Abstract

Global warming has accelerated lake salinization, driving changes in microbial community structure and function. However, the dynamics of viral communities in response to salinity remain unclear. Here, we apply metagenomic sequencing to a lake on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, spanning a broad salinity gradient, to investigate viral community dynamics. Our findings reveal that salinity strongly influences viral composition and modulates viral lifestyles. Temperate viruses increase in relative abundance along the salinity gradient, whereas virulent viruses show a corresponding decline. These shifts are mirrored in the prokaryotic communities, with Alphaproteobacteria and their infecting temperate viruses, notably Casadabanvirus, becoming more prevalent in higher salinity zones. Viral genomes encode genes associated with osmotic stress adaptation, DNA recombination, and nutrient transport, which may facilitate host adaptation to saline stress. This study provides valuable insights into the interplay between viral and prokaryotic communities in response to lake salinization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lake salinization caused by anthropogenic activities and climate change has become a worsening global problem and has accelerated over the past decades1,2,3. This trend has led to notable losses of zooplankton, phytoplankton, and planktonic microorganisms, posing a severe threat to biodiversity in aquatic ecosystems4. As a fundamental environmental parameter, salinity profoundly affects aquatic biodiversity and drives microbial adaptation, speciation, and community assembly5,6. The Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau, home to diverse lakes with a wide range of salinities, provides an exceptional opportunity to investigate microbial diversity and adaptability to environmental fluctuations7,8. By applying high-throughput sequencing approaches, previous research has improved our understanding of the community structure, metabolic activities, and evolutionary processes of prokaryotes in the lakes of the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau9,10,11. However, a knowledge gap remains regarding how viruses adapt to lake salinization, presenting an intriguing mystery in this ecosystem.

Viruses, considered a critical component of microbial communities in diverse habitats worldwide, are indispensable to most ecosystems due to their exceptional diversity and abundance12. More importantly, viruses can control host abundance through density-dependent lytic processes or modulate host physiology and metabolism via lysogeny13,14, thereby markedly contributing to the biogeochemical cycling of various elements and ecological processes. Viruses are reported to release approximately 300 million tons of carbon annually by lysing microbial cells in the ocean15,16. Furthermore, viral populations are believed to constitute a substantial proportion (>5%) of the total dissolved organophosphorus in marine surface waters17. Current studies of viral diversity, community dynamics and distribution patterns predominantly center on marine and certain extreme habitats18,19,20,21. In the context of salinization induced by global climate change, studies have employed estuarine ecosystems to examine the complex impacts on viral communities22,23. However, the salinity range of most estuarine samples is limited to 0–3.5 g/L, which lacks representativeness due to the narrow range and low concentration. Consequently, how viruses adapt to salinity shifts across a broader spectrum remains largely unexplored.

Here, we collected 31 sediment samples spanning a wide range of salinity gradients in Xiaochaidan Lake and its inflowing Tataleng River on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 1a). Our goal was to mimic the salinized aquatic ecosystem and further delve into the adaptive capacity and ecological responses of viruses and microorganisms to salinization caused by global warming. Using metagenomics, we systematically investigated viral diversity, lifestyles, host interactions, and ecological determinants that shape their responses and potential adaptation to lake salinization. Our study sheds light on the dynamics of viral communities and their interactions with hosts, highlighting their adaptive strategies in response to changing salinization conditions.

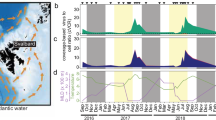

a Geolocations of 31 sediment samples collected in Xiaochaidan Lake and its inflowing Tataleng River. b Variations in salinity and TOC in sediments from Tataleng River and Xiaochaidan Lake. The red stars represent estuarine samples. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of community composition of viruses c), viral protein clustered d), prokaryotes e), prokaryotic KO clustered f). The significance of variance between these group differences was assessed using the Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance test (ADONIS2) encoded in the vegan R library. g Correlation of biotic and abiotic parameters. The color gradient in the heat map shows the Pearson correlation coefficient. The asterisk indicates the Pearson two-sided test for statistical significance using the Benjamini and Hochberg adjustment. False discovery rate control procedure. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. The width of the line corresponds to the Mantel R statistic for the corresponding distance correlations, and the line color represents statistical significance. OTUs the richness of prokaryotes, vOTUs the richness of viruses, vPCs the richness of viral protein clusters, TOC total organic carbon, KO the richness of KEGG Ortholog genes of prokaryotes.

Results

Spatial variations in physicochemical characteristics of Xiaochaidan Lake

A total of 31 sediment samples were collected from Xiaochaidan Lake and its inflowing Tataleng River on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 1a). From the Tataleng River to the eastern shore of Xiaochaidan Lake, a discernible salinity gradient was observed, escalating gradually from 0.96 to 95.11 g/L (Fig. 1b). Samples from the Tataleng River had the lowest salinity (0.96–1.14 g/L), while samples from the eastern shore had the highest (70.97–95.11 g/L) and the primary contributors to salinity were sodium and chloride ions. In contrast, the trajectory of total organic carbon (TOC) concentration exhibits a diametrically opposite pattern, with deviations observed in four samples from the estuary zone (ranging from 0.02 to 5.53 g/L). The pH values of all samples were neutral to slightly alkaline, with the lake (average 8.14) showing a slightly elevated pH compared to its river counterparts (average 7.65, Supplementary Data 1). In this lacustrine milieu, salinity and TOC fluctuations provide a unique opportunity to investigate dynamic changes in microbial and viral communities during lake salinization induced by global warming.

