Abstract

Current frameworks for evaluating biogeochemical climate change feedbacks in Earth System Models lack an explicit consideration of nitrogen cycling in the land and ocean spheres despite its vital role in limiting primary productivity. As coupled carbon-nitrogen cycling becomes the norm, a better understanding of the role of nitrogen cycling is needed. Here we develop a new framework for quantifying carbon-nitrogen feedbacks in Earth System Models and show that rising nitrogen deposition acts as a negative feedback over both land and ocean, enhancing carbon dioxide (CO2) fertilisation in a model ensemble. However, increased CO2 uptake due to rising nitrogen deposition is small relative to the large reduction in CO2 uptake when coupled carbon-nitrogen cycling is implemented in Earth System Models. Altogether, rising nitrogen deposition leads to only a minor increase in CO2 uptake but also enhances nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions over land and ocean, contributing only marginally to mitigating climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biogeochemical climate change feedbacks are one of the largest sources of uncertainty in climate change projections of Earth system models (ESMs) and their analysis has become an integral component of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Assessment Reports (IPCC ARs)1. Rising atmospheric CO2 stimulates photosynthesis as well as ocean CO2 dissolution, and thus increases global CO2 uptake of the land and ocean2,3. Globally, these processes act as negative feedbacks that reduce the rate of climate change (referred to as the land and ocean carbon-concentration feedbacks). On the other hand, warming associated with rising atmospheric CO2 stimulates soil organic matter decomposition and thus decreases global CO2 uptake of the land4. Warming also decreases the solubility of CO2 in seawater and CO2 transport to the deep ocean via weakened ocean circulation and thus decreases global CO2 uptake of the ocean3. Globally, these processes act as positive feedbacks that intensify the rate of climate change (referred to as the land and ocean carbon-climate feedbacks). Previous analyses have primarily focused on interactions between the carbon (C) cycle and climate change5,6, but additional biogeochemical climate change feedbacks within the Earth system have been suggested to be important in modulating future climate change7,8. In particular, nitrogen (N) is an essential nutrient in the biosphere and has emerged as playing a vital but largely overlooked role in both limiting primary productivity5,9,10 as well as promoting gaseous emissions of nitrous oxide (N2O)11.

CO2 fertilisation of primary productivity is constrained by N limitation on land2,12, thereby constraining the magnitude of the negative feedback between atmospheric CO2 and land CO2 uptake (the land carbon-concentration feedback). In the ocean, primary productivity can also be N-limited13, although biological processes play a smaller role than physical processes in ocean CO2 uptake. Conversely, atmospheric N deposition has increased dramatically over the historical period primarily because of increasing gaseous N emissions from intensive N fertiliser use in agriculture as well as fossil fuel burning14. Rising N deposition has often been suggested as a key driver of increasing terrestrial primary productivity with the potential to alleviate N limitation of CO2 fertilisation15. While the impacts of N deposition have been examined with land surface models16,17, the potential of rising N deposition to alleviate N limitation of CO2 fertilisation considering both the complexities of the interactions between C and N cycling and biogeochemical climate change feedbacks in ESMs is currently unclear18,19.

Only half of ESMs included land N cycling in simulations performed for the sixth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) which informed IPCC AR6 (whereas almost all ESMs included ocean N cycling)5. We expect that most ESMs will include coupled land C-N cycling in the next phase—CMIP7 and IPCC AR7. The adoption of N cycling as well as the complexity of the interactions between C and N cycling highlight the need for a formal derivation and analysis of C-N feedbacks in ESMs. Here we develop a new C-N feedback framework for ESMs and quantify the impacts of rising N deposition in ESMs. We analyse three ESMs (MIROC-ES2L, MPI-ESM1.2-LR, and UKESM1-0-LL) that provided outputs for N deposition experiments alongside eight other ESMs (ACCESS-ESM1.5, BCC-CSM2-MR, CanESM5, CESM2, CNRM-ESM2-1, IPSL-CM6A-LR, NOAA-GFDL-ESM4, and NorESM2-LM) that provided outputs for general climate change experiments following the Coupled Climate Carbon Cycle Model Intercomparison Project (C4MIP) CMIP6 protocol5,20.

Results and discussion

New carbon-nitrogen feedback framework

In the traditional framework for evaluating feedbacks between the C cycle and climate change in ESMs5,6, net CO2 uptake in land and ocean (i.e., change in the land C pool (∆CL) and change in the ocean C pool (∆CO)) are attributed to contributions from the change in atmospheric CO2 concentration (∆[CO2]) and temperature (∆T) relative to their pre-industrial values:

The carbon-concentration feedback (\(\beta\); Pg C ppm−1) describes the sensitivity of the ocean and land C pools to change in atmospheric CO2. The carbon-climate feedback (\(\gamma\); Pg C K−1) describes the sensitivity of the ocean and land C pools to change in globally averaged temperature. These feedback metrics are typically calculated using idealised ESM simulations in which atmospheric CO2 concentration increases at a rate of 1% per year from its pre-industrial value (1pctCO2 experiments; Supplementary Fig. 1). 1pctCO2 experiments are conducted for fully, radiatively, and biogeochemically coupled ESM configurations, which enables the isolation of these feedbacks, as organised by C4MIP5,20.

