Abstract

Magnetoelectric mutual control in multiferroics, which is the electric control of magnetization, or reciprocally the magnetic control of polarization has attracted much attention because of its possible applications to spintronic devices, multi-bit memories, and so on. While the required working temperature for the practical application is much higher than room temperature, which ensures stable functionality at room temperature, the reported working temperatures were at most around room temperature. Here, we demonstrated magnetic control of ferroelectric polarization at 432 K in ferroelectric and ferroelastic Tb2(MoO4)3, in which the polarity of ferroelectric polarization is coupled to the orthorhombic strain below the transition temperature 432 K. The paramagnetic but strongly magnetoelastic Tb3+ magnetic moments enable the magnetic control of ferroelectric and ferroelastic domains; the ferroelectric polarization is controlled depending on whether the magnetic field is applied along [110] or [1\(\bar{1}\)0]. This result may pave a new avenue for designing high-temperature multiferroics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

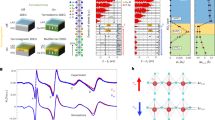

Since the discovery of magnetic control of ferroelectric polarization in TbMnO31, ferroelectrics that can be manipulated with magnetic fields have been attracting much attention, denoted as multiferroics. The highest working temperature of multiferroics is at present around room temperature2,3,4,5,6,7,8. To achieve a higher working temperature that enables commercial application9,10,11,12,13,14, a new material strategy should be needed. Multiferroics can be classified into two categories (Type-I and Type-II)13,15,16. In one category (Type-II), ferroelectricity is induced by some magnetic ordering. In this case, the coupling between polarization and the magnetic field is very large, and a giant magnetoelectric effect is observed. Nevertheless, the ferroelectric transition temperature is usually lower than room temperature1,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. The exceptional case is hexaferrite3,4,5,6,8,26,27,28,29,30. The ferroelectric transition temperature is reported to be around 450 K, but the working temperature of the magnetoelectric effect is, in many cases, around room temperature due to the problem of residual electric conduction8. A paper reported, the modulation of ferroelectric polarization at 405 K in a hexaferrite, but the polarization reversal by a magnetic field was not achieved5. In the other category (Type-I), ferroelectricity emerges independently of magnetic ordering. Several multiferroic materials in this category have ferroelectric transition temperatures much higher than room temperature13,15,16. In this case, the coupling between electric polarization and the magnetic field is usually very weak so that the ferroelectric polarization can not be reversed by a magnetic field. In this paper, we demonstrated that the magnetoelectric coupling becomes strong, and the high-temperature magnetoelectric effect is achieved in a Type-I of multiferroic Tb2(MoO4)3. This material shows ferroelectricity and ferroelasticity below 432 K; the ferroelectric polarization is coupled to the orthorombic distortion31,32,33,34. While Tb3+ moments are paramagnetic above 0.45 K35, the magnetization curve becomes anisotropic in the ferroelectric state36. The polarization reversal by a magnetic field was reported below 100 K36,37, but magnetoelectric effect was not reported in the higher temperature region in this material.

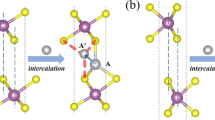

Figure 1a shows the crystal structure of Tb2(MoO4)3 above the ferroelectric transition temperature Tc = 432 K38. It is composed of corner-shared MoO4 tetrahedra and TbO7 octahedra. The space group of this high-temperature paraelectric state is \(P\bar{4}{2}_{1}m\) and the point group is \(\bar{4}2m\), which is nonpolar but noncentrosymmetric. Several multiferroic materials such as CuB2O4 and Ba2CoGe2O7 have the same point group and show unique magnetoelectric properties reflecting the point group symmetry21,39,40. To illustrate the symmetrical properties of \(\bar{4}2m\) point group, we utilize a compressed tetrahedron. It is a simple object and has the \(\bar{4}2m\) point group symmetry as shown in Fig. 1a. The electric polarization along the [001]t direction should be piezoelectrically induced by a diagonal uniaxial strain in the (001)t plane (Fig. 1b). Here, the suffix t denotes the crystal axes in the notation of high-temperature tetragonal phase. The sign of electric polarization depends on whether the uniaxial strain is along [110]t or [1\(\bar{1}\)0]t. Importantly, electric polarization is similarly induced by a magnetic moment. When the magnetic moment is along [110]t, the up-down symmetry is broken, and polarization should be induced. The polarization is unchanged by the inversion of the magnetic moment but reversed by the 90 ° rotation of the magnetic moment. Because of this symmetrical property, strong coupling between ferroelectric polarization and magnetic moments is expected in this material. Previously, this coupling has been studied below 100 K36,37. In this paper, we have demonstrated the magnetic control of electric polarization even at 430 K.

