Abstract

Compared with costly wear-resistant alloys such as bronze and zinc-based alloys, high-zinc aluminium alloys present a promising alternative. Usually, strength and ductility in metals are inversely related, posing the same bottleneck in high-zinc aluminium alloys. Here, we improve the strength and ductility of high-zinc aluminium alloy. Through microalloying, 0.8 wt% Ag and 0.25 wt% Sc were introduced into high-zinc aluminium alloys, resulting in multi-dimensional modification of the brittle η-Zn phases. Ag dissolves in the η-Zn phase, modifying its morphology from a rough ellipse to a fine strip. Sc forms Al3Sc precipitates, which act as nucleation sites for more and finer η-Zn particles. The distribution of η-Zn is regulated in multiple dimensions. Finally, an alloy with a yield strength of 400 MPa and an elongation of 13.8% was obtained, representing increases of 45.5% and 126%, respectively, compared to the base high-zinc aluminium alloy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-zinc aluminium alloy is an aluminium-based wear-resistant material1,2 Due to its excellent friction and wears properties, damping ability and strength, it has extensive application potential in areas such as automotive die castings, wear-resistant materials and aerospace-damped structural components3,4 Currently, high-zinc aluminium alloys serve as excellent substitutes for expensive wear-resistant alloys like brass, bronze, and zinc alloys, and they have been widely utilized in manufacturing wear-resistant materials such as sliding bearings and bushings5,6 High-zinc aluminium alloys have a zinc content ranging from 20% to 45% by weight. The initial development of high-zinc aluminium alloys aims to address the dimensional instability issue in copper-containing Zn–Al alloys, which arises due to the dissolution of ε-CuZn4 during the α + ε → η + T’ reaction7. In general, increased hardness leads to better wear resistance. However, wear-resistant materials frequently encounter severe mechanical impacts, vibrations, and other harsh working conditions. Thus, sufficient ductility is essential to absorb the energy from impacts and deformations, extending the material’s service life. Moreover, a metal matrix with high strength can provide strong support for hard wear-resistant phases, enabling these phases to fully realize their anti-wear potential while also increasing the alloy’s load-bearing capacity and resistance to deformation. As a result, there is a pressing market demand for high ductility, high-strength wear-resistant high-zinc aluminium alloys. Nonetheless, the simultaneous enhancement of both strength and ductility remains a significant challenge in current research.

Essentially, research aimed at enhancing the wear resistance of high-zinc aluminium alloys at present primarily focuses on microalloying. It was found that the addition of Mn, Er and Ni elements can form coarse hardened phases improving the hardness and wear resistance of high-zinc aluminium alloys. Adding Mn to high-zinc aluminium alloys can result in the formation of independent Mn-rich hardening phases (Al6Mn) distributed along grain boundaries, with a few Al6Mn phases running through the grains8. The rare earth element Er is found at the grain boundaries of alloys in the form of large Al3Er(Ti, Cr) intermetallic phases9,10 Research by Temel Savaskan revealed that Ni forms string-like and striated Al3Ni particles distributed among dendrites and interdendritic crystals in Al–40Zn–3Cu alloys11. Moreover, The addition of Ti and Sc leads to an increase in hardness and strength of high-zinc aluminium alloys related to the grain refinement mechanism12,13 Ti forms Al3Ti in high-zinc aluminium alloys, which significantly contributes to grain refinement and dendrite arm spacing14,15 The addition of Sc results in the formation of heterogeneous nucleation particles, including Al3Sc and ω-AlCuSc16. Additionally, nano-sized Al3Sc phases can suppress grain coarsening in high-zinc aluminium alloys following heat treatment or during thermal deformation by exerting a pinning effect at grain boundaries17,18 Xiao et al.19 discovered that the inclusion of Sc could improve the damping capacity and strength of high-zinc Al–Zn–Mg alloys. However, the problem of low elongation in high-zinc aluminium alloys remains unresolved.

High-zinc aluminium alloys can be considered as α-Al and η-Zn double matrix phases. η-Zn phase is recognized to be more brittle than α-Al because zinc has a higher shear modulus than aluminium20,21 The ductility is mainly influenced by the continuous lamellar η-Zn phase formed at grain boundaries during solidification. Therefore, modification to discontinuous eutectic η-Zn phase microstructure and strengthening of η-Zn phase during the casting process is the key to obtaining high ductility and high strength high-zinc aluminium alloys.

In this study, a microalloying approach is proposed by introducing Ag and Sc to modify the morphology, size, and distribution of the η-Zn phase in multiple dimensions. This modification effectively inhibited the continuous precipitation of coarse α + η phases at the grain boundaries, leading to a significant enhancement in the strength and ductility of the high-zinc aluminium alloy. This study marks a substantial breakthrough in the simultaneous enhancement of strength and ductility in high-zinc aluminium alloys, providing an effective pathway for developing high strength, high ductility, and wear-resistant high-zinc aluminium alloys.

