Abstract

Layered van der Waals crystals of topologically non-trivial and trivial semimetals with antiferromagnetic (AFM) ordering of magnetic sublattice are known to exhibit a negative magnetoresistance that is well correlated with AFM magnetization changes in a magnetic field. This effect is reported in several experimental studies with EuFe2As2, EuSn2As2, EuSn2P2, etc., where the resistance decreases quadratically with field by about 5% up to the spin-polarization field. Although this effect is well documented experimentally, its theoretical explanation is missing up to date. Here, we propose a theoretical mechanism describing the observed magnetoresistance that is inherent in AFM metals and is based on violation the binary \({\hat{T}}_{2}\) symmetry. It is almost isotropic to the field and current directions, contrary to the known mechanisms such as giant magnetoresistance and chiral anomaly. The proposed intrinsic mechanism of magnetoresistance is strong in a wide class of the layered AFM-ordered semimetals. The theoretically calculated magnetoresistance is qualitatively consistent with experimental data for crystals of various composition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topology incorporated with magnetism provides a fertile playground for studying unique quantum states and therefore attracts tremendous attention. Topological aspects and related electronic phenomena occuring in antiferromagnetic (AFM) materials are among the central topics in condensed matter physics. Clarifying the underlying mechanisms that govern mutual effects of the magnetic ordering, broken symmetry, exchange and spin-orbit coupling on magnetotransport in layered crystals is crucial for comprehending emergent properties and phenomena in spintronics.

The vast majority of layered AFM crystals of topological insulators (TI) and semimetals exhibit such characteristic feature as a negative magnetoresistance (NMR) in external magnetic field. This effect has recently attracted a great deal of interest, as it is related with chiral anomaly in Dirac and Weyl semimetals1,2, with Chern insulators and anomalous quantized Hall state in AFM topological insulators3,4. Indeed, for topological semimetals (Na3Bi, TaS, Cd3As2), a large NMR results from the chiral anomaly5,6 and appears when electric field is applied nearly parallel to magnetic field. This NMR is highly anisotropic and its sign changes as the angle between the magnetic field H and current increases to π/25. In the topological insulator MnBi2Te4, a huge NMR4 occurs as a result of the topological phase transition from AFM TI to a ferromagnetic Weyl semimetal in external field.

On the other hand, a number of layered crystals of topologically trivial AFM semimetals (EuSn2As27,8,9, EuSn2P210, CaCo2As211, CsCo2Se212, etc.) exhibit isotropic negative magnetoresistance (NIMR) for transport both along and across the layers. There is no satisfactory treatment of such isotropic NMR. Particularly, the magnetoresistance (MR) related with magnon scattering is negative only in ferromagnets and arises from the magnetic-field-induced suppression of scattering13. For antiferromagnets, the magnon scattering causes positive MR14,15. (We presume that for our case of the easy magnetization ab plane, the H∥ab and H∥c field orientations correspond, in notations of Ref. 15, to the easy axis H∥z, and perpendicular to it H∥x, respectively.) that originates from a field-induced increase in spin fluctuations.

Negative giant MR (GMR) is well known for the Fe/Cr superlattices where resistance decreases as magnetization in the neighbouring Fe-layers turns with external magneticfield from antiparallel to parallel16,17. For ideal interfaces, GMR should develop for charge transport across the layers17. In experiments with artificially deposited Fe/Cr layers16, a weaker NMR is observed also for current along the layers and is associated with diffuse scattering at layer boundaries18,19. Another case, the “colossal” NMR is known for doped manganites and magnetic granular samples17,19,20 where domains due to phase separation effects and misoriented crystallites lead to electron scattering at the boundaries.

In case of high quality single crystals, the scattering by grains, domain or crystallite boundaries is missing; also, there is not much sense to consider roughness of atomic layers. The isotropy of experimentally observed NIMR encourages us to consider scattering by point defects.

In this paper we suggest a mechanism of the intrinsic isotropic NMR that is irrelevant to magnons, magnetic impurities, grain boundaries, layer roughness, and topology, being general to AFM metals and rather strong in a wide class of the anisotropic layered crystals of AFM metals and semimetals. These materials exhibit a negative magnetoresistance that is tightly correlated with the magnetization field dependence8,9,10,21,22. The magnetization changes linearly with external field and sharply saturates above a field of complete spin polarization Hsf (see Supplementary Note 1); the Hsf field is often called spin-flip field for the easy axis case. Though the close relationship between magnetization and magnetoresistance is known also for GMR and colossal MR (CMR)17,20, the suggested mechanism is completely different.

We test our model by comparing it with experimentally measured magnetoresistance in EuSn2As2 that has a topologically trivial BS (see Supplementary Note 2). For this representative compound, at T < 24 K the magnetic Eu-sublattice experiences magnetic ordering into the A-type AFM structure where Eu magnetic moments lie in the easy ab-plane and rotate by π from layer to layer along the z-axis (see Fig. 1a, and also Suplementary Note 3).

Synchronous with magnetization, the diagonal resistivity decreases approximately parabolically with field as δρxx(H) ∝ − αH2. At higher fields H > Hsf, magnetotransport perpendicular to the field sharply changes from NMR to a conventional positive magnetoresistance. Such NMR in layered AFM crystals, closely correlated with the field dependence of magnetization M(H)8,9,10,21, was discussed previously in terms of either nontrivial topological properties, or in terms of scattering by domains, grain boundaries etc., with no detailed theoretical consideration.

In this paper we address the issue of the origin of negative isotropic MR. Specifically, we (i) propose a model where NIMR universally originates from the enhancement of electron scattering in AFM crystals, (ii) substantiate this proposal using the density functional theory (DFT) calculations of spin polarized charge distribution, and (iii) compare the model quantitatively with our experimental data for NIMR in EuSn2As2 and qualitatively – with other compounds of the same class of layered AFM crystals.