a Schematic illustrations of tetragonal crystal structure of Tb2(MoO4)3 above Tc = 432 K, and a tetrahedron, which is a motif of \(\bar{4}2m\) point group symmetry, with a magnetic moment. The crystal structure is drawn by VESTA51. b Schematic illustrations of piezoelectric and magnetoelectric properties of \(\bar{4}2m\) point group. Uniaxial stress ε along the [110]t or [1\(\bar{1}\)0]t direction induces the polarization. The sign of polarization depends on whether the stress is applied along [110]t (ε > 0) or [1\(\bar{1}\)0]t (ε < 0). Similarly, the polarization can be induced by a magnetic moment, and the sign depends on whether it is along [110]t or [1\(\bar{1}\)0]t.

Results

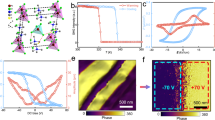

Figure 2a, b shows the temperature (T) dependences of relative dielectric constant (εr) and spontaneous polarization along the c-axis around Tc = 432 K for Tb2(MoO4)3. Before measuring the spontaneous polarization, we applied an electric field Ec = ±435 kV m−1, cooled the sample from 450 K to 320 K, and then turned off the electric field. Finally, we measured the polarization as the temperature increased. The dielectric constant was also measured as the temperature increased. The relative dielectric constant shows a sharp peak at Tc = 432 K and the spontaneous polarization, depending on the signs of Ec emerges below Tc, being consistent with the literature31,41. As previously reported, the ferroelectric transition is simultaneously a ferroelastic transition31,32,33,34. The two diagonal lengths in the c plane of the crystal structure become different from each other, and the orthorhombic distortion is coupled to the ferroelectric polarization below Tc. Therefore, this transition can be viewed as the spontaneous induction of uniaxial strain along [110]t or [1\(\bar{1}\)0]t shown in Fig. 1b31,32,33,34.

a Temperature dependence of relative dielectric constant at μ0H = 0 T. b Temperature dependence of the electric polarization at μ0H = 0 T measured on warming runs. Before the measurement, we cooled the sample from 450 K to 320 K in electric fields Ec = ±435 kV m−1. c Temperature dependence of the electric polarization measured on warming runs in the absence of any external field after cooling the sample down to 320 K applying magnetic fields ∣μ0H∣ = 10 T with various directions.

One can expect that the ferroelectric/ferroelastic domain can be controlled by a magnetic field according to the inference based on Fig. 1b. We certainly demonstrated that ferroelectric polarization can be controlled by a magnetic field. Figure 2c shows the temperature dependence of ferroelectric polarization measured on warming run in the absence of any electric and magnetic fields. Before the measurements, we cooled the sample down to 320 K in the presence of a 10 T magnetic field at various directions without any electric field. The magnitude of polarization is comparable with that after cooling in an electric field, which indicates that the magnetic field effectively aligns the ferroelectric domain. More importantly, the sign of polarization depends on whether the magnetic field applied before the polarization measurement is along [110]t or [1\(\bar{1}\)0]t while it is unchanged by the reversal of the magnetic field. It should be noted that similar magnetoelectric properties were observed in the multiferroics with the same \(\bar{4}2m\) point group symmetry, such as Ba2CoGe2O721. While the magnetoelectric responses were measured in the antiferromagnetic state in the previous cases, the present observation was in the paramagnetic state below the high transition temperature of 432 K31,35.

