Abstract

Lead halide perovskites are promising materials for optoelectronic applications. Ferroelectricity is often considered as a phenomenon that improves their properties. However, the very existence of ferroelectricity in these materials is still debatable. Here we investigate the dielectric and ferroelectric properties of the single crystals of organic-inorganic hybrid CH3NH3PbX3 (X = I, Br or Cl) and all-inorganic CsPbBr3 perovskites, which are among the most technologically useful materials. We find that MAPbX3 perovskites are incipient ferroelectrics of the order-disorder type and provide experimental evidence. We show that in contrast to SrTiO3 and other known displacive-type incipient ferroelectrics, where the ferroelectric phase is suppressed by low-temperature quantum fluctuations, in the hybrid halide perovskites the order-disorder ferroelectric transition is not attained upon cooling because the first-order octahedral tilting transition to the antiferrodistortive orthorhombic phase occurs at a temperature higher than the expected ferroelectric Curie temperature. The tilting of corner-sharing PbX6 octahedra prevents the ferroelectric ordering of MA dipoles. This insight expands our understanding of the fundamental properties of halide perovskites and suggests strategies for designing ferroelectric organic-inorganic materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the advent of organic-inorganic halide perovskites MAPbX3 (MA = CH3NH3, X = I, Br or Cl) as promising, inexpensive semiconductors for optoelectronic and photovoltaic applications, intense research has been devoted to physical mechanisms that contribute to their superior functional properties1,2,3. Most of these properties are linked to the combination of exceptionally high optical absorption coefficients4 and the unique set of charge carrier parameters, including very large diffusion length with moderate mobility5 and long lifetime6,7. However, the microscopic origin of the extraordinary carrier dynamics still remains a scientific puzzle. In a number of theoretical works, it was attributed to the presence of ferroelectric phase and ferroelectric domain walls, which could influence the band gap and serve as channels for the motion of charge carriers, promoting the separation of photoexcited electron-hole pairs and increasing their diffusion length8,9,10,11.

From the experimental point of view, the presence of ferroelectricity in MAPbX3 is not so evident12,13. The problem is complicated by the fact that using traditional crystallographic methods, it is difficult to unambiguously determine whether the crystal structure is polar or not, and contradictory reports can be found in the literature on this matter14. In addition, these materials possess a relatively high electrical conductivity, inhibiting unambiguous interpretation of polarization-electric field hysteresis loops, traditionally used to confirm the existence of switchable ferroelectric polarization. Most of the evidence for ferroelectricity came from the piezoresponse force microscopy of MAPbI3 around room temperature15,16,17, but some researchers argued that ferroelectric signals might be confused with topographical artifacts, ion migration and chemical/mechanical inhomogeneities11,18.

Here we analyse the literature data relevant to the ferroelectric behavior of MAPbX3 crystals, investigate experimentally their dielectric properties and propose to classify these crystals as incipient ferroelectrics.

Incipient ferroelectrics are a special class of materials in which phases with spontaneous polarization (i.e., ferroelectric phases) are not observed, but a non-polar paraelectric phase whose properties are similar to those observed in the paraelectric phase of normal ferroelectrics still exists down to low temperatures. The transition to the ferroelectric phase (emergence of spontaneous polarization) becomes impossible in incipient ferroelectrics due to the influences of some internal factors, such as quantum fluctuations observed at temperatures close to absolute zero. In the case of MAPbX3 the incipient ferroelectricity originates from the ordering of organic MA molecules, and the ferroelectric phase is suppressed by the antiferrodistortive ordering in the inorganic framework. This finding clarifies the inconsistencies and vague interpretations in the literature and provides an insight into the underlying physical mechanisms related to the optoelectronic performance of hybrid halide perovskites.

Results and discussion

Temperature dependence of the dielectric permittivity (ε) and loss of the studied single crystals are shown in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1, respectively. The arrows indicate the temperatures of transitions between perovskite-type phases belonging to different crystal systems: tetragonal and cubic (TT-C), orthorhombic and cubic (TO-C), orthorhombic and tetragonal (TO-T), and orthorhombic and another orthorhombic (TO-O). The crystal systems of these phases and phase transition temperatures were determined using transmission polarized light microscopy (PLM) in our previous works19,20,21 in all the crystals except MAPbI3, which is not transparent and, therefore, cannot be studied with this technique. The transition temperatures are consistent with the literature data obtained by different measurement methods. Powder X-ray diffraction patterns collected from ground crystals at room temperature and the related Pawley refinement curves are shown in Supplementary Fig. S2. Bragg reflections corresponding only to the perovskite structure are observed, confirming that the prepared samples are single-phase and do not contain any impurity phases.

All the crystals transform upon cooling from a cubic \(({Pm}\bar{3}m)\) to a tetragonal (or orthorhombic in MAPbCl3) phase. Then the second transition to the orthorhombic phase takes place. A third phase transition into another orthorhombic phase is found in MAPbBr3. These phase sequences are not completely consistent with the ones previously determined by x-ray and neutron diffraction methods which are less sensitive to small lattice distortions. Using PLM, we found20,21 that the macroscopic symmetry of the intermediate phase in MAPbBr3 and MAPbCl3 is orthorhombic but not tetragonal, as believed earlier (incommensurate structural modulation was also observed in this phase by x-ray diffraction22,23, which cannot be verified with PLM).

In the crystals containing organic MA cations a distinct permittivity peak is observed at the temperature Tmax, corresponding to the transition from the high-temperature (cubic or tetragonal) to the low-temperature orthorhombic phase. In the all-inorganic counterpart CsPbBr3, no dielectric peaks are found either at TO-T or at any other temperature (Fig. 1b). Thus, the peak can be attributed to the relaxation of MA dipoles. Indeed, investigations with different experimental methods, including dielectric spectroscopy 24,25, calorimetry 26, and infrared spectroscopy 26, indicated that MA dipoles are dynamically disordered (and, therefore, contribute to the dielectric response) in the cubic and tetragonal phases and frozen in the orthorhombic phases.

Besides the electric susceptibility related to the orientation polarization of MA dipoles (\({\chi }_{d}\)), other contributions to the dielectric response evidently exist. Therefore, we may write the total permittivity as \(\varepsilon = {\varepsilon }_{\infty }+{\chi }_{d}+{\chi }_{{LF}}\), where the term \( \varepsilon_{\infty} = {\chi }_{\infty}\) + 1 represents the sum of the electronic polarization (i.e., the displacement of electronic clouds with respect to nuclei), the ionic or phonon polarization (i.e., the displacement of cations with respect to anions) and the polarization caused by the deformation of MA molecules, while the susceptibility \({\chi }_{{LF}}\) arises from the hopping charge carriers and/or space charge polarization. \({\chi }_{{LF}}\) generally increases with increasing temperature or decreasing frequency, but may exhibit maxima in its temperature dependence27. In our experiments the contribution of \({\chi }_{{LF}}\) results in the enhanced ε values measured in the cubic or tetragonal phase at comparatively low frequencies (Fig. 1). The permittivity maximum observed around 380 K in MAPbI3 can also be attributed to this contribution.

