Abstract

Tropical convection plays a critical role in modulating the global climate by influencing climate variability. However, its future projection under climate mitigation scenarios remains uncertain. Here, we found that while the relationship between precipitation intensity and upward motion remains constant regardless of changing CO2 concentrations, the sea surface temperature threshold for tropical convection and the convective zone exhibit hysteretic and irreversible behavior. As the CO2 concentration decreases from its peak (ramp-down), higher tropical ocean temperature leads to higher sea surface temperature thresholds for convection than during the period of increasing CO2 concentration (ramp-up), while convective instability remains the same during both ramp-up and ramp-down. El Niño-like warming during the ramp-down leads to a weakening of the Walker circulation and an expansion of the convective zone in the central to eastern tropical Pacific by a warmer-get-wetter mechanism. Our results suggest that CO2 removal does not guarantee the recovery of tropical convection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many countries have set plans to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by the mid-21st century to limit global warming to well below 2 °C, and ideally 1.5 °C, above pre-industrial levels (the goal of the Paris Agreement)1. These warming targets are linked to climate tipping points, which are defined as “a critical threshold at which a tiny perturbation can qualitatively alter the state or development of a system”2,3 and can be diagnosed by reversibility and hysteresis in climate system responses to changes in the carbon dioxide (CO2) pathway4. Hysteresis represents a dynamic lag response of the climate system along symmetric changes in the greenhouse gas pathway (e.g., a decrease following an increase in CO2), while reversibility is the ability of the climate system to return to its initial state following these changes5,6. Therefore, understanding the response of the Earth system to variations in CO2, including reversibility and hysteresis, is essential for an adequate climate mitigation strategy and a sustainable future.

A representative pathway to achieve net-zero and carbon neutrality could be CO2 removal (CDR)7,8. There are a number of studies investigating the reversibility and hysteresis of the climate system in mean9,10 and extreme changes11,12,13, including climate variability such as the monsoon14,15, the Indian Ocean dipole16, and the Hadley cell17, using the CDR experiment with a symmetric CO2 pathway. In particular, the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is known to vary in its characteristics due to the irreversibility of the location of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) in the CDR experiment, which is driven by differences in the recovery rate of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)18,19,20. However, the irreversibility and hysteresis of precipitation in the tropics, where precipitation hysteresis is the greatest on Earth21, remain uncertain. Tropical convection influences global climate through the Hadley and Walker Circulations22,23, as well as influencing tropical cyclone activity24, the Madden-Julian Oscillation25, ENSO26, and mid-to-high latitude teleconnections27,28. Despite apparent global warming, the sea surface temperature (SST) threshold for convection in the tropics is expected to increase with the rate of mean tropical warming, so the area of the convective zone is expected to change little29,30. However, it remains unclear how tropical convection, including the SST threshold and convective zone area, will respond to the CDR.

Here, we have performed large ensemble simulations with the Community Earth System Model (CESM) 1.2.2 to investigate the change of tropical convection to CDR (see “Methods” section). To obtain robustness, we compare the results of the CDR Model Intercomparison Project (CDRMIP) simulation in eight Earth System Models (ESMs), participating in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6)8,31. When CO2 concentrations are quadrupled and later reduced to present levels, tropical convection (both the SST threshold for convection and the area of the convective zone) does not return perfectly to its present-day values despite a constant relationship between the upward motion threshold and precipitation.

Results

Tropical convection response to varying CO2 pathway

To investigate the change in the tropical convection under the CO2 pathway, we used an idealized CDR experiment with increasing CO2 concentration followed by a decrease using CESM (“Methods” section). In this experiment, the atmospheric CO2 concentration is increased from 367 ppm (the present level) to 1468 ppm (four times the present level) at a rate of 1% per year (ramp-up) and then decreased back to the present level (ramp-down). CESM reproduced the observed SST and precipitation of the present-day climate well, although with some bias (Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, the tropics have a higher proportion of convective precipitation to total precipitation than other regions (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Characteristics of tropical convection are defined by two variables, one being the SST threshold for convection, defined as the minimum SST above the convection threshold, and the other being the convective zone, defined as the sum of the grid area where annual mean precipitation exceeds 4 mm d−1 (see “Methods” section), commonly known as the baseline for tropical convection32.

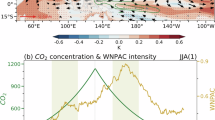

To understand the hysteresis of the tropical convection responding to a varying CO2 concentration pathway, the ramp-up and ramp-down periods are defined as a 31-year average, centered on the years 2070 and 2210, when CO2 concentrations are doubled relative to the present level (vertical shading in Fig. 1a, b). The tropical mean SST follows the trajectory of the CO2 concentration, with the largest warming (about 4 K relative to the present-day climate) when the CO2 concentration is at its maximum, followed by an attenuation of the warming as the CO2 concentration decreases (red and black lines in Fig. 1a). The precipitation response also changes along the CO2 concentration pathway, albeit with a time lag (blue line in Fig. 1a). The temporal discrepancy between tropical mean SST changes and CO2 concentrations is associated with the effect of inertia due to accumulated heat in the ocean and the shift of the ITCZ due to the hemispheric thermal contrast, resulting in El Niño-like warming in the tropics5,18,33. Meanwhile, the response of the SST threshold for convection to the CO2 pathway is different from that of the convective zone. The SST threshold for convection is similar to the tropical mean SST (red line in Fig. 1a, b), while the convective zone becomes larger after the CO2 concentration peak (green line in Fig. 1b). A convective zone during the ramp-up period is not much different from the present-day climate, but a substantial increase in the convective zone during the ramp-down period (vertical shading in Fig. 1b).

