Abstract

Radiochromic crystals have many suitable features for dosimetry across a broad range of radiotherapy modalities, yet the study of these materials within the medical physics community has been limited. Here, we study three types of radiochromic pentacosa-10,12-diynoic acid-based formulations: two analogues of commercially available materials and one newly developed. Formulations coated on polyethylene are irradiated with photon (6 and 10 MV) and proton (74 MeV) beams (0–25 Gy) using custom fibre-optic setups that enable real-time transmission measurements at 1.5–2 cm depth to maintain dosimetric accuracy. The dose response to ionizing radiation is compared between the formulations and all formulations were characterized using a variety of analytical methods. The response of radiochromic crystals to ionizing radiation is complex and influenced by factors such as monomer composition and resulting macroscopic crystal morphology. By optimizing these parameters, it could be possible to develop dosimeters suitable for a variety of clinical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The measurement of absorbed dose is a necessary component in many fundamental investigations that explore the effects of ionizing radiation on living organisms1,2. In the medical field, radiation dosimetry is a critical aspect of clinical radiotherapy, encompassing the calibration and characterization of radioactive isotopes, as well as high-energy beams from linear accelerators and cyclotrons. Given the increasingly sophisticated treatments developed over the last few decades, such as magnetic resonance (MR)-guided radiotherapy, brachytherapy, intensity modulated radiotherapy, volumetric modulated arc therapy, and heavy-ion therapies using proton, helium, and carbon ion beams, patient-specific in vivo dosimetry has become of great importance3. While cumulative dose measurements provide some degree of confirmation of quality assurance, some errors can only be exposed through real-time dose monitoring4. Dose measurements by proxy, such as those with Electronic Portal Imaging Detector (EPID), can offer real-time information within a treatment field5, but not outside, where dose to organs at risk is also of interest. Therefore, logistically placed single- or multi-point dosimeters providing real-time measurements on the patient can ensure high-quality radiotherapy treatments by also acting as a safety tool for interruption in cases of gross deviations from expected dose.

Real-time dosimeters, with effective atomic composition of water, that are small and do not attenuate dose, are ideal for most applications across a broad range of radiotherapy techniques6, including brachytherapy7,8 and proton therapy9. Previously, dosimeters have been investigated for both photon and proton beams10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Organic radiochromic crystals are the active material in commercial radiochromic films and are used suspended in an organic binder (taken together as a formulation). The radiochromic films have many suitable features, such as high spatial resolution18,19, near tissue equivalence resulting in low energy dependence20, and have shown promise for real-time dosimetry using fibre-optic read-out6,21,22. The historical Gafchromic™ HD-810 and MD-55 and more recent EBT-3 and EBT-XD films have been used to evaluate the dose delivered in photon and proton beams10,20,23,24,25,26, and have been demonstrated to be robust under FLASH conditions, an attractive emerging technique that delivers an ultra-high dose of radiation to a tumor in an extremely short period of time27.

The study of these materials within the medical physics community, however, has been restricted by the availability of commercial products, with limited exploration of fundamental effects of chemistry on dosimetry28,29. To investigate how various chemical and structural characteristics affect dosimetric properties of these formulations, such that a dosimeter can be tailored and optimized to its clinical application, physicists must be able to generate and study them without reliance on commercial vendors.

The radiation-sensitive component in these radiochromic materials is self-assembled crystals of di-substituted diacetylene monomers with two side groups (R1 and R2), such as pentacosa-10,12-diynoic acid (PCDA) or its Li+ salt version, lithium pentacosa-10,12-diynoate (LiPCDA), used in commercial products6,20,25,30. The side groups of the diacetylenes (R1 and R2) affect the three-dimensional packing of monomers within diacetylene crystals22,31,32. If the diacetylene monomers are less than 4 Å apart, exposure to heat or ionizing radiation will induce a topotactic solid-state polymerization33. This is a solid-state 1,4-addition polymerization that follows the topochemical postulates: (I) the distance between neighboring reactive centers (C1–C4′) is less than 3.8 Å, (II) the monomers are oriented coplanar and parallel, (III) the repeat unit spacing is approximately 4.9 Å, (IV) the polymer grows within the monomer matrix, (V) polymerization proceeds with minimal atomic displacement (the “least motion principle”), (VI) the angle between the long axis of the diacetylene moiety and the stacking axis is ideally ~45°, and (VII) the side groups (R₁ and R₂) should not hinder monomer packing34. The result is a polymer with a conjugated backbone held within a monomer crystal matrix. The size of the polymer is often slightly different than the equivalent length of the monomers within the crystal. In the case of PCDA, the resultant polymer is shorter than the length of the same number of repeat units, and as the polymer grows, the addition of subsequent monomers slows down due to an increase in physical separation between the end reactive center of the polymer and the next available monomer6. Although PCDA in Gafchromic™ MD-55 film almost completely polymerizes within 4 ms after a 2.5 MeV electron pulse of 13 Gy (2.5 μs)35, this decrease in speed of polymer growth nonetheless results in an asymptotic increase in optical density (ΔOD) after the end of irradiation6,20,21,25,36,37. The molecular π-orbital electrons of the polymer backbone absorb visible light38, resulting in a distinct polymer-within-monomer-matrix absorbance spectrum39,40. The corresponding increase in ΔOD is correlated to the absorbed dose through a calibration curve. The choice of R1 and R2 affect not only optical characteristics of the resulting polymer41, such as the position of the main absorbance peak (λmax) in the spectrum41,42, and the shift of λmax with absorbed radiation dose43, as well as potential sensitivity to ionizing radiation dose and post-irradiation darkening21,44. These properties contribute to the overall dose response and affect the potential clinical use of any given diacetylene. For example, significant post-irradiation darkening can introduce errors into real-time measurements when the dose-rate deviates from the one used to generate the calibration curve45. Non-linear response with dose introduces a need to keep a record of total dose-to-date, instead of a single calibration factor, if the dosimeter is to be used more than once. This adds unnecessary complexity to clinical implementation. Selecting a diacetylene that meets desired clinical objectives requires an understanding of the underlying behavior of these radiochromic materials.

Studying fundamental characteristics of these diacetylenes by using commercial films can be challenging, as the manufacturer’s exact formulation, including stabilizing agents and other additives, is not disclosed and may change over time. For example, potential variation in lot-to-lot elemental composition has been shown to affect energy dependence44. In studying relative sensitivity between different commercial diacetylenes, absolute comparisons are challenging as the percent solid mass of sensitive material is not disclosed. End users aiming to understand these diacetylene materials also have no control over binding agents, adhesives, stabilizers, impurities, or substrates, which can all affect measured optical properties and their potential clinical utitlity42,43. Therefore, we aim to generate controlled radiochromic formulations and better understand how these dosimetric materials behave across broad clinical radiotherapy scenarios. Ultimately, we aim to formulate and clinically implement simple and cost-effective real-time optical dosimeters tunable to any application.