The gradual increase of permittivity upon cooling followed by a discontinuous drop at Tmax, which can be seen in Fig. 1, resembles the behavior usually observed at proper first-order ferro- or antiferroelectric phase transitions, which prompted some authors to suggest that the low-temperature state in MAPbX3 crystals is ferroelectric28 or antiferroelectric25,29,30. The phenomenological and microscopic models of ferroelectricity predict31 that in the paraelectric phase the Curie-Weiss (CW) law is valid in the vicinity of the Curie point:

where \({\chi }_{{{\rm{FE}}}}\) is the susceptibility related to the ferroelectric subsystem (orientation polarization in the ferroelectrics of order-disorder type or phonon soft mode polarization in the ferroelectrics of displacive type), C is the Curie-Weiss constant and TCW is the Curie-Weiss temperature which is equal to Tmax for second-order transitions and is slightly lower than Tmax for first-order transitions. The temperature TCW separates a high-temperature region where the paraelectric phase is stable or metastable, and a low-temperature region where the paraelectric phase is unstable, and the ferroelectric spontaneous polarization should appear. However, the published reports concerning the CW law in halide perovskites have been contradictory. In ref. 25 the experimentally measured permittivity was fitted to Eq. (1) considering that ε = \({\chi }_{{FE}}\), and the values of TCW were found to be negative (on the Kelvin scale) for all MAPbX3 compounds. Based on this fact it was concluded that the low-temperature orthorhombic phase is antiferroelectric. In contrast, the authors of ref. 32, who studied MAPbCl3 crystals, found that the dependence of 1/ε on temperature above Tm is not linear, as prescribed by Eq. (1), and that “the orthorhombic phase may not be antiferroelectric but is paraelectric”. To elucidate the reason for these contradictions we note that the expression for the experimentally measured permittivity should include not only \({\chi }_{{FE}}\), but the contributions from other subsystems (hard phonons, hopping charges, etc.) as well. Therefore, for ε measured at high enough frequencies where \({\chi }_{{LF}}\) is negligible, the CW law should be written as33

This equation predicts an infinite value of ε at T = TCW and a decrease of ε upon heating, so that in some temperature range above TCW the relation ε ≫ ε∞ must be valid. In displacive ferroelectrics (such as inorganic perovskite oxides) this range is typically large (tens of Kelvin) because the CW constant is large (C ~ 105 K). The term ε∞ in Eq. (2) can be practically neglected in this case and the CW law reduces to Eq. (1). In order-disorder ferroelectrics C is much smaller (~103 K) and Eq. (2) should be used for a meaningful description of the permittivity in the paraelectric phase.

If the ε(T) peak in MAPbX3 crystals is really due to the ferroelectric order-disorder relaxation of MA dipoles, the orientation susceptibility, \({\chi }_{d},\) should be obviously identified as \({\chi }_{{FE}}\) and Eq. (2) should hold at T > Tmax. The contribution ε∞ is practically temperature independent in MAPbX3, as follows from the results of infrared spectroscopy 34 and microwave dielectric measurements25. Under these conditions the dependence of \(1/\left(\varepsilon -{\varepsilon }_{\infty }\right)\) on temperature should be a straight line in the paraelectric state, and this is really the case for all MAPbX3 crystals as Fig. 2 demonstrates. Note that, since we consider the permittivity at a relatively high frequency of 100 kHz, where the dielectric dispersion is practically absent (see Fig. 1), the contribution of \({\chi }_{{LF}}\) is negligible. The measured dielectric parameters and the best-fit parameters of the CW law are summarized in Supplementary Table S1 and some of them are presented in Fig. 3 as a function of the radius of halide ion (rX). With increasing rX, C increases linearly, while TC decreases. This decrease may be related to the growth of the unit cell size and the distance between MA dipoles which weakens the dipole-dipole electrostatic interactions between the MA dipoles responsible for ferroelectric ordering. The values of C = 103 –104 K are found, which are characteristic of ferroelectric order-disorder transitions. Therefore, as discussed above, Eq. (1), used in some earlier works, cannot adequately describe the temperature dependence of measured permittivity, and the CW parameters obtained by fitting to this equation are misleading.

Temperature dependences of the reciprocal permittivity measured at the frequency of 100 kHz (open symbols) and the reciprocal relaxation time according to ref. 25 (filled symbols) near the peak of permittivity in the crystals of MAPbCl3 (a), MAPbBr3 (b) and MAPbI3 (c). The lines are the least-squares fits to Eqs. (2) and (3).

In MAPbBr3 the permittivity is found to follow the CW law only in the cubic phase, while in the tetragonal phase some deviation occurs. This fact may be attributed to the influence of the complex structure of ferroelastic twin domains which exist in the tetragonal phase and disappear in the cubic phase21. The dielectric behavior in the non-cubic phases is expected to be anisotropic and, therefore, dependent on the domain structure.

From the microscopic point of view, the behavior of proper ferroelectrics is determined by interactions between local dipoles which force the dipoles to be parallel in the ground state. Upon heating the thermal fluctuations destroy this parallel alignment (ferroelectric order), which results in a phase transition and a gradual decrease in the static permittivity in the paraelectric phase. In all proper ferroelectrics, this decrease is described by the same Curie-Weiss law. The dipolar dynamics, however, depends on the type of ferroelectric transition. In the case of displacive transitions, one of the transverse optic lattice vibration (phonon) modes softens as the temperature approaches TC = TCW from above, i.e., the mode frequency diminishes and tends to zero according to the Cochran law ω2 ∝ (T − TC). At order-disorder ferroelectric phase transitions the divergence of the relaxation time of orientation polarization (τ) is observed at TC = TCW35:

Experimental observation of transverse optic modes in the MAPbX3 crystals did not reveal any softening34, so the displacive proper ferroelectricity can be excluded. The values of τ in these crystals are known to be comparatively large, and to determine the temperature dependence of τ, investigations of the dielectric dispersion in the microwave frequency range are needed, which is beyond the operating frequencies of our dielectric spectrometer. Therefore, we use the data of ref. 25 in which the critical slowing down of τ according to Eq. (3) has been reported. These data are reproduced in Fig. 2. It can be seen that in MAPbCl3 and MAPbBr3, TC practically equals TCW, suggesting the existence of dipole-dipole Coulomb interactions among the MA dipoles, which lead them to a ferroelectric ordering at low temperature so that the non-polar paraelectric phase in which the CW is observed should be unstable below TC = TCW. In MAPbI3 TCW is slightly lower than TC, which can be attributed to the influence of the tetragonal domain structure. It is possible that the TCW value determined in the temperature range of cubic phase would be equal to TC (similar to MAPbBr3). Unfortunately, we cannot verify this because in the cubic phase of MAPbI3 the (frequency-dependent) contribution \({\chi }_{{LF}}\) remains significant up to the highest available measurement frequency (see Fig. 1c).

