Abstract

Since the start of the satellite record in 1978, the three lowest summertime minima in Antarctic sea ice area all occurred within the last seven years and culminated in record low sea ice in austral winter 2023. During this period sea ice area was over 2 million km2 below climatology, a 5 sigma anomaly and 0.9 million km2 below the previous largest seasonal anomaly. Here we show that a fully-coupled Earth System Model nudged to observed winds reproduces the record low, and that the 2023 transition from La Niña to El Niño had minimal impact. Using an ensemble, we demonstrate that ~ 70% of the anomaly was predictable six months in advance and driven by warm Southern Ocean conditions that developed prior to 2023, with the remaining ~ 30% attributable to 2023 atmospheric circulation. An ensemble forecast correctly predicted that near record low sea ice would persist in austral winter 2024, due to persistent warm Southern Ocean conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antarctic sea ice impacts atmosphere-ocean interactions, ocean circulation, marine and coastal ecosystems, ice-sheet and ice-shelf stability, and planetary albedo. Between 1979 and 2015 Antarctic sea ice exhibited a slight increase in sea ice area (SIA), despite the increase in global mean temperature during this time1. Various mechanisms have been proposed to explain this expansion, including a strengthening Southern Annual Mode (SAM) due to ozone depletion2, changes to Southern Ocean freshening via glacial and ice-sheet melt3,4,5, an increase in precipitation6, wind circulation7 and wind-driven sea ice transport8, tropically-driven circulation trends9, and internal variability of ocean convection10. Complicating our ability to study the expansion of Antarctic SIA is the fact that most state-of-the-art Earth System Models (ESMs) when run with historical and anthropogenic forcing simulate a loss in Antarctic SIA over the satellite era11.

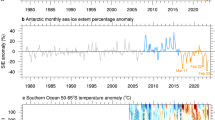

Despite the increase in SIA over 1979–2015, Antarctica has experienced a reversal in sea ice trends since 201612,13, a rapidly warming Southern Ocean14,15 and a sequence of extraordinary atmospheric heatwaves16,17,18. The reversal first began in September 2016 and developed into a record areal anomaly in austral spring and record-minimum in February 201719. Factors contributing to this event include a near-record negative SAM, warm Southern Ocean sea surface temperatures (SSTs), and a zonal wave three pattern of atmospheric circulation in early winter. These local conditions have been linked to the negative trend in the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation14, an extreme El Niño in 2015/201620, and variability in the polar stratospheric vortex21. After a slight recovery in the intervening years, a new record sea ice extent (SIE) minimum occurred in February 2022, when SIE dropped to 1.97 million km222,23,24. Only one year later, in February 2023 this record was broken with a new summer SIE minimum of 1.79 million km225,26,27. Several studies have examined the impact of a strongly positive SAM, La Niña conditions, and variability in the Amundsen Sea Low (ASL) on sea ice minimums in February 2022 and 202323,24,25. Throughout the remainder of 2023 negative SIA anomalies dramatically amplified and by the austral winter SIA was more than 2 million km2 below climatology, .9 million km2 lower than the previous largest negative seasonal SIA anomaly (Fig. 1A). While caution should be taken in interpreting such large anomalies within the context of a relatively short timeseries that may undersample true variance, analyzing 2023 in the context of the satellite record yields a 5 sigma anomaly.

Times series of observed June, July, and August (JJA) raw (million km2; left) and standardized (σ; right) SIA anomalies between 1979 and 2023 (A). Mean SIC anomalies in JJA 2023 in observations (B) and CESM2-NUDGE (C). Magenta and black contours indicate climatological average (1980–2020) and JJA 2023 sea ice edge (15% concentration), respectively. SST anomalies in JJA 2023 in observations (D) and CESM2-NUDGE (E), and mean SLP and near-surface wind anomalies in JJA 2023 in ERA5 (F) and CESM2-NUDGE (G). Stacked bar-charts show the monthly time series of SIA anomaly (million km2) for each Antarctic sector (defined in C) between 2016-01 and 2023-08 in observations (H) and CESM2-NUDGE (I). The black lines shows the total Antarctic SIA anomaly (million km2).

A growing body of literature has emerged using atmospheric nudging in ESMs, in which zonal and meridional winds are relaxed to reanalysis, to develop a process understanding of Antarctic sea ice variability and trends5,7 and Southern Ocean SST variability28. We find that a state-of-the-art ESM run between 1950 and 2023 with historical forcing and nudged to winds from reanalysis successfully reproduces the observed pattern and magnitude of sea ice concentration (SIC) anomalies in austral winter, 2023. Using this wind-nudging framework, we then conduct several experiments in order to decompose the event’s drivers: (1) we generate a 21-member ensemble forecast initialized on January 1st, 2023 to show that ~ 70% of the total SIA anomaly is attributable to warm Southern Ocean SSTs that developed by the end of 2022 and offered substantial predictability at a six month lead; (2) By removing the linear impact of 2023 ENSO conditions from atmospheric winds and re-nudging to ‘ENSO-less’ winds, we demonstrate that the transition from La Niña to El Niño in 2023 had a negligible impact on SIA anomalies; (3) we show, using an ensemble forecast, that Antarctic SIA was likely to remain near record lows in winter 2024 due to persistent warm Southern Ocean (SO) conditions.