Time series of a tropical mean sea surface temperature (SST) anomaly (red line) and precipitation anomaly (blue line) and b SST threshold anomaly for convection (red line) and convective zone anomaly (green line) with CO2 concentration pathway (black line). Solid lines illustrate the ensemble mean of 28 members with an 11-year running mean and full confidence interval with ensemble maximum and minimum (shading). Red vertical shading indicates a ramp-up period and blue vertical shading indicates a ramp-down period. A trajectory of c the SST threshold anomaly for convection and d the convective zone anomaly during CO2 ramp-up (red), ramp-down (blue), and restoring (black) period (2281–2500). Color dots indicate the 11-year running average of the ensemble mean, and shading indicates the full ensemble range (ensemble maximum and minimum). All anomalies (denoted as Δ) were calculated as changes relative to the present day.

Hysteresis is defined by the size of the area of the loop under the trajectory of the CO2 concentration. and reversibility is defined as whether the trajectory returns to the initial state when the CO2 concentration returns to its present-day level, with an open loop indicating an irreversible change and a closed loop indicating a reversible change21. The hysteresis of the SST threshold for convection as a function of CO2 concentration shows a relatively small hysteresis area, compared to the that of convective zone due to an almost linear trajectory (Fig. 1c, d). However, the loop of the SST threshold for convection did not close immediately after returning to present CO2 levels, indicating an irreversible change. Meanwhile, the hysteresis of the convective zone increases in area with increasing CO2 concentration, but shows a larger increase in area during the post-peak decline in CO2 concentration, resulting in a large hysteresis area and an open loop, indicating significant irreversible changes (Fig. 1d).

Results from the CMIP6 CDRMIP over 280 years, where the CO2 concentration increased at a rate of 1% per year for the first 140 years and then decreased at the same rate for the next 140 years, also show similar hysteresis in the SST threshold for convection and in the convective zone (Supplementary Fig. 2). Due to delayed responses such as thermal inertia, the convective zone and the SST threshold for convection may tend to return to their initial state during the restoring period. However, they do not fully return to their initial state after 220 years of restoring periods, so these changes are considered irreversible in the present study.

Observed and simulated characteristics of the tropical SST threshold for convection

To understand the hysteresis of tropical convection, we first identify its observed characteristics (see “Methods” section). First, to determine the precipitation intensity corresponding to the convection threshold, we analyzed the correlation between the vertical velocity at 500 hPa (hereafter ω500) and precipitation in the tropics on a monthly timescale. Typically, convection in the tropics is driven by upward motion, represented by negative values of ω500. Therefore, identifying the precipitation intensity that corresponds to zero ω500 values allows us to conclude that precipitation above this threshold is likely due to convection. The bivariate frequency distributions of monthly ω500, where a negative value indicates an upward motion and monthly precipitation aggregated over grids of tropical regions (20°S–20°N) over the observation period (1979–2022) show that there is a negative relationship between ω500 and precipitation (Fig. 2a). We used ω500 as a proxy for convection because 500 hPa is the middle layer where the maximum tropical convection occurs34. The precipitation where the linear regression line between ω500 and precipitation based on the least squares method passes through zero can be taken as the convection baseline. A negative ω500 indicates convective motion, i.e. a lower ω500 indicates stronger upward motion. Accordingly, precipitation corresponding to a negative ω500 can be attributed to convection. This value in the observation is about 3.2 mm d−1 (purple marker in Fig. 2a), which means that 4 mm d−1 of the precipitation is mainly due to convection32. Therefore, although the observed value is 3.2 mm d−1, the 4 mm d−1 precipitation intensity we used is suitable as a convection threshold. This correlation remains constant when analyzed over three decadal periods (1979–1993, 1994–2008, 2009–2022), indicating that the correlation between precipitation and ω500 over the tropics is robust regardless of time (Fig. 2a).

a Joint probability density distribution of observed vertical velocity at 500 hPa and precipitation over the tropical ocean at each grid point from 1979 to 2022. Markers indicate the precipitation intensity corresponding to zero vertical velocity over the observation period (1979–2022, 1979–1994, 1995–2008, 2009–2022) with regression lines. b Relationship between the tropical mean SST from HadISST and the tropical mean 300 hPa temperature in ERA5. Shading indicates the corresponding SST threshold for convection based on HadISST with GPCP v2.3 from 1979 to 2022, while purple markers without shading indicate from 1950 to 1978. A solid line indicates the regression line for 73 years. c CESM simulated joint probability density distribution of vertical velocity at 500 hPa and precipitation over the tropical ocean at each grid point during the present day. The markers and lines represent the same things as in (a). Blue colors indicate the value of the ramp-down period (2070) and red colors indicate the value of the ramp-up period (2210). d Relationship between the tropical mean SST and the tropical mean 300 hPa temperature in CESM during the ramp-up and ramp-down. Markers indicate the ensemble-averaged 31-year value of the ramp-down period (red) and the ramp-down period (blue). A colored legend indicates the corresponding SST threshold for convection. The correlation coefficient (corre. coeff.) and slope of both periods are also provided.