We derive and quantify a new carbon-nitrogen feedback metric, \(\varepsilon\) (Pg C Tg N−1), that quantifies the sensitivity of the ocean and land C pools to changes in N deposition (\(\Delta {N}_{{dep}}\)):

This new feedback metric is calculated using idealised ESM simulations in which N deposition increases with the same relative growth rate as atmospheric CO2 concentration following the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 5-8.5 (SSP5-8.5) (1pctCO2Ndep experiments), which are conducted for fully, radiatively, and biogeochemically coupled ESM configurations and are also organised by C4MIP. N deposition can be used to characterise carbon-nitrogen feedbacks in ESMs, not only because of its suggested importance in alleviating N limitation of CO2 fertilisation, but also because it is implemented in ESM simulations as a forcing similarly to atmospheric CO2 concentration (Supplementary Notes 1 and Fig. 1). The framework for calculating \({\varepsilon }_{i}\) is described in the Methods. Briefly, \({\varepsilon }_{i}\) is derived as the net CO2 uptake (in land or ocean) associated with N deposition per unit change in N deposition using either fully or biogeochemically coupled ESM configurations.

Coupled land carbon-nitrogen cycling and carbon-nitrogen feedbacks are increasingly included in ESMs but are not explicitly considered in the existing frameworks for evaluating biogeochemical climate change feedbacks in ESMs. CO2 uptake occurs over land or ocean. Inorganic nitrogen (N) refers to soil inorganic N over the land and dissolved inorganic N over the ocean. Red arrows with a minus sign indicate that an increase in the input variable causes a decrease in the output variable, and green arrows with a plus sign indicate that an increase in the input variable causes an increase in the output variable. Blue boxes indicate quantities involved in feedback loops, and yellow boxes indicate forcings in ESM simulations. Note that because 1pctCO2 experiments are prescribed atmospheric CO2 concentration as a forcing, it does not respond to CO2 uptake (see Supplementary Notes 1). This figure was created using BioRender.com.

Carbon-nitrogen, carbon-climate, and carbon-concentration feedbacks

On land, CO2 fertilisation acts as a negative feedback by reducing atmospheric CO2 accumulation due to anthropogenic CO2 emissions2 (\({\beta }_{L} > 0\)). However, associated warming stimulates soil organic matter decomposition and acts as a positive feedback by enhancing atmospheric CO2 accumulation4 (\({\gamma }_{L} < 0\)). Similarly, increasing ocean CO2 dissolution acts as a negative feedback (\({\beta }_{O} > 0\)) but warming reduces the solubility of CO2 in seawater and CO2 transport to the deep ocean acting as a positive feedback3 (\({\gamma }_{O} < 0\)). N limitation constrains CO2 fertilisation on land: ESMs with coupled land C-N cycling exhibit a weaker \({\beta }_{L}\) than ESMs without coupled land C-N cycling, as described in ref. 5 and as shown in Fig. 2a. Additionally, ESMs with coupled land C-N cycling also exhibit a slightly weaker \({\gamma }_{L}\) than ESMs without coupled land C-N cycling (Fig. 2b). This could be because rising temperatures stimulate N mineralisation which could alleviate N limitation of primary productivity in ESMs with coupled land C-N cycling (Supplementary Fig. 2).

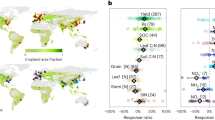

a Carbon-concentration feedback metric (\(\beta\)), describing the response of land and ocean CO2 uptake to changes in atmospheric CO2 concentration. b Carbon-climate feedback metric (\(\gamma\)), describing the response of land and ocean CO2 uptake to changes in temperature. c Carbon-nitrogen feedback metric (\(\varepsilon\)), describing the response of land and ocean CO2 uptake to changes in nitrogen (N) deposition. d Contribution of feedbacks to cumulative net CO2 uptake over 140 years of the 1pctCO2 experiment. Boxes show the mean ± 1 standard deviation, and points represent individual ESMs. Eleven Earth System Models (ESMs) were analysed for the carbon-concentration and carbon-climate feedbacks, and three ESMs were analysed for the carbon-nitrogen feedback. Values are given in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

