Abstract

The success of coral restoration for the critically endangered Acropora palmata is understudied. Here, we examined how habitat and coral microbiomes influenced survivorship in four genets of A. palmata outplanted in three reefs. A. palmata microbiomes were correlated to reef and habitat and minimally to coral genet. Carysfort Reef exhibited the lowest survivorship which correlated to lower current velocity and a higher relative abundance of Rhodobacterales in A. palmata. Higher survivorship was present at Pickles Reef which correlated to the highest current velocity, and at North Dry Rocks with the shallowest outplant depth. Habitat factors driven by time of year such as higher levels of nitrate, nitrite, and temperature also correlated with a relative increase in a putative pathogen, Alteromonadales, and a decrease in an uncharacterized core bacteria. We suggest outplanting at sites with high currents, lower depths, and at lower concentrations of nitrate/nitrite to increase A. palmata survivorship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tropical coral reefs globally are facing declines, with estimates suggesting a potential 40% decrease in coral cover by 2100 due to an increase in global average temperatures1. In the Caribbean, the Acropora palmata coral population alone has decreased by over 80% since the 1950s2, resulting in A. palmata being classified as threatened under the United States Endangered Species Act3 and critically endangered under the International Union for Conservation of Nature4. A. palmata, once dominant in the reef crest zones of the Caribbean, played a crucial role in providing structural support and a habitat for many reef species due to its complex branching morphology2. The decline of this species has led to the structural loss of Caribbean reefs, adversely affecting ecosystem health5, and replacement by other benthic species like sponges, macroalgae, and non-reef-building organisms6. Other factors contributing to the decline of A. palmata prevalence include overfishing7, nutrient pollution2, disease outbreaks8, storm damage9, predation9, and the increasing frequency and duration of marine heat waves10.

In response to the decline in coral cover, restoration practitioners have implemented strategies such as coral outplanting, to increase coral cover and restore ecosystem health10,11. Asexual coral restoration is the most common method to repopulate coral reefs after disturbances or reef degradation. Coral colonies are fragmented to induce faster growth and are allowed to grow in coral nurseries. From nurseries, corals are outplanted on coral reefs and attached using adhesive materials such as epoxy and cement12. An objective of coral outplanting is to enhance genetic diversity, improve fitness, and ensure adaptability to environmental stressors of individual coral species13. This process entails the identification of coral genotypes and their strategic dispersal across coral reefs14 with ecological, economic, and cultural significance13.

The success of coral health and outplant success relies on various factors, including genotypes15, location11,16,17, and environmental conditions17,18,19,20,21. One area noted to play a pivotal role in coral health is the coral holobiont22,23. The coral holobiont consists of the coral host, the obligate symbiotic dinoflagellate, and other microorganisms (bacteria, archaea, viruses, fungi, and protists)24,25,26. The natural variation of microbiomes within corals is proposed as key to stress adaptation27. For example, coral microbiomes in A. palmata containing the bacterium Myxococcales were associated with disease-resistant phenotypes28, while A. palmata with Endozoicomonas demonstrated increased tolerance to bleaching29. Environmental factors can also lead to changes in the A. palmata microbiome, for example, regions where A. palmata experienced periodic upwelling had a distinct microbiome community and higher coral growth and survivorship19. Examples of varied outplant success have been linked to habitat conditions18,30,31. However, our understanding of the relationships between the microbiome and the habitat of A. palmata, as well as how these factors interact and influence outplant success, is limited.

The mechanisms governing phenotypic variations in coral outplants are not entirely clear. Since coral-associated bacterial communities and coral genetic responses are more likely to vary across genotypes this suggests they play a greater role in driving differences in survivorship compared to the symbiont community, which remains largely stable. For example, ~70% of A. palmata host a single strain of their symbiotic dinoflagellates, Symbiodinium “fitti”32. Instead, the coral’s genetics such as epigenetic mechanisms32 and alterations to the bacteria and archaea community (hereafter referred to as the microbiome) show evidence that they play a role in the coral’s stress response29. Previous research on Acropora millepora in the Great Barrier Reef has shown that the microbiome varies during outplanting23. Thus, we hypothesize that the microbiome plays a role in the success of the outplanting process.

This study aims to investigate the relationship between coral genet, reef habitat, and how coral microbial communities may impact the success of outplanted A. palmata. We hypothesize that genotype, habitat, and microbial community play a role in outplant survivorship and specific microbial taxa will be associated with A. palmata survivorship. To test this, in 2019, we examined four genets (i.e., a collection of clonally produced individuals that share the same multilocus at all loci33) on three coral reefs in the upper Florida Keys that are actively being restored. Habitat data collection included the assessment of dissolved inorganic nutrient concentration, deployment of instruments to gather ocean current data, and remotely sensed satellite sea surface temperature and chlorophyll-a concentrations derived from ocean color radiometric measurements. We used 16S rRNA gene sequencing to characterize coral-associated microbial communities and correlated microbiome indices to outplant fragment performance. Overall, we found that environmental factors such as shallow depth and increased current velocity correlated with higher survivorship. The relative abundance of bacteria in the order Rhodobacterales (within coral tissues) was inversely proportional to outplant survivorship. Our results provide evidence that both the habitat and microbiome correlate with A. palmata outplant survivorship, and are useful for informing decision-making on reef restoration site selection to increase survivorship.

Material and methods

Field sites

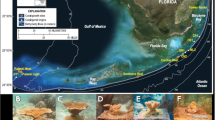

Field sampling was conducted at three active Coral Restoration Foundation sites within the upper Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. The coral reefs included Carysfort Reef ([CF] 25.2209, −80.2102, transect 49 m), North Dry Rocks Reef ([NDR], 25.1304, −80.2940, 2 transects 35 m and 8 m), and Pickles Reef ([PR] 24.9845, −80.4164, transect 48 m; Fig. 1a). CF lies northernmost, NDR in the middle, and PI the southernmost coral reef, with CF and PR being 32 km apart. Acropora palmata fragments were outplanted in March 2018 by the Coral Restoration Foundation and we tracked four coral genets: CN2, CN4, ML2, and HS1. These genets were selected because they were used in our previous disease studies34,35. Coral fragments belonging to a single genet were attached to the substrate using two-part marine epoxy in clusters (or ramets33) of six to seven with a cow-tag containing a unique cluster identifier nailed into adjacent coral reef substrate. Fragments within the clusters were typically placed about <20 cm apart to promote fusing the coral fragments within a cluster over time. Fragments within each cow-tagged cluster were assigned unique numeric identifiers and photographed with their assigned number or letter (Fig. 1b). The depth (ft) of each cluster was measured using a dive computer attached to a dive weight and placed on the substrate within or immediately adjacent to the cluster of fragments. The depth readings were collected using the same dive computer within a 60-min time frame to eliminate within-site differences due to tidal fluctuations.

a A map of South Florida with the three sampled coral reefs (Carysfort Reef [CF], North Dry Rocks [NDR], and Pickles Reef [PR]) denoted by white circles. The map shows the sea surface temperature (SST) variance from 2003 to 2023. The bathymetry contours (in white) correspond to the 5, 30, 100, and 200 m isobaths. b A representative photograph of Acropora palmata of a single genet in a cluster labeled with a number or letter that was used to identify the same colony throughout the project. The scale next to the cluster is in centimeters. c Schematic of sampling scheme. The timeline represents the four sampling timepoints. The date of sampling is colored by the cooler dry season in Feb.-Mar., and Nov (navy text), and the warmer wet season of Jun.-Jul., and Sept. (red text). The blue rectangle represents a bird’s eye view representation of an outplant transect. Circles represent a single cluster within the transect. The clusters colored in blue represent genets outplanted but not analyzed in this study and may represent different genets. The blue tags represent three fragments selected for repeat sampling, and white tags are for fragments within the cluster that were not sampled. The “n = ” corresponds to only tissue samples used in microbiome analysis after quality control.

