Abstract

Achieving near-zero-wear remains a major challenge in mechanical engineering and material science. Current ultra-low wear materials are typically developed based on the self-consumption strategy. Here, we demonstrate a new self-repairing approach to achieve near-zero-wear. We find that the WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair has a low wear rate of 10−8 mm3 N−1 m−1 in low vacuum conditions, under a maximum Hertzian contact stress of 2.23 GPa over 1 × 105 friction cycles. Additionally, we observe an abnormal wear phenomenon after 5 × 104 friction cycles, characterized by an increase in the dimensions of the tribo-pair. This near-zero-wear mechanism is attributed to the synergistic action of the super-hard WB4-βB substrate and the self-repairing tribo-oxide layer. This research provides a new approach for advancing wear-resistant materials and enhancing material longevity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wear is a ubiquitous phenomenon that is considered to be the removal of surface material due to the mechanical, chemical, and thermal interactions between mating surfaces during friction1,2,3,4,5,6. According to scientific statistics, wear causes about 60% of equipment damage or failure. Wear failure in mechanical parts typically shows up as a reduction in the tribo-pair dimension, which immediately impacts accuracy, reliability, and service life4,5,6,7,8. Therefore, the question of achieving near-zero wear tribo-pairs in mechanical engineering and material science remains perennial.

There have been only a handful of materials with ultra-low wear rates until now, and the mechanisms and methods for achieving ultra-low wear are not uniform. For example, classification by wear mechanism, diamond9 with super-hardness can inhibit abrasive wear; the layered materials like graphene4,10,11, a-C:H12, MoS213,14, and MXenes/MoS2 nanocomposites15 have ordered layered structures with low shear strength and consequently reduce surface adhesive wear; the Pt-Au film with a very stable nanocrystalline structure16 can mitigate the evolution of frictional subsurface microstructure and ultimately prevent the occurrence of fatigue wear; in polymer matrix composites with ultra-wear-resistant performance mechanisms include molecular lubrication films produced by alumina-promoted friction chemistry of PTFE and composite friction films consisting of PTFE/2D layered material17,18,19. From these, it can be roughly concluded that there is ultra-stable microstructure (super-hard phase, stable nanocrystals, passivated surface)20,21 or a layered tribo-film with low shear strength (graphite film, MXenes film)7, which is conducive to reducing material wear. Although some material systems exhibit ultra-low wear through slow self-consumption under specific conditions, theoretical wear is inevitable. In contrast, self-repairing strategies can overcome this theoretical limitation.

The combination of polymer matrix composites, alongside the molecular lubrication film generated through the alumina-facilitated tribo-chemical reaction of PTFE, as well as the composite friction film comprising PTFE and two-dimensional layered materials, contributes significantly to the superior wear-resistant characteristics of the materials.

To achieve near-zero wear, we propose a new approach by self-repairing tribo-pair. Self-repairing tribo-pair means that in certain tribo-elements (tribo-pair, load, speed, environment, atmosphere, temperature, etc.) and without additional material flow and energy flow, the friction-driven self-adjustment of the composition and structure of the worn surface can repair its wear22,23,24,25,26. To achieve near-zero wear, the target material must have two necessary characteristics. First, the material has excellent structural stability to resist subsurface lattice dislocation and/or initiation and propagation of cracks driven by friction force5,27. Second, it has a self-repairing function, restoring worn surfaces or compensating for wear loss through chemical or physical action.

Super-hard materials with high bulk modulus help restrain surface damage and prohibit deformation28, which can be divided into two categories: super-hard materials with short covalent bonding of light elements (B, C, N or/and O) and new super-hard materials with high valence electron density (W, Re, Os, etc.)29,30. Among them, WB4 is a typical transition metal boride, consisting of a three-dimensional network structure composed of short B–B covalent bonds with high shear modulus and transition metal W element with high valence electron density with incompressibility28,29,31. The theoretical value of the Vickers hardness of WB4 is 41.1–42.1 GPa, and the Vickers hardness value of WB4 synthesized experimentally is currently 43.3–46.1 GPa30,31,32,33,34. Crystalline boron exhibits a remarkable hardness and at the same time reacts easily with friction to produce lubricating B2O3 and H3BO328,35,36,37,38. Therefore, we designed the WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair: the WB4 super-hard phase carries the normal friction force to resist the deformation of the worn surface; the B phase generates a B2O3 oxide layer through tribo-chemical reaction, which plays the role of friction-reduction, anti-wear and repairing the worn surface39,40,41.

This paper proposes a new strategy to realize near-zero-wear tribo-pair by super-hard WB4 bulk material and self-repairing tribo-chemical layer. The constructed WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair exhibited the dimension variation of ±10−8 mm3 N−1 m−1 with the expression of wear rate during 1.25 × 104–1 × 105 friction cycles, and we found a new self-repairing wear effect of the sliding interface by tribo-chemistry. This work provides a novel path for wear-less research and material protection.

