Abstract

Strain-induced α” martensitic phase transformation (SIMT) critically affects the mechanical properties of metastable β titanium alloys. In this study, the effects of β grain size and oxygen content on SIMT in a Ti-12wt.%Mo alloy were systematically investigated. It is found that SIMT is promoted by a decrease in grain size and in oxygen content. The mechanistic origins of the anomalous grain size dependency and the acute oxygen content dependency of SIMT are discussed based on multi-scale microstructural characterization and state-of-the-art simulations. In the Ti-12wt.%Mo alloy, in-situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction analysis reveals that SIMT occurs before macroscopic yielding and only leads to elastic deformation of the surrounding β matrix due to the small transformation strain. Therefore, grain refinement does not raise the energy barrier for SIMT but rather provides more nucleation sites for strain-induced α” martensite, thereby promoting SIMT in fine-grained Ti-12wt.%Mo alloy. In contrast, for the Ti-12wt.%Mo-0.3 wt.%O alloy, oxygen atoms substantially increase the energy barrier for SIMT, due to a change in the local configuration of oxygen atoms during the phase transformation. In addition, atom probe tomography reveals for the first time that oxygen atoms segregate at α”/β phase boundaries, thereby further restricting the growth of α” martensite.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Owing to their excellent strain-hardening capability, low density and good biocompatibility, metastable β titanium alloys have great potential for applications for the aerospace, automotive and biomedical industries1,2. The excellent strain-hardening capability of metastable β titanium alloys originates from strain-induced phase transformations (specifically the β-to-α” and β-to-ω phase transformations) and from deformation twinning (most commonly on the {332} < 113> and/or {112} < 111> twinning systems), referred to commonly as transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP) and twinning-induced plasticity (TWIP) effects, respectively. On the basis of a semi-empirical alloy design approach (“d-electron alloy design”3,4), the TRIP and TWIP effects of metastable β titanium alloys can be tailored, giving rise to the development of various alloy systems (such as Ti-Mo5,6, Ti-Mo-W7, Ti-Cr-Sn8,9 and Ti-Cr-Al-Fe10, to name a few) with differing combinations of desired mechanical properties. Among them, the Ti-12Mo (wt.%) alloy is one of the most intensively investigated over the last decade5,6. This alloy typically has a yield strength of 400–500 MPa and a uniform elongation of more than 30% at room temperature. The main deformation mechanisms of the Ti-12Mo alloy are strain-induced α” martensitic phase transformation (SIMT) and {332} < 113> deformation twinning5. Recently, with the purpose of further expanding its application as a structural material, several attempts have been made to increase the yield strength of Ti-12Mo alloy, including substitutional alloying7,8,9 and low temperature aging11. These approaches, however, only resulted in a moderate increase in the yield strength, and in each case at the cost of a loss in uniform elongation7,8,9,10,11. Thus, a deeper understanding of the deformation mechanisms is necessary for achieving both high yield strength and larger uniform elongation in the metastable Ti-12Mo alloy.

Similar to TWIP steels12, continuously formed {332} < 113> deformation twin boundaries in Ti-12Mo provide obstacles against dislocation movement, leading to a dynamic Hall-Petch effect and high values of strain-hardening rate over a large strain range. In contrast, the role of strain-induced α” martensite in the strain hardening of Ti-12Mo is still not fully understood. Although the α”/β phase boundaries introduced by newly formed α” martensite can also block dislocations, the elastic and plastic micromechanical properties of α” martensite itself should also be taken into consideration. Recently, through in-situ straining experiments combined with high-energy synchrotron X-ray diffraction13, we found that α” martensite in Ti-12Mo was in fact much softer than the parent β phase. As such the formation of excessive amounts of α” martensite has a negative impact on tensile strength. The α” martensite possesses an orthorhombic structure (space group: Cmcm), which can be derived from the body-centered cubic (bcc) lattice of the parent β phase by a {11-2} < 111> shear and a {0-11} < 011> shuffle with a relatively small shuffle amplitude14,15. In Ti-12Mo with a coarse β grain size (larger than 50 µm), strain-induced α” martensite was frequently observed either adjacent to {332} < 113> twin boundaries or at twin intersections7,9,10, where this phenomenon was ascribed to the high local stress/strain field at those sites.

The SIMT in metastable β titanium alloys can be affected by both the grain size and oxygen content. Concerning the effect of grain size, Bhattacharjee et al.16 investigated the grain size dependence (over the range 130–475 µm) on the triggering stress (the stress at which α” martensite first appears) in a β-solution treated Ti-10V-2Fe-3Al alloy16, a cornerstone metastable β titanium alloy. It was found that the triggering stress increased with increasing β grain size up to a grain size of 300 µm, after which it became constant. However, an opposite tendency was reported by Paradkar et al.17 in their study of a Ti-18Al-8Nb alloy over a grain size range of 300–1600 µm. Moreover, Cai et al.18 fabricated fine-grained (1.3–30 µm) metastable Ti-16V-3.5Al-3Sn alloys through the stress-induced martensite and its reverse transformation. By tensile tests, it was found that as the grain size increased, the triggering stress decreased to a minimum and then increased, resulting in a U-shaped curve for the dependence of grain-size on triggering stress.

Regarding the effect of oxygen content, Bortolan et al.19 investigated the effect of oxygen content (0.04–0.18 wt.%) on the mechanical properties and plastic deformation mechanisms of the Ti-12Mo alloy. It was found that, independent of the oxygen content, {332} < 113> twins and strain-induced α” martensite occurred in the deformed microstructures. In another study covering a wider range of oxygen content (0.1–0.4 wt.%), Min et al.20 reported a gradual transition of deformation mode in Ti-10Mo from strain-induced α” martensitic transformation to {332} < 113> deformation twinning, and then to dislocation slip with increasing oxygen content, leading to an increase in strength but a decrease in ductility. A similar tendency was also reported in a higher Mo content (15.0 wt.%) alloy system21.

These significantly varying, and sometimes even contradictory, reports concerning the effects of grain size and oxygen content on the SIMT behaviors in metastable β titanium alloys stimulate a more comprehensive and in-depth investigation on this topic. To this end, we have systematically evaluated the deformation microstructures of a Ti-12Mo alloy with a wide range of grain size (4.5–100 µm) and oxygen content (0.1–0.3 wt.%). The results reveal that SIMT in this alloy is promoted by a decrease in grain size and oxygen content. Based on in-situ tensile deformation with synchrotron X-ray diffraction and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), we attribute the anomalous grain size dependency of SIMT to the unique characteristics of strain-induced α” martensite in Ti-12Mo alloy. Combined with atom probe tomography (APT) and density functional theory (DFT) calculations, the mechanistic origin of the suppression effect of oxygen interstitial on SIMT is also thoroughly clarified for the first time. These new insights into SIMT can benefit the further development of metastable β titanium alloys with improved mechanical performance.

