Abstract

The ongoing push to elevate operating temperatures in aerospace gas turbine engines – driven by goals of enhanced fuel efficiency and reduced CO2 emissions – mandates advancements in the creep resistance of Ni- and Co-based superalloys, which are integral for critical engine components. This study elucidates the role of stress assisted localized phase transformations in the creep properties of these alloys. By leveraging chemo-mechanical coupling, self-healing γ′ precipitates are designed to immobilize planar defects, thereby increasing creep resistance. Employing advanced characterization techniques such as high-resolution Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (HR-STEM), in conjunction with atomistic simulations and thermodynamic calculations, novel deformation pathways facilitated by χ local phase transformation (LPT) strengthening have been uncovered; notably, the formation of χ nano-laths through microtwinning and superlattice intrinsic stacking fault (SISF) shearing. This study highlights critical insights into the compositional boundaries necessary for optimizing LPT strengthening while avoiding deleterious bulk formation of η/χ phases. These advancements will guide the design of new alloys maximizing high-temperature creep strength for advanced aerospace applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is a continual effort to increase the operating temperature of gas turbine engines for aerospace applications, which can yield significantly lower operating costs due to greater fuel efficiency and also decreases harmful CO2 emissions1. Of key importance is creep behavior of Ni- and Co-based superalloys, accounting for almost half the engine weight, used for disks and blades in the hottest sections—the latter tolerating up to 1050 °C2.

High-temperature alloys are typically strengthened via second-phase particles. Most Ni- and Co-based superalloys are strengthened by ordered L12 γ′ precipitates. Under turbine disk service conditions, operating between 650–800 °C, it is well accepted that γ′ shearing by planar defects, i.e. superlattice extrinsic and intrinsic stacking faults SESF and SISF, respectively, and microtwins, dominate creep and low strain rate deformation3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Therefore, to increase the service life of turbine disks this deformation mode must be suppressed. An effective strategy to immobilize these planar defects is to utilize mechanical-chemical coupling during creep deformation to design self-healing γ′ precipitates; shearing and stacking faults are induced via applied load, allowing phase transformations to take place at the faults. Specifically, these are transformations of SESF to η (D024) or SISF to χ (D019), and when occurring in combination have been shown to elevate polycrystals to single crystal creep strength12; however, these local phase transformations (LPT) are detrimental if the phases appear in bulk form, i.e. not contained to a planar defect, as they would reduce creep/fatigue performance. This is due to decreased volume fraction of the main strengthening phase, γ′, resulting from partitioning of γ′ formers to bulk χ/η, in addition to the incompatibility of these ordered HCP phases with γ/γ′ slip systems leading to stress concentrations that promote failure. Therefore, it is of critical importance to design alloys to make LPTs localized to SFs without evolving into bulk forms during continued deformation.

Localized phase transformation has become an active topic explaining both the dynamic evolution of planar defects and how they may be controlled to achieve desired creep properties11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. These LPTs can be divided into LPT-softening or LPT-hardening categories. In LPT-softening, Co and Cr segregation (γ-stabilizing elements) enable SESFs to grow into ever-thickening microtwins. This deleterious process is promoted by LPT-softening at microtwin boundaries. Likewise, SISFs develop into stacking fault ribbons which easily traverse γ′ precipitates. The activity of these two deformation modes depends on grain orientation relative to the stress, and if a compressive or tensile stress is applied9. Regarding LPT-hardening, the stacking faults/twins transform into an ordered phase that is compatible with the atomic template created at the stacking faults and thereby inhibit subsequent shearing. Most LPT studies in Ni-based superalloy literature focus on alloying additions promoting strengthening via η SESFs, with secondary emphasis on χ-strengthening, either via SISFs or microtwins15,19,20,21,22,23,24,25—the later often occurring coincidently due to purposeful alloying for η strengthening. Conversely, χ formation has been a primary focus of LPT strengthening in Co-based alloys as lower anti-phase boundary (APB) energies make SISF/APB/SESF-ribbon shearing more active10,14,17,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Recent work has utilized χ strengthening in Ni-alloy design12,25, but few touch on LPT-strengthened twin boundaries34,35,36. Recent work on alloy RRHT5, aggressively alloyed with Nb, had elucidated an additional strengthening LPT to χ at microtwin interfaces. The formation of this local, ordered χ phase minimized strain accumulation by limiting microtwin thickening to approximately 8 {111} planes, and thus alloy RRHT5 outperformed all other alloys in creep in terms of minimum creep rate (~10−9 s−1), even those for which microtwinning is not active34,36.

All LPTs have a direct relationship with their bulk, often deleterious, counterparts. This is described well in papers by Feng et al.20,37,38. Titus et al.27 pointed out that LPTs, which are one unit cell in one crystallographic direction, deviate from bulk compositions, though are enriched in the same key elements (i.e. LPT-formers). Stability of η/χ are very sensitive to composition as shown both experimentally and by first principle studies20,23,34,36; prediction of LPTs currently relies on CALPHAD databases for bulk η/χ, the accuracies of which have not been fully validated due to their complex multicomponent nature20.

In this work, we investigate effects of alloying elements, temperature, and applied stress on the stability of ordered LPTs, and develop design criteria to promote highly localized LPTs (while preventing bulk-like η/χ formation) by using advanced experimental characterization combining Electron Channeling Contrast Imaging (ECCI) with high-resolution Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (HR-STEM) for structural/chemical analysis, as well as atomistic and CALPHAD calculations. We reveal novel deformation pathways not reported previously in superalloys that are facilitated by χ-LPT strengthening; for the first time, we show that nano-laths of χ form via LPT creep processes associated with microtwinning and SISF shear, and discuss this in relation to composition boundaries that will be important for designing alloys to maximize LPT strengthening. This medium-range LPT has important implications for the hardening and creep behavior of this alloy, as χ nano-laths present barriers to activating multiple slip systems in individual grains during deformation. The stress driven formation process, summarized in Fig. 1c, b, were juxtaposed to classical bulk precipitation, Fig. 1a and described in Supplementary Note 1. Growth mechanisms are proposed for the three atomic layer LPT development to nanoscale laths, distinguishing these from classical isothermal χ formation, and thermodynamic requirements were assessed via density functional theory (DFT) and CALPHAD. These mechanisms have significant implications for Ni- as well as Co-based superalloys, precipitate-strengthened HEAs, and other systems exhibiting LPT35,39.

