Abstract

Defect engineering has developed over the last decade to become an inimitable tool with which to shape Metal-Organic Framework (MOF) chemistry; part of an evolution in the perception of MOFs from perfect, rigid matrices to dynamic materials whose chemistry is shaped as much by imperfections as it is by their molecular components. However, challenges in defect characterisation and reproducibility persist and, coupled with an as-yet opaque role for synthetic parameters in defect formation, deny chemists the full potential of reticular synthesis. Herein we map the broad implications defects have on MOF properties, highlight key challenges and explore the remarkable ways imperfection enriches MOF chemistry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal-organic Frameworks (MOFs) are a burgeoning class of hybrid organic-inorganic materials composed of metal cluster nodes interconnected by multitopic organic ligands to form highly crystalline, porous and chemically mutable structures1,2. Such an opening line would have succinctly captured the field only a decade ago. On the surface it still largely does, yet much has changed. The classical MOF is a rigid matrix defined by the chemical properties and dimensions of its molecular components, given to being by the power of reticular synthesis. The modular, chemically mutable design allows MOFs to be tuned to suit particular applications with angstrom scale precision, at least in theory. Breaking from this crystallography-centric view, which defined its infancy, MOF chemistry has evolved in recent years to embrace the imperfect, dynamic lattice3,4,5,6. The underlying form remains guided by reticular synthesis, but the chemistry and physical properties are enriched by imperfections.

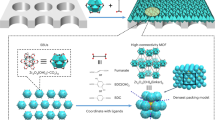

As with any crystalline solid, the perfect structure portrayed by crystallography belies the omnipresent lattice defects and dynamic nature of coordination bonds3,4,5,6. Such imperfections are a ubiquitous feature of solid-state chemistry where they influence global properties even at vanishing concentrations7. For instance, just 0.1% defectivity in graphene or boron arsenide causes up to 95% reduction in thermal conductivity8,9. In MOFs, lattice defects manifest as missing linkers (ML) and/or missing clusters (MC) and have similarly drastic physicochemical implications (Fig. 1)10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. For example, the blue-green colour associated with the prototypical CuII framework HKUST-1 actually arises from ubiquitous CuI defects rather than the CuII paddlewheel motif15. That this was revealed only recently illustrates the challenges associated with characterising lattice imperfections and defining their role in MOF chemistry. Since the first in-depth study concerning missing linker defects in UiO-66 was published in 201120, an extraordinary tapestry of defectivity has been unveiled. This transformation has occurred in concert with a significant advancement in experimental characterisation techniques that allow the local environment to be probed, in some cases providing real-space visualisation of defects19,21,22.

MOFs form from organic and inorganic components to produce a crystalline material (a) featuring a mixture of ideal cells (b) and a variable degree of defects, including missing linker (left) and missing cluster defects (right). Note: a green monotopic linker replaces the missing linker to complete the coordination sphere of the transition metal node (c). Related to classic defectivity are transient defects that arise from dynamic metal-linker bonds; this concept is explored in detail in Fig. 2. d The extent and type of defectivity present within a MOF sample can be modulated via both synthetic and post-synthetic methods, creating a continuum of defectivity with diverse physicochemical properties (e).

It is in this rapidly changing environment that defect engineering has captured the imagination of MOF chemists23,24,25,26 and dramatically expanded the utility and richness of MOF chemistry. Defectivity has significant implications on mechanical stability13,14,27,28,29,30, hydrophobicity31, photophysical properties32, thermal conductivity33,34, catalytic activity23,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42, pore size43,44,45,46,47 and surface area44,48,49,50 which are pertinent to commercial applications12,51,52. Properties involving cooperative lattice phenomena, including negative thermal expansion53,54 and negative gas adsorption55, are also influenced by defectivity. In some cases these manifestations are desirable: for instance mass transport benefits from hierarchical porosity introduced by defect engineering56,57. However, in applications such as molecular sieving, success is dependent on angstrom scale refinement of the sieve pores, which is undermined by defectivity58,59,60,61. Thus, the optimum defectivity for a specific application exists somewhere along a defectivity continuum with extraordinary physicochemical diversity (Fig. 1). Harnessing this potential will require overcoming significant challenges, such as establishing the synthetic origin of defectivity, developing reliable characterisation techniques and consistent reporting, and ensuring synthesis protocols are reproducible18,62.

This contribution posits defectivity as an intractable feature of MOF chemistry, the formation and evolution of which is intimately linked to the dynamic nature of metal-ligand coordination bonds (Fig. 2)4,5,63,64. The emergence of defect engineering has parallelled interest in dynamic metal-ligand bonding which persists in even the more robust ZrIV frameworks63,64,65. We consider these short-lived dissociated metal-linker states as ‘transient defects’, distinct from the ‘classical’ ML or MC defects in both lifetime and in the sense that no structural components are missing. This underlying dynamic behaviour facilitates facile ligand/cation exchange66,67,68, reversible guest responsive structural transformations69,70,71 and the preparation of glass/liquid MOFs4,5. Moreover, dynamic metal-linker bonding is central to the emergence of crystallinity in MOFs, and equally so to the evolution of defectivity during crystallisation and post-synthetic handling63. The latter point raises an important but as yet rarely discussed question: as chemists seek to tune the extent, type and spatial distribution of defects within a fundamentally dynamic platform, how long – in terms of processing, handling and time - does it take before the engineered defects become defective? To answer this question a comprehensive understanding of dynamic processes and defectivity will be necessary. In particular, the elucidation of dynamic interactions and characterisation of disordered or defective frameworks requires new experimental and computational tools, and a departure from the classic MOF model6,54,72,73,74,75,76.

Related to defectivity is the presence of dynamic metal-ligand bonds (a) which manifest as transient open metal sites pertinent to adsorption and catalysis applications (b). Liquid MOFs are typically prepared by heating crystalline MOFs to form a melt state characterised by persistent dynamic coordination between molecular components, this can be quenched to form an amorphous coordination network classified as a glass (c). The now widely recognised tendency for MOFs to undergo facile linker or cation exchange is enabled by dynamic metal-linker interactions (d).

Defectivity has been the focus of extensive discussion over the last decade. The benefits of defect engineering are well established24,25,42 and are not the focus of this contribution. Rather, we explore the long-term challenges which persistently beleaguer chemists seeking to harness defect engineering. These include accurate characterisation and consistent reporting of defectivity, and the reproducible synthesis of phase pure samples with consistent defectivity. We consistently advocate that collaborative interlaboratory studies are an underutilised but effective tool for assessing reproducibility in MOF synthesis and establishing the precise role of synthetic parameters in defect engineering. The value of reproducible synthesis and accurate characterisation is contingent on the stability of engineered defect landscapes. We contend that the role of dynamic bonding in defect formation and, particularly, the evolution of defect landscapes; cannot be understated (Table 1). To fully realise the promise of defect engineering, chemists must embrace the dynamic nature of coordination bonds and employ their most sophisticated experimental and computational tools to uncover the spatial, chemical and temporal diversity hiding behind the crystalline façade.

Characterisation and quantification of classical lattice defects in MOFs

Considering the pertinence of defects in all facets of MOF chemistry, their unambiguous characterisation and reproducibility are vital to harnessing the potential physicochemical diversity on offer18,62. To this end, a slew of characterisation techniques are regularly employed to quantify ML and MC defects, many of which were developed in the context of UiO-66 (see Box 1)17,77. The tools of defect analysis and their sophistication have necessarily evolved in tandem with the discovery of new defect types as well as their impact on readily measured physicochemical properties. The simplest and most widely reported defect analyses assess defectivity through its effect on MOF properties. Evoking Plato’s Cave, this requires that experimentally measured metrics such as stoichiometry, surface area, diffraction pattern, thermal stability or pore-size distribution be compared to those of an ideal version of the framework. For example, Thermo-gravimetric Analysis is frequently used to quantify missing linker defects by establishing the ratio of inorganic to organic components through complete combustion of the former. By comparing the experimental value to that of the ‘ideal’ framework and making basic assumptions about the type of defect(s) present, an estimate of sample defectivity is obtained. The coexistence of MC and ML defects (and correlation of the former) complicates these simple assessments. Assumptions must be made. A more complete picture requires careful application of multiple complimentary techniques that can distinguish and quantify specific defect species78.