Results

Mechanical properties and wear resistance of alloys

Figure 1a illustrates the variation in tensile yield strength (YS), ultimate tensile strength (UTS), elongation (EL), and hardness of the as-cast Al–35Zn–2Cu alloy and Al–35Zn–2Cu alloy with the addition of Ag and/or Sc. The stress-strain curve of the experimental alloy is shown in Fig. 1b. The tensile properties of Al–35Zn–2Cu alloys were enhanced with the addition of either Ag or Sc individually. The addition of Sc individually gives better performance enhancement than the addition of Ag alone, where the YS, UTS and EL of Sc-containing high-zinc aluminium alloys are 355 MPa, 424 MPa and 6.2%, respectively. Notably, the addition of 0.8 wt% Ag to high-zinc aluminium alloys significantly increases the elongation of the alloys. The strength and elongation of the alloy are synergistically enhanced by the combination of Ag and Sc elements. The simultaneous addition of Ag and Sc increased the YS of the base alloy from 275 MPa to 400 MPa, the UTS from 385 MPa to 472 MPa, and the EL from 6.1% to 13.8%. The YS, UTS and EL had growth rates of 45.5%, 22.6% and 126%, respectively. The alloys’ micro-hardness and macro-hardness decrease with the addition of Ag but increase with Sc. The experimental results indicate that Ag and Sc have a synergistic strengthening effect, and Ag can significantly increase the elongation of the alloy.

a The variations in yield strength, tensile strength, hardness, elongation and wear volume of developed alloys. b Stress-strain curves of developed alloys. c The curves of the friction coefficient vs sliding time. d Summary of tensile strength of high-zinc aluminium alloys from the open literature and the present study.

Figure 1c illustrates the change in friction coefficient over time. From Fig. 1c and the wear volume change in Fig. 1a, it’s evident that the addition of Ag and/or Sc reduces the wear volume in the experimental alloys. Additionally, the wear volume decreased by 27% when Ag and Sc were added simultaneously compared to Al–35Zn–2Cu alloy. The friction coefficients increase sharply at the beginning of the wear period and stabilize with the increase of wear time, a phenomenon that can be explained by tribology and lubrication theories. The stability period in the friction coefficients of the alloys containing Ag and Sc is significantly shorter compared to the base alloys. Figure 1d gives the yield strengths and elongations of the high-zinc aluminium alloys reported in published literature2,8,11,13,20,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 and in this study. As compared to various high-zinc aluminium alloys in different literatures, the presently designed alloy has the highest yield strength and high elongation.

Major phase constitutions and microstructure of the as-cast alloys

The SEM images and the EBSD micrographs in Fig. 2 illustrate the microstructure, and grain size of Al–35Zn–2Cu alloy with Ag and/or Sc. Based on refs. 2,11,13,27 the bright silver regions in the SEM images are identified as η-Zn phases, the dark grey regions correspond to α-Al phases, and the circular phases, surrounded by the lamellar α + η phases, are identified as θ-Al2Cu phases. The microstructure of Al–35Zn–2Cu alloy comprises α-Al, θ-Al2Cu phase, and η phase. The brittle α + η phases form in chain-like structures along the grain boundary region. These phases develop during solidification by the reaction of S ↔ α + θ and S ↔ β + η29,30 The primary η-Zn phase is a solid solution of Zn in Al, of hcp crystal structure31,32 The SEM images and corresponding particle size distribution in Fig. 2i–l show that the addition of Ag results in a finer and denser lamellar α + η phases. In Sc-containing high-zinc aluminium alloys, fine dot-flake η phases are observed. The corresponding particle size distribution indicates that Sc can further refine the size of the η phase. The Al3Sc phase is undetectable in the SEM images due to its small size. Upon the simultaneous addition of Ag and Sc, the microstructural evolution showed a composite structure. Comparison of Fig. 2m with Fig. 2p reveals that Sc refines the α-Al. EBSD results indicate that Ag and Sc reduce the grain size from 98 μm to 82 μm. The above results indicate that Ag and Sc have a synergistic effect in refining the η-Zn phase.

