Abstract

Recent studies have increasingly applied natural language processing to automatically extract experimental information from battery materials literature. Despite the complexity of battery manufacturing—from material synthesis to cell assembly—no comprehensive study has systematically organized this information. Here we present a language modeling-based protocol for extracting complete battery recipes from scientific papers. Using machine learning-based filtering and topic modeling, we identified 2174 relevant papers and extracted over 5800 paragraphs describing synthesis and assembly procedures. Deep learning-based named entity recognition models were trained to extract 30 entities with F1-scores of 88.18% and 94.61%. We also evaluated large language models, including GPT-4, using few-shot learning and fine-tuning. These results enabled the structured construction of 165 end-to-end recipes and identification of trends such as precursor–method associations. The resulting knowledge base supports flexible recipe retrieval and provides a scalable framework for organizing protocols across large volumes of publications, thereby accelerating literature review and data-driven battery design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In materials science, there has been a notable surge in interest towards data-driven materials informatics1,2. To underpin this paradigm shift, concerted efforts have been made to obtain ample high-quality datasets. Several open databases related to materials information exist, including the Materials Project3, Open Quantum Materials Database4, and Novel Materials Discovery5; however, these databases mainly consist of the results of computational studies. This insufficiency of actual experimental data can be resolved by applying natural language processing (NLP) to scientific literature6,7. Research articles are meticulously curated and peer-reviewed, ensuring both high quality and large quantity, from which NLP techniques can automatically extract specific information of interest8. In this context, text-mining studies in materials science have increased in recent years, particularly in the fields of catalysts9,10,11, metal-organic frameworks12,13, and high entropy alloys14.

For battery materials, various NLP studies have focused on extracting information on battery materials or performance, and synthesis recipes from the literature to construct databases15,16,17,18. Specifically, there has been a wealth of research dedicated to extracting material and property information on battery cell assembly processes using NLP techniques such as named entity recognition (NER). For example, some pioneers suggested various literature mining protocols to extract cell-composition information, such as anode, cathode, or electrolyte materials, and cell-performance information such as capacity or voltage using chemistry-aware NLP techniques15,16,17. Similarly, efforts have been made to retrieve specific information such as the electrochemical characterization and cycling conditions of lithium-ion battery cells using transformer-based NER models, thereby providing a large-scale text-mined dataset with 28 entities18. Recently, Gou et al.19 suggested a document-level NLP pipeline for literature related to layered cathode materials for sodium-ion batteries. The model simultaneously extracts chemical entities, electrochemical properties, and synthesis parameters. Building on recent progress in NLP-driven materials extraction, the emergence of large language models (LLMs), such as GPT-3 and GPT-4, has significantly advanced the capabilities of scientific text analysis. These models enable zero-shot, few-shot, and fine-tuned learning paradigms, providing flexible and scalable solutions for extracting structured information from unstructured text20,21,22. In materials science and chemistry, LLM-based approaches have demonstrated promising results in extracting synthesis steps, predicting experimental outcomes, and assisting literature analysis23,24,25,26,27,28,29. Notably, recent studies have highlighted the potential of LLMs to revolutionize battery research by transforming unstructured text into structured insights and even guiding materials discovery through generative reasoning30.

Despite their contributions, there is still room for improvement in defining the subject of battery recipes, as prior works employed limited information such as ‘name of battery material’ or ‘synthesis recipe of battery material’, which we suggest is not sufficient to represent or directly connect to battery performance data. For example, even if the same electrode material is used, differences in the cell-assembly process, e.g., using different cell types20,21,22, electrode slurry recipes31,32,33,34,35,36, separators37,38,39, binders40,41, or electrolyte composition42,43,44, greatly affect the battery performance. Therefore, to avoid ambiguity in defining battery performance, it is necessary to collect end-to-end battery recipes, where all the information from the synthesis of the electrode materials to cell assembly is gathered, before analyzing the battery performance. Notably, there has been no attempt to handle the overall process from battery materials synthesis to battery cell assembly.

In this work, we propose a language modeling-based protocol, Text-to-Battery Recipe (T2BR), for the automatic extraction of end-to-end battery material recipes from the scientific literature. As a proof of concept, we select LiFePO4 cathode material, one of the most extensively studied materials in the battery field45, for our case study. First, we report machine learning (ML)-based text classification models to systematically gather papers on battery recipes. Next, we apply topic modeling such as Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA)46, to identify paragraphs related to cathode materials synthesis and battery cell assembly. Third, NER models based on pre-trained language models are developed. The best-performing models exhibit F1 scores of 88.18% and 94.61% in recognizing entities related to cathode materials synthesis and cell assembly, respectively. Our information extraction reveals trends in the usage of materials, conditions, and synthesis methods in battery experimental studies. Finally, we generate 2840 and 2511 sequences for two tasks based on NER results and synthesis actions47, thereby reporting 165 end-to-end battery material recipes. Based on the recipe database, it is expected that an interactive battery recipes information-retrieval system, which provides end-to-end recipes based on user inputs such as partial precursors or synthesis methods, can be developed. To the best of our knowledge, this work is the first to provide an automatic extraction of end-to-end battery material recipes from scientific literature.

Results and discussion

Workflow of the proposed protocol

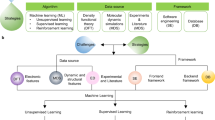

Figure 1 presents the comprehensive process of our T2BR protocol, which is divided into five distinct steps: (1) paper collection, (2) paper selection, (3) paragraph preparation, (4) battery recipe information extraction, and (5) battery recipe generation. In the first step, 5885 papers were collected by using a query consisting of several relevant keywords, such as LiFePO4, on an academic search engine. Next, we developed a text-classification model to filter out irrelevant papers based on abstract information, leaving 2174 valid papers. In the third step, we implemented topic modeling at the paragraph level, thereby identifying 2876 and 2958 paragraphs related to cathode material synthesis and cell assembly topics, respectively. Next, we developed NER models to extract a total of 30 entities, such as the precursors, active materials, binder, atmosphere, or temperature, then revealing the usage trends using the extracted entities. Finally, we generated 2840 and 2511 sequences representing the process of cathode materials synthesis and cell assembly, respectively, which were used to construct 165 end-to-end battery recipes. The results for each step are described below.

The following issues are considered in this workflow: (1) All the textual information of scientific literature, in addition to metadata such as paper type, publication date, or journals, is collected to filter high-quality papers. (2) Papers of interest are selected based on the abstract of papers using the ML model trained on a labeled dataset. (3) Paragraph preparation is performed by an unsupervised ML model, which refers to paragraph-level text information. (4) NER models are developed to extract scientific information on materials, conditions, or synthesis actions, where we prepare the annotation dataset for training these models. (5) Based on the information extraction results, recipe sequences are generated and stored in our database.

Collection and selection of battery recipe papers

The first step of our protocol involves collecting comprehensive scientific literature on battery materials recipes. We used the ScienceDirect RESTful API, employing a search query such as (“LiFePO4” OR “lithium iron phosphate” OR “lithium ferrophosphate” OR “olivine”) AND (“battery”); Our focus was on selecting documents categorized as research articles, therefore, other document types such as review articles, encyclopedias, short communications, and book chapters were excluded. This search yielded a total of 5885 papers published up to May 2022. For each selected paper, we gathered bibliographic information, including the DOI, as well as textual information such as the title and abstract.

