Abstract

Photo-crosslinkable gelatin-based hydrogels hold great promise for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. However, monitoring these hydrogels in vivo remains challenging and limits their further development and clinical translation. Here, we address this limitation by utilizing a gelatin-based hydrogel that incorporates the radiopaque compound 5-acrylamido-2,4,6-triiodoisophthalic acid (AATIPA). In an in vivo study spanning over 400 days, we monitor the degradation kinetics of these hydrogels using computed tomography and ultrasonography. We synthesize three distinct AATIPA-containing hydrogels and implant them subcutaneously into mice. Hydrogels with high crosslink density show minimal degradation, while those with lower crosslinking densities degrade within approximately three months. Histological evaluation reveals that the scaffolds are replaced by adjacent adipose tissue. In vitro, adipose-derived stem cells differentiate into the adipogenic lineage, corroborating the in vivo findings. These results highlight the potential of these hydrogels for adipose tissue engineering by enabling in vivo monitoring and offering tailored degradation profiles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

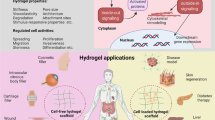

Gelatin-based hydrogels are inexpensive and biodegradable semi-synthetic analogues of the extracellular matrix (ECM) that mimic the ECM properties and support cell adhesion and growth1,2. Moreover, the physico-chemical and biological properties of the gelatin-based hydrogels can be broadly tuned by chemical modifications to meet the demands of various biological applications3. For example, gelatins can be functionalized with acrylates and acrylamides that can be photo-crosslinked. Moreover, such materials can be processed via light-based 3D-printing into any shape required for biological applications. Furthermore, these materials can be co-polymerized with other compounds (acrylic or methacrylic moieties), which endows the final materials with tunable physico-chemical or biological properties3. Thus, gelatin-based hydrogels offer a versatile platform of 3D-printable materials to serve various biological applications, including tissue regeneration as well as plastic and reconstructive surgery, among others3. Most promisingly, gelatin-based hydrogels can support adipose tissue regeneration in plastic and reconstructive surgeries4, including breast reconstructive surgeries following cancer treatment4,5.

Current breast-reconstructive strategies are limited, and they all suffer from major drawbacks. For example, silicone implants may leak and rupture, causing capsular contracture and infection6,7,8. Next, autologous tissue through microsurgical free tissue transplantation results in excessive scar formation on both harvesting and target tissue sites. At last, lipofilling can be applied, but it is often associated with an unpredictable resorption rate9. In contrast, gelatin-based hydrogels can be implanted at the site of interest, where they get colonized by neighboring or co-administered cells that gradually degrade the scaffold and replace it with the body’s own tissue. Therefore, gelatin-based hydrogels may effectively overcome the limitations of current breast-reconstructive surgeries4. While these biomaterials are promising, several unresolved issues remain in their path towards broad clinical application.

For both research on gelatin-based hydrogels and their clinical applications, non-invasive in vivo monitoring of the implants’ fate and the biodegradation of their fragments is crucial, yet challenging. So far, most information regarding the biodegradation of materials originates from ex vivo animal studies10,11, nevertheless, ex vivo provides only limited data, is costly, does not comply with the 3Rs (Reduce, Replace, Refine) principle, and cannot be used in clinical trials10,11. Proof-of-concept studies have reported hydrogels that can be visualized using computed tomography (CT)12,13, positron emission tomography (PET)14, and single photon emission tomography (SPECT)15, in vivo fluorescence imaging16, optical coherence tomography (OCT), ultrasonography (USG)17, and magnetic resonance imaging (1H MRI or 19F MRI)18,19,20,21,22. While these concepts are promising, most imaging techniques cannot be widely exploited because of their limited accessibility due to cost and time constraints (PET, SPECT, MRI), exposure of patients to unnecessary ionizing radiation (CT, PET, SPECT) or limitations regarding depth of penetration (1 to 3 mm for OCT23 and in vivo fluorescence; 1–5 cm for US24). Therefore, an inexpensive gelatin-based implant that supports cell growth which can be reliably visualized with safe, affordable and readily available imaging techniques would pave the way towards entry of gelatin-based hydrogels into broad clinical practice.

Such criteria for imaging techniques could be met with implants that permit visualization with both sonography and X-ray. For most patients, safe, readily available and inexpensive sonography could be used to visualize implants. Whenever an implant is not administrated subcutaneously or the image is ambiguous, such implants can be visualized with radiographic imaging, such as X-ray (or CT). X-ray imaging is readily available and exposes the patient to only minimal amounts of ionizing radiation, but generally provides high resolution images of conventional implants (e.g. orthopedic, dental, breast implants). In extremely unclear situations (e.g. in polytrauma), CT could be employed to identify the presence and location of the implants. Thus, dual imaging hydrogels suitable for sonography and radiology could overcome all imaging limitations of hydrogels and thus enable their broad transition into clinical practice.

To date, several structurally diverse radiopaque hydrogels with covalently bound iodine have been reported25,26,27,28. However, they generally are not 3D-printable. To the best of our knowledge, the only radiopaque 3D-printable hydrogels reported at present were loaded with gold nanoparticles28. However, these hydrogels are costly and prone to potential leakage of gold nanoparticles, lowering their radiopacity over time and thus interfering with in vivo imaging. Moreover, leached gold nanoparticles could cause undesired side effects29. Therefore, an inexpensive, non-toxic co-monomer is required which can be covalently integrated into a hydrogel for accurate in vivo monitoring of its degradation.

Herein, we report on gelatin-based implants that can be visualized in vivo both with ultrasonography and radiography techniques. We recently developed a 5-acrylamido-2,4,6-triiodoisophthalic acid (AATIPA) monomer that endows gelatin-based hydrogels with radiopacity but does not interfere with 3D-printing30. In the current study, we prepared the hydrogels with various degrees of cross-linking and AATIPA content and studied their mechanical properties, gel fraction, and swelling ratio. Next, we implanted/injected these materials as 3D-porous hydrogel scaffolds or injectable hydrogels and observed their in vivo degradation kinetics using USG and CT. We successfully compared the degradation kinetics of 3D-porous scaffolds and injectable hydrogels. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the in vivo detectability of these materials could be highly beneficial in clinical settings for identifying potential issues, such as hydrogel relocation or defects in the 3D structure. Understanding how long the material remains in the body is crucial from a regulatory standpoint, as it informs safety standards for biodegradability and ensures controlled degradation. Our approach may establish a benchmark for future studies on biodegradable hydrogel-based implants, with strong potential for applications in breast reconstruction and beyond.

