Abstract

Marine extremes are recognized to cause severe ecosystem and socioeconomic impacts. However, in polar regions, such as the Barents Sea, the driving mechanisms of these extremes remain poorly understood and require careful consideration of the observed long-term ocean warming. Here we show that on short time scales of a few days, marine heatwaves and marine cold spells are dynamically driven by a dipole atmospheric circulation pattern between the Nordic Seas and the Barents Sea. Importantly, the dipole’s eastern component determines anomalies in shortwave radiation and latent heat fluxes. On interannual time scales, both changes in ocean heat supply and persistent atmospheric patterns can support severe marine extremes. We apply conventional marine heatwave detection methodology to OISSTv2 data, for the period of 1982–2021, and combine the analysis with ERA5 data to identify drivers. The ocean-atmosphere interplay across scales provides valuable information that can be integrated into fisheries and ecosystem management frameworks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Marine heatwaves (MHWs) and their counterpart, marine cold spells (MCSs), are prolonged extremes of marine temperatures that persist for several days or more1. Although both MHWs and MCSs are important climatic phenomena, the research and environmental concerns have been predominantly focused on MHWs due to their severe ecological and socioeconomic impacts2,3,4,5. For instance, MHWs have been found to devastate local ecosystems such as corals, kelp forests, and seagrass meadows2,3,4, leading to shifts in marine life and the depletion and tropicalization of fish communities2,5. The sixth assessment report (AR6) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change recognized MHWs as significant climatic extremes, acknowledging their potentially devastating impacts on local environments and subsequent socioeconomic consequences6. This highlights the need to improve our understanding of MHWs and their driving mechanisms, particularly at higher latitudes, where our knowledge is still limited and mean temperatures are rising rapidly7.

Recent studies have reported a significant increase in the duration and frequency of MHWs in the Arctic8,9, including the Barents Sea (BS)10. Human-induced warming, along with decreasing sea-ice concentration, is evidently a major factor exposing the Arctic marine climate to such extreme conditions in the long-term11. However, the physical mechanisms driving changes in MHWs on interannual and longer timescales are still not fully understood. In general, MHWs are modulated by both local (e.g., ocean advection, eddy heat flux, and air-sea heat flux) and remote physical processes (e.g., climate modes of variability) acting on a range of temporal and spatial scales4,12. On global scales, the main drivers of MHWs are usually reduced latent heat loss and increased solar irradiance, which is especially true for summer from the subtropics to high latitudes13. For the Arctic, Hu et al.8 found that the variability of MHWs can be attributed to changes in stratification, indicating an important role for the vertical structure of the ocean. Holbrook et al.14 identify teleconnections to the Southern Annular Mode and the Dipole Mode Index as the main driver of MHWs in the Arctic Ocean and the BS, respectively (see their supplementary fig. 3 and 4). Mohamed et al.10 report that MHW occurrence and characteristics in the BS are partly connected to another atmospheric teleconnection pattern, the East Atlantic pattern. Although these results may have been influenced by the background anthropogenic warming (fixed baseline) that must be removed to properly isolate the relevant physical drivers at play12.

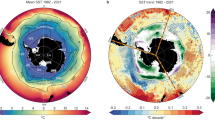

In this study, we focus on the BS (Fig. 1), a semi-enclosed shelf sea with openings toward the Nordic Seas (Norwegian Sea) and the Arctic Ocean (Eurasian Basin). As Europe’s northernmost shelf sea, the BS also hosts part of the Arctic’s sea-ice edge, which expands and retreats annually throughout the BS. The sea-ice conditions are, however, changing since the BS has experienced exceptional warming over the past four decades (Fig. 2, see also Isaksen et al.15). The climate variability of the BS is furthermore characterized by a range of scales, spanning from interannual to multidecadal16,17,18. Levitus et al.16, for instance, revealed that the BS temperature variability during the 20th century closely aligns with the Atlantic multidecadal variability, i.e. the averaged sea-surface temperature in the wider North Atlantic (see also Drinkwater et al.19), which suggests a connection between ocean circulation and BS ocean heat content (HC). Carton et al.17. focused on interannual to decadal temperature anomalies and were able to attribute anomalous warm and cold periods in the BS to advection from the Norwegian Sea. They also confirmed, using a heat budget analysis, that the local net surface air-sea heat flux anomalies are too small to explain interannual-to-decadal heat storage anomalies. Lien et al.20. furthermore identified the role of wind-induced Ekman-transport off the northern BS shelf, related to the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), to regulate the throughflow of the Atlantic Water into the Arctic. In the present work, we follow the approach by Carton et al.17 to identify the ocean’s role for MHWs and MCSs in the southeastern BS.

a Bathymetry40 of the study area, with (gray shading) the boundaries of the Barents Sea Large Marine Ecosystem39 and (white shading) the area discarded due to partial sea ice cover above 15% sea ice concentration. Additionally, the Barents Sea Opening (BSO; black dotted line) and the region of the southeastern Barents Sea (seBS; the solid black line) that is used for further analysis related to the composites in Fig. 5. The southeastern Barents Sea is also marked in b and c (solid black lines). b Time-mean sea surface temperatures. c Annual mean trend of sea surface temperatures. d Monthly sea-ice fraction of the full Barents Sea Large Marine Ecosystem (blue) and daily sea surface temperatures from July to October (orange) for the ice-free regions (<15% sea-ice concentration) as shown in a–c; the shading represents the percentage of data (e.g., 50% data implies data between the 25th and 75th percentiles of the time series distribution).

