Abstract

Improved process for the growth of NbN by plasma-assisted molecular beam epitaxy (PAMBE) is needed for the fabrication of Josephson junctions, that are building blocks of qubits in quantum computers. Here we propose an approach to grow cubic δ-NbN on (0001) GaN substrates by PAMBE. We use metal-rich conditions with indium as a surfactant to facilitate the growth of NbN layers, InAlN/NbN, and InGaN/NbN superlattices. For In-rich conditions: (i) structural and electrical quality of NbN is improved as confirmed by larger grain size and higher transition temperature to superconducting phase, (ii) the growth of thin InAlN and InGaN layers on NbN is possible with flat interfaces. High critical current density up to 1 kA cm−2 was obtained for NbN/InAlN/NbN Josephson junctions with 3 nm tunneling barrier. Indium-rich conditions allow the integration of δ-NbN with other III-N compounds by PAMBE preserving the high structural quality of the grown heterostructures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent advancement of plasma-assisted molecular beam epitaxy (PAMBE) opens a new perspective for integration of superconductors and semiconductors on common platform1. On one hand, there is well-established PAMBE technology for the growth of III-N optoelectronic devices like laser diodes, and transistors2,3. On the other hand, there are transition metal nitrides (TMNs) with unique properties4, an example of which is superconducting NbN. The similarities between cation sublattices of GaN, AlN, and NbN, and also similar lattice constants, create a possibility of epitaxial merging of those materials, which in turn opens a perspective for better control of parameters for devices containing NbN/III-N heterostructures. Therefore, there is a growing interest in developing epitaxy of NbN on nitride substrates by PAMBE5.

It has been shown that the properties of the NbN layers depend on the growth conditions. A recent review paper summarizes the advancements of NbN deposition by several different growth methods6 including magnetron sputtering7,8,9,10, pulsed layer deposition11, and PAMBE12,13,14. The NbN crystallizes in both cubic rocksalt and wurtzite hexagonal structures. The critical temperature for transition to the superconducting phase, Tc, depends on the crystal structure. The hexagonal phases (β and ϵ) have Tc below 1 K, while cubic phases γ and δ have Tc of 11 K and 17 K, respectively12. Up to now, NbN has been deposited mainly by electron-beam evaporation and sputtering therefore, it is typically polycrystalline with limited possibilities to precisely control its growth15.

It was demonstrated that by adjusting growth parameters in PAMBE, mainly substrate temperature, the control of cubic or wurtzite NbN phases can be achieved12. The cubic phase δ-NbN can be grown at the temperature range 650–800 °C. The rather high Tc of δ-NbN makes this phase attractive for quantum technology applications like transmons containing NbN/AlN/NbN Josephson junctions (JJs) which serve as scalable building blocks for qubit manipulation in quantum computers, or highly sensitive single photon-detectors like superconducting bolometers16,17.

It was identified that the quality of the δ-NbN layers grown on hexagonal-lattice substrates (GaN5, Al2O312, SiC13) is degraded by the creation of extended defects, twin boundaries, during NbN growth. The growth of NbN on different miscut SiC substrates led to the conclusion that it is possible to reduce the number of twins on high miscut substrates18, but the twin boundaries were not fully eliminated. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the impact of the growth conditions for a given substrate on the NbN structural and electrical properties.

Parameters impacting the NbN-based JJs properties are the thickness and quality of a barrier between superconductors. The maximum critical current density Jc depends strongly on the thickness of the tunneling AlN barrier. For the sputtering method, the thickness of the barrier was as low as 1 nm19. The reported Jc for sub-micrometer scale devices and 1 nm AlN barrier was around 100 kA cm−2. However, there is still discussion about reproducibility of barrier below 2 nm thickness, since reported variation of AlN/NbN interface obtained by sputtering is 1–3 monolayers20,21. Therefore, the PAMBE technique, which can grow atomically flat structures, can be a viable alternative for the sputtering process. The attractive perspective of the development of a nitride platform for semiconducting/superconducting AlN/δ-NbN structures grown by PAMBE should be somewhat modified due to the presence of twin boundaries discussed above and thermodynamics of NbN alloys with liquid Al. It was demonstrated that liquid Al deteriorates NbN crystal surface during the PAMBE process, therefore, the AlN growth on NbN was possible only under nitrogen-rich (N-rich) conditions5. However, it is known that the growth of AlN, GaN or InN in PAMBE under N-rich conditions leads to three-dimensional growth, which deteriorates the the upper NbN/AlN interface. A rough interface between AlN and NbN may prevent the formation of a tunneling barrier in JJs, which probably explains why no experimental evidence for operating JJs by PAMBE was reported. It is already well documented that high crystal quality growth of AlN, AlGaN, or InAlN by PAMBE can be achieved by using indium as a surfactant22,23,24,25. It was explained theoretically26 that below the liquid indium monolayer, a new adatom enhanced lateral diffusion channel for nitrogen atoms is formed.