In the tropics, the moist static energy depends largely on the SST due to the limited variability in relative humidity and the air-sea temperature difference35. In the upper troposphere, equatorial waves efficiently smooth out temperature gradients, resulting in a more horizontally uniform temperature distribution than that of the SST. These characteristics lead to convective instability in the tropics being highly dependent on the local SST. Additionally, tropospheric temperatures in the tropics roughly follow a moist-adiabatic temperature profile, indicating an adjustment of upper tropospheric temperatures in response to mean SST in the tropics. Since the temperature of the upper troposphere is adjusted by the tropical mean SST, the minimum SST for generating convection can be higher than the tropical mean SST, allowing rising air to remain buoyant and supporting convection. Combining these two features, there is co-variability between the tropical mean SST and the SST threshold for convection29. We aim to identify how this co-variability responds to a varying CO2 pathway during the ramp-up and ramp-down periods. The SST threshold for convection in the tropics is associated with the coupling between the tropical mean SST and the tropical mean temperature at 300 hPa in the observations29 (Fig. 2b). Tropical convection is associated with instability, which is also associated with temperature in the upper troposphere. We used a temperature of 300 hpa to represent the upper troposphere29. There is a strong linear relationship between the tropical mean SST and the mean temperature at 300 hPa with a correlation coefficient of 0.94 and a slope of 0.43 °C per °C from 1950 to 2022, implying that the temperature increase in the upper troposphere should be greater than at the surface due to moist-adiabatic lapse rate adjustment29. This is because the moist-adiabatic lapse rate adjustment which accelerates the warming of the upper troposphere due to the release of latent heat from water vapor, resulting in a stronger warming of the upper troposphere than the tropical SST29,34. Therefore, in this vertical temperature structure, the SST threshold for convection (shading in Fig. 2b) is highly tied to either the tropical mean SST (correlation coefficient is 0.78 and p-value < 0.001 by student t-test) or tropical mean temperature at 30 0hPa (correlation coefficient is 0.67 and p-value < 0.001 by student t-test) from 1979 to 2022 when precipitation observations are available.

Meanwhile, the CESM reproduced the observed linear relationship between ω500 and precipitation in the 900-year present-day climate simulation (Fig. 2c). The precipitation corresponding to the upward motion (corresponding to zero ω500) is also about 4 mm d−1 in the CESM present-day climate simulation (black marker in Fig. 2c). Despite the CO2 concentration being twice that of the present-day climate, the correlation between precipitation and ω500 remains similar to the present day for both the ramp-up and ramp-down periods (blue and red lines in Fig. 2c). Furthermore, the precipitation intensity corresponding to the upward motion in both periods is 4.0 mm d−1, indicating the weak influence of changing CO2 pathway on the relationship between the upward motion and precipitation intensity. On the other hand, the SST threshold for the convection is highly dependent on the change in CO2 concentration (Fig. 2d). The ramp-up and ramp-down climate simulation in the CESM reproduces well the observed correlation between tropical mean 300 hPa temperature and tropical mean SST (stipples in Fig. 2d). It is found that the ramp-down period shows a higher temperature both at the surface and at 300 hPa than the ramp-up period in spite of the same CO2 concentration. Nevertheless, the linear relationship between 300 hPa mean temperature and tropical mean SST is nearly identical in both periods, implying that the corresponding SST threshold for convection is largely determined by either the tropical mean SST or 300 hPa mean temperature. To remove the influence of internal variability, we calculated the regression coefficients using the ensemble mean of the 28 ESMs. Each ensemble model contains internal variability, but averaging the ensemble model tends to suppress the internal variability and isolates the effect of the external forcing36,37. The slope of the tropical mean SST to the mean temperature at 300 hPa was found to be 0.45 °C per °C during the ramp-up period and 0.44 °C per °C during the ramp-down period.

The high linear correlation between the tropical mean temperature at 300 hPa and the SST threshold for convection due to the moist-adiabatic lapse rate adjustment is also found in the eight CMIP6 CDRMIP ESMs over 280 years. Although the absolute value of the tropical mean temperature at 300h Pa and SST threshold for the convection varies between ESMs, the regression coefficient of tropical 300 hPa mean temperature on the SST threshold for the convection ranges from 0.40 to 0.46 (°C per °C) (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The sensitivity test at altitudes other than 300 hPa produced the similar results regardless of altitude (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5).

The CESM experiments reproduced well the observed negative correlation between ω500 and precipitation. The precipitation corresponding to zero ω500 is 4 mm d−1, confirming the validity of our convection threshold of 4 mm d−1. However, the CESM tends to overestimate the slope of the relationship between ω500 and precipitation compared to observations (Fig. 2a, c). This discrepancy may lead to an overestimation of the precipitation response at high SSTs associated with negative ω500, thereby contributing to uncertainty in future climate change projections.

Convective zone hysteresis and SST changes to the CO2 changes

Despite the high correlation between the tropical mean SST and the SST threshold for convection, the area of the convective zone has increased during the ramp-down (Fig. 1b). To identify the changes in the convective zone along the CO2 concentration trajectory, we examined the relationship between SST and precipitation and the distribution of SST. The ensemble-averaged precipitation intensity and the SST frequency distribution as a function of SST exhibit in detail the changes in the relationship between SST and precipitation in the tropics in response to CO2 change for each period, including the ramp-up and ramp-down periods (Fig. 3). Here, monthly precipitation over the tropical ocean is binned by monthly SST with 0.1 °C width, and then the twelve months were aggregated and averaged for each bin to create an annual relationship between SST and precipitation (lines in Fig. 3, see “Methods” section).

a Ensemble mean precipitation intensity as a function of SST and b SST frequency distribution in the present day (black line), ramp-up (red line), and ramp-down (blue line) periods with the observations (purple line). Colored dots indicate the ensemble mean of tropical mean SST while dashed vertical lines indicate SST threshold for convection. The shading of present day (900 years, black) and observation (34 years, purple) indicate the range of maximum and minimum values over each period, while the shading of ramp-up (red) and ramp-down (blue) indicates the range (maximum and minimum) over the entire ensemble.

In the present-day climate, precipitation intensity increases steeply at SSTs above 27 °C in both the CESM and the observations. Furthermore, the present-day SST threshold for convection in the CESM, averaged over 900 years, is 27.8 °C, very similar to the observed value of 27.9 °C (black and purple vertical dashed lines in Fig. 3a). In the present-day simulations in the CESM, the tropical mean SST (black marker in Fig. 3a) tends to coincide with the SST threshold for the convection (black vertical dashed line in Fig. 3a). The relationship between SST and precipitation intensity during the ramp-up and ramp-down periods shows a shift of the present-day fitted relationship. Although both the ramp-down and ramp-up periods have CO2 concentrations twice as high as the present-day climate, the ramp-down period has a higher tropical mean SST than the ramp-up period, resulting in a more rightward shift of the precipitation-SST line (markers in Fig. 3a). This also results in a higher SST threshold for convection during the ramp-down period, due to the almost constant convective instability across changes in CO2 concentration (Fig. 2c).

