Abstract

The proliferation of pelagic Sargassum in the tropical Atlantic since 2011 is causing considerable health and economic concerns as large amounts of this brown alga arrive and accumulate in coastal ecosystems of western Africa and of the greater Caribbean Sea every year. Many hypotheses have been proposed to explain the recurrence of Sargassum blooms since 2011 and their year-to-year variability. Among the hypotheses being debated about the origin and nutrient source to support the blooms are either: a) an increase in nutrient supply to the Atlantic Ocean via continental, or atmospheric inputs, or b) long-distance transport of a seed population during the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) event of 2009/2010 and stimulation of blooms in the tropical North Atlantic by nutrient supply primarily due to seasonal vertical mixing of the upper water column. The aim of this study is to address these alternate hypotheses. To this end, interannual numerical simulations (2002-2022) representing the transport, growth, and decay of pelagic Sargassum have been developed at basin scale. Our results confirm the role played by the NAO transport anomaly on the regime shift that occurred in 2010, and the primary role of vertical mixing in the tropical Atlantic as the primary nutrient source for the recurring blooms since 2011.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

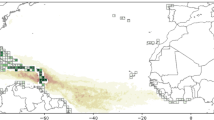

The Tropical Atlantic and the Caribbean Sea have seen massive annual blooms of pelagic Sargassum since 20111,2,3 (Fig. 1). This phenomenon has been the focus of particular attention from the scientific community and civil society at the international level, since the arrival and stranding of the alga has had economic and health consequences on coastal populations and ecosystems of the northern Tropical Atlantic.

Sargassum coverage obtained from MODIS AFAI in July 2021 (brown color scale; value between 0.001% and 0.2%) and surface chlorophyll distribution in July 2021 (green color scale; im mg m−3) from GlobColour merged monthly product. Circulation schematic of the surface currents is superimposed: the North Equatorial Current (NEC), the northern and southern branches of the South Equatorial Current (nSEC and sSEC), the North Equatorial Countercurrent (NECC), the North Brazil Current (NBC), the Caribbean Current (CC), and the Loop Current (LC). The blue contour represents the 9 mm/day precipitation iso-contour and is taken to indicate the ITCZ location.

The reasons behind this proliferation and annual recurrence since 2011 are still being debated. On the one hand, there is the hypothesis of extensive ocean fertilization by rivers or atmospheric inputs of nutrients2,4,5,6. Two independent studies, however, have suggested that riverine nutrient inputs play a minor role in the annual development of cross-basin pelagic Sargassum blooms and in the initial process of arrival of the alga in the tropical Atlantic7,8. The hypothesis that Saharan dust is the cause of the phenomenon has also been discounted because of lack of evidence of a connection2.

Johns et al.8 examined wind observations, drifting buoy tracks, numerical circulation model results, historical hydrographic and ocean nutrient profiles, and satellite bio-optical and cloud data to demonstrate that there were major anomalies in the circulation of the North Atlantic in 2009/2010 in response to an exceptionally strong (negative) North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) event. They advanced the hypothesis that these anomalous currents transported Sargassum from the subtropical North Atlantic gyre to the Central and Eastern Atlantic, and then south to the tropics, where the alga found a favorable environment for its proliferation. Historical oceanographic studies of the tropical equatorial North Atlantic have shown that there is seasonal vertical mixing and Ekman pumping due to the Trade Winds over a shallow nutricline8,9,10,11. These vertical movements lead to nutrient inputs to surface water and support phytoplankton blooms in the broader tropical Atlantic region9,10. The same nutrients are available to support the seasonal blooming of pelagic Sargassum.

The hypothesis of long-distance transport from the Sargasso Sea to the equatorial North Atlantic generally runs up against the criticism that there is no evidence of transport around 2010 in the historical time series of satellite images of Sargassum distribution assembled to date6. In that area, however, detecting Sargassum from space is difficult because of broad cloud cover, sunglint, and other problems that lead to substantial gaps in the Sargassum coverage satellite data record. So, it is not clear that a transport event could so far have been detected.

The lack of consensus on the causes and mechanisms controlling the seasonal and interannual variability of the blooming of pelagic Sargassum in the tropical central Atlantic translates into highly varied societal perceptions of its causes12. The idea that rivers, including the Amazon, Orinoco, Niger, Congo, and even relatively smaller rivers like the Mississippi are fueling the annual blooms in the tropical North Atlantic has become widespread even though there is no scientific evidence that any of these rivers are the cause for the blooms in the tropical Atlantic or at the scale of the entire North Atlantic Basin. Here we provide further evidence to clarify the causes of the recurring phenomenon of the Sargassum blooms in the tropical central North Atlantic Ocean.

Results

Modeling strategy

To unravel the dominant processes that led to the initial establishment of the Sargasso population in the tropical North Atlantic and the recurring Sargasso blooms, we chose to use large-scale and long-term numerical simulations of the Sargassum distribution. This framework allows us to test two hypotheses: 1) the strongly negative 2009–2010 NAO phase triggers long-distance southward transport of Sargassum; 2) this newly established population of Sargassum blooms every year due to seasonal nutrient supply by vertical mixing of the upper ocean and not due to land-derived nutrients input via rivers from North or South America, or Africa. Multi-year modeling of Sargassum requires accurate representation of the transport, growth, and decay properties of the algae. Simulations are based on advances of the Eulerian Sargassum model NEMO-Sarg which properly reproduces and forecasts the seasonal evolution of pelagic Sargassum at basin scale13,14.

The model represents pelagic Sargassum biomass through its carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P) uptake, release, and stock. The biomass is transported by surface currents, wind drift and diffusion. The model allows for variable biomass stoichiometry within the ranges observed5,6,15. Growth is limited by the N and P content of the tissues. Nutrient uptake depends on the concentration of macronutrients and micronutrients in the environment (NO3, PO4, NH4, Fe), temperature, and local wind (taken as a proxy for turbulence in the surface layers). A parameterization of diazotrophy is included16 since N fixation has been suggested as an important source of N for Sargassum17,18,19. Growth is also dependent on photosynthetically available radiation, temperature, and salinity20. The temperature dependence of the pelagic species (Sargassum Natans and Sargassum Fluitans) that make up the blooms has been the subject of numerous studies, with no consensus emerging on the optimal temperature and shape of the response curve20,21,22,23,24,25. Here, we hypothesize a generic morphotype with an optimal growth temperature between 26 and 28 °C, in line with several studies20,24.