Results

Model and a qualitative consideration

The main idea of the proposed NIMR mechanism is as follows. The AFM order violates the binary \({\hat{T}}_{2}\) symmetry 1 ↔ 2 between two magnetic sublattices (adjacent layers in EuSn2As2, see Fig. 1). This \({\hat{T}}_{2}\) symmetry to the permutation of AFM sublattices is irrelevant to topology and means equal energies and weights of electron eigenfunctions on each AFM sublattice. Its violation leads to spatial redistribution of wave functions (WF) \({\psi }_{\sigma }\left({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}\right)\) for two different spin projections (σ = ↑↓) and to their concentration near the corresponding AFM sublattices. As a result of this WF squeezing, the electron scattering rate23 by short-range crystal defects or δ-correlated disorder increases already in the Born approximation:

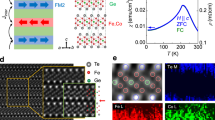

Figure 2 schematically illustrates this \({\hat{T}}_{2}\)-symmetry violation of electron eigenfunctions by AFM order and the resulting enhancement of ∣ψσ∣4(r) entering the scattering rate in Eq. (1).

a Schematic color illustration of the spin-up (red) and spin-down (blue) wave function distribution along the z-axis in the half-cell of the c/2-size. cb denotes the distance between the two spin-split WF maxima. Color intensity represents the WF magnitude. Red circles show Eu atoms, and arrows -- their magnetization direction in the AFM state. b Schematic picture of the fourth power ψ4(z) of electron WF given by Eq. (6), entering the scattering rate in Eq. (1). The asymmetry parameter γ ≡ Eex/2t0 = 0 (green solid line), γ = −0.4 (dashed red line) and γ = 0.4 (dash-dotted blue line).

As we show below in Eqs. (6) and (11), the degree of \({\hat{T}}_{2}\) symmetry violation, given by Eq. (6), and the corresponding 1/τ enhancement, given by Eq. (11), depend on the ratio γ = Eex/2t0 of the exchange splitting Eex of conduction electron bands to their hopping amplitude t0 between the opposite AFM sublattices (Fig. 1). In the main order in γ this relative enhancement of 1/τ is

While t0 is determined by the band structure and does not considerably depend on magnetic field H, the exchange splitting \({E}_{ex}\propto {L}_{AFM}\left(H\right)\) decreases with H according to the mean-field theory (see, e.g. Eq. 3 of Ref. 24 and Eq. 24 of Ref. 25):

Here LAFM is the AFM order parameter, i.e. the difference of magnetization M1,2 of two AFM sublattices: LAFM = M1 − M2. Eq. (3) can be derived as follows. In a sufficiently large field H≤Hsf, the AFM order parameter LAFM ⊥ H26. In this range the field also causes a net magnetization M = M1 + M2 = χH, coming mainly from the nonzero averaged spins 〈S〉 of magnetic atoms, Eu in our case. The corresponding magnetic susceptibility χ is approximately constant as a function of field at temperature T < TN below the Neel temperature TN26: χ(H) ≈ const. This is also confirmed by direct AC susceptibility and DC magnetization27 in a field H≤Hsf. The total spin of each magnetic ion is fixed, \({S}_{| | }^{2}+{S}_{\perp }^{2}={\hat{S}}^{2}=S(S+1)\), where S∣∣ and S⊥ are its components parallel and perpendicular to magnetic field, giving the net magnetization M and AFM order parameter LAFM correspondingly. Then LAFM/M = 〈S⊥〉/〈S∣∣〉 leads to

and to the right side of Eq. (3).

For our model of negative magnetoresistance, we only need the exchange interaction between the magnetic ions (or even their sublattices) and conduction electrons. It is nearly a point-like Heisenberg interaction \(-{{{\mathcal{J}}}}{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}{{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}}\) between the spin S of magnetic ion and the spin σ/2 of conduction electrons, because the exchange coupling is strong only where the wave functions of conduction electrons overlap with the localized electrons of magnetic ions. The wave function ψσ(r) of conduction electron is delocalized and extended to many magnetic ions. Therefore, ψσ(r) feels an average spin 〈Si〉 of magnetic ions on each AFM sublattice i, which is proportional to its total magnetization Mi. Hence, instead of considering the interaction between individual Eu atoms and electrons, we only need the mean-field average spin 〈Si〉 ∝ Mi, which creates a spin-dependent potential for conduction electrons.

The spin S of magnetic atoms is only reoriented by magnetic field, leaving LAFM⊥H over the intire range H < Hsf. Hence, the absolute value S = ∣S∣ of spin moment and of the exchange-splitting of conducting electrons is independent of magnetic field. This splitting from electron exchange interaction is usually calculated using the DFT in collinear form, especially for Eu with half-filled 4f orbitals carrying a local moment. We denote this splitting Eex0 = Eex(H = 0) in Eq. (3); below from our DFT calculations we estimate it to be Eex0 ≈ 30 meV for EuSn2As2. The exchange splitting Eex = Eex(H), entering our NIMR mechanism and Eqs. (2)-(3), is the difference of exchange energy on two different AFM sublattices. The AFM order parameter LAFM also gives the difference between averaged spin orientation of magnetic atoms on these two AFM sublattices, which determines the exchange splitting Eex = Eex(H). Hence, LAFM(H) ∝ Eex(H), as we write in the left part of Eq. (3).