Results and discussion

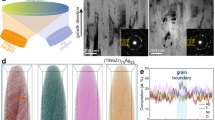

Microstructure and mechanical properties

The sample with a B/W ratio of 9 is synthesized by the spark plasma sintering (SPS) method. As shown in Fig. S1, the experimental sample has the appearance of a 25 mm diameter bulk material with a metallic luster. The XRD spectrum (Fig. 1a) shows the peaks of WB4, which are consistent with the standard diffraction peak of the PDF (Ref. code 00-019-1373), and there are no impurity peaks33,42. Figure 1b shows the presence of two regions on the surface of the sample, a boron-enriched black region, and a tungsten-enriched white region, respectively. Meanwhile, the sample is composed of two distinct crystalline phases with a particle size of not more than 5 μm, which is consistent with the SEM observations (Fig. 1d). The SAED image of Point 1 shows the crystal planes of (110), (112), and (002) along the [001] zone axis belonging to WB4. The SAED image of Point 2 shows the crystal planes of (113), (211), and (10–2) along the [2–51] zone axis belonging to β-rhombohedral boron. The diffraction wave of crystal B is masked by WB4 so only the diffraction peak of WB4 is shown in Fig. 1a30,33,43. In summary, the as-prepared sample is composed of the WB4 phase and β-B phase, which is the same as the WB4 materials reported in the works of literature33,43,44.

Vickers micro indentation hardness tests were performed on optically flat WB4-βB sample with applied loads ranging from 0.49 N–9.8 N, and hardness results of the as-prepared WB4-βB material are displayed in Fig. 1c. The hardness values of 43.91 ± 4.82 GPa under an applied load of 0.49 N and 27.72 ± 0.65 GPa under an applied load of 9.8 N are measured for the WB4-βB material. The 43.91 GPa hardness values measured at low loads are very close to 41.1–42.2 GPa of the theoretical prediction and 41.2–46.2 GPa of experimental tested data in the literature30,31,32,43. The results indicate that the as-prepared sample consisting of the WB4 phase and βB phase behaves as a super-hard property. Furthermore, the hardness of this WB4-βB sample is load-dependent and decreases as the load applied increases. This phenomenon of material hardness increasing with decreasing pressure is called the indentation size effect. The principle behind ISE is that smaller indenters produce harder values due to the influence of microstructural features such as grain boundaries, dislocations, and other defects, which have been observed in super-hard materials such as ReB2 and OsB245,46. As shown in Fig. S4 the fracture toughness of WB4-B was measured using the single-edge precracked Beam (SEPB) method as 3.28 MPa·m1/2. The nanoindentation in Fig. S3 measured the nano-hardness as 37.48 GPa and the modulus of elasticity as 599.17 GPa. This result is in agreement with the results reported by Mohammadi et al. 30. In addition, cemented carbide WC with a similar modulus to WB4-βB material is selected as the counterpart since the excellent compatibility of the tribo-pair materials can avoid severe wear on one side during the friction process.

Tribological behavior

To demonstrate the wear resistance of our designed WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair, the friction and wear properties were evaluated under 10–100 Pa vacuum conditions with different friction cycles. Figure 2 presents the three-dimensional (3D) worn topography, the two-dimensional (2D) worn profile of the WB4-βB disk, and the SEM images of the WC ball worn scar. According to the volume change shown by the worn surface topography of the WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair for the 5 × 104 friction cycles, the total concave groove volume is calculated to be 5.64 × 10−4 mm3, and the convex peak volume is 3.82 × 10−4 mm3 (Fig. 2a). The diameter of the circular worn scar on the WC surface is about 0.185 mm, and the calculated volume loss of the coupled ball is 1.92 × 10−5 mm3 (Fig. 2a). On the WB4-βB worn surface after 5 × 104 cycles, the volume of the concave groove is 4.30 × 10−4 mm3, and the volume of the convex peak is 6.57 × 10−4 mm3 (Fig. 2b). The diameter of the circular worn scar on the WC surface is 0.222 mm, and the calculated volume loss of the coupled ball is 3.97 × 10−5 mm3 (Fig. 2b). When the number of friction cycles is 1 × 105 friction times, the volume of the concave groove and convex peak on the WB4-βB worn surface is 5.10 × 10−4 mm3 and 0.13 × 10−4 mm3, respectively (Fig. 2c). The circular worn scar diameter of the coupled WC ball is 0.259 mm, and the wear volume is 7.36 × 10−5 mm3 (Fig. 2c).

The 3D topography and 2D worn scar profiles of the WB4-βB worn surface and the corresponding SEM images of the coupled WC ball worn surface. a The worn surface after 1.25 × 104 friction cycles. b The worn surface after 5 × 104 friction cycles. c The worn surface after 1 × 105 friction cycles. d Friction coefficient curve of WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair when the number of sliding is 1 × 105. (Vconcave groove and Vconvex peak are the volume change of the entire worn surface) e Dimension evolution of the WB4-βB disk and the WC ball at different sliding times. (+ indicates dimension increase, − indicates dimension reduction).

