Abstract

The experimentally validated real-time time-dependent density-functional theory (rt-TDDFT) provides a robust framework for studying electronic stopping. Accurate predictions of this directionally sensitive phenomenon are essential for various active research areas and applications, especially in semiconductors. Here we present a path-dependent model of electronic stopping in self-irradiated silicon in the keV-MeV regime. We find a linear relationship between electronic stopping and the mean electron density using rt-TDDFT calculations, performed with the Qball code, along six channels and three incommensurate trajectories. Using this, the model predicts electronic stopping as a function of the local ground-state electron density and the projectile velocity Se(v, ρ). Our model accurately describes the electronic energy losses along any trajectory, from channels to regions of higher electron density, including the random trajectories measured experimentally. In addition, we provide a comprehensive overview of rt-TDDFT calculations of electronic stopping in self-irradiated silicon, including a detailed description of the requirements of pseudopotentials in all kinematic regimes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Materials under irradiation are a topic of interest in many areas of physics and engineering: from experiments in astrophysics, nuclear and high-energy physics, which depend on the performance of materials under high irradiation conditions1; to the development of radiation-resistant materials for nuclear fusion reactors2, and improved shielding for nuclear sources, nuclear power plants, and other facilities3; not to mention the possible technological and industrial applications of well-characterized materials under radiation-intensive conditions. For any radiation-intensive environment, accurate predictions of radiation effects in semiconductor materials are critical, especially for silicon crystals4 due to their wide use in detectors and electronic components in general.

Characterizing the path-dependent effects of projectiles in silicon is relevant in several applications. For example, experiments and simulations have shown that projectiles traveling along particular directions in a pristine material experience significantly less energy losses to electronic stopping than for random trajectories5,6. Such directions, known as channels, are paths where the distance of closest approach to host atoms, or the impact parameter, is maximized. This fact has been widely used in the industry, where ion implantation via ion beams allows doping silicon in a quick, controllable, and cost-effective way7. The purpose of this technique is to either achieve or prevent channeling effects, to implant dopants at certain distances, taking into account the damage build-up on the sample8. Channeling is also closely related to the energy resolution of high-energy silicon detectors9, and it can be used to distinguish between different particle species with the same momentum10. Moreover, a characterization of silicon projectiles in silicon, also referred to as self-irradiated silicon, is valuable for radiation damage predictions. The processes of collision cascades, defect formation, and their later recombination all depend on the partitioning of the incident ion energy11.

The behavior of self-irradiated silicon can be analyzed in terms of ion-solid interactions. Such interactions have been widely studied within the Born-Oppenheimer approximation12, in which the ionic and electron systems are decoupled. With this approach, the ion-matter interactions have been computationally modeled and studied with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, under the assumption that electrons are always in their ground state13. On the other hand, interactions of energetic projectiles with the electrons of the host material have been calculated with several methods, including the real-time time-dependent density-functional theory (rt-TDDFT) framework14. This framework can be used to calculate the electronic stopping by describing the evolution of the electronic system as a projectile travels through the material, and such predictions agree with experimental results15. The Ehrenfest approximation16 is used to include the non-adiabatic interactions between quantum mechanical electrons and classical ions in the time-dependent simulations. It is known that this formalism fails to achieve thermal equilibrium between electrons and ions, which can be properly addressed by introducing quantum fluctuations in the ionic trajectories, giving the ions a quantum nature17. While these fluctuations in the ions are not tractable within the Ehrenfest approximation, the formalism effectively models the energy exchange from ions to electrons. Since the interaction between electrons and the incident particles governs the dissipation process in the high-energy range, we employ rt-TDDFT to fit a path-dependent electronic stopping model for self-irradiated silicon in the metallic regime (keV) and up to the Bragg peak (MeV regime).

Experimental and numerical studies of the self-irradiated silicon system have been carried out in selected directions and kinematic regions. Most of the experimental data for electronic stopping in self-irradiated silicon is for random directions18. A notable exception is found in the measurements by Lohmann et al.19 in the keV regime, which showed the directional dependency of the electronic energy losses. Their study collected data along the 〈001〉 direction, which showed up to 75 % less energy losses per distance traveled compared to random directions for the same projectile kinetic energy. Additionally, a previous measurement along the 〈110〉 direction6 showed even lower energy losses for 0.3 MeV projectiles. Computationally, the widely used SRIM (Stopping and Range of Ions in Matter) model20 predicts electronic stopping as a function of projectile energy for the silicon system. However, the model was fitted to the random direction experiments. Thus, it is unable to capture the observed trajectory dependence. Within the rt-TDDFT scope, the self-irradiation of silicon was first studied for ions with kinetic energies ranging from 1 eV to 0.8 MeV along the 〈001〉 channel21. The silicon atoms were simulated using pseudopotentials with four explicit electrons to account for the valence states. A subsequent study extended the range of kinetic energies to 50 MeV for the 〈001〉, 〈110〉, and 〈111〉 channels, also considering completely ionized silicon projectiles22 and their respective equilibrium charges at relativistic kinetic energies. The calculations were performed in the relativistic regime using a pseudopotential with twelve explicit electrons, representing the valence orbitals and most of the core states. Additionally, based on data obtained with a four-electron Si pseudopotential, Jarrin et al.23 implemented the ion-electron coupling in a two-temperature molecular dynamics framework24,25 for simulations of radiation-induced collision cascades in Si, where the losses to the electronic system were determined with rt-TDDFT simulations for energies ranging from 10 keV to 200 keV. The contrasting pseudopotential settings for the aforementioned kinematic regions and trajectories illustrate the need for a comprehensive picture of the pseudopotential requirements of this system. This will allow to calculate the path-dependent electronic losses along any trajectory and energy within rt-TDDFT accuracy.

