Abstract

The low ordering temperature of most non-collinear spiral magnets critically limits their implementation in devices. The layered perovskites RBaCuFeO5 are a rare case of frustrated oxide family that has raised great expectations as promising high-temperature spiral magnets and spin-driven multiferroic candidates. Though a non-conventional mechanism of ‘spiral order by disorder’ could account for the extraordinary thermal stability of their presumed spiral order, such order was alleged on the basis of non-conclusive neutron data on powder samples. Thus far, it has not yet received support from single-crystal studies able to lift the ambiguities of powder data. Here, a YBaCuFeO5 crystal has been grown with enough Cu/Fe disorder to stabilize the incommensurate magnetic phase up to TS ≈ 200 K. Utilizing spherical neutron polarimetry and single-crystal neutron diffraction, we unveil the features of its magnetic structures, demonstrating the non-collinear chiral nature of the magnetic domains in the singular incommensurate phase. It is thus finally proved that such phase is spiral in our crystal, and therefore also in those compositions of this perovskite family where TS values well above room temperature have been reported. Yet, this study also illustrates critical features of relevance to the search for high-temperature magnetoelectric response induced by the spiral phase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chiral magnets form a rare class of frustrated compounds that attract a lot of attention owing to their technologically promising properties, associated to a variety of chirality-sensitive physical responses. In non-centrosymmetric chiral magnets, the competition of magnetic anisotropy, ferromagnetic exchange, and Dzyaloshinsky-Moriya (DM) interactions can produce exotic magnetic structures such as skyrmions1. Spin textures with magnetic chirality can also occur in centrosymmetric non-chiral crystal lattices2. Among the exciting properties realized in chiral magnetic systems the magnetoelectricity and the multiferroicity are two of the most attractive. In frustrated magnets, the phases with noncollinear spiral magnetic order are particularly promising because the cycloidal spin ordering breaks space- and time-inversion symmetry and can induce spontaneous polarization through the inverse DM mechanism in presence of spin-orbit coupling3. In spiral-induced multiferroics the common origin of the polarization and the spiral magnetic order assures a substantial coupling between them. Although they are an ideal platform for the pursuit of strong magnetoelectric coupling, most of the chiral (spiral) magnetoelectric multiferroics investigated in recent years are geometrically frustrated magnets with typical spiral transition temperatures TS < 50 K. Moreover, very few helical magnets exhibit ferromagnetic components coupled to the helix, therefore the manipulation of the polarization direction entangled with the spiral orientation is not facilitated. Spiral magnets at ambient temperature are hence very rare, restricting their implementation in low-power magnetoelectric and spintronic devices. Exceptionally, there are some examples of chiral hexaferrites that retain a longitudinal conical order even above room temperature and which can be turned into a transverse ferroelectric state when a low magnetic field is applied off the screw axis4,5. The magnetization (M) switching by electrical field (E) (as well as the nearly full polarization, P, reversal by magnetic field, H) has been demonstrated close to room temperature in single crystals of selected Y-type hexaferrites4,6. Moreover, in Y-type crystals of specific compositions giant magnetoelectric effects have been realized, achieving exceptionally large magnetoelectric coefficients (direct and converse), although the largest M switching by E is obtained at cryogenic temperatures. These works on single-phase crystals of conical Y-type hexaferrites are excellent examples of how magnetoelectric effects can be enhanced by tuning magnetic symmetry. They have established a clear correlation between the magnitude of the magnetoelectric response and the orientation (symmetry) of the incommensurate conical spin ordering7. High temperature (T ) magnetoelectric coupling and multiferroicity are also being investigated in other types of hexaferrites triggered by noncollinear (spiral) magnetic orders8.

The layered perovskites RBaCuFeO5 are also a rare exception where it has been argued that spiral magnetic order (TS) can persist close to and even beyond room temperature9,10,11. The basic structure of YBaCuFeO5 (YBCFO) consists of [CuFeO9] bilayers of corner-sharing Cu2+O5 and Fe3+O5 square pyramids that extend parallel to the ab plane. Cations at the A site of the oxygen-deficient YBaCuFeO5 double perovskite (Y3+, Ba2+) order in alternating layers perpendicular to the c axis. Y3+ layers separate the CuFeO9 bilayers and accommodate the oxygen vacancies. Finally, the Ba2+ ions are located within the bilayer spacing. There are two non-equivalent sites for B-atoms (Cu and Fe) with pyramidal coordination in the P4mm unit cell: M1 (upper, Cu-rich position) and M2 (lower, Fe-rich position). Another unique feature of YBCFO is the exceptional possibility to tune the spiral ordering temperature by more than 350 K by tuning the level of Cu/Fe disorder in the structure10,12. Fe/Cu disorder is parametrized here as in ref. 12, by the occupancy nd, which is defined as the fractional occupancy obtained from diffraction of the minority (*) B ions in the upper or lower pyramids, indistinctly [i.e., nd = Occ Fel*= Occ Cu2*, see also Supplementary Table 1].

In powder YBCFO samples we found (ref. 12) that \({T}_{{\rm{S}}}[{\rm{K}}]=-62+2610{\rm{\cdot }}{q}_{{\rm{S}}}\), where the incommensurability qS of the spiral was linearly correlated to disorder (nd) (qS = −0.025(31) + 0.445(78)·nd12). In this average description nd = 0.5 corresponds to a random Fe/Cu cation distribution at the B-site (0 < nd < 0.5)). This possibility to tune the spiral ordering temperature by enhancing frustration (simply through the fraction of Fe/Cu antisites, chemical disorder) can be understood in the context of a non-conventional mechanism that produces “spiral order by disorder”. In the model developed by Scaramucci et al. for non frustrated layered lattices of classical XY ferromagnets13, nearest-neighbor interactions can produce high-TS spiral ordering when a sufficiently large fraction of equally oriented ferromagnetic bonds are substituted by random impurity bonds presenting sufficiently strong antiferromagnetic coupling. Because of the disorder, this is realized here by the presence of a certain fraction of Fe2O9 bipyramids14.

Several works have reported fairly large electric polarization in polycrystalline samples of YBCFO9,15,16, but not yet on single crystals where investigations are still very scarce. The spiral phase in YBCFO has raised great expectations making the RBaCuFeO5 family of layered perovskites one of the most promising spin-driven multiferroic candidates. The polarization attributed to the spiral phase in ceramic RBaCuFeO5 samples9,15,16 is a subject of debate. Although Kundys et al.15 justified a polarization parallel to c due to the formation of dipole moments in the bipyramids, most of reports suggest a cycloidal-induced polarization perpendicular to c, the direction of the incommensurate magnetic modulation.

In a YBCFO crystal studied by Lai et al.17 (TS ∼ 175 K), no signs of polarization were seen below TS, which was attributed to a null cycloidal component in the horizontal spiral model derived from the Rietveld fit of neutron powder diffraction (NPD) data from a powdered single crystal. In Ref. 12 we reported a description of the evolution of the spiral orientation with the level of disorder as obtained from neutron powder diffraction in ceramic YBCFO samples. Other reports also suggest changes in the spiral inclination with variables such as qS, TS, the disorder, or some interatomic distances10,11,12,17,18,19. However, it is important to notice that these reports are experimental and based on NPD, while there are no theoretical predictions yet on possible correlations between the spiral inclination and the mentioned variables.