Summary of the classical (a) as well as newly proposed (b, c) shearing mechanisms leading to χ laths. Horizontal black lines indicate identical, parallel, and adjacent {111} planes viewed edge on (i.e., viewed from \({{{\boldsymbol{ < }}}}\overline{{{11}}}{{0}}{{{\boldsymbol{ > }}}}\) as in STEM observation), whereas the vertical black line on the left represents the γ/γ′ interface. The “L” symbols, and their mirror partners, denote partial dislocations and their color denotes a specific variant relative to the included Thompson Tetrahedron. The light blue dots and circles represent Co/Cr atoms and atmospheres, respectively, whereas the purple dots represent χ stabilizing elements (e.g., Nb and Ta).

Results

Lath formation

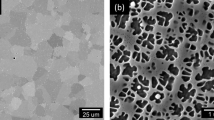

As discussed in our previous work34, the [001]// compression axis (CA) grains are particularly interesting since this orientation in compression is known to favor deformation by microtwinning9,19. In addition, alloy RRHT5 exhibits novel strengthening via microtwin LPT, apparently restricting their average thickness to ~8 {111} planes. Using ECCI analysis, we observed especially bright, thicker traces along the same trace as SFs and microtwins. These were found in crept tension36 and compression34 specimens, with an example shown in Fig. 2; the thickness varied amongst these features and could appear locally thickened (unlike microtwins), as exemplified by the arrows in Fig. 2a. Utilizing ECCI/EBSD, bright lath features were identified in [001]//CA grains, and multiple FIB foils were obtained with \( < {\overline{11}0} > \) normal, enabling viewing {111} fault/twin structures in edge-on orientations. Subsequent STEM-HAADF and energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis were used for structural and compositional analyses.

a SEM-ECCI image of deformation substructure, which is primarily microtwinning after compressive creep at 750 °C/600 MPa with 0.5% deformation (minimum creep rate of ~10−9 s−1). A nano-lath is indicated by the center arrow. b HAADF-STEM image with \({{{\boldsymbol{ < }}}}\overline{{{11}}}{{0}}{{{\boldsymbol{ > }}}}\) beam direction of a bright lath and other defects traversing γ/γ′. c HAADF-STEM image showing HCP region in γ channel and χ in γ′. This lath is not associated with a twin.

It was determined, using correlated lift-out and additional foils from [001]//CA grains, that these were not microtwins but rather distinct nano-laths that traversed both γ and γ′. Remarkably, observation of thermally exposed RRHT5, Supplementary Discussion 1, did not exhibit any lath formation. Low magnification HAADF images of the deformation substructure are presented in Fig. 2b, c. These laths, like planar defects exhibiting LPT, possessed enhanced brightness in γ′ and diminished contrast in γ, indicating they were enriched with heavy elements in γ′ but not in the γ channels.

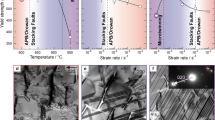

The higher magnification HAADF image in Fig. 3 reveals the atomic structure of laths. These laths exhibited ordered-HCP stacking inside γ′ precipitates (consistent with the structure of χ phase) and disordered HCP stacking in γ (see inset). Additionally, the thicker lath in the center of the image was associated with a microtwin. This was not a unique occurrence as most observed laths in [001]//CA grains were associated with deformation twins. Figure 3 reveals several other features: (c) an SESF that appears to exhibit η-LPT, (d) a twin with a unit cell of η attached to the bottom interface, and (e) a twin-less lath on the top with associated ISF in the γ channel. Note the bleeding of bright contrast from the far left γ′ lath into the γ channel in Fig. 3; this could either be from curvature of the precipitate leading to an inclined interface within the foil thickness or reflected an actual gradient of solute into the γ channel along the lath. This question is addressed in the EDS analysis.

High magnification HAADF-STEM image of (a/b) twin-lath, (c) η-SESF, (d) η-twin, and (e) twin-less lath traversing the γ channel across two precipitates with \({{{\boldsymbol{ < }}}}\overline{{{11}}}{{0}}{{{\boldsymbol{ > }}}}\) beam direction. Dashed orange lines indicate separation between γ′ and γ′ phases.

Figure 4 presents center of symmetry (COS) and Burgers circuit analysis conducted along the twin-associated χ lath (feature a) from Fig. 3 with a schematic of the proposed shearing mechanism; COS analysis reveals HCP-like regions and allows for locations of partial dislocations to be easily observed. The lath ledge shown in Fig. 4b contains a 30° partial dislocation (either \(\frac{1}{6}\left[{\overline{211}}\right]\) or\(\,\frac{1}{6}[12\bar{1}]\)) parallel to the original χ interface, separated by a single \((\bar{1}11)\) plane. Analysis of the Burgers vector was conducted in similar fashion to that by Pandey et al.40.

a Edge on twin-associated χ-lath shown in Fig. 3, b COS analysis and Burgers vector analysis of the ledge step, c magnified inset to determine projected Burgers vector, d possible full Burgers vectors, and e schematic of proposed formation/thickening mechanism. The heat map color scheme indicates deviation from the perfect lattice, where blue is perfect and red shows strong displacement; this highlights regions of HCP-like stacking (planar defects) as well as reveals locations of partial dislocations as to be easily observed.

An additional pathway for formation of a χ nano-lath was observed involving leading ISF/SISF segments preceding the nano-lath, but without an associated twin boundary; this case was seen in Fig. 3e (and below in Fig. 8). COS analysis is shown in Fig. 5, as well as an additional case from a FIB foil extracted from a grain with orientation [111]//CA. It should be noted that these are all associated with an SISF as the initiating defect and thicken by two layers each time shear occurs on parallel {111} planes. Standalone laths were readily observed in both [101]//CA and [111]//CA grains, known to favor formation of SISFs/SF-ribbons9,41. Two SISFs separated by a single {111} plane seem energetically favored as the SISF doublet created has been reported as lower energy than a single SESF or SISF42, and was observed previously in the η/χ LPT forming alloy ME50125. The doublet should also be less energetically costly than shearing either microtwin interface χ or a χ nano-lath, as contextualized later. Importantly, observation of multiple 6-layer χ laths (i.e. SISF doublets) in [101]//CA and [001]//CA, with several examples shown in Figs. 5 and 8 as well as Supplementary Fig. 9, support the hypothesis that the dislocations responsible remain separated by a single {111} plane due to a preference for maintaining local D019 (χ) crystal structure; the doublet is the smallest possible configuration to produce a χ nano-lath.

a COS analysis of topmost feature (e) in Fig. 3 ([001]//CA) at the γ/γ′ interface, b COS analysis of thickening lath from EDS map Fig. 6 traversing the γ/γ′ interface ([001]//CA), and c thickening 10-layer χ lath in γ′ led by an ISF in γ from [111]//CA. The heat map color scheme indicates deviation from the perfect lattice, where blue is perfect and red shows strong displacement; this highlights regions of HCP-like stacking (planar defects) as well as reveals locations of partial dislocations as to be easily observed.