The accuracy of computations using different numbers of explicit electrons has been studied for a range of projectile-material combinations. For the nickel system, electronic stopping was studied along the 〈111〉 channel with different numbers of explicit electrons for both projectile and host atoms, in the velocity range from 1 a.u. to 12 a.u. The results showed that a projectile with 26 explicit electrons in a target material with 18 explicit electrons for the lattice atoms provides a more complete picture of the dissipation pathways and hence a more accurate prediction of the electronic stopping compared to calculations using only 10 explicit electrons for both target atoms and projectile26. Therefore, the inclusion of explicit core states in channeling trajectories was necessary to describe this process fully, at least in the high velocity ranges. Nevertheless, adding extra explicit electrons to the calculations is computationally heavy and does not necessarily improve the results. For self-irradiated tungsten, previous calculations found that the inclusion of core states deeper than the 5p orbitals in the projectile traveling along the 〈001〉 channel did not significantly change the electronic stopping values in the velocity regime of 0.5 to 1 a.u.27. For smaller impact parameters, however, simulations of hydrogen projectiles in aluminum have shown that core electrons are critical to electronic stopping calculations in off-center trajectories at high energies28.

In the present work, we propose a model for self-irradiated silicon that, despite the underlying complexity of the local energy dissipation, successfully estimates electronic stopping based on a single-valued function of electron density, and we demonstrate the model’s validity for arbitrary trajectories. In addition, we elucidate the regions depending on particle velocity and impact parameter where different pseudopotentials, i.e., explicit numbers of electrons, are needed to give accurate results over the full range of projectile energies (eV-MeV). The paper is organized as follows. First, in the “Results and discussion” section, we present the calculated electronic stopping obtained with rt-TDDFT for different channels, comparing different exchange-correlation functionals as well as different formalisms for pseudopotentials. We then present a comprehensive study of the involvement of core electrons in the dissipation for a wide range of projectile velocities and impact parameters. Following this, we propose a model that captures the electronic stopping as a function of the local electronic density of any trajectory, and compare the predictions of the model with those obtained with the SRIM package. We conclude with a discussion of our results. Finally, we describe the methods used for the rt-TDDFT calculations.

Results and discussion

Time-dependent density-functional theory was used to calculate the electronic stopping power of self-irradiated silicon, using pseudopotentials with 4 (Si4) and 12 (Si12) explicit electrons, as described in the “Methods” section.

Electronic stopping calculations

We first explore the consistency of predictions between the multiple available Si pseudopotentials for electronic stopping calculations. For this purpose, simulations with a 1 keV projectile along the 〈001〉 direction were performed using the following Si4 pseudopotentials: Optimized RRKJ29 built with OPIUM30 for the adiabatic local density approximation (LDA) functional31, Optimized Norm-Conserving Vanderbilt (ONCV)32 for the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional33 by Schlipf et al.34, Hamann-Schlueter-Chiang-Vanderbilt (HSCV) LDA31, and U. von Barth and R. Car (PZ-VBC) LDA35. The latter was one of the first pseudopotentials developed for Si. Figure 1 shows the results of this comparison. It can be seen that the electronic losses are fairly equal for all cases, where approximately 1% differences are found among the values, with the particular exception of the OPIUM pseudopotential. For the purpose of this investigation, the OPIUM pseudopotential was purposefully built with a large convergence error per electron of about 0.5 eV, when it normally could be optimized to values less than 15 meV per electron. Even so, the computed value with this pseudopotential differs by less than 6% from the others. Concerning the exchange-correlation choice, it is a widely recognized issue that both LDA and PBE underestimate electronic band gaps. However, it has been demonstrated for the LDA case that this limitation has minimal impact on electronic stopping for silicon projectiles with kinetic energies above 3 keV21. For this reason, Fig. 1 also shows calculations with the HSCV LDA and the ONCV PBE pseudopotentials, from 1 keV to 100 keV projectile energies, and along the 〈001〉 channel. In all cases, the variations are less than 3%, indicating that both functionals yield similar results. Our findings support similar observations in silicon23, and are also consistent with a recent work showing this for proton projectiles in aluminum36. However, protons and alpha projectiles in silicon carbide have shown a high dependence on the exchange-correlation choice in regions around the stopping peak37. Hence, additional investigation is needed to assess the changing behavior across various energy domains.

The resulting electronic stopping values, represented by the slope of these curves, vary by about 1%, except for the OPIUM potential30, which deviates by only 6%. This is particularly noteworthy as the OPIUM potential was purposefully built with a large convergence error. A small vertical offset between the energy curves at the origin has been added for visualization purposes. The inset shows the percentage deviation between the electronic stopping power predicted by the ONCV PBE34 and HSCV LDA31 potentials for a range of projectile energies. The deviations are less than 3%.

An additional concern arises from the fact that each pseudopotential predicts a different relaxed lattice constant: The HSCV Si4 potential gives a 5.39 Å lattice constant, the ONCV Si4 potential gives a 5.49 Å lattice constant, and the ONCV Si12 gives a 5.44 Å lattice constant, while the experimental value is 5.431 Å38. To test the fidelity of the electronic stopping calculations with respect to the lattice constant, simulations for 10 keV projectiles were carried out in systems with both the relaxed lattice constants and the experimental lattice parameter value. The electronic stopping values of the two scenarios were found to differ by less than 1%, indicating that the choice of pseudopotential and imposing the experimental lattice constant does not significantly impact the outcomes in this energy range. Considering that the optimization algorithm for the generation of ONCV pseudopotentials by Schlipf et al.34 includes tested and ready-to-use parameters for Silicon with the PBE correlation functional, we have used Si4 and Si12 ONCV PBE pseudopotentials for all subsequent calculations.