Study design

In this study, we developed a series of radiopaque gelatin-based scaffolds for radiology (e.g., CT) and USG. We prepared derivatives of gelatin in which various proportions of side-chain primary amines were converted into methacrylamide moieties (MA, ≈70% for gel-MA-70, ≈100% for gel-MA-100). Additionally, in a portion of gel-MA-100, we converted part of its side-chain carboxylic acids with N-(2-aminoethyl)methacrylate (AEMA, gel-MA-AEMA, ≈25% modification of carboxylic acids). Thus, we obtained modified gelatin derivatives with various contents of cross-linkable moieties (MA and AEMA), which were exploited to develop hydrogels with increasing crosslink density, resulting in fine-tuning of the mechanical properties and the degradation kinetics of the cross-linked hydrogels. Subsequently, we photo-cross-linked the modified gelatin derivatives with AATIPA, a monomer that introduces the radiopacity of hydrogels (G70I, G100I, and GAEMAI), or without AATIPA (G70, G100, and GAEMA). AATIPA was selected and optimized in a previous study as a water-soluble, radiopaque monomer suitable for photo-induced radical polymerization30. It contains a high concentration of chemically and biologically inert iodine (>50 wt%) to ensure optimal radiopacity. Additionally, the monomer does not interfere with light-based 3D printing30, making it well-suited for the envisioned application. Next, we investigated the hydrogels’ mechanical properties, polymerization kinetics, cytotoxicity, and suitability of the developed hydrogels to support adipose tissue engineering in vitro. Finally, we used the crosslinking solutions to prepare 3D-porous hydrogels (“scaffolds”) and grinded injectable hydrogels (“injectables”). The samples containing AATIPA were implanted/injected subcutaneously into mice and their degradation was observed with CT and with USG over a timeframe of 3 months. This enable us to assess the impact of the materials’ composition on their in vivo degradation kinetics in a non-destructive way.

Results and discussion

We prepared cross-linked gelatin-based hydrogels with varying content of cross-linkable moieties to tune the crosslink density of the resulting hydrogels. The hydrogels were prepared both with and without the radiopaque AATIPA comonomer (Table 2, Fig. 1). Next, we evaluated the effect of the AATIPA incorporation on the crosslinking kinetics, gel fraction (GF, fraction of material remaining in the crosslinked sample after washing), swelling and mechanical properties, in order to obtain information concerning the effect of AATIPA on the crosslinking efficiency and, more importantly, on TE-related properties of the resulting hydrogels.

A Schematic representation of crosslinking of gelatin derivatives with AATIPA as co-monomer; (B, left) photo, (B, middle) USG fantom, and (B, right) CT fantom of an example of a fabricated 3D-porous scaffold; C depiction of the in vivo implantation/injection of the crosslinked materials and representative CT image of G100I on day 1. The implanted scaffolds were prepared using the negative PLA cylinder-shaped scaffolds with a meander-like pattern consisting of 10 layers, a total height of 3.7 mm, and a diameter of 8.4 mm, and varying pore sizes (approx. 800–100 µm, Table S2). From the resulting 3D-porous scaffolds, cylindrical shapes were punched out with diameters of 0.6 cm and a height of 0.4 cm. The injectables were prepared by freeze-drying crosslinked hydrogel films, followed by grinding them into a fine powder and sieving the powder through a 120 µm industrial sieve. The powder was reswollen in sterile physiological saline and 100–200 µL of the resulting particle solution was injected.

As the storage modulus (G’) of hydrogel materials needs to match that of the target tissue, we measured the G’ of our cross-linked hydrogel with and without AATIPA (Table 1, Figs. S9–S14). The results indicated that the addition of AATIPA did not significantly alter the G’ value (p ˃ 0.5). Notably, the storage modulus of the obtained hydrogels aligns well with the mechanical requirements of soft tissues, such as adipose tissue (G’ ≈ 0.3 to 1.3 kPa), the cervix (G’ ≈ 1.6 to 3.4 kPa), and brain tissue (G’ ≈ 3.0 to 12 kPa), while minor adjustments can simply be realized by modifying the gelatin concentration. For a comparison of the developed materials with a broader range of tissues in terms of mechanics, see Fig. S403,31.

The swelling ratio (SR) slightly increased with the addition of AATIPA, although a significant increase is only observed in case of AEMA-based materials, p = 0.04. Notably, the use of basic media in order to deprotonate the AATIPA’s carboxylic acid groups prior to crosslinking was utilized. This neutralization step was applied for preventing the formation of an acidic environment in vitro and in vivo, thereby mitigating potential negative effects on cells or tissues at the implantation site. Therefore, a possible increase of hydrophilicity with the addition of hydrophilic bis-sodium salt of AATIPA can contribute to the increased SR. The crosslinking kinetics of the hydrogel formulations with and without AATIPA are depicted in Figs. S2–S8. Lastly, the gel fraction (GF) decreased upon incorporating AATIPA, a phenomenon attributed to the leaching of non-crosslinked monomers or oligomers following the crosslinking process. Overall, the obtained materials exhibit properties comparable to those of the crosslinked gelatin control samples, which is highly beneficial for adipose tissue engineering32.

From the developed precursor solutions, the 3D-scaffolds were fabricated exploiting indirect 3D-printing. Indirect 3D printing is a technique that overcomes limitations associated with common additive manufacturing strategies through the use of a sacrificial mold (i.e. negative template). This approach enables the fabrication of intricate and complex architectures that may be unachievable with nozzle-based systems. Additionally, it eliminates the need for optimization of crosslinking kinetics, light dose, photoinitiator or photoabsorber content, and specific viscosity requirements, allowing for a more straightforward and rapid fabrication of 3D structures33. In this study, we used PLA-based negative scaffolds designed as previously described33 to enable the fabrication of scaffolds with ideal dimensions to support adipose tissue engineering (Fig. 1, Section S2 in ESI). For that purpose, the pore size of the resulting scaffolds should fall within the suggested range of 500 – 1000 µm34,35. The 3D-porous hydrogels were characterized using light microscopy (Figs. S17–S22) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Figs. S23–S28). Pore sizes were evaluated in swollen state (Table S2), revealing a direct correlation between swelling properties and pore size. Specifically, the pore size increased with decreasing crosslink density and upon addition of AATIPA, both of which can be attributed to more extensive swelling. All resulting pore sizes were situated well within the targeted range.

We demonstrated that AATIPA increases the radiopacity of gelatin-based hydrogels, thereby enabling to detect these hydrogels via CT. In vitro, the 3D scaffolds containing AATIPA (G70I, G100I and GAEMAI) were well detectable in aqueous environment with computed tomography (CT; Fig. 1 and S30). In turn, analogous scaffolds without AATIPA (G70, G100 and GAEMA) exhibited a radiodensity close to that of water, so they were not distinguishable from water (Fig. S30). Generally, the higher the difference in the radiopacity between a study object and its surrounding tissue is, the smaller the objects can be remain detectable. As an example, increasing the radiopacity from ≈50 to ≈1200 HU (voltage of 120 kV) results in decrease of the smallest volume of material reliably detectable via tomography by more than 10-fold (Fig. S36)30,36,37. In turn, even a higher difference in the radiopacity may be required for reliable plain radiography imaging (X-ray)36. Thus, a high AATIPA content may significantly reduce the lowest detectable volumes of implants.