To assess the potential effect of stress on the transformations, Burgers circuit analysis was performed to determine the Burgers vectors associated with the ledge partials. Analysis of the partial in [001]//CA Fig. 5a indicated it to be equivalent, but opposite signed (either \(\frac{1}{6}\left[211\right]\) or \(\frac{1}{6}[\overline{12}1]\)) to the partial determined for the microtwin-associated lath in Fig. 4. The partial observed in Fig. 5b is the highly stressed pure edge \(\frac{1}{6}[\bar{1}1\bar{2}]\). Several remarkable observations were made in the [111]//CA orientation; this foil was rich with non-twin associated laths exhibiting χ-LPT in γ′, with SISF and SESF both observed as well. In one case the tip of a forming/thickening 10-layer χ lath was found arrested at the γ/γ′ interface, an example of which is presented in Fig. 5c. In this case, Burgers circuit analysis revealed the \(\frac{1}{6}[112]\) edge partial, and the continuous intrinsic fault attached suggests that an SISF lead this process.

As differing populations of partial dislocations were observed leading the laths, we present the Schmid factors of relevant Shockley partials for perfectly oriented [101], [001], and [111]//CA crystals in Supplementary Table 1. All the partial dislocations associated with these transformations have significant Schmid factors for their respective grain orientations. These configurations are distinct from those expected for the thermal transformation of χ for which the leading partials when combined have no net Burgers vector, as depicted in Fig. 1a43,44.

STEM EDS analysis of laths

Several laths were chosen for chemical analysis via EDS. The first, Fig. 6, was examined within the center of a γ′ precipitate and enabled assessment of elements contributing to the characteristic, high intensity of the laths relative to adjacent γ′ regions. A line scan traversing the lath and averaging counts along its length were used to quantify segregation. Analysis showed significant increase of Co (+8.4 at%) and Nb (+3.3 at%) at the lath, with typical depletion of Ni (−8.4 at%) and Al (−6.6 at%) observed with LPT. Increases of Ta, W, and Mo (+0.94, +0.25, and +0.94 at%, respectively) were also observed. Compared to 3-layer χ-microtwin LPT34, this presented significantly higher Co, Nb, and Mo (+5.65, +1.3, and +0.94 at%, respectively vs. background γ′ composition); additionally, noticeable increases in Ta/W and Cr are present for the lath unlike χ-microtwins.

Atomic-scale EDS was conducted on the twin-associated lath from Fig. 3 (feature b) to elucidate site preference for elemental species; this is presented in Fig. 7. The data analysis methodology used to produce these figures is reported elsewhere12,34. Complementary analysis of the structure via \( < 1{\overline{12}} > \) was utilized to unambiguously prove that the structure was D019 and is shown in Supplementary Discussion 2. It was determined that Ni and Nb prefer opposing sites, the latter of which is strongly ordered. Co is less strongly positioned on a sublattice but occupies Ni sites in greater quantity than Nb ones. Careful inspection of Ta/W show increased intensity at Nb positions; Mo presents similarly but is more difficult to observe—unit cell line annotations in Fig. 7 are helpful. Unlike the thinner lath observed in the center of a γ′ precipitate (Fig. 6), this lath appears to reject Cr and shows asymmetry in Ni/Al enrichment on either side; however, it appears that the proximity of the γ/γ′ interface is causing apparent enrichment of Cr inside the twin and deficiency of Ni/Al on the γ side, with lack of interfacial ordering compared to the expected χ-microtwin34 preceding this lath. It may be that the lath formation caused dissolution of the preceding γ′ within the twin, causing an atomically sharp interface of χ to form between γ and γ′. When the twin boundary is clearly within a γ′ precipitate (e.g., Fig. 3), it shows χ and superlattice ordering within the attached microtwin indicating lack of significant Cr. The difference in mechanisms between thin, twin-less, and thicker twin-associated laths were already addressed with aid from COS and Burgers circuit analysis; these cases are expected to exhibit similar compositional trends.

Atomic-scale EDS of twin-associated lath from Fig. 3 (feature b). Line annotations are added to guide comparison of atomic positions within the unit cell. Note that the lower interface of the χ lath is bound by a twin which exists in the γ matrix, thus the composition maps are asymmetric above and below the lath. A quantified line scan for this region may be found in Supplementary Fig 7.

Scans of the γ channel were conducted to determine if the HCP regions within γ channels were enriched or otherwise γ-like. Analysis of a standalone lath straddling an edge-on γ/γ′ interface is shown in Fig. 8. This exhibits a thickened 8-layer χ lath within γ′, which is separated by a partial dislocation to a thinner 6 layers of HCP in γ. It was shown previously in Fig. 5b via COS analysis that this change is a result of Shockley partial shear. Figure 8 shows the HAADF image, annotated ROI on an Al/Cr map to show the interface, as well as relevant γ line scans. Only Al, Ni, and Co showed minute fluctuation at the HCP layers in γ: the former two combined to depreciate by the same quantity (within rounding errors) that Co increased (~1.1 at%). Baseline compositions of γ phase were in agreement with prior work34. In the γ′ phase, χ-lath segregation matched trends already reported in Fig. 6. Note also the ledge at the γ/γ′ interface, which may be a diffusion-induced notch from the shearing process.

a HAADF image of a lath thickening across the γ/γ′ boundary, with (b) accompanying Al/Cr spectrum image showing (c) line scan ROIs and relevant γ compositional profiles. Line scans for all alloying elements may be found in Supplementary Fig. 8.

Discussion

Formation mechanisms of χ nano-laths

A microscale view of the χ laths relative to stacking faults and microtwins is offered by ECCI/SEM observations in Fig. 2 for a [001]//CA oriented grain. Primary observations to be gleaned is that the deformation-induced faults and χ laths share the same highly stressed deformation plane, and the χ laths are not observed in other variants, even though these are equivalent relative to the matrix. When coupled with the complete absence of χ laths in the thermally exposed/unstressed condition (Supplementary Discussion 1), these results lead to the conclusion that χ lath formation is strongly stress-assisted. Examination of all ECCI images shows that χ features were not uniformly thick across grains, nor did they emanate from grain boundaries as is typically observed for this phase in bulk form43,45. Partial dislocations which created/thicken twins appeared to shear γ/γ′ continuously from their original source/interface; microtwins exhibited similar thickness for extended distances (~8 {111} planes34), in contrast to the χ laths that nucleate from them, though it appears they both form from dislocation shear on parallel planes. The mechanisms for χ lath formation and growth are schematically summarized in Fig. 1, with thin χ laths associated with both microtwins and ISF/SISFs.