The motivation for this work was to develop the epitaxial process that would allow for the integration of NbN with III-nitrides leading to the high-quality NbN/III-N/NbN JJs. We investigated unexplored areas, where indium is used as a surfactant during NbN, NbN/InAlN, and NbN/InGaN growth. In this paper, we (i) compare the quality of NbN layers grown with and without indium as a surfactant, (ii) investigate the superlattices of NbN/InAlN and NbN/InGaN grown under indium-rich conditions, and (iii) demonstrate NbN/InAlN/NbN JJs grown on (0001) GaN bulk substrates. We prove that it is possible to grow thin layers of InAlN and InGaN on NbN using indium as a surfactant. Additionally, we show that the use of an indium metallic layer improves the quality of δ–NbN as confirmed by detailed transmission electron microscopy studies and electrical characteristics of the grown layers. The presented results indicate that the growth of NbN/III-N structures under indium-rich conditions opens possibilities for PAMBE to fabricate atomically thin structures with sharp interfaces.

Results and discussion

We focused on the growth of δ-NbN due to its high Tc that can be interesting for devices like JJs. The structures grown and analyzed in this work are presented in Fig. 1. First, we investigated the growth of 30-50 nm δ-NbN layers on bulk (0001) GaN (Fig. 1a) under indium-rich (In-rich) and N-rich conditions. Next, structures shown in Fig. 1(b-e) were grown under In-rich conditions. Detailed growth conditions for these samples are provided in the Methods section.

Properties of NbN layers grown with indium as surfactant on (0001) GaN substrates

The 30 nm NbN layer was grown on (0001) GaN substrates with 0.4° miscut toward the m-direction at the temperature of 650 °C under In-rich conditions. For these conditions, a thin metallic In layer was kept on the NbN surface during growth. We use such conditions, since from our previous experience in the growth of III-N, such a metallic layer is beneficial for step-flow growth26. Additionally, as a reference, another NbN layer was grown in the same manner, but without indium as a surfactant (N-rich conditions).

The NbN layers' microstructure is shown in Fig. 2. Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) observations showed that the NbN layer grown under N-rich conditions (Fig. 2a) is composed of δ-NbN [111]-oriented columnar grains with a diameter of about 5–10 nm, separated by voids a few nanometers in diameter. This microstructure results in a significant surface roughness. In the case of the NbN layer grown under In-rich conditions, no columnar grain formation was observed in STEM studies (Fig. 2b), as a uniform NbN layer was obtained. High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image in Fig. 2c revealed a stripy contrast typical for superimposed grains of δ-NbN with opposite zone axes (\([\overline{1}10]\) and \([1\overline{1}0]\))27. The appearance of NbN grains with opposite orientations was previously observed by Wright et al.5 and linked to substrate surface termination at individual atomic steps, leading to the nucleation of δ-NbN with different initial stacking. The lateral size of the grains was no larger than about 10 nm. Moreover, we noticed a clear tendency to void formation at the defective boundaries between adjacent grains, which gives rise to columnar growth. These voids form already after the growth of 5 nm of NbN (Fig. 2c). As a result, the surface of NbN grown in N-rich conditions is rough.

STEM images of NbN layers grown under N-rich (a) and In-rich (b) conditions with corresponding HRTEM images in (c) and (d), respectively. The yellow boxes indicate the size of NbN grains: 10 nm for N-rich and 30 nm for In-rich conditions. The insets in Figs. (c) and (d) show an FFT of the single-grain region marked with the yellow boxes in these images. All images are taken along the \([11\overline{2}0]\) GaN zone axis. Schematic representation of the atomic structure at NbN grain boundary for N-rich (e) and In-rich (f) conditions.

