Abstract

Extreme warm ocean temperature events, known as marine heatwaves, have been associated with several coral bleaching reports in coastal locations of the Red Sea. Yet, our knowledge of the processes driving these events remains limited. Here we analyse the upper ocean mechanisms behind multiple summer marine heatwaves between 2001 and 2015, over known coral bleaching-affected regions, using a high-resolution ocean model, specifically tuned for the Red Sea. Our findings indicate atmospheric forcing as the primary driver of marine heatwave onsets in the northeast and southwest, while horizontal advection plays a key role in the southeast and northwest coasts. While the frequency and associated temperature changes of the events’ main drivers are subject to regional influences, the intensity and duration of extreme warming due to horizontal advection, on average, exceed that of atmosphere heat fluxes, which act as the major cooling mechanism across the majority of study areas. Ecological threats for Red Sea corals are further highlighted with a view to enhance our understanding of their response to climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coral reefs host exceptional biodiversity, providing essential ecosystem services to the vast populations living in tropical areas1. In the case of the Red Sea, coral reefs extend all around the basin’s coastlines and host a high level of species endemism2. However, coral bleaching, which describes the ejection or death of a coral’s symbiotic algae by the coral host, has led to devastating impacts on coral reefs3. The principal cause of coral bleaching globally is prolonged exposure to anomalously warm water temperatures4, particularly due to marine heatwaves (MHWs). The increasing frequency and intensity of these extreme events pose a significant threat to the health of these ecosystems on a global scale, exacerbating the effects of global warming and further accelerating their decline5,6. While MHWs are often defined with a 90th percentile threshold and a minimum duration of 5 days, in the Red Sea coral bleaching has been linked to MHWs characterized by temperatures exceeding the 95th percentile and lasting at least 7 days7. While the mean maximum annual temperatures range from 27 °C in the north to 33 °C in the south 8, bleaching has been observed only during MHWs with a mean temperature of 30 °C or more over the whole Red Sea7. In particular, the northern Red Sea has experienced mild (<10% coral cover) bleaching events so far9, while moderate (<30%) and severe (>50%) bleaching has been observed in the north-central and south-central Red Sea in 1998, 2010 and 201510,11,12,13. These events coincide with an abrupt warming seen throughout the basin14, that has also led to an increase in the frequency, duration and severity of MHWs over the past few decades15, particularly in the northern Red Sea, which is the region exhibiting the highest warming rate8.

Aside from coral bleaching, MHWs may result in decreased coral growth rates and could lead to Red Sea corals halting growth altogether by 2070, if temperatures continue to rise16. Despite an influence from the natural, 70-year long Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation on the sea surface temperature (SST) increase observed thus far17, the overall temperature trend in the basin since 1870 is positive and SSTs are anticipated to show new extremes in the future17. In particular, projections from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) estimate a 3 °C increase by 2100 for the whole Red Sea, meaning that central and southern Red Sea regions may encounter mass bleaching yearly, while the northern Red Sea mean temperatures will not reach the severe bleaching threshold until the end of the century18. Assessment of Red Sea temperatures based on the CMIP models further suggests an increase in the average MHW duration (up to 15 times) and intensity (~4 times) compared to the present conditions19.

Yet, our insight into the physical drivers behind MHWs in the Red Sea is limited to specific events. The coral reefs at the northern part of the basin (Gulf of Aqaba) experienced widespread warming during July 2017, attributed to lower than normal wind speed and latent heat losses from the ocean20. Likewise, extreme SST events observed in the southern part of the basin between 1982 and 2019 were related to reduced heat losses from the ocean, as a result of weaker winds associated with lower than normal sea level pressure established over the Red Sea and the surrounding area and a subsequent intrusion of warm air masses through the Tokar Gap21. Severe bleaching events linked to weak winds were also observed in 2010, near Thuwal, Saudi Arabia11,22 (from mid-July to September), in addition to a strong MHW in the northern Red Sea that was linked to high air temperatures, reduced ocean heat losses and weak winds15. However, processes other than atmospheric ones can drive SST variations within the mixed layer (ML), the near-surface layer of the ocean where temperature and salinity of the water remain nearly uniform23.

Here, we focus on the development phase of summer MHWs in the Red Sea (the main coral bleaching period in the basin) by isolating thermal effects of atmospheric forcing, oceanic advection and ML interactions with deeper layers, on the ML temperatures and examining their spatial distribution. In particular, we analyze the heat sources and sinks of multiple summer events between 2001 and 2015, by analyzing a mixed layer heat budget (MLHB) based on a simulation of a regional, high-resolution ocean model of the Red Sea24. To our knowledge, this is the first time that integrated information on the upper ocean from a MLHB simulation is used, instead of the SST variability, to explore the generating factors behind Red Sea MHWs. We provide a statistical overview of cumulative temperature changes during MHW onsets and subsequently present the dominant drivers during the onset phase. We further statistically link MHW onset drivers to total event duration in distinct bleaching-affected regions of the basin, discussing their potential impacts on marine ecosystems and corals in the Red Sea.