In similar fashion to strengthening LPTs, like those on twin boundaries, SESF, or SISF, χ would be a potent barrier to dislocation shear on the same slip plane which would break ordering of the local phase. For the case of χ nano-laths, this would result in basal plane ({0001}χ) planar defects. These are likely high energy, about 300 \(\frac{{mJ}}{{m}^{2}}\) for APB and 320 \(\frac{{mJ}}{{m}^{2}}\) for CISF in the Ti3Al system, though estimates were not found for Co3W43,46. Energies of χ phase stacking faults are too high to be reasonably formed from a deformation induced process. As such, the only option for dislocations would be to shear adjacent to and thicken χ, as illustrated in Fig. 1 for both (b) microtwin-initiated and (c) SISF-initiated cases. These processes should be quite slow as dislocations in γ would likely need to undergo glide/climb processes to arrange such that they produce shearing configurations at γ/γ′ interfaces47, then traverse via diffusion-mediated process21 through the precipitate to create 2 additional layers of χ.

STEM observations of laths showed local dislocation content interacting with previously formed microtwins to create a locally thicker, faulted region by transformation to HCP/χ; note observations in Fig. 2 show χ laths that thicken from a γ/γ′ interface and extend to another before returning to a microtwin. This suggests that glide of partial dislocations was primarily responsible for thickening χ laths. These partials could normally thicken existing microtwins if not for χ LPT at their interfaces preventing directly adjacent shear on that {111} plane; at some point, the microtwin has reached a critical thickness such that its interfacial χ is mature and has accumulated enough solute that additional partial dislocations cannot pass because of a large energy penalty. Our previous work suggests that the average thickness of microtwins in this alloy is 8 {111} planes, which is likely the critical thickness after which they cannot be thickened further34. Instead, the partials shear on every other {111} plane moving away from the interface, as illustrated in Fig. 1b. This both prevents shearing the initial microtwin-LPT as well as extends χ an additional 2 {111}γ′ (or {0001}χ) planes, which has a low energy penalty due to the interfacial χ nucleus and constant χ/γ′ interfacial area. Note that the ledge characterized in Fig. 4 contained a 30° partial, which according to its Schmid factor has less resolved shear stress than the maximally stressed pure-edge partial (\(\,\frac{1}{6}[\bar{1}2\bar{1}]\)), the latter of which would typically thicken a microtwin boundary. This suggests that χ is on the verge of thermodynamic bulk stability and thus enables the 30° partials to shear through a combination of thermodynamic driving force and input of mechanical energy; while the pure-edge partial was not observed here, it is reasonable that this may also thicken the χ nano-laths with its increased resolved stress. In combination, the tendency to form χ nano-laths instead of further thickening microtwins is a testament to the strengthening capability of microtwin interface χ, as breaking the interfacial ordering seemingly requires significantly more energy.

Regarding the formation of χ in association with SISFs, similar logic would follow. In [101]//CA or [111]//CA grains, such as that shown in Fig. 5c, formation of SISFs is known to be favored9,41. The population of existing SISFs with χ LPT in this alloy36 would provide a nucleation point for nano-laths in a similar fashion to microtwin interface χ; passage of adjacent partials and/or SISFs to create χ would be energetically favored compared to breaking this ordering to create a stacking fault ribbon. In the [111]//CA grain, the highly stressed partial was found on the ledge of a thickened χ lath, which would also be a leading partial of the initial SISF process, suggesting that the same population of partials is responsible. It should be noted that the stress on these partials falls in between the lowest stressed partials of those in [001]//CA (which were found at nano-lath edges) and the highest stressed partials in both [001]//CA and [101]//CA, the latter of which would be responsible for generating initial SESF/twin or SISF populations, respectively. In [001]//CA grains, a highly stressed \(\frac{1}{6}[\bar{1}1\bar{2}]\) edge on partial was found thickening a non-twin associated χ nano-lath, suggesting that these would serve to thicken χ phase. These partials could also naturally serve to thicken microtwin-associated laths. Regarding the lowest stressed partials in [101]//CA grains (see Supporting Table 1), which were not observed, it is unclear whether these can thicken laths or are not able to.

Observation of disordered HCP regions in γ between two ordered χ regions within γ′ is distinctly different from the continuous ordering/composition through both γ and γ′ phases typically observed for bulk η/δ/χ, as reported by others44,45,48,49. Described in detail by Carvalho et al.43,46 for bulk χ formation, disordered HCP regions form at the growing lath tip and become fully segregated/ordered several nanometers behind the tip, and occur through all phases and along all {111} variants. It is necessary for multiple {111} variant systems to be active to reduce net strain and shape change as result of phase formation/growth. In addition, growth faults are observed in bulk χ; energy reduction associated with transformation is likely the driving force for extending faults. This is an important distinction as we only observe extension of faults on one {111} variant system, and extending in the direction of slip, enabling a shape change associated with creep under the applied stress. No faults within χ were observed as are typical for thermally formed bulk χ phase46. In the present work, the extension of faults/χ is promoted by the applied stress, and based on this understanding, a simple analytical model for χ lath formation is presented in Supplementary Discussion 3. Whereas HCP nucleates heterogeneously on existing dislocations or ledges during bulk χ formation, dislocations (and their Shockley partials) at the γ/γ′ interfaces arrange alongside pre-existing twins to form HCP/χ when passing through the precipitate adjacent to a microtwin. In their wake, as seen in Figs. 4 and 5, ordering occurred immediately behind the Shockley partial, as exhibited by other LPTs21. No γ-HCP region has been observed inside a γ′ precipitate.

Titus et al.27 noted that χ-LPT at SISFs deviated in composition from their bulk counterpart and the cause was postulated as a competition between bulk phase stability and interfacial energy. Since microtwin interface χ and χ laths were of different scales, it was of interest to explore whether there is a noticeable difference in χ-formers as a function of lath thickness in the present work. Indeed, EDS of a lath in the center of a γ′ precipitate, Fig. 4, showed increases of Nb, Co, Ta/W, and Mo, vs. microtwin interfaces, suggesting nano-laths tend towards bulk-like χ composition; comparing to previous publication34, microtwin-χ is more enriched with χ-formers than SFs. A notable difference here is that Cr is present, which could further stabilize χ phase or be remnant from prior Cottrell atmospheres surrounding χ-forming Shockley partials50.