For the NbN layer grown with In as a surfactant, we also observed the formation of grains with opposite orientations. However, the average lateral size was about three times larger (30 nm) than in the case of N-rich conditions as exemplified in Fig. 2 (cf. figures c and d, where the yellow boxes represent a typical grain size for both layers). To investigate in more detail the microstructure of δ-NbN grown on a GaN substrate under In-rich conditions, high-resolution STEM images were taken. In Fig. 3a, the boundary between the two δ-NbN grains is shown (indicated by an arrow). These grains form a twin boundary up to a layer thickness of ~5 nm. Then, as seen in Fig. 3b, an inclusion appears at the boundary, likely a δ-phase oriented at a different angle relative to the neighboring grains. Note that, contrary to the N-rich conditions, we do not observe the formation of voids at such places. The differences observed at grain boundaries for N-rich and In-rich conditions are schematically shown in Fig. 2e and f, respectively.

We hypothesize that indium acts as a surfactant by enhancing nitrogen diffusion and incorporation during NbN growth, similar to metal-rich conditions in III-nitrides26. However, twin formation remains a challenge due to the cubic NbN phase’s rotational symmetry. As shown in Fig. 2c, voids appear at twin boundaries, likely due to high interfacial energy and limited nitrogen diffusion under N-rich conditions. The surface In layer may facilitate nitrogen incorporation at these boundaries, reducing void formation. This could also explain the presence of misoriented NbN inclusions that locally bridge twins, contributing to improved surface morphology. However, the application of indium as a surfactant does not completely suppress twin formation. Alternative approaches may include the use of substrates with large miscut angles18 or the employment of m-plane substrates, as suggested in the context of ScN epitaxy28.

To verify whether the use of indium as a surfactant affects the chemical composition of the NbN layer, energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping was performed on the area shown in Fig. 3c. The EDS maps (Figs. 3d and e) reveal a sharp chemical interface between GaN and NbN. In the case of indium (Fig. 3f), a slight increase in signal is observed at the GaN/NbN interface that can be attributed to the stable In on (0001)GaN adsorption structure29. However, no tendency for localized indium incorporation (e.g. at defect sites) into the NbN layer was observed, as the EDS signal intensity remained low and uniform throughout the entire NbN layer.

Figure 4 presents a comparison of temperature-dependent resistance measurements for NbN layers. For In-rich conditions, the transition to the superconducting phase is observed at around 8.8 K, much higher than for the N-rich case (5.8 K). This indicates a higher quality of NbN grown at In-rich conditions. We would like to mention here that for δ-NbN we observe much higher Tc = 12 K, but for samples grown at much higher temperatures, namely 750 °C at N-rich conditions. We are working now on the configuration of our PAMBE reactor to go to higher growth temperatures with indium as a surfactant.

Growth of InGaN/NbN and InAlN/NbN superlattices

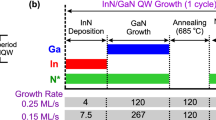

To investigate in more detail the growth of NbN in PAMBE in In-rich conditions, we fabricated InGaN/NbN heterostructures. The designed structures are shown in Fig. 1. The first structure (Fig. 1b) consists of 40 nm In0.04Ga0.96N, 3 nm NbN, and 20 nm In0.04Ga0.96N, while for the second one (Fig. 1c), we added the 10×[In0.04Ga0.96N(3 nm)/NbN(3 nm)] superlattice and 20 nm In0.04Ga0.96N capping layer. The N, Nb, and In fluxes were the same as for indium-rich NbN growth described in the previous chapter.