Figure 3a, b shows the temperature dependence of electric polarization measured on cooling runs without any electric field in various magnetic fields along [110]t and [\(\bar{1}\)10]t, respectively. Even at zero magnetic fields, finite electric polarization was observed, which indicates that the positive and negative ferroelectric domains were not perfectly canceled. In fact, the sign and magnitude of polarization at zero magnetic fields were not reproducible, so the 0 T data in Fig. 3a is different from that in Fig. 3b. The positive electric polarization increases as the magnetic field along [110]t increases. Above 8T, the electric polarization was almost saturated. When the magnetic field was applied along [\(\bar{1}\)10]t, the sign of polarization was negative, but the magnitude of polarization below Tc increases as the magnetic field is increased, similarly to the case of H∣∣[110]t.

Finally, we demonstrated the magnetic reversal of ferroelectric polarization. Figure 4 shows the magnetic field variation of electric polarization at various temperatures. Before the measurements, we aligned the electric polarization along the negative direction by cooling the sample from 450 K to the measurement temperature in an electric field −435 kV m−1, and turned off the electric field. Then we increased the magnetic field along [110]t to 15 T, and decreased it to 0 T while measuring the electric polarization. At 410 K, we subsequently swept the magnetic field to −15 T and then back to 0 T. After the magnetic field sweep, we warmed the sample to 450 K, measuring the electric polarization, which is used to estimate the absolute value of polarization in Fig. 4 (See Supplementary Fig. 5 in Supplementary Information). Note that the magnetic field along [110]t favors the positive polarization state, and therefore, the polarization reversal is expected if the magnetic field is strong enough. At 430 K, we observe the polarization reversal ~9 T. While a similar polarization reversal was previously observed below 100 K36,37, we here demonstrate it is possible at this high temperature. As the temperature decreases from 430 K, the reversal magnetic field and the magnitude of polarization increase. The increase in polarization magnitude is consistent with the temperature dependence shown in Fig. 3. As we show for the 410 K data, the polarization after the reversal is almost unchanged by the application of a negative magnetic field. In this sense, the polarization reversal is irreversible in contrast with previously observed reversible polarization reversals in some multiferroics7,8,17,27,28,29,30. Below 360 K, the polarization reversal was not fully observed because the reversal magnetic field is larger than 15 T.

a–g Magnetic field variation of electric polarization along the c axis (Pc) at various temperatures. Before the measurements, the polarization is aligned along the negative direction by an electric field. Then we applied magnetic fields along [110]t up to 15 T and then decreased it to 0 T at various temperatures while measuring the polarization. At 410 K, we subsequently swept the magnetic field to −15 T and then back to 0 T. After the magnetic field sweep measurements, we increased the temperature up to above the ferroelectric transition temperature to estimate the absolute value of polarization (Supplementary Fig. 5).

The observed temperature of magnetically induced polarization reversal was much higher than those in other multiferroics7,8. It may be interesting to compare the magnetoelectric response in this material with that in hexaferrite, which is another class of high-temperature multiferroics. In some materials of hexaferrite, the polarization reversal by the sign reversal of the magnetic field was achieved, while in other hexaferrites, the polarization cannot be reversed3,4,5,6,7,8,26,27,28,29,30. In the case of Tb2(MoO4)3, the polarization is unchanged by the sign change of the magnetic field. In this sense, the magnetoelectric response in Tb2(MoO4)3 is similar to the latter class of hexaferrite. Nevertheless, Tb2(MoO4)3 has unique magnetoelectric properties, which is not realized in any hexaferrite; the ferroelectric polarization can be aligned only by a magnetic field. As shown in Fig. 2c, the cooling in a magnetic field, even without any electric field, can align the ferroelectric polarization. This functionality originates from the lack of inversion symmetry even in the paraelectric state above Tc = 432 K.

Discussion

In summary, we have successfully demonstrated magnetic control of ferroelectric polarization at 430 K. To our knowledge, this is the highest temperature at which magnetic reversal of ferroelectric polarization has been observed. While the spin-dependent metal-ligand hybridization mechanism was proposed as a mechanism of related multiferroic compounds such as Ba2CoGe2O721,42, the expected small hybridization to the localized Tb 4f state does not support it as the mechanism of magnetoelectric response in the present material. Because the Tb3+ ion is known for its strong magnetoelastic coupling36,37, the combination of piezoelectricity and magnetoelastic coupling is most likely the mechanism of magnetoelectric response in this system.