The results of such an information-retrieval process depend on the inclusion of specific keywords. Consequently, even if the above-mentioned keywords are mentioned in a paper, they might not necessarily pertain to battery material synthesis. To address this issue, we sampled 1000 papers and evaluated their abstracts to determine their relevance to battery recipes. Using this dataset (true: 281, false: 719), we conducted a binary classification using term frequency inverse document frequency (TF-IDF)-based ML models. All text classification models underwent evaluation using fivefold cross-validation, with the optimized eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) model exhibiting the highest F1 score of 85.19% among five different classification models. Detailed optimization procedures for each model are provided in the Methods section. We applied the best-performing model to the remaining 4885 papers, thereby identifying 1893 relevant papers in addition to 281 true papers.

Preparation of battery recipe paragraphs

Next, we extended our analysis to the paragraphs of valid papers (N = 2174). After excluding paragraphs too short to identify the contents (less than 200 characters), 46,602 paragraphs remained for analysis. This threshold was established to exclude content that lacked sufficient detail to describe complex synthesis processes or experimental results. To validate this criterion, we manually reviewed a random sample of excluded paragraphs and confirmed that most contained incomplete or generic information, such as section titles or brief figure/table descriptions. For instance, brief statements such as ‘Fig. 3. The first cycle charge-discharge curves of LiFePO4 powders synthesized at 220 °C for 10 hours’ lack sufficient detail to describe the synthesis process comprehensively. We applied unsupervised learning-based topic modeling methods, specifically LDA, BERTopic, and BERTopic combined with K-means clustering, to identify common topics within the dataset. We compared the models using two criteria—the number of topics generated and the coherence score—as summarized in Supplementary Table 1. BERTopic initially generated 253 fine-grained topics with a high coherence score of 64.05, indicating well-organized internal structures. However, the large number of topics complicated the interpretation and categorization of specific themes. To address this, we applied K-means clustering to BERTopic, which reduced the number of topics to 24 despite initially setting the cluster count to 25. This discrepancy likely resulted from data distribution characteristics, where highly similar topics were merged, or one cluster remained empty due to insufficient data points.

In contrast, LDA generated 25 distinct topics with a coherence score of 59.63, which, though slightly lower than that of BERTopic, was more manageable for identifying key themes within battery-related research. The simpler and distinct structure of LDA topics made it particularly beneficial for our analysis, allowing us to pinpoint paragraphs specifically related to battery recipes without significant ambiguity. As a result, we adopted LDA for our final analysis due to its ability to produce a reasonable number of distinct topics with acceptable coherence. Using LDA, we identified 25 topics and analyzed their most frequent keywords to determine their main content, revealing two topics closely related to battery recipes: one on the synthesis of cathode materials and the other on battery cell assembly (Fig. 2b, c), while the node distribution on the 2D map (Fig. 2a) highlights thematic relationships, where closely positioned nodes indicate overlapping topics and distant nodes suggest independent themes. Notably, topics 17 and 14 exhibit a close relationship, sharing overlapping keywords such as “capacity,” “cycling,” and “performance,” which reflect their thematic focus on various aspects of battery performance, including discharge rates and electrochemical behavior. In contrast, topics 21 and 17 are positioned far apart due to minimal keyword overlap. Topic 21 focuses on chemical and structural analyses, such as Raman spectroscopy, while topic 17 emphasizes battery cycling and discharge characteristics. This distinct positioning underscores the divergence between structural characterization and electrochemical performance analysis.

a Two-dimensional map of topics, which was obtained by applying principal component analysis to a topic-keyword distribution matrix. Here, the node size is proportional to the ratio of each topic within the entire corpus. b, c Frequent keywords of ‘cathode materials synthesis’ and ‘cell assembly’ topics.

The topic of cathode material synthesis encompassed 2876 paragraphs, characterized by frequent key terms such as ‘solution’, ‘h’, ‘temperature’, ‘mixture’, and ‘powder’. The topic of battery cell assembly comprised 2958 paragraphs, with frequent keywords including ‘cell’, ‘electrode’, ‘electrochemical’, ‘cathode’, ‘electrolyte’, and ‘foil’. Thus, by employing unsupervised learning techniques such as statistical topic distribution inference, we were able to efficiently identify the main content of paragraphs related to battery recipes and accurately determine the locations of these recipe-related paragraphs within the research papers. The primary keywords for the remaining 23 topics, judged to be unrelated to battery recipes, are delineated in Supplementary Table 2.

Information extraction of battery recipes

Next, we developed two NER models to extract specific information about cathode materials synthesis and battery cell assembly. To achieve this, we created an annotated dataset where the start and end indices of each category were marked with special tags. Our deep learning-based NER models primarily consisted of bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT)48 and conditional random field (CRF)49 layers, as illustrated in Fig. 3. We used existing pre-trained BERT models for the BERT component, which was pre-trained on domain-specific and large-scale corpora. Then the models were fine-tuned on our annotated datasets to adapt the model to the specific context of battery recipes. For cathode materials synthesis, we identified 15 categories: precursors, temperature, target materials, time, amount, ratio, atmosphere, company, method, solvent, wash solvent, speed, solution, coating, and pH. We manually annotated 100 paragraphs, carefully reading and marking the relevant entities. For cell assembly, we defined 15 categories: amount, cathode solvent, active materials, binder, conductive agent, anode, solvent, salt, current collector, temperature, time, company, size, separator, and pressure. The descriptions and statistics of these annotations are provided in Supplementary Tables 3–4. We annotated 200 paragraphs to develop the NER models for this task. Specific details on the model training and its mechanisms are provided in the Methods section.

The original text of the paper concerning battery recipes undergoes tokenization by the tokenizer, followed by the NER model, which predicts the category for each token. The NER model comprises a BERT layer for capturing the contextual meaning of each token, alongside a SoftMax function and a CRF layer designed to predict the sequence with high probability.

In simple terms, as illustrated in the example in Fig. 3, the first token of the input text, ‘LiFePO4’, is tagged as ‘S-AM’ for a single-word entity of the ‘Active Materials’ category. The NER model is trained to accurately predict the tag for each word by considering the surrounding context, such as the meaning and the predicted tags of neighboring tokens. This mechanism enables the model to determine the start and end positions of words corresponding to each category, thereby facilitating the extraction of relevant information. We employed the BERT-CRF model for the NER task, utilizing various domain-specific BERT models to investigate the impact of their context-understanding abilities. The efficacy of NER is influenced by both the specific characteristics of the subject under analysis (cathode material synthesis vs. battery cell assembly) and the domain specificity of the language model’s training corpus. To investigate this effect, we evaluated four pre-trained language models—BERT48, SciBERT50, BatteryBERT15, and MatBERT51—by comparing their NER performance in terms of F1 score, as summarized in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6. In addition to testing BERT-based NER models, we evaluated the performance of ChemDataExtractor, a widely used rule-based tool for material information extraction, as a baseline. Supplementary Table 7 summarizes the performance of ChemDataExtractor with and without boundary relaxation for cathode synthesis and cell assembly tasks. ChemDataExtractor achieved F1 scores of 50.09 for cathode synthesis and 40.75 for cell assembly. When boundary relaxation was applied (allowing partial matches to count as correct), the performance improved to 68.14 and 56.40, respectively. These scores demonstrate that while boundary relaxation enhances the performance of ChemDataExtractor, it remains limited in effectively handling complex or ambiguous entities in battery-related research texts.