The pelagic Sargassum growth and distribution model is forced using currents, temperature, and salinity from the GLORYS12 1/12° ocean reanalysis26. Solar radiation and surface wind are obtained from the ERA5 atmospheric reanalysis 27. The wind reanalysis product provides a realistic, time-varying surface ocean Trade Wind wind velocities, wind stress27, and surface convergence fields associated with the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). The biogeochemical fields (NO3, PO4, Fe, NH4) are obtained from a global NEMO-PISCES simulation at ¼° resolution28. This biogeochemical NEMO-PISCES simulation is forced using interannual atmospheric reanalysis and averaged climatologies for river inputs, atmospheric deposition of dust, and the vertical distribution of nutrients based on historical field observations (so they reflect seasonal variations only, see detailed description of this simulation in Method section). Sargassum simulations were initialized for January 1993 with a Sargassum content of 2.10−6 mgC m-2 (equivalent to a fractional cover of 1.10−5) in the Sargasso Sea only. Sargassum biomass was derived from C content by considering a mean carbon-to-wet-weight ratio of 6%29 and is compared to observed Sargassum cover by considering an average density of 3.34 kg m−2 for pure Sargassum patches30. The period 2002–2022 is analyzed since it allows direct comparison with MODIS satellite-derived detections. A detailed description of the Sargassum model is given in the Method section.

Drivers of the 2010/2011 tipping point

The seasonal distribution of Sargassum over the recent period is captured in the long-term simulation and is illustrated in Fig. 2. The peak coverage of Sargassum in the tropical North Atlantic occurs in May, June, and July, with Sargassum patches from the current and previous year together extending from 30°W to the Loop current in the Gulf of Mexico, as seen in both the model and observations. There is no evidence of large patches or amounts of pelagic Sargassum east of 10°W or south of the Equator. In October, November, and December, Sargassum quantities in the tropical Central Atlantic are considerably lower and concentrated in the central Tropical North Atlantic, mainly under the ITCZ, with a maximum near Sierra Leone. The maintenance of Sargassum in this region during boreal winter is a key factor for the development of the subsequent year’s bloom8.

a–d Seasonal cycle of Sargassum areal coverage (%) in the Tropical Atlantic computed using MODIS detections and model outputs from 2015 to 2022. The areal coverage is defined as the proportion of a pixel area occupied by Sargassum mats. Here the pixel area is ∼25 × 25 km. e Monthly mean time series of Sargassum biomass estimated from MODIS and obtained from a NEMO-Sarg simulation averaged from 100°W to 0°E and from 0°S to 30°N.

There is a difference between historical field observations and the remotely sensed Sargassum in the Sargasso Sea and more broadly in the North Atlantic gyre. The North Atlantic gyre is the natural historical habitat of pelagic Sargassum31. Pelagic Sargassum had been known to be characteristic of the North Atlantic gyre and less abundant but present in the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico as far back as C. Columbus32,33,34. Pelagic Sargassum was observed historically to be at concentrations estimated to be 15 to over 50 times lower in the Caribbean Sea compared to the Sargasso Sea32. Parr32 provides an extensive discussion of abundant Sargassum in the northern and northwestern Gulf of Mexico, where Sargassum was described as unhealthy and overgrown with epiphytes and epifauna (this is the area of dispersal of the Mississippi River plume).

Thus far, remote sensing has not always effective in detecting Sargassum in the Sargasso Sea (ref. 35 and Fig. S1). Remote sensing seems to miss an important fraction of the biomass there. It has already been proposed that there may be very large (10 to 100-fold) variations in the abundance of Sargassum over time in the Sargasso Sea33,36. Whether it is due to temporal variations in historical Sargassum observations or the difficulty of observing these patches at intermediate latitudes, it is not possible for us to know. Thus, our model results for the Sargasso Sea may overestimate Sargassum abundance compared to satellite-derived estimates.

The model does reproduce the regime shift that occurred in 2009–2010 and that led to the first pelagic Sargassum blooms in the tropical Atlantic in 2011 (see Fig. 2e and Supplementary Video 1). To analyze potential causes of the regime shift and the recurrence of larger blooms in the tropical central North Atlantic, we conducted sensitivity tests. The different runs included a reference simulation (EXP0) with all variables, a simulation with no interannual variability of the ocean surface currents (EXP1), one with only climatological nutrients taken from the 2000s decade (EXP2), one with no interannual variability of the sea surface temperature (EXP3), one with no nutrients in the Amazon plume area (EXP4), and one with no nutrients in the West Africa upwelling (EXP5). The resulting total biomass integrated over the area bound by 100°W to 0°E, 0°S to 30°N, is shown in Fig. 3.

Time evolution of the annual total biomass (in 106 tons) over the North Tropical Atlantic (total integrated over 100°W to 0°E, 0°S to 30°N), estimated from MODIS detections and obtained from a reference simulation (EXP0), and simulations with no interannual variability of the ocean surface currents (EXP1), climatological nutrients taken from the 2000s decade (EXP2), no interannual variability of the sea surface temperature (EXP3), no nutrients in the Amazon plume area (EXP4), and no nutrients in the West Africa upwelling (EXP5).

A simulation with no interannual variability of currents was not able to replicate the observed regime shift in 2009–2010 nor the annual Sargassum distribution patterns observed after 2011 in the Caribbean and Tropical Atlantic (EXP1 in Fig. 3). This is evidence of the role of the anomaly in the circulation that occurred just before 2011. In this experiment, the wind speed component was not filtered, so the interannual variability of the windage was not suppressed. Figure S2 (and Supplementary Video 1) shows that the pathway for the injection of North Atlantic Sargassum may have been the North Equatorial Current, while the retroreflection of the North Brazil Current and the North Equatorial Counter Current37,38,39 brought the Sargassum into the ITCZ region in the following months. This is in line with Lagrangian experiments8. The model likely underestimates the amount of Sargassum that reached the retroflection region in 2011 when compared to the satellite data record (Figs. S2 and S3). However, the timing of the regime shift is well represented, indicating that the model captured the fundamental process.

According to ref. 4 abnormally warm temperatures occurred in the north Tropical Atlantic in 2010/2011. This is another indication of an anomalous situation and may have contributed to the survival of Sargassum during its transport to the south. A forced simulation which excluded interannual variability of the SST (EXP3) replicated the regime shift, indicating that the SST anomaly by itself may have not played a crucial role in the tipping point. Since a very simple dependence on temperature is considered in our model, these findings are worth revisiting in the future in the light of an improved understanding of survival rates and temperature sensitivity of growth and mortality traits.

