Abstract

Thermoelectric coolers (TECs), which can directly convert energy between electricity and heat, have emerged as a promising solution for electronics cooling. However, the practical application of TECs remains limited due to insufficient cooling performance. Here, we present an integrated water-cooled TEC (i-TEC) with internal flow channels embedded in ceramic substrates, effectively eliminating the limitations of traditional thermal interfaces. The i-TEC achieves superior cooling performance, reducing the temperature of an 80 W heat source by nearly 20 °C compared to conventional TECs and attaining a coefficient of performance up to 3.26. Practical applications demonstrate its capability to lower the maximum temperature of a smartphone by up to 16 °C, significantly enhancing user experience and device stability. These results highlight the great potential of these i-TECs for advanced thermal management in electronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid advancement of electronic devices has led to increased power density and miniaturization, making efficient thermal management systems essential for maintaining performance, reliability, and longevity1,2,3. Inefficient heat dissipation in electronics can cause overheating, decrease device reliability, and degrade performance4,5. Thus, developing advanced heat dissipation technologies has become critical to overcoming these challenges and supporting the ongoing trend of high-power-density electronics6. Thermoelectric coolers (TECs), capable of directly converting energy between electricity and heat, are regarded as a viable solution for electronics cooling7,8,9. Compared to conventional cooling methods, TECs offer several distinct advantages, including compact size, fast response times, precise temperature regulation, and the ability to achieve sub-ambient cooling10.

In practice, the application of TECs for electronics cooling remains limited, primarily due to the inadequate cooling performance of existing TECs11. Developing TECs with enhanced cooling performance is crucial to advancing their practical applications in electronics cooling12,13,14,15,16,17. To enhance the cooling performance of thermoelectric devices, researchers have developed thermoelectric materials with superior properties and proposed various strategies to optimize thermoelectric cooling systems, which can be categorized into three main approaches: (1) Optimizing the thermal design of the cooling system18,19,20,21,22, such as improving the heat dissipation capacity at the heat-dissipating side of the TECs; (2) Refining the topological design of the device structure23,24,25, such as adjusting the number, height, and cross-sectional area of the thermoelectric arms; (3) Enhancing the operating parameters of the device26,27,28, such as optimizing the input current. Among these, optimizing the heat dissipation capacity at the device’s heat-dissipating side is a critical approach to effectively enhancing cooling performance. Sun et al. proposed that enhancing the thermal conductivity of the external heat sink on the heat-dissipating side of the device can effectively lower its temperature, thereby improving the cooling performance of thermoelectric devices19. Xie et al. reported a TEC with an optimized plate-fin heat sink, which increases the heat transfer and enhances cooling performance20. Naphon et al. incorporated Al₂O₃ nanoparticles into the coolant of water-cooled TECs, which enhanced the thermal conductivity of the coolant and consequently boosted TEC cooling performance22. Although these strategies improve the heat dissipation capacity of external heat sinks, the contact thermal resistance between heat sinks and TECs (typically connected by thermally conductive silicone greases) remains too high29,30,31,32,33,34,35, severely limiting the heat dissipation capacity of the TEC’s heat-dissipating side. To further maximize heat dissipation capacity, a feasible alternative is to design an integrated device structure that eliminates high contact thermal resistance. However, high-performance integrated TECs have been rarely explored for electronics cooling. The primary challenge lies in the difficulty of designing and fabricating such integrated TECs.

Herein, we propose a feasible design solution for integrated water-cooled TECs (i-TECs), realized by embedding internal flow channels within the ceramic substrates. The design of an integrated structure maximizes heat dissipation capacity, thereby achieving superior cooling performance for electronics cooling. The fabricated i-TEC can further reduce the cooling temperature of an 80 W heat source by nearly 20 °C compared with conventional TECs, while achieving an impressive coefficient of performance (COP) up to 3.26. In practice, we demonstrate that our i-TEC effectively reduce the maximum temperature of a smartphone by up to 16 °C, significantly improving user experience and enhancing smartphone performance, thereby highlighting its potential for electronics cooling.

