Abstract

Amorphous metal oxides are generally thought to be structurally different from metallic glasses because of the different types of bonding, such as ionic, metallic, and covalent. While amorphous metal oxides consist of metal atoms surrounded by oxygen atoms, metallic glasses resemble the dense random packing (DRP) of hard spheres. However, a theory suggests that the two different classes of materials have underlying structural similarities. Here, using angstrom-beam electron diffraction (ABED) and the polyhedron code, we provide experimental support for the theory by presenting evidence that the Hf sublattice in amorphous HfO2 contains atomic clusters dominated by pentagonal bipyramids, DRP’s key structural feature. We further observed remarkable similarities between the Hf sublattice and Zr80Pt20 metallic glass, together with distinct differences from amorphous Si and SiO2, which have open tetrahedral-bond-network structures. These findings pave the way for a deeper understanding of the universality of glass structures and their connection to material properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amorphous structures have been observed in various types of materials, including oxides, metals, and polymers, but a comprehensive understanding of their structural nature remains a central challenge in materials science1. For instance, in silica (SiO2) glass, one of the most common oxides, the amorphous structure is composed of SiO4 tetrahedra as the fundamental units, which are randomly connected by sharing their vertices2,3,4,5,6. In amorphous metal oxides like HfO27,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15, metal atoms are surrounded by oxygen atoms, forming MOx polyhedra, and the structure of amorphous metal oxides is typically understood as a random network of these polyhedra connected by sharing their vertices, edges, or faces. In contrast, metallic glasses16,17,18,19 are generally thought to resemble the dense random packing (DRP) of hard spheres20,21, which was originally introduced by Bernal to understand the structure of liquids. Voronoi polyhedral analysis21,22 of the DRP structure reveals that the atomic arrangement can be described as an assembly of bipyramidal structures, especially with pentagonal bipyramids, which are the most dominant. In the realistic models of metallic glasses, atomic clusters containing a significant number of these pentagonal bipyramids have been proposed as fundamental structural units, and their connectivity has been widely debated16,17,18,19,23,24.

So far, the structures of amorphous metal oxides and metallic glasses have been studied separately, as described above. However, a theoretical study25 suggests a close relationship between the local structures of these different amorphous materials as follows. Amorphous metal oxide consists of a metal sublattice and an oxygen sublattice. When these sublattices are examined separately, each structure is dominated by pentagonal bipyramids and thus resembles the DRP of hard spheres. This theoretical prediction has been supported by ab-initio molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, but experimental verification remains challenging due to the difficulty in directly observing the sublattice structures.

In this paper, we experimentally examine the theoretical prediction using the angstrom-beam electron diffraction (ABED)6,23,24,26,27, which is a technique that allows direct observation of sub-nanometer level structures of amorphous materials. We focus especially on the Hf sublattice of amorphous HfO2 because the significant difference in atomic numbers between Hf and O is expected to enable us to see only Hf atoms. By comparing the experimental and theoretical ABED patterns, we demonstrate that the Hf sublattice contains atomic clusters dominated by pentagonal bipyramids, supporting the theory that the metal sublattices resemble the DRP of hard spheres. Furthermore, we show that the structure of the Hf sublattice in HfO2 is similar to that of Zr80Pt20 metallic glass, particularly in terms of the presence and connectivity of atomic clusters composed mainly of pentagonal bipyramids.

Results

To guide the ABED experiment, we simulated ABED patterns from local atomic configurations of amorphous HfO2. For this purpose, we first prepared ten structural models of amorphous HfO2 with 324 atoms by ab-initio MD simulation and characterized their structures. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, the X-ray structure factor S(Q) calculated from this structural model shows good agreement with the experimental data reported in the literature14. In addition, Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3 show that the partial pair distribution functions (partial g(r)) for Hf-Hf, Hf-O, and O-O pairs and the distribution of Hf-O-Hf bond angles agree with previously reported data14. These results support the reliability of our models. In this work, we focus on only the Hf sublattice, examining the arrangement of Hf atoms while ignoring the O atoms. An example of the Hf sublattice is depicted in Fig. 1a using a space-filling picture. The Hf sublattice is structurally similar to the DRP of hard spheres in that the most dominant bipyramidal structure is the pentagonal bipyramid. Bipyramids assemble to form atomic clusters, and the most dominant atomic cluster in the DRP structure is the docosahedral cluster28. This cluster is also the most dominant in pure liquid metals including Hf29, pure metallic glasses, liquid SmFe12-based alloys30, and a colloid glass28,31,32. The docosahedral cluster is a structure composed of a central atom surrounded by 13 neighboring atoms positioned at the vertices of a 22-faced polyhedron. This cluster is characterized by a Voronoi index of <0, 1, 10, 2> and a polyhedron code (p3 code)33,34 of @4(56)258, which is the abbreviated form of @4565655555555 (Fig. 1b). Both the Voronoi index and the p3 code indicate that this cluster contains 4 square bipyramids, 10 pentagonal bipyramids, and 2 hexagonal bipyramids. Thus, the pentagonal bipyramid is the most dominant. In addition, the p3 code indicates how these structural units are arranged in this cluster. Thus, atomic clusters with different p3 codes have different graph structures. Our ab-initio MD simulations and the p3 code analysis show that docosahedral clusters are also found in the Hf sublattice of amorphous HfO2. In particular, Fig. 1c shows that the docosahedral cluster and the @4526256524645 cluster are the most dominant clusters, each with the same frequency. The @4526256524645 cluster can be derived from a docosahedral cluster through a slight structural modification and is the second dominant cluster in the DRP of hard spheres28.