The friction coefficient curves show that the WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair has a shorter run-in period with a higher friction coefficient of 0.65 (Fig. 2d). During the steady-state period, the friction coefficient decreases to 0.55, and the friction curve also tends to be smooth. As shown in Fig. 2e, the friction cycles increase from 1.25 × 104 to 1 × 105, the WB4-βB disk shows the dimensional decrease of 9.06 × 10−8 mm3 N−1 m−1, the dimensional increase of 2.89 × 10−8 mm3 N−1 m−1, the dimensional decrease of 3.19 × 10−8 mm3 N−1 m−1, and the dimensional decreases of the corresponding coupled WC ball are 9.55 × 10−9 mm3 N−1 m−1, 5.06 × 10−9 mm3 N−1 m−1, and 4.69 × 10−9 mm3 N−1 m−1. When the number of friction cycles reaches 1 × 105, it is sufficient to meet the long-life wear-resistant test requirements. The depth of the WB4-βB worn track after 1 × 105 friction cycles is about 100 nm, equivalent to that it takes hundreds of friction cycles to remove the WB4-βB worn surface as a monolayer in size terms. Under the high maximum Hertz contact stress of 2.23 GPa, the wear resistance of WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair performs near-zero wear, not only the wear resistance of the unilateral counterpart.

Figure 2 demonstrates that with the increase in friction times, the depth dimension of the WB4-βB worn track was reduced from 191 nm after 1.25 × 104 cycles to 100 nm after 1 × 105 cycles, and the dimension of the WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair experienced the change of “decrease - increase - decrease”. We can find that some substances are generated on the worn surface, forming convex peaks, and compensating for the volume of wear loss. In addition, the wear volume of the coupled WC ball is an order of magnitude lower than that of the WB4-βB disk, which suggests the ability of WC material transfer to compensate for the volume loss of the WB4-βB disk is minimal. In this case, the WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair realizes near-zero wear in the low vacuum environment (without additional substances), indicating that the tribo-pair has the self-repairing ability during the wear process.

Figure 3 shows the dimensions of various tribo-pairs after friction, including the WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair in this work. There are clear boundaries for wear-resistant films, polymer composites, nanocrystalline metals, high-hard ceramics, and traditional materials. The wear resistance of traditional metal and ceramic bulk materials has significant limitations, the wear rate of the disk is in the order of 10−6 mm3 N−1 m−1, and the wear rate of the coupled ball is in the order of 10−7 mm3 N−1 m−1. The best wear resistance of bulk materials is attributed to about 10−8 mm3 N−1 m−1 order of magnitude of polymer composites and 10−7 mm3 N−1 m−1 order of magnitude of nano-metals and high-hard ceramics, respectively. Only a few films exhibit an ultra-low wear rate of 10−9 mm3 N−1 m−1 order of magnitude under exceptional circumstances, such as the self-mated hydrogen-rich DLC film tribo-pair, the fullerene-like MoS2 nanoparticles film/Al2O3 tribo-pair, and the Pt-Au film/Al2O3 tribo-pair47,48. Surprisingly, from 1.25 × 104 to 1 × 105 friction cycles, the variation of the WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair dimension is ± 10−8 mm3 N−1 m−1 with the expression of wear rate. Furthermore, WB4-βB super-hard ceramic can adapt to higher Hertz stress (2.23 GPa) compared to ultra-low wear films like MoS2 film (1.1 GPa)14, carbon film (0.7 GPa)49 and Pt-Au film (1.1 GPa)37, and polymer composites.

Figure 4 displays the worn surface of the WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair observed by scanning electron microscope and energy dispersive spectrometer. The worn track width of the WB4-βB disk and the worn scar diameter of the coupled WC ball increase with the sliding number. In addition, there is material accumulation on the worn track of the WB4-βB disk and the worn scar of the coupled WC ball after friction, which was not observed on the outer edge of the worn track. The EDS mapping confirms that the tribo-chemical products are dominated by the O element and a small amount of W and B elements (Fig. 4a–c). The worn surface morphology and EDS mapping in Fig. 4d illustrate that the oxide debris forms a tribo-layer on the worn surface under the frictional stress action, which is relatively uniformly attached to the substrate.

SEM images and the corresponding EDS elemental mapping of the worn surfaces of WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair after different friction cycles. The arrow points to the ball’s sliding direction during friction. a The worn surface after 1.25 × 104 cycles. b The worn surface after 5 × 104 cycles. c the worn surface after 1 × 105 cycles. d High-magnification SEM image of the worn track and the corresponding elemental mapping.

Figure 5 illustrates that the chemical states of tungsten, boron, carbon, and oxygen in the WB4-βB worn surface and subsurface with different etch depths were characterized by XPS. The C 1s peak for the surface-contaminated elemental C was 284.8 eV for the calibrated standard peak (Fig. 5c). There are also C=C bonds at 286.29 eV and C=O bonds at 288.70 eV, which are formed by the adsorption of contaminants and oxygen atoms on the worn surface50.