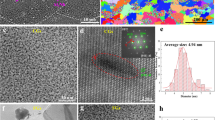

TEM characterization of η-Zn, θ-Al2Cu and Al3Sc phases

The TEM images with EDS mapping are depicted in Fig. 3. Table 1 lists the elemental analysis of the red spots marked in Fig. 3. A step-like segregation of η-Zn is observed. In the literature11 and28, η-Zn typically refers to the hexagonal close-packed (hcp) solid solution of Al in Zn within binary Al–Zn systems. In the Al–35Zn–2Cu alloy, it is specifically denoted as η-Zn (Al, Cu) to indicate the incorporation of aluminium and copper into the Zn solid solution. The inner η-phase is distributed within the α-Al in a circular lamellar structure. Observations of the macroscopic TEM images (Fig. 3a–d) reveal that there are large areas of fine dot-flake η phases in the Sc-containing high-zinc aluminium alloys. The TEM micrographs of the fine dot-flake η-Zn phases at the transition zone between the grain boundary and the matrix (Fig. 3f–i) show that both Ag and Sc are effective in refining the coarse, continuous η-Zn phase. The TEM micrographs of the Ag-containing high-zinc aluminium alloys in Fig. 3g, i indicate that Ag refines the morphology of the η-Zn phase, resulting in a thinner structure. Figure 3h, i demonstrates that Sc significantly reduces the size of the η-Zn phase, leading to an increased density. The EDS mapping in Fig. 3 indicates that Ag forms a solid solution in the η-Zn phase. The solid solution strengthening effect of Ag on the η-Zn phase enhances the strength and plasticity. Observation of the STEM image of the Al3Sc and the related FFT pattern of the Al–35Zn–2Cu–0.8Ag–0.25Sc alloy in Fig. 4 indicates that the Al3Sc phase forms at the interface of the η-Zn and α-Al. Chen et al.33 and Jiang et al.34 noted that Sc is delocalized at the interface of the phase and α-Al in Al-Cu-Sc alloys, where these Sc atoms impede the grow-up of the precipitated phase. Consequently, a small amount of Sc suppressed the coarsening of the η-Zn phase. Furthermore, adding Ag and/or Sc results in the disappearance of the annular η phase surrounding the θ-Al2Cu phase, thereby bringing the θ-Al2Cu phase into direct contact with the discoidal η-Zn and α-Al. This effect is likely to positively impact the tribological properties of the alloys.

TEM characterization of second phases

TEM images and EDS analysis results of the second phases in the Al–35Zn–2Cu–0.8Ag–0.25Sc alloy are depicted in Fig. 5. The EDS analysis results and the fast Fourier transform FFT analysis results in Fig. 5 indicate that Area 1 to Area 3 corresponds to three different second phases, and Area 1 to Area 3 corresponds to the ω-AlCuSc phase, the θ-Al2Cu phase, and the AgZn phase, respectively. The HRTEM results (Fig. 5g) reveal that the lattice spacing parallel to the sidewall is 2.89 Å, corresponding to the (101) plane of the ω-AlCuSc phase, while the lattice spacing parallel to the bottom edge is also 2.89 Å, corresponding to the (01\(\bar{2}\)) plane of the ω-AlCuSc phase. Furthermore, Fig. 5i, k displays the lattice parameters of the θ-Al2Cu and AgZn phases, respectively. These three-second phases exhibit close alignment in irregular shapes. Examination of the elemental distribution in Fig. 5b–f reveals that most Ag atoms reside within the AgZn phase. Based on the aforementioned analytical results, it’s concluded that the majority of Ag atoms are fully dissolved in the η-Zn phase, providing reinforcement, while a portion of them exists as the second phase AgZn. Element Sc exists as the nano-sized Al3Sc phase and the ω-AlCuSc phase in the high-zinc aluminium alloys, playing roles in grain size refinement, matrix reinforcement and modification of η-Zn phase, respectively. The three-second phases, which are closely arranged in an irregular shape, play a key role in the friction and wear properties of the alloy.

a Bright-field image; b–f EDS mapping of (a). g, h HR-TEM image and FFT pattern of Area#1. i, j HR-TEM image and FFT pattern of Area#2. k, l HR-TEM image and FFT pattern of Area#3. m Corresponding intensity distribution for each element of the green line in (a). n–p EDS analysis results for areas 1–3.

SEM characterization of wear surface

Typical SEM patterns of the wear surfaces are depicted in Fig. 6. Smearing is the dominant wear mechanism for all alloys. Abrasion debris, scratches, and delamination are detected on the test alloys’ wear surfaces. Cyclic loading promotes the initiation and expansion of sample surface damage, leading to material delamination and the production of large amounts of wear debris. Wear debris can weaken direct metal-to-metal contact and reduce friction by serving as a solid lubricant35,36 Scratches form due to the movement of abrasion debris across the specimen’s surface under the impact of friction. When wear is severe, delamination and spalling of layers occur as a result of the brittleness of the wear layer. Simultaneously, the frictional heat generated during cyclic loading induces an oxidizing reaction between the debris and atmospheric oxygen. The 3D cross-sectional morphology of the wear surface in Fig. 6 indicates that the wear surface area and depth exhibit a negative correlation with the normal load. With equal normal load, the wear area and depth reflect the experimental alloys’ wear volume. These observations indicate that Ag and Sc have a strengthening effect on the wear properties of the Al–35Zn–2Cu alloy.