In normal ferroelectrics the paraelectric phase transforms into the ferroelectric phase upon cooling. Any ferroelectric phase must have a polar crystal symmetry. However, it is not easy to determine the crystal symmetry of MAPbX3 using the conventional probing method such as x-ray and neutron diffractions. In early investigations36 the polar Pna21 space group was found for the low-temperature orthorhombic phase, but subsequent papers reported the non-polar Pnma group (see ref. 21 for a review). A conventional way to verify ferroelectricity is to measure the dependence of the polarization (P) on an external electric field (E), which should display the characteristic shape of a ferroelectric hysteresis loop due to the polarization switching process. However, as Fig. 4 shows, in the MAPbX3 crystals the ferroelectric loops are absent. In MAPbCl3 and MAPbBr3 the dependence is practically linear in any field up to the dielectric breakdown. An antiferroelectric phase can also be excluded, since by definition an antiferroelectric phase should transform into a ferroelectric one under an external electric field, resulting in double hysteresis loops. An unambiguous conclusion about the absence of any ferro- or antiferroelectric phase was also made based on the PLM study of the domain structures in MAPbCl320 and MAPbBr321. An external field should decrease the antiferroelectric and increase the ferroelectric transition temperature37 and modify the domain structure, but both the structure and transition temperatures appeared to be unchanged under the field.

In MAPbI3 a hysteretic behavior is observed (Fig. 4c), but the shape of the curves is not characteristic of ferroelectrics. The hysteresis here is due to leakage current and/or other artifacts rather than polarization switching (see refs. 38,39 for detailed explanations). However, we cannot unambiguously exclude ferroelectricity in MAPbI3 based on our data. The ferroelectric Curie point, if it exists, would be above the room temperature, i.e., quite far from the measurement temperature. Under this condition, the coercive field might be larger than the applied field, so that the loop could not open up. We tried to increase the measurement field and the temperature but did not obtain any meaningful data due to the greatly increased leakage current.

To explain why in MAPbCl3 and MAPbBr3, and probably also in MAPbI3, the non-polar crystal structure remains stable when cooled below TC, and the transition to the ferroelectric phase expected based on dielectric measurements is not observed, we suggest that the non-ferroelectric phase transition into the orthorhombic phase occurs first upon cooling, i.e., at Tmax > TC, and the mechanism of this transition is not related to ferroelectricity. This transition is antiferrodistortive and ferroelastic, and it is driven by rotations (tilting) of halide octahedra. The tilting makes ferroelectric ordering of the MA dipoles impossible, i.e., suppresses the ferroelectric phase.

To support this conjecture, let us consider the dependence of transition temperatures in the hybrid MAPbX3 perovskites and their all-inorganic counterparts CsPbX3 perovskites, on the Goldschmidt tolerance factor conventionally defined as:

where rA is the radius of the A site cation (in our case MA or Cs), rB is the radius of the B site cation (Pb) and rX is the radius of the anion (I, Br or I). The dependence is shown in Fig. 5. Shannon radii40 were used for the inorganic ions. The MA ionic radius was estimated to be in the range from 2.03 \({{\text{\AA }}}\)41to 2.7 Å42 in the literature. We used the intermediate value of 2.17 Å suggested in ref. 43, but similar conclusions can be made with other values in that range.

A tolerance factor smaller than unity indicates that in the perovskite ABX3 structure the A site cation is not large enough to completely fill the cuboctahedron formed by the surrounding anions and is underbonded in the aristotype cubic structure. To minimize the gaps between A cations and some anions and optimize thereby the chemical bonding, the BX6 octahedra are cooperatively tilted in the ground state. Such tilting results in a distorted (usually tetragonal, orthorhombic or monoclinic) perovskite structure. Upon heating thermal fluctuations can destroy the ordered octahedral tilting, and the transition from the tilted to the ideal cubic perovskite phase can often be observed. It is reasonable to expect that the lower the tolerance factor, the higher the transition temperature. As can be seen in Fig. 5, the actual phase behavior of halide perovskites corresponds to this expectation: in both the inorganic and hybrid groups the temperature of transition between the cubic and tilted (orthorhombic in MAPbCl3 and tetragonal in other compounds) phases decreases linearly with increasing t. In all compounds the orthorhombic tilted phase of the same space group, Pnma, is observed, and in the hybrid ones the permittivity peak is found just at the transition to the Pnma phase upon cooling. In CsPbX3 the phase transitions are known to be caused by softening and successive condensation of the rotational modes of PbX6 octahedra around one (in the case of T phase) or more (in the case of O and M phases) pseudocubic crystallographic axes44,45,46. As the octahedra in adjacent unit cells rotate in the opposite directions, these are the Brillouin zone boundary modes. The rotation angle plays the role of the order parameter. The ordered phases resulting from mode condensation not at the center of the Brillouin zone are called antiferrodistortive31.

Similarity in the behavior of the inorganic and hybrid halide perovskite groups suggests that in the latter the primary order parameter of phase transitions is also an octahedral tilt. The available experimental results are consistent with this suggestion47,48,49,50. X-ray diffraction investigations showed that the tilt angles decrease upon heating according to the theoretically predicted power law in the low-temperature phases and vanish in the high-temperature phases47,48. On the other hand, the non-cubic phases have recently been shown to be ferroelastic in both inorganic19 and hybrid lead halide perovskites20,21,51. Octahedral tilting changes the distance between neighboring Pb ions, leading to the extension and contraction of the crystal lattice in the directions along and perpendicular to the tilting axis, respectively47. The resulting strain should be considered as a secondary order parameter, arising from the coupling to the primary parameter (tilting). Therefore, the phase transitions in these crystals are improper ferroelastic.

First-principles calculations showed52,53,54,55 that in the perovskite oxides in which two types of unstable vibrational (phonon) modes coexist, namely octahedral tilting and ferroelectric polar soft mode, they usually compete and tend to suppress one another. In MAPbX3 softening of phonon polar modes is not observed34 and ferroelectricity could be related to the order-disorder relaxation mode, but it is natural to think that in this case the tilting would also compete with ferroelectricity. Such a competition was recently confirmed in MAPbI3 based on first-principles density functional theory calculations56. Furthermore, it was found56 that without octahedral tilting this crystal would exhibit on cooling an order-disorder phase transition to the ferroelectric phase due to the ordering of MA molecules.

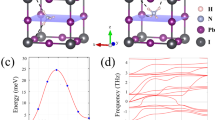

On the other hand, theoretical analysis revealed universal collaborative coupling between octahedral tilting and displacements of A-site cations in the perovskite structure, which can lead to antipolar displacements of the cations at tilting phase transitions57. Such displacements of MA cations are really observed in the orthorhombic Pnma phase of MAPbX3 crystals (Fig. 6a, b).