Indeed, for the NIMR effect, coming from the redistribution of ψσ(r) between two AFM sublattices as given by Eq. (6) below, we need the difference of weights of ψσ(r) on two different AFM sublattices. And this difference of weights is proportional to the difference Eex, entering the Hamiltonian in Eq. (5), of the averaged exchange energy J〈Si〉 of conducting electrons on two different AFM sublattices. Since J〈Si〉 ∝ Mi, we get \({E}_{ex}=-{{{\mathcal{J}}}}({{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{{{{\bf{1}}}}}-{{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{{{{\bf{2}}}}})\propto -{{{\mathcal{J}}}}({{{{\boldsymbol{M}}}}}_{{{{\bf{1}}}}}-{{{{\boldsymbol{M}}}}}_{{{{\bf{2}}}}})=-{{{\mathcal{J}}}}{{{{\boldsymbol{L}}}}}_{AFM}\). This gives the left-side part of Eq. (3). This analysis also shows that the low index σ in the wave function ψσ(r) is the projection of conducting-electron spin on the AFM order parameter LAFM.

Eqs. (2) and (3) lead to a parabolic isotropic negative magnetoresistance (NIMR) persisting almost up to the spin polarization field Hsf.

Quantitative consideration

Let us consider quantitatively the electron WF squeezing in the AFM state. The two AFM sublattices are numerated by the index j = 1, 2, and the spin projection on the AFM magnetization axis LAFM is indexed by σ = ± 1 ≡ ↑, ↓. For each quasi-momentum the quantum basis consists of four states, \(\left\vert j,\sigma \right\rangle =\left\{1\uparrow,1\downarrow,2\uparrow,2\downarrow \right\}\), corresponding to wave functions \({\psi }_{j,\sigma }=\left\{{\psi }_{1\uparrow },{\psi }_{1\downarrow },{\psi }_{2\uparrow },{\psi }_{2\downarrow }\right\}\). The usual Zeeman splitting \({E}_{Z}({{{\boldsymbol{H}}}})=\left(\overrightarrow{{{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}}}\cdot \overrightarrow{{{{\boldsymbol{H}}}}}\right)g{\mu }_{B}/2\) in a relevant external magnetic field H ≲ 5T is much smaller than the exchange splitting Eex0 ~ 30 meV and is neglected below. The neglected spin-orbit coupling ESOC ≲ 5 meV (see Supplementary materials, Note 4) is also much smaller than the exchange splitting Eex0 and, additionally, averages to zero after the integration over electron momentum in the first order of perturbation theory. Then for each electron quasi-momentum k the AFM-sublattice part of electron Hamiltonian is given by the 4 × 4 matrix, which decouples into two 2 × 2 matrices:

Here the diagonal terms are the energy shifts due to the exchange interaction with AFM magnetization, and the off-diagonal term \({t}_{0}={t}_{0}^{* }\), the intersublattice electron transfer integral, determines the electron hopping rate between AFM sublattices. The diagonalization of Hamiltonian (5) gives two eigenvalues \({\varepsilon }_{\pm,\sigma }=\mp \sqrt{{E}_{ex}^{2}/4+{t}_{0}^{2}}\) and the corresponding normalized wave functions

where ψ1, 2 are the electron wave functions “localized” mostly on the first and second AFM sublattices. Without the AFM order, i.e. at γ ∝ Eex = 0, this gives the simple electron spectrum \({\varepsilon }_{\pm,\sigma }^{0}=\mp {t}_{0}\) and eigenstates \({\psi }_{\pm,\sigma }^{0}=\left({\psi }_{2}\pm {\psi }_{1}\right)/\sqrt{2}={\psi }_{\pm }^{0}\), which are the symmetric and antisymmetric superpositions of electron states on sublattices 1 and 2 with equal WF weights on each AFM sublattice. From Eq. (6) we see that the AFM order lifts this symmetry, making the eigenfunction amplitude larger at one of the two sublattices at γ ≠ 0 (see Fig. 2). This enhances the electron scattering rate in Eq. (1), as seen from Fig. 2 and estimated below.

In the Born approximation, i.e. the second-order perturbation theory in the impurity potential, the electron scattering rate is given by the Fermi’s golden rule23:

where the index \({{{\boldsymbol{n}}}}\equiv \left\{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}},\beta,\zeta,\sigma \right\}\) numerates quantum states, β numerates electron bands at the Fermi level coming from different atomic orbitals in multiband metal, ζ = ± denotes two eigenstates in Eq. (6), i numerates impurities, εn is the electron energy in state n, and δ(x) is the Dirac delta-function. The additional index ζ = ± doubles the number of quantum states per each quasimomentum k, which compensates the folding in half of the first Brillouin zone by the commensurate AFM.

The short-range impurities or other crystal defects in solids are usually approximated by the point-like potential \({V}_{i}\left({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}\right)=U\delta \left({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}-{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{i}\right)\). Here we omit the spin index σ because it is conserved by the potential scattering. The corresponding matrix element of electron scattering is \({T}_{{{{{\boldsymbol{n}}}}}^{{\prime} }{{{\boldsymbol{n}}}}}^{(i)}=U{{{\Psi }}}_{{{{{\boldsymbol{n}}}}}^{{\prime} }}^{* }\left({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{i}\right){{{\Psi }}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{n}}}}}\left({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{i}\right)\), where \({{{\Psi }}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{n}}}}}\left({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}\right)={\psi }_{\beta \zeta \sigma }\left({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}\right)\exp \left(i{{{\boldsymbol{kr}}}}\right)\) is the electron Bloch wave function with periodic \({\psi }_{\beta \zeta \sigma }\left({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}\right)\). For point-like potential the matrix element \({T}_{{{{{\boldsymbol{n}}}}}^{{\prime} }{{{\boldsymbol{n}}}}}^{(i)}\) does not depend on electron momentum \({{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}^{{\prime} }\). Then the summation over \({{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}^{{\prime} }\) with the δ-function in Eq. (7) gives the electron density of states (DoS) \({\nu }_{F\beta \zeta \sigma }\equiv {\nu }_{\beta \zeta \sigma }\left({\varepsilon }_{F}\right)\) at the Fermi energy εF per one spin component σ and per one subband. The total DoS per one spin νF = ∑βζνFβζσ does not depend on σ because the total time-reversal symmetry is conserved by AFM, as the simultaneous change of spin index σ = ±:1 and of AFM sublattice 1 ↔ 2 (layer in our case) does not change the system. If the impurities are uniformly and randomly distributed in space, the sum over impurities rewrites as an integral over impurity coordinate23: ∑i → nimp∫d3ri, where nimp is the impurity concentration. Then Eq. (7) becomes