The high-resolution spectrum of the W 4f exhibits two binding energy (B.E) states of the W element, with the W 4f7/2 and W 4f5/2 peaks, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. The W 4f7/2 peaks range from 35.74 eV and W 4f5/2 peaks from 37.90 eV, which are associated with the W–O bond51. The results are consistent with the 530.76 eV peak in the O 1s spectrum, which is a W–O bond, and both belong to WO3 (Fig. 5d). The W 4f7/2 at 35.37–31.42 eV and W 4f5/2 at 37.44–37.47 eV are attributed to the W–B bond of WB450,52. In addition, low binding energy W–B appeared after etching the worn surface. The percentage of low binding energy W–B bonds increased with increasing etching time.

The peak of B 1s at 190.68 eV is associated with B-O bonds of B2O3. In comparison, the B 1s peak at 188.88 eV is linked to B–O bonds of boron-rich oxides (Fig. 5b)50,53,54. The subsurface B 1s peak at 187.78–187.82 eV belongs to the B–B bond of crystalline boron and the W–B bond of WB4, which have the same chemical state of the B element in both of them55,56,57. The results are consistent with the B–O bond represented by peak 532.34 eV, confirming the presence of B2O3 on the worn surface (Fig. 5d)58. The presence of adsorbed oxygen on the worn surface, with a peak at 531.69 eV, is due to defects in B2O3 with incomplete oxidation59. In addition, it is indicated in Fig. 5d that only lattice oxygen peaks are present at 530.53–530.57 eV and adsorbed oxygen peaks are present at 531.63–531.68 eV on the etched surface, and that the relative intensities of lattice oxygen and adsorbed oxygen decrease as the depth of etching increases. The above results indicate that the original worn surface consists of boron oxide with tungsten oxide. The ion-etched surfaces are characterized by the presence of substrate WB4 and crystalline B. Meanwhile, low binding energy W–B bonds are present on the etched surfaces, and it is presumed that the unstable WB4 is affected by ion etching to produce a new chemical state.

Figure 6a is the STEM image of the cross-section of the wear track, and the enlarged image of the square is marked area in Fig. 6b, c. As can be seen from the STEM image of the cross-section, the thin section consists of the Au protective layer, the tribo-oxidation layer, the intermediate layer, and the WB4-βB substrate from top to bottom (Fig. 6b). The surfaces of WB4 grains are smooth and without cracks and deformations, and there are tiny grooves on the worn surface of β-B grains. The thickness of the tribo-oxidation layer is 5–100 nm, which is significantly deposited above the β-B grains (Fig. 6b, c). The thickness of the intermediate layer is about 10–50 nm, mainly distributed above the WB4 grains. HRTEM images and corresponding FFT images of the tribo-layer and intermediate layer show that the tribo-oxidation layer is of amorphous composition and the intermediate layer is composed of WB4 grains and amorphous composition (Fig. 6d). The corresponding EDS element mapping on the cross-section of the worn surface, where the tribo-oxidation layer is enriched with oxygen elements and the intermediate layer is enriched with tungsten elements (Fig. 6e, f). Combined with the XPS results, we can discover that the tribo-oxidation layer is mainly composed of amorphous B2O3 and amorphous WO3, while the intermediate layer is mainly composed of WB4 grains, β-B grains, and amorphous oxide.

a STEM image of FIB-cut foil of the cross-section of the WB4-βB worn surface. b Enlarged view of the marked quadrate area of the interface in (a) between the WB4 phase and tribo-layer interface. c Enlarged view of the quadrate marked interface area in (a) between the βB phase and tribo-layer interface. d High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images and fast Fourier Transform (FFT) images of tribo-layer and intermediate layer in the worn surface. e EDS elemental mapping corresponding to the (b) region. f 1D compositional profile measured along the orange arrow in (b).

The micro-mechanism of the near-zero wear strategy is shown in Fig. 7, where the WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair achieves near-zero wear performance through the synergistic effect of the super-hard WB4-βB bulk material and the self-repair tribo-layer. At a high maximum Hertz contact stress of 2.23 GPa, the WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair produces a large frictional heat. Thermodynamically, the frictional heat generated by the mechanical abrasion provides the activation energy for the tribo-chemical reaction so that the wear debris undergoes a chemical reaction with oxygen. It can be found that at 1.25 × 104 and 5 × 104 frictional cycles, oxide micro-convex peaks protrude on the WB4-βB worn surface, consequently offering wear compensation. The frictional heat drives the formation of a low shear tribo-oxidation layer, which reduces the direct friction between the rough surfaces of the upper and lower samples, thereby reducing the generation of frictional heat and the influence of thermal radiation on the substrate. Thus, the thickness of the tribo-oxidation layer cannot be increased infinitely, and a dynamic balance is affected by the relative growth rate and removal rate. During long-life wear of 1 × 105 frictional cycles, wear compensation is transformed into wear loss due to the inadequate growth rate of the tribo-oxidation layer. It is the superiority of this self-repairing strategy that allows both the WB4-βB disk and the WC ball to meet the super-resistant wear.