DFT calculations related to formation of χ in γ′ and HCP-γ

Observing disordered HCP regions in γ channels has not previously been reported for Ni-based superalloys, and as such DFT calculations were conducted and may be found in Supplementary Discussion 4. Our results show γ-HCP regions are compositionally comparable to bulk γ, varying slightly with higher Co content by ~1 at%. It is notable that the composition of the γ phase is similar to the ternary NiCoCr alloy34, where mechanically-induced HCP-twin lamella form with high strains (>25%) at both cryogenic and room temperatures51. Niu et al.52 have performed a detailed study of all the ternary derivatives of the parent quinary NiCoCrFeMn HEA and observed that NiCoCr is the only ternary with a metastable FCC phase at low temperatures. The high-temperature free energy derived by accounting for vibrational entropy indicates that the phase transition temperature from HCP to FCC is around 950 °C52, which is well above our testing temperatures. Magnetic and electronic entropy contributions to free energy could be significant at high temperatures and are known to suppress the phase transformation to lower temperatures in the quinary alloy53. Further first-principles analysis must be performed to obtain accurate high-temperature free energies of the disordered HCP and FCC γ phases in RRHT5. This is also important for determining the ISF (localized HCP) energy, which plays a vital role in governing mechanical behavior for high-temperature alloys. Nevertheless, it is expected that the free energy difference between FCC and HCP is small at the testing temperature of 760 °C.

First-principles analysis in the current study indicated that the D019 χ phase is slightly less preferred than its L12 counterpart at the same composition. However, the relative energy between the phases is small (~ 3 meV/atom), indicating that formation of χ inside γ′ precipitates could occur under the right circumstances. Several additional studies support the favorability of χ formation inside γ′ precipitates. Hasan et al.54 investigated SISF (locally D019) energies for several Ni3X compositions and observed that relevant solutes in the current study, namely Cr, Mo, Nb, Ta and W, had negative SFE, indicating their preference to segregate to a SISF environment in Ni-based alloys. This agrees with the EDS analysis and is further corroborated by the first-principles segregation analysis in the current study. The only discrepancy is Co, where the SISF energy of Ni3Co was positive. But Rao et al.23 observed that Co would replace Ni at a fault in Ni3Al to reduce the stacking fault energy. Overall, the formation of an SISF inside the γ′ precipitate will drive significant segregation of elements that promote formation of a D019 χ phase.

Implications for alloy design

Based on the LPT mechanism, Feng et al.20 introduced a thermodynamic parameter called ordering tendency, defined as the Gibbs free energy difference between the bulk counterparts of the disordered and ordered stacking fault phases. The more positive the ordering tendency is, the more stable the ordered phase is relative to its disordered counterpart. This parameter is easily evaluated using thermodynamic databases and thus can serve as a parameter in the alloy design process to optimize the LPT hardening effect20. Notably, the normalized ordering tendency for RRHT5 is higher than that for RRHT3, indicating that stacking fault phases in RRHT5 are more ordered, which correlates with its superior creep strength (see Supplementary Fig. 6), as observed in experiments55. However, the formation of nano-lath χ phase in RRHT5 compromises the alloy’s ductility36, necessitating consideration of this effect during the alloy design process.

To include this effect and further understand the differences in nano-lath χ formation between RRHT3 and RRHT5 alloys, we propose another thermodynamic parameter called growth resistance, defined as the Gibbs free energy difference between the bulk counterpart of the stacking fault phases and the γ’ phase. The higher the growth resistance is, the more mechanical work is needed to grow the stacking fault phase into bulk. Thus, this parameter reflects the propensity of the stacking fault phase to grow into the γ’ phase. Figure 9 illustrates both the normalized growth resistance and ordering tendency in the Al and Nb compositional space, encompassing the RRHT3 and RRHT5 alloys. Specifically, the growth resistance for RRHT3 is higher than that for RRHT5, indicating that more mechanical work is required for localized χ stacking fault phases to grow into bulk forms from γ’ in RRHT3 than in RRHT5, i.e., it is easier to form nano-lath χ in RRHT5 than in RRHT3. While higher Nb content enhances the ordering tendency of stacking faults, it also promotes the transition of localized stacking fault phases into the bulk counterpart if the content exceeds a critical value for the given stress and temperature encountered in service. Thus, achieving an optimal composition requires balancing the benefits of ordered stacking faults with the prevention of nano-lath χ formation by considering both the ordering tendency and growth resistance.

Conclusions

In this study the formation mechanisms of χ nano-laths via deformation and LPT were examined in RRHT5. This alloy was previously shown to exhibit another novel LPT on microtwin boundaries and possess better creep strength compared to commercial alloys34,36. Following reaching a threshold of 8 {111} planes thick, these microtwins may evolve into χ nano-laths following a newly discovered deformation pathway. The main conclusions of our current efforts are summarized as follows:

-

(1)

Nano-laths of χ were found to form following creep deformation at 750 °C 600 MPa, but not during thermal exposure for the same time. These nano-laths were structurally HCP in γ and LPT to χ inside γ′ precipitates. Two categories of lath were observed, either with or without an associated microtwin. Observation via \( < 1\overline{12} > \) zone axis unambiguously proves that microtwin LPT and ordered regions of nano-laths are χ phase, as suggested by prior DFT34.

-

(2)

It was determined that shearing of partial dislocations accommodating deformation was responsible for creating the χ nano-laths. For [001]//CA grains (SESF/twinning), these were associated with previously formed microtwins with interfacial χ LPT whereby partials sheared adjacent to the interface, thereby thickening microtwin-χ into a nano-lath. In [101]//CA and [111]//CA orientations, formation depended on arrangement of multiple SISFs to form/propagate, beginning with an SISF doublet (two SISF separated by a single plane).

-

(3)

EDS analysis revealed that χ nano-laths were more heavily enriched with χ-formers (Co, Nb, Ta/W, Mo) than the χ at microtwin interfaces. This indicates a tendency toward the bulk χ composition. Partitioning to and site occupancy within χ was determined via atomic-scale EDS. It was revealed that HCP in γ channels was not compositionally distinct from bulk γ. If treated as a NiCoCr equiatomic, DFT results suggest γ-HCP should be stable at testing temperatures.

-

(4)

Results from our DFT calculations indicate that the energy difference between D019 and L12 phases is very small (~ 3 meV/atom), indicating that nano-laths of χ can occur inside L12 under suitable local stress, as may be appreciated when comparing between non-deformed vs. deformed material with the same thermal cycle. Experimental results have shown the latter has enabled this transformation to occur via input of mechanical driving force.