Surveys for survivorship

This work was conducted under permit FKNMS-2018-117. To determine survivorship across time and study site an initial survey was conducted to assign each fragment within a cluster with a unique number or letter so that individual fragments could be tracked throughout the nine surveys conducted at 2-3 month intervals (Fig. 1b). During subsequent surveys, contact sheets containing photos of each cluster depicting the fragment’s assigned number/letter designation were brought into the field for fragment re-identification. At each survey, a weighted number/letter marker was placed next to the corresponding fragment as identified from the contact sheet (Fig. 1b). Each cluster was photographed with a scale bar (Fig. 1b). All fragments within the cluster were scored as live or dead. A fragment was considered live if any part of the fragment retained live tissue at the time of the surveys, and dead if no live tissue remained on the fragment. These data were used to estimate survivorship across all fragments from June of 2018 through December of 2019.

To identify survivorship differences among genotypes, and coral reefs, the Cox proportional hazards model was implemented using the Survival R v4.3.2 package 3.5.736,37, with CN2 and CF used as references, respectively. Time was measured from the first survivorship survey conducted on June 21, 2018 (day 0) until an event, such as coral death, or the conclusion of the survey on day 532, December 5, 2019. Survivorship rates were generated for sampled fragments for correlations between microbiome indices (see “Statistical analysis for bioinformatic data”). Survivorship rates were calculated by grouping genet, coral reef, and date of survey, adding up the total count of live fragments, and dividing this by the total on Day 0 to get a percentage survivorship for each genet in a particular coral reef during a specific day of collections.

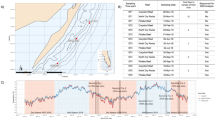

Satellite sea surface temperature and chlorophyll-a

Habitat data was collected throughout the study to determine how these factors may impact coral survivorship and coral microbiomes. Satellite sea surface temperature (SST) and chlorophyll-a concentration (Chl-a) observations were retrieved from each sampled coral reef from January 1st through December 31st, 2019. Average SST time series with one standard deviation envelopes encompassing the sampling period were generated for each coral reef site by extracting SST values from 10 × 10 pixels boxes centered at each station’s longitude and latitude values using daily version 4 Multiscale Ultrahigh Resolution (MUR) L4 analysis derived from the nighttime Group for High-Resolution Sea Surface Temperature (GHRSST38) available on NOAA Environmental Research Division’s Data Access Program (ERDDAP) servers at ~1 km pixel resolution (Dataset ID: jplMURSST41). Time series of Chl-a were created similarly with 2 × 2 pixels boxes using 8-day and monthly composites of Chl-a concentration at ~4 km pixel resolution from the MODIS-Aqua sensor produced by the Ocean Biology Processing Group at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (ERDDAP Dataset ID: erdMH1chla8day_R202SQ). Average SST and Chl-a were also calculated for each field sampling event. Due to high data patchiness from cloud masking in daily ocean color retrievals, 8-day averages of Chl-a were computed for each coral reef seven days before the sampling event including the day of sampling. For SST the averages on the day of sampling were used. These values were subsequently used in statistical analysis with microbial data. The SST data was log2 and Chla-concentrations log10 transformed. The data was visually inspected for normality using a barplot and Q-Q plot and homogeneity of variance was assessed with residual plots. As assumptions were met, a one-way ANOVA (R v4.3.2 function aov) was used to test environmental conditions between reefs and if significant Tukeys HSD pairwise comparison was used.

Tilt current meters

Tilt Current meters ([TCMs], Lowell, East Falmouth, MA) were deployed on 12” X 12” inch paving stones anchored at each reef and water velocity was measured every 15 min. A flexible tether was then used to link the TCM and paving stone, which allowed the TCM to respond to water flow. Figure 1c shows a depiction of how TCMs were placed throughout the transect, with one at each end and at the middle of the outplant transect (Supplementary Data 1). TCMs were left on the coral reef for the duration of the study and swapped about every three months for battery change and cleaning. The Lowell Domino software was used to configure the TCM for deployment and extract the data as CSV files. Once the data was extracted, only speeds lower than 25 cm/s were analyzed as higher speeds were likely artifacts from biofouling or displacement from a vertical position. Since some files failed to be extracted from TCM, the current velocity was averaged by month of collection to reduce gaps in the data. The data were log-transformed to reduce the data skew and increase normality. The data was visually assessed for normality using bar plots and Q-Q plots, while homogeneity of variance was evaluated with residual plots. Since the assumptions were met, ANOVA was conducted to compare and if significant differences were found, Tukey’s HSD pairwise comparison was performed.

Nutrients

To evaluate how common nutrients measured in coastal water quality monitoring may affect coral outplant survivorship and microbiome changes, four 50 mL seawater samples were collected per coral reef for dissolved inorganic nutrient analysis during each sampling event. Using 50 mL conical tubes two samples were collected above a coral head within the outplant transect, and two additional samples were gathered at the surface. Seawater samples were filtered into 50 mL conical tubes using a 0.45 µm filter with a sterile syringe. With a transfer pipette 0.1 mL of chloroform was added for preservation and then placed on ice until stored at the NOAA Atlantic Oceanographic Meteorological Laboratory’s nutrient lab. Nutrient samples were analyzed less than two weeks after collection using a SEAL Analytical AA3 continuous flow autoanalyzer for phosphate (PO43-), nitrate (NO3−), nitrite (NO2−), and silicic acid (H4SiO4). Nitrite was determined by diazotizing the sample with sulfanilamide and coupling it with N-1 naphthyl ethylenediamine dihydrochloride to form an azo dye. The color produced is measured at 540 nm39. Samples for nitrate analysis were passed through a copper-coated cadmium column, which reduced nitrate to nitrite, together with nitrite in the original sample this procedure determined the total concentration of nitrite plus nitrate. Nitrate concentrations were calculated as the difference40. Phosphate was determined by reacting the sample with molybdic acid to form phosphomolybdic acid. This complex was subsequently reduced with hydrazine, and the absorbance of the resulting phosphomolybdenum was measured at 836 nm41. Silicic acid was analyzed by reacting with ammonium molybdate in an acidic solution to form β-molybdosilicic acid, which was then reduced with ascorbic acid to form molybdenum blue. The absorbance of the molybdenum blue was measured at 660 nm39.

The preparation of nutrient standards followed protocols outlined in the GO-SHIP repeat hydrographic program42. The mixed standard solutions were verified against Nutrient Certified Reference Materials in seawater42,43. The nutrient data were tested for differences in coral reef and months of sampling using a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test and pairwise comparisons were adjusted with a Bonferroni correction on R v4.3.2.

Coral sampling

To assess the microbiome of genotypes through time and between coral reefs, in 2019, coral tissue samples were collected at four time points: February-March, June-July, September, and November (Fig. 1c. and Supplementary Table 1). The first sampling time point was one year after the initial outplanting in March 2018. Due to time and weather constraints, it was not possible to sample all three coral reef sites in a single day, but each coral reef was sampled within 7 days of each other. Three clusters (representing one genet) were selected per genet in each coral reef, and within each cluster, three fragments were randomly selected for sampling (Fig. 1c). The same fragments were sampled over time. Self Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus was used to collect tissue samples from outplanted A. palmata coral clusters. Tissue samples, approximately 0.5 × 0.5 cm in size, were collected from three fragments within each cluster using a hammer and chisel, placed in a pre-labeled Ziploc bag, and returned to the boat. Samples were transferred using bleach and ethanol-sterilized tweezers to 2 mL cryovial tubes. Samples that could not fit into tubes were further fragmented with bleach and ethanol-sterilized bone cutters. The samples were placed in tubes pre-filled with 1.5 mL of RNAlater, placed on ice, and transported to a −80 °C freezer at the University of Miami until processing.