The blue-green rectangle represents the WB4-B substrate. The gray hemisphere represents the WC counterpart. The brown-yellow region at the friction interface represents the friction oxides and the gray-white region represents WB4-B broken grains. The structure of the worn interface changes with the friction process as shown in schematic.

Wear has been recognized as the phenomenon of damage to or removal from the surface of a material because of interaction with a mating surface. In general, the degree of wear is evaluated by the amount of volume loss and the condition of the worn surface. The existing material systems are to realize ultra-low wear by self-consumption. For super-resistant materials like hydrogenated amorphous carbon, (a-C:H)12 and MoS214, graphitization or rearrangement of hexagonal crystal orientation occurs on the worn surface during friction. The interlayer slip of the basic crystal plane causes the breakage of the valence bond, resulting in the gradual removal of an atomic layer. In polymer matrix composites, aluminum oxide promotes the tri-chemical reaction of PTFE to form a molecular lubricating film, and this dynamic process of lubricant molecule formation-destruction provides wear protection17,18. In the above ultra-wear materials, no apparent wear compensation effect was found. Our research revealed the self-repairing mechanism by the formed tribo-chemical layer, reducing wear damage.

Conclusions

In this study, the WB4-βB super-hard material was prepared by the SPS method, and the WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair exhibits near-zero wear performance under 10–100 Pa vacuum conditions, which wear resistance mechanism is due to the synergistic effect of the super-hard WB4-βB substrate and the self-repairing tribo-layer. We found the abnormal wear phenomenon that during 1.25 × 104 to 1 × 105 friction cycles, the variation of this tribo-pair dimension is ±10−8 mm3 N−1 m−1 with the expression of wear rate. The WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair provides a novel design method to achieve near-zero wear tribo-pair by in-situ material repair, breaking through the traditional ultra-low-wear design method attempted to minimize wear and opening up a new path to the wear control of the mechanical system.

Methods

Materials fabrication

WB4-βB material with a ratio of tungsten to boron of 1:9 was fabricated by spark plasma sintering (SPS, LABOX-3010KF, Japan) method. Elemental boron powder (Baoding Zhongpu Ruite Technology Co., Ltd.; purity ≥99.9%; particle size 1 μm) and elemental tungsten powder (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd; purity ≥99.8%; particle size 75 μm) were milled in planetary high-energy ball milling (Fritsch Pulverisette 5, Germany) for 4 h, with the rotation speed of 250 r/min to obtain mixture uniformly. SPS sintering procedures are: The mixed powders were placed into a 25 mm diameter graphite mold and cold pressed at 10 MPa for 3 min; sintered at 1600 °C and held for 2 min at a sintering pressure of 15 MPa; the sintering was stopped, and the pressure was lowered to 0 MPa, and the samples were allowed to cool naturally to room temperature and then removed. The synthesized samples were cut and mechanically polished, awaiting subsequent testing. The polished samples’ surface roughness (Ra) was measured to be about 0.025 μm using a three-dimensional surface profilometer (MicroXAM-800), as shown Fig. S5.

Mechanical properties

Determination of Vickers micro indentation hardness of specimens using a diamond pyramid indenter microhardness tester (MH-5-VM). The diagonal length of indentation was measured using a 3D surface profilometer (KEYENCE, VHX-6000). To ensure very accurate hardness measurements, take the average of the indentation measurements of at least 20 randomly selected points on the sample for each loading. Nanoindentation tests were performed using an Anton Parr NHT2 nanoindentation machine with a Berkovich diamond tip. There were at least 6 indentations on each material surface and the maximum pressure applied was up to 50 mN. The fracture toughness of the material was tested by the single-sided pre-cracking method with a sample size of 16 mm × 4 mm × 3 mm and an opening depth 2 mm. At least 6 samples were tested at an indenter downward pressure rate of 0.5 mm/min.

Wear performance analysis

The tribological properties of the WB4-βB/WC tribo-pair were evaluated by a rotational tribometer (GHT-1000E, Zhongke Kaihua Technology Development Co., Ltd). The disks were made from sintered WB4-βB samples, and WC balls (φ: 6 mm) were selected as the upper sample. YG6 ball (Zhejiang Jienaier New Material Co., Ltd) has a Vickers hardness of 19 GPa, surface roughness of 0.025 μm, an elastic modulus of 642 GPa, and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.20460. The YG6 (WC-6 wt% Co) ball will be written as a WC ball in the article. The specifications for the friction experiment are as follows: a maximum Hertzian contact stress of 2.23 GPa (with an applied load of 5 N), a sliding velocity of 0.2 m/s (or 400 r/m), a rotation radius of 5 mm, a vacuum measurement of 10–100 Pa, a test temperature around 23 °C, and laboratory air humidity ranging from 20% to 30%. Carry out at least three wear tests under the same conditions and take the average value of the repeated test data within the error range to ensure the repeatability of the test and reliability. The wear volume (V) of the sample was measured using a non-contact 3D profilometer (MicroXAM-800, KLA-Tencor, USA) and the worn scar diameter (d) of the WC coupled ball was measured using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JSM-5601LV).