Chemical characterisation of defect sites in-situ involves more sophisticated techniques which are less amenable to routine analysis and are more sample specific48,79,80,81,82. Exploiting the porosity inherent to most MOFs, various probe molecules have been employed to establish the chemical environment of defects in-situ. For example, the prototypical CuII framework HKUST-1 exhibits CuI defects which arise from impure inorganic precursors or in-situ thermally induced reduction of CuII moieties40. These are readily identified by monitoring CO probe molecules using IR spectroscopy because the CO stretching frequency is highly sensitive to the chemical environment of the node site to which it coordinates79,83,84,85. When supported with computational modelling, a picture emerges of the local environment at defect sites and their real-time evolution79. The same approach has a long history in zeolite chemistry86,87,88. Beyond CO, the catalogue of probe molecules now includes a homologous series of phosphines80 and even fluorescent proteins81, providing an expansive and bespoke toolbox with which to chemically and spatially distinguish defects. To observe defects in real-space however, chemists have turned to advancements in electron microscopy techniques – particularly High Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM) – which enable imaging of MOF lattice defects (Fig. 3) and direct evidence for defect correlation and defective nanoregions within the crystal lattice19,22,89. We note that electron bombardment can also generate missing linker defects90,91, careful consideration of these effects is essential when using HRTEM for defect analysis. It is by harnessing chemical probe experiments, computational chemistry and microscopy that chemists have revealed increasingly complex layers of defectivity in prototypical frameworks.

The MOF UiO-66 is composed of BDC linkers interconnected by 12 connected MIV-oxo clusters (M = Zr, Hf) to form a robust and highly porous network. A representation of the ideal structure with fcu net, including the ideal 12-connected cluster, is presented (a). The material is highly susceptible to defects including ML (bcu net) and MC (reo or scu net) (b). MC defects are known to form correlated defect nanoregions in some UiO samples, leading to aggregation of defects which is represented schematically in i) and ii). HRTEM image showing significant correlation of missing cluster defects adopting the scu net (scale bar represents 5 nm) iii. The scu structural model, simulated potential map and actual averaged HRTEM image representing one unit cell (left to right, iv). Image components c(ii) adapted with permission from ref. 21. Copyright 2014 Springer Nature and c(iii)-c(iv) adapted with permission from ref. 19. Copyright 2019 Springer Nature.

Even in extensively studied MOFs, new layers of previously imperceptible chemistry are being revealed using increasingly bespoke characterisation techniques22,54,92,93,94,95. Exemplars include defect termination and the fascinating interaction between framework nodes and guest molecules63,96,97,98. In an elegant example, Fu et al. employed in-situ 13C Solid-state (SS) NMR and DFT calculations to identify the coordination geometry and location of formate defects in MOF-7448. Perhaps because the formate in question arises from in-situ decomposition of DMF during solvothermal synthesis rather than intentional addition of formic acid modulator, the defects had previously escaped notice. Yet they significantly impact on adsorptive properties: the surface area of Mg-MOF-74 decreases from 1900 m2g−1 in the ideal framework to 700 m2g−1 in defective frameworks, accompanied by concomitant reduction in CO2 adsorption. This study underscores two key points that lie at the core of this contribution: (1) undetected and physicochemically significant defectivity persists even in prototypical frameworks due to challenges in identifying such species and (2) sophisticated computational and experimental techniques are becoming essential for elucidating more obscure MOF chemistry which is not perceptible via classic diffraction techniques63,65,92,96,98,99. The latter is true in the emerging field of amorphous MOFs74,75,95,100 and is becoming so more generally as materials scientists seek to unravel the local chemical environment within crystalline frameworks and its effect on global properties4,5,99.

The devil is in the details

While the subtle physicochemical implications have long been appreciated in solid-state chemistry, the overt outcomes of defectivity such as hierarchical porosity or catalytic activity have garnered more attention from MOF chemists. But defectivity is increasingly understood to impact MOF bulk modulus, mechanical stability and thermal conductivity13,14,27,28,29,30,33,34,101,102. Such subtle implications are not always prioritised (or evident) in the laboratory, but can become pronounced at scale and as MOFs are increasingly integrated into hybrid materials51. For example, to avoid cracking and delamination in devices, the thermal expansion properties of a MOF must be compatible with those of materials with which it is interfaced51. Similarly, thermal conductivity becomes more influential at scale due to the need to efficiently dissipate the heat released during processes such as adsorption103,104,105. Yet thermal expansion and thermal conductivity remain poorly represented in MOF literature and the effects of defectivity are less understood than for other physicochemical properties.

Extraordinary surface areas and chemical mutability has placed MOFs at the forefront of future gas adsorption applications. Adsorption is however an exothermic process and since MOFs exhibit poor thermal conductivity, heat dissipation therefore becomes a concern. Low density and high porosity restrict thermal transport in MOFs which explains why ZIF glasses exhibit higher thermal conductivity than their crystalline (and more porous) counterparts106. Porosity is not the only culprit though. In solid-state materials, phonons play an integral role in thermal conductivity8,9 and it is increasingly evident that lattice defects in MOFs (and adsorbate molecules105) induce phonon scattering that reduces thermal conductivity further than intrinsic porosity would demand33,34. Intriguingly, correlated MC defects are associated with an increase in thermal conductivity compared to randomly distributed MC or ML defects33. This behaviour is attributed to reduced phonon scattering in the direction of thermal transport and hints at a complex interplay between defectivity, phonon scattering and thermal transport that may concern other processes in which phonons are implicated107. Thus the effects of defectivity on MOF chemistry concern as much the infinitesimal details of lattice vibrational modes as they do the palpable outcomes of defect engineering. While much anticipation accompanies the latter, the devil is in the details and commercial emphasis on benchmark physicochemical properties will refocus attention accordingly. At present though, studies concerning the thermal transport properties of MOFs typically assume a ‘defect-free’ material or do not consider defects at all33,34. In this conceptual simplification a vital opportunity to define fundamental physicochemical attributes in the context of defectivity is overlooked.

Reproducible MOF synthesis

While challenges remain in distinguishing, quantifying and spatially elucidating defectivity; advancements in characterisation will only benefit the field if defectivity in a given framework can be reliably reproduced across time and place. Indeed, variable phase purity or defectiveness is incompatible with commercial applications62. Discussion of MOF defectivity naturally intersects with this broader debate around reproducibility of MOF synthesis outcomes. For example, Kieslich and colleagues attribute the significant variability in experimental bulk moduli to poor defect reproducibility across samples of the same MOF analysed by different laboratories28. Part of this issue arises from phase impurities62 (including amorphous impurities) and/or variable and inadequately characterised defectivity. Even different samples of the same MOF can exhibit varying defectivity between for instance, powder and epitaxial forms, which reflects differences in synthesis conditions108. One strategy for eliminating variable sample defectivity is to prepare one large batch of MOF on which all analysis is performed109. While this sidesteps the core issue, the paucity of studies on defect reproducibility, coupled with genuine characterisation challenges, currently leaves little alternative.

The question of reproducible phase purity and defectivity in MOFs was underscored in an insightful interlaboratory study by Boström et al.62. The focus was a family ZrIV Porphyrinic Coordination Network (PCN) MOFs which can form multiple phases under the same synthesis conditions62,110 and are highly susceptible to defects78. Strikingly, under the interlaboratory study only 1 in 10 syntheses targeting PCN-222 yielded phase pure product despite implementing an identical literature procedure across the participating laboratories. Synthesis of phase pure ligand ordered PCN-224 failed in all cases. Factors including reaction vessel dimensions, hydration of the inorganic precursor and ambient humidity are likely contributors to the erratic reproducibility. This rouses an unavoidable question: if subtle parameters so profoundly impact MOF morphology, why should defectivity be any less susceptible to variation? Considering the potent implications on physicochemistry, defect reproducibility remains conspicuously underexplored. We note that the interlaboratory study cited above did report – albeit cautiously, considering the erratic phase purity of the samples - variable defectivity across PCN samples. This work simultaneously highlights the challenge facing reproducible MOF synthesis and outlines an effective roadmap for much needed interlaboratory studies concerning defect reproducibility and characterisation.