On the other hand, the frequency (i.e. total 9091 grids) distribution of tropical SSTs differed significantly in the ramp-up and ramp-down periods (Fig. 3b). The present-day climate simulation reproduces the observed negative skewness in the tropical SST distribution, which shows the higher frequency at high SSTs than at low SSTs (purple and black lines in Fig. 3b)38. This tropical SST frequency distribution is similar to the present-day climate in the ramp-up period, although shifted towards warmer temperatures due to tropical warming. In contrast, its shape is different in the ramp-down period with higher frequencies at warmer temperatures. In particular, the SST threshold for convection is strongly coupled with the tropical mean SST (Fig. 1), so that an increase in the frequency of grids with high temperatures in the ramp-down period indicates an increase in the convective zone area. The area above the SST threshold for convection (30.1 °C) during the ramp-down period is about 72,530,000 km2, more than nearly 1,460,000 km2 larger than the about 71,070,000 km2 above the SST threshold for convection (29.2 °C) during the ramp-up period. This difference is almost the size of the state of Alaska (1,723,000 km²). Precipitation intensity and the SST frequency distribution in the ramp-up and ramp-down periods also show similar patterns, except for the shifted differences due to tropical mean temperature differences (Supplementary Fig. 3b and 3c). Meanwhile, the confidence intervals for the present-day experiment are much larger than for the ramp-up and ramp-down experiments (shadings in Fig. 3). This is because the present-day experiment is a 900-year repeat at the same CO2 concentration, and the internal variability affects the confidence interval. On the other hand, the ramp-up and ramp-down periods are calculated over 31 years with 28 ensembles, but the effect of external forcing is dominant because the CO2 concentration changes by 1% during this period. This results in a narrower confidence interval than that in the present day.

The present-day simulation of CESM overestimates the tropical mean SST, although the SST threshold for convection remains similar. We investigate the influence of this bias on the relationship between the SST threshold for convection and tropical mean SST using eight CMIP6 CDRMIP ESMs. In the historical mean (1955–2014), there is a statistically significant positive correlation between the tropical mean SST and the SST threshold for convection, although their absolute values differ (Supplementary Fig. 6a). The regression coefficient is greater than one, indicating that the two variables are not perfectly correlated. These differences may be partially attributed to internal variability, such as ENSO29. Observations and present-day CESM results also lie adjacent to the regression line, indicating that despite the differences in absolute values simulated by the CMIP6 CDRMIP ESMs, the relationship between the tropical mean SST and the SST threshold for convection is significant (Supplementary Fig. 6a).

However, the inter-model correlation of the present-day tropical mean SST with the Transient Climate Response (TCR) is −0.12, which is not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Similarly, the inter-model correlation of the SST threshold for convection with the TCR is not statistically significant, at −0.03 (Supplementary Fig. 6c). This suggests that the hot model problem, where climate models overestimate present-day tropical SSTs to project exaggerated future changes, is not related to changes in tropical convection characteristics.

The spatial pattern of precipitation and SST changes during the ramp-up and ramp-down periods is quite different, despite the same atmospheric CO2 concentration (Fig. 4). The change in the convective zone, defined as areas where annual precipitation is greater than 4 mm d−1 (“Methods” section), is consistent with the pattern of precipitation change, with both the ramp-up and the ramp-down periods expanding at the edge of the present-day convective zone where precipitation has increased (Fig. 4a, b). The extension is particularly evident in the tropical central and eastern Pacific, where the increase in precipitation is substantial, and in the western Indian Ocean. Comparing the ramp-up and ramp-down periods, the difference is clear (Fig. 4c). The expansion of the convective zone in the central and eastern Pacific during the ramp-down period is more pronounced than during the ramp-up period, as is the expansion at the edge of the present-day Indian Ocean convective zone. On the other hand, in the Northern Hemisphere Pacific, there is less precipitation in the ramp-down period than in the ramp-up period, resulting in a reduction of the convective zone. This is associated with a greater increase in precipitation in the Southern Hemisphere along with the southward shift of the ITCZ due to an interhemispheric energy imbalance caused partly by the weakening of the AMOC18.

a–c precipitation changes relative to the present day (2000) for a ramp-up (2055–2085), b ramp-down (2195–2225), and c the difference (ramp-down minus ramp-up). Contour indicates a convective zone, defined as precipitation more than 4 mm d−1, in the present day. Red stipples in (a) and (b) indicate an expanded convective zone, while blue stipples indicate a reduced convective zone relative to the present day. The stipples in (c) show the change in the convective zone from ramp-up to ramp-down. d–f. Same as (a)–(c) but for the SST.

Changes in tropical rainfall are due to changing patterns of hydrological cycles. One is increased rainfall in the present-day convective zone (wet-get-wetter), and the other is increased rainfall where the rise in SST exceeds the mean tropical warming (warmer-get-wetter)29,39,40,41,42. The change in SST during the ramp-up and ramp-down relative to the present-day climate indicates increased precipitation and an expanded convective zone in regions of stronger warming (Fig. 4d, e). On the other hand, the temperature change at 300 hPa is relatively homogeneous compared to the surface for both the ramp-up and ramp-down periods (Supplementary Fig. 7). Both periods show an El Niño-like warming pattern with strong warming in the eastern Pacific and western Indian Oceans, resulting in a large expansion of the convective zone in there (Fig. 4f). The CMIP6 CDRMIP ESMs also show that the convective zone expanded more at the edges of its ramp-up location during the ramp-down period, especially in the central and eastern Pacific, although there are some differences in the exact locations of these edges between the ESMs (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Linkage of convective zone hysteresis with tropical atmospheric circulation

