Abstract

To advance carbon neutrality, structural materials for high-pressure hydrogen environments must be designed based on fundamental principles. However, the atomic-scale complexity of random alloys hinders the development of interatomic potentials that can accurately reproduce hydrogen behavior influenced by alloying elements. This study develops a machine-learning interatomic potential (MLIP) for the Ni–Mn–H ternary system by efficiently sampling training data through an active learning strategy that combines atomic-force uncertainty and structural descriptors of diverse atomic environments. Molecular dynamics simulations employing the constructed MLIP quantitatively reproduce the experimentally observed non-monotonic dependence of the hydrogen diffusion coefficient on the Mn content. Two competing Mn-addition effects are found: increased and decreased activation energies from repulsive Mn–H interactions and lattice expansion, respectively, the balance of which shifts with the Mn content and governs the diffusion behavior. This approach enables accurate prediction of hydrogen diffusion in random alloys and provides atomic-level insights into alloying effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In efforts to achieve carbon neutrality and address energy resource depletion, the “hydrogen economy” is developing at an accelerating rate1,2, with various initiatives progressing worldwide3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. A hydrogen society encompasses all stages, from hydrogen production, transportation, storage, and supply to utilization, with notable advancements, particularly for hydrogen utilization4. Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCVs), which employ hydrogen as a fuel and emit no carbon dioxide, are a prominent technology5,12. With the spread of FCVs, the development of hydrogen refueling stations is also progressing13. However, in such systems, specific metal components such as pipes and valves are exposed to high-pressure hydrogen environments. Further, hydrogen can penetrate these materials, potentially reducing their strength and ductility14,15,16,17. This phenomenon is commonly known as “hydrogen embrittlement (HE)”18,19,20,21,22.

Austenitic stainless steels (ASSs) with high austenite stability are primarily used in FCVs and hydrogen-refueling stations23,24. To expand the range of usable materials, recent research has investigated HE behavior in ASSs with varying austenite stabilities. In those studies, the HE behavior was evaluated using either external hydrogen introduced through high-pressure hydrogen gas or internal hydrogen pre-charged into the material by exposure to high-pressure hydrogen gas25,26. Ductility in hydrogen environments decreases with the austenite stability27,28,29,30,31,32. Although extensive research is being conducted on HE in austenitic alloys33,34,35,36,37,38,39, the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood because they vary with the materials, environmental conditions, and loading states. For high-pressure hydrogen environments in particular, atomic hydrogen readily dissolves and diffuses into metals, even at room temperature, causing HE. Therefore, hydrogen solubility and transport (diffusion) in metals must be understood to enable the development of design guidelines for the materials employed in such environments.

Several studies have investigated hydrogen solubility and diffusion coefficients in practical stainless steels under high-pressure hydrogen gas40,41. However, practical alloys contain various alloying elements intended to enhance their corrosion resistance, HE resistance, and phase stability. To eliminate the complexity introduced by other metallurgical factors, Omura et al.42 investigated the effects of certain alloying elements (Fe, Cr, Mn, Mo) on the hydrogen solubility and diffusion coefficients of Ni under high-pressure hydrogen using simple binary Ni–X austenitic alloys. Furthermore, Ito et al.43 semi-quantitatively reproduced the experimental results for hydrogen solubility using density functional theory (DFT) calculations and clarified the action mechanism of the alloying elements. However, the action mechanism of the alloying elements on the hydrogen diffusion coefficient, which is another important factor, has not been reproduced through calculation, nor has it been explained based on calculation results. For pure Ni, nonempirical calculations of hydrogen diffusion coefficients using DFT-based phonon calculations combined with transition state theory have quantitatively reproduced experimental results44. However, DFT-based calculation of the hydrogen diffusion coefficients in alloy systems is not computationally practical, as the various diffusion paths caused by the random atomic positions must be comprehensively assessed. Calculations of hydrogen diffusion coefficients in high-entropy alloys using combinations of DFT-based machine learning models and kinetic Monte Carlo (kMC) simulations have recently been reported45,46. However, for these kMC methods, the diffusion attempt frequency must be provided as a parameter and, thus, the predictions are semi-empirical rather than fully nonempirical45,46. Furthermore, as the results have not been compared with experimental data, the prediction validity remains unclear. In contrast, molecular dynamics (MD) calculations using empirical interatomic potentials for Ni–H, which are constructed while emphasizing consistency with DFT, can reproduce experimental results for hydrogen diffusion coefficients47. However, construction of highly accurate empirical interatomic potentials for the Ni-X-H ternary system, which exhibits magnetism, is difficult48. Recently, machine-learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have been developed for many systems49,50,51,52, including Ni53,54,55, Fe, and their binary systems56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68, which exhibit magnetism. MLIPs have also been applied to analyze hydrogen diffusion in binary systems containing hydrogen69,70,71,72. However, MLIPs have reduced accuracy in the extrapolation region73 and, to the best of our knowledge, no ternary MLIPs that can reproduce hydrogen diffusion behavior in random alloys under diverse atomic environments have been reported. In this study, a MLIP for the Ni–X–H system is developed, and MD simulations are performed using this potential to nonempirically predict hydrogen diffusion coefficients in random alloys. The predictions are verified through comparison with experimental results. Furthermore, a detailed analysis of the simulation results elucidates the effects of the alloying elements on the hydrogen diffusion at the atomic level. In particular, an active learning method is employed for the MLIP construction, in which a commonly used uncertainty-based approach based on atomic forces74 is combined with a structural-feature-based screening process75. This method enables efficient sampling of diverse atomic environments relevant to hydrogen diffusion in alloys, thereby facilitating the construction of a high-accuracy MLIP. However, the MLIP development and subsequent analyses generate substantial computational costs. Therefore, this study focuses on the Ni–Mn alloy system. Although experimental investigations of this system have revealed a nonlinear dependence of the hydrogen diffusion coefficient on the Mn concentration42, the underlying mechanism remains unclear. Thus, this system presents a suitable case for demonstrating the utility of MLIP-based analysis. Notably, the approach adopted in this study is not limited to the Ni–Mn system and is applicable to other random alloy systems. Accordingly, this study presents an approach towards the nonempirical prediction of hydrogen diffusion behavior in random alloys and offers deep atomic-level insights into hydrogen transport. These findings will extend the role of computational materials science in the design of materials for hydrogen environments and support the realization of a carbon-neutral society.