In general, pseudopotentials with a large number of explicit electrons are computationally expensive to use. While including explicit core electrons for all atoms could be expected to produce more accurate results, a compromise between accuracy and computational expense is necessary. To ascertain where augmented-core pseudopotentials are needed in the Si system, we explored two different calculation setups. In the first set-up, all atoms were represented with Si12, and in the other, Si12 was used only for the projectile and its first nearest neighbors along the trajectory, while Si4 was used for the remaining atoms. The electronic stopping differences between the two systems were less than 0.1% for all cases tested, which consisted of 50, 100, 200, and 500 keV projectiles along the 〈110〉 off-centered channel. Hence, populating the lattice further away from the projectile trajectory with less computationally demanding pseudopotentials achieves approximately the same results.

Figure 2 shows the results for electronic stopping of self-irradiated silicon in the 〈001〉 channel, compared to previous rt-TDDFT calculations in the eV-keV21 and the keV-MeV22 regimes. The predictions of the software package SRIM20 and experimental data measured for random trajectories18 and for the channels 〈001〉19 and 〈110〉6 are also shown. For projectile kinetic energies around 500 keV, the Si4 projectile fails to reproduce the electronic stopping portrayed by experiments. Lee et al.22 performed calculations with Si12 in this velocity region. These simulations and the ones presented here with a Si12 pseudopotential for the projectile, compensate the saturation observed for electronic stopping at the keV-MeV range, meaning that the projectile core electrons play a relevant role in the electronic stopping at these energies. For larger energies, we have performed the same computations with Si12 projectiles, with both Si4 and Si12 as the target atoms. The two systems show the same electronic stopping up to a 10 MeV projectile energy. Beyond this energy, the system with Si4 host atoms shows smaller energy losses, suggesting that the core electrons of the host material are also involved. These tests allowed us to identify the different pseudopotential settings to describe the energy losses along this direction and energy ranges within the accuracy of the rt-TDDFT technique.

The 〈001〉 channel tests allowed us to identify suitable pseudopotential settings to explore the other dominant channeling directions in the diamond Si structure. Figure 3 shows the electronic stopping values for the five selected channels in the keV-MeV range. The 〈110〉 channel direction has the lowest values for the stopping power, followed by the 〈112〉 direction; the 〈001〉 and 〈321〉 channels have consistently similar values. The half-centered 〈111〉 channel shown here is an alternate symmetric trajectory in the 〈111〉 direction that explores a wider range of atomic neighborhoods than the 〈111〉 centered channel, which crosses neighborhoods similar to 〈001〉 and 〈112〉. An illustration of this trajectory is shown in the “Methods” section. The half-centered 〈111〉 channel exhibits the highest electronic energy losses among all. For all trajectories, the electronic stopping is linear with velocity for energies between 10 keV and 200 keV. Lim et al.21 observed the onset of this linear behavior at 3 keV for the 〈001〉 channel. Our results confirm this, and additionally show that this transition occurs at different energies for different channels. This is expected because varying impact parameters can affect the excitation or transitions between orbitals differently, and these transitions affect the energy loss mechanism present at these channeling projectile energies. In addition, the 〈110〉 off-centered channel is thoroughly studied here as it portrays a small impact parameter path. As such, it can be expected to yield a higher stopping power than the average trajectories captured by the SRIM model. For this trajectory, simulations for target atoms with Si4 and Si12 showed different electronic stopping values in all the energy regimes studied. For example, the electronic stopping values at 10 keV were 5.635 eV/Å and 7.000 eV/Å for the Si4 and Si12 projectiles, respectively, which amounts to a 20% difference. Also, including a Si12 projectile in the Si4 system corrects the underestimation of the electronic losses above the 500 keV region, as previously seen for the 〈001〉 channel; however, that was not enough to provide the same results as in the Si12 in Si12 system. These calculations demonstrate that target core electrons play a key role in interactions at short distances, even at low energies. In the following, we provide a closer examination of the evolution of electronic states to fully explain the varying pseudopotential requirements observed so far.

Several channels are presented, including an off-centered trajectory. The channeling projectiles with energies higher than 200 keV required a Si12 pseudopotential. The off-centered trajectory shows how the lack of explicit electrons in the projectile or the target atoms underestimates electronic stopping.

The comparison of SRIM data and our calculated results reveals differences between electronic stopping regimes. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the linear or metallic regime of electronic stopping (≤200 keV in our data) and the Bragg peak region (≥1 MeV). It can be seen that around this transition region, SRIM behavior deviates from the calculated data. This exotic velocity dependence has been previously described for several ion-target combinations39. These deviations are mainly due to artificially extending SRIM’s validity range to velocities below the Bragg peak. Therefore, caution should be exercised when using SRIM for predictions in these low-velocity regions.

Si pseudopotential needs

With the rt-TDDFT approach, it is possible to examine the evolution of the Kohn-Sham states. It is well known that the Kohn-Sham states do not correspond to the true eigenstates of the system’s physical Hamiltonian. However, in some cases, agreement has been found between the ground-state Kohn-Sham eigenvalue differences and the experimental excitation energies40. For the silicon system, we observe how certain Kohn-Sham states resemble the projectile orbital states. Therefore, their evolution can provide insight into the regions where the core electrons are needed to give an accurate description of the energy losses. The energy expectation values of the Kohn-Sham states for two contrasting cases are shown in Fig. 4.

