Abstract

Exposure of matter to high-energy heavy ions induces defects along the ion trajectories through electronic and nuclear energy loss processes. Defects, including color centers, can recombine or form along latent damage tracks in semiconductors. Latent tracks in diamond were only recently observed. Here we report on color center formation in nitrogen-doped diamond along the latent tracks of 1 GeV gold and uranium ions. We optically observe direct formation of single vacancy related color centers (GR1-centers) along the tracks. Mobile vacancies can form NV-centers with native nitrogen atoms during thermal annealing. Molecular dynamics simulations show that isolated vacancies and vacancy clusters form through electronic stopping processes along ion trajectories. Moreover, by using 1 GeV Au ions with a dilute fluence, we create individually isolated quasi-1D chains of NV-centers, which appear as isolated bright luminescence strings and present competitive electron spin properties compared to a background of NV-centers. Such spin textures can be building blocks for applications in quantum sensing and computing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-energy, heavy ions (or swift heavy ions (SHI)), deposit tens of keV of energy per nanometer when they impinge on materials1. Under SHI irradiation, intense local excitations can induce a wide range of defects along ion trajectories, including point defects, such as vacancies and interstitials, extended SHI tracks, and even amorphous regions. Many of these defects quickly recombine, while others form stable defect centers, including optically active defects, or color centers. The track dimensions of SHI, e.g., in polymers or semiconductors, have unique nm-scale alignment over tens of microns. In diamond, latent tracks of damage centers were only very recently observed2. Recently, evidence for the formation of ensemble quasi-1D chains of NV-centers in diamond formed by SHI has been reported in diamonds that contained 100 ppm of nitrogen3. The quasi-1D characteristic arises from its high aspect ratio, extending predominantly in one dimension over tens of micrometers, while lateral dimensions measure only a few nanometers. Here, we report on the formation process of NV-centers in quasi-1D chains using 1 GeV gold and uranium ions and single-crystal diamonds that contain 1 ppm nitrogen. At this lower nitrogen concentration, the optical signal from background NV-centers is reduced, thereby enabling us to unravel the role of single vacancy centers (GR1) along ion trajectories in the formation of spin textures with NV-centers. We further create individually isolated quasi-1D chains of NV-centers in the diamond ( <200 ppm of nitrogen) by using 1 GeV Au ions with a dilute fluence. The individual 1D NV-chains appear as isolated bright luminescence strings, which indicates the presence of densely coupled NV-centers created along a single ion trajectory.

Negatively charged nitrogen-vacancy (NV−) color centers in diamond possess an optically accessible spin-1 triplet ground state with up to millisecond longitudinal relaxation time T1 and coherence time T2 at room temperature4. Optically selective transitions enable utilizing NV− centers for quantum sensing via optically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR), often with superior sensitivity compared to conventional magnetometers5. Thanks to the technical simplicity, radiation robustness, chemical inertness, and nanoscale geometry, diamond-NV sensing can be deployed in harsh radiation, biochemical, and geoscience-related environments6,7,8,9. The control of multiple coupled NV− centers10,11,12 is an essential prerequisite for realizing a variety of functionalities of diamond-NV sensing and unitary fidelity of quantum protocol operations13,14,15,16,17,18.

Recent studies indicate self-aligned quasi-1D chains of coupled NV− centers along a length of several tens of microns3. This effect is promising for the development of a type of quantum register and a building block for diamond-NV-based quantum information processing19,20,21. Such quasi-1D chain of NV− centers can be realized by SHI of sufficiently high electronic stopping power, such as e.g., 1–2 GeV gold or uranium ions irradiation of single crystal diamonds. The energy deposition along the ion trajectory of several tens of keV per nm leads to the formation of vacancy centers and the conversion of native nitrogen atoms to NV-centers. Adjusting the nitrogen concentration, and the energy and species of the ions allow engineering the longitudinal NV− spacing on the few nanometer scale and resulting spin chains on the length scale of tens of microns3,22,23. Additionally, 2D sheets of NV centers can be created by sidewall irradiation or by patterning a metal grid on the diamond surface to confine the ion beam, forming a 30 μm-thick layer of NV centers with promising applications in wide-field quantum sensing. The quasi-1D NV− chains are expected to preserve the main characteristics of ideal 1D spin systems - strictly confined to a single dimension without cross-sectional extent, thus enabling investigations of Ising model spin dynamics and explorations of spin transport and registers24,25. Formation of GR1-centers and NV-centers in diamond by SHI also supports the development of diamond-based single ion track detectors23,26 and methods for directional detection of hypothetical highly energetic dark matter candidates27. Further, the optical readout of NV-centers along ion tracks supports experimental benchmarking of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the interaction between SHI and the diamond lattice28.

In this study, we present insight into GR1 and NV-center generation along the tracks of SHI in diamond and quantify the resulting spin properties of NV-centers. Diamond with <1 ppm N density was chosen in order to suppress decoherence induced by the nitrogen spin bath12 and to enable the observation of GR1-centers in the spectral range that overlaps with that from NV− centers. By using confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy 3, we characterized GR1, NV0, and NV− centers and the conversion from GR1’s to NV-centers. We show that the NV-center formation dynamics by SHI in diamonds with relatively low nitrogen content follow a two-step process of vacancy formation, followed by capture of mobile vacancies by substitutional nitrogen atoms. The SHI-induced vacancies can act as optically active GR1-centers, when presented as individual isolated neutral vacancies. Vacancies form predominantly along the ion path where the electronic stopping power is highest. They can further combine with the nearby nitrogen atoms to form NV-centers during the cooling down of the excited track zone. NV− center formation is further enhanced during thermal annealing after SHI irradiations. The micrometer-resolved optical analysis on the NV-center formation provides experimental benchmarking data for dynamic Monte Carlo simulations of ion track structures and micro-dosimetric models.