Structure characterization

The sample microstructure and composition were verified by X-ray diffraction meter (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and transmission electron microscope (TEM). The physical phase analysis of the samples was performed by XRD (Empyrean, PANalytical B.V.) with the technical parameters of the instrument as Cu target (Kα, λ = 1.5418 Å), accelerating voltage and accelerating current of 40 kV and 40 mA, with a scan step size of 0.028°. The samples and worn surfaces were examined by scanning electron microscope (SEM, JSM-5601LV) equipped with an energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) at an operating voltage of 20 kV for morphology and element distribution. The chemical elemental states of the surfaces at different etch depths were characterized using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, ESCA LAB 250Xi). The radiation source is Al-Kα radiation, the test tube voltage is 15 kV, and the test spot size is 400 μm. Etching was performed with an Ar gun at a beam energy of 2 kV and a beam current of 10 mA, and the etching rate was typically 0.2 nm/s. The sectioned samples were prepared in the WB4-βB wear region using focused ion beam (FIB) device (ZEISS Crossbeam 350) preparation. The WB4-βB Sliced samples were studied by an FEI Talos F200X transmission electron microscope (TEM) at a working voltage of 200 kV.

References

Dwivedi, N. et al. Boosting contact sliding and wear protection via atomic intermixing and tailoring of nanoscale interfaces. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau7886 (2019).

Holmberg, K. & Erdemir, A. Influence of tribology on global energy consumption, costs and emissions. Friction 5, 263–284 (2017).

Sawyer, W. G., Argibay, N., Burris, D. L. & Krick, B. A. Mechanistic studies in friction and wear of bulk materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 44, 395–427 (2014).

Berman, D., Deshmukh, S. A., Sankaranarayanan, S. K., Erdemir, A. & Sumant, A. V. Macroscale superlubricity enabled by graphene nanoscroll formation. Science 348, 1118–1122 (2015).

Liu, C. et al. Reactive wear protection through strong and deformable oxide nanocomposite surfaces. Nat. Commun. 12, 5518 (2021).

Kuwahara, T. et al. Mechano-chemical decomposition of organic friction modifiers with multiple reactive centres induces superlubricity of ta-C. Nat. Commun. 10, 151 (2019).

Grutzmacher, P. G. et al. Superior wear-resistance of Ti3C2Tx multilayer coatings. ACS Nano 15, 8216–8224 (2021).

Liu, S. W. et al. Robust microscale superlubricity under high contact pressure enabled by graphene-coated microsphere. Nat. Commun. 8, 14029 (2017).

Khurshudov, A. G., Kato, K. & Koide, H. Wear of the AFM diamond tip sliding against silicon. Wear 203-204, 22–27 (1997).

Berman, D., Erdemir, A. & Sumant, A. V. Few layer graphene to reduce wear and friction on sliding steel surfaces. Carbon 54, 454–459 (2013).

Androulidakis, C., Koukaras, E. N., Paterakis, G., Trakakis, G. & Galiotis, C. Tunable macroscale structural superlubricity in two-layer graphene via strain engineering. Nat. Commun. 11, 1595 (2020).

Chen, X. et al. Evolution of tribo-induced interfacial nanostructures governing superlubricity in a-C:H and a-C:H:Si films. Nat. Commun. 8, 1675 (2017).

Scharf, T. W. & Prasad, S. V. Solid lubricants: a review. J. Mater. Sci. 48, 511–531 (2012).

Chhowalla, M. & Amaratunga, G. A. J. Thin films of fullerene-like MoS2 nanoparticles with ultra-low friction and wear. Nature 407, 164–167 (2000).

Macknojia, A. et al. Macroscale superlubricity induced by MXene/MoS2 nanocomposites on rough steel surfaces under high contact stresses. ACS Nano 17, 2421–2430 (2023).

Argibay, N., Chandross, M., Cheng, S. & Michael, J. R. Linking microstructural evolution and macro-scale friction behavior in metals. J. Mater. Sci. 52, 2780–2799 (2016).

Qi, H. et al. Ultralow friction and wear of polymer composites under extreme unlubricated sliding conditions. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 4, 1601171 (2017).

McElwain, S. E., Blanchet, T. A., Schadler, L. S. & Sawyer, W. G. Effect of particle size on the wear resistance of alumina-filled PTFE micro- and nanocomposites. Tribol. Trans. 51, 247–253 (2008).

