Abstract

Ground-level ozone affects Earth’s climate and human health. The formation of ozone is a complex process, depending on both atmospheric chemical processes and meteorological factors. In this study, machine learning coupled with a structure mining analysis was applied to investigate the ozone formation mechanism in Tianjin, China. The results showed isoprene has the greatest individual impact on local ozone generation, which suggests the biogenic emission of vegetation contribute significantly to native ozone pollution. The interaction between isoprene and nitrogen oxides is the strongest among precursors, with an obvious antagonistic effect between them. Reducing active volatile organic compounds is more effective for mitigating ozone pollution. Visualized network diagram also clearly illustrated the impacts of multiple drivers on ozone formation: isoprene, temperature and nitrogen oxides were the key drivers among all the influencing factors, other drivers (such as relative humidity) could assist the key drivers to collaboratively enhance or suppress ozone formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

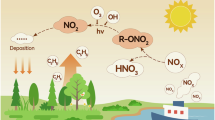

Ozone (O3) plays an important role in global public health and land ecosystem1,2. Long-term exposure to elevated concentrations of O3 has been link to negative health outcomes, such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, among others3,4. Studies have shown that fine particulate matter (PM2.5) concentrations in China have been reduced by 30–40% from 2013 to 2017, while ambient O3 concentrations have increased unexpectedly in many urban areas in China, since the implementation of the Air Pollution Prevention and Action Plan in 20135,6,7. The O3 annual average maximum 8 h-average 90-percentile value (M8A90) in China has increased by 28.8% in the past 7 years since 20138. Consequently, O3 pollution has become an emerging concern in China. Understanding the formation mechanism of O3 is crucial for effectively assessing and designing refined policies for O3 reduction in the future9,10.

A number of drivers are involved in the formation of O3, including precursors, chemistry process and meteorology10,11,12. All of these drivers increase the complexity of O3 generation mechanism. Nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are the main precursors of O313,14. The conversion from NO to NO2 will be accelerated in the presence of VOCs; and O3 will form by the photolysis of NO2 in the presence of O215,16,17. In addition, a higher fraction of light absorbing components in PM2.5 can enhance the reduction of O3 formation rates13,18,19. O3 formation is also affected by meteorological conditions such as temperature (T) and wind speed (WS). Meteorology not only affects emissions of NOx and VOCs, but also influences reaction rates that either produce or consume O320,21,22. Therefore, it is essential to examine the impact of various drivers on O3 generation, and the relationships among multiple drivers, to help developing corresponding regulatory strategy. However, existing studies lack consensus on the above issues, due largely to the complex and non-linear relationships among these drivers, and it’s difficult to quantitatively estimate the effects of above drivers on the formation of O3. In complex atmospheric environment, unfortunately, the conditions and influencing factors will be even more complicated.

Machine learning (ML) methods are data-driven, and can effectively establish the complex and non-linear relationships between input features and output predictor variables23,24,25. Recently, multiple ML methods such as random forest (RF), convolutional neural network (CNN) and artificial neural network (ANN) have been applied to predict air pollutant (O3, PM2.5, NOx, and NH3 et al.) concentrations and to analyze the causes of air pollution26,27,28,29. Studies have showed that the RF model coupled with some model-unrelated interpretation methods (such as partial dependence plots (PDP) approach), can specifically analyze the response relationship between features and the dependent variables30,31. However, the above methods do not attempt to examine the structure of the ML model itself, and do not account for the interactions among multiple features. Structure mining is a model-related interpretation method proposed by Paluszynska32. Based on the generation rule of ML methods (for instance, the decision tree of RF), structure mining allows further exploring the interactions between pairwise features (drivers on O3 formation). The internal operations of ML can be well visualized, which will clarify the relationship among multiple features. Therefore, ML coupled with structure mining method may have potential advantages in elucidating complicated issues involving multiple drivers, though this method is rarely applied in the field of atmospheric science, especially for investigating the causes of O3 pollution.

In the work, we coupled structure mining analysis and a ML method (RF), to reveal the effects of multiple drivers on O3 formation based on a multi-year dataset from Tianjin (an important city in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration of China which is polluted by O3). ML result identifies the most important drivers, while structure mining analysis explores the strength of interactions between paired drivers. Visualized network diagram clearly illustrated the most crucial key-drivers (isoprene, T and NOx in this work) among all potential drivers, and showed potential interactions between the key-drivers and other drivers. The visualized results prove that the ML coupled structure mining method will be a useful tool for clearly exploring the key issues for O3 formation, and for providing guidance for the precision control of O3.