where the integral over one elementary cell

According to Eq. (6), for each band β the WFs of two opposite subbands ζ = ± shift toward opposite AFM sublattices. These states are separated by large energy

Hence, rather commonly a single subband ζ appears at the Fermi level, i.e. \({\nu }_{F\beta {\zeta }^{{\prime} }\sigma }=0\) for \({\zeta }^{{\prime} }\ne \zeta\). Then Eqs. (8),(9) confirm Eq. (1). In fact, it holds even if there are several conducting bands β but only one subband ζ is occupied, because the WF in Eq. (6) does not considerably depend on the band β and enters in the fourth power in Eq. (9). Eqs. (8),(9) approximately give Eq. (1) even when there are several subbands ζ = ± on the Fermi level, but their DoS νFβζσ differ strongly. The latter happens in Dirac semimetals, where the DoS \({\nu }_{\beta \zeta }\left({\varepsilon }_{F}\right)\propto {\varepsilon }_{F}^{d-1}\) strongly depends on energy εF and where the subband splitting Δεζ ≳ εF.

For the reason explained above, we now consider the case of only one subband ζ = + at the Fermi level and estimate the difference δI of two integrals (9) with and without AFM, i.e. for γ ≠ 0 and γ = 0. The host crystal lattice has the \({\hat{T}}_{2}\) symmetry, therefore \(\int{\psi }_{1}^{4}\left(z\right)dz=\int{\psi }_{2}^{4}\left(z\right)dz\). For simplicity, we also assume that the overlap of the wave functions on different AFM sublattices is negligible, i.e. ψ1ψ2 ≪ ∣ψ1∣2, and we neglect the product ψ1ψ2 ≈ 0. The main conclusion remains valid also when ψ1ψ2 ~ ∣ψ1∣2, but the calculations are more cumbersome.

Without AFM order, substituting Eq. (6) at γ = 0 to the integral (9), we obtain \({I}_{0}=\int{d}^{3}{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}| {\psi }_{+}^{0}{| }^{4}dz\approx \int{d}^{3}{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}{\psi }_{1}^{4}/2\). The difference \(\delta I\equiv I-{I}_{0}=\int{d}^{3}{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}\left(| {\psi }_{+}{| }^{4}-| {\psi }_{+}^{0}{| }^{4}\right)\) determines the correction to electron mean free time τ according to Eqs. (1) or (8) and, hence, the NIMR effect. After substituting Eq. (6) at ψ1ψ2 ≪ ∣ψ1∣2 it reduces to

At γ2 ≪ 1 Eq. (11) simplifies to δI ≈ γ2I0 ≈ γ2I, and substituting Eqs. (11) and (3) to (8) we obtain the relative increase of resistivity due to the AFM ordering

Contrary to the NMR caused by chiral anomaly in Weyl semimetals and to the GMR in layered heterostructures, this increase of resistivity is isotropic. Therefore, our NIMR mechanism applies both for the interlayer and intralayer transport in layered conductors, and only slightly depends on the magnetic field direction due to a magnetic anisotropy solely.

Classical positive magnetoresistance

At H > Hsf the obtained NIMR correction (12) disappears, and for the current J perpendicular to magnetic field direction one returns to the usual classical positive magnetoresistance (CPMR) in multiband conductors due to impurity scattering, which is parabolic at low field when ωcτ ≪ 128:

where ωc = eH/(m*c) is the cyclotron frequency and τ - the scattering time for the dominant band28.

Combining Eqs. (12) and (13) gives the schematic MR curve illustrated in Fig. 3a, which resembles very much typical experimental data measured with the representative compound EuSn2As2 (see Fig. 4a). The sharp transition from negative to positive magnetoresistance at H = Hsf happens because our NIMR effect, which is stronger than the classical positive magnetoresistance in A-type AFM layered metals, exists only in the AFM state at H < Hsf.

a Magnetoresistance curve given by Eqs. (12) and (13) at Eex0/2tz = 0.23 and \({[{\omega }_{c}\tau (H = {H}_{{{{\rm{sf}}}}})]}^{2}=0.2\). b The maximal possible relative value of the proposed NIMR effect as a function of γ0 = Eex0/2t0, plotted using Eqs. (11) or (12). It saturates at 50% for γ0 ≫ 1, when resistivity drops by half.

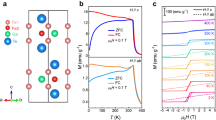

a Examples of the normalized magnetoresistance \(\left.R(H)/R(0)\right)\) vs normalized field (H/Hsf) for two orientations of the bias current, in-plane Rab and perpendicular to the plane Rc, and for two magnetic field directions, H∥(ab) and H∥c. Data are taken at T = 2–3 K. b Magnetization M(H) dependences for two field orientations, H∥ab and H∥c. The nonlinearity of M(H∥ab) in low fields is related with spin canting and spin-flop28. Vertical arrows depict Hsf value for two field orientations.