a Hf sublattice in an ab initio amorphous HfO2 model. b Docosahedral atomic cluster and corresponding Voronoi polyhedron (@4(56)258 and 4(56)258, respectively). c Proportions of the six most frequent p3 clusters in the Hf sublattices of ten 324-atom ab initio amorphous HfO2 models. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Proportions of the six most frequent p3 clusters in the sublattices of ten 324,000-atom classical models made with different cooling rates: d 1.0 × 1015, e 1.0 × 1014, and f 1.0 × 1013 K s−1.

Since ten 324-atom models are insufficient to determine the most dominant cluster in the Hf sublattice, we made ten 324,000-atom models using classical MD simulations with the WCA-MBKS potential, which we made by modifying the Morse-BKS potential35. The results show that the docosahedral cluster is the most dominant cluster in the Hf sublattice of amorphous HfO2. In addition, as shown in Fig. 1d–f, we find that the degree of docosahedral order increases when models are prepared with slower cooling rates (1.0 × 1015, 1.0 × 1014, and 1.0 × 1013 K s−1). Further details of this classical MD model can be found in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figs. 3–5.

We next provide the definitions of the short-range order (SRO) and medium-range order (MRO) of HfO2 as used in this paper, in the context of comparison with metallic glasses. In general, the SRO of metallic glasses can be characterized by atomic clusters composed of a central atom and the atoms that are adjacent to it, while the MRO can be characterized by the ways these clusters are connected. When we focus on the entire HfO2 structure, a docosahedral cluster of Hf atoms can be classified as an MRO structure. This is because Hf atoms are adjacent to O atoms, and not to Hf atoms, within the amorphous HfO2 structure. However, when we focus on the Hf sublattice (Fig. 1a), the same cluster can be regarded as an SRO structure. Since we will compare the structure of the Hf sublattice with that of Zr80Pt20 metallic glass, we refer to a docosahedral cluster of Hf atoms as an SRO structure. We also refer to a structure composed of docosahedral clusters as an MRO structure.

Figure 2a depicts an MRO structure composed of five docosahedral clusters of Hf atoms and the O atoms bonded to the Hf atoms, which is chosen as a representative because the docosahedral cluster is composed mainly of pentagonal bipyramids and is a key structural feature of both the amorphous HfO2 models and the DRP of hard spheres. A simulated ABED pattern from this MRO structure is shown in Fig. 2a’. We point out that this ABED pattern is primarily produced by Hf atoms due to the large difference in electron diffraction intensity between the Hf and O elements. To verify this, we made the hypothetical MRO structure shown in Fig. 2b from the MRO structure of Fig. 2a by removing the O atoms while keeping the arrangement of Hf atoms unchanged. The ABED pattern from this hypothetical structure without O atoms (Fig. 2b’) is almost the same as the pattern from the corresponding structure including O atoms (Fig. 2a’), except for the intensities of the outside spots. This means that the O atoms contribute negligibly to the ABED pattern and that the ABED method enables us experimentally to see only the Hf sublattice in the HfO2 structure. It is thus confirmed that the selection of amorphous HfO2 works effectively for the observation of the metal sublattice of the amorphous structure (also see Supplementary Fig. 6 and Fig. 7).

a Medium-range order (MRO) structure composed of Hf docosahedral (@4(56)258) atomic clusters. The circular dashed line indicates the beam size. a’, Simulated angstrom-beam electron diffraction (ABED) pattern of the model shown in (a). b MRO structure identical to (a), except oxygen atoms are removed. b’ Simulated ABED pattern of the model shown in (b). c Spatially-averaged experimental ABED pattern obtained from an amorphous HfO2 film. d Experimental ABED pattern obtained from a local region of an amorphous HfO2 film.