In situ tensile SEM testing of the Al–35Zn–2Cu–0.8Ag–0.25Sc alloy

The in situ stress-strain curves and the SEM micrographs are presented in Fig. 7. The strength of the Al–35Zn–2Cu–0.8Ag–0.25Sc alloy under slow strain rate stretching is significantly higher compared to that in conventional tensile experiments. The crack/fracture paths exhibit a zigzag pattern in the macrostructure. The white boxed area and the red boxed area in Fig. 7 represent the crack initiation regions observed during the in situ tensile experiments, respectively, with the white area being the main position leading to the fracture of the alloy. Gas porosity is detected in the middle region of either location, commonly attributed to the entrapment of hydrogen from aluminium during casting37. The position of the gas porosity essentially acts like an artificial gap, leading to a concentration of stress during the tensile process, which ultimately results in cracks sprouting at the gas porosity and subsequent fracture. The cracks visibly expand during stages V to VI of the tensile process. The white boxed area in Fig. 7a–g shows that after the cracks are initiated at the gas porosity, they extend along the η-Zn phase instead of α-Al, which verifies that the η-Zn phase is more brittle compared to α-Al and that the η-Zn phase is the main determinant of the ductility of the alloy. The white box region represents the fracture position of the alloy, attributable to the larger area fraction of the η-Zn phase than the area fraction of the red area. The stress concentration at the gas porosity near the brittle η-Zn phase renders the alloy more susceptible to crack propagation, ultimately resulting in fracture behaviour. The details of the Digital Image Correlation(DIC) tensile experiments are depicted in Fig. 7b–g. DIC tensile tests were conducted to observe the strain distribution between the eutectic phase and the matrix. The strain in the matrix is greater than that in the surrounding η-Zn phase, indicating that the plastic deformation of the η-Zn phase is inferior to that of α-Al, attributable to the higher shear modulus of Zn compared to Al.

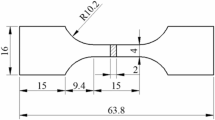

a SEM image of the original position. b–h SEM images of the stage from I to VII. i Tensile sample size and stress-strain curves during the in-suit tensile test. j, k High magnification SEM image and Eulerian Exx-Strain map of VI point. l, m High magnification SEM image and Eulerian Exx-Strain map of VII points.

Figure 7j–m depicts the DIC strain distribution of the alloy before and after fracture. Observations reveal that the cracks extend along the η-Zn phase. After the fracture of Al–35Zn–2Cu alloy, the aluminium matrix undergoes severe plastic deformation at the fracture cross-section, accompanied by a large number of microcracks. The fracture of the η-Zn phase is characterized by quasi-brittle fracture behaviour. In contrast, the aluminium matrix displays ductile fracture behaviour. A large number of larger-size θ-Al2Cu phases are found at the fracture cross-section, indicating that the θ-Al2Cu phases impede the crack extension and cause the crack path deviation.

In summary, boosting the mechanical properties of as-cast high-zinc aluminium alloys requires improving both the strength and ductility of the η-Zn phase. Additionally, enhancing its uniformity promotes a more even distribution of stress during tensile testing. The combination of Ag and Sc elements offers a synergistic dual-phase strengthening effect, leading to significant improvements in the strength and elongation of high-zinc aluminium alloys.

Discussion

The solidification path of the developed alloy, as calculated by Thermo-Calc thermodynamics, is depicted in Fig. 8a–d. Prior to solidification, the microstructure of the Al–35Zn–2Cu alloy comprises α-Al, β-Zn, and θ-Al2Cu phases. The solidus temperature of the alloy stands at 386 °C, while the θ-Al2Cu phase forms at 417 °C. Under room temperature, the as-cast microstructure of the Al–35Zn–2Cu alloy comprises α-Al, η-Zn, and θ-Al2Cu phases. The eventual phase composition is achieved following the production of the η-Zn phase by the eutectic reaction β → α-Al + η-Zn at 273 °C, resulting in the formation of typical laminar α + η phases20,38 The addition of Ag increases the solidus temperature of the alloy from 386 °C in the Al–35Zn–2Cu alloy to 412 °C. Additionally, the equilibrium phase diagram in Fig. 8e–h indicates that Ag elevates the formation temperature of the β-Zn phase and decreases the temperature of the eutectic reaction. Based on the foregoing analysis, it can be summarized that the addition of Ag expands the formation temperature range of β-Zn and promotes its formation, resulting in a finer and denser lamellar α + η phase formed by the eutectic reaction. The solidification of the Al–35Zn–2Cu alloy with Sc alone involves the presence of additional phases, namely Al3Sc and ω-AlCuSc, as indicated in the equilibrium phase diagram. The formation temperature range of the Al3Sc phase is 586–420 °C and 395–188 °C. The temperature range for the ω-AlCuSc phase is 437–394 °C. The simultaneous addition of Ag and Sc results in a higher solidus temperature for the alloy compared to the high-zinc aluminium alloy with Sc alone, with no alteration in phase type. Drawing from the aforementioned solidification process analysis, the schematic representation of the microstructural evolution of the Al–35Zn–2Cu–0.8Ag–0.25Sc alloy’s solidification process is depicted in Fig. 9a, focusing on the discourse surrounding phase evolution during solidification and the formulation of the laminar α + η phase.