LiPCDA has been shown to exist in two crystalline forms: a monohydrated form used in the commercial EBT-3 films and an anhydrous form46. In our previous work, we produced the anhydrous form by desiccating commercial EBT-3 film, with the resulting film having a λmax at ~674 nm and being ~3× less sensitive to 6 MV photons37. Aside from using a commercial product that one has no control over and being cumbersome to manufacture through desiccation, this anhydrous form of EBT-3 does not meet the desired linearity in response to absorbed dose37.

In this study, we formulated three distinct PCDA-based materials and evaluated their real-time dose response using a newly developed fibre-optic measurement device. The two Li+ containing materials, 635LiPCDA and 674LiPCDA named according to their λmax positions, showed greater apparent sensitivity (change in ΔOD per ionizing radiation dose) compared to PCDA that had no Li+ ions. Spectroscopic and morphological characterizations showed that 635LiPCDA and PCDA formulations closely resemble the active materials in commercial EBT-3 and MD-55 radiochromic films. Furthermore, elemental analysis (EA) and solid-state carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance (13C NMR) confirmed that our 635LiPCDA matches the LiPCDA material used in commercial products, demonstrating our ability to fabricate an analog of an existing dosimeter. Integration of water into the 635LiPCDA crystal, as confirmed through EA and Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy, resulted in a greater apparent sensitivity to ionizing radiation dose compared to the 674LiPCDA. Interestingly, despite our newly developed 674LiPCDA having the same Li:PCDA ratio as the monohydrate version, it exhibited plate-like morphology similar to PCDA, where both plate-like morphologies do not contain water. The apparent sensitivity of radiochromic formulations to ionizing radiation from high-energy proton and photon beams is a complex relationship between the chemical structure of monomers, integration of small molecules into the crystal, and crystal morphology.

Results

Macroscopic morphology and absorbance spectra of radiochromic formulations

The normalized spectra of the LiPCDA formulations with varying stoichiometric ratios of Li+ to PCDA are shown in Fig. 1 (chemical structures described in the following formulations are shown in S1). Two distinct main peaks (λmax) were observed for the Li+ varied series. LiPCDA formulations with ratios <0.6:1 exhibited a main absorbance peak at ~635 nm, whereas ratios >0.7:1 had λmax at ~674 nm. The scanning electron microscope images in Fig. 2a, b show distinct differences in crystal morphology at the stoichiometric ratio limits of the Li+: PCDA (0.2:1 and 1:1), where Li+ was present. The crystals formed from 0.2:1 formulation resembled a ribbon or “hair-like” morphology, whilst the crystals from the 1:1 formulation were flake or “plate-like” in appearance. Despite the inclusion of Li+, the 1:1 LiPCDA crystals (Fig. 2b) exhibited similar crystal morphology to PCDA (Fig. 2d), which does not contain any Li+. A combination of peaks was observed in the 0.6:1 and 0.7:1 formulations, with 0.6:1 having λmax at ~635 nm and a new notable peak at ~674 nm. Similarly, the 0.7:1 had λmax at ~674 nm and a weaker peak at ~635 nm. Figure 2c depicts the electron micrograph of the 0.6:1 formulation, indicative of both crystal morphologies. To compare the dose sensitivity between the distinct crystal forms, only PCDA, 0.2:1, and 1:1 molar ratio formulations of LiPCDA were further studied. We labeled the 0.2:1 and 1:1 LiPCDA as 635LiPCDA and 674LiPCDA, respectively, based on the exhibition of their λmax positions.

Real-time response to absorbed dose from proton and photon beams

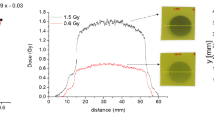

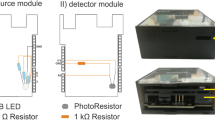

Real-time dose response was assessed with custom film fabrications using the three formulations (see Figs. S2 and S3) and two custom-designed phantoms and instrumentation (Figs. 3 and 4) tailored for photon and proton irradiation. Each phantom was equipped with integrated optical fibres to enable transmission-mode spectroscopy measurements. For proton beam, the jig aligned the 2D surface of the sample film with the proton beam front and accommodated multiple blocks of Solid WaterTM, a plastic of water-equivalent electron density intended for use in megavoltage photon and proton beams47,48,49, to adjust the penetration depth of the beam such that the film was at the position of the Spread-Out Bragg Peak (See Supplementary Methods 2 for further details). For photon experiments, the film was positioned at the depth of maximum dose for each beam energy.

Schematic diagram of the proton irradiation apparatus (a), including: (A) proton beam, (B) beam profile monitor, (C) collimator #1/scatterer, (D) range modulator wheel, (E) collimator #2, (F) beam monitor ion chamber, (G) beam nozzle and collimator #3, (H) Solid WaterTM phantom, (I) real-time irradiation jig for proton beam. CAD drawing of new custom real-time irradiation jig (b) and top view schematic drawing of light interaction with sample (c). Labels 1 and 2 refer to the delivery and detection fibres, respectively.

Schematic diagram of the photon irradiation apparatus (a) including: (A) electron gun, (B) accelerating wave guide, (C) bending magnet, (D) target, (E) photon beam, (F) Solid WaterTM phantom. CAD drawing of custom real-time irradiation phantom (b) and schematic drawing of light interaction with sample (c). Labels 1 and 2 refer to the delivery and detection fibres, respectively.

Using the above configuration, the fibres were connected to a light source and a charge-couple device spectrophotometer. The change in absorbance (∆A) at each wavelength (λ) and the change in ∆OD over a spectral range were calculated using Eqs. 1 and 2, respectively6:

where \({I\left(\lambda \right)}_{{{{\rm{ref}}}}}\) represents the intensity of the light source at a wavelength \(\lambda\) of unirradiated film collected before the irradiation beam was turned on, \({I(\lambda )}_{{{{\rm{dark}}}}}\) is the dark intensity due to stray light collected by spectrophotometer when the light source is turned off, and \({I\left(\lambda \right)}_{{{{\rm{data}}}}}\) is the transmitted light intensity collected before, during and after beam exposure. The n parameter represents the number of spectral bins needed to cover the wavelength range. The ∆OD was calculated by integrating the absorbance spectra over 10 nm around the main absorbance peak.

Representative examples of the ΔOD determined as a function of time are shown in Fig. 5. The three Li+ varied samples were irradiated to a total absorbed dose of 2000 cGy, with the dose rates matched between 10 MV photon and 74 MeV proton beams. The data shows the ΔOD increasing rapidly during irradiation, followed by a notable change in slope when the irradiation is completed and beam is turned off, as expected6,37. See Supplementary Fig. 4 for the data collection and processing schematic.