Results

Conditions leading to sea ice loss in Austral Winter 2023

The SIA in austral winter (June, July and August; JJA) 2023 was approximately 10.5 million km2 and 2.2 million km2 below the 1980–2020 climatology, representing a 5-sigma event and the largest negative areal anomaly on record (Fig. 1A)29. Negative SIC anomalies were observed in all regions of the SO except for the Amundsen-Bellingshausen Sea, which exhibited a positive SIA anomaly of 0.2 million km2 (Fig. 1B). The most pronounced negative anomalies occurred in the Ross, Weddell, and South Indian Seas, at 0.7 million km2, 0.74 million km2, and 0.73 million km2, respectively (Fig. 1H). These regional anomalies were extreme, representing −3.0, −2.4, and −3.2 sigma events, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2). The large scale atmospheric circulation in JJA 2023 was dominated by large positive sea level pressure (SLP) anomalies in the Ross Sea and zonally characterized by a wave three pattern, with weaker positive SLP anomalies over the East Weddell and South Indian Seas (Fig. 1F). The associated anomalous anticyclonic circulation drove northward sea ice motion and cold air advection leading to positive anomalies in the Bellingshausen Sea and southward sea ice motion and warm air advection in the Eastern Ross and Weddell Seas (Fig. 2E). Past studies have shown that the impact of the zonal wave three pattern is greatest during the growth season30, when sea ice expansion is rapid and sensitive to warm-air advection and trends in winter meridional winds can help explain trends in winter SIC7. Dynamically driven anomalies may have been amplified or counteracted by warm ocean surface conditions, which can inhibit lateral and basal growth. For example, the Eastern Weddell Sea is characterized by negative SIC anomalies despite southerly surface-winds at the ice-edge (along longitudes 20W-30E in Fig. 2E/F) that would typically be associated with a northward expansion of the wintertime ice-edge. The pattern of SST anomalies matches the pattern of SIC anomalies in every sector (Fig. 1D). Warm SO surface conditions emerged as early as summer 2017 (Fig. 2A) and suggest the role of preconditioning and possible seasonal predictability (see below in Section 2.3). A detailed discussion of the storms contributing to the seasonal-mean atmospheric anomalies in the Ross and Weddell sectors has been completed in past studies29.

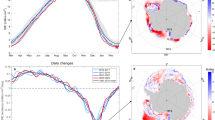

Monthly hovmoller diagrams of area-weighted SST anomalies (60∘S-50∘S) and SIC anomalies (within the climatological 1980–2020 sea ice 15% edge) in observations (A and C), and CESM2-NUDGE (B and D). Near-surface wind speeds at climatological sea ice edge and meridional-average sea ice area anomaly within climatological sea ice edge in JJA 2023 in ERA5 (E) and CESM2-NUDGE (F).

Reconstructing sea ice loss in a global climate model

Having examined the atmospheric and oceanic conditions during austral winter 2023, we turn our attention to decomposing the relative contribution of potential drivers by analyzing the nudged simulations with CESM2. CESM2-NUDGE generates SIC anomalies for winter 2023 of the same magnitude and pattern as observations (Fig. 1B, C). The CESM2-NUDGE SIA in JJA 2023 is 2.45 million km2 below the model-defined 1980–2020 climatology, with regional SIA anomalies comparable to those in observations (Fig. 1H, I). Additionally, the spatial pattern of SST anomalies is similar to observations, albeit with a slight positive circumpolar bias. The remarkable similarity between SIC and SST anomalies in CESM2-NUDGE and observations suggests that nudging may be a powerful tool for disentangling the relevant drivers of this record event.

The temporal evolution of SO SST anomalies generated in CESM2-NUDGE are similar to observations, with circumpolar warm SSTs first emerging in austral summer 2017 and persisting until present day (Fig. 2A, B). The similarity of SST variability in CESM2-NUDGE and observations (Fig. 2A, B) suggests that the recent emergence of warm surface ocean conditions may have been driven, in part, by surface wind-stress. Similar to observations, meridional near-surface winds at the ice-edge associated with the zonal-wave three pattern explain to a large degree SIC anomalies about the zonal mean in JJA 2023 (Fig. 2F). Differences between observations and CESM2-NUDGE (Fig. 2E, F) may be a result of differences in the position of the JJA 2023 ice-edge (Fig. 1B, C). We can further decompose the drivers of SIC anomalies by examining the spatial pattern of ice-area change over time (i.e. ice-area tendency), which is the sum of thermodynamic and dynamic terms:

where the dynamic contribution is driven by advection and deformation of the ice-pack and the thermodynamic contribution is driven by melt and growth processes. The spatially averaged total ice-area tendency is anomalously low during the growth season (March - August) 2023 and dominated by thermodynamic contributions (Supplementary Fig. 3G). Monthly thermodynamic ice-area tendencies are negative starting in March 2023 and remain anomalously low throughout August 2023 as the sea ice edge expands into warm SO SSTs. The spatial pattern of thermodynamic contributions is characterized by negative anomalies within the ice edge in all sectors of the SO except the Bellingshausen Sea. Dynamic contributions to ice-area changes are dominated by wind-driven sea ice advection, with positive contributions south of the ice-edge and negative contributions north of the ice-edge (Supplementary Fig. 3B). Despite the spatially averaged dynamic contribution being slightly positive during much of the growth season, dynamic tendency anomalies explain negative SIC anomalies in the Ross, Bellingshausen and Weddell Seas.

