Abstract

High-titanium mare basalts were among the earliest rocks to be returned from the Moon, but key aspects of their formation remain enigmatic. Here we show twenty partial remelting experiments conducted on three bulk compositions based on shallow ilmenite-bearing cumulate compositions from experimental studies of lunar magma ocean crystallization, with varying amounts of plagioclase. Melts produced at about 1200–1250 °C and 0.4 gigapascal with residual iron metal, representing approximately 40 percent partial melting, are close to high-Ti mare basalt compositions in terms of both TiO2 content and magnesium number. These results, compared with Monte-Carlo simulations and modelled rare earth element abundances and samarium–neodymium-lutetium–hafnium isotopic signatures of the experimental melts, remove the requirement of a deep origin of the lunar high-Ti mare basalts. Instead, they provide new evidence supporting the hypothesis that high-degree impact-induced partial melting at shallow depth, with minor post-formation modification, played a key role.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Titanium contents of lunar volcanic rocks

Lunar mare basalts and ultramafic glass beads retrieved by sample return missions (Luna, Apollo, and Chang’E) show ranges of compositions and formation times that differ substantially from the most abundant terrestrial basalts1,2,3,4,5. One key difference is in their TiO2 content. Mid-ocean ridge basalts (MORBs) exhibit a narrow range of TiO2 contents, with an average of approximately 1.6 wt.%6. In contrast, lunar mare basalts as well as ultramafic glass beads exhibit a wide range of TiO2 contents1,2,3,4,5, which is used as a basis for subdivision into three major groups (i.e., <1 wt.% TiO2 = very low-Ti or VLT basalts, l–6 wt.% = low-Ti basalts; >6 wt.% = high-Ti basalts) (Fig. 1)7. Petrological, trace element, and isotopic studies suggest that neither the mare basalts nor the ultramafic glass beads were formed by partial melting of primitive, undifferentiated lunar mantle material8,9,10. Instead, remelting of components of a chemically differentiated and stratified lunar mantle, resulting from cooling and crystallization of the lunar magma ocean (LMO), played a key role in their formation11,12,13,14. The ultramafic glass beads formed through rapid cooling of lunar magma15, whereas the coarse-grained texture of mare basalts indicates slower crystallization rates3. Although both materials exhibit a similarly wide range of TiO₂ contents3, their diverse trace element characteristics suggest that the mantle source of mare basalts is compositionally distinct from that of the glass beads16. Consequently, the genetic relationship between lunar high-Ti mare basalts and high-Ti glasses also remains uncertain13,14,16. This study focuses specifically on the origin of the high-Ti mare basalts.

Origin of high-titanium signal

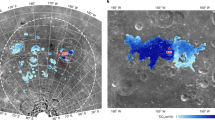

The very high abundances of titanium in the high-Ti mare basalts require involvement of one or more titanium-rich subsurface mineral phases1,3,7,17,18. Ilmenite, armalcolite, and rutile appear to be the only lunar minerals sufficiently rich in Ti to provide a viable source for the Ti in these samples19. The formation, chemical composition, and dynamic behavior of lunar subsurface reservoirs containing these TiO2-rich minerals in the context of the LMO model have been studied extensively over the past decades17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Nevertheless, key aspects of the formation of the high-Ti mare basalts, including the composition of their source, their depth(s) of origin, as well as the process(es) that caused partial melting in the first place, have not been resolved. This continues to hamper the development of comprehensive, self-consistent models tying together the timing and compositions representative for mare volcanism (recently expanded with the identification of young, ~2 Ga mare basalt samples with an average TiO2 content of 5.7 wt.% returned by Chang’e-54,5) with the interior thermal and chemical evolution of the Moon. There is broad consensus that the initial formation of the Ti-rich reservoir involved in the generation of the high-Ti mare basalts took place at shallow depth (from ~100 km depth to lunar surface) in the Moon (pressure from 0.5 gigapascal (GPa) to atmospheric pressure), during the last stages of the crystallization of the LMO13,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Experimental and numerical models of LMO crystallization indicate that during LMO cooling, olivine and orthopyroxene crystallized first to form a deep dunite to harzburgite lunar mantle, with plagioclase and clinopyroxene appearing later at >68% LMO solidification26,28. The density contrast between relatively low-density plagioclase and the residual magma ocean melt from which they crystallized led to their buoyant rise, forming the plagioclase-rich anorthosite crust. Once crystallization reaches ~95% solid, a titanium-rich, dense cumulate layer, the ilmenite-bearing cumulate layer (IBCL) forms at shallow levels just underneath this floatation crust26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Scientists agree on the fact that the density structure of the lunar mantle after solidification was unstable21,22,23,24. High-density (~3719 kg m−3) IBCL overlying less dense (~3396 kg m−3) harzburgite lunar mantle introduced a gravitational instability33, that is thought to have driven a mantle overturn of the LMO cumulate pile21,22. Dense IBCL would then sink down into deep lunar mantle until the core-mantle boundary (CMB)17,23. The sinking of IBCL would also result in a heterogeneous lunar interior, mixing Fe–Ti rich cumulates with primitive harzburgite, which has been considered to serve as the mantle source of high-Ti magma17,18. This hypothesis is supported by the observed attenuation of seismic waves near the lunar CMB which could be caused by the presence of IBCL23,34. The hypothesis is also supported by experimental studies on Multiple Saturation Points (MSPs) of lunar high-Ti picritic glass beads2,35. MSPs are considered to give an indication of the minimum depth at which a melt last equilibrated with its source14. Petrologic experiments suggest high-Ti pyroclastic glasses originated from a heterogeneous lunar interior at depths between 250 and 550 km, corresponding to pressures of ~1.3–2.5 GPa35,36,37,38.

Deep versus shallow formation

These models are not without challenges. There is no agreement on whether high-Ti melts in the deep lunar interior could have been buoyant relative to the surrounding mantle17,20,39,40,41, allowing them to erupt at the surface. Previous studies indicate that the sinking of IBCL is inefficient17,22,23, with ~30–50% of the primary IBCL remaining at shallow depths throughout lunar history33. Moreover, melting experiments on Apollo high-Ti mare basalts 70017 and 70215 indicated that they can be generated from 100–150 km depth within the Moon10. These considerations all contribute to continued uncertainty over the role of deep and/or shallow processes in high-Ti mare basalts genesis.