Results

Effects of grain size and oxygen content on SIMT behavior in Ti-12Mo-O alloys

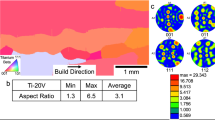

Fully recrystallized β single-phase microstructures (without remanent α” phase) with mean grain sizes ranging from 4.5 µm to 100 µm were successfully obtained by HPT followed by annealing for both the Ti-12Mo-0.1 O and Ti-12Mo-0.3 O alloys. The relationship between annealing parameters and mean grain size is summarized in Table 1. In our previous study13, athermal ω (ωath) precipitates were confirmed in both alloys regardless of the grain size (see the synchrotron XRD patterns in Fig. S1). EBSD phase maps (β phase in green, α” phase in red, and the same hereafter) of the undeformed Ti-12Mo-0.1 O microstructures (similar for Ti-12Mo-0.3 O microstructures) with different mean grain size are shown in Fig. 1a-1–a-6. A fairly uniform grain size distribution was obtained in both alloys.

a-1–a-6 Phase maps (β phase: green, α” phase: red) of the initial microstructures for the Ti-12Mo-0.1 O and Ti-12Mo-0.3 O alloys with different grain sizes. Phase maps of the deformed microstructures after a plastic strain of 6.0% for Ti-12Mo-0.1 O (b-1)–(b-6) and Ti-12Mo-0.3 O (c-1)–(c-6). The area fraction of the strain-induced α” phase is indicated for each deformed microstructure. The tensile direction was horizontal for all microstructures.

EBSD phase maps of the deformed Ti-12Mo-0.1 O and Ti-12Mo-0.3 O microstructures after a plastic strain of 6.0% are shown in Fig. 1b-1–b-6 and Fig. 1c-1–c-6, respectively. The area fraction of strain-induced α” martensite, f (α”) is indicated for each microstructure. The “band-like” structures not-indexed as α” phase were confirmed to be {332} < 113> deformation twins. Two typical examples of deformation twinning-dominant microstructures in coarse-grained (CG) (D = 30 μm) Ti-12Mo-0.1 O and Ti-12Mo-0.3 O alloys are shown in Fig. S2. A high density of deformation twin boundaries (shown as blue lines in Fig. S2(b) and (e)) can be clearly observed, associated with a misorientation angle of 51° (Fig. S2(c) and (f)), which is characteristic of {332} < 113> twinning in metastable β titanium alloys. Both {332} < 113> twin boundaries and α”/β phase boundaries served as effective barriers against mobile dislocations, the main carrier of plastic deformation in metastable β titanium alloys, thus contributing to the strain-hardening of the material.

In the deformed Ti-12Mo-0.1 O microstructures (Fig. 1b-1–b-6), it is interesting to note that f (α”) gradually increases with decreasing grain size, from f (α”) = 4.4% in the microstructure with a grain size of 100 µm to f (α”) = 55.6% in that with a grain size of 4.5 µm. At the same time, the area fraction of {332} < 113> deformation twins, f (twin) continuously decreases with decreasing grain size. As a result, the dominant deformation mechanism changes from {332} < 113> deformation twins in CG microstructures to strain-induced α” martensite in fine-grained (FG) microstructures in the Ti-12Mo-0.1 O alloy. A quantitative plot showing the evolution of f (α”) and f (twin) with grain size in Ti-12Mo-0.1 O is shown in Fig. S3, where a rapid increase in f (α”) is seen for grain sizes below 30 µm. In contrast, in the deformed Ti-12Mo-0.3 O microstructures (Fig. 1c-1–c-6), f (α”) remains approximately constant with decreasing grain size at a relatively low level (f (α”) ≤ 8.0%). This indicates a dominant deformation mechanism of {332} < 113> deformation twinning in Ti-12Mo-0.3 O regardless of the grain size. From a quantitative analysis (Fig. S3), f (twin) in Ti-12Mo-0.3 O (after a plastic strain of 6.0%) was ~25%, even in the finest microstructure.

From the above microstructural observations, two critical characteristics of SIMT can be inferred for Ti-12Mo-O alloy. First, SIMT is greatly promoted by decreasing β grain size in the Ti-12Mo-O alloy with a low oxygen content. This tendency is opposite to that commonly reported in austenitic TRIP steels22,23,24,25, where strain/stress induced α’ martensite is generally suppressed by decreasing the austenite grain size. Second, SIMT is substantially suppressed by increasing oxygen content, the effect of which clearly surpasses that of grain size, as only a few α” martensite volumes were observed in FG (D = 4.5 µm) Ti-12Mo-0.3 O after deformation (Fig. 1c-1). The mechanistic origins of these two characteristics will be explored in the discussion section of this paper.

Characteristics of strain-induced α ” martensite

Before discussing the underlying mechanisms of how grain size and oxygen content affect the SIMT behavior in the Ti-12Mo-O alloy, we carried out a multiscale microstructural characterization of the strain-induced α” martensite in FG (D = 4.5 μm) Ti-12Mo-0.1 O and Ti-12Mo-0.3 O alloys, as illustrated in Fig. S4. EBSD inverse pole figure (IPF) maps of the deformed microstructures after a plastic strain of 2.0% are shown in Fig. S4(a) and (e), respectively. The corresponding phase maps (β phase: green, α” phase: red) are shown in Fig. S4(b) and (f), respectively. It is clearly shown that most of the α” martensite plates in the FG Ti-12Mo-0.1 O microstructure (Fig. S4(a) and (b)) exhibited an isolated distribution, whereas in the FG Ti-12Mo-0.3 O counterpart (Fig. S4(e) and (f)), α” martensite plates either displayed an isolated distribution (e.g. area A) or formed conjunctionally with deformation twins (e.g. area B). The conjunctional distribution of α” martensite with deformation twins has been reported in previous studies of metastable β titanium alloys26 and was explained by the assumption that α” martensite can serve as a nucleation site for deformation twinning, or vice versa.

To further characterize the fine-scale microstructural features of α” martensite, areas of interest (marked by white dashed rectangles in Fig. S4(a) and (e) were extracted using a FIB lift-out technique (Fig. S4(c) and (g)) such that the plane normal of the extracted TEM sample was parallel to that of the EBSD specimen (in contrast to the conventional technique where the plane normal of the extracted TEM sample and EBSD/SEM specimen are generally perpendicular). The required lift-out procedure is more complex but allows a direct comparison of TEM and EBSD images taken from the same area. In FG Ti-12Mo-0.1 O, the α” martensite in Grain A (Fig. S4(a) and (d)) was characterized in detail, while in FG Ti-12Mo-0.3 O, the α” martensite in areas A and B (Fig. S4(e) and (h)) was carefully analyzed. Note the mirror asymmetry between the EBSD-IPF maps (Fig. S4(a) and (e)) and TEM images (Fig. S4(d) and (h)), due to the reversed viewing direction after FIB sample preparation.