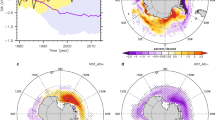

The Impact of 2023 ENSO conditions on sea ice loss

Next, we turn our attention to the impact of 2023 ENSO conditions on Antarctic sea ice in austral winter 2023. La Niña conditions first emerged in spring 2020, peaked in early 2021, and persisted until early 2023 when ENSO transitioned to an El Niño phase in March 2023 which steadily amplified throughout 2023 (Supplementary Fig. 4). It is well known that ENSO events can generate stationary Rossby Waves and influence SO atmospheric circulation and SIC31. Here, we calculate the linear impact of 2023 ENSO conditions on SO conditions as the residual between CESM2-NUDGE and CESM2-NO-ENSO-NUDGE (refer to Methods). 2023 ENSO conditions slightly amplified negative anomalies in the Ross and Weddell Seas and positive anomalies in the Bellingshausen Sea (Fig. 3). Although the impact of the transition from La Niña to El Niño on sea ice is consistent with past literature31, the total contribution is only about . 06 million km2 of the total 2.45 million km2 SIA anomaly, amounting to roughly 3% of the total anomaly in CESM2-NUDGE. The transition to El Niño acted to weaken the ASL by about 5 hPa in the Ross sea (e.g. amplify positive SLP anomalies in the Ross Sea), which amplified anomalous anticyclonic circulation and strengthened meridional sea ice advection and heat transport in the Bellingshausen and Ross Seas, respectively (Fig. 3C). The ASL transitioned from a near neutral phase in June 2023 to negative 3 sigma units by mid-September 2023. A regression analysis reveals that without ENSO conditions, the ASL would have been 1 sigma unit less negative in August and September, yet was minimally impacted by ENSO in prior months (Supplementary Fig. 15). In the Weddell sector, 2023 ENSO conditions amplified northerly surface winds, which contributed to a southward shift in the sea ice edge (Fig. 3A). We validate the results presented here with those derived from a composite analysis from CESM2-NUDGE of all periods with a positive (El Niño) or negative (La Niña) anomaly in the observed JJA Niño3.4 index greater than 1-standard deviation between 1979 and 2022 (Supplementary Fig. 5). We find that the fingerprint of ENSO on SO conditions are consistent between nudging simulation (Fig. 3) and composite results (Supplementary Fig. 5), albeit weaker in 2023, likely because 2023 ENSO conditions where neutral in early 2023.

The difference in SIC anomalies (A), SST anomalies (B), and SLP and near-surface wind anomalies (C) between CESM2-NUDGE and CESM2-NO-ENSO-NUDGE in JJA 2023. Stacked bar-charts show the monthly time series of SIA anomaly (million km2) for each Antarctic sector between 2023-01 and 2023-09 for CESM2-NUDGE (D), CESM2-NO-ENSO-NUDGE (E), and their difference (F).

The relative importance of atmosphere and ocean forcing

The emergence of warm ocean conditions prior to 2023 may be associated with persistent La Niña conditions between 2020 and 2023 (Supplementary Fig. 4), deepening of the ASL (Supplementary Fig. 4), and enhanced upwelling warm waters from below the mixed layer. While the exact cause for a warmer SO state is beyond the scope of this study, the ability of CESM2-NUDGE to reproduce the timing and magnitude of SST anomalies since 2017 by nudging zonal and meridional winds to reanalysis suggests that atmospheric circulation anomalies are a critical component of recent trends (Fig. 2A, B). Previous studies have suggested that warm SO subsurface conditions influenced SSTs via wind-driven mixing and that warm SO SSTs have been essential in driving recent Antarctic sea ice lows32. Recent studies have further argued that SO subsurface warming since 2017 may have driven Antarctic sea ice cover into a persistent low state13. In agreement with these trends, CESM2-NUDGE exhibits anomalously deep mixed-layer-depth throughout the SO in JJA 2023, suggesting enhanced SO surface-subsurface mixing (Supplementary Fig. 8). The emergence of warm SST anomalies prior to 2023 further suggests that a substantial fraction of the austral winter sea ice anomaly may have been predictable several months in advance, as SST anomalies can provide substantial predictive skill for sea ice33. In addition, as noted above, winter 2023 SIC anomalies were negative in some regions that had southerly wind anomalies during winter 2023. Southerly wind anomalies would themselves promote positive rather than negative SIC anomalies, implying a major role for ocean conditions in driving winter 2023 SIC anomalies.