Noteworthily, all hydrogels were consistently detectable via ultrasonography in vitro (Figs. 1 and S37). Although ultrasonography of implants may be sufficient in some clinical applications, it only holds limited application potential due to already mentioned limitations regarding penetration depth. In turn, radiography techniques (X-ray, CT) may provide superior resolution and can effectively monitor implant volume, shape, and average radiopacity, thus permits the monitoring of homogeneity of degradation, which is important in both research and clinical applications. However, repeated exposure of patients to ionizing radiation is not optimal. For this reason, implants that may be detected with two independent imaging techniques may be beneficial to serve clinical applications.

Finally, we wanted to investigate the biocompatibility of the cross-linked hydrogels and to determine their biodegradation rate in vivo. As hydrogels serving breast reconstruction can be implanted subcutaneously either (a) as scaffolds through skin incision or (b) via direct injection of grinded hydrogels (“injectables”)38, both approaches were herein evaluated (Figs. 1 and 2). We implanted AATIPA-containing 3D-porous scaffolds or injectables (either G70I, G100I, or GAEMAI) at the mouse’s left and right side of the abdomen, respectively. The injectables were prepared as previously described38. Afterwards, we observed the degradation of cross-linked hydrogels via CT and USG.

Degradation of the scaffolds (A) and injectables (B) in vivo, monitored with CT imaging. Light-purple dash rectangle indicates the location of the scaffolds or the injectables. CT scans were acquired using CT modality of Albira PET/SPECT/CT Imaging System (Bruker Biospin, Ettlingen, SRN). A voltage of 45 kV and a current of 400 µA with acquisition time of 30 min were used. The images were reconstructed using a filtered back projection algorithm of Albira Software.

The implantation of the scaffolds was successful for all tested materials. Nevertheless, during the administration of the injectables, some issues did arise. For instance, GAEMAI gel exhibited excessive viscosity, leading to frequent needle occlusion during administration. This challenge hindered consistent delivery, ultimately preventing reliable administration in our study. As a result, GAEMAI injectables were excluded from further kinetic analysis in this study. Additionally, both injectables and scaffolds occasionally contained air bubbles (Fig. S31), which interfered with sonographic imaging but did not affect radiographic measurements. Nevertheless, they were fully resorbed within one week, and thus did not compromise subsequent evaluations. At last, in some cases, the injectables relocated into the surrounding tissue rather than maintaining a compact form at the injection site (Fig. S31). However, in a clinical context, the ability to visualize hydrogels post-injection could provide an important advantage, allowing clinicians to re-administer the material if needed. Despite these challenges, our hydrogels demonstrated their suitability for both scaffold implantation and gel injections. The ability to observe the material post-injection proved to be an invaluable tool, enabling real-time assessment of the hydrogel’s condition and distribution following delivery.

We assessed the volume, surface, average radiopacity (RD) and total radiopacity (RDTOT) of scaffolds and injectables over 106 days (G70I and G100I) and 422 days (GAEMAI) post-implantation to determine the in vivo biodegradation kinetics (Fig. 3, Sections S3 and S5 in ESI). The volume of the materials slowly increased over the first 15–20 days, after which a decline in volume due to degradation was observed. During this the degradation phase, the volume of G70I and G100I scaffolds and injectables decreased rapidly with half-lives of 25 to 35 days (Fig. 3A and Table S35, Section S5 in ESI). The signal of GAEMAI scaffolds did not show any decreasing trend (Table S34), but we could observe slow changes in the surface of the scaffolds and apparent collapse of the pores (Figs. 2A and S35). Remarkably, the hydrogel morphology (i.e. whether administered as scaffold or injectable) only had a minor effect on the hydrogels’ half-life, but the higher surface area of injectables shortens their initial swelling phase (Fig. 3).

A Implant volumes as a function of time; all implants except GAEMAI showed a significant volume decrease over time (p > 0.0001). B Implant surface as a function of time. C Total radiopacity of implants as a function of time. D Average radiopacity of implants as a function of time. # indicates an outlier value. For CT data evaluation, PMOD software version 4.2 was chosen. The number of tested animals was N = 5, except for samples G70I, where N = 4; and GAEMAI, at 422 d, where N = 1. The data were processed in OriginPro 2018 64-bit SR1 b9.5.1.195 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

The CT data reveal key aspects regarding the degradation mechanism of cross-linked hydrogels. First, the initial increase of the sample volume (swelling) is probably caused bulk-type degradation, which decreases the crosslinking density and increases swelling of the material. At one point, the cross-linked network is degraded to such an extent that individual polymer chains are liberated, and the sample volume starts to decrease following first-order kinetics. Since the average radiopacity (RD) remains within similar range, it indicates that the material is degraded from its surface rather than as bulk degradation (which would decrease the RD of the material).

Our findings demonstrated that the biological half-lives of materials can be modulated by adjusting the content of MA/AEMA or co-monomers. When the concentration of MA/AEMA or co-monomers reached a critical threshold, as seen for the GAEMAI scaffolds, the degradation rate significantly decreases. Notably, the gel-MA-based samples (G70I, G100I) exhibited a full degradation within approximately 3 months. This result is comparable to the estimated degradation period of crosslinked gelatine, as reported in literature39. This observation is particularly significant given the established suitability of gel-MA-based hydrogels for applications such as breast reconstruction.

Moreover, we were able to monitor the implants’ degradation using ultrasonography (Tables S27–S32). Importantly, the volume data from USG and CT were in good agreement (Fig. 4) since the values correlated well (R2 = 0.95, Table S34). Nevertheless, the USG systematically underestimates the scaffold volume by 13 ± 3% (Fig. S39). Therefore, we show that degradation of our implants can be monitored using USG, which may pose a major benefit for clinical applications.

Degradation of the scaffolds (A) and injectables (B) in vivo, monitored with USG imaging. Coloured lines indicate the location of the scaffolds or the injectables. USG was conducted using two distinct probes: the MX700 and the MX400 high-frequency ultrasound transducers. These transducers were alternated during the experiment, with the MX400 being used initially and replaced by the MX700 at later stages (after 14 days) to enhance resolution. USG was performed in 3D B-mode, and the parameters were set according to the specifications detailed in the provided imaging presets: MX700 Probe (transmission frequency: 50 MHz, gain: 30 dB, step size: 0.05 mm, ROI: 1–10 mm, width: 9.73 mm) and MX400 Probe (transmission frequency: 30 MHz, gain: 30 dB, step size: 0.1 mm, ROI: 6–20 mm, width: 15.36 mm).