Finally, in order to investigate the effects of nutrient forcing on the system, a simulation was conducted using climatological nutrient data (NO3, PO4, Fe, NH4) from the 2000s decade instead of interannually varying nutrients. Seasonal variability of the nutrient surface concentrations was conserved, and this was done by taking the climatological average of the NEMO-PISCES outputs over this decade. The simulation demonstrates a shift in regime (see EXP2 in Fig. 3) despite no interannually varying nutrient forcing, suggesting that such a shift could occur and could be maintained without alterations of nutrient inputs over time.

Maintenance of the proliferation in the Sargassum belt

The reason for the higher growth rates in the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt (GASB) compared to the North Atlantic gyre (Figs. 4e, 5) is temperature, nutrient and light supply. The theory for the seasonal nutrient supply to surface waters in the Sargasso Sea and light limitation of phytoplankton growth was described by ref. 40 and many others. These processes also limit Sargassum growth. The Sargasso Sea has high winds, cold temperatures and low light in winter, compared to the tropical North Atlantic with favorable temperature, ample nutrient supply by vertical mixing and high light regime during January through April (Figs. 4 and 5). Phytoplankton, zooplankton, and Sargassum in the temperate North Atlantic gyre derive their nitrogen isotopic composition from underlying waters and the spatial and temporal variations in vertical mixing41,42. Both in model and observations, the maximum growth in the tropical North Atlantic occurs between January and April (Fig. 4e). At this time, the growth rate is particularly high in the western tropical Atlantic between the Lesser Antilles and the equator (Fig. 5). During the boreal summer, the surface waters of the North Atlantic typically become depleted in nutrients due to high stratification. Meanwhile, the newly grown mass of Sargassum is advected toward the Caribbean (Fig. S4a), and this new growth will reach the Gulf of Mexico toward the end of the year.

Seasonal cycle of Sargassum biomass (in 106 tons) and limitation functions average over the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre (a) and the Great Atlantic Sargassum belt region (d), computed from reference simulation over the period 2015–2022. The dashed lines in (b) and (e) show the biomass computed by applying a detection threshold on fractional cover of 10−4 on monthly averaged detection coarsened on a ¼° grid. Such threshold value is a rough estimation of MODIS detection limits at this temporal and spatial resolution. c, f show the time evolution of the limitation functions for temperature, light, and nutrient quotas averaged over the two regions.

Seasonal evolution of (a) Sargassum local change rate computed as growth minus decay rate (d−1), (b) temperature limitation function f(T), (c) solar radiation limitation function f(I), (d) nutrient content limitation function f(Q), (e) N2 fixation (mgN mgC−1) and f decay rate (d−1). Model outputs from 2015 to 2022 from the reference experiment EXP0 are used. The averages are performed over consecutive 2-month periods and start in Jan–Feb.

From the data presented in Fig. S4f (see also ref. 11), PO4, NO3, and NH4 concentrations are elevated just beneath the surface in the western Atlantic in the 0–15°N latitude range. These nutrients can be mixed upwards toward the surface by wind mixing and Ekman pumping, and thus fuel the high Sargassum growth rates observed in January–April. The biogeochemical model reveals that surface waters in this region indeed receive the majority of their phosphorus and nitrate from vertical mixing (Figs. S5 and S6), while horizontal processes contribute to extending the large phosphorus and nitrate concentration toward the Antilles and the central tropical Atlantic (Fig. S5 and S6). Atmospheric nitrogen fixation in the Sargassum model suggests that this source is also important in this region (Fig. 5e). Nitrogen fixation is favored by temperatures in this region (Fig. 5b) and sufficient phosphorus (Fig. S4e) and iron content in the surface waters. This may further alleviate nitrogen limitation for Sargassum growth, as suggested by several studies18,19.

The model indicates that the highest decay rates of Sargassum in the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico occur between August and October (Fig. 5f). This is due to thermal stress in response to elevated temperatures during the peak of the western Atlantic warm pool, which extends from the Gulf of Mexico to the eastern Caribbean during this period (Fig. S4b). Thus, it seems that production within the pelagic Sargassum mass slows down during this period even as the bloom enters the area and timing of extension of the Amazon and Orinoco river plumes toward the central and northern Caribbean Sea43,44.

In the subtropical North Atlantic gyre, the seasonality of Sargassum distribution (Fig. 4b) is different from that in the southeastern sector of the GASB where blooms initiate every year (Fig. 4e). In the North Atlantic gyre, growth peaks in boreal summer (July–August) and maximum Sargassum biomass occurs in Fall, in agreement with early remote sensing observations35. This is due to favorable surface temperatures, solar radiation (Fig. 4c) as well as high nutrient content due to vertical mixing (Figs. S5 and S6) in the northern part of the gyre above 30°N. Yet this growth in the North Atlantic gyre leads to lower biomass than observed in the GASB. The marked seasonal fluctuation in temperature and solar radiation in the North Atlantic restricts the conditions of favorable habitat compared to those in the tropical Atlantic (Figs. 4 and 5), where temperature and irradiance are favorable for pelagic Sargassum growth (eastern GASB) and biomass maintenance (western GASB) year-round (Fig. 4).

Discussion

This study presents results from a Sargassum transport-growth model based on the current understanding of the alga’s physiology and transport peculiarities. The model reproduces the hypothesized change in regime that occurred in 2009–2010 in the North Atlantic Ocean to set up the recurring blooms seen since 2011. There are many reports of physical oceanographic, meteorological, and ecological anomalies and shifts that happened in the North Atlantic around 201045,46,47,48,49,50,51. The expansion in the geographic range of pelagic Sargassum in the region is one more ecological process that changed at that time. The results of the model demonstrate the role of the anomalous currents in the subtropical North Atlantic in 2009–2010 in response to the negative NAO event and align with recent study by Johns et al.8 which highlighted abnormal transport from the subtropical gyre to the tropical central North Atlantic area.

The biogeochemical fields used to force the Sargassum model were obtained from modeling that include seasonal variations in river inputs and atmospheric deposition but do not include their interannual variations. Although their contribution to the biogeochemical cycles of the tropical Atlantic has long been the subject of research, our results show that their relevance on the ecological and physical regime shift of the North Atlantic in 2009–2010 was likely weak compared to those of the NAO event.