To address these questions, we produce a 21-member ensemble forecast, referred to as CESM2-REFORECAST-2023, initialized on January 1, 2023 (see Methods). The CESM2-REFORECAST-2023 ensemble-mean reproduces a strong negative SIA winter 2023 anomaly that is about ~70% of the total JJA 2023 anomaly simulated in CESM2-NUDGE (−1.8 million km2 vs −2.5 million km2 in CESM2-Nudge, Fig. 4) despite nudging the ensemble members to winds from a year other than 2023 (i.e., drawn from 1980 to 2022). From this result we conclude that about ~70% of the total JJA SIA anomaly is preconditioned by the initialized anomalies in the ice-ocean on January 1 2023, which themselves may be partly attributable to atmospheric forcing prior to 2023 (Fig. 4A). The remaining ~ 30% of the total JJA 2023 anomaly (the residual or forecast error; Fig. 4I) can be attributed to atmospheric forcing during 2023, shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. Hovmoller diagrams reveal the dominant role SO SSTs played in driving the ensemble-mean SIA anomaly, as SSTs remained anomalously warm in CESM2-REFORECAST-2023, albeit slightly weaker than in CESM2-NUDGE (Fig. 4C). A regional decomposition of the SIA forecast error also reveals that atmospheric forcing during 2023 had the largest impact in the Ross and Bellingshausen sectors (Fig. 4I, J), where enhanced cyclonic circulation and the resultant sea ice advection drove a large fraction of the anomalies, consistent with the largest SLP anomalies in winter 2023 being located in the Ross and Bellingshausen sectors (Fig. 1). This decomposition confirms the multifactorial drivers that contributed to the record low Antarctic SIA in austral winter 2023.

Mean SIC anomalies in June, July, and August (JJA) 2023 in CESM2-NUDGE (A) and CESM2-REFORECAST-2023 (B). Magenta and black contours indicate climatological average (1980–2020) and JJA 2023 sea ice edge (15% concentration), respectively. SST anomalies in JJA 2023 in CESM2-NUDGE (C) and CESM2-REFORECAST-2023 (D). Monthly hovmoller diagrams of SST anomalies (60∘S-50∘S) in CESM2-NUDGE (E), and CESM2-REFORECAST-2023 (F) between 2022-01 and 2023-09. Horizontal black line indicates the start time (2023-01) when CESM2-REFORECAST-2023 branches from CESM2-NUDGE. Stacked bar-charts show the monthly time series of SIA anomaly (million km2) for each Antarctic sector between 2023-01 and 2023-09 for CESM2-NUDGE (G), CESM2-REFORECAST-2023 (H), and their difference (I) - interpreted as forecast error or the contribution of instantaneous atmospheric forcing. Regional SIA anomalies in JJA 2023 for each ensemble member in CESM2-REFORECAST-2023 (J).

A regional root-mean-squared error (RMSE) analysis of the CESM2-REFORECAST-2023 reveals compensating errors in adjacent sectors of the SO. For example, between June and August 2023, the RMSE between observations and CESM2-REFORECAST-2023 increases in the Ross sector while decreasing in the Amundsen sector (Supplementary Fig. 16). Similarly, RMSE increases in the South Indian sector while decreasing in the Weddell sector. Compensating errors may be a consequence of unrealistic ocean currents in CESM2 compared with observations, resulting in incorrect transport of sea ice anomalies, or they may be associated with meridional atmospheric circulation anomalies not captured in the forecast ensemble-mean. CESM2-NUDGE generates a negative sea ice anomaly in JJA 2023 that is .3 million km2 larger than observed, possibly due to bias SO conditions.

Forecasting 2024 austral winter sea ice conditions

Given the importance of SO SSTs in driving the record JJA 2023 SIA anomaly and the persistence of warm SO SSTs throughout 2023 (Supplementary Fig. 9), we hypothesized, at the time of submission, that SIA was likely to remain below climatology in JJA 2024. In order to examine this, we generated a forecast for 2024 initialized from CESM2-NUDGE on January 1, 2024. All 22 members in the CESM2-FORECAST-2024 ensemble forecast a negative wintertime SIA anomaly (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14), with a forecast range of −1.8 million to −2.6 million km2 and a forecast mean of −2.15 million km2 (Fig. 5). The ensemble-mean forecast exhibits negative SIA anomalies in all sectors of the SO (Fig. 5), however, individual members of the ensemble forecast positive sea ice anomalies in various sectors of the Southern Ocean (Supplementary Fig. 9). The largest ensemble spread in the forecasts are in the Weddell sector, suggesting observed sea ice conditions are likely sensitive to the atmospheric circulation emergent in 2024. In fact, the ensemble-mean SIA forecast for JJA 2024 is roughly .35 million km2 more negative than the ensemble-mean forecast for JJA 2023 generated by CESM2-REFORECAST-2023. This may result from the fact that warm SST anomalies in the SO, which were already anomalously warm by the end of 2022, have amplified throughout 2023 (Supplementary Fig. 9). Finally, if the atmospheric circulation that occurred in 2023 repeated itself in 2024, we find that SIA in JJA 2024 would be 2.6 million km2 below climatology, which is the lowest SIA forecast within the CESM2-FORECAST-2024 ensemble, and more negative than the record CESM2-NUDGE anomaly in JJA 2023, consistent with our finding that winds from 2023 amplified the SIA anomalies in 2023.