To further create a coupled NV-centers spin chain, we chose diamond with <200 ppm N density, which allows created dense coupled NV-centers with spacing in the range of a few nm along single ion trajectories. Individual quasi-1D chains of NV-centers were created by using 1 GeV Au ions with a dilute fluence and post annealing. We probe the spin properties of SHI-induced NV− via ODMR, which shows that SHI-induced NV− centers along quasi-1D chains or in thin sheets with length of about 30 μm can be used for applications in high-sensitivity magnetometry and for studies of spin textures in diamonds. Irradiation with SHI is a method for NV-center formation, complementary to more common irradiation with MeV electrons and protons29, with the unique feature of alignment of NV-centers along the (mostly) straight SHI trajectories in quasi-1D chains with a width of a few nm and a length of tens of microns.

Results and discussion

Optical properties of color centers formed along the SHI trajectories

Type IIa diamonds (supplier: Element 6) were used in this study with about 1 ppm nitrogen introduced during the chemical vapor deposition growth. In a first step, we implanted erbium ions into diamond samples (1 × 1013 cm−2, 180 keV). Er ion implantation30 led to the formation of NV-centers near the sample surface, within the top 100 nm as estimated by the stopping and range of ions in matter modeling (SRIM-2008)31. Emission from NV-centers near the surface serves as a reference of the sample surface for depth dependent PL measurements. We did not observe optical emission from Er atoms or signatures of NV-Er coupling in optical spectra or in ODMR. Next, pre-implanted samples were irradiated at the linear accelerator UNILAC at GSI Helmholtzzentrum (Darmstadt, Germany) using 1.1 GeV U ions (fluence of 1 × 1012 U ions/cm2) and 0.95 GeV Au ions (2.2 × 1012 Au ions/cm2), labeled as sample A and B, respectively. The electronic stopping power at the sample surface and the range in diamond are 49 keV/nm and 30 μm for U ions and 40 keV/nm and 30 μm for Au ions (estimated using SRIM). These rather similar values of both irradiation conditions allow us to observe common SHI-related effects and trends. The samples were covered by a thick honey-comb shaped mask with millimeter-sized openings (90% transparency), which allows direct comparison between irradiated and nonirradiated regions during the PL measurements.

To enhance the formation of NV− centers, the Au-ion irradiated sample B was thermally annealed in a two-step process and the optical properties were compared after the 1st and the 2nd annealing step. The 1st annealing step was for 1 h at 800 °C in vacuum (10−6 mbar), the 2nd annealing step was for 1 h at 1000 °C in argon atmosphere. After the two annealing steps, we performed secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) measurements on sample B (See Supplementary Fig. 1 in the Supplementary Note 1). SIMS depth profiles show accumulation of nitrogen to concentrations of up to 1 × 1019 cm−3 (~60 ppm) within a surface layer of 100 nm depth and a concentration of 3 × 1016 cm−3 (0.2 ppm) for larger depths. This value is consistent with the <1 ppm indicated by the supplier, but may also be affected by the absolute calibration in SIMS measurements. The Er profile is distributed within the top 300 nm with an apparent areal density of 4.1 × 1012 cm−2. We note that the absolute concentration numbers are possibly affected by the SIMS calibration.

We performed depth-dependent PL on U-ion irradiated samples (sample A, without thermal annealing) to characterize the interaction between nitrogen and SHI-formed vacancies.

Figure 1a shows the PL spectra as a function of the probe depth (refractive index corrected3) from the irradiated surface (red) to a depth of 30 μm (marked as blue). In the non-irradiated areas, we observe a weak GR1 zero phonon line (ZPL) signal (Supplementary Fig. 2 in the Supplementary Note 2) that is visible near the sample surface, within the implantation range of the Er ions. When probing deeper regions, the spectra are dominated by a weak emission from native NV-centers that are present in the as-received sample. The luminescence of GR1-centers is known to originate from individual neutral vacancies32, which evidences that the SHIs generate individual isolated vacancies along their trajectories by displacing carbon (or nitrogen) atoms from their lattice position. We also observe weak luminescence from NV− and NV0 center at the ZPLs of 637 and 575 nm, respectively. In addition, the typical first-order Raman line near 573 nm in diamond excited by 532 nm laser was observed33. This phenomenon is different from our previous experiment, where preferentially NV− centers were formed in diamond that contained 100 ppm nitrogen and that had been irradiated with 1 GeV Au ions (1012 cm−2)3. The major difference in the present experiment is the more than two orders of magnitude reduced intrinsic nitrogen concentration of 1 ppm, while the ion irradiation conditions are similar. Figure 1b shows the depth-dependent PL spectrum of Au-ion irradiated areas of sample B after thermal annealing. Here, the spectra are dominated by the typical ZPL of NV0 at 575 nm and NV− at 637 nm, while spectral signatures of GR1-centers are now absent. The annihilation of GR1 luminescence in sample B after the annealing shows that the SHI-irradiation induced vacancies either combine with nitrogen atoms to form NV-centers or that they are annihilated, e.g., via recombination with carbon interstitials.

a Color center PL spectra of sample A (no annealing) as a function of depth from the sample surface to a depth of 30 μm in the area irradiated with 1 × 1012 U ions/cm2 fluence of 1.1 GeV energy. b Color center PL spectra of sample B (after two annealing steps) as a function of depth from the sample surface to a depth of 30 μm in the area irradiated with 2.2 × 1012 Au ions/cm2 fluence of 0.95 GeV energy. c Deconvolution of the PL spectrum (blue) into NV− and GR1 luminescence components probed in the SHI-irradiated area of sample A at depth = 14 μm (roughly half the SHI range). The red and black spectra show the deconvoluted spectrum GR1 and NV−, respectively. d Deconvolution of sample B probed in the SHI irradiated area at a depth of 14 μm after annealing. The black and gray spectrum shows the decomposed respective data for NV− and NV0 centers.