Environmental factors shaping the taxonomic and functional structures of prokaryotes and viruses

A total of 1817 viral contigs were identified with high confidence (length ≥10 Kbp) from 31 metagenomic datasets. A subsequent cluster analysis based on an average nucleotide identity of 95% yielded 1324 viral operational taxonomic units (vOTUs). These vOTUs serve as representatives of the species richness within viral communities across all 31 samples (Fig. S1). Notably, all viral genomes were devoid of contamination. Of these, 50 and 103 vOTUs were classified as high and medium quality with completeness ≥90% and ≥50%, respectively (Supplementary Data 2). Remarkably, 13 of these vOTUs were identified as complete viral genomes. By applying the advanced approach, only 534 vOTUs, representing 40.33% of the total, could be assigned taxonomically at the family level (Supplementary Data 3), highlighting the substantial presence of unclassified viruses in Xiaochaidan Lake. A diverse set of 79 viral families were identified, with distinct viral lineages enriched across different samples. Notably, Casadabanvirus and Kyanoviridae dominate all communities, accounting for an average relative abundance of 6.12% and 2.78%, respectively (Fig. 2a). The ribosomal protein S3 encoded by rpS3 has been employed as a biomarker for comprehensive research on microbial communities24. This yielded 5691 high-quality rpS3 gene sequences (≥300 bp in length), clustering into 4381 OTUs based on 99% amino acid identity across all samples. Contrastingly, the prokaryotic community in Xiaochaidan Lake exhibited considerable diversity, encompassing 55 bacterial phyla and 6 archaeal phyla (Supplementary Data 4). Bacteroidota, Gammaproteobacteria, and Alphaproteobacteria predominated in all samples (Fig. 2c). Intriguingly, the samples in the lake are also numerically dominated by Patescibacteria, a candidate phyla radiation (CPR) lineage known for its small cell sizes and symbiotic lifestyle, with a relative abundance reaching to 9.89%.

a Shifts in the relative abundance of viruses at the family level. b The ternary relationship of viral lineages with salinity, TOC, and pH illustrated. c Changes in the relative abundance of prokaryotes at the phylum level. d The ternary relationship of prokaryotic lineages with salinity, TOC, and pH illustrated. The circle size represents the average relative abundance of all samples.

To examine the effect of lake salinization on microbes and viruses, we employed principal coordinate analysis to evaluate clustering patterns based on the taxonomic and functional structures of prokaryotes and viruses. Results showed that the composition and function of both viral and microbial communities could be well clustered into three groups based on their locations (Fig. 1c–f and Fig. S2a–d). Further investigation identified salinity, TOC, and pH are the predominant abiotic factors significantly influencing both viral and microbial communities (Fig. S3a–d). Salinity emerged as the most important determinant of the taxonomic and functional structure of viral communities (Mantel’s r = 0.45 and 0.44, respectively, P < 0.001; Fig. 1g), while pH influences microbial communities to a greater extent (Mantel’s r = 0.50 and 0.49, respectively, P < 0.001). It is worth noting that although salinity profoundly affects the viral community structure, it has no discernible impact on viral biodiversity. In contrast, pH appears to exert a more pronounced influence on viral biodiversity, contradicting previous studies25,26. Furthermore, we unexpectedly observed strikingly higher viral richness in the lake than in the river (Fig. S4a), while the disparities in microbial richness were less pronounced (Fig. S4b). Particularly, the estuarine samples exhibit the highest viral diversity. Despite the higher salinity of the lake samples, an increase in lake salinity correlates with a reduction in viral species diversity (Fig. 3f). We conjecture that the lower diversity in the river masks the effects of salinity and TOC on viral diversity. It is noticeable that when river samples are excluded from the analysis, salinity reverts to be the primary factor affecting viral diversity (Fig. S4c), suggesting the high sensitivity of the virus to changes in salinity. Concerning microbial diversity, the significant negative correlation with salinity remained even when river samples were excluded. Altogether, salinity and TOC tend to be the pivotal determinants shaping the taxonomic and functional community dynamics of viruses. However, the prokaryotic communities were markedly influenced exclusively by salinity.

a The percentage of different lifestyle viruses. b Shifts in the relative abundance of different lifestyle viruses. c–e Correlation of the relative abundance of different lifestyle viruses and salinity, TOC and pH. f Shifts in the richness of different lifestyle viruses. g–i Correlation of the richness of different lifestyle viruses and salinity, TOC, and pH excluding river samples. The statistical test used was two-tailed.

By looking into each taxon, different viral families appear to be influenced by distinct abiotic parameters (Fig. 2b). Specifically, salinity exerted a positive influence on the abundance of several viral lineages, including Casadabanvirus, Ceeclamvirinae, Adenoviridae, and others. Conversely, pH was positively correlated with the abundance of Deejayvirinae, Smacoviridae, Mesyanzhinovviridae, and several other families (Fig. S5a). Notably, TOC demonstrated a significant negative correlation with the majority of viral lineages, except for Eucampyvirinae and Queuovirinae, which exhibited a positive correlation. Environmental factors also shaped the microbial community structure (Fig. 2d and Fig. S5b). As one of the most abundant lineages, Alphaproteobacteria showed a significant positive correlation with salinity (R = 0.70; P = 0.00014). In contrast, the other two dominant lineages, including Bacteroidetes and Gammaproteobacteria, demonstrate a remarkable correlation with pH. These findings highlight the substantial impact of diverse environmental factors on the abundance of specific viral and prokaryotic lineages.

