Abstract

Hydrogen embrittlement accompanied by cracking along general grain boundaries (GBs), which are characterized by a lack of crystallographic symmetry, is a persistent challenge in developing high-strength structural alloys. We develop a highly accurate and transferable machine learning interatomic potential (MLIP) for Fe–H by acquiring comprehensive and efficient learning data via simultaneous learning. Our MLIP accurately describes the density functional theory results for various lattice defects in α-Fe and their interactions with hydrogen, general GBs with hydrogen segregation, and their deformation and fracture behavior. Large-scale molecular dynamics simulations reveal that hydrogen can suppress <111 > /2 full dislocation emissions from general GBs and thereby potentially promote their fracture, supporting experimental suggestions. In contrast, for general GBs, where deformation twins are responsible for plasticity, the influence of hydrogen is minimal. This study contributes to the development of high-strength alloys by providing a robust MLIP construction methodology and new insights into hydrogen embrittlement mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Green hydrogen can be sustainably produced from water using renewable energy, and is gaining attention as a core energy carrier for achieving a decarbonized society. However, the reliability of the structural materials at each stage of production, transportation, storage, and utilization remains a technical bottleneck1. In particular, hydrogen embrittlement is a critical issue that significantly degrades the ductility and toughness of metallic materials, leading to reduced design lifetimes and sudden failures2,3,4. Hydrogen embrittlement has been reported in various structural materials, including ferritic steels5,6,7,8, martensitic steels9,10,11,12,13, austenitic stainless steels14,15,16, nickel alloys17,18,19, aluminum alloys20,21,22, and titanium alloys23,24. Widely accepted mechanisms for hydrogen embrittlement include hydrogen-enhanced local plasticity (HELP)25, hydrogen-enhanced decohesion (HEDE)26, and hydrogen-enhanced strain-induced vacancies (HESIV)27, as well as the adsorption-induced dislocation emission (AIDE) model28. These mechanisms act in combination depending on the microstructure and hydrogen concentration, making it difficult to understand hydrogen embrittlement1.

While a higher strength is desirable for materials from the perspective of hydrogen storage density and structural optimization, it generally increases hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility. In high-strength alloys, cracking often occurs preferentially at the grain boundaries11,22,29,30. In high-strength steels, this tendency is particularly pronounced at so-called general grain boundaries, which account for the majority of grain boundaries, lack specific symmetry, and cannot be explained by the corresponding lattice model11,31,32,33. Therefore, understanding the effect of hydrogen on general grain boundaries and their deformation and fracture behaviors is essential for elucidating and suppressing hydrogen embrittlement.

Because it is difficult to experimentally observe hydrogen near grain boundaries34, approaches using computational materials science have been widely used35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. However, owing to computational cost constraints, density functional theory (DFT) cannot handle the behavior of hydrogen in general grain boundaries and during deformation. Therefore, empirical interatomic potentials are widely used in hydrogen embrittlement analysis44. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on interatomic potentials that can be used to accurately analyze the atomic environment related to hydrogen embrittlement, including the behavior of hydrogen at grain boundaries, which is particularly important for hydrogen embrittlement in high-strength alloys.

For example, the embedded atom method (EAM) potential45,46,47,48, which is widely used in most studies on the Fe-H binary system, significantly underestimates the grain boundary energy49 and causes unphysical behavior derived from simplified functions at screw dislocations and crack tips50,51,52. Recently, highly accurate machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have been proposed for various systems53,54,55. For the Fe–H binary system, MLIPs56,57 based on the Behler–Parrinello neural network potential (BNNP)58 and deep potential (DP)57 frameworks have been proposed, which are beginning to overcome the limitations of empirical potentials such as EAM56,57.

However, even with these MLIPs, it is not possible to reproduce the behavior of grain boundaries and hydrogen at the grain boundaries, which is particularly important for hydrogen embrittlement in high-strength alloys. Specifically, the training dataset includes some symmetric tilt grain boundaries, resulting in large force errors at other grain boundaries and a significant underestimation of the grain boundary energy at finite temperatures59. Furthermore, only Σ5(310) grain boundaries are considered as training datasets for grain boundaries containing hydrogen56. Although the development of so-called universal MLIPs60,61,62 has been remarkable, sufficient accuracy cannot be obtained, at least for Fe-based alloys63.

In this study, we constructed an MLIP for Fe-H capable of accurately analyzing hydrogen embrittlement behavior in grain boundaries, including general grain boundaries, which is essential for the development of high-strength alloys. This was achieved by applying a concurrent learning strategy64 to a series of atomic structures, including generalized stacking faults, surfaces, symmetric tilt grain boundaries, and vacancy clusters, and obtaining a training dataset by comprehensively and efficiently sampling the atomic environment related to hydrogen embrittlement. The obtained MLIP reproduces the physical properties of α-Fe and various lattice defects with DFT-accuracy, including their interactions with hydrogen, and captures the effects of hydrogen on general grain boundaries, as well as their deformation and fracture behavior. Large-scale molecular dynamics analysis using the obtained MLIP clarified the segregation behavior of hydrogen in the general grain boundaries of Fe and its effect on the deformation and fracture behavior. The results were consistent with the suggestions from previous experimental results65. Therefore, this study is significant in that it is the first to realize an MLIP that enables high-precision analysis of hydrogen embrittlement in general grain boundaries at the atomic scale, which is essential for the development of high-strength alloys. Further, this study clarifies the direct relationship between hydrogen segregation and grain boundary fractures using MLIP. In addition, the efficient training dataset construction method based on concurrent learning and MLIP design guidelines focusing on defect structures presented in this study can be applied not only to the Fe-H system but also to other structural materials. This can accelerate material development for hydrogen utilization and provide a comprehensive understanding of hydrogen embrittlement mechanisms.

Results and discussion

Construction of MLIP in Fe-H binary system

To obtain a compact and appropriate training dataset covering all atomic environments relevant to hydrogen embrittlement at general grain boundaries in α-Fe, we applied the concurrent learning strategy available in the DP-GEN software64. This iterative workflow consisted of three steps: learning, exploration, and labeling (DFT calculations; Fig. 1). In this study, we applied this workflow to a series of atomic structures related to hydrogen embrittlement (strained bulk, grain boundaries, surfaces, and generalized stacking faults). Particularly, during the exploration process, which corresponds to the sampling of the learning data structure using MLIP, hydrogen diffused significantly in each atomic structure composed of Fe. Therefore, concurrent learning is particularly effective for sampling atomic environments related to hydrogen. Table 1 lists the training datasets and fitting errors of the constructed MLIP. Following previous studies, we employed the DP framework66 for MLIP in a concurrent learning flow. Because the process required 169 training iterations in total, the use of node-parallel training available in DeePMD-kit was essential to reduce the overall training time. The details of the training dataset generation are provided in the “METHODS” section.

a Initial training dataset is created using DFT (an example of a structure is shown in the figure). b Four deep potentials (DPs) are learned using different initial parameters. c Using one of the DPs, molecular dynamics calculations are performed under multiple conditions (temperature, pressure, etc.) for atomic structures for exploration, and many atomic structures can be created. Evaluate the force error between the four DPs for these atomic structures and select structures whose error exceeds a certain threshold. d Perform DFT calculations on the selected atomic structures and obtain additional learning data. Perform learning again, including the additionally obtained learning data. Repeat these cycles until the error after the exploration step reaches an acceptable level. In this study, we comprehensively performed this workflow on a series of atomic structures related to hydrogen embrittlement (examples of structures are shown in the figure, including hydrogen-containing bulk, grain boundaries, surfaces, and generalized stacking faults).

The MLIP was constructed using the final training dataset obtained from concurrent learning. The training dataset comprised 36,438 configurations (1,549,196 local atomic environments). Because this study used the CPU-based supercomputer Fugaku, the BNNP format, which offers an excellent balance between accuracy and performance when used with this computer, was adopted (Supplementary Note 1). The hyperparameters used in a previous study56 were slightly modified, and training was performed using n2p267. The root mean square error (RMSE) for energy (normalized by the number of atoms) and atomic force in the entire training dataset was 4.09 meV/atom and 109.16 meV/Å, respectively. These values are similar to those reported for Fe-H BNNP in a previous study56. As described above, the concurrent learning flow employed the DP framework, while the final MLIP training was conducted using the BNNP framework. This raises potential concerns regarding the transferability of model uncertainty owing to the differences between the two frameworks. However, as shown in the “Results and Discussion” section, the excellent accuracy and transferability of the obtained BNNP model validate the reliability of this approach.