To quantify the PL intensity and analyze the conversion between GR1 and NV− along the SHI trajectories, Fig. 1c shows an example of the deconvolution of the spectra into NV− and GR1 luminescence components of sample A (at depth = 14 μm in the SHI irradiated area)34,35. The deconvolution approach is described in the Supplementary Note 3. The GR1 PL intensity is more than one order of magnitude higher than the NV− intensity after exposure to SHI and before annealing. This shows that for a diamond with a low nitrogen concentration (nominal 1 ppm) the share of SHI-induced vacancies that combing with nitrogen and form NV− centers is small. This is in contrast to earlier experiments, where strong NV− center emission was observed directly after SHI irradiations and before thermal annealing3. At the lower nitrogen concentration, SHI-induced vacancies have to move farther to find a nitrogen atom for NV-center formation. At a nitrogen concentration of 100 ppm, the average distance between N atoms is about 5 nm, while it is 20 nm at 1 ppm. Vacancies can diffuse during track cool down or thermal annealing and form NV-centers if enough N atoms are present near the ion trajectory.

As shown in Fig. 1d, in the SHI-irradiated area, the ratio of the NV− spectral area to that of NV0 is enhanced after the 2nd thermal annealing step compared to the 1st annealing step (see Supplementary Fig. 3 in the Supplementary Note 3). NV0 centers form first during thermal annealing and the charge state balance shifts to NV− via NV0 + e−⇌ NV− during longer annealing times, when vacancy centers dissolve and electrons from the relatively sparse N density can be picked up by thermally activated charge transfer36. Performing a 2nd annealing step allows us to thermally drive this process by further promoting the ionization of nitrogen donors and to transfer the electron charge to the site of NV0 centers, consequently converting NV0 to NV−.

MD simulation of the interaction between SHI and the diamond lattice: an insight into PL measurement

Figure 2a compares depth profiles of the normalized PL intensity of the GR1 luminescence of sample A with the emission of NV− centers that is dominant in the annealed sample B.

a Comparison of depth-resolved normalized PL intensity (logarithmic scale) of GR1 defect in sample A (no annealing) and NV− defect in the annealed sample B. b The simulated concentrations of vacancies in the form of isolated vacancies and vacancy clusters along the ion trajectory from electronic energy loss processes according to MD simulations. Based on SRIM, the vacancy-creation rate ranges from 0.34 vacancies nm−1 in the direction with the lowest displacement energy ([100], 37.5 eV) to 0.26 vacancies nm−1 in the direction with the highest displacement energy ([110], 47.6 eV)54. c Electronic and nuclear stopping powers along the ion trajectory of 1.1 GeV U ions in diamond (right axis). The left axis shows the contour lines of the initial energy density of 10 and 100 eV/nm3 after ion impact in the electronic subsystem as estimated from the delta-ray dose formulas (See Supplementary Note 4). d Visualization of the MD simulation cells at different depth so that atoms are drawn as gray dots. The arrow on the left shows the ion propagation direction. The right two subfigures show the zoom-in area with defect clusters at 7 and 19 μm depth.

The two PL intensity profiles show a similar plateau up to a depth of 15 μm. With the electronic stopping range from 20 to 30 μm depth, the GR1 PL intensity in sample A drops more drastically than the NV− PL in sample B. The GR1 PL intensity between the sample surface and the regime of end-of-range ion track differs by two orders of magnitude. The drastic decrease of GR1 PL intensity at the end of electronic stopping range can be related to the clustering of vacancies, which can render the centers optically inactive. The formation of vacancy complexes can be further enhanced by the nuclear stopping process at the end of the ion path3. In contrast, in sample B, the reduction of PL intensity of NV− center emission from the sample surface to the end of the ion range is less than 1 order of magnitude. We infer that the thermal annealing converts the additional vacancies and substitutional nitrogen atoms into NV− centers near the end of the ion range. These results show that SHI efficiently introduce vacancies along their trajectories in areas of high electronic stopping, as well as at the end of their range where elastic collisions dominate. It also indicates that the NV-center formation dynamics by SHI is governed by a two-step process that depends on the available nitrogen atoms around the ion trajectory. The SHI-induced vacancies can be in the form of individual neutral vacancies or further combine with the neighboring N to form NV-centers. The strong GR1 luminescence introduced directly by SHI irradiation (without thermal annealing) as well as damage repair and re-crystallization via thermal annealing are important features for applications of diamond-based radiation detectors, such as fluorescent nuclear track detectors for extreme radiation environments22,23.

To gain insight into vacancy formation resulting from electronic stopping processes for 1.1 GeV U ion, we performed two-temperature MD simulations in pure diamond using the Tersoff potential with the original carbon parameterization given by Tersoff37. The detailed model is described in ref. 2 and also in the Supplementary Note 4. The simulations here exclusively consider the electronic component, omitting nuclear stopping power effects. To circumvent the computation limits, the 30 μm long ion trajectory was segmented into ten small simulations depicting small slabs along the path, each with dimensions of 23 × 23 × 11 nm3 (XYZ). The trajectory is centered in X and Y directions and penetrates through the cell along the Z axis. The total simulation time is 50 ps. Figure 2b shows the vacancy concentrations along the trajectory, as determined by the Wigner-Seitz analysis at the end of each simulation. The time evolution of defects is discussed in the Supplementary Note 5. The plot shows that the concentration of isolated vacancies (Voronoi cells) slightly increase from 0.5 to 1 nm−1, as the ion track extends from surface to the internal depth of 20 μm. In comparison, the vacancies density in the form of clusters (empty Voronoi cells connected to other cells) increases drastically from 0 to 7 nm−1 from the surface to a depth of 20 μm.

The increase in vacancy clustering at greater depths is surprising, since the electronic stopping power has its maximum at the surface, as shown in Fig. 2c. We tentatively ascribe the enhanced vacancy clustering near 20 μm to the ion velocity effect. Our simulation of the delta-ray radial dose distribution in Fig. 2c reveals that the initial energy density near the trajectory increases due to the decreased velocity of the ion38 until about 20 μm. In our model, this is a direct consequence of the increased range of delta-electrons resulting from the kinematics of high-velocity ion-electron collisions, which is incorporated into the analytical formula describing the initial energy density (see Supplementary Note 4). As a result, the energy corresponding to the linear stopping power at each depth is initially distributed over a broader region near the surface than deeper in the sample. Similar behavior has also been observed in explicit Monte Carlo simulations of electron kinetics39. Higher energy densities result in stronger defect production. Focusing on the role of electronic stopping processes, we neglect the contributions to vacancy production from elastic collisions.