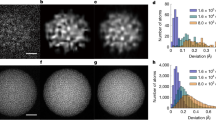

We then conducted a direct experimental detection of the MRO structure of amorphous HfO2. The local diffraction pattern, or the ABED pattern, reflects the arrangement of atoms and its orientation in the probed cylindrical region (approximately 1 nm in diameter and 5 nm in thickness) where the electron beam is irradiated (also see Supplementary Fig. 8). However, when the ABED patterns are superimposed, the resulting average pattern exhibits a halo (Fig. 2c), which is typical of amorphous structures. This suggests that each ABED pattern constitutes a component of the halo pattern. A large number of different ABED patterns were observed from the amorphous thin film (Supplementary Fig. 9), and one of the most characteristic ones (Supplementary Fig. 10) is shown in Fig. 2d. This pattern exhibits a pseudo-sixfold symmetry on the first halo position. The simulated ABED pattern discussed above (Fig. 2a) well reproduces the pseudo-sixfold pattern observed in the experimental ABED pattern. Because of this agreement, our experiment provides evidence that the Hf sublattice of amorphous HfO2 resembles the DRP of hard spheres and the docosahedral cluster of Hf atoms is a key structural feature of amorphous HfO2.

Since the MRO structure consists of docosahedral clusters, which mainly consist of pentagonal bipyramids, it might be puzzling why the pseudo-hexagonal ABED pattern is observed instead of a pentagonal one. The absence of a pentagonal pattern is due to the incoherent orientation of pentagonal structural units. It has been shown that even in the case of a single icosahedral cluster, a pentagonal pattern may not appear depending on the incident angle of the electron beam24. To clarify the origin of the pseudo-hexagonal ABED pattern, we performed a fast Fourier transform (FFT) analysis of the Hf atomic configuration in the MRO region. We then applied inverse FFT (IFFT) filtering using only the six strongest spots that form the pseudo-hexagonal pattern in reciprocal space (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12). Our results show that the origin of the pseudo-sixfold ABED pattern is the formation of the pseudo-triangular lattice seen in the IFFT image. While some atoms contribute to its formation, others do not. However, as a whole, the projections of the atoms in the pentagonal bipyramids form the distorted triangular lattice. The orientation and the distortion of pentagonal bipyramids appear to facilitate its formation.

To validate our structural interpretation, we ruled out the possibility that distinct structures could yield similar ABED patterns. To this end, we first examined amorphous Si. This material has an open structure composed of tetrahedrally bonded Si atoms, which is different from the DRP structure4,36,37. From the structure model of amorphous Si calculated by MD (Fig. 3a), we extracted a local structure (Fig. 3b) and simulated the ABED pattern by rotating the structural model (Fig. 3c). Since the concept of MRO in amorphous Si has not yet been generally established, we avoid using the term MRO for Si in this study. The simulated ABED pattern obtained from a certain orientation exhibits a pseudo-sixfold symmetry. However, unlike HfO2 (Fig. 3d), additional diffraction spots, indicated by red circles, were observed at a lower scattering angle region. Thus, it was found that the ABED pattern of a continuous random network is distinct from that of the DRP-like configuration. A similar result was also obtained from an ABED pattern of amorphous SiO2 (Supplementary Fig. 13 and Fig. 14). These results support our argument that the agreement between the experimental ABED pattern of amorphous HfO2 and the simulated ABED pattern indicates that the Hf sublattice has a DRP-like structure.

a Amorphous Si model simulated using molecular dynamics, together with a Si tetrahedral unit shown in the inset. The coordination analysis reveals that 88.3% of Si atoms are fourfold coordinated, 11.5% are fivefold, and 0.2% are sixfold, indicating that the model is composed mainly of tetrahedrally bonded Si atoms, consistent with low-density amorphous Si produced by rapid quenching. b Local structure extracted from the model shown in (a). c Simulated ABED pattern of the structural model shown in (b). d Experimental ABED pattern of amorphous HfO2 as a reference.

Next we show the similarity between the metal sublattice of amorphous HfO2 and the metallic glass structure, which is considered to be similar to the DRP structure. Figure 4a shows a structural model of the Zr80Pt20 metallic glass24,38,39 with 12,000 atoms obtained by classical MD simulation. The frequencies of six most common atomic clusters in Zr80Pt20 that have a Zr atom at their center are shown in Fig. 4b. The most frequent type of atomic cluster is the docosahedral structure, characterized by the p3 code of @4(56)258, which corresponds one-to-one to the Voronoi index of <0, 1, 10, 2>. This result is similar to the case of the metal sublattice of HfO2 (see Fig. 1c–f). To simulate characteristic ABED patterns of the metallic glass, we extracted an MRO structure consisting of five docosahedral clusters (Fig. 4c), each of which has a Zr atom at the center, from the structure model of Zr80Pt20 metallic glass. Using this structure, we calculated an ABED pattern as shown in Fig. 4d, and this pattern exhibits a pseudo-sixfold symmetry, which resembles that seen in amorphous HfO2 (Fig. 4e).

a Zr80Pt20 model simulated using molecular dynamics. b List of p3-code for the major atomic clusters with central Zr atoms. c MRO structure consisting of docosahedral (@4(56)258) atomic clusters. The circular dashed line indicates the beam size. d Simulated ABED pattern of the model shown in (c). e Experimental ABED pattern of amorphous HfO2 as a reference.