Calculation accuracy of the constructed MLIP for the Fe-H binary system

To evaluate the calculation accuracy of the obtained MLIP, we calculated the physical properties of α-Fe, formation energy of lattice defects, and interaction energy between lattice defects and hydrogen using MLIP, and compared the results with those obtained from DFT (see the “Methods” section for the calculation conditions). For comparison, we used the Fe-H binary BNNP from a previous study56. Although DP57 was also constructed using the same training data, BNNP was superior to DP in terms of fitting accuracy and the physical properties evaluated in this study, as well as the lattice defects and their interactions with hydrogen57. Therefore, the BNNP was used for comparison. This choice was useful for clarifying the influence of the training dataset constructed in this study. Furthermore, we compared the results with the EAM potential45,48, which is the most widely used potential in hydrogen embrittlement studies. In addition, comparisons were made with previous DFT56,68,69 and experimental70,71,72 values. Hereafter, we refer to the BNNP simply as MLIP.

As shown in Supplementary Note 2, the physical properties of α-Fe and the formation energies of lattice defects calculated using the MLIP constructed in this study reproduced the DFT calculations with accuracy comparable to that of previous MLIP. Furthermore, they are in good agreement with the previous DFT calculations56 and reproduce the experimental results70,71,72 with comparable DFT-level accuracy. In addition, the generalized stacking fault energy and the energy of the screw dislocation core structure, which play important roles in the plastic deformation behavior of α-Fe, were also reproduced with accuracy comparable to that of previous MLIP.

Figure 2 shows the calculation accuracy of the constructed MLIP for systems that are particularly important for the behavior of hydrogen in α-Fe. The constructed MLIP reproduced the DFT results for the hydrogen solution energy at the tetrahedral sites in α-Fe under uniaxial strain and hydrostatic strain (Fig. 2a and b). This plays an important role in the interaction of hydrogen with various lattice defects and in the stability of hydrogen during deformation. Furthermore, the MLIP constructed in this study reproduced the DFT more accurately than the MLIP in previous studies in terms of the interaction between hydrogen and screw dislocation, which is a particularly important effect of hydrogen on plastic deformation behavior (Fig. 2c). In previous studies on MLIP, screw dislocation was explicitly included in the learning data; however, it was not included in our study. The effect of hydrogen on the generalized stacking fault energy of the (112) plane, which is related to the interaction between twins and hydrogen, was slightly larger than that obtained from the DFT (Fig. 2d); however, it reproduced the effect of hydrogen well (see Supplementary Note 2). The constructed MLIP also reproduced the DFT well for the interaction between single vacancies and hydrogen (Fig. 2e) and the surface segregation energy to low-index surfaces (Fig. 2f). Furthermore, these results are in good agreement with previous DFT calculations68,69. The dependence of the hydrogen molecule energy on the binding length also agrees well with the DFT results (Fig. 2g). The MLIP constructed in this study also reproduced DFT better than previous MLIP for the interaction energy between hydrogen atoms in α-Fe bulk, and successfully reproduced the repulsive interaction between hydrogen atoms at neighboring sites (Fig. 2h).

a, b Hydrogen solution energy at tetrahedral sites in α-Fe under uniaxial strain and hydrostatic pressure, respectively. c Segregation energy of hydrogen to the easy core structure of screw dislocation. d (112) generalized stacking fault energy when hydrogen is positioned at tetrahedral sites on generalized stacking faults. e Interaction energy between a single vacancy and multiple hydrogen atoms. f Segregation energy of hydrogen for the most stable site on a low-index surface. g Bond length dependence of the energy of hydrogen molecules. h Interaction energy between hydrogen atoms at tetrahedral sites in the bulk. For comparison, results obtained from DFT, the MLIP of previous study, and EAM are also shown. In a, b, c, e, and h, the positions of hydrogen atoms corresponding to the horizontal axis are also shown.

Next, we demonstrated the accuracy of the calculation of the hydrogen segregation energy at symmetric tilts and general grain boundaries. For details on the calculation method, see Supplementary Note 3. Figure 3 shows the accuracy of the hydrogen segregation energy for seven types of symmetric tilt grain boundaries. The MLIP constructed in this study reproduced the DFT results for the hydrogen segregation energy at symmetric tilt grain boundaries. The RMSE of the hydrogen segregation energy at the seven grain boundaries was 0.035 and 0.102 eV for the MLIP constructed in this study and previous studies, respectively, clearly demonstrating the excellent accuracy of the constructed MLIP. Given that the segregation energy governs the hydrogen occupancy probability at a given site in an exponential manner36, even a modest difference in its accuracy can lead to substantial discrepancies in the predicted behavior, underscoring the critical importance of accurate modeling. At a few sites (Fig. 3a, b), the segregation energies calculated by DFT and the MLIP constructed in this study differed significantly. This corresponds to the case in which hydrogen moves from its initial position to another site during the relaxation process when the relaxation is performed using MLIP. This may be due to the differences in relaxation conditions between the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) and LAMMPS.

a–g Hydrogen segregation energy at seven symmetric tilt grain boundaries of Σ3(112), Σ3(111), Σ5(210), Σ5(310), Σ9(114), Σ9(221), and Σ11(113). The atomic structure near the grain boundary center is shown, with Fe atoms represented in blue and white and color-coded according to the difference in coordinates in the direction perpendicular to the paper (rotation axis). The coordinates of hydrogen obtained from DFT relaxation are shown in red. The segregation sites at each grain boundary are numbered in order of their distance from the grain boundary center. h Comparison of the results obtained from DFT and interatomic potentials for the segregation energy at all sites in seven grain boundaries. The root mean square error (RMSE) is also shown.

Figure 4 shows the calculation accuracy for the hydrogen segregation energy at the general grain boundaries. Here, general grain boundaries are included in a structure relaxed using a moment tensor potential (MTP)59 that reproduces recently proposed general grain boundaries with DFT accuracy using an initial structure of nanopolycrystals with random orientations created by Voronoi tessellation. Figure 4a shows the average grain boundary energy when the number of crystal grains was fixed at eight and the cell size was varied. In both cases, the average grain boundary energy tended to converge to a constant value as the cell size (i.e., grain size) increased, and the average grain boundary energy obtained by both MLIPs agreed well with that obtained by MTP. This is also close to the value estimated from the experiments73. Therefore, the constructed MLIP exhibited excellent accuracy, even for general grain boundaries. As shown in Fig. 4b, we extracted calculation cells capable of performing DFT calculations from a nanopolycrystal relaxed by MTP with a cell size of 28.8 nm, and evaluated the segregation energy when hydrogen was placed near the center of the calculation cell, where the influence of periodic boundary conditions was minimal. It should be noted that the purpose of these calculations was not to determine the segregation energy precisely, but to validate the accuracy of the potentials. The MLIP constructed in this study also reproduced the DFT well for the segregation energy of hydrogen at general grain boundaries. The RMSE of the segregation energy was 0.042 and 0.103 eV for the MLIP constructed in this study and previous studies, respectively. In other words, the RMSE of the MLIP constructed in this study for general grain boundaries was equivalent to that of the symmetric tilt grain boundaries explicitly included in the training dataset. This result suggests excellent transferability of the constructed MLIP.

a Relationship between the average grain boundary energy and model size in nano-polycrystals with eight crystal grains. For comparison, the general grain boundary energy of α-Fe estimated from experimental results [64] and the results obtained using MTP, MLIP, and EAM in previous studies are also shown. b Calculation method of hydrogen segregation energy at general grain boundaries and an example of the calculation cell used. Blue represents Fe atoms, and red represents the initial position of hydrogen used to evaluate the segregation energy. c, d, and e show a comparison of the results obtained from DFT and interatomic potentials for the segregation energy of a total of 85 sites in five extracted grain boundaries. The root mean square error (RMSE) for the hydrogen segregation energy is also shown.