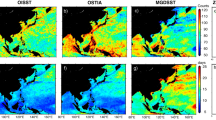

a Annual means of the summer (Jul–Oct) ocean heat content22 of the full water column of the southeastern Barents Sea, the calculations follow those outlined in Carton et al.17. Dashed colored lines indicate half a standard deviation from the mean; colored areas indicate the periods where the time series has a clear tendency to be below or above the mean. b Percentage of time of summer (Jul–Oct) sea surface temperatures associated with marine heatwaves (red) or marine cold spells (blue). The shading indicates the severeness of the marine extreme, following the categorization scheme of Hobday et al.21, recapped within the methods section; the trend of the time series was removed, using the trend of 1981–2021, and the climatology reference period is 1982–2021 (see methods section for details). The marine extreme days are evaluated for the summer (Jul–Oct) mean sea surface temperature time series of the southeastern Barents Sea (annual summer, Jul–Oct, means shown as solid line in dark purple; right-hand side axis). The rank correlation coefficients (Kendall) between the annual summer mean SSTa (Jul–Oct) and either the MHWs, or the MCSs are, respectively, τ = 0.66 (p < 0.01) and τ = 0.69 (p < 0.01). If applying a 3-year rolling mean to the annual time series, correlations become τ = 0.6 (p < 0.01) and τ = 0.71 (p < 0.01) for MHWs and MCSs respectively.

In the following, we analyze MHWs and MCSs using the definition by Hobday et al. 1. and Holbrook et al.21. We identify MHWs and MCSs within the MHW framework using surface temperatures (SST) from the NOAA OI SST V2 High Resolution Dataset. Since the MHW framework is not valid in mixed state conditions, we exclude sea-ice from our analysis. Here, limiting our analysis to the summer months (Jul–Oct; Fig. 1d) maximizes the area that can be investigated within the BS (see methods). Sea-ice is identified from the same dataset as the SST, which provides ice-concentration data. We use an SST time series constructed by spatially averaging over a confined region in the southeastern BS, a region that appears particularly sensitive to marine extremes. We continue by analyzing and comparing the MHW and MCS results on interannual time scales to a heat content analysis following the methods outlined in Carton et al.17 using the IAP ocean heat content dataset22. Our calculations use both a fixed and a linearly shifting baseline (see Amaya et al.23 for a discussion of the two baselines). Finally, we connect the identified MHWs and MCSs to atmospheric drivers on shorter timescales of a few days, drivers directly linked to strengthening of these extremes.

Results

We start with the fixed baseline referenced time series of MHWs and MCSs (suppl. Figure 1), which is dominated by the climate change signal, and resulted in a noticeable increase in the HC of the southeastern BS (Fig. 2a). The HC is anomalously low until 2003–2004 and shifts into a high HC regime thereafter. This is roughly consistent with temperature measurements from the Kola section16. Analysis of MHWs in the southeastern BS reveals that more than 50% of our summer time series in 7 of the years of the last decade (2011–2021) falls within the definition of MHWs (suppl. Figure 1). Three of these summers are classified to 100% as being in the MHW state, i.e., every single summer day being exceptionally hot. In contrast, MCSs (blue) seemingly disappeared after 2010, a clear indicator of a shift in the mean temperatures. MHWs further show another local maximum between 2004 and 2008, a period previously claimed to mark a regime shift10. The results presented by Mohamed et al.10, however, are relative to a fixed baseline in a region with strong trends (reaching beyond 1 degree per decade; Fig. 1c). The effects of neglecting trends are discussed by Amaya et al.23. where it is argued that results based on a fixed baseline should not be referred to as MHWs. We present both the fixed baseline (suppl. Fig. 1) and a shifting baseline (Fig. 2b) and analyze, unlike Mohamed et al.10, the MHW drivers (approximately) isolated from the signal of climate change.

Evaluating MHWs and MCSs relative to a shifting baseline (Fig. 2b) highlights the variability against a mean state that is approximately shifting with climate change and multidecadal variability (the latter is unresolved by the data record, however, the closely tied Atlantic Multidecadal Variability (AMV) is known to exhibit a positive trend over the satellite era24). Figure 2b shows qualitatively the goodness of the linear fit, through relative proportions of MHWs and MCSs, a linearly shifting baseline proves to be reasonable. The MHW and MCS activity still shows exceptional years, like the 2013 and 2016 MHWs, but suppress years that are only warm compared to retrospective climate references (e.g., the first 30 years of the satellite era compared to today). In Fig. 3, the results, based on the shifting baseline, are shown spatially for all grid points in the BS Large Marine Ecosystem individually, summarized as summer means for each year between 1982 and 2021. Along the path of Atlantic Water in the Nordic Seas, Carton et al.17. revealed multi-year thermal reversals: cold periods in the 1980s/late 1990s and warm periods in the early 1990s/since 2000. Our results show that the most intense MHWs and MCSs are observed in the southeastern BS, most notable in 2013 and 2016 (Fig. 3). The 1983–1986 and 2011–2018 periods are predominantly characterized by MHWs, while the 1993–1997 and 2006–2010 are mainly associated with MCSs. 1998, 2002, and 2003 are observed to include both MHWs and MCSs. Only few years exhibited MCSs in the BS Opening and MHWs the interior BS (e.g., 2012), while the opposite is more common (e.g., 1998, 1999, 2002, 2003). Several periods show a degree of persistence (e.g., MCSs in the eastern BS from 1996 to 1999), this could be an indicator of the importance of preconditioning or the importance of persistent climate modes. Speculatively, for example multi-year tendencies in the phase of the NAO or the oceanic circulation of the Nordic Seas. However, time scales exceeding 3 years are not further investigated. The spatial patterns suggest that MHWs occurring in the vicinity of the BS Opening may be connected to anomalously warm periods in the eastern Nordic Seas, as occurred during the 2002–2006 and 2012–2016 periods (see Fig. 4 in Carton et al.17 and Asbjørnsen et al.25), and possibly further amplified by the atmosphere, as will be examined next.