Ensemble-mean SIC (A), SST (B) and SLP and wind speed (C) anomalies in JJA 2024 from CESM2-FORECAST-2024. In top row, magenta and black contours indicate climatological average (1980–2020) and JJA 2024 sea ice edge (15% concentration). Remaining spatial panels show the the difference between the ensemble members and ensemble-mean nudged to winds from 1998 (ensemble member with minimum negative SIA in JJA 2024), 2007 (ensemble member with maximum negative SIA in JJA 2024) and 2023 (right column) for each spatial field. Timeseries of SIA anomalies from CESM2-FORECAST-2024 (D), and regional SIA anomalies in JJA 2024 for each member in CESM2-FORECAST-2024 (E).

The observed JJA 2024 SIA anomaly is approximately −1.5 million km2, the second lowest JJA value on record after 2023, and still an extremely low SIA year in the context of 1979–2022. This value is slightly greater than the range of the CESM2-FORECAST-2024 ensemble. This may have been due to the atmosphere during 2024 being more favorable to sea ice growth than any of the forecast ensemble members, and forecast errors in the initial conditions or physics, such as over-estimated ocean warmth by the end of 2023 in CESM2-NUDGE relative to observations. The JJA 2024 sea ice conditions are characterized by positive sea ice anomalies in the Western Weddell Sea and negative sea ice anomalies in the Eastern Weddell, Amundsen, Ross, and Eastern Pacific Seas. This pattern of anomalies is quite similar to the anomalies generated by several ensemble members (1980 and 1989; Supplementary Fig. 17). The relative accuracy of CESM2-FORECAST-2024 and the fact that this forecast was generated 6-months prior to JJA 2024, strongly motivate further study and development of this forecasting technique.

Conclusions

The largest recorded negative Antarctic SIA anomaly in the satellite era occurred in austral winter 2023. The record sea ice conditions resulted from the combination of a fast response to anomalous atmospheric circulation forcing in 2023 and a slower, lagged response to ocean SST anomalies that emerged prior to 2023. The event had substantial predictability at a six-to-eight month leadtime, was weakly impacted by 2023 ENSO conditions, and is shown to persist in winter 2024.

To the best of our knowledge, the tools presented here are a novel use of the circulation nudging framework in a fully coupled model. We demonstrate that these techniques can be used to study the impact of large-scale modes of variability (e.g. ENSO) on remote conditions (e.g. Antarctic sea ice) by removing via regression the relationship between the target variable and mode of interest. The application of the atmospheric wind nudging framework as a tool for studying seasonal sea ice predictability also paves the way for further development of sea ice forecasting systems, which for Antarctic sea ice have historically shown poor skill at seasonal timescales34.

Several studies have argued that the reversal of Antarctic SIA trends and the warming in the SO is indicative of a regime-shift into a new, low Antarctic sea ice mean-state.13,35,36. While it is likely too soon to robustly determine a permanent regime-shift, our successful forecast that Antarctic sea ice was likely to remain near record lows in winter 2024 builds upon this concern and highlights the need for further investigation into SO surface and subsurface temperature variability, and to further understand the attribution of recent SO warming - is it due to internal variability or signs of a forced warming response?

Methods

Observations, reanalysis, and indices

Simulations are evaluated with satellite-derived passive microwave measurements of sea ice concentrations in the Southern Ocean from the NSIDC Climate Data Record version 4 on a 25km x 25km polar stereographic grid37, and ERA5 reanalysis for all other atmospheric and oceanic conditions38. All data are regridded to a common 1∘ global resolution before analysis. All analysis of sea ice coverage is reported in sea ice area, rather than sea ice extent39, because Antarctic wintertime sea ice does not suffer data quality issues such as a `pole hole’ or melt pond coverage that in the Arctic justify the use of sea ice extent.

We calculate the Amundsen Sea Low location (latitude and longitude) and central pressure between January 1979 and August 202340. The Niño3.4 time series that we use is from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/correlation/nina34.data. We calculate the Southern Annual Mode index following established methods41.

Nudging CESM2.1 to historical winds

We use the Community Earth System Model version 2.1 (CESM2.1) from the National Center for Atmospheric Research with the Community Atmosphere Model version 6 (CAM6)42. Simulations are forced with CMIP6 historical forcing through 2014 and thereafter with SSP3.7 forcing. All components have a nominal 1∘ resolution. Model output is regridded to the same grid as used for reanalysis and observations.