It is worth of noting, the simplified model, Eq. (12), is the lowest order theory. Closer to the spin polarization transition, at H → Hsf, higher-order magnetization fluctuation effects may cause a faster decrease of \({L}_{AFM}\left(H\right)\) than that given by Eq. (3).

Comparison of the model with experimental data

In isotropic 3D AFM metals, the proposed NIMR mechanism is usually very weak, because the ratio γ = Eex/2t0 ≪ 1. Indeed, Eex ≲ 0.1 eV, while 2t0 ~ 1 eV is comparable to the bandwidth. However, in strongly anisotropic layered AFM semimetals the ratio γ = Eex/2t0 ~ 1, because the interlayer transfer integral t0 ≲ 0.1 eV in van-der-Waals or other layered compounds is also small.

To compare the presented theory with experimental data, we performed magnetization and magnetoresistance measurements with EuSn2As2 bulk single crystals.

The normalized R(H)/R(0) magnetoresistance and magnetization M(H) dependences are shown in Fig. 4 for various field and current directions, H∥c, H∥(ab), J∥c, J∥(ab), at our lowest temperature T ≈ 2 K ≪ TN ≈ 24 K. More detailed magnetization data for various temperatures are presented in Fig. S1 of Supplementary Note 1.

As field exceeds Hsf, the NIMR hump changes sharply to the conventional smooth parabolic rise. The sharp transition between the negative and positive magnetoresistance (i.e. the R(H) minimum) coincides with the sharp magnetization saturation at H = Hsf for both field directions (Fig. 4a, b), consistent also with previous studies8,9,27,29,30. Comparing this data with the presented first-order in \({({\omega }_{c}\tau )}^{2}\) model, we conclude that the model correctly captures the main features: approximately parabolic NMR, its magnitude, and a sharp transition to the conventional CPMR. One can also see in Fig. 4a that CPMR is much weaker for J perpendicular to the layers, than along the ab plane, and is almost missing for J∥H. This observation is in a qualitative agreement with the simple treatment of CPMR, Eq. (13), and with zero-field conduction anisotropy in van der Waals (vdW)-type layered crystal28. The observed NIMR is larger for J∥H than for J⊥H just by the magnitude of this CPMR.

The measured NIMR (see Fig. 4a and also refs. 10,11,12) looks somewhat more flat than the parabolic dependence (Eq. (12) and Fig. 3a). We presume that flattening of the data in low fields may be caused by magnon scattering that in AFM state results in a positive MR14,15. This scattering mechanism is beyond the framework of our first order theory.

In our measurements on EuSn2As2 crystals, the magnetoresistance δρ/ρ drops by about 5–6%, as shown in Fig. 4. According to Eq. (12) this drop corresponds to

We now compare this ratio with our DFT calculations and ARPES data for Eex0 and 4t0. From the DFT calculations we found Eex0 ≈ 30 meV level splitting for EuSn2As228. Substituting this to Eq. (14) one gets t0 ≈ 65 meV. The ARPES data28,31 do not have sufficient energy resolution to measure the bilayer splitting and t0 directly. However, the t0 value can also be roughly estimated from the observed resistivity anisotropy ρzz/ρxx ≈ 13028 and the width of the in-plane energy band 4tx ≈ 1.9 eV, which is taken from the ARPES data and from the DFT calculation. As a result, we obtain the lowest estimate \({t}_{0}\approx {t}_{x}/\sqrt{{\rho }_{xx}/{\rho }_{zz}}\approx 42\) meV, which is in a reasonable agreement with t0 ≈ 65 meV determined from Eq. (14).

Discussion

Now we check whether our assumption of complete ζ-subband polarization is valid for EuSn2As2. According to the DFT calculations28, in EuSn2As2 there are two electron bands with εF ≈ 55 meV and εF ≈ 100 meV and two hole bands with εF ≈ 65 meV and εF ≈ 80 meV. Substituting t0 ≈ 50 meV and Eex0 ≈ 30 meV to Eq. (10) we get the ζ-subband splitting Δεζ ≳ 100 meV > εF for all Fermi-surface pockets. Hence, in EuSn2As2 all electronic bands at the Fermi level are completely subband-polarized, and the above analysis of the NIMR effect is applicable to the experimental data in EuSn2As2.

In order to substantiate our model of opposite spin polarization of conducting electrons on neighboring SnAs layers, we performed the ab-initio DFT calculation of spin-polarized electron density distribution. Our results are shown in Fig. 5, where the yellow (turquoise) isosurfaces limit the real-space areas filled with the same color of positive (negative) electron spin density exceeding a fixed absolute value. As we assumed in our model and illustrated in Fig. 2, the neighboring SnAs layers indeed have opposite spin polarization of conducting electrons. This spin polarization in EuSn2As2 is small, ~0.1% of total electron density, but it is peaked at the Fermi level and strongly affects the electron scattering rate according to the above analysis.

The spin-orbit coupling (SOC) is ignored in our model because the corresponding term ESOC in electron energy is usually much smaller than the exchange coupling Eex0. A weak spin-orbit coupling gives a perturbative correction to the predicted NIMR effect, which is small by the parameter ESOC/Eex0 ≪ 1 and does not affect our NIMR mechanism considerably. Moreover, the spin-orbit term in the Hamiltonian is averaged over electron momenta to almost zero in the first order of perturbation theory and affects only in its next orders. Hence, even at ESOC/Eex0 ~ 1 our NIMR mechanism survives, because it gives the effect averaged over all electron quasi-momenta and contains only the exchange splitting. Of course, at ESOC/Eex0 ≳ 1 our NIMR mechanism quantitatively modifies, which requires further investigation. However, in the studied compound EuSn2As2 the exchange splitting Eex0 ≈ 30meV, while the spin-orbit coupling ESOC ≲ 5 meV ≪ Eex0, as follows from our DFT calculations (see Supplementary Note 4). Hence, we can safely neglect the SOC.