We find that N deposition acts as a negative feedback on land (\({\varepsilon }_{L} > 0\)) in all ESMs. N deposition alleviates N limitation of primary productivity and stimulates CO2 uptake on land (Fig. 2). We similarly find that N deposition acts as a weak negative feedback in the ocean (\({\varepsilon }_{O} > 0\)) in one ESM but negligible (\({\varepsilon }_{O}\cong 0\)) in the other two ESMs. This is because less N deposition occurs over the ocean in comparison to the land surface as spatial N deposition patterns are driven by agricultural and industrial N gas emission sources on land (Supplementary Fig. 3). Additionally, primary productivity plays a smaller role than physical processes in ocean CO2 uptake. Intensifying N fertiliser input has considerably amplified riverine N input to oceans, especially coastal oceans21,22, and is another driver of ocean CO2 uptake23, but it is not considered in most ESMs24. Rising N fertiliser input was not considered in these ESM simulations but warrants further study.

The contribution of the carbon-concentration feedback to cumulative net CO2 uptake on land is 657 Pg C in ESMs with coupled land C-N cycling and 1028 Pg C in ESMs without coupled land C-N cycling (over 140 years of the 1pctCO2 experiment), which corresponds to a reduction of 371 Pg C when coupled land C-N cycling is implemented in ESMs (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 2), with the caveat that there are other inter-model differences that could contribute to this difference which is a simple approximation of N limitation. Nonetheless, this reduction is substantially greater than the contribution of the carbon-nitrogen feedback to cumulative net CO2 uptake on land, which is only 34 Pg C. Overall, this suggests that CO2 uptake driven by N deposition does not compensate for the reduction in net CO2 uptake on land due to N limitation when coupled land C-N cycling is implemented in ESMs. However, we acknowledge that these conclusions are sensitive to large uncertainties in the current parameterisations of land C-N cycling in ESMs as well as to the N deposition trajectory, which differs among SSPs.

The small influence of N deposition is likely because terrestrial biological N fixation, which is the dominant natural N source to the terrestrial biosphere, increases from a model-mean of 129 Tg N yr−1 to 184 Tg N yr−1 over 140 years of the 1pctCO2 experiment (Supplementary Fig. 4a). This 55 Tg N yr−1 increase is comparable to the increase in N deposition in the 1pctCO2Ndep experiment—from 34 Tg N yr−1 to 106 Tg N yr−1 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Higher terrestrial biological N fixation enables CO2 fertilisation to persist and reduces the stimulatory benefit of N deposition on primary productivity. ESMs exhibiting a larger increase in biological N fixation exhibit a smaller \(\varepsilon\) (Supplementary Tables 1 and 3). Additionally, terrestrial vegetation C:N ratios increase from a model-mean of 158:1 to 179:1 over 140 years of the 1pctCO2 experiment, enabling 13% more CO2 uptake per unit N (Supplementary Fig. 4b), and the persistence of CO2 fertilisation, further reducing the stimulatory benefit of N deposition on primary productivity2.

Spatial patterns in biogeochemical climate change feedbacks

N deposition exhibits high spatial variability, driving spatial patterns in the strength of the carbon-nitrogen feedback and CO2 uptake across latitudes (Fig. 3). Atmospheric CO2 concentration is specified in the 1pctCO2 experiments, and CO2 concentration increases consistently across latitudes because it is a well-mixed greenhouse gas (Fig. 3a). Land CO2 uptake driven by the carbon-concentration feedback is strongest at low latitudes (Fig. 3d). N deposition increase, however, peaks at ~50 °N and at ~10 °N (Fig. 3c). Land CO2 uptake driven by the carbon-nitrogen feedback is strongest in higher latitudes of the Northern hemisphere (Fig. 3f). This follows observations that suggest that the effect of N deposition is strongest at higher latitudes25.

a Atmospheric CO2 concentration change, (b) temperature change, (c) nitrogen (N) deposition change, (d) carbon-concentration feedback, (e) carbon-climate feedback, and (f ) carbon-nitrogen feedback over 140 years of the 1pctCO2 experiment. Eleven ESMs were analysed for the carbon-concentration and carbon-climate feedbacks, and three ESMs were analysed for the carbon-nitrogen feedback. Lines show the mean and shaded regions show the 95% confidence interval.

Compared to ESMs without coupled land C-N cycling, ESMs with coupled land C-N cycling display lower land CO2 uptake driven by the carbon-concentration feedback, as expected. However, this reduction is consistent across latitude and lacks a distinctive latitudinal pattern in N limitation that would be stronger at higher latitudes based on biogeochemical theory and observations26. Land CO2 uptake driven by the carbon-climate feedback is greatest at higher latitudes where stimulated primary productivity outweighs stimulated soil organic matter decomposition, whereas stimulated soil organic matter decomposition dominates at lower latitudes (Fig. 3e and S5). While the carbon-climate feedback is weaker for ESMs with coupled land C-N cycling (Fig. 2b), there is no clear difference in its latitudinal pattern between ESMs with and without coupled land C-N cycling (Fig. 3e). Enhanced ocean CO2 uptake driven by the carbon-concentration feedback peaks at ~40° in both hemispheres due to temperature gradients, following observations3 (Fig. 3d). Ocean CO2 uptake driven by the carbon-climate and carbon-nitrogen feedbacks does not exhibit distinctive latitudinal patterns (Fig. 3e, f).