While the piezoelectric effect was observed only in the ferroelectric state for Tb2(MoO4)331, it should be active even in the nonpolar but noncentrosymmetric high-temperature state with \(\bar{4}2m\) point group. The finite magnitude of piezoelectricity is ensured by the symmetry. In the high-temperature state, the c-axis polarization induced by the strain can be written as

Here, Pi is the i component of the polarization vector and εij is the ij component of the strain tensor, and x-,y-, and z-axes are parallel to the a-, b-, and c axis in the Tb2(MoO4)3 crystal. α is a constant. In the \(x^{\prime} y^{\prime} z\) coordinate system where the xyz coordinate system is rotated 45 degrees around the z-axis,

Therefore, Pz can be induced by the uniaxial strain along the diagonal directions (\({\varepsilon }_{{x}^{\prime}{x}^{\prime}}\), \({\varepsilon }_{{y}^{\prime}{y}^{\prime}}\)) in the high-temperature region. On the other hand, any magnetic material shows the magnetoelastic effect; strain should depend on the direction of magnetization43,44. Compounds with Tb magnetic moments tend to have a large magnitude of magnetoelastic coupling45. For simplicity, let us first assume uniform media. The magnetoelastic energy can be written as

Here, mi is i component of magnetization vector m, and A is a constant. For \({{{\bf{m}}}}=(1/\sqrt{2},1/\sqrt{2},0)\), \({U}_{{{{\rm{el}}}}}=\frac{A}{2}({\varepsilon }_{xx}+{\varepsilon }_{yy}+2{\varepsilon }_{xy})=A{\varepsilon }_{{x}^{\prime}{x}^{\prime}}\), and, for \({{{\bf{m}}}}=(1/\sqrt{2},-1/\sqrt{2},0)\), \({U}_{{{{\rm{el}}}}}=\frac{A}{2}({\varepsilon }_{xx}+{\varepsilon }_{yy}-2{\varepsilon }_{xy})=A{\varepsilon }_{{y}^{\prime}{y}^{\prime}}\). Thus, the strain should be induced along the magnetization. For the actual Tb2(MoO4)3 crystal, because of the lower symmetry, additional components should appear in Uel, but the universal magnetoelastic response of strain along the magnetization should be predominant. Therefore, Pz can be induced by magnetic fields along the (1, 1, 0) or (1, −1, 0) directions in the high-temperature region. While the magnitude of the magnetoelastic effect is quite small in the paramagnetic state, it can still lift the degeneracy just at the transition temperature. That is why the polarization can be magnetically controlled in this system. This type of mechanism has scarcely been discussed as a multiferroic mechanism in a material36,37, while a similar mechanism has been studied in composite materials46,47,48. In this sense, this work may pave a new avenue for exploring high-temperature multiferroics.

Methods

Sample preparation

Single crystal of Tb2(MoO4)3 was grown by the floating-zone (FZ) method49. First, Tb4O7(99.9 %) and MoO3(99.9 %) powder were mixed with a molar ratio of 1:6.12. While the molecular ratio should be 1:6 to achieve the nominal ratio of Tb:Mo = 2:3 in the chemical formula of Tb2(MoO4)3, the excess of 2 wt% of MoO3 was added to compensate for the volatilization of MoO3 in the FZ process. Tb2(MoO4)3 was synthesized by sintering the mixture in air at 700 °C for 24 hours twice and at 1000 °C three times. The powder was pressed into a rod with a diameter of 6 mm and a length of 110 mm and sintered in air several times at 1000 °C for 10 hours. The rod was crystalized by means of floating-zone method in the air with a growth speed of 2.0–3.0 mm h−1 and a rotation speed of 12–15 rpm. While the grown crystal was composed of several domains, we could extract several single crystals with the size of a few millimeters. The single crystallinity was confirmed by X-ray diffraction and Laue camera (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). The specimens were annealed in air at 1000 °C to remove the possible stress and slowly cooled down to room temperature at a rate of 10 °C h−1. We expect the annealing process to eliminate the disorder of crystal introduced during crystal growth. In general, the cooling speed in the floating-zone method is higher than that in other methods such as the flux method and the vaper transport method, which may result in the disorder of crystal. We found the ferroelectric domain structures were changed after annealing, which may be caused by the reduction of disorder (Supplementary Fig. 3). For the measurements of dielectric constant and polarization, we used a rectangular single crystal with the size of 0.73 × 1.28 × 0.46 mm3. As electrodes, gold was deposited on the widest surfaces, which is parallel to the (001)t plane.