DNA extractions and high-throughput amplicon sequencing

To characterize the microbiome community of A. palmata, 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing analysis was conducted on four coral genets, CN2, CN4, ML2, and HS1 (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 1). DNA extractions were performed using the MagBead DNA/RNA kit (Zymo Research, CA) and the Kingfisher Flex instrument (ThermoFisher Scientific, MA)44. Samples, which included mucus, tissue, and skeleton were transferred to a Zymo Bead Beating Tube containing 0.1 mm and 0.5 mm beads, and 750 µl of DNA/RNA shield (Zymo Research, CA). Vortexing of a maximum of 24 tubes occurred for 40 min at maximum speed in a horizontal position. Following vortexing, each tube was centrifuged for 30 s at 14,000 g, and 200 µl of the supernatant was transferred to a Kingfisher DeepWell Plate. The supernatant consisted mostly of the tissue and mucus as the bare skeleton was left intact after homogenization. Subsequently, 10 µl of Proteinase K was added to each well, thoroughly mixed, and incubated at room temperature. After 30 min, 500 µl of DNA/RNA lysis buffer and 30 µl of Zymo MagBinding beads were added into each well. The sample and reagent plates were loaded onto the Kingfisher instrument for DNA extraction. Finally, DNA was eluted in water provided by the kit and was sealed and stored at −80 °C for downstream processing.

The extracted DNA was PCR amplified with 16S rRNA gene Variable 4 primers45. Each sample was processed in a 50 µl reaction and included 2x Platinum Hot Start PCR Master Mix (20 µl; Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA), PCR-grade water (26 µl), 10 µM reverse primer (10 µl), 10 µM forward barcoded primer (10 µl), and 2 µl of sample DNA. Negative controls substituted sample DNA with 2 µl of PCR-grade water. DNA amplification occurred with the following thermocycler parameters: 94 °C for 3 min (1x), 94 °C for 45 s (35x), 50 °C for 60 s (35x), 72 °C for 90 s (35x), and 72 °C for 10 min (1x). All PCR products were then visualized on a 1.2% agarose gel using a reference 100 bp ladder. PCR products were cleaned using 60 µl of AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, CA) following the manufacturer’s directions. Cleaned samples were quantified using the High Sensitivity DNA Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA) with the Qubit V3. Following quantification, all samples were normalized to 4 nM using PCR-grade water. A 5 µl aliquot of each normalized sample was pooled based on their barcodes. Duplicate barcodes were processed in separate pools of two. The two tubes were then transported on ice to the Hussman Institute for Human Genomics, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, for sequencing on two MiSeq runs using a PE-300v3 kit (Illumina, CA).

Bioinformatics analysis

To process the microbiome sequence data bioinformatic analysis was conducted. Both Miseq runs were demultiplexed at the University of Miami’s core facility. To process sequence data, R (v4.0.3) and RStudio (v1.4.1106) were used. First, PCR primers were removed from forward and reverse reads using Cutadapt v3.446. Subsequently, the R package DADA2 v1.18.0 was used to generate, quality profiles, and based on these profiles (dada2::plotQualityProfile), the data were trimmed and filtered (dada2::filterAndTrim; truncLen=c(210,140), minLen=100, and trimLeft=10)47. Error models were generated for forward and reverse reads individually (dada2::learnErrors) and then visually inspected (dada2::plotErrors). All reads were dereplicated (dada2::derepFastq) and Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) were inferred with respective error models (dada2::dada). Forward and reverse ASVs were merged (dada2::mergePairs) and a count table was generated for each run (dada2::makeSequenceTable). Chimeras were removed (dada2::removeBimeraDenovo) and taxonomy was then assigned (dada2::IdTaxa) to ASVs using the SILVA SSU r138 2019 database48. Identical sequences with contrasting taxonomies were aligned to the NCBI non-redundant database, and the taxonomic designation with the lower taxonomic assignment was selected. Finally, the count, taxonomy, and ASV sequence tables from both MiSeq runs were combined.

Since unclassified ASVs may be important in the coral microbiome, sequences without taxonomic assignments were further analyzed. ASVs that did not have a taxonomy assignment at the genus level were aligned to the non-redundant nucleotide (nt) database (v6) using NCBI Blast+ v2.12.0 with task=megablast, max_target_seqs=5, max_hsps=5, and word_size=549. Sequences with taxonomic hits were run through the program Taxonomizer v0.8.050, which provides full taxonomies on an SQLite database (taxonomizr::prepareDatabase). Full taxonomy for results was then obtained (taxonomizr::getTaxonomy). The taxonomy file generated in DADA2 was then updated with new taxonomy assignments. A phylogenetic tree was constructed for all ASVs identified from DADA2 using the r package phangorn v2.7.151. A neighbor-joining tree was generated (phangorn::treeNJ) before model parameters were optimized (phangorn::optim.pml). The generated tree was then visualized in FigTree v1.4.4. Tree inspection then allowed putative annotation of unknown ASVs to differing taxonomic levels depending on surrounding annotated ASVs.

All ASVs with taxonomical identification to mitochondrial, chloroplast, or Eukaryotes were also removed. The generated phylogenetic tree also identified unclassified ASVs surrounded by mitochondrial and chloroplast ASVs and these were removed from downstream analysis. Minimum read depth recommendations when sequencing the variable 4 16S rRNA amplicon range from 200052 to 10,000–15,00053 reads per sample. For our dataset, we utilized 15,000 reads per sample.

Statistical analysis for bioinformatic data

All statistical analyses below were conducted using R v4.3.2. To explore differences in alpha diversity that may correlate with survivorship rates across genotypes, months, coral reefs, and their interactions, we used the Shannon diversity index to quantify richness and evenness. To avoid pseudoreplication individual fragments collected from the same clusters on the same day were merged into a single sample using the function merge_samples2 with the R package phyloseq v 1.46.054. Alpha diversity was assessed with phyloseq after filtering ASVs absent in any samples. The phyloseq function rarefy_even_depth was employed with the parameters replace set to FALSE, and a minimum sampling size of 15,000. To determine the Shannon Index Diversity metric, the phyloseq function estimate_richness with rarefied data was used. Multiple normalization techniques were explored (i.e., log2, log10, and square root), and because log10 passed the Shapiro-Wilk normality test this was used to normalize the data. Linear mixed models with lme4 v 1.1.35.155 were then applied to test significant differences in Shannon diversity based on genet, coral reefs, and month(s). The relationship between the transformed Shannon index and the fixed effect genet was analyzed, accounting for random intercepts for combinations of sample trip, and reef, with no intercept assigned for the fixed effects. In the case of the reef variable, a similar model was employed, with reef as the fixed effect and genet as the random effect. For the month of sampling, the random intercept was genet. The interaction between genet and reef was also explored. The emmeans function was applied to each model to compute the estimated marginal means (EMM) for each fixed effect and pairwise comparison. The pairwise comparisons were performed without an overall intercept, and a post hoc comparison was performed with the Tukey HSD test. To evaluate if alpha-diversity correlates with the habitat factors that can impact coral survivorship, habitat variables, and Shannon diversity were correlated using the R package pbkrtest v 0.5.256.

The core microbiome was explored to evaluate if prevalent bacteria are present within each genet and may correlate with genet survivorship, or change with habitat factors. To characterize common microbial taxa present among genets, the core microbiome in all samples was first grouped by genet and examined at the ASV level. Utilizing the core function of the microbiome v1.24.0R package57, ASVs present in at least 99% of cohorts were considered core taxa, irrespective of their abundance. After core ASVs were identified some core bacteria did not have assigned taxonomy, so the phylogenetic tree generated was used to assess potential genetic similarities. With phangorn 2.11.1 a phylogenetic tree was constructed to taxonomically characterize core ASVs with unassigned taxonomy. The tree was subset by randomly sub-setting one sibling and one first cousin from each core ASV.