In previous works, particularly those reporting spontaneous polarization, the spiral solution - compatible with neutron data from powder samples- was preferred because, contrarily to the non-spiral solution, it could account for the presence of polarization. After the synthesis of the material in 198820, Caignaert et al. 21 reported an early NPD study unveiling that magnetic order below TN2 was incommensurate. All subsequent reports (based on powder diffraction) assumed a spiral phase in YBCFO. A critical issue is that both, a sinusoidal and a spiral magnetic order can account for the magnetic intensities in neutron powder diffraction patterns of the incommensurate phase. Certainly, it has been unambiguously recognized (e.g., in refs. 9,12) that in this layered structure, the two different magnetic models (one collinear, the second noncollinear) perfectly reproduce the experimental neutron patterns from powdered samples. This ambiguity is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1.

In view of that both, spin modulated and spiral orders are compatible with the neutron magnetic intensities from polycrystalline samples, it is essential to investigate the incommensurate order in YBCFO by single-crystal neutron diffraction. Such a study is still lacking (even in ref. 17, which reports a crystal, but where magnetic refinements were done on powder data). This work is aimed at filling that gap, investigating a high-quality YBCFO crystal by means of single-crystal neutron diffraction (SCND) and spherical neutron polarimetry (SNP). With the objective of answering the open questions that still persist in this important family of perovskites. In this study, we have intended to give a definitive conclusive answer to these questions: Which is the nature of the incommensurate spin order in RBaCuFeO5 perovskites? Is it non-collinear? Is the incommensurate ordering a chiral magnetic phase? Is YBCFO hosting cycloidal order? The answer to these questions has a major impact on the potential interest and promising opportunities of these exceptional family of frustrated magnets.

Results

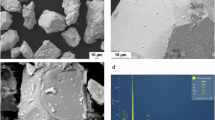

Single-crystal and magnetometry

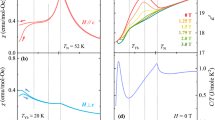

The limitations of the neutron powder diffraction to discern between complex magnetic orders are well known (see e.g., ref. 22). Unlike single-crystal neutron diffraction, where reflections are collected individually, the averaging inherent to neutron powder diffraction entails limitations that in the case of cycloidal or helical orders may prevent its complete description. In a powder diffraction pattern, the entire reciprocal space is projected onto one dimension, as a function of 2θ. So, all reflections with the same 2θ angle contribute to a unique peak of the powder pattern, whose intensity results from different contributing reflections. In the case of magnetic structures, in addition to projecting onto a single dimension, only the perpendicular component of the magnetic structure factor to the scattering vector contributes to the intensity of each reflection. Disposing of single crystals allows to overcome the limitation associated to the one-dimensional projection. Single crystal samples of the layered perovskite YBCFO were grown by the traveling solvent floating zone (TSFZ) method, using a four-mirror optical furnace (Fig. 1a). Crystal quality was assessed using neutron Laue images and single-crystal neutron diffraction (Supplementary Fig. 2). The elemental composition of the sample was determined via Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES), which confirmed with great accuracy that there is no deviation from the ideal molar ratio within the error margins [Y:Ba:Cu:Fe = 1.000(14):1.000(12):1.008(29):1.007(33)]. The magnetic susceptibility (χi(T)=Mi/Hi) of the crystal, measured in field-cooling conditions (FC) between 10 and 520 K is shown in Fig. 1b. The temperature scans of dc magnetization (M) measured parallel to the c and the a axes show different trends. A clear kink is observed at TN2 ≈ 195 K in the magnetization parallel to the ab plane, whereas marked anomalies are not visible in the evolution of χc(T) (H//c). A marked decrease in χa(T) takes place below the kink associated with TN2 which is not observed in χc(T). At low temperatures the magnetization measured along a is smaller than that perpendicular to the plane (χa << χc). As shown below, neutron scattering confirmed that the anomaly at 195 K denotes the emergence of the incommensurate magnetic order.

a Sketch and dimensions of the crystal along their (a, b, and c) axes. The crystal orientation respect to the orthogonal x, y, and z directions defined in the text for the spherical neutron polarimetry measurements (x is parallel to the scattering vector Q and z vertical) is shown. The [1 −1 0] axis was oriented vertically to keep [0 0 1] and [1 1 1] directions in the horizontal x-y plane. b Magnetic susceptibility (χ=M/H) along a and c axes (FC, H = 1 kOe). The two anomalies associated with the onset of the antiferromagnetic orders are shown at TN1 = 460 K and TN2 = 195 K.

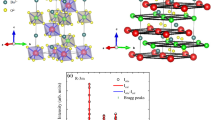

Crystal structure and Fe/Cu disorder

Figure 2 displays the observed and calculated squared structure factors for the nuclear structure of the YBCFO crystal obtained from single-crystal neutron diffraction. The structure was refined at 10 K from 537 nuclear reflections (295 independent) collected on D9 using a closed-cycle cryostat. The agreement plots of the nuclear structure refinement at the base temperature are shown in Fig. 2a,b (χ2: 0.84, RF: 3.72, RF2: 5.26). The crystal structure obtained at 10 K is described in Fig. 2c,d. The structure hardly changes with temperature, with no significant variations detected between 10 K and 450 K, in the paramagnetic phase (Supplementary Table 1), beyond the expected shrinking of the atomic displacement ellipsoids representing thermal agitation (schematically depicted in Fig. 2d at 10 K). The atomic positions and the Cu/Fe occupancies in the two pyramids of the unit cell were refined using the P4mm symmetry. The z-coordinates of a same metal M in upper (1, blue) and lower (2, brown) pyramids were constrained by z(M1) + z(M2) = 1. The rest of the symmetry-inequivalent atoms were refined independently. The detailed structural information obtained in the crystal is summarized in Fig. 2c,d. As previously mentioned, a key feature in these perovskites is the Fe/Cu chemical disorder, because it generates frustration and has a strong influence on the magnetic features and transition temperatures. As mentioned in the Introduction, the average Fe/Cu disorder over the full crystal volume is described by the refined occupation nd of the fraction of the minority ions at respectively the M1 (Cu-rich) and M2 (Fe-rich) pyramids (Fe1* and Cu2* sites). The asterisk reminds us that this position is of antisite type. So, a B-site random disorder would correspond to nd = 0.5, and nd = 0 describes a fully ordered Fe/Cu structure. From SCND we carefully refined the partial occupations finding nd = 0.32(6) in the crystal. This implies that ≈32% of nominal Cu pyramids are occupied by Fe in the sample, and vice versa. Notice that nd represents the fraction of antisites averaged over the crystal but it is not sensitive to spatial correlations between them. Remarkably, although chemical disorder is in this crystal lower than in powder samples prepared under fast cooling that yield TS above room temperature, we will show next that this disorder is enough to stabilize the incommensurate magnetic order close to ∼ 200 K.

a Agreement plot of the refinement on nuclear reflections of the single-crystal collected at 10 K on D9@ILL (λ = 0.837 Å). b The calculated structure factors are plotted against the experimental ones. c Crystal structure at 10 K obtained by single-crystal neutron diffraction (agreement factors: χ2 = 0.84, RF = 3.72, RF2 = 5.26). d Projection of the structure at 10 K showing the P4mm unit cell. The color of each pyramid corresponds to that of the dominant cation in it (blue: Cu; brown: Fe). The atomic displacement ellipsoids correspond to a 99 % probability level. The errors in (a) and (c) are the standard deviations obtained using the FullProf Suite package33.