The mechanical properties depicted in Fig. 1 show that both Ag and Sc elements significantly enhance the strength of Al–35Zn–2Cu alloys. Ag exhibits a more pronounced effect in enhancing the elongation of the alloy. These findings can be elucidated by considering the microstructural properties attributes, the solid solution strengthening of the η-Zn phase induced by Ag, and the mechanisms of fine grain, dispersion strengthening facilitated and modified the η-Zn phase by the incorporation of Sc. As can be seen in Fig. 3f–i, Ag refines the morphology of the η-Zn phase, resulting in a thinner structure. In addition, Sc significantly reduces the size of the η-Zn phase, leading to an increased density. The above phenomenon can be visualised more intuitively by the schematic diagram in Fig. 9b. As evidenced by the EDS depicted in Table 1, the majority of Ag elements are fully dissolved within the η-Zn. Ag can refine the morphology of the η-Zn phase and form a thinner structure, thus improving the strength of the alloy. Upon adding Sc to the alloy, the formation of the Al3Sc phase between η-Zn and α-Al impedes the coarsening of the η-Zn phase in Al–35Zn–2Cu alloys. The Al3Sc phase exhibits a coherent relationship with α-Al, thereby augmenting the strengthening effect of Orowan and bolstering the strength of the aluminium matrix. Furthermore, the Al3Sc phase can impede the grain coarsening of aluminium alloys. Hence, the enhancement in strength of high-zinc aluminium alloys due to Sc elements can be attributed to dispersion strengthening, fine grain strengthening mechanisms and modified η-Zn phase.

As previously discussed, elemental Ag forms a solid solution within the η-Zn phase rather than α-Al. Ag atoms can occupy numerous vacancies within the η-Zn phase owing to their similar atomic radii to Zn atoms (RZn = 0.1379 nm, RAg = 0.145 nm)39. In this study, the identification of the η-Zn (Al, Cu) phase was primarily based on elemental composition analysis and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observations. However, we acknowledge that the use of more comprehensive structural characterization techniques, such as X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Rietveld refinement analysis, would provide additional confirmation of the crystal structure, lattice constants, and atomic site occupancy of this phase. Although XRD and Rietveld's analysis were not performed in this study, references to research by Gautam et al.40 can offer valuable insights and support for the potential structural characteristics of the η-Zn phase. The solid solution of Ag within the η-Zn phase significantly improves elongation. As Ag and Sc elements reinforce the η-Zn phase and α-Al, respectively, their simultaneous addition creates a synergistic two-phase strengthening effect on high-zinc aluminium alloys. In this study, the Al–35Zn–2Cu alloy containing Ag and Sc demonstrates outstanding mechanical properties with high elongation.

The friction coefficient initially rises quickly, then declines and stabilizes. This phenomenon can be elucidated by the lubrication mechanism41,42,43 In such instances, the wear volume of the alloy is significant, and the thickness of the lubrication layer hinders the separation between the alloy and the slider. As the sliding time progresses, the thickness of the lubrication layer increases, potentially resulting in lubrication from wear debris. The wear interface provides a mixed lubrication, while the contact surface between the metal and the slider increases. Once the lubricant layer is thick enough to separate the alloy and the slider, the wear interface transitions to fluid lubrication, leading to a stable coefficient of friction.

The friction and wear properties of the alloys are enhanced with the addition of Ag and Sc. This phenomenon is attributable to the microstructure, tensile strength and ductility of the alloys. Adding Ag and/or Sc removes the annular η-phase surrounding the θ-Al2Cu phase, enabling direct contact between the hard phase θ-Al2Cu and the slider, thereby improving the tribological properties of high-zinc aluminium alloys. In addition, the Cu-rich θ-Al2Cu phase in the alloy serves as the load-bearing phase, while the Al-rich α-phase facilitates sliding. When Sc and Ag are added, the ω-AlCuSc phase also serves as a load-bearing phase, enhancing the wear performance of the alloy.