Defect-free MOFs?

Having established defectivity as an easily obfuscated but central determinant of MOF physicochemistry, we turn now to its minimisation and the temporal stability of defect landscapes. The popular term ‘defect-free’ is a misnomer: defects cannot be entirely eliminated, but can be minimised using synthetic58,111 and post-synthetic strategies19,112. Samples with minimal defectivity show improved stability, are better model materials and find virtue in applications such as molecular sieving and sensing15,58,111. Thus, two motivations for defect minimisation can be distinguished: the preparation of model materials for fundamental studies and the optimisation of materials for applications such as molecular sieving or sensing. Embodying the former scenario, a recent study explored the epitaxial growth of optically pure, defect-free HKUST-1 thin films which are of interest in fundamental chemistry and sensing applications (Fig. 4)15. Rather than exhibiting the blue hue synonymous with HKUST-1, the films are colourless owing to the effective elimination of strongly absorbing CuI/CuII defects. Recent work by Liu et al. epitomises the latter category: a series of ultra-low defectivity UiO membranes with precisely tuned pore apertures were prepared and demonstrated exceptional H2/CO2 selectivity an order of magnitude greater than defective analogues (Fig. 4)58. The examples above demonstrate that defectivity can be minimised to obtain materials that closely approximate their ideal counterparts. The question that is particularly apparent in this context, but is just as relevant in classic defect engineering scenarios, is how effectively can specific defect landscapes be maintained under operating conditions given the persistence of dynamic metal-ligand bonding in extended frameworks?4,5.

a Defect-free UiO membranes are synthesised from fumaric acid, BDC or BDC-OH linkers to form a family of supported membranes with precisely regulated pore sizes. b The H2/CO2 selectivity UiO membranes is dependent on the pore size determined by linker choice and strongly degraded by increased defectivity. c HRTEM image of UiO-fumarate membrane provides evidence for a near ideal lattice. Figure elements adapted with permission from ref. 58. Copyright 2023 Springer Nature. d The structure of HKUST-1 is composed of CuII paddlewheel nodes bridged by BTC linkers. A known defect involves reduction of one CuII centre and loss of a single carboxylate linker. Defective HKUST-1 SURMOF samples exhibit a blue colour while high quality thin films are colourless. Figure elements adapted with permission from ref. 15. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

While appreciation of dynamic metal-ligand bonding continues to grow in the MOF community, the chemistry is not new. For instance, the facile displacement of labile ligands is central to transition metal catalysis113,114. In MOFs, dynamic metal-ligand bonding is implicated in the mechanism of hydrothermal decomposition which can be considered as an accumulation of defects that culminates in loss of crystallinity56,115,116,117. Facile linker and cation exchange as well as the emergence of glass and liquid MOFs is predicated on dynamic bonding. Reversible dissociation of metal-linker bonds has been invoked in catalytic and adsorptive applications that exploit the resulting transitory open metal sites (Fig. 2)70,118,119,120,121,122,123,124. Thus, one could make the case that reversible metal-linker dissociation events create a transient defect which is separate from classic ML defects only in as far as life-time is concerned. Spectroscopy experiments have confirmed that such species (or at least the soft-mode precursory states) are ubiquitous in carboxylate MOFs64,65,107,125 and that temperature65, particle size125,126 and guest molecules64 modulate the relative populations of ‘tight’ and ‘loose’ states. However, we posit that MOF defects as we define them here constitute a departure from ideal stoichiometry – that is, components are missing rather than momentarily detached. In this sense dynamic bonding is an explanation for evolving defectivity within a crystal such as occurs during activation, crystal growth or post-synthetic modification; but is itself distinct from classic ML or MC defectivity. We define ‘transient defects’ to capture this distinction. The fact that post-synthetic defect engineering is frequently affected by design40,111,127 but also unintentionally during processes such as activation, sorption and solvent exchange attests that designer defect profiles are liable to change under forcing conditions79. Even during crystallisation, the relative abundance of MC and ML defects in UiO-66 evolves due to Ostwald Ripening processes that produce larger crystals with less MC defects19. Washing UiO-66 has been observed to increase defectivity, most likely due to exchange of hydrolysed linkers with solvent111. The underlying dynamic nature of MOFs must be reconciled with the long-term stability of engineered defect landscapes, particularly when intended operating conditions are likely to expedite structural evolution.

Chemists have already revised the classical MOF to include myriad defects in the crystal lattice. Perhaps this revision does not go far enough. If one considers the continuous rotation of linker functional groups, dynamic coordination chemistry, phonon modes, guest responsive behaviour (such as breathing, gate opening etc.) as well as the motion of guests colliding and interacting with the framework themselves, the lattice is not only imperfect but an evolving, heaving kaleidoscope of molecular activity. Routine characterisation techniques are blind to such local dynamics and their influence on defectivity. Indeed time was recently posited as a fourth dimension in which MOF chemistry can be intentionally engineered128. This necessitates that framework materials be probed with techniques that can provide a time-resolved understanding of dynamic molecular processes63,76,94,129,130. Steps have already been taken in this direction. Ultra-fast spectroscopy experiments coupled with molecular dynamics simulations have, for instance, uncovered the surprising picosecond rearrangement of hydrogen bonding networks involving MOF-pore confined water molecules131. Solid-state ultrafast magic-angle spinning 19F NMR has determined the metal-linker exchange rates in Zn(II) coordination polymers to be on the order of 3 × 104 s−1 at room temperature73. The metal-ligand dynamics responsible for liquid MOF formation, are known to occur on the order of picoseconds on the basis of molecular simulations75. Evidently, characterisation and simulation tools required to elucidate the dynamics underpinning defect propagation exist but their application is limited by the bespoke sample-specific experiments, specialist instrumentation and data analysis required. Our understanding of defectivity (among many other aspects of MOF chemistry) will remain incomplete until the underlying local dynamics are resolved. The application of experimental and computational expertise to this end must therefore be prioritised.

Our intention in raising these points is not to dissuade efforts to minimise defectivity or indeed, engineer it. Rather, we argue that these efforts are central to maximising the utility of MOFs in wide-ranging applications. Yet the transformative potential and ubiquity of dynamic bonding demands that more scrutiny be placed on the long-term stability of defect landscapes. Perhaps what is needed most is an interlaboratory study that assesses both defect reproducibility and stability in MOFs, focusing on the effects of routine processing on defect extent, type and distribution.

Future directions and concluding remarks

The preceding decade has seen defect engineering claim in MOF chemistry a similar eminence to what it has long enjoyed in semiconductor science. While MOFs spanning the full spectrum of defectivity, from amorphous to ‘defect-free’, find merit in specific applications, it is only by learning to reproducibly tune and characterise defectivity that chemists can fully realise the precision promised by reticular chemistry. A wealth of defect engineering research has proven beyond doubt that defect extent, type and spatial distribution to be tuned by judicious choice of synthetic parameters. Yet the exact role of temperature, stoichiometry and modulator remains unclear and often conflicting18. It is evident from existing work concerning the reproducibility of PCN frameworks that subtle factors wield significant influence over sample morphology and this conclusion likely extends to defectivity62. Delineating these relationships is a challenging task well suited to large-scale interlaboratory studies.

Attached to the question of reproducibility is the difficulty in characterising and consistently reporting defectivity. Despite the historical significance of crystallography, defect characterisation requires that chemists look beyond diffraction and towards methodologies that probe local chemistry. MOF characterisation is therefore guided ever more by materials science fields that never enjoyed the luxury of crystallinity73,75,100,132. In this sense defect characterisation shares challenges with glass, liquid and heterometallic/multicomponent MOFs wherein the relationship between the spatial distribution of disordered molecular components and emerging properties is only revealed by sophisticated analysis72,133. The value of computational chemistry in this process - linking structural and physicochemical properties in framework materials – cannot be understated, especially where disorder is present. This role will grow as machine learning is increasingly adopted52,99,134,135,136,137. This evolution in computational and experimental techniques is well underway and will undoubtedly reveal new defect types and correlations in the future. All of this is not to diminish the extraordinary role crystallinity plays in the archetypal properties and conceptual elegance of extended framework materials, nor the insight crystallography provides MOF chemists76,138,139. Nonetheless, a crystal structure cannot capture the whole picture, which is textured with a vastly richer chemistry than the classical MOF lattice can convey.