Magnetic phases: temperature dependence

Regarding the evolution of the magnetic order, temperature-dependent neutron diffraction measurements were performed using the Cyclops Laue diffractometer, which revealed the presence of the incommensurate magnetic phase below ≈ 195 K (TN2) and allowed indexing the commensurate (CM, k1 = (1/2, 1/2, 1/2)) and incommensurate (ICM, k2 = (1/2, 1/2, 1/2 ± q)) magnetic propagation vectors. Only these two magnetic wave vectors were observed throughout the investigated temperature range. This was further corroborated by multiple QL-scans performed on D9 in the 10-300 K range, with a step of 5 K between them. QL-scans were collected along the (0.5, 0.5, L) line (in the range 0.2 < L < 1.2), with the purpose of tracing the possible magnetic reflections as a function of temperature. A QL-scan collected at 10 K is shown in Fig. 3a. Figure 3b depicts a neutron contour map for the crystal showing the T − QL projection of the neutron-diffracted (0.5, 0.5, L) intensities collected as a function of temperature. It was obtained by adding up the multiple QL-scans.

a QL-scan along the (0.5, 0.5, L) line (range 0.2 < L < 1.2) obtained at 10 K. b T-QL projection of the temperature dependence of magnetic intensities along the (0.5, 0.5, L) line centered around the (½ ½ ½) position for the single crystal. c Temperature dependence of the neutron integrated intensities of CM (1/2 1/2 1/2) [k1] and ICM (1/2 1/2 1/2±qS) [k2] magnetic reflections. d Evolution with temperature of the discommensuration qS of the spiral phase. The twist angle φ (canting) formed by the two spins of a bipyramid in the spiral phase is also shown (φ = 2πqS). The error bars in (a) are statistical errors and in (c) and (d) the standard deviations obtained from the Gaussian least-square fits using the FullProf Suite package33.

The temperature dependence of the intensity of the representative magnetic peaks was also monitored. Figure 3c plots their integrated intensity recorded on D9 across the transition exposed in the susceptibility around 200 K. Only k1-type collinear magnetic domains are detected above TN2. Figure 3 confirms that a mutual transformation between the commensurate k1 = (1/2, 1/2, 1/2) and incommensurate k2 = (1/2, 1/2, 1/2 ± q) phases takes place at TN2 (TS). At the transition, the magnetic phase with k1 translational symmetry transforms under cooling into the spin-modulated k2 phase. Practically the whole volume of the AF1 phase transforms into the incommensurate AF2 one. Only a little residual untransformed amount of the high-temperature collinear phase (≈8%) is observed below the transition. 195 K is the highest TS reported so far for a YBCFO crystal. Below that temperature, the discommensuration is described by the non-null modulation factor q (hereinafter referred to as qS). The evolution of the magnetic modulation qS(T) in the crystal was determined from the neutron scans and it is exposed in Fig. 3d. The magnetic modulation appears at TN2 ( = TS) and progressively develops to reach its maximum amplitude. The observed evolution is compatible with a second-order type transition. We recall at this point that an evolution from second- to first-order CM-ICM transition is suggested in previous reports on powder samples when TN2 approaches TN1 (highly disordered samples)11,12. The value of the incommensurability determined at 10 K is qS = 0.104 r.l.u. This value is appreciably lower than the maximum discommensuration previously reported in YBCFO (\({q}_{s}^{c}\) ≈ 0.18 r.l.u. at the triple point12).

In the theory, the incommensurate wave vector and the spiral temperature are both proportional to the concentration of antiferromagnetic Fe/Fe bonds, predicting a linear relationship between qS and TS. From the linear fit to the experimental (qS,TS) points reported in powder samples, a temperature TS ≈ 210 K would be expected. The Néel temperature associated with the collinear commensurate order in YBCFO samples decreases as magnetic frustration increases. However, this decrease is more gradual compared to the steeper increase observed for the spiral transition temperature (TS). The (qS,TS) and (qS,TN1) points from our crystal match well the magnetic phase diagram (TN versus qS) for powder YBCFO samples varying Fe/Cu disorder reported in ref. 12.

Spherical neutron polarimetry

A detailed description of the SNP technique can be found in refs. 23,24. The Blume-Maleyev equations25,26 describe the scattering of polarized neutrons. According to them, the final neutron spin Pf is related to the initial one Pi by:

Where \({\mathscr{P}}\) is the rotation matrix acting on the initial neutron spin and P’ is the polarization created (or annihilated). Using the orthogonal right-handed axes with x parallel to the scattering vector Q and z vertical, and the initial polarization along the directions x, y, or z, the final polarization can be determined by nine measurements represented in a pseudomatrix known as the polarization matrix (Pfi). The polarization matrix combines the rotation and the created polarization and each row corresponds to the final polarization when the initial polarization is along x, y, or z, respectively. For reflections that are purely magnetic (as the ones measured in YBCFO) the scattered intensities depending on the initial neutron polarization are Ix = M 2 + p0 Jyz, Iy = Iz = M2, and the matrix reduces to:

Where M2 = \({{{\bf{M}}}_{{{\perp }}}{\bf{M}}}_{{{\perp }}}^{* }\), \({M}_{{{\perp }}y}^{2}\) = \({{M}_{{{\perp }}y}M}_{{{\perp }}y}^{* }\), and \({M}_{{{\perp }}z}^{2}\) = \({{M}_{{{\perp }}z}M}_{z}^{* }\). p0 is the polarization of the incoming beam. The so-called magnetic interaction vector \({\boldsymbol{M}}_{{{\perp }}}\) lies in the yz plane, \({M}_{{{\perp }}}\left({\boldsymbol{Q}}\right)=(0,\,{M}_{{{\perp }}y},{M}_{{{\perp }}z})\). The off-diagonal components of P (\({R}_{{yz}}=2{Re}({M}_{{{\perp }}y}{M}_{{{\perp }}z}^{* })\) and \({J}_{{yz}}=2{Im}({M}_{{{\perp }}y}{M}_{{{\perp }}z}^{* })\)) generate components in the scattered polarization along directions which are not parallel to the incident neutron polarization. Hence they produce the rotation of the neutron polarization in the scattering process. The matrix can also be rewritten as

The chiral vector is T = i(M*xM) = (Tx,0,0)=i(\({{M}_{y}}{{M}_{z}}^{* }\) -\({{M}_{y}^{* }M}_{z}\), 0, 0)= −2(Im(\({{M}_{y}M}_{z}^{* }\)), 0, 0). So, the so-called “chiral” terms are the off-diagonal elements Pxy and Pxz, where \({J}_{{yz}}=2{Im}({M}_{{{\perp }}y}{M}_{{{\perp }}z}^{* })\) in the polarization matrix results from chiral scattering and can only be non-null if the magnetic structure is non-collinear. The chiral vector T is a real vector that directly contributes to the creation of polarization parallel to x (or Q) when \({{{\bf{M}}}_{{{\perp }}}{\rm{x}}{\bf{M}}}_{{{\perp }}}^{* }\) (or Jyz) is nonzero. In the presence of domains with opposite magnetic chirality, the contribution of each chiral domain to Jyz has the sign inverted respect to the other.