Results and discussion

Overview of MLIP construction using GeNNIP4MD

In this subsection, the construction procedure of the Ni–Mn–H MLIP is outlined. In the subsequent subsections of the Results and discussion section, we demonstrate the accuracy of the developed MLIPs in reproducing the properties of Ni–Mn alloys relevant to hydrogen diffusion and the hydrogen behavior therein, through comparison with DFT calculations. Additionally, we report hydrogen-diffusion coefficients within Ni–Mn alloys determined from MD simulations conducted using the devised MLIPs and compare those coefficients with the experimental values. Based on these computational results, we then revealed, at the atomic scale, the effect of Mn on the hydrogen diffusivity at the atomic scale. Finally, we discuss the potential for further development of the methods and the insights obtained in this study. The method used to calculate the hydrogen-diffusion coefficients via MD simulations, which identifies the atomic environments that should be sampled to construct the MLIP training dataset, is described in the Methods section. The training-dataset generation and the MLIP training process are also described in the Methods section, and details of the DFT settings used for the training-data generation and validation are provided. In this study, we constructed an MLIP for the Ni–Mn–H system that can accurately predict the hydrogen diffusion coefficients; this was achieved using the recently developed GeNNIP4MD software package75, which is an MLIP construction tool. Active learning methods based on the atomic-force uncertainty, which are provided in the DP-GEN software platform74, are widely used for MLIP construction. In GeNNIP4MD, a more sophisticated active learning approach is adopted75, which combines uncertainty-based active learning74 with an additional screening process based on the structural features. GeNNIP4MD likely enables efficient generation of the most compact and appropriate training dataset for a high-accuracy MLIP75. In this study, we employed the DP framework76, which is commonly used in DP-GEN. The current implementation of GeNNIP4MD supports DP framework, including M3GNet77 and CHGNet78. In principle, however, it can also be extended to other potential forms such as the Behler–Parrinello neural network potential (BNNP)79, atomic cluster expansion (ACE)80, moment tensor potential (MTP)81, Gaussian approximation potential (GAP)82, and spectral neighbor analysis potential (SNAP)83. The MLIP construction method using GeNNIP4MD is illustrated in Fig. 1. Following preparation of an initial training dataset, model training and training-data generation processes were iteratively executed until the model achieved sufficient prediction accuracy. The training-data generation process comprised three steps: (1) generation (sampling) of candidate structures, (2) screening of candidate structures via active learning, and (3) DFT labeling of the screened structures to create a labeled training dataset. First, multiple DP models with different initial parameters were trained using the initial training data (Fig. 1b). In the subsequent step, in which the candidate structures were generated (Fig. 1d), one of those DP models (e.g., one of four) was used to perform multiple MD simulations on the target atomic system. For example, long-term annealing under various temperature and pressure conditions was simulated. Hence, a large and diverse set of candidate atomic structures was generated. In the next step, two screening methods were applied to select training-data candidates. First, uncertainty-based screening was performed, through which deviations in the atomic forces predicted by the multiple DP models were evaluated. Structures with deviations within predefined lower and upper thresholds were selected. These thresholds were set to enable appropriate identification of structures for which the model was undertrained and the prediction errors were high. In DP-GEN, the structures selected through this uncertainty-based screening were used directly for labeling. By contrast, the GeNNIP4MD tool further applied structural feature-based screening to the structures already selected by the uncertainty-based method. In detail, the similarities between the uncertainty-selected structures and existing training data were evaluated, and structures with low similarity were preferentially chosen. This dual screening process was expected to yield high-accuracy MLIP construction with fewer iteration cycles and a smaller training dataset using GeNNIP4MD compared to that achieved with DP-GEN75,84. In the subsequent step, i.e., labeling, DFT calculations were performed on the structures selected by both screening methods to generate labeled training data. The DPs were then retrained using both the newly obtained and existing training datasets. The predictive accuracies of the retrained DPs were evaluated, and if necessary, the data generation and model retraining processes were repeated. Following sufficient iterations, the final DP was obtained through training with both the initial and newly added training datasets.

a The cycle begins with the creation of an initial training dataset. b In the training step, four DPs with different initial parameters are trained. c The predictive accuracy of the trained DPs is evaluated. d If the accuracy is insufficient, additional training data are generated to improve the model. First, a diverse and large set of candidate atomic structures is generated using molecular dynamics (MD) with the current DPs. In the subsequent screening step, structures are selected based on the maximum force deviation among the DPs, within a predefined range. This deviation threshold is set to effectively identify poorly learned structures with large prediction errors. The structural similarities of the selected candidates are then evaluated relative to the current training set, and structures with low similarity are chosen for labeling. In the labeling step, density functional theory (DFT) calculations are performed on the selected structures, and the resulting data are added to the training set. This cycle is repeated until a DP with satisfactory accuracy is obtained. (RMSE: root mean square error).

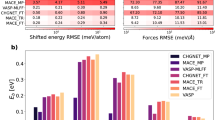

Accuracy of Constructed Deep Potential

Figure 2a and b show the dependence of the Ni lattice constant on the Mn concentration, and the relationship between the lattice constant variation and energy, respectively. As discussed in the following subsection, the changes in the lattice constant induced by the presence of Mn significantly affect the hydrogen diffusion via the activation energy. For the accuracy validation, we employed 2 × 2 × 2 supercells with 32 host metal atoms in the fcc structure. Consequently, each supercell includes 32 octahedral interstitial sites. Here, we employed Ni–Mn alloy configurations with the highest degree of randomness in terms of the correlation functions, to achieve validation for alloy-element arrangements with the maximum possible randomness. The DP predictions agreed well with the DFT results. In particular, the Ni lattice expansion due to Mn addition was accurately reproduced. Figure 2c and d show the hydrogen solution energies at each octahedral site in Ni–12.5 at.% Mn and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn, respectively. These energies served as reference values for the hydrogen-diffusion activation energies. The DPs successfully reproduced the small energy differences in the hydrogen solution energies between sites.

a Effect of Mn concentration on Ni lattice constant. b Relationship between atomic volume and energy in Ni and Ni–Mn alloys. In b, the energy reference is set to the energy at the equilibrium lattice constant of each system. c, d Accuracy of hydrogen-solution energies in Ni–12.5 at.% Mn and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn, respectively. For c and d, no hydrogen molecules are included in the DP training dataset; therefore, the reference energy is not that of an isolated hydrogen atom in a molecule but is, instead, set to the lowest calculated solution energy.

Figure 3a and b show the energy profiles associated with the hydrogen diffusion, which were calculated using the nudged elastic band (NEB) method85,86 (see Methods) with both DP and DFT, respectively, for pure Ni and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn. These energy profiles are the primary factors determining the hydrogen-diffusion activation energy derived from the MD simulations. In the DFT-based NEB calculations, SCF (self-consistent field) convergence for Ni–25 at.% Mn sometimes required several hundred steps, which necessitated the use of a reduced number of images compared to the NEB calculations with DP. The large number of steps required for SCF convergence may be related to the magnetic instability of Ni–25 at.% Mn, where Mn atoms may exhibit either ferromagnetic or antiferromagnetic coupling with surrounding Ni atoms, and the energies of these magnetic states are likely close43. It should be noted that, in the training dataset, all Mn atoms were confirmed to exhibit ferromagnetic coupling.

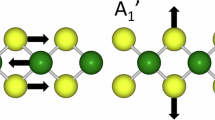

Energy profiles of hydrogen diffusion calculated using a DP and b DFT, for pure Ni and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn, comparing cases where Mn atoms are adjacent to hydrogen at the diffusion barrier site and where they are not. c Local atomic configuration of hydrogen during diffusion in the case of adjacent Mn. The gray, blue, and red spheres represent Ni, Mn, and H atoms, respectively. The gray spheres represent Ni atoms. Here, diffusion occurs from an octahedral site adjacent to two Mn atoms to an octahedral site adjacent to one Mn atom. At the transition state, one of the three neighboring host metal atoms is Mn. d Phonon dispersion of hydrogen atom occupying octahedral site in Ni calculated using DP and DFT. e Phonon dispersion of hydrogen atom occupying octahedral site in Ni–25.0 at.% Mn calculated using DP and DFT. In d and e, the structure corresponds to the stable configuration in which a single Mn atom is adjacent to the hydrogen, as shown on the leftmost side of c.

Figure 3c illustrates the local atomic environment of the hydrogen during diffusion. The hydrogen diffusion proceeded via a tetrahedral site, transitioning from a stable octahedral site to an adjacent octahedral site. Note that the activation energy corresponds to the state in which hydrogen is closest to the three host atoms during the transition between the octahedral and tetrahedral sites; hereafter, this state is referred to as the “transition state.” The hydrogen-diffusion activation energy in pure Ni was well reproduced by the DP, with values of 0.41 and 0.40 eV obtained from the DP and DFT, respectively. For Ni–25.0 at.% Mn, we examined two representative cases in which the effect of Mn became particularly significant, as discussed in detail in the following subsection: (i) one of the three host atoms adjacent to hydrogen in the transition state was Mn and (ii) all three were Ni. In the presence of Mn, the activation energy increased; however, when all three atoms were Ni, the activation energy decreased. The DP accurately reproduced the effects of Mn.