Results and discussion

Overview of drivers on O3 formation from observed dataset

Hourly online variations of O3 and its influencing factors for multiple years (2017.10–2020.7) were collected in Tianjin, with monthly variation illustrated in Fig. 1. Numerous previous studies have proved that VOCs consumed during the transport from sources to observation sites play an important role for O3 generation3,33,34. Complex chemical reactions lead to highly reactive VOCs species being consumed to varying degrees from sources to the observation sites, which can lead to biases in studying the impact of VOC on O3. Thus, to account for such process, we used initial VOCs (fresh VOCs emitted from sources) obtained from simulations to compensate for VOC losses not included in observed data (more details on initial VOCs can be found in the Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Table 2). Overall, VOCs, NOx and PM2.5 concentrations showed obvious regular variation patterns, with lower levels in summer and higher in winter. O3 concentration exhibited a characteristic of lower levels in winter and higher in summer, mainly due to increased photochemistry in warmer months. Considering that different VOC species have different photochemical activities on O3 formation, monthly variations of four VOCs categories (alkanes, alkenes, alkynes, and aromatics) were also illustrated (Fig. 1b). VOCs compositions were not consistent among months though alkanes were generally the most abundant species. Besides, the variation of alkenes was similar to that of O3, implying that alkenes may be important for O3 generation. We also distinguished between biogenic and anthropogenic VOCs (Supplementary Fig. 9). The same variation of biological VOCs and O3 also suggests the important role of plant emissions. Among meteorological parameters, T and relative humidity (RH) were higher in summer and autumn, and lower in winter and spring. The mean wind direction (WD) was dominated by southeast winds (detailed descriptions of data were shown in Supplementary Table 1).

a Shows monthly variations of O3 (ppbv), PM2.5 (μg/m3) and NOx (ppbv). b Shows monthly variations of VOCs (ppbv) and four VOCs categories (alkanes, alkenes, alkynes, and aromatics). c Shows monthly variations of T (°C) and RH (%). d Shows monthly variations of solar radiation (SR, W/m2), wind speed (WS, m/s) and WD. Monthly variations showed similar trends for alkenes, temperature and O3, but opposite for NOx.

From the observations, we observed that the above drivers (especially alkenes, NOx, and T) had obvious similar or opposite variation characteristics as compared with O3. Therefore, there may exist a complex non-linear relationship between O3 and its drivers. Based on this assumption, a “data-driven” ML approach can be considered to reveal the effects of various drivers on O3 formation.

Effects of individual drivers on O3 formation

In order to illustrate, using visual network diagram, the effects of multiple drivers on O3, we need to first quantify the effects of individual drivers. A ML method called random forest (RF) was applied here to explore such individual effects. The selection process of the ML model is shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. In light of the previous work, the precursors (mainly VOCs and NOx) and meteorological conditions are usually considered as the main drivers for O3 formation6,13,28. Therefore, we selected the most important VOC species (top 10 VOCs calculated by ozone formation potential, OFP, see Supplementary Note. 4), NOx, meteorology conditions (T, RH, SR, WS, WD) and PM2.5 (the effects of secondary organic carbon (SOC), primary organic carbon (POC), particle surface area (PSA) were considered) as the variables for building the RF model (daytime dataset only, since O3 generation exclusively occurs during daytime). RF can provide an initial assessment of variable importance (namely the effects of individual drivers on O3 formation in this work) using increases in MSE increase and node purity35,36,37 (see Supplementary Note 3). Through importance analysis, we can preliminarily explore the impact of individual drivers.

The results of RF are shown in Fig. 2. Isoprene, as the dominant species of biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs), has the highest impact (21.09%), likely due to its high kinetic reactivity among alkene species. Previous studies have confirmed that isoprene has a high maximum incremental reactivity38 (as quantified by maximum incremental reactivity, MIR, reflecting the sensitive of O3 to VOCs emissions. The MIR of isoprene is 10.61, about 10 times that of some inactive alkanes). Other than isoprene, NOx had the secondary highest impact (10.83%) among all precursors. The photochemical reaction cycle among NO, NO2 and O3 is the basis of atmospheric photochemical process and the photolysis of NO2 is the main source of O3. Therefore, NOx can provide a substantial pool for O3. The coexistence of NO, NO2 and VOCs in the atmosphere can lead to photolysis production of O3 from NO2, under the presence of ultraviolet radiation (Eq. 1 and Eq. 2)5. As for meteorological factors, the most important driver was T (20.42%). Theoretically, high temperature directly enhances the photochemical reaction rate, resulting in high O3 production39. RH also has important impact (5.53%) among all meteorological conditions. It is worth noting that RH may have negative effects on the formation of O340,41 (some important negative effects may also be considered as important by variable importance analysis). Following RH are SR (2.62%), WS (2.11%) and WD (2.02%). Changes in RH and WD are often closely related to monsoons. When the East Asian summer monsoon arrives, the West Pacific subtropical high is strong, which will cause high temperature, low humidity, and little cloud in northern China, causing an increase in O3 concentration34,42. Higher SR will intensify photochemical reactions, subsequently increase O3 mass concentrations. WS significantly affect the diffusion or accumulation of pollutants, and O3 accumulation is easier under low wind speed.