Change in OD vs time for a single, representative sample of 635LiCPDA, 674LiPCDA and PCDA when exposed to a 10 MV photon (solid line) and a 74 MeV proton (dashed lined) beams. Dose rates for the 635LiPCDA photon and proton exposure were 12 Gy min−1, whereas the dose rates for the 674LiPCDA and PCDA were 20 Gy min−1.

To account for variability in active material thickness between samples, the ∆OD for each sample was either divided by the average coating thickness (\({ < \!T}_{s}\! > \)) or normalized to the average thickness across all replicate samples for the same formulation \({ < \!T}_{{{\mathrm{all}}}}\! > \), as shown in Eq. 3:

The thickness normalized dose response curves of each formulation irradiated with a photon and proton beam are shown in Figs. 6 and 7. The error bars are one standard deviation for N = 3 and N = 5 independent measurements for the proton and photon experiments, respectively. Unexpectedly, there was a lack of PCDA response at 100 cGy for both photon and proton experiments. This was in part due to lower apparent sensitivity of PCDA based films compared to LiPCDA based films21,50, due to the PCDA crystal forming near the limits of being photoreactive51 as per the topochemical postulate described in the Introduction. It may also be because we achieved a lower fraction of solid active material (crystals) in our formulations compared to commercial analogs, as later demonstrated with the 635LiPCDA comparison to EBT-3 films. The comparatively large error bars observed in the samples irradiated with the photon beam are attributed to the variability in deposition of formulations on the substrate. Since for photon measurements a smaller optical spot size (~3.4 mm) on the film sample was used, this resulted in less area on the sample being averaged for every measurement compared to the proton measurements (~17.5 mm). (see Supplementary Fig. 5).

Dose response curves of 635LiPCDA and PCDA formulations, thicknesses normalized for each film (37 μm, and 50 μm, respectively). 635LiPCDA is fit to non-linear function and PCDA is fit to a linear function to match known fit functions of its commercial analogs. The dose rate used for photon (solid line) and proton (dashed line) irradiation was 20 Gy min−1 and 12 Gy min−1 for PCDA and 635LiPCDA, respectively. Error bars represent the 1σ (one standard deviation) between samples.

Thickness-normalized (to 16 µm) ΔOD vs absorbed dose of 674LiPCDA formulation irradiated with a 10 MV photon (solid line) and a 74 MeV proton (dashed line) beams at a dose rate of 20 Gy min−1. ΔOD curves are fitted to a non-linear function (a) and a linear function (b) with residuals shown at the bottom. Error bars represent the 1σ standard deviation between samples.

Figure 6 shows the dose response of 635LiPCDA and PCDA. The thickness-normalized dose response curves of 635LiPCDA were fit to a non-linear function (see Supplementary Eqs. 4 and 5 of the Supplementary Methods 2) which has been previously used to describe its commercial analog EBT-352. The 635LiPCDA fits yielded R2 = 0.9995 and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) = 0.03 for photon dose response, and R2 = 0.9990 and RMSE = 0.0152 for the proton dose response. PCDA, analogous to commercial Gafchromic™ MD-55, has been shown to have a linear relationship of ΔOD with absorbed dose and was therefore fit to a linear function6,53.

The newly developed LiPCDA (674LiPCDA) has no commercial analog and has not been previously reported in literature, to the best of our knowledge. Therefore, to investigate its linearity, the thickness-normalized dose response curves were fit to both the linear and non-linear functions (Fig. 7), with the residuals shown. The residuals of the linear fit show an underlying function which is not accounted for in the linear fit, with R2 = 0.9909 and RMSE = 0.0067 for proton response and R2 = 0.9893 and RMSE = 0.0093 for photons. On the other hand, when a non-linear fit was applied, it resulted in an R2 = 0.9949 and RMSE = 0.0050 for proton response. Similarly, an R2 = 0.9995 with RMSE = 0.0020 for photon response is observed, with no clear underlying functions in the residuals. These results indicate that the dose response of the new 674LiPCDA formulation is not linear, resembling the response curves of 635LiPCDA. The ΔOD as a function of absorbed dose for all formulations was higher for photon beams relative to proton beams in all cases.

Figure 8 shows a comparison between the apparent sensitivity of each formulation, irradiated with a 6 MV photon beam at a clinical dose rate (300 cGy min−1, N = 5). The apparent sensitivity of 635LiPCDA was the greatest, followed by the 674LiPCDA and lastly the PCDA. When compared to 635LiPCDA, on average, 674LiPCDA was 68 ± 2% less sensitive at 25 Gy. The same calculation showed that PCDA was on average 93 ± 1% less sensitive, relative to 635LiPCDA.

Thickness corrected ∆OD vs dose plots of PCDA (dotted line), 635 LiPCDA (solid line), and 674LiPCDA (dashed line) irradiated with a 6 MV 10 cm × 10 cm photon beam at a dose rate of 300 cGy min−1 at 1.5 cm depth and 100 cm source-to-axis distance (See Supplementary Methods 2). Error bars represent the 1σ standard deviation between samples.

Comparison of generated materials to commercial radiochromic films

Figure 9 shows the absorbance spectra (normalized to 1.0) of 635LiPCDA, 674LiPCDA, PCDA, and commercial EBT-3 after irradiation with a 6 MV photon beam at a total absorbed dose of 500 cGy. The 674LiPCDA formulation, despite having a lithium ion, had a peak absorbance at ~674 nm, similar to the commercial Gafchromic™ MD-55, which was composed of PCDA54,55. Whereas 635LiCPDA and commercial EBT-3 were observed to have a comparable absorbance spectra and λmax positions, the 5 nm red-shift observed in 635LiPCDA relative to EBT-3 may be due to the difference from binder and stabilizers used in the commercial forms.

Absorbance spectra (normalized to 1) of 635LiPCDA (red dashed line), 674LiCPDA (green dashed line), PCDA (blue dashed line) and commercial EBT-3 film (black solid line) after irradiation with a 6 MV photon beam to a total absorbed dose of 500 cGy at a dose rate of 300 cGy min−1, at 1.5 cm depth and 100 cm source-to-axis distance (See Supplementary Methods 2).