Figure 2d shows atomic-scale disorder along the ion trajectory from MD simulations at different depths, where perfectly crystalline atoms appear gray, while any deviations from crystallinity appear darker. Note that darker regions in the image do not necessarily correspond to features that would be visible in a typical TEM image, as the visualization represents a projection through the entire sample. More conventional visualizations are provided in the Supplementary Note 5. For monoatomic SHIs irradiation in diamond, e.g., Au, our MD simulations predict small, discrete defect clusters aligning along the ion trajectory. This contrasts with fullerene ions, where more pronounced, continuous tracks were previously reported in ref. 2. The details of isolated defects and clusters can be seen in the enlarged visualization of the cell at 7 and 19 μm depth. The MD simulation results clearly reveal that close to the surface of <10 μm, the damage consists of both isolated interstitial-vacancy (Frenkel) pairs and small defect clusters. The size of the defect clusters tends to gradually increase within a depth between 13 and 20 μm. In particular, we observe graphitization of the diamond structure showing amorphous defect clusters near 20 μm depth. In the 20–25 μm range, there is a sharp decrease in the defect concentration, until no defects form at depths greater than 25 μm. Such a velocity effect with graphitization and a sharp decrease of vacancy concentration in the 20–25 μm range can well explain the experimentally observed drastic drop of GR1 emission in this depth range. However, as mentioned above, the simulation does not account for the nuclear stopping power, due to the calculation complexity. As ions slow down, the nuclear stopping power component becomes increasingly significant compared to electronic stopping leading to the formation of defects at the end of the ion ranges, potentially leading to further vacancy defects. Potential synergies of elastic and inelastic energy loss processes on defect kinetics will be explored in future studies40,41.

Electron spin properties of ensemble NV− centers with deep subsurface placement formed by high fluence SHI irradiation

We performed ODMR measurements to characterize the electron spin (ms = +1) properties of ensemble NV− centers with deep subsurface placement formed by high-fluence SHI irradiation after thermal annealing (sample B).

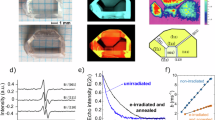

Figure 3a shows a comparison of ESR signal of the electron spin state of the NV− centers probed in the area with (black dots) and without (blue dots) SHI irradiation. We observed that the ESR contrast of ensemble NV− centers formed by SHI irradiation is about twice as much of the intrinsically existed background NV− probed in the area of no SHI irradiation. Moreover, SHI-induced ensemble of NV− centers presents a 13.9 ± 0.1 MHz full width at half maximum (FWHM) of ESR signal, which is notably smaller than 14.4 ± 0.2 MHz of background NV−. Figure 3b shows Rabi oscillations of the SHI-induced ensemble NV−centers42. We derived an effective dephasing time τ = 0.53 ± 0.04 μs from the decay of the amplitude of the Rabi oscillation signal, which is comparable to dephasing times reported from NV− ensembles present in diamonds containing nitrogen concentration in the ppm range43,44. Since the dephasing mechanism of NV− is mainly governed by the spin bath44,45, the dephasing of NV− centers in our sample is affected by a relatively high surface nitrogen concentration and potentially by other surface noise. The depth dependent dephasing kinetics will be probed in future studies. Figure 3c presents the correspondent T1 relaxation contrast of SHI-induced ensemble of NV− spins, by using a 200 ns π pulse calibrated by the Rabi measurement. By fitting the experimental data with single exponential decay, we extracted a T1 coherent time of 5.8 ± 0.2 ms. Figure 3d presents the T2 relaxation contrast of NV− spins probed in the SHI-irradiated area of sample B after thermal annealing, by implementing spin echo (Hahn-echo) MW pulse sequence. Red curve correspond to the fit by the model referred to ref. 46, which allows to extract the T2 coherent time of 48.1 ± 9.7 μs and T2* time of 2.4 ± 0.2 μs. This characterized time of T1, T2, and T2* is even slight longer than the values of background NV− probed in the area without SHI irradiation (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7 in Supplementary Note 6). Overall, compared to background NV− center, the ensemble of NV− centers created by SHIs presents a stronger ESR contrast, narrower linewidth, and preserves comparable T1, T2, and T2*. It validates that high fluence SHI irradiation followed with post annealing enables creating dense ensemble of NV− centers with superior spin properties, compared to background NV− centers.

a A comparison of ESR signal of the electron spin state ms = +1 of the NV− centers probed in the area with (black dots) and without (blue dots) SHI irradiation after thermal annealing, with the external magnetic field of 80 Gauss was aligned to the < 001 > crystallographic orientation. Red curves correspond to the single Gaussian fitted individual resonance, with an extracted FWHM of the ESR signal of 13.9 ± 0.1 MHz and 14.4 ± 0.2 MHz probed in the area with and without SHI irradiation, respectively; b The correspondent Rabi oscillations contrast of NV− spins probed in the SHI irradiated area of sample B after thermal annealing. Red curve correspond to the sinusoidal function modulated by single exponential decay, with an extracted Rabi dephasing time of 0.53 ± 0.04 μs; c Presents the correspondent T1 relaxation contrast of NV− spins probed in the SHI-irradiated area of sample B after thermal annealing, by using a 200 ns π pulse calibrated by the Rabi oscillation. Red curve correspond to single exponential decay, with extracted T1 coherent time of 5.8 ± 0.2 ms; d Presents the T2 relaxation contrast of NV− spins probed in the SHI-irradiated area of sample B after thermal annealing, by implementing spin echo (Hahn-echo) MW pulse sequence. Red curve correspond to the fit by the model referred to ref. 46, which allows to extract the T2 coherent time of 48.1 ± 9.7 μs and T2* time of 2.4 ± 0.2 μs.

Single individual 1D chains of NV− centers formed by dilute SHI irradiation

We expect that our approach should be able to create single individual self-aligned quasi-1D chains of coupled NV-centers with lengths in the tens of micron range, which can be a building block for quantum information processing. Such structures can also provide insights into harsh radiation-matter interactions.