That MOFs undergo facile linker/cation exchange68,140,141 and post-synthetic structural transitions to new crystalline142,143 or amorphous glass phases74 confirms that coordination bonds do not relinquish their dynamic nature when incorporated in extended framework materials. Yet the role of labile coordination bonds in propelling the evolution of defectivity in MOFs, including during crystallization, activation and solvent exchange remains underexplored63. While defectivity is routinely analysed in as-synthesised samples, the stability of defect landscapes under operating conditions must be established to confirm that properties imbued by defect engineering are retained. Considering the significant – often beneficial - impact defects have on physicochemical properties, the unintended effects of post-synthetic processing in shaping the defect landscape over time would seem just as important as synthetic parameters are in shaping the initial defectivity.

We emphasise again that by underscoring challenges surrounding defect characterisation, reproducibility, and stability our intention is to inspire rather than discourage further work in this vital field. Indeed, defectivity and dynamic bonding are part of an expansive and ongoing reimagination of MOFs. Inspiration can be found in the revolution underway in the field of structural biology where advanced Electron Cryomicroscopy enables time-resolved atomic-resolution snapshots to be obtained which capture the extraordinary dynamic properties from which biological function is derived144,145. Insight garnered from this transformative technology far exceeds traditional crystallographic or NMR based techniques, confirming that even within well-established fields opportunity remains to avail deeper understanding from emerging technologies. We posit that while the underlying dynamic processes in MOFs are challenging experimental subjects today, their effects should not evade our imagination. Based on the evidence available already, the role of dynamic metal-linker interactions cannot be overestimated in any attempt to conceptualise or engineer defectivity.

Much has been reaped from the fertile chemical landscape that MOFs present. Increasingly, advancement has stemmed from embracing - and exploiting - the imperfections and dynamic properties of the crystalline lattice. The ascendency of glass MOFs is the ultimate manifestation of this transformation74,75,100. While the popular description of MOFs emphasises crystalline order and reticular synthesis; it is increasingly evident that imperfections grant access to new layers of chemical complexity and extraordinary opportunity.

References

Furukawa, H., Cordova, K. E., O’Keeffe, M. & Yaghi, O. M. The chemistry and applications of metal-organic frameworks. Science 341, 974–985 (2013).

Yaghi, O. M. et al. Reticular synthesis and the design of new materials. Nature 423, 705–714 (2003).

Morris, R. E. & Brammer, L. Coordination change, lability and hemilability in metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 5444–5462 (2017).

Obeso, J. L. et al. The role of dynamic metal-ligand bonds in metal-organic framework chemistry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 496, 215403 (2023).

Svensson Grape, E., Davenport, A. M. & Brozek, C. K. Dynamic metal-linker bonds in metal–organic frameworks. Dalt. Trans. 53, 1935–1941 (2024).

Allendorf, M. D., Stavila, V., Witman, M., Brozek, C. K. & Hendon, C. H. What Lies beneath a Metal–Organic Framework Crystal Structure? New Design Principles from Unexpected Behaviors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 6705–6723 (2021).

Queisser, H. J. & Haller, E. E. Defects in Semiconductors: Some Fatal, Some Vital. Science 281, 945–950 (1998).

Bouzerar, G., Thébaud, S., Pecorario, S. & Adessi, C. Drastic effects of vacancies on phonon lifetime and thermal conductivity in graphene. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 32, 295702 (2020).

Protik, N. H., Carrete, J., Katcho, N. A., Mingo, N. & Broido, D. Ab initio study of the effect of vacancies on the thermal conductivity of boron arsenide. Phys. Rev. B 94, 045207 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. Photoinduced Charge-Carrier Generation in Epitaxial MOF Thin Films: High Efficiency as a Result of an Indirect Electronic Band Gap? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 7441–7445 (2015).

Thornton, A. W., Babarao, R., Jain, A., Trousselet, F. & Coudert, F. X. Defects in metal–organic frameworks: a compromise between adsorption and stability? Dalt. Trans. 45, 4352–4359 (2016).

Burtch, N. C., Heinen, J., Bennett, T. D., Dubbeldam, D. & Allendorf, M. D. Mechanical Properties in Metal–Organic Frameworks: Emerging Opportunities and Challenges for Device Functionality and Technological Applications. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704124 (2018).

Rogge, S. M. J. et al. Thermodynamic Insight in the High-Pressure Behavior of UiO-66: Effect of Linker Defects and Linker Expansion. Chem. Mat. 28, 5721–5732 (2016).

Wang, B., Ying, P. & Zhang, J. Effects of Missing Linker Defects on the Elastic Properties and Mechanical Stability of the Metal–Organic Framework HKUST-1. J. Phys. Chem. C. 127, 2533–2543 (2023).

Müller, K. et al. Defects as Color Centers: The Apparent Color of Metal–Organic Frameworks Containing Cu2+-Based Paddle-Wheel Units. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 37463–37467 (2017). This work showed that the blue colour associated with the prototytpical framework HKUST-1 arrises not from the Cu-paddlewheel motif upon which its structure is based, but instead from defects.

Siddiqui, S. A., Prado-Roller, A. & Shiozawa, H. Room temperature synthesis of a luminescent crystalline Cu–BTC coordination polymer and metal–organic framework. Mater. Adv. 3, 224–231 (2022).

Sannes, D. K., Øien-Ødegaard, S., Aunan, E., Nova, A. & Olsbye, U. Quantification of Linker Defects in UiO-Type Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Mat. 35, 3793–3800 (2023).

Cox, C. S., Slavich, E., Macreadie, L. K., McKemmish, L. K. & Lessio, M. Understanding the Role of Synthetic Parameters in the Defect Engineering of UiO-66: A Review and Meta-analysis. Chem. Mat. 35, 3057–3072 (2023). This work analyses the role of synthetic parameters in UiO-66 defect engineering, highlighting the often conflicting role of synthetic parameters in determininng defectivity.

Liu, L. et al. Imaging defects and their evolution in a metal–organic framework at sub-unit-cell resolution. Nat. Chem. 11, 622–628 (2019).

Valenzano, L. et al. Disclosing the Complex Structure of UiO-66 Metal Organic Framework: A Synergic Combination of Experiment and Theory. Chem. Mat. 23, 1700–1718 (2011). This study was the first to explore the presence of missing linker defects in UiO-66.

Cliffe, M. J. et al. Correlated defect nanoregions in a metal–organic framework. Nat. Commun. 5, 4176 (2014). This study was the first to reveal the presence of missing cluster defects in UiO-66.

Liu, L., Zhang, D., Zhu, Y. & Han, Y. Bulk and local structures of metal–organic frameworks unravelled by high-resolution electron microscopy. Commun. Chem. 3, 99 (2020).

Moore, S. C., Smith, M. R., Trettin, J. L., Yang, R. A. & Sarazen, M. L. Kinetic Impacts of Defect Sites in Metal–Organic Framework Catalysts under Varied Driving Forces. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 1397–1407 (2023).

Fang, Z., Bueken, B., De Vos, D. E. & Fischer, R. A. Defect-Engineered Metal–Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 7234–7254 (2015).

Feng, Y., Chen, Q., Jiang, M. & Yao, J. Tailoring the Properties of UiO-66 through Defect Engineering: A Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 58, 17646–17659 (2019).

Jrad, A. et al. Critical Role of Defects in UiO-66 Nanocrystals for Catalysis and Water Remediation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 18698–18720 (2023).

Wu, H., Yildirim, T. & Zhou, W. Exceptional Mechanical Stability of Highly Porous Zirconium Metal–Organic Framework UiO-66 and Its Important Implications. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 925–930 (2013).

Vervoorts, P., Stebani, J., Méndez, A. S. J. & Kieslich, G. Structural Chemistry of Metal–Organic Frameworks under Hydrostatic Pressures. ACS Mater. Lett. 3, 1635–1651 (2021).

Hobday, C. L. et al. A Computational and Experimental Approach Linking Disorder, High-Pressure Behavior, and Mechanical Properties in UiO Frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 2401–2405 (2016).