In FG Ti-12Mo-0.1 O, two groups of strain-induced α” martensite, nearly perpendicular to each other, were found in Grain A (Fig. S4(d)). At the interface between the α” martensite and the β matrix (βmatrix), an intermediate β layer (βint) was found, a phenomenon universally observed for all α” martensite plates with different orientations and thicknesses in this microstructure. One typical example is shown in Fig. 2a, where βint with a thickness of ~20 nm was found on both sides of a thin α” martensite plate. Microdiffraction patterns taken from the α” martensite, βint and βmatrix regions (marked by circles with green, yellow and red colors in Fig. 2a are shown in Fig. 2b–d, respectively, along with drawings showing the indexed diffraction patterns. In βmatrix (Fig. 2d), the diffraction intensities of the two ω variants (ω1 and ω2) are nearly identical, indicating an equal probability of the two variants of ωath precipitates. However, in βint (Fig. 2c)), the diffraction intensity of one ω variant (ω1) is much stronger than the other (ω2), indicating here in this specific case that the ω1 variant was preferred over the ω2 variant in the intermediate layer. For the α” martensite (Fig. 2b), only the diffraction pattern from orthorhombic structure was detected, suggesting a disappearance of ωath precipitates in α” martensite.

STEM characterization of isolated α” martensite in FG (D = 4.5 μm) Ti-12Mo-0.1 O (a–g) and Ti-12Mo-0.3 O (h–l) alloys after a plastic strain of 2.0%. In FG Ti-12Mo-0.1 O, diffraction patterns together with the key diagrams, taken from α” martensite (green circle in (a)), β intermediate layer (yellow circle) and β matrix (red circle) are shown in (b)–(d), respectively. In FG Ti-12Mo-0.3 O, diffraction patterns together with the key diagrams, taken from α” martensite (green circle in (h)) and β matrix (red circle) are shown in (i)–(j), respectively. e–g STEM images of FG Ti-12Mo specimen tilted to different β zone axis. k STEM image of FG Ti-12Mo-0.3 O specimen with the zone axes of [110]β. Magnified image of the rectangled region is shown in (l), in which misfit dislocations were indicated by white arrows. Microdiffraction technique (with an electron probe size about 1 nm) was used to identify each region. Note that the vertical lines in (k) and (l) are the artifacts caused by sample preparation using FIB.

Such a unique three-layered (α”-βint-βmatrix) structure of α” martensite has not previously been reported for metastable β titanium alloys. This complex structure can be attributed to the small magnitude of the transformation strain for the β-to-α” phase transformation14,15. Due to the lattice constants and crystallographic orientation relationship ((110)α”//(112)β and [001]α”//<110>β) between the two phases, both the volume change and transformation strain of the β-to-α” phase transformation are trivially small. Thus, it is plausible that only elastic deformation (without the requirement of plastic deformation) of the surrounding β phase is needed to accommodate the small volume change/transformation strain in Ti-12Mo-0.1 O alloy, which in turn leads to the formation of an intermediate β layer. The elastic strain and stress field within this intermediate β layer may additionally result in a preferential removal of one variant along the shear stress direction, without affecting other the other variant. The elastic deformation of the intermediate β layer was further confirmed by the absence of misfit dislocations at the α”/β interface. By tilting the TEM specimen to different zone axes of the β phase ([110]β, [111]β and [331]β) (Fig. 2e–g), hardly any dislocations can be found in the β phase adjacent to the α”/β interfaces over a large area of view.

In FG Ti-12Mo-0.3 O, two types of α” martensite can be identified (Fig. 3a and b), namely type I with an isolated distribution (similar to those in FG Ti-12Mo-0.1 O microstructure (Fig. S4(a) and (b)) and type II with a conjunctional distribution. An HRTEM image of type I α” martensite in Ti-12Mo-0.3 O (with a thickness of ~36 nm) is shown in Fig. 2h. In sharp contrast to the α” martensite in Ti-12Mo-0.1 O, no intermediate β layer was found on either side of the α” martensite in Ti-12Mo-0.3 O, as further confirmed by microdiffraction analysis (Fig. 2i and j). In the β matrix close to the α”/β interface, the diffraction intensities of two ω variants are nearly identical to each other (Fig. 2i). Moreover, a certain number of misfit dislocations are found near the α”/β interface (Fig. 2k and l), a strong indicator of the plastic deformation in β phase to accommodate the β-to-α” transformation strain in the Ti-12Mo-0.3 O alloy. Oxygen interstitials in the β phase substantially raise the energy barrier of the β-to-α” phase transformation (the detailed mechanism will be discussed in section 4.2), such that the transformation strain exceeds the elastic limit of the β phase, causing plastic deformation of the surrounding β phase in the Ti-12Mo-0.3 O alloy. In this circumstance, misfit dislocations form and help to relax the strain/stress field, and no intermediate β layer forms at the α”/β interface of the Ti-12Mo-0.3 O alloy.

IPF map (a) and phase map (b) of FG (D = 4.5 μm) Ti-12Mo-0.3 O alloy deformed by a plastic strain of 2.0%. Two types of α” martensite (type I: isolated distribution, type II: conjunctional distribution) are indicated by yellow and white arrows, respectively. c STEM image of type II α” martensite. d Magnified image of the area marked by white rectangle in (c), and diffraction patterns from regions ①-⑤ are shown in (e)–(i). Microdiffraction technique (with an electron probe size about 1 nm) was used to identify each region. Note that the vertical lines in (c) and (d) are the artifacts caused by sample preparation using FIB.

The type II α” martensite in FG Ti-12Mo-0.3 O displays a ‘sandwich’ structure together with deformation twins, i.e., two α” martensite plates wrap one deformation twin in the center, as indicated by white arrow in Fig. 3a and b. A corresponding STEM image of this region is shown in Fig. 3c. Zooming in on the area marked by a white rectangle, the detailed microstructure (Fig. 3d) is seen to be even more complex. According to the microdiffraction patterns (Fig. 3e–i) of locations marked by ①-⑤, a four-layered structure is revealed, specifically, twin/α” martensite/twin/α” martensite, from right to left. Based on the spatial distribution of these layers, we may speculate that the inner deformation twin (④) formed first, and then two α” martensite volumes (③ and ⑤) nucleated on either side of the twin, facilitated by the high local stress/strain field at the twin boundary. Later, considering the relatively large β-to-α” transformation strain in Ti-12Mo-0.3 O, a new deformation twin (②) formed adjacent to the α” martensite (③) to accommodate the interphase strain incompatibility. Deformation twins formed at this stage generally have a much finer thickness (~100 nm for ②) than those formed earlier (~800 nm for ④). It should be noted that no intermediate β layer was detected, neither at the α”/βmatrix nor α”/βtwin interfaces for this type of α” martensite in the Ti-12Mo-0.3 O alloy.