Further climate change impacts of N cycling and implications

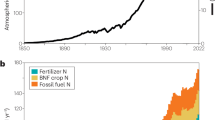

Importantly, there are several N feedbacks operating in the Earth system beyond N fertilisation of primary productivity, or “nitrogen’s carbon bonus”7,8,27. N exists as several different radiatively active gases28 – N2O is a potent greenhouse gas, NOx regulates the lifetime of greenhouse gases ozone (O3) and methane (CH4), and both NOx and NH3 contribute to secondary aerosol formation and atmospheric N deposition itself29,30. Various biogenic sources from both land and ocean contribute to these reactive N gases and are being increasingly represented in ESMs11. The cumulative radiative forcing of these N species and their feedbacks have yet to be established. In particular, the radiative forcing attributed to enhanced N2O emissions driven by rising N deposition has been suggested to offset the “carbon benefit” of simulated primary productivity from rising N deposition over both land31 and ocean32. Two ESMs studied here (MIROC-ES2L and MPI-ESM1.2-LR) reported terrestrial N2O emissions and one (MIROC-ES2L) reported ocean N2O emissions. While rising N deposition drove a 34 Pg C mean increase in cumulative net CO2 uptake on land, it also drove a 60 Tg N mean increase in cumulative net N2O emissions on land over 140 years of the 1pctCO2Ndep experiment. These N2O emissions roughly translate to the radiative equivalent of 7 Pg C (assuming a global warming potential of 273 for N2O over a 100-year timescale), which offsets a quarter of the net CO2 uptake driven by rising N deposition (Fig. 4). In the ocean, rising N deposition drove a 2 Pg C mean increase in cumulative net CO2 uptake, but also a 4 Tg N (radiative equivalent of 0.5 Pg C) mean increase in cumulative net N2O emissions over 140 years of the 1pctCO2Ndep experiment (Fig. 4). While numerous caveats underlie this simple back-of-the-envelope calculation, they highlight that gaseous N emissions driven by N deposition are of critical importance alongside its influence on primary productivity. As ESMs establish atmosphere-land and atmosphere-ocean interactions beyond CO2, these can fully be evaluated for a more complete understanding of the Earth System.

a Cumulative net CO2 uptake by land and ocean over 140 years of the 1pctCO2 and 1pctCO2Ndep experiments. b Cumulative net N2O emissions by land and ocean over 140 years of the 1pctCO2 and 1pctCO2Ndep experiments. c Cumulative net CO2 uptake (green bars) and N2O emissions (red bars) driven by rising N deposition over 140 years of the 1pctCO2Ndep experiment. Grey bars show remaining cumulative net CO2 uptake offset by cumulative net N2O emissions. Both CO2 uptake and N2O emissions are given in Pg C equivalents (assume a global warming potential of 273 for N2O over a 100-year timescale). Shaded regions and error bars show the 95% confidence interval.

The interactions between C and N cycling in the Earth system are extremely complex—their linkage exhibits wide spatial and temporal variation. As a relatively recent progression in ESMs, there are many uncertainties remaining in the implementation of coupled C and N cycling in ESMs. The representations of several key N cycling processes are implemented using differing structures and parameters across ESMs with unclear consequences24,33. Studies that have explored different representations of key N cycling processes within a single land surface model suggest that alternative representations of terrestrial biological N fixation, C:N stoichiometry, and N losses lead to substantial differences in simulated terrestrial C cycling34,35,36,37. In particular, biological N fixation, as the dominant natural N source, has an important influence but is generally represented phenomenologically rather than mechanistically as having the capacity to be upregulated in N-limited conditions and relieve N limitation of primary productivity38. N losses, especially that of N2O, are also central to determining N limitation of primary productivity in addition to their importance as radiatively active gases but exhibit considerable variability as well as discrepancies from observations39,40. Ensemble analyses show simulated terrestrial N cycling exhibits substantial variability across models in comparison to simulated terrestrial C cycling38. While simulated C and N cycling in the ocean exhibits less spread than on land, there is still substantial variability in simulated biological N fixation across models (which is often represented diagnostically rather than prognostically)41, and important processes such as riverine N input and N2O emissions are not yet represented in many ESMs24. Overall, more observational constraints on N cycling processes are critical for evaluating and improving their representation and analysis in ESMs. The results of our study are determined by the specificities of the ESMs included in the ensemble (Table 1). With the growing inclusion of coupled C and N cycling in ESMs, future research will be possible on the consequences of model differences and their impacts on biogeochemical climate change feedbacks.