Summer (Sep–Oct) means of the intensity of marine heatwaves (red) and marine cold spells (blue) relative to local linearly shifting baselines for all years from 1982 to 2021. The summer means are calculated from the cumulative intensities relative to the thresholds, but only presented qualitatively (color-saturation means that on average there is a minimum of 1 °C of excess heat per day). Individual patterns for each major MHW event are shown in supplementary Fig. 7 and compared to their fixed baseline complements.

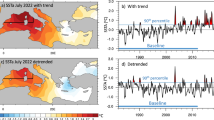

Panel a, b show heat fluxes calculated following the methodology by Carton et al.17; Each variable is calculated for the southeastern Barents Sea and averaged for each year’s summer (Jul–Oct) and additionally smoothed using a 5-year rolling mean. The colored dashed lines are half a standard deviation for each individual time series, and the colored areas indicate exceedance of that threshold, either upward or downward. a Anomalies of the time derivative of ocean heat content (HCt; solid line) and net surface air-sea heat fluxes (Qnet; dashed line). b Anomalies of the residual of the time derivative of the ocean heat content (HCt) and the surface heat fluxes (Qnet), representing the ocean’s local heat convergence. In gray, the marine heatwave coverage (solid) and marine cold spell coverage (dashed). c Shown are normalized 3-year rolling means of: (blue, dashed) the residual heat flux seen in b; (black, solid) the joint coverage of marine heatwaves and marine cold spells, the sum of the two gray lines in b, relative to the linearly shifting baseline (Fig. 2b); (green, dash-dotted) the NAO index; (orange, dotted) the east-west pressure gradient ΔP between the Barents Sea and the Nordic Seas, positive values indicate continental and Atlantic air, and negative values Arctic air inflows (see Fig. 5a, d); and (black, dash-plus) the sum of the east-west pressure gradient and the residual heat flux. The correlations to the joint marine extreme coverage metric are: r = 0.48 (p < 0.01) for the residual heat flux; r = 0.32 for the NAO (p < 0.05); r = 0.54 (p < 0.01) for the pressure gradient; and r = 0.66 (p < 0.01) for the combined effect of the east-west pressure gradient and the residual heat flux.

Figure 4a shows the temporal evolution of the summer ocean heat content tendency (HCt) and summer net surface air-sea heat flux (Qnet), presented as three-year rolling means (see supplementary Fig. 2 for the power spectral density of the anomalies of HC and SST). Both HCt and Qnet show multi-year variability, HCt exhibits three notable negative spikes in 1993, 2002, and 2020 and a positive event in 2005, but most notably a positive period from 2013 to 2017. Qnet shows a strong positive peak in 1987, but then only weaker ones in, for example 2005 and 2017, anomalous negative events are found in a period from 1990 to 1996, and a shorter event in 2014-2015. Figure 4b shows the three-year rolling mean of the residual heat flux, calculated itself as the difference between HCt and Qnet. The residual heat flux is an estimate of all oceanic transport components into the study area, sometimes referred to as ocean heat convergence. The residual heat flux responds to, in particular, the Qnet peak in 1987 and the HCt event of 2020, resulting in anomalously negative events, i.e., ocean heat divergence. After that, aside of a few minor events, only 2015 stands out as a strong, and lasting, positive anomaly in the residual heat flux (Fig. 4b). The panel further shows the 3-year rolling means of MHW and MCS coverage in the southeastern BS for reference. The residual heat flux shows a relationship with the averaged MHWs and MCSs on decadal time scales, with a downward trend for 1983–2003, a cold period up to 2012, and a strong positive trend in 2010–2018 followed by a downturn thereafter.

Figure 4c shows 3-year rolling means of the joint MHW and MCS coverage (black, solid), the NAO index (green), the residual heat flux (blue), the east-west pressure gradient between the BS and the Nordic Seas (orange), and the joint effect of the residual heat flux and the east-west pressure gradient (black, dashed). An east-west pressure gradient was identified as a potential proxy and driver for MHWs and MCSs based on the analysis hereafter (Fig. 5 and Suppl. Fig. 3). While we will see reasonable success using the east-west pressure gradient, we like to emphasize that it is a rather simple approach. Other metrics could yield better results, most notably atmospheric blocking which was shown to be associated with increased solar irradiance26, a metric most important on annual time scales for the development of marine extremes (suppl. Figure 4). On longer time scales (Fig. 4c), we see that the combined effect (r = 0.66, p < 0.01) of the residual heat flux (r = 0.48, p < 0.01) and the east-west pressure gradient (r = 0.54, p < 0.01) is a good indicator for the joint coverage of MHWs and MCSs (for MHWs and MCSs individually, the pressure gradient is still significantly correlated at p < 0.01 with Kendall correlations of τ=0.39 and τ=−0.35 for MHW and MCS coverage respectively; the combined effect too is still significant at p < 0.01 but lowers the correlation to τ=0.3 and τ=−0.32 for MHW and MCS respectively; the individual components of the combined effect, pressure gradient and residual heat flux, are not significantly correlated with another; the NAO and residual heat flux are not significant). Note that we only compare variability here due to the implications of Elzahaby et al.27. for our heat content analysis. The most prominent deviation between the joint coverage index and the joint driver index is found in the late 90 s. In particular, 1998 and 1999, two years which exhibited the strongest solar irradiation deficit of the entire satellite era in the period leading up to summer (Jan-Jun; suppl. Figure 5b). Further, the late 90th were preceded by a strong decrease in heat content in the southeastern BS since 1995, potentially suppressing the development of MHWs. The pressure gradient, noticeably positive during the late 90 s (Fig. 4c), may also wrongly include the driving mechanisms for the eastern Nordic Seas, which exhibited substantial MHW activity in 1998 and sporadic in 1999 (suppl. Mov. 1). We conclude that on interannual time scales, the east-west pressure gradient and the local ocean heat convergence together hold relevant predictive power for the development of MHWs and MCSs in the southeastern BS (on annual time scales, solar irradiation and the NAO are more important; suppl. Figure 4). A closer inspection of the summer-means (Jul-Oct) and leading season means (Jan–Jun) show a particular difference between 2016 and the other strong marine heatwave years, in particular 2013 (Suppl. Fig. 5). In 2016 the net radiation, sensible heat, and longwave radiation were high in the summer-mean, while leading up to summer, sensible heat fluxes exhibited the strongest positive anomaly on record. In contrast, 1990, 2004, and 2013, all exhibited strong anomalies in solar irradiance and ocean heat convergence. 2013 here is special, within 2013 both the solar irradiance and the ocean heat convergence were the highest on record (1990 being similar in solar irradiance). 2013 further exhibited the largest negative anomalies on record in sensible heat fluxes, longwave radiation, and further, exceptional negative anomalies in sensible heat fluxes, resulting in a record low net heat flux. The season leading up to the summer of 2013 is marked by again very strong solar irradiance, only second to 1990 within the satellite record. The fingerprint of this pattern can also be identified in Fig. 4c when comparing the rolling means of the residual heat flux and the pressure gradient. We note that 2013 exhibited strong MHW activity around the Norwegian coast from the Lofoten into the BS already early in that year (suppl. Mov. 1). We conclude from these findings that the 2013 MHW in the southeastern BS was strongly influenced by heat transports from the earlier MHWs to the west. While the 2016 MHW was mostly forced locally from the atmosphere in the southeastern BS itself.