Effect of hydrogen segregation on deformation and fracture behavior of general grain boundaries

The effect of hydrogen segregation at grain boundaries on the deformation and fracture behavior of general grain boundaries is analyzed using the constructed MLIP (see the “Methods” section for details of the analysis method). The effect is discussed in relation to the grain boundary segregation state in the actual experiments. Most previous analyses on the effect of hydrogen grain boundary segregation have been performed on symmetrical grain boundaries defined by CSL using EAM. Furthermore, the number of hydrogen atoms in the entire grain boundary model was fixed and uniaxial tensile testing was performed from a state in which grain boundary segregation was induced by MD. In this case, because the amount of grain boundary segregation is determined according to the given number of hydrogen atoms, it is not possible to evaluate the effect on the deformation behavior of the grain boundaries by considering the change in the amount of grain boundary segregation of hydrogen according to the grain boundary characteristics. In this study, we investigated the deformation behavior of grain boundaries, which reflects the amount of grain boundary segregation according to the grain boundary characteristics, by applying a bulk hydrogen concentration, that is, a hydrogen charge condition. The grain boundary segregation energy contributes exponentially to the probability of hydrogen existing at each grain boundary site through the grand canonical Monte Carlo/molecular dynamics hybrid method (GCMC/MD)74. MLIP has a significant advantage for this purpose because it can reproduce the hydrogen grain boundary segregation energy at various grain boundaries with DFT-accuracy. In the experiments, lattice defects other than grain boundaries, such as dislocations, also exist75, making it difficult to accurately determine the bulk hydrogen concentration that is not trapped in these lattice defects. Therefore, it is not possible to compare bulk hydrogen with the experimental results. In contrast, the hydrogen grain boundary coverage of high-purity Fe has been determined in recent experiments by Sato et al.75. By comparing the amount of grain boundary segregation obtained from the calculations with the experimental results, it is possible to discuss the effect of hydrogen segregation on the deformation and fracture behavior of general grain boundaries in correspondence with the experiments. Furthermore, the calculation accuracy of the constructed MLIP for the deformation and fracture behaviors of clean and hydrogen-segregated grain boundaries was verified using an extrapolation grade based on the local atomic environment76, and the validity of the obtained analysis results was verified.

Previous analyses using empirical interatomic potentials have been limited by the high computational cost of molecular dynamics simulations at the atomic scale. Even in recent studies of grain boundary fracture, only a few grain boundary models, typically comprising several hundred thousand atoms, have been simulated at a strain rate of 1 × 108/s38,43,77, which is considerably higher than the strain rates employed in experiments on hydrogen embrittlement78. Nevertheless, these studies have provided valuable insights into hydrogen embrittlement accompanied by grain boundary fracture38,43,65. In the present analysis, although the employed MLIP entails approximately 100 times higher computational costs than thoese using empirical interatomic potentials, uniaxial tensile simulations were performed on six bicrystal models containing general grain boundaries, each comprising several hundred thousand atoms, as described below. Therefore, a strain rate of 1 × 108 /s was adopted as the lowest computationally feasible value. As a result, the diffusion of hydrogen and vacancies during deformation—which plays a significant role in hydrogen embrittlement under lower strain rates—may not be fully captured. The implications of this limitation for the consistency between simulation and experimental results are discussed at the end of this section.

For this analysis, we used six bicrystal grain boundary models containing general grain boundaries, as shown in Table 2. The misorientation angles of the six bicrystal models containing general grain boundaries ranged from 25.4 to 47.91° and the grain boundary energies ranged from 1.65 to 1.87 J/m2. Figure 5a, b shows an example of a grain boundary model of GGB 1 containing a general grain boundary with a crystal orientation difference of 35.18° and a grain boundary energy of 1.65 J/m2. The grain boundaries in this study do not have a specific symmetry. The general grain boundaries included in these six grain boundary models have similar properties to those included in the nanopolycrystal model in terms of the relationship between the crystal orientation difference and grain boundary energy (see Supplementary Note 4). The average grain boundary energy of the grain boundaries included in the nanopolycrystal model is close to the experimental value, as described above, and is commonly used in uniaxial tensile analyses. Its validity has been proven in analyses of the deformation and fracture behavior of nanopolycrystals49,79.

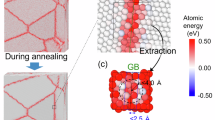

a, b Atomic structure and color map of the energy of each atom in GGB 1, which is an example of a bicrystal grain boundary model. The energy reference is the energy of Fe atoms in a perfect crystal. c Relationship between bulk hydrogen concentration and grain boundary hydrogen concentration for general grain boundaries included in the bicrystal model. The relationship for Σ3(111) and Σ3(112) is also shown for comparison. d Hydrogen concentration profile near grain boundaries in GGB1. e, f Probability densities of Voronoi volume and coordination number of hydrogen segregated in the one atomic layer (2.5 nm) region from the grain boundary center in GGB1. g Atomic structure near the grain boundary center of GGB1 when the bulk hydrogen concentration is 0.0044 at.%. Here, white represents Fe atoms, and red, black, and blue represent hydrogen atoms with coordination numbers of 6 (octahedral sites), 5, and 4 (tetrahedral sites), respectively.

Figure 5c shows the hydrogen segregation state at 300 K as a function of the bulk hydrogen concentration for the six general grain boundary models obtained by the GCMC/MD hybrid method. In all grain boundaries, the grain boundary hydrogen concentration (in the region 2.5 Å from the grain boundary center) increases linearly with the bulk hydrogen concentration within the calculated bulk hydrogen concentration range. In the following, the systems with bulk hydrogen concentrations of 0.0019 and 0.0023 at%, and 0.0044 at% are referred to as Low H, Middle H, and High H, respectively. The corresponding grain boundary hydrogen concentrations are approximately twice as high for Middle H and about five times higher for High H compared with those for Low H. The average grain boundary hydrogen concentration in the case of high H for GGB 1–6 was 18.1 at%, with a standard deviation of 2.1 at%. At this time, the hydrogen concentrations at the grain boundaries of Σ3(111) and Σ3(112), which were shown for comparison, were 25.2 and 4.80 at%, respectively. A comparison of these results indicates that the dependence of the hydrogen concentration at the grain boundaries on the grain boundary characteristics is relatively small in general grain boundaries.

To clarify the hydrogen segregation state at the atomic level in general grain boundaries, the grain boundary segregation state of GGB 1 was analyzed in detail. As can be understood from the fact that the grain boundary hydrogen concentrations in GGB 1–6 are comparable, the analysis results of other grain boundaries are similar to those for GGB 1. Hydrogen segregation is concentrated in the one atomic layer (2.5 Å) region from the grain boundary center (Fig. 5d). Figure 5e shows the Voronoi volume and coordination number of the segregated hydrogen atoms obtained from the Voronoi analysis of the atoms near the grain boundary for each bulk hydrogen concentration. This result indicates that the primary hydrogen segregation sites are those with Voronoi volumes larger than those in the bulk and with coordination numbers of six, that is, octahedral sites (Fig. 5e, f). As the bulk concentration of hydrogen increased, hydrogen segregation tended to occur even at relatively small Voronoi sites (Fig. 5e). Figure 5g shows the atomic structure near the grain boundary in the case of a High H, indicating that hydrogen segregates into expanded octahedral sites near the grain boundary. Sato et al. analyzed the grain boundary segregation of hydrogen in general grain boundaries when hydrogen was cathodically electrolyzed into high-purity Fe. They showed that the hydrogen occupancy in general grain boundaries (large grain boundaries) was 2.3–2.9 atom/nm2[ 75. In the calculation results, the values for middle H and high H in GGB 1 were 1.4 and 6.7 atom/nm2, respectively. These results indicate that the hydrogen segregation sites in general grain boundaries of high-purity Fe are octahedral sites with large Voronoi volumes.