The structure (with the space group Pnma and tilt system a-b+a-) viewed in a a-b plane and b a–c plane. PbI6 octahedra are highlighted in purple. c Hydrogen bonds (indicated by dotted lines) between three H atoms in the NH3 group and one axial I [IA(1)] atom and two equatorial I [IE(2) and IE(2’)] atoms. Reproduced from ref. 59 with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Note that extrapolations of the transition temperatures versus t dependences observed in inorganic crystals (dashed lines in Fig. 5) predict much lower transition temperatures for hybrid perovskites than those actually observed. This behavior can be explained by significant interactions between the inorganic octahedral framework and MA molecules, which additionally stabilizes the non-polar tilted phases by means of hydrogen bonding. It was reported based on the structural measurements58 and first principles calculations56,59 of MAPbI3 that hydrogen bonds between the H atom of the NH3 group and the framework anions fix the position and orientation of MA molecules in the orthorhombic phase, as shown in Fig. 6c.

Although the structure of MAPbX3 is characterized by an antiparallel arrangement of neighboring MA dipoles with zero resultant polarization and can therefore be classified as antipolar31, it is not antiferroelectric. The modern definition of antiferroelectricity includes not only the crystal structure¸ but also the energetic criteria31,60. The key requirement for an antiferroelectric phase is the presence of a metastable ferroelectric phase with close free energy, which allows the crystal to be transformed into this ferroelectric phase by applying an electric field of practically accessible strength. A characteristic double hysteresis P-E loop should be observed in this case. However, in MAPbX3 no double hysteresis loops are found (Fig. 4) and the experiments have shown20,21 that an electric field does not affect the domain structure. This means that the transition to a ferroelectric phase does not occur at high field and the phase is not antiferroelectric. This fact can be related to the crystal structure, in which the orientations of MA molecules are forced by the shape of A-site cavities in which they are located56, and by hydrogen bonds. A metastable ferroelectric phase, even if it exists, cannot be practically achieved, since the ferroelectric alignment of MA dipoles by the external field would require breaking of hydrogen bonds and a too large distortion of the rigid octahedral network.

It should be further underlined that a priori order-disorder ferroelectric nature of MAPbI3 crystals was derived theoretically in ref. 56. The authors found that anion octahedral rotations drive the system toward an antipolar orthorhombic ground state and characterized the crystal as “missed ferroelectric”. We confirm this behavior experimentally in MAPbI3, as well as other MAPbX3 crystals, and classify it as incipient ferroelectricity.

Note that the dielectric and structural behavior of MAPbX3 crystals are rather similar to those of some inorganic oxides (such as perovskite SrTiO3 or KTaO3), known as incipient ferroelectrics61,62,63. The similarity is sketched in Fig. 7, while the actual experimental data for SrTiO3 crystal are presented in Supplementary Fig. S3. Both in the inorganic incipient ferroelectrics (Fig. 7a) and in the hybrid counterparts (Fig. 7b) the characteristic frequency, ω = 1/τ, and the reciprocal of the susceptibility tend to vanish upon cooling at a critical temperature, TC. The same behavior is characteristic of normal ferroelectrics with the Curie point at TC. But in contrast to normal ferroelectrics, the dependences here start to deviate from the high-temperature trends at some temperature above TC, and the transition to the ferroelectric phase does not occur. There are, however, some differences between all-inorganic and hybrid crystals. The fist difference is in the nature of ferroelectric soft mode: in SrTiO3 and other incipient ferroelectric perovskite oxides it is resonant (softening of the polar lattice vibrations leading to a displacive ferroelectric transition)64, while in MAPbX3 it is relaxation (slowing down of the reorientations of MA dipoles leading to an order-disorder ferroelectric transition). Both modes give rise to formally the same CW law, but different behavior of the vanishing characteristic frequency, as explained in Fig.7. Another difference is that the ferroelectric phase transition in MAPbX3 is prevented by some other (tilting) phase transition which occurs at Ttilt > TC, while there are no other phase transitions around TC in inorganic oxides. The ferroelectric transition therein is prevented by quantum fluctuations of the atomic positions which become important at temperatures close to 0 K (incipient ferroelectrics in this case are called quantum paraelectrics). One more difference (which follows from the previously mentioned ones) is that in MAPbX3 the sharp permittivity maximum is observed. This is because the reorientations of MA dipoles (which determine the permittivity at T > Tm) become frozen at T < Tm due to the tilting phase transition. On the other hand, in quantum paraelectrics the permittivity continuously increases as the temperature decreases, reaching high saturation values. This occurs because the lattice vibrations (which determine the permittivity) remain active at all temperatures, while the quantum effects lead to the deviation from CW law observed at low temperatures. Despite these differences, the basic feature of incipient ferroelectricity, i.e., suppression of ferroelectric instability which would otherwise lead to a ferroelectric phase transition at low temperature, is present in the MAPbX3 perovskites and, therefore, they can be classified as incipient ferroelectrics of order-disorder type.

a Quantum paraelectric oxide perovskites (incipient ferroelectrics of displacive type). b Hybrid MAPbX3 halide perovskites (incipient ferroelectrics of order-disorder type). In the paraelectric phase of quantum paraelectrics the phonon soft mode frequency, ω, obeys the Cochran law, ω2 ∝ (T − TC) and the static electric susceptibility, \({\chi }_{{FE}}=\varepsilon -{\varepsilon }_{\infty }\), obeys the CW law, Eq. (2). In the paraelectric phase of MAPbX3 the susceptibility \({\chi }_{{FE}}\) also obeys the CW law, while the relaxation frequency, ω = 1/τ, follows Eq. (3). The paraelectric behavior is violated at low temperatures, and the crystal remains in a non-ferroelectric state because of (a) the quantum fluctuations or (b) the appearance at the temperature Tm = Ttilt of the phase in which halide octahedra are tilted around all three pseudocubic axes.

The crystal symmetry of different MAPbX3 perovskites observed in the paraelectric phase at T > Tm may be different (cubic or tetragonal). A similar difference can be found among quantum paraelectrics. In particular, the structure of quantum paraelectric KTaO3 remains cubic \({Pm}\bar{3}m\) at all temperatures where the CW law is observed63, similar to MAPbCl3 (Fig. 2a). On the other hand, in SrTiO3 the high-temperature \({Pm}\bar{3}m\) phase transforms at 105 °C (where large quantum fluctuations are absent) to the tetragonal phase due to the rotation of oxygen octahedra around one perovskite axis. The deviation of ε(T) from the CW behavior observed in the cubic phase sets in below the cubic-tetragonal transition temperature65, similar to MAPbBr3 (Fig. 2b).

