Abstract

The response of European precipitation variability to climate change is still poorly understood. Here we present a high-resolution speleothem record of Eastern Central European (ECE) autumn/winter precipitation to study decadal to centennial hydroclimatic variations in the European-Atlantic sector since the Last Glacial Maximum. The Cloşani Cave δ18O record shows that the reorganization of the North Atlantic jet following the demise of the Northern Hemispheric ice sheets lasted until c. 6000 to 5000 years before present. Trace element-derived semi-quantitative autumn/winter precipitation amount reveals that the late Glacial and the early to mid-Holocene experienced about 20–30% higher precipitation than present. During the deglaciation, we detect an increased decadal to centennial precipitation variability decoupled from millennial-scale North Atlantic temperature changes. The findings suggest that dynamic (rather than thermodynamic) processes determine regional precipitation variability and the probability of extreme precipitation events in ECE, highlighting the importance of understanding such dynamics for future predictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The North Atlantic jet stream (NAJ) is a relatively narrow belt of strong westerly air flow crossing the North Atlantic in a southwest-to-northeast direction, where extratropical cyclones are statistically most common1,2. In the European mid-latitudes, the NAJ plays a mediating role between large-scale patterns of atmospheric variability, synoptic weather regimes, and regional precipitation patterns and climates3. In particular during the cool season, the winter NAJ (NAJw) is the dominant driver of precipitation patterns in Eastern Central Europe (ECE), where hydroclimate is influenced by moisture from both the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean Sea4,5,6. In addition, the occurrence of extreme precipitation events in ECE has been linked to NAJ variability in particular during the autumn/winter season, which modulates the occurrence of distal outbursts of cold and dry Siberian air and the intrusion of moisture by Mediterranean cyclones7,8. Both thermodynamic processes and large-scale atmospheric dynamics exert a major influence on the strength and trajectory of the NAJ9,10. In the European-Atlantic sector (EAS), the latitudinal temperature gradient (LTG) between the equator and the pole is a dominant driver of the strength of the NAJ and extratropical cyclones9,11. Arctic warming weakens the LTG and reduces the zonal mid-latitude westerly winds11,12. However, dynamic processes related to climate change could play at least an equally important role, which makes future projections difficult9,10,13,14,15. The limited understanding of the response of NAJ and precipitation variability to climate change is partially hampered by relatively short observational records3,13. Recent studies, such as a 2500-yr-long reconstruction of NAJw strength using ECE stalagmite δ18O records, suggest that the modern NAJw4 and the associated atmospheric and precipitation patterns7 may have already deviated from their natural variability range under anthropogenic warming. Since the current global warming has a strong effect on LTG due to Arctic amplification, reconstructions of past precipitation and atmospheric dynamics can thus inform on future hydroclimate changes in Central Europe.

Paleoclimate records have shown that the large-scale atmospheric circulation over the EAS modulated regional hydroclimate over the last thousands of years in response to changes in insolation, LTG, sea-ice cover, or the extent of the Laurentide and Fennoscandian ice sheets (e.g., refs. 5,11,15,16,17,18,19,20). For example, during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, c. 25–18 ka BP), the Northern Hemispheric ice sheets induced a southward shift of the NAJ and the polar front, affecting hydroclimate regimes in Central and Southern Europe18,19,21,22. For ECE, however, the available paleoclimate information beyond the Holocene is limited (e.g., refs. 23,24,25), and relies on a few studies and records of mostly low resolution25,26,27. A number of speleothem and other paleoenvironmental records has informed about the Holocene evolution of ECE hydroclimate5,25,28,29,30,31. For example, the results of Cleary, et al.31 from a guano-derived δ15N record in Măgurici Cave, NW Romania, advocate for a long-term North Atlantic influence on ECE winter precipitation. Persoiu, et al.5 reconstructed cold season temperature and moisture source changes in ECE for the Holocene, based on a stable oxygen isotopic record of Scărișoara cave ice. They interpreted their results in terms that the NAJw was weaker during the early Holocene, and increased in strength in the late Holocene.

While some studies suggested that the North Atlantic sea-level pressure (SLP) centres of action, and as a consequence, the NAJw experienced substantial reorganization in response to Northern Hemispheric climate change16, little is known about the actual response of regional ECE precipitation amount and variability to these or similar changes.

Here we present trace element and stable isotope records of several stalagmites from Cloşani Cave, Romania, which extend the ECE hydroclimate record back to c. 20 ka BP, i.e., into the LGM. Cloşani Cave is located in southwestern Romania at 45.1°N and 22.8°E (Fig. 1). The seasons are characterized by strong temperature and infiltration contrasts, i.e., warm summers with low amount of infiltration, and cold and wet winters (Fig. 1A). Therefore, infiltration (or effective rainfall) at the site is dominated by autumn/winter precipitation amount, since nearly all precipitation is lost by potential evapotranspiration during the summer months (Fig. 1A). Autumn/winter precipitation amount at the site is representative for ECE as indicated by the correlation between local vs. regional precipitation (Fig. 1B). Spatial correlation with zonal 850 hPa wind speed anomalies from reanalysis data illustrates that wetter conditions in ECE correspond to a more southerly (and weaker) NAJw, and vice versa (Fig. 1C). As a consequence, due to the characteristic isotopic fingerprint of the dominant moisture sources associated with these two dominant NAJw modes (the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean), ECE stalagmite δ18O values can be regarded as proxies for past NAJw strength4. During years when the NAJw is strong, the NAJw extends eastward and the relative contribution of moisture from the North Atlantic increases, resulting in lower precipitation (and speleothem) δ18O values, and vice versa4,5. In addition, speleothem Mg/Ca ratios from Cloşani Cave are a measure for infiltration which is determined by autumn/winter precipitation amount30. This combination of proxies makes Cloşani Cave an ideal location to study precipitation variability in the region and its links to the large-scale atmospheric circulation, i.e., NAJw strength, on decadal to millennial timescales.

A Monthly climate data in SW Romania from meteorological stations Târgu Jiu (TJ) and Drobeta/Turnu Severin (DTS) averaged for the period 1961–1990 CE. B Location of Cloşani Cave (white star) as well as other sites discussed in this study (grey symbols). Background shows the spatial correlation of averaged Oct–Mar precipitation from five GHCNm stations near Cloşani Cave with averaged Oct–Mar CRU TS4.07 precipitation data for the years 1901–2018 CE. C Same as background in B but compared to NAJw strength represented by 850 hPa zonal wind anomalies (relative to 1991–2020 CE) obtained from the ERA5 reanalysis dataset. Spatial correlation maps were created with KNMI Climate Explorer88. Maps in B, C show only significant correlation patterns (p < 0.1).

Results

Chronology of Cloşani cave speleothems

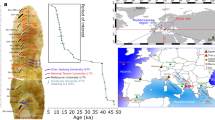

We studied three stalagmites STAM4, C09-1 and C09-2 from different locations in Cloşani Cave, with STAM4 and C09-2 collected beneath active drip sites (Fig. 2A, B). 230Th/U dating yielded growth between 20.45 ± 0.39 and 2.14 ± 0.39 ka BP for C09-1 (where BP refers to the year 1950) (Fig. 2C). Two major hiatuses were identified at 14.5 and 2.4 cm distance from top (dft), spanning from 10.94 ± 0.47 to 7.92 ± 0.36 ka BP and from 3.78 ± 0.53 to 2.72 ± 0.34 ka BP, respectively. Stalagmite C09-2 covers 9.65 ± 0.43 ka to modern, with one 3.8 ka long lasting hiatus at 47.6 cm dft between 7.60 ± 0.30 and 3.81 ± 0.13 ka BP. Overlapping sections of C09-1 and C09-2 are between 7.92 ± 0.36 and 7.60 ± 0.30 ka BP, and 2.72 ± 0.34 to 2.14 ± 0.39 ka BP. Typical U concentrations are in the range between 30 and 90 ng/g. Initial Th contamination is moderate and leads only to minor corrections for ages with (230Th/232Th) activity ratios <100 (Tables S1 and S2). The average annual growth rate of stalagmite C09-1 ranges between 10 and 100 µm/a, and between 50 and >300 µm/a for C09-2. Combined layer counting and radiocarbon measurements attest to a growth period for stalagmite STAM4 from 1910 to 2010 CE32. STAM4 has an average growth rate of 510 μm/a, as deduced from counting of trace element cycles. The layer counting chronology of the two 20th century speleothem records of C09-2 and STAM4 has uncertainties of ±3 yr for C09-230 and ±6 yr for STAM432. Overall, the three speleothems cover the past 20.45 ka within total only a c. 1300 yr-long gap between 10.94 and 9.65 ka BP (Fig. 2C).