In addition, in order to better investigate the impact of PM2.5 on O3 generation, we also considered the impact of SOC, POC and PSA (calculation method can be found in Supplementary Note 5) in RF calculations. It can be found that SOC has the greatest impact (7.79%), and there exists a competitive relationship between SOC and O3 due to their sharing of the same precursors3. The next driver was PSA (4.19%). A higher PSA will facilitate heterogeneous reactions on particle surface to generate NO3-, which will compete for NOx required for O3 generation11. Besides, the light absorption capacity of POC also affects the formation of O3. These result shows that the impact of particulate matter on O3 cannot be ignored. We also used other interpretable tools to verify the robustness of the importance of variables (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 7).

In above analysis, RF method quantified the effects of individual drivers on O3, though the direction of such impacts (positive or negative, or P/N) cannot be directly derived by RF. Understanding the P/N effects is helpful for gaining deep insights into relevant processes governing O3 formation. For this reason, we further explored P/N effects based on RF-PDP method (sensitivity curves of individual drivers) in the actual atmospheric environment. PDP curves can be obtained by separately controlling values of the specified drivers to change within a specific range, and averaging the corresponding changes of O3 concentrations predicted by the RF model. The curves of important drivers were presented in Fig. 3. Overall, among the precursors of O3, the majority of VOCs species showed P effects (especially alkenes which was dominated by isoprene, Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 3). Interestingly, as the concentrations of NOx increased, O3 decreased, indicating a N effect of NOx. Although NO2 can generate O3, excessive NOx would titrate O3 which led to the reduction of O3 concentration11,43,44. Moreover, based on Empirical Kinetics Modeling Approach (EKMA curve analysis, see Supplementary Fig. 2), the study region is located within VOC-limited regime45,46, which further confirms that excessive NOx will consume O3. In addition to precursors, among significant meteorological conditions, T shows obvious P effect, while RH posed a N effect. More details on the effects of individual drivers are provided in Supplementary Fig. 3. For further exploring the causes of severe O3 pollution, we also used the local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME) to explain individual samples with O3 concentration closed to the M8A90 (70.38 ppbv), which reflects the level of O3 pollution (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Figs. 4–5). We can detect that under extreme conditions, temperature plays an important role in O3 generation, and isoprene emitted by plants is also an important source of O3 generation. NOx and RH have side effects on O3 production.

a and b Show P effects of isoprene and T. c and d Show N effects of NOx and RH. e Shows effects of drivers as estimated by LIME when O3 concentration closed to the M8A9. When O3 pollution is severe, temperature and important active VOCs have a significant positive impact on O3 generation, while RH and NOx have an obvious negative impact.

Since the response of O3 to drivers may be different from season to season, we have divided the months from different seasons, trained RF models for each season and estimated feature importance of each driver. Also, PDP plots were also plotted to study the response of O3 concentration to drivers in each season. The results (Fig. 4) show that in spring, the impact of meteorological conditions is relatively large (especially T and RH). While in summer, the effect of SOC is important which mainly because meteorological conditions in summer are also conducive to the formation of secondary organic aerosols, which have same precursors as O3. Therefore, due to their similar changing trends, the impact of SOC measured by data-driven based ML method is significant. Drivers following SOC are RH and isoprene. In autumn, it is more influenced by T, closely followed by NOx. Winter is more affected by NOx. This is mainly due to the higher concentration of NOx in winter compared to other seasons, which seriously affects the generation of O3. The RF-PDP results show that O3 concentration tends to increase with the increase of the majority of VOCs species which was dominated by isoprene in all seasons, especially in summer and autumn (the increase relatively small in winter when the concentration of isoprene is low), and decrease with the increase of NOx in all seasons. In addition to these precursors, the important meteorological conditions T and RH responded approximately the same across seasons, with T showing a positive impact on O3 generation and RH a negative.

Interactions of paired drivers

Above analysis of drivers on O3 by RF briefly explained their individual effects. The interactions among multiple drivers also play crucial roles on O3 formation, due to the fact that O3 is affected by multiple complex drivers. Therefore, the potential interactions among pairs of drivers need to be investigated. Although the RF model cannot be used to directly investigate such interactions between paired drivers, exploring the structure of decision trees in RF can help extracting information on the paired drivers. The main way of such structure mining analysis is based on the concept of mean minimal depth (MMD, the mean distance from the depth of one driver to the root of the tree, Fig. 5a). For a single driver, it’s considered to be more important to the generation of O3, if its MMD is shallower. Based on the concept of MMD, we can further quantify potential interactions between paired drivers by exploring their conditional minimal depth (CMD, the mean distance between two drivers in trees, Fig. 5b). Similar to MMD, the interactions between paired drivers will be considered stronger, if their CMD is shallower.

a and c Show the schematic diagram of mean minimal depth (MMD) and conditional minimal depth (CMD) in the RF model; A represents an important driver such as isoprene, B represents another important driver such as NOx. b Shows MMD for different drivers. Isoprene, T and NOx were closer to the root of the trees than the other drivers. d Provides CMD for the 20 strongest interactions. Isoprene-T, T-NOx, isoprene-NOx, isoprene-SOC were paired drivers with the strongest interactions.