Yin, X., Jin, J., Chen, X., Rosenkranz, A. & Luo, J. Ultra-wear-resistant MXene-based composite coating via in situ formed nanostructured tribofilm. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 32569–32576 (2019).

Liu, Y., Erdemir, A. & Meletis, E. I. An investigation of the relationship between graphitization and friction behavior of DLC coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 86-87, 564–568 (1996).

Erdemir, A. & Donnet, C. Tribology of diamond-like carbon films: recent progress and future prospects. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 39, R311–R327 (2006).

Chang, T., Panhwar, F. & Zhao, G. Flourishing self‐healing surface materials: recent progresses and challenges. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 7, 1901959 (2020).

Aouadi, S. M., Gu, J. & Berman, D. Self-healing ceramic coatings that operate in extreme environments: a review. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 38, 050802 (2020).

Wang, S. & Urban, M. W. Self-healing polymers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 562–583 (2020).

Bakoglidis, K. D. et al. Self-healing in carbon nitride evidenced as material inflation and superlubric behavior. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 16238–16243 (2018).

Nakahata, M., Takashima, Y., Yamaguchi, H. & Harada, A. Redox-responsive self-healing materials formed from host-guest polymers. Nat. Commun. 2, 511 (2011).

Chen, X., Han, Z., Li, X. & Lu, K. Lowering coefficient of friction in Cu alloys with stable gradient nanostructures. Sci. Adv. 2, e1601942 (2016).

Yeung, M. T., Mohammadi, R. & Kaner, R. B. Ultraincompressible, superhard materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 46, 2.1–2.21 (2016).

Kaner, R. B., Gilman, J. J. & Tolbert, S. H. Materials science. Designing superhard materials. Science 308, 1268–1269 (2005).

Mohammadi, R. et al. Tungsten tetraboride, an inexpensive superhard material. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 10958–10962 (2011).

Wang, M., Li, Y., Cui, T., Ma, Y. & Zou, G. Origin of hardness in WB4 and its implications for ReB4, TaB4, MoB4, TcB4, and OsB4. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 101905 (2008).

Gu, Q., Krauss, G. & Steurer, W. Transition metal borides: superhard versus ultra-incompressible. Adv. Mater. 20, 3620–3626 (2008).

Ma, K., Cao, X., Yang, H. & Xue, X. Formation of metastable tungsten tetraboride by reactive hot-pressing. Ceram. Int. 43, 8551–8555 (2017).

Yeung, M. T. et al. Superhard monoborides: hardness enhancement through alloying in W1−xTaxB. Adv. Mater. 28, 6993–6998 (2016).

Akopov, G., Pangilinan, L. E., Mohammadi, R. & Kaner, R. B. Perspective: superhard metal borides: a look forward. APL Mater. 6, 070901 (2018).

Parakhonskiy, G., Dubrovinskaia, N., Bykova, E., Wirth, R. & Dubrovinsky, L. Experimental pressure-temperature phase diagram of boron: resolving the long-standing enigma. Sci. Rep. 1, 96 (2011).

Curry, J. F. et al. Achieving ultralow wear with stable nanocrystalline metals. Adv. Mater. 30, e1802026 (2018).

Akopov, G., Yeung, M. T. & Kaner, R. B. Rediscovering the crystal chemistry of borides. Adv. Mater. 29, 1604506 (2017).

Yu, Z. et al. High-temperature tribological behaviors of MoAlB ceramics sliding against Al2O3 and Inconel 718 alloy. Ceram. Int. 46, 14713–14720 (2020).

Benamor, A. et al. Friction and wear properties of MoAlB against Al2O3 and 100Cr6 steel counterparts. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 39, 868–877 (2019).

Burke, A. R. et al. Ignition mechanism of the titanium boron pyrotechnic mixture. Surf. Interface Anal. 11, 353–358 (1988).

Romans, P. A. & Krug, M. P. Composition and crystallographic data for the highest boride of tungsten. Acta Crystallogr. 20, 313–315 (1966).

Akopov, G. et al. Effects of variable boron concentration on the properties of superhard tungsten tetraboride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 17120–17127 (2017).

Long, Y., Wu, Z., Zheng, X., Lin, H. T. & Zhang, F. Mechanochemical synthesis and annealing of tungsten di‐ and tetra‐boride. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 103, 831–838 (2019).

Chung, H. Y., Yang, J. M., Tolbert, S. H. & Kaner, R. B. Anisotropic mechanical properties of ultra-incompressible, hard osmium diboride. J. Mater. Res. 23, 1797–1801 (2011).

Chung, H.-Y., Weinberger, M. B., Yang, J.-M., Tolbert, S. H. & Kaner, R. B. Correlation between hardness and elastic moduli of the ultraincompressible transition metal diborides RuB2, OsB2, and ReB2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 261904 (2008).

Zeng, G., Tan, C.-K., Tansu, N. & Krick, B. A. Ultralow wear of gallium nitride. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 051602 (2016).