Here, we show the results of a series of partial melting experiments at low pressure (~0.4 GPa) and a range of temperatures (1050–1350 °C) on three bulk compositions. All three are based on LMO crystallization step LBS10 from the experimental study of Lin et al. 28. This is the first step that yielded ilmenite and thus an IBCL. Varying amounts of plagioclase were added to the LBS10 composition to assess the effect of inefficient plagioclase extraction during the late stages of LMO crystallization. Experimental results were augmented with thermodynamic modeling of partial melting of the second ICBL formed during later LMO crystallization step LBS1128. Our results are compared with the major and trace element compositions, as well as isotopic systematics, of high-Ti mare basalt samples to further assess the source depth and formation mechanism of these enigmatic rocks.

Results

Bulk compositions, phase relations and demonstration of equilibrium

Major element compositions of the starting materials, obtained through electron microprobe analysis (EMPA) of glasses of starting materials, are summarized in Table 1. Composition HTP1 is close to the target composition of the LBS10 cumulate in ref. 28. Compositions HTP2 and HTP3 are enriched in Ca and Al compared to HTP1 due to the addition of the plagioclase component. The experimental conditions and phases present in all experiments (covering a temperature range between 1050 and 1350 °C) are summarized in Table 2. Back-scattered electron images of representative experimental products are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Their major element compositions and phase proportions derived from mass balance calculations are presented in Supplementary Table 1. The mineral assemblages that were identified in the experiments are Orthopyroxene (Opx)±Armalcolite (Arm)±Ilmenite (Ilm)±Olivine (Ol)±Quartz (Qtz)±Iron in HTP1, Opx±Arm±Ilm±Ol±Iron in HTP2, and Opx±Arm±Ilm±Ol±Rt±Iron in HTP3, with quenched silicate melt present as glass in all run products. The homogeneity of the analyzed minerals and melts, the straight mineral-melt textural contact without resorption textures, and the Opx/Ol-melt Fe-Mg exchange coefficients (KD) confirm that equilibrium was achieved during the experiments (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Microprobe analyses of different crystals within a single run product result in comparable element concentrations, with no obvious core to rim variations or within-sample heterogeneity. Opx crystals occasionally exhibit slight compositional zoning but resulting standard deviations in oxide component abundances are less than 2.5 wt.% (Supplementary Table 1). The length of TiO2-rich minerals is about 3–30 μm (Supplementary Fig. 1). Opx crystals have ilmenite inclusions, and show poorly defined crystal faces. Glasses are transparent and free of inclusions and bubbles.

The exchange coefficients (KD) for FeO–MgO partitioning between Opx and co-existing melt, and between Ol and co-existing melt are defined as: KD = (XFeO-Opx/Ol) (XMgO-melt)/(XFeO-melt) (XMgO-Opx/Ol) (Table 3)42. In this study, the KDFe–Mg values for Opx range from 0.20 to 0.30 (Supplementary Fig. 2a), while for Ol, they range from 0.27 to 0.34 (Supplementary Fig. 2b). These values are consistent with those reported in phase equilibrium experiments of high-Ti melts from previous studies32,36,43,44. The olivine-melt KDFe-Mg values decrease as the TiO₂ content of the melts increases (Supplementary Fig. 3). This is due to a rise in the FeO activity coefficient with increasing TiO₂, accompanying the formation of Fe-Ti complexes in the melts, which lowers the olivine-melt Fe-Mg exchange coefficients17,35,45.

Oxygen fugacity (fO2) in experiments

The graphite-lined capsule was used to control oxygen fugacity and reduce the iron, added as Fe2O3 in the starting materials46,47. Raman spectroscopic analysis on representative run products (Supplementary Fig. 4) confirmed the negligible presence of CO2, CO32− or any other C–O–H species in the glasses due to eventual oxidation of graphite46. Although at elevated pressures (>1 GPa) the oxygen fugacity for the graphite-carbon dioxide (CCO) buffer is consistently between 1 and 2 log units above that of the iron-wüstite (IW) buffer35,47, the presence of iron metal in low-temperature experiments at 0.4 GPa indicates that the fO2 of the CCO buffer approaches that of iron-wüstite (IW) buffer at low pressure, as previously reported by refs. 47,48 and specifically related to the Moon36 and references therein. Iron metals are C-saturated as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Major element compositions of silicate melts

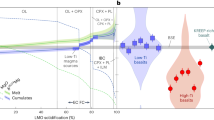

The experimental melt compositions are summarized in Table 3. As the experimental temperature increases from 1070 °C to 1350 °C, the melt proportion rises from 10% to 87% (Supplementary Fig. 6). This leads to an increasing of MgO content from 3.60 wt.% to 15.31 wt.% and Mg# ranges from 33–56 (Supplementary Fig. 7). In contrast, melt CaO and Al2O3 decrease steadily from a maximum of 10.77 wt.% to a minimum of 3.60 wt.% and a maximum of 15.83 wt.% to a minimum of 3.76 wt.%, respectively. SiO2 concentration of melt remains in a fairly restricted range of 40.62 wt.%–53.52 wt.% in all the experiments. The FeO content of the silicate melt ranges between 11.93 wt.% and 24.38 wt.% among the three experimental series. TiO2 is highest in melts formed after melting out of ilmenite and armalcolite (12.96 wt.% in HTP1, 11.06 wt.% in HTP2 and 9.72 wt.% in HTP3) and then decreases with further heating (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The evolution of TiO2 content of experimental melts is shown in Fig. 2, and representative TiO2 content ranges (9–13 wt.%) of Apollo mare basalts are reached at 1150–1300 °C. Although the TiO₂ contents of some high-Ti mare basalts are higher than 13 wt.%, the average TiO₂ content of high-Ti mare basalts is approximately 11 wt.%49, and a density plot of high-Ti basalts shows that the TiO₂ content of most samples is concentrated around 12 wt.%50. This is consistent with our experimental results shown in Fig. 2. Figure 3 further shows a comparison between the major element composition of melts produced in the three series of experiments from this study, and the compositions of Apollo high-Ti mare basalts51. At experimental temperatures of approximately 1220–1260 °C, corresponding to partial melt proportions of ~35–55 per cent (Supplementary Fig. 6), abundances of TiO2, MgO and FeO in melts, and melt Mg#, from the three experimental series are consistent with the compositions in high-Ti mare basalts (Fig. 3b–d). Partial melts generated from the starting composition of the IBCL mixed with 5 wt.% plagioclase best fit the compositional characteristics of high-Ti mare basalts. In contrast, the melts have SiO2 contents over 40 wt.%, whereas the average SiO2 content of the high-Ti mare basalts is lower than 40 wt.% (Fig. 3a)49. All partial melts yield lower CaO content compared to high-Ti mare basalts, irrespective of the percentage of plagioclase added to the source (Fig. 3e).