Zero-field neutron polarimetry measurements were conducted at 200, 100, and 10 K using CryoPAD. The incident beam was polarized by Bragg reflection from a monochromator of ferromagnetic Heusler alloy (Cu2MnAl). Nutators and precession fields were used to control the direction of the incident neutron polarization (Pi). The scattered polarization was analysed with a 3He neutron spin filter. The efficiency of the polarization at all temperatures was corrected from several measurements of Pzz on the (111) nuclear reflection.

The commensurate collinear AF1 phase

The AF1 magnetic ordering was studied by unpolarized and polarized single-crystal neutron diffraction.

Unpolarized magnetic neutron diffraction in the AF1 phase (200 K)

When the AF1 collinear phase is regarded as a single domain the calculated integrated intensities do not match properly the experimental data recorded at 200 K (χ2 = 28.4, Fig. 4(a)). Only when twining domains are considered, refinements can satisfactorily reproduce the magnetic single- crystal data in the AF1 state (χ2 = 2.87, Fig. 4b). The tetragonal symmetry is broken by the spin ordering at TN1, giving rise to two types of magnetic domains, related by the tetragonal axis 4+(0,0,z) lost at the magnetic transition. Only the magnetic domains D1 = (x, y, z) (1) and D2 = (−y, x, z) (4+) were included in the magnetic refinement of Fig. 4b. The best solution found for the commensurate collinear phase is described in Table 1 (magnetic space group: Icma2 (1/2a − 1/2b, 1/2a + 1/2b, c; 1/4, 0, 0) [Nr. 46.246]). The refined fraction of D1 domains from D10 data was 53.7(1.6)%, versus a 46.3% of D2 type. The refined magnetic order in each type of domain is shown in Fig. 4c. θc is the inclination angle that collinear spins form with the c axis in the AF1 phase. ϕc is the azimuthal angle that their projection onto the ab plane forms with the a axis.

Best magnetic refinements at 200 K of D10@ILL data [k1 = (1/2,1/2,1/2)]. a For a single magnetic domain. b For twin magnetic domains of the type 1 and 4+. Insets: calculated magnetic structure factors plotted against the experimental ones. c Projections of the refined collinear magnetic orders for D1 (x,y,z) and D2 (−y,x,z) domains in the crystal at 200 K. Variation of χ2 and other agreement factors as a function of (d) the inclination angle θc and (e) the azimuthal orientation ϕc (projected in the ab plane) of the spins direction in AF1. (f) Dependence with the value of the phase φ‘c between m1 and m2 moments in the chemical cell. Refinements were performed fixing only one angle each time and including twin domains. Best agreement corresponds to θc = ± 90° (spins in the ab-plane), ϕc = 45°/225° (diagonal easy-axis) and φ‘c = 180° (m2 antiparallel to m1). The error bars in (a) and (b) are the standard deviations of the integrated intensities.

In Fig. 4d–f we show how the resulting agreement factors vary with the value of θc, ϕc, and φ‘c (referred to D1 domains). φ‘c describes the magnetic phase between m1 and m2 moments in the chemical cell. The best agreement found corresponds to θc = ±π/2, ϕc = π/4 (3π/4) and φ’c = π. The two first angles imply collinear moments parallel to the ab-plane (θc = 90°) aligned along the diagonal axis [1, ± 1,0] of the tetragonal cell (ϕc = ± 45°, minus signs refer to D2). Notice however in the χ2–scale of Fig. 4e that the variations due to the azimuthal orientation ϕc are little (Δχ2 < 1). Nevertheless, we will show below that SNP unambiguously confirms the diagonal direction of the moments in the AF1 state.

The two average ordered magnetic moments (m1 and m2) at, respectively, the upper and lower pyramids of the chemical cell were refined independently. Given that the theoretical ratio m(Fe3+)/m(Cu2+) of their respective unpaired spins is 5, we also performed refinements constraining the two average ordered moments (in pyramids 1 and 2) according to the ratio r (r ≡ m1/m2 = (1 + 4· nd)/(5 − 4· nd) deduced from the refined Fe and Cu occupations, being nd = 0.32(6) the refined occupation of the minority [Fe or Cu] ions in each pyramid of the unit cell). Within the errors, both procedures gave the same results for the ordered moments.

Spherical neutron polarimetry in the AF1 phase

A scenario with a single type of magnetic domain is not compatible with the data for any orientation of the collinear moments. When the two conjugated domains are included, the SNP measurements at 200 K are in excellent agreement with the calculated matrix elements for the “diagonal” collinear magnetic model. In the case of a perfect balance between both domains, the off-diagonal matrix elements Pyz and Pzy must cancel, so that their finite values listed in Supplementary Table 2 can be taken as the signature of a certain imbalance in the population of D1 and D2 collinear domains. The domain population and the spin orientation in the AF1 phase at 200 K were refined to the SNP data using Mag2Pol27. A domain population D1/D2 = 53.1/46.9(0.5) was determined by SNP, in good agreement with D10 results. Unequivocally, only the diagonal solution in presence of conjugated domains satisfactorily reproduces the elements of the full polarization matrices measured in three magnetic reflections at 200 K. The best refinement of SNP data (\({{\rm{\chi }}}^{2}\) = 3.22) determined the spin orientation shown in Table 1 (θc = 90.8(1), φc = 43(8)). The preferred diagonal azimuthal orientation (m//(1, ± 1,0)) of the spins suggested by the magnetic integrated intensities (D10) was thus definitely confirmed by SNP measurements. The agreement between observed and calculated elements of the polarization matrices at 200 K is shown in the Fig. 5a and Supplementary Table 2. Figure 5b, c exhibit the collinear magnetic structure in each domain.

(200 K, D3@ILL). a Observed (circles) and calculated (squares) polarization values Pif for incident neutrons polarized along Pi (inner symbol color) and polarization analysis along Pf (symbol edge color) for the three directions x (red), y (green), and z (blue) in the local coordination system (x parallel to the scattering vector Q and z vertical). All observed (Obs.) and calculated (Calc.) values are listed in Supplementary Table 2. b The best fit is obtained for a collinear k1 model with conjugated magnetic domains (D1, D2) with moments along the ab diagonals. c Refined collinear magnetic structures in D1 and D2 AF1 magnetic domains.

To summarize the AF1 state in the crystal, polarized and unpolarized neutron results unveil the coexistence of (x, y, z) (D1) and (−y, x, z) (D2) collinear AF1 domains, with volume fractions D1/D2 = 53/47(0.5)% and the spins aligned parallel to the ab-plane, along the diagonals of the tetragonal cell.