The results of MMD and CMD by structure mining were shown in Fig. 5c and Fig. 5d. For MMD, isoprene, T and NOx were closer to the root among all the drivers, indicating they were the key drivers. Isoprene had the lowest MMD (1.24); T and NOx also had low MMD (below 2). On the other hand, MMDs of other drivers were higher than 2.5, suggesting they were not as important for the formation of O3 as the three key drivers. Figure 5d showed CMD values for 20 most important interactions. We observed that isoprene-T had the shallowest CMD values, indicating that the interactions between isoprene and T had the most important impact on the formation of O3. Higher temperature will generally promote the emission of biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs, mainly isoprene), and accelerate photochemical reactions that produce O333. Paired drivers following isoprene-T were T-NOx, isoprene-NOx, and isoprene-SOC, etc. Previous researches confirmed that the potential connections between the above paired drivers can substantially determine O3 formation. The interaction between paired T-NOx is also important because temperature can determine the reaction paths of NOx11,47. Isoprene-NOx had the shallowest CMD values among precursors. Previous studies have also suggested that the presence of isoprene will affect the “NOx cycle”, which will produce O311. The strong interactions between isoprene-SOC suggest that isoprene is also the precursor of secondary organic aerosol which can accelerate the formation of SOC3,48,49. In order to further display the interactions, we used RF-3dPDP to estimate how the O3 was influenced by the synergy of paired drivers. RF-3dPDP can strip other feature parameters and specifically analyze the effects of paired feature parameters on the model. The strongest four pairs of interactions screened out by CMD were further displayed through RF-3dPDP, and the results were shown in Fig. 6. The results provided us with more insights into the impact of paired drivers on O3 formation and some most effective pathways to reduce the O3 concentration based on paired drivers. We can more clearly detect that reducing isoprene is more effective for local O3 reduction than reducing NOx (Fig. 6c); The presence of isoprene and high temperature simultaneously lead to an increase in O350.

Visualization of network diagram

Visual diagram can clearly illustrate network relationships among all drivers and O3, especially under complex ambient conditions. Hence, we built the network diagram among multiple drivers using visualization tools based on CMD obtained from structure mining. We firstly screened 54 paired driver interactions as determined by the aforementioned CMD metrics (CMD < 4). Then, we further calculated interaction coefficients (IC), which are important visualization parameters for building network diagram. The calculation formula and details of IC are shown in Methods (for IC, a higher value indicates stronger interaction of the paired drivers, Supplementary Table 3). Finally, we created the network diagram (Fig. 7) based on the IC values of paired drivers, using visualization tool Gephi.

a and b Show the schematic diagram of interaction coefficient (IC); A represents an important driver such as isoprene, B represents another important driver such as NOx. c Shows network diagram for drivers of O3; Isoprene, T and NOx are key drivers; other assistant drivers are less important, though they collaborate with key drivers to promote O3 formation.

The advantage of network diagram is that it can intuitively display key drivers (placed in network centers with deep colors) among all influencing factors, and illustrate the strengths of interactions between drivers (line thickness). From the network diagram, we can clearly identify isoprene, T and NOx as key drivers (they have the shallowest MMD and interact frequently with other drivers), indicating that they are the most critical drivers for O3 formation. Although other drivers are less important than the key drivers, they do collaborate with the key drivers to promote O3 formation. In this paper, we call these factors assistant drivers. Both the interactions between key drivers, as well as between key drivers and assistant-drivers, cannot be ignored. Among the most important key driver, isoprene maintains strong interactions with multiple drivers (including other key drivers NOx and T; assistant drivers such as RH, SOC). As a crucial precursor of O3, it is inextricably linked with NOx. As with other alkenes, the reaction of isoprene with OH proceeds at nearly the limit of gas kinetic and almost entirely by addition. Rich organic peroxy radical (RO2) react with NO to generate O3; a small yet important, branch yields organic nitrate and, thereby, removes NOx from the atmosphere51,52. The simultaneously presence of isoprene and NOx might slow down the growth of O3, compared with one critical driver alone due to the antagonistic effects between them. Similarly, there also exists antagonistic effects between isoprene and RH. In addition, isoprene and T have an obvious additive effect (both drivers play positive roles), both high concentrations of isoprene and high temperature promote O3 pollution. For another important center-driver, NOx has strong interaction with T and RH. The results were in agreement with previous studies in which meteorological drivers mainly influence reactive nitrogen (Nr)’s reaction pathways11. Higher temperature and lower RH enhanced photochemical pathway’s reaction rate43. For another meteorological key driver T, RH is its main assistant drivers. While under sunny summer conditions, high temperature and low relative humidity always occur at the same time at the observation site, which leads to the frequent occurrence of O3 pollution in summer.