The STEM image of the In0.04Ga0.96N/NbN/In0.04Ga0.96N structure is shown in Fig. 5a, demonstrating a continuous layer of NbN between InGaN layers. The HRTEM image in Fig. 5b revealed an atomically sharp bottom interface of the NbN layer. However, at the upper interface, the thickness fluctuations of 1–3 NbN monolayers are visible, even in regions with no twin boundaries. A fast Fourier transform (FFT) (inset in Fig. 5b) confirms the presence of δ-NbN phase. We also noticed a slightly deteriorated quality of the In0.04Ga0.96N grown on the NbN layer and that the NbN layer is locally strained. It can be explained by stacking fault formation which was observed in high-resolution images. Figure 5c shows a STEM image of the next sample (see Fig. 1c). The lower part of the structure, consisting of InGaN/NbN/InGaN, demonstrates a similar quality to that discussed earlier. After 20 nm of InGaN, it was possible to grow an NbN/InGaN superlattice characterized by sharp interfaces in the initial periods. However, in the case of the few last upper NbN/InGaN layers, a deterioration in the quality of the superlattice was observed, manifested by thickness fluctuations in individual layers, particularly in the NbN.

a STEM image of NbN layers grown between In0.04Ga0.96N layers under In-rich conditions with corresponding high-resolution TEM image presented in part (b). The inset shows FFT from the NbN layer. c STEM image demonstrating NbN/InGaN superlattice grown on top In0.04Ga0.96N layer and overgrown by In0.04Ga0.96N cap layer. All images are taken along the \([11\overline{2}0]\) zone axis.

The STEM image of the NbN/In0.05Al0.95N superlattice (structure shown in Fig. 1d) is shown in Fig. 6a. Using InAlN instead of InGaN improved interfaces with NbN, which in turn allowed the preservation of high-quality superlattice even after growing 10 periods. High-quality interfaces between NbN and InAlN are visible in the HRTEM image in Fig. 6b. The same issues with NbN thickness fluctuations observed in the In0.04Ga0.96N/NbN/In0.04Ga0.96N structure are present. However, growing the InAlN layer on NbN smooths the interfaces, enabling the subsequent NbN layer to grow on the flat InAlN. This ensures that no significant deterioration in the superlattice quality occurs as the number of periods increases. FFTs from δ-NbN and InAlN) layers, shown in Fig. 6c and d, respectively, confirm that both phases retain their cubic (NbN) and wurzite (InAlN) structures. For the growth of cubic NbN on a (0001) wurtzite GaN substrate, the best lattice matching is achieved when NbN adopts the (111) orientation, as previously reported12,27. The subsequent formation of a hexagonal InAlN phase on top of (111)-oriented NbN is a typical behavior observed in nitride systems. While cubic GaN has been successfully grown on cubic substrates such as MgO30 or GaAs31 with a (001) orientation, cubic substrates with a (111) orientation, for example, (111)GaAs32, tend to promote the growth of the wurtzite GaN phase. Consequently, the stabilization of cubic InAlN on (111)-oriented δ-NbN is not expected, which is consistent with our HRTEM analysis.

The high quality of the interfaces may be due to the limited formation of stable intermetallic phases in the Al-In and In-Nb systems33. This enables the growth of both NbN and InAlN under In-rich conditions. Importantly, In-rich conditions appear to be favorable for the growth of both NbN and AlN. In contrast to Al-rich conditions, which are challenging for NbN growth due to the multitude of intermetallic phases in the Nb-Al system33, likely leading to the formation of surface particles, the quality of AlN layers grown under N-rich conditions is also poor34.

We demonstrate the successful epitaxy of InGaN/NbN and InAlN/NbN superlattice by PAMBE. We prove that it is possible to grow thin 3 nm layers while maintaining high crystalline quality. The InAlN/NbN creates more stable heterostructures than InGaN/NbN without visible interface degradation. These findings create the basis for the more demanding growth of JJs.