A Map of Cloşani Cave with locations of stalagmites C09-1, C09-2 and STAM4, as well as the locations of the drip sites CC1-3 in the Crystals Passage and CL1-3 in the Laboratory Passage. B Scans of stalagmites STAM4, C09-1 and C09-2. C Age-depth models of stalagmites C09-1 and C09-2 constructed with ‘Bchron’78 using the 230Th/U ages reported in Tables S1 and S2.

Speleothem trace elements as semi-quantitative predictor of ECE autumn/winter precipitation

The composite of the Cloşani speleothem records provides a coherent picture of the transition from the end of the last glacial period until modern times with an annual resolution for trace elements and a sub-decadal to decadal resolution for δ13C and δ18O values (see Supplementary Fig. S1). For the modern Mg/Ca ratios in speleothem C09-2, a significant anti-correlation with autumn/winter precipitation amount on multi-annual to decadal scale has been previously demonstrated and attributed mainly to prior calcite precipitation (PCP)30. PCP occurs when CO2 degasses from seepage water prior to the stalagmite top in cavities in the host rock and/or on the cave ceiling, leading to a supersaturated solution and subsequent calcite precipitation. Since Ca2+ is preferentially removed during calcite precipitation compared to Mg2+, this process results in an increase in the Mg/Ca ratio of the remaining solution. Once the drip water reaches the top of the stalagmite, the elevated Mg/Ca ratio is captured by the growing speleothem. Thus, more PCP leads to higher Mg/Ca ratios. In addition, incongruent calcite dissolution (ICD) of the host rock, i.e., the enhanced dissolution of Mg from the limestone during longer water residence times, can additionally raise the initial Mg/Ca ratio of the solution33. PCP and ICD are related to the amount of water infiltrating through the soil and karst zone, and have thus been linked to precipitation amount above the cave34.

The interpretation of speleothem Mg/Ca ratios as a precipitation proxy was based on a single speleothem record, CO9-2, and the characteristics of its drip site30. In this study, the relationship is substantiated by additional evidence, which allows to extend our interpretation to speleothem records from the same cave that did not have an active drip when collected. The trends observed in drip water data from a total of six drip sites in both cave passages, the Crystals and the Laboratory Passages (Supplementary Fig. S2), fall in the range of observed and simulated slopes of ln(Mg/Ca) vs. ln(Sr/Ca) for the presence of PCP and ICD35,36. In addition, an overall positive correlation of Mg/Ca ratios with δ13C values in both stalagmites C09-1 (r = 0.48, p < 0.01) and C09-2 (r = 0.41, p < 0.01), provides further evidence that PCP has been a persistent process driving Cloşani Cave Mg/Ca ratios (see Supplementary Fig. S3). Additional precipitation-sensitive trace element data such as P/Ca or Y/Ca provide further support for the interpretation of Mg/Ca ratios in terms of wet vs. dry conditions (more details in supplementary text S1).

Selective precipitation/dissolution processes such as PCP and ICD are often non-linearly related to infiltration and can be modelled by a Rayleigh process33,35. As a result, the remaining Ca concentration of the drip solution, fCa, is a measure of the degree of PCP and ICD and can thus be regarded as first order linearly related to the water availability in the karst34. Here we use the speleothem Mg/Ca ratios to calculate fCa via a Rayleigh fractionation model using a similar approach as Stoll et al.37 (a detailed description of the Rayleigh model is given in Supplementary text S2). This is an improvement of the initial transfer function proposed by Warken, et al.30, who used a linear regression model to infer precipitation amount directly from Mg/Ca ratios. The improved approach used here also assumes that the relative changes in precipitation amount (precipitation anomalies) above the cave during coeval growth phases induce the same relative changes in fCa for different stalagmites (see Supplementary text S2).

Warken, et al.30 showed that infiltration at Cloşani Cave is dominated by precipitation during autumn and winter, when evapotranspiration is negligible (Fig. 1A). As a consequence, the anti-correlation with speleothem C09-2 Mg/Ca ratios is highest (r = −0.61, p < 0.05, 1919–1973 CE) when autumn/winter precipitation amount is detrended and smoothed with a 5-yr linearly-weighted running mean, which accounts for mixing of the infiltrating water in the karst aquifer (details in ref. 30). Taking into account the age-model uncertainties in the calibration period (see section ‘Materials and methods’), the mean value of r = −0.47 ± 0.11 is still significant to an autocorrelation-adjusted p-value of <0.1 (Fig. 3A). The STAM4 Mg/Ca ratios, which extend the period of overlap between Cloşani Cave speleothems and the meteorological data until 2010 CE (Fig. 3B), also show a link to the linearly filtered autumn/winter precipitation time series, with an age-model and autocorrelation-adjusted mean value of r = −0.30 ± 0.11 (p < 0.1, 1919–2010 CE). The Mg/Ca ratios from both stalagmites were then used to calculate fCa as a measure of precipitation amount. The resulting fCa anomalies from both stalagmites agree very well, which validates the assumption that relative changes in fCa are coherent within coeval stalagmites from Cloşani Cave (Fig. 3C). As a consequence, both records were combined to a composite fCa record (Supplementary text S3) for which the mean correlation to instrumental autumn/winter precipitation amount is still moderately high (r = 0.45 ± 0.12, p < 0.1, 1919–2010 CE, Fig. 3D).

A Oct–Mar precipitation anomalies from meteorological stations TJ and DTS compared to speleothem C09-2 Mg/Ca ratios (axis inverted); B same as in A but compared to speleothem STAM4 Mg/Ca ratios (axis inverted), C Initial Ca concentration (fCa) reconstructed from speleothem C09-2 and STAM4 Mg/Ca ratios, respectively, compared to the composite fCa record. D Oct–Mar precipitation anomalies from TJ/DTS compared to the composite fCa record. All correlation coefficients are significant to a p-value of <0.01 (adjusted for autocorrelation). More details in supplementary text S2.

Considering the typically high spatial heterogeneity of precipitation data, we regard this correlation as sufficiently high to support the interpretation of relative changes in Cloşani Cave speleothem fCa as a measure for precipitation anomalies (Supplementary text S3). However, long-term changes in vegetation or seasonality could influence the infiltration season. Simulations of LGM climate20,38 support our assumption that the major part of infiltration occurs during autumn/winter. Overall, the analysis justifies the use of fCa as a proxy of past autumn/winter precipitation amount during the past about 20 ka. As a consequence, the composite Mg/Ca ratios of stalagmites C09-1 and C09-2 are used to calculate a scaled composite fCa record (see Supplementary Fig. S4) as a predictor of autumn/winter precipitation (details about the construction are given in Supplementary text S3). Changes of ±1 standard deviation (sd) in fCa correspond to ±15–20% change in autumn/winter precipitation amount during the instrumental period (Fig. 3D). However, note that due to remaining uncertainties, we focus on the interpretation of the most prominent and robust variability patterns of this semi-quantitative autumn/winter precipitation reconstruction.

δ18O values as tracer of regional hydroclimate and atmospheric circulation

At Cloşani Cave, the δ18O values of speleothem calcite reflect the δ18O values of the drip water, while temperature and disequilibrium effects inside the cave are of minor importance30. The absence of a seasonal isotope pattern in the drip water suggests a mixing of the reservoir over several months to a year or more. Hence, the drip water δ18O values reflect the annual infiltration-weighted mean of δ18O values in precipitation30. This is in line with the common, pan-regional observation of the dominant influence of cold season precipitation δ18O values on cave drip waters in ECE and the mid-latitudes5,6,20,23. Building on previous work, we therefore argue that changes in stalagmite δ18O values in the study area reflect mainly the relative contribution of water vapour between the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean during the autumn/winter season (e.g., refs. 4,23,28).

The δ18O signature of the surface waters of the North Atlantic is more negative than in the Mediterranean39, and the rain-out process during the long transit of moisture from the North Atlantic leads to further δ18O reduction. During periods of a strong NAJw, the NAJw extends north-eastward and the relative contribution of moisture from the North Atlantic increases (Fig. 1C), resulting in lower precipitation δ18O values, and vice versa4. Previous work showed that the δ18O-NAJw strength link dominated over the effects of temperature and rainfall amount at least over the last 2500 years4,6,23.