Conclusion and implications

The complicated non-linear relationships between O3 and its many drivers (mainly precursors and meteorological parameters) make it difficult to explore O3 formation mechanism. In this study, we used machine learning coupled structure mining method to study the causes of O3 and established a network diagram that clearly illustrated the effects of multiply drivers on O3. The established RF model has favorable performance and the results well indicated the individual impact of drivers on O3. Among all precursors, active VOCs especially isoprene, are the most important since the sampling site is located in suburbs with high reactivity of alkenes. Among all meteorological factors, temperature plays a dominant role, mainly because higher temperature enhances photochemical pathway’s reaction rate. RF-PDP further shows the P/N effects of drivers. The majority of VOCs species show P effects. Interestingly, NOx exhibits a N effect because the study region is located in VOC-limited regime. It also suggested that controlling the generation of most VOCs (especially isoprene) is more effective than controlling NOx at the research location. However, it does not mean that NOx control is not important. ML also shows that NOx is a key driver. Based on the analysis of theoretical modelling, it is also necessary to control NOx as a long-term strategy.

Rather than being driven by one key driver alone, O3 formation is affected by multiple intertwined drivers. The interactions between paired drivers were further quantified by structure mining method which was helpful for policy-makers to develop target solutions. Among all paired driver groups, isoprene-T had high interaction strength which highlighted its importance. Isoprene and NOx have the highest interaction between precursors. In addition, the network diagram clearly illustrated these key interactions and drivers. The results are consistent with those found in previous theoretical analysis. Meteorological drivers dominate the Nr reaction pathways. The presence of active VOCs will affect atmospheric “NOx cycle”, which will produce O3. But the simultaneous presence of isoprene and NOx might slow down the growth of O3, compared with the presence of one critical driver alone.

The application of ML techniques in atmospheric environment research field is still in its infancy, but ML methods are expected to provide further insights into the pollution formation process. In the ambient environment, air pollution is the result of multiple drivers. However, it’s difficult for traditional laboratory studies or models that were based on chemical mechanisms to fully account for the wide breadth of conditions during the formation of pollution, and it is also exceedingly difficult to analyze the network effects among multiple factors. Machine learning and structure mining technology could at least partially overcome the above shortcomings. Starting from the structure of ML method and visualizing its internal operation, we were able to identify key drivers and their assistant drivers from their complex interactions, and established a network diagram, which provide deeper and clearer insights into the causes of O3 pollution. Our study provides a framework for building robust models and for identifying the critical drivers of O3 among multiple potential precursors and the influence of meteorological conditions. We believe that the visualization techniques of ML can play a more important role in the field of multi-factor studies such as carbon reduction, human disease or anticancer drug research.

Methods

Sampling and monitoring

The sampling campaign was conducted at the campus of Nankai University (38°59′ N, 117°19′ E) in the Jinnan district of Tianjin, from October 2017 to July 2020. It is a typical rural area, surrounded by park and several universities, and located far from major highways and high traffic zones with relatively small population density. Hourly concentrations of VOCs, NOx, O3, and PM2.5 were measured at 5 m above ground level by multiple instruments. Concentrations of fifty-four VOCs species, and chemical components of particles were also measured. Meteorological parameters, including T, RH, WS, WD, and SR, were monitored by an automatic meteorological observation system (WS600-UMB, LUFFT). More details about the observations can be found in the Supplementary Note 1.

Random forest

RF is an ensemble supervised learning method, which can be regarded as an extension of decision tree53,54,55. In this work, RF prediction models were constructed using the “randomForest” package in R programming language (R 4.1.2). The RF model used 500 random decision trees and selected 1/3 random features at each node. The R2 (coefficient of determination) and RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) values between predictions and observations were calculated to evaluate model performance, and the calculation formula can be found in Supplementary Note 3. RF provide two tools to estimate the importance of individual features, mean-square error (MSE) increase and node purity increase56,57. Here, in order to improve the robustness of the importance, we convert MSE increase and node purity into percentages, and calculated their average value as the ultimate variable importance. The RF modeling in this study included multiple years (2017.10–2020.7) daytime dataset to examine the individual effect of drivers on O3. A total of 3614 valid samples were acquired during this period (including 2529 training samples and 1085 testing samples). We included some explanations on RF and other relevant interpretable tools in Supplementary Note 3.