Beta-diversity analysis was performed to understand the microbial composition across genet, and coral reef. The raw count table underwent filtering (not rarefied), including only ASVs with a cumulative count of 10 in at least 15% of the samples. The filtered count table was transformed using the clr (centered log-ratio) option in the microbiome R package. The clr transformation is a method used to transform compositional data by taking the logarithm of the ratio of each ASV to the geometric mean of all ASVs, thus the transformed data lie in an unconstrained Euclidean space. The resulting transformed matrix was then subjected to ordination using Euclidean distance and visualized on Principal component (PC) analysis. The correlation between genet, coral reef, and months against PCs was determined with the program PCAtools v 2.14.0 with the function eigencorplot. To assess the dispersion of genet, coral reef, and months, the Vegan package v 2.6.4 was employed58. The vegdist function was applied with the Euclidean method to the transformed matrix, generating a distance matrix. The betadisper function was then utilized to evaluate multivariate homogeneity of group dispersions using the centroid method. For pairwise comparisons, Tukey multiple comparisons of means were conducted using the TukeyHSD function. To investigate differences in beta-diversity and interactions among genets, coral reefs, and months, the adonis2 function from the Vegan package and the distance matrix generated with vegdist, were used by applying the Euclidean method with 999 permutations. For pairwise comparisons, the package pairwise.adonis was used with Bonferroni for multiple corrections59.

To determine if habitat conditions contributed to the coral genet, and reef microbial composition a redundancy analysis (RDA) models were constructed with clr-transformed data. First, the habitat data was evaluated for covariance. If a pair correlated >75% one of the variables was removed. First, a model with only the intercept term was used, and the second model included selected habitat variables (i.e., <75% correlation). To identify the most informative variables influencing the microbial community composition, a stepwise model selection procedure was performed. The Vegan function ordistep was applied, to the first model as the starting model, and then a scope with the full model, with a maximum of 200 permutations, and a bidirectional stepwise selection approach. This stepwise selection aimed to refine the model by iteratively adding or removing variables based on their contribution to the overall model fit, providing insights into the significant factors shaping the microbial community structure of the selected habitat variables. The selected variables were evaluated for Variance of Inflation Factor with the function vif.cca. To examine the significance of each variable added or removed during the stepwise model selection process a one-way ANOVA was performed on the ordistep output. A correlation between RDA ordination axes against genet, coral reef, and months, selected habitat variables was conducted with the function envfit with 999 permutations.

To assess individual ASVs that are characteristic of the coral reef and month of sampling, a random forest classification approach using the R package randomForestSRC v 3.2.260 was used. This classification technique was used with 400 trees, with a minimum of one terminal node per tree. The trees were developed using the swor resampling method, and a resampling size of 229 was utilized in the tree growth process, random splits were based on the Gini index, and the importance of each ASV was computed using a permutation test. ASVs with the highest importance values were correlated to habitat variables selected by the oristep model with a Spearman correlation and then plotted to show their relative abundances.

Results

There were significant differences in survivorship between genets and coral reefs

The Cox proportional hazards model fitted to assess the impact of genet and reef, on the survival of coral fragments, showed that compared to the reference genet CN2 genets CN4 and ML2 had a significantly lower likelihood of surviving based on hazard ratios (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2). For coral reefs, NDR (coef = −2.1 and pval < 0.001) and PR (coef = −2.6 and pval < 0.001) had higher likelihoods of survivorship compared to CF (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2). Supplementary Table 3 shows survivorship split by all fragments in the survey (including those not sampled for microbiome analysis), all fragments grouped by clusters, and only the fragments surveyed for microbiome analysis. The data show the same trends across subsets with genet survivorship varying by coral reef and the reef CF having the lowest survivorship rates (38.8–64.5%), followed by NDR (81.0–83.5%), and PR (87.1–89.0%).

The risk of death of Acropora palmata at three coral reefs (Carysfort Reef [CF], North Dry Rocks [NDR], and Pickles Reef [PR]) in the upper Florida Keys (relative to CF), and per genet across reefs (relative to genet CN2). The vertical gray line at x = 1 represents the intercept of the Cox proportional hazards model, indicating the baseline hazard when all covariates are set to zero. This serves as a reference point for interpreting the hazard ratios associated with each treatment group. The orange color denotes an increase in hazard ratio relative to reference =1 and the blue a decrease to reference =1. The shade flanking the points represents the 95% confidence interval.

Sea surface temperatures were similar across coral reefs but not time

Habitat data was examined for environmental differences across coral reefs and months that may correlate to outplant survivorship. The studied coral reefs experienced no significant differences in averaged SST conditions between reefs (SST; CF = 28.0±sd 0.39 °C, NDR = 28.2 ± 0.45 °C, and PR = 28.0 ± 0.47 °C; Supplementary Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 4). However, NDR did experience the most temperature variation (Fig. 1a). Across all coral reefs, as expected, the June-July and September months (29.7 ± 0.53 and 29.1 ± 0.56 °C, respectively) were warmer than the February-March and November months (26.1 ± 0.28 and 27.4 ± 0.36 °C, respectively).

Chlorophyll-a varied across coral reefs and time

Chl-a concentrations were variable across reefs (Supplementary Fig. 1b, and Supplementary Table 4), with significantly higher Chl-a concentration in NDR (2.7 ± 1.1 mg m−3) compared to CF (Tukey’s HSD padj < 0.0001, 18 ± 0.29 mg m−3) and PR (Tukey’s HSD, padj < 0.0001, 0.8 ± 0.43 mg m−3). CF and PR were also statistically different from one another (Tukey’s HSD padj < 0.0001). Chl-a also varied through time with higher Chl-a concentrations in June-July (2.16 ± 1.05 mg m−3) compared to February-March (Tukey’s HSD padj < 0.0001, 1.30 ± 0.50 mg m−3), September (Tukey’s HSD padj < 0.0001, 1.35 ± 0.85 mg m−3), and November (Tukey’s HSD padj < 0.001, 1.74 ± 0.85 mg m−3).

Current velocities varied in coral reefs and time

Mean monthly current velocities were variable over coral reefs. PR had statistically stronger currents (7.8 ± 3.55 cm/s) compared to CF (Tukey’s HSD padj < 0.0001, 6.9 ± 3.17 cm/s) and NDR (Tukey’s HSD padj < 0.0001, 6.2 ± 3.27 cm/s). Currents also differed between all months (Tukey’s HSD padj < 0.0001), except for June-July vs. September comparisons which were not statistically different. The highest current speeds were logged in March (8.0 ± 4.00 cm/s) and the lowest was in June (5.8 ± 3.14 cm/s) across all reefs.

North dry rocks was the shallowest reef

For the sampling depth of each coral colony cluster, CF had the deepest surveyed clusters on average (19 ± 1.2 ft), followed by PR (17 ± 1.0 ft) and NDR (12 ± 0.6 ft).

Nutrients were consistent across coral reefs but silicic acid and nitrates varied over time

Nutrients were consistent across reefs (Supplementary Fig. 2a. and Supplementary Table 5). However silicic acid and nitrates varied over time (Supplementary Fig. 2b. and Supplementary Table 5). Silicic acid was significantly higher in November compared to both June-July and September time points (Supplementary Fig. 2b. and Supplementary Table 5). Nitrate was significantly different between months except between June-July and September when nitrate was at the highest concentrations compared to the other time points (Supplementary Fig. 2b. and Supplementary Table 5).

Summary of Acopora palmata samples sequenced in this study

To understand changes in microbiome across months, coral reefs, habitat, and its potential role in coral survivorship 378 samples were sequenced for 16S rRNA gene analysis. After quality assessments, 346 samples remained (Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 1c) with 11 samples removed nine of these having <2500 reads/sample, and the remaining two having 14,547 and 14,800 reads. Following merging fragments from the same cluster collected on the same day into a single representative, the total sample count was 124. Removal of unwanted ASVs resulted in a total of 27,486 ASVs for the analysis with a minimum number of reads in a sample = 16,876, a maximum = 411,671, and a median = 121,280.