Conclusions

This study quantifies the impact of C-N interactions, specifically atmospheric N deposition, on biogeochemical climate change feedbacks in idealised ESM simulations, extending the existing framework for quantifying the carbon-concentration and carbon-climate feedbacks for use in CMIP7 and IPCC AR7. It shows that the effect of N deposition is small, although not negligible, in both land and ocean, but does not contribute substantially to enhancing CO2 fertilisation on land as has been suggested. Importantly, rising N deposition does not compensate for N limitation of CO2 fertilisation, but rather promotes N2O emissions, highlighting the necessity of capturing the complexities of the interactions between C and N cycling in ESMs. As coupled land and ocean C-N cycling becomes the norm in ESMs, analysis of the role of N cycling should be standardised as a key player in feedbacks between the land, oceans, and climate change.

Methods

Feedback metric calculations

The Coupled Climate Carbon Cycle Model Intercomparison Project (C4MIP) is an endorsed Model Intercomparison Project (MIP) within the sixth Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) and seeks to quantify carbon cycle feedbacks and interactions in climate simulations20. C4MIP has endorsed a framework of tiered simulations that builds on the 1pctCO2 simulations performed as part of the CMIP DECK (Diagnostic, Evaluation, and Characterisation of Klima) simulations. In the C4MIP framework, 1pctCO2 simulations, in which atmospheric CO2 concentration increases at a rate of 1% per year from its pre-industrial value, are conducted with fully coupled, biogeochemically coupled, and radiatively coupled configurations of an ESM. In the biogeochemically coupled configuration (1pctCO2-bgc), rising atmospheric CO2 concentration affects biogeochemical processes on land and ocean, while radiative transfer processes in the atmosphere use atmospheric CO2 concentration fixed at its preindustrial value. In the radiatively coupled configuration (1pctCO2-rad), rising atmospheric CO2 concentration affects radiative transfer processes in the atmosphere and hence climate, while biogeochemical processes on land and over ocean use an atmospheric CO2 concentration fixed at its preindustrial value. In the fully coupled configuration (1pctCO2), both the biogeochemical and the radiative processes respond to rising atmospheric CO2 concentration.

In these three 1pctCO2 simulations, atmospheric N deposition is fixed at its preindustrial value. Two additional simulations are included in the C4MIP framework of tiered simulations that are designed to quantify the effect of N deposition: 1pctCO2Ndep (fully coupled) and 1pctCO2Ndep-bgc (biogeochemically coupled). These simulations used a time-varying N deposition forcing that is generated by adding the spatially-explicit difference between the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 5-8.5 (SSP5-8.5) N deposition value in 2100 and the preindustrial N deposition value to the baseline preindustrial N deposition forcing such that the relative growth rate of N deposition matches that of atmospheric CO2 concentration (i.e., the time step when atmospheric CO2 concentration reaches the SSP5-8.5 value in 2100 corresponds to the time step when N deposition reaches the SSP5-8.5 value in 2100) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

This work builds off the feedback metric calculation framework presented in ref. 5 and previous studies which analysed ESMs participating in the C4MIP contribution to CMIP6. The cumulative change in land (L) or ocean (O) carbon pools (\({\Delta C}_{X},X=L,O\); Pg C) is expressed for each configuration of an ESM. The following equations assume linearization of the globally integrated net surface-atmosphere CO2 flux in terms of either globally averaged temperature change or atmospheric CO2 concentration change. They serve to define the carbon concentration (\({\beta }_{X}\)) and the carbon climate (\({\gamma }_{X}\)) metrics for land (\(X=L\)) and ocean (\(X=O\)).

First, in a fully coupled configuration,

Second, in a biogeochemically coupled configuration,

Third, in a radiatively coupled configuration,

\({F}_{X}^{+}\), \({F}_{X}^{* }\), and \({F}_{X}^{{\prime} }\) represent the net land-atmosphere CO2 flux (\(X=L\)) or the net ocean-atmosphere CO2 flux (\(X=O\)) in Pg C yr1 for the corresponding ESM configuration. \(\Delta {T}^{+}\), \(\Delta {T}^{* }\), and \(\Delta {T}^{{\prime} }\) represent the change in globally averaged temperature in °C for the corresponding ESM configuration. \(\Delta \left[{{CO}}_{2}\right]\) represents the change in atmospheric CO2 concentration in ppm. These three equations can be used to evaluate \({\beta }_{X}\) and \({\gamma }_{X}\) using several different methods (as described in ref. 5). Here, we use the 1pctCO2 simulations for the fully and biogeochemically coupled configuration and assume \(\Delta {T}^{* }=0\) as recommended in ref. 5 Following these assumptions, we can solve Eqs. 3 and 4 for \({\beta }_{X}\) and \({\gamma }_{X}\):