RF-PDP method

Sensitivity curve of individual driver can be further explored by RF-PDP method which allows us to study P/N effects. PDP58,59 can isolate other factors, and specifically estimate the relationship between individual or paired feature parameters and predictor variables. Here, the sensitivity analysis of individual or paired drivers on O3 were calculated by RF-PDP or RF-3dPDP method, which was implemented by R package “PDP”. The calculation function of RF-PDP was shown in Eq. 3.

where \({{\mbox{f}}}\left({{{\mbox{X}}}}_{{{\mbox{S}}}}\right)\) stands for the prediction value of random forest model when with inputs of \({{{\mbox{X}}}}_{{{\mbox{S}}}}\); \({{\mbox{RF}}}\) stands for a trained random forest model; \({{{\mbox{X}}}}_{{{\mbox{S}}}}\) is the feature selected to calculate the partial dependence function in the random forest model; \({{{\mbox{X}}}}_{{{\mbox{C}}}}^{({{\mbox{i}}})}\) stands for the features unselected in the random forest model which are input into the model as a fixed value; n is the number of samples.

Structure mining method

Understanding the internal structure of RF can reveal and quantify the relationships among multiple features. However, RF is a “black box” model, which cannot directly reveal the relationships among various features in its internal structure. Hence, we utilized the structure mining method to mine and analyze the structure of the “tree” of RF for quantifying the interactions between paired drivers, based on the concept of mean minimal depth (MMD). For an individual variable Xi, the minimal depth measures the distance (measured by the number of edges in the decision tree) from the root of the entire tree to the closest root of a maximal A-subtree, and the mean minimal depth is the average of the minimal depths of the variable Xi across all trees32. If the MMD of variable Xi is shallow, it indicates that Xi has a better segmentation effect on the data, implying that it is more important to the predictor variable. More importantly, conditional minimal depth (CMD, based on MMD) between paired drivers can also be utilized to calculate their interaction strength60, which measures the mean minimal depth of variable Xj in the maximal Xi-subtree (Xi represents another variable different from Xj). Similarly, a shallow CMD between Xi-Xj indicate that their interaction is stronger. The MMD and CMD of features were initially calculated using the “randomForestExplainer” package in R programming language (R 4.1.2).

Network diagram by visualization method

Network diagram can clearly show the interactions among multiple features, which can visualize the internal structure of the RF model. The relationship between paired features (visualization values) are the basis for visualizing the network diagram. Here, we calculated interaction coefficient (\({{{\mbox{IC}}}}_{{{\mbox{A}}}-{{\mbox{B}}}}\), significant visualization value) by integrating the CMD of paired features obtained from structure mining, and the frequency factor (occurrence of the interaction of B and the maximal A-subtree among the trees). Frequency factor reflects the closeness of paired feature, and combining with CMD can improve the physical meaning and stability of the interaction coefficient. The specific calculation formula of ICA-B was provided in Eq. 4. A greater ICA-B suggests that the interaction between feature A and B is stronger.

Where ICA-B is interaction coefficient of A and B, which represents the interaction strength between A and B, \({{{\mbox{O}}}}_{{{\mbox{A}}}-{{\mbox{B}}}}\) is the occurrence of the interaction of B and the maximal A-subtree among the trees, \({{{\mbox{N}}}}_{{{\mbox{tree}}}}\) is the total number of trees in the forest, \({{{{{\rm{CM}}}}}}{{{\mbox{D}}}}_{{{\mbox{A}}}-{{\mbox{B}}}}\) is the mean minimal depth of B in the maximal A-subtree, that is, the conditional minimal depth.

Finally, we import the visualization data based on IC into the visualization model (Gephi 0.9.2), to establish the network diagram.

Data availability

The data included in this study could be downloaded at https://figshare.com/ (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22012421.v1). Additional data that support the plots and the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (G.S.) upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code to carry out the current analyses is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Feng, Z. et al. Economic losses due to ozone impacts on human health, forest productivity and crop yield across China. Environ. Int. 131, 104966 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Mitigating China’s ozone pollution with more balanced health benefits. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 7647–7656 (2022).

Wang, F. et al. Machine learning and theoretical analysis release the non-linear relationship among ozone, secondary organic aerosol and volatile organic compounds. J. Environ. Sci. 114, 75–84 (2022).

Jaffe, D. Relationship between surface and free tropospheric ozone in the western U.S. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 432–438 (2011).

Wang, T. et al. Ozone pollution in China: A review of concentrations, meteorological influences, chemical precursors, and effects. Sci. Total. Environ. 575, 1582–1596 (2017).

Tan, Z. et al. Exploring ozone pollution in Chengdu, southwestern China: a case study from radical chemistry to O3-VOC-NOx sensitivity. Sci. Total. Environ. 636, 775–786 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Contrasting trends of PM2.5 and surface-ozone concentrations in China from 2013 to 2017. Natl. Sci. Rev. 7, 1331–1339 (2020).

Ye, L., Lu, P., Peng, Y., Li, J. & Huang, H. Impact of NOx and NH3 addition on toluene oxidation over MnOx-CeO2 catalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 416, 125939 (2021).

Ding, D., Xing, J., Wang, S., Chang, X. & Hao, J. Impacts of emissions and meteorological changes on China’s ozone pollution in the warm seasons of 2013 and 2017. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 13, 76 (2019).

Zhang, K. et al. Precursors and potential sources of ground-level ozone in suburban Shanghai. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 14, 92 (2020).