A regional comparison reveals that the evolution of speleothem δ18O values from ECE is very coherent (Fig. 4). The Cloşani Cave δ18O values (Fig. 4B) are very similar to other δ18O cave records, such as the stable oxygen isotope record of Scărișoara Ice Cave from the Apuseni Mountains (NW Romania) covering the last 10.5 ka5 (Fig. 4C). In addition, speleothem δ18O records from sites in the southern Carpathians close to Cloşani, such as Ascunsă28, Poleva Cave26, or Tăușoare Cave in the Eastern Carpathians27 agree with the long-term trend of the Cloşani Cave composite δ18O record (Fig. 4D, E). This long-term regional consistency supports the use of speleothem δ18O values as proxy of the strength of the NAJw5,23,28. However, temperature effects cannot be excluded to partly contribute to the temporal evolution of the stable oxygen isotope records, since temperature-dependent oxygen isotope fractionation effects from the source of the precipitation to the cave carbonate have a modulating influence on ECE δ18O values20,23,28. This is both due to sea-surface temperatures (SST) changes at the moisture source as well as Rayleigh distillation along the moisture trajectory. As a result, cooler temperatures lead to lower δ18O values in precipitation (and speleothem calcite) in ECE23. The Cloşani Cave precipitation reconstruction in combination with the coherent δ18O signal thus allows to explore the link between regional precipitation amount and large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns as well as northern hemispheric climate back to 20 ka BP.

From top to bottom: A Composite Cloşani Cave fCa derived precipitation anomalies (relative to the average of the period 1873 CE to modern, more details in supplementary text). The dark yellow line shows a 100 yr running mean. B Cloşani Cave composite δ18O record (blue), and September to December insolation at 40°N. C Cave ice δ18O record of Scărișoara Ice Cave5. D Speleothem δ18O records from Poleva Cave26 and Tăușoare Cave27. E Speleothem δ18O record from Ascunsă Cave28.

Discussion

ECE precipitation and NA climate during the past 20 ka

The low δ18O values of the Cloşani Cave record between c. 20 and 16 ka BP, i.e. the late LGM and the beginning of the deglaciation (Fig. 5B), reflect relatively cool SST in the evaporation regions of the North Atlantic, and potentially also a stronger moisture loss along the trajectories of the air masses than during the Holocene. From 20–18 ka BP, the precipitation reconstruction suggests that the LGM climate was on average about 20–30% wetter than today (Fig. 5A). Previously, the lack of speleothem growth in other Romanian caves has been suggested to reflect strong regional drying during the LGM26. Our result is however consistent with other regional proxy reconstructions18,19,22 as well as model simulations of European LGM hydroclimate21,38,40 suggesting that a strong and southward displaced NAJw during the LGM was associated with enhanced cyclogenesis and wetter conditions in particular in the greater Mediterranean and Alpine region. We thus attribute the more humid conditions under a colder climate to a southward displacement of the NAJw (see also below).

The figure shows A Composite Cloşani Cave fCa derived precipitation anomalies relative to the period 1873–2010 CE. The dark yellow line shows a 100 yr running mean. B Cloşani Cave composite δ18O record (blue), and September to December insolation at 40°N. Both records are compared to European climate records from top to bottom: C Bunker Cave composite δ18O record W Germany47, D stalagmite SA-1 δ18O data from southern Italy18. Note that y-axis is inverted as compared to Central European speleothem records since data is interpreted as Mediterranean rainfall proxy; E alpine speleothem δ18O records from 7H Cave19, the extended NALPS record89, as well as the COMNISPA II stack90; F SST reconstructions from the Iberian margin41,42; as well as G NGRIP ice core δ18O data on the GICC05 timescale91.

Towards the end of the Pleistocene, the Cloşani Cave δ18O record attests a response to prominent Northern Hemispheric millennial-scale climate oscillations largely synchronous with North Atlantic SSTs41,42. This demonstrates a strong influence of temperature and changes of the moisture source on speleothem δ18O values on the millennial timescales over this period. For example, during Heinrich Stadial 1 (HS1, 16.3–14.7 ka BP), speleothem δ18O values reach the lowest values of the record between 16.8 and 15.6 ka BP (about −10.4‰). This phase was accompanied by a drying trend until 15.5 ka BP, when our data suggest a minimum with about 50% less precipitation (Fig. 5A, B). A widespread drying in the Northern Hemisphere during HS1 has been interpreted as the expression of freshwater forcing and increased sea ice extent in the North Atlantic reducing SSTs and evaporation as well as the strength of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)43,44. During the subsequent Bølling/Allerød (B/A) warm period (14.7–12.9 ka BP) and the following Younger Dryas (YD) cold period (c. 12.9–11.8 ka BP), the mean autumn/winter precipitation was only slightly lower than today, averaging −10%, but showed twice as large, centennial-scale variability of ±30–60%. The evolution of δ18O values is relatively smooth, increasing to peak values at 13 ka BP and subsequently declining again (Fig. 5B). The increase of Cloşani Cave δ18O values into the B/A warming occurred from 13.9 to 13.7 ka BP, which is later than recorded in Greenland Ice cores (NGRIP) or in alpine speleothems (NALPS), but roughly synchronous with an increase of Central Mediterranean rainfall indicated by the record from Sant’ Angelo Cave18. The initiation of the YD cold phase starts again in phase with NGRIP and the NALPS record at 12.9 ka BP, even though full stadial conditions with values of −10.3‰ were not reached until 12.4 ka BP (Fig. 5B).

Subsequently, δ18O values remained comparably low (c. −10‰) with only a weak increasing trend until the hiatus at 10.9 ka BP. δ18O values during HS1 and the YD are thus about 0.5–1‰ lower than during the late LGM. Distinct minima by c. 1‰ in seawater δ18O values during HS1 and the YD have been observed in the North Atlantic, which correspond to cooler SSTs, peaks in ice-rafted debris and periods of reduced AMOC indicating the presence of meltwater in this region45. Through the following warm climate period of the early to mid-Holocene (9.5–4 ka) considerably wetter conditions with an average of about 30% higher precipitation in ECE compared to modern day are suggested (Fig. 5A). Sporadically, average autumn/winter precipitation increased by +50% or more (corresponding to c. 550 mm of autumn/winter precipitation), such as at c. 8.2 ka BP (+80%), 7–6 ka (+50%), 5.6 ka (+60%), or c. 3.5 ka (+50%) (Fig. 5A). Similar to the Cloşani Cave record, speleothem records from German caves but also from the Iberian Peninsula show a progressive increase in precipitation from the early Holocene until c. 8–7 ka BP46,47,48, suggesting a continent-wide trend. One of the wettest periods in ECE was the time around 8.2 ka BP, which corresponds to lower δ18O values in eastern and central Europe, and colder conditions in Greenland (Fig. 5). Likewise, enhanced winter/spring precipitation has been observed during the 8.2 ka cold event in the southern Carpathians49. The most recent two precipitation maxima are also reflected in the flood frequency recorded in lake Ammersee50. In addition, the minimum of flood frequency at lake Ammersee coincides with the minimum in precipitation some 2.2 ka ago (Fig. S5A). Finally, the precipitation history suggests that after c. 3.5 ka, autumn/winter precipitation was comparable to present day in terms of variability (Fig. 5A), even though the period between c. 3 and 1.5 ka BP was on average slightly drier by c. −20%. Overall, while the ECE hydroclimatic history generally follows the major long-term and millennial climate transitions of the Northern Hemisphere of the last 20 ka, the regional precipitation variability appears to strongly differ from these changes in background climate conditions, i.e. temperature and moisture sources. Thus, we infer a major role of the atmospheric moisture transport associated to the NAJw as a dominant driving force of changes in mean precipitation and its first-order variance.

Precipitation vs. steering of the NAJw over the past 20 ka

During the late LGM and the following deglaciation, the Laurentide and Fennoscandian ice sheets had a major effect on the atmospheric circulation in the Northern Hemisphere, forcing a southerly moisture trajectory of the NAJw from the NA through the Mediterranean Sea19,21,22. For example, reconstructions of paleo-glacier-derived precipitation anomalies suggest a southerly and more zonally directed NAJw also during the YD17. Especially over the central and eastern Mediterranean, more southerly and zonal storm tracks have been associated with enhanced cyclogenesis and positive precipitation anomalies17,18,21,38. For example, enhanced winter/spring precipitation from Mediterranean sources has been also suggested to explain wetter conditions in the Southern Carpathians during the 8.2 ka cold event28,49. Hence, our data advocate, that this atmospheric pattern also caused the enhanced precipitation in ECE during the LGM.