The analysis confirms that the conditions for growth in the tropical Atlantic are more favorable to pelagic Sargassum growth than those in the subtropical North Atlantic gyre. Further, the annual recurrence of Sargassum blooms in the tropical Atlantic from January to April in the western tropical Atlantic (Fig. 5a) is due to injections of high concentrations of phosphorus and nitrogen to surface waters from vertical mixing (Fig. S5). Nutrient inputs from the Amazon could also play a role during this period. This hypothesis has been already advanced2 but the most significant Sargassum growth occurs in areas outside the plume’s zone of influence (refs. 7,8 and this study). This view that the Amazon is not the primary driver of the regime shift is confirmed by a simulation in which the nutrient content of the Amazon plume is set to zero (EXP4), which suggests that the regime change could occur even without nutrients associated with the Amazon River (Fig. 3). This experiment shows a reduction in the amount of Sargassum biomass of the order of 15% compared to the reference simulation, which is in line with previous estimates7, that show that only 10% of the Sargassum biomass occurs over the year in regions under the influence of river plumes. The nutrient content (C:P and N:P ratio) of the Sargassum represented by the model (Fig. 6) is consistent with recent observations that show the GASB has a higher nitrogen and phosphorus content than populations living in the Sargasso Sea6. This reflects Sargassum taking up the nutrients that are available from whatever source is available and does not represent evidence of riverine inputs.

While some studies also suggest that increased West African upwelling could have stimulated sargassum blooms2, our model simulations did not show a clear link between upwelling and bloom intensity. To investigate this hypothesis, we conducted a sensitivity experiment where we removed nutrients from a region associated with upwelling influence (10°N-30°N, 20°W-coast). As shown in Fig. 3, this had minimal impact on Sargassum biomass, suggesting a weak link between upwelling and the regime shift or population maintenance in the GASB. The distance between the upwelling region and the primary bloom area might explain this minimal influence.

The model fails to replicate the interannual variations in pelagic Sargassum biomass seen in the satellite data record since 2011. The reasons for the model’s biases in certain years, such as its inability to accurately represent the decay of Sargassum in 2016 and 2019, have not been entirely determined. A coherence between the Atlantic Meridional Mode and the interannual variability of Sargassum has been suggested52, with cool temperature anomalies in the northern tropical Atlantic (2015, 2018) coinciding with peaks of biomass. However, this relationship did not hold in recent years (2020–2023) when temperatures were particularly warm and Sargassum cover was particularly high. We believe that part of the problem is that state of the art coupled physical-biogeochemical model at intermediate resolution such as the one we used to force the Sargassum model do not resolve vertical mixing and Ekman pumping well in the near-equatorial zone, and that we also have limited knowledge of the variability in the depth of the surface ocean stratification and depth of the nutricline in a North Atlantic Ocean that has continued to change rapidly since 2010.

The limited knowledge of the physiological response of the different morphotypes or the lack of knowledge of mortality factors (e.g. thermal stress, bacterial environment) might also help explain the difficulty we have in reproducing the interannual variability. Efforts must be made to improve the representation and understanding of nutrient cycles in the region of the GASB.

While this study confirms some findings on the role of the extreme NAO event from 2009/20108, one question that needs to be addressed is why NAO events in past decades or centuries did not lead to connection between the two regions. Unlike historical NAO minima, such as the record low of 1880/8153, this two-year event was distinctly associated with the “re-emergence” of SST anomalies from the winter of 2009/10 during early winter 2010/1154. While such occurrences are rare, weaker counterparts were documented in 1969/70 and 1978/7955. One hypothesis could be that a strong and persistent transport anomaly over two consecutive years of NAO minima may be required for Sargassum to successfully reach the tropics. Alternatively, recent climate change—potentially through rising SSTs—could have played a role in facilitating its survival during transit. Our modeling effort provides a foundation for tackling these questions.

The abrupt nature of Sargassum proliferation raises questions about its long-term trajectory. While it’s possible that this is a transient event, we cannot rule out the possibility of further expansion or shifts in distribution. While increased surface temperatures could be detrimental to Sargassum in the GASB56, it’s also conceivable that Sargassum could adapt to changing conditions and expand its range. Future research will be necessary to elucidate these possibilities.

Methods

Sargassum detection

The detection of holopelagic Sargassum is based on the Alternative Floating Algae Index (AFAI57) and MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) multispectral observations. The local deviation of the AFAI from the background signal is used to retrieve the area coverage of Sargassum, i.e. the fraction of MODIS pixels covered by Sargassum. Daily composites at 1 km resolutions are derived from MODIS-Terra and MODIS-Aqua snapshot acquisitions. The 1 km daily composites of areal coverage are then downscaled on a regular grid of 0.25°(∼25 km) horizontal resolution. This allows for a near-real time basin scale description of the Sargassum distribution in the Atlantic since the launch of MODIS in 200258.

Monthly averages of Sargassum areal coverage have been converted into wet-weight biomass considering an average density of 3.34 kg m−2, and then into carbon content C considering a mean carbon-to-wet-weight ratio of 6%29.

The Sargassum transport-physiology model

The Sargassum model relies on the strategy used to represent the distribution of other macroalgae species such as Ulva59,60 with the difference that here the algae is transported by a two-dimensional advection/diffusion/reaction model to take account of its pelagic nature. The model used in this study is an evolution of the NEMO-Sarg model13,14. Main differences include a parametrization of diazotrophy, revisited decay function, and include the negative influence of very low wind conditions on growth. The model parameters and the values used in this study are given in Table 1.

The physiological behavior is described from three state variables: the contents in carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P), with local variations reflecting the difference between uptake and loss rates.

where UC, UN, and UP are the uptake rates of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus respectively, and ΦC, ΦN, ΦP the loss rates, respectively.

The rate of carbon uptake reads as follows: \({U}_{c}=C\cdot {\mu }_{\max }\cdot f(T)\cdot f\left(S\right)\cdot f(I)\cdot f(Q)\cdot f(C)\), with \({\mu }_{\max }\) the maximum net carbon growth rate, and the five subsequent terms standing for uptake limitation by temperature (T), salinity (S) solar radiation (I), nutrient quota (Q), and Sargassum density represented by the carbon content (C) respectively.

The state variables are related between them through N and P quotas, which represent the ratios of nitrogen and phosphorus to carbon in the organism and are computed as N/C and P/C respectively.

The temperature dependence is as follows:

with \(\{{T}_{x}={T}_{\min }{for\; T}\le {T}_{{opt}};{T}_{x}={T}_{\max }{\, for\; T} > {T}_{{opt}}\}\). Such function aims at representing a limited temperature range favorable to growth as revealed from ex-situ cultures20,23,24.