Four months following implantation, we performed histopathological examinations of mice (section S5 in ESI) to study the biocompatibility of our hydrogels, using haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and green trichrome staining. In line with CT and USG data, samples G70I and G100I fully degraded within the time frame of the experiment. Both implants and injectables were replaced with adipose tissue accompanied with minor fibrosis in the shape that resembled the original scaffold or injectable. In turn, GAEMAI scaffolds remained present at the implantation site; but the residual scaffolds of GAEMAI did not cause any major immune reactions and were generally well tolerated. Moreover, histological samples of kidneys, liver, and spleen did not show any pathological signs compared to the control (Fig. 5, and Figs. S41–S44). Interestingly, we observed a higher extent of perivascular lymphocytic infiltrations in the liver in G100I than seen in the control. The reason for these lymphocytic infiltrations in liver specifically in G100I remains unclear, since no conclusive signs of inflammation or hepatocytes’ pathologies were observed. Thus, ex vivo studies corroborated the findings from CT and USG and showed that our hydrogels are well tolerated and support the regeneration of adipose tissue.

Histological findings of the implantation site using H&E staining. Scale bars represent 50 µm and are present in the right bottom corner. In the GAEMAI samples, the remnants of implanted scaffolds can be distinguished (dark violet areas in upper three images). All micrographs were acquired using Leica DM6 B (Leica DM6 B LED Upright light microscope) equipped with K3C (Leica Microscope K3C colour Camera).

The in vivo experiment showed that incorporating AATIPA into gel-MA-based hydrogels enables in vivo tracking without impairing their degradability, biocompatibility, or tissue regeneration properties. In turn, the gel-MA-AEMA-based hydrogel containing AATIPA showed only negligible signs of degradation, indicating its potential applicability as durable gelatin-based materials. The use of such a material would be highly valuable as a gelatin-based coating on long-term degradable materials such as poly(ε-caprolactone) (complete degradation between 2–4 years40), rendering them cell-interactive while enabling in vivo monitoring as well.

Finally, we sought to confirm the suitability of our cross-linked hydrogels for supporting in vitro adipogenic differentiation. For this purpose, we selected G100I, which demonstrated the most appropriate degradation profile—based on our in vivo results—to serve adipose tissue engineering41. Adipose-derived stem cells (ASC) were seeded onto these hydrogels and cultured in vitro, with both their metabolic activity and triglyceride accumulation assessed over time (Fig. 6). Our findings revealed that the incorporation of AATIPA did not negatively impact cellular behaviour. In both conditions, the cells exhibited comparable metabolic activity and successfully differentiated into adipocytes without any significant differences between the groups.

Metabolic activity (A) and triglyceride content normalized with respect to the cell count (B) of cells seeded on G100I scaffolds compared to the control G100. Cells were seeded at a density of 100,000 per scaffold. The measurements were performed in triplicates (N = 3). Cell proliferation was assessed using an MTS assay kit. The absorbance was measured at 580 nm for the MTS assay and at 570 nm for the triglyceride assay using a Bio-Tek EL800 spectrophotometer.

The in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that AATIPA-enriched modified gelatins offer significant advantages over existing gelatin-based hydrogels by enabling in vivo detectability without compromising the properties of the crosslinked gelatins. AATIPA-enriched hydrogels were confirmed to be biocompatible within the scope of this study, did not affect cell-interactive properties, and, when tested for a specific application such as adipogenic differentiation, performed comparably to the control gel-MA-100. In this study, the hydrogels were prepared, washed, and then seeded with cells. Another approach is to encapsulate cells directly during crosslinking, a method essential in the context of bioprinting applications. However, for successful cell encapsulation and bioprinting, all components must be biocompatible even in their non-crosslinked state. The presence of unpolymerized AATIPA monomer may pose a challenge in this regard, warranting further investigation.

Beyond these considerations, AATIPA enhanced the tunability of the hydrogels and provided sufficient contrast for real-time scaffold degradation monitoring. This contrast enabled precise tracking of scaffold volumes as small as ≈50–90 mm3 for bulk scaffolds and ≈10–40 mm3 for injectables, with detection being possible even below 1 mm3. These findings highlight the strong potential of AATIPA-enriched hydrogels for biomedical applications and suggest that this approach could be translated to other hydrogels prepared via radical crosslinking.

Conclusion

In this study, we prepared 3D-porous gelatin-based hydrogels incorporating a radiopaque co-monomer (AATIPA), enabling the in vivo monitoring via radiography and ultrasonography. These hydrogels were implanted into mice either as 3D porous scaffolds or injectable grinded hydrogels, and their degradation was tracked for 422 days. Initial swelling occurred for 15–20 days, followed by first-order kinetic degradation with a half-life of 25–35 days, irrespective of the sample type (scaffold or injectable). The biological half-life of the scaffolds was influenced by the amount of crosslinkable moieties (methacrylamides/methacrylates) present in gelatin. Most hydrogels were fully degraded and replaced by adipose tissue, as evidenced by H&E staining, indicating potential for clinical applications, particularly towards adipose tissue engineering. Notably, samples exceeding a threshold of crosslinkable moieties combined with AATIPA showed minimal degradation within the observed time frame. Our findings suggest that these dual-imaging 3D-porous hydrogels hold promise for future clinical applications, particularly in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Methods

Materials

Acrylic anhydride was purchased from Fluorochem (Derbyshire, UK). Triethylamine (TEA, ≥99%), 2,4,6-triiodoisophthalic acid, acryloyl chloride (99%, ≈400 ppm phenothiazine), methacrylic anhydride (contains 2000 ppm topanol A as inhibitor, ≥94%), 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)carbodiimide (EDC), Dulbecco′s Modified Eagle′s Medium (DMEM), 10 v/v% fetal bovine serum, 2 v/v% calcein-acetoxymethyl (Ca-AM), Penicillin-Streptomycin, ascorbic acid, dexamethasone, β-glycerophosphate, propidium iodide (PI), and deuterium oxide were purchased at Sigma-Aldrich (Diegem, Belgium) and used as received. Ethyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phenylphosphinate was purchased from Speedcure TPO-L (Lambson, UK). Deionized water used in all experiments (resistivity less than 18.2 MΩ·cm) was prepared using an Arium® 611 (Sartorius, Goettingen, Germany) with the Sartopore 2 150 (0.45 + 0.2 µm pore size) cartridge filter. Gelatin type B (isolated from bovine hides by an alkaline process) was supplied by Rousselot (Ghent, Belgium). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 99.85%) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS, 98%) was purchased at Acros (Geel, Belgium). 2-Aminoethyl methacrylate hydrochloride (GAEMA·HCl) was obtained from Polysciences (Conches, France). The dialysis membranes Spectra/Por (MWCO 12,000 to 14,000 g mol−1) were obtained from Polylab (Antwerp, Belgium). The adipose tissue-derived stem cells (ASCs) were purchased from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland).