All panels show composite means satisfying (1) the presence of an MHW or MCS relative to a linearly shifting baseline (1981–2021; Fig. 2b); the reference time series (Fig. 2b) is a spatial average of the southeastern Barents Sea (dotted dark gray and white line). (2) The temperature tendency of the SST anomalies (see methods section), a–c positive for MHWs; d–f negative for MCSs. The panel columns show from left to right anomalies of (left; a and d) mean sea level pressure (MSLP); (center; b, e) 2-meter air temperature (T2M); (right; c, f) net surface air-sea heat flux (Qnet). Gray hatches in each panel indicate statistical significance levels, with no hatches drawn where the highest level of significance occurs (p < 0.005). The complement of these composites (i.e., rising and falling temperatures outside their respective extremes) are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

The final analysis (Fig. 5) targets drivers on time scales shorter than the length of MHWs and MCSs (hereafter simply short time scales; average duration of 4 days, see Suppl. Fig. 6). This analysis is also done using the shifting baseline instead of the fixed baseline. Using the shifting baseline is an approach to highlight the component of the MHWs and MCSs that are not explained by gradual changes of the mean temperatures23, for example as expected from climate change. In Fig. 5, composite means of anomalies of MSLP, T2M, and the Qnet are shown. The resulting mean patterns show consistency across the three variables, for example during MHWs (Fig. 5a–c), temperature increases are driven by a high-pressure system, with anomalous positive air temperatures and downward air-sea heat flux. Patterns of MCSs strengthening (Fig. 5d–f) exhibit an inverse relationship to those of MHW strengthening. More precise, MSLP (Fig. 5a, d) shows high (low) pressure in the eastern BS and low (high) pressure above the Nordic Seas for MHWs (MCSs); T2M (Fig. 5b, e) exhibits high (low) anomalies above the eastern and southern BS; finally, Qnet (Fig. 5c, f) too follows the general tendency with positive (negative) anomalies for MHWs (MCSs), however, Qnet largest anomalies are in the central southern BS, along the region where the pressure field indicates southerly (northerly) winds. Of the four components of Qnet, three are of similar magnitude (suppl. Fig. 7). (1) Solar radiation is highest near the central area of the pressure high and is the dominant driver in the central to eastern region of the MHW (MCS). (2) Latent heat flux is the second most important, with strong anomalies on the edges of the MHW (MCS) regions, in the larger area around the BS Opening. (3) Finally, sensible heat flux is very similar to latent heat flux in its locations and only slightly lower in magnitude. The fact that sensible heat fluxes are this important here is a distinguishing characteristic compared to mid to lower latitude MWHs where usually latent heat and solar radiation are the only relevant terms28,29; the final component, the long-wave radiation, is the weakest of the four, with slight tendencies to oppose the other components, at least in the central areas of the MHW and MCS region. The minimal role of long-wave radiation in the context of MHWs is consistent with findings by Schlegel et al.29.

Complementary analysis of wind fields at 1000 hPa (Suppl. Fig. 8) corroborates our findings from the surface pressure field anomalies (Fig. 5a, d). Southerly winds are the dominant source of air for MHW strengthening phases, and northerlies for MCS strengthening. Focusing on MHWs, we see that the winds are going northward along the Norwegian coastline, however, within the BS they instead come directly from the continent. The continental winds carry warm air into the BS, a defining difference between warming within MHWs (Fig. 5b) and warming outside MHWs (Suppl. Fig. 3b). The winds seem also weaker along the coastlines, however, not statistically significant (suppl. Fig. 8a). Nonetheless, the warm, weak winds drive positive anomalies in surface sensible and latent heat fluxes. For MHWs, the winds play an important supporting role during the development phase, however, solar irradiation is the dominant driver (see Suppl. Fig. 4, 9, and suppl. Mov. 1). The oceanic circulation may partly be derived from the wind field, with Ekman transport perpendicular to the wind direction. The climatological wind direction (south-westerlies along the Norwegian coast and north-easterlies in much of the BS Opening; arrow colors in suppl. Fig. 8) indicate Ekman transports into the BS along the Norwegian coast and outwards in much of the BS Opening. During MHWs, the southerly winds would drive inward (into the BS) Ekman transport long the whole length of the BS Opening and vice versa for MCSs. We need to be cautious however, with the composite mean wind directions, for example during MHW strengthening, south of Svalbard, the wind speeds are significantly stronger compared to the reference, the composite mean winds are weak nonetheless (suppl. Fig. 8a). This likely means that the wind direction is very variable and not weak, an ambiguity present in composite means of vector quantities. In contrast, the winds and wind speed during MCS strengthening both are strong, or stronger than normal (suppl. Fig. 8b). This indicates that the northerlies across the BS are a robust feature of MCSs, leading to Ekman transport pushing water out of the BS and potentially to upwelling along the coast of Novaya Zemlya archipelago separating the BS and the Kara Sea. Composites of surface ocean currents itself show a convincing pattern, with currents strengthened in the Nordic Seas and along the Norwegian coast into the BS, and weakened in the BS during MHWs, and vice versa for MCSs (suppl. Fig. 10). The ocean current composites come, however, with a strong caveat, since the time series begins in 1993, two important early MHWs (1984, 1990) are missing from the composite. Further, the statistical significance is limited to many small areas, instead of a coherent large scale pattern. Nonetheless, the surface currents composites strongly suggest that an enhanced (suppressed) Nordic Sea circulation is associated with MHWs (MCSs) and that the topographically aligned BS circulation enhances too during MHWs, but is largely replaced by southward currents during MCSs.