Polarization and dielectric constant measurements

We measured the polarization and the dielectric constant with a cryogen-free superconducting magnet in the High Field Laboratory for Superconducting Materials (HFLSM), Institute for Materials Research (IMR), Tohoku University. The experimental configuration is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4 in Supplementary Information50. The sample probe was inserted into the room-temperature bore of the magnet. Temperature control was performed using a temperature controller (Lakeshore 350), a resistance heater, and a platinum resistance thermometer (INNOVATIVE SENSOR TECHNOLOGY P1K0.161.6W.A.010). The standard calibration curve PT-1000 preloaded in Lakeshore 350 was used to obtain the sample temperature, and the precision was ~0.1 K.

The temperature dependence of the dielectric constant at 1 kHz was measured using a capacitance bridge (Andeen-Hagerling 2700A). Electric polarization was obtained by the integration of measured displacement current. The displacement current was measured using an electrometer (Keithley 6517). A small background current (~0.1 pA) was estimated above the ferroelectric temperature and subtracted from the measured electric current. The electrometer and platinum resistance thermometer were brought from Onose Lab., IMR, Tohoku University. Other instruments belong to HFLSM.

Data availability

All the data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Kimura, T. et al. Magnetic control of ferroelectric polarization. Nature 426, 55–58 (2003).

Scott, J. F. Room-temperature multiferroic magnetoelectrics. NPG Asia Mater. 5, e72 (2013).

Kitagawa, Y. et al. Low-field magnetoelectric effect at room temperature. Nat. Mater. 9, 797–802 (2010).

Okumura, K. et al. Magnetism and magnetoelectricity of a U-type hexaferrite Sr4Co2Fe36O60. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 212504 (2011).

Chun, S. H. et al. Electric field control of nonvolatile four-state magnetization at room temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 177201 (2012).

Okumura, K., Haruki, K., Ishikura, T., Hirose, S. & Kimura, T. Multilevel magnetization switching by electric field in c-axis oriented polycrystalline Z-type hexaferrite. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 032906 (2013).

Hirose, S., Haruki, K., Ando, A. & Kimura, T. Mutual control of magnetization and electrical polarization by electric and magnetic fields at room temperature in Y-type BaSrCo2−xZnxFe11AlO22 ceramics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 022907 (2014).

Kocsis, V. et al. Magnetization-polarization cross-control near room temperature in hexaferrite single crystals. Nat. Commun. 10, 1247 (2019).

Scott, J. F. Multiferroic memories. Nat. Mater. 6, 256–257 (2007).

Bibes, M. & Barthélémy, A. Towards a magnetoelectric memory. Nat. Mater. 7, 425–426 (2008).

Roy, A., Gupta, R. & Garg, A. Multiferroic memories. Adv. Condens. Matter Phys. 2012, 926290 (2012).

Fusil, S., Garcia, V., Barthélémy, A. & Bibes, M. Magnetoelectric devices for spintronics. Ann. Rev. Mater. Res. 44, 91–116 (2014).

Spaldin, N. A. & Ramesh, R. Advances in magnetoelectric multiferroics. Nat. Mater. 18, 203–212 (2019).

Gupta, R. & Kotnala, R. K. A review on current status and mechanisms of room-temperature magnetoelectric coupling in multiferroics for device applications. J. Mater. Sci. 57, 12710–12737 (2022).

Khomskii, D. Classifying multiferroics: mechanisms and effects. Physics 2, 20 (2009).