Figure 10 depicts ∆OD as a function of absorbed dose for commercial EBT-3 and 635LiPCDA films, irradiated with a 6 MV beam at 300 cGy min−1. The left plot shows ∆OD µm−1 and the right shows the average ∆OD with no thickness correction applied. Error bars of the 635LiPCDA formulations are larger due to a higher degree of film non-uniformity in fabrication relative to the commercial EBT-3.

a ∆OD per micron vs absorbed dose of 635LiPCDA (dashed line) and EBT-3 films (solid line). b ∆OD vs absorbed dose of 100 μm thick 635LiPCDA (dashed line) and EBT-3 films (solid line). Error bars represent the 1σ standard deviation between samples (N = 5); (EBT-3 error bars are too small to be visualized).

Characterization of water-borne crystals

Crystals of each formulation (635LiPCDA, 674LiPCDA, and PCDA) were synthesized in water without gelatin and isolated (for further details see Supplementary Method 3). Standard Normal Variate normalized56 Raman spectra of unirradiated and those irradiated for 1 h with 254 nm UV light are shown in Fig. 11. All samples, both with and without UV exposure had a prominent C≡C peak occurring between 2060 cm−1 and 2092 cm−1 and a C=C peak occurring near 1500 cm−1, as expected from polymerized diacetylenes57. Only unexposed PCDA had a detectable signal at 2256 cm−1 consistent with the vibrational frequency of the C≡C in the dialkyne monomers of the PCDA crystals. Upon UV irradiation, all samples exhibited a redshift in the C≡C stretching region (2060–2100 cm−1), consistent with topochemical polymerization of the diacetylenes previously reported57,58. This redshift was most pronounced in the 635LiPCDA crystals. In the UV-exposed 674LiPCDA sample, Raman spectra exhibited a primary peak alongside the emergence of a secondary partially overlapping peak near 2100 cm−1.

Stacked Raman spectra of PCDA (blue line), 635 nm absorbing (red line), and 674 nm absorbing (black line) LiPCDA crystals without UV exposure (solid lines) and crystal samples after 1-h irradiation (dotted lines) with 254 nm UV light, collected using a 785 nm excitation laser. All spectra are normalized and offset vertically for clarity.

Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectra of PCDA, 635LiPCDA, and 674LiPCDA are shown in Fig. 12. The spectrum of PCDA exhibits a broad absorption band between 2450 and 3300 cm−1, attributed to the O–H stretching vibration of the carboxylic acid group. The strong signal at 1691 cm−1 corresponds to the C=O stretch of the carboxylic acid in its hydrogen-bonded, dimeric form and agrees with literature51. Both LiPCDA crystals display characteristic carboxylate bands, with asymmetric stretching near 1569 cm−1 and symmetric stretching in the 1441–1451 cm−1 range. The FTIR spectrum of 635LiPCDA shows a broad O–H stretching band between 3040 and 3510 cm−1, suggesting the presence of water in a lithium–carboxylate complex. This feature is absent in the spectrum of 674LiPCDA.

To further verify the extent of lithium incorporation in the crystal, EA of the water-borne crystals was performed. For PCDA crystals (C₂₅H₄₂O₂), the calculated elemental composition for carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen was 80.16%, 11.30%, and 8.54%, respectively. The experimentally determined values were C, 79.95%; H, 10.99%; O, 8.46%, with nitrogen below the detection threshold (<0.50%), indicating limited presence of starting material. For 635LiPCDA, a hydrated lithium salt formulation (C₂₅H₄₁O₂ Li•H₂O), the calculated composition was C, 75.34%; H, 10.88%; O, 12.04%; Li, 1.74%. The measured values were C, 75.59%; H, 10.81%; Li, 1.66%, with N < 0.50%, confirming the monohydrate form. Lastly, for 674LiPCDA, based on the anhydrous formulation (C₂₅H₄₁O₂Li), the calculated composition was C, 78.91%; H, 10.86%; O, 8.41%; Li, 1.82%. The experimental values were C, 78.00%; H, 10.86%; Li, 1.69%; N < 0.50%. These results confirm the successful incorporation of lithium into the PCDA backbone and align closely with the proposed molecular formulations and previously reported compositions46. EA of oxygen was not completed for lithium-containing crystals due to detection limitations and interference. Nitrogen analysis was conducted to evaluate the possible incorporation of tetraethylammonium salt within the PCDA-based crystals.

Due to limited solubility, LiPCDA crystals were characterized by cross-polarization total suppression of sidebands (CP-TOSS) solid-state 13C NMR. The assigned 13C NMR spectra of PCDA, 635LiPCDA, and 674LiPCDA crystals before and after UV exposure are stacked in Fig. 13. To determine the spinning sidebands, spectra were collected while the sample spun at 7 and 8 kHz. Signals that shifted with different spin rates or were anti-phase were identified as spinning sidebands. These were observed at 66, 106, 119, 158 ppm, marked with asterisks.

Stacked CP-TOSS solid-state 13C NMR spectra of waterborne PCDA (blue line), 635LiPCDA (red line), and 674LiPCDA (black line) crystals obtained before (darker line) and after UV exposure (lighter line). Peak assignment corresponds to the numbered carbon atoms of the PCDA-based monomer and polymer structures shown at the top of the figure. Asterisks (*) indicate spinning sidebands resulting from sample rotation during spinning.

For all three crystals, distinctive signals corresponding to the alkyne carbon atoms of the crystal monomers are observed at 65 and 80 ppm. After UV exposure, the appearance of a broad signal at 107 and 131 ppm corresponding to alkene carbon atoms indicate the presence of polymerized crystals. Alkyne signals remain present in the spectra, indicating residual, unreacted PCDA-based monomer. The carbonyl signal can also be observed in the 185–190 ppm range, with PCDA and the 674LiPCDA crystal exhibiting a single signal at 183 and 187 ppm, respectively, while the 635LiPCDA possesses multiple signals between 182 and 189 ppm.

Discussion

The response to ionizing radiation for diacetylenes, specifically PCDA, is complex and dependent on many factors such as monomer composition, macroscopic crystal morphology, and spectral characteristics. It has been shown by powder X-ray diffraction that PCDA forms a crystal with a repeat unit spacing of 4.5 Å, C1–C4’ distance of 3.7 Å, and a tilt angle of 44.7° 51 Addition of Li+ has been demonstrated to alter the packing parameters46. Hall et al. hypothesized that the Li+ in LiPCDA has a combination of chelating and bridging bidentate coordination to the carboxylate groups of adjacent diacetylene monomer side chains, which cause interaction between adjacent monomer side groups and alters the packing of the monomers46. This affects the apparent sensitivity of the PCDA crystals containing Li+ salt.