Genets showed some differences in microbial community dispersion and alpha-diversity

To understand beta-diversity differences among genotypes prevalent ASVs (n = 481) were evaluated. Significant differences in microbial dispersion between genets were observed (TukeyHSD padj < 0.05), except between CN4 vs. CN2 and ML2 vs. HS1 (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 3a), indicating a variation in microbial community between some genets. Across all samples (i.e., pooled across reefs and months) PERMANOVA pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences between genets ML2 and HS1 (padj = 0.02 R2 = 0.03) and HS1 and CN2 (padj = 0.002 R2 = 0.03; Fig. 3a). Alpha diversity analysis showed that CN4 had the highest Shannon diversity, and ML2 had the lowest (TukeyHSD padj = 0.003). In addition, ML2 was also significantly different from CN2 (TukeyHSD padj = 0.009), but all other genet comparisons were not significant (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

The data are plotted across (a) Principal components (PC) 4 and 5 colored by genet (b) PC 2 and 3 colored by coral reefs, and (c) PC6 and PC7 colored by months. Figures a-c were centered log-ratio (CLR) transformed and plotted with a Euclidean distance, and ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals. d Redundancy analysis (RDA) with CLR transformed data. The RDA was constrained by currents, depth, nitrate, nitrite, phosphate, silica, and sea surface temperature (SST), colored by months, and shapes representing coral reefs.

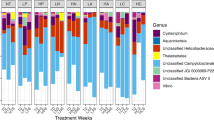

Genets shared four core microbial members some with unassigned taxonomy

The core microbiome across all genets was characterized to identify if there were unique core microbial members that may correlate with survivorship. In total, four ASVs were present in at least 99% of all samples independent of abundance (Supplementary Fig. 3c). The four core ASVs included: ASVs 5 (13.87 ± 16%), 6 (13.77 ± 19%), 7 (8.17 ± 8.9%), and 23 (1.22 ± 1.8%). ASVs 5, 6, and 7 were not only present in the majority of samples but were also found at high relative abundances (Supplementary Fig. 4). When each genet was evaluated independently these three ASVs were also found in each genet at 99% prevalence, but ASV 23 was not prevalent in genets HS1 and ML2. ASV 7 was characterized up to the order level as SAR-324, and ASV 23 to the family level as Cyanobiaceae. However, ASVs 5 and 6 had no similarities to the database even at the domain level. Phylogenetic analysis of the core microbiome did not help resolve ASV 6, but ASV 5 was found to be related to Sphingomonadaceae (Supplementary Fig. 3c).

Coral reef microbial beta-diversity exhibited interactions with genet, coral reef, and months

Alpha and beta diversity were examined to identify any temporal or geographic changes in coral-associated microbial communities. There were no significant differences in Shannon diversity, and the three coral reefs also did not have significantly dispersed microbial communities. Among months microbial communities were significantly dispersed between cooler and warmer months (February-March vs. June-July and September vs. November; TukeyHSD padj <0.05). Beta-diversity varied in coral reefs and time (PERMANOVA, pairwise adonis padj <0.05; Fig. 3b, c). Interaction among genet, reef, and month, was statistically significant (p = 0.036; Supplementary Table 6). Significant interactions were also observed between month and reef (PERMANOVA pval = 0.001, and R2 = 0.08), and genet and reef (PERMANOVA pval = 0.002, and R2 = 0.05). Independently, months had the highest correlation to the distance matrix (R2 = 0.09), compared to coral reefs (R2 = 0.06), and genet (R2 = 0.04). However, correlations to all principal components (PC) showed that neither genet nor month was significantly correlated; but PC2 was significantly correlated with reef (Fig. 3a–c).

Habitat variables were important in community composition, but temperature and nitrite showed the highest correlations to beta-diversity

To identify if habitat variables may drive changes to the microbial composition an ordistep model was used. Chl-a and cluster depth exhibited a correlation rate of 76%. Consequently, Chl-a was excluded from the model selection analysis to avoid auto-correlation effects. Of the remaining eight variables, the highest positive correlation was between nitrite and SST (R2 = 0.70), and the highest negative correlation was between current velocity and nitrite/nitrate (R2 = −0.50). Coral survivorship also showed positive correlations with depth (R2 = 0.50) and currents (R2 = 0.20) and negative correlations with nitrite (R2 = −0.20) and phosphate (R2 = −0.01; Supplementary Fig. 5). All habitat data had explanatory power for the microbiome counts data -- except survivorship (Fig. 3d). Selected variables had VIF scores below 15, indicating that they represent effects that are independent of one another, and the selected model was significant (ANOVA pval = 0.001, and F = 3.08). Both categorical and habitat variables were correlated with RDA1 and RDA2. Envfit resulted in statistically significant categorical variables in coral reefs (R2 = 0.31, and pval = 0.001) and month (R2 = 0.39, and pval = 0.001) but genet was not significant (Supplementary Table 7). All habitat variables significantly correlated with RDA1 and 2 except phosphate, with SST (R2 = 0.72), and nitrite (R2 = 0.47) having the highest correlations (Supplementary Table 7). Accordingly, the RDA plot clustered samples by month and reef (Fig. 3d). Warmer months (or wet season; June-July and September) correlated to SST, nitrate, and nitrite. While the cooler months (or dry season; February-March, and November) correlated with silica and current velocities. Regarding reef, cluster depth clustered with NDR the shallowest reef in this study.

Alpha diversity increases with increased SST and nitrite in the summer months

Alpha diversity was examined against the nine habitat variables collected in this study to evaluate if coral alpha diversity correlates with habitat changes (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). The linear regression showed that only nitrite (pval = 0.004 and R2 = 0.07) and SST (pval = 0.03 and R2 = 0.04) were positively correlated with Shannon Diversity (Supplementary Fig. 6). With slight increases in diversity during higher temperatures and nitrite values that occurred in June, July, and September.

Specific bacteria associated with coral reefs and time

Random forest (RF) analysis identified microbiome taxa associated with coral reefs and months. Using the importance values from RF output the top five highest values (an arbitrary cut-off) were selected for further analysis. RF results for coral reefs demonstrated an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.91 and a misclassification rate of 0.27. Overall ASV 109 (0.01; Rhodobacteraceae; Fig. 4a and Supplementary Data 2), showed the highest importance value in the model. CF showed the highest classification error (0.81) when the model was assessed per reef. In CF, the highest RF importance values were for ASV288 (0.02; SAR324 clade (Marine group B)), which was also found at higher relative abundances in CF (2.5e−04) compared to NDR (8.4e−05) and PR (2.1e−04; Supplementary Fig. 7). Both NDR (0.04) and PR (0.13) had lower model error rates with ASV 109 (0.04; Rhodobacterales) having the highest importance value in NDR. However, relative abundances of ASV 109 were relatively higher in CF (0.0012) compared to NDR (0.0010) and PR (0.0002). In PR ASV 172 (0.03; Cellvibrionales; Supplementary Fig. 7) had the highest importance value, but showed lower relative abundances in PR (7.5e−05) compared to CF (5.1e−04) and NDR (4.8−04; Supplementary Fig. 7). The top RF important bacteria across reefs were mostly positively correlated with lower depths and high nitrite concentrations and negatively correlated with current speeds (Fig. 4b).

a Top most important ASVs selected by random forest analysis. The x-axis represents the ASV importance across the entire model and the y-axis represents the ASV importance value per coral reef. The symbols are shaped by coral reefs and colored by the bacteria taxa. b Density plot, and heatmap of important ASVs. The ASVs and habitat variables (selected by the RDA model) are hierarchically clustered. The presence of a number value on the heat map denotes a significant Spearman correlation between ASV and habitat variables.