The composites highlight clearly the patterns of atmospheric forcing during the strengthening of MHWs and MCSs. In comparison to Mohamed et al.10, magnitudes of our atmospheric drivers and patterns of MHWs are twice as large. We believe that, due to the applied method of averaging across the whole summer, their actual driver’s signal is washed out, resulting in the vast under-estimation of, for example, the center of the high pressure system over the Kara Sea. Furthermore, the shape and main gradient do not align with our results, as they find another weak high pressure system in the Nordic Seas. This is likely the imprint of transient high pressure systems passing through the BS that drive the anomalously long MHW in 2016. Ultimately, our analysis revealed the presence of high pressure systems in the eastern BS and over the Kara Sea as the main driver of MHWs. The identified pressure fields and resulting wind patterns suggest an influx of warm and moist Atlantic air toward the BS, but mostly weak winds from the continent carrying warm air masses. The central area of the southeastern BS region is, however, dominated by solar irradiance (suppl. Fig. 9a). MHWs (MCSs) are thus amplified on timescales of a few days by a dipole pattern consisting of a high-pressure (low-pressure) anomaly to the east of the BS and a low-pressure (high-pressure) anomaly over the Nordic Seas, bringing warm (cold) Atlantic (Arctic) air to the region and amplifying the local heat fluxes (Fig. 6).

a Marine heatwaves with strengthened pressure gradient relative to the mean pressure field. The pressure gradient leads to anomalous winds (red arrows) from the south, bringing Atlantic and continental air into the Barents Sea. The air-sea heat flux anomalies are increased downward for the larger Barents Sea area and above the adjacent Nordic Seas regions, resulting in strong oceanic heat gain. b Marine cold spells with reversed zonal pressure gradient and anomalous winds directly from the Arctic, bringing dry and cold Arctic air. The heat flux anomalies are strongly negative in the southern Barents Sea and lead to oceanic heat loss.

Discussion

In this study, the temporal evolution of MHWs and MCSs was analyzed for the ice-free BS and their driving processes examined on different time scales. On shorter time scales, the investigation showed atmospheric conditions to modulate the intensity of SSTs during, in particular, MHW events. While on interannual time scales, the role of atmosphere and ocean in driving MHWs and MCSs on these time scales has been seen.

We anticipate that changes of the HC are reflected in the mean SSTs and subsequently are important preconditioning for MHWs and MCSs. The presented heat budget analysis17 supports our hypothesis that the HC and its temporal change HCt both have a relationship with MHWs and MCSs. We note, however, that a heat budget analysis, as presented here, cannot accurately attribute the role of the atmosphere compared to the ocean in the context of MHWs or MCSs27. Mohamed et al.10 attribute the long term changes to initial surface heat flux changes, which through the SST-ice feedback lead to more open water and more heat uptake. They further point out that the increased advection of Atlantic water into the BS drives the long-term trends within the BS.

On short time scales of a few days, we reveal that strong anomalous atmospheric pressure patterns and associated heat fluxes drive MHWs and MCSs (Fig. 6) in the southeastern BS. MHWs are strengthened by high pressure systems to the east of the BS associated with anomalous irradiation, warm air, and weak southerly, Atlantic and continental origin winds. MCSs are strengthened through a strong zonal pressure gradient across the BS that leads to cold Arctic air flowing southward across the BS. Both atmospheric patterns are accompanied by corresponding anomalies in all components of the net surface air-sea heat flux (Qnet; Fig. 5c, f), but particularly in shortwave radiation, followed by latent heat and sensible heat flux (Suppl. Fig. 4, 9, and Suppl. Mov. 1). The relative strength of solar radiation and latent heat are expected, as they are often identified as dominant drivers28,29. However, the relative strength of the sensible heat term is, in many parts of the world ocean, not found to be a main driver of MHWs29,30 and can therefore be seen as a distinctive characteristic of the BS. Still, solar irradiance anomalies are sizably larger compared to all other heat flux terms, making cloud cover one of the most important indicators for marine extremes in the summer BS (Suppl. Fig. 4 and suppl. Mov. 1). The large scale pressure pattern further is linked to Ekman transports and surface ocean currents in the BS and the whole Nordic Seas. Ekman transports, inferred from the wind field, align well with the pressure system, driving warm Atlantic waters into the BS during MHWs and cold Arctic waters during MCSs. Note, however, that during MHWs the wind speeds, and subsequently the Ekman transports, are generally weak. Finally, the surface currents exhibit similar tendencies, thus the oceanic transport origins align well with water masses associated with the respective characteristic of the marine extreme, warm Atlantic water flowing up the Norwegian Atlantic Front Current for MHWs, and Arctic, ice-edge waters for MCSs.

