Abstract

Aquatic foods are crucial for global food and nutrition security, but overfishing has led to depleted fish stocks, threatening both food security and the environment. Here, we combine a fish stock model with a global agriculture and food market model in order to analyze scenarios involving a continuation of current fishing trends versus optimal management through maximum sustainable yield targets. Maximum sustainable yield management of overfished stocks could increase yields by 10.6 Megatons, equivalent to 12% of total catches and 6% of aquatic animal production in 2022. This would alleviate the need for aquaculture expansion by an equivalent of 3 years of growth in the aquaculture sector at its current level, and reduce meat and feed demand. Lower food prices and additional supply could enhance global food security. Conversely, continued overfishing will likely lead to lower catches over time, adding pressure to the agricultural and aquaculture sectors. Although maximum sustainable yield management is not a panacea, it represents a positive step towards achieving sustainable food production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fish and seafood, which, for brevity, we will refer to simply as fish, are rich in essential micronutrients, making them a healthier source of protein and calories compared to meat products from the agricultural sector1. Additionally, they can be produced in a relatively environmentally and climate-friendly manner2,3. In many developing countries, fishing is an important source of income for households, contributing to food and nutrient security. It is estimated that 97% of the 120 million people who depend on commercial capture fisheries value chains for their livelihoods are from developing countries. Furthermore, over 90% of these individuals are employed in the small-scale fisheries sub-sector4. Developing countries, such as Bangladesh, Cambodia, Ghana, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka, depend on fish and seafood for over half of their protein intake5. Moreover, coastal indigenous peoples, whether they live in developed or developing countries, are especially reliant on seafood consumption6 and are therefore vulnerable to yield losses caused by overfishing. For these reasons, among others, it is crucial to manage global fish resources sustainably to avoid excessive fishing pressure and prevent the depletion of stocks. Nevertheless, many fish stocks have not been managed sustainably, and are therefore currently overexploited7,8. How would catches be affected, if we switched from the current situation to sustainable management of the global fish stocks? Specifically, how would a maximum sustainable yield (MSY) management strategy, implemented on the global marine fish stocks, affect catches over time? Estimates of global MSY from marine catches vary from 83 to 99 Megatons (Mt)9,10,11,12. Current marine catches are estimated to be 79 Mt, which suggests, considering the variation in the MSY estimates, that total marine catches could, in principle, be increased by 5–26% if the global fish stocks were all managed sustainably. This could potentially improve global food and nutrition security1,13,14.

The main contribution of this paper is to evaluate, the agri-food market impacts of different pathways for global catches, in particular the ones resulting from MSY management and a continuation of current fishing pressures. In contrast to other studies, we do not just consider the effects of fisheries management on catches or the fishing industry. Our scope is broader in the sense that we focus on the resulting impacts on the entire global agri-food markets from the changes to catches. To do this, we combine three distinct databases and their accompanying models: one covering the global fish stocks15, a second covering the global supply and demand for fish, including catches and aquaculture production, based on data provided by the FAO, and, finally, a third covering the global agri-food markets16,17. The two latter models are used in connection with medium term outlook projections for the global markets18,19,20. In this way we are able to account for the total market impact of the MSY catches, and not just the value of the additional catches or profits as is often reported in the literature. This is important because the potential increase in catches associated with a global MSY management scheme is substantial, and it is therefore reasonable to expect that the agricultural markets would be affected as well. The question we try to answer is, how large would these market impacts be, and which sectors would be affected the most?

Global capture fisheries production was estimated to be 90.3 Mt in 2020, most of which (87%) came from marine catches, as opposed to inland fisheries. Catches from small-scale fisheries in particular, may be substantially underreported though, meaning that the actual catches may be larger21,22. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), which defines a sustainable fish stock as one that is maximally sustainably fished or underfished (see the Methods section), estimates that 82.5% of global landings in 2019 were from biologically sustainable stocks. However, only two-thirds of global stocks are classified as being within biologically sustainable levels and this share has been falling over time7,8. In contrast to catches, whose growth has been stagnant since the late 1980s, aquaculture production has experienced a large increase, quadrupling from an average of 22 Mt in the 1990s to 88 Mt in 2020 (excluding algae)8. These trends are expected to continue, so future growth in total fish supply is likely to derive almost entirely from aquaculture18, albeit there is some debate about the feasibility of this23,24. ‘Blue foods’ can be produced in a relatively sustainable manner. However, the projected increase in aquaculture production could have local negative environmental impacts and lead to an increase in global GHG emissions2,25,26.

From an economic standpoint, optimal management of fish stocks entails maximizing the total discounted net economic benefits, or resource rents, from fishing. Due to the open access nature of fisheries resources, this is not the natural market outcome. Without management, due to the lack of property rights, the incentives facing individual fishermen will tend to result in ‘the tragedy of the commons’, which entails over exploitation of the resource, over investment in harvesting capacity, and a complete dissipation of rents27,28. The open access market failure can, in principle be solved by allocating property rights to the natural resource (i.e., the stock of fish) through quotas29 although there are many reasons why this may fail in practice30. Another market-based solution to the open access problem involves a tax on landings31,32. Finally, as pointed out by Ostrom33, under the right conditions, self-organizing social networks are able to manage open access resources sustainably without the need for regulation.

Our focus here is not on fisheries regulation per se, and the many problems associated with regulation, such as inherent uncertainty, asymmetric information, complex dynamics due to multispecies interactions, and noncompliance34,35. Instead, our focus is on the outcome of a successful regulation of global catches that restores the overfished stocks over time.

Fisheries management schemes based on the MSY principle are widespread. This is reflected in the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which states that coastal states must have measures in place ensuring the populations of harvested species at levels that can produce the MSY (art. 61.3). It is also the main principle of the EU Common Fisheries Policy and the US Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act36. MSY management aims to bring the fishery to its most productive state, such that the largest sustainable harvest can be achieved. The MSY harvest level may or may not coincide with the economically optimal harvest level based on a capital theoretic approach, depending on the value of the social discount rate.

Overfished stocks are typically subject to high fishing pressure. MSY management of these stocks requires reducing the fishing pressure, which will allow them to recover. This, however, will have negative impacts on global, or at least regional, food security in the short- to medium term due to lower supply and higher prices. In the longer term, however, rebuilding these stocks to their most productive levels could lead to a sustainable harvest that is larger than the current harvest. Our analysis suggests that the short-term impact of a global MSY management scheme, applied to currently overfished stocks, would be a substantial reduction in catches. However, in the longer long term, the approach could lead to higher catches as overfished stocks recover. Concretely, we estimate that MSY catches from currently overfished stocks (whose MSY share is 37%) are 41 percent higher than the current ones (10.6 Mt), which is equivalent to 12% of total catches and 6% of total aquatic animal production in 2022. Our own estimate of the total global MSY is 98.5 Mt, implying a possible increase in marine catches of 19.7 Mt (25%) if all fisheries were managed to maximize long-term sustainable yields.