Results

Temperature tendency during MHW onsets

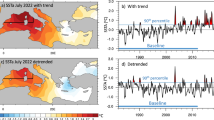

To gain an insight on the average extreme warm temperature conditions in the Red Sea, we first examine the cumulative positive and negative, daily temperature changes (or total warming and cooling budgets, see Methods) across an ensemble of MHW onsets (2001–2015) within every study area. On average, higher cumulative warming of the mixed layer temperature (MLT), ranging between 1 °C and 1.6 °C, is revealed in the northern Red Sea (Sharm El Sheikh, Hurghada and Al Wajh), compared to the central (0.5 °C–0.8 °C) and the southern (0.6 °C–0.8 °C) parts of the basin (Fig. 1b). Using the rate of onset (Ronset) index, we analyze the speed at which these temperatures change between the start of a MHW and the day of its peak intensity and find that the highest Ronset values are also seen in the northern areas of Sharm El Sheikh, Hurghada, Al Wajh and Wadi el Gemal (0.13 °C/day–0.15 °C/day). All other regions exhibit Ronset of about 0.06–0.09 °C/day, with the north-central study areas being around 0.1 °C/day (Fig. 1c). The Sharm El Sheikh, Hurghada and Al Wajh demonstrate in addition the highest cooling temperatures, of about 0.4 °C–1 °C, which work against but are not strong enough to entirely counteract MHW onsets, while all other study areas display cooling of approximately 0.1 °C–0.3°C (Fig. 1b).

a Selected study areas of the Red Sea, where coral bleaching has been reported, between 2001 and 2015. Red dots indicate the coral bleaching spots within each site, according to Genevier et al.7. b Cumulative sum of daily temperature change averaged over summer MHW onsets for each region. Total positive temperature changes are indicated in red (warming) and negative ones in blue (cooling). c Average rate of summer MHW onset (see Hobday et al.60 for details of the Ronset calculation). Note, the temperature changes shown here represent an average over all the events identified separately from all the grid-points of a study area. Additionally, regions are ordered descending from north to south, while those in the west (east) of the Red Sea are indicated in black (blue) labels. Colours on the main map represent the bathymetric characteristics of the basin. Red lines separate the Red Sea into the north, central and south part of the basin.

Dominant drivers of MHW onset

MHWs develop due to a combination of physical processes and knowledge of the main mechanism behind their onset is useful for predicting their most likely occurrence in every area. In this study, we analyze the contributions from atmosphere heat fluxes (AHflux), horizontal advection of temperature (Hadv), processes at the base of the mixed layer (MLBot) and mixing (Mixing) to the development of MHWs. First, we describe changes in MLT throughout multiple summer MHW onsets of 2001–2015 and then outline the probability of each MLHB process dominating these changes across the 12 study areas (see Methods). This probability is expressed in the form of a percentage, indicating the number of times a physical process was the main driver of summer MHW onsets, relative to the total number of summer events detected in each grid point of every study area over the examined period. In the following we describe differences in the distribution of the dominant physical processes, related to regional characteristics.

During MHW onset, average MLT changes are most pronounced in the northwest (Sharm El Sheikh, Al Wajh, Wadi El Gemal and Hurghada) and southeastern regions (Al Lith and Farasan) of the Red Sea, with temperature increases ranging from 0.17 to 0.33 °C (Fig. 2). The remaining study areas exhibit MLT changes between 0.12 and 0.16 °C. Maximum temperature increases are observed in specific locations, ranging from 0.29 to 0.45 °C along the western and from 0.33 to 0.94 °C along the eastern coasts, with Al Wajh showing the highest MLT increase (Fig. 2).

Total Mixed layer temperature change (Tot) averaged over all summer MHW onsets between 2001 and 2015. Colours on the main map represent the bathymetric characteristics of the basin. Note that limits in the colorbars vary between study areas to better visualise differences in the spatial distribution of Tot.

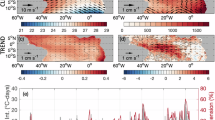

On average (over space), AHflux seem to dominate only 1%–19% of summer MHW onsets in the northwest regions of Sharm El Sheikh, Hurghada, Wadi El Gemal, as well as Farasan in the southeast. In all other study areas, AHflux is the dominant heat contributor in 23%–49% of the events, on average, with the highest percentage (49%) found in the Yanbu (Fig. 3). However, all regions show specific locations where 100% of MHWs are AHflux-driven, except for Sharm El Sheikh, Hurghada and Wadi El Gemal, where AHflux accounts for a maximum of 50% to 67% of the onsets locally. The highest percentage of events driven primarily by Hadv between 2001 and 2015 appears, on average, in the northwestern Red Sea: Sharm El Sheikh (92%), Hurghada (97%), Wadi El Gemal (83%), Southern Egypt (67%) and Farasan (66%) and Al Khawkhah (69%) in the south. In comparison, this process is on average, the main mechanism of 41%–60% of the events in all other areas, with Al Wajh exhibiting the lowest probability of Hadv-driven MHWs (~41%). Nonetheless, every study region demonstrates specific locations where Hadv dominates 100% of the events (Fig. 4).

Frequency of atmosphere heat flux-dominated (AHflux) events during summer MHW onsets, relative to the total number of summer events detected locally in each study area of the Red Sea, between 2001 and 2005. Note that the main, local MHW onset driver (maximum positive heat contribution) is calculated relative to the total warm contribution budget of each local MHW onset period. Colours on the main map represent the bathymetric characteristics of the basin.

Frequency of Horizontal advection-dominated (Hadv) events during summer MHW onsets, relative to the total number of summer events detected locally in each study area of the Red Sea, between 2001 and 2005. Note that the main, local MHW onset driver (maximum positive heat contribution) is calculated relative to the total warm contribution budget of each local MHW onset period. Colours on the main map represent the bathymetric characteristics of the basin.

The transfer of anomalously warm heat content within the ML through interactions with underlying water masses represented by MLBot processes dominates, on average, between 1% and 10% of MHW onsets in all study areas, with the northwestern regions showing the lowest probability of this MHW type (Hurghada ~1.3%, Wadi El Gemal 2.4% and Sharm El Sheikh ~3.5%) and Sanganeb the highest probability (10%). However, at specific locations, MLBot processes account for up to 40% of summer MHW onsets in Wadi El Gemal and up to 100% in Al Lith, Farasan, Al Khawkhah, Massawa Dahlak and Sanganeb (Fig. 5). Finally, mixing processes occasionally dominate the onset of summer MHWs, accounting for an average of 0.2% to 13% of the events. These types of events tend to occur near the coast or in shallow regions (Fig. 6), with the highest average frequency seen in Al Lith (4%), Farasan (10%) and Massawa Dahlak (13%). Specific locations in Yanbu, Thuwal Rabigh, Al Lith, Farasan and Al Khawhah exhibit 100% of Mixing-driven MHW onsets during the examined period. All other areas show a maximum frequency of 50%–87% for these events at a local scale.