In terms of months, the AUC reached 0.99, accompanied by a minimal misclassification rate of 0.008. Errors remained consistently low, ranging from 0 to 0.03 across different months. ASVs with the highest importance values during specific periods included: ASV 1038 (0.05; NS2b marine group) in Feb-Mar, ASV 1966 (0.6; Parvibaculales; PS1 clade family) in Jun-Jul, ASV 865 (0.17; Alteromonadales; Thalassotalea) in Sept, and ASV 151 (0.07; Pseudomonas) in Dec (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 7, and Supplementary Data 3). Both nitrate and nitrite resulted in more positive correlations with important ASVs, followed by temperature and currents (Fig. 5b). However, nitrite also resulted in the most negative correlations with important ASVs. ASV 5, a core bacterium, was found across most samples at relatively high abundances – especially compared to all other taxa, and positively correlated with silica and negatively with nitrate and nitrite (Fig. 5b).

a Top most important ASVs selected by random forest analysis. The x-axis represents the ASV importance across the entire model and the y-axis represents the ASV importance value per month. The symbols are shaped by the month and colored by the bacteria taxa. b Density plot, and heatmap of important ASVs. The ASVs and habitat variables (selected by the RDA model) are hierarchically clustered. The presence of a number value on the heat map denotes a significant Spearman correlation between ASV and habitat variables.

Discussion

Our objective was to better understand the mechanisms underlying outplanted coral success observed in specific genets and coral reefs14. We hypothesized that both habitat and microbial communities are important to coral survivorship. To evaluate this, we sampled four Acropora palmata genets (CN2, CN4, HS1, and ML2) outplanted across three different coral reefs (Carysfort [CF], North Dry Rocks [NDR], and Pickles Reef [PR]) in the upper Florida Keys. Habitat and satellite remote sensing data were collected for each coral reef to identify potential drivers of survivorship, and paired with coral microbiome observations. This study found that while some A. palmata genets display differences in their survivorship and microbial indices, genet and microbiomes had little explanatory power over one another. Instead, we found that coral reef site and habitat conditions correlated with coral survivorship rates and changes in the microbiome19,61.

Genet influenced outplant survivorship, but this was not reflected in the microbiome. Our hazard model analysis revealed that coral genet impacted outplant survivorship. Specifically, genet CN4 and ML2 exhibited a higher risk of dying compared to genet CN2. This contrasts a recent study that investigated A. palmata outplant success in genets CN2, ML2, and HS1 but found no genet effect on survivorship19. The discrepancy may be attributed to the smaller sample size in that study (i.e., 50 outplants). However, we tracked a larger number of coral fragments, providing enhanced statistical power to discern these trends. Additionally, coral survivorship results from this study contradict findings from a previous tank experiment that also assessed CN2, CN4, ML2, and HS1 survivorship rates after disease exposure, showing no significant differences among genets14,19,34. This suggests that these genets may exhibit similar responses to individual perturbations (i.e., pathogens), but under the synergistic effects experienced in a natural coral reef setting with multiple abiotic (i.e., nutrient pollution, and elevated temperatures) and biotic conditions (i.e., predation, and pathogens) genet may play a significant role in survivorship.

Similar to previous studies19,34, we did not find clear associations between coral microbial communities and A. palmata genet survivorship. This implies that for A. palmata, genet survivorship may have limited correlation with the microbiome, and other genetic factors such as baseline gene expression62, epigenetic conditioning63, or other members of the holobiont not examined (i.e., symbiotic algae, fungi, and viruses) may be more important in genet survivorship rates63. For example, while CN2 and CN4 were not statistically different in alpha and beta diversity, risk analysis demonstrated a statistically significant difference in survivorship between these two genets. In other coral species such as Acropora cervicornis, microbiome composition between genets has been correlated with survivorship64 but our results indicate that the microbiome of A. palmata may be more homogenous with little difference among genets. For instance, three core ASVs, as well as the order Spirochaetales, were dominant and prevalent across our genets. Specifically, the results of Spirochaetales are consistent with other work in A. palmata19,28,65. The species-specific, instead of genet-specific, nature of the microbiome in A. palmata could explain why there was no correlation between genet survivorship and the microbiome. This could indicate that, for restoration, this variable may not be as important as in other coral species.

Our results do suggest that coral reef sites correlate with outplant success. A previous study that compared A. palmata survivorship rates which overlapped with the genotypes from this study and also took place in three other upper Florida Keys coral reefs found no differences in survivorship between coral reefs11. This may be attributed to the lower number of fragments tracked or perhaps the reefs sampled may have had similar environmental conditions which resulted in similar survivorship rates11. In contrast, our results show that microbial communities exhibited correlations with outplant locations, with depth and nitrite levels being the main factors in microbiome abundances.

CF is a historically important reef often targeted in restoration projects, but in our study, CF exhibited the lowest survivorship rates. This suggests that restoration efforts should consider if other coral reef sites may provide better long-term outcomes. CF was characterized as having slower currents (compared to PR), the highest nitrate concentrations (although not significantly different), the lowest SST variance, and the deepest sampled outplants on average. Habitat variables such as current speed, depth, and nutrient concentration may be important factors to consider before selecting areas to outplant. For example, survivorship rates were positively correlated with higher current speeds, and lower nitrate, indicating that the slower current velocity and higher nitrate may have contributed to the lower survivorship in CF. In contrast, PR, which had higher survivorship rates, experienced faster currents and lower nitrate. A recent study on the same genets suggested periodic upwelling activity can increase A. palamta health, hypothesizing a link to heterotrophic activity19. Here, we provide an additional hypothesis that increased current velocities may reduce nutrient accumulation and thus increase survivorship in A. palmata, making currents an important consideration for restoration activities.

Survivorship rates were also positively correlated with shallower depths. While PR and CF showed little depth difference, NDR outplants on a spur experienced shallower depths. Depth, rather than current speed, may have driven higher survivorship in NDR and aligns with predictions that A. palmata prefers shallower coral reef environments17. The correlation between shallower depths and faster currents with higher survivorship demonstrates how different habitats can independently contribute to the success of outplanting. Shallower depths were also positively correlated with the top random forest microbiome taxa from all coral reefs indicating that many important microbiome members thrive in shallower depths. In agreeance, a meta-analysis of cnidarian microbiomes across the globe showed that shallower depths increased microbial diversity and shaped microbial composition66. Thus, coral reef depth may have impacts on the coral holobiont and outplant survivorship.

In NDR and PR, Rhodobacterales ASV 109 was an important taxon in the RF model. Despite its importance in the RF model for these coral reefs, ASV 109 had a lower relative abundance in NDR and PR compared to CF, where it exhibited a higher relative abundance. Rhodobacterales ASV 109 was also positively correlated with nitrite and negatively correlated with currents. This group of bacteria is diverse67, and is associated with coral larvae68, but is commonly found as a player in diseased coral69. In the water column, Rhodobacterales have also been noted as potential indicators of unhealthy coral reefs70,71. Our study provides further evidence that Rhodobacterales abundance is important and should be used for biomonitoring of reef health and potentially be used as a marker for outplanting site selection.

The time of collection significantly influenced A. palmata microbiomes. Despite the visually healthy appearance of the sampled corals, putative pathogens were at higher relative abundances in the warmer months (wet season). Beta diversity results showed distinct clustering observed with SST, nitrite, and nitrate during warmer months, and that alpha diversity increased with elevated SST and nitrate concentrations in June-July and September, a pattern also observed in other coral species72. In September, the most important ASV in the RF model belonged to Alteromonadales (Thalassotalea ASV 865), a genus often associated with thermally stressed corals64,72,73. This ASV exhibited a positive correlation with SST, a higher relative abundance in September compared to other months, and a higher correlation with nitrate, and nitrite compared to other measured habitat variables. Our observations are supported by a meta-analysis of coral microbiomes showing a slightly higher correlation of Altermondales in corals within polluted waters compared to elevated temperatures72. In combination, these studies illustrate how putative pathogenic bacteria can be influenced by a combination of global and local stressors. Additionally, this study provides evidence that visually healthy corals may still be undergoing stress, or that putative pathogens may not always incite pathogenesis.