The modified gelatins gel-MA-100 (exact DS 96%, determined by 1H NMR) and gel-MA-70 (exact DS 66%, determined by 1H NMR) and gel-MA-AEMA (exact DS of amine moieties of 96%, DS of carboxylic groups of 26%, determined by 1H NMR) used are described in our previously study30,42.

Synthesis of 5-acrylamido-2,4,6-triiodoisophthalic acid (AATIPA)

AATIPA was prepared as previously described by a 48 h reaction of 2,4,6-triiodoisophthalic acid with acryloyl anhydride at 80 °C in dry acetonitrile, in presence of catalytic amount of sulfuric acid30.

Synthesis of lithium phenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphinate (Li-TPO-L)

Photoinitiator Li-TPO-L was prepared as previously described by a reaction of the ethyl phenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)-phosphinate with lithium bromide in butan-2-one at 65 °C43.

Preparation of the hydrogel reaction mixtures

The gel-MA-70, gel-MA-100 and gel-MA-GAEMA was left to dissolve together with the AATIPA in ultrapure water (the final concentration of the gelatin 10 w/v % solutions of the modified gelatin) at 50 °C in dark glass vial to protect the solution from the light (exact masses and molar amounts are depicted in Table 2, Fig. S1). To dissolve the AATIPA, 2.5 M NaOH solution was added to deprotonate the carboxylic acids (approx. 150 µL to 100 mg). This results in good solubility of AATIPA salt in water, while the resulting material is not acidic, which improves the cell viability. Nevertheless, if the NaOH concentration is too high, a degradation of gelatine can occur (see Fig. S8). The optimal ratio of AATIPA monomer to MA and/or GAEMA groups has selected based on our previous study30.

In situ rheology—crosslinking kinetics

The crosslinking kinetics were measured using a rheometer Physica MCR-301 (Anton Paar, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) with a parallel plate geometry (upper plate diameter of 25 mm). The 300 μL of each reaction mixture (Table 2) was placed between two plates with 0.35 mm gap. The edges of the plate were trimmed and sealed using silicone grease (Bayer, Sigma-Aldrich, Diegem, Belgium) to prevent sample drying. An oscillation frequency of 1 Hz and a strain of 0.1% were applied. Next, the G’ and G” were monitored during 1 min at 37 °C without any irradiation, after which the solution was irradiated using UV-A light (EXFO Novacure 2000 UV light source at 365 nm using a fluence of 50 mW cm-2) and the evolution of G’ and G” was monitored for 15 min upon continuous UV irradiation.

Preparation of crosslinked films

The 3.0 mL of each solution (Table 2) was injected between two parallel glass plates covered with a thin poly(tetrafluoroethylene) sheet and separated by a 1 mm thick silicone spacer. Next, the solutions were irradiated from both sides with UV-A light (365 nm, 100 mW cm−2) for 30 min. The obtained films were washed (ethanol/water 70:30 (V/V) mixture) during 24 h (washing solution changed at least 5 times during 24 h) and subsequently in ultrapure water for another 24 h (water changed at least 5 times) to obtain transparent hydrogel films GAEMA, G100, G70, GAEMAI, G100I, and G70I.

Rheological examination of the mechanical properties of films

To determine the mechanical properties of the films, prepared film samples with a diameter of 1.4 cm were punched out. The mechanical properties of the films were evaluated using a rheometer Physica MCR-301 (Anton Paar, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) with a parallel-plate geometry (upper plate diameter of 15 mm). The storage (G’) and loss (G”) moduli were quantified by means of oscillation rheology (strain 0.1%, normal force 0.6 N, frequency 0.1–10 Hz). All measurements were performed in triplicate and the standard deviation of G’ was calculated at the frequency of 1.05 Hz.

Preparation of negative PLA scaffolds

The negative PLA molds were printed using an Anet A6 FDM printer. These molds were cylinder-shaped scaffolds with a meander-like pattern consisting of 10 layers, a total height of 3.7 mm, and a diameter of 8.4 mm.

Indirect 3D-printing

The scaffolds were plasma treated using a FEMTO plasma reactor version 3 (Diener Electronic, Ebhausen Germany) for 2.5 min on each side with oxygen at a pressure of 0.8 mbar and a power of 100 W to render the PLA surface hydrophilic. Afterwards, negative scaffolds were submerged into crosslinking solutions in dark vials, which were then placed under vacuum to effectively suck the solutions into the pores of the negative scaffold (Fig. S15). After 1 h under vacuum, the negative scaffolds filled with the crosslinking solution were taken out from the solutions, put on 16-well plate and irradiated from both sides with UV-A light (365 nm, 100 mW cm−2) for 30 min. The obtained scaffolds were submerged in chloroform to dissolve the PLA negative scaffold matric for 24 h (chloroform changed at least 5 times over 24 h) and then the resulting hydrogel scaffold was washed with washing solution (ethanol/water 70:30 (v/v) mixture) for 24 h (washing solution changed at least 5 times) and subsequently in ultrapure water for another 24 h (water changed at least 5 times) to obtain transparent porous hydrogel scaffolds GAEMA, G100, G70, GAEMAI, G100I, and G70I. The scaffold for in vivo experiment were transferred from the ethanol/water 70:30 (v/v) mixture directly to sterile PBS solution (PBS changed at least 5 times in a sterile environment). The size of the scaffolds was additionally adjusted prior to implantation with 0.6 mm sterilized puncher.

Preparation of injectable hydrogels

Crosslinked films sterilized with 70% ethanol were freeze-dried and added to the mortar together with small addition of liquid nitrogen (Fig. S29). The frozen film was then grinded into fine powder, which was then sieved through 120 µm industrial sieve. The powder reswollen in sterile physiological saline solution before the in vivo injection.

Determination of gel fraction (GF)

To measure the gel fraction, we freeze-dried a sample of swollen film (diameter 8 mm) immediately after polymerization and measured its mass (mdry,crude). Afterwards, this dry material was incubated in ultrapure water at 37 °C for 24 h and the supernatant was removed. After washing, we freeze-dried and weighted the crosslinked sample mass again (mdry,washed). The gel fraction was determined by Eq. (1). GF values were determined in 3 independent measurements and reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Determination of swelling ratio (SR)

To determine the swelling ratio (i.e., the ratio between PBS swollen hydrogel and dried crosslinked material), a sample of washed and swollen 3D-porous scaffold was gently dried using tissue paper (to get rid of excess water) and weighted (mswollen). Afterwards, the samples were washed with water, freeze-dried, and weighted as dry mass (mdry). The swelling ratio was then calculated using Eq. (2). SR were determined in 3 independent measurements and reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Elemental analysis

We freeze-dried our hydrogels for 48 h at 0.2 kPa. Afterwards, we used PE 2400 Series II CHN Analyzer (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) analyzed the H, C, N, and I content in two independent measurements (Table S1). The iodine content was measured as previously described30.