Figure 3d and e show the phonon dispersion relations for pure Ni and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn with hydrogen in solid solution. These plots represent the phonon dispersion for the octahedral sites, which is critical for accurate computation of the pre-exponential of the hydrogen diffusion coefficient44. In the pure Ni, when a hydrogen atom was located at an octahedral interstitial site, the phonon dispersion exhibited a triply degenerate flat band at approximately 24 THz. This result indicates that the hydrogen was weakly bound to the host lattice. The DP results were in excellent agreement with those obtained from the DFT calculations and effectively captured this behavior.

For the Ni–25.0 at.% Mn, the case in which a Mn atom was adjacent to the octahedral site, as shown in Fig. 3c, was considered. The calculations indicated that, in the presence of Mn, hydrogen at the octahedral site exhibited three distinct vibrational modes.This behavior indicated lifting of the degeneracy. As discussed in Supplementary Note 1, for the transition state, the accuracy achieved by the DP in reproducing the Mn-induced effects was lower than that achieved for pure Ni. This lower accuracy may have been due to the increased variety of diffusion pathways in the alloy system compared to that of pure Ni, which made sufficient sampling of the transition states more challenging. Nevertheless, the DP qualitatively reproduced the influence of Mn reasonably well. In summary, the DP developed using GeNNIP4MD successfully reproduced various DFT results, including the lattice constant and associated energy variations in Ni–Mn alloys, hydrogen solution energies and their site dependencies, hydrogen-diffusion activation energies, and phonon dispersions. These results suggest that the obtained DP enables accurate computation of hydrogen diffusivity in Ni–Mn alloys.

Comparison of values calculated using DP and experimental values for hydrogen diffusion coefficients in Ni–Mn alloys

Figure 4a, b, and c show examples of MD simulations of hydrogen diffusion conducted using the developed DP for pure Ni, Ni-10.0 at.% Mn, and Ni-25.0 at.% Mn, respectively. In all systems, a linear relationship existed between time and the mean square displacement (MSD), validating fitting with the Einstein equation (see Methods). Figure 4d presents Arrhenius plots of the diffusion coefficients obtained from the Einstein relation at each temperature. The linearity of these plots validates the approach in which a single activation energy was used for fitting. This consistency also validates the computational conditions and atomic structure models used in the hydrogen diffusion analysis. Similar results were obtained for other chemical compositions; for details, please refer to Supplementary Note 2.

a–c Relationship between annealing time and mean squared displacement (MSD) of hydrogen in a Ni, b Ni–10.0 at.% Mn, and c Ni–25.0 at.% Mn. d Arrhenius plots of hydrogen diffusion coefficients versus 1/kBT for these three systems. e, f Comparison of calculated and experimental effects of Mn content on e activation energy and f pre-exponential factor for hydrogen diffusion in Ni. Experimental results reported by Omura et al.42, Katz et al.87, and Völkl et al.88 are shown for reference.

Figure 4e and f present the obtained hydrogen-diffusion pre-exponential factors and activation energies for each system. For comparison, the experimental results reported by Omura et al.42, Katz et al.87, and Völkl et al.88 are also presented. As regards the activation energy, for the pure Ni, the activation energy obtained from the MD calculations was 0.42 eV, which is in good agreement with the octahedral-to-octahedral activation energy of 0.41 eV shown in Fig. 3. Note that the hydrogen-diffusion activation energy generally corresponds closely to that calculated from NEB analysis44,47. This result further validates the computational settings and structural models used in the MD simulations. The value of 0.42 eV calculated for the Mn-free case is slightly lower than the value of 0.44 eV reported by Omura et al.42; however, the difference is within the range of experimental uncertainty when considering the values reported by Katz et al.87 and Völkl et al.88. Additionally, Wimmer et al.44 theoretically estimated the hydrogen diffusion coefficient in Ni using phonon calculations and transition state theory based on first-principles methods. They estimated that the zero-point vibrations contributed approximately 0.02 eV to the activation energy. This value aligns well with the difference from the experimental result of Omura et al.42, suggesting that the slight deviation in activation energy obtained in the present MD simulations may have arisen because zero-point vibrational contributions cannot be reflected in MD calculations. For the Mn-added systems, the absolute values of the activation energies were slightly lower than the experimental values; however, their variation trend with increasing Mn content was accurately reproduced. Specifically, with the addition of ~10.0 at.% Mn to pure Ni, the activation energy decreased slightly and then increased toward 25.0 at.%, closely reproducing the trend observed in the experiments. Regarding the pre-exponential factors, the computed values agreed well with the experimental results of Omura et al.42. One possible reason for this agreement is that zero-point vibrational effects, which were not explicitly included in the MD calculations, had only a minor influence on the pre-exponential factor44. Furthermore, the nonlinear change in the pre-exponential factor owing to the addition of Mn was accurately reproduced in the simulations. In summary, the DP developed in this study, combined with MD simulations, enabled quantitative reproduction of the influence of Mn addition on hydrogen diffusivity in Ni. In particular, this approach successfully captured the nonlinear effect of Mn content on the hydrogen diffusion coefficient.

Atomic-level mechanism of the effect of Mn addition on hydrogen diffusion in Ni

We explored the atomic-scale mechanism through which Mn addition affects hydrogen diffusion. According to the experimental results of Omura et al.42, the diffusion coefficient near room temperature, which is of industrial importance, is primarily governed by the activation energy. For example, at 270 °C, the hydrogen diffusivity in Ni–25.0 at.% Mn decreases significantly due to the increased activation energy, reaching approximately half that of pure Ni. Therefore, this section focuses on the influence of Mn addition on the hydrogen-diffusion activation energy. As shown in Fig. 3, the presence of adjacent Mn atoms in the transition state can significantly affect the hydrogen-diffusion activation energy. To investigate this effect in detail, we constructed a 4 × 4 × 4 special quasi-random structure (SQS) model89 (see Methods) comprising 256 host metal atoms for Ni–10.0 at.% Mn and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn, which exhibited the minimum and maximum activation energies, respectively. We then calculated the activation energies for all 256 × 8 possible diffusion paths using the DP and NEB methods. Figure 5a shows the activation energy as a function of the number of adjacent Mn atoms in the transition state. In both systems, the activation energy tended to increase with an increasing number of adjacent Mn atoms. This trend can be attributed to the stronger Mn–H core repulsion compared to that of Ni–H at the same bond length43, which is consistent with the fact that Mn has a larger atomic radius than Ni. This repulsive interaction leads to an increase in energy when the Mn atoms are located near the transition state, where the interatomic distances between the host metals become shorter.

a Relationship between number of adjacent Mn atoms and hydrogen-diffusion activation energy in Ni–10.0 at.% Mn and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn. b Relationship between lattice constant and activation energy for zero adjacent Mn atoms. The trend obtained by varying the pure-Ni lattice constant is also shown for comparison. c, d Histograms of activation energies for Ni–10.0 at.% Mn and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn, respectively. The results in panels a–d were obtained from SQS models comprising 256 host metal atoms in a 4 × 4 × 4 supercell. The hydrogen-diffusion activation energy in pure Ni is indicated by dashed lines.