Results and discussion

The design of i-TEC

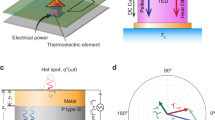

Efficient heat dissipation at the heat-dissipating side of the TEC is essential for achieving optimal cooling performance at the heat-absorbing side. To effectively optimize the heat dissipation capacity at the TEC’s heat-dissipating side, we proposed the i-TEC design, which incorporates a ceramic substrate integrated with water cooling. Figure 1A, B schematically illustrates the structure of our i-TEC (Fig. 1B) in comparison to the previously reported non-integrated water-cooled TEC (Fig. 1A). Thermal interface materials, such as thermal grease, are commonly used in previous studies to connect the TEC to external water-cooled cold plate, but their high thermal resistance significantly impedes heat transfer from the heat-dissipating side of the TEC to the water-cooling medium, resulting in suboptimal cooling temperatures at the heat-absorbing side and diminished cooling performance. To enhance heat transfer at the interface of the heat-dissipating side, an i-TEC with water-cooling channels embedded in the ceramic substrate could be an effective approach to enhance cooling performance.

The effect of integrated structure on the temperature profile across TEC is theoretically studied via finite element analysis (FEA). The FEA results (Fig. 1C–E) show the temperature distribution on a cross-section of the two types of TECs by setting the coolant temperature (TC) at 293 K. The details of the modeling can be found in Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Table S1. In the case of the TEC with a non-integrated structure, the temperature of the heat-dissipating side (TD, 335.5 K) is significantly higher than TC, indicating a substantial heat dissipation barrier at the heat-dissipating side of the TEC. In contrast, our i-TEC with an integrated structure can significantly enhance heat dissipation capacity at the heat-dissipating side, showing a lower TD of 303.0 K. As a result, our proposed i-TEC exhibits a better cooling performance at the heat-absorbing side, lowering the heat source temperature (TH) to 359.8 K, significantly lower than the 380.8 K achieved by conventional TECs.

Fabrication of i-TEC

The preparation of a TEC with an integrated water-cooled structure is fundamental to optimizing cooling performance. For clarity, the full process to fabricate the i-TEC is illustrated schematically in Fig. 2A. In brief, a copper-clad ceramic plate with embedded internal flow channels was initially designed and fabricated. Solder pastes and thermoelectric legs were accurately positioned sequentially on the copper electrode sheets. Finally, the i-TEC was assembled after reflow soldering processes to join the thermoelectric legs in a series circuit with the copper electrodes at both ends. Additional details about the preparation process are provided in the experimental section.

The optical images in Fig. 2B show that the fabricated i-TEC consisting of 126-pair thermoelectric legs has a cross-sectional area of 40 × 40 mm² and a height of 10 mm. The measured internal resistance of the i-TEC is approximately 2.1 Ω (Supplementary Fig. S2), which is in good agreement with the theoretical value calculated based on the thermoelectric material’s properties, indicating the effectiveness of our fabrication process. The fabricated i-TEC exhibited excellent stability, maintaining consistent cooling performance even after 400 continuous thermal cycles over a period exceeding 100 h (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Cooling performance of i-TEC

To examine the effect of our integrated structure on heat dissipation capacity, we experimentally assessed the cooling performance of the fabricated i-TEC. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, an experimental setup was employed to evaluate the cooling performance of the i-TEC against heat sources. In brief, two electric heating rods were embedded within the copper block to simulate a heat source with stable power input and uniform temperature distribution (Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5). Four T-type ultrathin thermocouples were inserted into small holes at the center of the copper block, and their average was calculated to precisely represent the surface temperature of the heat source (TH). The heat-absorbing side of the i-TEC was in contact with the heat source, and the flow channel in the heat-dissipating side of the i-TEC was connected to external water pipes. A commercial DC power supply (SS-3020KD, A-BF) provided power to the i-TEC. A data acquisition system (34,980 A, Keysight) simultaneously recorded the heating power, temperature of the heat source, coolant temperature, and coolant flow rate at 1.0 Hz.