To ensure a fair comparison, the performance evaluation of ChemDataExtractor was restricted to categories that it is capable of recognizing. For cathode materials synthesis, the evaluation included categories such as “PRECURSOR,” “TARGET_MATERIAL,” and “SOLVENT,” while for battery cell assembly, categories like “ACTIVE_MATERIAL,” “ANODE,” and “SEPARATOR” were considered. This filtering approach aligns the evaluation with ChemDataExtractor’s inherent design limitations, providing a focused analysis of its capabilities within its predefined scope.

Despite the improvements achieved through boundary relaxation, ChemDataExtractor’s inability to adapt to a broader range of annotation categories underscores the advantage of Transformer-based models, which demonstrate greater flexibility and contextual understanding across diverse and complex domains. These results highlight the limitations of rule-based methods like ChemDataExtractor, which rely on predefined rules and dictionaries. While effective for structured and simple entities, ChemDataExtractor struggles with diverse and ambiguous entity expressions commonly found in materials science texts.

For the NER task focused on cathode materials synthesis, MatBERT exhibited the highest performance, achieving an average F1 score of 88.18% on the test set (Fig. 4a). This superior performance can be attributed to the substantial similarities between the synthesis procedures for cathode materials and those of inorganic materials, which are well-represented in MatBERT’s training corpus. Consequently, the model’s tokenizer demonstrates enhanced word recognition capabilities, leading to improved NER performance in this specific context. In the category of materials information, such as precursors and target materials, MatBERT and BatteryBERT demonstrated superior performance. For instance, MatBERT achieved an F1 score of 86.97% in recognizing ‘target materials’ entities, whereas SciBERT scored 81.97%. This superior performance of MatBERT likely stems from its specialization in materials knowledge. Conversely, for quantitative information categories such as ‘temperature’, ‘time’, and ‘ratios’, SciBERT and BERT show better performance. This finding suggests that domain-specific adaptation of language models may diminish their ability to recognize general numerical information.

a Abbreviated categories for cathode material synthesis, i.e., precursors (PREC), temperature (TEMP), target materials (TM), atmosphere (ATM), ratio (RAT), active materials (ATM), company (COMP), method (METH), solvent (SOLV), speed (SPE), wash solvent (WS), solution (SOL) and coating (COAT). b Abbreviated categories for cell-assembly process, amount (AMO), solvent (SOLV), and active materials. (AM), binder (BIND), conductive agent (CA), anode (ANO), cathode solvent (CS), current collector (CC), temperature (TEMP), company (COMP), separator (SEPA), and pressure (PRES).

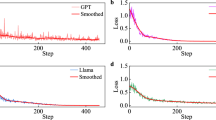

For the cell-assembly NER task, BatteryBERT is the best-performing model, exhibiting the highest average F1 score of 94.61% on the test set (Fig. 4b). We attribute the abundant battery knowledge of BatteryBERT to its superior performance, as it encompasses various terms about battery cell components, such as the anode and active materials that are exclusive to the context of battery technology. Specifically, for the anode entity, BatteryBERT achieved an F1 score of 90.21%, outperforming other models such as BERT (87.22%), SciBERT (87.64%), and MatBERT (89.65%). Similarly, the BatteryBERT-based model demonstrated a superior ability to recognize ‘conductive agents’ entities, achieving a higher F1 score (93.60%) compared to other models (BERT: 86.77%, SciBERT: 90.82%, MatBERT: 91.53%). This finding suggests that the BatteryBERT model exhibits a specialized contextual understanding of battery-related literature, enhancing its performance in identifying materials with specific roles such as ‘anode’ (90.21%) or ‘active materials’ (95.93%) within battery systems. Conversely, for categories such as salts and solvents that are relevant across numerous material domains beyond batteries, MatBERT—designed to comprehensively cover the literature on inorganic materials—demonstrated superior performance with F1 scores of 94.79% and 96.74%, respectively. Categories with low annotation frequency, including PRES entities, exhibited relatively lower performance across all models, as detailed in Supplementary Table 3. This limitation is likely due to the insufficient annotation data, which reduces the models’ ability to learn effective patterns for these entities. Since battery recipes inherently follow a structured sequence from precursor selection to final assembly, the relationships between entities are naturally inferred from their sequential order in the extracted text. As a result, explicitly modeling entity relationships is less critical, as key insights can be effectively captured through well-structured entity extraction. Given this structured approach, we also explored the potential of utilizing LLMs for NER tasks. Detailed performance metrics and methodologies are provided in the Methods section and Supplementary Information (Supplementary Tables 8 and 9; Supplementary Fig. 1). Specifically, five-shot learning with GPT-4 (‘gpt-4-0416’) achieved notable F1 scores of 82.58% and 86.89% for cathode material synthesis and cell assembly, respectively, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. However, the results obtained from prompt engineering differ in format from those of standard NER outputs, making direct performance comparisons challenging. While recent advances in LLMs, such as GPT-4, have demonstrated competitive performance in NER tasks52,53, their application to large-scale battery data extraction presents several challenges, including cost, consistency, and interpretability54. Unlike traditional NLP approaches such as BERT-CRF, which offer greater transparency and domain-specific fine-tuning, LLMs often function as black-box models, making structured entity extraction more difficult. Additionally, GPT-4’s computational expense at scale significantly exceeds that of BERT-based models, which are more efficient and cost-effective for large-scale text extraction tasks, as shown in Supplementary Table 11. Another fundamental difference lies in how these models represent entity spans. BERT-based NER models explicitly output both entity labels and precise token positions (start and end indices), allowing for more structured and detailed information extraction. In contrast, GPT-based models generate entity values as free text without inherent token position information. Extracting structured token spans from GPT outputs requires additional prompt engineering, which increases both input and output complexity, further amplifying computational costs. Due to this fundamental difference in output format, direct performance comparisons between BERT-based and GPT-based NER models remain inherently challenging.

GPT performance and fine-tuning analysis model

In addition to BERT-based models, we further explored the potential of GPT-based models, including GPT-3.5 Turbo and GPT-4o, for battery recipe information extraction. To evaluate their performance, we employed zero-shot, five-shot, and fine-tuned settings. Distinct performance patterns across entity categories emerged, as summarized in Supplementary Tables 8 and 9. While GPT-4o achieved competitive results in several categories with five-shot learning, certain limitations were observed. In particular, it exhibited difficulties in processing complex sentence structures, often misinterpreting intricate descriptions or producing inconsistent outputs. For example, sentences containing ambiguous references to chemical names or experimental procedures were occasionally misclassified. Additionally, both GPT models struggled with domain-specific challenges, especially when identifying rare battery-related terminology or specialized chemical entities.