To examine how the atomic clusters are connected in the MRO structure of the Hf sublattice of amorphous HfO2 (Fig. 2a) and in the MRO structure of Zr80Pt20 metallic glass (Fig. 4c), we depict the same atomic configurations viewed from several different orientations in Fig. 5. The atomic configurations of Hf and Zr80Pt20 are shown in Fig. 5a–d and Fig. 5e–h, respectively. Note that the MRO structures for both models consist of five docosahedral clusters, denoted by A, B, C, D, and E, each of which is similarly characterized by @4(56)258 (=<0, 1, 10, 2>). As shown in Fig. 5b, in amorphous HfO2, the clusters B and C are connected by sharing their triangular faces. On the other hand, the clusters A and B interpenetrate each other, where the central atom of one atomic cluster is also included in the other one (Fig. 5c). The interpenetrating connections are also seen among the clusters C, D, and E, where a pentagonal bipyramid is shared by each pair of clusters (Fig. 5d). In addition, the connection of atomic clusters within the MRO structure in Zr80Pt20 metallic glass, including both triangular face-sharing (Fig. 5f) and interpenetration (Fig. 5g, h), is similar to that in amorphous HfO2.

a MRO model of amorphous HfO2 identical to Fig. 2a. Five docosahedral atomic clusters are labeled A to E. b Face-sharing connection between atomic clusters B and C. c Interpenetrating connection between atomic clusters A and B. d Interpenetrating connection among atomic clusters C, D, and E. e MRO model of Zr80Pt20 metallic glass identical to Fig. 4c. f Face-sharing connection between atomic clusters A and C. g Interpenetrating connection between atomic clusters D and E. h Face-sharing connection between atomic clusters A and B, and interpenetrating connection among atomic clusters B and E.

To further examine the structural analogy between amorphous HfO2 and Zr80Pt20 metallic glass, we analyzed the cavities (interstitial space among atoms) in their structures by persistent homology. Specifically, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 15, we computed the second persistence diagrams (PD2), which capture topologically persistent voids in the atomic configurations using HomCloud40. These voids correspond to the “canonical holes” originally proposed by Bernal20,21 in the context of DRP of hard spheres. Interestingly, both amorphous systems exhibit similar PD2 distributions, suggesting a shared topological character in their MRO structure. This result provides a quantitative interpretation of Bernal’s concept and supports the structural analogy between amorphous metal oxides and metallic glasses.

Discussion

The DRP of hard spheres crystallizes easily, because there are no energy barriers to crystallization29. Our analysis shows that amorphous HfO2 and Zr80Pt20 are structurally similar to the DRP of hard spheres, whereas amorphous SiO2 displays a distinctly different structure. SiO2 is known to be an exceptional glass former, whereas HfO2 and Zr80Pt20 exhibit more limited glass-forming ranges. This limitation can be explained as follows: due to their structural similarity to the DRP of hard spheres (docosahedral order), amorphous HfO2 and Zr80Pt20 have low energy barriers to crystallization, resulting in their limited glass-forming ability. We point out that docosahedral clusters also predominate in the liquid and glass states of poor glass formers such as pure metallic glasses29, argon28, and SmFe1230. The pseudo-sixfold symmetry arising from docosahedral clusters in the MRO structures of amorphous HfO2 and Zr80Pt20 may also contribute to their limited glass-forming ability. We note that the absence of docosahedral clusters does not necessarily imply high glass forming ability. In fact, although amorphous Si is structurally different from the DRP of hard spheres, it has limited glass-forming ability. This limited glass-forming ability of Si arises from mechanisms that are not yet understood and differ from those related to structural similarity with the DRP of hard spheres. Although a comprehensive study of the relationship between structure and glass-forming ability is beyond the scope of the present work, our findings support the hypothesis that docosahedral order is an underlying factor that contributes to lowering glass-forming ability30. We believe these findings provide a potential direction for future investigation.