The incommensurate magnetic order in YBCFO

The details of the incommensurate magnetic ordering have been thoroughly investigated by unpolarized and polarized single-crystal neutron diffraction. An incommensurate spiral phase can be described in the form:

where mlj is the magnetic moment of the atom j in the unit cell l, Rl is the vector joining the arbitrary origin to the origin of unit cell l, and Φj is a magnetic phase. In YBCFO j = 1,2 (the two metal sites in the unit cell). uj and vj designate the orientation of the two perpendicular unitary vectors that define the plane of the helix, where MR (real) and MI (imaginary) amplitudes fix the dimensions of the elliptical envelope described by the rotating magnetic moments. In powder samples of the YBCFO structural family, it is not possible to independently refine (i) the real and imaginary amplitudes (MR and MI) or (ii) the two magnetic moments in the bipyramidal units. The inability to refine the real and imaginary amplitudes is the most relevant drawback when the incommensurate magnetism of this layered structure is investigated by neutrons in powder samples. The reason is that NPD does not allow to discriminate between collinear (sinusoidal) and non-collinear (spiral) spin orders. The sinusoidal (modulated) model corresponds to the limit MI = 0 (very large eccentricity or MR ≫ MI) and the opposed limit is a circular spiral (null eccentricity: MR = MI). In the earlier works the circular spiral model was adopted to refine NPD data, but it was recognized that a sinusoidal collinear model perfectly reproduces the NPD patterns below TS9,12. This is illustrated in Supplementary Note 2, where we show the sinusoidal and spiral Rietveld fits for polycrystalline YBCFO. This limitation evidences the need for single-crystal neutron studies.

Unpolarized magnetic neutron diffraction in the AF2 phase (10 K)

The incommensurate magnetic order in YBCFO has been investigated at 10 K, first by unpolarized single-crystal neutron diffraction. Large nuclear (113 reflections) and magnetic (326 incommensurate reflections) data collections were made using D10. For the magnetic data treatment, the scale and structural factors were fixed to the values obtained by refining the nuclear structure. The average magnetic moments at the two pyramids were refined independently, and also constraining the moments according to the refined Fe and Cu occupations through the ratio r as explained for the AF1 phase. As for the AF1 phase, both approximations gave the same ordered moments, within the errors.

A central feature is the inclination of the spin rotation plane in the crystal. The angle θ describes the angular distance (inclination) between the direction of the spins and the c axis. In the spiral phase θS stands for the tilting of the rotation plane of the helix (uv plane in Eq. (4)). Figure 6 exposes the goodness of the fit parameters (χ2, RF2, and RF) as a function of the tilting angle θS in the refinement of the spiral configuration (including chiral domains). Two marked minima are apparent in the SCND refinements corresponding to θS = ± 90°. They confirm that the spin rotation plane in the crystal is parallel to the tetragonal ab plane. The incommensurate magnetic order, therefore, would correspond to a helical rather than cycloidal configuration.

a Neutron refinement at 10 K (D10@ILL) of the incommensurate magnetic intensities using the circular spiral model described in Table 2. b Best fit corresponds to a helical configuration (null cycloidal component). Variation of χ2 and other agreement factors as a function of (c) the inclination angle θS and (d) the magnetic phase φ‘S between m1 and m2 moments in the chemical cell. Best agreement is found for θS = ± 90(2)° (spins in the ab-plane) and φ‘S = 171(1)°. The error bars in (a) are the standard deviations of the integrated intensities.

Assuming a single type of domain the sinusoidal model cannot reproduce the experimental intensities, whereas a circular spiral model with the spin rotation plane perpendicular to c (helical order) fits well the observed magnetic intensities (see Supplementary Fig. 3). This is also illustrated in Fig. 7 that shows the evolution, in the single-domain picture, of the agreement factors and refined values for selected magnetic parameters as a function of the eccentricity of the elliptical envelope represented by the MI/MR ratio. Using a single-domain model, the integrated neutron intensities at 10 K were well reproduced with MI/MR = 1, and the best magnetic refinement (χ2 = 5.05; RF = 7.55; \({{\rm{R}}}_{{\rm{F}}}^{2}\) = 11.8) is shown in Fig. 6a. The obtained magnetic structure corresponds to the circular spiral described in Table 2 (Unpolarized neutrons (D10)) and plotted in Fig. 6b.

(10 K, D10@ILL). a Evolution of the agreement factors of the AF1 refined magnetic structure as a function of the eccentricity of the elliptical envelope, represented by the MI/MR ratio. Refined values for selected magnetic parameters: b azimuthal angle ϕS (left axis) and tilting angle θS (right axis), c the real and imaginary amplitudes of the elliptical envelope, and d the φ’S phase. The real and imaginary amplitudes (MR and MI) of the elliptical envelopes for m1 and m2 are illustrated in (e). The error bars in (b) and (d) are the standard deviations obtained from the fits using the FullProf Suite package33.

The frequency shift qS measures how much the magnetic wave deviates from the antitranslational symmetry along c (Φ = π + 2πqS = φ + φ’). The angle Φ (see Fig. 7e) stands for the rotation angle made by the spins of equivalent pyramids in successive cells. The twist angle φ is the canting between the two spins of a bipyramid in the spiral phase, whereas φ’ (Fig. 7e) stands for the phase between the average magnetic moments at the two magnetic sites in the chemical cell (m1 and m2). In powder samples, it has been generally assumed that φ’ = π and then the canting in the bipyramid is φ = 2πqs. In the crystal we carefully refined the value of φ’ and Fig. 6d discloses the evolution of the goodness-of-fit parameter χ2 and other agreement factors obtained in the fits varying the value of the phase φ’ between m1 and m2 moments in the chemical cell. SCND refinements unveil an absolute minimum at φ’min = 171(1)°, close but somewhat deviating from 180°. Although the two moments are strictly inverted in the collinear AF1 phase (φ’c = 180(1)°, Table 1), the phase between them deviates slightly from π in the incommensurate phase.

A deeper analysis needs to consider configuration domains (twin domains D1/D2) in the sinusoidal model and chirality domains (C1/C2) in the spin helix configuration. Using polarized neutrons, the SNP analysis including domains will be presented later on. With unpolarized neutrons, we cannot discern between inverted chirality domains, and hence the results are independent of the C1/C2 ratio. The unpolarized neutron data collected on D10 at 10 K have been also analyzed considering two types of sinusoidal magnetic domains with orthogonal spin directions [D1 = (x, y, z) and D2 = (−y, x, z), the conjugated twin domains]. In such a case, the D10 magnetic intensities can be reproduced if the population of these two types of collinear sinusoidal domains is included in the refinement. As expected, the result of combining orthogonal modulations is equivalent to the circular spiral model when the domain fraction approaches the 50%. The refined values were 49.2/50.8(1.4). The rest of magnetic parameters and goodness-of-fit factors are listed in Table 2, being identical to the single-domain spiral model, and the magnetic moments are related by the typical √2 factor (being too high in the sinusoidal fit when compared to the refined ones in AF1). Therefore, unpolarized neutron results are consistent with a helical order, or the presence of two equal amplitude but orthogonal magnetic modulations, which are the required conditions for a circular helix. A simple incommensurate helix with circular envelope and the spins rotating parallel to the ab plane of the crystal satisfactorily reproduces these measurements. In the following paragraphs, the validity and robustness of the circular spiral model are further investigated using polarized neutrons.