Elevated nitrate and nitrite likely have negative consequences on the microbiome by increasing the relative abundance of bacteria like Altermondales, but also by decreasing core bacteria. We found ASV 5 (related to Sphingomonadaceae) was prevalent and abundant across samples, suggesting that ASV 5 is likely a host-adapted core bacteria that responds to host fitness74. As a core member, ASV 5 may be providing essential functions and supporting coral resilience that could be impacted by high nutrient concentrations. For example, A. palmata thrives in low-nitrogen settings17, and a reduction in core bacteria caused by elevated nitrogen levels might contribute to its capacity for survival and colonization. However, genome sequencing of this bacteria would provide better evidence of its functional role. Our results suggest that outplanting of A. palmata should be minimized during the wet season when nutrient concentrations are increased and core bacteria are less likely to thrive.

Conclusion

This study contributes to understanding the roles of habitat and microbial communities in the restoration success of A. palmata. We found that coral genotype played a role in survivorship, but based on our results we hypothesize that other genetic factors aside from bacteria are likely better correlated with survivorship such as the host epigenetics, or gene expression. Coral reefs were also an important factor and fine scale differences in environmental conditions between reef habitats correlated to differences in survivorship. Specifically, factors such as current velocity, and shallower reef depth correlated with higher A. palmata survivorship. For microbiome taxa, Rhodobacterales had lower relative abundances in reefs exhibiting higher survivorship and positively correlated with nitrite. Furthermore, we observed that elevated levels of nitrate, nitrite, and temperature (particularly during summer months) negatively affect A. palmata at the microbial level by potentially contributing to the relative decline of core bacteria and increase in putative pathogens like Alteromonadales. We propose that A. palmata outplanting should prioritize shallower depths with faster currents, in low-nutrient environments, and site selection should not be based on historical significance alone.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw sequence data is available on NCBI PRJNA1081901. The metadata files, counts tables, taxonomy table, and phylogenetic tree are available https://github.com/srosales712/CoralPersistence.

Code availability

The R code used for the analysis is publicly available at https://github.com/srosales712/CoralPersistence.

References

Sully, S., Hodgson, G. & van Woesik, R. Present and future bright and dark spots for coral reefs through climate change. Glob. Chang. Biol. 28, 4509–4522 (2022).

Cramer, K. L. et al. Widespread loss of Caribbean acroporid corals was underway before coral bleaching and disease outbreaks. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax9395 (2020).

Hogarth, W. T. Endangered and threatened species: final listing determinations for elkhorn coral and staghorn coral. Fed. Regist. 71, 26852–26861 (2006).

Miller, M., Crabbe, J., Villamizar, E., Croquer, A. & Banaszak, A. Acropora palmata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022: e.T133006A165672016 (2022).

Alvarez-Filip, L., Dulvy, N. K., Gill, J. A., Côté, I. M. & Watkinson, A. R. Flattening of Caribbean coral reefs: region-wide declines in architectural complexity. Proc. Biol. Sci. 276, 3019–3025 (2009).

Hughes, T. P. Catastrophes, phase shifts, and large-scale degradation of a Caribbean coral reef. Science 265, 1547–1551 (1994).

Loh, T.-L., McMurray, S. E., Henkel, T. P., Vicente, J. & Pawlik, J. R. Indirect effects of overfishing on Caribbean reefs: sponges overgrow reef-building corals. PeerJ 3, e901 (2015).

Aronson, R. B. & Precht, W. F. White-band disease and the changing face of Caribbean coral reefs. Hydrobiologia 460, 25–38 (2001).

Williams, D. E. & Miller, M. W. Attributing mortality among drivers of population decline in Acropora palmata in the Florida Keys (USA). Coral Reefs 31, 369–382 (2012).

Bove, C. B., Mudge, L. & Bruno, J. F. A century of warming on Caribbean reefs. PLOS Clim. 1, e0000002 (2022).

Kuffner, I. B., Stathakopoulos, A., Toth, L. T. & Bartlett, L. A. Reestablishing a stepping-stone population of the threatened elkhorn coral Acropora palmata to aid regional recovery. Endanger. Species Res. 43, 461–473 (2020).

Boström-Einarsson, L. et al. Coral restoration – A systematic review of current methods, successes, failures and future directions. PLoS One 15, e0226631 (2020).

Suggett, D. J. & van Oppen, M. J. H. Horizon scan of rapidly advancing coral restoration approaches for 21st century reef management. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 6, 125–136 (2022).

Goergen, E. A. & Gilliam, D. S. Outplanting technique, host genotype, and site affect the initial success of outplanted Acropora cervicornis. PeerJ 6, e4433 (2018).

Henley, M. et al. Growth and survival among Hawaiian corals outplanted from tanks to an ocean nursery are driven by individual genotype and species differences rather than preconditioning to thermal stress. PeerJ 10, e13112 (2022).

Drury, C., Manzello, D. & Lirman, D. Genotype and local environment dynamically influence growth, disturbance response and survivorship in the threatened coral, Acropora cervicornis. PLoS One 12, e0174000 (2017).

Banister, R. B., Viehman, T. S., Schopmeyer, S. & van Woesik, R. Environmental predictors for the restoration of a critically endangered coral, Acropora palmata, along the Florida reef tract. PLoS One 19, e0296485 (2024).

Fabregat-Malé, S., Mena, S. & Alvarado, J. J. Nursery-reared coral outplanting success in an upwelling-influenced area in Costa Rica. Rev. Biol. Trop. 71, e54879–e54879 (2023).

Chapron, L. et al. Heterotrophy, microbiome, and location effects on restoration efficacy of the threatened coral Acropora palmata. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 1–12 (2023).

Young, C. N., Schopmeyer, S. A. & Lirman, D. A Review of Reef Restoration and Coral Propagation Using the Threatened Genus Acropora in the Caribbean and Western Atlantic. Bull. Mar. Sci. 88, 4 (2012).

Burdett, H. L. et al. Including environmental and climatic considerations for sustainable coral reef restoration. PLoS Biol. 22, e3002542 (2024).

Corinaldesi, C. et al. Microbiome-assisted restoration of degraded marine habitats: a new nature-based solution? Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1227560 (2023).

Strudwick, P. et al. Impacts of nursery-based propagation and out-planting on coral-associated bacterial communities. Coral Reefs 41, 95–112 (2022).

Goulet, T. L., Erill, I., Ascunce, M. S., Finley, S. J. & Javan, G. T. Conceptualization of the Holobiont Paradigm as It Pertains to Corals. Front. Physiol. 11, 566968 (2020).

Blackall, L. L., Wilson, B. & van Oppen, M. J. H. Coral—the world’s most diverse symbiotic ecosystem. Mol. Ecol. 24, 5330–5347 (2015).

Puntin, G. et al. Harnessing the Power of Model Organisms To Unravel Microbial Functions in the Coral Holobiont. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.00053-22 (2022).

Voolstra, C. R. et al. Extending the natural adaptive capacity of coral holobionts. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 747–762 (2021).

Rosales, S. M. et al. Microbiome differences in disease-resistant vs. susceptible Acropora corals subjected to disease challenge assays. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–11 (2019).

Durante, M. K., Baums, I. B., Williams, D. E., Vohsen, S. & Kemp, D. W. What drives phenotypic divergence among coral clonemates of Acropora palmata? Mol. Ecol. 28, 3208–3224 (2019).

Foo, S. A. & Asner, G. P. Sea surface temperature in coral reef restoration outcomes. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 074045 (2020).

Lohr, K. E., Ripple, K. & Patterson, J. T. Differential disturbance effects and phenotypic plasticity among outplanted corals at patch and fore reef sites. J. Nat. Conserv. 55, 125827 (2020).

Baums, I. B., Devlin-Durante, M. K. & LaJeunesse, T. C. New insights into the dynamics between reef corals and their associated dinoflagellate endosymbionts from population genetic studies. Mol. Ecol. 23, 4203–4215 (2014).

de Meeûs, T., Prugnolle, F. & Agnew, P. Asexual reproduction: genetics and evolutionary aspects. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64, 1355–1372 (2007).