Light microscopy

Washed and equilibrium swelled (ultrapure water) 3D-porous hydrogels were observed with a Zeiss Axiotech 100 HD/DIC optical microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) at 5× magnification.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The samples for SEM were air dried from ethanol and coated with the nano-layer of gold using an Automatic Sputter Coater K550X with a RV3 two stage rotary vane pump (Emitech/Quorum Tech., East Sussex, UK). The images were obtained using JCM-7000 NeoScope™ Benchtop SEM (JEOL Europe BV, Nieuw-Vennep, Netherland).

Characterization of the sonographic properties of prepared hydrogels

All materials were characterized using a PHYWE Ultrasonic Echoscope (Göttingen, Germany) operating at 2 MHz in A-mode with a digital sampling frequency of 50 MHz. For each material, a cylindrical sample (precursor solution crosslinked directly in Eppendorf tubes) was prepared, each with a known length (i.e., the distance between cylinder bases). Each cylinder was placed coaxially between an ultrasound transmitter and receiver, which were tightly pressed against the sample. The samples were carefully aligned so that the ultrasound waves entered and exited perpendicularly to the cylinder bases, enabling accurate measurement of sound propagation time. The measured time between ultrasound transmission and detection (t) comprises two components: a “dead time” (t0) due to the inherent lag in the transmitter and receiver (which remains constant for all measurements) and the actual propagation times through sample 1 (t1) and sample 2 (t2). We recorded the receiver’s signal intensity as a function of time after the pulse (Figure S38), identifying the time to signal onset (t), the first peak (tp1), and the second peak (tp2).

We measured the signal intensity in the receiver probe as a function of time after transmitting the pulse (Figure S38). Thereby, we measured the time to onset of the signal (t), time to peak 1 (tp1) and time to peak 2 (tp2).

The sound propagation velocity (v) was determined with Eq. (3),

where d1 and d2 are the lengths of each cylinder sample.

Using the same setup, we also determined the effective attenuation. This measurement analyses the time sequence of the received signal to identify two key peaks. The first peak represents the direct passage of the ultrasound wave through the material, while the second, lower-amplitude peak results from a double reflection (the signal reflects off the receiving probe back to the transmitter and then again to the receiver). The material’s attenuation is determined from the amplitude ratio of these peaks according to:

where A1 is the amplitude of the first peak and A2 is that of the second. To obtain the attenuation for a single passage (accounting for the additional transit in the double reflection), the effective attenuation is divided by two and normalized by the sample thickness (d), yielding the attenuation in dB/mm:

This normalization allows for a direct comparison of attenuation across samples of different thicknesses. All the results are depicted in Table S33.

CT and USG measurements

The animal experiments described in this manuscript were approved by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic (approval No. 46307/2020-3. All procedures were conducted in accordance with Act No. 246/1992 Coll., on the Protection of Animals Against Cruelty, as amended by Act No. 501/2020 Coll., and Decree No. 158/2021 Coll., which align with Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Inbred Balb/c mouse (female, 12 weeks old) was used for the experiment. Surgery and CT examination were performed under isoflurane anesthesia (3% for initial and 1.5% for maintenance anesthesia). After the mouse was shaved, scaffolds and injectables were implanted subcutaneously on the animal’s back, each on one side of the body. Scaffolds were placed about 1 cm from entry incision, which was treated with tissue glue (Leukosan Adhesive), injectables were applied via injection (100–200 µl of suspension). Subsequently, CT scan was acquired using CT modality of Albira PET/SPECT/CT Imaging System (Bruker Biospin, Ettlingen, SRN) and ultrasound scans were acquired with VEVO 3100/LAZR-X multimodal ultrasound imaging platform (FUJIFILM VisualSonics, Inc., Toronto, Canada). For the CT scans, the voltage of 45 kV and the current of 400 µA with acquisition time of 30 min were used. After the end of CT scanning, the mouse was awake and had free access to water and food. Next CT acquisition was performed according to selected intervals. The image was reconstructed using of filtered back projection algorithm of Albira Software. For further image processing, PMOD software version 4.2 was chosen. The fantom CT measurements were taken from equilibrium swollen samples in PBS in Eppendorf vial. For preclinical ultrasound imaging, mice were positioned on a 37 °C warmed platform equipped with electrodes. The limbs were carefully placed and secured onto the electrodes, and conductive injectable was applied to enhance the electrical conductivity. Throughout the experiment, physiological parameters ECG and respiration, were continuously monitored via the attached electrodes to ensure stable vital signs during imaging. Ultrasound imaging was conducted using two distinct probes: the MX700 and the MX400 high-frequency ultrasound transducers. These transducers were alternated during the experiment, with the MX400 being used initially and replaced by the MX700 at later stages (after 14 days) to enhance resolution. This change in probes allowed for better adaptation to the evolving conditions of the injected hydrogel (degradation) and surrounding tissue. Ultrasound imaging was performed in 3D B-mode, and the parameters were set according to the specifications detailed in the provided imaging presets: MX700 Probe (transmission frequency: 50 MHz, gain: 30 dB, step size: 0.05 mm, ROI: 1-10 mm, width: 9.73 mm) and MX400 Probe (transmission frequency: 30 MHz, gain: 30 dB, step size: 0.1 mm, ROI: 6-20 mm, width: 15.36 mm). All volumes were evaluated using VEVOLAB ultrasound analysis software. The fantom measurements were taken from equilibrium swollen samples in PBS in Eppendorf vial.

Histopathological examinations

After the in vivo experiment, the 3 mice from each experimental group and 1 control mouse were sacrificed using anaesthesia overdose (diethyl ether) followed by cervical dislocation. Afterwards, their spleen, liver, kidney, and skin samples with adjacent tissues (around scaffold implantation) were collected and fixated with 4% aqueous solution of formaldehyde in phosphate saline buffer (PBS) for 24 h. Next, these samples were embedded in paraffin, and 7 μm sections were prepared using Leica RM2245 semi-automated rotary microtome (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). For each organ, at least 12 slices (usually more) were produced. In skin samples, 5 slices were produced (7 μm each; all 5 slices were places on single microscope glass) and trimmed 210 μm of the sample (which corresponds with 30 slices or 6 more microscope glasses). In such a way, we processed the entire skin sample and produced semi-serial histological sections for further analysis. These slices were stained either with haematoxylin-eosin or Masson´s green trichrome, respectively, dehydrated and covered using DPX mounting medium for histology (Sigma-Aldrich, Prague, Czech Republic). Finally, we evaluated the microscopic structure of organs and presence of scaffold/injectable within the slices. All micrographs were acquired using Leica DM6 B (Leica DM6 B LED Upright light microscope) equipped with K3C (Leica Microscope K3C colour Camera).