On the other hand, when there were no adjacent Mn atoms at the transition state, the average activation energies were 0.38 and 0.32 eV for Ni–10.0 at.% Mn and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn, respectively, both of which lower than that of pure Ni (0.41 eV). To interpret this result, Fig. 5b shows the relationship between the activation energy and lattice constant when the number of adjacent Mn atoms was zero. This relationship agrees well with the trend observed for pure Ni with various lattice constants. These results indicate that, in the absence of adjacent Mn atoms, the activation energy is reduced is caused by the lattice expansion due to the addition of Mn, which increases the distances between the host atoms and between the host atoms and hydrogen in the transition state, thereby reducing the energy penalty from core repulsion. From these findings, two primary effects of Mn addition on hydrogen diffusion were identified: (i) activation energy reduction due to Ni lattice expansion, and (ii) increased activation energy caused by repulsive Mn–H interactions.

Next, we considered the contribution of these two effects to the hydrogen diffusion behavior. Figure 5c and d show histograms of the hydrogen-diffusion activation energy in Ni–10.0 at.% Mn and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn, respectively. For the Ni–25.0 at.% Mn, the number of diffusion paths occurring with increased activation energy was almost identical to those arising for decreased activation energy, relative to pure Ni. Therefore, selective diffusion of hydrogen over long distances via only those paths in which the activation energy is reduced owing to lattice expansion is difficult. Consequently, the effective activation energy may exceed that of pure Ni. To verify this, Fig. 6 shows one representative case (i.e., the average over eight hydrogen atoms in a single configuration of alloying elements and hydrogen positions) for both pure Ni and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn at 700 K, in which the average MSD is close to the overall average among multiple cases shown in Fig. 4a and c. Figure 6a and b present the time evolution of the path length (cumulative distance traveled) and mean displacement (the square root of the MSD, i.e., the straight-line distance between the initial and final positions) of hydrogen. A temperature of 700 K was chosen because the host-metal thermal vibrations were relatively moderate, which facilitated atomic structure analysis. In both systems, the hydrogen diffusion behavior was well described by a single activation energy value; thus, there was no loss of generality when the analysis was conducted at 700 K. As shown in Figs. 4a and 4c, at 700 K, the MSD and its square root (i.e., the mean displacement) of pure Ni and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn (Fig. 6a) were similar. However, the path length of the latter was longer (Fig. 6b). This outcome indicates that hydrogen tends to follow longer diffusion paths in Ni–25.0 at.% Mn, selecting routes with reduced activation barriers due to the increased lattice constant resulting from Mn addition.

a Time evolution of average hydrogen-atom displacement (i.e., square root of MSD), and b time evolution of hydrogen-atom cumulative path lengths in Ni and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn. Results are shown for a single case at 700 K for which the average displacement closely matched the mean value across multiple cases shown in Fig. 4. c, d Displacements of eight individual hydrogen atoms in case shown in b, for Ni and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn, respectively. e, f Displacements of eight hydrogen atoms in Ni–25.0 at.% Mn, color-coded by number of Mn atoms adjacent to octahedral site occupied by each hydrogen atom at a given time.

Figure 6c and d show the mean displacements of the individual hydrogen atoms. In the pure Ni, monotonic increases in the displacements of almost all hydrogen atoms occurred with increasing annealing time. In contrast, for the Ni–25.0 at.% Mn, although the mean displacements of some hydrogen atoms increased significantly, for the majority of hydrogen atoms, the mean displacements tended to increase gradually with repeated increases and decreases. To further elucidate the influence of Mn on the hydrogen diffusion, the path lengths of each hydrogen atom in Ni–25.0 at.% Mn are shown in Fig. 6e and f, color-coded by the number of adjacent Mn atoms at the octahedral sites through which the hydrogen diffused. These results indicate that most hydrogen atoms underwent diffusion primarily via sites adjacent to Mn atoms, demonstrating that Mn significantly impacts the selection of diffusion pathways. These findings suggest that, in long-range hydrogen diffusion, hydrogen rarely moves exclusively through low-barrier paths. That is, in most cases, hydrogen must also traverse high-barrier paths. This behavior likely contributes to the increased effective activation energy observed in Ni–25.0 at.% Mn compared to that of pure Ni. Moreover, when four Mn atoms are adjacent to an octahedral site, the hydrogen interacts directly with the Mn regardless of the surrounding tetrahedral site to which it attempts to move, yielding a high activation energy and a prolonged stay at that site. Thus, hydrogen trapping at octahedral sites surrounded by adjacent Mn atoms may also contribute to the increase in the effective activation energy caused by Mn addition. As demonstrated above, the addition of Mn induces two opposing effects on the hydrogen-diffusion activation energy: a decrease owing to the Ni lattice expansion, and an increase owing to repulsive Mn–H interactions. Based on simple combinatorial calculations, the fractions of diffusion paths involving adjacent Mn atoms in the transition state were found to be 27.1% and 57.8% for 10.0 at.% Mn and 25.0 at.% Mn, respectively. Thus, the number of paths involving repulsive Mn–H interactions increases with the Mn content. Consequently, for Ni–10.0 at.% Mn, the reduction in activation energy due to lattice expansion dominates, lowering the effective activation energy compared to that of pure Ni. In contrast, for Mn content exceeding 10 at.%, the repulsive Mn–H interactions have a more pronounced effect, and at 25.0 at.% Mn, the effective activation energy increases. Finally, we discuss the effect of the Mn addition on the pre-exponential factor. As mentioned previously, the qualitative behavior of the pre-exponential factor as a function of the Mn content mirrors that of the activation energy. That is, the pre-exponential factor decreases when approximately 10 at.% Mn is added to Ni, and then increases again up to 25.0 at.%, indicating a non-linear trend. Although changes in the lattice constant influence the jump distance (scaling with the square of the lattice parameter), the resulting change in the pre-exponential factor between that of pure Ni and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn is only approximately 4%. This difference is insufficient to explain the observed 1.69-fold increase in the pre-exponential factor. Therefore, the effect of the lattice expansion on the pre-exponential factor via the jump distance is likely limited, with other factors being dominant.

As shown in Fig. 3e, diffusion paths involving adjacent Mn atoms in the transition state cause degeneracy of the octahedral stable site, and the transition state is lifted, which causes the emergence of higher-frequency vibrational modes. However, lattice expansion softens phonon modes, thereby reducing the jump frequency. Qualitatively, these two effects explain the dependence of the pre-exponential factor on the Mn content. However, for a more quantitative discussion, a comprehensive and detailed analysis of the effects of the alloy element distribution on the phonon dispersion is required, which we leave for future work.

Application of findings from this study

This study elucidated the mechanisms through which the addition of Mn affects hydrogen diffusion in Ni. Two primary effects of Mn addition were identified: a decrease in activation energy due to expansion of the Ni lattice constant and an increase in activation energy due to repulsive Mn–H interactions. These two effects are not unique to Mn; rather, they represent general mechanisms exhibited by alloying elements in randomly distributed face-centered cubic (fcc) metals. These insights are valuable for interpreting the influences of various alloying elements on hydrogen diffusion. Omura et al.42 experimentally investigated the effects of Mn and Cr on hydrogen diffusivity, and showed that, at an addition level of 20 at.%, Cr generated a greater increase in the hydrogen-diffusion activation energy than Mn. As Cr and Mn are neighboring elements in the periodic table, with similar core repulsion characteristics, this difference can be interpreted as being due to the smaller lattice expansion effect induced by Cr compared to that of Mn when both elements are at the same concentration. Thus, the findings of the present study can be broadly applied to other alloying elements, to interpret their effects on hydrogen diffusion. In this study, we used GeNNIP4MD to construct an MLIP for the Ni–Mn–H system and demonstrated that the resulting MD simulations successfully reproduced the experimentally observed hydrogen-diffusion trends in Ni–Mn alloys. This study demonstrates the effectiveness of MLIP construction using GeNNIP4MD for metallic materials and illustrates potential applications in computational materials science enabled by the construction of high-accuracy ternary MLIPs. Although our focus was on the Ni–Mn system, the proposed approach is applicable to hydrogen diffusion in a wide range of binary random alloys. Therefore, this technique can potentially predict the effects of alloying elements on hydrogen diffusion in diverse alloy systems, without experimental measurements. At present, MLIP construction and MD simulations based on those MLIPs require considerable computational resources and, in some cases, may even be costlier than experiments. However, as computation performance is continuously improving, this approach is expected to become a powerful tool for the design of hydrogen-resistant materials.