Top: 〈001〉 Si12 vs Si12 for 200 keV, 500 keV and 20 MeV projectiles. For the 200 keV case, no significant deviations are observed for the core states expectation values. Nevertheless, for the 500 keV case, the 2p states of the projectiles start to get excited, and at the 20 MeV regime, the target core states are also excited. Bottom: 〈110〉 off-channel trajectory for a 50 keV projectile. The oscillating expectation values for only the Si12 projectile or target show the need for explicit core states in trajectories with low-impact parameters. For the case where both target and projectile included core states, the interaction between those inner orbitals resulted in a much wider and oscillating set of expectation values.

The energy expectation values for 200 keV, 500 keV, and 20 MeV projectiles along the 〈001〉 channel are shown in Fig. 4. The 200 keV case shows that the 2p and 2s orbitals are approximately stable throughout the simulation. In contrast, for the 500 keV case, one of the 2p projectile states is excited. These excited orbitals are not present in the Si4 projectile, and for this reason, the simulations with only Si4 pseudopotentials are no longer accurate at these energies. For the 20 MeV case, the three 2p projectile core states are excited to the valence level, and the 2s orbital is constantly excited to the 2p level. Further, we see that the 2s and 2p orbitals of the target atoms are excited as a function of the projectile position. For these reasons, both projectile and host atoms require the Si12 pseudo to fully describe the electronic loss process beyond this energy. The orbitals excited to the valence band represent an ionization process of the projectile, which is consistent with the fact that a 20 MeV energy is on the stopping peak. For larger energies, the electronic stopping decreases as the projectile is ionized and reaches an equilibrium charge where the remaining projectile electrons interact less with the target electrons. Our observations are in agreement with previous calculations of the equilibrium projectile charge state for self-irradiated silicon22 using the DDEC6 method41, which extracts the ion charges from time-dependent electron densities. It is noteworthy that for the 20 MeV projectile in Fig. 4, we have only displayed the initial portion of the trajectory. This captures the system’s transient state and a region where the ionization process is taking place. To obtain a representative region of the asymptotic electronic stopping power process, larger cells were required for these high-energy systems, as described in “Methods.”

Different combinations of pseudopotentials for target atoms and 50 keV projectiles in the 〈110〉 off-centered channel are also shown in Fig. 4. The Si12 in Si4 case shows how the projectile core states are perturbed as they travel along the material. Similarly, a Si4 in Si12 system shows how the projectile valence orbitals perturb the target core states. The last case shows how the core states of both projectile and target interact to produce larger perturbations, accompanied by an observable excitation of the 3p+3s states. Since this energy loss mechanism is absent in the first two cases, this explains the consistently higher values of electronic stopping for Si12 in Si12 in this channel.

Figure 5 summarizes the pseudopotential requirements for the electronic stopping calculation in silicon, considering the kinetic energy and the closest approach distance of the projectile to the host atoms. The y-axis indicates the closest approach distances for different channeling and off-centered channel trajectories. Since the interaction of core electrons depends on the distance between atoms, it is necessary to estimate the minimum possible distances for a given energy. We used the ZBL potential42 to define the forbidden region where atoms cannot approach any closer, which is particularly critical at low kinetic energies.

The projectile kinetic energy and distance of closest approach to target atoms determine whether the projectile, the targets, or both require explicit core electrons. The ZBL repulsive potential provides a constraint on the minimum distance of approach for a projectile with a given kinetic energy. The closest approach distance for different channeling and off-channeling trajectories is shown along the y-axis.

Path-dependent electronic stopping

As can be seen in Fig. 3, the electronic stopping for a given energy depends on the trajectory. In addition, previous works22,23 have observed differences between projectile trajectories and the local electron density along them. Therefore, we examine the electron densities to understand the energy losses calculated in each trajectory. Figure 6 shows the ground-state electron density in the projectile trajectory for the different channels studied, and their respective average value along a periodic trajectory. Some channels, such as 〈110〉 and 〈001〉, explore a narrow set of density values, while channels such as 〈321〉 and the half-centered 〈111〉 experience a wider range of densities. In the 〈110〉 off-centered channel trajectory, we see an underestimation of the density generated by the Si4 atoms, which lack the core states, as compared to the Si12 atoms. Considering also the underestimation of the electronic stopping for this trajectory, it suggests a relationship between the computed electron density along the path and the calculated electronic stopping. Nonetheless, as a conclusion for all the trajectories studied, it is notable that each one exhibits a distinctive electron density.

The difference between the electronic stopping along the periodic trajectories can be studied by their averaged electron density. Caro et al.24,43 have shown that the instantaneous electronic stopping is not a single function of the local electron density, which is also the case in our calculations. However, Fig. 3 indicates that the electronic stopping consistently increases for channels exploring higher density regions. Indeed, we find that the electronic stopping is linearly correlated with the average electron density for several projectile energies, as illustrated in Fig. 6. In addition to the fully centered channels, we have included the Si4 〈110〉 off-centered channel, as it shows different density and stopping values compared to the Si12 case. This approach to electronic stopping as a function of mean electron density \({S}_{e}(\bar{\rho })\) is consistent with the definition of stopping power as the energy loss per unit path length, here calculated as the energy loss over a periodic path length.