Previous phase equilibrium experiments were performed on a hybrid lunar mantle with a small amount of entrained plagioclase (MOCH, Table 1)52. The experimental melts in their study failed to match the Al2O3 contents of high-Ti mare basalts. Since the Al2O3 content of the MOCH composition was only 2.64 wt.%, we propose that the amount of added plagioclase may be insufficient to generate melts with adequate Al2O3 content13. The same problem was encountered in petrologic studies on melting a hybrid lunar mantle without plagioclase (TiCum±TWM50, Table 1). Experiments based on TiCum±TWM50 compositions produced melts with lower Al₂O₃ content compared to high-Ti mare basalts17,53, highlighting the role of plagioclase in the source to generate the right amount of Al₂O₃ component during melting13.The latest remelting study proposed a harzburgite lunar mantle cumulate (CMV, Table 1), consisting of 50–60% harzburgite, 9–20% IBCL (0.2cpx + 0.8ilm), and 30–40% urKREEP, to produce the lunar high-Ti pyroclastic glasses18. However, a large amount of urKREEP addition will lead to very high concentrations of incompatible elements54, resulting in a mismatch with the REE concentrations of high-Ti mare basalts. In addition, the model of ref. 18 cannot fully reproduce the natural composition of the most primitive lunar high-Ti basaltic glass beads.

The IBCL composition used in our piston-cylinder experiments (0.97cpx + 0.03ilm) was based on step LBS10 from ref. 28, which produced melts with slightly higher SiO₂ and lower CaO compared to high-Ti mare basalts (Fig. 3a, e). In contrast, the later formed IBCL in ref. 28 (step LBS11) consists of 0.98cpx + 0.02ilm, and it has lower SiO₂ (37.46 wt.%) and higher CaO (3.95 wt.%) contents than the ICBL formed in LBS10. We hypothesize that it may be possible to eliminate the gap in Fig. 3a, e and achieve the composition of high-Ti mare basalts by remelting LBS11, or a mixture of LBS10 and LBS11, or a combination of LBS10, LBS11, plagioclase, and additional clinopyroxene (cpx) to account for the low CaO content observed in our experiments at shallow depths.

In order to test this hypothesis, melting simulations were conducted by combining the Monte Carlo method with alphaMELTs software (Supplementary Fig. 8). Out of 100,000 simulations, 1955 successfully reproduced the compositions of the high-Ti mare basalts (Fig. 3). These successful simulations are characterized by melting temperatures in the ranges of 1180–1200 °CC and melt fractions exceeding 30%, for sources containing approximately 0–15% LBS10 cumulate, 55–70% LBS11 cumulate, and minor plagioclase and clinopyroxene. The addition of a LBS11 cumulate component decreases the SiO2 content of partial melts compared to the results of our experiments based on LBS10, and the addition of plagioclase and clinopyroxene largely elevate the Al2O3 and CaO concentration as well as the ratio of CaO/Al2O3 of partial melt. In summary, remelting experiments and simulations support the idea that high-Ti mare basalt compositions can be reproduced by remelting of a shallow-depth hybrid lunar mantle, composed of IBCL+plagioclase+clinopyroxene.

Previous studies suggested that the high-Ti magmas could come from partial melting of heterogeneously mixed olivine +clinopyroxene +Fe-Ti-oxide sources at depth after overturn8,13,17,18,51,52,55. High-pressure melting experiments on Apollo high-Ti mare basalt compositions indicate that they could only be generated by partial melting of an harzburgite +Fe-Ti-oxide source at pressures exceeding 0.5–0.75 GPa10, higher than the pressure of 0.4 GPa used in our work. The reason for this discrepancy in estimated depth of origin is likely due to the fact that the Apollo sample compositions used in this previous work did not represent the high-Ti mare basalts parent composition13. Remelting experiments on a clinopyroxene-ilmenite cumulate composition containing 9.1 wt.% TiO2 had been conducted at pressures of 1 atm and 1.3 GPa to investigate the origin of lunar high-titanium ultramafic glasses53. The evolution of melt TiO2 content as a function of melt fraction in previous studies17,53 is consistent with our results (Fig. 2b). Our experiments at 0.4 GPa yield high melt TiO2 contents comparable to those achieved in ref. 53 at lower melt fractions and lower starting material TiO2 contents. To complement major element abundance considerations, we assess if a shallow remelting mechanism is consistent with the observed trace element patterns and isotope systematics of the high-Ti basalts. We focus on the rare earth elements (REE), and on Sm-Nd-Lu-Hf isotopic systematics. Because high-Ti mare basalt samples may have experienced post-formation modification by processes such as assimilation and/or fractional crystallization, the REE concentrations of estimated parental magmas of high-Ti mare basalt13 were used in this study. The parental magma of high-Ti mare basalt refers to the most primitive (high Mg#) high-Ti mare basalt sample (among Apollo 11 and 17 samples), which contains the lowest incompatible element abundances alongside relatively high abundances of compatible elements13. The parental magma for high-Ti mare basalts13 exhibits a medium REE-enriched pattern with (La/Sm)n < 1 and a negative Eu anomaly (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 2).

We began by calculating the REE patterns of IBCL28 used in this study. Due to the low REE concentrations in IBCL (Fig. 4), only very small partial melt percentages of 1–5% could yield melt REE concentrations consistent with observations. This degree of melting is far lower than the degree of melting required for major elements (Fig. 2b). The very low incompatible trace element contents in pure IBCL have been noted in trace element modeling of lunar basalts many times before5,13,56. Therefore, various percentages of incompatible-enriched TIRL (trapped instantaneous residual liquid) are required to match source compositions with observed parental magmas13,56,57. In general, TIRL percentages are thought to be less than 5%13,56,57. We assume addition of 2% TIRL in our trace element models. The REE pattern of this TIRL-bearing source is shown in Fig. 4, as is the REE pattern of a 40% partial melt of TIRL-bearing IBCL source. The slope of modeled REE contents of middle to heavy REE are consistent with the high-Ti parental magma (Fig. 4). However, the modeled Eu anomaly is slightly shallower than observed, the melt light REE concentrations are lower than observed, and the light REE slope is steeper. The models described above do not take into account the effect of the participation of small amounts of the very LREE-enriched and Eu-depleted urKREEP reservoir18,54,56 in the formation of the high-Ti mare basalts. Because this reservoir initially forms between the proposed source depth of the high-Ti mare basalts and the surface during LMO crystallization, it is likely that high-Ti melts interacted with the overlying urKREEP reservoir during their ascent. Figure 4 shows that post-formation melt modification by assimilation of a very small amount of the urKREEP reservoir (<1%) is sufficient to both increase the light REE concentrations, flatten the light REE slope, and decrease the Eu anomaly, all to levels found in the parental high-Ti mare basalts, while keeping the slope of HREE concentrations constant.