Young, B. D. et al. Innate immune gene expression in Acropora palmata is consistent despite variance in yearly disease events. PLoS One 15, e0228514 (2020).

Miller, M. W. et al. Genotypic variation in disease susceptibility among cultured stocks of elkhorn and staghorn corals. PeerJ 7, e6751 (2019).

Therneau T A Package for Survival Analysis in R. R package version 3.7-0, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival (Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN), 2024).

Therneau, T. M. & Grambsch, P. M. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Chin, T. M., Vazquez-Cuervo, J. & Armstrong, E. M. A multi-scale high-resolution analysis of global sea surface temperature. Remote Sens. Environ. 200, 154–169 (2017).

Zhang, J. -Z. & Berberian, G. A. EPA Method 366.0: Determination of Dissolved Silicate in Estuarine and Coastal Waters by Gas Segmented Continuous Flow Colorimetric Analysis. pp.13 EPA-600-R-97-072 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C.,1997).

Zhang, J.-Z., Fischer, C. J. & Ortner, P. B. Comparison of Open Tubular Cadmium Reactor and Packed Cadmium Column in Automated Gas-Segmented Continuous Flow Nitrate Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 76, 99–113 (2000).

Zhang, J.-Z., Fischer, C. J. & Ortner, P. B. Continuous Flow Analysis of Phosphate in Natural Waters Using Hydrazine as a Reductant. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 80, 61–73 (2001).

Hood, E. M., Sabine, C. L. & Sloyan, B. M. The GO-SHIP Repeat Hydrography Manual: A Collection of Expert Reports and Guidelines. (Global Ocean Ship-Based Hydrographic Investigations Program (GO-SHIP), 2010).

Hydes, D. et al. Determination of dissolved nutrients (N, P, Si) in seawater with high precision and inter-comparability using gas-segmented continuous flow analysers (2010).

Young, B. D. Automated DNA/RNA Extractions from a stony coral (Acropora palmata) using ZymoBIOMICS DNA/RNA Magbead Kit and the Kingfisher Flex v2. https://doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.bp2l61wykvqe/v2 (protocols.io, 2022).

Apprill, A., McNally, S., Parsons, R. & Weber, L. Minor revision to V4 region SSU rRNA 806R gene primer greatly increases detection of SAR11 bacterioplankton. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 75, 129–137 (2015).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res 41, D590–D596 (2013).

Madden, T. L. The BLAST Sequence Analysis Tool. The NCBI handbook (National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), 2013).

Sherrill-Mix, S. Taxonomizr (Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN), 2023).

Schliep, K. P. phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics 27, 592–593 (2011).

Gregory Caporaso, J. et al. Colloquium Paper: Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 4516 (2011).

Bukin, Y. S. et al. The effect of 16S rRNA region choice on bacterial community metabarcoding results. Sci. Data 6, 190007 (2019).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8, e61217 (2013).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Halekoh, U. & Højsgaard, S. A Kenward-Roger approximation and parametric bootstrap methods for tests in linear mixed models: The R Package pbkrtest. J. Stat. Softw. 59, 1–32 (2014).

Lahti, L., Shetty, S. & Salojarvi, J. Microbiome (Bioconductor, https://doi.org/10.18129/B9.BIOC.MICROBIOME (2017).

Dixon, P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 14, 927–930 (2003).

Martinez Arbizu, P. pairwiseAdonis: Pairwise multilevel comparison using adonis. R package version 0.4. (Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN), 2020).

Ishwaran, H. & Kogalur, U. B. Random survival forests for R (R news, 2007).

Rosales, S. M., Sinigalliano, C., Gidley, M., Jones, P. R. & Gramer, L. J. Oceanographic habitat and the coral microbiomes of urban-impacted reefs. PeerJ 7, e7552 (2019).

Young, B. et al. Genet identity and season drive gene expression in outplanted Acropora palmata at different reef sites. Res. Square, https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4259333/v1 (2024).

Hackerott, S. et al. Relationships between phenotypic plasticity and epigenetic variation in two Caribbean Acropora corals. Mol. Ecol. 32, 4814–4828 (2023).

Palacio-Castro, A. M., Rosales, S. M., Dennison, C. E. & Baker, A. C. Microbiome signatures in Acropora cervicornis are associated with genotypic resistance to elevated nutrients and heat stress. Coral Reefs 41, 1389–1403 (2022).

Young, B. D. et al. Different disease inoculations cause common responses of the host immune system and prokaryotic component of the microbiome in Acropora palmata. PLoS One 18, e0286293 (2023).

McCauley, M., Goulet, T. L., Jackson, C. R. & Loesgen, S. Systematic review of cnidarian microbiomes reveals insights into the structure, specificity, and fidelity of marine associations. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–15 (2023).

Buchan, A., González, J. M. & Moran, M. A. Overview of the marine roseobacter lineage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 5665–5677 (2005).

Sharp, K. H., Distel, D. & Paul, V. J. Diversity and dynamics of bacterial communities in early life stages of the Caribbean coral Porites astreoides. ISME J. 6, 790–801 (2011).

Rosales, S. M. et al. A meta-analysis of the stony coral tissue loss disease microbiome finds key bacteria in unaffected and lesion tissue in diseased colonies. ISME Commun. 3, 19 (2023).

Rosales, S. M., Clark, A. S., Huebner, L. K., Ruzicka, R. R. & Muller, E. M. Rhodobacterales and Rhizobiales Are Associated With Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease and Its Suspected Sources of Transmission. Front. Microbiol. 11, 517258 (2020).

Glasl, B., Webster, N. S. & Bourne, D. G. Microbial indicators as a diagnostic tool for assessing water quality and climate stress in coral reef ecosystems. Mar. Biol. 164, 91 (2017).

McDevitt-Irwin, J. M., Baum, J. K., Garren, M. & Vega Thurber, R. L. Responses of Coral-Associated Bacterial Communities to Local and Global Stressors. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 286253 (2017).

Gajigan, A. P., Diaz, L. A. & Conaco, C. Resilience of the prokaryotic microbial community of Acropora digitifera to elevated temperature. Microbiologyopen 6, e00478 (2017).

Shapira, M. Gut Microbiotas and Host Evolution: Scaling Up Symbiosis. Trends Ecol. Evol. 31, 539–549 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We like to thank our field volunteers Ana Palacio, Caroline Dennison, Allyson DeMerlis, Samara Neufeld, and Annabeth Peterson. We would like to thank Lew Grammer for his help with gathering the TCM data from the instruments. We also like to thank the NOAA ‘Omics OAR NO_0019 for providing funding support for molecular lab work, sequencing, and support for Stephanie Rosales and Benjamin Young, and NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program for providing fieldwork support and supporting Allan Bright and Dana Williams. We like to thank the Coral Restoration Foundation for granting permission to access the sampling locations under permit FKNMS-2018-117. This research was carried out in part under the auspices of the Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies, a cooperative institute of the University of Miami and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), cooperative agreement NA 20OAR4320472.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M.R. secured funding, conceptualized the study, conducted fieldwork, conducted statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript. B.D.Y. conceptualized the study, conducted field and lab work, bioinformatic analysis, generated digital abstract, and helped with writing. A.B. conducted fieldwork and provided manuscript feedback and edits before submission. E.M. contributed satellite time-series data, provided maps, provided manuscript feedback and edits before submission. J.Z. provided resources and guidance for nutrient processing and provided manuscript feedback. N.T.K. provided manuscript feedback and edits before submission. D.W. secured funding, helped conceptualize the study, led fieldwork, conducted survivorship percent analysis, and provided manuscript feedback and edits before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Paige Strudwick and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Alireza Bahadori, Clare Davis, and Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosales, S.M., Young, B.D., Bright, A.J. et al. Reef site and habitat influence effectiveness of Acropora palmata restoration and its microbiome in the Florida Keys. Commun Earth Environ 5, 689 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01816-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01816-7