Recent total X-ray and neutron scattering measurements and the subsequent atomic pair-distribution function (PDF) analysis, as well as theoretical computations, revealed that in MAPbX3 and CsPbX3 the local symmetry of high-temperature phase is lower than the macroscopic cubic symmetry determined with the help of Bragg diffraction techniques or polarized light microscopy. The halide octahedra appear tilted, as in the low-temperature phases, giving rise to dynamic, differently oriented, symmetry-broken domains with the roughly estimated size of 1–3 nm66,67,68,69,70. DFT-based calculations have linked local symmetry breaking in halide perovskites to the double-well shape of the potential energy as a function of octahedral rotation angle, which has a maximum at zero and symmetric minima at certain positive and negative values of the angle67,71,72. Note that such a shape is not unexpected in view of the requirement for chemical bonding optimization discussed above in this section. This requirement remains unchanged at any temperature. It should also be valid for perovskite oxides. Accordingly, similar double-well potential leading to symmetry-breaking fluctuations in paraelectric phase was found in classical incipient ferroelectrics SrTiO3 and CaTiO372.

Further discussion is needed about the transition from the high-temperature phase (usually abbreviated as α phase) to the lower-temperature (β) phase observed in MAPbI3 at 329 K. Conflicting reports have been published concerning the symmetry of these phases. Most X-ray and neutron diffraction investigations36,47,58 suggested the cubic \({Pm}\bar{3}m\) space group for the α phase and the centrosymmetric I4/mcm group for the β phase, which does not allow ferroelectricity. But in some X-ray diffraction studies the polar I4cm structure was determined for the β phase73,74. Moreover, ferroelectric properties of this phase have been postulated in many publications, including recent ones17,75,76,77, despite the scepticism of other researchers24,78,79. Therefore, the debate concerning the nature of β phase in MAPbI3 continues. Our experimental data cannot provide conclusive arguments to this debate. Note, however, that if β phase in MAPbI3 is really ferroelectric, the α→ β transition cannot be a proper ferroelectric phase transition for several reasons. First, all neutron and x-ray diffraction studies, including those in which the polar I4cm space group was found, reported the multiplication of the unit cell volume during the transition from α phase (where the number of formular units per unit cell, Z = 1) to β phase (Z = 4). If the transition is accompanied by cell multiplication (change of the translational symmetry), the polarization cannot be the primary order parameter, because it is not possible to change the translational symmetry by polarizing the structure. Moreover, at the α→ β transition temperature the ε(T) peak theoretically expected at a proper Curie point is absent. In addition, the transverse optic phonon mode was observed in the high-energy, high-resolution X-ray scattering experiments at the temperature of 350 K, i.e., slightly above the α→ β transition, but no softening of this mode expected at proper ferroelectric transitions was found67. Thus, the possibility should be considered that the transition at 329 K in MAPbI3 is an improper ferroelectric one, i.e., the spontaneous polarization is a secondary order parameter, and it is induced in β phase upon cooling due to coupling with a certain non-polar primary order parameter. It is known that dielectric anomaly at improper ferroelectric transitions can be quite small or even absent like in gadolinium molybdate, where the clamped (i.e., measured at constant strain) dielectric permittivity was studied80. MAPbI3 usually exists in the polydomain state51, thus the measurements are performed under clamped conditions; that is why the dielectric anomaly at the improper ferroelectric transition from the α to β phase may be very small. Similar to other phase transitions, the primary order parameter for the α→ β transition in MAPbI3 is the octahedral tilt. This follows from the observation using inelastic X-ray scattering of the soft zone edge acoustic phonon mode corresponding to octahedral tilting67. It was concluded67 that the α→ β transition is driven by condensation of this mode. Furthermore, first-principles phonon calculations show that the soft tilting mode couples strongly and cooperatively to the off-center polar displacements of Pb and MA cations67. Due to this coupling the condensation of non-polar tilting mode at the α→ β transition may lead to the appearance of ferroelectric displacive-type spontaneous polarization (secondary order parameter), i.e., improper ferroelectric phase. This behavior is in line with the results of first-principles calculations, showing that the tilting mode may not only suppress, but also promote, displacive-type ferroelectricity if the tilting angle is sufficiently large55. In MAPbI3 the tolerance factor is smaller than in other considered hybrid perovskites, so the tilting angle is expected to be larger. That is why the improper ferroelectric phase may appear only in MAPbI3.

Another ferroelectric scenario which is compatible with the absence of significant ε(T) anomaly at the α→ β transition is that both α and β phases are ferroelectric. For example, in the classical perovskite ferroelectric Pb(Zr,Ti)O3, no ε(T) peak or jump is observed at the octahedral tilt transition between two ferroelectric phases, R3m and R3c81. Indeed, some authors reported the polar P4mm73,82, or R3m82 symmetry for the α phase of MAPbI3, where all Pb ions are supposed to be shifted in the same direction from the centrosymmetric positions expected in the cubic \({Pm}\bar{3}m\) phase. If this is really the case, the ferroelectric Curie point accompanied by a strong ε(T) peak is expected at some temperature above the α→ β transition. However, we did not observe any sharp dielectric anomalies which could be associated with the Curie point above the α→ β transition (see Fig. 1c). At T ~ 430 K a significant material decomposition begins, so that the Curie point is probably higher than the decomposition temperature and cannot be practically observed. MAPbI3 can be a proper ferroelectric in this case. As MA molecules remain dynamically disordered in α and β phases, the spontaneous polarization could be related to structural instability in the inorganic frame or parallel displacement of time-averaged positions of MA molecules with respect to the inorganic frame.

In the above-considered two possibilities for MAPbI3, namely improper ferroelectric β phase or ferroelectric α and β phases, the ferroelectricity can be due to the shift of the positions of cations with respect to anions, which does not preclude the possibility of order-disorder ferroelectricity related to ordering of MA molecules. Thus, our inference about incipient order-disorder ferroelectric behavior remains valid in MAPbI3 too.

Conclusion

Our results and the analysis of data available in the literature suggest that methylammonium lead halide perovskites can be categorized as incipient ferroelectrics in which order-disorder type ferroelectric phase transition related to the orientational ordering of organic MA molecules and expected at a critical temperature TC is prevented by the first order antiferrodistortive phase transition at the temperature Ttilt = Tmax, which is higher than TC. To the best of our knowledge MAPbX3 perovskites are the first known incipient ferroelectrics of the order-disorder type. All phase transitions in these crystals are driven by the antiferrodistortive soft mode, and the tilt of halide octahedra is the order parameter. All phase transitions are improper ferroelastic. At Tmax the crystal transforms from the high-temperature cubic phase in which halide octahedra are not tilted or the tetragonal phase in which the octahedra are tilted around one pseudocubic axis to the low-temperature orthorhombic phase where the octahedra are tilted around the three pseudocubic axes. The octahedral tilting leads to effective freezing of dipolar dynamics: MA dipoles cannot reorient in cuboctahedral voids due to geometric hindrance and strengthened hydrogen bonds between the H atoms belonging to MA and the halogens in the rigid octahedral framework. As a result, an antipolar ordering of MA dipoles appears below the temperature of permittivity maximum, Tmax. Evidence is provided for the absence of ferro- or antiferroelectric phases in MAPbCl3 and MAPbBr3. For MAPbI3 the question about the existence of ferroelectric phases remains open. Three possibilities can be considered: (i) the reported evidence for the existence of a ferroelectric phase is from measurement artifacts, and all phases are non-ferroelectric; (ii) the α → β transition at 329 K is an improper ferroelectric transition; and (iii) all the phases are ferroelectric.