Additional food supply from catches would reduce the demand for other protein sources, particularly from the meat and aquaculture sectors, and the derived feed demand for crops and small pelagic fish. The potential higher annual catches of 10.6 Mt that could result from MSY management of currently overfished stocks is equivalent to around 3 years of growth in the aquaculture sector at its current level under average historical growth rates. This would alleviate some pressure on global resources, which is noteworthy in light of the pressure faced by the agricultural sector due to climate change, reduce food prices, and potentially improve food security. Lower prices of food in general and fish in particular would, however, have a negative impact on the livelihoods of farmers in general, fishers, and those employed in the aquaculture sector in particular. On the other hand, larger stocks could lower the required fishing effort and average costs. Although the long-term impact of MSY management on fishing profits is ambiguous a priori, Costello et al.10 found it to be modestly positive overall for the assumed prices and cost parameters used in their study. Nonetheless, rebuilding overfished stocks requires making difficult choices regarding short-term versus long-term food supply, and it entails costs as well as benefits to actors throughout the food system.

Results

Impacts on total catches

Bringing overfished stocks to their MSY levels could, theoretically, increase catches from these stocks by 41% in the long run (Fig. 1, panel B). The share of the total catch from these stocks is 32%; thus, with a current catch of 78.8 Mt from marine stocks, this corresponds to an additional catch of 10.6 Mt (78.8 Mt × 0.32 × 0.41), which would bring the total marine catch to 89.4 Mt.

A Overfished stocks, medium term. B Overfished stocks, long term. C All stocks, medium term. D All stocks, long term. Note: For all panels. The catch projections are relative to the initial year (t0 = 1). FMSY (turquoise lines) denotes the catches resulting from applying MSY fishing pressure to the overfished stocks. Fcurrent (magenta lines) denotes the catches resulting from applying the most recent estimated fishing pressure to all overfished stocks. The blue horizontal lines represent the MSY catches relative to the initial ones.

MSY management of currently overfished stocks will, however, result in lower marine catches in the short- to medium term, which we define as 10–15 years into the future (Fig. 1, panel A). In fact, under MSY fishing pressure, which we refer to as FMSY, it takes 15 years for catches to surpass the initial ones from the overfished stocks. For comparison, we also project the catches that would result from maintaining the harvest rate at a constant level equal to the current (latest reported) one. This we refer to as the Fcurrent rule (see Methods). Under Fcurrent, fishing pressure the catches from overfished stocks would fall by 15% in the long run or 3.9 Mt.

The additional catch of 10.6 Mt resulting from MSY regulation of the overfished stocks is close to the total marine catches of China (reported to be 11.8 Mt in 2020), which is the world’s largest producer of marine catches by far. The potential loss of catches under the Fcurrent rule, on the other hand, is larger than the total marine catches of India (reported to be 3.7 Mt in 2020), which is the sixth largest producer.

Although the impacts on catches from different fishing pressures on the overfished stocks are large, they are dwarfed in comparison with the impacts on catches resulting from management of all fish stocks. As illustrated in Fig. 1, panel D and noted above, total marine catches could increase by as much as 25% (19.7 Mt) in a global MSY scenario involving all fish stocks. If current fishing pressures on all stocks were to be continued on the other hand, it would lead to 14% lower total catches of in the long run corresponding to 10.8 Mt. The fact that the yield increase resulting from MSY management of all stocks is almost twice as large as the one resulting from MSY management of currently overfished stocks shows that many stocks are underutilised, and could therefore potentially contribute more to the global food supply.

Underexploited fish stocks are result of national policies and regulation, as well as consumer preferences and high costs. This means that MSY regulation of all fisheries is not very a realistic scenario. However, in the literature, this is a reference scenario that other scenarios are compared to1,10,26. By including it here, we therefore contribute to the literature with a set of agri-food market impacts resulting from this benchmark.

Impacts on aquaculture and global agri-food markets

Basic economic reasoning suggests that additional supply of calories from a given commodity (such as fish) leads to lower food prices in general and lower supply of other food commodities. Our simulation results confirm this prediction and show that production of aquaculture, which is the closest food substitute, and coarse grains, the main livestock feed, will be particularly affected (Table 1). Aquaculture production depends on the price of fish as well as the costs of feed. Fish markets will react to the increase in capture production through lower prices, which will reduce the profitability of aquaculture production and consequently the incentive to produce in a competitive market and the demand for feed. The demand for meat will also fall due to substitution in consumption. This will reduce the demand for feed in these sectors as well.

The additional 10.6 Mt of catches in the scenario where the currently overfished stocks are subject to MSY management (referred to as FMSY_OF in the table) causes fish prices to fall by 13%, as compared to the baseline, whereas meat and crop prices fall by around 2–3%. The lower demand for feed in the meat and aquaculture sector results in 10.1 Mt lower production of the main crops. Almost two thirds of this is due to lower maize production.

A lower supply of fish resulting from a continuation of the current fishing pressure, Fcurrent, has the opposite effects. In the long term, this leads to fish prices 16% higher and meat and crop prices that are 2–3% higher than in the baseline. The increase in the price of fish stimulates aquaculture production, which increases by 5 Mt compared to the baseline. This result shows that a substantial portion of the change in catches in these scenarios is compensated by a change in aquaculture production. The change in meat production (from agriculture) is more modest in comparison. The combined production of pork, poultry and beef increases by 1.3 Mt in response to the lower supply of fish.

In the FMSY scenario involving MSY management of all fish stock, the price of fish falls by 23%, which causes aquaculture production to fall by 7.3 Mt. The net effect on the supply of fish is therefore an increase of 12.4 Mt. This is similar to the impact reported by Golden et al.1, where a 15 Mt increase in the global supply of fish leads to a 26% reduction in fish prices.

Lower demand for food and especially feed crops in the MSY scenarios leads to changes in global land use patterns but, in general, the changes are modest. The global maize area, for example, decreases by 0.9 and 0.6 Mha in the FMSY and FMSY_OF scenarios, both compared to the baseline. The total agricultural area decreases by 1.6 and 1 Mha, respectively in the two scenarios. In all cases, these changes are less than one percent. Crop yields also decrease modestly in the two MSY scenarios. Conversely, in the long term Fcurrent scenario, higher prices cause crop areas and yields to increase slightly.

Domestic food prices

Domestic food markets are linked to world markets through trade. The modest impacts on world agri-food prices therefore result in modest domestic impacts as well (Fig. 2, panel A). The relatively large world market price impacts on fish, on the other hand, are translated into large domestic price impacts as well (Fig. 2, panel B).