Another notable limitation was the tendency of GPT models to generate unintended entities, even when explicitly instructed to extract only predefined categories. For instance, when prompted to extract conditions such as Temperature and Time, the models sometimes inserted additional, non-existent terms like Heating Material or Cooling Step, resulting in errors. This behavior reflects the challenge of ensuring strict adherence to specific entity types through prompt engineering alone. Interestingly, GPT-4o occasionally attempted to infer missing details when faced with incomplete input. For example, given the sentence “Stir the mixture at 70 °C”, the fine-tuned model sometimes fabricated hypothetical completions such as “for 30 minutes,” even though no such duration was provided. This tendency underscores the generative nature of GPT models, which may introduce hallucinated details when processing underspecified or ambiguous content.

To address these issues, we fine-tuned both models using annotated battery literature. In the cathode synthesis task, fine-tuning led to performance improvements of up to 7.02% compared to the GPT-4o five-shot baseline, particularly in categories such as PRECURSOR, TARGET MATERIAL, TEMP, and TIME. In the cell assembly task, fine-tuning similarly improved performance, with gains of up to 4.17% in categories such as SEPARATOR and TIME. Additionally, for GPT-3.5 Turbo, fine-tuning resulted in an overall average improvement of 5.56% over the five-shot approach, indicating consistent benefits across diverse entity types. Despite these improvements, some categories, such as RATIO and COAT showed limited gains, likely due to insufficient training examples and the inherent ambiguity of expressions found in the dataset.

These observations suggest that while GPT models demonstrate strong adaptability through few-shot learning and show notable improvements with fine-tuning, challenges remain in controlling unintended generation and managing linguistic ambiguity. By contrast, the BERT-CRF model exhibited superior consistency and precision in structured entity extraction, making it more suitable for high-reliability battery recipe NER tasks. Nevertheless, the flexibility and generalization capacity of GPT models present promising avenues for future research, particularly for tasks involving complex or loosely structured scientific language.

NER-based battery research trend analysis

We applied the highest-performing NER models to the remaining paragraphs to extract all entities from battery recipe papers. Specifically, we employed the MatBERT-based NER model for 2776 paragraphs associated with cathode material synthesis and the BatteryBERT-based model for 2758 paragraphs related to battery cell assembly. Based on the information extraction results, we were able to reveal the relationships between entities in cathode materials synthesis or battery cell assembly paragraphs (Fig. 5).

In heatmaps, the color represents the normalized number of relevant papers. a Relationships between atmosphere and temperature in cathode materials synthesis. b Relationships between salt and solvent in cell assembly. c Relationships between synthesis method and precursor materials in cathode materials synthesis. Here, CVD refers to chemical vapor deposition. d Dependency relationships between precursor materials.

As shown in Fig. 5a, the atmosphere used for synthesizing the cathode material is predominantly Ar, followed by N2, H2, air, and vacuum. In summary, 77% of cathode material synthesis occurs in an Ar or N2 atmosphere at temperatures between 0 °C and 100 °C or 600 °C and 800 °C, with room temperature being the most common. Above 1000 °C, the synthesis is primarily conducted in an atmosphere of Ar, N2, air, or H2. However, less frequently, environments such as C2H2, CH4, O2, or vacuum are also used. Under sub-zero conditions, the synthesis primarily uses atmospheres of Ar, followed by N2, inert gases, air, H2, and vacuum conditions. In Fig. 5b, the combination of LiPF6 with ethylene carbonate (EC) and dimethyl carbonate (DMC) predominates as the salt and solvent in most cases. EC is used due to its high dielectric constant and wide electrochemical stability window, which facilitate the dissociation of LiPF6 and enhances battery stability. DMC is selected for its low viscosity and excellent electrochemical stability, which, when combined with EC, improve the electrolyte’s flow properties and overall performance. In addition, EC solvent is occasionally mixed with solvents such as ethyl methyl carbonate (EMC), dimethyl ether (DME), propylene carbonate (PC), and dioxolane (DOL), whereas vinylene carbonate (VC), dimethoxymethane (DMM), dimethylformamide (DMF), and acetonitrile (CAN) are used less frequently.

In Fig. 5c, the association relationships between precursor materials and synthesis methods in battery cell assembly are visualized. From the perspective of precursors, our dataset on LFP batteries indicates that Li, Fe, and PO4 sources are the most frequently extracted, with Li2CO3, FeC2O4, and NH4H2PO4 being the most commonly used. Most studies adopted the solid-state method for synthesizing uniformly formed LFP particles, primarily using Li2CO3, FeC2O4, or NH4H2PO4 as precursor materials. For hydrothermal methods, LiOH, FeSO4, or H3PO4 precursors are used, whereas H3PO4 and LiOH are frequently selected in the solvothermal method as well. They are selected because of their ability to act as a versatile reactant under elevated temperatures and pressures in aqueous or solvent environments, facilitating controlled crystallization and the formation of desired nanostructures or complex compounds with tailored properties. The sol-gel method was mainly employed for handling citric acid or NH4, whereas the precipitation, rheological phase, or polymerization method was sometimes used for FeSO4, NH4, and S, respectively. In Fig. 5d, the dependency relationships of precursor materials in battery recipes are analyzed. In summary, Li2CO3 and NH4 are frequently used together, because of their ability to efficiently provide lithium ions and facilitate the formation of homogeneous and high-purity cathode materials. In addition, there are dominant combinations such as LiOH–H3PO4, FeSO4–LiOH, FeC2O4–NH4, FeSO4–H3PO4, and Li2CO3–FeC2O4. In addition to these results, we analyzed the relationships between temperature–time and temperature–action in cathode materials synthesis and binder–conductive agent and temperature–action in battery cell assembly (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Battery recipe pattern analysis and retrieval

In addition to the NER results, we extracted the synthesis action information to provide the full information of end-to-end battery recipes as sequences. To this end, we used the pre-trained text-mining toolkit for inorganic materials synthesis47, which classifies the verbs related to synthesis action into eight categories such as ‘starting’, ‘mixing’, ‘purification’, ‘heating’, ‘cooling’, ‘shaping’, ‘reaction’, and ‘non-altering’ based on the context. Based on the information extraction results, we identified the most probable synthesis action sequences for cathode material synthesis and battery cell assembly. The results of sequence probability modeling are presented in Fig. 6, which effectively highlights the flow of probabilities across the synthesis steps and provides a clear understanding of the sequential progression and dominant patterns in each process.

The sequence probabilities were calculated by cumulatively determining the conditional probabilities of each step based on the sequences found in the cathode material synthesis paragraphs or the cell assembly process paragraphs. a, b 2840 and 2511 sequences, related to cathode materials synthesis and cell assembly paragraphs, respectively, are analyzed.