A Photographs of the experimental setup used to evaluate the cooling performance of the TECs. B Comparison of the cooling performance of the i-TEC and the control non-integrated TEC under various conditions. C The experimentally measured TH as a function of PH under the cooling conditions of the i-TEC and the control TEC. D Schematic diagram of the thermal circuit model for heat source cooling using the i-TEC.

The advantages of the integrated structure in terms of cooling characteristics are shown in Fig. 3B, C. For comparison, a typical non-integrated TEC using an external water-cooled cold plate was also tested as the control device in this part. During the test, the heating power (PH) was initially set to 20 W, and the TEC was activated immediately upon TH reaching 100 °C; subsequently, the PH was adjusted to 40, 60, 80 W, and finally turned off. The current supplied to the TECs was kept constant at 6 A; the inlet temperature and flow rate of the coolant were maintained at 20 °C and 1 L/min, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3B, our i-TEC provides a superior cooling on the heat source compared to the control TEC. For the 80 W heat source, the temperature is maintained at 90.3 °C using i-TEC, which is considerably lower ( ~ 20 °C) than 109.2 °C observed with the control TEC. Moreover, when PH is low (i.e., 20 W and OFF), the TEC can reduce TH below ambient levels (even to sub-zero temperatures), highlighting the unique advantages of TEC cooling. Furthermore, we observed that there is a linear relationship between the TH and PH, as shown in Fig. 3C. For the heat source using i-TEC, the relationship TH = 1.47PH − 27.4 [°C] is obtained through a linear fit, of which the slope value (1.47) is less than that (1.70) of the control TEC, indicating a lower thermal resistance for the i-TEC compared with that of the control TEC correspondingly.

To explain the above experimental results and further understand the effect of the integrated structure on cooling performance, we propose a thermal circuit model for cooling using i-TEC, as shown in Fig. 3D. The heat-absorbing side of the i-TEC receives heat from both the heat source (QH) and its own Joule heat (QJ), and transfers the heat to the heat-dissipating side in the form of Peltier heat (QP) and Fourier heat (QF). Thus, the thermal equilibrium at the heat-absorbing side of the device can be expressed as

where S, I, θTEC, and R represent the Seebeck coefficient, electric current, thermal resistance and electrical resistance of the TEC, respectively; TA and ΔTTEC represent the temperature of the heat-absorbing side and the temperature difference between the two sides, respectively.

Similarly, thermal equilibrium at the heat-dissipating side of the device can be expressed as:

where QC is the heat transferred from the heat-dissipating side to the coolant.

Further analysis on the relationship between temperature and thermal resistance in the circuit yields the following equation

where θC is the convective thermal resistance between the coolant and TEC’s heat- dissipating side; θTIM is the interfacial thermal resistance between the heat source and TEC heat-absorbing side.

According to the three equations above, the heat source temperature can be calculated as

Therefore, the relationship between TH and PH is linear, in good agreement with Fig. 3C, with the slope representing the total thermal resistance of the heat transfer path from the heat source to the coolant. Since our i-TEC eliminates the interfacial thermal resistance between the heat-dissipating side and the coolant, it exhibits a lower slope between TH and PH, resulting in superior cooling performance compared to the control TEC. It should be noted that Eq. (4) serves as a qualitative model to analyze the factors affecting TH, as thermoelectric material properties are inherently temperature-dependent. A more comprehensive model incorporating the temperature dependence of these parameters will be developed in future work.