Figure 6a shows the stress–strain curves obtained by the uniaxial tensile analysis for the six general grain boundary models. In GGB 1–3, the maximum stress was observed at the moment of <111>/2 full dislocation emission from the grain boundary. In contrast, in GGB 4-6, the maximum stress was observed at the moment of deformation-twinning formation at the grain boundary. As discussed later, the deformation twins were generated through the successive emission of <111>/6 partial dislocations on adjacent (112) planes. Therefore, although dislocations are involved in the deformation of all grain boundaries, GGB 1–3 are hereafter referred to as grain boundaries where dislocations are responsible for plasticity, while GGB 4–6 are referred to as those where deformation twins govern plasticity. In all cases, no grain boundary fracture occurred at a strain of 20%. The maximum stress in GGB 1–3 was in the range of 10.6–11.4 GPa. In contrast, the maximum stress in GGB 4–6 was in the range of 9.3–9.8 GPa, and tended to occur at stresses lower than those at which <111>/2 full dislocation emission occurred. In the deformation of polycrystals with grain sizes in the Hall-Petch region analyzed using MTP, which reproduces the DFT well for general grain boundaries and their deformation behavior (i.e., when grain boundary sliding is not dominant),it has been shown that <111>/2 full dislocation emission from grain boundaries and deformation twinning are responsible for plasticity in the case of uniaxial tensile deformation performed at strain rates similar to those in this study49. Therefore, the bicrystal model used in this study was effective in analyzing the main deformation mechanisms observed in the uniaxial tensile analysis of general grain boundaries. The maximum stresses for the Σ3(111) and Σ3(112) grain boundaries were 15.4 GPa and 13.3 GPa, respectively. For the Σ3(111) grain boundary, <111>/2 full dislocation emission occurred at the maximum stress, and fracture occurred at the grain boundary immediately after. In contrast, for the Σ3(112) grain boundary, deformation twinning formed from the grain boundary and the maximum stress was observed, but no fracture occurred. Thus, the general grain boundaries used in this study showed lower maximum stress than grain boundaries with smaller Σ values.

a Stress–strain curve in bicrystal models containing clean general grain boundaries. b, c Effect of hydrogen on stress-strain curves of GGB 1 and GGB 3, respectively, where dislocation emission from grain boundaries is responsible for plasticity. d Effect of hydrogen on maximum stress and grain boundary fracture strain of GGB 1-3, where dislocation emission from grain boundaries is responsible for plasticity. e Atomic structures at strains near the maximum stress of GGB 1. f Interaction between dislocations emitted from grain boundaries and hydrogen in GGB 1. g Atomic structures at strains near the maximum stress of GGB 3. h Effect of hydrogen on stress-strain curves of GGB 4, where deformation twinning formation from grain boundaries is responsible for plasticity. i Effect of hydrogen on maximum stress and grain boundary fracture strain in GGB 4–6, where deformation twinning formation from grain boundaries is responsible for plasticity. j Atomic structures at strains near the maximum stress of GGB 4. k Nucleation mechanism of a deformation twin from the grain boundary in GGB4. The nucleation starts with the emission of a twinning partial I1 on the {112} plane. In d and i, a grain boundary fracture strain change of 0% means that no grain boundary fracture has occurred, and positive values represent the amount of grain boundary fracture strain reduction based on a reference value of 20%. In e, f, g, j and k, the blue and white spheres represent bcc and unclassified Fe atoms, respectively, while the red spheres represent hydrogen atoms. In e, the yellow-green, pink, and light blue lines are dislocation lines obtained by dislocation analysis, and the yellow-green lines represent \(1/2\left\langle 111\right\rangle\) full dislocations.

Figure 6b, c shows typical examples of the effects of hydrogen on the deformation and fracture behavior of GGB 1 and GGB 3, respectively, in which dislocations are responsible for plasticity. In GGB 1-3, except for the High-H case of GGB 3, where <111>/2 full dislocation emission dominates the maximum stress, hydrogen segregation tends to increase the maximum stress compared to the case without hydrogen (Fig. 6b-d). This result indicates that <111>/2 full dislocation emission is suppressed by hydrogen segregation. Figure 6e shows the atomic structure immediately after the maximum stress was applied, together with the results of dislocation analysis using the dislocation extraction algorithm (DXA)80. There was no significant change in the dislocation emission position due to hydrogen segregation. In addition, immediately after dislocation emission, the dislocation lines continued within the grain boundaries. This indicates that dislocations within the grain boundaries protrude into the grains, causing dislocation emission. In the case of the Middle H, no hydrogen was detected at the protruding dislocation sites, but hydrogen was present near the dislocation lines that remained within the grain boundaries (Fig. 6f). This result suggests that the suppression of <111>/2 full dislocation emission arises from the pinning effect of hydrogen on dislocations. However, hydrogen is present at the grain boundaries and constantly diffuses, and atoms near the grain boundaries have larger atomic vibrations than those in the bulk, owing to the increased strain. Therefore, the dislocation lines obtained using DXA significantly changed at each time step. Therefore, it is difficult to analyze the interactions between the dislocations detected by DXA and hydrogen in further detail. For GGB 1 under high H, microcracks occurred at the grain boundaries without dislocation emission at the maximum stress, and the rapid propagation of these microcracks led to grain boundary fracture. Consequently, the fracture strain of GGB 1 was significantly reduced (Fig. 6b).

In GGB 2 and in GGB 3, except for the High-H case, the deformation behavior was qualitatively similar to that of GGB 1: hydrogen increased the maximum stress, and at higher hydrogen concentrations, the fracture strain decreased. Specifically, in the Middle-H case of GGB 2, hydrogen caused an increase in the maximum stress and a reduction in the fracture strain associated with grain boundary failure. However, unlike in GGB 1, grain boundary fracture did not occur immediately after the maximum stress; deformation continued with dislocation emission from the grain boundary. Grain boundary fracture eventually occurred after the stress reached a second peak (the first being the maximum) at around 14% strain. In contrast, in the Low-H case of GGB 2, deformation accompanied by dislocation emission continued even after the second stress peak, and grain boundary fracture did not occur. In the High-H case of GGB 2, no dislocation emission was observed, and grain boundary fracture occurred at 10% strain immediately after the maximum stress.

In GGB 3, the Low-H and Middle-H cases exhibited a slight increase in peak stress relative to the clean grain boundary (Fig. 6c, d). Pronounced grain boundary migration occurred from around 6% strain in the clean, Low-H, and Middle-H cases of GGB 3. In the Low-H and Middle-H cases, dislocations were emitted from protrusions formed by this migration at around 8% strain (Fig. 6g), after which the peak stress was reached (Fig. 6c). In the clean grain boundary, continuous dislocation emission persisted even beyond the strain corresponding to the peak stress, and no grain boundary fracture occurred. In contrast, in the Low-H and Middle-H cases, although dislocation emission continued beyond the peak-stress strain, the stress monotonically decreased afterward, eventually leading to fracture. Thus, in the Low-H and Middle-H cases of GGB 3, hydrogen suppressed dislocation emission and promoted grain boundary fracture. Conversely, in the high-H case of GGB 3, the peak stress decreased compared with the clean grain boundary. This is because grain boundary migration was suppressed at the high hydrogen concentration, and fracture occurred without dislocation emission. Thus, the high-H result for GGB 3 suggests that strong hydrogen segregation suppresses grain boundary migration, making it difficult for the accumulated elastic energy to be released. Consequently, grain boundary fracture occurred at a relatively low stress, again without dislocation emission. Thus, in GGB 1–3, except for the High-H case of GGB 3, hydrogen suppressed the <111>/2 full dislocation emission from general grain boundaries and promoted grain boundary fracture. The relationship between the suppression of dislocation emission and grain boundary failure will be discussed later.

In GGB 1, grain boundary cracking occurred in the Low-H case, and the fracture strain decreased. In GGB 2, grain boundary cracking occurred even in the Middle H case, with a similar decrease in fracture strain. The grain boundary hydrogen concentration in the Middle H case was lower than that in the experiment by Sato et al.75. These results indicate that <111>/2 full dislocation emission suppression and grain boundary cracking occur at hydrogen concentrations that can be experimentally determined. In contrast, Wan et al. showed that hydrogen promotes dislocation emission from grain boundaries in uniaxial tensile analysis of Σ9 twisted grain boundaries using EAM43. Although the details are unclear because no analysis of the emitted dislocations was performed, based on the results of this study, the nature of the emitted dislocations, concentration of segregation, and differences in the interatomic potential used may have had an effect.

Figure 6h shows typical examples of the effects of hydrogen on the deformation and fracture behavior of GGB 4, in which deformation twins are responsible for plasticity. In GGB 4–6, the effect of hydrogen on the maximum stress and fracture was minor (Fig. 6i). Although fracture occurred in GGB 6, the deformation twins that grew from the grain boundaries reached the fixed part at the end of the cell where the fracture occurred. Therefore, the change in the grain-boundary fracture strain was set to zero, as shown in Fig. 6i. The grain boundary hydrogen concentration in GGB 4-6 was not significantly different from that in GGB 1–3 and was rather high. This indicates that the deformation mechanism of the grain boundaries plays a more important role than the hydrogen concentration at the grain boundaries in the grain-boundary sensitivity to hydrogen embrittlement. This may be related to the fact that twins are responsible for the plastic deformation of CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloys, whose mechanical properties were improved by hydrogen addition81. Deformation twins were generated by the successive emission of <111>/6 partial dislocations on adjacent (112) planes at the grain boundaries (Fig. 6j, k). This is consistent with the twin formation mechanism reported in molecular dynamics simulations of uniaxial tension in Mo82 and Ta83 nanocrystals. However, owing to relatively large atomic vibrations near the grain boundaries, the partial dislocations present within the grain boundaries could not be directly resolved, and their atomic-level interactions with hydrogen remain unknown. Understanding the interaction between twins nucleating from the grain boundary and hydrogen is a subject for future work. However, it should be noted that deformation mediated by deformation twinning in α-Fe may be limited to high strain rates49.

