, H., Sun, M., Zhu, L. & Cui, Y. Mixing enhancement of a novel C-SAR microfluidic mixer. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 132, 338–345 (2018).

Li, Y., Liu, C., Feng, X., Xu, Y. & Liu, B.-F. Ultrafast microfluidic mixer for tracking the early folding kinetics of human telomere G-quadruplex. Anal. Chem. 86, 4333–4339 (2014).

Hong, S. O. et al. Gear-shaped micromixer for synthesis of silica particles utilizing inertio-elastic flow instability. Lab Chip 21, 513–520 (2021).

Cao, X., Zhou, B., Yu, C. & Liu, X. Chem. Eng. Process. 159, 108246 (2021).

R. Milotin, D. Lelea, Proc. Technol. 2016, 22, 243.

W. R. Dean, J. M. Hurst, Mathematika 1959, 6, 77.

Pinho, B., Williams, L. M., Mahin, J., Gao, Y. & Torrente-Murciano, L. Enhancing mixing efficiency in curved channels: A 3D study of bi-phasic Dean-Taylor flow with high spatial and temporal resolution. Chem. Eng. J. 471, 144342 (2023). 144342.

J. Mahin, L. Torrente-Murciano, Chem. Eng. J., 2020, 396, 125299.

Freund, R. et al. 25 Years of Reticular Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 23946–23974 (2021).

Polyzoidis, A., Altenburg, T., Schwarzer, M., Loebbecke, S. & Kaskel, S. Continuous microreactor synthesis of ZIF-8 with high space–time-yield and tunable particle size. Chem. Eng. J. 283, 971–977 (2016).

Munn, A. S., Dunne, P. W., Tang, S. V. Y. & Lester, E. H. Large-scale continuous hydrothermal production and activation of ZIF-8. Chem. Commun. 51, 12811–12814 (2015).

Zheng, Z., Rong, Z., Nguyen, H. L. & Yaghi, O. M. Inorg. Chem. 62, 20861–20873 (2023). 51.

Jadhav, H. S., Bandal, H. A., Ramakrishna, S. & Kim, H. Critical Review, Recent Updates on Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework‐67 (ZIF‐67) and Its Derivatives for Electrochemical Water Splitting. Adv. Mater. 34, 2107072 (2022).

Widmer, R. N. et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 9330–9337 (2019). 23.

García-Palacín, M. et al. Sized-Controlled ZIF-8 Nanoparticle Synthesis from Recycled Mother Liquors: Environmental Impact Assessment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8, 2973–2980 (2020).

Lee, Y.-R. et al. ZIF-8: A comparison of synthesis methods. Chem. Eng. J. 271, 276–280 (2015).

Pan, Y., Liu, Y., Zeng, G., Zhao, L. & Lai, Z. Rapid synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) nanocrystals in an aqueous system. Chem. Commun. 47, 2071–2073 (2011).

Bux, H. et al. Zeolitic imidazolate framework membrane with molecular sieving properties by microwave-assisted solvothermal synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 16000–16001 (2009).

Phan, A. et al. Synthesis, structure, and carbon dioxide capture properties of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res. 43, 58–67 (2010).

Öztürk, Z., Filez, M. & Weckhuysen, B. M. Decoding nucleation and growth of zeolitic imidazolate framework thin films with atomic force microscopy and vibrational spectroscopy. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 10915–10924 (2017).

Wang, S. et al. Recent advances in tailoring zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs) and their derived materials based on hard template strategy for multifunctional applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 498, 215464 (2024).

Lee, Y. R. et al. J. Chem. Eng. 271, 276–280 (2015).

Yamamoto, D. et al. J. Chem. Eng. 227, 145–150 (2013).

Kevat, S. & Lad, V. N. Microfluidics-facilitated spontaneous synthesis of ZIF-67 metal–organic framework. Chem. Pap. 77, 6351–6363 (2023).

Kolmykov, O. et al. Microfluidic reactors for the size-controlled synthesis of ZIF-8 crystals in aqueous phase. Mater. Des. 122, 31–41 (2017).

Carraro, F. et al. Continuous‐flow synthesis of ZIF‐8 biocomposites with tunable particle size. Angew. Chem. 132, 8200–8204 (2020).

Polyzoidis, A., Altenburg, T., Schwarzer, M., Loebbecke, S. & Kaskel, S. J. Chem. Eng. 283, 971–977 (2016).

Fan, X. et al. Highly porous ZIF-8 nanocrystals prepared by a surfactant mediated method in aqueous solution with enhanced adsorption kinetics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 14994–14999 (2014).

Zhao, J., Liu, X., Wu, Y., Li, D.-S. & Zhang, Q. Surfactants as promising media in the field of metal-organic frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 391, 30–43 (2019).

Chen, J., Spear, S. K., Huddleston, J. G. & Rogers, R. D. Polyethylene glycol and solutions of polyethylene glycol as green reaction media. Green. Chem. 7, 64–82 (2005).

Shi, L. et al. Effects of polyethylene glycol on the surface of nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery. Nanoscale 13, 10748–10764 (2021).

Taylor, G. I. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A, 1929, 124 243–249.

Ligrani, P. M., Choi, S., Schallert, A. R. & Skogerboe, P. Effects of Dean vortex pairs on surface heat transfer in curved channel flow. Int. J. Heat. Mass Transf. 39, 27–37 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Spanish State Research Agency (AEI) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERFD) through the project PID2020–15935RB-C42. The European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and Innovation programmes is also acknowledged for the funding of the LC-SC3-RES-25-2020 4AirCRAFT (Ref.: 101022633) project. In addition, 4AirCRAFT project was also supported by Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) and Mission Innovation Challenge was supported by the Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP). X.Y. (CSC No.202108390001) acknowledges financial support from China Scholarship Council (CSC). J.A. and S.D. thank the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación and the European Union-Next GenerationEU for Juan de la Cierva Formación Scholarship (FJC2021-048154-I and JDC2022-049611-I).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A. and S.W. have conceived the idea of this work. X.Y. has carried out all the microfluidic experiments and physical characterizations. X.Y., S.D. and J.A. have analysed all data. S.D., J.A. and S.W. have written the original manuscript. J.A. and S.W. have supervised the whole work. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available. Primary Handling Editors: Jack Evans and Jet-Sing Lee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, X., Dutta, S., Andreo, J. et al. Identifying synthetic variables influencing the reproducible microfluidic synthesis of ZIF nano- and micro-particles. Commun Mater 5, 210 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00644-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00644-8