During the subsequent deglaciation, the comparably smooth transitions, lagging onsets, and muted amplitudes of HS1, the B/A, and the YD in the Cloşani Cave δ18O record attest to superimposing effects of changes at the moisture sources, NAJw strength, as well as temperature. For example, the intermittent intrusion of Mediterranean moisture in ECE with higher δ18O values could have at least partially outcompeted the effect of temperature changes in the region26. While the speleothem δ18O values are likely the result of different processes over the late last Glacial and the deglaciation, the observed changes in precipitation amount show a significantly different pattern largely unrelated to the millennial-scale variations in the Cloşani Cave δ18O values. This indicates a decoupling of regional precipitation and changes at the location of the dominant moisture source in the NA. This feature is most pronounced during the deglaciation between c. 15 ka to 11 ka BP, a time periods which also stands out in an analysis of transient model simulations as a time of high variance of precipitation and surface temperature, especially on decadal and longer timescales51.

During the early to mid-Holocene, Cloşani Cave δ18O values indicate that the transitional phase in ECE hydroclimate and atmospheric circulation patterns continues. The progressively increasing Cloşani Cave δ18O values generally reflect the warming of the Northern hemisphere following autumn/winter insolation and the demise of the Northern Hemispheric ice sheets (Fig. 4). Until c. 5-4 ka BP, the ECE stable isotope values are still relatively low as compared to the late Holocene, and indicate a relatively cool moisture source, weaker NA pressure systems, and, consequently, a weaker NAJw5. This is the result of atmospheric and oceanic reorganizations in response to a progressive reduction in meltwater fluxes to the Nordic Seas and Mediterranean. This picture is overall consistent with excess moisture transport over a southerly trajectory of the NAJw, higher precipitation amounts inECE, and provides quantitative support for proxy-based hydroclimate reconstructions for the early to mid-Holocene e.g., refs. 5,24,29. In fact,our record implies an increase in precipitation of up to 80%. This alsoreveals an inverse response of ECE precipitation to a weaker latitudinal temperature gradient (warming of the Arctic with respect to the Equator) as compared to the global mean for mid-latitudes, where a substantial decrease in net precipitation is observed11. In general, PMIP4 simulations have revealed substantial difficulties to capture precipitation changes over Europe, in particular during the mid-Holocene, where models show a large inter-model spread as well as general precipitation patterns over Europe thatare inconsistent with proxy evidence. Imperfect simulation of the extratropical atmospheric circulation is suggested as the underlying cause ofthis mismatch24,52,53.

Hydroclimate change and potential relationships to EAS teleconnection patterns

During modern times, the variability in latitude and speed of the NAJw in the EAS has been described by a combination of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and the East-Atlantic pattern (EA)3. The NAO, a leading mode of atmospheric variability in the EAS, is characterized by a meridional SLP dipole in the North Atlantic between the Icelandic Low and the Azores High. Positive phases of the NAO are associated with a hydroclimatic dipole characterized by warm and wet conditions in central and northern Europe as well as precipitation deficits in southern Europe, and vice versa54. The location of the main centre of action of the EA pattern is along the nodal line of the NAO and a strong EA often implies a southward shift of the NAO pattern with the corresponding North Atlantic storm tracks and jet stream also steered towards lower latitudes1,3,55.

Previous work interpreted the observed hydroclimate pattern during the early to mid-Holocene to reflect a predominant negative NAO condition, i.e., a weaker NAJw5,29. Wassenburg, et al.16 interpreted a shift from correlation to anti-correlation of speleothem δ18O values from Bunker Cave (Germany) vs. Grotte de Piste (Morocco) such that the configuration of the North Atlantic SLP systems and associated NAJw trajectory resembled the modern NAO pattern after 8 ka BP16. Our new precipitation record argues for a more complex temporal evolution. Wavelet coherence analysis shows that δ18O records of Cloşani and Bunker Cave in western Germany47 were coherent and in-phase on centennial to millennial timescales, suggesting that the NAJw influenced both locations coherently at least until 6–5 ka BP (Fig. S6). This observation is inconsistent with the typically observed hydroclimate patterns associated with the modern NAO, where precipitation patterns in northwestern Europe and ECE would be anticorrelated. Our analysis thus suggests that the modern position and strength of the NA pressure systems, and consequently, the strength and direction of the NAJw were not reached until 6–5 ka BP. We thus argue that the modern NAO configuration is not an appropriate analogue for the structure of the NAJw in the EAS until the mid-Holocene.

Dynamic response of ECE precipitation variability to NA reorganization

The Cloşani Cave multi-proxy record reveals distinct phases with apparently different hydroclimatic conditions over the past 20 ka. Most prominent is the phase between 18 and 10.9 ka BP, when regional precipitation amount shows pronounced centennial-scale variability decoupled from the prominent Northern Hemispheric millennial-scale climate variations during the deglaciation (Fig. 5). A similar pattern has been recognized during the late Holocene since c. 3.5–4 ka BP, when precipitation amount also appears to be intermittently decoupled from NA centers of action30. In contrast, during the late Glacial and the early to mid-Holocene, the higher coherence between δ18O values and autumn/winter precipitation amount argues for a closer link between regional precipitation amount and changes at the source of the precipitation as well as the strength of the NAJw. One exception may be the time around the cool 8.2 ka event, when reconstructed autumn/winter precipitation anomalies were particularly high. Overall, our record however, clearly advocates against a persistent thermodynamic component of both changes in the mean ECE precipitation amount, but also in terms of its variability.

We assess the observed differences in precipitation variability by calculating the standard deviation sdi of a moving 100 year-long time window. To make this measure comparable, we express sdi relative to the standard deviation of the reference period (1873–2010 CE), sdcal. Figure 6A shows the distribution of the ratio sdi/sdcal for the different periods of interest. This shows, that the mean precipitation variability during the deglaciation and the late Holocene is on average about ±1 sdcal, i.e., similar to the instrumental period, but also about twice as much as compared to the late Glacial (Fig. 6A). The distribution of the latter period is also comparably narrow, and also the range of the extreme values beyond the 95% percentile is relatively small, corresponding to maximal a maximum of 1.5 sdi/ sdcal. In contrast, the sdi/sdcal distributions for the late Holocene and deglaciation are comparably wide, suggesting that precipitation varied about twice as much as in the instrumental period (Fig. 6A). The extreme values beyond the 95% percentile even suggest a range of >2 sdi/sdcal. Hence, the precipitation amount during the late Holocene and the deglaciation was not only more variable than during the late Glacial, but also the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation events was higher during these periods. The reconstruction of the early to mid-Holocene shows a more heterogeneous pattern. When the same period was analysed without the time between c. 8.4–7.9 ka BP, the distribution resembled the late glacial, with comparably reduced variability. Conversely, the high variability anomalies of about ±2 sdi/sdcal are clearly attributable to the 8.2 ka event.

A Violin plots show the distribution of the ratio sdi/sdcal between the standard deviation sdi of a moving 100-year-long window of fCa precipitation record vs. the standard deviation sdcal of the reference period (1873–2010 CE). The distributions are shown for four distinct periods of nearly equal duration, i.e. the late Holocene (last 4 ka), the early to mid-Holocene (9.5–6 ka BP), the deglaciation (15–11 ka BP), as well as the late glacial (20–16 ka BP). The open violin plot for the early to mid-Holocene is the distribution without the section 8.4–7.9 ka BP, i.e. without the 8.2 ka event. B Continuous wavelet transform spectrum analyses of the composite Cloşani Cave fCa derived precipitation reconstruction down-sampled to 25 yrs equidistant time series. Red (blue) colours correspond to high (low) values of the transform coefficients (power). Contour lines indicate the 90% significance levels calculated using an AR(1) spectrum with autocorrelation coefficients ρ = 0.97 as derived with REDFIT. The white shading indicates the cone of influence where edge effects are not negligible. Note that the period between c. 11 and 9.5 ka BP is a hiatus in the proxy record.