We performed 1 GeV Au ions irradiation with a dilute fluence of 1 × 108 ions/cm2 on Type Ib HPHT diamond wafer (supplier: Element 6) with <200 ppm nitrogen impurities), followed by one hour post annealing at 1000 °C, vacuum (<10−4 mbr). The yellow diamond with relatively high native nitrogen concentration was intentionally chosen for creating dense and coupled NV− along the SHI trajectories 3. Subsequently, by performing 2D planar PL scan with a focused depth of 31 μm, we observed isolated individual bright luminescence spots in the 2D PL mapping (4 × 4 μm2) probed at the SHI-irradiated area, as shown in Fig. 4a. The density of bright luminescence spot in the probe area is about 0.75 × 108 cm−2. We did not observe any of these bright luminescence spots in the area of sample where SHIs were blocked by the mask.

a Planar view of 2D PL mapping (4 × 4 μm2) probed at the depth of 31 μm of the SHI irradiated area showing isolated individual 1D NV− chains as isolated individual bright luminescence spots; b Visualization of 3D luminescence patterns of individual 1D NV− chains reconstructed by discrete 2D PL scan probed at different depth from 0 to 30 μm; c Color center PL spectra evolution along the SHI trajectory from the sample surface to a depth of 30 μm; d A comparison of integrated PL intensity as a function of depth probed on (red) and off (black) a single SHI ion track.

To further verify our hypothesis, we selectively visualized in Fig. 4b several bright 3D luminescence patterns of individual 1D NV− chains, probed at the same area of Fig. 4a. It was reconstructed by multiple discrete 2D PL scans probed at different depth from 0 to 30 μm. The isolated bright luminescence strings evidence the presence of densely coupled NV-centers created along a single ion trajectory. Figure 4c reveals color center PL spectra evolution along the SHI trajectory from the sample surface to a depth of 30 μm, which comprise dominated NV− ZPL and phonon sideband emission and weak NV0 component emission. Figure 4d shows a comparison of integrated PL intensity as a function of depth probed on (red) and off (black) the single SHI ion track. The up to 30 μm length luminescence pattern of 1D chains of NV-centers is close to the MD simulated estimated range of isolated vacancies and defect clusters formed along ion trajectories through electronic stopping processes. Moreover, the PL intensity along the 1D NV− chain increases monotonically, which is in line with the gradually increase of the concentration of vacancies in the form of clusters within the electron stopping range. It indicates that the formation of NV-centers along SHI trajectories is governed by the interaction of native nitrogen atoms with vacancies in the form of clusters. Our optical characterization confirm that isolated individual quasi-1D chains of NV-centers are formed by SHI irradiation and post-annealing leads to the conversion of native nitrogen atoms to NV centers along the ion trajectories.

To realize a 1D NV spin chain for applications, such as quantum registers or qubit transport channels, it is essential to precisely tailor dipole-dipole coupling between NV-centers with nanometer-scale spacing along the chain. The results of our previous experiment have demonstrated3 that the estimated conversion efficiency from nitrogen atom to NV along SHIs trajectories is approximately 15–20%, assuming a nitrogen density of 100 ppm, with 1 GeV gold ion irradiation. Though this remains a rough approximation, it provides a qualitative prediction of average spacings of a few nanometers over a length exceeding ten micrometers, resulting in a quasi-1D register containing potentially over a thousand qubits. At room temperature, the atomic defect structure of these 1D NV chains remains stable due to the high activation energy for defect migration in diamond47, as evidenced by our repeated measurements of the same 1D NV-center chains overtime with no observed degradation in their optical or spin properties.

We further quantify the electron spin (ms = -1) properties of individual 1D NV− chains through ODMR.

An external magnetic field of 70 Gauss was aligned to the <001> crystallographic orientation, and perpendicular to the 1D NV− chain. A optical spatial resolution better than 0.5 μm allows optically addressing individual 1D NV− chains. As shown Fig. 5a, individual 1D NV− chains show enhanced electron spin resonance contrast and narrower linewidth compared to the background of NV− centers present in the nitrogen-doped diamonds. This trend is in common with the comparison between the prior mentioned ensemble NV− centers formed by the high fluence SHI irradiation and background NV-centers. Figure 5b presents the correspondent Rabi oscillation of an individual 1D NV− chain, with Rabi dephasing time of 0.3 ± 0.1 μs. Figure 5c, d presents the correspondent T1 (12.6 ± 5.5 μs) and T2* (0.4 ± 0.2 μs) relaxation measurement of 1D NV− chains. Compared to the ensemble NV− centers formed by the high-fluence SHI irradiation, the single 1D NV− chains show less ESR contrast, and shorter T1 and T2* times. Note that there are relatively large uncertainties due to low-fluorescence counts when probing single 1D NV-center chains. It is well established that T2 and coherence times are reduced in strongly coupled environments with higher line densities of NV− and nitrogen impurity, whereas it is less commonly observed that T1 is also shortened. In this study, however, we observed marked differences in both the ZPL and phonon emission profiles between the samples with significantly different N concentrations. Since T1 relaxation time is influenced by the local phonon density and magnetic noise, we attribute the shortened T1 to enhanced local phonon density, and magnetic fluctuations48,49,50,51,52 likely induced by the high density P1 spin bath (and spin noises)48,53. It can be due to the fact that the 1D NV− chains experience stronger dephasing and spin noise in yellow diamond, due to the larger nitrogen impurities (<200 ppm), compared the host diamond (1 ppm nitrogen impurities) of ensemble NV− centers. Though it is beyond the scope of the study, it is worthwhile to explore the approach of suppressing nitrogen impurity induced dephasing while maintain dense and coupled NV− centers along the 1D chain. In addition, as to the spin relaxation and coherent properties of background NV− center spins probed in the area without SHI irradiation of the sample, we did not observed obvious Rabi, T1 and T2 relaxation contrast (see Supplementary Fig. 8 in Supplementary Note 7) by using the same measurement condition and spin readout protocol as used for 1D chain of NV− centers. It can be due to the insufficiency signal-to-noise ratio of background NV− centers to probe their spin properties. Our findings suggest the possibility that NV-centers in 1D chains with dipolar interaction between NV-centers can improve the sensitivity in NV-based magnetometry applications and provide guidance on the engineering of 1D chains of NV-centers with minimal disorder for applications in quantum information processing.