Yakout, S. M. Spintronics and innovative memory devices: a review on advances in magnetoelectric BiFeO3. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 34, 317–338 (2021).

Yamasaki, Y. et al. Magnetic reversal of the ferroelectric polarization in a multiferroic spinel oxide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 207204 (2006).

Kimura, T., Lashley, J. C. & Ramirez, A. P. Inversion-symmetry breaking in the noncollinear magnetic phase of the triangular-lattice antiferromagnet CuFeO2. Phys. Rev. B 73, 220401 (2006).

Taniguchi, K., Abe, N., Takenobu, T., Iwasa, Y. & Arima, T. Ferroelectric polarization flop in a frustrated magnet MnWO4 induced by a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 097203 (2006).

Seki, S., Onose, Y. & Tokura, Y. Spin-driven ferroelectricity in triangular lattice antiferromagnets ACrO2 (A = Cu, Ag, Li, or Na). Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 067204 (2008).

Murakawa, H., Onose, Y., Miyahara, S., Furukawa, N. & Tokura, Y. Ferroelectricity induced by spin-dependent metal-ligand hybridization in Ba2CoGe2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 137202 (2010).

Sagayama, H. et al. Correlation between ferroelectric polarization and sense of helical spin order in multiferroic MnWO4. Phys. Rev. B 77, 220407 (2008).

Saito, M., Ishikawa, K., Konno, S., Taniguchi, K. & Arima, T. Periodic rotation of magnetization in a non-centrosymmetric soft magnet induced by an electric field. Nat. Mater. 8, 634–638 (2009).

Soda, M., Kimura, K., Kimura, T., Matsuura, M. & Hirota, K. Electric control of spin helicity in multiferroic triangular lattice antiferromagnet CuCrO2 with proper-screw order. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 78, 124703 (2009).

Tokunaga, Y., Taguchi, Y., Arima, T. & Tokura, Y. Electric-field-induced generation and reversal of ferromagnetic moment in ferrites. Nat. Phys. 8, 838–844 (2012).

Kimura, T., Lawes, G. & Ramirez, A. P. Electric polarization rotation in a hexaferrite with long-wavelength magnetic structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 137201 (2005).

Ishiwata, S., Taguchi, Y., Murakawa, H., Onose, Y. & Tokura, Y. Low-magnetic- field control of electric polarization vector in a helimagnet. Science 319, 1643–1646 (2008).

Tokunaga, Y. et al. Multiferroic M-type hexaferrites with a room-temperature conical state and magnetically controllable spin helicity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 257201 (2010).

Chai, Y. S. et al. Electrical control of large magnetization reversal in a helimagnet. Nat. Commun. 5, 4208 (2014).

Chai, Y. S., Chun, S. H., Cong, J. Z. & Kim, K. H. Magnetoelectricity in multiferroic hexaferrites as understood by crystal symmetry analyses. Phys. Rev. B 98, 104416 (2018).

Keve, E. T., Abrahams, S. C., Nassau, K. & Glass, A. M. Ferroelectric ferroelastic paramagnetic terbium molybdate β-Tb2(MoO4)3. Solid State Commun. 8, 1517–1520 (1970).

Dorner, B., Axe, J. D. & Shirane, G. Neutron-scattering study of the ferroelectric phase transformation in Tb2(MoO4)3. Phys. Rev. B 6, 1950 (1972).

Abrahams, S. C., Bernstein, J. L., Lissalde, F. & Nassau, K. Thermal expansivity and spontaneous stain temperature dependence in Tb2(MoO4)3. J. Appl. Cryst. 11, 699–700 (1978).

Svensson, C., Abrahams, S. C. & Bernstein, J. L. Ferroelectric–ferroelastic Tb2(MoO4)3: room temperature crystal structure of the transition-metal molybdates. VII. J. Chem. Phys. 71, 5191–5195 (1979).

Fisher, R. A., Hornung, E. W., Brodale, G. E. & Giauque, W. F. Magnetothermodynamics of ferroelectric, ferroelastic, antiferromagnetic β-terbium molybdate. I. Heat capacity, entropy, magnetic moment of the electrically polarized form from 0.4 to 4.2 °K with fields to 90 kG along the c crystal axis. J. Chem. Phys. 63, 1295–1308 (1975).