C. NbN/InAlN/NbN Josephson junctions

The JJ sample was grown under In-rich conditions, for which we expect much lower NbN/InAlN interface roughness. The structure contains NbN (15 nm)/In0.05Al0.95N (3nm)/NbN (15 nm) as presented in Fig. 1e. The TEM images for this structure are shown in Fig. 7. From Fig. 7a it is visible that combining In-rich conditions with thin NbN layers allowed us to obtain JJs with only a 3 nm thick InAlN layer, with no bridges connecting the bottom and upper NbN layers. The HRTEM image in Fig. 7b, shows that both interfaces between InAlN and NbN are mostly flat, with only small fluctuation resulting from 1 to 2 nm deep depressions visible in NbN layer at twin boundaries. Also in high-resolution observations, we did not find any indications for structural bridges between the bottom and upper NbN layers, proving that a 3 nm thick InAlN layer is a sufficient barrier. The phases retained their previously described structures, cubic for NbN and wurtzite for InAlN, as shown in the FFTs in Fig. 7c, d. We emphasize that no indium incorporation within the NbN layers is expected, as evidenced by STEM-EDS mapping of samples grown under In-rich conditions. The analysis revealed no detectable indium signal, neither in the bulk of the NbN layers, nor at twin boundaries or in regions containing structural inclusions (see Fig. 3f).

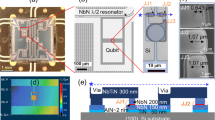

STEM image of an NbN/In0.05Al0.95N/NbN JJ grown under In-rich conditions (a) and the HRTEM showing the interfaces between NbN and In0.05Al0.95N (b). FFT from In0.05Al0.95N (c) and NbN (d) layer indicating wurzite and cubic structure, respectively. e A schematic cross-sectional view of the JJ processed out of the structure shown in (a), along with a top-view microscopic image of the actual device (f).

The I-V characteristics of JJs of dimensions 30 × 30 μm2 (which schematic structure is presented in Fig. 7e with top-view image of the processed device in Fig. 7f) is shown in Fig. 8. We observe supercurrent (Ic) at zero voltage up to 9 mA, which translates to the current density of 1 kA cm-2. This value indicates that our JJs work well for a 3 nm InAlN tunneling barrier and Ic density is in the range reported for NbN junctions obtained by sputtering35,36. Critical supercurrent density values reported in the literature for NbN-based junctions fabricated by sputtering typically range from 1 to 100 kA cm−2 21,35,37. However, such high current densities are generally achieved in devices featuring (1) small mesa areas, typically below 25 μm2, and often less than 10 μm2, (2) an ultra-thin AlN tunneling barrier (1–2 nm)19. Further reduction of the thickness of this barrier should increase the Ic value. We can analyze the JJ parameters using the model proposed for resistively and capacitively shunted junction (RCSJ)38,39. As is shown in Fig. 8a there is almost no hysteresis - return current (IR) is equal to the Ic. It means that our refractory JJs are overdamped, i.e. Stewart-McCumber parameter \({\beta }_{C}=2\pi {I}_{C}{R}_{N}^{2}C\Phi\), where C, RN and Φ are the junction capacitance, resistance and the flux quantum (h/2e), respectively, is lower than 1. We speculate that our JJs are shunted due to the processing - by sidewall effects on mesa structure, but we can not exclude that it can be related to defects created by twin boundaries.

From the I-V curve in the resistive region, we can roughly estimate the resistance of the device in the normal state (from the voltage region above 1.25 mV) to be about RN = 0.3 Ω. The product Ic· RN = 2.7 mV is equal to πΔ/2, where parameter Δ is half of the energy gap of the superconductor. The obtained value of Δ= 1.7 mV (superconducting energy gap—3.4 meV) can be used to estimate of the Tc for NbN. One can get that Tc = 8.7–9.9K (2Δ = 3.52kBTc—BCS theory or 2Δ = 4kBTc in strong coupling limit40), which is in good agreement with directly measured Tc on reference sample—8.8 K (see Fig. 5). The other method to infer the superconducting gap is the voltage onset where system is in normal resistive state— here above 1.25 mV (indicated by the arrow in Fig. 8a) which is also measure of Δ. We also show Ic behavior for different temperatures, which persists up to 7K—see Fig. 8b. We demonstrate the operation of NbN/InAlN/NbN JJs grown by PAMBE which are robust, survive many thermal cooling down/up cycles, with repeatable parameters. We would like to emphasize that there is still room for improvement in the NbN growth process by PAMBE, e.g., increasing Tc and reducing interface fluctuations by growing on miscut substrates, which in turn will influence JJ parameters.