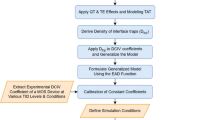

Since the electronic stopping power is a function of the projectile velocity v and a linear function of the mean local electron density on the path \(\bar{\rho }\), we fit a model for electronic losses as \({S}_{e}(v,\bar{\rho })=f(v)\cdot (\bar{\rho }+{\rho }_{0})\), with ρ0 as a constant to be determined. Now, it is possible to relate \({S}_{e}(v,\bar{\rho })\) to the local density ρ on a point-by-point basis instead of using \(\bar{\rho }\) along a trajectory, using the mean density as \(\bar{\rho }=\frac{\mathop{\sum }_{i}^{n}{\rho }_{i}}{n}\), the sum of n density values ρi:

which can be interpreted as the average instantaneous electronic stopping calculated point by point along a trajectory. Therefore, a function that captures Se as a function of \(\bar{\rho }\) can be used equivalently to calculate the instantaneous energy loss. The following piecewise Se(v, ρ) function captures our findings for projectiles in the 5 keV - 5 MeV regime:

With \({S}_{e}(v,\bar{\rho })\) in eV/Å, with v and \(\bar{\rho }\) in a.u., the parameter values (here listed unitless) are: a1 = 889 ± 53, ρ1 = 0.016 ± 0.003, a2 = 951 ± 187, a3 = 0.06 ± 0.03, and ρ2 = 0.075 ± 0.005. Here, v1 = 0.5358 a.u. and v2 = 1.198 a.u. define the boundaries between the metallic linear regime (≤200 keV) and the peak region (1 MeV≤) respectively. The function adjusting the peak (v ≥ v2) is purely empirical, based on similar fits44. It consists of a linear component to match the trend in the lower energetic linear regime Slow ∝ v, and a weighted logarithmic dependence for high energies, \({S}_{high}\propto \log (v)/v\), similar to Bethe’s stopping formula45. The two parts are then combined as weighted harmonic contributions 1/Se = 1/Slow + 1/Shigh. The transition region v1 < v < v2 was modeled with a quadratic function of velocity. The boundary points of this function at v1 and v2 can be smoothed with a sigmoid function or other methods to ensure continuity. Nevertheless, the presented approach was enough to test its accuracy.

Figure 7a shows the prediction of the Se(v, ρ) model (eq. (1)) compared to all our rt-TDDFT calculations, with the relative deviation from the rt-TDDFT data illustrated in Fig. 7b. The model deviation is between ±10% for most of the calculated trajectories, with the highest deviation calculated being below 60%. Importantly, the model outperforms SRIM predictions, which can show deviations up to 500%. These significant discrepancies occur at low energies and along low-density channels. As noted in ref. 39, the SRIM estimates of electronic stopping are unpredictable and often misleading below the Bragg peak. Besides, low-density channels exhibit lower energy losses compared to random directions, which SRIM aims to represent. Additionally, eq. (1) can also estimate a mean density for both SRIM and experimental data from random trajectories. Such densities can be determined by inserting the Se and v values into eq. (1), and are shown in Fig. 7a. This shows that the experimental data for random trajectories and the SRIM values shown are consistent with a high-density region, though not as high as the incommensurate path #3, which explores collision-like densities, but far from the channeling-like densities. Figure 7a also includes data below 5 keV, which is a region that is no longer linear to the velocity, but where the predictions of the model are still accurate.

a rt-TDDFT electronic stopping values compared with the model predictions (eq. (1)). b Projectile velocity vs mean electron density: the colormap shows the model values, and the size of the circle indicates the SRIM deviation from TDDFT.

Figure 7b shows both rt-TDDFT data that was used to fit the model parameters, and independent calculations used to test the model. For this test data, instead of using the average electron density over a path \(\bar{\rho }\), we used the equation (1) with electron density ρ pointwise to estimate instantaneous electronic stopping along the trajectories. Figure 8 shows the results for three cases. First, a 2 MeV projectile along the 〈321〉 channel, which periodically explores a wide range of densities, including low densities such as 4.59 × 10−3 a.u., comparable to vacancy levels. Next, a 20 keV projectile along the incommensurate path #2, as described in “Methods,” explores a broader low-density region in the 10−3 a.u. range. Finally, a 50 keV projectile along the incommensurate path #3, which describes a close approach with a host atom, with a closest approach distance of 0.4 Å. In this region, the model portrays a single peak, inherited from the electron density as it approaches the target atom. However, TDDFT shows two peaks due to the instantaneous electronic stopping’s sensitivity to changes in the density gradient during the in and out parts of the motion. Nonetheless, the net contributions from both the model and TDDFT are comparable, as evidenced by the small deviation error obtained. In general, for all the rt-TDDFT data, we have found that the Se(v, ρ) function (eq. (1)) used on a point-by-point basis gives very accurate results.

The electronic excitation energy (EEE) measures the overall energy dissipated to the electrons, and its slope represents the electronic stopping power. a 2 MeV projectile along a periodic path on the 〈321〉 channel, b 200 keV projectile along the incommensurate path #2, and c 50 keV projectile along the incommensurate path #3. The “fitted” EEE corresponds to the cumulative path-integrated Se(v, ρ). The model does not match the rt-TDDFT instantaneous electron stopping point-by-point, but it provides accurate energy loss values.