Determination of initiation strain for SIMT by in-situ synchrotron XRD analysis

The initiation strain of SIMT in metastable β titanium alloys can be precisely determined by in-situ tensile deformation combined with synchrotron X-ray diffraction. For this purpose, FG (D = 4.5 µm) Ti-12Mo-0.1 O and Ti-12Mo-0.3 O alloys were chosen. The volume fractions of strain-induced α” martensite obtained from the synchrotron X-ray diffraction data, see Materials and Experimental method for details in both microstructures were plotted against engineering strain (obtained from crosshead displacement) and are shown as blue symbols in Fig. 4. The corresponding engineering stress-strain curves are also shown by red lines in Fig. 4.

Determination of the initiation strain of SIMT in FG Ti-12Mo-0.1 O (a) and Ti-12Mo-0.3 O (b) alloys by in-situ tensile deformation with synchrotron X-ray diffraction. The volume fraction of α” martensite (blue symbols) and engineering stress (red lines) were plotted against the engineering strain (obtained by crosshead displacement that overestimates the engineering strain) for both microstructures.

In FG Ti-12Mo-0.1 O (Fig. 4a), the initiation strain (einitial ~ 3.0%) for SIMT agrees well with the upper yield point (~3.0%) in the stress-strain curve. After a formation burst of strain-induced α” martensite (vol.% (α”) ~ 20%), the stress falls, corresponding to the lower yield point (~3.5%). During the Lüders deformation region, the volume fraction of strain-induced α” martensite remains largely unchanged. This may be explained by the fact that the Lüders deformation propagated out of the area scanned by the incident X-ray beam. After the end of the Lüders deformation, the volume fraction of strain-induced α” martensite continuously increases again. The good agreement between the initiation strain of SIMT and the upper yield point suggests that macroscopic yielding FG Ti-12Mo-0.1 O is mainly caused by the formation of strain-induced α” martensite, rather than by extensive dislocation slip.

In contrast, in the FG Ti-12Mo-0.3 O alloy (Fig. 4b) where the specimen shows continuous yielding, the initiation strain for SIMT (einitial ~ 5.0%) was much larger than the macroscopic yield point (~3.8%) of the material. This indicates that compared with FG Ti-12Mo-0.1 O, the SIMT in the FG Ti-12Mo-0.3 O alloy is delayed, such that macroscopic yielding of the material is mainly caused by dislocation slip. The different initiation strains for SIMT (as well as their relations to the macroscopic yielding) are believed to play a key role in leading to distinctive grain size dependency of SIMT between the two alloys.

Discussion

Influence of grain size on SIMT behavior

In this study, we found a unique grain size dependence for SIMT in the Ti-12Mo-0.1 O alloy, with f (α”) gradually increasing with decreasing β grain size. This observation contradicts the common knowledge that grain refinement suppresses SIMT, as for example frequently reported for TRIP steels22,23,24,25. In addition, the grain size range (4.5–100 µm) in this study differs from those used in previous investigations of metastable β titanium alloys, in which the mechanical properties of typical CG microstructures (β grain size ≥50 µm) were examined.

In principle, the opposite grain size dependence for SIMT behavior originates from the different characteristics of strain-induced α” (or α’) martensite between metastable β titanium alloys and TRIP steels. In TRIP steels, the strain-induced γ-to-α’ martensitic phase transformation is accompanied by an appreciable volume expansion, which necessitates plastic deformation of austenite matrix to accommodate this transformation strain22,23,24,25. A decreasing austenite grain size leads to a strengthened matrix following the Hall-Petch relationship, rendering plastic deformation of the austenite matrix, i.e. accommodation of the transformation strain, more difficult in FG structures. As a result, a decreasing austenite grain size suppresses SIMT in TRIP steels.

However, in Ti-12Mo-0.1 O alloy, our investigations show that the strain-induced β-to-α” martensitic transformation only induces elastic deformation of the surrounding β matrix (in the form of an intermediate β layer, Fig. 2a–g), due to the much smaller transformation strain. No plastic deformation of β matrix is necessary, therefore, to accommodate the transformation strain. In such a scenario, it is reasonable that the strain-induced β-to-α” martensitic transformation will not be hindered by a decreasing β grain size in Ti-12Mo-0.1 O alloy. Instead, an increased grain boundary area fraction (associated with a smaller grain size) provides more nucleation sites for α” martensite, since grain boundaries are generally considered as preferential nucleation sites for α” martensite in metastable β titanium alloys5,11. Therefore, the nucleation of strain-induced α” martensite is promoted by decreasing the β grain size in the Ti-12Mo-0.1 O alloy.

After nucleation, the growth of α” martensite proceeds by the movement of the α”/β phase boundary. Based on the dislocation drag model of interfacial structures27,28,29, the movement of the α”/β phase boundary is opposed by dislocations and oxygen interstitials (which will be discussed in the next section) in the migration path. In the Ti-12Mo-0.1 O alloy, the effect of oxygen interstitials is minor due to a low oxygen content, leaving dislocations as the main contributor to the resistance of α”/β phase boundary movement. Misfit dislocations at the α”/β phase boundary of Ti-12Mo-0.1 O are scarce (Fig. 2e–g) and moreover, based on the synchrotron X-ray diffraction analysis (Fig. 4), the formation of α” martensite occurs before the macroscopic yielding of the β phase, i.e. the density of statistically stored dislocations (SSDs) is also low. Therefore, the resistance of dislocations against α”/β phase boundary movement is expected to be low, at least in the early stage of the growth of α” martensite. The low resistance against phase boundary movement, together with a promoted nucleation of α” martensite leads to a gradually increased f(α”) with decreasing β grain size in the Ti-12Mo-0.1 O alloy.