In the literature, the structure of Zr80Pt20 glass is often studied in terms of solute-centered clusters (Pt-centered clusters). In contrast, we have focused on solvent-centered clusters (Zr-centered clusters) in this work. We explain the differences between these two approaches. The structure of Zr80Pt20 glass is similar to that of pure metallic glass, which in turn resembles the DRP of identical hard spheres but differs from it in some respects. The deviation is most apparent in solute-centered clusters. In fact, Pt-centered clusters tend to form an icosahedral structure rather than a docosahedral one. Therefore, analyzing solute-center clusters effectively highlights the structural differences. However, because solvent atoms constitute the majority, the overall structure of Zr80Pt20 glass remains similar to that of the DRP structure. Studying solvent-centered clusters emphasizes this structural similarity.

Concerning the docosahedral order, we note that our previous study28 has demonstrated the following. In the DRP of hard spheres, the most frequently observed Voronoi index is 〈0, 3, 6, 4〉. However, this does not necessarily imply that the corresponding structures are physically meaningful. The high frequency of 〈0, 3, 6, 4〉 arises simply because the Voronoi index method does not distinguish between Voronoi polyhedra with different graph structures. In contrast, the most frequently observed p3 code is @4(56)258, which represents the docosahedral structure. The predominance of the docosahedral structure can be explained as follows. At the length scale of clusters formed by an atom and its neighboring atoms, a regular icosahedral cluster provides the highest local packing density. However, there are inherent gaps between the atoms of the regular icosahedral cluster. When some of these gaps are reduced through local rearrangements, other gaps are inevitably enlarged. Since an additional atom fits into one of these enlarged gaps, a dodecahedral cluster is formed. Since the docosahedral cluster and the icosahedral cluster share structural similarities, the docosahedral cluster is often referred to as a distorted icosahedral cluster. However, the phrase “distorted icosahedral cluster” implies that it is a member of the icosahedral cluster. In contrast, the docosahedron is a 22-faced polyhedron, not a 20-faced one. Therefore, calling the docosahedral cluster a distorted icosahedral cluster constitutes a category error. Terms such as “icosahedral-like cluster” are more appropriate when drawing analogies between the docosahedral and icosahedral clusters. However, in the context of dense random packing, the docosahedral cluster is a key structural feature. Therefore, it is not reasonable to refer to the docosahedral cluster as an icosahedral-like cluster. If anything, the icosahedral cluster is a docosahedral-like cluster.

We also note that our previous study25 has explained the origin of the DRP structure of metal atoms in amorphous metal oxides as follows. Since amorphous metal oxides are ionic solids, covalent bonding effects are not significant in determining their structure. Focusing on the metal sublattice, the primary role of oxygen atoms is to provide countercharges, and their effect can be approximated as a uniform background of negative charge. Therefore, the structure of the metal sublattice can be modeled by considering positively charged metal atoms embedded in a uniform negative background. As the structure of the metal sublattice is governed by spherical Coulomb repulsion, it adopts a DRP structure.

Conclusions

Traditionally, amorphous metal oxides and metallic glasses have been considered distinct fields of materials science. We have provided the first experimental demonstration of the structural similarity between amorphous metal oxides and metallic glasses. This research has also broadened the applicability of the emerging idea that the dodecahedral structure is a central figure for describing the local structure of a wide range of amorphous materials28,29,30. Our discovery bridges different research fields by revealing a hidden common atomic structure in amorphous metal oxides and metallic glasses, allowing for new ideas that combine knowledge from different disciplines.

Methods

Sample preparation

5-nm-thick HfO2 thin films were deposited on very thin amorphous carbon films supported on a copper grid by sputtering a sintered HfO2 target (purity 99%) with a diameter of 101.6 mm. A radio-frequency output power and an argon pressure were 400 W and 0.7–0.8 Pa. Liquid nitrogen was supplied to the reservoir of the top chamber to maintain the substrate temperature below 30 °C during sputtering.

ABED experiment and simulation

We utilized a JEM-2100F TEM/STEM with double spherical aberration correctors (operated at 200 kV) for the ABED measurement. All the ABED patterns were recorded using a CCD camera (Gatan, US1000). A semi-parallel electron beam was produced with a specially designed small-condenser lens aperture with a diameter of 3.5 μm (Daiwa Techno Systems Co., Ltd.). The convergence angle was estimated to be 1.0 mrad with a beam size of 0.8 nm. We obtained a large number of ABED patterns (more than 10,000 frames) from a thin film using a scanning function of the STEM system. The thickness of the films was about 5 nm. The ABED patterns were calculated using the multislice simulation code, which has been described in Ref. 41. The electron accelerating voltage, third-order spherical aberration coefficient, and defocus value were set to 200 kV, 0.005 mm, and 0 nm, respectively. The convergence semiangle of the electron beam was set to 1.0 mrad.