According to Eqs. 1 and 2, the current supplied to the i-TEC is a key parameter influencing its cooling performance. To investigate the impact of I on the cooling performance of the i-TEC, we analyzed its effect at various power levels. Figure 4A–C show the variation in TH over elapsed time for different I ranging from 3 A to 7 A, with the PH set at 40, 60, and 80 W, respectively. Clearly, the i-TEC can effectively and quickly reduce TH within the given current range, despite variations in the final equilibrium temperatures. As a result, Fig. 4D reveals that the TH initially decreases and then increases with the rise in I. This is because the favorable Peltier effect and the unfavorable Joule effect increase simultaneously with increasing I, while Joule effect dominates at higher current levels. The lowest TH values (29.8 °C at 40 W, 59.2 °C at 60 W, and 89.0 °C at 80 W) were achieved at an optimal I of 5 A. In addition, the COP of the TEC is also influenced by current, which is expressed as COP = PH/(I2R + SIΔTTEC). As shown in Fig. 4E, at the same PH, the COP enhances monotonically with decreasing I. However, excessively low I values are insufficient to effectively cool the heat source, as observed when using a 3 A current to cool an 80 W heat source. Thus, for practical applications in electronics cooling, it is essential to comprehensively consider the device temperature and the COP to set the TEC’s current appropriately. The comparison of the cooling performance of TECs employing various heat-side dissipation strategies and conventional cooling methods is summarized in Supplementary Table S2.28,29,30,36,37,38,39,40,41,42 TEC-based approaches offer distinct advantages, including rapid thermal response and the capability to achieve sub-ambient cooling. Among these, our i-TEC exhibits superior performance, delivering a high cooling power of 80 W and a COP of 3.26—one of the highest values reported to date for TECs.

For water-cooled i-TEC, the inlet temperature (TC) and flow rate (v) of the coolant are also important parameters influencing the cooling performance. As illustrated in Fig. 5, we investigated the effect of TC and v on the cooling performance of the heat source. The heating power and current supplied to the TECs was kept constant at 60 W and 5 A, respectively. When TC remains constant, the TH decreases rapidly at first and then more gently as v varies from 0.5 to 1.25 L/min. Moreover, the i-TEC demonstrates a better cooling performance at lower TC for the same v; e.g., TH decrease from 60 to 55 °C as TC decreases at the v of 1.25 L/min. In general, lower water inlet temperature and increased flow rate help i-C achieve better cooling performance. In other words, a lower water inlet temperature and a higher flow rate reduce the heat source temperature, confirming that enhancing the heat dissipation capacity at the TEC’s heat-dissipating side is one of the effective methods to improve its cooling performance.

Application of the i-TEC in smartphone thermal management

As smartphones become more powerful and multifunctional, heat generation in internal electronic components has emerged as a prominent challenge, affecting both device performance and user experience. Heat accumulation during prolonged use of high-performance applications (e.g., gaming or video rendering) can trigger overheating protection, performance throttling, and user discomfort. Therefore, efficient thermal management for smartphones has become a critical focus for ensuring stable operation and enhancing user satisfaction. TECs have emerged as a promising active cooling solution for smartphones due to their ability to rapidly and precisely reduce target temperatures.

To demonstrate the versatile application of the high cooling capacity of our i-TEC, Fig. 6 illustrates its effectiveness in achieving efficient cooling for smartphones. Figure 6A presents a conceptual diagram illustrating the application scenario of our i-TEC for smartphone cooling. The i-TEC is attached to the smartphone’s back to absorb heat generated by the device, ensuring stable performance under heavy-load conditions and enhancing the user experience. To evaluate the cooling performance of the i-TEC, we monitored temperature changes on the smartphone’s back during 30 min of heavy-load operation under three conditions: without TECs, with the control TEC, and with the i-TEC. Infrared thermal images (Fig. 6B, C) show that the i-TEC’s heat-dissipating side maintains a very low temperature, significantly reducing the smartphone’s backside temperature. A symmetrical thermocouple was attached to the highest-temperature point to record changes in the maximum temperature, and the results are shown in Fig. 6D. Clearly, the implementation of the i-TEC significantly reduces the steady-state maximum temperature by nearly 16 °C, from a scalding 49 °C to a comfortable 33 °C. Even in comparison to the control TEC, the i-TEC achieves a reduction of about 4 °C. This greatly enhances the user experience while also boosting the smartphone’s performance. The results confirm the exceptional performance and practical applicability of our i-TEC in smartphone thermal management.

A Conceptual diagram illustrating the application scenario of i-TEC for smartphone cooling. Infrared thermal images of the back of the smartphone: B without i-TEC and C with i-TEC. D Maximum temperature on the back of the smartphone as a function of elapsed time under three different conditions (without TECs, with the control TEC and with the i-TEC).