In all nudging simulations (Supplementary Table S1), we nudge zonal (U) and meridional (V) winds to 6-hourly ERA5 U and V from 850 hPa to the top of the model between 55∘S and 80∘S following standard methodology7. The wind-nudging is performed by relaxing the winds as follows:

where x is the model state-vector being nudged (i.e. U or V), F(x) is the model-calculated tendency of x, and Fnudge is the relaxation tendency, which is proportional to the difference between xT(tnext), the target state-vector at the next time step, and x(t), the model state-vector at the current time-step. α is the nudging coefficient which is set to 1 between 55∘S and 80∘S and smoothly transitions to 0 outside of the nudging domain border. CESM2-NUDGE requires approximately 30-years to adjust to a stable Antarctic sea ice state (Supplementary Fig. 1). For this reason, nudging is initiated in 1950 and all model output prior to 1980 is rejected from analysis.

Our baseline simulation, initialized on January 1, 1950, and integrated through December 31, 2023, is denoted as CESM2-NUDGE (Supplementary Table S1).

Nudging CESM2.1 to ‘ENSO-less’ 2023 winds

An additional nudging simulation branches from CESM2-NUDGE on January 1st, 2023 and is nudged to adjusted observed winds over January 1 2023 - August 31 2023 where the observed linear relationship between Niño 3.4 and U and V is removed. In this experiment the target wind anomalies are updated as follows:

where \({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}^{{\prime} }(t)\) is the anomaly target state-vector at time t, \(\frac{d{{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{T}^{{\prime} }}{d{{{\rm{Ni}}}}\tilde{{{{\rm{n}}}}}{{{\rm{o}}}}3.{4}^{{\prime} }}\) is the instantaneous daily regression coefficient between the time series of Niño3.4 anomalies and target state-vector anomalies, and Niño\(3.{4}^{{\prime} }(t)\) is the Niño3.4 anomaly at the target time t. The updated target state-vector anomaly with the linear impact of ENSO removed, \({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{{{{\rm{T}}}},{{{\rm{NO}}}}\_{{{\rm{ENSO}}}}}^{{\prime} }(t)\), is then added to \(\overline{{{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}}\), the daily climatology of the target state-vector. Regression coefficients are calculated using monthly time series of the Niño\(3.{4}^{{\prime} }(t)\) index and target state-vector and are linearly interpolated to a daily resolution. Regression coefficients and all anomalies are calculated using a reference period between January 1, 1980 and December 31, 2022. The simulation that is nudged to historical winds with ENSO removed is denoted as CESM2-NO-ENSO-NUDGE (Supplementary Table S1).

Reforecasting the austral winter 2023 by nudging CESM2.1

In order to examine the predictability of the winter 2023 Antarctic SIA anomaly and further understand its mechanisms, we generate a 21-member forecast ensemble initialized from CESM2-NUDGE on January 1, 2023, and run for a year. In order to sample different atmospheric conditions, each ensemble member is nudged to target winds taken from a random year between 1979 and 2022 (Supplementary Table S1). We nudge to winds from previous years rather than allowing the ensemble members to free-run in order to estimate the predictability of the winter 2023 SIA anomaly without the influence of climate drift. A similar sea ice forecast technique is used by ice-ocean models that use past years’ atmospheric boundary conditions to evolve the model forwards (e.g., ref. 43). Model simulations that are nudged to historical winds from past years are referred to as CESM2-REFORECAST-2023. We consider these experiments ‘forecasts’ because they could have been generated on January 1st, 2023, i.e., at least six months before austral winter 2023.

Forecasting the austral winter 2024 by nudging CESM2.1

Finally, the skillful results of CESM2-REFORECAST-2023 encourage us to generate a sea ice forecast for austral winter 2024. Like the 2023 forecast, we generate a 22-member ensemble initialized from CESM2-NUDGE on January 1, 2024. Each ensemble member runs until December 31, 2024 and is nudged to past winds taken from the same random years as CESM2-REFORECAST-2023, with an additional ensemble member that is nudged to winds from 2023, in order to further examine the impact of the atmospheric circulation in 2023 in driving SIA anomalies. These experiments are referred to as CESM2-FORECAST-2024.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The ECMWF fifth generation reanalysis (ERA5) data38 are available at https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.f17050d7. Satellite derived passive microwave measurements of sea ice concentrations from the NSIDC Climate Data Record version 4 on a 25km x 25km polar stereographic grid37 are available at https://nsidc.org/data/g02202/versions/444. The Niño3.4 timeseries can be found at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/correlation/nina34.data, and the Southern Annual Mode index41 is available at https://legacy.bas.ac.uk/met/gjma/sam.html. Instructions to run CESM2.1 simulations can be found at https://escomp.github.io/CESM/versions/cesm2.1/html/downloading_cesm.html. Near-Real-Time DMSP SSMIS Daily Polar Gridded Sea Ice Concentrations, Version 2 used in Supplementary Fig. 17 available at https://nsidc.org/data/nsidc-0081/versions/2or https://n5eil01u.ecs.nsidc.org/PM/NSIDC-0081.002/. The data to reproduce the main text figures are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1382153345.

Code availability

The code used for all analyses presented in this manuscript is publicly available at https://github.com/zacespinosa/SI-Antarcticand https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1382138946. Code used to generate the Amundsen Sea low location and pressure can be found at https://github.com/scotthosking/amundsen-sea-low-index/.