To verify the validity of the analysis results obtained using the constructed MLIP, we evaluated whether the atomic environment contained in the atomic structure during the uniaxial tensile testing of GGB 1 and GGB 4 was in the interpolation region or the extrapolation region of the atomic environment contained in the learning data using extrapolation grade76 based on the local atomic environment. As shown in Fig. 7, for GGB 1, where dislocation emission from grain boundaries is responsible for plasticity, and GGB 4, where deformation twinning at grain boundaries is responsible for plasticity, the atomic environment contained in the atomic structure during uniaxial tensile testing, the atomic environment is in the “interpolation” region, where high accuracy can be expected regardless of hydrogen concentration and strain, except for a few atoms. Some atoms have an extrapolation grade slightly larger than 1, but are still in the “accurate extrapolation” region. These results demonstrate the excellent accuracy and versatility of the MLIP and clarify the validity of the analysis results. As noted in Supplementary Note 1, the MTP used here was inferior to the BNNP both in terms of fitting accuracy and computational speed. Therefore, the BNNP was employed for the tensile analyses of the general grain boundaries.

a, b Strain dependence of the average and maximum extrapolation grades for all atoms (approx. 300,000 atoms) in the atomic structure during uniaxial tensile deformation for GGB 1, where dislocation emission from grain boundaries causes plasticity. c, d Atomic structure and color map of extrapolation grades at 12.0% strain when the bulk hydrogen concentration is 0.0019 at.% and 0.0044 at.%, respectively. e, f Strain dependence of the average and maximum extrapolation grades for all atoms in the atomic structure during uniaxial tensile testing of GGB 4, where deformation twinning from grain boundaries causes plasticity. If the extrapolation grade for the target atom is 0–1, it means that it is in the “interpolation” region; if it is 1-2, it means that it is in the “accurate extrapolation” region; and if it is 2 or more, it means that it is in the “extrapolation” region. In c and h, the blue and white spheres represent bcc and unclassified Fe atoms, respectively, while the red spheres represent hydrogen atoms. The yellow-green, pink, and light blue lines are dislocation lines obtained by dislocation analysis. The yellow-green lines represent \(1/2\left\langle 111\right\rangle\) full dislocations.

Hereafter, we discuss the validity of the simulation results and their consistency with experimental observations. Although the high computational cost of the MLIP limited the analysis to six general grain boundary models, these models were sufficient to capture the two primary plastic deformation mechanisms previously identified for general grain boundaries in nanopolycrystals49. Ogawa et al. showed traces of dislocation emissions from grain boundaries near crack fronts that propagated along general grain boundaries in pure Fe subjected to low-stress fatigue testing in hydrogen gas84. Therefore, the present analysis—particularly regarding the effect of hydrogen segregation on dislocation emission from general grain boundaries—is likely directly relevant to hydrogen embrittlement accompanied by grain boundary cracking. To the best of our knowledge, there are no examples that have experimentally clarified this. Previous studies on uniaxial tensile analysis of grain boundaries using EAM have reported that hydrogen segregation promotes dislocation emission from Σ9 twisted grain boundaries43 and Σ3(111) symmetric tilt grain boundaries38, while hydrogen suppresses dislocation emission from <110> twisted grain boundaries77. However, these studies did not analyze the emitted dislocations, and the hydrogen concentration at the grain boundaries was fixed; therefore, it was unclear whether the hydrogen concentration corresponded to that in the experiment. Furthermore, because these studies relied on empirical interatomic potentials for their analysis, a unified understanding of dislocation emission from grain boundaries remains lacking. In contrast, the effect of hydrogen on dislocation motion in the bulk is increasingly understood from both experimental and theoretical perspectives. Specifically, very recent in situ SEM analyses have shown that hydrogen can both enhance and inhibit dislocation mobility, and that an increased hydrogen trapping at dislocation cores suppresses slip due to pinning85. Dynamic Monte Carlo calculations based on data obtained from DFT calculations show that, in the case of low stress and low bulk hydrogen concentrations, hydrogen promotes slip motion by increasing the generation rate of screw dislocation kinks, while in the case of high hydrogen concentrations, it has been shown that hydrogen traps and pins dislocations, thereby reducing the dislocation migration velocity86. Furthermore, recent studies using empirical potentials combined with the GCMC method have shown that even low concentrations of bulk hydrogen can pin edge dislocations through segregation87. These results suggest that pinning inhibits dislocation emission by dislocations detected at the grain boundaries where high concentrations of hydrogen are present. Overall, the findings of this study are consistent with recent experimental observations of dislocation–hydrogen interactions and do not contradict the assumptions of the HELP mechanism, wherein hydrogen can enhance dislocation motion under low-stress and low-hydrogen-concentration conditions.

Comparison with the experiments of Sato et al. indicates that the observed effects, namely, the influence of hydrogen segregation on dislocation emission from grain boundaries, can occur even under realistic hydrogen penetration conditions. Furthermore, Sugiyama et al.65 conducted a detailed analysis of the effect of hydrogen on the deformation behavior of pure Fe using electron channeling contrast imaging (ECCI) and electron backscattered diffraction, and obtained results suggesting that hydrogen suppresses dislocation emission from grain boundaries. The hydrogen charging conditions in their experiments were similar to those used by Sato et al., and therefore, the results of Sugiyama et al. strongly support the validity of the present computational findings. Furthermore, the hydrogen concentration at the grain boundaries can be further increased through other mechanisms, such as HELP, in which hydrogen promotes deformation88.

In contrast, even when the grain boundary hydrogen concentration was comparable, hydrogen had little effect on the formation and growth of deformation twins, and as a result, had little effect on grain boundary fracture. This result strongly suggests that, in addition to the decrease in the grain boundary cohesive energy, which is mainly explained by the grain boundary hydrogen concentration, the suppression of <111>/2 full dislocation emission promotes grain boundary fracture. Wang et al. calculated the effect of hydrogen on the grain boundary cohesive energy (i.e., the ideal work of separation) using DFT and empirical potentials and reported that the reduction in cohesive energy caused by hydrogen is at most ~44%89. They concluded that the transition from transgranular to intergranular fracture cannot be explained solely by the change in cohesive energy, namely, by the conventional HEDE mechanism89. Furthermore, Song et al. investigated the influence of hydrogen on crack propagation within the grain using empirical interatomic potentials and concluded that hydrogen promotes brittle fracture via the HEDE mechanism by suppressing dislocation emission from the crack tip48. Although the dislocation sources differ—crack tips in the grain interior versus grain boundaries—the present results support the same conclusion as that by Song et al., i.e., hydrogen-induced suppression of dislocation emission facilitates brittle fracture. Notably, our results were obtained from evaluations under hydrogen charge conditions using MLIP, which has excellent accuracy for grain boundary segregation.

In the present analysis, a high strain rate was employed. As a result, diffusion of hydrogen and vacancies during deformation may not have been fully realized. For example, an analysis of intragranular fracture using an empirical interatomic potential reported that hydrogen-induced vacancy formation can be captured at a strain rate of 1 × 105/s90. Nevertheless, dislocation pinning—the origin of the suppression of dislocation emission observed in the present simulations—may dominate across a wide range of strain rates at high hydrogen concentrations, as suggested by dynamic Monte Carlo calculations based on DFT data86. In fact, dislocation pinning has also been observed in in situ SEM experiments conducted without external stress85. Therefore, the results obtained under high strain rates in this study are likely consistent with experimental observations by Sugiyama et al.65.

As discussed above, computational cost constraints limited the present analysis to high strain rates and a small number of grain boundary models. In some of these models, other factors, such as grain boundary migration, also played a role, as observed in the high-H case of GGB 3. Future work will involve a more detailed investigation of the effects of strain rate and grain boundary character, and clarification of the relationship between dislocation emission and grain boundary fracture. Achieving this will necessitate the development of MLIPs that combine high accuracy with computational efficiency; efforts are currently underway to construct an improved MLIP using the training data generated in this study. In addition, applying accelerated molecular dynamics methods91,92 will be essential for practically exploring lower strain rates, and extending such accelerated approaches to include hydrogen effects remains an important challenge for future work.