Spherical neutron polarimetry in the incommensurate magnetic phase

To further corroborate previous results and get even more precision on the magnetic ordering and the population of magnetic domains in the incommensurate magnetic phase, previous measurements on D9 and D10 were complemented with an SNP study below the incommensurate transition. To this end, the crystal was cooled down from the paramagnetic state to 100 K and 10 K in E-field conditions (+8 kV along the z-direction). Up to 5 incommensurate reflections were investigated with polarized neutrons: (000)+k, (001)+k, (002)+k, (112)−k, and (114)−k. For the two last, the polarization elements Pif were measured first with positive incident polarization (Pi > 0), and then additionally also with negative (inverted) incident polarization (Pi < 0). The polarization elements (Pif) measured at 10 K are shown in Fig. 8 and in Supplementary Table 2. The two magnetic models evaluated with unpolarized neutrons (MR ≫ MI [sinusoidal] and MR = MI [circular spiral]) were carefully confronted to the experimental polarization matrices. For both models the inclusion of two types of magnetic domains (twin domains in the sinusoidal and chiral domains in the spiral models) was crucial. The fit of the polarimetry data obtained in the CryoPAD device at D3 was performed using Mag2Pol27. The best refinement to the polarimetry data (at 10 K) was obtained for the circular spiral model. The fit yields the magnetic structure described in Table 2 giving validity and robustness to the helical description obtained from our analysis of the unpolarized neutron experiments. The results of the refinement to the SNP data at 10 K are summarized in Fig. 8 and Table 2.

Incommensurate AF2 phase at 10 K, D3@ILL. a Observed (circles) and calculated (squares) polarization values Pif for incident neutrons polarized along Pi (inner symbol color) and polarization analysis along Pf (symbol edge color) for the three directions x (red symbols), y (green symbols), and z (blue symbols) in the local coordination system (x parallel to the scattering vector Q and z vertical). For the reflections that appear twice, in the second one, the incident neutron polarization was inverted with respect to the first. All observed (Obs.) and calculated (Calc.) values are listed in Supplementary Table 2. b The best fit corresponds to a helix, with spins rotating in the ab plane (C//k2z) and coexisting (50/50 %) chiral domains (C1 and C2).

Exploring the magnetoelectric response with SNP

At 100 K we also explored possible changes in the magnetic configuration and the proportion of the two chiral domains under application of an electrical field E parallel to z, namely along the [1 −1 0] axis of the crystal (ab diagonal, Fig. 1a). In the most simple model for creating a polarization from the spiral order, the DM-based mechanism named spin current model, the direction of the polarization P is given by P α rij × (Si × Sj), with rij being the unit vector between neighboring spins Si and Sj, and Cij = Si × Sj the spin chirality vector (see Fig. 8b)28. Here, rij is parallel to the c axis, and assuming the easy axis along the diagonals, in our structure P would be parallel to [1 −1 0] axis. Moreover, P α Cij · cos(θS). The crystal was cooled down from the paramagnetic state to 100 K under an E-field of +18.2 kV cm-1 applied to the [1 −1 0] direction. We performed neutron polarization measurements to determine the elements of the polarization matrix for the k2–type reflection (1/2 1/2 1.42), corresponding to (112)−k. At 100 K the wave vector k2 = (1/2, 1/2, 1/2−qS) of the spiral adopts a qS ≈ 0.10 r.l.u. modulation. The neutron polarization measurements were repeated switching the E-field from +18.2 kV cm−1 to 0 kV cm−1 and finally to approx. −14.8 kV cm−1 (the full matrix was determined at +18.2 and −14.8 kV cm-1; at 0 kV cm-1 only Pxy, Pyx, and Pzx terms were measured). The SNP measurements are disclosed in Supplementary Table 3. At these voltages, in the configuration described, we did not detect changes in the off-diagonal terms of the polarization matrix (nor in the diagonal) for the (1/2 1/2 1.42) magnetic reflection. Off-diagonal terms were found close to zero and the variations registered varying E were not meaningful according to experimental errors [σ] (see the Supplementary Note 6).

We did simulations of the Pif terms of the neutron polarization matrix in the incommensurate phase for the (112)-k magnetic reflection varying the magnetic domain populations in different models. They are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4 for three different cases: (a) the circular spiral model with chiral magnetic domains (C1, C2) and spins in the ab plane; (b) the sinusoidal model along a axis with conjugated magnetic domains (D1, D2); and (c) the sinusoidal model parallel to the ab diagonal axis, with magnetic conjugated domains. The expected non-null polarization matrix terms (Pij) and their dependence with the domain population are shown for the three models. Notice that in the three magnetic models, all off-diagonal terms are expected to be null as long as the domain population is ∼ 50%–50%. As it can be observed in the simulations, for YBCFO an inversion of the sign of the Pyx and Pzx terms could be expected after the inversion of the population of chiral domains in the case of a switchable electric polarization. Since there is no variation after inverting the polarity of the voltage, it can be concluded that the applied electric field has no effect on the non-collinear spins parallel to the ab plane. The absence of magnetoelectric response is in agreement with the DM mechanism in multiferroics when there is a pure helix, with the spiral rotation plane (ab plane) perpendicular to the incommensurate wave vector (k2z). This is the case of the spiral configuration in the present crystal. From Table 2 SNP results set a maximum possible inclination of 3° (θS = 93.3(4)°) of the rotation plane. Assuming a pure helix, here the magnetic symmetry is not compatible with linear magnetoelectric effects. Only higher-order magnetoelectric effects could occur.

Discussion

Finding insulating magnets displaying spiral or chiral magnetic orders (conical screw, cycloidal, helimagnetic, etc.) at ambient temperature is intrinsically difficult. Spiral magnets are being profusely investigated in the last years as potential candidates for magnetoelectric applications. They are rare and mostly belong to a class of geometrically frustrated magnets with magnetic transition temperatures typically below 50 K. In this context, the high thermal stability of the incommensurate magnetic order in YBCFO (presumed spiral in previous works) is certainly very exceptional.

We have reported the successful growth and characterization of quality YBCFO single crystals by a modified TSFZ technique presenting a fairly high fraction of Fe/Cu cation disorder (nd = 0.32(6)). Such disorder level is much higher than in other previous crystals (e.g., nd = 0.02 or 0.11 in refs. 29,30) displaying only commensurate collinear magnetic phases. The extrapolated minimal critical threshold in powder samples to have the incommensurate phase is n0 ≈ 0.11212. The studied crystal exhibits a modulation qS = 0.104 r.l.u. and a commensurate-to-incommensurate magnetic transition at TS = 195 K. These two values perfectly match the linear prediction between TS and qS of the Scaramucci model, previously confirmed in powder samples.

In our disordered YBCFO crystal, the realization of “spiral order by disorder” has been thoroughly investigated, with the objective of overcoming the critical limitations of neutron powder diffraction. For that purpose, the incommensurate magnetic phase of YBCFO has been examined by means of (i) unpolarized single-crystal neutron diffraction and (ii) spherical neutron polarimetry.