Here, we assumed that the sequential mention of synthesis actions in the text represents the order of the synthesis process and displayed the synthesis actions and NER results according to the order of sentence appearances in the sequence data. To extract and classify these synthesis actions, we adopted the ULSA (Unified Language of Synthesis Actions) model47, a framework specifically designed for inorganic synthesis protocols, which provides a standardized representation of synthesis actions. Using this framework, verbs extracted from synthesis paragraphs were mapped into eight predefined synthesis steps: ‘starting,’ ‘mixing,’ ‘purification,’ ‘heating,’ ‘cooling,’ ‘shaping,’ ‘reaction,’ and ‘non-altering. This mapping enabled the effective construction of structured synthesis sequences, with 2840 sequences derived from cathode material synthesis paragraphs and 2511 from battery cell assembly paragraphs. This entire process—from raw text extraction and synthesis action identification using domain-specific BERT models, to the mapping of verbs such as ‘prepared,’ ‘dissolved,’ and ‘stirring’ into standardized steps like ‘starting’ and ‘mixing’—is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 4. It highlights the structured representation of synthesis actions, enabling a systematic analysis of synthesis protocols.

Next, we aimed to uncover potential causal relationships between synthesis actions by probabilistically analyzing the previously derived cathode material synthesis sequences (N = 2840) and cell assembly sequences (N = 2511). As a result of analyzing sequences of synthesis actions in cathode material synthesis paragraphs, the sequence with the highest probability is identified as <‘starting’ → ‘mixing’ → ‘purification’ → ‘heating’ > (Fig. 6a). The reason for this high probability is that the synthesis of cathode materials typically begins with the preparation of raw materials (‘starting’), followed by their combination to ensure uniformity (‘mixing’). Subsequent purification steps are crucial to remove impurities that could affect material performance, and finally, heating is applied to induce the necessary chemical reactions and phase transformations. An analysis of 2511 sequences of synthesis actions in cell-assembly process paragraphs identified the most probable sequence as <‘starting’ → ‘mixing’ → ‘non-altering’ → ‘purification’ > (Fig. 6b). The reason for this high probability is that the cell-assembly process typically begins with the preparation of initial components (‘starting’), followed by their combination to ensure homogeneity (‘mixing’). The non-altering step involves procedures that do not change the chemical nature of the components, such as coating slurry onto the current collector layers. Finally, purification steps are essential to remove any contaminants that could compromise the performance and longevity of the cell.

Next, we tried to identify end-to-end battery recipes, which encompass the entire process from material synthesis to cell assembly, by linking and filtering the two types of recipes. For this task, the following post-processing steps were conducted. First, we verified whether the source papers of the material synthesis recipe and the cell assembly recipe were the same. Next, we confirmed whether the target material resulting from the cathode material synthesis sequence and the active material, which is the starting material for the cell assembly sequence, were the same. Then, we utilized a predefined dictionary-based approach to confirm whether the target material from the cathode material synthesis sequence matched the active material used as the starting material in the cell assembly sequence. The dictionary, which was constructed by integrating existing chemical databases and manual curation, contained normalized representations of chemical entities, including standard chemical formulas, synonyms, and common abbreviations (e.g., “LiFePO4” = “LFP”). For example, a target material such as “LiFePO4” in the synthesis sequence was matched with the active material “LFP” in the assembly sequence using this dictionary.

Finally, we ensured that the precursor and synthesis methods were clearly specified in the given recipes, thereby identifying 165 end-to-end recipes. The reason why the number of end-to-end recipes is relatively small is that not all LFP battery studies cover the entire process from material synthesis to cell assembly. In the collected dataset, numerous instances were found where only the cathode synthesis process was detailed, primarily concentrating on material synthesis and characterization. For instance, when the research objective involves analyzing the morphological characteristics of specific materials such as FePO4 and LiFePO4, the aim is to understand the structure, size, and thermal behavior of these materials55,56. Consequently, the focus is on their physical and chemical properties, with no evaluation of the electrochemical performance of the battery cell. Furthermore, several studies concentrated exclusively on the synthesis process of LiFePO4 particles and their properties during synthesis57,58. Conversely, in instances where only the cell assembly process was described, the cathode was often procured commercially, with only the source being specified. These studies typically omitted descriptions of the cathode synthesis process59,60,61,62.

Based on this recipe database, an interactive battery recipe information-retrieval system can be developed, as illustrated in Fig. 7. If precursor materials are limited and only solid-state synthesis methods are available, users can search our database to find relevant recipes, including cathode synthesis, cell assembly, or end-to-end types. Searching with a query such as “((‘sucrose’). PREC.) AND ((‘solid state’). METHOD) AND ((‘end-to-end’). TYPE)” provides the following end-to-end recipe: In Step 1, the target material, LiFePO4/C, is synthesized from raw materials such as LiH2PO4, FeC2O4·2H2O, 5% sucrose, and 5% citric acid. In Step 2, a slurry is prepared using LiFePO4 (‘active material’), Super P (‘conductive agent’), and PVDF (‘binder’), which is then coated onto aluminum foil to form the cathode. Next, the anode is prepared using lithium foil, and a microporous PE film is inserted between the two electrodes to serve as the separator. Finally, the electrolyte, consisting of LiPF6 mixed with EC and DEC solvents, is added to complete the battery cell assembly. In this way, by using certain precursor elements or synthesis method conditions as input, it is possible to provide the complete recipe for material synthesis or cell assembly.

Conclusion

In this work, we aimed to systematically and automatically extract end-to-end battery recipes from the scientific literature using a language modeling-based protocol, i.e., T2BR. First, we developed ML-based text classification models to discern the papers related to battery recipes from the information-retrieval results, leading to the filtering of 2174 valid documents with a high F1 score of 85.19%. Next, we conducted topic modeling at the paragraph level, efficiently identifying 2876 and 2958 paragraphs about cathode materials synthesis and cell-assembly processes, respectively. We developed two deep-learning-based NER models, each designed to extract 15-type entities— one model focused on cathode materials synthesis (e.g., precursors, target materials) and the other targeting entities associated with cell-assembly processes (e.g., active materials, anode). These models exhibited high average F1 scores of 88.18% and 94.61%, respectively, enabling the automatic extraction of battery recipe entities from the remaining ~5500 paragraphs. In addition, we extracted the synthesis action using a materials-aware NLP toolkit47, thereby generating 165 sequences representing the overall process of battery recipes. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to collectively extract end-to-end battery recipes from large-scale scientific literature, paving the way for a generalized approach to the knowledge base construction of battery materials.

We acknowledge several limitations of the current study and propose directions for future research. First, our analysis is based on a limited dataset of LiFePO4 battery literature, collected exclusively from a single search engine. Consequently, some reports based on information extraction results may exhibit bias. However, our protocol is adaptable and can be applied to an expanded dataset that includes other battery systems63,64 such as lithium-ion batteries consisting of LiCoO2 and LiMn2O4 cathode materials, as demonstrated by several examples in Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6. The second limitation arises from the lack of connection between battery recipes and the electrochemical performance of the batteries. Our protocol enables the extraction of battery recipe information, not providing quantitative information on the electrochemical profile of batteries such as the voltage–capacity curve, charge/discharge curve, cycle life, energy density, and current–voltage curve. Considering that the long-term goal is to identify the optimal battery recipe by linking our end-to-end battery recipes with performance data, it is essential to analyze additional information from tables and figures65 as well as extract relationships between entities from text. Finally, we have identified potential areas for performance enhancement in the proposed protocol, likely attributable to discrepancies between the predefined categories and actual data. The diverse and complex terminology employed by materials scientists when referring to battery components may contribute to this performance degradation. Consequently, it is imperative to use an annotation dataset that ensures both quality and diversity. For categories with limited datasets (e.g., method, solvent, solution, coating, pressure), augmenting existing data, rather than merely increasing tagging sets, may serve as a viable alternative. Moreover, exploring other state-of-the-art models, such as pointer networks for NER, could potentially improve contextual understanding and final output performance. For instance, applying fine-tuning of LLMs presents an opportunity to develop an NER model specific to battery recipe extraction53,66. For instance, applying fine-tuning of LLMs presents an opportunity to develop an NER model specific to battery recipe extraction, in line with recent advancements in AI-driven materials research67,68,69,70. Considering the presence of exceptional cases, such as the intertwining of cell assembly and material synthesis information in a single paragraph, generative models could potentially offer a solution in the future.