Rogge, S. M. J. et al. Charting the Metal-Dependent High-Pressure Stability of Bimetallic UiO-66 Materials. ACS Mater. Lett. 2, 438–445 (2020).

Jajko, G. et al. Defect-induced tuning of polarity-dependent adsorption in hydrophobic–hydrophilic UiO-66. Commun. Chem. 5, 120 (2022).

Halder, A. et al. Enhancing Dynamic Spectral Diffusion in Metal–Organic Frameworks through Defect Engineering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 1072–1082 (2023).

Islamov, M., Boone, P., Babaei, H., McGaughey, A. J. H. & Wilmer, C. E. Correlated missing linker defects increase thermal conductivity in metal–organic framework UiO-66. Chem. Sci. 14, 6592–6600 (2023).

Islamov, M., Babaei, H. & Wilmer, C. E. Influence of Missing Linker Defects on the Thermal Conductivity of Metal–Organic Framework HKUST-1. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 56172–56177 (2020). This study employed molecular dynamics simualtions to reveal the substantiall reduction in thermal conductivity associated with increased defectivity.

Lázaro, I. A., Popescu, C. & Cirujano, F. G. Controlling the molecular diffusion in MOFs with the acidity of monocarboxylate modulators. Dalt. Trans. 50, 11291–11299 (2021).

Mautschke, H. H., Drache, F., Senkovska, I., Kaskel, S. & Llabrés i Xamena, F. X. Catalytic properties of pristine and defect-engineered Zr-MOF-808 metal organic frameworks. Catal. Sci. Technol. 8, 3610–3616 (2018).

Kozachuk, O. et al. Multifunctional, Defect-Engineered Metal–Organic Frameworks with Ruthenium Centers: Sorption and Catalytic Properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 7058–7062 (2014).

Korzyński, M. D., Consoli, D. F., Zhang, S., Román-Leshkov, Y. & Dincă, M. Activation of Methyltrioxorhenium for Olefin Metathesis in a Zirconium-Based Metal–Organic Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 6956–6960 (2018).

Vermoortele, F. et al. Synthesis Modulation as a Tool To Increase the Catalytic Activity of Metal–Organic Frameworks: The Unique Case of UiO-66(Zr). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11465–11468 (2013).

Wang, W. et al. Interplay of Electronic and Steric Effects to Yield Low-Temperature CO Oxidation at Metal Single Sites in Defect-Engineered HKUST-1. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 10514–10518 (2020).

Xue, Z. et al. Missing-linker metal-organic frameworks for oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 10, 5048 (2019).

Feng, X. et al. Generating Catalytic Sites in UiO-66 through Defect Engineering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 60715–60735 (2021).

Liang, W. et al. Linking defects, hierarchical porosity generation and desalination performance in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Sci. 9, 3508–3516 (2018).

Niu, J. et al. Defect Engineering of Low-Coordinated Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) for Improved CO2 Access and Capture. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 31664–31674 (2023).

Wu, H. et al. Unusual and Highly Tunable Missing-Linker Defects in Zirconium Metal–Organic Framework UiO-66 and Their Important Effects on Gas Adsorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 10525–10532 (2013).

Abánades Lázaro, I., Wells, C. J. R. & Forgan, R. S. Multivariate Modulation of the Zr MOF UiO-66 for Defect-Controlled Combination Anticancer Drug Delivery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 5211–5217 (2020).

Forse, A. C. et al. Unexpected Diffusion Anisotropy of Carbon Dioxide in the Metal–Organic Framework Zn2(dobpdc). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 1663–1673 (2018).

Fu, Y. et al. Solvent-derived defects suppress adsorption in MOF-74. Nat. Commun. 14, 2386 (2023).

Choi, J., Lin, L.-C. & Grossman, J. C. Role of Structural Defects in the Water Adsorption Properties of MOF-801. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 5545–5552 (2018).

Barin, G. et al. Defect Creation by Linker Fragmentation in Metal–Organic Frameworks and Its Effects on Gas Uptake Properties. Inorg. Chem. 53, 6914–6919 (2014).

Burtch, N. C. et al. Negative Thermal Expansion Design Strategies in a Diverse Series of Metal–Organic Frameworks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1904669 (2019).

Wu, Y., Duan, H. & Xi, H. Machine Learning-Driven Insights into Defects of Zirconium Metal–Organic Frameworks for Enhanced Ethane–Ethylene Separation. Chem. Mat. 32, 2986–2997 (2020).

Cliffe, M. J., Hill, J. A., Murray, C. A., Coudert, F.-X. & Goodwin, A. L. Defect-dependent colossal negative thermal expansion in UiO-66(Hf) metal–organic framework. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 11586–11592 (2015).

Chen, Z. et al. Node Distortion as a Tunable Mechanism for Negative Thermal Expansion in Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 268–276 (2023).

Krause, S. et al. Impact of Defects and Crystal Size on Negative Gas Adsorption in DUT-49 Analyzed by In Situ 129Xe NMR Spectroscopy. Chem. Mat. 32, 4641–4650 (2020).

Feng, L., Wang, K.-Y., Day, G. S., Ryder, M. R. & Zhou, H.-C. Destruction of Metal–Organic Frameworks: Positive and Negative Aspects of Stability and Lability. Chem. Rev. 120, 13087–13133 (2020).

Kim, Y. et al. Hydrolytic Transformation of Microporous Metal–Organic Frameworks to Hierarchical Micro- and Mesoporous MOFs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 13273–13278 (2015).

Liu, G. et al. Eliminating lattice defects in metal–organic framework molecular-sieving membranes. Nat. Mater. 22, 769–776 (2023).

Iacomi, P. et al. Role of Structural Defects in the Adsorption and Separation of C3 Hydrocarbons in Zr-Fumarate-MOF (MOF-801). Chem. Mat. 31, 8413–8423 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. Enhanced Separation of Butane Isomers via Defect Control in a Fumarate/Zirconium-Based Metal Organic Framework. Langmuir 34, 14546–14551 (2018).

Idrees, K. B. et al. Tailoring Pore Aperture and Structural Defects in Zirconium-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks for Krypton/Xenon Separation. Chem. Mat. 32, 3776–3782 (2020).

Boström, H. L. B. et al. How reproducible is the synthesis of Zr–porphyrin metal–organic frameworks? An interlaboratory study. Adv. Mater. 36, 2304832 (2023).

Hajek, J. et al. On the intrinsic dynamic nature of the rigid UiO-66 metal–organic framework. Chem. Sci. 9, 2723–2732 (2018).

Fabrizio, K., Andreeva, A. B., Kadota, K., Morris, A. J. & Brozek, C. K. Guest-dependent bond flexibility in UiO-66, a “stable” MOF. Chem. Commun. 59, 1309–1312 (2023).

Andreeva, A. B. et al. Soft Mode Metal-Linker Dynamics in Carboxylate MOFs Evidenced by Variable-Temperature Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 19291–19299 (2020).

Wang, J.-H. et al. Solvent-Assisted Metal Metathesis: A Highly Efficient and Versatile Route towards Synthetically Demanding Chromium Metal–Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 6478–6482 (2017).

Burnett, B. J., Barron, P. M., Hu, C. & Choe, W. Stepwise Synthesis of Metal–Organic Frameworks: Replacement of Structural Organic Linkers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 9984–9987 (2011).

Fei, H., Cahill, J. F., Prather, K. A. & Cohen, S. M. Tandem Postsynthetic Metal Ion and Ligand Exchange in Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks. Inorg. Chem. 52, 4011–4016 (2013).

Tian, Y. et al. Synthesis and structural characterization of a single-crystal to single-crystal transformable coordination polymer. Dalt. Trans. 43, 1519–1523 (2014).

Sato, H. et al. Self-Accelerating CO Sorption in a Soft Nanoporous Crystal. Science 343, 167–170 (2014).

Sen, S. et al. Cooperative Bond Scission in a Soft Porous Crystal Enables Discriminatory Gate Opening for Ethylene over Ethane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 18313–18321 (2017).

Sikma, R. E., Butler, K. S., Vogel, D. J., Harvey, J. A. & Sava Gallis, D. F. Quest for Multifunctionality: Current Progress in the Characterization of Heterometallic Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 5715–5734 (2024).