Lake salinization modulates the dynamic changes in viral lifestyles

To understand the viral ecology during lake salinization, a comprehensive investigation of viral lifestyles was conducted. The results showed that 218 (16.47%) were identified as temperate viruses, while 356 (26.88%) were characterized as virulent viruses (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Data 5). Along with changes in salinity, the distribution of viruses varied with different lifestyles. This demonstrates that lake salinization may induce the dynamic changing of virus populations, further affecting the microbial community structure (Fig. 3b). In particular, the relative abundance of temperate viruses demonstrated a significant positive correlation with salinity and a negative correlation with TOC, while virulent viruses exhibited the exact opposite trend, correlating positively with TOC and negatively with salinity (Fig. 3c, d). No discernible relationship between pH and viral abundance was observed for either lifestyle. When examining the viral richness, the pattern was altered. Unlike the importance of salinity and TOC on the relative abundance of virulent and temperate viruses, we found that only virulent viruses had a significant positive correlation with TOC (Fig. S6a, b). This might be due to the exceptionally lower diversity of viruses in the river than in the lake (Fig. 3f). When samples from the river were excluded, we found a gradual decline in virus richness with increasing salinity. Both salinity and TOC exerted pronounced but opposite effects on the richness of virulent and temperature viruses: salinity reduced their diversity, while TOC enhanced it (Fig. 3g, h). Collectively, lake salinization generally diminishes viral diversity but fosters the spread of temperate viruses, while elevated TOC levels enhance the diversity of both lifestyle viruses and the abundance of virulent viruses.

Virus–host linkages and abundance patterns

Using multiple host prediction approaches (see Methods for details), we identified 74 (5.59%) vOTUs associated with 87 prokaryotic genomes across nine distinct phyla (Supplementary Data 6). A significant positive correlation between viral and host abundance confirmed the precision of these associations (R = 0.57, P = 0.00059; Fig. 4a). Further insights into variations in virus–host dynamics were gained by examining Virus–Host Ratios (VHRs). The VHRs ranged from 141 to 269 with an average value of 211, peaking in the phylum Krumholzibacteriota (Fig. 4b). This suggests a remarkably low virus proportion in Xiaochaidan Lake compared to other ecosystems21,27,28. Particularly, the relative abundance of many abundant microbes, such as Alphaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, Bacteroidota Verrucomicrobiota and Cyanobacteria, demonstrated clear positive correlations with viruses (Fig. 4b). Nevertheless, no discernible correlation was found between viruses and the ultrasmall microbes with tiny genome size and symbiotic lifestyle (e.g., Patescibacteria within the CPR bacteria and Woesearchaeales within the DPANN archaea), despite high VHRs in these groups.

a Pearson correlation of the abundance between viruses and their hosts. b Virus–host abundance ratios (VHRs). Blue dots indicate log10 of VHRs. Red dots represent the significance of (P < 0.05, two-tailed test) of Pearson correlations. The statistical test used was two-tailed. Black dots represent non-significant correlations. The statistical test used was two-tailed. c The relationship between viruses, their hosts, and their respective lifestyles in the Sankey plot.

By linking viruses to their corresponding hosts, we found that the major viral lineages, including Deejayvirinae, Peduoviridae, and Casadabanvirus, exhibited diverse host distributions across various phyla (Fig. 4c). In contrast, the less commonly detected viral families–Ackermannviridae, Adenoviridae, Mesyanzhinovviridae, and Dolichocephalovirinae–manifested a narrow host range, confined to a single phylum. Interestingly, we observed one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-one relationships between viruses and hosts during salinization (Supplementary Data 6). For instance, a prevalent temperate virus can infect the two genera (Roseicyclus and Roseovarius) within the Alphaproteobacteria. Among all dominant microbes, Alphaproteobacteria, Patescibacteria, and Bacteroidota could be infected by multiple viruses, while some viruses are highly specific to Desulfobacterota and Gammaproteobacteria. Although fewer temperate viruses were identified, a larger proportion of them could be linked to known hosts (Fig. 4b). Many of these temperate viruses, mainly from the family Casadabanvirus, were associated with Alphaproteobacteria. When salinity was evaluated, the relative abundance of both Alphaproteobacteria and temperate viruses infecting Alphaproteobacteria increased Fig. S7a, b). Studies have illuminated the role of temperate viruses in expanding the ecological niches of their hosts and bolstering their adaptability to environmental changes29,30. This could explain the observed increase in Alphaproteobacteria abundance that accompanies increasing salinity.

Temperate viruses facilitate host potential adaptation to elevated salinity

As salinity increased, Alphaproteobacteria and temperate viruses infecting them increased in relative abundance, demonstrating their adaptive evolution during lake salinization. By applying machine learning approaches, we attempted to establish the virus–host relationship at a finer resolution. Results showed that most of the Alphaproteobacteria-associated viruses with predictable lifestyles were identified as temperate viruses (Supplementary Data 7). Both Alphaproteobacteria and their associated viruses showed strong positive correlations with salinity, and they also demonstrated robust positive correlations with each other (Fig. 5a–c). This concordance pattern supports the “piggyback the winner” model, where temperate viruses predominate with high microbial abundance and growth rates31. With a better resolution, we found that Roseovarius was the most abundant genus within the Alphaproteobacteria (0%–16.62%; Fig. 5d). This genus tends to be primarily responsive to changes in salinity, with the average relative abundance shifting from 0% to 2.20% from lower to higher salinity. The infecting viruses also show a similar trend of change, accounting for up to 22.01% of the viral community at higher salinity. Therefore, we chose them as an exemplary model to unravel the virus–host interaction during lake salinization.

a, b Correlation of the relative abundance of Alphaproteobacterial viruses and Alphaproteobacteria and salinity. c Correlation of the relative abundance of Alphaproteobacterial viruses and Alphaproteobacteria. The statistical test used was two-tailed. d Shifts in the relative abundance of viruses infecting Roseovarius and Roseovarius in the communities. The yellow bars represent the relative abundance of Roseovarius within the Alphaproteobacteria. The yellow lines represent changes in the relative abundance of Roseovarius in the prokaryotic community. The blue lines represent changes in the relative abundance of viruses infecting Roseovarius in the prokaryotic community. e Genome maps of the identified viruses of Roseovarius. TOP6A, Type 2 DNA topoisomerase 6 subunit A; repA, RecA-family ATPase; czcD, Cadmium, cobalt, and zinc/H⁺-K⁺ antiporter; grpE, Molecular chaperone GrpE; lmbU, LmbU family transcriptional regulator; mcrA, 5-methylcytosine-specific restriction enzyme A; vapE, Virulence-associated protein E; xylG, ATP-binding protein of the d-xylose transport system; HTC, head–tail connector protein; HTA, head-tail adaptor protein; MT, major tail protein, mT, minor tail protein; TSC, tail assembly chaperone protein; TTMP, tail tape measure protein; PP, prohead protease, PPP, phage portal protein; Gifsy-1, Gifsy-1prophage protein; GH, glycoside hydrolase TIM-barrel-like domain-containing protein; C40, C40 family peptidase.