Finally, it is worth noting that along with an increased fraction of strain-induced α” martensite, the fraction of {332} < 113> deformation twins continuously decreases with decreasing β grain size in Ti-12Mo-0.1 O (Fig. S3), indicating a competing relationship between the two deformation mechanisms. This phenomenon can be qualitatively explained by a different grain size dependence of the critical resolved shear stress (CRSS) for activating SIMT and deformation twins (DT). The CRSS for SIMT in Ti-12Mo-0.1 O is not affected by decreasing grain size (based on the above discussion), whereas the CRSS for DT generally increases with decreasing grain size30,31. This results in a favored nucleation of SIMT over DT in FG Ti-12Mo-0.1 O. Moreover, the promoted formation of α” martensite in FG Ti-12Mo-0.1 O further subdivides β grains, rendering the nucleation of DT from retained β even more difficult.

Influence of oxygen interstitials on SIMT behavior

The results of this work also reveal an acute suppression effect of oxygen interstitials on SIMT in the Ti-12Mo-0.3 O alloy, irrespective of the grain size. This phenomenon is not new in metastable β titanium alloys13,20,21, but the underlying mechanism remains unsettled. Theoretically, oxygen interstitials can affect both the nucleation and growth of strain-induced α”martensite. In the following, we will discuss the influence of oxygen interstitials on these two processes separately.

Influence of oxygen interstitials on the energy barrier of β-to-α ” transformation

For the nucleation of α”martensite, it has been proved in our previous study13 that oxygen interstitials can significantly raise the energy barrier for the β-to-α”phase transformation, based on DFT calculations of a Ti-10 at.% Mo model alloy. Here, by a more detailed analysis of the DFT results, we find that the influence of oxygen interstitials on the energy barrier for the β-to-α”phase transformation varies dramatically for different interstitial sites (Fig. 5). For example, oxygen atoms at some interstitial sites significantly increase the energy barrier (Fig. 5a), reaching a level of 5.1–11.5 meV/atom, much larger than that (~2.0 meV/atom) in the base alloy13, whereas for oxygen atoms at some other interstitial sites the energy barrier is hardly affected (Fig. 5b). To explore the underlying mechanism for such a difference, the local configuration around oxygen atoms was tracked throughout the β-to-α”phase transformation. Representative examples showing the position of oxygen atoms during the transformation are given in Fig. 5c and d, for both the high energy barrier case (interstitial sites 2, 9) and the low energy barrier case (interstitial sites 7, 8), respectively. The left, middle and right columns display the atomic configurations in the initial β phase, the energy peak position (transitional state) and the final α” phase, respectively. It is interesting to note that for the high energy barrier case (Fig. 5c), oxygen atoms migrate from the octahedral (O) site in the initial β phase to the tetrahedral (T) site in the transition state, and then return to the octahedral site in the final α” phase. Such a complicated O-T-O migration of oxygen atom during the β-to-α”phase transformation is believed to be responsible for the high energy barrier in this case. In comparison, oxygen atoms do not migrate, i.e. remain in the octahedral site, during the whole β-to-α”phase transformation in the low energy barrier case (Fig. 5d).

a High energy barrier cases. b Low energy barrier cases. Representative atomic configurations in the initial β phase (left column), energy peak/transient state (middle column) and final α” phase (right column) of the β-to-α” transformation for the high energy barrier, sites 2, 9 (c) and low energy barrier, sites 7, 8 (d) cases, respectively. Titanium, molybdenum and oxygen atoms are shown in blue, purple and red colors, respectively. In the high energy barrier case, oxygen atom migrates from octahedral to tetrahedral (O-T) and then back to octahedral site (T-O) during the transformation.

Regarding the reason why oxygen migration occurs in some cases, but not in the others during the β-to-α”phase transformation, two possible explanations can be qualitatively discussed. Firstly, we compared the local chemical composition around the oxygen atoms between the high and low energy barrier cases. It is found in both cases that an oxygen atom at the octahedral site of initial β phase is surrounded by either 6 titanium atoms or 5 titanium atoms plus 1 molybdenum atom. Therefore, the possibility that a different local chemical composition leads to a different oxygen migration behavior can be basically ruled out. Secondly, we examined the local atomic configurations by measuring the distance between the oxygen atom and neighboring titanium/molybdenum atoms (Fig. S5). It is found that in the cases where oxygen migration (O-T-O) occurs, the oxygen-titanium or oxygen-molybdenum bond distances are slightly larger than those without oxygen migration. This indicates that a larger bond distance, i.e., a smaller bond energy, might facilitate relatively easier oxygen migration during the transformation, thereby raising the energy barrier of the β-to-α”phase transformation. Nevertheless, more calculations are still needed to clarify this issue in the future.

Influence of oxygen interstitials on the migration of α ”/β phase boundary

In addition to a raised energy barrier of the β-to-α”phase transformation, oxygen interstitials can also affect the subsequent growth of newly formed α” martensite, e.g. by pinning the phase boundary due to segregation. To verify this, an APT specimen was prepared from the α”/β phase boundary area of a FG Ti-12Mo-0.3 O sample tensile-deformed to a plastic strain of 6.0% by a site-specific lift-out method using FIB (Fig. 6a). A TEM image and selected area diffraction (SAD) patterns from the specimen before the APT experiment are shown in Fig. 6b. It is clearly seen that two α”/β phase boundaries with a distance of ~80 nm and ~200 nm from the tip are included in the APT specimen. Maps showing the atomic distribution of the major elements in this alloy (oxygen: black, molybdenum: red, titanium: purple) obtained from the APT sample are shown in Fig. 6d. Segregation of oxygen atoms along an inclined plane can be clearly observed, where the position of this plane perfectly matches that of the α”/β phase boundary at a distance of ~200 nm from the tip. Although segregation of oxygen atoms was also seen at the lower part of the α”/β phase boundary that was closer to the tip, surface oxidation effects (either during sample transfer or TEM observation) cannot be ruled out. Thus, the elemental distribution analysis of this near-tip phase boundary is not included in this study. A quantitative analysis of the oxygen segregation was carried out by plotting the elemental profiles across the lower α”/β phase boundary (far from the tip), as shown in Fig. 6c. It is seen that the peak oxygen content near the phase boundary is 2.38 at.%, much larger than that in the matrix (0.99 at.%). The approximate segregation layer thickness of oxygen atoms at the phase boundary was estimated to be ~1.5 nm (although this value may not be accurate due to the limited spatial resolution of the APT technique). It should be noted that the oxygen content in the matrix agrees well with the bulk oxygen content (0.96 at.%), which strongly confirms the accuracy of our APT results. In comparison, both the molybdenum and titanium contents across the α”/β phase boundary remain largely constant. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report so far demonstrating clear segregation of oxygen interstitials at α”/β phase boundaries in metastable β titanium alloys.

a EBSD-IPF map of β phase, where the FIB lift-out region containing strain-induced α” martensite is indicated. b TEM image of the APT tip, in which diffraction patterns of the β grain and α” martensite are shown. c Elemental profiles of Mo (blue) and O (red) atoms across the α”/β phase boundary (along the yellow line in (d)), according to the element maps of O (black), Mo (red) and Ti (purple) shown in (d).