Methods

Paper-level text classification models

We classified battery recipe-related papers from the information-retrieval results in a systematic manner. Initially, we manually reviewed the abstract and title information of 1000 randomly selected papers to determine their relevance to battery recipes. This process resulted in 281 relevant and 719 irrelevant papers. We used this labeled dataset to develop a paper classification model. First, we applied TF-IDF to represent the text as vectors using the scikitlearn, generating a 1000 × 10,592 matrix. We then developed five classification models using AutoML in the H2O module71: random forest (RF), logistic regression (LR), gradient boosting machine (GBM), multi-layer perceptron (MLP), and XGB. To optimize the hyperparameters for each ML model, we conducted a grid search based on fivefold cross-validation, using the F1 score as the performance evaluation metric.

The optimal parameters identified were as follows: the number of trees and maximum depth were 50 and 20 for the RF. The family was set as binomial distribution, and the minimum lambda, beta epsilon, theta, and stopping tolerance were set as 0.0001, 0.0001, 1e-10, and 0.001, respectively, for LR. The following parameters were set for GBM: sample rate = 0.8, learning rate = 0.1, stopping tolerance = 0.001, stopping metric = log loss, maximum depth = 15, and number of trees = 50. Three hidden layers of 100 nodes, an Adam optimizer with a 0.005, a rectified linear unit as the activation function, and a dropout rate of 0.5 for MLP were used. For XGB, the following parameters were used: number of trees = 110, maximum depth of the trees = five levels, learning rate = 0.03, a scale of positive weight = 2, minimum child weight = 2, and minimum split loss = 3. Among these models, the optimized XGB model demonstrated the highest performance, as shown in Supplementary Table 10. We then applied this model to the remaining 4885 papers. Combining the 281 manually labeled papers with the prediction results, where 1893 papers were classified as relevant, we identified a total of 2174 papers related to battery recipes.

Paragraph-level topic modeling

We conducted paragraph-level topic modeling using Python libraries such as Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK)72 and gensim73. First, NLTK was used for pre-processing such as tokenization and stopwords elimination, where common articles such as ‘a’, and ‘the’, and pronouns such as ‘this’ and ‘that’ were excluded. Next, genism was employed to develop the LDA model. LDA is a probabilistic model that provides insights into the topics present within a given document46. It estimates topic-specific word distributions and document-specific topic distributions from datasets consisting of documents and their constituent words. This inference process relies on the assumption of distributions following the Dirichlet distribution, a common practice in Bayesian models of multivariate probability variables. In essence, LDA posits that words within a document are generated based on the joint distribution of topic-word distributions and document topic distributions and utilizes Gibbs sampling to infer these distributions from the observed word distribution within the document.

LDA involves two hyperparameters: α and β. The former determines the density of document topic relationships, whereas the latter indicates the density of topic-word relationships. Their higher values lead to more uniform probabilities across topic distributions, whereas lower values emphasize specific topic distributions. We set these parameters as 5.0 and 0.01. In addition, we determined the number of topics as 25 based on coherence and perplexity scores. Perplexity gauges the efficacy of a probability model in predicting observed values, with lower values indicating superior document–model alignment. Coherence, on the other hand, evaluates the semantic consistency within topics74. As modeling accuracy increases, topics tend to aggregate semantically related terms. Consequently, by assessing the similarity among primary terms, we ascertain the semantic coherence of topics. Through exhaustive testing across topic numbers ranging from 1 to 40, we identified 25 topics characterized by an optimal balance between low perplexity and high coherence. For the visualization of topic modeling results, we used the LDAvis Python library, which provides an interactive web-based visualization.

Pre-trained language model configuration

For the NER tasks, we employed the BERT-CRF model. We tested a range of pre-trained language models, including BERT (‘bert-base-uncased’), SciBERT (‘scibert_scivocab_uncased’), MatBERT (‘matbert-base-uncased’), and BatteryBERT(‘batterybert-uncased’). These models were fine-tuned on our specific dataset to enhance domain-specific entity recognition and contextual understanding. Each model was originally pre-trained on distinct domain corpora, leading to variations in their word recognition and contextual comprehension capabilities. Specifically, BERT was trained on general knowledge sourced from books and Wikipedia text (~3300 M words), whereas SciBERT was trained on research papers from the fields of biology, medicine, and computer science (~3170 M words). MatBERT was trained on materials science research papers (~8.8B words), and BatteryBERT was fine-tuned based on BERT, specifically using papers from the field of battery materials (~1870M words). BERT-based models are trained with two tasks such as masked language modeling, which predicts masked words within a given sequence, and next sentence prediction, which discerns relationships between sentences. Their contextual understanding capabilities vary depending on the corpus used for training, which directly affects their performance across NLP tasks in different domains. Furthermore, each BERT model utilizes a distinct tokenizer, as they rely on the byte pair encoding algorithm. Consequently, the level at which consecutive character sequences, appearing with a certain frequency in the corpus, are recognized as a single token varies depending on the corpus used. The word ‘LiFePO4’ can be tokenized either as a single entity or segmented into multiple tokens–‘LiFe’, ‘PO’, ‘4’ (Supplementary Fig. 7).

NER model development

After tokenization, we annotated the tokens using the IOBES tagging scheme, which classifies each entity into subtypes to indicate whether a token is inside (I), outside (O), at the beginning (B), or the end (E) of multi-token entities as well as single-token entities (S). This scheme is effective for handling compound words, as it provides additional information about the boundaries of named entities. This tagging scheme can introduce certain constraints in sequence labeling tasks. For example, an I-tag cannot appear at the beginning of a sentence, and an OI pattern is invalid. In a B-I-I pattern, the named entity must remain consistent; for instance, BAM can be followed by I-AM or E-AM, but not by I-CA. To address these sequence labeling challenges, we employed a CRF layer as the final layer of the NER models. A CRF is a type of SoftMax regression that transforms categorical sequential data into a format suitable for SoftMax regression, subsequently used to predict sequence vectors.