ASC seeding

Human ASCs were used for the cell seeding experiments. A 48 well plate was used to seed 100,000 cells through droplet seeding per scaffold (0.5 × 0.5 cm2). The well plate was placed in an incubator at 37 °C and in the presence of 5% CO₂ for 2–3 h to enable the cells to adhere to the scaffolds. After 48 h, the basic culture medium (DMEM, 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin) of the cell-laden hydrogels was replaced with adipogenic differentiation medium (DMEM, 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1 µM dexamethasone, 200 µM indomethacin, 10 µg mL−1 insulin, 0.5 mM IBMX) and incubated at 37 °C in the presence of 5% carbon dioxide (CO2). The adipogenic differentiation medium was refreshed every 2–3 days.

Metabolic activity

Cell proliferation was assessed using an MTS assay kit. The existing cell culture medium was discarded and replaced with 100 µL of fresh medium per well. Then, 20 µL of MTS solution was added to each well, and the plates were incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 1 h and 30 min on a shaker, protected by aluminium foil. After incubation, 100 µL of the supernatant from each well was transferred to a new 96-well plate, and absorbance was measured at 580 nm using a Bio-Tek EL800 spectrophotometer.

Triglyceride assay

To quantitatively assess adipogenic differentiation, a triglyceride assay was conducted. First, the 3D scaffolds were collected into 15 mL Eppendorf tubes, and 0.5–1.0 mL of collagenase IA solution (0.45 PZU mL−1 in cold PBS) was added to dissolve the hydrogel. The tubes were incubated at 37 °C on a shaker until complete dissolution. The resulting mixture was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The remaining cell pellet was counted using a Bürker chamber. The cells were lysed using a 5% Triton X-100/ddH2O solution.

A standard curve was generated by preparing a mixture of triglyceride standards and assay buffer in a 96-well plate (0–10 nmol/well). The cell lysate was added to the same plate, followed by the addition of lipase. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 20 min on a shaker. A reaction mix was then prepared and added to the wells, followed by an additional 60-minute incubation. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a spectrophotometer, and all measurements were performed in triplicate and normalized to the cell count.

Data processing and statistical analysis

At least triplicates were exploited in each experiment unless stated otherwise, and Excel (version 16.86 (24060916), Microsoft Corp., Richmond, WA, USA) build-in functions were utilized to obtain average values and standard deviations. The data were processed in OriginPro 2018 64-bit SR1 b9.5.1.195 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). The schemes and structures were drawn in ChemDraw Professional 16.0.1.4 (77) (Perkin Elmer Informatics, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The graphics were processed in Adobe Illustrator CS6 16.0.0 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) and via BioRender.com. The data from the cytotoxicity study were processed with GraphPad Prism 8, version 9.5.0 (525), and were utilized to perform one-way variation analysis (ANOVA) and student’s t-tests, on the obtained mean ± standard values. Results were considered statistically significant in case p < 0.05. The CT images were reconstructed using a filtered back projection algorithm of Albira Software. For further image and data processing, PMOD software version 4.2 was chosen.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information file. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Djagny, K. B., Wang, Z. & Xu, S. Gelatin: a valuable protein for food and pharmaceutical industries: review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 41, 481–492 (2001).

Gorgieva, S. & Kokol, V. Collagen- vs. Gelatine-Based Biomaterials and Their Biocompatibility: Review and Perspectives. Biomaterials Applications for Nanomedicine. 17–52 https://doi.org/10.5772/24118 (2011).

Van Hoorick, J. et al. Cross-linkable gelatins with superior mechanical properties through carboxylic acid modification: increasing the two-photon polymerization potential. Biomacromolecules 18, 3260–3272 (2017).

Peirsman, A. et al. Vascularized adipose tissue engineering: moving towards soft tissue reconstruction. Biofabrication 15, 1–35 (2023).

Van Nieuwenhove, I. et al. Soft tissue fillers for adipose tissue regeneration: from hydrogel development toward clinical applications. Acta Biomater. 63, 37–49 (2017).

Menke, H., Grübmeyer, H., Biemer, E. & Olbrisch, R. R. PVP breast implants after two years: initial results of a prospective study. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 25, 278–282 (2001).

Aktouf, A., Auquit-Auckbur, I., Coquerel-Beghin, D., Delpierre, V. & Milliez, P. Y. Augmentation Mammaire Par Prothèses En Gel de Silicone de La Marque Poly Implant Prothèses (PIP): Étude Rétrospective de 99 Patientes. Analyse Des Ruptures et Prise En Charge. Annal. Chirurg Plastiq Esthet. 57, 558–566 (2012).

McGrath, M. H. & Burkhardt, B. R. The safety and efficacy of breast implants for augmentation mammaplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 74, 550–560 (1984).

Blondeel, P. N. One hundred free DIEP flap breast reconstructions: a personal experience. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 52, 104–111 (1999).

Appel, A. A., Anastasio, M. A., Larson, J. C. & Brey, E. M. Imaging challenges in biomaterials and tissue engineering. Biomaterials 34, 6615–6630 (2013).

Nam, S. Y., Ricles, L. M., Suggs, L. J. & Emelianov, S. Y. Imaging strategies for tissue engineering applications. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 21, 88–102 (2014).

Hetterich, H. et al. Phase-contrast CT: qualitative and quantitative evaluation of atherosclerotic carotid artery plaque. Radiology 271, 870–878 (2014).

Lin, C.-Y. et al. Augmented healing of critical-size calvarial defects by baculovirus-engineered MSCs that persistently express growth factors. Biomaterials 33, 3682–3692 (2012).

Tondera, C. et al. Gelatin-based hydrogel degradation and tissue interaction in vivo: insights from multimodal preclinical imaging in immunocompetent nude mice. Theranostics 6, 2114–2128 (2016).

Patterson, J. et al. Hyaluronic acid hydrogels with controlled degradation properties for oriented bone regeneration. Biomaterials 31, 6772–6781 (2010).

Kim, S. H. et al. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging for noninvasive trafficking of scaffold degradation. Sci. Rep. 3, 1198 (2013).

Gudur, M. S. R. et al. Noninvasive quantification of in vitro osteoblastic differentiation in 3D engineered tissue constructs using spectral ultrasound imaging. PLoS ONE 9, e85749 (2014).

Colomb, J., Louie, K., Massia, S. P. & Bennett, K. M. Self-degrading, MRI-detectable hydrogel sensors with picomolar target sensitivity. Magn. Reson. Med. 64, 1792–1799 (2010).

Berdichevski, A., Shachaf, Y., Wechsler, R. & Seliktar, D. Protein composition alters in vivo resorption of PEG-based hydrogels as monitored by contrast-enhanced MRI. Biomaterials 42, 1–10 (2015).

Liu, J. et al. Visualization of in situ hydrogels by MRI in vivo. J. Mater. Chem. B 4, 1343–1353 (2016).