A dependence on salinity is included in order to account for the negative impact of salinity on growth which has been observed for low salinities20 and for high salinities25. The salinity limitation f(S) read as:

with S the sea surface salinity.

The dependence on light is expressed in order to represent photoinhibition at high solar radiation20:

We have very little information on the response curve f(Q) relating the nutrient quota to Sargassum growth but experiments for brown seaweeds suggest a hyperbolic relationship61. So, the dependences on the internal nitrogen and phosphorus pools are computed as hyperbolic curves f(QN) and f(QP) controlled by the minimum and maximum cell quota:

The nitrogen and phosphorus uptake rates UN and UP depend on the nitrogen (VNmax) and phosphorus (VPmax) maximum uptake rates, a Monod kinetic that relates uptake to nutrient concentrations in the water, and a function of quota which aims at representing downregulation of the transport system for N and P when approaching the maximum quotas62:

QNmin and QPmin are the minimum N-quota and P-quota for carbon uptake, and QNmax and QPmax are the minimum N-quota and P-quota for carbon uptake.

VNfix is the nitrogen uptake due to N fixation and has been parameterized following development in biogeochemical model NEMO-PISCES16: it is restricted to warm waters (>20 °C) and is limited by the availability of light and iron and favored in low-nitrogen (NO3 and NH4) environments.

The nutrient uptake is limited at low wind speed as follows:

where Ws is the wind speed at 10 m. This term is motivated by experiments23 which showed that mesocosm studies with standing water led to rapid decay of Sargassum, whereas experimental setups in which thalli were kept in continuous motion at the water surface allow Sargassum to grow.

The growth limitation function \(f\left[C\right]\) is computed as

with Kc a half saturation constant. This term aims at representing growth limitation for large aggregations of Sargassum, because of limited access to light and nutrient resources.

The carbon loss aims at representing mortality and stranding:

In the absence of study on the mortality of pelagic Sargassum, with the exception of the possible role of Langmuir cells63,64, the mortality function was constructed empirically. It is computed as the sum of a constant background mortality mb and a quadratic mortality term mq. It is increased at high temperature by \({\alpha }_{T}\). Mortality is limited when light, temperature and solar radiation are favorable to growth.

The quadratic mortality mq is calculated as follows:

where αq is the quadratic mortality rate. This term represents density-dependent mortality factors, such as viral diseases or epiphyte accumulation.

The temperature-dependent mortality factor is calculated as follows:

\({\alpha }_{T}=\frac{1}{{e}^{-3(T-{Tm})}}\). It aims at representing thallus senescence and bacterial activity that could increase with temperature.

The stranding is a function of αgrnd which is a rate of Sargassum stranding per unit of time, and δland which is defined as follows:

Losses of nitrate and phosphate are function of the loss of biomass and internal N and P quotas:

The transport of C, N, and P is resolved using 2D advection/diffusion equations discretized on a grid at 1/4° resolution with a single vertical layer representing a surface layer of water of one-meter depth. The surface velocities used for the transport, account for surface currents plus the windage effect.

where (uo,vo) is the horizontal velocity vector obtained from daily outputs of ocean forecast, \({\alpha }_{{win}}\) is a windage coefficient, (u10m, v10m) the components of the wind field at 10m above the sea level, and Kh a diffusion coefficient.

Forcing the Sargassum model

Sargassum dynamics are computed on a regular ¼° grid from 15°S to 50°N and from 100°W to 15°E with a time step of 1200 s. Tracers are advected with the Monotone Upstream Scheme for Conservative Laws scheme and diffused with a Laplacian horizontal diffusion65.

The model is forced using daily currents, temperature and salinity from GLORYS12 ocean reanalysis26 interpolated at the model grid. GLORYS12 can be downloaded at https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/GLOBAL_MULTIYEAR_PHY_001_030/description.

Daily surface solar radiation and surface wind are obtained from ERA5 atmospheric reanalysis produced by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts66.

Seawater concentrations of [N], [P], and [Fe] are obtained from an interannual global physical-biogeochemical simulation at ¼°28, as the sum of NO3 and NH4 for [N], and PO4 for [P] in the upper surface layer. This “NEMO-PISCES” simulation is based on the ocean component of the high-resolution version of the earth system model developed by CNRM-CERFACS for the sixth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6). It uses the Nucleus for European Models of the Ocean (NEMO) Version 3.665 coupled to both the Global Experimental Leads and ice for ATmosphere and Ocean (GELATO) sea ice model Version 667 and the marine biogeochemical model Pelagic Interaction Scheme for Carbon and Ecosystem Studies version 2-gas (PISCESv2-gas)68. The ocean is run at a 0.25° of horizontal resolution with 75 vertical levels using a vertical z⋆ coordinate with partial step bathymetry formulation69. Ocean layers are distributed unevenly as a function of depth with a resolution of 1 m at ocean surface to 200 m below 4000 m, with 35 levels being in the first 300 m of depth. Details of the physical configuration are given in ref. 28. The simulation has been forced at the surface by the atmospheric state of JRA55-do v1.5.070. The global domain was first spun-up under preindustrial conditions over several hundred years, ensuring that all fields approached a quasi-steady state. To avoid the warming jump between the end of the spin-up and the onset of the reanalyses in 1958, the first 10 years of JRA55-do forcings were cycled 4 times from 1918 to 1958, and then the complete period of JRA55-do atmospheric forcing was used from 1958 to 2022. Atmospheric CO2 concentration is given as annual means as specified by CMIP6 protocols and is linearly interpolated in time. PISCESv2-gas uses several boundary conditions prescribed by climatologies, which represent the supply of nutrients from five different sources: atmospheric deposition, rivers, sediment mobilization, sea ice, and hydrothermal vents68,71. A revised parameterization of diazotrophy has been used16. In this configuration, iron supply from sea ice melting and hydrothermal vents have not been considered.

PISCESv2-gas uses different sources of initial conditions. Dissolved inorganic carbon and alkalinity are initialized using the modern climatology of the Global Ocean Data Analysis Project version 2 (GLODAPv272,73). Phosphate (PO4), silicate (Si), and nitrate (NO3) biogeochemical tracers are initialized from the 2013 World Ocean Atlas (WOA201311). Oxygen initial conditions are also obtained from WOA201374. Dissolved iron is not initialized from observations but from a previous model simulation68. The other biogeochemical tracers are initialized from global average estimates, as their initialization is less critical and equilibrates rapidly.