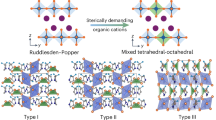

Our conclusion about incipient ferroelectricity in MAPbX3 has important implications. It is known that quantum paraelectrics can often become conventional ferroelectrics due to relatively small modifications (such as epitaxial stress in thin films or doping) that cause the TCW to move to higher temperatures where quantum fluctuations are not active. In MAPbX3 a ferroelectric phase is expected to appear when TCW becomes larger than the temperature of tilting transition into the orthorhombic phase. In view of the relation between TCW and the unit cell size discussed above, an increase in TCW can probably be achieved in solid solutions where inorganic ions are substituted by the ions of smaller size. Such a substitution(s) may also lead to an increase in the tolerance factor and an associated decrease in the tilting transition temperature, which will result in the emergence of a ferroelectric phase.

We expect that order-disorder incipient ferroelectricity will be found in other materials. The criteria under which a material may be classified as order-disorder incipient ferroelectric are the critical slowing down of the relaxation mode according to Eq. (3), the fulfillment of the CW law [Eq. (2)] for the static permittivity with TC = TCW and the absence of a ferroelectric phase below TC. In general, the value of ε∞ in Eq. (2) may depend on temperature. It can be determined from the dielectric spectroscopy data in this case. The cause of the dielectric behavior in paraelectric phase is thought to be ferroelectric order-disorder type instability driven by Coulomb dipole-dipole interactions. Different causes for the suppression of ferroelectric transition can be expected besides the existence of non-ferroelectric transition at some temperature above TC. In particular, it may be a kinetic cause arising as TC approaches 0 K. In this case, the ferroelectric dipole ordering becomes impossible, since the potential energy barriers separating the different directions of the ordering dipoles become much greater than the kinetic energy of the motion of dipoles. Thus, below a certain temperature Tg (> TC), the relaxation time, τ, becomes much longer than practically observable, and local dipoles remain frozen in a disordered state.

Note that some features observed in MAPbX3 perovskites are similar to those characteristic of plastic crystals83,84,85. In plastic crystals, a dynamic orientational disorder of polar molecules or molecular ions is observed, reminiscent of the disorder of MA molecules in the high-temperature phases of MAPbX3. The analogy led the authors of ref. 86 to identify the high temperature MAPbX3 phases as plastic phases. However, the behavior represented by Eqs. 2,3 is generally not characteristic of plastic crystals. The relaxation time follows the Arrhenius or the Vogel-Fulcher law84. The value of \(\varepsilon -{\varepsilon }_{\infty }\) is either nearly constant or increases when moving towards low temperatures, but in general do not follow the CW law84. This suggests that, in contrast to MAPbX3, the ferroelectric interactions between molecular electric dipole moments are not the main factor determining the orientational dipolar dynamics in plastic phase. In addition, plastic crystals possess extraordinarily large mechanical plasticity (hence the name)85, while the MAPbX3 crystals are known to be brittle. Therefore, plastic phase is not an appropriate term for the non-polar phases observed in MAPbX3 at T > Tm. These are paraelectric phases.

Methods

The room temperature crystallization method was used to grow the MAPbX3 (X = I, Br and Cl) and CsPbBr3 single crystals as described in our previous publications19,20,21,87. Cuboid single crystals with as-grown rectangular {100}c faces were selected for measurements (the subscript c denotes pseudocubic perovskite axes). The crystallographic directions of crystal faces were confirmed by specular X-ray diffraction observations19,20,21. Two opposite surfaces of crystal platelet were covered with silver paste or sputtered with gold to form electrodes. No differences in the properties of crystals with gold and silver electrodes were noticed. Gold wires were then attached to both electrodes using colloidal silver paste. The gold wires were connected to the measurement equipment. The dielectric permittivity was measured as a function of temperature and frequency using a Novocontrol Alpha broadband dielectric analyzer equipped with a Quatro Cryosystem for temperature control. The measurements were carried out with field strength of about 5 V mm-1. The data were collected upon heating or cooling the sample at the rate of 0.5 K min-1. The dielectric hysteresis loops were displayed with the help of a Radiant RT-66A ferroelectric testing system connected to a Trek 609E-6 high voltage bipolar amplifier. The measurements were performed at various ac electric fields between 0.5 kV cm-1 and 50 kV cm-1 and frequencies from 1 Hz to 1 kHz. The sample was kept in a silicon oil bath to avoid electric arcing during the field application.

Data availability

Research data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Jena, A. K., Kulkarni, A. & Miyasaka, T. Halide perovskite photovoltaics: background, status, and future prospects. Chem. Rev. 119, 3036–3103 (2019).

Veldhuis, S. A. et al. Perovskite materials for light-emitting diodes and lasers. Adv. Mater. 28, 6804–6834 (2016).

Schmidt-Mende, L. et al. Roadmap on organic–inorganic hybrid perovskite semiconductors and devices. APL Mater. 9, 109202 (2021).

Green, M. A., Ho-Baillie, A. & Snaith, H. J. The emergence of perovskite solar cells. Nat. Photon. 8, 506–514 (2014).

Dong, Q. et al. Electron-hole Diffusion Lengths > 175 μm in Solution-grown CH3NH3PbI3 single crystals. Science 347, 967–969 (2015).

Ma, J. & Wang, L. W. Nanoscale charge localization induced by random orientations of organic molecules in hybrid perovskite CH3NH3PbI3. Nano Lett. 15, 248–253 (2015).

Chen, Y. et al. Extended carrier lifetimes and diffusion in hybrid perovskites revealed by Hall effect and photoconductivity measurements. Nat. Commun. 7, 12253 (2016).

Frost, J. M. et al. Atomistic origins of high-performance in hybrid halide perovskite solar cells. Nano Lett. 14, 2584–2590 (2014).

Liu, S. et al. Ferroelectric domain wall induced band gap reduction and charge separation in organometal halide perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 693–699 (2015).

Rossi et al. On the importance of ferroelectric domains for the performance of perovskite solar cells. Nano Energy 48, 20–26 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Ferroic halide perovskite optoelectronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2102793 (2021).

Ambrosio, F., De Angelis, F. & Goni, A. R. The ferroelectric−ferroelastic debate about metal halide perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13, 7731–7740 (2022).

Zheng, W. et al. Emerging halide perovskite ferroelectrics. Adv. Mater. 35, 2205410 (2023).

Huang, B. et al. Polar or nonpolar? That is not the question for perovskite solar cells. Natl. Sci. Rev. 8, nwab094 (2021).

Kutes, Y. et al. Direct observation of ferroelectric domains in solution-processed CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite thin films. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 3335–3339 (2014).

Vorpahl, S. M. et al. Orientation of ferroelectric domains and disappearance upon heating methylammonium lead triiodide perovskite from tetragonal to cubic phase. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 1, 1534–1539 (2018).