Conclusion

An i-TEC with internal flow channels embedded within ceramic substrates has been fabricated, effectively eliminating the high thermal resistance observed in conventional TEC designs. Through theoretical modeling, experimental validation, and practical applications, the i-TEC exhibits outstanding cooling performance and significant potential for real-world thermal management systems. The i-TEC achieves enhanced heat dissipation on the heat-dissipating side, reducing the cooling temperature of an 80 W heat source by approximately 20 °C compared to conventional TECs, while maintaining a COP up to 3.26. Experimental results confirm a linear relationship between heat source temperature and power input, with the i-TEC exhibiting significantly lower thermal resistance compared to non-integrated designs. We further identify the optimal operating conditions, including input current, coolant temperature and flow rate, to further improve cooling performance. In practical applications, the i-TEC proves highly effective for smartphone thermal management. By lowering the maximum temperature of a smartphone under heavy-load operation by approximately 16 °C, the i-TEC significantly improves user experience, prevents performance throttling, and ensures stable device operation. Future work will focus on further improving cooling performance by optimizing the topology of flow channels and minimizing contact thermal resistance between the heat source and the TEC. This approach, combined with our methods for implementing i-TEC, could greatly enhance heat dissipation from electronic devices to the environment, paving the way for the development of high-performance TECs for electronics cooling.

Methods

Fabrication of i-TEC

Bi₂Te₃-based thermoelectric legs (1.4 × 1.4 × 1.6 mm3) and copper clad alumina substrates (40 × 40 × 0.8 mm3) were procured from Weixian Zhongtian Electronic Co., Ltd. The thermoelectric properties of p type and n-type Bi₂Te₃-based materials, as measured and reported by the supplier, are listed in Supplementary Table S3.

The assembly process of the i-TEC is illustrated schematically in Fig. 2A. Three types of alumina substrates were utilized in the design. One substrate is a 6 mm thick plate with flow channel grooves for the coolant, while the other two are 0.8 mm thin plates bonded with copper electrodes. Detailed photographs of the three alumina substrates are provided in Supplementary Fig. S6. The alumina substrate containing flow channels was bonded to a copper-clad alumina substrate using thermal conductive silicone adhesive (K5205, Kafuter), forming a sealed copper-clad plate with embedded flow channels. Subsequently, solder pastes (Sn64Bi35Ag1, LF-666, Kellyshun) were applied to the copper electrode sheets via a mask, and thermoelectric legs were precisely positioned on the pastes using a mold. Finally, the assembly undergoes two reflow soldering processes to connect the thermoelectric legs in series with the copper electrodes at both ends and ensuring electrical connectivity of all n–p pairs. A reflow oven (ZB2015HL, Huaqi Zhengbang) was employed with a soldering temperature setting of 220 °C and a soldering time of 30 min. The i-TEC was soldered to power cables and encapsulated with silicone rubber sealant (704, Ailike) for waterproofing, dustproofing, and electrical insulation.

Experiment using TEC for smartphone thermal management

The i-TEC was attached to a commercial smartphone using a thermally conductive silicone pad. The smartphone runs testing software to simulate heat dissipation performance under heavy-load conditions. The current supplied to the TECs was kept constant at 5 A. The inlet temperature and flow rate of the coolant were maintained at 20 °C and 1 L/min, respectively. An infrared camera (288, Fotric) was used to measure the temperature distribution on the backside of the smartphone. A thermometer (UT325F, Uni-T) was connected to a thermocouple to record the maximum temperature over runtime. The average environment temperature was 25 °C with a standard deviation of 0.5 °C.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Li, Y. et al. Transforming heat transfer with thermal metamaterials and devices. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 488–507 (2021).

van Erp, R., Soleimanzadeh, R., Nela, L., Kampitsis, G. & Matioli, E. Co-designing electronics with microfluidics for more sustainable cooling. Nature 585, 211–216 (2020).

Li, J. et al. Ultrathin, soft, radiative cooling interfaces for advanced thermal management in skin electronics. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg1837 (2023).