The distinctiveness with which the atmospheric patterns are identified here is, to the best of our knowledge, novel for the BS. Previous studies have only shown long term averages for individual years10, these averages results in weak and indistinct patterns, since they combine the onset, decline, strengthening, and weakening phases of MHWs and MCSs into a single metric. The strength of our study lies in the fact that the presented patterns are not specific to a single event; instead, they characterize multiple events across the satellite era, all directly linked to the strengthening of MHWs and MCSs.

Future analysis in the context of MHWs and MCSs in the BS could estimate climate change and multidecadal variability from models31,32 or use non-stationary estimates of the baselines33 for better estimates of MHWs and MCSs in a rapidly changing climate. Beyond that, detailed analysis of the evolution of individual MHWs and MCSs like the 2013 and 2016 MHWs is very promising to reveal more about the sensitivity of the BS to climate change and to reveal differences of MHW drivers between these exceptional years. Finally, a relevant definition of MCSs for temperatures near freezing needs to be discussed within the community.

Methods

MHWs and MCSs are determined using the widely adopted method presented in Hobday et al.1 and Holbrook et al.21. Defining parameters are largely kept at the default, as we aim for comparability with other studies rather than to answer specific habitat questions. We use the 90th percentile as the threshold for extremes; 5 days as the minimum length of an extreme event; and we allow up to 2-day gaps within an extreme event. In contrast to the original algorithm, we use a cubic spline to estimate the mean seasonal cycle. The advantages of splines over moving averages for smoothing are better control of the smoothness characteristics and defined properties for extrapolation.

Holbrook et al.21 define the severity of MHWs in four categories: moderate, strong, severe, and extreme. The definition takes the local variability into account, to make dynamically separate regions better comparable. A common normalization is achieved through the division of the MHW intensity by the magnitude of the difference between seasonal cycle and percentile threshold. For example, strong MHWs, category 2, are those MHWs that lie between the percentile threshold and the sum of the percentile threshold and two times the difference between the percentile threshold and the seasonal cycle.

For the calculation of MHWs and MCSs, we utilize the daily NOAA OI SST v2 high-resolution dataset containing sea surface temperatures (SST) and sea ice concentration34. The spatial resolution of the dataset is 0.25 degrees on both latitude and longitude. The local linear trends are calculated from data between 1 September 1981 and 1 September 2021. The summer MHWs are calculated between 1 July 1982 and 31 October 2021.

We exclude most sea-ice conditions and maximize the sea-ice-free surface area of the BS, we limit our analysis to summer, 1 July to 31 October. The constraint is applied spatially to exclude areas that are at any time throughout the summer time-series covered by more than 15% sea ice concentration. Through this filter, we ensure physical consistency within our dataset. Including below-sea-ice temperatures, provided by the NOAA OI SST v2 high-resolution dataset, impacts the calculation of the seasonal cycle and trends, leading to erroneous results.

Systematic variability is removed from the daily SST data by subtracting the mean and a smoothed daily climatology. The mean and climatology are based on (a) the reference period (1982–1997), commonly referred to as a fixed baseline. The period of 1982–1997 is chosen since it is an early part of the SST record with little to no trends. And (b) the whole data set linearly detrended with the trend calculated from the period 1 September 1981 to 1 September 2021, this approach is commonly identified as one of the shifting baselines. The smoothing of the climatology is done using a cubic spline fit with a smoothing coefficient s = 10 and s = 5 for the fixed baseline reference period and the detrended time series respectively for the 90th percentile of the seasonal cycle and s = s/4 for the mean seasonal cycle. We extrapolate the smoothed seasonal cycle to match the input data through the use of the same splines.

The presented heat budget analysis17 uses the IAP global ocean heat content (HC) gridded product at 1° × 1° horizontal resolution dataset22 to estimate the effects of the oceanic heat transports into the southeastern BS. The HC is available in various depth integrals, for our study a depth large enough to capture the full HC down to the sea floor is used.

For the southeastern BS, net surface air-sea heat flux (Qnet) from the ERA5 reanalysis product35 are used. The ERA5 heat fluxes are defined positive downwards (heat gain of the ocean) and consist of short-wave radiative, long-wave radiative, sensible, and latent heat fluxes. With the goal to isolate the ocean’s component of the heat fluxes during MHWs and MCSs, first Qnet is subtracted from the time derivative of the HC (HCt), the residual of this calculation is an estimate of the ocean’s local heat convergence. In our calculation, this residual heat flux represents the oceanic heat fluxes in and out of the southeastern BS. Due to the depth choice of the HC, processes which influence the residual heat flux are dominantly advective heat fluxes. Our calculations follow closely the methods described in Carton et al.17, and we refer to them for further details.

We further analyze additional atmospheric variables from the ERA5 reanalysis product in the context of drivers for marine extremes, those are mean sea level pressure (MSLP) and 2-meter air temperature (T2M). Together with Qnet, these three are used in a composite analysis36. The data is prepared by removing mean, trend, and climatology. The calculation of the climatology is slightly simplified, compared to the SST data, by using a moving average with a window half width of 17 days instead of a cubic spline. This simplification is not expected to have a noticeable impact on the results. By expanding the annual cycle with itself at each end, the moving average could be performed on the data without extrapolation. The mean trends are calculated in the period from 1 September 1981 to 1 September 2021. A residual mean is subtracted. The resulting anomalies are then used for the same summer months as the SST data, i.e., based on sea ice cover in the study region, however, not spatially constrained by sea ice.