The model allows us to explore the experimentally measured random trajectories as representations of a well-defined region on the mean electron density domain. If we consider a straight trajectory within the 10−2 a.u. mean density range or higher, such as the incommensurate path #3 shown in Figs. 7 and 8, it will involve multiple encounters with lattice atoms at distances of 0.4 Å or less. Under these conditions, projectiles are more likely to be scattered or deflected and, therefore, would not be detected in an experiment where the detector is aligned with the ion beam. On the other hand, lower mean density values are discarded experimentally. To measure random directions in a pristine crystal, the target is rotated to avoid aligning a low-index channel or plane with the beam19, meaning that any high transmission region around the beam can be understood as a channeling process. For these reasons, the experimentally measured random trajectories seem to be bound to a specific mean density range. Furthermore, since the 〈110〉 off-centered channel covers the same density region as the experimentally measured random trajectories, it provides an optimal pseudo-random rt-TDDFT direction for studying the energy dissipation along experimental random trajectories.

The model is formulated from data gathered in a pristine cell. However, calculations along incommensurate trajectories show that the model can predict correct electronic stopping values over a reasonably long trajectory exploring a range of impact parameters, regardless of local electronic stopping variations. Therefore, the model is expected to also apply to conditions in which the structure has been slightly perturbed. It is also worth mentioning that the empirical relationship between the stopping power and the mean electron density was derived from the analysis of the data. Hence, we expect a similar correlation to be found in other semiconductors and/or diamond-structured materials with similar band structures.

In conclusion, we have developed a model for electronic stopping power in self-irradiated silicon that depends on the local ground-state electron density and projectile velocity. The model covers the keV-MeV regime and is based on rt-TDDFT calculations along six channels and three incommensurate paths. We explored a wide range of densities, from vacancy-like regions to close encounters with nuclei. The predictions of the model are in good agreement with independent rt-TDDFT data, demonstrating its accuracy and improvement upon current electronic loss estimation methods such as SRIM. The study of several channeling trajectories enabled us to explore their differences in terms of the electron density neighborhoods that the projectile penetrates. This revealed a linear relationship between electronic stopping and the mean electron density. Consequently, we showed that a single-valued function between the rt-TDDFT instantaneous electronic stopping with the local density is not necessary to estimate the electronic losses with rt-TDDFT precision along any path. Additionally, our examination of pseudopotential requirements yielded another valuable result: a comprehensive rt-TDDFT picture of electronic stopping in self-irradiated silicon, including a detailed description of the required pseudopotentials in all kinematic regimes.

The model accurately describes the electronic losses along any trajectory, from channels to regions of higher electron density, including the random trajectories measured experimentally. In addition, our exploration of the boundaries of the pseudopotentials required for electronic loss calculations will allow exploring other related phenomena, particularly in the low kinetic energy region, where core electrons are shown not to be required. In our self-irradiated silicon system, the different pseudopotentials within the energy ranges tested were shown to provide approximately the same results. This has not always been the case in other studies, therefore, the adequacy of pseudopotentials and the associated exchange-correlation functional is highly dependent on the system and projectile energy ranges. This is an area where further research is needed.

Methods

We studied the electronic stopping of Si ions in Si with rt-TDDFT simulations. Simulations were carried out with the Qball code46, a fork of the first-principles molecular dynamics code Qbox47. The system consisted of a 3 × 3 × 3 Si cell plus a Si-atom projectile, for a total of 217 atoms. The adequacy of this cell size was verified by comparing the converged ground-state energy as a function of the number of atoms, where only the center of the Brillouin zone (Γ) was used for k-point sampling48. In addition, systems with 64+1, 128+1, and 160+1 atoms in 2 × 2 × 2, 2 × 2 × 4, and 2 × 2 × 10 Si cells were used for certain simulations. We used Silicon pseudopotentials with 4 explicit electrons (Si4) to reproduce the 3s and 3p valence orbitals, and pseudopotentials with 12 explicit electrons (Si12) to also include the 2s and 2p core orbitals. The Si projectiles had kinetic energies ranging from 1 keV to 50 MeV, with an additional calculation at 25 eV to benchmark the pseudopotentials at low energies. The time evolution of the wavefunctions was carried out using the time-dependent propagation with enforced time-reversal symmetry algorithm (ETRS)49, as improved numerical stability was found compared to the Runge-Kutta algorithm used in ref. 21. The maximum time step for the simulations was: 2.42 as (0.1 a.u.) for fully Si4 systems, 0.24 as (0.01 a.u.) for systems with Si12 projectiles in Si4 targets, 0.18 as (0.0075 a.u.) for fully Si12 systems in 2 × 2 × 2 cells, and finally, 0.024 as (0.001 a.u.) for fully Si12 systems. These time steps were found to conserve the total energy of the system in test calculations where the projectile velocity was set to 0. Last, we used Si4 and Si12 ONCV PBE potentials with an energy cut-off of 953 eV. Initially, a higher energy cut-off of 1769 eV was found to provide well-converged ground-state energy values for the Si12 potential. However, electronic stopping calculations along the 〈110〉 off-centered channel, using the same energy cut-off as set for the Si4 system, yielded less than 0.3% electronic stopping differences in the keV-MeV range.

To calculate the electronic stopping, the projectile and the stationary atoms were constrained to keep their initial velocities. Subsequently, from the total energy of the system after the rt-TDDFT evolution, the Born-Oppenheimer energy (ground-state energy) was subtracted for each position to get the electronic excitation energy as a function of the projectile displacement over a periodic path. The average electronic stopping was measured as the slope of this energy28, in a region after the projectile ends its transient behavior and before it reenters the cell. The oscillatory fit method proposed by Quashie et al.50, used in previous electronic stopping calculations22 was not used here, as for some channel trajectories the energy oscillatory behavior was more complex than a single trigonometric function, and also, it was not suitable to calculate incommensurate trajectories. In addition, with respect to the length of the trajectories, the 2 × 2 × 2 system produced equivalent results for electronic stopping and electronic excitation energies in most kinematic regimes as the larger 3 × 3 × 3 cell. However, at 1 keV, the cell size effects become noticeable, with the stopping values for the 64-atom system tending to be lower. Therefore, we used the 64-atom lattice for systems with Si12 atoms, and projectiles within the 5–500 keV range to maintain a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. For projectiles with 500 keV or higher energies, the trajectories had to be longer due to the excitation and ionization processes of both the targets and the projectile22. Therefore, 2 × 2 × 4 cells were used up to 1 MeV and 2 × 2 × 10 cells for the remaining higher energy projectiles.