Conclusions

In this work, we show an approach to the growth of δ-NbN/III-N heterostructures on bulk (0001)GaN substrates, where indium was used as a surfactant to improve the structural quality of layers. The most significant finding of our work is the demonstration that using indium as a surfactant enables the growth of III-nitride layers on NbN (as well as NbN itself) without compromising the epitaxial structure, for example, through the formation of In-Nb-N secondary phases. It is known that a metallic indium layer enhances lateral nitrogen diffusion on GaN surfaces, promoting two-dimensional growth in PAMBE. In this study, we show that indium surfactant use (1) enables the growth of thin (In)AlN layers on NbN with smooth interfaces, and (2) improves the growth quality of cubic NbN. We note, however, that growth of cubic NbN on hexagonal GaN still leads to the formation of twin boundaries. In future work, we aim to address this issue by suppressing twin formation, for example, by employing miscut AlN substrates or even m-plane AlN. In addition, the In-rich conditions allowed the growth of thin, high-Al-content (95%) InAlN layers on δ-NbN, as well as to demonstrate (3nm/3nm) NbN/InGaN and NbN/InAlN superlattices. The growth of thin and high structural quality InAlN layer on NbN is particularly interesting for NbN-based JJs. The JJs grown by PAMBE show a high critical current density of 1kA cm-2. It is worth noticing, that the proposed PAMBE process can be applied to growth JJs not only on nitride substrates (GaN, AlN) but also on cubic silicon, making it possible to integrate NbN devices with Si electronics in CMOS foundry. We believe that our findings can open MBE technology for NbN-based qubit devices.

Methods

The investigated samples were grown using a Veeco GEN20 plasma-assisted molecular beam epitaxy (PAMBE) system at a temperature of 650 °C, identical to the conditions typically used for InGaN-based structures, such as laser diodes active regions, grown by PAMBE2. The reported growth temperature corresponds to the actual substrate temperature, determined by indium desorption from the substrate surface using a laser reflectometry system41. The N, Ga, In, and Al fluxes - ΦN, ΦGa, ΦIn, ΦAl, respectively, were determined using standard calibration procedure for III-N growth, while the Nb flux (ΦNb) was established by post-growth thickness measurement of NbN layers.

We compare the growth of NbN (Fig. 1a) under two different growth conditions. The first sample was grown under nitrogen-rich conditions with ΦN=0.45 μm h−1 and ΦNb= 0.15 μm h−1. The second sample was grown under indium-rich conditions using ΦN=0.45 μm h-1, ΦNb= 0.15 μm h−1 and ΦIn=1.2 μm h−1. Samples depicted in Fig. 1(b–e) were grown under indium-rich conditions. For structures shown in Fig. 1(b, c), the fluxes were ΦN = 0.45 μm h−1, ΦNb=0.15 μm h−1, ΦGa=0.434 μm h−1, and ΦIn=1.2 μm h−1. To achieve In0.04Ga0.96N layers, the Ga flux was adjusted to remain slightly below the N flux–the difference between these fluxes dictates the maximum indium incorporation during growth of InGaN layers2. For the structures shown in Fig. 1(d, e), the applied fluxes were ΦN=0.45 μm h−1, ΦNb=0.15 μm h−1, ΦAl=0.118 μm h−1 and ΦIn=1.2 μm h−1. The In content in the InAlN layers was limited by the growth temperature. The compositions of the InGaN and InAlN layers in all samples were confirmed by X-ray diffraction measurements.

Scanning transmission electron microscopy (S/TEM) studies were carried out using FEI TECNAI G2 F20 S-TWIN microscope operated at 200 kV, equipped with Fischione MODEL 3000 high-angle annular dark field detector (HAADF). High-resolution STEM (HR-STEM) images and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) maps were acquired using a Cs-corrected Thermo Fisher Scientific Spectra 200 operated at 200 kV. TEM cross-section specimens were prepared by mechanical polishing on diamond lapping films, followed by argon ion milling at energies decreasing from 4 to 0.4 keV in a Gatan PIPS system.

JJs structures were processed by a standard lift-off photolithography process using a laser writer. First, mesa was defined and etched using chlorine inductively coupled plasma reactive ion etching (ICP RIE) to a depth of 20 nm, reaching the middle of the bottom NbN layer. After the photoresist was removed, 100 nm SiO2 isolation was deposited and a second photolithography process was carried out to open the windows for the deposition of Ti/Al/Ni/Au (30/60/40/75 nm) top and bottom contact. SF6 was used to locally etch away the isolation, and finally, the photoresist was removed. The metallic contacts were not annealed.