Application of findings from this study

In this study, we applied a concurrent learning strategy to a series of atomic structures related to hydrogen embrittlement of α-Fe and successfully constructed a binary MLIP containing H with DFT accuracy and excellent transferability. Specifically, the constructed MLIP well reproduced the results obtained from DFT regarding the physical properties of α-Fe, lattice defects, and the interaction between them and hydrogen. Furthermore, the MLIP demonstrated DFT-accuracy in predicting hydrogen segregation at general grain boundaries, dislocation emission from grain boundaries, twinning formation, and crack initiation and propagation. Notably, DFT-accuracy was achieved for both general grain boundaries and screw dislocations in their interactions with hydrogen, even without explicitly including them in the training dataset, demonstrating the high transferability of the constructed MLIP. Therefore, the constructed MLIP can be applied to various analyses related to the hydrogen embrittlement of Fe and is expected to contribute significantly to the elucidation of the hydrogen embrittlement mechanism of steel. Furthermore, the MLIP construction method used in this study was not limited to an Fe-H binary system. This study contributes to the development of high-strength alloys with carbon neutrality by proposing an MLIP construction method.

Furthermore, although this study dealt with the construction of MLIP for H, which is an interstitial element, it also provided important insights for the construction of MLIP for binary systems of metallic and interstitial elements. Specifically, one of the factors contributing to the success of the construction in this study was that hydrogen, which is an interstitial element, significantly diffused into the host metal Fe during the search process in concurrent learning. This allowed us to include various atomic environments surrounding hydrogen comprehensively in the learning data. Because the MD calculations in the MLIP search process are performed on small atomic structures, the computational cost is low. Therefore, this method is also effective for systems containing interstitial elements with activation energies higher than that of H. Recently, it has been shown that MLIPs with excellent accuracy for general grain boundaries59 and their deformation and fracture behaviors49 can be constructed using diverse and large atomic structures based on crystal space groups as learning data93. This method can also be applied to the substituted alloy systems94. More recently, it was shown that it is possible to construct a highly general-purpose MLIP using a defect genome constructed by sampling with empirical interatomic potentials and a training dataset constructed by converting atomic clusters into periodic structures95. However, there are no examples demonstrating the effectiveness of these methods in constructing MLIPs for binary systems containing general-purpose interstitial elements. Furthermore, even universal MLIPs60,61,62 significantly underestimate the activation energy of the diffusion of C, which is an interstitial element, at least in Fe systems63. Therefore, this study proposes an effective method for constructing a general-purpose high-precision MLIP for binary systems containing interstitial elements.

In the present work, we developed a Fe–H binary MLIP and analyzed the effect of hydrogen segregation on the deformation behavior of general grain boundaries. However, actual high-strength steels contain alloying elements such as C, Si, Mn, Cr, Mo, and Ni4. In particular, carbon influences grain boundary deformation via hydrogen segregation, grain boundary cohesive energy, and other mechanisms96,97. Therefore, since the current system is limited to the Fe–H binary system, extending the analysis to at least ternary systems, including Fe–H and alloying elements is desirable to gain insights into the improving hydrogen embrittlement resistance in high-strength steels, and we are currently working on this extension. Applying the method used here to construct a ternary MLIP, however, may require an enormous amount of learning data owing to combinatorial explosion. This issue is expected to be resolved by a more sophisticated MLIP construction method using concurrent learning proposed recently98.

Methods

DFT calculation

Spin-polarized electronic structure calculations and structural relaxations for obtaining the training dataset and evaluating the accuracy of MLIP were carried out using the VASP with the projector-augmented wave method99,100 within the generalized gradient approximation framework using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange–correlation functional101. Pseudopotentials treat the 4s and 3d electrons as valence states, following the convention adopted in prior machine learning interatomic potential (MLIP) studies56,57. The plane-wave energy cut-off was set to 520 eV. Brillouin zone sampling was performed using Monkhorst–Pack grids102 with a density equivalent to a 18 × 18 × 18 mesh for the α-Fe conventional unit cell. The employed k-point mesh and cutoff energy were chosen to ensure convergence and were more stringent than those used in a previous study56,57. A Methfessel–Paxton smearing scheme103 with a width of 0.1 eV was applied. Geometry optimizations were performed until the total energy and atomic forces converged to within 10⁻⁶ eV and 10⁻² eV/Å, respectively. These settings were comparable to or better than the calculation accuracies used in previous studies56,59. Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations were conducted under NVT ensembles using Parrinello–Rahman dynamics combined with a Langevin thermostat104,105, with a time step of 0.5 fs.

Calculations using interatomic potentials

All calculations using interatomic potentials were performed using LAMMPS106. Atomsk107 was used to create polycrystalline and bicrystal models containing general grain boundaries. OVITO108 was used to visualize and analyze the atomic structures.

MLIP training in concurrent learning

DeePMD-kit v2.2.8109 was used for learning the initial dataset and each concurrent learning flow. Here, we used the same framework and hyperparameters as in previous studies on DP construction for W-H binary systems using concurrent learning66. In other words, we used two-body embedding descriptors (se_e2_a) as DP descriptors. The cutoff radius was set to 6.5 Å, the configuration of embedding network (20, 40, 80) was used, and the number of axis neurons was set to 16. The following fitting net of deep neural network model in the training stage was used: the configuration of fitting net (240, 240, 240), initial learning rate 10−3, final learning rage 1.0 × 10−8, and training steps 800,000. The deep neural network architecture contains three hidden layers, each containing 240 neurons. The activation function was set in hyperbolic tangent form for each hidden layer.

Initial dataset

The six subsets included in the initial dataset, as shown in Table 1, were obtained using the following methods.

-

(1).

Equilibrated Fe with dilute H. 0-4 H atoms were randomly placed in the tetrahedral interstitial sites (TIS) of the 2 × 2 × 2 supercell of α-Fe. These atomic structures were optimized and five snapshots generated during the process were obtained uniformly and added to the dataset.

-

(2).

Perturbed Fe with dilute H. Based on the optimized structures in subset 1, strains and perturbations were performed. The applied strain ranges from −2.0% to +2.0%. The mean perturbation distance of atoms is set to 0.03 Å, and the mean perturbation fraction of cell vectors is set to 1.0%. The training data were obtained using single-point DFT calculations for these atomic structures.

-

(3).

Strained Fe with 1 H. A single H atom was placed in the TIS or octahedral interstitial site (OIS) of a 3 × 3 × 3 supercell of α-Fe. Hydrostatic or uniaxial strains were applied to these atoms. The strain was applied in the range of -4% to +4%. These atomic structures were optimized, and five snapshotsgenerated during the process were obtained for each structure and added to the dataset.

-

(4).

H-vacancy clusters. 0-6 H atoms were placed in the vicinity of a single vacancy in a 3 × 3 × 3 supercell of α-Fe. These atomic structures were optimized, and all the structures were obtained during relaxation and added to the dataset.

-

(5).

2H in neighboring TISs. Place one H atom in TIS in a 3 × 3 × 3 supercell of α-Fe, and place another H atom in nine different adjacent TIS positions. Optimize these atomic structures, obtain five snapshots for each structure generated during the process, and add them to the dataset.

-

(6).

Single H atom and H₂ molecules. Training data were obtained by single-point DFT calculations for a single hydrogen atom in vacuum and H₂ molecules with bond lengths ranging from 0.5 to 1.0 Å. For systems containing 4 or 8 H₂ molecules in a 5.0 Å × 5.0 Å × 5.0 Å region, AIMD calculations were performed at 300 K, and all obtained structures were added to the training data.

Exploration

The eight reference structures listed in Table 1 were used for the exploration. Molecular dynamics calculations were performed under different conditions (temperature and pressure) and ensembles (NVT and NPT), using interatomic potentials for reference structures to obtain candidate structures for labeling. Interatomic potentials were obtained from one of the four DPs obtained sequentially during the learning step. The atomic forces in each structure were calculated using the three other DPs. If the maximum deviation in atomic forces between the four DPs is higher than 0.10 eV Å−1 and lower than 0.25 eV Å−1, the structure is selected as a candidate structure for labeling.