Zeng, G., Tansu, N. & Krick, B. A. Moisture dependent wear mechanisms of gallium nitride. Tribol. Int. 118, 120–127 (2018).

Shi, J. et al. Nanocrystalline graphite formed at fullerene-like carbon film frictional interface. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 4, 1601113 (2017).

Zhao, F. et al. Synthesis and characterization of WB2-WB3-B4C hard composites. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 82, 268–272 (2019).

Wang, L. & Zan, L. WO3 in suit embed into MIL-101 for enhancement charge carrier separation of photocatalyst. Sci. Rep. 9, 4975 (2019).

Jiang, C. et al. Preparation and characterization of superhard AlB2-type WB2 nanocomposite coatings. Phys. Status Solidi A Appl. Res. 210, 1221–1227 (2013).

Chrzanowska-Giżyńska, J., Denis, P., Woźniacka, S. & Kurpaska Mechanical properties and thermal stability of tungsten boride films deposited by radio frequency magnetron sputtering. Ceram. Int. 44, 19603–19611 (2018).

Wang, H., Sun, Z., Wei, Z., Wu, Y. A simple grinding method for preparing ultra-thin boron nanosheets. Nanomaterials 12, 1784 (2022).

Pan, Z. et al. Study on the preparation of boron-rich film by magnetron sputtering in oxygen atmosphere. Appl. Surf. Sci. 388, 392–395 (2016).

Wang, J. et al. Oxygen vacancy induced band-gap narrowing and enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity of ZnO. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4, 4024–4030 (2012).

Xu, T. T. et al. Crystalline boron nanoribbons: synthesis and characterization. Nano Lett. 4, 963–968 (2004).

Cao, Y. et al. B–O bonds in ultrathin boron nitride nanosheets to promote photocatalytic carbon dioxide conversion. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 9935–9943 (2020).

Liu, F., Zhao, J., Xuan, G., Zhang, F. & Yang, L. Spatial evolution characteristics of active components of copper-iron based oxygen carrier in chemical looping combustion. Fuel 306, 121650 (2021).

Doi, H., Fujiwara, Y., Miyake, K. & Oosawa, Y. A systematic investigation of elastic moduli of Wc-Co alloys. Metall. Trans. 1, 1417–1425 (1970).

Bakshi, S. D., Basu, B. & Mishra, S. K. Fretting wear properties of sinter-HIPed ZrO2–ZrB2 composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 37, 1652–1659 (2006).

Berman, D. et al. Operando tribochemical formation of onion-like-carbon leads to macroscale superlubricity. Nat. Commun. 9, 1164 (2018).

Kar, S., Sahu, B. B., Kousaka, H., Han, J. G. & Hori, M. Study of the effect of normal load on friction coefficient and wear properties of CNx thin films. AIP Adv. 10, 065214 (2020).

Krick, B. A. et al. Ultralow wear fluoropolymer composites: Nanoscale functionality from microscale fillers. Tribol. Int. 95, 245–255 (2016).

Cong, Y. B. et al. Wear properties of a bulk nanocrystalline Fe-1at% Zr alloy. Mater. Today Commun. 31, 103427 (2022).

Ullah, S., Haque, F. M. & Sidebottom, M. A. Maintaining low friction coefficient and ultralow wear in metal-filled PTFE composites. Wear 498–499, 204338 (2022).

Sun, Q. et al. Single-phase (Hf-Mo-Nb-Ta-Ti)C high-entropy ceramic: a potential high temperature anti-wear material. Tribol. Int. 157, 106883 (2021).

Wäsche, R., Klaffke, D. & Troczynski, T. Tribological performance of SiC and TiB2 against SiC and Al2O3 at low sliding speeds. Wear 256, 695–704 (2004).

Testa, V. et al. Alternative metallic matrices for WC-based HVOF coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 402, 126308 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92266204 and 52175197), the West Light Foundation of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (xbzg-zdsys-202317), and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (2022425).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guixin Hou: designing experiments (lead), experimental validation (lead), data analysis (lead), writing-original drafts (lead). Shengyu Zhu: conceptualization (lead), designing experiments (lead), writing-reviewing, and editing (lead). Weimin Liu: project administration (equal). Jun Yang: project administration (lead), obtaining funding (lead), writing-review, and editing (lead). Jun Cheng: project administration (equal), obtaining funding (lead), writing-review, and editing (lead). Hui Tan: supervised the experiment (equal). Wenyuan Chen: data analyzed (equal). Jiao Chen: methodology (equal). Qichun Sun: supervised the experiment (equal). Juanjuan Chen: data analysis (equal). Peixuan Li: data analysis (equal). William Yi Wang: data analysis (equal), writing-review, and editing (equal). All authors carefully reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Philip Egberts and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: John Plummer. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, G., Zhu, S., Tan, H. et al. Near-zero-wear with super-hard WB4 and a self-repairing tribo-chemical layer. Commun Mater 5, 222 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00667-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00667-1