-

(5)

Another thermodynamic parameter for LPT alloy design called growth resistance was introduced; this serves to find an optimal composition by balancing the propensity for ordered stacking faults with the prevention of bulk phase formation. Due to the low growth resistance of RRHT5, χ nano-laths can grow from the highly ordered stacking fault phases that form.

Methods

Sample preparation

The RRHT5 sample, of composition Ni-18.1Co-14Cr-8Al-5.5Nb-1.5Mo-1Ta-0.8 W (at%), was supersolvus processed at 1170 °C for 1 h and cooled at ~2 °C/s to room temperature, followed by aging at 850 °C for 4 h. Following this, specimens were creep tested at 750 °C 600 MPa to 0.5% strain; testing time was 1100 h with a minimum creep rate of ~10−9 s−1. The composition, microstructure, and creep behavior in both tension and compression are described in previous works34,36.

Deformation characterization

Crept specimens were prepared for scanning electron microscopy utilizing an Allied Multiprep to grind and polish to 0.05 μm colloidal silica finish such that the SEM view was down the compressive axis. Electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD) was conducted in a Thermo Scientific Apreo SEM to determine suitable grains for electron channeling contrast imaging (ECCI) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) analysis. Platinum was used to mark TEM foils normal to \( < \overline{11}0 > \) to examine planar defects edge on and were taken from various grain orientations parallel to the compressive axis (//CA) known to promote distinct behavior, based on both single crystal and polycrystalline studies9,41: [001]//CA foils for SESF/microtwinning behavior, [101]//CA for SISF/APB/SESF Ribbons, as well as [111]//CA. The latter is interesting, as deviation from [001] tensile creep directions (SISF-mode) towards [111] has been shown to increase the propensity for planar defect formation, leading to a faster creep rate56; however, [111] single crystal creep studies have not been conducted regarding LPT effects. Foils were extracted and prepared using an FEI Helios Nanolab Dualbeam 600 focused ion beam (FIB). A Thermo Scientific Titan or probe-corrected Themis at 200 kV were used for STEM analysis and energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS) was conducted using a Super-X EDS system and analyzed with Thermo Scientific VELOX software. Cliff-Lorimer analysis57 was utilized for EDS quantification using Kα energies for Al, Ni, Co, Cr, Ti, Nb, and Mo, while Lα energies were used for Ta and W. Atomic resolution images were taken using the HAADF detector to provide atomic number (Z) contrast58,59,60. ECCI analysis parameters were 20 keV and 0.1 nA using the concentric backscatter (CBS) detector and 5 mm working distance.

Computational methods

First principles calculations

First-principles calculations using density functional theory (DFT) were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation (VASP) Package61,62. The calculations used the pseudopotentials generated using the generalized gradient approximation of Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE) with the exchange-correlation treated using the projector augmented wave (PAW) method62,63. Two types of supercells were used in the current study. A 96-atom supercell formed by stacking six {111} type planes, each containing 16 atoms on a plane, was used for calculating the relative energies and to perform ground state analysis of the HCP and FCC ordered/disordered crystals. The atoms in supercells were decorated using the special quasi-random structure generator from the ATAT package64. A Γ-centered k-point grid of 4 × 4 × 3 with a cutoff energy of 400 eV was used to relax the supercell. The force convergence criteria for ionic steps during relaxation were 0.01 eV/Å, whereas the electronic steps converged to an energy of 10−5 eV. First, the supercells were fully relaxed (ISIF = 3) to converge the atomic positions and lattice constants. Later, a static calculation was performed with convergence criteria of 10−6 eV to obtain accurate energy values. Partial occupancies were treated using the Methfessel-Paxton (order 2) method for relaxation calculations and the tetrahedron method with Blöchl corrections in the static calculations. All the analysis was performed spin-polarized with initial magnetic moments on atoms set to 3.0 μB.

The planar fault energies were analyzed using a 192 atom supercell with twelve {111} planes stacked on each other. The larger supercell is required to minimize any interaction of planar faults across the periodic boundaries. Similar to previous studies of planar faults in L12 structures23, a 3 × 3 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid was used with a cutoff energy of 350 eV. SISFs were introduced into an ordered L12-type supercell by shearing the supercell with a vector of \(\frac{1}{3}[\overline{11}2]\). Relaxation of the faulted supercell was performed in three steps. First, constrained relaxation was performed by fixing the atomic degrees of freedom perpendicular to the fault and relaxing atomic coordinates along the planar defect. Second, the coordinates and lattice perpendicular to the fault were relaxed, while atomic positions were fixed along the two directions along the fault plane. The third step was same as the first with constrained relaxations of atomic coordinates along the planar defect. Symmetry was turned off during the relaxation to let the system achieve its lowest energy state. Other settings for relaxation are the same as mentioned earlier. The SFE is expressed as follows:

where \({E}_{{{\rm{fault}}}}\) and \({E}_{{{\rm{perfect}}}}\) are the total energies of the L12 supercell with and without the stacking fault, respectively, and A is the area of the {111} plane where the stacking fault extends.

Monte Carlo

Elemental segregation to planar faults in the RRHT5 alloy was analyzed using first principles-based Monte Carlo simulations. These simulations were performed on the L12-type ordered 192 atom supercell with an SISF introduced by shearing the lattice, which approximates the local structure of a single microtwin boundary. The supercell contained five elements (Ni, Al, Co, Nb, Ta) based on the composition of the RRHT5 γ’ phase obtained from experiments. Each step of the Monte Carlo attempts to swap two atoms of different types in the supercell. If the energy of the Monte Carlo supercell is reduced (\(\Delta E < 0\)) due to a swap, then the exchange is accepted. Meanwhile, if the energy goes up (\(\Delta E > 0\)) the swap is accepted according to the probability distribution (P) expressed as

where \(\Delta E\) is the change in energy due to a swap via Monte Carlo, and \(\tau\) is the virtual temperature of the simulation. This probability distribution will ensure the simulation is not stuck in a local minima and explores the entire configuration space.

The energy of the supercell during Monte Carlo simulation is obtained using static DFT calculations. To save computational costs, the relaxation of atoms was not allowed during Monte Carlo. The final structure obtained from Monte Carlo was later relaxed using the constrained three-step relaxation methodology described earlier. Convergence criteria for DFT calculations are the same as mentioned earlier for SFE calculations. Furthermore, atomic swaps between two atoms in the bulk (away from the planar defect) were not allowed as they do not contribute to segregation of atoms to/from the fault. Finally, Ni and Al atoms were restricted to A and B sublattices in the A3B crystal. Simulations were performed at a virtual temperature (\(\tau\)) of 500 K. The selected temperature corresponds to the average change in energy of swaps in the supercell. Segregation energy of the supercell was tracked during the Monte Carlo simulation, which is given by the following equation:

where E (segregated supercell) is the energy of the Monte Carlo supercell at an intermediate step/end of the simulation, whereas E (initial supercell) is the energy of the supercell at the beginning of the Monte Carlo simulation, and A is the area of the {111} glide plane for the planar fault.