A All food products except fish. Vegetable products (purple fill) include grains, oilseeds, pulses, and roots and tubers. Other processed products ((green fill)) include sugar, high fructose corn syrup, and vegetable oil. Meat (turquoise fill) includes beef, pork, poultry, and sheep and goat. Dairy (orange fill) includes fresh dairy products, butter, cheese, skim milk powder, whole milk powder, casein, and whey. B Fish. Note: For both panels. FMSY_OF denotes the impacts of MSY management of overfished stocks. FMSY refers to MSY managements of all fish stocks Fcurrent refers to the scenario where current fishing pressures are maintained for all stocks. All impacts refer to the catch equilibrium (MSY or the 200th stock projection year for the Fcurrent scenario) compared to the baseline in 2030. The boxplot displays the median, two hinges and two whiskers of a continuous variable distribution. The lower and upper hinges (colored bars) correspond to the first and third quartiles (the 25th and 75th percentiles). The upper whisker extends from the hinge to the largest value no further than 1.5 than the inter-quartile range (IQR), or distance between the first and third quartiles. The lower whisker extends from the hinge to the smallest value at most 1.5 ∗ IQR of the hinge. Data beyond the end of the whiskers are ‘outliers’ points and are plotted individually as dots.

The domestic food price changes are generally smaller, in relative terms, than the corresponding world market ones, due to the existence of consumer price margins. In the FMSY scenario, for example, the median domestic price decrease of fish is 15.1%, whereas the world market price impact is −23.2%, c.f. Table 1. The lower catches resulting from a continuation of the current fishing pressure, Fcurrent, on the other hand, lead to a 15.9% increase in world market prices of fish and a 9.7% increase in domestic prices. This translates into a 24.8% point difference in the median domestic consumer price changes of fish in the Fcurrent and FMSY scenarios.

Consumers react to price changes by substitution in food consumption. Therefore, for example in the Fcurrent scenario, where the median domestic price of fish increase by 9.7%, total food consumption of fish decreases by 4.4 Mt. However, food consumption of meat, vegetable products, and dairy and vegetable oil increases by 1.5, 0.7, and 0.8 Mt, respectively. Although the price of these commodities goes up as well, the relative price changes leads to higher food consumption of food commodities other than fish. Consumers are clearly worse off by the higher prices, but it is important to take these substitution effects into consideration when considering the food security impacts of a change in the supply of fish catches.

Feed market impacts

Protein feed is produced in the crushing sector, where oilseeds and inputs from other sectors are transformed into oil and protein meal. The demand for these inputs depends on the price of protein feed and oil, which, in turn depends on the supply of these inputs themselves as well as on the meat, vegetable oil, and biofuel markets.

Fishmeal is, to some extent, a by-product of catches, so it tends to increase with total catches. However, since most fishmeal is produced from small pelagic fish species that are intended for this use, fishmeal producers respond to price incentives, and the price of fishmeal is determined by supply and demand as in other sectors. The demand for fishmeal comes primarily from the aquaculture sector, and when the price of fish goes down due to additional catches aquaculture production becomes less profitable, so the demand for feed decreases. The net impact on fishmeal production is therefore ambiguous a priori. The price impact, on the other hand, is clear. Additional catches compared to the baseline results in lower fishmeal prices and vice versa. Supplementary Fig. S1 illustrates the world supply and demand changes for fish (aquaculture + catches production) in each of the scenarios. There, it shows that crush demand for (and supply of) fish increases with catches. The same holds for fishmeal production in Table 1. For oilseeds, only a small part of the production is consumed directly as food, so the change in crush demand is essentially the same as the production changes in Table 1.

Discussion

Fish stocks are typically evaluated along two dimensions: their abundance (i.e., overfished or not) and the fishing pressure facing them. Approximately half of the ocean stocks in our fisheries database15 are overfished and two-thirds of the stocks are subject to a fishing pressure that is higher than that leading to MSY (see supplementary Table S1). Note, however, that most of the overfished stocks are very small, so the mean and median values of \(b\) and \(f\) are quite different. In fact, in the majority of the regions, most stocks are overfished and subject to high fishing pressure. These patterns are believed to be largely determined by management practices37,38,39. Hilborn et al.38, for example, report that regions with less developed fisheries management have harvest rates that are, on average, three times larger than regions with intensively managed fisheries and stocks that are half as abundant.

Fish and seafood play an important role in global calorie and protein consumption, particularly in developing nations. Recent estimates from the FAO indicate that in low- and lower-middle-income countries, fish and seafood contribute to 17 and 23% of protein intake, respectively, compared to 13% in high-income countries8. Seafood is a rich source of micronutrients, and higher consumption of fish could contribute to reducing micronutrient deficiencies and improve global food and nutrient security13. Additionally, fisheries and aquaculture serve as a vital source of income for millions of households worldwide21,40. It is crucial to recognize that the livelihood and food security of a substantial number of individuals are directly tied to fish prices. Therefore, any alterations in catch supply will have both winners and losers.

In this paper, we show that the price of fish reacts strongly to changes in catches regimes. For example, the additional catches resulting from long term MSY management of the currently overfished stocks lead to a 13.1% drop in the world price of fish, compared to the baseline. This will benefit the consumers of fish, but the producers, especially from the aquaculture sector, will be worse off from the lower prices. This is reflected in the 4.3 Mt reduction in output from the aquaculture sector, which is 43% of the 10.6 Mt increase in catches. As mentioned in the introduction, more abundant fish stocks typically lead to lower required fishing effort levels on average, and therefore lower costs and increase profitability, assuming that the fishing fleet remains constant. In the absence of government regulation, however, the harvesting capacity of the fishing fleet would tend to increase in response to the higher profitability, which would increase average effort levels and costs. Given the importance of fish in the global diet, a change in the price of fish will have indirect impacts on the price of other food products, both meat and crops, and therefore also on production and consumption. MSY management will lead to lower food prices in general in the longer run, which will benefit consumers. Farmers in general, however, will be affected negatively by the lower prices.

As mentioned, MSY catches may not coincide with the economically optimal (MEY) catches. It is possible, in theory, that the economically optimal stock levels are below the MSY levels, meaning that biological overfishing could be optimal from an economic point of view28. Costello et al.10 found, however, that this was not the case for the prices and cost parameters considered in their analysis. There, the total biomass of the fish stocks were higher and harvests lower in the MEY scenario than in the MSY scenario, when all stocks were subject to management. Profits were also found to be higher, partly due to higher prices in this case and partly because of the composition of the total catch. Costello et al.26 take the analysis a step further by comparing supply curves (production as a function of the price) under different pathways by which sea based food supply could increase including improved management of fish stocks, feed of requirements of mariculture production, and demand shifts. They find that especially the mariculture sector has the potential to satisfy a higher demand for food in the future, driven by population increases and higher incomes.