Conclusion

High-zinc aluminium alloys exhibit excellent casting, mechanical, and processing properties and are referred to as “magic alloys.” Japanese researchers have predicted that these alloys will become the “fashionable metal materials” of the 21st century, playing an extremely important role. Due to their excellent wear resistance, German experts have termed these alloys “white bronze.” High zinc-aluminium alloys offer superior wear resistance and serve as excellent alternatives to copper and zinc alloys, with a service life of 1–3 times longer than that of copper alloys27. In this study, even with the addition of the noble metals Ag and Sc to the Al–35Zn–2Cu alloy, the cost remains only 40–60% of that of copper alloys and approximately 70% of that of zinc alloy (ZA27) at equal volume. High zinc aluminium alloys exhibit a broad potential market.

Unlike conventional aluminium alloys, high-zinc aluminium alloys can be considered dual-matrix phase alloys (α-Al and η-Zn phases). Enhancing the strength of a single matrix phase should not be considered the primary method for improving properties. A synergistic dual-matrix-phase strengthening mechanism should be explored from a dual-phase strengthening perspective. In this study, Sc and Ag were used to strengthen α-Al and η-Zn, respectively, leading to significant improvements in the alloy’s combined mechanical properties. In the future, composite microalloying will remain a crucial method for developing high-performance high-zinc aluminium alloys.

In summary, a high-zinc aluminium alloy based on Al–35Zn–2Cu was successfully developed through the dual-phase strengthening effects of Ag and Sc on the η-Zn and α-Al phases, respectively. The addition of Ag and Sc modifies the η-Zn phase in multiple dimensions, including morphology, size, and density, while also inhibiting the continuous precipitation of coarse lamellar α + η phases at the grain boundaries. These modifications significantly enhance both the strength and ductility of high-zinc aluminium alloys. Results from uniaxial in situ tensile experiments revealed a non-uniform strain distribution within the η-Zn and α-Al phases, with crack initiation sites closely associated with gas porosity. The Al–35Zn–2Cu–0.8Ag–0.25Sc alloy exhibited a high yield strength of about 400 MPa and an elongation of 13.8% at room temperature. This study represents a major advancement in simultaneously improving the strength and ductility of high-zinc aluminium alloys, addressing the long-standing issue of low elongation in as-cast alloys. Moreover, it offers insights into the development of high-strength, high-ductility, wear-resistant high-zinc aluminium alloys.

Methods

Fabrication of the materials, mechanical tests and characterization

The Al–35Zn–2Cu alloys with 0.8 wt% Ag and/or 0.25 wt% Sc were prepared by using industrial purity aluminium(99.8 wt%), high-purity zinc(99.99 wt%), electrolytic copper (99.99 wt%), pure Ag (99.99 wt%) and Al-2Sc master alloy. In a medium-frequency furnace, the alloys became melted and subsequently heated to 740 °C (±5 °C). The melted alloy was refined by C2Cl6 and then poured into a water-cooled copper mould at 720 °C and a cast slab (300 mm × 150 mm × 35 mm) was obtained. Optical microscope, SEM and TEM were used to study microstructures. Thermo-Calc software was used to compute solidification paths using the TCAL6 database. Vickers hardness was measured using the KB3000BVRZ-SA macro-hardness tester and the FM-700 micro-hardness tester, at a load of 100 gf and a loading duration of 10 s. The alloy hardness results are the average of 7 tests on the same alloy in different positions. Tensile specimens were evaluated according to the GB/T16865-2013 standard at a starting strain rate of 1 mm/min.

Friction and wear tests

The friction and wear tests were conducted at room temperature with a normal load of 5 N and a sliding speed of 0.15 m/s over a 2-h sliding period. The specimens were machined from alloy ingots and smoothed with 2000# sandpaper, with a thickness of 7 mm and a diameter of 42 mm. Owing to the high hardness, exceptional wear resistance, and superior chemical stability, 100 Cr6 steel balls with a diameter of 6 mm were selected as the counter material for the tribological tests conducted in this study. To ensure experimental reliability and repeatability, a fresh specimen and steel ball were utilized for each friction and wear test. During the test, the coefficient of friction was continuously recorded by the transducer. The specimens were ultrasonically cleaned to remove worn metal shavings and weighed at the end of the test to an accuracy of ±0.01 mg. The amount of wear on the test specimen was calculated as the volume loss.

In situ SEM tensile test

In situ SEM tensile tests were performed on the Al–35Zn–2Cu–0.8Ag–0.25Sc alloy. The tensile tests were carried out at a rate of 0.033 mm/s. Backscattered SEM images were captured at 100-second intervals during tensile loading. In addition, the images were subjected to DIC using 2D-DIC MATLAB software (Ncorr v1.2) and two-dimensional strain distributions (Eulerian Exx-Strain) were plotted. For DIC analysis, a subset size of 20 pixels and a subset spacing of 1 pixel were used.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors. Alternatively, the data can be accessed through the data base at the following link https://figshare.com/s/797c1a4795248a03ea83.

References

Durman, M. & Murphy, S. Precipitation of metastable ϵ-phase in a hypereutectic zinc–aluminium alloy containing copper. Acta Metall. Mater. 39, 2235–2242 (1991).