Nutrient budget

The three-dimensional PO4 budget solved in the “NEMO-PISCES” simulation reads as follows:

in which PO4 is the model phosphate concentration, (u, v, w) are the velocity components, Dl(PO4) is the lateral diffusion operator, and Kz is the vertical diffusion coefficient for tracers. The first three terms on the right-hand side are the zonal, meridional, and vertical advections; the fourth and fifth terms are the lateral and vertical diffusions. The last term, called “source minus sink” (SMS), is the phosphorus change rate due to biogeochemical processes, atmospheric deposition, and riverine inputs. The different terms are computed on-line at the model time step and averaged over one-month periods.

The different terms were computed for the last two years of the simulations, were integrated vertically from the surface to 5 m depth and averaged from January to April. On Figs. S5 and S6, they were grouped as HAD (XAD + YAD + LDF), which combine horizontal advection and diffusion, ZAD the vertical advection, ZDF the vertical diffusion, and SMS the “source minus sink”. The budget for NO3 is obtained and decomposed in the same way.

Initialization of the Sargassum model

The model is initialized in January 1993 with Sargassum coverage of 1e-5 in the western Atlantic (30°N-50°N) and the period 2002–2022 is analyzed. The initial N and P content in Sargassum is derived from the initial C content and N and P quotas are computed as the averaged values between their respective minimum values (QNmin, QPmin) and maximum values (QNmax, QPmax).

Set of simulations

Sensitivity tests were carried out to isolate the influence of the variability of certain parameters. The set of simulations generated is as follows:

-

EXP0 is the reference simulation described above,

-

EXP1 is a simulation forced with high-pass filtered surface currents and a cut-off period of 90 days. The seasonal cycle was previously filtered with a Lanczos harmonic analysis and then added to the filtered time series to conserve the seasonal cycle of the currents. It is worth noting that in this simulation the winds, and so on the windage, are kept interannual.

-

EXP2 is forced with climatological biogeochemical fields representative of the 2000s, obtained by averaging the results of the 1/4° NEMO-PISCES simulation over the period 2000–2009,

-

EXP3 is a forced simulation with a Lanczos high-pass filtered SST and a cut-off period of 90 days. The seasonal cycle was previously filtered with a Lanczos harmonic analysis and then added to the filtered time series to conserve the seasonal cycle of SST.

-

EXP4 is a simulation forced with no nutrients in the Amazon plume area. The Amazon plume area is delimitated at each time step by sea surface salinities below 35 in the region 60°W-30°W and 0°-20°N.

-

EXP5 is a simulation forced with no nutrients in Senegal-Mauritania upwelling. The is achieved by setting the nutrient concentrations at zero in the area between 20°W and the West Africa coast and between 10°N and 30°N.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The Sargassum surface coverage database was processed by AERIS/ICARE data center at the University of Lille58. The OISST sea surface temperature is available at https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/optimum-interpolation-sst75. The CCI+SSSv3.21 dataset is available at https://climate.esa.int/en/projects/sea-surface-salinity/76. The GLORYS12 simulations are available at Mercator Ocean International77.

References

Gower, J., Young, E. & King, S. Satellite images suggest a new Sargassum source region in 2011. Remote Sens. Lett. 4, 764–773 (2013).

Wang, M. et al. The great Atlantic Sargassum belt. Science 365, 83–87 (2019).

Gower, J. & King, S. The distribution of pelagic Sargassum observed with OLCI. Int. J. Remote Sens. 41, 5669–5679 (2020).

Djakouré, S., Araujo, M., Hounsou-Gbo, A., Noriega, C. & Bourlès, B. On the potential causes of the recent Pelagic Sargassum blooms events in the tropical North Atlantic Ocean. Biogeosci. Discuss. 2017, 1–20 (2017).

Lapointe, B. E. et al. Nutrient content and stoichiometry of pelagic Sargassum reflects increasing nitrogen availability in the Atlantic Basin. Nat. Commun. 12, 3060 (2021).

McGillicuddy, D. J. Jr et al. Nutrient and arsenic biogeochemistry of Sargassum in the western Atlantic. Nat. Commun. 14, 6205 (2023).

Jouanno, J, et al. Evolution of the riverine nutrient export to the Tropical Atlantic over the last 15 years: is there a link with Sargassum proliferation? Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 034042 (2021).

Johns, E. M. et al. The establishment of a pelagic Sargassum population in the tropical Atlantic: biological consequences of a basin-scale long distance dispersal event. Prog. Oceanogr. 182, 102269 (2020).

Signorini, S. R. et al. Biological and physical signatures in the tropical and subtropical Atlantic. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 104, 18367–18382 (1999).

McGillicuddy, D. J. Jr, Anderson, L. A., Doney, S. C. & Maltrud, M. E. Eddy-driven sources and sinks of nutrients in the upper ocean: results from a 0.1◦ resolution model of the North Atlantic. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 17, 1035 (2003).

Garcia, H. E., et al. World Ocean Atlas 2023. 2024. Volume 4: Dissolved Inorganic Nutrients (phosphate, nitrate, silicate). A. Mishonov, Tech. Ed. NOAA Atlas NESDIS 92, https://doi.org/10.25923/39qw-7j08.

Rosellón-Druker, J. et al. Local ecological knowledge and perception of the causes, impacts and effects of Sargassum massive influxes: a binational approach. Ecosyst. People 19, 2253317 (2023).

Jouanno, J, et al. A NEMO-based model of Sargassum distribution in the Tropical Atlantic: description of the model and sensitivity analysis (NEMO-Sarg1.0). Geoscientific Model. Development 14, 4069–4086 (2021).

Jouanno, J. et al. Skillful seasonal forecast of Sargassum proliferation in the Tropical Atlantic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105545 (2023).

Lapointe, B. E., West, L. E., Sutton, T. T. & Hu, C. Ryther revisited: Nutrient excretions by fishes enhance productivity of pelagic Sargassum in the western North Atlantic Ocean. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 458, 46–56 (2014).

Bopp, L. et al. Diazotrophy as a key driver of the response of marine net primary productivity to climate change. Biogeosciences 19, 4267–4285 (2022).

Carpenter, E. J. & Cox, J. L. Production of pelagic Sargassum and a blue-green epiphyte in the western Sargasso Sea 1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 19, 429–436 (1974).

Phlips, E. J., Willis, M. & Verchick, A. Aspects of nitrogen fixation in Sargassum communities off the coast of Florida. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 102, 99–119 (1986).