In our case, we do not consider MEY management nor do we calculate the impacts on sector profits. Our approach is closer to that of Costello et al.26, in the sense that fish production in the model is based on the intersection of supply and demand curves. A key difference is that we consider the impacts of an exogenous change in the supply of caught fish rather than that of a demand shift. The negative impacts on the aquaculture sector of higher catches resulting from improved management has been overlooked in previous studies. However, the main contribution of this study are the estimated impacts of improved fisheries management practices across the entire global agri-food system and not just the fishing industry.

Although the comparison of MSY and MEY catch scenarios is interesting, the fact is that regulators and fishers are faced with incomplete information and fundamental uncertainties related to future price and cost developments, as well as with respect to the resource itself and the models and parameters representing them. Fisheries management under uncertainty and incomplete information, which is a cause of irreversible fisheries collapses41, is an active field of research and we are still far from having a unified approach to the many different types of uncertainties and information failures.

The uncertainty regarding the status of the worlds fish stocks should not be disregarded, though, as it affect the affect reliability of the results of this study. As pointed out by Hilborn et al.38, only around 50% of the global landings, representing an even smaller share of the world’s fisheries, come from stocks whose status has been officially assessed. In fact, our stock dataset (see below), which represents 79% of total 2012 landings as reported to the FAO, is based on so called data limited methods to infer the state of these unassessed stocks mainly from catch data. Some recent studies have called into question the accuracy of these estimates42. While we fully acknowledge this caveat of our study, and agree that more quality stock assessment data is needed, currently there are no alternative datasets covering the global fish stocks, and it is not clear that another modeling approach would produce better estimates of biomass and fishing pressure.

Methods

Our analysis is based on a set of projected catches from each of the individual stocks in the Mangin et al.15 dataset (N = 4702), which, in turn, is based on the Costello et al.10 dataset. Following, e.g., Melnychuk et al.43, a stock where the biomass (size), \({B}_{t}\) at time \(t\) is less than 80 percent of its MSY level (\({b}_{t}={B}_{t}/{B}_{{MSY}} < 0.8\)) is said to be overfished. There are other ways of defining overexploited fish stocks. The classification used in FAO’s flagship report The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture8, is based on a methodology, which classifies the exploitation status of a stock according to a range of criteria incl. the stock abundance, spawning potential, the catch trend, and the size/age composition44. Using a definition that incorporates several indicators allows for a more nuanced analysis that, in principle, can distinguish between stocks that are low due to overfishing or other reasons. For tractability, in this paper we stick to the simpler definition of overfishing.

The stock-specific projections differ with respect to the assumed fishing pressure (also called the harvest rate) \({F}_{t}={H}_{t}/{B}_{t}\), where \({H}_{t}\) represents the catch (harvest) at time \(t\) of the stock in question. The first rule involves harvesting the stock at a rate equal to the one that would apply, in equilibrium, if the fishery was subject to MSY management, that is, \({F}_{t}={F}_{{MSY}}={H}_{{MSY}}/{B}_{{MSY}}\). Fishing pressures under this rule can be written as \({f}_{t}={F}_{t}/{F}_{{MSY}}=1\). Note that this implies harvesting less than the MSY (\({H}_{t} < {H}_{{MSY}}\)) as long as \({B}_{t} < {B}_{{MSY}}\) and vice versa. Over time, this rule will make the stock converge to its MSY level. For comparison, we also project the catches that would result from maintaining the harvest rate at a constant level equal to the current one, which we refer to as the Fcurrent.

In the description of the market impacts, we refer to the three harvest projections as FMSY (\(f=1\)), MSY_OF (\(f=1\) for the overfished stocks), and Fcurrent (\(f={f}_{0}\)). We focus on the equilibrium catches resulting from MSY management or, in case of Fcurrent, the catches in the 200th stock projection year. The MSY harvests are higher than the initial ones, whereas the Fcurrent harvests based on the \(f={f}_{0}\) rule converge to a level well below the initial harvest (Fig. 1).

We use the harvest projections following the three fishing pressure rules as inputs to a scenario analysis involving simulations based on the global agri-food market model augmented with a much expanded capture and aquaculture module. With this approach, we are able to capture the market interactions and the dynamic price impacts of the supply following from MSY management. The outcomes from these simulations were then compared to the baseline projections and the differences in market outcomes were used to calculate the impacts from switching to global MSY management (Table 1).

Status of the global fish stocks and catches

Fish stocks of the world can be described by their abundance or stock size, \({B}_{t}\), and the fishing pressure facing them, \({F}_{t}={H}_{t}/{B}_{t}\), where \({H}_{t}\) is the harvest level or catch in year \(t\). By normalizing these two variables by their MSY level, \({b}_{t}={B}_{t}/{B}_{{MSY}}\) and \({f}_{t}={F}_{t}/{F}_{{MSY}}\), we obtain a useful classification of the stocks. \({f}_{t} > 1\) implies a high fishing pressure, in the sense that it is higher than the one leading to MSY over time. If continued, the stock will eventually stabilize at a level below the MSY level, potentially zero. On the other hand, \({b}_{t}\ne 1\) implies that the stock is above or below its most productive level, such that the sustainable harvest, defined as a catch equal to the natural growth of the stock, is below its maximum. Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of the world’s marine stocks in \(\left(b,f\right)\) space. This so-called Kobe plot is based on data from Mangin et al.15.

The stocks located to the right of the vertical line are all above their MSY level. This means that a larger sustainable catch can be achieved if the stocks are reduced. For the stocks in the upper right quadrant of the figure, where fishing pressure is unsustainably high (\(f > 1\)), stock sizes will decrease if the fishing pressure is sustained. In the lower right quadrant, on the other hand, fishing pressure is too low to bring the stocks to their MSY level. The stocks located on the left side of the vertical line are all characterized by relatively low abundance, meaning they have been overfished or the stock sizes have decreased below the MSY level for other reasons perhaps related to environmental issues.

Whereas the stocks in the lower left quadrant of the figure will increase in size and eventually grow beyond their MSY if the low fishing pressure is maintained, the stocks in the upper left quadrant could increase or decrease in size if the high fishing pressure is maintained, but they will eventually stabilize at a level below BMSY, possibly zero. These dynamics imply that the stocks in the upper right and lower left quadrants will tend to move to the other side of the vertical line, whereas the stocks in the two remaining quadrants will tend to stay there.

The total MSY in the stock dataset is 70.2 Mt. Costello et al.10 report that the global MSY is actually estimated to be 90–110 Mt, so the dataset does not include all stocks9,11,26. Inland fish stocks, in particular, are not represented in the dataset. The implied total catch in the dataset (see below) is 56.1 Mt, which is 71.2% of the estimated actual total marine catch (78.8 Mt) in 20208. Assuming that MSY is directly proportional to catch, the dataset represents a total MSY of 98.5 (70.2/0.71) Mt.