However, considering the displacive nature of the strain-induced β-to-α” phase transformation, the observed oxygen segregation at the α”/β phase boundary is anomalous, as in principle the chemical compositions of the parent β phase and strain-induced α” phase should be the same. In addition, the time interval during tensile deformation (at a strain rate of 8.3 × 10−4 s−1) is not long enough to allow appreciable oxygen diffusion at room temperature. Thus, one possible explanation for this unusual segregation behavior is that due to the different segregation energies of oxygen atoms at the interstitial sites between the β, and α” phases, as well as the α”/β phase boundary, an entrapment of oxygen atoms takes place during the migration of the α”/β phase boundary. To explore this possibility, DFT calculations were carried out to evaluate the segregation energy of oxygen atoms at all possible interstitial sites in the β and α” phases, as well as at the α”/β phase boundary (see Materials and Methods for details), as shown in Fig. S6(a). The average values of segregation energy (E) over all interstitial sites are given in Fig. S6(b). The calculation results clearly show distinct segregation energies for these three potential locations, in descending order as Eβ > Eint > Eα”, thereby indicating that the interstitial sites at the α”/β phase boundary are preferred by oxygen atoms compared to interstitial sites in the parent β phase. As such, it is highly plausible that when the α”/β phase boundary sweeps through a parent β grain, a certain amount of oxygen atoms in parent β phase become trapped at the interstitial sites of the α”/β phase boundary due to the lower segregation energy, leading to a higher oxygen concentration at the α”/β phase boundary (Fig. S6(c)). The oxygen entrapment hypothesis can also be indirectly supported by a decrease of local oxygen concentration adjacent to the phase boundary (to the left-hand side of the phase boundary) as shown in Fig. 6c. These trapped oxygen atoms may in turn restrict the migration of the α”/β phase boundary via a solute-drag mechanism27,28,29. The restricted migration of α”/β phase boundary, together with a raised energy barrier for the β-to-α”phase transformation results in a substantial suppressed SIMT in the Ti-12Mo-0.3 O alloy.

Conclusion

To summarize, the effects of grain size and oxygen content on the SIMT behavior of Ti-12Mo-O alloys were systematically investigated in this study. The results indicate that microstructure with a finer grain size and a lower oxygen content promotes SIMT. Based on a detailed characterization of SIMT in both fine-grained Ti-12Mo-0.1 O and Ti-12Mo-0.3 O microstructures, by high-resolution TEM, in-situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction and atom probe tomography, coupled with state-of-the-art theoretical simulations, the underlying mechanisms for the grain size and oxygen content effects were clarified. It is found in the Ti-12Mo-0.1 O alloy that SIMT occurs before macroscopic yielding, and the phase transformation only induces elastic deformation of surrounding β phase. Therefore, grain refinement in Ti-12Mo-0.1 O provides more nucleation sites (possibly grain boundaries) for α” martensite, without raising the energy barrier for SIMT. In Ti-12Mo-0.3 O, oxygen atoms not only significantly raise the energy barrier for SIMT, but also retard the growth of α” martensite by segregating to the α”/β phase boundary. The former (increased energy barrier) is due to a unique local configuration change (from octahedral site to tetrahedral site and then back to octahedral site) during the phase transformation, whereas the latter (retarded growth) is driven by the different segregation energies for oxygen atoms at interstitial sites within the β phase, the α” phase and the α”/β phase boundary. These understandings can benefit the development of novel metastable β titanium alloys with optimized SIMT behavior, by tuning the grain size and oxygen content of the material.

Methods

Materials and processing

Two Ti-12wt.%Mo-O ingots with different oxygen concentrations (0.114 wt.% and 0.300 wt.%) were fabricated by argon arc melting. The corresponding atomic concentrations of oxygen were 0.36 at.% and 0.96 at.%, respectively. They are referred to hereafter as Ti-12Mo-0.1 O and Ti-12Mo-0.3 O. The detailed chemical compositions are shown in Table S1. Discs with a diameter of 20 mm and thickness of 1.0 mm were prepared from the homogenized alloys by electrical discharge machining (EDM). High pressure torsion (HPT) experiments were carried out at room temperature under a pressure of 5.0 GPa with a rotation speed of 0.2 rpm. All discs were deformed by 5 rotations. To achieve the required range of grain sizes, samples were annealed at 880–960 °C for 60–600 s followed by immediate water quenching to room temperature.

Microstructure characterization and mechanical property testing

Surfaces perpendicular to the radial direction of the HPT discs were ground and mechanically polished following standard metallographic procedures. Electro-polishing in a solution of 10% perchloric acid and 90% methanol was conducted at −30 °C using a voltage of ~20 V for 30 s, followed by a final chemical etching in a Kroll solution. Electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD) characterization was carried out using a TSL system attached to a field emission gun (SEM JEOL 7100 F), operated at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

Dog bone-shaped tensile specimens with a gauge geometry of 10.0 mm (l) × 2.0 mm (w)× 0.8 mm (t) were prepared from the discs by EDM in such a way that the center of the gauge coincided with the position at a radial distance of 5.0 mm from the center of the HPT disc. Uniaxial tensile tests were performed on a Shimadzu AG-X system with an initial strain rate of 8.3 × 10−4 s−1 at room temperature. The tensile strain was precisely measured by a digital image correlation (DIC) method, the details of which can be found elsewhere32,33. Tensile deformation experiments were interrupted at plastic strains of either 2.0% or 6.0%, followed by unloading for microstructural observation.

Samples for scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) investigations were prepared by a lift-out method from fine-grained (FG) (D = 4.5μm) Ti-12Mo-0.1 O and Ti-12Mo-0.3 O specimens after a plastic strain of 2.0%. Plane-view cross-sectional thin film samples were prepared by a SEM/FIB (focused-ion beam) micro-sampling technique to perform STEM observation from the same direction as SEM/EBSD observations in the field of view, where the microstructure was identified from SEM/EBSD imaging. Images of microstructure in the thin film samples were taken in STEM bright field (BF) mode. The instrument used was a ThermoFisher Scientific Titan Cubed G2 operated at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV and using an incident beam semi-angle of approximately 10 mrad.