The projectile directions were chosen to favor channeling, following the molecular dynamics-based mean range for self-irradiated Si at 10 keV51. The five main directions of channeling are: 〈111〉, 〈001〉, 〈321〉, 〈112〉, and 〈110〉. Figure 9 portrays a 3 × 3 × 3 Si cell and perspectives of the described channels, including the electron densities around the bonds. Except for the 〈111〉 case, the projectiles were set to travel along the center position of the channels, meaning the low electron density regions equidistant to the neighboring atoms. The 〈111〉 center channel explores similar densities as 〈001〉 and 〈112〉, so an alternate position, addressed here as half-centered 〈111〉, was chosen to explore different atomic neighborhoods. For the 〈110〉 channel, an additional projectile position was included, here called 〈110〉 off-centered, which explores a periodic trajectory along a high-density region. In addition to the channeling directions, three incommensurate projectile trajectories were chosen, as shown by Quashie et al.50. This mechanism allows exploring different electron densities with the relatively short distances of a rt-TDDFT calculation28. The normalized directions of each incommensurate trajectory were: [0.309, 0.500, 0.809], [0.500, 0.809, 0.309], and [0.160, 0.519, 0.840]. The projectile’s initial positions (in Å) were: [2.376, 1.018, 0], [1.357, 0, 0], and [1.357, 0, 0] respectively. The last incommensurate trajectory included a collision-like 0.4 Å approach with one target atom, which was used to explore core-density regions.

Perspective view of a 216-atom silicon diamond structure and orthogonal view of the lattice along different channeling directions: half-centered 〈111〉, 〈001〉, 〈321〉, 〈112〉, and 〈110〉. The ⊗ symbol denotes the position of the projectile traveling perpendicular to the page. For the 〈110〉 direction, a second projectile position that travels along a high-density region is included, referred to as the 〈110〉 off-centered direction.

Data availability

The computational data supporting this research can be accessed openly from ref. 52.

References

Damerell, C. Applications of silicon detectors in high energy physics and astrophysics. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 226, 26–33 (1984).

Ehrlich, K. The development of structural materials for fusion reactors. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 357, 595–623 (1999).

Azeem, M. M., Di, Y., Jamil, I. & Khan, M. B. Multiscale modeling of radiation damage in oxide dispersed strengthened steel alloys: a perspective. Int. J. Eng. Works 9, 193–201 (2022).

Lindström, G. Radiation damage in silicon detectors. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 512, 30–43 (2003).

Robinson, M. T. & Oen, O. The channeling of energetic atoms in crystal lattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2, 30–32 (1963).

Eisen, F. Channeling of medium-mass ions through silicon. Can. J. Phys. 46, 561–572 (1968).

Current, M. I. Ion implantation of advanced silicon devices: past, present and future. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 62, 13–22 (2017).

Raineri, V., Privitera, V., Galvagno, G., Priolo, F. & Rimini, E. Channeling implants in silicon crystals. Mater. Chem. Phys. 38, 105–130 (1994).

Poggi, G. et al. Response of ion implanted silicon detectors to fully stopped Au ions of 11.5 A MeV impinging along crystallographic directions. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 119, 375–382 (1996).

Favuzzi, C. et al. Particle identification by means of channeling radiation in high collimated beams. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 617, 402–404 (2010).

Zarkadoula, E., Samolyuk, G. & Weber, W. J. Effects of the electron-phonon coupling activation in collision cascades. J. Nucl. Mater. 490, 317–322 (2017).

Born, M. & Oppenheimer, R. Das 2 h molehül. Ann. Phys. 389, 457 (1927).

Torrens, I. M. Computer simulation in radiation damage studies. Comput. Phys. Commun. 5, 32–43 (1973).

Runge, E. & Gross, E. K. Density-functional theory for time-dependent systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 52, 997 (1984).

Correa, A. A. Calculating electronic stopping power in materials from first principles. Comput. Mater. Sci. 150, 291–303 (2018).

Delos, J. B., Thorson, W. R. & Knudson, S. K. Semiclassical theory of inelastic collisions. I. Classical picture and semiclassical formulation. Phys. Rev. A 6, 709 (1972).

Race, C. et al. The treatment of electronic excitations in atomistic models of radiation damage in metals. Rep. Prog. Phys. 73, 116501 (2010).

Montanari, C. C. & Dimitriou, P. The IAEA stopping power database, following the trends in stopping power of ions in matter. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 408, 50–55 (2017).

Lohmann, S., Holeňák, R. & Primetzhofer, D. Trajectory-dependent electronic excitations by light and heavy ions around and below the Bohr velocity. Phys. Rev. A 102, 062803 (2020).

Ziegler, J. F., Ziegler, M. D. & Biersack, J. P. SRIM—the stopping and range of ions in matter (2010). Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 268, 1818–1823 (2010).

Lim, A. et al. Electron elevator: excitations across the band gap via a dynamical gap state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 043201 (2016).