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed in this work are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Williams, R. E. A. et al. Super-X EDS characterization of chemical segregation within a superlattice extrinsic stacking fault of a Ni-based superalloy. Microsc. Microanal. 21, 493–494 (2015).

Pollock, T. M. & Tin, S. Nickel-based superalloys for advanced turbine engines: chemistry, microstructure and properties. J. Propuls. Power 22, 361–374 (2006).

Rae, C. M. F., Matan, N. & Reed, R. C. The role of stacking fault shear in the primary creep of [001]-oriented single crystal superalloys at 750 °C and 750 MPa. www.elsevier.com/locate/msea (2001).

Knowles, D. M. & Gunturi, S. The role of <112>{111} slip in the asymmetric nature of creep of single crystal superalloy CMSX-4. www.elsevier.com/locate/msea (2002).

Unocic, R. R. et al. Mechanisms of creep deformation in polycrystalline Ni-base disk superalloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 483–484, 25–32 (2008).

Viswanathan, G. B., Karthikeyan, S., Sarosi, P. M., Unocic, R. R. & Mills, M. J. Microtwinning during intermediate temperature creep of polycrystalline Ni-based superalloys: mechanisms and modelling Microtwinning during intermediate temperature creep of polycrystalline Ni-based superalloys: mechanisms and modell. Philos. Mag. 86, 29–31 (2006).

Kovarik, L. et al. Microtwinning and other shearing mechanisms at intermediate temperatures in Ni-based superalloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 54, 839–873 (2009).

Vorontsov, V. A., Voskoboinikov, R. E. & Rae, C. M. F. Shearing of γ′ precipitates in Ni-base superalloys: a phase field study incorporating the effective γ-surface Shearing of c 0 precipitates in Ni-base superalloys: a phase field study incorporating the effective c-surface. Philos. Mag. 92, 608–634 (2012).

Smith, T. M., Unocic, R. R., Deutchman, H. & Mills, M. J. Creep deformation mechanism mapping in nickel base disk superalloys. Mater. High. Temp. 33, 372–383 (2016).

Titus, M. S., Eggeler, Y. M., Suzuki, A. & Pollock, T. M. Creep-induced planar defects in L1 2-containing Co-and CoNi-base single-crystal superalloys. Acta Mater. 82 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2014.08.033 (2014).

Eggeler, Y. M., Titus, M. S., Suzuki, A. & Pollock, T. M. Creep deformation-induced antiphase boundaries in L1 2-containing single-crystal cobalt-base superalloys. Acta Mater. 77 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2014.04.037 (2014).

Smith, T. M. et al. Utilizing local phase transformation strengthening for nickel-base superalloys. Commun. Mater. 2 https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-021-00210-6 (2021).

Viswanathan, G. B. et al. Segregation at stacking faults within the γ’ phase of two Ni-base superalloys following intermediate temperature creep. Scr. Mater. 94, 5–8 (2015).

Titus, M. S. et al. High resolution energy dispersive spectroscopy mapping of planar defects in L1 2-containing Co-base superalloys. Acta Mater. 89 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2015.01.050 (2015).

Smith, T. et al. Segregation and eta phase formation along stacking faults during creep at intermediate temperatures in a Ni-based superalloy. Acta Mater. 100, 19–31 (2015).

Freund, L. P. et al. Segregation assisted microtwinning during creep of a polycrystalline L12-hardened Co-base superalloy. Acta Mater. 123, 295–304 (2017).

Makineni, S. K. et al. On the diffusive phase transformation mechanism assisted by extended dislocations during creep of a single crystal CoNi-based superalloy. Acta Mater. 155, 362–371 (2018).

Barba, D. et al. A thermodynamically consistent constitutive model for diffusion-assisted plasticity in Ni-based superalloys. Int. J. Plast. 105, 74–98 (2019).

Smith, T. et al. Phase transformation strengthening of high-temperature superalloys. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–7 (2016).

Feng, L. et al. Localized phase transformation at stacking faults and mechanism-based alloy design. Acta Mater. 240, 1–13 (2022).

Smith, T. M., Rao, Y., Wang, Y., Ghazisaeidi, M. & Mills, M. J. Diffusion processes during creep at intermediate temperatures in a Ni- based superalloy. Acta Mater. 141, 261–272 (2017).

Smith, T. M. et al. Effect of stacking fault segregation and local phase transformations on creep strength in Ni-base superalloys. Acta Mater. 172, 55–65 (2019).

Rao, Y., Smith, T. M., Mills, M. J. & Ghazisaeidi, M. Segregation of alloying elements to planar faults in γ’-Ni3Al. Acta Mater. 148, 173–184 (2018).

Barba, D., Smith, T. M., Miao, J., Mills, M. J. & Reed, R. C. Segregation-assisted plasticity in Ni-based superalloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 49, 4173–4185 (2018).

Smith, T. et al. Segregation and phase transformations along superlattice intrinsic stacking faults in Ni-based superalloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 49, 4186–4198 (2018).

Eggeler, Y. M. M. et al. Planar defect formation in the γ′ phase during high temperature creep in single crystal CoNi-base superalloys. Acta Mater. 113, 335–349 (2016).

Titus, M. S. et al. Solute segregation and deviation from bulk thermodynamics at nanoscale crystalline defects. Sci. Adv. 2, 1–7 (2016).

Bürger, D., Dlouhý, A., Yoshimi, K. & Eggeler, G. On the stress and temperature dependence of low temperature and high stress shear creep in Ni-base single crystal superalloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 795, 139961 (2020).

Lu, S. et al. Atomic structure and elemental segregation behavior of creep defects in a Co-Al-W-based single crystal superalloys under high temperature and low stress. Acta Mater. 190, 16–28 (2020).

Lenz, M., Wu, M. & Spiecker, E. Segregation-assisted climb of Frank partial dislocations: an alternative route to superintrinsic stacking faults in L12-hardened superalloys. Acta Mater. 191, 270–279 (2020).

Vamsi, K. V. & Pollock, T. M. A new proximate structure for the APB (111) in L12 compounds. Scr. Mater. 182, 38–42 (2020).