After model configuration, the dataset with annotations is split into training, validation, and test sets with a ratio of 8:1:1 with stratified sampling. In training NER models, we conducted an exhaustive grid search to optimize the hyperparameters, which are determined as follows: the maximum number of epochs of 50, applying early stopping with the patience of 10, the learning rate of 1e-3, batch size of 5, and optimizer of RangerLars, which is the composite of RAdam, LARS, and Lookahead. We conducted 10-fold shuffle split cross-validation, which is effective in adjusting imbalanced datasets, and verified the performance of the NER models. Next, when evaluating the NER performance for each category, we adopted a lenient evaluation criterion by applying boundary relaxation, considering the diversity and complexity of entity expressions in the materials science and battery recipe domains. Specifically, if any component word of a compound term belonging to a specific category was correctly identified, it was deemed a correct match.

Post-processing of information extraction results

After extracting specific information from the scientific literature, we normalized the entities written in natural language in a qualitative but systematic manner. First, based on frequent entities for each category, we constructed a dictionary of chemical substances. Next, we identified the entities with similar meanings but different entities by conducting pairwise comparisons of frequent entities. Consequently, entities representing the same active materials such as LiFePO4/C, and LiFePO4/Carbon were normalized into the more frequently appearing one such as LiFePO4/C, whereas binder-type entities such as polyvinylidene fluoride and PVDF were unified into PVDF. Finally, these normalization results were used to analyze the battery research trends in depth. When normalizing synthesis time information, all the values were converted to seconds and transformed using a logarithmic scale, divided into 10 intervals for analysis. ‘Overnight’ was estimated as 8 h, and ‘few’ and ‘several’ were approximated as 5. For normalizing synthesis temperature information, Kelvin temperatures were converted to Celsius. When temperature ranges were provided, we checked if they fell within 100-degree intervals. For example, if the extracted entity was ‘150–220’, both the 0–100 and 100–200 intervals were marked.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available at https://github.com/KIST-CSRC/Text-to-BatteryRecipe.

Code availability

The source codes used in this study are available at https://github.com/KIST-CSRC/Text-to-BatteryRecipe.

References

Choudhary, K. et al. Recent advances and applications of deep learning methods in materials science. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 59 (2022).

Batra, R., Song, L. & Ramprasad, R. Emerging materials intelligence ecosystems propelled by machine learning. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 655–678 (2021).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: The Materials Project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Kirklin, S. et al. The Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD): assessing the accuracy of DFT formation energies. npj Comput. Mater. 1, 1–15 (2015).

Draxl, C. & Scheffler, M. NOMAD: The FAIR concept for big data-driven materials science. MRS Bull. 43, 676–682 (2018).

Olivetti, E. A. et al. Data-driven materials research enabled by natural language processing and information extraction. Appl. Phys. Rev. 7, 041317 (2020).

Kononova, O. et al. Opportunities and challenges of text mining in materials research. Iscience 24, 102155 (2021).

Choi, J. & Lee, B. Quantitative topic analysis of materials science literature using natural language processing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 1957–1968 (2023).

Choi, J. et al. Deep learning of electrochemical CO2 conversion literature reveals research trends and directions. J. Mater. Chem. A 11 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. A corpus of CO2 electrocatalytic reduction process extracted from the scientific literature. Sci. Data 10, 175 (2023).

Gao, Y., Wang, L., Chen, X., Du, Y. & Wang, B. Revisiting electrocatalyst design by a knowledge graph of Cu-based catalysts for CO2 reduction. ACS Catal. 13, 85258534 (2023).

Glasby, L. T. et al. DigiMOF: a database of metal–organic framework synthesis information generated via text mining. Chem. Mater. 35, 4510–4524 (2023).

Park, H., Kang, Y., Choe, W. & Kim, J. Mining insights on metal–organic framework synthesis from scientific literature texts. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 62, 1190–1198 (2022).

Pei, Z., Yin, J., Liaw, P. K. & Raabe, D. Toward the design of ultrahigh-entropy alloys via mining six million texts. Nat. Commun. 14, 54 (2023).

Huang, S. & Cole, J. M. BatteryBERT: a pretrained language model for battery database enhancement. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 62, 6365–6377 (2022).

Huang, S. & Cole, J. M. BatteryDataExtractor: battery-aware text-mining software embedded with BERT models. Chem. Sci. 13, 11487–11495 (2022).

Huang, S. & Cole, J. M. A database of battery materials auto-generated using ChemDataExtractor. Sci. Data 7, 260 (2020).

El-Bousiydy, H., Troncoso, J. F., Johansson, P. & Franco, A. A. LIBAC: an annotated corpus for automated “reading” of the lithium-ion battery research literature. Chem. Mater. 35, 1849–1857 (2023).

Gou, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhu, J. & Shu, Y. A document-level information extraction pipeline for layered cathode materials for sodium-ion batteries. Sci. Data 11, 372 (2024).

Brown, T. et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 1877–1901 (2020).

Jin, Q., Yang, Y., Chen, Q. & Lu, Z. GeneGPT: augmenting large language models with domain tools for improved access to biomedical information. Bioinformatics 40, btae075 (2024).

Telenti, A. et al. Large language models for science and medicine. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 54, e14183 (2024).

Yu, S., Zhang, Y., Kim, J., Wang, L. & Chen, X. Large-language models: the game-changers for materials science research. Artif. Intell. Chem. 2, 100076 (2024).

Lei, G., Liu, Y., Zhao, T., Chen, W. & Ong, S. P. Materials science in the era of large language models: a perspective. Digit. Discov. 3, 1257–1272 (2024).

Foppiano, L., Wang, Z., Wu, Y., Wang, L. & Cole, J. M. Evaluation of large language models for information extraction in materials science. Nat. Commun. 15, 1418 (2024).

Vangala, S. R., Zhang, C., Lin, A., Mo, Y. & Kim, S. Suitability of large language models for extraction of high-quality chemical reaction dataset from patent literature. J. Cheminform. 16, 131 (2024).

Schulze Balhorn, L., Meier, J., Hoffmann, M. & Schneider, G. Empirical assessment of ChatGPT’s answering capabilities in natural science and engineering. Sci. Rep. 14, 4998 (2024).

Luo, K., Li, Y., Wang, X., Zhou, H. & Zhang, Y. Large language models surpass human experts in predicting neuroscience results. Nat. Hum. Behav. 9, 225–234 (2024).

Zhang, W., Chen, J., Li, M., Yang, Y. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Leveraging GPT-4 to transform chemistry from paper to practice. Digit. Discov. 3, 2367–2376 (2024).

Zhao, S., Liu, Y., Kim, J., Wang, L. & Xu, S. Potential to transform words to watts with large language models in battery research. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 5, 101844 (2024).

Duffner, F. et al. Post-lithium-ion battery cell production and its compatibility with lithium-ion cell production infrastructure. Nat. Energy 6, 123–134 (2021).

Park, N., Lee, M., Jung, H. & Nam, J. Complex rheological response of Li-ion battery anode slurries. J. Power Sources 608, 234607 (2024).

Li, J., Fleetwood, J., Hawley, W. B. & Kays, W. From materials to cell: state-of-the-art and prospective technologies for lithium-ion battery electrode processing. Chem. Rev. 122, 903–956 (2021).

Li, Z., Zhang, J. T., Chen, Y. M., Li, J. & Lou, X. W. Pie-like electrode design for high-energy density lithium–sulfur batteries. Nat. Commun. 6, 8850 (2015).