Kolouchova, K. et al. 19F MRI In Vivo Monitoring of Gelatin-Based Hydrogels: 3D scaffolds with tunable biodegradation toward regenerative medicine. Chem. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.3c03321 (2024)

Kolouchova, K. et al. Thermoresponsive triblock copolymers as widely applicable 19F magnetic resonance imaging tracers. Chem. Mater. 34, 10902–10916 (2022).

Sharma, U., Chang, E. W. & Yun, S. H. Long-wavelength optical coherence tomography at 1.7 Μm for enhanced imaging depth. Opt. Express 16, 19712–19723 (2008).

Crosignani, V. et al. Deep tissue fluorescence imaging and in vivo biological applications. J. Biomed. Opt. 17, 116023 (2012).

Wang, C. et al. An injectable double-crosslinking iodinated composite hydrogel as a potential radioprotective spacer with durable imaging function. J. Mater. Chem. B 9, 3346–3356 (2021).

Cheheltani, R. et al. Tunable, biodegradable gold nanoparticles as contrast agents for computed tomography and photoacoustic imaging. Biomaterials 102, 87–97 (2016).

Le, N. A., Kuo, W., Müller, B., Kurtcuoglu, V. & Spingler, B. Crosslinkable polymeric contrast agent for high-resolution X-ray imaging of the vascular system. Chem. Commun. 56, 5885–5888 (2020).

Celikkin, N., Mastrogiacomo, S., Walboomers, X. F. & Swieszkowski, W. Enhancing X-ray attenuation of 3D printed gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) hydrogels utilizing gold nanoparticles for bone tissue engineering applications. Polymers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11020367 (2019).

Sani, A., Cao, C. & Cui, D. Toxicity of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs): a review. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 26, 100991 (2021).

Groborz, O. et al. Photoprintable radiopaque hydrogels for regenerative medicine. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2, 811–817 (2024).

Guimarães, C. F., Gasperini, L., Marques, A. P. & Reis, R. L. The stiffness of living tissues and its implications for tissue engineering. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 351–370 (2020).

Van Damme, L., Blondeel, P. & Van Vlierberghe, S. Injectable biomaterials as minimal invasive strategy towards soft tissue regeneration—an overview. J. Phys. 4, 022001 (2021).

Van Damme, L., Briant, E., Blondeel, P. & Van Vlierberghe, S. Indirect versus direct 3D printing of hydrogel scaffolds for adipose tissue regeneration Lana Van Damme, Emilie Briant, Phillip Blondeel, Sandra Van Vlierberghe. MRS Adv. 5, 855–864 (2020).

Tytgat, L. et al. Evaluation of 3D printed gelatin-based scaffolds with varying pore size for MSC-based adipose tissue engineering. Macromol. Biosci. 20, 1900364 (2020).

Huri, P. Y., Arda Ozilgen, B., Hutton, D. L. & Grayson, W. L. Scaffold pore size modulates in vitro osteogenesis of human adipose-derived stem/stromal cells. Biomed. Mater. 9, 045003 (2014).

Aras, M. H. et al. Comparison of the sensitivity for detecting foreign bodies among conventional plain radiography, computed tomography and ultrasonography. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 39, 72–78 (2010).

Eggers, G. et al. X-ray–based volumetric imaging of foreign bodies: a comparison of computed tomography and digital volume tomography. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 65, 1880–1885 (2007).

De Maeseneer, T. et al. Powdered cross-linked gelatin methacryloyl as an injectable hydrogel for adipose tissue engineering. Gels 10, 167 (2024).

Xiang, L. & Cui, W. Biomedical application of photo-crosslinked gelatin hydrogels. J. Leather Sci. Eng. 3, 3 (2021).

Kim, S. H. & Jung, Y. 3—Resorbable polymers for medical applications. In Biotextiles as Medical Implants. (eds King, M. W., Gupta, B. S., Guidoin, R.) (Woodhead Publishing, 2013) https://doi.org/10.1533/9780857095602.1.91 pp 91–112.

Von Heimburg, D. et al. Preadipocyte-loaded collagen scaffolds with enlarged pore size for improved soft tissue engineering. Int. J. Artif. Organs 26, 1064–1076 (2003).

Kolouchova, K. et al. Cell-interactive gelatin-based 19F MRI tracers: an in vitro proof-of-concept study. Chem. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.3c01574 (2023).

Markovic, M. et al. Hybrid tissue engineering scaffolds by combination of three-dimensional printing and cell photoencapsulation. J. Nanotechnol. Eng. Med. 6, 210011–210017 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the core facility Center for Advanced Preclinical Imaging, Charles University, supported by the MEYS CR (LM2023050 Czech-BioImaging, and LUAUS24203), by Charles University grant SVV 260635/2024, by European Regional Development Fund (Project No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/18_046/0016045), and by European Regional Development Fund (Project No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_013/0001775). K.K. gratefully acknowledges the financial support provided by Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO, Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek—Vlaanderen, project no. 1229422N and 1247425N). L. Van Damme would also like to acknowledge the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) for providing her with an FWO-SB fellowship. OG and KK gratefully acknowledge the co-funding of this project with Grant Agency of Charles University (GA UK), project No. 199125. The study was also supported by project New Technologies for Translational Research in Pharmaceutical Sciences/NETPHARM, project ID CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004607, co-founded by the European Union. The Institute of Histology and Embryology (First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University) would like to acknowledge the support of the COOPERATIO Program of Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic (207036-10 Morphological Disciplines of Medicine/LF1). The authors acknowledge Euro-BioImaging (www.eurobioimaging.eu) for providing access to imaging technologies and services via The Center for Advanced Preclinical Imaging (CAPI) (Prague, Czechia) and funding via the COMULISglobe project supported by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. At last, we thank the NMR expertise center (Ghent University) for providing support and access to its NMR infrastructure. The 500 MHz used in this work has been funded by a grant of the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) (project number FWO I006920N). Some graphics were created using Biorender.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.K.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft; J.H.: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing; P.M.: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing; N.R.: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology; L.V.D.: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing; M.Ho: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing; Z.P.: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing; L.D.: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing; K.S.: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing; J.Z.: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing; J.K.: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources; MHr: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review & editing; OG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing; L.S.: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review & editing; S.V.V.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Sandra Van Vlierberghe and Lana Van Damme are co-founder of 4Tissue BV, while Sandra Van Vlierberghe is also co-founder of BIO INX BV, but the authors declare to have no known financial interest that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The remaining authors declare no competing interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Shuntaro Uenuma, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Daniela Loessner and Jet-Sing Lee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kolouchova, K., Humajova, J., Matous, P. et al. Non-destructive in vivo tracking of gelatin hydrogels for advancing tissue engineering. Commun Mater 6, 112 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00830-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00830-2

This article is cited by

-

Microcrystallization-gelation enabled mechanocompatible and antibacterial hydrogels for cartilage repair

Science China Materials (2026)