Collinear modulated and non-collinear spiral models, including the analysis of magnetic conjugated and chiral domains, were confronted to neutron experiments on single-crystal YBCFO. The emerging picture in the crystal requires the combination of two perpendicular modulations to give a non-collinear circular helical order below TS = 195 K. The spin rotation plane of the circular helix is found in the crystal parallel to the ab plane. Spherical neutron polarimetry results validate and give robustness to the helical description obtained from unpolarized neutron experiments. In the studied mm-sized crystal sample, equally populated ±1 magnetic chiral domains were found using polarized neutrons. Consistently with a purely helical magnetic spiral, application of electrical fields parallel to [1 −1 0] (SNP) does not modify the population of chiral domains. Additionally, we observed a deviation from 180° of the magnetic phase φ’ between m1 and m2 moments in the chemical cell when entering the incommensurate order, which was not predicted in the previous model. Instead of perfectly antiparallel, in the spiral configuration Fe and Cu spins separated by Yttrium layers form φ’S = 171(1) °. As shown in some hexaferrites without spontaneous electric polarization at zero magnetic field, tuning magnetic symmetry can be very effective to enhance magnetoelectric effects in helical magnets.

With regard to the AF1 ordering in the crystal, collinear moments were found parallel to the ab plane and aligned along the diagonal axis. The volume fractions of the conjugated (twin) domains [D1/D2 = 53/47(0.5) %] in the AF1 regime were more decompensated than the fractions of chiral domains found in AF2. A direct interpretation indicates that a given type of collinear AF1 domain (either D1 or D2) can generate below TS any of the two types of chiral domains, indistinctly.

The inclination angles refined for the moments in the collinear and spiral phases differ from those reported from NPD by different groups on YBCFO powder samples with similar transition temperatures. The possible influence of the growth method and grain size on the configuration of Cu/Fe disorder on a more local scale and the resulting magnetic anisotropy requires further studies. It is also of interest to emphasize the similarity of the helical configuration found in our YBCFO crystal with that reported in several better-known families of high-Tc multiferroic and magnetoelectric hexaferrites, which exhibit screw-like helimagnetic order in absence of external stimuli6,7,8,31. Giant magnetoelectric effects were observed in some conical Y-type hexaferrites with helical magnetic order and a moment rotation plane similar to that in our crystal. These hexaferrites illustrate very well how multiferroicity and the cross-coupling between magnetic and ferroelectric orders can be enhanced by flopping the magnetic rotation plane7. The large magnetoelectric effects on hexaferrite crystals demand additional efforts in YBCFO crystals intended to modify the magnetic symmetry of the helical order. More research is required to further assess the relevance of the inverse DM interaction3, spin current28, or exchange-striction32 as potential mechanisms to produce magnetoelectric effects in these layered perovskites.

As main conclusion, the layered structure of YBaCuFeO5 represents a unique example, where frustration based on chemical disorder gives rise to spiral phases with exceptional stability and tunability, being a good realization of the new “spiral order by disorder” mechanism. This study has removed essential ambiguities persisting in the literature, still based on powder samples, covering the gap created by the lack of single-crystal investigations. Finally, the work provides some essential keys that evidence the need to develop efficient strategies to fabricate YBCFO-type perovskites in crystalline forms (single crystals, films, or heterostructures) where chiral spiral ordering with cycloidal components may be stabilized and manipulated above room temperature.

Methods

Crystal growth

Single crystals of the layered perovskite YBCFO were grown by the traveling solvent floating zone (TSFZ) method. First, polycrystalline YBCFO was prepared through the conventional solid-state reaction method, as described in Refs. 9,18. The powder was loaded, packed with cylindrical shape, compacted under 1500 bar, and sintered. A solvent consisting of CuO with 2 wt% B2O3 was used for the crystal growth by the TSFZ method using a four-mirror optical furnace. Further details on the procedure followed for the growth can be found in refs. 29,30. In the ingot, the c axis of the YBCFO structure was perpendicular to the FZ growth direction (parallel to (110)). The elemental composition of the crystal was assessed by Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES). ICP-OES technique confirmed that relative molar fractions of the cations in the crystal do not deviate from the nominal composition. Crystal quality and orientation were characterized by neutron Laue images and oxygen stoichiometry was further confirmed by neutron diffraction.

Magnetic susceptibility

DC magnetization measurements were carried out using a VSM magnetometer in a Physical Properties Measurement System (PPMS, Quantum Design Inc). Measurements were performed parallel to the c and the a axis of the crystal, in field-cooling conditions (FC, 1 kOe) between 10 and 520 K.

Single-crystal neutron diffraction

Neutron Laue and four-circle neutron diffraction experiments using unpolarized neutrons were performed at the high-flux reactor of the Institut Laue-Langevin (ILL, Grenoble, France). First, the homogeneity and orientation of the crystals were assessed from neutron Laue diffraction patterns using Orient Express. Further temperature-dependent reciprocal space maps were recorded using the Cyclops Laue diffractometer between 50 and 300 K. Single-crystal neutron diffraction (λ = 2.36 Å) was performed at the four-circle diffractometer D10. A 96 × 96 mm2 area detector was used to register the scattered neutrons during nuclear and magnetic data collection on D10 at T = 10 and 200 K. Additional measurements were carried out at the hot-neutrons four-circle diffractometer D9 (λ = 0.837 Å), equipped with a small two-dimensional (2D) area detector of 64 × 64 mm2 (32 × 32 pixels) to survey the reciprocal space. Large sets of 537 nuclear Bragg reflections (295 independent) were collected at 450 K and 10 K using a closed-shell furnace and closed-cycle cryostat to obtain a good structural model and the fraction of Fe/Cu cationic order. Additionally, q-scans were collected along specific directions to assess the presence of the different propagation vectors. The temperature dependence of particular peaks was monitored between 50 K and room temperature using a displex cryostat. Structural and magnetic refinements were carried out using the FullProf Suite programs33. Neutron data refinements were done by least square minimization of the integrated intensities and extinction corrections were applied following the model of Becker-Coppens34. The illustrations of the crystal structure were obtained using the VESTA program35.

Spherical neutron polarimetry

Spherical neutron polarimetry (SNP) experiments were conducted at the hot neutron diffractometer D3 (ILL, Grenoble). The same sample as in D9 and D10 experiments was used. Measurements were carried out using the CryoPAD equipment (operated at λ = 0.832 Å) after zero-field cooling through the two magnetic transitions. To access magnetic reflections associated with the incommensurate propagation vector k2 = (1/2, 1/2, 1/2±q) the crystal was mounted with the [001] and [111] axis aligned parallel to the horizontal xy plane (Fig. 1a). This geometry gave access to a series of magnetic reflections such as those of the type (00l) + q in the horizontal scattering plane. With the crystal b axis aligned vertical, no magnetic reflections were accessible. The magnetoelectric response was explored by means of an electrical field E applied parallel to z, namely along the [1 -1 0] axis of the crystal. We used the Mag2Pol program27 for analyzing and fitting the spherical neutron polarimetry data.