Kurihara, T. et al. Three-Dimensional Metal–Organic Network Glasses from Bridging MF62– Anions and Their Dynamic Insights by Solid-State NMR. Inorg. Chem. 61, 16103–16109 (2022).

Bennett, T. D. & Horike, S. Liquid, glass and amorphous solid states of coordination polymers and metal–organic frameworks. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 431–440 (2018).

Gaillac, R. et al. Liquid metal–organic frameworks. Nat. Mater. 16, 1149–1154 (2017).

Kang, J. et al. Dynamic three-dimensional structures of a metal–organic framework captured with femtosecond serial crystallography. Nat. Chem. 16, 693–699 (2024).

Winarta, J. et al. A Decade of UiO-66 Research: A Historic Review of Dynamic Structure, Synthesis Mechanisms, and Characterization Techniques of an Archetypal Metal–Organic Framework. Cryst. Growth Des. 20, 1347–1362 (2020).

Shaikh, S. M. et al. Synthesis and Defect Characterization of Phase-Pure Zr-MOFs Based on Meso-tetracarboxyphenylporphyrin. Inorg. Chem. 58, 5145–5153 (2019).

Driscoll, D. M. et al. Characterization of Undercoordinated Zr Defect Sites in UiO-66 with Vibrational Spectroscopy of Adsorbed CO. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 14582–14589 (2018).

Yin, J. et al. Molecular identification and quantification of defect sites in metal-organic frameworks with NMR probe molecules. Nat. Commun. 13, 5112 (2022).

Sha, F. et al. Probing Structural Imperfections: Protein-Aided Defect Characterization in Metal–Organic Frameworks. ACS Mater. Lett., 1396–1403, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsmaterialslett.4c00199 (2024).

Klet, R. C., Liu, Y., Wang, T. C., Hupp, J. T. & Farha, O. K. Evaluation of Brønsted acidity and proton topology in Zr- and Hf-based metal–organic frameworks using potentiometric acid–base titration. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 1479–1485 (2016).

Fang, Z. et al. Structural Complexity in Metal–Organic Frameworks: Simultaneous Modification of Open Metal Sites and Hierarchical Porosity by Systematic Doping with Defective Linkers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9627–9636 (2014).

Heinz, W. R. et al. Thermal Defect Engineering of Precious Group Metal–Organic Frameworks: A Case Study on Ru/Rh-HKUST-1 Analogues. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 40635–40647 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Defect-Engineered Metal–Organic Frameworks: A Thorough Characterization of Active Sites Using CO as a Probe Molecule. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 593–601 (2021).

Liang, A. J. et al. A Site-Isolated Rhodium−Diethylene Complex Supported on Highly Dealuminated Y Zeolite: Synthesis and Characterization. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 24236–24243 (2005).

Perez-Aguilar, J. E., Chen, C.-Y., Hughes, J. T., Fang, C.-Y. & Gates, B. C. Isostructural Atomically Dispersed Rhodium Catalysts Supported on SAPO-37 and on HY Zeolite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 11474–11485 (2020).

Sánchez, F., Iglesias, M., Corma, A. & del Pino, C. New rhodium complexes anchored on silica and modified Y-zeolite as efficient catalysts for hydrogenation of olefins. J. Mol. Cat. 70, 369–379 (1991).

Johnstone, D. N. et al. Direct Imaging of Correlated Defect Nanodomains in a Metal–Organic Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 13081–13089 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Real-Space Imaging of the Molecular Changes in Metal–Organic Frameworks under Electron Irradiation. ACS Nano 17, 4740–4747 (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. Local Structure Evolvement in MOF Single Crystals Unveiled by Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy. Chem. Mat. 32, 4966–4972 (2020).

Braglia, L. et al. Catching the Reversible Formation and Reactivity of Surface Defective Sites in Metal–Organic Frameworks: An Operando Ambient Pressure-NEXAFS Investigation. j. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 9182–9187 (2021).

Romero-Muñiz, I. et al. Revisiting Vibrational Spectroscopy to Tackle the Chemistry of Zr6O8 Metal-Organic Framework Nodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 27040–27047 (2022).

Cerasale, D. J., Ward, D. C. & Easun, T. L. MOFs in the time domain. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 9–30 (2022).

Sapnik, A. F. et al. Mapping nanocrystalline disorder within an amorphous metal–organic framework. Commun. Chem. 6, 92 (2023).

Tan, K. et al. Defect Termination in the UiO-66 Family of Metal–Organic Frameworks: The Role of Water and Modulator. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 6328–6332 (2021).

McDonnell, R. P. et al. Anomalous Infrared Intensity Behavior of Acetonitrile Diffused into UiO-67. Chem. Mat. 35, 8827–8839 (2023).

Yang, D. & Gates, B. C. Elucidating and Tuning Catalytic Sites on Zirconium- and Aluminum-Containing Nodes of Stable Metal–Organic Frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 1982–1991 (2021).

Formalik, F., Shi, K., Joodaki, F., Wang, X. & Snurr, R. Q. Exploring the Structural, Dynamic, and Functional Properties of Metal-Organic Frameworks through Molecular Modeling. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2308130, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202308130 (2023).

Hou, J. et al. Halogenated Metal–Organic Framework Glasses and Liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 3880–3890 (2020).

Yang, L.-M., Ganz, E., Svelle, S. & Tilset, M. Computational exploration of newly synthesized zirconium metal–organic frameworks UiO-66, -67, -68 and analogues. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2, 7111–7125 (2014).

Dissegna, S. et al. Tuning the Mechanical Response of Metal–Organic Frameworks by Defect Engineering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 11581–11584 (2018).

Lamaire, A., Wieme, J., Hoffman, A. E. J. & Van Speybroeck, V. Atomistic insight in the flexibility and heat transport properties of the stimuli-responsive metal–organic framework MIL-53(Al) for water-adsorption applications using molecular simulations. Faraday Discuss. 225, 301–323 (2021).

Wieme, J. et al. Thermal Engineering of Metal–Organic Frameworks for Adsorption Applications: A Molecular Simulation Perspective. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 38697–38707 (2019).

Babaei, H. et al. Observation of reduced thermal conductivity in a metal-organic framework due to the presence of adsorbates. Nat. Commun. 11, 4010 (2020).

Sørensen, S. S. et al. Metal–Organic Framework Glasses Possess Higher Thermal Conductivity than Their Crystalline Counterparts. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 18893–18903 (2020).

Andreeva, A. B. et al. Cooperativity and Metal–Linker Dynamics in Spin Crossover Framework Fe(1,2,3-triazolate)2. Chem. Mat. 33, 8534–8545 (2021).

St. Petkov, P. et al. Defects in MOFs: A Thorough Characterization. ChemPhysChem 13, 2025–2029 (2012).

Krause, S. et al. The role of temperature and adsorbate on negative gas adsorption transitions of the mesoporous metal–organic framework DUT-49. Faraday Discuss. 225, 168–183 (2021).

Koschnick, C. et al. Understanding disorder and linker deficiency in porphyrinic zirconium-based metal–organic frameworks by resolving the Zr8O6 cluster conundrum in PCN-221. Nat. Commun. 12, 3099 (2021).

Shearer, G. C. et al. Tuned to Perfection: Ironing Out the Defects in Metal–Organic Framework UiO-66. Chem. Mat. 26, 4068–4071 (2014).

Lee, S. J. et al. Multicomponent Metal–Organic Frameworks as Defect-Tolerant Materials. Chem. Mat. 28, 368–375 (2016).

Xiong, S. et al. Impact of Labile Ligands on Catalyst Initiation and Chain Propagation in Ni-Catalyzed Ethylene/Acrylate Copolymerization. ACS Catal. 13, 5000–5006 (2023).

Huang, Y. et al. Ligand coordination- and dissociation-induced divergent allylic alkylations using alkynes. Chem 7, 812–826 (2021).

Yuan, S. et al. Stable Metal–Organic Frameworks: Design, Synthesis, and Applications. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704303 (2018).

McHugh, L. N. et al. Hydrolytic stability in hemilabile metal–organic frameworks. Nat. Chem. 10, 1096–1102 (2018).