Wavelet coherence analyses of the Cloşani Cave fCa record show a similar picture suggesting that the dominant frequencies in the precipitation reconstruction changed over the duration of the record. While the higher frequencies, i.e. decadal to multidecadal periods, are abundant throughout the record, centennial-scale variations are most dominant during the deglaciation as well as the late Holocene (Fig. 6B). This significant change in variability is observed in both stalagmites, and is independent of growth rate, which excludes resolution issues or aliasing effects.

Hence, this pattern can be interpreted as characteristic of the regional hydroclimate. On the one hand, the early to mid-Holocene and the late Glacial are characterized by a relatively stable regime, with attenuated hydroclimate variability in particular on centennial timescales, while the late Holocene, the 8.2 ka event, and the deglaciation can be described as relatively unstable. Since all these phases are characterized either by different background climate states or transitional phases in between, this apparent (in)stability reveals a (non-) stationary, i.e., a dynamic response of ECE precipitation to changes in the northern hemispheric background climate and associated atmospheric circulation patterns.

Potential drivers of precipitation variability in ECE

We claim that the observed multidecadal-to-centennial precipitation variability in ECE is the expression of intrinsic North Atlantic SLP and SST variability modes such as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) or the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO). Model studies and proxy reconstructions, mainly from the Holocene, have shown that multidecadal- to centennial variability is an intrinsic characteristic of the North Atlantic SLP and SST patterns, the strength of the NAJw and EAS climate e.g., refs. 4,14,54,56,57. Current hypotheses regarding the potential drivers of this variability involve external radiative forcing linked to solar variability as well as internal oscillations of the climate system tied to the AMOC54,57,58,59. While the detection of these modes in ECE precipitation variability is thus not surprising, it does not explain the observed changes in the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation events, in particular during the deglaciation and the late Holocene.

We here propose that this could be a consequence of variable blocking activity in the East Atlantic or Scandinavian/Siberian sectors. Atmospheric blocking configurations similar to the modern East Atlantic (EA) or the Scandinavian (SCAND) patterns intermittently interrupt west-to-east atmospheric flow in the EAS, which affects European precipitation patterns3,15,60,61. This includes frequently occurring dry conditions due to polar air outbreaks, but also the intrusion of Mediterranean cyclones, which may lead to higher precipitation amounts in the region60,62,63. In particular, atmospheric blocking has been demonstrated to influence the occurrence of climatological extremes in ECE8,9,60,62. On the other hand, recent work suggested that the probability of the occurrence of blocking events in the EAS is modulated by the NAO and the AMO64. Hence, we regard a modulation of the probability of more frequent and more intense precipitation in ECE by atmospheric blocking activity also on the multidecadal to centennial timescales a plausible explanation for our observation.

Enhanced blocking activity has been considered by paleo-reconstructions across Northern and Eastern Europe as a potential driver of the occurrence of stronger polar air outbreaks across Eastern Europe65, as well as the cause of a reinforcement of NA atmospheric circulation variability66 and heterogeneous precipitation patterns across Northern and Eastern Europe67. A flood frequency record from Svalbard over the past two millennia by Lapointe, et al.15 demonstrated the strong link of rainfall extremes to atmospheric blocking. The coherent pattern of this record with the Cloşani Cave δ18O record underscores the influence of blocking patterns on the NAJw trajectory over Central Europe (Supplementary Fig. S5B). A palaeoglacier-derived reconstruction of YD precipitation across Europe demonstrated that the atmospheric configuration in Central Europe was dominated by a blocking high pressure system over Scandinavia, which forced the NAJw south and east17. This period coincides with the phase of very high precipitation variability in ECE (Fig. 6). All in all, these comparisons support that this interpretation can be also transferred to other phases of the record.

Implications for precipitation projections

Our results have implications for predictions of future changes in large-scale modes of North Atlantic SLP and SST patterns and the associated precipitation variability. In particular the multi-decadal modes appear to be a continuous feature of precipitation variability and are thus expected to persist also in future climates. In the case of the precipitation anomalies in ECE, the dynamic component, i.e., changes in the mean atmospheric circulation, clearly dominates over changes in atmospheric moisture content. The dynamic component depends on a number of mechanisms, that cannot be simply linked to temperature38 and are thus difficult to infer from past climates such as the LGM or the early- to mid-Holocene, which differ significantly from future projections. This makes predictions of future changes in regional precipitation much more challenging, in particular because models still have difficulties in adequately representing the extratropical atmospheric circulation24,52,53,68. Despite the large inter-model range, a strengthening (weakening) of the NAJw and associated storm tracks over central (southern) Europe under future scenarios is expected, which would lead to drier autumn/winter conditions in the Mediterranean region38,69, and, according to our results, potentially also in ECE. In addition, the potential reorganization of SLP patterns in response to anthropogenic climate change includes augmented blocking activity in the North European regions15,68. Combined with the projected and comparably abrupt declines in sea ice, increases in SSTs and moisture availability, ECE may experience more frequent and more intense precipitation extremes. This already appears to be reflected in observed trends in the frequency and intensity of droughts and extratropical cyclones during the late 20th century8,70.

The Cloşani Cave record thus demonstrates that quantitative precipitation reconstruction on decadal scales is feasible using speleothems. Its regional nature reveals the dynamic contribution via modulated changes in the North Atlantic SLP and SST centers of action that seem to be most relevant for precipitation variability and the probability of extreme precipitation events. This also implies that processes related to the thermodynamics of the system (i.e., ‘wet gets wetter’, ‘dry gets drier’) oversimplify the intricate dynamics of precipitation and precipitation variability implied by our observations.

Materials and methods

Sample description

Cloşani Cave (45.1°N, 22.8°E) is located at the southern slope of the Carpathians in SW Romania at 433 m above sea level (m asl). The cave is developed in massive Upper Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous limestone mainly consisting of calcium carbonate with minor occurrence of dolomite. The cave consists of two main passages with a total length of 1458 m and a vertical range of 15 m (Fig. 2). The host rock overburden is c. 80–100 m (Crystals Passage) and c. 30 m (Laboratory Passage). The area is overlain by an up to 1.5 m thick brown acid soil mixed with lithosols and densely covered by vegetation consisting of grasses, shrubs and local tree stands. Stalagmites C09-1 and C09-2 were collected in 2009 in the deeper part of the Crystals Passage, while STAM4, a 6 cm high modern stalagmite, was collected in 2010 CE from an active drip site in the Laboratory Passage (Fig. 2). C09-2 has a total length of 72 cm, whereby the upper 46 cm were studied by Warken, et al.30 in terms of dating and stable isotopes as well as trace elements. In this study we analyzed the part between 46 and 64 cm dft of stalagmite C09-2. C09-1 has a total length of 42 cm. C09-1 and C09-2 are composed of clean, translucent calcite, formed mainly by proper columnar fabric. Only a small section of C09-1 between c. 3.5 and 5 cm distance from top (dft) is characterized by dendritic fabric. STAM4 has seasonal layers consisting of compact, partly translucent winter layers and milky-white porous summer layers.

230Th/U-dating

230Th/U-dating was performed using a Neptune Plus multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICPMS) (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany) at the Institute of Environmental Physics, Heidelberg University, Germany. Speleothem samples were cut with a band-saw close to the growth axis. The methods of sample preparation, mass spectrometric protocols and corrections are described in refs. 30,71, as well as references therein. Ages were calculated using the half-lives of Cheng, et al.72. Correction for detrital contamination assumes a 232Th/238U weight ratio of 3.8 ± 1.9 and 230Th, 234U and 238U in secular equilibrium. Age uncertainties are quoted at the 2σ-level and do not include half-life uncertainties.

Carbonate stable isotopes

Stable carbon and oxygen isotope preparation and analysis were performed at Institute of Geology, Innsbruck University, Austria. The samples were micro-milled at a spatial resolution of 300 µm for stalagmite C09-2, and 1 mm for C09-1 with a MicroMill (New Wave Research, Portland, USA). The carbonate powder was prepared and measured using an on-line, automated carbonate preparation system (Gasbench II) linked to a triple collector gas source ThermoFisher DeltaplusXL mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Raw data were calibrated against NBS19, and δ-values are reported relative to Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) standard. Long-term precision of the δ13C and δ18O values, estimated as the 1σ-standard deviation of replicate analyses, is 0.06 and 0.08‰, respectively73,74.