Although we demonstrate in this manuscript that the addition of Li+ ion to PCDA generally improves the apparent sensitivity by up to ~93%, the resulting absorbance spectrum of the polymer depends strongly on the initial stoichiometry of Li+ to PCDA. Addition of Li+ was initially thought to generate longer crystals (with >10:1 aspect ratio) and believed to be linked to improved ionizing radiation sensitivity21, compared to small rhomboidal crystals (<2:1 aspect ratio) without added Li+. However, it appears that the improvement in apparent sensitivity from rhomboidal LiPCDA to the longer crystals was due to the integration of other small molecules into the crystal (in this particular case, H2O)37,55 and not the Li+ or the size of the crystal itself, as demonstrated previously through the removal of H2O from the crystal37. Furthermore, removal of H2O altered the spectral peak positions without affecting the macroscopic crystal morphology as visualized on scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Therefore, we show that the spectra and dose response cannot be directly linked to the macroscopic presentation of the crystalline form.

Here, we showed that the absorbance spectra of all formulations with varying initial stoichiometric ratios of Li+: PCDA (0:1 to 1:1) produced only two distinct λmax positions, at ~635 nm and at ~674 nm. This suggests that the backbone of the polymer chains, which are responsible for the color change and increase in OD41,55,59 can only exist in the two orientations that allow electronic transitions, which form these two main absorbance peaks. At lower feed molar ratios (0.2:1), the LiPCDA crystals formed into 635LiPCDA, which is spectrally resembling of EBT-3, whereas in our newly developed formulation at high feed molar ratios (1:1), the LiPCDA was formed with the spectral peak at ~674 nm, similar to the case where there is no Li+ present (PCDA). At several intermediate initial stoichiometric ratios, both peaks and macroscopic crystal morphologies (as observed through SEM) were present. The interpretation of these intermediate states is somewhat challenging spectroscopically, as both crystals of 1:1 LiPCDA and PCDA with no Li+ ion have a peak maximum at 674 nm. Also, although the 0.6:1 formulation had a relatively higher 635 nm absorbance peak compared to that at 674 nm, conclusions about the relative proportion of the crystals formed cannot be made as the extinction coefficients for the polymers formed within these crystals are unknown. Further investigations are needed to differentiate between the two 674 nm absorbing crystals and to determine the extinction coefficient of all crystal forms.

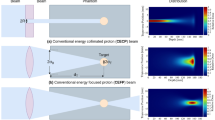

Based on a newly developed fibre-optic measurement technique and device, we have demonstrated real-time transmission measurements of radiochromic films while exposed to ionizing radiation from a high-energy proton beam. Although time-resolved measurements for proton beams have been performed by others60,61, similar to our previous work for real-time photon measurements6,21,37, the real-time approach described herein provides an opportunity for transmission measurements in a setup allowing for accurate dosimetry at depth, which is relevant to radiotherapy treatments.

As expected, the real-time dose response of the three formulations, 635LiCPDA, 674LiPCDA, and PCDA, showed the same trend in apparent sensitivity (635LiPCDA then 674LiPCDA and lastly PCDA) relative to each other as observed for photon-irradiated films. The dose response of 635LiPCDA and PCDA followed expected behavior and could be modeled by thickness-normalized functions that were also used to describe their commercial analogs, EBT-3 and MD-55, respectively. The dose response of 674LiPCDA was observed to be ~3.5 times higher compared to the original diacetylene, PCDA. Despite many similarities to the PCDA, the response to the dose of our newly developed 674LiPCDA could not be accurately modeled by a simple linear function and was better described by the non-linear model. This result indicates that 674LiPCDA, which has peak absorbance at 674 nm, does not have a linear response to dose, like that of 635LiPCDA.

Comparing photon and proton beams, the real-time response to radiation from the proton beam of all crystalline materials generated in this study showed lower sensitivity relative to the same dose from the photon beam. This is attributed to the quenching effect that was similarly observed for other radiochromic films such as EBT-362,63,64. It has been previously reported that when exposed to charged particle beams such as protons, EBT-3 under responds in terms of sensitivity by up to 26% relative to a standard ion chamber measurement65. This effect is hypothesized to be due to: (a) the higher probability of free radicals formed through high LET beams recombining without polymer initiation, and/or (b) saturation of ionization sites along the track of the charged particle, without allowing full polymers to form63. Of course, it is possible that the under response is a factor of both of these effects. A direct comparison of our results here to the literature is not possible due to the differences in beam energies, beam spectra, and filter effects.

The active component in our compositions was only composed of LiPCDA at various Li+ to PCDA feed molar ratios and, importantly, with no other materials or additives that are present in commercial films66. Consequently, this allowed for direct comparisons of dose sensitivity between different formulations, after accounting for coating thickness. However, the scope of dose characterization in this study was limited. For example, properties such as energy dependence, known to be influenced by radiochromic film composition44 and dose rate dependence, were not evaluated and remain the subject of future work. Notably, radiochromic films have been shown to exhibit dose rate dependence under real-time measurement conditions45, which may also apply to the formulations presented here. Investigation of these effects is the focus of future work.

To further investigate how the lithium stoichiometry influences the PCDA dose response, PCDA-based crystals (635LiPCDA, 674LiPCDA, and PCDA) were synthesized in water without gelatin. Every sample had a distinct C≡C peak occurring between 2060 cm−1 and 2092 cm−1 in the Raman spectra, indicating the presence of the polymers within the crystals even prior to irradiation with UV light. With the exception of unexposed PCDA having a small but detectable signal at 2256 cm−1, indicative of the C≡C bonds within diacetylene monomers, this signal was otherwise not detected. Upon UV irradiation, all samples exhibited a redshift in the C≡C stretching region (2060–2100 cm−1), consistent with topochemical polymerization of the diacetylene58, and was most pronounced in the 635LiPCDA crystals, which have been previously attributed to a more planar polydiacetylene structure53. In the UV-exposed 674LiPCDA sample, a secondary partially overlapping peak near 2100 cm−1 had emerged. This dual-band structure suggests the formation of coexisting polymeric domains with differing degrees of conjugation or local packing environments, potentially influenced by the Li+ coordination. Wang et al.67 described a similar effect when PCDA was annealed with other cations. Complementary ATR-FTIR analysis of both LiPCDA complexes display characteristic carboxylate bands, with asymmetric stretching near 1569 cm−1 and symmetric stretching in the 1441–1451 cm−1 range. The separation between these two bands (Δν = 122–126 cm−1) indicate the coordination of the carboxylate group with lithium, consistent with bidentate complexation46,68,69. The broad O–H stretching band observed in the FTIR spectrum of 635LiPCDA indicates the presence of water, suggesting that the crystals exist in a hydrated form. EA further supports this, confirming that 635LiPCDA is a monohydrate. The incorporation of lithium into the LiPCDA crystal structure is also verified by EA. Despite being synthesized using different initial Li+:PCDA molar ratios (0.2:1 for 635LiPCDA and 1:1 for 674LiPCDA), both formulations incorporated nearly identical amounts of lithium (1.66% and 1.69% for 635LiPCDA and 674LiPCDA, respectively). This convergence implies the presence of a coordination threshold or saturation point within the crystal lattice, beyond which additional lithium ions are not incorporated into the molecular structure. It is likely that only a finite number of coordination sites, such as the deprotonated carboxylate groups, are available to bind Li+, and that once these are occupied, excess lithium remains unincorporated or is removed during crystal isolation. This suggests that lithium incorporation is dictated more by how lithium is coordinating to the carboxylate rather than by the stoichiometry of the synthesis solution.