References

Comiso, J. C. et al. Positive Trend in the Antarctic Sea Ice Cover and Associated Changes in Surface Temperature. J. Clim. 30, 2251–2267 (2017).

Ferreira, D., Marshall, J., Bitz, C. M., Solomon, S. & Plumb, A. Antarctic Ocean and Sea Ice Response to Ozone Depletion: A Two-Time-Scale Problem. J. Clim. 28, 1206–1226 (2015).

Dong, Y., Pauling, A. G., Sadai, S. & Armour, K. C. Antarctic Ice-Sheet Meltwater Reduces Transient Warming and Climate Sensitivity Through the Sea-Surface Temperature Pattern Effect. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, 2022–101249 (2022).

Rye, C. D. et al. Antarctic Glacial Melt as a Driver of Recent Southern Ocean Climate Trends. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, 2019–086892 (2020).

Roach, L. A. et al. Winds and meltwater together lead to southern ocean surface cooling and sea ice expansion. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, 2023–105948 (2023).

Liu, J. & Curry, J. A. Accelerated warming of the Southern Ocean and its impacts on the hydrological cycle and sea ice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 107, 14987–14992 (2010).

Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E., Roach, L. A., Donohoe, A. & Ding, Q. Impact of Winds and Southern Ocean SSTs on Antarctic Sea Ice Trends and Variability. J. Clim. 34, 949–965 (2021).

Sun, S. & Eisenman, I. Observed Antarctic sea ice expansion reproduced in a climate model after correcting biases in sea ice drift velocity. Nat. Commun. 12, 1060 (2021).

Chung, E.-S. et al. Antarctic sea-ice expansion and Southern Ocean cooling linked to tropical variability. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 461–468 (2022).

Zhang, L., Delworth, T. L., Cooke, W. & Yang, X. Natural variability of Southern Ocean convection as a driver of observed climate trends. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 59–65 (2019).

Roach, L.A. et al. Antarctic Sea Ice Area in CMIP6. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47(9), e2019GL086729 (2020).

Parkinson, C. L. A 40-y record reveals gradual Antarctic sea ice increases followed by decreases at rates far exceeding the rates seen in the Arctic. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 116, 14414–14423 (2019).

Purich, A. & Doddridge, E. W. Record low Antarctic sea ice coverage indicates a new sea ice state. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 1–9 (2023).

Meehl, G. A. et al. Sustained ocean changes contributed to sudden Antarctic sea ice retreat in late 2016. Nat. Commun. 10, 14 (2019).

Wilson, E. A., Bonan, D. B., Thompson, A. F., Armstrong, N. & Riser, S. C. Mechanisms for Abrupt Summertime Circumpolar Surface Warming in the Southern Ocean. J. Clim. 36, 7025–7039 (2023).

Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E., Cox, T., Espinosa, Z. I. & Donohoe, A. The largest ever recorded heatwave—characteristics and attribution of the antarctic heatwave of march 2022. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, 2023–104910 (2023).

Gorodetskaya, I. V. et al. Record-high antarctic peninsula temperatures and surface melt in february 2022: a compound event with an intense atmospheric river. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 202 (2023).

Wille, J. D. et al. The extraordinary march 2022 east antarctica “heat” wave. part i: observations and meteorological drivers. J. Clim. 37, 757–778 (2024).

Turner, J. et al. Unprecedented springtime retreat of Antarctic sea ice in 2016. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 6868–6875 (2017).

Stuecker, M. F., Bitz, C. M. & Armour, K. C. Conditions leading to the unprecedented low Antarctic sea ice extent during the 2016 austral spring season: RECORD LOW 2016 ANTARCTIC SEA ICE EXTENT. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 9008–9019 (2017).

Wang, G. et al. Compounding tropical and stratospheric forcing of the record low Antarctic sea-ice in 2016. Nat. Commun. 10, 13 (2019).

Raphael, M. N. & Handcock, M. S. A new record minimum for Antarctic sea ice. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 215–216 (2022).

Zhang, C., Li, S. Causes of the record-low Antarctic sea-ice in austral summer 2022. Atmos. Oceanic Sci. Lett. 16, 100353 (2023)

Turner, J. et al. Record Low Antarctic Sea Ice Cover in February 2022. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, 2022–098904 (2022).

Cordero, R. R. et al. Signature of the stratosphere–troposphere coupling on recent record-breaking antarctic sea-ice anomalies. Cryosphere 17, 4995–5006 (2023).

Gilbert, E. & Holmes, C. 2023’s antarctic sea ice extent is the lowest on record. Weather 79, 46–51 (2024).

Roach, L. A. & Meier, W. N. Sea ice in 2023. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 235–237 (2024).

Dong, Y., Armour, K. C., Battisti, D. S. & Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E. Two-way teleconnections between the southern ocean and the tropical pacific via a dynamic feedback. J. Clim. 35, 6267–6282 (2022).