The influence of the redistribution of spin-density of conduction electrons on the exchange interaction between the Eu atoms is also ignored. This redistribution may only slightly affect the RKKY interaction between the Eu atoms. The redistribution of spin density of conduction electrons by AFM order is small by parameter γ ≪ 1, while their charge density remains practically unchanged. Moreover, the main contribution to the exchange interaction between the Eu atoms comes from the direct exchange and superexchange coupling via intermediate localized electrons of Sn and As orbitals rather than from the RKKY mechanism. This can be estimated directly or concluded from the weak dependence of the AFM coupling on the electron density tuned by pressure29 in EuSn2As2 or by doping in a sister compound EuIn2As232.

Our ARPES measurements and band structure calculations for bulk EuSn2As228 show no band crossings and Dirac points at the Fermi level (see Supplementary Note 4), and are consistent with calculations of Ref. 7. The magnetotransport measurements also showed that δR(H)/R(0) is almost independent of the field direction H∥ab or H∥c, of the charge transport direction, in-plane Rab(H) or normal to the plane Rc(H) (see Fig. 4 and Ref. 28). NIMR is also independent of the angle between the electric and magnetic field in the easy ab-plane28 (see Supplementary Note 5). These results exclude the axion insulator origin of NIMR in EuSn2As2. The similarity of NIMR in various materials also indicates insignificance of the Dirac states close to EF, such as in EuSn2P210.

Neither our, nor other ARPES measurements and DFT band structure calculations for EuSn2As27,28,33 reveal Dirac cones at EF. In addition, resistivity temperature dependence for EuSn2As2 in all works8,9,27,28 shows a monotonic decrease almost down to TN, thus evidencing a conventional semimetalic-, rather than topological insulator-type behavior, such as suggested in Ref. 31. These results provide solid ground for the applicability of our model to EuSn2As2.

The independence of NIMR on the sample thickness (from 60 nm to 0.2 mm)34 indicates that NIMR does not come from scattering by large-scale lattice defects (such as misfit dislocations, misoriented grains), and is irrelevant to the zero-field electron scattering rate 1/τ0, since these parameters are to be different for various samples, for the bulk crystal and exfoliated flakes a few monolayer thick. Whereas the NIMR magnitude is about the same for all studied samples and for various field directions, its shape for some samples in low fields looks somewhat more flattened, that might be caused by a minor positive MR contribution due to magnon scattering28.

The proposed magnetoresistance model is widely universal

The approximately parabolic and isotropic negative magnetoresistance measured in this work is similar to that observed earlier in EuSn2As29,29, and in sister materials – EuSn2P210, CaCo2As211, and CsCo2Se212. We, therefore, believe that our model is applicable to the listed layered AFM-ordered compounds. It may also be partially applicable to EuFe2As2, though the in-plane properties of this compound are affected by Fe-moments stripe ordering21,22, which causes anisotropy of NMR.

In order to illustrate the universality of the proposed mechanism, we show below the magnetoresistance δR(H) data for several vdW layered compounds in the AFM state (i.e. at T < TN) and compare them qualitatively with Eq. (12). In all cases, the MR data scale with field Hsf of magnetization saturation, where the Hsf value is taken from the magnetization measurements. As for the magnitude of NIMR effect, since (Eex0/2t0)-value is unavailable in the published papers, it was used as a adjusting parameter to fit ΔR(H)/R(0) at the point H = Hsf. In all compounds this parameter takes reasonable values. One can see that the predicted parabolic dependence δR(H) qualitatively fits the data; the deviation (e.g., on panel d) may be associated with oversimplified character of the lowest-order model that ignores, e.g., the positive MR from electron-magnon scattering (for discussion, see Ref. 28 and the references therein).

It is worth noting, the panel (f) for EuMg2Bi2 shows a more complex non-monotonic MR in a weak field H ≪ Hsf in addition to the predicted NIMR effect. Nevertheless, the abrupt termination of NIMR at H = Hsf is firmly connected with the magnetization saturation, as well as in all listed above AFM layered semimetals, in agreement with our model. Concerning the low-field R(H) feature in EuMg2Bi2, we note firstly that the magnetoresistance rise in low field is observed for the in-plane transport with magnetic field also aligned in the basal plane. Secondly, the positive MR slowly broadens but does not decay with temperature increasing up to about35 100 K and, finally, it overpowers NIMR at T > 20 K. These two facts do not allow to associate the positive MR at H ≪ Hsf with antilocalization. The EuMg2Bi2 material is considered to be the nodal-line semimetal with linear-dispersing bands at the Fermi level35. Since in this AFM-material the FM-type spin fluctuations have been found to dominate, the sign-changing MR was discussed in Ref. 35 in terms of the competition between the AFM and FM orders. Also, for EuMg2Bi2 the spin-orbit coupling is found to be crucially essential for the band structure at the Fermi level and makes the topological invariant equal to 1; therefore, the influence of non-trivial topology on magnetotransport should be important. Obviously, complex magnetoresistance behavior in this interesting material requires detailed studies.

There are other even more complex behaviors of magnetoresistance in more complex layered materials, for example, in ferromagnetic Weyl semimetal EuCd2As236, in axion insulator EuIn2As22,37, and AFM topological insulators EuMg2Bi235, MnBi2Te4 and MnBi4Te74,38. These cases are beyond the framework of suggested simple model, but even in these compounds our mechanism may considerably contribute to the observed negative magnetoresistance, e.g., as we see from Fig. 6f.