Trace element analyses

Trace element-to-Calcium ratios of the entire stalagmite C09-1 and the lower part of C09-2 between 46 and 64 cm dft were determined with an Element2 ICPMS (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a high-energy Nd:YAG UP213 laser ablation system (wavelength = 213 nm; New Wave, Fremont, USA) at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, Mainz. The line scans were performed along the growth axis of the stalagmites with a laser beam spot size of 110 µm for C09-1 and 100 µm for C09-2. The laser repetition rate was 10 Hz and the scan speed was 10 µm/s for both stalagmites. The measured isotopes were 25Mg, 27Al, 31P, 88Sr, 89Y, 137Ba (C09-2), 138Ba (C09-1), 232Th, 238U, which were normalized to 43Ca as an internal standard. The reference material used for calibration was the NIST SRM 612 a synthetic glass with a high trace element content75. For quality control the USGS MACS-3, a pressed carbonate powder, was measured76. The reproducibility based on the analyses of the homogeneous NIST SRM 612 was 5.2% for Mg, 4.8% for Al, 5.5% for P, 3.0% for Sr, 6.9% for Y, 4.3% for Ba, 6.3% for Th, and 4.8% for U (1 RSD).

The element concentrations of stalagmite STAM4 were determined with an Agilent 7500ce quadrupole ICPMS (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) equipped with a NWR193 ArF excimer laser ablation system with a wavelength of 193 nm (ESI, Omaha, USA) and a TV2 sample cell at the Institute for Geosciences, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. The laser beam spot size was 110 µm and the measurement was performed in line scan mode along the growth axis. The scan speed was 10 µm/sec and the laser repetition rate was 10 Hz. The measured isotope used for this study is 25Mg which was normalised to 43Ca, the internal standard. Also, here the NIST SRM 612 was used for calibration as well as the USGS MACS-3 was measured for quality control. The reproducibility of Mg based on the analyses of the homogeneous NIST SRM 612 is 0.9% (1 RSD). All samples were pre-ablated to prevent contamination of the analyses. For details of the method, see refs. 76,77. All data are given as molar ratios.

Monitoring and drip water analyses

For detailed description of the methods applied in the monitoring of Cloşani Cave we refer to the supplement of Warken, et al.30. In this study, we present additional data that has been obtained from six drip sites from the Crystals (CC1 to 3) and Laboratory Passages (CL1 to 3) at 2–3 monthly intervals. The concentrations of drip water cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, Sr2+) were measured at the Institute of Earth Sciences, Heidelberg University, Germany, using an Agilent ICP-OES 720 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). The internal 1σ-standard deviation for the analyses is <1% for Ca2+, Mg2+ and Sr2+. SPS SW2 is used as a standard, and the long-term 1σ-reproducibility is 2.0% for Ca2+, 3.3% for Mg2+ and 3.4% for Sr2+.

Composite record and age-depth-model

Preliminary age-depth-models for stable isotope and trace element records of C09-1 and C09-2 were constructed using the R-package ‘Bchron’78. The composite Cloşani Cave record for the overlapping sections in the Holocene was composed using the Matlab® tool ISCAM79. For the δ13C and δ18O records, ISCAM was run with 100 AR1 simulations and 1000 MC runs for each AR1 simulation. The records were smoothed over 50 years prior to the correlation procedure.

Before constructing the composite Mg/Ca record, the respective LA-ICPMS data were down-sampled to a spatial resolution corresponding to annual mean values according to their preliminary Bchron age-depth-model to reduce potential artefacts from seasonal variability or sampling resolution. The composite Mg/Ca record was constructed using normalized Mg/Ca ratios, by scaling the mean value and standard deviation of C09-1 Mg/Ca ratios to the mean and standard deviation of the C09-2 record (detailed description in the Supplementary text S3). The resulting normalized composite Mg/Ca record is then re-scaled to µmol/mol units using the mean and standard deviation of the period 1919–1973 CE, which corresponds to the maximum overlap of stalagmite C09-2 with instrumental data of the calibration period (more details in the supplementary text S3). The comparison of the composite with the original, single records is shown in Fig. S4 (Mg/Ca ratios) and Fig. S7 (δ18O and δ13C values).

Time Series and correlation analyses

Correlation analysis was performed with a test statistic based on Pearson’s product moment correlation coefficient r (x, y) following a t-distribution with length(x) − 2 degrees of freedom and corresponding p-values were adjusted for autocorrelation following Zwiers and von Storch80. Reported correlation coefficients are all significant at the 0.05 level, if not stated differently. Age model uncertainties were taken into account by following the Monte Carlo routine of Warken et al.30. Here a random shift of the age scales within the individual uncertainties of C09-2 (±3 years) and STAM4 (±6 years) is simulated, and the corresponding correlation coefficient rMg/Pw,i is calculated for the shifted time series Mg/Cashifted. This routine simulates 10,000 cross-correlations rMg/Pw,i and an overall mean correlation coefficient rMg/Pw and a corresponding standard deviation. The calculation of the means of the simulated correlation coefficients is based on Fisher’s Z transform.

For the calculation of the correlation coefficients between proxies, element to Ca ratios (El/Ca) were down-sampled to the lower resolution of the stable isotope records. Spectral analysis was conducted using the algorithm ‘REDFIT’81, as implemented in the open source software R package ‘dplR’82. REDFIT fits a first-order autoregressive (AR1) process directly to unevenly spaced time series. Wavelet analyses were performed using the R package ‘Biwavelet’83. R was run using RStudio and R version 4.2.1.

Complementary data

Instrumental data were obtained from the meteorological stations Târgu Jiu (TJ) and Drobeta-Turnu Severin (DTS), located about 50 km east and south-west, respectively, from Cloşani Cave. TJ provides monthly precipitation sums (P, 1919–2000 CE) and monthly mean temperature (T, 1900–1993 CE), whereas DTS covers P from 1925–2015 CE and T from 2006–2015 CE84. Additional data were obtained from the Global Historical Climatology Network monthly (GHCNm) dataset85. We chose the five closest stations to Cloşani Cave in this dataset, namely Semenic (ROM, 45.20°N, 22.00°E, 1432 m asl, 1961–1990 CE), Sibiu (ROM, 45.80°N, 24.20°E, 444 m asl, 1851-2018 CE), Timisoara (ROM, 45.80°N, 21.30°E, 88 m asl, 1873–2018 CE), Lom (BUL, 43.80°N, 23.20°E, 33 m asl, 1961–1999 CE), and Caracal (ROM, 44.10°N, 24.30°E, 112 m asl, 1961–1990 CE). The six months averaged GHCNm precipitation data are systematically correlated with the data from stations DTS and TJ, with r = 0.63 and r = 0.71, respectively. Furthermore, we used the Climatic Research Unit gridded Time Series (CRU TS v4.07) which is a widely used climate dataset on a 0.5° latitude by 0.5° longitude grid over all land domains of the world except Antarctica86. It is derived by interpolation of monthly climate anomalies from extensive networks of meteorological station observations spanning 1925–2014 CE. Lastly, we used the ERA5 reanalysis dataset (0.25° grid) developed and maintained by the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), hosted at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF)87.

Data availability

Data are available either in the supplementary materials or at the open data repository PANGAEA under the link https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.971689 (Trace element and stable isotope records of speleothems C09-1 and C09-2).

Code availability

Not applicable

References

Woollings, T., Hannachi, A. & Hoskins, B. Variability of the North Atlantic eddy-driven jet stream. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 136, 856–868 (2010).

Hoskins, B. J. & Hodges, K. I. New perspectives on the Northern Hemisphere winter storm tracks. J. Atmos. Sci. 59, 1041–1061 (2002).

Mellado-Cano, J., Barriopedro, D., García-Herrera, R., Trigo, R. M. & Hernández, A. Examining the North Atlantic oscillation, East Atlantic pattern, and jet variability since 1685. J. Clim. 32, 6285–6298 (2019).

Li, M. et al. Strength of the winter North Atlantic jet stream has deviated from its natural trend under anthropogenic warming. Geology https://doi.org/10.1130/g51329.1 (2023).

Persoiu, A. et al. Holocene winter climate variability in Central and Eastern Europe. Sci. Rep. 7, 1196 (2017).

Drăguşin, V. et al. Transfer of environmental signals from the surface to the underground at Ascunsă Cave, Romania. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 5357–5373 (2017).

Faranda, D., Messori, G., Jezequel, A., Vrac, M. & Yiou, P. Atmospheric circulation compounds anthropogenic warming and impacts of climate extremes in Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2214525120 (2023).

Caian, M., Georgescu, F., Pietrisi, M. & Catrina, O. Recent changes in storm track over the Southeast Europe: a mechanism for changes in extreme cyclone variability. Atmosphere 12, 1362 (2021).