Frequency of events dominated by processes at the base of the mixed layer (MLBot) during summer MHW onsets, relative to the total number of summer events detected locally in each study area of the Red Sea, between 2001 and 2005. Note that the main, local MHW onset driver (maximum positive heat contribution) is calculated relative to the total warm contribution budget of each local MHW onset period. Colours on the main map represent the bathymetric characteristics of the basin.

Frequency of mixing-dominated (Mixing) events during summer MHW onsets, relative to the total number of summer events detected locally in each study area of the Red Sea, between 2001 and 2005. Note that the main, local MHW onset driver (maximum positive heat contribution) is calculated relative to the total warm contribution budget of each local MHW onset period. Colours on the main map represent the bathymetric characteristics of the basin.

Warming and cooling associated with MHW onset drivers

The MLT can rise due to AHflux warming, mostly in the shallow or well-stratified ocean, and due to ocean currents (Hadv) transporting warmer waters. MLBot processes can also lead to warmer temperatures, typically by reducing the vertical extent of the ML, consequently distributing heat within a smaller volume. Alternatively, enhanced stratification resulting from reduced mixing in the ocean facilitates warming of surface layers. Conversely, these four processes can act to cool the upper ocean through turbulent or increased latent heat fluxes from the ocean to the atmosphere, cold water intrusions, or mixing with cooler waters below the ML. To gain further insight into the mechanisms conducive to a MHW in the Red Sea, we examine the warming and cooling contributions from the different physical processes during their onset period (Fig. 7).

Average cumulative warming and cooling of MLT due to AHflux (red), Hadv (blue), MLBot (green) and Mixing (purple) during summer MHW onsets. The total MLT trend throughout MHW onset is indicated in black (Tot). Note that cumulative temperature increase or decrease is averaged over the ensemble of events from all the grid points in every study area of the Red Sea, between 2001 and 2015. Colours on the main map represent the bathymetric characteristics of the basin.

The northwest study areas of Hurghada, Sharm El Sheikh and Al Wajh exhibit, on average, the highest total temperature changes during the examined summer MHW onsets, ranging from 0.58°C to 1.02°C. The remaining areas show MLT changes between 0.36°C and 0.53°C (Fig. 7). Our analysis indicates Hadv as the predominant mechanism behind this warming in most study areas, with average cumulative temperature changes between 0.7°C and 1°C in the northern areas of Sharm El Sheikh, Al Wajh and Hurghada and between 0.3°C and 0.6°C in all other regions (Fig. 7). Cumulative warming due to AHflux tends to be slightly lower, ranging between 0.16°C and 0.36°C everywhere, except in Al Wajh (1°C) and Yanbu (0.4°C). Warming from MLBot processes shows a similar tendency (0.08 °C–0.27 °C), with higher values observed in Al Wajh (0.27°C). The lowest warming contribution comes from Mixing, ranging between 0.05°C and 0.13°C in the western and between 0.07°C and 0.35°C in the eastern areas. Maximum values are seen in Al Lith and Farasan (0.28°C, 0.35°C).

During the onset of summer MHWs, multiple cooling mechanisms operate simultaneously. The AHflux plays a significant cooling role in the majority of regions and reduces the cumulative temperature by 0.18°C–0.35°C, on average, with the strongest reduction observed in Al Wajh (−0.96°C) and Hurghada (−0.51°C). Cooling due to Hadv is slightly lower, ranging between −0.08°C and 0.17°C, with Al Wajh experiencing the strongest cooling (−0.6°C). MLBot processes decrease MLT by a minimum of −0.05°C (Al Khawkhah, Wadi El Gemal) to a maximum of −0.4°C (Al Wajh) (Fig. 8). The cooling effect associated with Mixing is more pronounced in the eastern areas, ranging from −0.08°C to −0.59°C (Al Wajh), compared to the western banks that exhibit a narrower range of −0.06°C to −0.13°C (Hurghada and Massawa Dahlak). These values indicate the strength of the physical processes in adding or removing heat during summer onsets and vary geographically. This may, therefore, imply different characteristics for MHWs that develop due to different physical processes in the different areas of the Red Sea, as will be shown in the following sections.

MHW duration in relation to MHW onset drivers

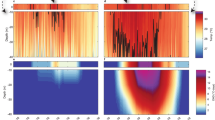

The MLHB analysis revealed geographical variations in the heat contributions of the key drivers behind summer MHW onsets. As a result, regional differences in MHW duration are anticipated in relation to their dominant drivers. Using the large number of MHWs detected from all grid points of every study region, we statistically examine here how MHW duration varies between onsets driven by 1) AHflux, 2) Hadv, 3) MLBot and 4) Mixing processes. For this, the entire duration of a MHW is considered (onset and decay), but is grouped based on the strongest warming process during its onset. The results are summarised in boxplots depicting the minimum, 25th percentile, median, 75th percentile and maximum durations of all MHWs in each region (Fig. 8). This information is an important indicator of the potential for prolonged and therefore impactful MHWs over coral bleaching regions in the basin.

Distribution of MHW duration grouped by the dominant physical process during summer MHW onset, for the period 2001–2015 in each study area of the Red Sea. Red boxplots depict atmosphere heat flux-driven (AHflux), blue boxplots depict horizontal-advection driven (Hadv), green boxplots show MHWs driven by processes at the base of the mixed layer (MLBot) and purple boxplots represent MHWs driven by mixing processes (Mixing) at the base of the mixed layer. The corresponding duration values are based on the entire event duration. The total number of MHWs (NoE) is computed from all the grid point-based events of the area and the percentage of events attributed to each driver is indicated below each boxplot. Boxplots depict the duration of the minimum, 25th percentile, median, 75th percentile and maximum number of events identified. Note that duration limits differ between rows to enhance the visualisation of variations in the duration of MHWs driven by different physical processes. The rows are arranged in a north-to-south direction, with the first row corresponding to northern regions, the second to central regions, and the third row to southern regions of the basin.