The fisheries stock model and catch scenarios

In the Pella-Tomlinson (PT) parametrization of the surplus production model45,46, the scaled stock (\(b\)) and fishing pressure (\(f\)) coevolve according to the following difference equation

where \(g={F}_{{MSY}}\) and ϕ are parameters determining the natural growth rate of the stock. In the PT model (1), the MSY stock level and MSY can be written

where \(\psi ={\left(\phi +1\right)}^{1/\phi }\) and \(K\) is the carrying capacity of the stock. Implied stocks and catches can be written

We consider the harvest impacts of the FMSY and Fcurrent rules.

Figure 4 illustrates the harvest and stock projections under each of these rules for a representative stock from each of the four quadrants in Fig. 3. The upper panels illustrate the catches and the lower panels illustrate the normalized stock sizes associated with each of the two fishing pressure rules.

Note: For all panels. ‘FMSY’ (turquoise lines) denotes the catches and stock sizes resulting from the applying the MSY fishing pressure to the stocks. ‘Fcurrent’ (magenta lines) denotes the catches and stock sizes resulting from applying the most recent estimated fishing pressure to the stock. Catches are in Kt and in differences from the initial catches. Stock sizes are relative to their MSY levels. Representative stocks from each quadrant in the Kobe plot.

In the first case (top left set of graphs) the initial fishing pressure is high (\({f}_{0} > 1\)) and the stock is overfished (\({b}_{0} < 0.8\)). As shown in the lower panel, if the fishing pressure is maintained at the level of the last year in the dataset (\({f}_{t}={f}_{0} > 1\)), the stock will converge towards a size below the MSY level. Conversely, when the fishing pressure is maintained at the MSY level (\({f}_{t}=1\)) throughout the projection period, the stock and catch converge gradually toward the MSY level, following an initial reduction in catches.

It is important to note that a high and constant fishing pressure (\({F}_{t}=F > {F}_{{MSY}}=g\)) does not necessarily lead to a complete depletion of the stock (c.f. Fig. 4, upper left set of figures, lower panel). Whether and how fast this happens depends on the harvest level \(H\), the stock size \(B\), and the parameters \(g\) and \(\phi\) determining the natural growth of the stock. A constant harvest \(H > {MSY}\) will, however, always lead to a depletion of the stock over time.

In the second case (top right set of graphs) where the initial fishing pressure is high (\({f}_{0} > 1\)), but the stock is underexploited (\({b}_{0} > 1\)), both fishing pressures lead to lower catches (and stocks), but the Fcurrent rule will result in higher catches in the medium term, whereas the FMSY rule leads to higher catches in the long term.

The third case (bottom right set of graphs) is also interesting. There, the initial fishing pressure is below MSY levels (\({f}_{0} < 1\)), but the stock is underutilized (\({b}_{0} > 1\)). There, FMSY leads to higher catches and lower stocks than Fcurrent. This is also the case in the fourth case (bottom left set of graphs). Individual stock level projections, such as those in Fig. 4 are the basis for the scenario catches used in the simulations (see below). Tables S2 and S3 in the Supplementary material shows the top-20 and bottom-20 contributions to the total yield changes under the FMSY_OF rule.

The catch and aquaculture production model and database

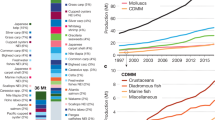

The data on actual global catches going into the scenario analysis come from the Seafood Market Simulation Model (SEASIM) and database developed and maintained by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), Government of Canada20. It is based on data provided by the FAO, and the structure of the model is derived from the model used by the FAO in connection with their fisheries market projections8. The version of SEASIM that we use is divided into 9 geographic components and covers 12 aggregate species/taxa of marine animals, incl. fish, crustaceans, and mollusks in addition to fishmeal and fish oil. The geographic components are Canada, USA, China, Japan, South Korea, EU-27, Norway, UK, and the rest of the world (ROW). The 12 species/taxa covered are: salmonid (SAL, part of the diadromous category), tuna type (TUNA, part of the pelagic category), other pelagic fishes (OPE), freshwater fish and other diadromous fishes (FWOD), all other marine fishes (OMF), shrimp (SHP), lobster (LT), crab (CB), other crustaceans (OCR), molluscs (MLC), cephalopods (CEPH) and other species (OSP). For simplicity, we use the term ‘fish’ to refer to all of these species.

Supply of fish is divided into catches (or wild harvests), which are exogenous for all regions except for certain species in ROW, and aquaculture production, which depends on the price of inputs and output. The model and underlying database does not have separate prices for farmed fish and wild catch fish. Catches of 10 species in the ROW region depends positively on the price of the species in question. Fishmeal and -oil production, important feed components in aquaculture as well as the agricultural livestock sector, depend on the price of the fish species used as inputs as well as their own prices. Supplementary Fig. S1 illustrates the historical values and projections to 2030 of global catches, fishmeal and -oil, and aquaculture production. Note the strong increase in aquaculture production, which means that aquaculture now contributes more global food consumption than catches8.

Merging the catch and aquaculture model with an agricultural market model

To analyze the impacts of MSY management on the global agri-food markets, we merged the catch model with a model of the global agri-food markets called Aglink-Cosimo, which comes with a baseline for the global agricultural markets used for scenario analysis and for ex-ante impact assessment18,47,48. This model is maintained by the secretariats of the OECD and the FAO and contains market projections for 35 individual countries and 12 regional aggregates. It covers more than 90 commodities, of which 29 have a price that clears at the international level16,17. Similar to the SEASIM model, Aglink-Cosimo is an annual recursive-dynamic partial equilibrium model with a global scale, but with a different coverage in terms of products and geographic aggregations.

Aglink-Cosimo includes food demand for fish, feed demand for fishmeal, and biofuel demand for fish oil, but the supply and demand for these commodities is exogenous. In the combined Aglink-Cosimo-SEASIM model, on the other hand, fishmeal and -oil supply is endogenous and linked to fish supply.

General structure of the merged model

Both models are based on a set of commodity market balances, where the equilibrium prices ensure that demand and supply are in line. That is, for each commodity in the combined model, the following identity will always hold

where \(Q{P}_{c,p,t}\) denotes production of product \(p\) in country \(c\) at time \(t\), \({IM}\) imports, \(S{T}_{t-1}\) opening stocks, \({QC}\) consumption, \({EX}\) exports, and \(S{T}_{t}\) closing stocks. Not all commodities are traded or stocked, however, so, for these commodities, \({QP}={QC}\). On the demand side, consumption is divided into several uses incl. food, \({FO}\), feed, \({FE}\), biofuels, \({BF}\), crushing, \({CR}\), and other uses, \({OU}\).