Here, we add to this feedback metric calculation framework with a new carbon-nitrogen feedback metric. The following equations assume linearization of the globally integrated net surface-atmosphere CO2 flux in terms of N deposition (similarly to the treatment of globally averaged temperature change or atmospheric CO2 concentration change). In a fully coupled configuration with transient N deposition:

\(\Delta {N}_{{dep}}\) represents cumulative globally summed N deposition rate in Tg N. We assume that \(\Delta {T}^{* }=0\) and \(\Delta {T}^{{\prime} N}=\Delta {T}^{{\prime} }\) (which is reasonable, see Supplementary Fig. 5) and solve Eqs. 3, 4, and 8 for \({\varepsilon }_{X}\):

Alternatively, the carbon-nitrogen feedback metric can be calculated using the biogeochemically coupled configuration with transient N deposition, in which:

We assume again that \(\Delta {T}^{* }=0\) and \(\Delta {T}^{* N}=\Delta {T}^{* }\) and solve Eqs. 3, 4, and 10 for \({\varepsilon }_{X}\):

The carbon-nitrogen feedback metric intrinsically accounts for the synergies between increasing atmospheric CO2 concentration and increasing N deposition because the 1pctCO2Ndep experiment includes both transient atmospheric CO2 concentration and transient N deposition.

The main analysis uses the carbon-nitrogen feedback metric calculated using the fully coupled simulation with transient N deposition (Eq. 9) because it is more realistic. Both methods yield similar results (Supplementary Fig. 6) and are discussed further in Supplementary Notes 1.

Contributions of each feedback to cumulative net CO2 uptake were calculated by multiplying each feedback metric by the change in the driver (\(\Delta \left[{{CO}}_{2}\right]\), \(\Delta {T}^{{\prime} }\), and \(\Delta {N}_{{dep}}\) for \({\beta }_{X}\), \({\gamma }_{X}\), and \({\varepsilon }_{X}\), respectively). As such, the contribution of the carbon-concentration feedback is \(\Delta {C}_{X}^{* }\), the contribution of the carbon-climate feedback is \(\Delta {C}_{X}^{{\prime} }-\Delta {C}_{X}^{* }\), and the contribution of the carbon-nitrogen feedback is \(\Delta {C}_{X}^{* N}-\Delta {C}_{X}^{* }\).

Following the above method, the contribution of the carbon-nitrogen feedback to cumulative net N2O emissions was calculated as \({N}_{2}{O}^{* N}-{N}_{2}{O}^{* }\), where \({N}_{2}{O}^{* N}\) and \({N}_{2}{O}^{* }\) represent the cumulative N2O emissions in Pg N yr−1 for the corresponding ESM configuration. The CO2 equivalent of the contribution of the carbon-nitrogen feedback to cumulative net N2O emissions was calculated as \(({N}_{2}{O}^{* N}-{N}_{2}{O}^{* })\times \frac{44.01\,g\,{N}_{2}{O}\,{{mol}}^{-1}}{2\times 14.01\,{g\; N}{{mol}}^{-1}}\times \frac{273\,{g}\,{{CO}}_{2}}{{{g\; N}}_{2}O}\times \frac{12.01{g\; C}\,{{mol}}^{-1}}{44.01\,{g}\,{{CO}}_{2}\,{{mol}}^{-1}}\), where 273 is the global warming potential of N2O over a 100 year time horizon. Note that these calculations do consider stratospheric loss of N2O.

Model descriptions

Table 1 summarizes the primary features of the three ESMs that provided outputs for the 1pctCO2Ndep experiments: (1) Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology in collaboration with the University of Tokyo and the National Institute for Environmental Studies MIROC-ES2L42, (2) Max Planck Institute for Meteorology MPI-ESM1-2-LR43, and (3) UK Earth System Model UKESM1-0-LL44. An additional eight ESMs provided outputs for the 1pctCO2, 1pctCO2-bgc, and 1pctCO2-rad experiments (ACCESS-ESM1.5, BCC-CSM2-MR, CanESM5, CESM2, CNRM-ESM2-1, IPSL-CM6A-LR, NOAA-GFDL-ESM4, and NorESM2-LM). A comprehensive description of these ESMs is given in Table 1 of ref. 5.