a A comparison of ESR signal of the electron spin state ms = -1 of the NV− centers probed in the area with (black dots) and without (blue dots) SHI irradiation after thermal annealing, with the external magnetic field of 70 Gauss aligned to the <001> crystallographic orientation, and perpendicular to the 1D NV− chain. Red curves correspond to the single Gaussian fitted individual resonance, with an extracted FWHM of the ESR signal of 15.7 ± 0.5 MHz and 16.4 ± 0.8 MHz probed in the area with and without SHI irradiation, respectively; b The correspondent Rabi oscillations contrast of NV− spins probed in the SHI-irradiated area of sample B after thermal annealing. Red curve correspond to the sinusoidal function modulated by single exponential decay, with an extracted Rabi dephasing time of 0.3 ± 0.1 μs; c Presents the correspondent T1 relaxation contrast of NV− spins probed in the SHI irradiated area of sample B after thermal annealing, by using a 200 ns π pulse calibrated by the Rabi oscillation. Red curve correspond to single exponential decay, with extracted T1 coherent time of 12.6 ± 5.5 μs; d Presents the T2 relaxation contrast of NV− spins probed in the SHI-irradiated area of sample B after thermal annealing, by implementing spin echo (Hahn-echo) MW pulse sequence. Red curve correspond to the fit by single exponential decay, with extracted T2* coherent time of 0.4 ± 0.2 μs.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we investigated NV− center formation along the trajectories of swift gold and U ions in the kinetic energy range of ~1 GeV in nitrogen-doped single crystal diamonds. Using confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy, we examined how SHI-induced vacancies interact with native nitrogen during track formation and investigated how thermal annealing drives structural and charge conversions among GR1, NV0, and NV− centers. We found strong GR1 emission along SHI paths, directly formed via electronic stopping—an observation relevant to diamond-based detectors and dark matter searches. MD simulations reveal that SHI-induced energy deposition via electronic stopping creates both isolated vacancies and defect clusters along the ion paths with a velocity-dependent mechanism that enhances clustering in regions where the electronic stopping power decreases.

Leveraging this understanding, we created isolated quasi-1D NV-center chains with 1 GeV Au ions at a low fluence 1 × 108 ions/cm2 in diamond containing <200 ppm nitrogen—yielding dense NV centers spaced by a few nanometers along single ion tracks, extending over tens of micrometers to potentially form thousand-qubit registers. Spin characterization via ODMR shows these newly formed NV− centers retain stable coherence times, narrower line widths, and enhanced ESR contrast compared to background NV− ensembles. The observed reduced T1 relaxation times could potentially enable faster spin reset and logic operations. One intriguing next step is to quantify and control the nearest coupling of the NV− centers within the quasi-1D chains, while suppressing the magnetic noise resulted from the spin bath. In addition, we propose it is possible to create 2D sheets of NV− centers for wide-field quantum sensing, by modulating the ion beam path (e.g., sidewall irradiation or patterned apertures). Our results underscore the viability of swift heavy ion irradiation for scalable NV-center engineering and facilitate opportunities in quantum information processing and sensing.

Methods

Sample preparation: SHI irradiation and thermal annealing

Type IIa diamonds (supplier: Element 6) were used in this study with about 1 ppm nitrogen introduced during the chemical vapor deposition growth. Erbium ions were firstly implanted into diamond samples (1 × 1013 cm−2 180 keV). The pre-implanted samples were irradiated at the linear accelerator UNILAC at GSI Helmholtzzentrum (Darmstadt, Germany) using 1.1 GeV U ions (fluence of 1 × 1012 U ions/cm2) and 0.95 GeV Au ions (2.2 × 1012 Au ions/cm2). The samples were covered by a thick honey-comb shaped mask with millimeter sized openings (90% transparency), which allows direct comparison between irradiated and nonirradiated regions during the PL measurements. To enhance the formation of NV− centers, the Au-ion irradiated sample B was thermally annealed in a two-step process and the optical properties were compared after the 1st and the 2nd annealing step. The 1st annealing step was for 1 h at 800 °C in vacuum (10−6 mbar), the 2nd annealing step was for 1 h at 1000 °C in argon atmosphere. To create single individual quasi-1D chain of coupled NV-centers with average spacings of a few nanometers, Type Ib HPHT diamond wafer (supplier: Element 6) with <200 ppm nitrogen impurities) were irradiated by 1 GeV Au ions radiation with a dilute fluence of 1 × 108 ions/cm2 at GSI UNILAC, followed by one hour post annealing under the conduction of 1000 °C, vacuum (<10−4 mbr).

Confocal photoluminescence microscopy

Depth-resolved PL measurements were performed with a custom built confocal PL microscopy, which enables spatially resolved 3D maps of optical-active defects in semiconductor. A 100 × lens with a numerical aperture (NA) of 0.95 was used to focus laser and collect PL signal. To enhanced the spatial resolution, the PL signal was refocused at the conjugate focal plane, where a pinhole with 100 μm aperture diameter was used to select the center area of excitation spot. The sample was mounted on a 3D piezo-nano-positioning sample stage. A spectrometer with 150 groves/mm grating and an electron-multiplied CCD were used to acquire the PL spectrum of color centers. The excitation wavelength of laser was 532 nm. To convert from the stage position coordinate to the actual depth where the diamond is optically excited, probe depth z was refractive index corrected by multiplying the stage position zstage by the index of refraction in diamond, n = 2.4, as z = nzstage.

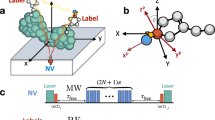

Optically detected magnetic resonance measurement

NV− center electron spin resonance and Rabi measurements were performed with a custom built platform of optically detected magnetic resonance. A 532 nm continuous wave laser with several tens of mW output power was used to excited NV− centers. Meanwhile, microwave (MW) pulses were generated by a digital delay/pulse generator and amplified by a high-power amplifier, and subsequently delivered to the NV-centers in diamond via a loop antenna. To implement the ESR and Rabi laser-MW pulsed sequence protocol, a PulseBlaster card synchronized the laser and MW pulses and controlled the data acquisition unit, which captured and processed the fluorescence signals to determine the NV− spin state. The laser was modulated by an acousto-optic modulator for timing control. NV fluorescence was collected through microscope lenses and directed to an avalanche photo diode for detection, with a band-pass filter separating the NV− fluorescence from the laser light.