A country’s total imports and exports of each traded commodity are functions of the domestic price relative to the world market price, both measured in the domestic currency, and where the world market price has been adjusted for import and export tariffs and quotas, in ad valorem equivalents. The world market price is simply the price (in USD/t) that clears the world market such that total exports from all sources equal total imports across all destinations.

Food demand

The standard food demand function in the model takes as input the consumer price of 24 products deflated by the consumer price index (CPI) as well as the per capita GDP

where \({foodP}\) is the set of food products with an associated own- and cross price elasticity, \({CP}\) is the consumer price, \({POP}\) is the population, \({GDPI}\) is the real GDP normalized to 2010 = 1, and \({\tau }_{c,p,t}\) is a trend term. The own price elasticity is always negative and the cross price elasticities are always positive. The sign of the income elasticity, on the other hand, depends on the country as well as the type of product. It is positive for animal products and, in some cases, negative for grains.

Food demand for fish, \(F{O}_{c,{FH},t}\), is exogenous in the Aglink-Cosimo model. However, in the combined Aglink-Cosimo-SEASIM model, it is endogenous in the 9 SEASIM regions mentioned above, including ROW. It is defined as the sum of the demand for the individual fish species, where the food demand function for these is similar to (5), but it includes elasticities for the price of individual species.

The consumer price of food, on the other hand, which is also exogenous in Aglink-Cosimo, is endogenous in all regions of the joint model. In the non-SEASIM regions, it depends on the price of fish in ROW, which, in turn, is defined as a weighted average of the price of the individual fish species. In the 9 SEASIM regions, it depends on the weighted average of the individual species within the region itself.

It is important to note that this setup makes it difficult to analyze the impact on food consumption at the domestic level in the full set of Aglink-Cosimo countries (since fish consumption is exogenous in most of these countries). However, the impact at the world level is readily available. As mentioned, the cross-price effect of changes to the price of fish on the consumption of other food products is also taken into account in all Aglink-Cosimo countries.

Production of animal products

As mentioned, captches of several species in ROW is endogenous in SEASIM. However, for this analysis we exogenized all catches. Animal production functions, including aquaculture, take the following general form

where \({PP}\) is the producer price, \({FECI}\) is a feed cost index, \({CPCI}\) is an exogenous production cost index depending on the price of energy and other inputs, and \(X\) represents additional terms such as animal inventories, autoregressive terms, and trends. The number of lags (\(S1\), \(S2\)) and parameter values (\({k}_{c,p}\), \({\beta }_{c,p,s}\), \({\gamma }_{c,p,s}\), \({\delta }_{c,p}\)) depend on the species and region in question. For example, the EU poultry production function only includes contemporaneous terms, whereas the EU beef and veal production function includes two lags of the price terms and three lags of the feed cost terms, in addition to two lags of the cow inventory and a trend term. The salmon production function includes only the second lag of the two terms as well as an autoregressive term. The coefficients (elasticities) to the price terms, \({\beta }_{c,p,s}\) are positive, whereas the coefficients to the feed cost terms, \({\gamma }_{c,p,s}\) are negative.

The feed cost index, \({FECI}\), differs between the animal products in the agricultural sector (beef and veal, milk, pork, poultry, eggs, and sheep and goat meat) and the species produced in the aquaculture sector. In the latter sector, it is defined as the average price of fishmeal (\({FM}\)), protein meal from the agricultural sector (\({PM}\)), fish oil (\({FL}\)), vegetable oil (\({VL}\)), and crop-based low-protein feed (\({LPF}\)), weighted by fixed product specific input shares. In the agricultural sector, on the other hand, \({FECI}\) is defined as the average cost per ton across all feeds, high-, medium-, and low-protein, \(P{P}_{{APF}}\) (see below).

Feed supply and demand

Total (protein) feed demand is divided into demand for low-, medium-, and high protein feed

where the three aggregates on the RHS are simply the sum of the individual products included in each of the categories. The low-protein feed aggregate (LPF) include maize, other coarse grains, wheat, cereal brans, beet pulp, molasses, rice, and roots and tubers. The medium-protein feed aggregate (MPF) include corn gluten feed, dried distillers grains, pulses, and whey powder. Finally, the high-protein feed aggregate (HPF) include protein meal from crops, fish meal, meat- and bone meal, and skim milk powder. The associated average price of feed is given by

where the prices of the three feed aggregates are defined in a similar manner. The price of the \({LPF}\) aggregate, for example, is given by

where LPFP denotes the set of products included in the LPF category. Demand for feed comes from the livestock sector, which is divided into the ruminant (\({RU}\)), nonruminant (\({NR}\)), and aquaculture (\({FHA}\)) sectors

where the NR feed demand depends on the production of pork, poultry, and eggs, the feed conversion ratio of pigs, broilers and laying hens, and the so called carcass yield of pigs and broilers. The FHA feed demand is modeled as the sum of feed from cereals, fish meal and crop-based protein meal, which depend on fixed shares and on the aquaculture production levels of the individual species. The RU feed demand is calculated as the residual.

Feed demand of the individual products included in each of the three categories (\({LPF}\), \({MPF}\), and \({HPF}\)) depends on ruminant-based meat production, the price of the feed and its substitutes, on feed demand from the non-ruminant and aquaculture sectors, and on a trend

where \({\beta }_{c,{NR}}{{{\rm{:= }}}}1-{\sum}_{p\in {RUMP}}{\beta }_{c,p}-{\beta }_{c,{FHA}}\). \({RUMP}\) denotes the set of products included in the ruminant category (beef and veal, sheep and goat, milk) and \({FEEDPEQ}\) the set of individual feed commodities, i.e., grains, pulses, protein meals, etc. The elasticities to the production terms, \(Q{P}_{c,p,t}\), are positive, as are the elasticities to the two sectoral feed demand terms, \(F{E}_{c,{NR},t}\) and \(F{E}_{c,{FHA},t}\). Cross price elasticities are also positive whereas the own price elasticity is negative.

The supply of protein meal from crops, \(Q{P}_{{PM}}\), is defined as the sum of meal from oilseeds, \(Q{P}_{{OM}}\), and meal from other sources. (These include meal from palm kernels, copra, and cotton seeds.) Fishmeal supply in a given region is defined as the fish crush availability times the fishmeal yield plus a waste term

where the latter, depending on the region, is calculated either as a residual or as a fixed share of fish food consumption.

Crush availability from fish is the sum of availability from the individual 12 fish species, where the majority comes from the ‘other pelagic fishes’ category. The crush supply/demand function for each of the fish species depends positively on the catch of the species, as well as the price of fishmeal, \(P{P}_{{FM}}\), and fish oil, \(P{P}_{{FL}}\), and negatively on the price of the species in question

where the fishmeal and -oil yields, \({YLD}\), are exogenous. Fish oil supply is calculated in a similar manner.