To this end, we examined the auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) of infecting viruses and the metabolic features of their hosts. Members of the predominant genus Roseovarius possess diverse metabolic capacities, including polysaccharide degradation, sulfate reduction, sulfur oxidation, and denitrification (Fig. S8a, b), which may exert a prominent impact on biogeochemical cycles in lake ecosystems. Genes encoded by infecting viruses primarily function in viral structural and assembly proteins and are rarely identified as AMGs (Fig. 5e and Fig. S9). Specifically, the RecA-family ATPase (repA) was identified in the viral genome, with studies suggesting its crucial role in facilitating homologous recombination and DNA repair32. This function may assist hosts in repairing DNA damage induced by environmental stress. The presence of cadmium, cobalt, and zinc/H⁺-K⁺ antiporter (czcD) in the viral genome implies the virus’s involvement in metal ion transport, thereby contributing to the maintenance of intracellular ion balance and homeostasis. We hypothesize that these genes might be instrumental in the regulation of osmotic pressure in the host cell, thereby enhancing the host’s adaptation to the saline environment. Furthermore, the identification of the ATP-binding protein (xylG) of d-xylose transport system in another viral genome suggests that this virus may aid the host in nutrient uptake. However, most viral genomes lack detectable AMGs, and the complexity of their interactions with the host remains enigmatic when analyzed solely on functional genes. Experimental validation is needed to understand the interactions between them.

Discussion

Similar to the Arctic regions, the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau has experienced a warming rate two to three times higher than the global average over the recent decades, accelerating the evaporation rate and exacerbating the salinization of lakes33. These changes further alter the community structure of both prokaryotes and viruses, requiring microbes inhabiting salinized lakes to evolve a greater tolerance to salt stress. By selecting a representative sampling site in an area with a well-defined salinity gradient within a single lake, our study reveals a considerable number of previously undocumented viruses in Xiaochaidan Lake, profoundly shaped by environmental conditions such as salinity and TOC. The viral community exhibited a gradual shift in lifestyle, with an increase in the relative abundance of temperate viruses along the salinity gradient, although the richness of both virulent and temperate viruses declined. The intricate interplay between virus and host lineages, together with the AMGs encoded by lysogenic viruses, underscores the crucial role of viruses in facilitating host adaptation to lake salinization.

By examining the interplay between the viruses and their hosts, we observed one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-one virus–host relationships at the species level. This phenomenon is commonly observed in previous studies, where many bacteriophages prefer a narrow range of bacterial hosts, while a few exhibit a broader host range34. The host range of viruses highly depends on the cell density, diversity, and quality of the hosts35. Studies have shown that VHRs in saline water are significantly lower than those in freshwater36. In extreme environments marked by low host biomass, certain phages broaden their host range as a survival strategy37. This is supported by research indicating that many putative lysogenic phages with a wide host range have been found in dry soils38. On the basis of this, we conjecture that certain viruses may enhance their survival by expanding their host range during lake salinization, leading to a tight connection between hosts and infecting viruses. Unlike most microbes, the ultrasmall microbes (Patescibacteria and Woesearchaeales) showed no significant correlation in abundance with their associated viruses (Fig. 4b), although some of them are abundant in the community (Fig. 2b). These microbes are characterized by their ultrasmall cell size and limited biosynthetic capacities39, resulting in a symbiotic lifestyle and obtaining necessary nutrients from their co-growing partners. In return, they can provide protection to the host from invading viruses since most of these tiny microbes harbor a larger-than-expected set of restriction systems for nonspecific defense40. This nonspecific defense may complicate the elucidation of host–virus interactions39,41 and partly explain why neither CPR nor DPANN has a significant relationship with infected viruses. Given the high abundance of Patescibacteria in the sample with high salinity (e.g., X01; Fig. S7), we further infer that this metabolically deficient lineage may rely on recycling amino acids and nucleotides released from virus-infected cells to support their growth.

In marine ecosystems, viruses employ both temperate and virulent viruses to exert differential impacts on their hosts, thereby shaping the dynamics of microbial communities and having further cascading effects on biogeochemical cycles, food webs, and the metabolic balance of the ocean42. Temperate viruses are widely recognized as more prevalent and impactful in extreme environments, implying the notion that a lysogenic lifestyle may be a more effective survival strategy under such challenging conditions43. Nevertheless, considerable controversy remains regarding viruses in saline lake habitats. Some studies indicate that salinity shifts the viral lifestyle from temperate to virulent44, while others show the exact opposite transition45,46. When salinity increased, our findings indicate that the viral richness in both lifestyles decreased (Fig. 3g and Fig. S6a). While no clear pattern of lifestyle switching was observed for individual viruses, we did note lifestyle shifts within viral communities, with an increase in relative abundances of temperate viruses at elevated salinity levels. This phenomenon is supported by a cultured phage-host system, where the increased salinity enhances the stability of the prophage47. Apart from the prominent influence of salinity, TOC also plays a determinant role in the relative abundance of both virus types, reinforcing the notion that increased nutrients cause stimulation of lytic phage production48. In nutrient-limited environments, particularly under harsh conditions characterized by high salinity, we observe a rise in the abundance of both hosts (Alphaproteobacteria) and infected viruses (Fig. 5a, b), aligning with the piggyback-the-winner model. We propose that viruses employ a cull-the-winner model to maintain the stability of microbial communities under favorable conditions and a piggyback-the-winner model to adapt to habitats subject to escalating extremes.