The composite means are constructed based on two criteria, (1) the presence of MHWs or MCSs, and (2) the temperature tendency, whether temperature anomalies are rising or falling. The temperature tendencies are calculated using the average temperatures of the southeastern BS. Estimation of the temperature tendency use a rolling linear regression \(s({t}_{i})={({X}^{T}X)}^{-1}{X}^{T}y\), with \(X={({t}_{i-(n-1)/2},...,{t}_{i},...,{t}_{i+(n-1)/2})}^{T}\) and \(y={({SS}{T}_{i-(n-1)/2},...,{SS}{T}_{i},...,{SS}{T}_{i+(n-1)/2})}^{T}\) with a window size of n = 5 days37. Identification of drivers using this method has the potential to estimate future likelihoods of MHW and MCS events. Ultimately, the time series of the atmospheric variables are then decomposed based on those conditionals. The final step is to time-average the sub-selected data to obtain the composite mean patterns.

Data availability

This study is based on publically available datasets: (1) NOAA OI SST V2 High Resolution Dataset34 sea surface temperatures and sea ice concentration are provided by the NOAA PSL, Boulder, Colorado, USA, and distributed via their website at https://psl.noaa.gov. (2) ERA535 hourly data of mean sea level pressure, 2 meter air temperature, short-wave radiative heat flux, long-wave radiative heat flux, latent heat flux, and sensible heat flux can be found at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu (Accessed on 11 March 2022). (3) ERA5 hourly data38 of 1000 hPa wind speed from Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Biavati, G., Horányi, A., Muñoz Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Rozum, I., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Dee, D., Thépaut, J-N. (2023): ERA5 hourly data on pressure levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS), DOI: 10.24381/cds.bd0915c6 (Accessed on 18 November 2023) via https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu. (4) IAP global ocean heat content22 can be found at http://www.ocean.iap.ac.cn. (5) Large Marine Ecosystems39 can be found at https://lmehub.net. (6) GEBCO 2020 Grid40 bathymetry can be found at https://www.gebco.net. (7) Globcurrent41 ocean surface currents can be found at https://data.marine.copernicus.eu (Accessed on 3 April 2024). (8) NOAA Interpolated Outgoing Longwave Radiation (OLR)42 can be found at https://psl.noaa.gov (Accessed on 16 November 2023). (9) The North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) index and the East Atlantic Pattern (EAP) index can be found through the Climate Prediction Center (CPC) at https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/.

Code availability

The code to calculate MHWs and MCSs is available at https://github.com/ecjoliver/marineHeatWaves. Minor modifications to the original code https://github.com/ecjoliver/marineHeatWaves are published here https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12583978 together with the code to calculate the temperature tendencies.

References

Hobday, A. J. et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr. 141, 227–238 (2016).

Wernberg, T. et al. An extreme climatic event alters marine ecosystem structure in a global biodiversity hotspot. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 78–82 (2013).

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. Longer and more frequent marine heatwaves over the past century. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03732-9 (2018).

Holbrook, N. J. et al. Keeping pace with marine heatwaves, Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0068-4.

Eriksen, E. et al. The Record-Warm Barents Sea and 0-Group Fish Response to Abnormal Conditions. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 338 (2020).

IPCC, The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed. Cambridge University Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157964.

Rantanen, M. et al. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979, Commun. Earth Environ., vol. 3, no. Aug. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00498-3.

Hu, S., Zhang, L. & Qian, S. Marine heatwaves in the arctic region: variation in different Ice Covers. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, 16 (2020).

Huang, B. et al. Prolonged marine heatwaves in the Arctic: 1982−2020. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, 24 (2021).

Mohamed, B., Nilsen, F. & Skogseth, R. Marine Heatwaves Characteristics in the Barents Sea Based on High Resolution Satellite Data (1982–2020). Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 821646 (2022).

Frölicher, T. L., Fischer, E. M. & Gruber, N. Marine heatwaves under global warming. Nature 560, 360–364 (2018).

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. Marine Heatwaves, Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci., 2020, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-032720-095144.

Vogt, L., Burger, F. A., Griffies, S. M. & Frölicher, T. L. Local Drivers of Marine Heatwaves: A Global Analysis With an Earth System Model, Front. Clim. 4, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2022.847995.

Holbrook, N. J. et al. A global assessment of marine heatwaves and their drivers, Nat. Commun., 2019, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10206-z.

Isaksen, K. et al. Exceptional warming over the Barents area, Sci. Rep., vol. 12, no. Jun. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13568-5.

Levitus, S., Matishov, G. G. Seidov, D. & Smolyar, I. Barents Sea multidecadal variability, Geophys. Res. Lett., vol. 36, no. Oct. 2009, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009gl039847.

Carton, J. A., Chepurin, G. A., Reagan, J. & Häkkinen, S. Interannual to Decadal Variability of Atlantic Water in the Nordic and Adjacent Seas, J. Geophys. Res. 116, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011jc007102.

Årthun, M., Eldevik, T., Smedsrud, L. H., Skagseth, Ø. & Ingvaldsen, R. B. Quantifying the Influence of Atlantic Heat on Barents Sea Ice Variability and Retreat*,. J. Clim 25, 4736–4743 (2012).

Drinkwater, K. F. et al. The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation: Its manifestations and impacts with special emphasis on the Atlantic region north of 60°N. J. Mar. Syst. 133, 117–130 (2014).

Lien, V. S., Vikebø, F. B. & Skagseth, Ø. One mechanism contributing to co-variability of the Atlantic inflow branches to the Arctic. Nat. Commun. 4, 1488–1488 (2013).

Hobday, A. J. et al. Categorizing and Naming Marine Heatwaves, Oceanography, vol. 31, no. Jun. 2018, https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2018.205.

Cheng, L. et al. Improved estimates of ocean heat content from 1960 to 2015, Sci. Adv., vol. 3, no. Mar. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1601545.

Amaya, D. et al. Marine heatwaves need clear definitions so coastal communities can adapt, Nature, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00924-2.