Independent constraints on the extent of urKREEP participation in the formation of high-Ti mare basalts is provided by the Lu-Hf-Sm-Nd isotopic systematics of high-Ti mare basalt samples58,59. We calculated the 147Sm/144Nd and 176Lu/177Hf ratios of high-Ti melts based on the same evolution pathway that was used in the REE modeling (i.e., the IBCL from ref. 28, with 5% added plagioclase and 2% TIRL). Supplementary Fig. 9 shows a compilation of recent measurements of the source 147Sm/144Nd and 176Lu/177Hf ratios of lunar high-Ti basalt samples59, together with the modeled source isotopic characteristics. The modeled 147Sm/144Nd and 176Lu/177Hf ratios are both higher than observed in the samples. If we include a small percentage (<0.6 wt.%, consistent with the percentage needed to fit the REE observations) of urKREEP reservoir54,60, our model results match the observed result. Taken together, REE abundances, Lu-Hf-Sm-Nd isotopic data, as well as major element considerations all support the hypothesis that the lunar high-Ti mare basalts were formed by low-pressure, high-degree partial melting of an ilmenite-bearing source. This source contained small percentages of imperfectly segregated plagioclase, TIRL, and a small but important amount of urKREEP component. Many driving forces for lunar mare basalt and lunar picritic glass bead volcanism have been proposed, including external heat induced by impact61,62, convection caused by mantle overturn50, internal heat driven by high abundances of radiogenic heat-producing elements63,64, core-mantle friction65, the release of latent heat that accompanies the growth of an inner core growth66, and tidal heating67. The high cooling rates of lunar glass beads indicated a fast transport mechanism that they were formed and transported into the cold lunar vacuum14 during volcanic fire-fountain eruptions68,69. Although the lunar interior was thermally inhomogeneous at various scales61,63,64, lunar interior heating sources were insufficient to produce a high degree of partial melting of LMO cumulates at the time of high-Ti mare basalts formation70. The high-Ti mare basalts sampled to date contain only 0.4–2.9 μg g-1 Th, 0.1–0.8 μg g−1 U, and 460–2440 μg g−1 K on average71, showing there is no evidence for highly elevated concentrations of these radioactive elements70.

Elevated volatile element abundances can potentially lead to high partial melt fractions. Estimates of the volatile contents of high-Ti mare basalt source region, based on measurements of the volatile content of apatite crystals, are relatively low (4–28 ppmw)72. However, recent studies on high-Ti pyroclastic glass beads in sample 74,220 indicate that some pre-eruptive melts can contain up to nearly 1600 ppmw H2O73,74. Although the timeline of the volatile depletion from the Moon is not fully clear75,76, previous research has shown that the carbon amount in lunar glasses and melt inclusions is sufficient to trigger fire-fountain eruptions77, explaining the formation of microscopic glass beads36.

Based on our modeling results, we argue in favor of shallow high-degree partial melting caused by an external source: impact heating61. Numerical simulations reveal that interior convection in the Moon caused by the larger impacts during late accretion of material to the Moon could cause extensive periods of decompression melting lasting many millions of years61. This is consistent with the starting time as well as duration of lunar volcanism62,78. Numerical models61 suggest that a large impact can lead to temperatures of 1250 ± 10 °CC at the depth of ~80 km (~0.4 GPa), which is consistent in both pressure and temperature with required partial melting conditions in our experimental and modeling results.

Conclusions

Partial melting experiments of late-stage lunar cumulate compositions with variable proportions of plagioclase formed during the crystallization of the lunar magma ocean at low pressure were conducted. These experiments indicate that the lunar high-TiO2 mare basalts were formed by large-degree partial melting of a shallow source. A deep source suggested by studies of multiple saturation points is not required. Our hypothesis is supported by major and trace element observations as well as isotopic considerations. This formation process is consistent with an impact-induced triggering mechanism for lunar volcanism. Large impacts may have had an important role in the history of volcanism on the Moon.

Methods

High-pressure and high-temperature experiments

This study aims at simulating partial melting of a IBCL at shallow depth (~80 km), corresponding to a pressure of 0.4 GPa, based on the assumption of the LMO cumulate remelting hypothesis. As illustrated in Table 1, experimentally derived estimates for the major element composition of the IBCL are model-dependent32. They vary as a function of the assumed bulk initial LMO composition, the assumed initial LMO depth, assumptions about the dominance of equilibrium or fractional crystallization during LMO crystallization28,29,32, and the assumed efficiency of the density-driven segregation of plagioclase from more mafic cumulate minerals during late-stage LMO crystallization30. We selected a late-stage cumulate composition (LBS10 cumulate, formed after 96.4% solidification) reported in ref. 28 as a basis for our starting materials. The bulk silicate Moon composition used in ref. 28 contains ~ 0.53 wt.% TiO2, which is higher than other initial LMO compositional models. The higher TiO2 content accelerates the crystallization of ilmenite and leads to a high Mg# of the IBCL components used in this study.

For the first compositional end member of our experiments, we assume perfect segregation of plagioclase from the more mafic minerals in LBS10, leaving a pure pyroxene+ilmenite cumulate (starting material HTP1, Table 1). It is well established that an idealized end member is unlikely to provide a realistic source for high-Ti mare basalts7. Observations of magma chamber processes on Earth indicate that mineral-mineral and mineral-magma separation during crystallization are never completely efficient79,80. This is also underlined by high (> 8 wt.%) Al2O3 contents of the high-Ti basalts, suggesting inefficient separation of plagioclase from more mafic minerals crystallizing from the LMO at the same time during formation of the IBCL. We attempt to quantify the effect of the addition of plagioclase on remelting the IBCL by studying the melting behavior of two additional starting compositions, derived from HTP1 by adding 5% (HTP2) and 10% (HTP3) plagioclase to the plagioclase-free LBS10 cumulate composition of ref. 28 (HPT1). Nominal bulk compositions synthesized for this study are shown in Table 1, and contain between 5.4 and 6.1 wt.% TiO2 and between 2.9 and 5.7 wt.% Al2O3. The effect of inefficient magma separation from the IBCL cumulates, leading to the incorporation of small percentages of trapped instantaneous residual liquid (TIRL, LBS10 liquid28 in this study), will be assessed in the trace element modeling of the high-Ti basalts, and is not taken into account in our choice of major element starting compositions.