The oilseed meal equation is very similar to that for fishmeal (12). It is the product of oilseed (soybean and other oilseeds) crush availability times the oilseed meal yield. The crush availability of oilseeds, however, depends (positively) on the crushing margin, \({CRMAR}\), i.e., the revenue from crushing, relative to the cost, per ton of oilseed input. For soybean (\({SB}\)), for example, the crushing margin equation is

where \({SM}\) denotes soymeal, and \({SL}\) soy oil. The market equilibrium and associated prices are described below.

Catches in each of the scenarios (the scenario assumptions)

Each of the scenarios analyzed here is defined by the assumed levels of catches of each of the 12 aggregate fish species included in the merged Aglink-Cosimo-SEASIM model. The scenario shocks, which are used to calculate the catch projections in each scenario, are based on the series illustrated in Fig. 1. These were obtained by summing over the individual stock level projections, normalizing with the total catch in the starting year.

Assuming either MSY management of all stocks or Fcurrent fishing pressure, catches were obtained by multiplying the 2020 marine catches by the corresponding index values in panel C. The baseline marine catches were obtained by multiplying the baseline catches by the ratio of marine catches to total catches in 2020 (78.8/90 = 0.88). The scenario catches were then obtained by multiplying the calculated marine baseline catches with the scenario index values, adding the calculated baseline inland catches.

In the simulations involving MSY regulation of overfished stocks only, we did not simply multiply the baseline marine catches with the index values from panel A of Fig. 1, as this would have led to incorrect scenario catches. Instead, we used the calculated catches from the stock dataset under the two MSY rules, and defined two new sets of catch projections equal to the MSY projections for the stocks characterized by \(b < 0.8\) in the base year and the catch levels for the latest year in the dataset for the remaining stocks. Then, we recalculated the indexes by aggregating the catch over all stocks and normalizing with the value in the base year. Finally, we produced the scenario catches by multiplying the baseline marine catches with the modified index values, adding the inland catches as above.

In order to deal with the differing time horizon of the two sets of projections (the 10-year ahead projections from Aglink-Cosimo-Seasim and the 200 year ahead projecitons from the stock model), we replaced the harvest projections from the stock model for years 6–11, with the projected harvests for years 10, 25, 50, 100, 150, and 200. In this way, we impose the long-term catches resulting from MSY regulation of either all stocks or only the initially overfished stocks, on the medium-term scenario catches. Similarly with the Fcurrent catches.

For simplicity, in the scenarios, we change each region’s baseline catches of each of the species by the same proportion. This, of course, makes it problematic to analyze the regional impacts but at the global level, it has a negligible effect on the results.

Updating the stock dataset with information from the most recent RAM Legacy database

The stock dataset15 used in this paper is partly based on an early version of the RAM Legacy Stock Assessment Data Base49. Therefore, in this section we first investigate the extent to which the RAM stocks in the Mangin et al.15 dataset correspond to the ones included in the current version of the RAM database50. Then, we modify the Mangin et al.15 dataset by exluding the RAM stocks, which cannot be identified in the RAM database50, update the parameters of the stocks that can be identified, and add the stocks in the RAM database50 that are not in the Mangin et al.15 dataset, when the required information on the parameters is there.

In the Mangin et al.15 dataset the parameters from 386 out of the 4702 individual stocks included are from the RAM Legacy Stock Assessment Data Base. The data sources and processes are described in the appendices to Costello et al.10 and Costello et al.26. These relatively few stocks, however, represent a total MSY of 33.2 Mt or 45% of the total MSY in the dataset. The current version of the RAM database contain information on 1436 fish stocks, but the dataset is far from complete. In fact, only 684 of these have data on at least some of the parameters needed for the projections. We are able to match 339 of the 386 RAM stocks in our dataset with the stocks in the RAM database50, meaning that 47 of the stocks in our dataset, representing a total MSY of 7.9 Mt could not be identified in the RAM database50. For the analysis presented in this section we remove these 47 stocks from the dataset.

On the other hand, as mentioned above, there are also many stocks in the RAM database50 that cannot be identified in the Mangin et al.15 dataset. It is, however, less straightforward to update the Mangin et al.15 dataset with these stocks than it is to remove the ones that cannot be identified in the RAM database50. The reason is that the RAM database50 contains many missing values of the key parameters used in the stock projections based on the PT model. In fact, only 14 of the 345 stocks in the RAM database50, that are not in the Mangin et al.15 dataset, have data on the required parameters. These stocks represent a total MSY of 1.6 Mt. For the analysis in this section, we add these stocks to the dataset.

Finally, for the majority of the 339 matched RAM stocks, it is possible to update a subset of the parameters used in the PT projections. After removing the stocks that could not be identified in the RAM database, adding the new ones, and updating the parameters of the matched RAM stocks, we are left with a dataset containing information on 4669 individual fish stocks.

The results of this update are summarized in Table S6 in the supplementary material. The main difference compared to the results in Table 1 is that Fcurrent rule leads to larger yield reductions and higher prices increases, whereas the FMSY and FMSY_OF rules lead to smaller yield increases and lower price decreases.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study, incl. figure source data, are available under the Joint Research Centre Data Catalogue (https://data.jrc.ec.europa.eu/dataset/17122198-817d-46f8-b4ec-f0784a892083).

Code availability

All code used to conduct the study is available under the Joint Research Centre Data Catalogue (https://data.jrc.ec.europa.eu/dataset/17122198-817d-46f8-b4ec-f0784a892083).

References

Golden, C. D. et al. Aquatic foods to nourish nations. Nature 598, 315–320 (2021).

Bianchi, M. et al. Assessing seafood nutritional diversity together with climate impacts informs more comprehensive dietary advice. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 188 (2022).

Gephart, J. A. et al. Environmental performance of blue foods. Nature 597, 360–365 (2021).

Kelleher, K. et al. Hidden harvest: the global contribution of capture fisheries. (World Bank Group, Washington, D.C., 2012).

FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020: Sustainability in action. (Rome, 2020).

Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., Pauly, D., Weatherdon, L. V. & Ota, Y. A global estimate of seafood consumption by coastal indigenous peoples. PloS ONE 11, e0166681 (2016).

Pauly, D. et al. Towards sustainability in world fisheries. Nature 418, 689–695 (2002).

FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022: Towards Blue Transformation. (FAO, Rome, 2022).

Sumaila, U. R. et al. Benefits of rebuilding global marine fisheries outweigh costs. PloS ONE 7, e40542 (2012).

Costello, C. et al. Global fishery prospects under contrasting management regimes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 5125–5129 (2016).

Kelleher, K., Willmann, R. & Arnason, R. The Sunken Billions. (World Bank Publications, 2009).

Ye, Y. et al. Rebuilding global fisheries: the world summit goal, costs and benefits. Fish. Fish. 14, 174–185 (2013).