For the 2001–2015 period, the MHWs with onsets driven by AHflux last, on average, between 7 and 29 days, while those dominated by Hadv typically last 9–12 days. Onsets mainly driven by MLBot processes correspond to events with a duration of about 8–9 days, while onsets dominated by Mixing tend to last between 9 and 13 days, except for Al Lith where this type of events last on average 24 days (Fig. 8). Interestingly, the maximum MHW durations are seen in Farasan (94 days) and Al Lith (73 days) both driven by AHflux. On average, MHW onsets dominated by Mixing and Hadv are statistically related to longer events than the other two types of MHWs, except for Farasan (29 days) and Sanganeb. In these areas, the longest or comparably long MHWs seemed to correspond to onsets driven by AHflux. These results exclude events with durations considered outliers in the distribution (not shown), specifically durations of up to 102 days for AHflux-driven events, 109 days for Hadv-dominated events, 81 days for onsets driven by MLBot processes and 102 days for onsets driven by Mixing, all observed in Farasan.

Discussion and conclusions

The current study uses a MLHB analysis to explore the physical processes behind the development of summer MHWs in 12 selected regions of the Red Sea, between 2001 and 2015. These study areas are known to have undergone coral bleaching due to extreme ocean temperature conditions (see Methods). For each region we focus on the onset phase, during which we first examine the overall warming and cooling of MLT. We further assess the frequency of different physical processes acting as dominant drivers and associate it with the warming and cooling effects each of them causes throughout the onsets, as well as with the duration of the MHWs they correspond to. This study is the first to investigate the physical mechanisms behind multiple summer MHWs in the Red Sea using a dedicated numerical model.

The dominant physical process of MHW onset is strongly dependent on the local forcing characteristics as well as specific features of each region; however, the analysis reveals some interesting trends. For instance, increased contributions from AHflux are primarily found in areas with shallow bathymetry (e.g., south Red Sea) or reduced ML depth and also in regions where winds dominate atmospheric exchanges (e.g., northwest coasts). On the other hand, the impact of Hadv and MLBot processes is found predominantly in regions exhibiting pronounced summertime transport of warm waters and larger temperature gradients (e.g., in the southern and northern parts of the basin). The development of MHWs is further linked to the proximity of coastal regions to the open sea and the interaction with the circulation. For example convex-shaped areas (e.g., northern Red Sea) are generally more exposed to the general circulation and mesoscale features and tend to experience greater influence from Hadv compared to concave-shape ones. However, in certain confined locations near the coast, MHW onsets tend to be driven by Mixing processes (e.g. shallow reefs in the southern Red Sea). In the following, we use the complex relief of the Red Sea as a testbed to discuss how interactions with the local topography are likely to modify MHW onset drivers and, in turn, local warming and events characteristics.

Spatial distribution of MHW onset drivers

Our analysis indicates a distinct north-south separation of the primary onset drivers, consistent with previous research indicating a south-to-north separation in physical connectivity, related to circulation dynamics in the basin26. In particular, we find atmosphere forcing to be the primary warming mechanism for MHWs in the northeast and southwest regions of the Red Sea (Fig. 3), as well as the main cooling mechanism for most events throughout the basin (Fig. 7). This is in agreement with most reported bleaching events in the Red Sea, which have been attributed to unusual warming owing to atmospheric fluxes related to reduced winds11,20,22. The onsets primarily driven by AHflux seem to also occur slightly more often on the east coast than in the west (except Sanganeb) with Al Wajh showing the highest frequency of these MHWs.

In contrast, onsets driven by Hadv appear to be the predominant type of events in the northwest and southeast banks of the Red Sea (Fig. 4), which is in line with the processes driving the MLHB of the entire summer period in these regions, as described in Krokos et al.24. For example, the Sharm El Sheikh and Hurghada areas present a high frequency of Hadv-driven events (Fig. 4), indicative of the relatively warmer waters advected into the region (Fig. S2a,c) from the Central Red Sea (CRS). In those regions there is a notable absence of AHflux-driven onsets, most likely due to strong northeastern winds from the Mediterranean area mitigating warming from atmospheric forcing26 (see also Fig. S7). In comparison, a narrow zone close to the coasts of Al Wajh, Yanbu and Thuwal_Rabigh (Figs. 3 and 4) is typically subject to cooling by Hadv during the summer (see Krokos et al.24, Fig. 6). The strong interactions of these coastlines with the relatively cooler open sea waters can be linked to the pronounced mesoscale eddy activity in the central-northern basin during the summer27. Yet, there is a significant number of MHW onsets formed due to an influx of warm Hadv contributions across these coasts. A high percentage of Hadv-dominated MHW onsets is further displayed in the southern part of the basin, likely due to the summer-intensified eastern boundary current that transports warmer waters from the CRS to the south28,29 and particularly in Al Lith, Farasan, Al Khawkhah, and Massawa Dahlak (Figs. 4 and S2). MLBot-driven MHW onsets are least frequent, yet seem to occur slightly more often on the east than on the west coast, where they appear increasingly frequent towards the south (Fig. 5). This type of MHW onsets are primarily linked to detrainment of water due to rapid restratification during MHW onsets.