The 13C NMR spectra of PCDA are similar to previously reported51, but with higher signal resulting from polymer at 107 and 131 ppm. The dependence of LiPCDA sensitivity on crystal packing is further supported by the number of carbonyl signals observed in the 13C NMR spectra of LiPCDA crystals. For monohydrate 635LiPCDA, multiple carbonyl signals are observed, consistent with literature46. This suggests that the 635LiPCDA crystal may adopt more than one arrangement within the crystal packing structure. Further investigation into the crystal packing structure by X-ray crystallography can provide additional insight into structure-reactivity behavior.

Conclusion

We have generated three different crystalline materials from formulations of varying Li+ composition and measured their real-time dose response to enable exploration of fundamental effects of chemistry on real-time dosimetry. Our Li+ series study showed that the dominant spectral peaks positions (λmax) are binary, with peaks occurring at either ~635 nm or ~674 nm.

UV-VIS absorbance spectra, as well as other characterizations, demonstrated that the crystals from our 635LiPCDA and PCDA formulations were similar to those from the existing commercial EBT-3 and MD-55 films, respectively. This underscores our ability to fabricate analogs of active material comparable to those found in commercial radiochromic dosimeters, yet with full control over the formulation.

The newly developed 674LiPCDA formulation exhibits structural and spectral features characteristic of both 635LiPCDA and PCDA. Although it shares the same Li+:PCDA ratio as 635LiPCDA, as confirmed by EA, ATR-FTIR indicates that no water is present in 674LiPCDA. The 674LiPCDA formulation exhibited “plate-like” macroscopic morphology (~1:1 aspect ratio) observed in PCDA, rather than the elongated “hair-like” crystal of 635LiPCDA (>100:1 aspect ratio), and exhibited the same UV-VIS absorbance spectra. Despite this, 674LiPCDA exhibited a higher dose response relative to PCDA and was non-linear.

A quenching effect, when irradiated with a proton beam, for all three formulations was observed, consistent with what was reported for commercial radiochromic films. Our newly developed phantom allowed for real-time transmission measurements of the radiochromic formulations with accurate dosimetry at the depth of SOBP in a proton beam.

This study lays the foundational groundwork for future investigations into the effects of diacetylene side groups, macroscopic crystal morphology, and absorption extinction coefficients on dosimetric measurements under a variety of clinical conditions and should facilitate future optimization of radiochromic crystals for any clinical application. This flexible generation of new radiochromic materials by tuning its chemical composition paves the way for exploration and development of broad-use, real-time in vivo dosimeter technologies to improve patient outcomes in radiotherapy.

Methods

Methodology for making radiochromic crystals and formulations is described in Supplementary Method 1 and Supplementary Method 3. SEM was used to characterize the surface morphology of the radiochromic crystals. Samples were mounted onto aluminum SEM stubs using double-sided carbon adhesive tape and imaged under high vacuum conditions using a Quanta 3D scanning electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific™, Waltham, MA, USA) operated at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV. High-resolution micrographs were obtained to assess crystal shape, surface texture, and structural uniformity.

Raman spectroscopy was performed to evaluate the polymerization of the radiochromic crystals. Crystals were placed in a glass-bottom petri dish and covered with a thin cover glass to minimize movement and ensure optimal focal clarity. Spectra were acquired using an inVia confocal Raman microscope (Renishaw™, Mississauga, ON, Canada) equipped with a 785 nm diode laser and a 1200 lines/mm diffraction grating. A 20× objective lens was used to focus the laser onto the sample, and each spectrum was collected with an integration time of 10 s. This setup enabled the detection of characteristic vibrational modes associated with both monomeric and polymerized phases of the diacetylene crystals.

Cross-polarization total sideband suppression (CP-TOSS) ¹³C solid-state NMR spectra were acquired on a 700 MHz Agilent DD2 spectrometer equipped with a 3.2 mm T3 NB HXY BioMAS solids probe, operating at a spin rate of 7 kHz. Data acquisition parameters included a relaxation delay of 7 s and 10,714 FID accumulations, with a spectral width of –29 to 310 ppm. Spinning sidebands were identified by collecting a spectrum at an increased spin rate of 8 kHz. UV–Vis absorbance spectra were recorded using a Varian Cary 50 Bio UV–Vis spectrophotometer. ATR-FTIR spectra were acquired using a PerkinElmer Spectrum Two FT-IR spectrometer.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

References

Claridge Mackonis, E., Hammond, L., Esteves, A. I. S. & Suchowerska, N. Radiation dosimetry in cell biology: comparison of calculated and measured absorbed dose for a range of culture vessels and clinical beam qualities. Int J. Radiat. Biol. 94, 150–156 (2018).

Claridge Mackonis, E., Suchowerska, N., Naseri, P. & McKenzie, D. R. Optimisation of exposure conditions for in vitro radiobiology experiments. Australas. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 35, 151–157 (2012).

Development of Procedures for In Vivo Dosimetry in Radiotherapy. INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY. https://www.iaea.org/publications/8962/development-of-procedures-for-in-vivo-dosimetry-in-radiotherapy (2013).

Andersen, C. E., Nielsen, S. K., Lindegaard, J. C. & Tanderup, K. Time-resolved in vivo luminescence dosimetry for online error detection in pulsed dose-rate brachytherapy. Med. Phys. 36, 5033–5043 (2009).

Dogan, N. et al. AAPM task group report 307: use of EPIDs for patient-specific IMRT and VMAT QA. Med. Phys. 50, e865–e903 (2023).

Rink, A., Vitkin, I. A. & Jaffray, D. A. Suitability of radiochromic medium for real-time optical measurements of ionizing radiation dose. Med. Phys. 32, 1140–1155 (2005).

Tanderup K., Beddar S., Andersen C. E., Kertzscher G., Cygler J. E. In vivo dosimetry in brachytherapy. Med. Phys. 40, https://doi.org/10.1118/1.4810943 (2013).

Tho D., Lavallée M. C., Beaulieu L. A scintillation dosimeter with real-time positional tracking information for in vivo dosimetry error detection in HDR brachytherapy. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 24, e14150 (2023).