Shaw, T. et al. Storm track processes and the opposing influences of climate change. Nat. Geosci. 9, 656–664 (2016).

Raible, C. C., Pinto, J. G., Ludwig, P. & Messmer, M. A review of past changes in extratropical cyclones in the northern hemisphere and what can be learned for the future. WIREs Clim. Change 12, e680 (2021).

Routson, C. C. et al. Mid-latitude net precipitation decreased with Arctic warming during the Holocene. Nature 568, 83–87 (2019).

Jackson, C. & Broccoli, A. Orbital forcing of Arctic climate: mechanisms of climate response and implications for continental glaciation. Clim. Dyn. 21, 539–557 (2003).

Shepherd, T. G. Atmospheric circulation as a source of uncertainty in climate change projections. Nat. Geosci. 7, 703–708 (2014).

Blackport, R. & Fyfe, J. C. Climate models fail to capture strengthening wintertime North Atlantic jet and impacts on Europe. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn3112 (2022).

Lapointe, F., Karmalkar, A. V., Bradley, R. S., Retelle, M. J. & Wang, F. Climate extremes in Svalbard over the last two millennia are linked to atmospheric blocking. Nat. Commun. 15, 4432 (2024).

Wassenburg, J. A. et al. Reorganization of the North Atlantic oscillation during early Holocene deglaciation. Nat. Geosci. 9, 602–605 (2016).

Rea, B. R. et al. Atmospheric circulation over Europe during the Younger Dryas. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba4844 (2020).

Columbu, A. et al. Central Mediterranean rainfall varied with high northern latitude temperatures during the last deglaciation. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 181 (2022).

Luetscher, M. et al. North Atlantic storm track changes during the Last Glacial Maximum recorded by Alpine speleothems. Nat. Commun. 6, 6344 (2015).

Wolf, A. et al. Western Caucasus regional hydroclimate controlled by cold-season temperature variability since the Last Glacial Maximum. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 66 (2024).

Ludwig, P., Schaffernicht, E. J., Shao, Y. & Pinto, J. G. Regional atmospheric circulation over Europe during the Last Glacial Maximum and its links to precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 2130–2145 (2016).

Spötl, C., Koltai, G., Jarosch, A. & Cheng, H. Increased autumn and winter precipitation during the Last Glacial Maximum in the European Alps. Nat. Commun. 12, 1839 (2021).

Kern, Z., Demény, A., Perşoiu, A. & Hatvani, I. G. Speleothem records from the eastern part of Europe and Turkey—discussion on stable oxygen and carbon isotopes. Quaternary 2, 31 (2019).

Mauri, A., Davis, B. A. S., Collins, P. M. & Kaplan, J. O. The influence of atmospheric circulation on the mid-Holocene climate of Europe: a data–model comparison. Clim. Past 10, 1925–1938 (2014).

Feurdean, A. et al. Climate variability and associated vegetation response throughout Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) between 60 and 8 ka. Quat. Sci. Rev. 106, 206–224 (2014).

Constantin, S., Bojar, A.-V., Lauritzen, S.-E. & Lundberg, J. Holocene and Late Pleistocene climate in the sub-Mediterranean continental environment: a speleothem record from Poleva Cave (Southern Carpathians, Romania). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 243, 322–338 (2007).

Staubwasser, M. et al. Impact of climate change on the transition of Neanderthals to modern humans in Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 9116–9121 (2018).

Drăguşin, V. et al. Constraining Holocene hydrological changes in the Carpathian–Balkan region using speleothem δ18O and pollen-based temperature reconstructions. Clim. Past 10, 1363–1380 (2014).

Demény, A. et al. Mid-Holocene climate conditions and moisture source variations based on stable H, C and O isotope compositions of speleothems in Hungary. Quat. Int. 293, 150–156 (2013).

Warken, S. F. et al. Reconstruction of late Holocene autumn/winter precipitation variability in SW Romania from a high-resolution speleothem trace element record. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 499, 122–133 (2018).

Cleary, D. M., Wynn, J. G., Ionita, M., Forray, F. L. & Onac, B. P. Evidence of long-term NAO influence on East-Central Europe winter precipitation from a guano-derived δ15N record. Sci. Rep. 7, 14095 (2017).

Weissbach, T. et al. Constraints for precise and accurate fluid inclusion stable isotope analysis using water-vapour saturated CRDS techniques. Chem. Geol. 617, 121268 (2023).

Johnson, K., Hu, C., Belshaw, N. & Henderson, G. Seasonal trace-element and stable-isotope variations in a Chinese speleothem: The potential for high-resolution paleomonsoon reconstruction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 244, 394–407 (2006).

de Wet, C. B. et al. Semiquantitative estimates of rainfall variability during the 8.2 kyr event in California using speleothem calcium isotope ratios. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL089154 (2021).

Sinclair, D. J. et al. Magnesium and strontium systematics in tropical speleothems from the Western Pacific. Chem. Geol. 294, 1–17 (2012).

Wassenburg, J. A. et al. Calcite Mg and Sr partition coefficients in cave environments: implications for interpreting prior calcite precipitation in speleothems. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 269, 581–596 (2020).

Stoll, H. M. et al. Distinguishing the vegetation and soil component of δ13C variation in speleothem records from degassing and prior calcite precipitation effects. Clim. Discuss. 2022, 1–30 (2022).

D’Agostino, R. & Lionello, P. The atmospheric moisture budget in the Mediterranean: mechanisms for seasonal changes in the Last Glacial Maximum and future warming scenario. Quat. Sci. Rev. 241, 106392 (2020).

LeGrande, A. N. et al. Consistent simulations of multiple proxy responses to an abrupt climate change event. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 837–842 (2006).

Kageyama, M. et al. The PMIP4 Last Glacial Maximum experiments: preliminary results and comparison with the PMIP3 simulations. Clim. Past 17, 1065–1089 (2021).

Darfeuil, S. et al. Sea surface temperature reconstructions over the last 70 kyr off Portugal: biomarker data and regional modeling. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 31, 40–65 (2016).

Martrat, B. et al. Four climate cycles of recurring deep and surface water destabilizations on the iberian margin. Science 317, 502–507 (2007).

Kageyama, M. et al. Climatic impacts of fresh water hosing under Last Glacial Maximum conditions: a multi-model study. Clim. Past 9, 935–953 (2013).

Allard, J. L., Hughes, P. D. & Woodward, J. C. Heinrich Stadial aridity forced Mediterranean-wide glacier retreat in the last cold stage. Nat. Geosci. 14, 197–205 (2021).

Benway, H. M., McManus, J. F., Oppo, D. W. & Cullen, J. L. Hydrographic changes in the eastern subpolar North Atlantic during the last deglaciation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 3336–3345 (2010).

Smith, A. C. et al. North Atlantic forcing of moisture delivery to Europe throughout the Holocene. Sci. Rep. 6, 24745 (2016).

Fohlmeister, J. et al. Bunker Cave stalagmites: an archive for central European Holocene climate variability. Clim. Past 8, 1751–1764 (2012).

Riechelmann, D. F., Jochum, K. P., Richter, D. K. & Scholz, D. Mg records of two stalagmites from B7-Cave (northwest Germany) indicating long-term precipitation changes during Early to Mid-Holocene. Int. J. Speleol. 52, 2 (2023).

Pál, I. et al. Small-scale moisture availability increase during the 8.2-ka climatic event inferred from biotic proxy records in the South Carpathians (SE Romania). Holocene 26, 1382–1396 (2016).

Czymzik, M. et al. Orbital and solar forcing of shifts in Mid- to Late Holocene flood intensity from varved sediments of pre-alpine Lake Ammersee (southern Germany). Quat. Sci. Rev. 61, 96–110 (2013).

Ziegler, E. et al. Patterns of changing surface climate variability from the Last Glacial Maximum to present in transient model simulations. EGUsphere 2024, 1–51 (2024).

Bartlein, P. J., Harrison, S. P. & Izumi, K. Underlying causes of Eurasian midcontinental aridity in simulations of mid-Holocene climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 9020–9028 (2017).

Brierley, C. M. et al. Large-scale features and evaluation of the PMIP4-CMIP6 midHolocene simulations. Clim 16, 1847–1872 (2020).

Hernández, A. et al. Modes of climate variability: synthesis and review of proxy-based reconstructions through the Holocene. Earth Sci. Rev. 209, 103286 (2020).