In Rabi measurements, the MW frequency was tuned to the electron spin resonance of NV− centers, and a MW pulse of varying duration was applied while the resulting fluorescence of NV− centers was recorded. Periodic fluorescence oscillations appeared because the spin state rotation under resonant MW driving. And from these oscillations, the π/2 and π pulse durations were extracted for subsequent T1 and T2 measurements. To measure T1 (longitudinal relaxation), the NV− centers were first polarized into the ms = 0 state by a laser pulse. A dark interval of varying length was then inserted before a readout laser pulse was applied. During this interval, the NV− spin population relaxed from the polarized ms = 0 state toward the thermal equilibrium, causing an exponential decay in fluorescence. By varying the interval length and fitting the fluorescence decay, the longitudinal relaxation time (T1) was obtained. T2 (transverse relaxation) was measured using the typical spin-echo (Hahn-echo) sequence (π/2 - τ - π - τ - π/2), where after the first π/2 pulse, the spin state evolved freely for time τ, underwent a π pulse, and evolved again for τ before the final π/2 pulse was applied. By sweeping τ, the fluorescence decay of multiple spin-echo envelop resulted from the phase decoherence was recorded to determine the spin coherence time T2. The \({T2}^{* }\) was obtained by the exponential fit of the first spin-echo fluorescence decay.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors Wei Liu and Thomas Schenkel upon reasonable request.

References

Lang, M., Djurabekova, F., Medvedev, N., Toulemonde, M. & Trautmann, C. 1.15-Fundamental phenomena and applications of swift heavy ion irradiations. In Comprehensive Nuclear Materials, Vol. 1 (2nd ed) (eds Konings, R. J. M. & Stoller, R. E.) 485–516 (Elsevier, 2020).

Amekura, H. et al. Latent ion tracks were finally observed in diamond. Nat. Commun. 15, 1786 (2024).

Lake, R. E. et al. Direct formation of nitrogen-vacancy centers in nitrogen doped diamond along the trajectories of swift heavy ions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 084002 (2021).

Rondin, L. et al. Magnetometry with nitrogen-vacancy defects in diamond. Rep. Prog. Phys. 77, 056503 (2014).

Barry, J. F. et al. Sensitivity optimization for nv-diamond magnetometry. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 015004 (2020).

Zhang, T. et al. Toward quantitative bio-sensing with nitrogen–vacancy center in diamond. ACS Sens. 6, 2077–2107 (2021).

Fu, K.-M. C., Iwata, G. Z., Wickenbrock, A. & Budker, D. Sensitive magnetometry in challenging environments. AVS Quantum Sci. 2, 044702 (2020).

Bakhshandeh, S. Quantum sensing goes bio. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 254–254 (2022).

Liu, G.-Q., Liu, R.-B. & Li, Q. Nanothermometry with enhanced sensitivity and enlarged working range using diamond sensors. Acc. Chem. Res. 56, 95–105 (2023).

Dolde, F. et al. Room-temperature entanglement between single defect spins in diamond. Nat. Phys. 9, 139–143 (2013).

Jarmola, A., Acosta, V., Jensen, K., Chemerisov, S. & Budker, D. Temperature-and magnetic-field-dependent longitudinal spin relaxation in nitrogen-vacancy ensembles in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 197601 (2012).

Bauch, E. et al. Ultralong dephasing times in solid-state spin ensembles via quantum control. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031025 (2018).

Taminiau, T. H., Cramer, J., van der Sar, T., Dobrovitski, V. V. & Hanson, R. Universal control and error correction in multi-qubit spin registers in diamond. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 171–176 (2014).

Waldherr, G. et al. Quantum error correction in a solid-state hybrid spin register. Nature 506, 204–207 (2014).

Rong, X. et al. Experimental fault-tolerant universal quantum gates with solid-state spins under ambient conditions. Nat. Commun. 6, 8748 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Quantum simulation of helium hydride cation in a solid-state spin register. ACS nano 9, 7769–7774 (2015).

Pezzagna, S. & Meijer, J. Quantum computer based on color centers in diamond. Appl. Phys. Rev. 8, 011308 (2021).

Hensen, B. et al. Loophole-free bell inequality violation using electron spins separated by 1.3kilometres. Nature 526, 682–686 (2015).

Tsuji, T., Ishiwata, H., Sekiguchi, T., Iwasaki, T. & Hatano, M. High growth rate synthesis of diamond film containing perfectly aligned nitrogen-vacancy centers by high-power density plasma CVD. Diam. Relat. Mater. 123, 108840 (2022).

Greengard, S. Qubit devices inch toward reality. Commun. ACM 64, 11–13 (2021).

Hamilton, M. & Nguyen, L. Heterogeneous integration technologies for scaled quantum information processing systems. IEEE EPS eNews (IEEE, 2023).

Onoda, S. et al. Diffusion of vacancies created by high-energy heavy ion strike into diamond. Phys. status solidi (a) 214, 1700160 (2017).

Onoda, S. et al. New application of NV centers in cvd diamonds as a fluorescent nuclear track detector. Phys. status solidi (a) 212, 2641–2644 (2015).

Bose, S. Quantum communication through an unmodulated spin chain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 207901 (2003).

Estarellas, P. Spin chain systems for quantum computing and quantuminformation applications. Ph.D. thesis (University of York, 2018).

Akselrod, M. & Kouwenberg, J. Fluorescent nuclear track detectors–review of past, present and future of the technology. Radiat. Meas. 117, 35–51 (2018).

Marshall, M. C., Turner, M. J., Ku, M. J., Phillips, D. F. & Walsworth, R. L. Directional detection of dark matter with diamond. Quantum Sci. Technol. 6, 024011 (2021).