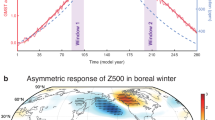

The distribution of convection and SST in the tropics is closely associated with the Walker circulation43. For example, regions of enhanced convection and higher SSTs typically correspond to areas of ascending motion in the Walker circulation, while regions of suppressed convection and lower SSTs correspond to areas of descending motion. The tropical convective zone, defined as annual precipitation greater than 4 mm d−1, is associated with upward motion. In the present-day climate, there is a good consistency between the 4 mm d−1 line and the zero line of ω500 (Fig. 5a). To understand the hysteresis of the convective zone area, we examine two representative Walker circulation indices: one is the difference in ω500 between 10° S–10° N, 180°–100° W and 10° S–10° N, 100° E–150° E (green box in Fig. 5a)44 and the other is the sea level pressure difference between 5° S–5° N, 160° W–80° W and 5° S–5° N, 80° E–160° E (yellow box in Fig. 5a)45. There is a weakening of the Walker circulation as CO2 increases, and it does not recover immediately after peaking so that even when it returns to the present-day climate CO2 concentration, the Walker circulation remains weakened in both indices (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, the Walker circulation was weaker during the ramp-down period than during the ramp-up period, despite the same CO2 concentration (Fig. 5b). This leads to a difference in the convective zones between the two periods (Fig. 5c). Over the 900 years simulated in the present-day climate, the Walker circulation and the convective zone have a strong negative correlation with a correlation coefficient of −0.73 (gray ellipse in Fig. 5c). This indicates that the Walker circulation is weaker in the ramp-down period than in the ramp-up period, resulting in a larger convective zone. This is due to the strengthening of El Niño-like mean SST in the ramp-down period compared to the ramp-up period, with stronger warming in the eastern tropical Pacific than in the western tropical Pacific, resulting in a decrease in the east-west SST gradient in the tropical Pacific (see also Fig. 4e). This, in turn, leads to a decrease in the Walker circulation and an expansion of the convective zone.

a Vertical velocity at 500 hPa in the present-day (shading) and Walker circulation domains (colored boxes). Green boxes are Walker circulation domains for vertical velocity, while yellow boxes are surface pressure. The solid contour indicates the convective zone in the present day (defined as 4 mm d−1 of precipitation intensity), and the dashed contour indicates the zero line of the vertical velocity at 500 hPa. b Time series of the Walker circulation anomaly based on vertical velocity (green) and surface pressure (yellow) following the CO2 concentration pathway. Solid lines illustrate the ensemble mean of 28 members with an 11-year running mean and full ensemble range (ensemble maximum and minimum, shading). c Scatter plot for the Walker circulation intensity and convective zone in the present day (gray), ramp-up (red), and ramp-down (blue). Filled stipples indicate whole-period means while empty stipples indicate ensemble means during each period (31 years). The gray ellipse indicates the 5–95% range, derived from the multivariate normal distribution in the present day (900 years) with a regression line.

Implications of Hysteretic Behavior of Tropical Convection

To understand the hysteretic behavior of tropical convection in the future, we further analyzed future scenarios under different climate change mitigation policies (Fig. 6). We used 14 CMIP6 ESMs in five Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs: SSP1-1.9, SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5). This provides insight into the changes in SST thresholds for convection and the convective zone under different future climate change mitigation policies. All calculations for the variables were made relative to the pre-industrial (1850–1900) period (see “Methods” section). In all SSP scenarios, the SST threshold for convection and the convective zone are projected to increase with increasing CO2 concentrations, with the largest increases projected under the high-emission scenario SSP5-8.5. The most notable aspect appears towards the end of the 21st century in the SSP1-1.9 and SSP1-2.6 scenarios (light blue and dark blue lines in Fig. 6a, b), where CO2 concentrations decrease. Both tropical convection variables show higher values in the late 21st century compared to the early to mid-21st century, despite the same CO2 concentrations in these scenarios. This is consistent with the hysteretic behavior in the CDR experiments (Fig. 1c, d), indicating that comprehensive long-term climate mitigation and adaptation strategies are necessary to consider the hysteretic behavior of tropical convection.

A trajectory of a the SST threshold anomaly for convection and b the convective zone anomaly under historical (1850–2014) and five SSP scenarios (SSP1−1.9, SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5) from 14 CMIP6 ESMs. Dots indicate the 11-year running average of the multi-model mean, and shading indicates the inter-model range (maximum and minimum values). All anomalies (denoted as Δ) were calculated as changes relative to the pre-industrial period (1850−1900).

Discussion

We demonstrated the irreversibility and hysteresis of tropical convection in a CDR experiment in which the CO2 concentration was increased to four times the present-day level and then decreased to the present-day level at a rate of 1% per year. We found that tropical convection characteristics, including the SST threshold for tropical convection and the convective zone, do not return to their present-day climate when the CO2 concentration returns to its present-day level, indicating irreversible changes.

Our present-day simulation generally reproduces the observed tropical convection characteristics well but tends to overestimate SST and precipitation over the eastern Pacific in the Southern Hemisphere (Supplementary Fig. 9). This bias causes the simulated SST-precipitation correlation to overestimate the mean precipitation intensity at high temperatures above 28 °C compared to observations (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, this region is associated with the eastern edge of SPCZ46, where the difference in convective zones during the ramp-up and ramp-down periods was evident (Fig. 4c). This bias could lead to an overestimation of the present-day area of the convective zone and the precipitation intensity within these areas. In particular, the present-day CESM simulation overestimates the observed convective zone in the eastern Pacific of the Southern Hemisphere. This could potentially affect the location of convective zone changes in ramp-up/down experiments. In addition, strong variability in SST and precipitation in the central and eastern tropical Pacific may lead to an overestimation of the response of convection to changes in CO2, as these regions are particularly sensitive to CO2 changes47. Therefore, improving the simulation performance of precipitation and SST in these regions is necessary to reduce future uncertainties.