Hawley, W. B. & Li, J. Electrode manufacturing for lithium-ion batteries—analysis of current and next generation processing. J. Energy Storage 25, 100862 (2019).

Padhi, A. K., Nanjundaswamy, K. S. & Goodenough, J. B. Phospho‐olivines as positive electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, 1188 (1997).

Yang, H., Shi, X., Chu, S., Shao, Z. & Wang, Y. Design of block‐copolymer nanoporous membranes for robust and safer lithium‐ion battery separators. Adv. Sci. 8, 2003096 (2021).

Lin, C.-E. et al. Carboxylated polyimide separator with excellent lithium ion transport properties for a high-power density lithium-ion battery. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 991–998 (2018).

Bai, S., Liu, X., Zhu, K., Wu, S. & Zhou, H. Metal–organic framework-based separator for lithium–sulfur batteries. Nat. Energy 1, 1–6 (2016).

Ransil, A. & Belcher, A. M. Structural ceramic batteries using an earth-abundant inorganic waterglass binder. Nat. Commun. 12, 6494 (2021).

Zhang, Z., Zeng, T., Lai, Y., Jia, M. & Li, J. A comparative study of different binders and their effects on electrochemical properties of LiMn2O4 cathode in lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 247, 1–8 (2014).

Xu, J. et al. Electrolyte design for Li-ion batteries under extreme operating conditions. Nature 614, 694–700 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. Electrolyte design for LiF-rich solid–electrolyte interfaces to enable highperformance microsized alloy anodes for batteries. Nat. Energy 5, 386–397 (2020).

Tikekar, M. D., Choudhury, S., Tu, Z. & Archer, L. A. Design principles for electrolytes and interfaces for stable lithium-metal batteries. Nat. Energy 1, 1–7 (2016).

Chen, Z. & Dahn, J. Reducing carbon in LiFePO4/C composite electrodes to maximize specific energy, volumetric energy, and tap density. J. Electrochem. Soc. 149, A1184 (2002).

Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y. & Jordan, M. I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 3, 993–1022 (2003).

Wang, Z. et al. ULSA: unified language of synthesis actions for the representation of inorganic synthesis protocols. Digit. Discov. 1, 313–324 (2022).

Devlin J., Chang M.-W., Lee K., Toutanova K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies 1, 4171–4186 (2019).

Zheng S. et al. Conditional random fields as recurrent neural networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision) (2015).

Beltagy, I., Lo, K. & Cohan, A. SciBERT: A pretrained language model for scientific text. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP) 3615–3620 (2019).

Trewartha, A. et al. Quantifying the advantage of domain-specific pre-training on named entity recognition tasks in materials science. Patterns 3, 100488 (2022).

Polak, M. P. & Morgan, D. Extracting accurate materials data from research papers with conversational language models and prompt engineering. Nat. Commun. 15, 1569 (2024).

Dagdelen, J. et al. Structured information extraction from scientific text with large language models. Nat. Commun. 15, 1418 (2024).

Kalyan, K. S. A survey of GPT-3 family large language models including ChatGPT and GPT-4. Nat. Lang. Process. J. 6, 100048 (2023).

Ivanov-Schitz, A., Nistuk, A. & Chaban, N. Li3Fe2 (PO4) 3 solid electrolyte prepared by ultrasonic spray pyrolysis. Solid State Ion. 139, 153–157 (2001).

Scaccia, S., Carewska, M., Wisniewski, P. & Prosini, P. P. Morphological investigation of submicron FePO4 and LiFePO4 particles for rechargeable lithium batteries. Mater. Res. Bull. 38, 1155–1163 (2003).

He, L., Liu, X. & Zhao, Z. Non-isothermal kinetics study on synthesis of LiFePO4 via carbothermal reduction method. Thermochim. Acta 566, 298–304 (2013).

Xu, C., Lee, J. & Teja, A. S. Continuous hydrothermal synthesis of lithium iron phosphate particles in subcritical and supercritical water. J. Supercrit. Fluids 44, 92–97 (2008).

Shim, J. & Striebel, K. A. Cycling performance of low-cost lithium ion batteries with natural graphite and LiFePO4. J. Power Sources 119, 955–958 (2003).

Ge, S. et al. High safety and cycling stability of ultrahigh energy lithium ion batteries. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2, 100584 (2021).

Yuan, C. et al. The abrupt degradation of lifepo4/graphite battery induced by electrode inhomogeneity. Solid State Ion. 374, 115832 (2022).

Pan, X., Liu, L., Yang, P., Zhang, J. & An, M. Effect of interface wetting on the performance of gel polymer electrolytes-based solid-state lithium metal batteries. Solid State Ion. 357, 115466 (2020).

Kim, J. S. et al. Improving the highrate performance of LCO cathode by metal oxide coating: evaluation using single particle measurement. J. Electroanal. Chem. 933, 117190 (2023).

Ali, M. E. S. et al. LiMn2O4–MXene nanocomposite cathode for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Energy Rep. 11, 2401–2414 (2024).

Lee, J., Lee, W. & Kim, J. MatGD: materials graph digitizer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 723–730 (2023).

Choi, J. & Lee, B. Accelerating materials language processing with large language models. Commun. Mater. 5, 13 (2024).

Tian, S. et al. Steel design based on a large language model. Acta Mater. 285, 120663 (2024).

Zheng Z. et al. Large language models for reticular chemistry. Nat. Rev. Mater. 10, 369–381 (2025).

Jiang, X. et al. Applications of natural language processing and large language models in materials discovery. npj Comput. Mater. 11, 79 (2025).

Pyzer-Knapp, E. O. et al. Foundation models for materials discovery–current state and future directions. npj Comput. Mater. 11, 61 (2025).

LeDell, E. & Poirier, S. H2o automl: Scalable automatic machine learning. In: Proceedings of the AutoML Workshop at ICML. ICML San Diego, CA, USA (2020).

Bird, S., Klein, E. & Loper E., Loper E. Natural language processing with Python: analyzing text with the natural language toolkit. “ O’Reilly Media, Inc.” (2009).

Rehurek, R. & Sojka, P. Gensim–Python framework for vector space modelling. NLP Cent. Fac. Inform. Masaryk Univ. Brno, Czech Repub. 3, 2 (2011).

Röder, M., Both, A. & Hinneburg, A. Exploring the space of topic coherence measures. In: Proceedings of the eighth ACM international conference on Web search and data mining) (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2021M3A7C2089739), and Institutional Projects at the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (2E33681). We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Nayeon Kim, a Ph.D. student at the Korea Institute of Science and Technology, for her valuable assistance in editing our figures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.L. conceived the idea. B.L. and H.M. supervised the project. D.L. implemented the research framework, contributed to the design of the research methodology, prepared and annotated the dataset, developed, trained, and evaluated all models, conducted data analysis, and led the manuscript writing and revision. J.C. collected relevant literature, contributed to the design of the research methodology, contributed to the development of the AutoML model, and participated in drafting the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion and writing of the manuscript. All remaining authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jack Evans and Jet-Sing Lee. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, D., Mizuseki, H., Choi, J. et al. Building an end-to-end battery recipe knowledge base via transformer-based text mining. Commun Mater 6, 100 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00825-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00825-z