Léger-Pigout, M. et al. Predominant heterotrophic diazotrophic bacteria are involved in Sargassum proliferation in the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt. ISME J. 18, wrad026 (2024).

Hanisak, M. D., and Samuel, M. A.: Growth rates in culture of several species of Sargassum from Florida, USA. In Proc. Twelfth International Seaweed Symposium (pp. 399–404). Springer, Dordrecht, 1987.

Changeux, T. et al. Variability in growth and tissue composition (CNP, natural isotopes) of the three morphotypes of holopelagic Sargassum. Aquat. Bot. 187, 103644 (2023).

Corbin, M. & Oxenford, H. A. Assessing growth of pelagic Sargassum in the Tropical Atlantic. Aquat. Bot. 187, 103654 (2023).

Magaña-Gallegos, E. et al. Growth rates of pelagic Sargassum species in the Mexican Caribbean. Aquat. Bot. 185, 103614 (2023).

Magaña-Gallegos, E. et al. The effect of temperature on the growth of holopelagic Sargassum species. Phycology 3, 138–146 (2023).

Schell, J. M., Goodwin, D. S., Volk, R. H. & Siuda, A. N. Preliminary explorations of environmental tolerances and growth rates of holopelagic Sargassum morphotypes. Aquat. Bot. 190, 103723 (2024).

Lellouche, J.-M. et al. The Copernicus Global 1/12° Oceanic and Sea Ice GLORYS12 Reanalysis. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 698876 (2021).

Belmonte Rivas, M. & Stoffelen, A. Characterizing ERA-Interim and ERA5 surface wind biases using ASCAT. Ocean Sci. 15, 831–852 (2019).

Berthet, S. et al. Evaluation of an online grid-coarsening algorithm in a global eddy-admitting ocean biogeochemical model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 1759–1783 (2019).

Hu, C., Wang, M., Lapointe, B. E., Brewton, R. A. & Hernandez, F. J. On the Atlantic pelagic Sargassum’s role in carbon fixation and sequestration. Sci. Total Environ. 781, 146801 (2021).

Wang, M., et al. Remote sensing of Sargassum biomass, nutrients, and pigments. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 12359–12367 (2018).

Goodwin, D. S., Siuda, A. N. & Schell, J. M. In situ observation of holopelagic Sargassum distribution and aggregation state across the entire North Atlantic from 2011 to 2020. PeerJ 10, e14079 (2022).

Parr, A. E. Quantitative observations on the pelagic Sargassum vegetation of the western North Atlantic. Bull. Bingham Oceanogr. Collect. 6, 1–94 (1939).

Butler, J. N. & Stoner, A. W. Pelagic Sargassum: has its biomass changed in the last 50 years? Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanogr. Res. Pap. ume 31, 1259–1264 (1984).

Butler, J. N., Morris, B. F. Cadwallader, J. and Stoner, A. W. Studies of Sargassum and the Sargassum community. Special Publication No. 22, 307 (Bermuda Biological Station for Research, 1983).

Gower, J., & King, S. Satellite images show the movement of floating Sargassum in the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean. Nat. Proc., 1–1 (2008).

Stoner, A. W. Pelagic Sargassum: evidence for a major decrease in biomass. Deep-Sea Res. 30, 469–474 (1983).

Muller-Karger, F. E., McClain, C. R. & Richardson, P. L. The dispersal of the Amazon’s water. Nature 333, 56–59 (1988).

Muller-Karger, F. E., Richardson, P. L. & McGillicuddy, D. On the offshore dispersal of the Amazon’s Plume in the North Atlantic. Deep-Sea Res. I 42, 2127–2137 (1995).

Stramma, L. & Schott, F. The mean flow field of the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 46, 279–303 (1999).

Menzel, D. W. & Ryther, J. H. Annual variations in primary production of the Sargasso Sea off Bermuda. Deep-Sea Res. I 7, 282–288 (1961).

Knapp, A. N., Sigman, D. M. & Lipschultz, F. N isotopic composition of dissolved organic nitrogen and nitrate at the Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study site. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 19, GB1018 (2005).

Espinasse, B. et al. Temporal dynamics in zooplankton δ13C and δ15N isoscapes for the North Atlantic Ocean: Decadal cycles, seasonality, and implications for predator ecology. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.986082 (2022).

Muller-Karger, F. E., McClain, C. R., Fisher, T. R., Esaias, W. E. & Varela, R. Pigment distribution in the Caribbean Sea: observations from space. Prog. Oceanogr. 23, 23–69 (1989).

Muller-Karger, F. E., and R. Aparicio. (1994) Mesoscale processes affecting phytoplankton abundance in the Southern Caribbean Sea. Cont. Shelf Res. 14, 199–221 (1994).

Wang, C., Liu, H. & Lee, S.-K. The record-breaking cold temperatures during the winter of 2009/2010 in the Northern Hemisphere. Atmosph. Sci. Lett. 11, 161–168 (2010).

Osborn, T. T. Winter 2009/2010 temperatures and record-breaking North Atlantic Oscillation Index. Weather 66, 19–21 (2011).

Alexander, M. A., Kilbourne, K. H. & Nye, J. A. Climate variability during warm and cold phases of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) 1871-2008. J. Mar. Syst. 133, 14–26 (2014).

Maidens, A. et al. The influence of surface forcings on prediction of the North Atlantic Oscillation regime of winter 2010/11. Month. Weather Rev. 141, 3801–3813 (2013).

Taylor, G. T. et al. Ecosystem responses in the southern Caribbean Sea to global climate change. PNAS 109, 19315–19320 (2012).

McCarthy, G. D. et al. Measuring the Atlantic Meridional Overturning circulation at 26°N. Prog. Oceanogr. 130, 91–111 (2015).

Nye, JanetA. et al. Ecosystem effects of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. J. Mar. Syst. 133, 103–116 (2014).

Skliris, N., Marsh, R., Appeaning Addo, K. & Oxenford, H. Physical drivers of pelagic Sargassum bloom interannual variability in the Central West Atlantic over 2010–2020. Ocean Dyn. 72, 383–404 (2022).

Marsh, R. et al. The 1882 tilefish kill - a cold event in shelf waters off the north-eastern United States. Fish. Oceanogr. 8, 39–49 (1999).

Taws, S. L., Marsh, R., Wells, N. C. & Hirschi, J. Re-emerging ocean temperature anomalies in late-2010 associated with a repeat negative NAO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L20601 (2011).

Blaker, A. et al. Historical analogues of the recent extreme minima observed in the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation at 26°N. Clim. Dyn. 44, 457–473 (2015).