Electrical characterization of NbN layers was performed by four contact method using DC current source Keithley 6221 and DC nano-voltmeter Keithley 2182A. For the I-V characteristics of JJs, the current and voltage wires were bonded to the metal contacts of the JJs.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yan, R. et al. GaN/NbN epitaxial semiconductor/superconductor heterostructures. Nature 555, 183–189 (2018).

Skierbiszewski, C. et al. Nitride-based laser diodes grown by plasma-assisted molecular beam epitaxy. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 47, 073001 (2014).

van Deurzen, L. et al. Using both faces of polar semiconductor wafers for functional devices. Nature 634, 334–340 (2024).

Jena, D. et al. The new nitrides: layered, ferroelectric, magnetic, metallic and superconducting nitrides to boost the GaN photonics and electronics eco-system. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 58, SC0801 (2019).

Wright, J. G., Chang, C. S., Muller, D. A., Xing, H. G. & Jena, D. Structural and electronic properties of NbN/GaN junctions grown by molecular beam epitaxy. APL Mater. 10, 1900567 (2022).

Kobayashi, A., Maeda, T., Akiyama, T., Kawamura, T. & Honda, Y. Sputter epitaxy of transition metal nitrides: advances in superconductors, semiconductors, and ferroelectrics. Phys. Status Solidi (A) 2400896 (2025).

Keskar, K. S., Yamashita, T. & Onodera, Y. Superconducting transition temperatures of R. F. sputtered NbN films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 10, 370 (1971).

Hatano, M., Nishino, T. & Kawabe, U. Effects of thermal annealing on superconducting Nb and NbN films. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Films 6, 2381–2385 (1988).

Kalal, S., Gupta, M. & Rawat, R. N concentration effects on structure and superconductivity of NbN thin films. J. Alloy. Compd. 851, 155925 (2021).

Carter, W. & Cukauskas, E. Thermal annealing of RF sputtered NbN. IEEE Trans. Magn. 23, 847–850 (1987).

Treece, R. E. et al. New phase of superconducting NbN stabilized by heteroepitaxial film growth. Phys. Rev. B 51, 9356–9359 (1995).

Wright, J. G., Xing, H. G. & Jena, D. Growth windows of epitaxial NbNx films on c-plane sapphire and their structural and superconducting properties. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 074803 (2023).

Katzer, D. S. et al. Molecular beam epitaxy of transition metal nitrides for superconducting device applications. Phys. Status Solidi (A) Appl. Mater. Sci. 217, 1900675 (2020).

Wang, G.-Y. et al. Atomically flat superconducting NbN thin films grown on SrTiO3 (111) by plasma-assisted MBE. APL Mater. 5, 126107 (2017).

Gol’tsman, G. N. et al. Picosecond superconducting single-photon optical detector. Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 705–707 (2001).

Sam-Giao, D. et al. High-quality NbN nanofilms on a GaN/AlN heterostructure. AIP Adv. 4, 107123 (2014).

Nakamura, Y. et al. Superconducting qubits consisting of epitaxially grown NbN/AlN/NbN Josephson junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 212502 (2011).

Kihira, S., Kobayashi, A., Ueno, K. & Fujioka, H. Reduction of twin boundary in NbN films grown on annealed AlN. Crystal Growth Design 22, 1720–1723 (2022).

Wang, Z., Terai, H., Kawakami, A. & Uzawa, Y. Interface and tunneling barrier heights of NbN/AlN/NbN tunnel junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 75, 701–703 (1999).

Sun, R., Makise, K., Zhang, L., Terai, H. & Wang, Z. Epitaxial NbN/AlN/NbN tunnel junctions on Si substrates with TiN buffer layers. AIP Adv. 6, 065119 (2016).

Wang, Z. et al. High-quality epitaxial NbN/AlN/NbN tunnel junctions with a wide range of current density. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 142604 (2013).