In-situ synchrotron X-ray characterization

In-situ tensile experiments combined with synchrotron X-ray diffraction were conducted at the BL13XU beamline at SPring-8 in Harima, Japan. Tensile specimens having a gauge length of 10.0 mm, width of 2.0 mm and thickness of 0.6 mm were prepared from the Ti-12Mo-0.1 O and Ti-12Mo-0.3 O alloys with a grain size of 4.5 μm. The same strain rate (8.3 × 10−4 s−1) was used for the in-situ tensile experiments. Engineering strain was calculated from the crosshead displacement. An X-ray energy of 30 keV was used, corresponding to a wavelength of 0.0413 nm. The incident beam covered an area of 2.0 (w) × 0.5 (l) mm2 in the gauge part. The beam direction was perpendicular to the tensile direction. More details of the experimental methods can be found elsewhere13.

Atom probe tomography

Atom probe tomography (APT) specimens including the α”/β phase boundary were prepared from a Ti-12Mo-0.3 O specimen (D = 4.5 µm) tensile deformed to a plastic strain of 6.0% by a site-specific lift-out method using a FEI Quanta 3D 200i dual-beam focused-ion beam (FIB) instrument. Details of the experimental procedures can be found in our previous publications13. The location of the α”/β phase boundary was confirmed by both EBSD measurements before FIB lift-out and by TEM characterization after lift-out. Final tip sharpening was carried out at a voltage of 30 kV and a beam current of 300 pA, followed by a tip polishing at a voltage of 5 kV and beam current of 48 pA. The APT experiments were carried out on a local electrode atom probe (LEAP 4000) instrument from CAMECA Instruments using laser mode under ultra-high vacuum ( < 4 × 10−11 torr). Data reconstruction was performed using Integrated Visualization and Analysis Software (IVAS) version 3.8.10. Elemental profiles across the α”/β phase boundary were plotted from cylinders perpendicular to the interface using a step size of 0.5 nm.

Computational method

Oxygen segregation at the interface between β and α” phases in Ti-Mo alloy was considered in the present study. A supercell approach was employed to investigate the local configuration around individual oxygen atoms within the β and α” phases as well as at the interface. In general, it is difficult to determine the compositions of the supercell in which the β and α” phases are simultaneously stable or achieve similar energy conditions. Therefore, preliminary calculations were performed to prepare a stable interface model. Two conditions with respect to Mo concentration at which the β phase is slightly stable and the α” phase is stable at 0 K were explored. Ti-15Mo (at.%) and Ti-4Mo (at%) were chosen for the atomic model of the β and α” phases, respectively. Subsequently, a 144-atom supercell for the β phase with dimensions \({{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}=4{{{\boldsymbol{e}}}}{{\prime} }_{1}\), \({{{\boldsymbol{b}}}}=3{{{\boldsymbol{e}}}}{{\prime} }_{2}\), and \({{{\boldsymbol{c}}}}=3{{{\boldsymbol{e}}}}{{\prime} }_{3}\) was constructed, where the vectors are defined as \({{{\boldsymbol{e}}}}{{\prime} }_{1}={a}_{0}\left[100\right]\), \({{{\boldsymbol{e}}}}{{\prime} }_{2}={a}_{0}\left[0\bar{1}1\right]\), and \({{{\boldsymbol{e}}}}{{\prime} }_{3}={a}_{0}\left[01\bar{1}\right]\), with lattice constant a0. The Ti-Mo model assumed a random solid solution state. Here, random solid solutions for the composition defined above were statistically modelled by the special quasirandom structures (SQS). The Automated Toolkit for Alloy Theory (ATAT)34 were employed and “mcsqs” function based on Monte Carlo algorithm was used to find the SQS, where the pair within the third nearest neighbour distances and the triplet within the second nearest neighbour were considered as the clusters. The atomic model for the α” phase was prepared similarly, but displacements corresponding to the α” transition and to different Mo concentrations were also considered. The local atomic configurations at the interface between β and α” phase were investigated carefully by both experimental and theoretical approaches34,35. First-principles calculations indicated that the most stable interface was (110)β//(0-110)α“ interface with the “hollow2” configuration35. Accordingly, the interface model in the present study was constructed to have a “hollow2” configuration that satisfied the periodic boundary conditions along all axes as shown in Figure S7, where 144 atom supercells for β and α” phases are combined based on ref. 35. Furthermore, because of the variety of oxygen sites in the Ti-Mo model, a total of 383 different octahedral sites were selected as possible interstitial sites for oxygen. In addition, we have confirmed that the random solid solution states are reproduced well using present simulation box and that the influence of volumetric strain term during β-to- α” transformation is not so significant in our simulations.

First-principles calculations were performed within the density functional theory (DFT) framework using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)36,37. The projector-augmented wave (PAW) potentials38 were used with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) generalized gradient approximation exchange-correlation density functional39. Brillouin-zone gamma-centered k-point samplings were chosen using the Monkhorst–Pack algorithm40 with a 2 × 1 × 2 grid. A cut-off in plane-wave energy of 450 eV was applied using the first-order Methfessel–Paxton scheme with a smearing parameter of 0.2 eV. The total energy convergence tolerance was 10−6 eV. The conjugate gradient method was employed to optimize the atomic configuration, with the search terminated when the maximum force on the atoms was reduced to 0.01 eV/Å. Atomic images were visualized using the VESTA software41. Thus, statistically sufficient data allow us to discuss the stability of oxygen segregation within the β and α” phases, as well as at the α”/β interface.

Data availability

Data is available via request to the corresponding author.

References

Banerjee, D. & Williams, J. C. Perspectives on titanium science and technology. Acta Mater. 61, 844–879 (2013).

Lütjering G. & Williams,J. C. Titanium, 2nd edition, Springer, 2007.

Kuroda, D., Niinomi, M., Morinaga, M., Kato, Y. & Yashiro, T. Design and mechanical properties of new β type titanium alloys for implant materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 243, 244–249 (1998).

Hady, M. A., Hinoshita, K. & Morinaga, M. General approach to phase stability and elastic properties of β-type Ti-alloys using electronic parameters. Scr. Mater. 55, 477–480 (2006).

Sun, F. et al. Investigation of early stage deformation mechanisms in a metastable β titanium alloy showing combined twinning-induced plasticity and transformation-induced plasticity effects. Acta Mater. 61, 6406–6417 (2013).

Qian, B. N. et al. In-situ observations of a hierarchical twinning-detwinning process in stress-induced α”-martensite of Ti-12Mo alloy. Mater. Res. Lett. 10, 45–51 (2022).

Sun, F. et al. A new titanium alloy with a combination of high strength, high strain hardening and improved ductility. Scr. Mater. 94, 17–20 (2015).

Brozek, C. et al. A β-titanium alloy with extra high strain-hardening rate: Design and mechanical properties. Scr. Mater. 114, 60–64 (2016).

Lilensten, L. et al. From single phase to dual-phase TRIP-TWIP alloys: design approach and properties. Materialia 12, 100700 (2020).