Leonhard, T., Rohm, H., Altermann, F. J., Hoffmann, M. J. & Colsmann, A. Evolution of ferroelectric domains in methylammonium lead iodide and correlation with the performance of perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 21845–21858 (2021).

Liu, Y. T. et al. Reply to: on the ferroelectricity of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskites. Nat. Mater. 18, 1051–1053 (2019).

Bari, M, Bokov, A.A., Leach, G. W. & Ye, Z.-G. Ferroelastic domains and effects of spontaneous strain in lead halide perovskite CsPbBr3. Chem. Mater. 35, 6659–6670 (2023).

Bari, M., Bokov, A. A. & Ye, Z.-G. Ferroelasticity, domain structures and phase symmetries in organic–inorganic hybrid perovskite methylammonium lead chloride. J. Mater. Chem. C. 8, 9625–9631 (2020).

Bari, M., Bokov, A. A. & Ye, Z.-G. Ferroelastic domains and phase transitions in organic–inorganic hybrid perovskite CH3NH3PbBr3. J. Mater. Chem. C. 9, 3096–3107 (2021).

Kawamura, Y. & Mashiyama, H. Modulated Structure in Phase II of CH3NH3PbCl3. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 35, S1437–S1440 (1999).

Guo, Y. et al. Interplay between organic cations and inorganic framework and incommensurability in hybrid lead-halide perovskite CH3NH3PbBr3. Phys. Rev. Mater. 1, 042401 (2017).

Onoda-Yamamuro, N., Matsuo, T. & Suga, H. Dielectric Study of CH3NH3PbX3 (X = Cl, Br, I). J. Phys. Chem. Solids 53, 935–939 (1992).

Anusca, I. et al. Dielectric response: answer to many questions in the methylammonium lead halide solar cell absorbers. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1700600 (2017).

Onoda-Yamamuro, N., Matsuo, T. & Suga, H. Calorimetric and IR spectroscopic studies of phase transitions in Methylammonium Trihalogenoplumbates (II). J. Phys. Chem. Solids 51, 1383–1395 (1990).

Jonscher, A. K. Dielectric Relaxation in Solids (Chelsea Dielectrics Press, 1983).

Gao, Z.-R. et al. Ferroelectricity of the orthorhombic and tetragonal MAPbBr3 single crystal. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 2522–2527 (2019).

Šimėnas, M., Balčiu Nas, S., Mączka, M., Banys, J. R. & Tornau, E. E. Exploring the antipolar nature of methylammonium lead halides: a monte carlo and pyrocurrent study. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 4906–4911 (2017).

Sewvandi, G. A. et al. Antiferroelectric-to-Ferroelectric Switching in CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite and its potential role in effective charge separation in perovskite solar cells. Phys. Rev. Appl. 6, 024007 (2016).

Lines, M. E. & Glass, A. M. Principles and Applications of Ferroelectrics and Related Materials (Clarendon Press, 1977).

Dutt, S., Rambadey, O. V., Sagdeo, P. R. & Sagdeo, A. Absence of presumed ferroelectricity in methylammonium lead chloride single crystals representing organic-inorganic hybrid perovskites. Mater. Chem. Phys. 295, 127169 (2023).

Mitsui, T. Tatsuzaki, I. & Nakamura, E. An Introduction to the Physics of Ferroelectrics (Gordon & Breach, 1976).

Zelezny, V. et al. Infrared and terahertz studies of phase transitions in the CH3NH3PbBr3 perovskite. Phys. Rev. B 107, 17413 (2023).

Blinc, R. & Zeks, B. Soft Modes in Ferroelectrics and Antiferroelectrics (North-Holland Pub. Co., 1974).

Poglitsch, A. W. & Weber, D. Dynamic disorder in methylammonium trihalogenoplumbates (II) observed by millimeter-wave spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 87, 6373 (1987).

Devonshire, A. F. Theory of ferroelectrics. Adv. Phys. 3, 85–130 (1954).

Scott, J. F. Ferroelectrics go bananas. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 20, 021001 (2008).

Tylczyński, Z. A. A collection of 505 papers on false or unconfirmed ferroelectric properties in single crystals, ceramics and polymers. Front. Phys. 14, 63301 (2019).

Shennon, R. D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Cryst. A32, 751–767 (1976).

Filip, M. R., Eperon, G. E., Snaith, H. J. & Giustino, F. Steric engineering of metal-halide perovskites with tunable optical band gaps. Nat. Commun. 5, 5757 (2014).

Amat, A. et al. Cation-induced band-gap tuning in organohalide perovskites: interplay of spin−orbit coupling and octahedra tilting. Nano Lett. 14, 3608–3616 (2014).

Kieslich, G., Sun, S. & Cheetham, A. K. Solid-state principles applied to organic–inorganic perovskites: new tricks for an old dog. Chem. Sci. 5, 4712–4715 (2014).

Fujii, Y., Hoshino, S., Yarnada, Y. & Shirane, G. Neutron-scattering study on phase transitions of CsPbCl3. Phys. Rev. B 9, 4549–4559 (1974).

Yang, R. X., Skelton, J. M., Lora da Silva, E., Frost, J. M. & Walsh, A. Spontaneous octahedral tilting in the cubic inorganic cesium halide perovskites CsSnX3 and CsPbX3 (X = F, Cl, Br, I). J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 4720–4726 (2017).

Chen, L., Xu, B., Yang, Y. & Bellaiche, L. Macroscopic and microscopic structures of cesium lead iodide perovskite from atomistic simulations. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1909496 (2020).

Kawamura, Y., Mashiyama, H. & Hasebe, K. Structural study on cubic–tetragonal transition of CH3NH3PbI3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 71, 1694–1697 (2002).

Mashiyama, H. Y., Kawamura, Y., Magome, E. & Kubota, Y. Displacive character of the cubic-tetragonal transition in CH3NH3PbX3. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 42, S1026–S1029 (2003).

Chi, L. et al. The ordered phase of methylammonium lead chloride CH3ND3PbCl3. J. Solid State Chem. 178, 1376–1385 (2005).

Swainson, P. et al. From soft harmonic phonons to fast relaxational dynamics in CH3NH3PbBr3. Phys. Rev. B 92, 100303 (R) (2015).

Strelcov, E. et al. CH3NH3PbI3 perovskites: ferroelasticity revealed. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602165 (2017).

Zhong, W. & Vanderbilt, D. Competing structural instabilities in cubic perovskits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 2587–2590 (1995).

Bhattacharjee, S., Bousquet, E. & Ghosez, P. Engineering multiferroism in CaMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 117602 (2009).

Ederer, C., Harris, T. & Kovacik, R. Mechanism of ferroelectric instabilities in non-d0 perovskites: LaCrO3 versus CaMnO3. Phys. Rev. B 83, 054110 (2011).

Gu, T. et al. Cooperative couplings between octahedral rotations and ferroelectricity in perovskites and related materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 197602 (2018).