Marsh, R. et al. Climate-sargassum interactions across scales in the tropical Atlantic. PLOS Clim. 2, e0000253 (2023).

Wang, M. & Hu, C. Mapping and quantifying Sargassum distribution and coverage in the Central Western Atlantic using MODIS observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 183, 350–367 (2016).

Berline L., and Descloitres J. Cartes de répartition des couvertures de Sargasses dérivées de MODIS sur l’Atlantique. AERIS/ICARE - CNES/TOSCA. (2021) [Dataset] https://doi.org/10.12770/8fe1cdcb-f4ea-4c81-8543-50f0b39b4eca (accessed on 01 FEV 2023).

Ménesguen, A., Cugier, P. & Leblond, I. A new numerical technique for tracking chemical species in a mul-tisource, coastal ecosystem, applied to nitrogen-causing Ulva blooms in the Bay of Brest (France). Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 591–601 (2006).

Solidoro, C., Pecenik, G., Pastres, R., Franco, D. & Dejak, C. Modelling macroalgae (Ulva rigida) in the Venice lagoon: Model structure identification and first parameters estimation. Ecol. Model. 94, 191–206 (1997).

Hanisak, M. D.: The nitrogen relationship of marine macroalgae. In: ed. E. J. Carpenter and D. G. Capone, Nitrogen in the Marine Envinroment. 699–730 (Academic Press, 1983).

Lehman, J. T., Botkin, D. B. & Likens, G. E. The assumptions and rationales of a computer model of phytoplankton population dynamics. Limnol. Oceanogr. 20, 343364 (1975).

Johnson, D. L. & Richardson, P. L. On the wind-induced sinking of Sargassum. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 28, 255–267 (1977).

Woodcock, A. H. Winds subsurface pelagic Sargassum and Langmuir circulations. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 170, 117–125 (1993).

Madec, G. and the NEMO System Team (2023). NEMO Ocean Engine Reference Manual, Zenodo, [Software]: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8167700 (last accessed 01 APR 2023).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Salas, Y. & Mélia, D. A global coupled sea ice-ocean model. Ocean Model. 4, 137–172 (2002).

Aumont, O., Ethé, C., Tagliabue, A., Bopp, L. & Gehlen, M. PISCES-v2: An ocean biogeochemical model for carbon and ecosystem studies. Geosci. Model Dev. 8, 2465–2513 (2015).

Barnier, B. et al. Impact of partial steps and momentum advection schemes in a global ocean circulation model at eddy-permitting resolution. Ocean Dyn. 56, 543–567 (2006).

Tsujino, H. et al. JRA-55-based surface dataset for driving ocean-sea-ice models (JRA55-do). Ocean Model. 130, 79–139 (2018).

Séférian, R., et al. Evaluation of CNRM Earth-System model, CNRM-ESM2-1: role of Earth system processes in present-day and future climate. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst., 11. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS001791 (2019).

Key, R. M., et al. Global Ocean Data Analysis Project, Version 2 (GLODAPv2), ORNL/CDIAC-162, ND-P093. Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, US- Department of Energy, Oak Ridge, Tennessee. https://doi.org/10.3334/CDIAC/OTG.NDP093_GLODAPv2 (2015).

Lauvset, S. K. et al. A new global interior ocean mapped climatology: The 1°x1° GLODAP version 2. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 8, 325–340 (2016).

Garcia, H. E., et al. (2014a). World Ocean Atlas 2013, Volume 3: Dissolved Oxygen, Apparent Oxygen Utilization, and Oxygen Saturation. S. Levitus, Ed., A. Mishonov Technical Ed.; NOAA Atlas NESDIS 75, 27 pp.

Huang, B. et al. Improvements of the Daily Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (DOISST) Version 2.1. J. Clim. 34, 2923–2939 (2021).

Boutin, J. & Coauthors Satellite-based sea surface salinity designed for ocean and climate studies. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 126, e2021JC017676 (2021).

Mercator Ocean International Operational analysis and forecast system (01/01/2009-> now) of the Global Ocean biogeochemistry with data assimilation with a weekly update of the ocean fields. [Dataset]: https://www.mercator-ocean.eu/en/solutions-expertise/accessing-digital-data/ (last accessed 1 MAR 2023)(2023).

Jouanno J., Benshila R. Sargassum distribution model based on the NEMO ocean modelling platform (0.0). Zenodo. [software]: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4275900 (last access 01/14/2025). (2025).

Lapointe, B. E. A comparison of nutrient-limited productivity in Sargassum natans from neritic vs. oceanic waters of the western North Atlantic Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 40 (1995).

Berline, L. et al. Hindcasting the 2017 dispersal of Sargassum algae in the Tropical North Atlantic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 158, 111431 (2020).

Putman, N. F., Lumpkin, R., Olascoaga, M. J., Trinanes, J. & Goni, G. J. Improving transport predictions of pelagic Sargassum. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 529, 151398 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the ANR, through project FORESEA (https://sargassum-foresea.cnrs.fr; ANR-19-SARG-0007) and CNES, through project TOSCA SARGAT. Computing resources are provided by DARI under grant GEN7298. Frank Muller-Karger was supported by the Marine Biodiversity Observation Network (MBON) (NASA grants NNX14AP62A, 80NSSC20K0017, and 80NSSC22K1779; NOAA IOOS grant NA19NOS0120199; NOAA Climate Program Office grant NA22OAR4310561; and Gulf of Mexico Coastal Ocean Observing System GCOOS/IOOS Cooperative Agreement NA16NOS0120018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.J. designed the study, developed the model, analyzed the main results and led the writing of the paper. S.B. carried out the NEMO-PISCES biogeochemical simulations. S.B., F.M.K., O.A., and J.S. contributed to discussing the results, editing, and writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Nikolaos Skliris, Lorna Veronica Inniss, and Robert Marsh for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Ilka Peeken, Alice Drinkwater, Heike Langenberg. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jouanno, J., Berthet, S., Muller-Karger, F. et al. An extreme North Atlantic Oscillation event drove the pelagic Sargassum tipping point. Commun Earth Environ 6, 95 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02074-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02074-x

This article is cited by

-

Abrupt trend change in global mean sea level and its components in the early 2010s

Communications Earth & Environment (2026)

-

Dramatic decline of Sargassum in the north Sargasso Sea since 2015

Nature Geoscience (2025)

-

Socio-ecological vulnerability assessment to Sargassum arrivals

Scientific Reports (2025)