Methods

MLIP-based calculation of hydrogen-diffusion coefficient

Using the MLIP constructed according to the procedure described in the “Overview of MLIP construction using GeNNIP4MD” section, hydrogen-diffusion coefficients were calculated for pure Ni, Ni–7.5 at.% Mn, Ni–10.0 at.% Mn, Ni–12.5 at.% Mn, and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn to span the compositional range reported in the experimental study of Omura et al.42. Diffusion simulations were performed using supercells comprising 2048 host metal atoms, which were created by expanding the conventional fcc unit cell to a size of 8 × 8 × 8, as illustrated in Fig. 7. The OVITO software package90 was used for the atomic structure visualization.

In alloy systems, owing to the constraints on the supercell size and annealing time, the results may depend on the alloying-element arrangement. Therefore, in this study, multiple configurations were used for each composition. To represent random alloy configurations with the maximum possible accuracy, an SQS model89 was employed. This model was also used in previous DFT studies of hydrogen solubility in random Ni alloys43. Note that this method determines near-random atomic arrangements in small supercells based on correlation functions that quantify the randomness. Here, SQSs were generated using the alloy-theoretic automated toolkit (ATAT)91 and its mcsqs code92. The generation criteria employed in this work were adopted from previous studies43,93. Among the many generated SQSs, those with the best correlation function values were selected. For each composition, i.e., Ni–7.5 at.% Mn, Ni–10.0 at.% Mn, Ni–12.5 at.% Mn, and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn, 5, 5, 5, and 6 supercells with SQS-based random alloy configurations were used, respectively. Eight hydrogen atoms were randomly placed at octahedral sites in each supercell to generate the initial structures for the diffusion calculations. This hydrogen content corresponded to approximately 140 wt ppm, which is of the same order as the hydrogen concentration under a hydrogen pressure of 100 MPa employed in the experiment by Omura et al.42. Owing to the high computational cost of the MLIP, the placement of eight hydrogen atoms yielded statistically meaningful results with a limited number of simulations. For the pure Ni, the simulations were performed on 25 different systems with various initial hydrogen configurations. For each Ni-Mn alloy configuration, five different initial hydrogen placements were simulated, which yielded more than 25 combinations for each composition. The simulation conditions were based on a previous study on Ni47, and all calculations were performed under periodic boundary conditions. Temperatures of 700, 750, 800, 850, and 900 K were selected to ensure sufficient hydrogen diffusion and statistical convergence of the diffusion coefficient within the MD simulation duration. First, a 50-ps annealing process was performed using a Nosé–Hoover thermostat at the target temperature, with the pressure controlled at 0 to relax the initial structures. Subsequently, a 1.0-ns annealing process was conducted to enable computation of the diffusion coefficients. A 0.5-fs time step was used. Following the approach of Torres et al.47, the hydrogen-atom MSD during annealing was computed, and the diffusion coefficients at each temperature were obtained using the Einstein relation. Furthermore, the pre-exponential factor and activation energy were derived from Arrhenius plots of the diffusion coefficients against temperature. As discussed in the Results section, the hydrogen diffusion behaviors in all the alloy systems were well described by the Einstein relation across multiple alloy configurations and initial hydrogen placements. The Arrhenius plots revealed linear trends that were well fitted when a single diffusion coefficient was used for each alloy system.

MLIP construction using GeNNIP4MD

To train the DP models on the initial dataset and for each iterative training step, we used DeePMD-kit (version 2.2.8)94. The model architecture and hyperparameters were set based on a previous study on W–H DP construction using DP-GEN95. In detail, we employed DP models using a two-body embedding descriptor (i.e., se_e2_a). The cutoff radius was set to 6.5 Å, the embedding net comprised layers with 20, 40, and 80 neurons, and the number of axis neurons was 16. The fitting network had three hidden layers with 240 neurons each, and the learning rate began at 1×10−3 and decayed to 1.0 × 10−8 over 800,000 training steps. The deep neural network architecture comprised three fully connected hidden layers, each containing 240 neurons, and the activation function was set to a hyperbolic tangent for all hidden layers.

The structures used to construct the initial and additional training datasets were selected to span the atomic environments encountered during MD simulations for hydrogen diffusivity calculations. Specifically, we employed atomic structures from the initial dataset, as listed in Table 1. The initial training dataset comprised three subsets: (1) pure Ni with hydrogen in a solid solution, (2) a random Ni–12.5 at.% Mn alloy with hydrogen in solid solution, and (3) a random Ni–25.0 at.% Mn alloy with hydrogen in solid solution. All these were based on 2 × 2 × 2 supercells with 32 host metal atoms in the fcc structure, into which 0–2 hydrogen atoms were introduced in solid solution. The atomic structures of (2) and (3) were generated using the SQS approach described in the previous section. In the initial dataset, only one random configuration was used for each chemical composition. In addition to the equilibrium volume, structures expanded by 2.0% were also prepared. For each of these, ab initio MD (AIMD) simulations were performed for 200 steps at 600 and 1200 K under constant-volume conditions, and snapshots were extracted at two-step intervals and included in the initial dataset. Similarly, AIMD simulations under NPT conditions were performed at 600 and 1200 K using the equilibrium volumes, and snapshots were again extracted at every step and included in the initial dataset. Furthermore, for the atomic structures in (2) and (3), we placed one hydrogen atom in each of the 32 octahedral sites and performed structural relaxation. Five snapshots were extracted from each relaxation trajectory and included in the dataset. All spin-polarized DFT calculations for the initial dataset were performed under the conditions described in the “Computational details” subsection. The energies, forces, and virial tensors of each structure were computed. As this study aimed to accurately evaluate hydrogen diffusion, additional training data were constructed using structures similar to those of the initial dataset (see Table 1). To generate these additional structures, MD simulations using DPs were conducted using LAMMPS96. For random Ni–12.5 at.% Mn and Ni–25.0 at.% Mn alloys with hydrogen in solid solution, multiple SQS models were generated to sample diverse alloy configurations. Among these, four and nine additional random configurations, respectively, were selected based on the high degrees of randomness in their correlation functions. We also included structures with volumes compressed by 1.0% and 0.5% and expanded by 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, and 2.0%, to reflect the thermally expanded environments relevant to hydrogen diffusion during the MD simulations. Annealing-based sampling was performed on these structures using NVT ensembles at 300, 600, 900, and 1000 K for 50 ps. Owing to the small 2 × 2 × 2 supercell and the instability introduced by the high hydrogen concentrations during long NPT runs, we opted for NVT simulations with fixed volumes. A 0.5-fs time step was used, and structures were extracted every 100 steps as candidate configurations. In these simulations, one of four trained DP models was employed. In the subsequent screening step, for each structure, the maximum deviation in the predicted atomic forces among the four DP models, which were trained with the same hyperparameters but different random seeds, was calculated. Structures with a deviation between 0.10 and 0.25 eV/Å were selected as candidates for labeling. Next, structures for labeling were selected based on their similarities. In detail, multidimensional features extracted from the hidden layers of the DP models were projected onto a two-dimensional space using densMAP97, and the pairwise Euclidean distances between the candidate structures in this 2D space were computed. To enable selection of a fixed number of representative structures, those with shorter distances from others were sequentially removed until the desired number of 900 structures remained in each screening round. The DFT calculations for labeling, including spin polarization, were performed under the same conditions as those described in the Computational Details section for the atomic structures selected through the screening process. The energies, forces, and virial tensors of each structure were calculated.