Lee, C.-W., Stewart, J. A., Dingreville, R., Foiles, S. M. & Schleife, A. Multiscale simulations of electron and ion dynamics in self-irradiated silicon. Phys. Rev. B 102, 024107 (2020).

Jarrin, T., Richard, N., Teunissen, J., Da Pieve, F. & Hémeryck, A. Integration of electronic effects into molecular dynamics simulations of collision cascades in silicon from first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 104, 195203 (2021).

Caro, M., Tamm, A., Correa, A. & Caro, A. Role of electrons in collision cascades in solids. I. Dissipative model. Phys. Rev. B 99, 174301 (2019).

Tamm, A., Caro, M., Caro, A. & Correa, A. Role of electrons in collision cascades in solids. II. Molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 99, 174302 (2019).

Ullah, R., Artacho, E. & Correa, A. A. Core electrons in the electronic stopping of heavy ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 116401 (2018).

Sand, A. E., Ullah, R. & Correa, A. A. Heavy ion ranges from first-principles electron dynamics. NPJ Comput. Mater. 5, 1–7 (2019).

Schleife, A., Kanai, Y. & Correa, A. A. Accurate atomistic first-principles calculations of electronic stopping. Phys. Rev. B 91, 014306 (2015).

Rappe, A. M., Rabe, K. M., Kaxiras, E. & Joannopoulos, J. Optimized pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 41, 1227 (1990).

Yang, J. Opium—pseudopotential generation project. https://opium.sourceforge.net/ (2018).

Vanderbilt, D. Optimally smooth norm-conserving pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 32, 8412–8415 (1985).

Hamann, D. R. Optimized norm-conserving Vanderbilt pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 88, 085117 (2013).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Schlipf, M. & Gygi, F. Optimization algorithm for the generation of ONCV pseudopotentials. Comput. Phys. Commun. 196, 36–44 (2015).

Dal Corso, A., Baroni, S., Resta, R. & de Gironcoli, S. Ab initio calculation of phonon dispersions in II-VI semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 47, 3588 (1993).

Kononov, A., Hentschel, T. W., Hansen, S. B. & Baczewski, A. D. Trajectory sampling and finite-size effects in first-principles stopping power calculations. NPJ Comput. Mater. 9, 205 (2023).

Yost, D. C. & Kanai, Y. Electronic stopping for protons and α particles from first-principles electron dynamics: the case of silicon carbide. Phys. Rev. B 94, 115107 (2016).

Becker, P., Scyfried, P. & Siegert, H. The lattice parameter of highly pure silicon single crystals. Z. Phys. B Condens. Matter 48, 17–21 (1982).

Wittmaack, K. Misconceptions impairing the validity of the stopping power tables in the SRIM library and suggestions for doing better in the future. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 380, 57–70 (2016).

Savin, A., Umrigar, C. J. & Gonze, X. Relationship of Kohn–Sham eigenvalues to excitation energies. Chem. Phys. Lett. 288, 391–395 (1998).

Manz, T. A. & Limas, N. G. Introducing DDEC6 atomic population analysis: Part 1. Charge partitioning theory and methodology. RSC Adv. 6, 47771–47801 (2016).

Ziegler, J. F., Biersack, J. P. & Littmark, U. The Stopping and Range of Ions in Solids (Pergamon, 1985).

Caro, M., Tamm, A., Correa, A. & Caro, A. On the local density dependence of electronic stopping of ions in solids. J. Nucl. Mater. 507, 258–266 (2018).

Andersen, H. H. & Ziegler, J. F. Hydrogen. Stopping Powers and Ranges in All Elements (Pergamon, 1977).

Bethe, H. Zur theorie des durchgangs schneller korpuskularstrahlen durch materie. Ann. Phys. 397, 325–400 (1930).

Draeger, E. W. et al. Massively parallel first-principles simulation of electron dynamics in materials. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 106, 205–214 (2017).

Gygi, F. Architecture of Qbox: a scalable first-principles molecular dynamics code. IBM J. Res. Dev. 52, 137–144 (2008).

Chadi, D. J. & Cohen, M. L. Special points in the Brillouin zone. Phys. Rev. B 8, 5747–5753 (1973).

Castro, A., Marques, M. A. L. & Rubio, A. Propagators for the time-dependent Kohn-Sham equations. J. Chem. Phys. 121, 3425–3433 (2004).

Quashie, E. E., Saha, B. C. & Correa, A. A. Electronic band structure effects in the stopping of protons in copper. Phys. Rev. B 94, 155403 (2016).

Nordlund, K., Djurabekova, F. & Hobler, G. Large fraction of crystal directions leads to ion channeling. Phys. Rev. B 94, 214109 (2016).

Nuñez, R. & Sand, A. E. Research data: Path-dependent electronic stopping for self-irradiated silicon. Fairdata https://doi.org/10.23729/3f9d692c-cb64-451c-8927-ff45410e90cb (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Alfredo Correa for valuable discussions. This work was partly supported by the Emil Aaltonen Foundation and by the European Union (ERC-2022-STG, project MUST, No. 101077454). Views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. We acknowledge the computational resources provided by the Aalto Science-IT project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.N. performed the rt-TDDFT simulations, handled data curation, and developed the analytical model. A.E.S. conceived the original idea and supervised the project. Both authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Brian Cunningham and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Aldo Isidori.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nuñez-Palacio, R., Sand, A.E. Path-dependent electronic stopping for self-irradiated silicon. Commun Mater 6, 109 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00834-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00834-y