Ab initio model of amorphous HfO2

Ten models of amorphous HfO2 composed of 108 Hf and 216 O atoms were generated using ab initio melt quenching MD simulations. The simulations were performed using the OpenMX software42,43. During the melt quenching simulations, pseudo-atomic basis sets Hf7.0-s3p2d2 and O5.0-s2p2 were used for Hf and O atoms, respectively, and the simulation cell was treated as a cubic cell with a side length of 1.59 nm. After equilibration at 4500 K, each system was cooled to 300 K at a rate of 1 K/fs. Then, the cell was treated as a rectangular cell, and both the atomic configuration and cell dimensions were optimized using pseudo-atomic basis sets Hf7.0-s3p2d2f1 and O5.0-s2p2d1.

Classical model of amorphous HfO2

J. P. Trinastic et al.35 proposed the Morse-BKS (MBKS) potential (\({\varphi }_{{ij}}^{{MBKS}}\)) for HfO2. However, at short interatomic distances, this potential introduces unphysical attractive forces, which can lead to the failure of MD simulations at high temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 5). To overcome this problem, we made the WCA-MBKS potential by adding a repulsive WCA term44 to the MBKS potential as follows:

Here, X and Y each represent an element, either Hf or O. \(K={e}^{2}/4\pi {\varepsilon }_{0}\), where \(e\) is the elemental charge and \({\varepsilon }_{0}\) is the vacuum permittivity. The values of parameters, \(\varepsilon\), \(\sigma\), \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(\gamma\), \(q\), \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\), are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Classical models of amorphous HfO2 were generated by performing melt-quenching MD simulations at zero pressure with the WCA-MBKS potential in LAMMPS45. Different cooling rates, 1.0 × 1013, 1.0 × 1014 or 1.0 × 1015 K s-1, were used. For each cooling rate, ten models were generated. Each model consists of 108,000 Hf and 216,000 O atoms. We first generated a random atomic configuration at 10,000 K and then equilibrated the system at 4500 K. The equilibrated liquid was cooled to 300 K and annealed for 100 ps. Subsequently, the system was further cooled to 1 K at a rate of 1.0 × 1015 K s−1 and again annealed for 100 ps.

Model of amorphous Si

The model of amorphous Si was constructed by using a conventional MD method. Three-body Tersoff-type 46,47 atomic potential was employed. The MD simulation was performed under constant-NVT conditions using a SCIGRESS software. First, 1000 Si atoms with the density of 2.33 g cm−3 was placed randomly in cubic MD cells with periodic boundary conditions. The configuration was kept at 3500 K for 200 ps and then cooled down to 300 K at a cooling rate of 5.0 × 1012 K s−1.

Model of amorphous SiO2

Atomic configurations of amorphous SiO₂ were prepared using a molecular dynamics method. The three-body interatomic potentials for Si–O systems developed by Vashishta et al.48 were employed for the simulation. The simulation was carried out under constant-NVT conditions using LAMMPS45. The initial configuration was based on the β-cristobalite crystal structure, but the density was set to 2.20 g cm-3 to match that of amorphous SiO2. The system was first heated from 300 K to 3500 K, followed by equilibration in the liquid state at 3,500 K. It was then cooled to 300 K at a rate of 1.0 × 1011 K s-1.

Model of Zr80Pt20 metallic glass

Atomic configurations of an amorphous Zr80Pt20 alloy were prepared using a molecular dynamics method. The embedded atom method interatomic potentials for a Zr-Pt system developed by Sheng49 were utilized for the calculation. The simulation was performed under constant-NPT conditions using LAMMPS45. The cubic cell, including randomly distributed 9600 Zr and 2400 Pt atoms with the density of 8.73 g cm-3, was prepared as an initial configuration. The configuration was held at 2000 K for 100 ps and then cooled down to 300 K at a cooling rate of 3.0 × 109 K s−1.

Voronoi tessellation analysis using the p 3 code

We analyzed the atomic configurations by combining Voronoi tessellation and the p3 code34 with the Vorotis software33. In Voronoi tessellation, the space containing atoms is divided into regions called Voronoi polyhedra, each of which contains one atom. When two Voronoi polyhedra share a common face, the atoms within them are considered to be adjacent. A cluster is defined as a central atom and its neighboring atoms. This cluster has a polyhedral shape, with the surface atoms occupying the vertices of a polyhedron. The graph of this polyhedron matches the dual graph of the Voronoi polyhedron enclosing the central atom. The cutoff values used in making Voronoi polyhedra for the Hf sublattice and Zr80Pt20 are 0.76 and 0.50 nm, respectively. Any further increase does not alter the results.