Following convergence of the GeNNIP4MD iterative workflow, the MLIP was trained for the final time using the accumulated dataset. Twenty iterations were performed. The DP architecture used during the iterations was retained, with only the number of training steps being changed; that is, the training steps were increased to two million. However, no significant improvement in the fitting accuracy was observed compared to the case with 800,000 steps, which confirmed that sufficient convergence during training had already been attained. The final training dataset comprised 17,777 structures (592,435 local atomic environments). As details in Table 1, the root mean square errors (RMSEs) for the energy and force were 5.70 meV/atom and 68.41 meV/Å, respectively, indicating sufficient accuracy. We also tested a hybrid descriptor combining 2- and 3-body (se_e2_a and se_e3, respectively) embedding terms56, following a previous study on W–H DP development95; however, we observed no significant improvement in fitting accuracy (Supplementary Note 3). Therefore, for computational efficiency in MD simulations requiring long timescales and a large number of cases, we employed a 2-body embedded descriptor DP model.

Computational details

Spin-polarized DFT calculations were performed to construct the training dataset and validate the accuracy of the interatomic potential using the projector augmented wave (PAW) method, as implemented in VASP98,99. The exchange-correlation potential was treated using the generalized gradient approximation with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof functional100. The pseudopotentials for Ni and Mn include 4 s and 3 d electrons as valence electrons; these choices were consistent with those used in our previous DFT calculations43. The plane-wave cut-off energy was set to 500 eV. The k-point mesh for each atomic structure was generated using the Monkhorst–Pack scheme101, and was chosen to match the accuracy of an 8×8×8 mesh for the conventional unit cell of Ni. This setup corresponded to a KSPACING of 0.13 in VASP and ensured an accuracy equal to or higher than that adopted in previous studies on MLIP development65,67. For improved convergence, the Methfessel–Paxton smearing method102 with a 0.1-eV smearing width was employed. The convergence criterion for the self-consistent electronic calculations was set to 10−6 eV for the total energy. Structural relaxations were performed until the forces on each atom were less than 10−2eV/Å. All DP-based calculations for accuracy verification were performed using LAMMPS96. AIMD simulations for construction of the initial training dataset were performed using Parrinello–Rahman dynamics103,104 with a Langevin thermostat. A 0.5-fs time step was used in the AIMD simulations. To analyze the hydrogen-diffusion transition states, the transition paths between the initial and final atomic configurations were determined using the climbing-image NEB (CI-NEB) method85,86. Phonon dispersion was calculated using the Phonopy package105,106.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, K.I., upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions imposed by Nippon Steel Corporation; access may be granted only with permission from the company.

Code availability

The main codes utilized in this study—DeePMD-kit94, LAMMPS96—are open-source and can be accessed online, with their licensing information and user manuals detailed in the respective references. GeNNIP4MD75 is proprietary software and is not open-source; however, the code may be made available upon reasonable request. Requests for access should be directed to fj-mi-tech-contact@dl.jp.fujitsu.com.

References

Winsche, W. E., Hoffman, K. C. & Salzano, F. J. Hydrogen: its future role in the nation’s energy economy. Science 180, 1325–1332 (1973).

Ouyang, L., Jiang, J., Chen, K., Zhu, M. & Liu, Z. Hydrogen production via hydrolysis and alcoholysis of light metal-based materials: a review. Nanomicro Lett. 13, 134 (2021).

Yap, J. & McLellan, B. Evaluating the attitudes of Japanese society towards the hydrogen economy: A comparative study of recent and past community surveys. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.05.174 (2023).

Kim, C. et al. Review of hydrogen infrastructure: The current status and roll-out strategy. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48, 1701–1716 (2023).

Peng, Z. et al. Overview of hydrogen compression materials based on a three-stage metal hydride hydrogen compressor. J. Alloy. Compd. 895, 162465 (2022).

Elvira, K. et al. Hydrogen technology for supply chain sustainability: The Mexican transportation impacts on society. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 47, 29999–30011 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. A comprehensive review on hydrogen permeation barrier in the hydrogen transportation pipeline: Mechanism, application, preparation, and recent advances. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 101, 504–528 (2025).

Yu, H. et al. Hydrogen embrittlement as a conspicuous material challenge─comprehensive review and future directions. Chem. Rev. 124, 6271–6392 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Review of the hydrogen embrittlement and interactions between hydrogen and microstructural interfaces in metallic alloys: Grain boundary, twin boundary, and nano-precipitate. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 72, 74–109 (2024).

Meda, U. S., Bhat, N., Pandey, A., Subramanya, K. N. & Lourdu Antony Raj, M. A. Challenges associated with hydrogen storage systems due to the hydrogen embrittlement of high strength steels. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48, 17894–17913 (2023).

Sun, B. et al. Current challenges and opportunities toward understanding hydrogen embrittlement mechanisms in advanced high-strength steels: a review. Acta Metall. Sin. 34, 741–754 (2021).

Pramuanjaroenkij, A. & Kakaç, S. The fuel cell electric vehicles: The highlight review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48, 9401–9425 (2023).

Sasaki, K. et al. Hydrogen energy engineering. (Springer, 2016).

Hirth, J. P. Effects of hydrogen on the properties of iron and steel. Metall. Trans. A 11, 861–890 (1980).

Ordin, P. M. Safety Standard for Hydrogen and Hydrogen Systems Guidelines for Hydrogen System Design, Materials Selection, Operations, Storage and Transportation. NASA Technical Report (1997).

Gangloff, R. P. & Somerday, B. P. Gaseous hydrogen embrittlement of materials in energy technologies: mechanisms, modelling and future developments. (Elsevier, 2012).

Nagumo, M. Fundamentals of hydrogen embrittlement. Vol. 921 (Springer, 2016).

Jemblie, L. et al. Safe pipelines for hydrogen transport. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.06.309 (2024).

Okuno, K. & Takai, K. Extraction of reversible hydrogen trapped on prior austenite grain boundaries and promoting intergranular fracture in the elastic region of tempered martensitic steel by utilizing frozen-in hydrogen distribution at −196°C. Acta Mater. 259, 119291 (2023).

Rodoni, E., Claeys, L., Depover, T. & Iannuzzi, M. Effect of nickel on the hydrogen diffusion, trapping and embrittlement properties of tempered ferritic-martensitic dual-phase low alloy steels. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 98, 418–428 (2025).

Li, H., Lee, C., Venezuela, J., Kim, H.-J. & Atrens, A. Hydrogen diffusion and hydrogen embrittlement of a 1500 MPa hot-stamped steel 22MnB5 in different austenitizing conditions. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 897, 146349 (2024).

Park, H. et al. Impact of hydrogen embrittlement on the tensile-shear property of resistance spot-welded advanced high-strength martensitic steels. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 71, 319–333 (2024).

Matsunaga, H., Yamabe, J., Takakuwa, O., Ogawa, Y. & Matsuoka, S. Hydrogen Gas Embrittlement: Mechanisms, Mechanics, and Design. (Elsevier, 2024).