Penner C. et al. A multi-point optical fibre sensor for proton therapy. Electronics 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13061118 (2024).

Esplen, N. et al. Dosimetric characterization of a novel UHDR megavoltage X-ray source for FLASH radiobiological experiments. Sci. Rep. 14, 822 (2024).

Ashraf M. R. et al. Dosimetry for FLASH radiotherapy: a review of tools and the role of radioluminescence and Cherenkov emission. Front. Phys. 8, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2020.00328 (2020).

Penner C. et al. Organic scintillator-fibre sensors for proton therapy dosimetry: SCSF-3HF and EJ-260. Electronics 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12010011 (2023).

Olusoji, O. J. et al. Dosimetric application of phosphorus doped fibre for X-ray and proton therapy. Sensors 21, 5157 (2021).

Lourenço, A. et al. A portable primary-standard level graphite calorimeter for absolute dosimetry in clinical pencil beam scanning proton beams. Phys. Med. Biol. 68, 175005 (2023).

Kim, I. J. et al. Building a graphite calorimetry system for the dosimetry of therapeutic X-ray beams. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 49, 810–816 (2017).

Hsing, C. H. et al. MOSFET dose measurements for proton SOBP beam. Phys. Med. 81, 185–190 (2021).

Martínez-García, M. S. et al. Comparative study of MOSFET response to photon and electron beams in reference conditions. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 225, 95–102 (2015).

Miyatake T. et al. Evaluation of the spatial resolution of GafchromicTM HD-V2 radiochromic film characterized by the modulation transfer function. AIP Adv. 13, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0160754 (2023).

Casolaro, P. Radiochromic films for the two-dimensional dose distribution assessment. Appl. Sci. 11, 1–16 (2021).

Niroomand-Rad, A. et al. Report of AAPM task group 235 radiochromic film dosimetry: an update to TG-55. Med. Phys. 47, 5986–6025 (2020).

Rink, A., Vitkin, I. A. & Jaffray, D. A. Characterization and real-time optical measurements of the ionizing radiation dose response for a new radiochromic medium. Med. Phys. 32, 2510–2516 (2005).

Rink A. Jaffray D. A. Fiber optic-based radiochromic dosimetry. In Scintillation Dosimetry. (eds Beddar, S. & Beaulieu, L.) 293–314 (CRC Press, 2016).

Santos, T., Ventura, T. & Lopes, M. C. A review on radiochromic film dosimetry for dose verification in high energy photon beams. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 179, 109217 (2021).

Anderson, S. E., Grams, M. P., Wan Chan Tseung, H., Furutani, K. M. & Beltran, C. J. A linear relationship for the LET-dependence of Gafchromic EBT3 film in spot-scanning proton therapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 64, 055015 (2019).

Niroomand-Rad, A. et al. Radiochromic film dosimetry: recommendations of AAPM radiation therapy committee task group 55. Med. Phys. 25, 2093–2115 (1998).

Darafsheh, A., Zhao, T. & Khan, R. Spectroscopic analysis of irradiated radiochromic EBT-XD films in proton and photon beams. Phys. Med. Biol. 65, 205002 (2020).

Siddique, S., Ruda, H. E. & Chow, J. C. L. FLASH radiotherapy and the use of radiation dosimeters. Cancers 15, 3883 (2023).

Mittal, A., Verma, S., Natanasabapathi, G., Kumar, P. & Verma, A. K. Diacetylene-based colorimetric radiation sensors for the detection and measurement of γ radiation during blood irradiation. ACS Omega 6, 9482–9491 (2021).

Mittal, A., Kumar, M., Gopishankar, N., Kumar, P. & Verma, A. K. Quantification of narrow band UVB radiation doses in phototherapy using diacetylene based film dosimeters. Sci. Rep. 11, 684 (2021).

Williams M., Metcalfe P. Radiochromic film dosimetry and its applications in radiotherapy. AIP Conf. Proc. 1345, 75–99 (2011).

Baughman, R. H. Solid-state polymerization of diacetylenes. J. Appl. Phys. 43, 4362–4370 (1972).

Baughman, R. H. Solid-state synthesis of large polymer single crystals. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Phys. Ed. 12, 1511–1535 (1974).

Guillet J. Polymer Photophysics and Photochemistry: An Introduction to the Study of Photoprocesses in Macromolecules (Cambridge University Press, 1987).

Enkelmann, V. Structural aspects of the topochemical polymerization of diacetylenes. In Proc. Polydiacetylenes. Advances in Polymer Science (ed. Cantow, H. J.) Vol 63 (Springer, Berlin, 1984).

McLaughlin W. L., Al-Sheikhly M., Lewis D. F., Kovács A., Wojnárovits L. Radiochromic solid-state polymerization reaction. In Irradiation of Polymers Vol 620. ACS Symposium Series. 152–166 (American Chemical Society, 1996).

Addo, D. A., Kaufmann, E. E., Tagoe, S. N. & Kyere, A. K. Characterization of GafChromic EBT2 film dose measurements using a tissue-equivalent water phantom for a Theratron® Equinox Cobalt-60 teletherapy machine. PLoS ONE 17, 0271000 (2022).

Kaiyum, R., Schruder, C. W., Mermut, O. & Rink, A. Role of water in the crystal structure of LiPCDA monomer and the radiotherapy dose response of EBT-3 film. Med. Phys. 49, 3470–3480 (2022).

DeKock R. L., Gray H. B. The molecular-orbital theory of electronic structure and the spectroscopic properties of diatomic molecules. In Chemical Structure and Bonding 2nd edn, 183–271 (University Science Books, 1989).

Sixl H. Electronic structures of conjugated polydiacetylene oligomer molecules. In Electronic Properties of Polymers and Related Compounds (eds. Kuzmany H., Mehring M., Roth S.) 240–245 (Springer Berlin, 1985).

Sixl H., Warta R. Excitons and Polarons in Polyconjugated Diacetylene Molecules. In Electronic Properties of Polymers and Related Compounds (eds. Kuzmany H., Mehring M., Roth S.) 246–248 (Springer Berlin, 1985).

Patel, G. N. & Miller, G. G. Structure-property relationships of diacetylenes and their polymers. J. Macromol. Sci. Part B 20, 111–131 (1981).

Bässler H. Photopolymerization of Diacetylenes. In Polydiacetylenes(ed. Cantow H. J.) 1–48 (Springer Berlin, 1984).

Isa, N. M., Baharin, R., Majid, R. A. & Rahman, W. A. W. A. Optical properties of conjugated polymer: review of its change mechanism for ionizing radiation sensor. Polym. Adv. Technol. 28, 1559–1571 (2017).

Lindsay, P., Rink, A., Ruschin, M. & Jaffray, D. Investigation of energy dependence of EBT and EBT-2 Gafchromic film. Med. Phys. 37, 571–576 (2010).