We briefly explain the p3 code using a docosahedral cluster as an example (Fig. 1b). Note that the word ‘docosa’ means 22 and a docosahedral cluster has a polyhedral structure with 22 faces. The p3 code (codeword) is a unique identifier for the graph structure of a cluster, which is based on the one-to-one correspondence between a cluster and the Voronoi polyhedron associated with the central atom of this cluster. The Voronoi polyhedron for the docosahedral cluster is a polyhedron whose graph structure is represented by the code 4565655555555. In this code, each of the characters ‘4’, ‘5’ and ‘6’ represents a square, pentagon, and hexagon, respectively. The sequence 4565655555555 illustrates how these structural units are arranged in the Voronoi polyhedron. Using this code, the docosahedral cluster is represented by @4565655555555. Here, the symbol ‘@’ indicates the one-to-one correspondence between the cluster and its Voronoi polyhedron. Each square, pentagon, and hexagon in the Voronoi polyhedron corresponds to a square, pentagonal, and hexagonal bipyramid in the cluster, respectively. @4565655555555 indicates how the corresponding bipyramids are arranged in the docosahedral cluster. We abbreviate @4565655555555 as @4(56)258.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yang, Y. et al. Determining the three-dimensional atomic structure of an amorphous solid. Nature 592, 60–64 (2021).

King, S. V. Ring configurations in a random network model of vitreous silica. Nature 213, 1112–1113 (1967).

Salmon, P. S., Martin, R. A., Mason, P. E. & Cuello, G. J. Topological versus chemical ordering in network glasses at intermediate and extended length scales. Nature 435, 75–78 (2005).

Kohara, S. et al. Relationship between diffraction peak, network topology, and amorphous-forming ability in silicon and silica. Sci. Rep. 11, 22180 (2021).

Shiga, M., Hirata, A., Onodera, Y. & Masai, H. Ring-originated anisotropy of local structural ordering in amorphous and crystalline silicon dioxide. Commun. Mater. 4, 91 (2023).

Hirata, A. et al. Direct observation of the atomic density fluctuation originating from the first sharp diffraction peak in SiO2 glass. NPG Asia Mater. 16, 25 (2024).

Yan, S. et al. Research advances of amorphous metal oxides in electrochemical energy storage and conversion. Small 15, 1804371 (2019).

Guo, T., Li, L. & Wang, Z. Recent development and future perspectives of amorphous transition metal-based electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2200827 (2022).

Alderman, O. L. G., Skinner, L. B., Benmore, C. J., Tamalonis, A. & Weber, J. K. R. Structure of molten titanium dioxide. Phys. Rev. B 90, 094204 (2014).

Lizárraga, R., Holmström, E., Parker, S. C. & Arrouvel, C. Structural characterization of amorphous alumina and its polymorphs from first-principles XPS and NMR calculations. Phys. Rev. B 83, 094201 (2011).

Lee, S. K., Lee, S. B., Park, S. Y., Yi, Y. S. & Ahn, C. W. Structure of amorphous aluminum oxide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 095501 (2009).

Ceresoli, D. & Vanderbilt, D. Structural and dielectric properties of amorphous ZrO2 and HfO2. Phys. Rev. B 74, 125108 (2006).

Cho, D. Y., Park, T. J., Na, K. D., Kim, J. H. & Hwang, C. S. Structural disorders in an amorphous HfO2 film probed by x-ray absorption fine structure analysis. Phys. Rev. B 78, 132102 (2008).

Gallington, L. C. et al. The structure of liquid and amorphous hafnia. Materials 10, 1290 (2017).

Sivaraman, G. et al. Machine-learned interatomic potentials by active learning: amorphous and liquid hafnium dioxide. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 104 (2020).

Miracle, D. B. A structural model for metallic glasses. Nat. Mater. 3, 697–702 (2004).

Miracle, D. B. The efficient cluster packing model - An atomic structural model for metallic glasses. Acta Mater. 54, 4317–4336 (2006).

Sheng, H. W., Luo, W. K., Alamgir, F. M., Bai, J. M. & Ma, E. Atomic packing and short-to-medium-range order in metallic glasses. Nature 439, 419–425 (2006).

Cheng, Y. Q. & Ma, E. Atomic-level structure and structure-property relationship in metallic glasses. Prog. Mater. Sci. 56, 379–473 (2011).

Bernal, J. D. A geometrical approach to the structure of liquids. Nature 17, 141–147 (1959).

Bernal, J. D. Geometry of the structure of monatomic liquids. Nature 185, 68–70 (1960).

Borodin, V. A. Local atomic arrangements in polytetrahedral materials. Philos. Mag. A 79, 1887–1907 (1999).

Hirata, A. et al. Direct observation of local atomic order in a metallic glass. Nat. Mater. 10, 28–33 (2011).