As the most pronounced discriminating factor, varying salt concentrations led to the proliferation of certain viral and prokaryotic lineages, which aligns with previous studies46,49. This is particularly evident under high salt conditions (22–37% in salinity), where viruses detected from different hypersaline ponds on distinct continents demonstrate consistent genetic composition and harbor genes to assist their adaptation to high salinity50. We consistently observed a notable increase in Roseovarius. Further investigation of the functional interactions suggested that their better adaptation was aided by temperate viruses infecting Roseovarius. The possession of AMGs in viral genomes of Roseovarius, albeit limited, indicates their participation in osmotic pressure regulation, DNA recombination and repair, and nutrient transport (Fig. 5e). Most of these AMGs were associated with habitat adaptation rather than involvement in biogeochemical cycles, suggesting that the evolution of these temperate viruses may have been driven by lake salinization to improve their resilience. Concordantly, numerous studies have also revealed that many AMGs enable temperate viruses to withstand changing environmental conditions. For example, lysogenic phages encoding arsenic resistance genes have been observed in arsenic-enriched soils, facilitating the adaptation of bacterial communities to arsenic toxicity51. Additionally, the genome of Shewanella oneidensis harbors prophages capable of regulating bacterial genes through phage DNA excision during cold adaptation52. Recent studies have elucidated that the Gifsy-1 prophage terminase, traditionally recognized for DNA processing, demonstrates unforeseen tRNase activity under oxidative stress conditions, thereby preserving genome integrity and ensuring host survival53. Although we conjecture that temperate viruses devoid of AMGs may engage in complex interactions with their hosts during lake salinization, experimental validation is required for accurate elucidation.

With the focus on Xiaochaidan Lake, a natural ecosystem with a salinity gradient possibly induced by global warming, we systematically investigated the profound effects of lake salinization on viral diversity, lifestyle, and host–virus interactions. Our study provides valuable insights into the ecological role of viruses in shaping microbial community dynamics in salinizing lake ecosystems. These findings enhance our understanding of viral contribution to ecosystem resilience in the context of climate change, offering valuable perspectives for predicting the ecological impacts of global environmental shifts.

Materials and methods

Sampling, physicochemical analyses, DNA extraction, and metagenomic sequencing

Xiaochaidan Lake, located in the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau (95.259–95. 359°E, 37.279–37.319°N), is a brackish lake with a natural salinity gradient, nourished by the freshwater flow of the northwestern Tataleng River. A total of 31 sediment samples were collected from the surface (0–5 cm) in November 2016. Out of these, 24 samples were obtained along the coast while the remaining seven samples were collected from the Tataleng River. All samples were carefully placed in sterile 50 mL tubes and stored in dry ice during transportation to the laboratory. Prior to DNA extraction for metagenomic sequencing, samples were pretreated to enhance DNA yield, fragment length, and overall quality. Specifically, sediment samples were pretreated with 0.1 mol L−1 ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.1 mol L−1 Tris (pH 8.0), 1.5 mol L−1 NaCl, and 0.1 mol L−1 NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4 solutions. Samples were oscillated at 180 rpm at 65 °C for 15 min and washed three times to remove humic substances and heavy metals, followed by the standard DNA extraction procedure. The measurement of physicochemical parameters and metagenomic sequencing were consistent with those described in the previous study54 and summarized in Supplementary Data 1.

Metagenomic assembly and genome binning

For all raw metagenomic reads, we applied filtration using fastp (v0.23.2)55 to remove sequence adapter and low-quality sequences with the parameters “-q 20 -u 20”. Clean reads were assembled using SPAdes (v3.15.2)56 with the parameters “-k 21, 33, 55, 77, 99,127 -meta”. Genome binning was performed on assembled scaffolds (≥2500 bp) using MetaBAT2 (v2.12.1)57, MaxBin2 (v2.2.7)58, and CONCOCT (v1.1.0)59 with default parameters, and the best bin was selected using DasTool (v1.1.3)60. The completeness and contamination of genome bins were assessed using CheckM (v1.1.3)61, and genome bins with low quality (completeness <50% or contamination ≥10%) were eliminated. The representative bins were selected using dRep (v3.2.2)62 with a threshold of 95% of the average nucleotide identity to form secondary clusters. We used the GTDB-Tk taxonomic classification tool (v2.1.1) to assign each genome bin to a GTDB-defined species (release 207)63,64.

Identification of marker genes of prokaryotes

Putative genes for assembled scaffolds were predicted using Prodigal (v2.6.3)65 with the parameter “-p meta”. The potential rpS3 gene was identified using AMPHORA266, discarding sequences shorter than 300 bp or sequences that were unable to produce the best hit in the NCBI-nr database. Protein sequences of the rpS3 gene were extracted and clustered using CD-HIT (v4.8.1)67 with the parameters “-c 0.99 -n 10 -G 0 -aS 0.9 -g 1 -d 0”. To assign taxonomy for identified rpS3 genes, we created a homemade database of rpS3 gene sequences from GTDB63. Specifically, only rpS3 gene sequences with length ≥300 bp were retained and clustered by CD-HIT (v4.8.1) with 100% identity to eliminate duplicate sequences. The taxonomy of these rpS3 genes was confirmed by conducting a search against themselves using the “assign_taxonomy.py” script in QIIME (v.1.9.1)68, employing the RDP Classifier (https://github.com/rdpstaff/classifier) and applying a minimum confidence of 0.6. Items were discarded if the taxonomy assigned at the species level did not match the taxonomy retrieved from GTDB, which arose from metagenomes due to the misassembled rpS3-containing scaffolds. All remaining nucleotide sequences were clustered using USEARCH (v.11.0.667)69 at an identity threshold of 99% to create a species-level database of rpS3 genes. After curation, the taxonomy of the rpS3 sequences identified from metagenomes in the present study was determined by searching the curated database using the “assign_taxonomy.py” script in QIIME with the same parameters mentioned above. Gene sequences that cannot be assigned at the phylum level were subjected to a BLASTx search (v2.12.0) against the protein sequences of the home-made database: “-evalue 1e-5 -num_descriptions 5 -num_alignments 5”. The lowest concordance level of the top five hits was used to assign a taxonomy to the corresponding rpS3 sequences.