Starting compositions were prepared by mixing appropriate amounts of high-purity powdered oxides (MgO, Fe2O3, Al2O3, TiO2, SiO2) and carbonate (CaCO3). The oxides MgO, Al2O3, TiO2 and SiO2 were first fired overnight at 1000 °C and then stored at 110 °C until required. The other oxides and calcium carbonate were dried at 110 °C overnight prior to use. The nominally dry starting materials were mixed using ethanol in an agate mortar for 1 hour, dried in air, and decarbonated in a Pt crucible in a box furnace by gradually raising the temperature from 650 to 1000 °C in approximately 7 h. The platinum (Pt) crucible had previously been iron-saturated to minimize iron loss. The resulting mixtures were melted at 1550 °C for 20 min to ensure homogeneity and quenched to glass by immersing the bottom of the Pt crucible in water. Small aliquots of the glasses were collected for compositional analyses. The remaining powder of the material was subsequently crushed, dried, and reground under ethanol in an agate mortar for 1 h, and kept at 110 °C until use.

High-pressure, high-temperature experiments were conducted in an end-loaded piston cylinder device at Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research, using \(3/4\)-inch diameter talc-pyrex assemblies. The pressure was calibrated based on the NaCl melting curve at 0.7 GPa-940 °C and 1 GPa-1000 °C81,82 and the quartz-coesite phase transition at 3.18 GPa and 1100 °C83. The resulting friction correction is ~3%, consistent with literature values for comparable high-pressure assemblies82.

Starting material powder was packed tightly into a hand-machined graphite capsule (0.7 mm inner diameter), closed with a graphite plug and inserted in a Pt capsule (1.7 inner diameter). In order to ensure a minimal thermal gradient across the samples of less than 10 °C84, the sample lengths were limited to a maximum of 3 mm, and capsules was carefully placed at the center of the graphite heater and surrounded by crushable MgO spacers. MgO inner spacers and four-bore alumina tubes were dried at 1000 °C for at least 10 h to remove impurities. Assembly parts were stored at 120 °C for at least 24 h before use. Temperature was monitored using W5Re-W26Re (type C) and W3Re-W25Re (type D) thermocouples without an electromotive force (emf) pressure correction. Experiments were cold pressurized to target pressure and then heated to 800 °C with a ramp of 100 °C/min. This temperature was maintained for 1 h to compact the pores in the graphite inner capsule. For experimental final temperatures ≥1300 °C, the samples were further heated to the temperature of interest with the same ramp. For target temperatures <1300 °C, the experiments were first heated to a temperature of 1300 °C and maintained for 20 mins. Afterwards, the samples were cooled to the temperature of interest at a rate of 50 °C per minute while maintaining target pressure. Experiments were kept at their final target temperatures for 6–96 h.

The pressure was 0.4 GPa in all experiments. The experimental pressure was chosen based on the depth at which the ilmenite-bearing cumulates initially form. Previous lunar magma ocean crystallization studies27,28,29,30 showed that the ilmenite phase appears at ~ <0.3–0.5 GPa. The pressure corresponding to the LBS10 chemical composition was identified as 0.4 GPa28. Although 0.4 GPa is around the lower limit for a piston-cylinder device85, this specific pressure is not strictly required for the generation of mare basalt liquids, making potential pressure errors in such piston-cylinder experiments (± 30%) acceptable. Runs were quenched by cutting power to the heater and the temperature typically dropped below 100 °C in <50 s.

Experimental run products were mounted in epoxy, polished and carbon-coated for back-scattered electron (BSE) imagery and EMPA. The chemical composition of the run product phases (minerals and quenched melts) was determined using a JEOL JXA-8230 Electron Microprobe at the Testing Center of Shandong Bureau of China Metallurgical Geology Bureau. Analyses were performed using an accelerating voltage of 15 kV and a beam current of 20 nA for Si, Ti, Al, Fe, Mg and Ca. The mineral and melt proportions were determined by mass balance calculations, using compositional analyses of super-liquidus glass samples as bulk composition constraints. We used properly beams of 1 and 10 μm diameter for the mineral phases and quenched melts, respectively. Analyses were calibrated against primary standards of diopside (Ca, Si), fayalite (Fe), ilmenite (Ti), olivine (Mg) and orthoclase (Al). Peak areas were converted to concentrations using standard values. Peak count times were 20 s and background count times 10 s.

To assess the presence of hydrogen and/or carbon-bearing species in the experimentally produced melts, unpolarized Raman spectroscopic measurements were performed by a HORIBA LabRAM HR Evolution laser Raman spectrometer with a 50× microscope objective at Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research (HPSTAR). All spectra were excited by a 532 nm solid-state laser and collected in the wavenumber range from 200 to 3600 cm-1, using 10 s exposure time and 3 accumulations and with a spectral resolution of 4 cm-1.

Rare earth element and Sm–Nd–Lu–Hf isotope modeling

To complement major element abundance considerations, we assess if a shallow remelting mechanism is consistent with the observed trace element patterns and isotope systematics of the high-Ti basalts. We focus on the rare earth elements (REE), and on Sm–Nd–Lu–Hf isotopic systematics. In recent studies discussing the evolution of incompatible trace element concentrations in the Moon, typically a 1–2.5 times CI chondritic pattern is assumed to represent concentrations in a fully molten initial bulk Moon29,86. Given that the experiments in this study are based on a 700 km deep initial lunar magma ocean28, initial incompatible concentrations in this LMO should be higher than these values regardless of the exact mineralogy in the Moon between 700 km depth and the core-mantle boundary13. Therefore, we assume initial concentrations of the REE in the 700 km deep LMO were 4–5× CI chondritic values74 following that in ref. 13.

The evolution of REE and Hf concentrations in magma and minerals during LMO crystallization were quantified using methods used in previous studies29,60,86. To maintain consistency with the LMO crystallization study that formed the basis of our choice of experimental starting materials28, we modeled trace element and isotopic evolution assuming a two-stage model involving equilibrium crystallization followed by fractional crystallization, starting from an initial magma ocean with a depth of 700 km. The residual melt from the equilibrium crystallization stage serves as the initial melt for the fractional crystallization stage. Similarly, the residual melts from step i of fractional crystallization become the initial melt for the subsequent fractional crystallization step i + 1. REE and Hf concentrations in magma at the first equilibrium crystallization stage are calculated using the equation:

REE and Hf concentrations in the liquid at the second fractional crystallization stage are calculated using the equation:

REE concentrations in the minerals are calculated using the equation:

In Eq. (1)-(3), \({C}_{0}\) is the initial bulk LMO trace element concentration, \({C}_{{L}_{1}}\) is the trace element concentration of residual melt in equilibrium crystallization stage and \({C}_{{L}_{i}}\) (i ≥ 2) is the trace element concentration of residual melt in fractional crystallization stage, where i indicates the specific fractional crystallization step. \({C}_{{S}_{i}}\) is the trace element abundance of minerals and cumulates in each crystallization step, F is the melt fraction, and \({D}_{{Bulk}}\) is the weighted average bulk partition coefficient for each trace element calculated based on the nature and modes of all mineral phases present in each step. The REE partition coefficients between minerals and melts used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Towards the final stages of LMO crystallization, the residual magma ocean becomes progressively enriched in incompatible elements including potassium, rare earth elements, and phosphorus (KREEP). The resulting geochemical reservoir, originally situated at the bottom of the plagioclase-rich crust, is termed urKREEP54. An urKREEP signature has been identified in several suites of lunar magmatic rocks, both in terms of REE elemental concentrations and isotopic data. Isotopic studies of the 147Sm/144Nd, 87Rb/86Sr, and Hf isotopic ratios of lunar basalts indicate that the contribution of urKREEP into high-Ti mare basalts is limited5,58,59. To quantify the extent of urKREEP involvement in high-Ti basalt formation, we first calculated the REE concentrations as well as 147Sm/144Nd and 176Lu/177Hf ratios87 of urKREEP following 99.9% crystallization. Then we modeled the REE and isotopic evolution of the proposed high-Ti mare basalts mantle source with the involvement of urKREEP. This calculation was based on the LMO crystallization sequence proposed in ref. 28.

Monte-Carlo remelting simulations

To better quantify whether using LBS11 cumulates, or a combination of LBS10 and LBS11 cumulates in the source region, with varying amounts of added plagioclase and clinopyroxene would yield melts with major element abundances even closer to those of the high-Ti basalts, we performed remelting simulations by combining the Monte-Carlo method with alphaMELTs software. We followed the approach used in ref. 88. By varying temperatures and source major element compositions, we carried out 100,000 remelting simulations using alphaMELTS software89. The pressure and \({f}_{{O}_{2}}\) used in each run are 0.4 GPa and IW-1, respectively. The thermal conditions were constrained to a range of 1100–1300 °C, based on our experiments. The mantle source compositions were assumed to be a mixture of four components: LBS10 cumulate (0–100%), LBS11 cumulate (0–100%)28, plagioclase (0–20%)90 and clinopyroxene (0–15%)91. A uniform distribution was assumed for each parameter within the specified ranges. Given the relatively wide compositional range exhibited by the Apollo high-Ti samples, simulations were deemed successful if the liquid composition returned by alphaMELTS fit within the component oxides’ mean value ± 2 wt.% of high-Ti mare basalt compositions49. This minimizes the effect of data points located at the edges of each oxide concentration ranges.

Data availability

The datasets of this paper are available through Mendeley at: https://doi.org/10.17632/gxknx2vd25.1.

Code availability

Monte-Carlo simulation was performed based on the alphaMELTS software, available at https://magmasource.caltech.edu/alphamelts/, and the simulation code is available on Github at https://github.com/778aha/Lunar-MC.

References

Papike, J. J., Hodges, F. N., Bence, A. E., Cameron, M. & Rhodes, J. M. Mare basalts: crystal chemistry, mineralogy, and petrology. Rev. Geophys. 14, 475–540 (1976).

Delano, J. W. & Livi, K. Lunar volcanic glasses and their constraints on mare petrogenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 45, 2137–2149 (1981).

Longhi, J. Experimental petrology and petrogenesis of mare volcanism. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 26, 2235–2251 (1992).

Che, X. et al. Age and composition of young basalts on the Moon, measured from samples returned by Chang’E-5. Science 374, 887–890 (2021).

Tian, H. C. et al. Non-KREEP origin for Chang’E-5 basalts in the Procellarum KREEP terrane. Nature 600, 59–63 (2021).

Gale, A., Dalton, C. A., Langmuir, C. H., Su, Y. & Schilling, J.-G. The mean composition of ocean ridge basalts. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 14, 489–518 (2013).

Neal, C. R. & Taylor, L. A. Petrogenesis of mare basalts: a record of lunar volcanism. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 2177–2211 (1992).

Shearer, C. K. & Papike, J. J. Magmatic evolution of the Moon. Am. Mineral. 84, 1469–1494 (1999).

Shearer, C. K. et al. Thermal and magmatic evolution of the Moon. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 60, 365–518 (2006).

Longhi, J., Walker, D., Grove, T. L., Stolper, E. M. & Hays, J. F. The petrology of the Apollo 17 mare basalts. Proc. Lunar Planet. Sci. Confer. 5, 447–469 (1974).

Walker, D., Longhi, J. & Hays, J. F. Differentiation of a very thick magma body and implications for the source regions of mare basalts. Proc. Lunar Planet. Sci. Confer 6, 1697–1722 (1975).

Warren, P. H. The magma ocean concept and lunar evolution. Annu Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 13, 201–240 (1985).

Snyder, G. A., Taylor, L. A. & Neal, C. R. A chemical model for generating the sources of mare basalts combined equilibrium and fractional crystallization of the lunar magmasphere. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 3809–3823 (1992).

Grove, T. L. & Krawczynski, M. J. Lunar mare volcanism: where did the magmas come from? Elements 5, 29–34 (2009).

Hui, H. et al. Cooling rates of lunar orange glass beads. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 503, 88–94 (2018).

Shearer, C. K. & Papike, J. J. Basaltic magmatism on the Moon: A perspective from volcanic picritic glass beads. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57, 4785–4812 (1993).

Mallik, A., Ejaz, T., Shcheka, S. & Garapic, G. A petrologic study on the effect of mantle overturn: implications for evolution of the lunar interior. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 250, 238–250 (2019).

Haupt, C. P., Renggli, C. J., Rohrbach, A., Berndt, J. & Klemme, S. Experimental constraints on the origin of the lunar high-Ti basalts. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 129, e2023JE008239 (2024).

Thacker, C., Liang, Y., Peng, Q. & Hess, P. The stability and major element partitioning of ilmenite and armalcolite during lunar cumulate mantle overturn. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 820–836 (2009).

Elkins-Tanton, L. T., Van Orman, J., Hager, B. H. & Grove, T. L. Re-examination of the lunar magma ocean cumulate overturn hypothesis: melting or mixing is required. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 196, 239–249 (2002).

Dygert, N., Hirth, G. & Liang, Y. A flow law for ilmenite in dislocation creep: implications for lunar cumulate mantle overturn. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 532–540 (2016).

Yu, S. et al. Overturn of ilmenite-bearing cumulates in a rheologically weak lunar mantle. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 124, 418–436 (2019).

Xu, M., Jing, Z., Van Orman, J. A., Yu, T. & Wang, Y. Experimental evidence supporting an overturned iron-titanium-rich melt layer in the deep lunar interior. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099066 (2022).