The degree to which MHW onsets are dominated by the broad-scale atmospheric and ocean circulation patterns, however, is modulated by the specific characteristics of the areas, namely their shallow bathymetry, convex or concave shape and lagoon features. For instance, despite the high frequency of Hadv-dominated onsets seen in the southern regions of the basin, a significant percentage of events in Farasan, Al Khawkhah, and Massawa Dahlak are dominated by AHflux (Figs. 3 and 4). These events are mostly identified in sites that are less exposed to open waters and tend to have a higher water residence time. The shallow bathymetry (<30 m, Fig. 1) and ML depth (<10 m, Fig. S1) of these locations can further lead to rapid accumulation of heat from intensified atmosphere heat fluxes. Similarly, the relatively shallow and semi-enclosed lagoon of Al Wajh features limited interactions with the open sea30, resulting in isolated waters that are strongly affected by atmospheric forcing. In contrast, the shallow coastlines of Wadi El Gemal and Southern Egypt in the central-west of the Red Sea (between 23°N and 25°N) exhibit a high frequency of Hadv-dominated MHWs near the coast and a high number of AHflux-driven onsets in the open ocean (Figs. 3 and 4). Because of their convex shape, these coastlines are subject to direct influences from the weak, southward flow that is part of the (weakened) permanent cyclone in the area (Figs. S1 and S2e, g), typically transporting relatively cooler waters from the north alongshore, in addition to the broader-scale warming from AHflux during the summer (see Fig. 6d in Krokos et al.24). However, the Hadv-dominated onsets close to these coasts suggest that waters advected from the north may be warmer than normal during the MHWs of the examined period.

Certain coastal and enclosed locations in the southern regions of Massawa Dahlak, Al Lith, Farasan and Al Khawkhah display a significant number of MHW onsets primarily driven by Mixing processes (Fig. 6). The confined nature of these locations, combined with their shallow depth, limits the influence of large-scale circulation and reduces the heat dissipation typically associated with vertical mixing. As a result, small scale processes parameterised by the model as lateral mixing may emerge as a key process for the redistribution and retention of heat within these confined environments. This finding is consistent with Sofianos et al.28, which highlighted the important role of Mixing processes in the southern Red Sea, based on strong trends in water masses of the area.

Understanding of MHW onset dynamics

The development of anomalous temperatures during MHW onsets depends on the balance between warming and cooling mechanisms. Our results indicate regional variations in the warming or cooling effects of the different physical processes. Overall, we find that northern areas of the Red Sea exhibit relatively higher cumulative warming and cooling compared to the central and southern regions (Figs. 1b, 2 and 7). This warming and cooling can be related to the faster rate of onset (rate of MLT change) seen in the north (Fig. 1c), indicating more pronounced heat exchanges with the atmosphere and dynamic circulation during the summer months24,31 (see also Fig. S7). The responses of the northern areas to temperature changes are enhanced from the coastal water interactions with the general circulation, facilitated by the narrower continental shelf and the stronger mesoscale circulation compared to the southern parts of the basin32. Consequently, the northern areas experience shorter but more intense summer MHW onsets, in agreement with Genevier et al.7 (Fig. 8). Conversely, the extended shallow shelves, coral reefs and scattered islands of the south may result in weakened local circulation and also limited interactions with the general circulation25. This could explain the slower MHW onset rates and, therefore, the lower cumulative warming and cooling (Figs. 1b, c, 2 and 7), in addition to the prolonged duration of MHWs in the south-central parts of the basin (Fig. 8).

In conjunction with the local topography, variations in extreme warming and cooling are further determined by the specificities of local-scale forcing across different study areas. For instance, the enhanced influence of general circulation on the northern parts of the basin (Fig. S2), together with the deeper ML depth24 (Fig. S1) likely result in MHW onsets primarily driven by Hadv. While this pattern broadly aligns with the typical summer advection of warmer, offshore waters from the CRS to the north (Fig. S2), Hadv-induced warming during MHW onsets appears relatively higher in the northwest than in the northeast study areas (Fig. 7). The typically warmer MLT in the northeast (~ 29°C–30 °C, Fig. S1) than the northwest (~ 28°C–29 °C, Fig. S1) coasts during the summer, implies smaller temperature gradients between waters advected from CRS to the northeast compared to those advected from the northeast to northwest. This suggests contributions from Hadv may not be as efficient in changing the MLT in the northeast (see also Fig. S8).

This could explain why the primary warming effect on MHW onsets in the broader areas of Al Wajh, Yanbu and Thuwal_Rabigh comes from AHflux (Figs. 3 and 7). In particular, events in the eastern coasts experience nearly double the warming due to AHflux compared to the western coast regions (Fig. 7). This is likely due to the influence of strong northerly Mediterranean winds during the summer, attenuating warming induced from radiative forcing in the northwest coasts26 (see also Fig. S7). The slightly deeper summer ML depth in the northwest (~ 10–15 m, Fig. S1) also suggests a broader dispersion of surface heat fluxes than in the northeast coasts, where summer ML depth ranges between 5 and 10 m (Fig. S1). In the case of the Al Wajh lagoon though, its semi-enclosed and shallow nature facilitates the development of pronounced cooling and warming variations, driven by both atmospheric forcing and advective fluxes (Figs. 3 and 4). Indeed, recent studies reveal that extreme temperature fluctuations within the lagoon during the summer are mainly driven by AHfluxes33. These temperature differences are further amplified by water exchanges with the denser open sea waters through the lagoon’s straits, which induce a cooling effect via advective fluxes (Fig. 7). The heat from these density-driven temperature differences is then redistributed by vigorous mixing, affecting the entire water column of the shallow lagoon33. Such dynamics are characteristic of semi-enclosed lagoons across the Red Sea34.

The warming contributions from MLBot processes remain relatively consistent across both coasts, probably indicating this process represents the ML response to local warming or cooling by the other processes (Figs. 7 and S9). In comparison, warming contributions from Mixing processes are slightly higher in the southeastern regions of the basin and in Al Wajh lagoon (Fig. 7). This likely reflects a combination of factors, including the higher frequency of Mixing-driven events in the south and pronounced temperature gradients. Lateral mixing is particularly enhanced in shallow and confined regions with limited exchanges and slow circulation (e.g., in the South Red Sea), reducing the relative importance of advective fluxes (Fig. S10).