The SST threshold for tropical convection tended to match the tropical mean SST due to convective instability, but the area of the convective zone tended to increase during the ramp-down period than during the ramp-up period, even though the CO2 concentration was the same in both periods. This is due to the irreversibility of the SST distribution in the tropics, which leads to increased convection in the central and eastern Pacific. According to the warmer-get-wetter mechanism41, the stronger warming in the eastern Pacific during the ramp-down period than during the ramp-up period leads to an expansion of the convective zone in the central and eastern Pacific. This is also associated with a weakening of the Walker circulation.

The results of this study are based on a scenario in which CO2 concentrations increase by 1% per year, following the standard guidelines of the CDRMIP. In sensitivity experiments with varying CO2 speed (0.5%, 1.5%, and 2% per year) using a single ensemble, the hysteresis, and irreversibility of tropical convection characteristics were similar to those observed at a 1% per year increase (Supplementary Fig. 10). Irreversible changes in the tropical convection characteristics can affect tropical climate variability, such as the Walker circulation and ENSO, which modulate global climate. In particular, changes in tropical convection may also affect precipitation over remote land areas through teleconnection mechanisms. Therefore, quantifying the detailed influences of tropical convection changes is fundamentally required to develop appropriate strategies for climate change adaptation and mitigation.

Methods

Experiment design and observation

We used the fully coupled general circulation model (CGCM) experiments from the fully coupled Community Earth System Model version 1.2.2 (CESM1.2.2)48. The model is composed of the atmosphere (Community Atmospheric Model version 5), ocean (Parallel Ocean Program version 2), sea ice (Community Ice Code version 4), and land models (Community Land Model version 4). The atmospheric model has a horizontal resolution of approximately 1° and 30 vertical levels48. The ocean model has 60 vertical levels, with a longitudinal resolution of 1° and a gradually changing latitudinal resolution of 1/3° near the equator to 1/2° near the poles49. The land model includes the carbon–nitrogen cycle50. First, the present-day (PD) is run with a constant CO2 concentration (367 ppm) for 900 years with a single ensemble from which we extracted 28 initial conditions. Before the PD period, the model is run for 800 years. Second, the CO2 concentration level was increased from 367 ppm to 1478 ppm (4 × CO2) at a rate of 1% per year for 140 years (ramp-up period) and then decreased back to 367 ppm at the same rate for 140 years (ramp-down period). After the ramp-down period, the CO2 level is fixed at 367 ppm for 220 years (restoration period). This phase is run with 28 ensemble members with different initial conditions extracted from the PD period51. The initial conditions are set to have different phases of the multi-decadal climate oscillations. In addition, the hysteresis of the tropical convection to the CO2 ramp-up and ramp-down forcing was compared using 8 ESMs from the CMIP6 (ACCESS-ESM1-5, CanESM5, CESM2, CNRM-ESM2-1, GFDL-ESM4, MIROC-ES2L, NorESM2-LM, and UKESM1-0-LL). Detailed model information is provided in Supplementary Table 1. We used the dataset of the 1pctCO2 scenario dataset from the CMIP6 Diagnostic, Evaluation, and Characterization of Klima (DECK)31 and the 1pctCO2-cdr scenario from the Carbon Dioxide Removal Model Intercomparison Project (CDRMIP)8. The experimental setup is almost identical to our simulations except for the initial CO2 concentration level (284.7 ppm at the pre-industrial level). Furthermore, to provide insight into the changes in SST thresholds for convection and the convective zone under different future climate change mitigation policies, we used additional 14 CMIP6 ESMs (CAMS-CSM1-0, CanESM5, CanESM5-1, CNRM-ESM2-1, EC-Earth3, EC-Earth3-Veg, EC-Earth3-Veg-LR, GFDL-ESM4, GISS-E2-1-G, IPSL-CM6A-LR, MIROC6, MIROC-ES2L, MRI-ESM2-0, and UKESM1-0-LL) in five Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs: SSP1-1.9, SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5). In this case, the anomalies of the variables were made relative to the pre-industrial period (1850–1900).

Observed SST from the Hadley Centre Sea Ice and Sea Surface Temperature (HadISST)52 and precipitation from the Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) v2.353, which provides precipitation estimates based on a mix of satellite and rain gauge measurements since 1979, were used to compare model results with observations. We used 1979–2022 as the present for observations where both data are available. The latest European Centre for Medium Range Weather (ECMWF) ERA554 was used for upper air temperature and vertical velocity. To calculate the correlation between tropical mean SST and the upper troposphere temperature, we used long-term data, from 1950 to 2022. Observations and CMIP6 results were interpolated with a horizontal resolution of 1° × 1°.

Reversibility and hysteresis

We define hysteresis and irreversibility as follows:

Hysteresis

A trajectory of the climate variables (SST threshold for convection and convective zone) under the CDR experiment is represented as a loop (Fig. 1c, d). The CO2 concentration (\(F\)) is increased from the present-day level (\({F}_{{presnt}-{day}}\)) to the peak at four times the present-day level (\({F}_{{peak}}\)). It is then returned to the present-day level (\({F}_{{presnt}-{day}}\)). We define hysteresis as the area of the loop (\(A\)) along the CO2 pathway based on the different values of the climate variables as CO2 increases (\({x}_{{up}}\)) and decreases (\({x}_{{down}}\)).

If the loop area (\(A\)) is positive along the CO2 pathway, the climate variable has hysteresis21. We defined significant hysteresis when the loop area (\(A\)) is positive in all 28 ensembles in the year 2280 when CO2 concentration returns to its present-day level.