Rink, A., Vitkin, I. A. & Jaffray, D. A. Intra-irradiation changes in the signal of polymer-based dosimeter (GAFCHROMIC EBT) due to dose rate variations. Phys. Med. Biol. 52, N523–N529 (2007).

Hall, A. V. et al. Alkali metal salts of 10,12-pentacosadiynoic acid and their dosimetry applications. Cryst. Growth Des. 21, 2416–2422 (2021).

Gargett, M. A., Briggs, A. R. & Booth, J. T. Water equivalence of a solid phantom material for radiation dosimetry applications. Phys. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 14, 43–47 (2020).

Langen, K. M. et al. QA for helical tomotherapy: report of the AAPM task group 148. Med. Phys. 37, 4817–4853 (2010).

Kim, D. H. et al. Proton range verification in inhomogeneous tissue: treatment planning system vs. measurement vs. Monte Carlo simulation. PLoS ONE 13, 0193904 (2018).

Butson, M. J., Cheung, T. & Yu, P. K. N. Absorption spectra variations of EBT radiochromic film from radiation exposure. Phys. Med. Biol. 50, N135–N140 (2005).

Hall, A. V. et al. The crystal engineering of radiation-sensitive diacetylene cocrystals and salts. Chem. Sci. 11, 8025–8035 (2020).

Sorriaux, J. et al. Evaluation of Gafchromic® EBT3 films characteristics in therapy photon, electron and proton beams. Phys. Med. 29, 599–606 (2013).

Daftari, I., Castenadas, C., Petti, P. L., Singh, R. P. & Verhey, L. J. An application of GafChromic MD-55 film for 67.5 MeV clinical proton beam dosimetry. Phys. Med. Biol. 44, 2735–2745 (1999).

Klassen, N. V., Van Der Zwan, L. & Cygler, J. GafChromic MD-55: investigated as a precision dosimeter. Med Phys. 24, 1924–1934 (1997).

Rink, A., Lewis, D. F., Varma, S., Vitkin, I. A. & Jaffray, D. A. Temperature and hydration effects on absorbance spectra and radiation sensitivity of a radiochromic medium. Med. Phys. 35, 4545–4555 (2008).

Liland, K. H., Kohler, A. & Afseth, N. K. Model-based pre-processing in Raman spectroscopy of biological samples. J. Raman Spectrosc. 47, 643–650 (2016).

Melveger, A. J. & Baughman, R. H. Raman spectral changes during the solid-state polymerization of diacetylenes. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Phys. Ed. 11, 603–619 (1973).

Itoh, K. et al. Raman microspectroscopic study on polymerization and degradation processes of a diacetylene derivative at surface enhanced Raman scattering active substrates. 1. Reaction kinetics. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 264–270 (2005).

Patel, G. N., Chance, R. R. & Witt, J. D. A planar-nonplanar conformational transition in conjugated polymer solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 70, 4387–4392 (1979).

Campajola, L. et al. An innovative real-time dosimeter for radiation hardness assurance tests. Physics 4, 409–420 (2022).

Spruijt, K. H. et al. Development of patient-specific pre-treatment verification procedure for FLASH proton therapy based on time resolved film dosimetry. Med. Phys. 52, 1268–1280 (2025).

Castriconi, R. et al. Dose-response of EBT3 radiochromic films to proton and carbon ion clinical beams. Phys. Med. Biol. 62, 377–393 (2017).

Grilj, V. & Brenner, D. J. LET dependent response of GafChromic films investigated with MeV ion beams. Phys. Med. Biol. 63, 245021 (2018).

Khachonkham, S. et al. Characteristic of EBT-XD and EBT3 radiochromic film dosimetry for photon and proton beams. Phys. Med. Biol. 63, 065007 (2018).

Resch, A. F. et al. Dose- rather than fluence-averaged LET should be used as a single-parameter descriptor of proton beam quality for radiochromic film dosimetry. Med. Phys. 47, 2289–2299 (2020).

Palmer, A. L., Dimitriadis, A., Nisbet, A. & Clark, C. H. Evaluation of Gafchromic EBT-XD film, with comparison to EBT3 film, and application in high dose radiotherapy verification. Phys. Med. Biol. 60, 8741–8752 (2015).

Wang, G., Li, Y., Huang, X. & Chen, D. Polydiacetylene and its composites with long effective conjugation lengths and tunable third-order nonlinear optical absorption. Polym. Chem. 12, 3257–3263 (2021).

Nelson, P. N., Ellis, H. A. & White, N. A. S. Solid state 13C-NMR, infrared, X-ray powder diffraction and differential thermal studies of the homologous series of some mono-valent metal (Li, Na, K, Ag) n-alkanoates: a comparative study. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 145, 440–453 (2015).

Poulenat, G., Sentenac, S. & Mouloungui, Z. Fourier-transform infrared spectra of fatty acid salts—kinetics of high-oleic sunflower oil saponification. J. Surfactants Deterg. 6, 305–310 (2003).

Acknowledgements

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant number PJT 162294, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (DGECR-2020-06539, DGECR-2023-05772, CREATE MTA-565163-2022), Canada Foundation for Innovation (12939, 41723), and the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (CFREF-2015-00013 and CFREF-2022-00010) programs are all thanked. TRIUMF receives federal funding with thanks via a contribution agreement with the National Research Council of Canada. Sebastian Tattenberg is the recipient of a Mitacs Accelerate Fellowship. Rohith Kaiyum is the recipient of a Mitacs Training Award. The authors thank Mason Hegyes for jig construction and AutoCAD support. The authors also thank Dr. Darcy Burns and Dr. Sherry Yizhe Dai at the University of Toronto for solid-state NMR measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

These authors jointly supervised this work: Ozzy Mermut and Alexandra Rink. R.K.: methodology, investigation and data acquisition (dosimetry with photon and proton beams, Raman spectroscopy), analysis (Matlab code for dosimetry, Raman spectroscopy), interpretation of data, initial draft and revisions. C.H.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation and data acquisition (proton beams), interpretation of data, revisions. S.T.: data acquisition (proton beams), initial draft. R.L.S.: methodology, investigation, data acquisition and analysis (13C ssNMR, ATR-FTIR), interpretation of data, revisions. O.M.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, interpretation of data, initial draft, and revisions. A.R.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, interpretation of data, initial draft, and revisions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Hiroshi Yasuda, Amy Hall and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jet-Sing Lee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaiyum, R., Hoehr, C., Tattenberg, S. et al. Evaluation of radiochromic formulations for dosimetry in high-energy photon and proton beams. Commun Mater 6, 257 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00978-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00978-x