Identification of viral genomes

Viral genomes were detected using VIBRANT (v1.2.1)70 and Virsorter2 (v2.2.3)71 with default parameters. To obtain the high-confidence viral genomes, all viral genome fragments identified by Virsorter2 with a “max_score <0.90” were filtered. According to the minimum information standards for uncultivated viruses, viral genomes shorter than 10 Kbp were discarded72. The completeness and contamination of viral genomes were assessed using CheckV (v0.8.1)73. Only candidates with the identification of at least one virus gene by CheckV were retained. The vOTUs were clustered using the scripts “anicalc.py” and “aniclust.py” in CheckV with the parameters “ANI <95% and alignment fraction of the smallest contigs <85%”. The lifestyle of the virus was predicted using DeePhage (v1.0)74. The taxonomy of viral genomes was assigned by PhaGCN2.075. The hosts of the viruses were predicted using VirMatcher (https://bitbucket.org/MAVERICLab/virmatcher/src/master), which utilized host CRISPR-spacers, integrated prophages, host tRNA genes, and k-mer signatures calculated by WIsH (v1.1)76,77,78,79,80 to establish connections between hosts and viruses. In this tool, a threshold of 3.0 was applied to ensure the accuracy of the prediction. To cover a broader spectrum of alphaproteobacterial viruses, we employed iPHoP (v1.3.2) to optimize host prediction81. Putative protein-coding sequences were predicted using Prodigal v2.6.3 with the “-p meta” parameter. The predicted genes were then annotated using DIAMOND (E-values < 1e−5) against KEGG, NCBI-nr, and eggNOG databases82. For unknown functional genes, we predicted protein structures using AlphaFold383 and conducted functional comparisons in the Foldseek Search Server84.

Abundance profiles

The relative abundances of vOTUs, rpS3 genes, and microbial genomes were assessed by calculating the values of Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads (RPKM). Briefly, clean reads were mapped to each dataset using the “make” command in CoverM (v0.6.1; https://github.com/wwood/CoverM). The poorly aligned reads were eliminated using the “filter” command with the parameters “–min-read-percent-identity 95 –min-read-aligned-percent 75”. The RPKM values for vOTUs and rpS3 genes were obtained using the “contig” command with the parameters “–trim-min 0.10 –trim-max 0.90 –min-read-percent-identity 0.95 –min-read-aligned-percent 0.75”, while the “genome” command in CoverM with default parameters was used to determine the RPKM values of prokaryotic genomes.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R (v4.1.3). PCoA was performed to group all samples based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarities of viral and prokaryotic community composition, as well as functional profiles. Statistical significance was assessed among the clusters generated from PCoA using adonis285. Pairwise Pearson’s correlations (https://github.com/mj163163/ggcor-1) were used to examine the relationships between prokaryotic and viral communities and other biotic and abiotic factors. The Mantel test (999 permutations) was employed to calculate the pairwise correlations between the Bray–Curtis dissimilarities of viral and prokaryotic communities, and the Euclidean distance of environmental variables.

Data availability

The raw reads of metagenomic sequencing are available in GenBank under BioProject PRJNA1131488: BioSample ID SAMN42272296 to SAMN42272326. The raw data for viral and prokaryotic richness, taxonomic and functional composition, genomic features, protein clusters, and source data used to generate figures for this study are available from https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26318227.

References

Thorslund, J. & van Vliet, M. T. H. A global dataset of surface water and groundwater salinity measurements from 1980–2019. Sci. Data 7, 231 (2020).

Birch, E. L. et al. A review of ‘climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability’ and ‘climate change 2014: mitigation of climate change’: intergovernmental panel on climate change. J. Am. Plann Assoc. 80, 184–185 (2014).

Wurtsbaugh, W. A. et al. Decline of the world’s saline lakes. Nat. Geosci. 10, 816–821 (2017).

Cunillera-Montcusi, D. et al. Freshwater salinisation: a research agenda for a saltier world. Trends Ecol. Evol. 37, 440–453 (2022).

Reid, A. J. et al. Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 94, 849–873 (2019).

Coldsnow, K. D., Relyea, R. A. & Hurley, J. M. Evolution to environmental contamination ablates the circadian clock of an aquatic sentinel species. Ecol. Evol. 7, 10339–10349 (2017).

Li, Z. X. et al. Phytoplankton community response to nutrients along lake salinity and altitude gradients on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 128, 107848 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. Salinity shapes microbial diversity and community structure in surface sediments of the Qinghai-Tibetan Lakes. Sci. Rep. 6, 25078 (2016).

Yang, J. et al. Potential utilization of terrestrially derived dissolved organic matter by aquatic microbial communities in saline lakes. ISME J. 14, 2313–2324 (2020).

Yang, J. et al. A comprehensive census of lake microbial diversity on a global scale. Sci. China Life Sci. 62, 1320–1331 (2019).

Liu, Q. et al. Influence of salinity on the diversity and composition of carbohydrate metabolism, nitrogen and sulfur cycling genes in lake surface sediments. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1019010 (2022).