Zhuang, Q., Lin, W. & Kang, J. Effect of In-ADlayer on AlN (0001) and (000-1) polar surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C. 113, 10185–10188 (2009).

Jia, H. et al. Effects and mechanisms of In surfactant on high Al-content AlGaN grown by plasma-assisted molecular beam epitaxy. Opt. Express 30, 1782 (2022).

Monroy, E. et al. Surfactant effect of In for AlGaN growth by plasma-assisted molecular beam epitaxy. J. Appl. Phys. 93, 1550–1556 (2003).

Sawicka, M. et al. Role of high nitrogen flux in InAlN growth by plasma-assisted molecular beam epitaxy. J. Crystal Growth 544, 125720 (2020).

Neugebauer, J. et al. Adatom kinetics on and below the surface: the existence of a new diffusion channel. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 056101 (2003).

Chang, H. W. et al. Dense rotational twins in superconducting (111)-orientated δ-NbN epitaxial films on 4H-SiC substrates. Superconduc. Sci. Technol. 34, 045019 (2021).

John, P. et al. ScN/GaN(1100): a new platform for the epitaxy of twin-free metal-semiconductor heterostructures. Nano Lett. 24, 6233–6239 (2024).

Chèze, C. et al. In/GaN(0001)- (3 × 3)R30° adsorbate structure as a template for embedded (In, Ga)N/GaN monolayers and short-period superlattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 072104 (2017).

Powell, R. C., Lee, N. E., Kim, Y. W. & Greene, J. E. Heteroepitaxial wurtzite and zinc-blende structure GaN grown by reactive-ion molecular-beam epitaxy: Growth kinetics, microstructure, and properties. J. Appl. Phys. 73 (1993).

Okumura, H. et al. Growth and characterization of cubic GaN. J. Crystal Growth 178 (1997).

Okumura, H., Misawa, S. & Yoshida, S. Epitaxial growth of cubic and hexagonal GaN on GaAs by gas-source molecular-beam epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 59, 1058–1060 (1991).

The Materials Information Society. ASM Handbook Volume 3—Alloy Phase Diagrams (1992).

Wright, J.Growth and applications of epitaxial transition metal nitride thin film heterostructures. Ph. D. thesis, Cornell University (2022).

Wang, Z., Kawakami, A., Uzawa, Y. & Komiyama, B. High critical current density NbN/AlN/NbN tunnel junctions fabricated on ambient temperature MgO substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 64, 2034–2036 (1994).

Shoji, A., Aoyagi, M., Kosaka, S., Shinoki, F. & Hayakawa, H. Niobium nitride Josephson tunnel junctions with magnesium oxide barriers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 46, 1098–1100 (1985).

Tolpygo, S. K. et al. Properties of unshunted and resistively shunted Nb/AlOx-Al/Nb Josephson junctions with critical current densities From 0.1 to 1 mA/μm2. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 27 (2017).

Stewart, W. C. Current-voltage characteristics of Josephson Junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 12, 277–280 (1968).

McCumber, D. E. Effect of ac impedance on dc voltage-current characteristics of superconductor weak-link junctions. J. Appl. Phys. 39, 3113–3118 (1968).

Thouless, D. J. Strong-coupling limit in the theory of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 117, 1256–1260 (1960).

Siekacz, M. et al. InGaN light emitting diodes for 415 nm-520 nm spectral range by plasma assisted MBE. Phys. Status Solidi (C) Current Topics Solid State Phys. 6, S917–S920 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Science Centre, Poland, within grant 2018/31/B/ST5/03719.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S., P.W., and A.L. established the epitaxial growth procedure. M.C. and P.W. performed the NbN epitaxy process. A.L. and E.G. performed structural analysis of the epitaxial structures. K.N.-S., A.F., and M.H. performed processing of the JJs. K.D. contributed to the electrical measurement. W.C. performed HRSTEM and EDS measurements. A.L. and M.C. visualized the data in the article. A.L., C.S., and M.S. analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript. M.C. and M. Ż. revised the manuscript and provided suggestions. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lachowski, A., Wolny, P., Dybko, K. et al. NbN-based Josephson junctions grown by plasma-assisted molecular beam epitaxy. Commun Mater 6, 169 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00891-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00891-3