Sarkar, S., Gupta, R., Roy, T., Ganguly, R. & Megaridis, C. M. Review of jet impingement cooling of electronic devices: emerging role of surface engineering. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 206, 123888 (2023).

Yang, S., Li, J., Cao, B., Wu, Z. & Sheng, K. Investigation of Z-type manifold microchannel cooling for ultra-high heat flux dissipation in power electronic devices. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 218, 124792 (2024).

Qin, Y. et al. Thermal management and packaging of wide and ultra-wide bandgap power devices: a review and perspective. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 56, 093001 (2023).

Qin, Y. et al. Grid-plainification enables medium-temperature PbSe thermoelectrics to cool better than Bi2Te3.Science 383, 1204–1209 (2024).

Kishore, R. A., Nozariasbmarz, A., Poudel, B., Sanghadasa, M. & Priya, S. Ultra-high performance wearable thermoelectric coolers with less materials. Nat. Commun. 10, 1765 (2019).

Fan, W. et al. High-performance stretchable thermoelectric generator for self-powered wearable electronics. Adv. Sci. 10, 2206397 (2023).

Chen, W.-Y., Shi, X.-L., Zou, J. & Chen, Z.-G. Thermoelectric coolers for on-chip thermal management: materials, design, and optimization. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 151, 100700 (2022).

Chen, W. Y., Shi, X. L., Zou, J. & Chen, Z. G. Thermoelectric coolers: progress, challenges, and opportunities. Small Methods 6, 2101235 (2022).

Dong, G. et al. Oriented Bi2Te3-based films enabled high performance planar thermoelectric cooling device for hot spot elimination. Nat. Commun. 15, 9695 (2024).

Chen, Z.-G. & Liu, W.-D. Thermoelectric coolers: infinite potentials for finite localized microchip cooling. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 121, 256–262 (2022).

Zhu, W. et al. Design and optimization of a temperature controller with low overshoot, fast respond and high COP based on water-source thermoelectric heat pump. Appl. Therm. Eng. 242, 122473 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Maximizing the performance of n-type Mg3Bi2 based materials for room-temperature power generation and thermoelectric cooling. Nat. Commun. 13, 1120 (2022).

Hong, S. et al. Wearable thermoelectrics for personalized thermoregulation. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw0536 (2019).

Huang, H.-S., Weng, Y.-C., Chang, Y.-W., Chen, S.-L. & Ke, M.-T. Thermoelectric water-cooling device applied to electronic equipment. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 37, 140–146 (2010).

Lv, S. et al. Study of different heat exchange technologies influence on the performance of thermoelectric generators. Energy Convers. Manag. 156, 167–177 (2018).

Sun, W., Liu, W.-D., Liu, Q. & Chen, Z.-G. Advances in thermoelectric devices for localized cooling. Chem. Eng. J. 450, 138389 (2022).

Xie, X. et al. Performance analysis and optimal design of a water-cooled thermoelectric component for air cooling based on simulation and experiments. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 141, 106576 (2023).

Xu, Z., Li, C., Zhao, H., Zheng, Y. & Zhang, J. Design and performance analysis of hot side heat sink of thermoelectric cooler device based on simulation and experiment. Energy Sci. Eng. 11, 4463–4480 (2023).

Naphon, P., Wiriyasart, S. & Hommalee, C. Experimental and numerical study on thermoelectric liquid cooling module performance with different heat sink configurations. Heat Mass Transf. 55, 2445–2454 (2019).

Shittu, S., Li, G., Zhao, X. & Ma, X. Review of thermoelectric geometry and structure optimization for performance enhancement. Appl. Energy 268, 115075 (2020).

He, R., Schierning, G. & Nielsch, K. Thermoelectric devices: a review of devices, architectures, and contact optimization. Adv. Mater. Technol. 3, 1700256 (2017).

Qiu, C. & Shi, W. Comprehensive modeling for optimized design of a thermoelectric cooler with non-constant cross-section: theoretical considerations. Appl. Therm. Eng. 176, 115384 (2020).