Alemdağ, Y. & Savaşkan, T. Effects of silicon content on the mechanical properties and lubricated wear behaviour of Al–40Zn–3Cu–0–5)Si alloys. Tribol. Lett. 29, 221–227 (2008).

Mazilkin, A. A. et al. Softening of nanostructured Al–Zn and Al–Mg alloys after severe plastic deformation. Acta Mater. 54, 3933–3939 (2006).

Alhamidi, A. et al. Softening by severe plastic deformation and hardening by annealing of aluminum–zinc alloy: significance of elemental and spinodal decompositions. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 610, 17–27 (2014).

Straumal, B. et al. Thermal evolution and grain boundary phase transformations in severely deformed nano grained Al–Zn alloys. Acta Mater. 56, 6123–6131 (2008).

Shin, S.-S., Lim, K.-M. & Park, I.-M. Characteristics and microstructure of newly designed Al–Zn-based alloys for the die-casting process. J. Alloy. Compd. 671, 517–526 (2016).

Shin, S.-S., Lim, K.-M. & Park, I.-M. Effects of high Zn content on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Al–Zn–Cu gravity-cast alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 679, 340–349 (2017).

Krajewski, W. K., Greer, A. L., Buraś, J., Piwowarski, G. & Krajewski, P. K. New developments of high-zinc Al–Zn–Cu–Mn cast alloys. Mater. Today Proc. 10, 306–311 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Effect of multi-element synergistic addition on the microstructure evolution and performance enhancement of laser cladded Al–Mg–Zn–(Mn–Cu–Er–Zr) alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 896, 146256 (2024).

Krajewski, P. K., Greer, A. L. & Krajewski, W. K. Main directions of recent works on Al–Zn-based alloys for foundry engineering. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 28, 3986–3993 (2019).

Savaşkan, T. & Alemdağ, Y. Effect of nickel additions on the mechanical and sliding wear properties of Al–40Zn–3Cu alloy. Wear 268, 565–570 (2010).

Buras, J., Szucki, M., Gracz, B. & Piwowarski, G. The efficiency analysis of grain refinement in high-zinc aluminum alloys with Ti-containing master alloy. Int. J. Cast. Met. Res. 31, 352–359 (2018).

Hekimoğlu, A. P. & Çaliş, M. Effects of titanium addition on structural, mechanical, tribological, and corrosion properties of Al–25Zn–3Cu and Al–25Zn–3Cu–3Si alloys. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 30, 303–317 (2020).

Krajewski, W. K., Greer, A. L., Piwowarski, G. & Krajewski, P. K. Property enhancement by grain refinement of zinc-aluminum foundry alloys. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 117, 271–278, http://iopscience.iop.org/1757-899X/117/1/012004 (2016).

Krajewski, W. K., Greer, A. L. & Krajewski, P. K. Trends in the development of high-aluminum zinc alloys of stable structure and properties. Arch. Metall. Mater. 58, 845–847, http://iopscience.iop.org/1757-899X/117/1/012004 (2013).

Jiang, J.-Y., Jiang, F., Zhang, M.-H. & Yi, K.-K. Study on impact toughness and fracture behaviour of an Al–Mg–Sc alloy. Vacuum 211, 111926 (2023).

Qin, J. et al. The effect of sc addition on microstructure and mechanical properties of as-cast Zr-containing Al–Cu alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 909, 164686 (2022).

Qu, L.-F. et al. Influence of aging treatment on the microstructure, mechanical properties and corrosion behavior of Al–Zn–Mg–Sc–Zr alloy. Vacuum 200, 110995 (2022).

Xiao, J. J., Ge, Z. J., Liu, C. Y., Jiang, H. J. & Cao, K. Stability of damping capacity and mechanical properties of high-Zn-concentration Al–Zn–Mg–Sc alloy. Mater. Charact. 191, 112083 (2022).

Shin, S.-S., Yeom, G.-Y., Kwak, T.-Y. & Park, I.-M. Microstructure and mechanical properties of TiB-containing Al–Zn binary alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 32, 653–659 (2016).

Sivasankaran, S. et al. Microstructural evolutions and enhanced mechanical performance of novel Al–Zn die-casting alloys processed by squeezing and hot extrusion. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 292, 117063 (2021).

Zhang, H.-T. et al. Influence of Ag on microstructure, mechanical properties and tribological properties of as-cast Al–33Zn–2Cu high-zinc aluminum alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 922, 166157 (2022).

Babic, M., Mitrovic, S. & Jeremic, B. The influence of heat treatment on the sliding wear behavior of a ZA-27 alloy. Tribol. Int. 43, 16–21 (2010).

Jiang, H. J. et al. Fabrication of Al–35Zn alloys with excellent damping capacity and mechanical properties. J. Alloy. Compd. 722, 138–144 (2010).