Amongst the southern areas, Al Lith and Farasan also display a relatively higher rate of MHW onset, despite the comparatively lower warming and cooling (Fig. 1c). These south-eastern coasts are typically influenced by a southward, summer-intensified, eastern boundary flow, carrying warmer waters from the CRS28,29,35,36,37 (see also Fig. S2). This southward flow along with the shallow bathymetry of these regions increases their susceptibility to temperature fluctuations. On one hand, these shallow banks are more responsive to changes in atmospheric heat fluxes, facilitating the development of AHflux-driven events in specific locations. On the other hand, the warming associated with Hadv-driven MHW onsets surpasses that from AHflux-dominated ones. This is likely due to a cumulative effect on temperatures in a shallower region, resulting from the continuous transport of warm waters and the already elevated temperatures in the surrounding area.

There also exists a distinct west-east pattern in cooling magnitude, with the eastern coastal areas exhibiting more pronounced cooling in contrast to the western coastal regions (Fig. 7). Notably, AHflux emerges as the dominant cooling mechanism across all study areas, whether coastal or open waters (Fig. 7). This suggests that in the generally shallow coastal areas the cooling effect resulting from surface heat losses outweighs the impact of cool temperature gradients driven by horizontal advection, which plays a secondary cooling role.

MHW duration linkages with onset drivers

We also explore the statistical relationship between the predominant driving factors behind MHW onsets and the corresponding duration of the entire MHW period to which the onset is linked. Our analysis reveals that in most study areas the onsets of the longest MHWs, on average (based on median values), tend to be driven by Hadv and Mixing, except for Sanganeb and Farasan, where events with AHflux-driven onsets tend to be as long or longer (Fig. 8). The events with the maximum duration in every area are also more frequently linked to Hadv-dominated onsets, except for Al Lith, Farasan, and Al-Khawkhah in the east and Sharm El Sheikh in the west. In these areas, maximum durations are seen on events with MHW onsets dominated by AHflux, ranging from 17 to 94 days.

MHWs with Hadv-driven and Mixing-driven onsets display a tendency for meridional distribution, where slightly longer events are observed in the southern regions. MHW onsets primarily driven by AHflux exhibit also a meridional pattern, their duration increasing southwards on both sides of the basin (except for Al Khawkhah), although they appear slightly longer in the east than on the west coast. This meridional gradient in MHW duration, irrespective of the onset driver, supports the findings of Genevier et al.7, who reported longer summer events in the southern and shorter ones in the northern Red Sea. The prolonged MHWs in the southern regions are likely due to a combination of ineffective heat dissipation mechanisms (weaker summer winds) and weak local surface circulation, due to shallow bathymetry, isolated reefs and scatter islands, contributing to lower rates of onset (Fig. 1c) and total MLT trends (Fig. 2). In contrast, the northern Red Sea benefits from more effective heat dissipation mechanisms, such as intensified northwesterly winds during the summer and enhanced circulation, leading to shorter MHW durations despite the higher MLT trends (Fig. 2). Events with MHW onsets dominated by MLBot processes are almost as long as those with AHflux-driven onsets on both sides of the Red Sea and also exhibit the tendency for longer events towards the south on the west and towards the north on the east coast. A summary of MHW characteristics depending on the dominant drivers of the onset period in each study area is given in Table 1, grouped into Red Sea sub-regions.

Limitations of our study

The results of this work pertain to MHW drivers detected using 15 years of simulated data, which deviates from the typically recommended 30-year period. In addition to previous studies successfully analysing MHW drivers using short timeseries38,39, Schlegel et al.40 demonstrated that a 10-year dataset can produce reliable MHW metrics, with durations and intensities comparable to those obtained from the standard 30-year period. A complementary sensitivity analysis in our study areas corroborated this finding, showing no significant differences in MHW characteristics, when a longer timeseries was employed (Supplementary Material, Figs. S11–S12 and Tables S2, S3). In this context, it is likely that the drivers of MHWs would not exhibit significant variations in their distribution and intensity if a 30-year dataset was available, akin to the comparison between Richaud et al.39 and Huang et al.41. Instead, using a shorter reference period for identifying MHWs resulted in reduced intensity and duration compared to those identified with a longer reference period (Figs. S12–S13 and Tables S2, S3). This may be related to the absence of long-term trends in shorter timeseries, which has a greater effect on MHW characteristics40. Following Richaud et al.39 MHW drivers can be then categorised into those associated with long-term warming trends and those related to short-term oscillations around this warming. The analysis of longer time periods captures both types of drivers, whereas shorter timeseries capture only the oscillatory component.

The impact of using a short reference period (2001–2015) for identifying MHWs in this study can be assessed by considering the potential underrepresentation of their drivers due to the absence of the long-term warming trend. Extending the time (and reference) period would likely increase the detection of MHWs driven by all mechanisms, though the magnitude of this increase would vary with local conditions; A longer time frame would likely capture more intense and prolonged AHflux-driven MHWs, particularly in the northwest and southeast areas of the basin where these processes are already dominant, due to consistently higher atmospheric temperatures and potentially reduced winds. As ocean temperatures would also rise, more persistent temperature gradients could emerge in regions with significant coastal-open sea exchanges (e.g. Sharm El Sheikh and Hurghada), enhancing the role of Hadv in MHWs development. However, the long-term warming trend may also reveal stronger stratification in coastal and shallow regions, like Massawa Dahlak and Al Lith and Farasan, potentially reducing the efficiency of lateral mixing processes and complicating heat redistribution in these confined areas. The increased stratification could further reduce the influence of MLBot processes in MHW development, particularly in deeper regions.