Scholpp, J. L. & Dygert, N. Experimental insights into the mineralogy and melt-rock reactions produced by lunar cumulate mantle overturn. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 179, 58 (2024).

Elkins-Tanton, L. T., Burgess, S. & Yin, Q. Z. The lunar magma ocean: reconciling the solidification process with lunar petrology and geochronology. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 304, 326–336 (2011).

Elardo, S. M., Draper, D. S. & Shearer, C. K. Lunar magma ocean crystallization revisited: bulk composition, early cumulate mineralogy, and the source regions of the highlands Mg-suite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 3024–3045 (2011).

Lin, Y., Tronche, E. J., Steenstra, E. S. & van Westrenen, W. Evidence for an early wet Moon from experimental crystallization of the lunar magma ocean. Nat. Geosci. 10, 14–18 (2017).

Lin, Y., Tronche, E. J., Steenstra, E. S. & van Westrenen, W. Experimental constraints on the solidification of a nominally dry lunar magma ocean. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 471, 104–116 (2017).

Rapp, J. F. & Draper, D. S. Fractional crystallization of the lunar magma ocean: updating the dominant paradigm. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 53, 1432–1455 (2018).

Charlier, B., Grove, T. L., Namur, O. & Holtz, F. Crystallization of the lunar magma ocean and the primordial mantle-crust differentiation of the Moon. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 234, 50–69 (2018).

Schwinger, S. & Breuer, D. Employing magma ocean crystallization models to constrain structure and composition of the lunar interior. Phys. Earth Planet 322, 106831 (2022).

Schmidt, M. W. & Kraettli, G. Experimental crystallization of the lunar magma ocean, initial selenotherm and density stratification, and implications for crust formation, overturn and the bulk silicate moon composition. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 127, e2022JE007187 (2022).

Zhao, Y., de Vries, J., van den Berg, A. P., Jacobs, M. H. G. & van Westrenen, W. The participation of ilmenite-bearing cumulates in lunar mantle overturn. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 511, 1–11 (2019).

Weber, R. C., Lin, P.-Y., Garnero, E. J., Williams, Q. & Lognonné, P. Seismic detection of the lunar core. Science 331, 309–312 (2011).

Krawczynski, M. J. & Grove, T. L. Experimental investigation of the influence of oxygen fugacity on the source depths for high titanium lunar ultramafic magmas. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 79, 1–19 (2012).

Guenther, M. E., Brown Krein, S. M. & Grove, T. L. The influence of variable oxygen fugacity on the source depths of lunar high-titanium ultramafic glasses. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 334, 217–230 (2022).

Wagner, T. P. & Grove, T. L. Experimental constraints on the origin of lunar high-Ti ultramafic glasses. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61, 1315–1327 (1997).

Delano, J. W. Chemistry and liquidus phase relations of Apollo 15 red glass: Implications for the deep lunar interior. Proc. Lunar Planet. Sci. Confer. 11, 251–288 (1980).

van Kan Parker, M. et al. Neutral buoyancy of titanium-rich melts in the deep lunar interior. Nat. Geosci. 5, 186–189 (2012).

Sakamaki, T. et al. Density of high-Ti basalt magma at high pressure and origin of heterogeneities in the lunar mantle. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 299, 285–289 (2010).

Vander Kaaden, K. E., Agee, C. B. & McCubbin, F. M. Density and compressibility of the molten lunar picritic glasses: Implications for the roles of Ti and Fe in the structures of silicate melts. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 149, 1–20 (2015).

Roeder, P. L. & Emslie, R. F. Olivine-liquid equilibrium. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 29, 275–289 (1970).

Sun, C. & Liang, Y. Distribution of REE and HFSE between low-Ca pyroxene and lunar picritic melts around multiple saturation points. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 119, 340–358 (2013).

Collinet, M., Médard, E., Charlier, B., Auwera, J. V. & Grove, T. L. Melting of the primitive martian mantle at 0.5–2.2 GPa and the origin of basalts and alkaline rocks on Mars. Earth Planet Sci. Lett 427, 83–94 (2015).

Xirouchakis, D., Hirschmann, M. M. & Simpson, J. A. The effect of titanium on the silica content and on mineral-liquid partitioning of mantle-equilibrated melts. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65, 2201–2217 (2001).

Holloway, J. R., Pan, V. & Gudmundsson, G. High-pressure fluid-absent melting experiments in the presence of graphite: oxygen fugacity, ferric/ferrous ratio and dissolved CO2. Eur. J Mineral. 4, 105–114 (1992).

Médard, E., McCammon, C. A., Barr, J. A. & Grove, T. L. Oxygen fugacity, temperature reproducibility, and H2O contents of nominally anhydrous piston-cylinder experiments using graphite capsules. Am. Mineral. 93, 1838–1844 (2008).

Takahashi, E. & Kushiro, I. Melting of a dry peridotite at high pressures and basalt magma genesis. Am. Mineral. 68, 859–879 (1983).

Cone, K. A. 2021. ApolloBasalt DB_V2, Version Version 1.0. Interdisciplinary Earth Data Alliance (IEDA). https://doi.org/10.26022/IEDA/111982 (2021).

Su, B. et al. Fusible mantle cumulates trigger young mare volcanism on the cooling Moon. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn2013 (2022).

Kommescher, S. et al. Unravelling lunar mantle source processes via the Ti isotope composition of lunar basalts. Geochem. Perspect. Lett. 13, 13–18 (2020).

Singletary, S. & Grove, T. Origin of lunar high-titanium ultramafic glasses: A hybridized source? Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 268, 182–189 (2008).

Van Orman, J. A. & Grove, T. L. Origin of lunar high-titanium ultramafic glasses: constraints from phase relations and dissolution kinetics of clinopyroxene-ilmenite cumulates. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 35, 783–794 (2000).

Warren, P. H. & Wasson, J. T. The origin of KREEP. Rev. Geophys. 17, 73–88 (1979).

Ringwood, A. E. & Kesson, S. E. A dynamic model for mare basalt petrogenesis. Proc. Lunar Planet. Sci. Confer 6, 1697–1722 (1976).

Hallis, L. J., Anand, M. & Strekopytov, S. Trace-element modelling of mare basalt parental melts: Implications for a heterogeneous lunar mantle. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57, 289–316 (2014).

Münker, C. A high field strength element perspective on early lunar differentiation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 7340–7361 (2010).

Sprung, P., Kleine, T. & Scherer, E. E. Isotopic evidence for chondritic Lu/Hf and Sm/Nd of the Moon. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 380, 77–87 (2013).

Borg, L. & Gaffney, A. Complete melting of the Moon inferred from hafnium isotope measurements. Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3186398/v1 (2023).