León-Cázares, F. D., Schlütter, R., Monni, F., Hardy, M. C. & Rae, C. M. F. Nucleation of superlattice intrinsic stacking faults via cross-slip in nickel-based superalloys. Acta Mater. 241, 118372 (2022).

Kumar Makineni, S. et al. Elemental segregation to antiphase boundaries in a crept CoNi-based single crystal superalloy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scriptamat.2018.07.042 (2018).

Egan, A. J. et al. Local phase transformation strengthening at microtwin boundaries in nickel-based superalloys. Acta Mater. 238, 118206 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Strain localisation and failure at twin-boundary complexions in nickel-based superalloys. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–11 (2020).

Egan, A. J. et al. Effect of Nb alloying addition on local phase transformation at microtwin boundaries in nickel-based superalloys. In The Minerals, Metals & Materials Series (eds. Tin, S. et al.) 640–650 (Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 2020).

Feng, L., Rao, Y., Ghazisaeidi, M., Mills, M. J. & Wang, Y. Quantitative prediction of Suzuki segregation at stacking faults of γ’ phase in Ni-Base superalloys. Acta Mater. 200, 223–235 (2020).

Feng, L. et al. Dynamic localized phase transformation at stacking faults during creep deformation and new criterion for superalloy design. MRS Commun. 12, 991–1001 (2022).

Zhang, X., Yan, H., Zhou, K. & Song, M. Unusual precipitation induced by solute segregation in coherent twin boundary in titanium alloys. Acta Mater. 118466 (2022).

Pandey, P. et al. On the faulting and twinning mediated strengthening and plasticity in a γʹ strengthened CoNi-based superalloy at room temperature. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2023.118928 (2023).

León-Cázares, F. D., Monni, F. & Rae, C. M. F. Stress orientation dependence for the propagation of stacking faults and superlattice stacking faults in nickel-based superalloys. Acta Mater. 199, 209–224 (2020).

Chen, Q. Z., Ngan, A. H. W. & Duggan, B. J. An in-situ TEM study of the L12 to DO19 phase transformation in the intermetallic compound Fe3Ge. Intermetallics 6, 105–114 (1998).

Carvalho, P. A., Bronsveld, P. M., Kooi, B. J. & De Hosson, J. On the fcc→D019 transformation in Co-W alloys. Acta Mater. 50, 4511–4526 (2002).

Karpstein, N. et al. Microscopic mechanism of the L1 2 – D0 19 phase transformation in a Co-base single crystal superalloy. Acta Mater. 282, 120416 (2025).

Makineni, S. K., Nithin, B., Palanisamy, D. & Chattopadhyay, K. Phase evolution and crystallography of precipitates during decomposition of new “tungsten-free” Co(Ni)–Mo–Al–Nb γ–γ′ superalloys at elevated temperatures. J. Mater. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-016-0026-1 (2016).

Carvalho, P., Kooi, B. J. & De Hosson, J. T. M. Identification of planar defects in D019 phases using high-resolution transmission electron microscopy. Philos. Mag. Lett. 81, 697–707 (2001).

Wu, X. et al. On the nucleation of planar faults during low temperature and high stress creep of single crystal Ni-base superalloys. Acta Mater. 144, 642–655 (2018).

Antonov, S., Detrois, M., Helmink, R. C. & Tin, S. Precipitate phase stability and compositional dependence on alloying additions in γ-γ′-δ-η Ni-base superalloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 626, 76–86 (2015).

Detrois, M., Antonov, S., Helmink, R. C. & Tin, S. Precipitate phase stability in γ-γ′-δ-η Ni-base superalloys. JOM 66, 2478–2485 (2014).

Bezold, A. et al. Recovery of superlattice stacking faults at high temperatures. Scr. Mater. 222, 115005 (2023).

Miao, J. et al. The evolution of the deformation substructure in a Ni-Co-Cr equiatomic solid solution alloy. Acta Mater. 132, 35–48 (2017).

Niu, C., LaRosa, C. R., Miao, J., Mills, M. J. & Ghazisaeidi, M. Magnetically-driven phase transformation strengthening in high entropy alloys. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–9 (2018).

Ma, D., Grabowski, B., Körmann, F., Neugebauer, J. & Raabe, D. Ab initio thermodynamics of the CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy: Importance of entropy contributions beyond the configurational one. Acta Mater. 100, 90–97 (2015).

Hasan, H., Mlkvik, P., Haynes, P. D. & Vorontsov, V. A. Generalised stacking fault energy of Ni-Al and Co-Al-W superalloys: density-functional theory calculations. Materialia 9, 100555 (2020).

Lilensten, L., Antonov, S., Gault, B., Tin, S. & Kontis, P. Enhanced creep performance in a polycrystalline superalloy driven by atomic-scale phase transformation along planar faults. Acta Mater. 202, 232–242 (2021).

Heep, L. et al. The effect of deviations from precise [001] tensile direction on creep of Ni-base single crystal superalloys. Scr. Mater. 207, 114274 (2022).

Hoeft, H. & Schwaab, P. Investigations towards optimizing EDS analysis by the Cliff-Lorimer method in scanning transmission electron microscopy. X-Ray Spectrom. 17, 201–208 (1988).

Pennycook, S. J. Z-contrast transmission electron microscopy: direct atomic imaging of materials 1. www.annualreviews.org (2021).

Pennycook, S. J. Z-contrast stem for materials science. Ultramicroscopy 30, 58–69 (1989).

Pennycook, S. J. & Jesson, D. E. High-resolution Z-contrast imaging of crystals. Ultramicroscopy 37, 14–38 (1991).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. American Physical Society. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.59.1758 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Van De Walle, A. et al. Efficient stochastic generation of special quasirandom structures. Calphad 42, 13–18 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation’s DMREF program under grant # 2323717. Electron microscopy was performed at the Center for Electron Microscopy and Analysis (CEMAS) at The Ohio State University. A.J.E. thanks the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for their support during much of the analysis and writing process. L.F. would like to acknowledge the support from the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.J.E. and M.J.M. designed the study. A.J.E. conducted compression experiments and STEM investigations. A.J.E. and M.J.M. analyzed the experimental data and developed the proposed mechanism. N.S.H.G. and M.G. conducted the DFT calculations. L.F. and Y.W. conducted thermodynamic calculations and analysis. S.T. provided the materials. M.J.M., M.G. and Y.W. supervised the project. A.J.E. wrote the paper and all authors contributed to the discussion and revision of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jet-Sing Lee. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Egan, A.J., Gunda, N.S.H., Feng, L. et al. Stress-dependent χ phase transformation in a Ni-based superalloy. Commun Mater 6, 180 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00895-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00895-z