Jena, B. et al. Evolution of antarctic sea ice ahead of the record low annual maximum extent in september 2023. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, 2023–107561 (2024).

Raphael, M.N. The influence of atmospheric zonal wave three on Antarctic sea ice variability. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 112(D12), https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JD007852 (2007).

Li, X. et al. Tropical teleconnection impacts on Antarctic climate changes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 680–698 (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. The relative role of the subsurface Southern Ocean in driving negative Antarctic Sea ice extent anomalies in 2016–2021. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 1–9 (2022).

Holland, M. M., Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E., Kay, J. & Vavrus, S. Initial-value predictability of antarctic sea ice in the community climate system model 3. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 2121–2124 (2013).

Massonnet, F. et al. Sipn south: six years of coordinated seasonal antarctic sea ice predictions. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1148899 (2023).

Schroeter, S., O’Kane, T. J. & Sandery, P. A. Antarctic sea ice regime shift associated with decreasing zonal symmetry in the Southern Annular Mode. Cryosphere 17, 701–717 (2023).

Eayrs, C., Li, X., Raphael, M. N. & Holland, D. M. Rapid decline in Antarctic sea ice in recent years hints at future change. Nat. Geosci. 14, 460–464 (2021).

Meier, W.N., Fetterer, F., K., W.A., Stewart, J.S. NOAA/NSIDC Climate Data Record of Passive Microwave Sea Ice Concentration, Version 4. National Snow and Ice Data Center, https://doi.org/10.7265/efmz-2t65 (2021).

Hersbach, H. et al. The era5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorological Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Matthews, J. L., Peng, G., Meier, W. N. & Brown, O. Sensitivity of arctic sea ice extent to sea ice concentration threshold choice and its implication to ice coverage decadal trends and statistical projections. Remote Sens. 12, 807 (2020).

Hosking, J. S., Orr, A., Bracegirdle, T. J. & Turner, J. Future circulation changes off west antarctica: Sensitivity of the amundsen sea low to projected anthropogenic forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 367–376 (2016).

Marshall, G. J. Trends in the southern annular mode from observations and reanalyses. J. Clim. 16, 4134–4143 (2003).

Danabasoglu, G. et al. The community earth system model version 2 (cesm2). J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, 2019–001916 (2020).

Lindsay, R. C. et al. Seasonal forecasts of Arctic sea ice initialized with observations of ice thickness. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L21502 (2012).

Meier, W. et al. NOAA/NSIDC Climate Data Record of Passive Microwave Sea Ice Concentration. (G02202, Version 4). https://doi.org/10.7265/efmz-2t65.

Espinosa, Z.I. Data for “Understanding the Drivers and Predictability of Record Low Antarctic Sea Ice in Austral Winter 2023". https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13821533.

Espinosa, Z. zacespinosa/SI-Antarctic: Code for Publication. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13821389.

Acknowledgements

Z.E. would like to thank the following software communities for making their software publicly available: xsearch (https://github.com/pochedls/xsearch), xarrays (https://docs.xarray.dev/en/stable/), xskillscore (https://xskillscore.readthedocs.io/en/stable/index.html), SciPy (https://scipy.org/), and xCDAT (https://xcdat.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html). E.B.-W. was supported through National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs through award 2233016. C.M.B. is supported by the National Science Foundation OPP-2237964. Z.E. is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Advanced Scientific Computing Research, Department of Energy Computational Science Graduate Fellowship under Award Number(s) DE-SC0023112. This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. This work uses ERA5 data, which contains modified Copernicus Climate Change Service information 2020. Neither the European Commission nor ECMWF is responsible for any use that may be made of the Copernicus information or data it contains. We would also like to acknowledge high-performance computing support from Cheyenne (https://doi.org/10.5065/D6RX99HX) provided by NCAR’s Computational and Information Systems Laboratory, sponsored by the National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zachary I. Espinosa completed all data preparation, ran the simulations, analyzed the results, wrote the manuscript, and completed paper revisions. Edward Blanchard-Wrigglesworth wrote and revised the manuscript, helped with analysis and interpretation of the results, aided with conceptualization, and helped with paper revisions. Cecilia M. Bitz revised the manuscript, helped with interpretation of the results, aided with conceptualization, and reviewed paper revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Babula Jena and the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Espinosa, Z.I., Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E. & Bitz, C.M. Understanding the drivers and predictability of record low Antarctic sea ice in austral winter 2023. Commun Earth Environ 5, 723 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01772-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01772-2

This article is cited by

-

Atmosphere-ocean driven glacial changes in West Graham Land, Antarctic Peninsula

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Pacific sub-decadal sea surface temperature variations contributed to recent Antarctic Sea ice decline trend

Nature Communications (2025)

-

The key role of the Southern Annular Mode during the sea-ice maximum for Antarctic sea ice and its recent loss

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Drivers of summer Antarctic sea-ice extent at interannual time scale in CMIP6 large ensembles based on information flow

Climate Dynamics (2025)

-

Combined Influences of Atmospheric Precursors on Antarctic Sea Ice and Its Record Low in February 2023

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences (2025)