Haigis, V., Coudert, F.-X., Vuilleumier, R., Boutin, A. & Fuchs, A. H. Hydrothermal Breakdown of Flexible Metal–Organic Frameworks: A Study by First-Principles Molecular Dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 4365–4370 (2015).

Položij, M., Rubeš, M., Čejka, J. & Nachtigall, P. Catalysis by Dynamically Formed Defects in a Metal–Organic Framework Structure: Knoevenagel Reaction Catalyzed by Copper Benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxylate. ChemCatChem 6, 2821–2824 (2014).

Baumgartner, B., Mashita, R., Fukatsu, A., Okada, K. & Takahashi, M. Guest Alignment and Defect Formation during Pore Filling in Metal–Organic Framework Films. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202201725 (2022).

Peralta, R. A. et al. Engineering Catalysis within a Saturated In(III)-Based MOF Possessing Dynamic Ligand–Metal Bonding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 1410–1417 (2023).

Obeso, J. L. et al. Gas-phase organometallic catalysis in MFM-300(Sc) provided by switchable dynamic metal sites. Chem. Commun. 59, 3273–3276 (2023).

Lyu, P. et al. Ammonia Capture via an Unconventional Reversible Guest-Induced Metal-Linker Bond Dynamics in a Highly Stable Metal–Organic Framework. Chem. Mat. 33, 6186–6192 (2021).

Peralta, R. A. et al. Switchable Metal Sites in Metal–Organic Framework MFM-300(Sc): Lewis Acid Catalysis Driven by Metal–Hemilabile Linker Bond Dynamics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202210857 (2022).

Rayder, T. M. et al. Unveiling Unexpected Modulator-CO2 Dynamics within a Zirconium Metal–Organic Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 11195–11205 (2023).

Fabrizio, K. & Brozek, C. K. Size-Dependent Thermal Shifts to MOF Nanocrystal Optical Gaps Induced by Dynamic Bonding. Nano Lett. 23, 925–930 (2023).

Davenport, A. M. et al. Size-Dependent Spin Crossover and Bond Flexibility in Metal–Organic Framework Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 23692–23698 (2024).

Bueken, B. et al. Tackling the Defect Conundrum in UiO-66: A Mixed-Linker Approach to Engineering Missing Linker Defects. Chem. Mat. 29, 10478–10486 (2017).

Evans, J. D., Bon, V., Senkovska, I., Lee, H. C. & Kaskel, S. Four-dimensional metal-organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 11, 2690 (2020).

Ye, Q. et al. Photoinduced Dynamic Ligation in Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 101–105 (2024).

Nishida, J. et al. Structural dynamics inside a functionalized metal–organic framework probed by ultrafast 2D IR spectroscopy. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 111, 18442–18447 (2014).

Valentine, M. L., Yin, G., Oppenheim, J. J., Dincǎ, M. & Xiong, W. Ultrafast Water H-Bond Rearrangement in a Metal–Organic Framework Probed by Femtosecond Time-Resolved Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 11482–11487 (2023).

Hadjiivanov, K. I. et al. Power of Infrared and Raman Spectroscopies to Characterize Metal-Organic Frameworks and Investigate Their Interaction with Guest Molecules. Chem. Rev. 121, 1286–1424 (2021).

Lee, G. & Hwang, J. Direct Synthesis of Mixed-Metal Paddle-Wheel Metal–Organic Frameworks with Controlled Metal Ratios under Ambient Conditions. Inorg. Chem. 62, 19457–19465 (2023).

Vandenhaute, S., Cools-Ceuppens, M., DeKeyser, S., Verstraelen, T. & Van Speybroeck, V. Machine learning potentials for metal-organic frameworks using an incremental learning approach. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 19 (2023).

Tang, H., Duan, L. & Jiang, J. Leveraging Machine Learning for Metal–Organic Frameworks: A Perspective. Langmuir 39, 15849–15863 (2023).

Larionov, K. P. & Evtushok, V. Y. From Synthesis Conditions to UiO-66 Properties: Machine Learning Approach. Chem. Mat. 36, 4291–4302 (2024).

Allegretto, J. A., Onna, D., Bilmes, S. A., Azzaroni, O. & Rafti, M. Unified Roadmap for ZIF-8 Nucleation and Growth: Machine Learning Analysis of Synthetic Variables and Their Impact on Particle Size and Morphology. Chem. Mat. 36, 5814–5825 (2024).

Gonzalez, M. I. et al. Structural characterization of framework-gas interactions in the metal-organic framework Co2(dobdc) by in situ single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Chem. Sci. 8, 4387–4398 (2017).

Bloch, W. M., Champness, N. R. & Doonan, C. J. X-ray Crystallography in Open-Framework Materials. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 54, 12860–12867 (2015).

Karagiaridi, O., Bury, W., Mondloch, J. E., Hupp, J. T. & Farha, O. K. Solvent-Assisted Linker Exchange: An Alternative to the De Novo Synthesis of Unattainable Metal–Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 4530–4540 (2014).

Brozek, C. K. & Dincă, M. Cation exchange at the secondary building units of metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 5456–5467 (2014).

Kitaura, R. et al. Rational Design and Crystal Structure Determination of a 3-D Metal−Organic Jungle-Gym-like Open Framework. Inorg. Chem. 43, 6522–6524 (2004).

Lin, W. et al. Snapshots of Postsynthetic Modification in a Layered Metal–Organic Framework: Isometric Linker Exchange and Adaptive Linker Installation. Inorg. Chem. 60, 11756–11763 (2021).

Papasergi-Scott, M. M. et al. Time-resolved cryo-EM of G-protein activation by a GPCR. Nature 629, 1182–1191 (2024).

Mazhab-Jafari, M. T. & Rubinstein, J. L. Cryo-EM studies of the structure and dynamics of vacuolar-type ATPases. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600725 (2016).

Gutov, O. V., Hevia, M. G., Escudero-Adán, E. C. & Shafir, A. Metal–Organic Framework (MOF) Defects under Control: Insights into the Missing Linker Sites and Their Implication in the Reactivity of Zirconium-Based Frameworks. Inorg. Chem. 54, 8396–8400 (2015).

Shearer, G. C. et al. Defect Engineering: Tuning the Porosity and Composition of the Metal–Organic Framework UiO-66 via Modulated Synthesis. Chem. Mat. 28, 3749–3761 (2016).

Jiao, Y. et al. Heat-Treatment of Defective UiO-66 from Modulated Synthesis: Adsorption and Stability Studies. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 23471–23479 (2017).

DeStefano, M. R., Islamoglu, T., Garibay, S. J., Hupp, J. T. & Farha, O. K. Room-Temperature Synthesis of UiO-66 and Thermal Modulation of Densities of Defect Sites. Chem. Mat. 29, 1357–1361 (2017).

Epley, C. C., Love, M. D. & Morris, A. J. Characterizing Defects in a UiO-AZB Metal–Organic Framework. Inorg. Chem. 56, 13777–13784 (2017).

Cai, G. & Jiang, H.-L. A Modulator-Induced Defect-Formation Strategy to Hierarchically Porous Metal–Organic Frameworks with High Stability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 563–567 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. Improving Water-Treatment Performance of Zirconium Metal-Organic Framework Membranes by Postsynthetic Defect Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 37848–37855 (2017).

Chammingkwan, P. et al. Modulator-free approach towards missing-cluster defect formation in Zr-based UiO-66. RSC Adv. 10, 28180–28185 (2020).

Feng, X. et al. Engineering a Highly Defective Stable UiO-66 with Tunable Lewis- Brønsted Acidity: The Role of the Hemilabile Linker. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 3174–3183 (2020).

Feng, X. et al. Creation of Exclusive Artificial Cluster Defects by Selective Metal Removal in the (Zn, Zr) Mixed-Metal UiO-66. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 21511–21518 (2021).

Tan, T. T. Y. et al. UiO-66 metal organic frameworks with high contents of flexible adipic acid co-linkers. Chem. Commun. 58, 11402–11405 (2022).

Fu, G. et al. Enhanced Water Adsorption Performance of UiO-66 Modulated with p-Nitrobenzoic or p-Hydroxybenzoic Acid: Introduced Defects and Functional Groups. Inorg. Chem. 61, 17943–17950 (2022).