Danard, Y. et al. Accommodation mechanisms in strain-transformable titanium alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 819, 141437 (2021).

Qian, B. N. et al. Mechanisms underlying enhanced strength-ductility combinations in TRIP/TWIP Ti-12Mo alloy engineered via isothermal omega precipitation. Acta Mater. 245, 118619 (2023).

Bai, Y. et al. Unique transition of yielding mechanism and unexpected activation of deformation twinning in ultrafine grained Fe-31Mn-3Al-3Si alloy. Sci. Rep. 11, 15870 (2021).

Chong, Y. et al. Oxygen interstitials make metastable β titanium alloys strong and ductile. Acta Mater. 257, 119165 (2023).

Lai, M. J., Tasan, C. C. & Raabe, D. On the mechanism of {332} twinning in metastable β titanium alloys. Acta Mater. 111, 173–186 (2016).

Lai, M. J. et al. Origin of shear induced β to ω transition in Ti-Nb-based alloys. Acta Mater. 92, 55–63 (2015).

Bhattacharjee, A., Bhargava, S., Varma, V. K., Kamat, S. V. & Gogia, A. K. Effect of β grain size on stress induced martensitic transformation in β solution treated Ti-10V-2Fe-3Al alloy. Scr. Mater. 53, 195–200 (2005).

Paradkar, A., Kamat, S. V., Gogia, A. K. & Kashyap, B. P. Trigger stress for stress-induced martensitic transformation during tensile deformation in Ti-Al-Nb alloys: effect of grain size. Metall. Mater. Trans. 39A, 551–558 (2008).

Cai, M. H., Lee, C. Y. & Lee, Y. K. Effect of grain size on tensile properties of fine-grained metastable β titanium alloys fabricated by stress-induced martensite and its reverse transformation,. Scr. Mater. 66, 606–609 (2012).

Bortolan, C. C. et al. Effect of oxygen content on the mechanical properties and plastic deformation mechanism in the TWIP/TRIP Ti-12Mo alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 817, 141346 (2021).

Min, X. H., Emura, S., Tsuchiya, K., Nishimura, T. & Tsuzaki, K. Transition of multi-deformation modes in Ti-10Mo alloy with oxygen addition. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 590, 88–96 (2014).

Min, X. H. et al. Effect of oxygen content on deformation mode and corrosion behavior in β-type Ti-Mo alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 684, 534–541 (2017).

Maki, T., Tomota, Y. & Tamura, I. Effect of grain size on the transformation-induced plasticity in metastable austenitic Fe-Ni-C alloy. J. Jpn. Inst. Metal. 38, 871–876 (1974).

Angel, T. Formation of martensite in austenitic stainless steel. J. Iron Steels Inst. 177, 165–174 (1954).

Varma, S. K., Kalyanam, J., Murr, L. E. & Srinivas, V. Effect of grain size on deformation-induced martensitic formation in 304 and 316 stainless steels during room temperature tensile testing,. J. Mater. Sci. Let. 13, 107–111 (1994).

Ulvan, E. & Koursaris, A. The effect of grain size on the bulk formability and tensile properties of austenitic stainless steel types 304 and 316. Metall. Trans. A 19, 2287–2298 (1988).

Gao, J. H. et al. Deformation mechanisms in a metastable beta titanium twinning induced plasticity alloy with high yield strength and high strain hardening rate. Acta Mater. 152, 301–314 (2018).

Olson, G. B. & Cohen, M. Interface-boundary dislocation and the concept of coherency,. Acta Metall. 27, 1907–1918 (1979).

Grujicic, M., Olson, G. B. & Owen, W. S. Mobility of martensitic interfaces. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 16, 1713–1722 (1985).

Grujicic, M., Olson, G. B. & Owen, W. S. Kinetics of martensitic interface motion. J. Phy. Colloq. 43, 173–178 (1982).

Rahman, K. M., Vorontsov, V. A. & Dye, D. The effect of grain size on the twin initiation stress in a TWIP steel. Acta Mater. 89, 247–257 (2015).

Gutierrez-Urrutia, I., Zaefferer, S. & Raabe, D. The effect of grain size and grain orientation on deformation twinning in a Fe-22wt.%Mn-0.6wt.%C TWIP steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 527, 3552–3560 (2010).

Chong, Y., Bhattacharjee, T., Park, M.-H., Shibata, A. & Tsuji, N. Factors determining room temperature mechanical properties of bimodal microstructures in Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 730, 217–222 (2018).

Chong, Y. et al. Grain refinement in titanium prevents low temperature oxygen embrittlement. Nat. Commun. 14, 404 (2023).

van de Walle, A. et al. Efficient stochastic generation of special quasirandom structures. Calphad 42, 13–18 (2013).

Li, D. D. et al. Experimental and DFT characterization of interphase boundaries in titanium and the implications for ω-assisted α phase precipitation. Acta Mater. 151, 406–415 (2018).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P.,Burke, K Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations, Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Momma, K., Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support from Elements Strategy Initiative for Structural Materials (ESISM, No. JPMXP0112101000) in Kyoto University, JST CREST (JPMJCR1994), and the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. JP15H05767, JP18H05455, JP18H05456 and JP20H00306) supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. Y.C. acknowledges the support of JSPS KAKENHI (No. JP24K08018). T.T. acknowledges the support of JST FOREST Grant Number JPMJFR213P and JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers. JP22H01762). Simulations were performed on the large-scale parallel computer system with HPE SGI 8600 at JAEA. N.T. appreciates support from the Light Metal Educational Foundation, Japan. The synchrotron X-ray diffraction experiments were performed at BL13XU in SPring-8, Harima, Japan under the beam time number of 2022A1007. Support from Prof. Yoshikazu Todaka in Toyohashi University of Technology on the HPT experiments is also appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C., A.G. and N.T. prepared the manuscript, which was reviewed and edited by all authors; Y.C. conducted the HPT and annealing experiments; Y.C. conducted the SEM-BSE characterization; Y.C. conducted the EBSD characterization; Y.C. conducted the tensile tests and data analysis; Y.C. and M.M. conducted the TEM experiments; R.G. and K.I. conducted the FIB and APT experiments, as well as data processing and analysis; Y.C. and B. G. conducted the synchrotron X-ray diffraction experiments and B.G. analyzed the data; T.T. conducted the theoretical calculations. Project administration, supervision, and funding acquisition were performed by N.T.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: John Plummer.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chong, Y., Tsuru, T., Mitsuhara, M. et al. Mechanistic origin of grain size and oxygen interstitial effects on strain-induced α” martensitic transformation in Ti-12Mo alloy. Commun Mater 6, 50 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00777-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00777-4