Matsuoka, S., Yamabe, J. & Matsunaga, H. Criteria for determining hydrogen compatibility and the mechanisms for hydrogen-assisted, surface crack growth in austenitic stainless steels. Eng. Fract. Mech. 153, 103–127 (2016).

Takakuwa, O., Yamabe, J., Matsunaga, H., Furuya, Y. & Matsuoka, S. Comprehensive understanding of ductility loss mechanisms in various steels with external and internal hydrogen. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 48, 5717–5732 (2017).

Sezgin, J.-G., Takakuwa, O., Matsunaga, H. & Yamabe, J. Simulation of the effect of internal pressure on the integrity of hydrogen pre-charged BCC and FCC steels in SSRT test conditions. Eng. Fract. Mech. 216, 106505 (2019).

San Marchi, C. et al. Effect of microstructural and environmental variables on ductility of austenitic stainless steels. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46, 12338–12347 (2021).

Takaki, S. et al. Determination of hydrogen compatibility for solution-treated austenitic stainless steels based on a newly proposed nickel-equivalent equation. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 41, 15095–15100 (2016).

Hughes, L. A., Somerday, B. P., Balch, D. K. & San Marchi, C. Hydrogen compatibility of austenitic stainless steel tubing and orbital tube welds. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 39, 20585–20590 (2014).

San Marchi, C., Michler, T., Nibur, K. A. & Somerday, B. P. On the physical differences between tensile testing of type 304 and 316 austenitic stainless steels with internal hydrogen and in external hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 35, 9736–9745 (2010).

Zhang, L., Wen, M., Imade, M., Fukuyama, S. & Yokogawa, K. Effect of nickel equivalent on hydrogen gas embrittlement of austenitic stainless steels based on type 316 at low temperatures. Acta Mater. 56, 3414–3421 (2008).

Michler, T., Yukhimchuk, A. A. & Naumann, J. Hydrogen environment embrittlement testing at low temperatures and high pressures. Corros. Sci. 50, 3519–3526 (2008).

Cho, H.-J., Cho, Y. & Kim, S.-J. Hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility of Cu bearing cost-effective austenitic stainless steels. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 60, 1–10 (2024).

An, X. et al. Mechanisms of hydrogen embrittlement resistances in FCC concentrated solid solution alloys. Corros. Sci. 229, 111894 (2024).

Wada, K. et al. Hydrogen-induced degradation of SUS304 austenitic stainless steel at cryogenic temperatures. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 927, 147988 (2025).

Ito, T. et al. Role of solute hydrogen on mechanical property enhancement in Fe–24Cr–19Ni austenitic steel: An in situ neutron diffraction study. Acta Mater. 287, 120767 (2025).

Ogawa, Y. et al. Hydrogen, as an alloying element, enables a greater strength-ductility balance in an Fe-Cr-Ni-based, stable austenitic stainless steel. Acta Mater. 199, 181–192 (2020).

Claeys, L., Deconinck, L., Verbeken, K. & Depover, T. Effect of additive manufacturing and subsequent heat and/or surface treatment on the hydrogen embrittlement sensitivity of 316L austenitic stainless steel. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48, 36142–36157 (2023).

Álvarez, G., Harris, Z., Wada, K., Rodríguez, C. & Martínez-Pañeda, E. Hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility of additively manufactured 316L stainless steel: Influence of post-processing, printing direction, temperature and pre-straining. Addit. Manuf. 78, 103834 (2023).

Yamabe, J., Takakuwa, O., Matsunaga, H., Itoga, H. & Matsuoka, S. Hydrogen diffusivity and tensile-ductility loss of solution-treated austenitic stainless steels with external and internal hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 42, 13289–13299 (2017).

Marchi, C. S., Somerday, B. P. & Robinson, S. L. Permeability, solubility and diffusivity of hydrogen isotopes in stainless steels at high gas pressures. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 32, 100–116 (2007).

Omura, T., Yamamura, M., Ito, K., Yamabe, J. & Matsunaga, H. Effects of alloying-element addition on hydrogen diffusion and hydrogen absorption in Ni. ISIJ Int. 65, 1402–1409 (2025).

Ito, K., Yamamura, M., Omura, T., Yamabe, J. & Matsunaga, H. Effects of Cr, Mn, and Fe on the hydrogen solubility of Ni in high-pressure hydrogen environments and their electronic origins: An experimental and first-principles study. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 50, 148–164 (2024).

Wimmer, E. et al. Temperature-dependent diffusion coefficients from ab initio computations: Hydrogen, deuterium, and tritium in nickel. Phys. Rev. B 77, 134305 (2008).

Zhou, X.-Y. et al. Machine learning assisted design of FeCoNiCrMn high-entropy alloys with ultra-low hydrogen diffusion coefficients. Acta Mater. 224, 117535 (2022).

Shuang, F. et al. Decoding the hidden dynamics of super-Arrhenius hydrogen diffusion in multi-principal element alloys via machine learning. Acta Mater. 289, 120924 (2025).

Torres, E., Pencer, J. & Radford, D. D. Atomistic simulation study of the hydrogen diffusion in nickel. Comput. Mater. Sci. 152, 374–380 (2018).

Shiihara, Y. et al. Artificial neural network molecular mechanics of iron grain boundaries. Scr. Mater. 207, 114268 (2022).

Mortazavi, B. Recent advances in machine learning-assisted multiscale design of energy materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 2403876 (2025).

Wang, F. et al. Atomic-scale simulations in multi-component alloys and compounds: A review on advances in interatomic potential. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 165, 49–65 (2023).

Behler, J. Four generations of high-dimensional neural network potentials. Chem. Rev. 121, 10037–10072 (2021).

Unke, O. T. et al. Machine Learning Force Fields. Chem. Rev. 121, 10142–10186 (2021).

Gong, X., Li, Z., Pattamatta, A. S. L. S., Wen, T. & Srolovitz, D. J. An accurate and transferable machine learning interatomic potential for nickel. Commun. Mater. 5, 157 (2024).

Fellman, A., Byggmästar, J., Granberg, F., Nordlund, K. & Djurabekova, F. Fast and accurate machine-learned interatomic potentials for large-scale simulations of Cu, Al and Ni. Phys. Rev. Mater. 9, 053807 (2025).

Wang, J. et al. Efficient moment tensor machine-learning interatomic potential for accurate description of defects in Ni-Al Alloys. Phys. Rev. Mater. 9, 053805 (2025).

Zhang, S., Meng, F., Fu, R. & Ogata, S. Highly efficient and transferable interatomic potentials for α-iron and α-iron/hydrogen binary systems using deep neural networks. Comput. Mater. Sci. 235, 112843 (2024).

Meng, F.-S. et al. A highly transferable and efficient machine learning interatomic potentials study of α-Fe–C binary system. Acta Mater. 281, 120408 (2024).

Zhang, L., Csányi, G., van der Giessen, E. & Maresca, F. Atomistic fracture in bcc iron revealed by active learning of Gaussian approximation potential. Npj Comput. Mater. 9, 217 (2023).

Pitike, K. C. & Setyawan, W. Accurate Fe–He machine learning potential for studying He effects in BCC-Fe. J. Nucl. Mater. 574, 154183 (2023).

Kotykhov, A. S. et al. Constrained DFT-based magnetic machine-learning potentials for magnetic alloys: a case study of Fe–Al. Sci. Rep. 13, 19728 (2023).

Meng, F.-S. et al. General-purpose neural network interatomic potential for the $\ensuremath{\alpha}$-iron and hydrogen binary system: Toward atomic-scale understanding of hydrogen embrittlement. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 113606 (2021).