Tatay, S. et al. Synthetic control of correlated disorder in UiO-66 frameworks. Nat. Commun. 14, 6962 (2023).

Guo, Z., Liu, X., Che, Y. & Xing, H. Crystal-Defect-Induced Longer Lifetime of Excited States in a Metal–Organic Framework Photocatalyst to Enhance Visible-Light-Mediated CO2 Reduction. Inorg. Chem. 63, 13005–13013 (2024).

Xing, S. et al. Cluster–Cluster Co-Nucleation Induced Defective Polyoxometalate-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks for Efficient Tandem Catalysis. Small, 2400410, https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202400410.

Damacet, P., Hannouche, K., Gouda, A. & Hmadeh, M. Controlled Growth of Highly Defected Zirconium–Metal–Organic Frameworks via a Reaction–Diffusion System for Water Remediation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.3c16327 (2024).

Dai, S. et al. Highly defective ultra-small tetravalent MOF nanocrystals. Nat. Commun. 15, 3434 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Ruthenium Metal–Organic Frameworks with Different Defect Types: Influence on Porosity, Sorption, and Catalytic Properties. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 14297–14307 (2016).

Zhang, W. et al. Impact of Synthesis Parameters on the Formation of Defects in HKUST-1. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 925–931 (2017).

Müller, K. et al. Water as a modulator in the synthesis of surface-mounted metal–organic framework films of type HKUST-1. Dalt. Trans. 47, 16474–16479 (2018).

Doan, H. V., Sartbaeva, A., Eloi, J.-C., A. Davis, S. & Ting, V. P. Defective hierarchical porous copper-based metal-organic frameworks synthesised via facile acid etching strategy. Sci. Rep. 9, 10887 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. Defect Creation in Surface-Mounted Metal–Organic Framework Thin Films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 2655–2661 (2020).

Steenhaut, T., Grégoire, N., Barozzino-Consiglio, G., Filinchuk, Y. & Hermans, S. Mechanochemical defect engineering of HKUST-1 and impact of the resulting defects on carbon dioxide sorption and catalytic cyclopropanation. RSC Adv. 10, 19822–19831 (2020).

Rivera-Torrente, M., Filez, M., Meirer, F. & Weckhuysen, B. M. Multi-Spectroscopic Interrogation of the Spatial Linker Distribution in Defect-Engineered Metal–Organic Framework Crystals: The [Cu3(btc)2−(cydc)] Showcase. Chem. Eur. J. 26, 3614–3625 (2020).

Ferreira Sanchez, D. et al. Spatio-Chemical Heterogeneity of Defect-Engineered Metal–Organic Framework Crystals Revealed by Full-Field Tomographic X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 10032–10039 (2021).

Horiuchi, Y. et al. Linker defect engineering for effective reactive site formation in metal–organic framework photocatalysts with a MIL-125(Ti) architecture. J. Catal. 392, 119–125 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. Titanium-Oxo Cluster Assisted Fabrication of a Defect-Rich Ti-MOF Membrane Showing Versatile Gas-Separation Performance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202203663 (2022).

Shim, C. H., Oh, S., Lee, S., Lee, G. & Oh, M. Construction of defected MOF-74 with preserved crystallinity for efficient catalytic cyanosilylation of benzaldehyde. RSC Adv. 13, 8220–8226 (2023).

Lázaro, I. A., Almora-Barrios, N., Tatay, S., Popescu, C. & Martí-Gastaldo, C. Linker depletion for missing cluster defects in non-UiO metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Sci. 12, 11839–11844 (2021).

Lázaro, I. A., Almora-Barrios, N., Tatay, S. & Martí-Gastaldo, C. Effect of modulator connectivity on promoting defectivity in titanium–organic frameworks. Chem. Sci. 12, 2586–2593 (2021).

Lázaro, I. A. Rationalising the multivariate modulation of MUV-10 for the defect-introduction of multiple functionalised modulators. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 10466–10473 (2022).

Lázaro, I. A. et al. Tuning the Photocatalytic Activity of Ti-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks through Modulator Defect-Engineered Functionalization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 21007–21017 (2022).

Fan, Z. et al. Defect Engineering of Copper Paddlewheel-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks of Type NOTT-100: Implementing Truncated Linkers and Its Effect on Catalytic Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 37993–38002 (2020).

Han, R., Tymińska, N., Schmidt, J. R. & Sholl, D. S. Propagation of Degradation-Induced Defects in Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 6655–6666 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Radiation-Induced De Novo Defects in Metal–Organic Frameworks Boost CO2 Sorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 23651–23658 (2023).

Ahmad, M. et al. ZIF-8 Vibrational Spectra: Peak Assignments and Defect Signals. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 27887–27897 (2024).

Hardian, R. et al. Tuning the Properties of MOF-808 via Defect Engineering and Metal Nanoparticle Encapsulation. Chem. Eur. J. 27, 6804–6814 (2021).

Ye, G. et al. Boosting Catalytic Performance of MOF-808(Zr) by Direct Generation of Rich Defective Zr Nodes via a Solvent-Free Approach. Inorg. Chem. 62, 4248–4259 (2023).

Xu, C. et al. Direct visualisation of metal–defect cooperative catalysis in Ru-doped defective MOF-808. J. Mater. Chem. A 12, 19018–19028 (2024).

Le, H. V. et al. A sulfonate ligand-defected Zr-based metal–organic framework for the enhanced selective removal of anionic dyes. RSC Adv. 14, 16389–16399 (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. Tunable coordinative defects in UHM-3 surface-mounted MOFs for gas adsorption and separation: A combined experimental and theoretical study. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 207, 53–60 (2015).

He, S. et al. Competitive coordination strategy for the synthesis of hierarchical-pore metal–organic framework nanostructures. Chem. Sci. 7, 7101–7105 (2016).

Slater, B., Wang, Z., Jiang, S., Hill, M. R. & Ladewig, B. P. Missing Linker Defects in a Homochiral Metal–Organic Framework: Tuning the Chiral Separation Capacity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 18322–18327 (2017).

Yuan, S. et al. Exposed Equatorial Positions of Metal Centers via Sequential Ligand Elimination and Installation in MOFs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10814–10819 (2018).

Smolders, S. et al. A Titanium(IV)-Based Metal–Organic Framework Featuring Defect-Rich Ti-O Sheets as an Oxidative Desulfurization Catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 9160–9165 (2019).

Guo, C. et al. Precise regulation of defect concentration in MOF and its influence on photocatalytic overall water splitting. Nanoscale 14, 15316–15326 (2022).

Chetry, S. et al. Exploring Defect-Engineered Metal–Organic Frameworks with 1,2,4-Triazolyl Isophthalate and Benzoate Linkers. Inorg. Chem. 63, 10843–10853 (2024).

Cavka, J. H. et al. A New Zirconium Inorganic Building Brick Forming Metal Organic Frameworks with Exceptional Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 13850–13851 (2008).

Jakobsen, S. et al. Structural determination of a highly stable metal-organic framework with possible application to interim radioactive waste scavenging: Hf-UiO-66. Phys. Rev. B 86, 125429 (2012).

Acknowledgements

J.L.O. thanks CONAHCYT for the Ph.D. fellowship (1003953). R.A.P. thanks the Autonomous Metropolitan University-Iztapalapa, Mexico, for the financial support. We thank U. Winnberg (Euro Health) for scientific discussions and G. Ibarra-Winnberg for scientific encouragement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.S.P.V., J.L.O. and J.A.R. writing and conceptualization. R.A.P. writing, conceptualization, and organization. M.T.H. writing, conceptualization, and organization I.A.I. validated the discussion, and revised the paper. All authors contributed to reviewing and enhancing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications materials thanks Martina Lessio, Jin Zhang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jet-Sing Lee and John Plummer. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Portillo-Vélez, N.S., Obeso, J.L., de los Reyes, J.A. et al. Benefits and complexity of defects in metal-organic frameworks. Commun Mater 5, 247 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00691-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00691-1

This article is cited by

-

Uncapping energy transfer pathways in metal-organic frameworks through heterogeneous structures

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Harnessing the structural evolution of metal–organic frameworks under electrocatalytic conditions

Communications Chemistry (2025)