The experimental data are digitized from the published papers (symbols), and model curve are plotted according to Eq. (12) from the main text (dashed lines) for several compounds: a for EuSn2P2 from Fig. 5d of10, b for the compressed EuSn2As2 from Ref. 29 at several pressure values indicated on the panel, c for EuFe2As2 from Fig. 6 of Ref. 21, d for CsCo2Se2 from Fig. 4 of Ref. 12, e for (CaSr)Co2As2 from Fig, 4 of Ref. 11, f for EuMg2Bi2 from Fig. 3 of Ref. 35.

To conclude

we clarified the origin of the negative isotropic magnetoresistance (NIMR) observed in layered AFM semimetals. Specifically, we introduced a magnetoresistance mechanism based on exchange interaction and symmetry violation by AFM and developed a theory describing NIMR over a wide field range up to complete spin polarization. In the proposed theory, the negative magnetoresistance originates from the violation of \({\hat{T}}_{2}\) symmetry and the corresponding stronger localization of electron wave functions on one of the two AFM sublattices depending on electron spin.

The proposed mechanism of the parabolic NIMR is generic for the layered AFM semimetals; the NIMR magnitude is independent of the electron scattering rate and increases as the ratio of the exchange splitting to the transfer integral increases. The proposed model agrees qualitatively with the available data for layered AFM semimetals, such as EuSn2As2, EuSn2P2, EuFe2As2, CaCo2As2, CsCo2Se2, confirming negative isotropic magnetoresistance to be their intrinsic property, irrelevant to defects, domains, and other sample-specific disorder. Although the NIMR magnitude is about the same in all of the above compounds, ≈ 5 − 6%, their relevant energy spectrum parameters (Eex0 and t0) are unknown, which prevents a detailed comparison with theory.

The proposed model of the NIMR effect helps to extract useful information about the electronic structure of AFM compounds. Indeed, according to Eq. (12), the NIMR magnitude gives the parameter γ0 = Eex0/2t0, i.e. the ratio of exchange energy splitting to the hopping amplitude between AFM sublattices. The proposed NIMR effect opens a platform for the detection and study of magnetic ordering using electron transport measurements.

Methods

Experimental

The magnetotransport measurements were preformed with CFMS-16 cryomagnetic system, and using standard 4-terminal AC technique with SR830 lock-in amplifier. Magnetization measurements were done with PPMS-7 SQUID magnetometer.

The EuSn2As2 single crystals were synthesized from homogeneous SnAs (99.99% Sn + 99.9999% As) precursor and elemental Eu (99.95%) in stoichiometric molar ratio (2:1) using the growth method, similar to our previous works30,39. For magnetization measurements we selected bulk crystals of EuSn2As2, ≈ 1 − 2 mm in the ab-plane and ≈ 0.1 mm thick; transport measurements were done both with same bulk crystals and with exfoliated flakes.

DFT calculations

The DFT band structure calculations were performed within the DFT+U approximation in the VASP software package40. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) in the form of the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional41 was employed. The onsite Coulomb interaction of Eu-4f electrons was described with the DFT+U scheme with the Dudarev approach42 (U=5.0 eV same as in Ref. 31).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Pavel D. Grigoriev at grigorev@itp.ac.ru. The source experimental data are provided as a supplementary data file with the paper.

Code availability

No custom code was used to generate or process the data described in the manuscript.

References

Li, H. et al. Negative magnetoresistance in Dirac semimetal Cd3As2. Nat. Commun. 7, 10301 (2016).

Yan, J. et al. Field-induced topological Hall effect in antiferromagnetic axion insulator candidate EuIn2As2. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 013163 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Magnetically controllable topological quantum phase transitions in the antiferromagnetic topological insulator MnBi2Te4. Phys. Rev. B 100, 121103 (2019).

Ge, J. et al. High-Chern-number and high-temperature quantum Hall effect without Landau levels. Natl Sci. Rev. 7, 1280–1287 (2020).

Xiong, J. et al. Evidence for the chiral anomaly in the Dirac semimetal Na3Bi. Science 350, 413–416 (2015).

Huang, X. et al. Observation of the chiral-anomaly-induced negative magnetoresistance in 3D Weyl Semimetal TaAs. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031023 (2015).

Arguilla, M. Q. et al. EuSn2As2: an exfoliatable magnetic layered Zintl-Klemm phase. Inorg. Chem. Front. 4, 378–386 (2017).

Chen, H.-C. et al. Negative magnetoresistance in antiferromagnetic topological Insulator EuSn2As2. Chin. Phys. Lett. 37, 047201 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Magnetic properties of the layered magnetic topological insulator \({{{\rm{Eu}}}}{{{{\rm{Sn}}}}}_{2}{{{{\rm{As}}}}}_{2}\). Phys. Rev. B 104, 054435 (2021).

Gui, X. et al. A new magnetic topological quantum material candidate by design. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 900–910 (2019).

Ying, J. J. et al. Metamagnetic transition in Ca1−xSrxCo2As2(x=0 and 0.1) single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 85, 214414 (2012).

Yang, J. et al. Spin-flop transition and magnetic phase diagram in CsCo2Se2 revealed by torque and resistivity measurements. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 474, 70–75 (2019).

Fontes, M. B. et al. Electron-magnon interaction in RNiBC (R=Er, Ho, Dy, Tb, and Gd) series of compounds based on magnetoresistance measurements. Phys. Rev. B 60, 6781–6789 (1999).

Yamada, H. & Takada, S. Magnetoresistance of antiferromagnetic metals due to s-d interaction. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 34, 51–57 (1973).