Dion, M. B., Oechslin, F. & Moineau, S. Phage diversity, genomics and phylogeny. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 125–138 (2020).

Roux, S. et al. Ecogenomics and potential biogeochemical impacts of globally abundant ocean viruses. Nature 537, 689–693 (2016).

Rohwer, F. & Thurber, R. V. Viruses manipulate the marine environment. Nature 459, 207–212 (2009).

Suttle, C. A. Marine viruses-major players in the global ecosystem. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 801–812 (2007).

Breitbart, M., Bonnain, C., Malki, K. & Sawaya, N. A. Phage puppet masters of the marine microbial realm. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 754–766 (2018).

Jover, L. F., Effler, T. C., Buchan, A., Wilhelm, S. W. & Weitz, J. S. The elemental composition of virus particles: implications for marine biogeochemical cycles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 519–528 (2014).

Brum, J. R. et al. Ocean plankton. Patterns and ecological drivers of ocean viral communities. Science 348, 1261498 (2015).

Hwang, Y., Rahlff, J., Schulze-Makuch, D., Schloter, M. & Probst, A. J. Diverse viruses carrying genes for microbial extremotolerance in the atacama sesert hyperarid soil. mSystems 6, e00385–21 (2021).

Emerson, J. B. et al. Host-linked soil viral ecology along a permafrost thaw gradient. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 870–880 (2018).

Gao, S. et al. Patterns and ecological drivers of viral communities in acid mine drainage sediments across Southern China. Nat. Commun. 13, 2389 (2022).

Luo, X. Q. et al. Viral community-wide auxiliary metabolic genes differ by lifestyles, habitats, and hosts. Microbiome 10, 190 (2022).

Cai, L. et al. Ecological dynamics and impacts of viruses in Chinese and global estuaries. Water Res. 226, 119237 (2022).

Diamond, S. et al. Mediterranean grassland soil C-N compound turnover is dependent on rainfall and depth, and is mediated by genomically divergent microorganisms. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1356–1367 (2019).

Combe, M. et al. Freshwater prokaryote and virus communities can adapt to a controlled increase in salinity through changes in their structure and interactions. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 133, 58–66 (2013).

Zhang, C. et al. The communities and functional profiles of virioplankton along a salinity gradient in a subtropical estuary. Sci. Total Environ. 759, 143499 (2021).

Shi, L. D. et al. A mixed blessing of viruses in wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 215, 118237 (2022).

Li, Z. X. et al. Deep sea sediments associated with cold seeps are a subsurface reservoir of viral diversity. ISME J. 15, 2366–2378 (2021).

Rastelli, E. et al. High potential for temperate viruses to drive carbon cycling in chemoautotrophy-dominated shallow-water hydrothermal vents. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 4432–4446 (2017).

Zhu, Y., Zhang, Y., Yan, S., Chen, X. L. & Xie, S. G. Viral community structure and functional potential vary with lifestyle and altitude in soils of Mt. Everest. Environ. Int 178, 108055 (2023).

Silveira, C. B. & Rohwer, F. L. Piggyback-the-Winner in host-associated microbial communities. NPJ Biofilms Microbiol. 2, 16010 (2016).

Cox, M. M. Motoring along with the bacterial RecA protein. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio 8, 127–138 (2007).

Chen, H. et al. Carbon and nitrogen cycling on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 701–716 (2022).

De Jonge, P. A., Nobrega, F. L., Brouns, S. J. J. & Dutilh, B. E. Molecular and evolutionary determinants of bacteriophage Host Range. Trends Microbiol. 27, 51–63 (2019).

Sant, D. G., Woods, L. C., Barr, J. J. & McDonald, M. J. Host diversity slows bacteriophage adaptation by selecting generalists over specialists. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 350–359 (2021).

López-García, P. et al. Metagenome-derived virus-microbe ratios across ecosystems. ISME J. 17, 1552–1563 (2023).

Huang, D. et al. Enhanced mutualistic symbiosis between soil phages and bacteria with elevated chromium-induced environmental stress. Microbiome 9, 150 (2021).

Wu, R. N. et al. Hi-C metagenome sequencing reveals soil phage-host interactions. Nat. Commun. 14, 7666 (2023).

Castelle, C. J. et al. Biosynthetic capacity, metabolic variety and unusual biology in the CPR and DPANN radiations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 16, 629–645 (2018).

Burstein, D. et al. Major bacterial lineages are essentially devoid of CRISPR-Cas viral defence systems. Nat. Commun. 7, 10613 (2016).

He, C. et al. Genome-resolved metagenomics reveals site-specific diversity of episymbiotic CPR bacteria and DPANN archaea in groundwater ecosystems. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 354–365 (2021).

Danovaro, R. et al. Marine viruses and global climate change. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35, 993–1034 (2011).

Howard-Varona, C., Hargreaves, K. R., Abedon, S. T. & Sullivan, M. B. Lysogeny in nature: mechanisms, impact and ecology of temperate phages. ISME J. 11, 1511–1520 (2017).

Williamson, S. J. & Paul, J. H. Environmental factors that influence the transition from lysogenic to lytic existence in the phiHSIC/Listonella pelagia marine phage-host system. Microb. Ecol. 52, 217–225 (2006).

Bettarel, Y. et al. Ecological traits of planktonic viruses and prokaryotes along a full-salinity gradient. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 76, 360–372 (2011).

Zang, L. et al. Salinity as a key factor affecting viral activity and life strategies in alpine lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 69, 961–975 (2024).

Lunde, M., Aastveit, A. H., Blatny, J. M. & Nes, I. F. Effects of diverse environmental conditions on φLC3 prophage stability in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 71, 721–727 (2005).