Data availability

Diffraction data were generated at the Institut Laue-Langevin. All relevant data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Mag2Pol and FullProf Suite programs are available free of charge at, respectively, https://www.ill.eu/users/instruments/instruments-list/d3/software and https://www.ill.eu/sites/fullprof.

References

Mühlbauer, S. et al. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science 323, 915–919 (2009).

Lawes, G. et al. Dielectric anomalies and spiral magnetic order in CoCr2O4. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 74, 024413 (2006).

Sergienko, I. A. & Dagotto, E. Role of the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in multiferroic perovskites. Phys. Rev. B - Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 73, 094434 (2006).

Kimura, T., Lawes, G. & Ramirez, A. P. Electric polarization rotation in a hexaferrite with long-wavelength magnetic structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 137201 (2005).

Ishiwata, S., Taguchi, Y., Murakawa, H., Onose, Y. & Tokura, Y. Low-magnetic-field control of electric polarization vector in a helimagnet. Science 319, 1643–1646 (2008).

Kocsis, V. et al. Magnetization-polarization cross-control near room temperature in hexaferrite single crystals. Nat. Commun. 10, 1247 (2019).

Zhai, K. et al. Giant magnetoelectric effects achieved by tuning spin cone symmetry in Y-type hexaferrites. Nat. Commun. 8, 519 (2017).

Shao, Y. et al. Magnetoelectric coupling triggered by noncollinear magnetic structure in M-type hexaferrite. Adv. Quantum Technol. 4, 4–13 (2021).

Morin, M. et al. Incommensurate magnetic structure, Fe/Cu chemical disorder, and magnetic interactions in the high-temperature multiferroic YBaCuFeO5. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 91, 064408 (2015).

Morin, M. et al. Tuning magnetic spirals beyond room temperature with chemical disorder. Nat. Commun. 7, 13758 (2016).

Shang, T. et al. Design of magnetic spirals in layered perovskites: extending the stability range far beyond room temperature. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau6386 (2018).

Romaguera, A. et al. Helimagnets by disorder: its role on the high-temperature magnetic spiral in the YBaCuFeO5 perovskite. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 043188 (2022).

Scaramucci, A. et al. Spiral order from orientationally correlated random bonds in classical XY models. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013273 (2020).

Scaramucci, A. et al. Multiferroic magnetic spirals induced by random magnetic exchanges. Phys. Rev. X 8, 011005 (2018).

Kundys, B., Maignan, A. & Simon, C. Multiferroicity with high-TC in ceramics of the YBaCuFeO5 ordered perovskite. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 32–35 (2009).

Kawamura, Y. et al. High-temperature multiferroic state of RBaCuFeO5 (R = Y, Lu, and Tm). J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 79, 073705–073708 (2010).

Lai, Y. C. et al. Magnetic ordering and dielectric relaxation in the double perovskite YBaCuFeO5. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 145801 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. Tuning the tilting of the spiral plane by Mn doping in YBaCuFeO5 multiferroic. Acta Mater. 206, 116608 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Pushing magnetic spirals beyond room temperature by reducing the uniaxial pyramidal elongation in layered Cu/Fe perovskites. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 033081 (2024).

Er-Rakho, L., Michel, C., Lacorre, P. & Raveau, B. YBaCuFeO5+δ: a novel oxygen-deficient perovskite with a layer structure. J. Solid State Chem. 73, 531–535 (1988).

Caignaert, V. et al. Crystal and magnetic structure of YBaCuFeO5. J. Solid State Chem. 114, 24–35 (1995).

Song, Y. S. et al. Chemical doping-induced flop of ferroelectric polarization in multiferroic Mn0.9Co0.1WO4. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 82, 214418 (2010).

Brown, P. J. Spherical neutron polarimetry. in Neutron Scattering from Magnetic Materials (ed. Chatterji, T.) 215 (Elsevier, 2005).

Qureshi, N., Ressouche, E., Mukhin, A., Gospodinov, M. & Skumryev, V. Proof of the elusive high-temperature incommensurate phase in CuO by spherical neutron polarimetry. Sci. Adv. 6, 1–9 (2020).

Blume, M. Polarization effects in the magnetic elastic scattering of slow neutrons. Phys. Rev. 130, 1670–1676 (1963).

Maleyev, S. V., Bar’yakhtar, V. G. & Suris, R. A. The scattering of slow neutrons by complex magnetic structures. Sov. Phys. Solid State 4, 2533–2539 (1963).

Qureshi, N. Mag2pol: a program for the analysis of spherical neutron polarimetry, flipping ratio and integrated intensity data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 52, 175–185 (2019).

Katsura, H., Nagaosa, N. & Balatsky, A. V. Spin current and magnetoelectric effect in noncollinear magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 057205 (2005).

Romaguera, A., Zhang, X., Li, R., Fabelo, O. & García-Muñoz, J. L. Magnetic properties of highly ordered single crystals with layered YBaCuFeO5 structure. EPJ Web Conf. 286, 05005 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Magnetic properties of a highly ordered single crystal of the layered perovskite YBaCuFe0.95Mn0.05O5. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 551, 169165 (2022).

Tokura, Y., Seki, S. & Nagaosa, N. Multiferroics of spin origin. Rep. Prog. Phys. 77, 076501 (2014).

Choi, Y. J. et al. Ferroelectricity in an Ising chain magnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 047601 (2008).

Rodríguez-Carvajal, J. Recent advances in magnetic structure determination by neutron powder diffraction. Phys. B Phys. Condens. Matter 192, 55–69 (1993).

Becker, P. J. & Coppens, P. Extinction within the limit of validity of the Darwin transfer equations. I. General formalism for primary and secondary extinction and their applications to spherical crystals. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Cryst. Phys. Diffraction Theor. Gen. Crystallogr. 30, 129–147 (1974).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (MINCIU), through Projects No. PID2021-124734OB-C22 and RTI2018-098537-B-C21, co-funded by ERDF from EU, and “Severo Ochoa” Programme for Centres of Excellence in R&D (CEX2019-000917-S and CEX2023-001263-S); and from the Generalitat de Catalunya (Project 2021 SGR 445). A.R.’s work was done as a part of the Ph.D program in Materials Science at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. We acknowledge the Institut Laue-Langevin (ILL) for provision of beam time (Easy-445 and Easy-447, Test-2882 and dois: 10.5291/ILL-DATA.5-41−1153, 10.5291/ILL-DATA.5-41−1128, and 10.5291/ILL-DATA.5−14−273).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L.G.M. conceived and led the project; A.R. grew and characterized the crystal with assistance from J.L.G.M. and O.F.; A.R., O.F., and J.A.R.V. performed the neutron diffraction measurements. A.R. analyzed the neutron diffraction data with assistance from J.L.G.M.; N.Q contributed to the analysis of the SNP data; J.L.G.M. wrote the paper with the input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications materials thank the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Alannah Hallas and Aldo Isidori.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Romaguera, A., Fabelo, O., Qureshi, N. et al. Evidence of high-temperature magnetic spiral in YBaCuFeO5 single-crystal by spherical neutron polarimetry. Commun Mater 5, 273 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00710-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00710-1