Liu, J., Muinos, H. V., Nordlund, K. & Djurabekova, F. Molecular dynamics simulation of the effects of swift heavy ion irradiation on multilayer graphene and diamond-like carbon. Appl. Surf. Sci. 527, 146495 (2020).

Acosta, V. M. et al. Diamonds with a high density of nitrogen-vacancy centers for magnetometry applications. Phys. Rev. B-Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 80, 115202 (2009).

Cajzl, J. et al. Erbium luminescence centres in single-and nano-crystalline diamond-effects of ion implantation fluence and thermal annealing. Micromachines 9, 316 (2018).

James Ziegler, J. B., Ziegler, M.D. Softerware website of the stopping and range of ions in matter http://www.srim.org/index.htm (2008).

Subedi, S., Fedorov, V., Mirov, S. & Markham, M. Spectroscopy of gr1 centers in synthetic diamonds. Opt. Mater. Express 11, 757–765 (2021).

Mildren, R. P., Butler, J. E. & Rabeau, J. R. Cvd-diamond external cavity raman laser at 573nm. Opt. Express 16, 18950–18955 (2008).

Jeske, J. et al. Stimulated emission from nitrogen-vacancy centres in diamond. Nat. Commun. 8, 14000 (2017).

Solà-Garcia, M., Meuret, S., Coenen, T. & Polman, A. Electron-induced state conversion in diamond NV centers measured with pump–probe cathodoluminescence spectroscopy. ACS Photonics 7, 232–240 (2019).

Lühmann, T., Meijer, J. & Pezzagna, S. Charge-assisted engineering of color centers in diamond. Phys. Status Solidi (a) 218, 2000614 (2021).

Tersoff, J. Modeling solid-state chemistry: Interatomic potentials for multicomponent systems. Phys. Rev. B 39, 5566 (1989).

Wang, Z., Dufour, C., Paumier, E. & Toulemonde, M. The se sensitivity of metals under swift-heavy-ion irradiation: a transient thermal process. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 6, 6733 (1994).

Rymzhanov, R., Gorbunov, S., Medvedev, N. & Volkov, A. Damage along swift heavy ion trajectory. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 440, 25–35 (2019).

Schenkel, T. et al. Synergy of electronic excitations and elastic collision spikes in sputtering of heavy metal oxides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 4325 (1998).

Nuckols, L. et al. Effects of recoil spectra and electronic energy dissipation on defect survival in 3c-SIC. Materialia 15, 101023 (2021).

Bucher, D. B. et al. Quantum diamond spectrometer for nanoscale NMR and ESR spectroscopy. Nat. Protoc. 14, 2707–2747 (2019).

Rubinas, O. R. et al. Spin properties of NV centers in high-pressure, high-temperature grown diamond. J. Phys. Commun. 2, 115003 (2018).

Mindarava, Y. et al. Efficient conversion of nitrogen to nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond particles with high-temperature electron irradiation. Carbon 170, 182–190 (2020).

Feng, F. et al. Optimizing the density of nitrogen implantation for generating high-density NV center ensembles for quantum sensing. Eur. Phys. J. D. 73, 1–6 (2019).

Shields, B. J., Unterreithmeier, Q. P., de Leon, N. P., Park, H. & Lukin, M. D. Efficient readout of a single spin state in diamond via spin-to-charge conversion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 136402 (2015).

Deák, P., Aradi, B., Kaviani, M., Frauenheim, T. & Gali, A. Formation of nv centers in diamond: a theoretical study based on calculated transitions and migration of nitrogen and vacancy related defects. Phys. Rev. B 89, 075203 (2014).

Bauch, E. et al. Decoherence of ensembles of nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 102, 134210 (2020).

Mrózek, M. et al. Longitudinal spin relaxation in nitrogen-vacancy ensembles in diamond. EPJ Quantum Technol. 2, 22 (2015).

Tetienne, J.-P. et al. Spin relaxometry of single nitrogen-vacancy defects in diamond nanocrystals for magnetic noise sensing. Phys. Rev. B 87, 235436 (2013).

Dwyer, B. L. et al. Probing spin dynamics on diamond surfaces using a single quantum sensor. PRX Quantum 3, 040328 (2022).

Song, X. et al. A statistical correlation investigation for the role of surface spins to the spin relaxation of nitrogen vacancy centers. AIP Adv. 4, 047103 (2014).

Romach, Y. et al. Spectroscopy of surface-induced noise using shallow spins in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 017601 (2015).

Koike, J., Parkin, D. & Mitchell, T. Displacement threshold energy for type iia diamond. Appl. Phys. Lett. 60, 1450–1452 (1992).

Acknowledgements

The work is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, Office of Fusion Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. Work at the Molecular Foundry was supported by the Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. The ODMR experiments were performed at the geoscience quantum sensing laboratory at Berkeley Lab, supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences Division under U.S. Department of Energy Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. The results presented here are based on a UMAT experiment, which was performed at the M-branch of the UNILAC at the GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung, Darmstadt (Germany) in the frame of FAIR Phase-0. F.D., A.L. and C.N. acknowledge the CSC—IT Center for Science, Finland, for computational resources. C.N. gratefully acknowledges Victoriastiftelsen for financial support. F.D. acknowledges the Research Council of Finland project SPATEC (Grant No 349690) for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.S., W.L., A.P. and Q.J. initialized, conceived, and designed the overall research. W.L. performed the depth-resolved PL characterization, ODMR measurements, and diamond thermal annealing. A.L. and C.N. performed the MD simulations and summarized the theoretical results in the manuscript with guidance from F.D. E.B. assisted the depth-resolved PL characterization with inputs from S.A. and K.J. M.T. and C.T. implemented the SHI irradiation. H.O., N.A., S.M. and Z.H. supported the implementation of the ODMR measurement with inputs from R.W. W.L. and T.S. analyzed the results with inputs from all authors. W.L. and T.S. wrote the manuscript with contribution from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, W., Leino, A.A.M., Persaud, A. et al. Optical and spin properties of nitrogen vacancy centers in diamond formed along high-energy heavy ion tracks. Commun Mater 6, 242 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00961-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00961-6

This article is cited by

-

Towards dislocation-driven quantum interconnects

npj Computational Materials (2026)