Comas-Bru, L. & Hernández, A. Reconciling North Atlantic climate modes: revised monthly indices for the East Atlantic and the Scandinavian patterns beyond the 20th century. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 2329–2344 (2018).

Sirocko, F. et al. Muted multidecadal climate variability in central Europe during cold stadial periods. Nat. Geosci. 14, 651–658 (2021).

Adolphi, F. et al. Persistent link between solar activity and Greenland climate during the Last Glacial Maximum. Nat. Geosci. 7, 662–666 (2014).

Otterå, O. H., Bentsen, M., Drange, H. & Suo, L. External forcing as a metronome for Atlantic multidecadal variability. Nat. Geosci. 3, 688–694 (2010).

Zhang, R. et al. A review of the role of the Atlantic Meridional overturning circulation in Atlantic multidecadal variability and associated climate impacts. Rev. of Geophys. 57, 316–375 (2019).

Rimbu, N., Stefan, S. & Necula, C. The variability of winter high temperature extremes in Romania and its relationship with large-scale atmospheric circulation. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 121, 121–130 (2015).

Ionita, M. The impact of the East Atlantic/Western Russia pattern on the hydroclimatology of Europe from mid-winter to late spring. Climate 2, 296–309 (2014).

Ionita, M., Nagavciuc, V., Scholz, P. & Dima, M. Long-term drought intensification over Europe driven by the weakening trend of the Atlantic Meridional overturning circulation. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 42, 101176 (2022).

Busuioc, A., Dobrinescu, A., Birsan, M. V., Dumitrescu, A. & Orzan, A. Spatial and temporal variability of climate extremes in Romania and associated large‐scale mechanisms. Int. J. Climatol. 35, 1278–1300 (2015).

Wazneh, H., Gachon, P., Laprise, R., de Vernal, A. & Tremblay, B. Atmospheric blocking events in the North Atlantic: trends and links to climate anomalies and teleconnections. Clim. Dyn. 56, 2199–2221 (2021).

Muschitiello, F., Schwark, L., Wohlfarth, B., Sturm, C. & Hammarlund, D. New evidence of Holocene atmospheric circulation dynamics based on lake sediments from southern Sweden: a link to the Siberian High. Quat. Sci. Rev. 77, 113–124 (2013).

Czymzik, M. et al. Mid-Holocene reinforcement of North Atlantic atmospheric circulation variability from a western Baltic lake sediment record. Clim. Past 19, 233–248 (2023).

Perşoiu, A., Ionita, M. & Weiss, H. Atmospheric blocking induced by the strengthened Siberian High led to drying in west Asia during the 4.2 ka BP event–a hypothesis. Clim. Past 15, 781–793 (2019).

Davini, P. & d’Andrea, F. From CMIP3 to CMIP6: Northern Hemisphere atmospheric blocking simulation in present and future climate. J. Clim. 33, 10021–10038 (2020).

Barcikowska, M. J. et al. Euro-Atlantic winter storminess and precipitation extremes under 1.5 °C vs. 2 °C warming scenarios. Earth Syst. Dyn. 9, 679–699 (2018).

Bădăluță, C., Haliuc, A., Bădăluță, G. & Scriban, R. Spatiotemporal variability of drought in Romania during 1901-2021 using the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI). Analele Univ. din Oradea Ser. Geogr. 34, 33–44 (2024).

Kerber, I. K. et al. Simultaneous U and Th isotope measurements for U-series dating using MCICPMS. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 539, 169–178 (2023).

Cheng, H. et al. Improvements in 230Th dating, 230Th and 234U half-life values, and U–Th isotopic measurements by multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 371, 82–91 (2013).

Spötl, C. Long-term performance of the Gasbench isotope ratio mass spectrometry system for the stable isotope analysis of carbonate microsamples. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 25, 1683–1685 (2011).

Spötl, C. & Vennemann, T. W. Continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometric analysis of carbonate minerals. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 17, 1004–1006 (2003).

Jochum, K. P. et al. Determination of reference values for NIST SRM 610-617 glasses following ISO guidelines. Geostand. Geoanalytical Res. 35, 397–429 (2011).

Jochum, K. P. et al. Accurate trace element analysis of speleothems and biogenic calcium carbonates by LA-ICP-MS. Chem. Geol. 318-319, 31–44 (2012).

Mischel, S. A., Mertz-Kraus, R., Jochum, K. P. & Scholz, D. TERMITE: an R script for fast reduction of laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry data and its application to trace element measurements. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 31, 1079–1087 (2017).

Haslett, J. & Parnell, A. A simple monotone process with application to radiocarbon‐dated depth chronologies. J. R. Stat. Soc. Appl. Stat. Ser. C. 57, 399–418 (2008).

Fohlmeister, J. A statistical approach to construct composite climate records of dated archives. Quat. Geochronol. 14, 48–56 (2012).

Zwiers, F. W. & von Storch, H. Taking serial-correlation into account in tests of the mean. J. Clim. 8, 336–351 (1995).

Schulz, M. & Mudelsee, M. REDFIT: estimating red-noise spectra directly from unevenly spaced paleoclimatic time series. Comput. Geosci. 28, 421–426 (2002).

Bunn, A. et al. Package ‘dplR’. (2020).

Gouhier, T. C., Grinsted, A., Simko, V., Gouhier, M. T. C. & Rcpp, L. Package ‘biwavelet’. (2019).

Klein Tank, A. M. G. et al. Daily dataset of 20th-century surface air temperature and precipitation series for the European climate assessment. Int. J. Climatol. 22, 1441–1453 (2002).

Lawrimore, J. H. et al. An overview of the Global Historical Climatology Network monthly mean temperature data set, version 3. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 116, D19121 (2011).

Harris, I., Osborn, T. J., Jones, P. & Lister, D. Version 4 of the CRU TS monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Sci. data 7, 1–18 (2020).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Trouet, V. & Van Oldenborgh, G. J. KNMI climate explorer: a web-based research tool for high-resolution paleoclimatology. Tree Ring Res. 69, 3–13,11 (2013).

Li, H., Spoetl, C. & Cheng, H. A high‐resolution speleothem proxy record of the Late Glacial in the European Alps: extending the NALPS19 record until the beginning of the Holocene. J. Quat. Sci. 36, 29–39 (2021).

Fohlmeister, J., Vollweiler, N., Spötl, C. & Mangini, A. COMNISPA II: update of a mid-European isotope climate record, 11 ka to present. Holocene 23, 749–754 (2012).

Rasmussen, S. O. et al. A stratigraphic framework for abrupt climatic changes during the Last Glacial period based on three synchronized Greenland ice-core records: refining and extending the INTIMATE event stratigraphy. Quat. Sci. Rev. 106, 14–28 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank R. Eichstädter, M. Wimmer, B. Stoll, U. Weis, P. Büscher and R. Mertz-Kraus for assistance in the laboratories and with analytical work. We acknowledge the contribution of M. Terente to carrying out the cave monitoring in the early stage of this project. Support for the Twentieth Century Reanalysis Project version 3 dataset is provided by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science Biological and Environmental Research (BER), by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Climate Program Office and by the NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory Physical Sciences Laboratory. This study benefitted from funding for the CAVEMONITOR Project (EEA Grant 17/2014, to SC) and the KARSTHIVES 2 Project (EEA Grant 126/2018, to SC) as well as the German Research Foundation (DFG Project INST35-1143-1 FUGG, to NF). SFW is thankful for support from Heidelberg University via the Olympia Morata program. For the publication fee we acknowledge financial support by Heidelberg University. Finally, the authors thank the anonymous reviewers for providing valuable feedback that helped to improve this work.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: S.F.W., D.F.C.R., J.F., N.F., A.S.R. Methodology: S.F.W, C.S., K.P.J., N.F., A.S.R. Investigation: S.F.W., D.F.C.R., J.F., A.S.R., C.S., K.P.J., I.C.M. Visualization: S.F.W. Supervision: N.F., D.S. Writing—original draft: S.F.W. Writing—review & editing: D.F.C.R., J.F., C.S., D.S., I.C.M., S.C., N.F., A.S.R.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Kyung-Sook Yun and Carolina Ortiz Guerrero. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Warken, S.F., Riechelmann, D.F.C., Fohlmeister, J. et al. Dynamic processes determine precipitation variability in Eastern Central Europe since the Last Glacial Maximum. Commun Earth Environ 5, 694 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01876-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01876-9