Hirata, A. et al. Geometric frustration of icosahedron in metallic glasses. Science 341, 376–379 (2013).

Nishio, K., Miyazaki, T. & Nakamura, H. Universal medium-range order of amorphous metal oxides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 155502 (2013).

Hirata, A. et al. Atomic-scale disproportionation in amorphous silicon monoxide. Nat. Commun. 7, 11591 1–7 (2016).

Hirata, A., Ichitsubo, T., Guan, P. F., Fujita, T. & Chen, M. W. Distortion of Local Atomic Structures in Amorphous Ge-Sb-Te Phase Change Materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 205502 (2018).

Nishio, K., Lu, A. K. A. & Miyazaki, T. Entropy-driven docosahedral short-range order in simple liquids and glasses. Phys. Rev. E 99, 022121 (2019).

Nishio, K., Lu, A. K. A. & Miyazaki T. Universal short-range order and material dependent glass-forming ability of metallic liquids and glasses. Phys. Rev. Res. 1, 012013(R) (2019).

Nishio, K., Miyazaki, T., Fukazawa, T., Fukushima, T. & Miyake, T. Liquid structure of SmFe12-based alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 256, 113947 (2025).

van Blaaderen, A. & Wiltzius, P. Real-space structure of colloidal hard-sphere glasses. Science 270, 1177–1179 (1995).

Kurita, R. & Weeks, E. R. Experimental study of random-close-packed colloidal particles. Phys. Rev. E 82, 011403 (2010).

Nishio, K. Vorotis: Software for Voronoi tessellation analysis using the polyhedron code. Comput. Phys. Commun. 278, 108418 (2022).

Nishio, K. & Miyazaki, T. How to describe disordered structures. Sci. Rep. 6, 23455 (2016).

Trinastic, J. P., Hamdan, R., Wu, Y., Zhang, L. & Cheng, H.-P. Unified interatomic potential and energy barrier distributions for amorphous oxides. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 154506 (2013).

Laaziri, K. et al. High resolution radial distribution function of pure amorphous silicon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 3460–3463 (1999).

Biswas, P., Atta-Fynn, R. & Drabold, D. A. Reverse Monte Carlo modeling of amorphous silicon. Phys. Rev. B 69, 195207 (2004).

Mauro, N. A. et al. Short- and medium-range order in Zr80Pt20 liquids. Phys. Rev. B 83, 184109 (2011).

Saida, J. et al. Evaluation of the local environment for nanoscale quasicrystal formation in Zr80Pt20 glassy alloy using Voronoi analysis. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 375104 (2009).

Obayashi, I., Nakamura, T. & Hiraoka, Y. Persistent homology analysis for materials research and persistent homology software: HomCloud. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 91, 091013 (2022).

Kirkland, E. J. Advanced Computing in Electron Microscopy, (Plenum, New York (1998).

Ozaki, T. et al., OpenMX. URL: http://www.openmx-square.org/.

Ozaki, T. Variationally optimized atomic orbitals for large-scale electronic structures. Phys. Rev. B 67, 155108 (2003).

Weeks, J. D., Chandler, D. & Andersen, H. C. Role of repulsive forces in determining the equilibrium structure of simple liquids. J. Chem. Phys. 54, 5237–5247 (1971).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Ishimaru, M. Molecular-dynamics study on atomistic structures of amorphous silicon. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 13, 4181–4189 (2001).

Tersoff, J. Empirical interatomic potential for silicon with improved elastic properties. Phys. Rev. B 38, 9902–9905 (1988).

Broughton, J. Q., Meli, C. A., Vashishta, P. & Kalia, R. K. Direct atomistic simulation of quartz crystal oscillators: Bulk properties and nanoscale devices. Phys. Rev. B 56, 611–618 (1997).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by a JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Areas (A) “Hyper-Ordered Structures Science” Grant No. 20H05881, and a JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research Exploratory Grant No. 23K17837. A.H. gratefully acknowledges the support of Prof. Mingwei Chen. ChatGPT was used exclusively for improving readability. The authors take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.H. and K.N. conceived this study. A.H. performed ABED experiments, ABED simulations, FFT analysis, persistent homology analysis, and classical MD simulations of Zr80Pt20 metallic glass, and amorphous Si and SiO2. K.N. generated ab-initio and classical models of amorphous HfO2 and analyzed their structure. M.O. and R.N. prepared and characterized the thin films. A.H. and K.N. wrote the manuscript, and all the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Harald Rösner and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: John Plummer. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hirata, A., Nishio, K., Okugawa, M. et al. Evidence of underlying structural similarities of amorphous materials. Commun Mater 6, 167 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00894-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00894-0