Liu, C. Y. et al. Effects of Sc addition and rolling on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Al–35Zn alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 703, 45–53 (2017).

Ritapure, P. P. & Ritapure, P. P. Study of mechanical properties and erosion wear behaviour of novel Al–25Zn alloy/SiC/Graphite hybrid composites. Mater. Today Proc. 22, 2215–2224 (2020).

Savaskan, T. & Bican, O. Dry sliding friction and wear properties of Al–25Zn–3Cu–(0–5)Si alloys in the as-cast and heat-treated conditions. Tribol. Lett. 40, 327–336 (2010).

Wang, W., Yi, D., Hua, W. & Wang, B. High damping capacity of Al–40Zn alloys with fine grain and eutectoid structures via Yb alloying. J. Alloy. Compd. 870, 159485 (2021).

Zieba, P. & Williams, D. B. Microchemical and microstructural characterization of the early stages of the discontinuous precipitation reaction in Al-22 at.%Zn alloy. Microchim. Acta 145, 275–279, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225723278 (2004).

Zięba, P., Faryna, M. & Chronowski, M. Combined in situ and EBSD studies of discontinuous precipitation in Al-22 at.%Zn alloy. Mater. Charact. 157, 109889 (2019).

Murray, J. L. The Al−Zn (Aluminum–Zinc) system. Bull. Alloy Phase Diagr. 4, 55–73 (1983).

Pola, A., Tocci, M. & Goodwin, F. E. Review of microstructures and properties of zinc alloys. Metals 10, 253 (2020).

Chen, B. A. et al. Effect of interfacial solute segregation on ductile fracture of Al–Cu–Sc alloys. Acta Mater. 61, 1676–1690 (2013).

Jiang, L. et al. Length-scale dependent microalloying effects on precipitation behaviors and mechanical properties of Al–Cu alloys with minor Sc addition. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 637, 139–154 (2015).

Zhang, P., Jia, D., Yang, Z., Yang, B. & Wang, G. Research on the interfacial structure and property improvement of the Cfiber/2Si–B–3C–N ceramic matrix composite. Mater. Charact. 142, 59–67 (2018).

Xu, R.-Z. et al. Comparative study on aromatic thermosetting co-polyester (ATSP) coating and nickel–aluminum bronze on under torsional fretting wear. Wear 454-455, 203290 (2020).

Samuel, A., Zedan, Y., Doty, H., Songmene, V. & Samuel, F.-H. A review study on the main sources of porosity in Al–Si cast alloys. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 1–16 (2021).

Jiang, H. J. et al. Evaluation of microstructure, damping capacity and mechanical properties of Al–35Zn and Al–35Zn–0.5Sc alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 739, 114–121 (2018).

An, F.-P. et al. Influences of the Ag content on microstructures and properties of Zn–3Mg–xAg alloy by spark plasma sintering. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 24, 595–607 (2023).

Gautam, G., Humbeeck, J. V., Perrot, P., Effenberg, G. & Ilyenko, S. Al–Cu–Zn (Aluminium–Copper–Zinc). Light Met. Syst. Part 2 11, 1–24 (2005).

Wu, Z., Sandlöbes, S., Wang, Y., Gibson, J. S. K.-L., & Korte-Kerzel, S. Creep behaviour of eutectic Zn–Al–Cu–Mg alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 724, 80–94 (2018).

Li, X. Z., Hansen, V., Gjonnes, J. & Wallenberg, L. R. Hrem study and structure modeling of the η′ phase, the hardening precipitates in commercial Al–Zn–Mg alloys. Acta Mater. 47, 2651–2659 (1999).

Sreejith, J. & Ilangovan, S. Optimization of wear parameters of binary Al–25Zn and Al–3Cu alloys using design of experiments. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 25, 1465–1472 (2018).

Acknowledgements

Financial support was received from Key R & D project of Shandong Province (project no. 2021SFGC1001 and 2024TSGC0571), Key science and technology project of the Ministry of Emergency Management (project no. 2024EMST101001) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 52204400 and 52304369). We extend our gratitude to the Institute of High-Performance Metal Structure Materials (Soochow University) and the School of Mechanical Engineering (Yanshan University) for their assistance in conducting our experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Haitao Zhang and Hiromi Nagaumi designed and supervised the project. Donghui Yang and Xiaoyu Song carried out the experiments analysed data, and wrote the paper. Zibin Wu, Dongtao Wang and Cheng Guo contributed to collecting the literature and processing the data. Ke Qin and Ping Wang offered the writing guidelines.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Witold Krajewski and Ridvan Gecu for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: John Plummer.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Yang, D., Song, X. et al. Designing wear-resistant high-zinc aluminium alloys with high strength and ductility. Commun Mater 6, 62 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00783-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00783-6