Tong, W.-Y., Zhao, J.-Z. & Ghosez, P. Missed ferroelectricity in methylammonium lead iodide. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 165 (2022).

Bellaiche, L. & Iniguez, J. Universal collaborative couplings between oxygen-octahedral rotations and antiferroelectric distortions in perovskites. Phys. Rev. B 88, 014104 (2013).

Weller, M. T., Weber, O. J., Henry, P. F., Di Pumpo, A. M. & Hansen, T. C. Complete structure and cation orientation in the perovskite photovoltaic methylammonium Lead Iodide between 100 and 352 K. Chem. Commun. 51, 4180–4183 (2015).

Lee, J. H., Bristowe, N. C., Bristowe, P. D. & Cheetham, A. K. Role of Hydrogen-Bonding and its Interplay with Octahedral Tilting in CH3NH3PbI3. Chem. Commun. 51, 6434–6437 (2015).

Rabe, K. M. Antiferroelectricity in Oxides: a Reexamination. in Functional Metal Oxides: New Science and Novel Applications (eds. by Ogale, S. B., Venkatesan, T. V. & Blamire. M. G.) 221-244 (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co, 2013).

Müller, K. A. & Burkard, H. SrTiO3: an intrinsic quantum paraelectric below 4 K. Phys. Rev. B 19, 3593–3602 (1979).

Lemanov, V. V. Phase transitions and dielectric relaxation in incipient ferroelectrics with the Perovskite Structure. Ferroelectrics 346, 97–109 (2007).

Samara, G. A. Ferroelectricity revisited–advances in materials and physics. Solid State Phys. 56 239–458 (2001).

Barker, A. S. & Tinkham, M. Far-infrared ferroelectric vibration mode in SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. 125, 1517–1530 (1962).

Dec, J., Kleemann, W. & Westwanski, B. Scaling behaviour of strontium titanate. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 11, L379–L384 (1999).

Comin, R. et al. Lattice dynamics and the nature of structural transitions in organolead halide perovskites. Phys. Rev. B 94, 094301 (2016).

Beecher, A. N. et al. Direct observation of dynamic symmetry breaking above room temperature in methylammonium lead iodide perovskite. ACS Energy Lett. 1, 880–887 (2016).

Bernasconi, A. & Malavasi, L. Direct evidence of permanent octahedra distortion in MAPbBr3 hybrid Perovskite. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 863–868 (2016).

Bertolotti, F. et al. Coherent nanotwins and dynamic disorder in cesium lead halide Perovskite Nanocrystals. ACS Nano 11, 3819–3831 (2017).

Weadock, N. J. et al. The nature of dynamic local order in CH3NH3PbI3 and CH3NH3PbBr3. Joule 7, 1051–1066 (2023).

Yang, R. X., Skelton, J. M., da Silva, E. L., Frost, J. M. & Walsh, A. Assessment of dynamic structural instabilities across 24 cubic inorganic halide perovskites. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 024703 (2020).

Zhao, X.-G., Wang, Z., Malyi, O. I. & Zunger, A. A. Effect of static local distortions vs. dynamic motions on the stability and band gaps of cubic oxide and halide perovskites. Mater. Today 49, 107–122 (2021).

Stoumpos, C. C., Malliakas, C. D. & Kanatzidis, M. G. Semiconducting Tin and Lead Iodide Perovskites with organic cations: phase transitions, high mobilities, and near-infrared photoluminescent properties. Inorg. Chem. 52, 9019–9038 (2013).

Dang, Y. et al. Bulk crystal growth of hybrid perovskite material CH3NH3PbI3. CrystEngComm 17, 665–670 (2015).

Rakita, Y. Tetragonal CH3NH3PbI3 is ferroelectric. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, E5504 (2017).

Breternitz, J., Lehmann, F., Barnett, S. A., Nowell, H. & Schorr, S. Role of the Iodide–Methylammonium Interaction in the Ferroelectricity of CH3NH3PbI3. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 424–428 (2020).

Zhao, X. et al. Macroscopic piezoelectricity of an MAPbI3 semiconductor and its associated multifunctional device. Nano Energy 118, 108980 (2023).

Sharada, G. et al. Is CH3NH3PbI3 Polar? J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 2412–2419 (2016).

Frohna, K. et al. T. Inversion symmetry and bulk Rashba effect in methylammonium lead iodide perovskite single crystals. Nat. Commun. 9, 1829 (2018).

Cross, L. E., Fouskova, A. & Cummins, S. E. Gadolinium Molybdate, a new type of ferroelectric crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 21, 812–813 (1968).

Eitel, R. & Randall, C. A. Octahedral tilt-suppression of ferroelectric domain wall dynamics and the associated piezoelectric activity in Pb(Zr,Ti)O3. Phys. Rev. B 75, 094106 (2007).

Baikie, T. et al. A combined single crystal neutron/X-ray diffraction and solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance study of the hybrid perovskites CH3NH3PbX3 (X = I, Br and Cl). J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 9298–9307 (2015).

Lynden-Bell, R. M. & Michel, K. H. Translation-rotation coupling, phase transitions, and elastic phenomena in orientationally disordered crystals. Rev. Mod. Phys. 66, 721–762 (1994).

Brand, R., Lunkenheimer, P. & Loidl, A. Relaxation dynamics in plastic crystals. J. Chem. Phys. 116, 10386–10401 (2002).

Das, S., Mondal, A. & Reddy, C. M. Harnessing molecular rotations in plastic crystals: a holistic view for crystal engineering of adaptive soft materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 8878–8896 (2020).

Even, J., Carignano, M. & Katan, C. Molecular disorder and translation/rotation coupling in the plastic crystal phase of hybrid perovskites. Nanoscale 8, 6222–6236 (2016).

Bari, M. et al. Room-temperature synthesis, growth mechanisms and opto-electronic properties of organic– inorganic halide perovskite CH3NH3PbX3 (X = I, Br, and Cl) single crystals. CrystEngComm 23, 3326–3339 (2021).

Marronnier, A. et al. Anharmonicity and disorder in the black phases of cesium lead iodide used for stable inorganic perovskite solar cells. ACS Nano 12, 3477–3486 (2018).

Hirotsu, S., Suzuki, T. & Sawada, A. Urtrasonoc velocity around the successive phase transitions points of CsPbBr3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 43, 575–582 (1977).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC, Discovery Grant No. RGPIN-2023-04416, and Alliance Grant No. ALLRP-580562-22) and the U.S. Office of Naval Research (ONR, Grant No. N00014-21-1-2085).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.B. designed experiments and wrote the manuscript with the help of M.B. M.B. designed and performed the experiments. Z.-G.Y. initiated the project, obtained funding, and coordinated the research work as the PI. All the authors revised the manuscript and have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Wei Zhang and Jet-Sing Lee. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bokov, A.A., Bari, M. & Ye, ZG. Incipient ferroelectricity in methylammonium lead halide perovskites. Commun Mater 6, 80 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00791-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00791-6