Hicks, C. C. et al. Harnessing global fisheries to tackle micronutrient deficiencies. Nature 574, 95–98 (2019).

Srinivasan, U. T., Cheung, W. W. L., Watson, R. & Sumaila, U. R. Food security implications of global marine catch losses due to overfishing. J. Bioecon. 12, 183–200 (2010).

Mangin, T. et al. Data from: The future of food from the sea [Dataset]. Dryad https://doi.org/10.25349/D96G6H (2021).

OECD/FAO. The Aglink Cosimo Model: A partial equilibrium model of world agricultural markets. (OECD and FAO, 2022).

Pieralli, S., Chatzopoulos, T., Elleby, C. & Perez Dominguez, I. Documentation of the European Commission’s EU Module of the Aglink-Cosimo Model: 2021 Version. EUR 31246 EN (Publications Office of the European Union, 2022).

OECD/FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2022–2031. https://doi.org/10.1787/f1b0b29c-en (OECD Publishing, Paris, 2022).

EC. EU agricultural outlook for markets, income and environment, 2022–2032. European Commission, DG Agriculture & Rural Development, Brussels (2022).

DFO. Outlook to 2027 for Canadian Fish and Seafood. Fisheries and Oceans Canada (2018).

FAO, Duke University & WorldFish. Illuminating Hidden Harvests: The contributions of small-scale fisheries to sustainable development. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc4576en (Rome, 2023).

Pauly, D. & Zeller, D. Catch reconstructions reveal that global marine fisheries catches are higher than reported and declining. Nat. Commun. 7, 10244 (2016).

Edwards, P., Zhang, W., Belton, B. & Little, D. C. Misunderstandings, myths and mantras in aquaculture: Its contribution to world food supplies has been systematically over reported. Mar. Policy 106, 103547 (2019).

Sumaila, U. R. et al. Aquaculture over-optimism? Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 984354 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Bleeker, A. & Liu, J. Nutrient discharge from China’s aquaculture industry and associated environmental impacts. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 045002 (2015).

Costello, C. et al. The future of food from the sea. Nature 588, 95–100 (2020).

Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons: the population problem has no technical solution; it requires a fundamental extension in morality. Science 162, 1243–1248 (1968).

Munro, G. R. & Scott, A. D. The economics of fisheries management. in Handbook of natural resource and energy economics. (Elsevier, 1985).

Arnason, R., Eggert, H. & Jensen, F. Strong user rights in fisheries: an editorial note. Mar. Policy 161, 106009 (2024).

Clark, C. W., Munro, G. R. & Sumaila, U. R. Limits to the privatization of fishery resources. Land. Econ. 86, 209–218 (2010).

Anderson, E. Taxes vs. quotas for regulating fisheries under uncertainty: a hybrid discrete-time continuous-time model. Mar. Resour. Econ. 3, 183–207 (1986).

Weitzman, M. L. Landing fees vs harvest quotas with uncertain fish stocks. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 43, 325–338 (2002).

Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 325, 419–422 (2009).

Jensen, F., Frost, H. & Abildtrup, J. Fisheries regulation: a survey of the literature on uncertainty, compliance behavior and asymmetric information. Mar. Policy 81, 167–178 (2017).

May, R. M., Beddington, J. R., Clark, C. W., Holt, S. J. & Laws, R. M. Management of multispecies fisheries. Science 205, 267–277 (1979).

Mesnil, B. The hesitant emergence of maximum sustainable yield (MSY) in fisheries policies in Europe. Mar. Policy 36, 473–480 (2012).

Hilborn, R. & Costello, C. The potential for blue growth in marine fish yield, profit and abundance of fish in the ocean. Mar. Policy 87, 350–355 (2018).

Hilborn, R. et al. Effective fisheries management instrumental in improving fish stock status. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 2218–2224 (2020).

Melnychuk, M. C. et al. Identifying management actions that promote sustainable fisheries. Nat. Sustain. 4, 440–449 (2021).

Teh, L. C. L. & Sumaila, U. R. Contribution of marine fisheries to worldwide employment. Fish. Fish. 14, 77–88 (2013).

Sethi, G., Costello, C., Fisher, A., Hanemann, M. & Karp, L. Fishery management under multiple uncertainty. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 50, 300–318 (2005).

Ovando, D. et al. Improving estimates of the state of global fisheries depends on better data. Fish. Fish. 22, 1377–1391 (2021).

Melnychuk, M. C. et al. Global trends in status and management of assessed stocks: achieving sustainable fisheries through effective management. (FAO, 2020).

FAO. Review of the state of world marine fishery resources. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 569. (FAO, Rome, 2011).

Milner, B. Schaefer. Some aspects of the dynamics of populations important to the management of the commercial marine fisheries. Bulletin. Inter-Am. Trop. Tuna Comm. 1, 25–56 (1954).

Pella, J. J. & Tomlinson, P. K. A generalized stock production model. Bull. Inter-Am. Trop. Tuna Comm. 13, 421–458 (1969).

Elleby, C., Domínguez, I. P., Adenauer, M. & Genovese, G. Impacts of the covid-19 pandemic on the global agricultural markets. Environ. Resour. Econ. 76, 1067–1079 (2020).

Jensen, H. G., Elleby, C. & Domínguez, I. P. Reducing the European Union’s plant protein deficit: options and impacts. Agric. Econ. 67, 391–398 (2021).

Ricard, D., Minto, C., Jensen, O. P. & Baum, J. K. Examining the knowledge base and status of commercially exploited marine species with the ram legacy stock assessment database. Fish. Fish. 13, 380–398 (2012).

RAM. RAM Legacy Stock Assessment Database v4.64 [Dataset]. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10499086 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The paper is based on work carried out by Pierre Charlebois, linking the Aglink-Cosimo and the SEASIM models. We would like to acknowledge Fisheries and Oceans Canada for their assistance in producing medium-term projections for global fish and seafood markets. We thank Christopher Costello, University of California and Roger Martini, OECD, for their valuable inputs. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the European Commission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.E. and I.P.D. conceived the study. C.E. and I.P.D. contributed to the study design. C.E. and I.P.D. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data. C.E., I.P.D., R.N., M.N., and A.H. contributed to the interpretation of results. C.E., I.P.D., R.N., M.N., and A.H. wrote and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

: Communications Earth & Environment thanks Rashid Sumaila and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Fiona Tang and Martina Grecequet. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elleby, C., Domínguez, I.P., Nielsen, R. et al. Introducing maximum sustainable yield targets in fisheries could enhance global food security. Commun Earth Environ 6, 33 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01851-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01851-4

This article is cited by

-

Benefits and Perils of Integrated Data Systems in Managing Sustainable Fishing Quotas

Environmental and Resource Economics (2025)