Enfield, D. B., Mestas-Nuñez, A. M. & Trimble, P. The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation and its relation to rainfall and river flows in the continental U.S. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 2077–2080 (2001).

Asbjørnsen, H., Årthun, M., Skagseth, Ø. & Eldevik, T. Mechanisms of ocean heat anomalies in the Norwegian Sea. J. Geophys. Res. 124, 2908–2923 (2019).

Pfahl, S. & Wernli, H. Quantifying the relevance of atmospheric blocking for co-located temperature extremes in the Northern Hemisphere on (sub-)daily time scales, Geophys. Res. Lett., vol. 39, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012gl052261.

Elzahaby, Y., Schaeffer, A., Roughan, M. & Delaux, S. Why the Mixed Layer Depth Matters When Diagnosing Marine Heatwave Drivers Using a Heat Budget Approach, Front. Clim., vol. 4, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2022.838017.

Rodrigues, R. R., Taschetto, A. S., Sen Gupta, A. & Foltz, G. R. Common cause for severe droughts in South America and marine heatwaves in the South Atlantic. Nat. Geosci. 12, 620–626 (2019).

Schlegel, R. W., Oliver, E. C. J. & Chen, K. Drivers of Marine Heatwaves in the Northwest Atlantic: The Role of Air–Sea Interaction During Onset and Decline, Front. Mar. Sci., vol. 8, p. 627970, Mar. 2021.

Sen Gupta, A. et al. Drivers and impacts of the most extreme marine heatwave events. Sci. Rep. 10, 19359 (2020). volnoNov.

Ting, M., Kushnir, Y., Seager, R. & Li, C. Forced and Internal Twentieth-Century SST Trends in the North Atlantic*. J. Clim 22, 1469–1481 (2009).

Deser, C. & Phillips, A. S. Defining the Internal Component of Atlantic Multidecadal Variability in a Changing Climate, Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021gl095023.

Rigal, A., Azaïs, J.-M. & Ribes, A. Estimating daily climatological normals in a changing climate. Clim. Dyn. 53, 275–286 (2019).

Huang, B. et al. Improvements of the Daily Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (DOISST) Version 2.1. J. Clim 34, 2923–2939 (2021).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). 2023. https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47.

Wilks, D. S. Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/c2017-0-03921-6.

Åslund, O. Arctic Marine Heatwaves: Can the Development of Marine Heatwaves in the Nordic and Barents Seas be Linked to the Atmosphere?, Master’s thesis, Stockholm University, 2022.

Copernicus Climate Change Service, ERA5 hourly data on pressure levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS), 2018. https://doi.org/10.24381/CDS.BD0915C6.

Sherman, K. E. THE LARGE MARINE ECOSYSTEM CONCEPT: RESEARCH AND MANAGEMENT STRATEGY FOR LIVING MARINE RESOURCES. Ecol. Appl. 1, 349–360 (1991).

GEBCO Compilation Group, GEBCO 2020 Grid. 2020. https://doi.org/10.5285/a29c5465-b138-234d-e053-6c86abc040b9.

Rio, M.-H., Mulet, S. & Picot, N. Beyond GOCE for the ocean circulation estimate: Synergetic use of altimetry, gravimetry, and in situ data provides new insight into geostrophic and Ekman currents. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 8918–8925 (2014).

Liebmann, B. Description of a complete (interpolated) outgoing longwave radiation dataset. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc 77, 1275–1277 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the Swedish National Space Agency through the OCASES project (Dnr: 204/19). Some computations and data handling were enabled by resources provided by the National Academic Infrastructure for Supercomputing in Sweden (NAISS) at NSC, Linköping University, partially funded by the Swedish Research Council through grant agreement no. 2022-06725. This study has been conducted using E.U. Copernicus Marine Service Information and Copernicus Climate Data Store Information; 10.48670/mds-00327, 10.24381/cds.bd0915c6. We further want to extend our gratitude to E. Oliver for his publically available algorithms to calculate MHWs (https://github.com/ecjoliver/marineHeatWaves). Finally, we extend our thanks, for their valuable input and help, to Abdelwaheb B. A. Hannachi and Gabriele Messori, and to the anonymous reviewers who helped to improve the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stockholm University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.E. lead the work on the analysis of the MHW/MCS and their spatial patterns, further, identified the patterns of the drivers of MHW/MCS strengthening. E.E. wrote most of the paper and performed all analysis except for programming the windowed linear regression algorithm, and selecting the ERA5 data. E.E. handled the review process, including major changes to the multi-year time series analysis, rewriting of its interpretations, addition of correlation calculations, addition of wind and ocean current composites, clarifications of the relative importance of drivers, and addition of significance tests across the manuscript. Further, E.E. has during the review process updated and corrected the abstract and has rewritten the paper to address issues with the pentad analysis. L.C. designed the heat content analysis and the pentadal means, he also provided the idea of the averaged pressure gradient. L.C. further wrote the abstract and edited large parts of the manuscript, as well as commented on the whole manuscript. He provided the interpretation of the pentadal means. OÅ’s master’s thesis informed the design of the study, he provided the ERA5 data selection, the algorithm to calculate windowed linear regressions, and he commented on the entire manuscript. K.D. contributed through discussions and provided feedback on the manuscript. J.M. contributed through discussions and provided feedback on the manuscript. All co-authors contributed through commentary during the reviewing process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Florian Börgel and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jennifer Veitch, Heike Langenberg. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eisbrenner, E., Chafik, L., Åslund, O. et al. Interplay of atmosphere and ocean amplifies summer marine extremes in the Barents Sea at different timescales. Commun Earth Environ 5, 444 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01610-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01610-5

This article is cited by

-

Drivers of the summer 2024 marine heatwave and record salmon lice outbreak in northern Norway

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)