The structures for exploration were set to cover all atomic environments related to hydrogen embrittlement of α-Fe. For this purpose, we added three reference structures (5)–(8) in Table 1 to the exploration structures used in previous studies of the W-H binary system66. It should be noted that the W-H DP was constructed for hydrogen blistering analysis and did not include learning data containing grain boundaries, which are particularly important in studies of hydrogen embrittlement in high-strength alloys.

-

(1).

Fe with dilute H. 0-4 H atoms were randomly placed in TISs in a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell of α-Fe. The applied strain ranges from −2.0% to +2.0%. The mean perturbation distance of atoms is set to 0.03 Å, and the mean perturbation fraction of cell vectors is set to 1.0%. The NPT ensemble was employed at pressures ranging from 0 to 5 GPa and temperatures ranging from 50 to 1630 K. For structures without H, the temperature ranged from 50 to 2535 K.

-

(2).

Fe with high concentration H. 0-4 H atoms were randomly placed in TISs in a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell of α-Fe. The applied strain ranges from −2.0% to +2.0%. The mean perturbation distance of atoms is set to 0.03 Å, and the mean perturbation fraction of cell vectors is set to 1.0%. The NPT ensemble was employed at pressures ranging from 0 to 5 GPa and temperatures ranging from 50 to 1630 K.

-

(3).

H atoms in vacancy. A 2 × 2 × 2 supercell of α-Fe with a single vacancy and 0 to 6 H atoms. The NPT ensemble was employed at pressures ranging from 0 to 5 GPa and temperatures ranging from 50 to 724 K.

-

(4).

H atoms on surface. hydrogen atoms Free surfaces with Miller indices of (111), (110), and (100), and surfaces with adsorption of 1–5 H atoms. The NVT ensemble was used. The temperature ranged from 50 to 724 K. For structures with one H atom, structural relaxation processes were also considered.

-

(5).

Generalized stacking faults with H atoms. (110) and (211) generalized stacking faults were considered. The structure without H atoms consists of 12 Fe atoms. Structures containing hydrogen consist of 48 Fe atoms and 1–4 H atoms. Hydrogen was randomly distributed in the vicinity of the generalized stacking faults. Structures with a maximum atomic displacement of 0.03 Å were also used as initial structures for exploration. An NVT ensemble was used, and the temperature was set in the range of 50–724 K.

-

(6).

Perturbed tilt grain boundaries with H atoms. Considering the cost of the DFT calculations in the labeling step, we considered <110> and <100> symmetric tilt grain boundaries consisting of up to 72 Fe atoms. Specifically, eight grain boundaries, Σ3(111), Σ3(112), Σ9(114), Σ9(221), Σ11(113), Σ11(332), Σ5(210), and Σ5(310), were selected. For the structures after relaxation of these grain boundaries, random lattice strains ranging from −5.0% to +5.0% were applied, and structures with atoms randomly displaced within a range of up to 0.5 Å were selected for exploration. Furthermore, structures with 1-5 H atoms randomly added near the centers of these grain boundaries were selected for exploration. Furthermore, based on these structures, we also selected structures with rigid displacements in the direction perpendicular to the grain boundaries in the range of 0.5 Å to 10 Å as structures for exploration. These structures were intended to sample atomic environments corresponding to systems with deformations added to general and symmetric tilt grain boundaries. An NVT ensemble was used, and the temperature was set in the range 50–724 K. Under these conditions, when the rigid-body displacement was small, the two shifted crystal grains combined during annealing and approached the grain boundary with uniaxial strain. By contrast, when the rigid-body displacement was large, the two shifted grains were maintained, resulting in an atomic environment corresponding to a fractured grain boundary.

-

(7).

Self-interstitial atom (\(\left\langle 111\right\rangle\), \(\left\langle 110\right\rangle\), \(\left\langle 100\right\rangle\) dumbbell) (SIA). Five types of self-interstitial atoms, dumbbell <110>, dumbbell <100>, tetrahedral, octahedral, and dumbbell <110>, dumbbell <100> configurations, were included in the α-Fe 2 × 2 × 2 supercell or 3 × 3 × 3 supercell. An NVT ensemble was used, and the temperature range was set 50 to 724 K.

-

(8).

H atoms in vacancy cluster. 2 × 2 × 2 supercells contain the most stable vacancy clusters consisting of two, three, or four vacancies. In addition, the 3 × 3 × 3 supercell contained the most stable small voids, consisting of eight vacancies. For the 2 × 2 × 2 supercells, 2–32 H atoms were randomly placed near the vacancy clusters. In the 3 × 3 × 3 supercells, up to 45 H atoms were randomly distributed near the small voids. An NVT ensemble was used at temperatures ranging from 50 to 724 K.

Training for the final MLIP

The BNNP was trained using n2p267 with some of the hyperparameters used in previous studies56 modified. An architecture with two hidden layers, each containing 15 neurons, was used. The activation function was set in the logistic form for both hidden layers.

We used 16 radial and 48 angular atomic center symmetry functions (ACSF) as descriptors, resulting in 1231 adjustable parameters (i.e., 1200 weights and 31 biases). The radial symmetry function is defined as follows:

where \({R}_{{ij}}\) is the atomic distance between atom \(j\) and central atom \(i\). The angular symmetry function is given by:

where \({\theta }_{{ijk}}\) is the angle enclosed by the vectors of \({R}_{{ij}}\) and \({R}_{{ik}}\) of two neighboring atoms \(j\) and \(k\), respectively. Both types of ACSF have a common function \({f}_{c}\) called the cutoff function, which is defined as follows:

In these equations, \({R}_{s}\), λ, and ξ are parameters, and the same values as those used in the previous study on Fe-H were used. For a specific list of values, please refer to the n2p2 input file provided in the Supplementary Data. The cutoff radius \({R}_{c}\) is 6.0 Å for Fe atoms and 3.6 Å for H atoms. The modification from the previous study56 is equivalent to the cutoff radius, which was set to 6.5 Å in previous studies, but we set it to 6.0 Å. This greatly improved the calculation speed while maintaining accuracy (see Supplementary Note 1).

Uniaxial tensile analysis of general grain boundaries with hydrogen segregation

As an application of the obtained MLIP, the effect of hydrogen segregation, depending on the bulk hydrogen concentration, on the deformation behavior of general grain boundaries was analyzed. First, a bicrystal grain boundary model including general grain boundaries was created. In a 10 nm × 10 nm × 20 nm supercell with periodic boundary conditions in the xy direction and a non-periodic z direction, crystal seeds were placed at positions z = 5.0 nm and 15.0 nm, and the initial structure of the bicrystal was created using the Voronoi tessellation method. The orientations of the two crystal grains were randomly assigned. This results in the formation of grain boundaries near z = 10.0 nm. In addition, periodic boundary conditions in the x-y direction resulted in the formation of two disjunction interfaces perpendicular to these grain boundaries. We removed one of the atoms located within a distance of 2.0 Å from each other near these grain boundaries and disjunction interfaces. Subsequently, the atomic positions of the structure were relaxed. In most cases, this relaxation eliminates dislocation surfaces, leaving only grain boundaries consisting of two random crystal orientations. This is because the two crystal grains that form the two dislocation surfaces perpendicular to the grain boundary have the same crystal orientation, and the z-direction is nonperiodic, allowing for relatively large relaxation. Even when the dislocation surfaces are eliminated, slight lattice defects may remain. However, in most cases, they are present only in small amounts at locations far from the grain boundaries, and their effects on the uniaxial tensile analysis of general grain boundaries with hydrogen segregation can be ignored. In addition, because the energy of the atoms is defined in MLIP, the grain boundary energy can be evaluated from the energy of the atoms near the grain boundaries. Using this method, we created six grain boundary models consisting of bicrystals with general grain boundaries.

Hydrogen is segregated into general grain boundaries in the grain boundary model. Here, the GCMC/MD hybrid method74 was used to reproduce the grain boundary segregation state according to the bulk hydrogen concentration (hydrogen charge condition) at 300 K. First, the relationship between the chemical potential and bulk hydrogen concentration at 300 K was determined using a bulk supercell that did not contain grain boundaries. We set the chemical potential to achieve the desired bulk hydrogen concentration, and applied the GCMC/MD hybrid method to a system containing grain boundaries to induce hydrogen segregation based on the bulk hydrogen concentration. Because the GCMC/MD hybrid method using MLIP is computationally expensive, hydrogen insertion in the grain boundary model was performed in the region 1.0 nm from the grain boundary center. The relationship between the chemical potential and the bulk hydrogen concentration was determined using the GCMC/MD method under NVT conditions with a bulk supercell of comparable size to the insertion region. The bulk supercell was created based on the equilibrium lattice constants at 300 K. Five hundred GCMC trials were conducted every 100 MD steps, which is the same condition used in previous studies56.