Irreversibility

In the CDR experiment, the reversibility of a system is defined as whether the trajectory returns to its initial state, indicated as an open-loop (irreversible change) and closed-loop (reversible change)21:

A reversible change is defined as a closed-loop trajectory of the climate variable returning to the present-day level of CO2 concentration, whereas an irreversible change is defined as an open-loop trajectory. However, an open-loop trajectory does not always indicate that a system is completely irreversible. An open-loop trajectory does not imply a fully irreversible change because of the delayed response of the climate system5. To account for the influence of the delayed response on the recovery of the climate system, we used a Student’s t-test to assess the irreversibility of climate variables by comparing the last 30 years of the recovery period with the 900 years of the present-day simulation. If the difference was significant at the 99% confidence level, we assumed that the climate variables had changed irreversibly.

SST threshold for convection and convective area

To identify the annual SST threshold for convection, we calculate the monthly mean precipitation rate corresponding to the monthly SST, binned at intervals of 0.1 K intervals in the tropical ocean (20°S–20°N) \during each year (January to December) of the research period including (present day, ramp-up, ramp-down, and restoring). The SST threshold for convection is a minimum SST where the mean precipitation rate is more than a limit of 4 mm d−1 for at least three consecutive SST bins to avoid noise in the annual precipitation rate curves.

Walker circulations

We used two indices to estimate the strength of the Walker circulation44. The first index is defined as the difference of the area-averaged sea level pressure (SLP) between the eastern Pacific (5° S–5° N, 160° W–80° W) and western Pacific (5° S–5° N, 80° E–160° E)45. Positive values represent an enhanced Indo-Pacific SLP gradient, indicating a stronger Walker circulation. The second index derived from the difference of the area average 500-hPa vertical velocity anomaly between the eastern Pacific (10° S–10° N, 180°–100° W) and western Pacific (10° S–10° N, 100° E–150 °E)55 and positive values indicate a stronger Walker circulation.

Sensitivity test

To understand how the SST threshold for convection and the convective zone respond to different rates (0.5%, 1.5%, and 2% per year) up to a similar CO2 concentration (4 times the present-day concentration with 376 ppm). The restoring period is 15 years, 40 years, and 160 years for the 0.5%, 1.5%, and 2% per year scenario, respectively, using a single ensemble member (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data related to the paper can be downloaded from the following/• CMIP6 database, https://esgf-data.dkrz.de/search/cmip6-dkrz/ • HadISST v1.1, https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/. • GPCP v2.3, https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.gpcp.html. • ERA5, https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/dataset/ecmwf-reanalysis-v5. • CESM CDR https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27013222.

Code availability

All plots and analyses were carried out using NCAR Command Language (NCL) version 6.6.2. To interpolate the model grid data, we used climate data operators (CDOs) available at https://code.mpimet.mpg.de/projects/cdo/. All code files are available upon reasonable request.

References

IPCC. Climate change 2021: the physical science basis. In Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R. & Zhou, B.) Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896 (in the press).

Lenton, T. M. et al. Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 1786–1793 (2008).

Lenton, T. M. et al. Climate tipping points—too risky to bet against. Nature 575, 592–595 (2019).

Armstrong McKay, D. I. et al. Exceeding 1.5 C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science 377, eabn7950 (2022).

Boucher, O. et al. Reversibility in an Earth system model in response to CO2 concentration changes. Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 024013 (2012).

Swingedouw, D. et al. Early warning from space for a few key tipping points in physical, biological, and social-ecological systems. Surv. Geophys. 41, 1237–1284 (2020).

King, A. D. et al. Preparing for a post-net-zero world. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 775–777 (2022).

Keller, D. P. et al. The Carbon Dioxide Removal Model Intercomparison Project (CDRMIP): rationale and experimental protocol for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 1133–1160 (2018).

Yeh, S.-W., Song, S.-Y., Allan, R. P., An, S.-I. & Shin, J. Contrasting response of hydrological cycle over land and ocean to a changing CO2 pathway. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 4, 53 (2021).

Oh, J. H., An, S. I., Shin, J. & Kug, J. S. Centennial memory of the Arctic Ocean for future Arctic climate recovery in response to a carbon dioxide removal. Earths Future 10, e2022EF002804 (2022).

Jo, S. Y. et al. Hysteresis behaviors in East Asian extreme precipitation frequency to CO2 pathway. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099814 (2022).

Mondal, S. K. et al. Hysteresis and irreversibility of global extreme precipitation to anthropogenic CO2 emission. Weather Clim. Extrem. 40, 100561 (2023).

Pathirana, G. et al. Increase in convective extreme El Niño events in a CO2 removal scenario. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh2412 (2023).

Oh, H. et al. Contrasting hysteresis behaviors of Northern hemisphere land monsoon precipitation to CO2 pathways. Earths Future 10, e2021EF002623 (2022).

Paik, S., An, S. I., Min, S. K., King, A. D. & Shin, J. Hysteretic behavior of global to regional monsoon area under CO2 ramp‐up and ramp‐down. Earths Future 11, e2022EF003434 (2023).

An, S.-I. et al. Intensity changes of Indian Ocean dipole mode in a carbon dioxide removal scenario. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 20 (2022).

Kim, S.-Y. et al. Hemispherically asymmetric Hadley cell response to CO2 removal. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg1801 (2023).

Kug, J.-S. et al. Hysteresis of the intertropical convergence zone to CO2 forcing. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 47–53 (2022).

Liu, C. et al. ENSO skewness hysteresis and associated changes in strong El Niño under a CO2 removal scenario. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 117 (2023).

Liu, C. et al. Hysteresis of the El Niño–southern oscillation to CO2 forcing. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh8442 (2023).

Kim, S.-K. et al. Widespread irreversible changes in surface temperature and precipitation in response to CO2 forcing. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 834–840 (2022).

Park, I.-H., Yeh, S.-W., Min, S.-K., Ham, Y.-G. & Kirtman, B. P. Present-day warm pool constrains future tropical precipitation. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 310 (2022).