Data availability

The ESM outputs analysed here are from the CMIP6 simulations performed by the various modelling groups and are available on the CMIP6 archive (https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/). The following variables were used from eleven ESMs described above (MIROC-ES2L, MPI-ESM1.2-LR, UKESM1-0-LL, ACCESS-ESM1.5, BCC-CSM2-MR, CanESM5, CESM2, CNRM-ESM2−1, IPSL-CM6A-LR, NOAA-GFDL-ESM4, and NorESM2-LM) and for five experiments (1pctCO2, 1pctCO2-bgc, 1pctCO2-rad, 1pctCO2Ndep, and 1pctCO2Ndep-bgc): netAtmosLandCO2Flux, nep, nbp, fgco2, tas, fNnetmin, fBNF, cVeg, nVeg, fN2O, fgn2o, areacella, sftlf, areacello, and sftof. Atmospheric CO2 concentration inputs are available at www.climatecollege.unimelb.edu.au/cmip6. Atmospheric N deposition inputs are available on the input4MIPs archive (https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/input4MIPs/). The following variables were used: drynhx, drynoy, wetnhx, and wetnoy.

Code availability

Code is available on GitHub at https://github.com/siankg/CNfeedback (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.14055962).

References

Canadell, J. G. et al. Global carbon and other biogeochemical cycles and feedbacks. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 673–816 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Walker, A. P. et al. Integrating the evidence for a terrestrial carbon sink caused by increasing atmospheric CO2. New Phytol. 229, 2413–2445 (2020).

Gruber, N. et al. The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2 from 1994 to 2007. Science 363, 1193–1199 (2019).

Davidson, E. A. & Janssens, I. A. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 440, 165–173 (2006).

Arora, V. K. et al. Carbon–concentration and carbon–climate feedbacks in CMIP6 models and their comparison to CMIP5 models. Biogeosciences 17, 4173–4222 (2020).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Climate–carbon cycle feedback analysis: results from the C4MIP model intercomparison. J. Clim. 19, 3337–3353 (2006).

Arneth, A. et al. Terrestrial biogeochemical feedbacks in the climate system. Nat. Geosci. 3, 525–532 (2010).

Heinze, C. et al. ESD reviews: climate feedbacks in the Earth system and prospects for their evaluation. Earth Syst. Dyn. 10, 379–452 (2019).

Wieder, W., Cleveland, C. C., Smith, W. K. & Todd-Brown, K. Future productivity and carbon storage limited by terrestrial nutrient availability. Nat. Geosci. 8, 441–444 (2015).

Zaehle, S., Jones, C. D., Houlton, B., Lamarque, J. F. & Robertson, E. Nitrogen availability reduces CMIP5 projections of twenty-first-century land carbon uptake. J. Clim. 28, 2494–2511 (2015).

Tian, H. et al. A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature 586, 248–256 (2020).

Terrer, C. et al. Nitrogen and phosphorus constrain the CO2 fertilization of global plant biomass. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 684–689 (2019).

Moore, C. M. et al. Processes and patterns of oceanic nutrient limitation. Nat. Geosci. 6, 701–710 (2013).

Tian, H. et al. History of anthropogenic nitrogen inputs (HaNi) to the terrestrial biosphere: a 5 arcmin resolution annual dataset from 1860 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 4551–4568 (2022).

Reay, D. S., Dentener, F. J., Smith, P., Grace, J. & Feely, R. A. Global nitrogen deposition and carbon sinks. Nat. Geosci. 1, 430–437 (2008).

O’Sullivan, M. et al. Have synergies between nitrogen deposition and atmospheric CO2 driven the recent enhancement of the terrestrial carbon sink? Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 33, 163–180 (2019).

Zaehle, S. Terrestrial nitrogen–carbon cycle interactions at the global scale. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 368, 20130125 (2013).

Zhan, C. et al. Estimating the CO2 fertilization effect on extratropical forest productivity from flux-tower observations. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 129, e2023JG007910 (2024).

Thomas, R. Q., Brookshire, E. N. J. & Gerber, S. Nitrogen limitation on land: how can it occur in Earth system models? Glob. Change Biol. 21, 1777–1793 (2015).

Jones, C. D. et al. C4MIP – the coupled climate–carbon cycle model intercomparison project: experimental protocol for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 2853–2880 (2016).

Izett, J. G. & Fennel, K. estimating the cross-shelf export of riverine materials: part 2. estimates of global freshwater and nutrient export. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 32, 176–186 (2018).

Sharples, J., Middelburg, J. J., Fennel, K. & Jickells, T. D. What proportion of riverine nutrients reaches the open ocean? Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 31, 39–58 (2017).

Yamamoto, A. et al. Competing and accelerating effects of anthropogenic nutrient inputs on climate-driven changes in ocean carbon and oxygen cycles. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl9207 (2022).

Séférian, R. et al. Tracking improvement in simulated marine biogeochemistry between CMIP5 and CMIP6. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 6, 95–119 (2020).