Haupt, C. P. et al. Trace element partitioning in the lunar magma ocean: an experimental study. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 179, 45 (2024).

Elkins-Tanton, L. T., Hager, B. H. & Grove, T. L. Magmatic effects of the lunar late heavy bombardment. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 222, 17–27 (2004).

Ghods, A. & Arkani-Hamed, J. Impact-induced convection as the main mechanism for formation of lunar mare basalts. J. Geophys. Res. 112, E03005 (2007).

Solomon, S. C. Mare volcanism and lunar crustal structure. Proc. Lunar Planet. Sci. Confer 6, 1021–1042 (1975).

Wieczorek, M. A. & Phillips, R. J. The “Procellarum KREEP Terrane”: implications for mare volcanism and lunar evolution. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 105, 20417–20430 (2000).

Yu, S. et al. Long-lived lunar volcanism sustained by precession-driven core-mantle friction. Natl Sci. Rev. 11, nwad276 (2024).

Laneuville, M. et al. A long-lived lunar dynamo powered by core crystallization. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 401, 251–260 (2018).

Peale, S. J. & Cassen, P. Contribution of tidal dissipation to lunar thermal history. Icarus 36, 245–269 (1978).

Fogel, R. A. & Rutherford, M. J. Magmatic volatiles in primitive lunar glasses: I. FTIR and EPMA analyses of Apollo 15 green and yellow glasses and revision of the volatile-assisted fire-fountain theory. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 59, 201–215 (2015).

Rutherford, M. J., Head, J. W., Saal, A. E., Hauri, E. & Wilson, L. Model for the origin, ascent, and eruption of Lunar picritic magmas. Am. Mineral. 102, 2045–2053 (2017).

Srivastava, Y., Basu Sarbadhikari, A., Day, J. M. D., Yamaguchi, A. & Takenouchi, A. A changing thermal regime revealed from shallow to deep basalt source melting in the Moon. Nat. Commun. 13, 7594 (2022).

Korotev, R. L. Concentrations of radioactive elements in lunar materials. J. Geophys. Res. 103, 1691–1701 (1998).

McCubbin, F. M. et al. Magmatic volatiles (H, C, N, F, S, Cl) in the lunar mantle, crust, and regolith: abundances, distributions, processes, and reservoirs. Am. Mineral. 100, 1688–1707 (2015).

Su, X. & Zhang, Y. Volatiles in melt inclusions from lunar mare basalts: Bridging the gap in the H2O/Ce ratio between melt Inclusions in lunar pyroclastic sample 74220 and other mare samples. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 373, 232–244 (2024).

Zhang, Y. Review of melt inclusions in lunar rocks: constraints on melt and mantle composition and magmatic processes. Eur. J. Mineral. 36, 123–138 (2024).

Lin, Y., Hui, H., Li, Y., Xu, Y. & van Westrenen, W. A lunar hygrometer based on plagioclase-melt partitioning of water. Geochem. Perspect. Lett. 10, 14–19 (2019).

Xu, Y., Lin, Y., Zheng, H. & van Westrenen, W. Non-Henrian behavior of hydrogen in plagioclase – basaltic melt partitioning. Chem. Geol. 661, 122153 (2024).

Wetzel, D. T., Hauri, E. H., Saal, A. E. & Rutherford, M. J. Carbon content and degassing history of the lunar volcanic glasses. Nat. Geosci. 8, 755–758 (2015).

Rolf, T., Zhu, M. H., Wünnemann, K. & Werner, S. C. The role of impact bombardment history in lunar evolution. Icarus 286, 138–152 (2017).

Michael, P. J. Chemical differentiation of the cordillera paine granite (southern Chile) by in situ fractional crystallization. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 87, 179–195 (1984).

Bachmann, O. & Bergantz, G. The magma reservoirs that feed supereruptions. Elements 4, 17–21 (2008).

Siewert, R., Büttner, H. & Rosenhauer, M. Experimental investigation of thermodynamic melting properties in the system NaCl-KCl at pressures of up to 7000 bar. J. Mineral. Geochem. 172, 259–278 (1998).

McDade, P. et al. Pressure corrections for a selection of piston-cylinder cell assemblies. Mineral. Mag. 66, 1021–1028 (2002).

Green, T. H., Ringwood, A. E. & Major, A. Friction effects and pressure calibration in a piston-cylinder apparatus at high pressure and temperature. J. Geophys. Res. 71, 3589–3594 (1966).

Watson, E., Wark, D., Price, J. & Van Orman, J. Mapping the thermal structure of solid-media pressure assemblies. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 142, 640–652 (2002).

Moore, G., Roggensack, K. & Klonowski, S. A low-pressure-high-temperature technique for the piston-cylinder. Am. Mineral. 93, 48–52 (2008).

Jing, J.-J., Lin, Y., Knibbe, J. S. & van Westrenen, W. Garnet stability in the deep lunar mantle: Constraints on the physics and chemistry of the interior of the Moon. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 584, 117491 (2022).

Unruh, D. M., Stille, P., Patchett, P. J. & Tatsumoto, M. Lu-Hf and Sm-Nd evolution in lunar mare basalts. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 89, B459–B477 (1984).

Liu, B. & Liang, Y. An introduction of Markov chain Monte Carlo method to geochemical inverse problems: Reading melting parameters from REE abundances in abyssal peridotites. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 203, 216–234 (2017).

Smith, P. M. & Asimow, P. D. Adiabat_1ph: a new public front-end to the MELTS, pMELTS, and pHMELTS models. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 6, Q02004 (2005).

Steele, I. & Smith, J. Mineralogy of Apollo 15415 “genesis rock”: source of anorthosite on Moon. Nature 234, 138–140 (1971).

Donohue, P. H. & Neal, C. R. Textural and mineral chemical evidence for the cumulate origin and evolution of high-titanium basalt fragment 71597. Am. Mineral. 103, 284–297 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42250105) to Y.L., the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFF0807500) and the National Science Foundation of China (Grants No. U1530402 and U1930401) for Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research. S.G. thanks Kewei Shen, Junkai Li for suggestions on piston-cylinder experiments, Sheng Shang and Jiejun Jing for discussion on trace element modeling, and Chunyuan Lan for help on Monte-Carlo simulations. Discussions with Bernard Charlier are greatly appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. designed the project. S.G. performed the high-pressure and high-temperature experiments and modeled the results. S.G., Y.L. and W.v.W. discussed the results and prepared the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Cordula Haupt and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Ke Zhu and Joe Aslin. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, S., Lin, Y. & van Westrenen, W. Experimental evidence for a shallow cumulate remelting origin of lunar high-titanium mare basalts. Commun Earth Environ 6, 59 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02054-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02054-1