Uncertainty in our results may also stem from limitations inherent to our model. Despite the high-resolution MLHB simulation successfully reproducing physical processes in the selected areas that are consistent with the existing literature, our results in specific locations require careful interpretation, due to potential biases in the model’s outputs. For instance, model validation indicated a higher bias near the coasts of Hurghada, Al Wajh, Southern Egypt, Farasan and Al Khawkhah (Figs. S4 and S5). This bias may also be related to inconsistencies in the satellite dataset over coastal areas42. Consequently, MLT and the characteristics of the associated MHWs may exhibit greater ambiguity in proximity to these coasts. Additionally, the interactions with waters below the ML through entrainment, detrainment and vertical mixing are collectively categorised under MLBot processes, preventing their differentiation. Finally, small-scale or sub-grid processes, such as internal wave breaking—known to induce cooling in specific regions43 or mitigate heat stress on corals through high-frequency temperature fluctuations44—are not explicitly resolved in our model. Such small-scale, local variations could have been captured if in situ data were available for the areas under investigation, providing further validation of our model. Overall, these limitations highlight the need for enhanced in-situ data collection in sensitive coral regions to enhance model validation and understanding of the thermal conditions affecting coral populations.

Ecological impact of MHWs in the Red Sea

Acute responses from marine ecosystems, including coral bleaching45,46, may be more commonly anticipated in areas with rapid warming20 or increased cumulative warming, which usually results in higher bleaching severity47. The northern Red Sea exhibits the highest Ronset and strongest temperature changes between 2001 and 2015 (Fig. 1b, c). However, coral bleaching in this region has rarely been observed and presented as mild13. A recent study, in fact, indicated resilient coral reefs in the Gulf of Aqaba in response to the most severe MHW documented in the region48. The northern Red Sea is generally considered as a thermal refuge for corals, since they appear resilient to extreme temperatures much higher than their mean summertime maxima13,49. This is usually attributed to the historical migration of corals into the Red Sea through the Bab el-Mandeb strait, suggesting that all corals found throughout the basin have previously been acclimated to warmer southern Red Sea conditions49. In addition, high-resolution Lagrangian particle-tracking models, in situ measurements and satellite observations have shown strong coral reef connectivity between the northern and central Red Sea, indicating a strong genetic exchange that remains active to this day26,39,50,51. In other words, coral reefs in the northern and northwestern Red Sea (where climatological temperatures are cooler) receive a high level of larval recruits from reefs further south and/or east, where temperatures are consistently warmer. This thermal refuge may therefore represent an ongoing process, with northern corals continually receiving recruits from reefs acclimated to warmer temperatures, a mechanism that may persist even as Red Sea temperatures rise due to anthropogenic warming. Indeed, a bleaching-induced experiment documented changes in the microbiome of heat-sensitive corals in contrast to the stability observed in heat-tolerant corals, which thrive in habitats characterized by naturally elevated temperature extremes52. Given that MHWs in the northern regions are mostly caused by the advection of warmer water masses, they are likely driven by the same oceanographic currents—such as boundary currents and eddy-driven transport—that also propagate coral larvae throughout the region. Therefore, these MHWs likely present conditions similar to those that all coral recruits originating from those water masses’ sources are acclimated to, further explaining the absence of severe coral bleaching there. However, as MHWs become more frequent, prolonged and more intense, even the northern reefs of the basin may become increasingly vulnerable to temperature extremes, increasing the risk of coral bleaching and challenging the long-term resilience of this thermal refugee.

Both the cumulative warming and the duration of MHWs are therefore important indicators of bleaching severity. We observed horizontal advection-driven and mixing-driven MHWs to persist longer on average, yet the peak durations observed in most southern regions occurred during atmosphere heat flux-driven events. These types of MHWs are most common in regions that are shallow or shielded from open waters and as they develop more slowly, they can also be long due to the lack of active circulation. This aligns with in-situ bleaching surveys, often revealing more severe coral bleaching inshore and midshore compared to corals offshore11,12,13.This could be due to the presence of cooler waters being often found offshore, as well as the presence of stronger currents found at offshore sites that may aid in the removal of harmful reactive oxygen species53,54. Given that coral bleaching data is sparse in much of the Red Sea55, this analysis reveals distinct signals on the predominant drivers of potentially impactful MHWs throughout the Red Sea.

While horizontal advection was found to be the strongest driver of MHW warming, atmospheric heat fluxes were the strongest cooling mechanism during MHWs over the entire basin. If wind speeds decrease in the wider area of the Arabian Peninsula, as projected by Alsarraf et al.56, corals in the Red Sea may experience more prolonged and/or intense MHWs in the 21st century, due to reduced evaporative cooling. However, the global warming impact on both atmospheric and oceanographic processes in the region is still not fully understood. The Red Sea will host a coral reef ecotourism-centered giga-project from 2030 (redseaglobal.com), and any weakening of local cooling mechanisms due to climate change may pose a threat to the coral reefs there. This study thus highlights the complexity of MHW drivers and the importance of quantifying their contribution if we are to understand the impacts climate change may have on coral reefs.

Methods

Study areas

Following Genevier et al.7, we select 12 regions of interest in the Red Sea, where several coral bleaching events have been observed between 1982 and 2015 (Fig. 1a), the majority of which were linked to extreme SST conditions. Our objective is therefore to elucidate the underlying mechanisms contributing to the development of summer MHWs, which have frequently affected these coral regions of the basin in the past. Details on the names, and locations of the selected areas are given in Table S1.