Luo, D. et al. Performance investigation and design optimization of a battery thermal management system with thermoelectric coolers and phase change materials. J. Clean. Prod. 434, 139834 (2024).

Zhou, L., Meng, F. & Sun, Y. Numerical study on infrared detectors cooling by multi-stage thermoelectric cooler combined with microchannel heat sink. Appl. Therm. Eng. 236, 121788 (2024).

Sun, W. et al. Performance optimization of a dual-thermoelectric-liquid hybrid system for central processing unit cooling. Energy Convers. Manag. 290, 117222 (2023).

Luo, D. et al. Performance analysis of a novel thermoelectric-based battery thermal management system. Renew. Energy 224, 120193 (2024).

Liu, X., Zhang, C.-F., Zhou, J.-G., Xiong, X. & Wang, Y.-P. Thermal performance of battery thermal management system using fins to enhance the combination of thermoelectric cooler and phase change material. Appl. Energy 322, 119503 (2022).

Hu, B., Shi, X.-L., Zou, J. & Chen, Z.-G. Thermoelectrics for medical applications: progress, challenges, and perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 437, 135268 (2022).

Wiriyasart, S., Suksusron, P., Hommalee, C., Siricharoenpanich, A. & Naphon, P. Heat transfer enhancement of thermoelectric cooling module with nanofluid and ferrofluid as base fluids. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 24, 100877 (2021).

Cuce, E., Guclu, T. & Cuce, P. M. Improving thermal performance of thermoelectric coolers (TECs) through a nanofluid driven water to air heat exchanger design: an experimental research. Energy Convers. Manag. 214, 112893 (2020).

Siddique, A. R. M., Bozorgi, M., Venkateshwar, K., Tasnim, S. & Mahmud, S. Phase change material-enhanced solid-state thermoelectric cooling technology for food refrigeration and storage applications. J. Energy Storage 60, 106569 (2023).

Alzuguren, I., Aranguren, P., Casi, Á, Erro, I. & Rodríguez, A. Thermoelectrics working in favour of the natural heat flow to actively control the heat dissipation. Int. Commun. Heat. Mass Transf. 156, 107607 (2024).

Hu, H. M., Ge, T. S., Dai, Y. J. & Wang, R. Z. Experimental study on water-cooled thermoelectric cooler for CPU under severe environment. Int. J. Refrig. 62, 30–38 (2016).

Yi, L. et al. Enhanced cooling model for GaN HEMT based on thermoelectric cooler. Appl. Therm. Eng. 265, 125576 (2025).

Li, S. et al. Active thermal management of high-power LED through chip on thermoelectric cooler. IEEE Trans. Elect. Dev.68, 1753–1756 (2021).

Gu, Z. et al. Enhancing heat transfer performance in 3D-printed integrated vapor chamber using composite structures. Appl. Therm. Eng. 234, 121292 (2023).

Rezk, K., Abdelrahman, M. A., Attia, A. A. A. & Emam, M. Thermal control of temperature-sensitive electronic components using a vapor chamber integrated with a straight fins heat sink: an experimental investigation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 217, 119147 (2022).

Wei, A., Qu, J., Qiu, H., Wang, C. & Cao, G. Heat transfer characteristics of plug-in oscillating heat pipe with binary-fluid mixtures for electric vehicle battery thermal management. Int. J. Heat. Mass Transf. 135, 746–760 (2019).

Mbulu, H., Laoonual, Y. & Wongwises, S. Experimental study on the thermal performance of a battery thermal management system using heat pipes. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 26, 101029 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52376151), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (No. LZ23E060003) and the Science & Technology Project of State Grid Corporation of China (project number: 5108-202218280A-2-438-XG).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.F. designed, conducted experiments, and drafted the manuscript. Z.W. and S.H. analyzed the experimental data and revised the manuscript. Z.W. and K.S. initiated the research, obtained the funding and supervised the work. All authors have given approval to the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks L.M., R.L. and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: J.S.L.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, W., Wu, Z., Hong, S. et al. High-performance integrated thermoelectric coolers for electronics cooling. Commun Mater 6, 114 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00837-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00837-9