Fasullo, J. & Webster, P. Warm pool SST variability in relation to the surface energy balance. J. Clim. 12, 1292–1305 (1999).

Zhang, G. Warming-induced contraction of tropical convection delays and reduces tropical cyclone formation. Nat. Commun. 14, 6274 (2023).

Roxy, M. K. et al. Twofold expansion of the Indo-Pacific warm pool warps the MJO life cycle. Nature 575, 647–651 (2019).

Lee, S.-K. et al. Pacific origin of the abrupt increase in Indian Ocean heat content during the warming hiatus. Nat. Geosci. 8, 445–449 (2015).

Li, L., Lozier, M. S. & Li, F. Century-long cooling trend in subpolar North Atlantic forced by atmosphere: an alternative explanation. Clim. Dyn. 58, 2249–2267 (2022).

Wang, G. et al. Future Southern Ocean warming linked to projected ENSO variability. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 649–654 (2022).

Johnson, N. C. & Xie, S.-P. Changes in the sea surface temperature threshold for tropical convection. Nat. Geosci. 3, 842–845 (2010).

Leung, J. C.-H. et al. Differential expansion speeds of Indo-Pacific warm pool and deep convection favoring pool under greenhouse warming. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 97 (2022).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Neelin, J. D., Münnich, M., Su, H., Meyerson, J. E. & Holloway, C. E. Tropical drying trends in global warming models and observations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 6110–6115 (2006).

Wu, P., Wood, R., Ridley, J. & Lowe, J. Temporary acceleration of the hydrological cycle in response to a CO2 rampdown. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010GL043730 (2010).

Kim, H.-R., Ha, K.-J. & Lau, W. K. M. Changes in the SST-precipitation relationship over the Indo-Pacific warm pool under a warming climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 074031 (2023).

Williams, E. & Renno, N. An analysis of the conditional instability of the tropical atmosphere. Mon. Weather Rev. 121, 21–36 (1993).

Lehner, F. et al. Partitioning climate projection uncertainty with multiple large ensembles and CMIP5/6. Earth Syst. Dyn. 11, 491–508 (2020).

Park, I. H. et al. North Atlantic warming hole modulates interhemispheric asymmetry of future temperature and precipitation. Earths Future 12, e2023EF004146 (2024).

Park, I. H., Yeh, S. W., Min, S. K. & Son, S. W. Emergent constraints on future expansion of the Indo‐Pacific warm pool. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097343 (2022).

Held, I. M. & Soden, B. J. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J. Clim. 19, 5686–5699 (2006).

Chou, C., Neelin, J. D., Chen, C.-A. & Tu, J.-Y. Evaluating the “rich-get-richer” mechanism in tropical precipitation change under global warming. J. Clim. 22, 1982–2005 (2009).

Xie, S.-P. et al. Global warming pattern formation: sea surface temperature and rainfall. J. Clim. 23, 966–986 (2010).

Huang, P., Xie, S.-P., Hu, K., Huang, G. & Huang, R. Patterns of the seasonal response of tropical rainfall to global warming. Nat. Geosci. 6, 357–361 (2013).

Song, S.-Y. et al. Asymmetrical response of summer rainfall in East Asia to CO2 forcing. Sci. Bull. 67, 213–222 (2022).

Chung, E.-S. et al. Reconciling opposing Walker circulation trends in observations and model projections. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 405–412 (2019).

Vecchi, G. A. et al. Weakening of tropical Pacific atmospheric circulation due to anthropogenic forcing. Nature 441, 73–76 (2006).

Brown, J. R. et al. South Pacific Convergence Zone dynamics, variability and impacts in a changing climate. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 530–543 (2020).

Yun, K.-S. et al. Increasing ENSO–rainfall variability due to changes in future tropical temperature–rainfall relationship. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 43 (2021).

Hurrell, J. W. et al. The community earth system model: a framework for collaborative research. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 94, 1339–1360 (2013).

Smith, R. et al. The Parallel Ocean Program (POP) Reference Manual Ocean Component of the Community Climate System Model (CCSM) and Community Earth System Model (CESM), Rep. LAUR-01853 (UCAR, 2010).

Lawrence, D. M. et al. Parameterization improvements and functional and structural advances in version 4 of the Community Land Model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011MS00045 (2011).

An, S. I. et al. Global cooling hiatus driven by an AMOC overshoot in a carbon dioxide removal scenario. Earths Future 9, e2021EF002165 (2021).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002670 (2003).

Adler, R. F. et al. The version-2 global precipitation climatology project (GPCP) monthly precipitation analysis (1979–present). J. Hydrometeorol. 4, 1147–1167 (2003).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Oort, A. H. & Yienger, J. J. Observed interannual variability in the Hadley circulation and its connection to ENSO. J. Clim. 9, 2751–2767 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (NRF-2018R1A5A1024958 and RS-2024-00335725) and the Korea Environment Industry and Technology Institute (KEITI) through the Climate Change R&D Project for New Climate Regime funded by the Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE) (2022003560001). We acknowledge the World Climate Research Program, which, through its Working Group on Coupled Modeling, coordinated and promoted CMIP5 and CMIP6. We thank the climate modeling groups for producing and making their model output available, the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) for archiving the data and providing access, as well as the multiple funding agencies who support CMIP6 and ESGF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.-H.P. and S.-W.Y. contributed equally to design the research. I.-H.P. performed the data analysis and, together with S.-W.Y., interpreted the results. I.-H.P. wrote the manuscript and edited it together with S.-W.Y and S.-K.M. S,-I.A., S.-P.X, and J.S. discussed the study results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, IH., Yeh, SW., Min, SK. et al. Irreversible changes in the sea surface temperature threshold for tropical convection to CO2 forcing. Commun Earth Environ 5, 659 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01751-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01751-7