Yamada, H. & Takada, S. Magnetoresistance due to electron-spin scattering in antiferromagnetic metals at low temperatures. Prog. Theor. Phys. 49, 1401–1419 (1973).

Baibich, M. N. et al. Giant Magnetoresistance of (001)Fe/(001)Cr Magnetic Superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2472–2475 (1988).

Dagotto, E., Hotta, T. & Moreo, A. Colossal magnetoresistant materials: the key role of phase separation. Phys. Rep. 344, 1–153 (2001).

Camley, R. E. & Barnas, J. Theory of giant magnetoresistance effects in magnetic layered structures with antiferromagnetic coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 63, 664–667 (1989).

Barthélémy, A., Fert, A. & Nguyen Van Dau, F. Giant magnetoresistance. In Buschow, K. J. et al. (eds.) Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology, 3521–3531 (Elsevier, 2001).

Yin, W.-G. & Tao, R. Effective-medium theory of the giant magnetoresistance in magnetic granular samples and doped LaMnO3 perovskites. Phys. Rev. B 62, 550–555 (2000).

Jiang, S. et al. Metamagnetic transition in EuFe2As2 single crystals. N. J. Phys. 11, 025007 (2009).

Sanchez, J. J. et al. Strongly anisotropic antiferromagnetic coupling in EuFe2As2 revealed by stress detwinning. Phys. Rev. B 104, 104413 (2021).

Abrikosov, A. A.Fundamentals of the theory of metals (Elsevier Science Pub. Co, 1988).

Mandel’, V. S., Voronkov, V. D. & Gromzin, D. E. Antiferromagnetic resonance In MnO. Sov. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. Lett. 36, 521 (1973).

Streit, P. K. & Everett, G. E. Antiferromagnetic resonance in EuTe. Phys. Rev. B 21, 169–182 (1980).

Kittel, C.Quantum theory of solids (Wiley, 1963).

Pakhira, S., Tanatar, M. A., Heitmann, T., Vaknin, D. & Johnston, D. C. A-type antiferromagnetic order and magnetic phase diagram of the trigonal Eu spin-\(\frac{7}{2}\) triangular-lattice compound \(\frac{7}{2}\). Phys. Rev. B 104, 174427 (2021).

Pervakov, K. S. et al. Intrinsic Negative Magnetoresistance in Layered AFM Semimetals: the Case of EuSn2As2https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.03971 2411.03971 (2024).

Sun, H. et al. Magnetism variation of the compressed antiferromagnetic topological insulator EuSn2As2. Sci. China Phys., Mech. Astron. 64, 118211 (2021).

Golovchanskiy, I. et al. Magnetic resonances in EuSn2As2 single crystal. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 562, 169713 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Dirac surface states in intrinsic magnetic topological insulators \({{{{\rm{EuSn}}}}}_{2}{{{{\rm{As}}}}}_{2}\) and MnBi2nTe3n+1. Phys. Rev. X 9, 041039 (2019).

Yan, J. et al. Doping-tunable Fermi surface with persistent topological Hall effect in the axion candidate EuIn2As2. Phys. Rev. B 110, 115111 (2024).

Lv, X., Chen, X., Zhang, B., Jiang, P. & Zhong, Z. Thickness-dependent magnetism and topological properties of EuSn2As2. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 4, 3212–3219 (2022).

Maltsev, E. I. et al. Anomalous Hall Effect in EuSn2As2 Thin Flakes. To be published elsewhere.

Marshall, M. et al. Magnetic and electronic structures of antiferromagnetic topological material candidate EuMg2Bi2. J. Appl. Phys. 129, 035106 (2021).

Roychowdhury, S. et al. Anomalous hall conductivity and nernst effect of the ideal weyl semimetallic ferromagnet EuCd2As2. Adv. Sci. 10, 2207121 (2023).

Yu, F. H. et al. Elevating the magnetic exchange coupling in the compressed antiferromagnetic axion insulator candidate EuIn2As2. Phys. Rev. B 102, 180404 (2020).

Tan, A. et al. Metamagnetism of weakly coupled antiferromagnetic topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 197201 (2020).

Eltsev, Y. F. et al. Magnetic and transport properties of single crystals of Fe-based superconductors of 122 family. Phys. Usp. 57, 827–832 (2014).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Dudarev, S. L., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. J. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505–1509 (1998).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank V.N. Menshov for useful discussions and valuable comments. AVS, OAS, and VMP were supported within State Assignment of the research at LPI. PDG acknowledges State Assignment # FFWR-2024-0015. NSP, IAN and IRS acknowledge partial support of the State Assignment # 124022200005-2 of Institute of Electrophysics and # 124020600024-5 of Institute of Solid State Chemistry UB RAS. AVS, OAS, VMP, NSP and IAN acknowledge support from RSCF (grant # 23-12-00307). Experimental work was partly done using equipment of LPI Shared facility Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.D.G. composed the theoretical model and performed analytical calculations, N.S.P., I.A.N. and I.R.S. performed numerical DFT calculations. K.S.P. and E.M., grew and characterized the bulk crystals, V.M.P., A.V.S., and O.A.S. planned and designed the experiments, analyzed and processed the data. A.V.S. and O.A.S. performed magnetization and magnetotransport measurements with bulk samples. E.M. prepared the flake samples, N.P., E.M. and L.V. peformed measurements with flakes and processed their results. P.D.G. and V.M.P. wrote the paper with considerable help from all authors. All the authors contributed to the discussion of the experimental results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Lingling Tao and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grigoriev, P.D., Pavlov, N.S., Nekrasov, I.A. et al. Universal negative magnetoresistance in antiferromagnetic metals from symmetry breaking of electron wave functions. Commun Mater 6, 252 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00970-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00970-5