Wiegelmann, H., Ponomarev, B. K., Van Tol, J., Jansen, A. G. M., Wyder, P. & Red’kin, B. S. Magnetoelectric properties of ferroelectric rare earth molybdates. Ferroelectrics 183, 195–204 (1996).

Ponomarev, B. K., Ivanov, S. A., Popov, Y. F., Negrii, V. D. & Red’Kin, B. S. Magnetoelectric properties of some rare earth molybdates. Ferroelectrics 161, 43–48 (1994).

Abrahams, S. C., Svensson, C. & Bernstein, J. L. Ferroelectric–ferroelastic Tb2(MoO4)3 crystal structure temperature dependence from 298 K through the transition at 436 K to the antiferroelectric–paraelastic phase at 523 K. J. Chem. Phys. 72, 4278–4285 (1980).

Saito, M., Taniguchi, K. & Arima, T. Gigantic optical magnetoelectric effect in CuB2O4. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 77, 013705 (2008).

Kézsmárki, I. et al. Enhanced directional dichroism of terahertz light in resonance with magnetic excitations of the multiferroic Ba2CoGe2O7 oxide compound. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 057403 (2011).

Borchardt, H. J. & Bierstedt, P. E. Ferroelectric rare-earth molybdates. J. Appl. Phys. 38, 2057–2060 (1967).

Arima, T. Ferroelectricity induced by proper-screw type magnetic order. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 76, 073702 (2007).

Chikazumi, S. Physics of ferromagnetism. (Oxford, 1997).

Landau, L. D. & Lifshitz, E. M. Electrodynamics of continuous media. (Oxford, 1984).

Nii, Y. et al. Elastic study of electric quadrupolar correlation in the paramagnetic state of the frustrated quantum magnet Tb2+δTi2−δO7. Phys. Rev. B 105, 094414 (2022).

Suchtelen, J. V. Product properties: a new application of composite materials. Philips Res. Rep. 27, 28–37 (1972).

Van Run, A. M. J. G., Terrell, D. R. & Scholing, J. H. An in situ grown eutectic magnetoelectric composite material Part 2 physical properties. J. Mater. Sci. 9, 1710–1714, (1974).

Nan, C.-W., Bichurin, M. I., Dong, S., Viehland, D. & Srinivasan, G. Multiferroic magnetoelectric composites: historical perspective, status, and future directions. J. Appl. Phys. 103, 031101 (2008).

Shikanai, F., Tsukada, S. & Akishige, Y. Single crystal growth of β-Tb2(MoO4)3 and its evaluation. Ferroelectrics 511, 82–87 (2017).

Kimura, S. et al. Ferroelectricity by bose-einstein condensation in a quantum magnet. Nat. Commun. 7, 12822 (2016).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Cryst. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The measurements were carried out at the High Field Laboratory for Superconducting Materials, IMR, Tohoku University (proposal number 202312-HMKPA-0401). We thank Professor Fujita, Prof. Nojima, and Prof. Umetsu for their help with X-ray diffraction measurements. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI(Grants No. JP20K03828, No. JP21H01036, No. JP22H04461, No. JP23K13654, No. JP24H01638, No. JP24H00189, No. 21H01026, No. 23H04863, and No. 23K17660), JST SPRING(Grant No. JPMJSP2114), and JST PRESTO (Grant No. JPMJPR19L6). S.T. acknowledges support from GP-Spin at Tohoku University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T. carried out the crystal growth and the measurements of dielectric constant and electric polarization with assistance from H.M., Y.N., and S.K.S.T. and Y.O. wrote the paper through the discussion and assistance from H.M., Y.N., and S.K. The project was conceived and supervised by Y.O.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications materials thanks Cristina González-Silgo and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Aldo Isidori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tajima, S., Masuda, H., Nii, Y. et al. A high-temperature multiferroic Tb2(MoO4)3. Commun Mater 5, 267 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00717-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00717-8