Williamson, S. J. & Paul, J. H. Nutrient stimulation of lytic phage production in bacterial populations of the Gulf of Mexico. Aquat. Micro. Ecol. 36, 9–17 (2004).

Palermo, C. N., Shea, D. W. & Short, S. M. Analysis of different size fractions provides a more complete perspective of viral diversity in a freshwater embayment. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 87, e00197–21 (2021).

Roux, S. et al. Analysis of metagenomic data reveals common features of halophilic viral communities across continents. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 889–903 (2016).

Tang, X. et al. Lysogenic bacteriophages encoding arsenic resistance determinants promote bacterial community adaptation to arsenic toxicity. ISME J. 17, 1104–1115 (2023).

Zeng, Z. S. et al. Cold adaptation regulated by cryptic prophage excision in Shewanella oneidensis. ISME J. 10, 2787–2800 (2016).

Uppalapati, S. et al. Prophage terminase with tRNase activity sensitizes Salmonella enterica to oxidative stress. Science 384, 100–105 (2024).

Fang, Y. et al. Compositional and metabolic responses of autotrophic microbial community to salinity in lacustrine environments. mSystems 7, e0033522 (2022).

Chen, S. F. et al. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, 884–890 (2018).

Bankevich, A. et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19, 455–477 (2012).

Kang, D. D. et al. MetaBAT 2: an adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ 7, e7359 (2019).

Wu, Y. W., Simmons, B. A. & Singer, S. W. MaxBin 2.0: an automated binning algorithm to recover genomes from multiple metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 32, 605–607 (2016).

Alneberg, J. et al. Binning metagenomic contigs by coverage and composition. Nat. Methods 11, 1144–1146 (2014).

Sieber, C. M. K. et al. Recovery of genomes from metagenomes via a dereplication, aggregation and scoring strategy. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 836–843 (2018).

Chklovski, A., Parks, D. H., Woodcroft, B. J. & Tyson, G. W. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 25, 1043–1055 (2015).

Olm, M. R., Brown, C. T., Brooks, B. & Banfield, J. F. dRep: a tool for fast and accurate genomic comparisons that enables improved genome recovery from metagenomes through de-replication. ISME J. 11, 2864–2868 (2017).

Parks, D. H. et al. A complete domain-to-species taxonomy for Bacteria and Archaea. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 1079–1086 (2020).

Chaumeil, P. A., Mussig, A. J., Hugenholtz, P. & Parks, D. H. GTDB-Tk: a toolkit to classify genomes with the genome taxonomy database. Bioinformatics 36, 1925–1927 (2019).

Hyatt, D. et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinforma. 11, 119 (2010).

Wu, M. & Scott, A. J. Phylogenomic analysis of bacterial and archaeal sequences with AMPHORA2. Bioinformatics 28, 1033–1034 (2012).

Fu, L. M., Niu, B. F., Zhu, Z. W., Wu, S. T. & Li, W. Z. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 3150–3152 (2012).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336 (2010).

Edgar, R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26, 2460–2461 (2010).

Kieft, K., Zhou, Z. C. & Anantharaman, K. VIBRANT: automated recovery, annotation and curation of microbial viruses, and evaluation of viral community function from genomic sequences. Microbiome 8, 90 (2020).

Guo, J. R. et al. VirSorter2: a multi-classifier, expert-guided approach to detect diverse DNA and RNA viruses. Microbiome 9, 37 (2021).

Roux, S. et al. Minimum information about an uncultivated virus genome (MIUViG). Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 29–37 (2019).

Nayfach, S. et al. CheckV assesses the quality and completeness of metagenome-assembled viral genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 578–585 (2021).

Wu, S. F. et al. DeePhage: distinguishing virulent and temperate phage-derived sequences in metavirome data with a deep learning approach. Gigascience 10, giab056 (2021).

Shang, J. Y., Jiang, J. Z. & Sun, Y. N. Bacteriophage classification for assembled contigs using graph convolutional network. Bioinformatics 37, I25–I33 (2021).

Gregory, A. C. et al. The gut virome database reveals age-dependent patterns of virome diversity in the human gut. Cell Host Microbe 28, 724–740 (2020).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 955–964 (1997).

Paez-Espino, D. et al. Uncovering Earth’s virome. Nature 536, 425–430 (2016).

Galiez, C., Siebert, M., Enault, F., Vincent, J. & Soding, J. WIsH: who is the host? Predicting prokaryotic hosts from metagenomic phage contigs. Bioinformatics 33, 3113–3114 (2017).

Roux, S. et al. iPHoP: An integrated machine learning framework to maximize host prediction for metagenome-derived viruses of archaea and bacteria. PLoS Biol. 21, e3002083 (2023).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIANOMD. Nat. Methods 12, 59–60 (2015).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Van Kempen, M. et al. Fast and accurate protein structure search with Foldseek. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 243–246 (2024).

Dixon, P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 14, 927–930 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We thank Guangdong Magigene Biotechnology Co., Ltd. China for the assistance in data analysis. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32170014, Z.S.H.; 42207145, Y.L.Q.; 32300001, L.Z.H.). We acknowledge that no specific sampling permissions were required for the sites used in this study, as they are publicly accessible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.G.X., H.C.J., and Z.S.H. conceived the study. J.Y. and H.C.J. performed the sample collection. S.Q.L., H.L.Y., D.W.X., and J.Y. performed the measurement of physiochemical parameters and DNA extraction. Y.G.X., Y.L.Q., Z.H.L., Y.N.Q., and Z.S.H. performed the metagenomic analyses, genome binning, functional annotation, and evolutionary analysis. Y.G.X., Y.L.Q., H.C.J., Z.M.W., and Z.S.H. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Somaparna Ghosh

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, YG., Qi, YL., Luo, ZH. et al. Lake salinization on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau alters viral community composition and lifestyles. Commun Earth Environ 6, 49 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02037-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02037-2