Uniaxial tensile calculations were performed using a general grain-boundary model with hydrogen segregation. The conditions were the same as those used in a recent uniaxial tensile analysis of symmetric tilt grain boundaries using EAM38. In other words, the atoms at the two ends of the grain boundary model in the tensile direction were fixed as a fixed layer, and strain was applied by moving them at a constant strain rate. The time step for the MD analysis was 1 fs, and the strain rate was set to 1 × 108 /s. In addition, to exclude surface effects, periodic boundary conditions were imposed in a direction parallel to the grain boundary, and the pressure was adjusted to zero during the uniaxial tensile tests. The temperature was set at 300 K.

Accuracy evaluation of MLIP for deformation and fracture behavior of general grain boundaries without hydrogen and with hydrogen segregation

To verify the calculation accuracy of the constructed MLIP for the deformation and fracture behaviors of general grain boundaries without hydrogen and with hydrogen segregation, an extrapolation grade based on the local atomic environment76 was used. The extrapolation grade is available in the MTP and is a method for numerically evaluating whether the atomic environment surrounding a given atom is within the interpolation or extrapolation region of the constructed MTP. Although the extrapolation grade was proposed as a method for active learning, it is also useful for evaluating the calculation accuracy of large-scale systems where direct comparison with DFT is difficult49,59,95. If the extrapolation grade for the target atom is 0–1, it is considered to be in the “interpolation” region where high accuracy can be expected; if it is 1–2, it is considered to be in the “accurate extrapolation” region; and if it is 2 or higher, it is considered to be in the “reliable extrapolation” region.

For this purpose, we train the MTP using a training dataset to construct the final MLIP. Training was performed using MLIP-376 with a level 22 MTP template and a cutoff distance of 6.5 Å. The RMSE of the MTP energy and atomic force for the entire training dataset were 6.27 meV/atom and 112.9 meV/Å, respectively. The RMSE for the energy was slightly larger than that for BNNP, whereas the RMSE for the atomic force was similar to that for BNNP.

Data availability

The potential and the n2p2 configuration files used for training the machine learning interatomic potential are publicly available on GitHub: https://github.com/KazumaIto0810/Fe-H_BNNP. All other relevant data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, K.I., upon reasonable request and with permission from Nippon Steel Corporation.

Code availability

The main codes utilized in this study—n2p2 (https://github.com/CompPhysVienna/n2p2)67, DeePMD-kit (https://github.com/deepmodeling/deepmd-kit)109, MLIP-376, LAMMPS106—are open-source and can be accessed online, with their licensing information and user manuals detailed in the respective references.

References

Yu, H. et al. Hydrogen embrittlement as a conspicuous material challenge─comprehensive review and future directions. Chem. Rev. 124, 6271–6392 (2024).

Meda, U. S., Bhat, N., Pandey, A., Subramanya, K. N. & Lourdu Antony Raj, M. A. Challenges associated with hydrogen storage systems due to the hydrogen embrittlement of high-strength steels. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48, 17894–17913 (2023).

Campari, A. et al. Lessons learned from HIAD 2.0: Inspection and maintenance to avoid hydrogen-induced material failures. Comput. Chem. Eng. 173, 108199 (2023).

Sun, B. et al. Current challenges and opportunities toward understanding hydrogen embrittlement mechanisms in advanced high-strength steels: a review. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 34, 741–754 (2021).

Neeraj, T., Srinivasan, R. & Li, J. Hydrogen embrittlement of ferritic steels: Oobservations on deformation microstructure, nanoscale dimples and failure by nanovoiding. Acta Mater. 60, 5160–5171 (2012).

Boot, T., Kömmelt, P., Hendrikx, R. W. A., Böttger, A. J. & Popovich, V. Effect of plastic deformation on the hydrogen embrittlement of ferritic high-strength steel. npj Mater. Degrad. 9, 39 (2025).

Zhang, B. et al. Improving the hydrogen embrittlement resistance by straining the ferrite/cementite interfaces. Acta Mater. 270, 119850 (2024).

Liu, P.-Y. et al. Engineering metal-carbide hydrogen traps in steels. Nat. Commun. 15, 724 (2024).

Lan, X., Okada, K., Ueji, R. & Shibata, A. Improving hydrogen embrittlement resistance in high-strength martensitic steels via thermomechanical processing. Scr. Mater. 264, 116711 (2025).

Okada, K. et al. Effect of carbon segregation at prior austenite grain boundary on hydrogen-related crack propagation behavior in 3Mn-0.2C martensitic steels. Acta Mater. 280, 120288 (2024).

Yoo, J. et al. Effects of solid solution and grain-boundary segregation of Mo on hydrogen embrittlement in 32MnB5 hot-stamping steels. Acta Mater. 207, 116661 (2021).

Omura, T. & Oyama, T. Effects of the addition of alloying elements on hydrogen diffusion and hydrogen embrittlement in martensitic steel. ISIJ Int 64, 620–629 (2024).

Takahashi, J., Kawakami, K. & Teramoto, S. Difference in hydrogen trapping behaviors between epsilon carbide and cementite in steels. Mater. Charact. 218, 114557 (2024).

Wada, K. et al. Hydrogen-induced degradation of SUS304 austenitic stainless steel at cryogenic temperatures. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 927, 147988 (2025).

Cho, H.-J., Cho, Y. & Kim, S.-J. Hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility of Cu bearing cost-effective austenitic stainless steels. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 60, 1–10 (2024).

San Marchi, C. et al. Effect of microstructural and environmental variables on ductility of austenitic stainless steels. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46, 12338–12347 (2021).

Khalid, H., Shunmugasamy, V. C., DeMott, R. W., Hattar, K. & Mansoor, B. Effect of grain size and precipitates on hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility of nickel alloy 718. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 55, 474–490 (2024).

Wada, K., Shibata, C., Enoki, H., Iijima, T. & Yamabe, J. Hydrogen-induced intergranular cracking of pure nickel under various strain rates and temperatures in gaseous hydrogen environment. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 873, 145040 (2023).

Ito, K., Yamamura, M., Omura, T., Yamabe, J. & Matsunaga, H. Effects of Cr, Mn, and Fe on the hydrogen solubility of Ni in high-pressure hydrogen environments and their electronic origins: an experimental and first-principles study. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 50, 148–164 (2024).

Shimizu, K. et al. Hydrogen embrittlement in Al–Zn–Mg alloys: semispontaneous decohesion of precipitates. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 109, 1421–1436 (2025).

Jiang, S. et al. Structurally complex phase engineering enables hydrogen-tolerant Al alloys. Nature 641, 358–364 (2025).

Zhao, H. et al. Hydrogen trapping and embrittlement in high-strength Al alloys. Nature 602, 437–441 (2022).

Zhu, Y. et al. Hydriding of titanium: recent trends and perspectives in advanced characterization and multiscale modeling. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 26, 101020 (2022).

Deconinck, L. et al. Hydrogen enhanced localised plasticity of single grain α titanium verified by in-situ hydrogen microcantilever bending. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.03.135 (2024).

Beachem, C. D. A new model for hydrogen-assisted cracking (hydrogen “embrittlement”). Metall. Trans. 3, 441–455 (1972).

Gerberich, W. W., Oriani, R. A., Lji, M. J., Chen, X. & Foecke, T. The necessity of both plasticity and brittleness in the fracture thresholds of iron. Philos. Mag. A 63, 363–376 (1991).

Nagumo, M. Hydrogen related failure of steels—a new aspect. Mater. Sci. Technol. 20, 940–950 (2004).

Lynch, S. P. A fractographic study of hydrogen-assisted cracking and liquid-metal embrittlement in nickel. J. Mater. Sci. 21, 692–704 (1986).

Lu, X., Ma, Y. & Wang, D. On the hydrogen embrittlement behavior of nickel-based alloys: alloys 718 and 725. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 792, 139785 (2020).

Seita, M., Hanson, J. P., Gradečak, S. & Demkowicz, M. J. The dual role of coherent twin boundaries in hydrogen embrittlement. Nat. Commun. 6, 6164 (2015).

Shibata, A. et al. Local crack arrestability and deformation microstructure evolution of hydrogen-related fracture in martensitic steel. Corros. Sci. 233, 112092 (2024).