Schulte-Uebbing, L. F., Ros, G. H. & de Vries, W. Experimental evidence shows minor contribution of nitrogen deposition to global forest carbon sequestration. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 899–917 (2022).

Du, E. et al. Global patterns of terrestrial nitrogen and phosphorus limitation. Nat. Geosci. 13, 221–226 (2020).

Janssens, I. A. & Luyssaert, S. Carbon cycle: nitrogen’s carbon bonus. Nat. Geosci. 2, 318–319 (2009).

Thornhill, G. D. et al. Effective radiative forcing from emissions of reactive gases and aerosols – a multi-model comparison. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 853–874 (2021).

Gong, C. et al. Global net climate effects of anthropogenic reactive nitrogen. Nature 632, 557–563 (2024).

Gong, C., Kou-Giesbrecht, S. & Zaehle, S. Anthropogenic-driven perturbations on nitrogen cycles and interactions with climate changes. Curr. Opin. Green. Sustain. Chem. 46, 100897 (2024).

Zaehle, S., Ciais, P., Friend, A. D. & Prieur, V. Carbon benefits of anthropogenic reactive nitrogen offset by nitrous oxide emissions. Nat. Geosci. 4, 601–605 (2011).

Duce, R. A. et al. Impacts of atmospheric anthropogenic nitrogen on the open ocean. Science 320, 893–897 (2008).

Davies-Barnard, T. et al. Nitrogen cycling in CMIP6 land surface models: progress and limitations. Biogeosciences 17, 5129–5148 (2020).

Kou-Giesbrecht, S. & Arora, V. K. Representing the dynamic response of vegetation to nitrogen limitation via biological nitrogen fixation in the CLASSIC land model. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 36, e2022GB007341 (2022).

Meyerholt, J., Sickel, K. & Zaehle, S. Ensemble projections elucidate effects of uncertainty in terrestrial nitrogen limitation on future carbon uptake. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 3978–3996 (2020).

Peng, J. et al. Global carbon sequestration is highly sensitive to model-based formulations of nitrogen fixation. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 34, e2019GB006296 (2020).

Wieder, W., Cleveland, C., Lawrence, D. & Bonan, G. Effects of model structural uncertainty on carbon cycle projections: Biological nitrogen fixation as a case study. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 044016 (2015).

Kou-Giesbrecht, S. et al. Evaluating nitrogen cycling in terrestrial biosphere models: a disconnect between the carbon and nitrogen cycles. Earth Syst. Dyn. 14, 767–795 (2023).

Feng, M. et al. Overestimated nitrogen loss from denitrification for natural terrestrial ecosystems in CMIP6 Earth System Models. Nat. Commun. 14, 3065 (2023).

Nevison, C., Hess, P., Goodale, C., Zhu, Q. & Vira, J. Nitrification, denitrification, and competition for soil N: evaluation of two Earth System Models against observations. Ecol. Appl. 32, e2528 (2022).

Landolfi, A., Kähler, P., Koeve, W. & Oschlies, A. Global marine N2 fixation estimates: from observations to models. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2112 (2018).

Hajima, T. et al. Development of the MIROC-ES2L Earth system model and the evaluation of biogeochemical processes and feedbacks. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 2197–2244 (2020).

Mauritsen, T. et al. Developments in the MPI-M Earth System Model version 1.2 (MPI-ESM1.2) and Its Response to Increasing CO2. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 998–1038 (2019).

Sellar, A. A. et al. UKESM1: description and evaluation of the UK Earth System Model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 4513–4558 (2019).

Acknowledgements

S.K.G. was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada’s Discovery Grant Program (RGPIN-2024-04188). C.D.J., V.B., S.K.L., and S.Z. received funding from European Union’s Horizon 2020 ESM2025 - Earth System Models for the Future (101003536). C.D.J. and S.K.L. were supported by the Joint UK BEIS/Defra Met Office Hadley Centre Climate Programme (GA01101). V.B. was supported by the European Research Council Synergy Grant Q-ARCTIC (GA951288). T.H. and M.K. were supported by the MEXT-Program for the Advanced Studies of Climate Change Projection (SENTAN) (JPMXD0722681344). T.H. was supported by the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund of the Environmental Restoration and Conservation Agency provided by the Ministry of the Environment of Japan (JPMEERF24S12220).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K.G. conceptualised the study and wrote the initial draft. V.K.A. provided initial comments on the manuscript. C.D.J., V.B., T.H., M.K., S.K.L., A.J.W., and S.Z. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Clare Davis, Alice Drinkwater, and Heike Langenberg. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kou-Giesbrecht, S., Arora, V.K., Jones, C.D. et al. Rising nitrogen deposition leads to only a minor increase in CO2 uptake in Earth system models. Commun Earth Environ 6, 216 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01943-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01943-1