Sun, H. et al. Molecular dynamics simulation of Fe-Si alloys using a neural network machine learning potential. Phys. Rev. B 107, 224301 (2023).

Dragoni, D., Daff, T. D., Csányi, G. & Marzari, N. Achieving DFT accuracy with a machine-learning interatomic potential: Thermomechanics and defects in bcc ferromagnetic iron. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 013808 (2018).

Mori, H. & Ozaki, T. Neural network atomic potential to investigate the dislocation dynamics in bcc iron. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 040601 (2020).

Ito, K., Yokoi, T., Hyodo, K. & Mori, H. Machine learning interatomic potential with DFT accuracy for general grain boundaries in α-Fe. Npj Comput. Mater. 10, 255 (2024).

Ito, K. & Tabata, S. -i First-principles predictions of transition metal alloying effects on cohesive energy of prior austenite grain boundaries in high-strength steels. Mater. Today Commun. 46, 112890 (2025).

Meng, F.-S. et al. General-purpose neural network interatomic potential for the α-iron and hydrogen binary system: Toward atomic-scale understanding of hydrogen embrittlement. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 113606 (2021).

Ito, K., Otaki, T., Hyodo, K., Yokoi, T. & Mori, H. Machine-learning potential reveals the origin of hydrogen embrittlement at general grain boundaries in α-Fe. 18 July 2025, PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-7113724/v1 (2025).

Sun, C. et al. A high-throughput molecular dynamics study with a machine-learning method on predicting diffusion coefficient of hydrogen in α-iron grain boundaries. Mater. Today Commun. 44, 111997 (2025).

Angeletti, A. et al. Hydrogen diffusion in magnesium using machine learning potentials: a comparative study. Npj Comput. Mater. 11, 85 (2025).

Kwon, H., Shiga, M., Kimizuka, H. & Oda, T. Accurate description of hydrogen diffusivity in bcc metals using machine-learning moment tensor potentials and path-integral methods. Acta Mater. 247, 118739 (2023).

Yu, F., Xiang, X., Zu, X. & Hu, S. Hydrogen diffusion in zirconium hydrides from on-the-fly machine learning molecular dynamics. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 56, 1057–1066 (2024).

Szlachta, W. J., Bartók, A. P. & Csányi, G. Accuracy and transferability of Gaussian approximation potential models for tungsten. Phys. Rev. B 90, 104108 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. DP-GEN: A concurrent learning platform for the generation of reliable deep learning based potential energy models. Comput. Phys. Commun. 253, 107206 (2020).

Matsumura, N. et al. Generator of neural network potential for molecular dynamics: constructing robust and accurate potentials with active learning for nanosecond-scale simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 21, 3832–3846 (2025).

Zhang, L. et al. in Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 4441–4451 (Curran Associates Inc., Montréal, Canada, 2018).

Chen, C. & Ong, S. P. A universal graph deep learning interatomic potential for the periodic table. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2, 718–728 (2022).

Deng, B. et al. CHGNet as a pretrained universal neural network potential for charge-informed atomistic modelling. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 1031–1041 (2023).

Behler, J. & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146401 (2007).

Drautz, R. Atomic cluster expansion for accurate and transferable interatomic potentials. Phys. Rev. B 99, 014104 (2019).

Shapeev, A. V. Moment Tensor Potentials: A Class of Systematically Improvable Interatomic Potentials. Multiscale Model. Simul. 14, 1153–1173 (2016).

Bartók, A. P., Payne, M. C., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. Gaussian approximation potentials: the accuracy of quantum mechanics, without the electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 136403 (2010).

Thompson, A. P., Swiler, L. P., Trott, C. R., Foiles, S. M. & Tucker, G. J. Spectral neighbor analysis method for automated generation of quantum-accurate interatomic potentials. J. Comput. Phys. 285, 316–330 (2015).

Yoshimoto, Y., Matsumura, N., Iwasaki, Y., Nakao, H. & Sakai, Y. Large-Scale, Long-Time Atomistic Simulations of Proton Transport in Polymer Electrolyte Membranes Using a Neural Network Interatomic Potential. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.20412 (2025).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Henkelman, G. & Jónsson, H. Improved tangent estimate in the nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths and saddle points. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9978–9985 (2000).

Katz, L., Guinan, M. & Borg, R. J. Diffusion of H2, D2 and T2 in single-crystal Ni and Cu. Phys. Rev. B 4, 330–341 (1971).

Völkl, J. & Alefeld, G. in Hydrogen in Metals I: Basic Properties (eds Alefeld, G. & Völkl, J.) 321–348 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1978).

Zunger, A., Wei, S. H., Ferreira, L. G. & Bernard, J. E. Special quasirandom structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 353–356 (1990).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO–the Open Visualization Tool. Model. Simul. Mat. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012 (2010).

van de Walle, A., Asta, M. & Ceder, G. The alloy theoretic automated toolkit: A user guide. Calphad 26, 539–553 (2002).

van de Walle, A. et al. Efficient stochastic generation of special quasirandom structures. Calphad 42, 13–18 (2013).

Yang, S., Wang, Y., Liu, Z.-K. & Zhong, Y. Ab initio simulations on the pure Cr lattice stability at 0K: Verification with the Fe-Cr and Ni-Cr binary systems. Calphad 75, 102359 (2021).

Zeng, J. et al. DeePMD-kit v2: A software package for deep potential models. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 054801 (2023).

Wang, X.-Y. et al. Deep neural network potential for simulating hydrogen blistering in tungsten. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 093601 (2023).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Narayan, A., Berger, B. & Cho, H. Assessing single-cell transcriptomic variability through density-preserving data visualization. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 765–774 (2021).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Methfessel, M. & Paxton, A. T. High-precision sampling for Brillouin-zone integration in metals. Phys. Rev. B 40, 3616–3621 (1989).

Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 7182–7190 (1981).

Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Crystal structure and pair potentials: a molecular-dynamics study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 1196–1199 (1980).

Togo, A., Chaput, L., Tadano, T. & Tanaka, I. Implementation strategies in phonopy and phono3py. J. Condens. Matter Phys. 35, 353001 (2023).

Togo, A. First-principles Phonon Calculations with Phonopy and Phono3py. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 92, 012001 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work used computational resources of the Supercomputer Fugaku provided by Riken through the HPCI System Research Project (Project ID: hp230272, hp240280). This work was partly supported by Accompanying User Support Program (【23Z-03, 23Z-05, 24H1-01】, Support content:【porting of application program, execution performance tuning】) performed by Research Organization for Information Science and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kazuma Ito: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Investigation. Naoki Matsumura: Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. Yuto Iwasaki: Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. Yasufumi Sakai: Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. Misaho Yamamura: Writing – review & editing. Tomohiko Omura: Writing – review & editing. Junichiro Yamabe: Writing – review & editing. Hisao Matsunaga: Writing – review & editing. K.I. developed the potential, performed and analyzed all simulations, and wrote the paper. N.M., Y.I., and Y.S. developed the software necessary for potential development. M.Y., T.O., J.Y., and H.M. contributed to the discussion regarding comparison with experimental results. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Edmanuel Torres and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ito, K., Matsumura, N., Iwasaki, Y. et al. Predicting hydrogen diffusion in nickel–manganese random alloys using machine learning interatomic potentials. Commun Mater 6, 195 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00924-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00924-x

This article is cited by

-

Toward intelligent design of solid-state hydrogen storage: trends, challenges, and machine learning insights

ENGINEERING Chemical Engineering (2026)

-

Machine learning interatomic potential reveals hydrogen embrittlement origins at general grain boundaries in α-iron

Communications Materials (2025)