Wang, F. et al. Drivers of PM2.5-O3 co-pollution: from the perspective of reactive nitrogen conversion pathways in atmospheric nitrogen cycling. Sci. Bull. 67, 1833–1836 (2022).

Li, K. et al. A two-pollutant strategy for improving ozone and particulate air quality in China. Nat. Geosci. 12, 906–910 (2019).

Li, C., Zhu, Q., Jin, X. & Cohen, R. C. Elucidating contributions of anthropogenic volatile organic compounds and particulate matter to ozone trends over China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 12906–12916 (2022).

Chen, H. et al. Characteristics of ozone and particles in the near-surface atmosphere in the urban area of the Yangtze River Delta, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 4153–4175 (2019).

Buysse, C. E., Kaulfus, A., Nair, U. & Jaffe, D. A. Relationships between particulate matter, ozone, and nitrogen oxides during urban smoke events in the western US. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 12519–12528 (2019).

Vermeuel, M. P. et al. Sensitivity of ozone production to NOx and VOC along the Lake Michigan coastline. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 124, 10989–11006 (2019).

Lu, K. et al. Exploring atmospheric free-radical chemistry in China: the self-cleansing capacity and the formation of secondary air pollution. Natl. Sci. Rev. 6, 579–594 (2019).

Kang, M., Zhang, J., Zhang, H. & Ying, Q. On the relevancy of observed ozone increase during COVID-19 lockdown to summertime ozone and PM2.5 control policies in China. Environ. Sci. Tech. Let. 8, 289–294 (2021).

Shao, M. et al. Quantifying the role of PM2.5 dropping in variations of ground-level ozone: Inter-comparison between Beijing and Los Angeles. Sci. Total. Environ. 788, 147712 (2021).

Jin, X., Fiore, A., Boersma, K. F., Smedt, I. & Valin, L. Inferring changes in summertime surface ozone-NOx-VOC Chemistry over U.S. urban areas from two decades of satellite and ground-based observations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 6518–6529 (2020).

Almaraz, M. et al. Agriculture is a major source of NOx Pollution in California. Sci. Adv. 4, 3477 (2018).

Wang, P. et al. Is atmospheric oxidation capacity better in indicating tropospheric O3 formation? Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 16, 65 (2022).

Chen, J., Yin, J., Zang, L., Zhang, T. & Zhao, M. Stacking machine learning model for estimating hourly PM2.5 in China based on Himawari 8 aerosol optical depth data. Sci. Total. Environ. 697, 134021 (2019).

Yu, F., Wei, C., Deng, P., Peng, T. & Hu, X. Deep exploration of random forest model boosts the interpretability of machine learning studies of complicated immune responses and lung burden of nanoparticles. Sci. Adv. 7, 4130 (2021).

Irrgang, C. et al. Towards neural Earth system modelling by integrating artificial intelligence in Earth system science. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 667–674 (2021).

Ma, R. et al. Random forest model based fine scale spatiotemporal O3 trends in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region in China, 2010 to 2017. Environ. Pollut. 276, 116635 (2021).

Gao, J. et al. Roles of RH, aerosol pH and sources in concentrations of secondary inorganic aerosols, during different pollution periods. Atmos. Environ. 241, 117770 (2020).

Ren, X., Mi, Z., Cai, T., Nolte, C. G. & Georgopoulos, P. G. Flexible bayesian ensemble machine learning framework for predicting local ozone concentrations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 3871–3883 (2022).

Xing, J. et al. Deep Learning for Prediction of the Air Quality Response to Emission Changes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 8589–8600 (2020).

Gu, J., Yang, B., Brauer, M. & Zhang, K. M. Enhancing the evaluation and interpretability of data-driven air quality models. Atmos. Environ. 246, 118125 (2021).

Wei, N. et al. Machine learning predicts emissions of brake wear PM2.5: model construction and interpretation. Environ. Sci. Tech. Let. 9, 352–358 (2022).

Paluszynska, A. Structure mining and knowledge extraction from random forest with applications to the cancer genome atlas project, Master’s thesis. (University of Warsaw, Warsaw, 2017).

Wang, Z. et al. Implications for ozone control by understanding the survivor bias in observed ozone-volatile organic compounds system. npj. Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 39 (2022).

Zhan, J. L. et al. Ozone formation sensitivity study using machine learning coupled with the reactivity of volatile organic compound species. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 15, 1511–1520 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Machine learning combined with the PMF model reveal the synergistic effects of sources and meteorological factors on PM2.5 pollution. Environ. Res. 212, 113322 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Interaction Patterns between Climate Action and Air Cleaning in China: a two-way evaluation based on an ensemble learning approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 9291–9301 (2022).

Ban, Z., Hu, X. & Li, J. Tipping points of marine phytoplankton to multiple environmental stressors. Nat. Clim. Change. 12, 1045–1051 (2022).

Carter, W. P. L. Development of a condensed SAPRC-07 chemical mechanism. Atmos. Environ. 44, 5336–5345 (2010).

Xue, Y. G. et al. High impact of vehicle and solvent emission on the ambient volatile organic compounds in a major city of northwest China. Chinese. Chem. Lett. 33, 2753–2756 (2022).

Hou, P. & Wu, S. Long-term changes in extreme air pollution meteorology and the implications for air quality. Sci. Rep. 6, 23792 (2016).

Ma, S., Shao, M., Zhang, Y., Dai, Q. & Xie, M. Sensitivity of PM2.5 and O3 pollution episodes to meteorological factors over the North China Plain. Sci. Total. Environ. 792, 148474 (2021).

Lu, X. et al. Severe surface ozone pollution in China: a global perspective. Environ. Sci. Tech. Let. 5, 487–494 (2018).

Li, Q. et al. “New” reactive nitrogen chemistry reshapes the relationship of ozone to Its precursors. Environ. Sci. Technol. Let. 52, 2810–2818 (2018).

Tan, Z. et al. Explicit diagnosis of the local ozone production rate and the ozone-NOx-VOC sensitivities. Sci. Bull. 63, 1067–1076 (2018).

Wang, T. et al. Ground-level ozone pollution in China: a synthesis of recent findings on influencing factors and impacts. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 063003 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Sensitivities of ozone air pollution in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei area to local and upwind precursor emissions using adjoint modeling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 5752–5762 (2021).

Cao, Y., Ma, Q., Chu, B. & He, H. Homogeneous and heterogeneous photolysis of nitrate in the atmosphere: state of the science, current research needs, and future prospects. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 17, 48 (2022).

Agarwal, R. & Aggarwal, S. G. A year-round study of ambient gaseous pollutants, their atmospheric chemistry and role in secondary particle formation at an urban site in Delhi. Atmos. Environ. 295, 119557 (2023).

Zhao, D., Chen, H., Sun, X. & Shi, Z. Spatio-temporal variation of PM2.5 pollution and its relationship with meteorology among five megacities in China. Aerosol. Air. Qual. Res. 18, 2318–2331 (2018).

Porter, W. C. & Heald, C. L. The mechanisms and meteorological drivers of the summertime ozone-temperature relationship. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 13367–13381 (2019).

Teng, A. P., Crounse, J. D. & Wennberg, P. O. Isoprene peroxy radical dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 5367–5377 (2017).

Pinho, P., Pio, C. & Jenkin, M. Evaluation of isoprene degradation in the detailed tropospheric chemical mechanism, MCM v3, using environmental chamber data. Atmos. Environ. 39, 1303–1322 (2005).

Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn 45, 5–32 (2001).

Ishwaran, H. & Malley, J. D. Synthetic learning machines. Biodata. Min. 7, 28 (2014).

Scornet, E. Random forests and kernel methods. Ieee. T. Inform. Theory. 62, 1485–1500 (2016).

Strobl, C., Boulesteix, A. L., Kneib, T., Augustin, T. & Zeileis, A. Conditional variable importance for random forests. Bmc. Bioinform. 9, 307 (2008).

Ziegler, A. & Konig, I. R. Mining data with random forests: current options for real-world applications. Wires. Data. Min. Knowl. 4, 55–63 (2014).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29, 1189–1232 (2001).

Goldstein, A., Kapelner, A., Bleich, J. & Pitkin, E. Peeking inside the black box: visualiTzing statistical learning with plots of individual conditional expectation. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 24, 44–65 (2015).

Gibson, P. B. et al. Training machine learning models on climate model output yields skillful interpretable seasonal precipitation forecasts. Commun. Earth. Environ. 2, 159 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3703400), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42077191), Blue Sky Foundation, Tianjin Science and Technology Plan Project (18PTZWHZ00120), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (63213072 and 63213074).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.S. designed the study. Z.W., F.W. and W.L. conducted the data analyses. D.L. and Z.W. interpreted the data. Z.W. and W.L. performed the model simulation. B.X. supported machine learning methods. Writing was led by G.S. and H.X. with substantial input from H.Y., Y.F., J.L., and Y.W. All authors contributed to the paper and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Keding Lu, Neelesh Rampal and Nadia Colombi for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Mengze Li, Clare Davis and Aliénor Lavergne. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, H., Yu, H., Xu, B. et al. Machine learning coupled structure mining method visualizes the impact of multiple drivers on ambient ozone. Commun Earth Environ 4, 265 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00932-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00932-0

This article is cited by

-

Assessment model of ozone pollution based on SHAP-IPSO-CNN and its application

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Mechanisms behind the rapid rise of extreme heat discomfort days in South China

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)

-

Natural and anthropogenic imprints on seasonal river water quality trends across China

npj Clean Water (2025)

-

Multi-routine-data driven spatio-temporal short-term predictions for surface ozone in China

Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health (2025)