The Red Sea can be broadly divided into the northern (~24°N–28°N), central (~18°N–24°N) and southern regions (north of Bab el-Mandeb - 28°N), based on its dynamic wind-driven circulation, that is also strongly influenced by atmosphere-ocean buoyancy fluxes (as discussed in [25] and references therein) (Fig. 1a). During the summer months, the northern part of the basin is characterized by pronounced air-sea heat losses, due to strong northern winds that gradually weaken towards the southern part of the basin57. In contrast, the southern end of the Red Sea features a more complicated circulation, owing to complex topography, high spatiotemporal variability of atmospheric forcing and a seasonal inflow through the strait of Bab el-Mandeb28,35. This intermediate-layer freshwater input from the Gulf of Aden propagates northward, while northwesterly winds drive a surface boundary flow along the eastern margin from the central to the southern end of the basin, where it bifurcates, returning partly as a northward, western boundary current28,29 (Figs. S1 and S2). The most striking oceanographic features of the season, are the intense semi-permanent anticyclonic eddy that forms at ~18.5 °N, in response to Tokar wind jets25 and the weakened (permanent) cyclone which dominates northern Red Sea around 25°N25,57 (Figs. S1 and S2). Additionally, buoyancy-driven stratification leads to a shallow mixed layer depth (~10–30 m) throughout the basin, with a north-south gradient in mixed layer temperatures (MLT) (Fig. S1).

Ocean model dataset

To identify the MHWs, daily MLT data were obtained from a regional hydrodynamic simulation of the Red Sea that covered the period 2001–2015 and was conducted with the MIT general circulation model presented in Krokos et al.24. The model covers the entire Red Sea domain, has a horizontal resolution of 0.01°, and uses a varying vertical resolution from 4 m at the surface to 300 m at the bottom, over 50 vertical layers. It is forced by a 5-km horizontal resolution atmospheric product, generated by downscaling the ERA-Interim reanalysis58, using an assimilative configuration of the Advanced Research version of the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model59.

The skill of the model to accurately represent (sub) surface circulation features, water column characteristics and dynamical processes of the Red Sea has been extensively validated against various datasets and applications (e.g., Krokos et al.24,57). A further comparison between the summer, remotely sensed Operational SST and Sea Ice Analysis (OSTIA) system data and the model-derived SST over the time period of the model simulation (2001–2015), reveals a good temporal (Fig. S3) and almost uniform spatial correlation (correlation coefficient >0.8) across all the study areas (Figs. S4; S5, a, c, e, g, i, k). While the equivalent RMSE values range from 0.4 to 1 in the majority of regions, certain coastal locations in Hurghada, Southern Egypt, Al Wajh, Farasan and Al Khawkhah display higher RMSE values (1.4–2), indicating a higher systematic model bias (Figs. S4; S5, b, d, f, h, j, i). This could be attributed to uncertainties in the bathymetry of these areas in combination to their complex topography, which includes shallow and relatively isolated reefs with pronounced temperature variability and scattered islands25. Such conditions challenge the accuracy of both for the remotely sensed and the modelled SST data.

Detection of marine heatwaves

The statistics associated with the detected MHWs (e.g., duration) are produced using the latest version of the Hobday et al.60 algorithm (available at https://github.com/coecms/xmhw). To identify summer MHWs between 2001 and 2015, accounting for coral bleaching favourable conditions in the Red Sea study areas7, we apply a seasonal, local climatological threshold of the 95th percentile (for temperature) and a minimum duration of 7 days. As we are also interested in events that affect the entire mixed layer, the MHW detection algorithm is applied on the daily MLT instead of the commonly used SST. Each MHW is characterized by an onset period (time between its start and the day exhibiting the MHW’s peak temperature) and a decay phase (time from the MHW’s peak to its end). Our analysis focuses on the events’ onset phase and the physical processes that initiated summer (July–November) MHWs, targeting the period when coral bleaching in the Red Sea has been most severe and most often observed. We then investigate the events’ characteristics, in particular, duration in relation to the physical drivers behind the MHW onsets

The model’s ability to detect summer MHWs is first evaluated in specific locations of each study area, where surface events have been documented by Genevier et al.7. This involves comparing the timing of the locally-observed, surface MHWs7 with the MLT-based and model-detected events, using a common baseline period of 2001–2015. We find a good agreement between modelled and observed MHWs at a local scale across most areas, except for Farasan, Al Khawkhah, Al Lith, Sanganeb, Hurghada and Sharm El Sheikh (Fig. S6). Differences in the identified MHWs in those regions may stem from differing temperatures used for MHW detection (SST versus MLT) and the different spatial resolution of the datasets. The implications of analysing a short simulation (constrained by data availability), as opposed to the recommended 30-year period, are further explored in the discussion section.

Mixed layer heat budget computation

Temperature variability in the ML is governed by heat interactions between the atmosphere and the ocean, as well as by advective and diffusive fluxes of heat from the general and mesoscale circulation and the deepening or shallowing of the ML. For the first time, we evaluate here the role of the physical processes leading to summer MHWs in the Red Sea by studying the dynamics of the ML. We use a MLHB analysis to quantify the positive or negative heat contributions from AHflux, Hadv, MLBot and Mixing, to the total MLT change during the MHW onset period of every locally-detected MHW between 2001 and 2015. The MLBot processes include the heat transport resulting from the combined interactions between the base of the ML and the underlying water masses, such as the entrainment or detrainment of waters during ML shallowing and deepening, lateral induction, vertical diffusion and vertical advection. Mixing processes represent horizontal and vertical diffusive fluxes within the mixed layer24. These processes are described in the following MLHB equation, which was constructed using daily-averaged outputs from the MITgcm simulation of the Red Sea, between 2001 and 201524. The closed and complete budget of temperature change at each grid cell was diagnosed according to Kim et al.61 in the following form:

where T represents the mixed layer temperature at each grid point, μ the 3D velocity, Q(z) the sum of the surface atmosphere heat fluxes (net shortwave, net longwave radiation, latent and sensible heat flux), \({\rho }_{0}\) = 1029 kgm−3 the density of the seawater, Cp the specific heat capacity of seawater (3994 J/kg C), \({\nabla }_{h}\) the horizontal biharmonic operator and \({k}_{H}\) and \({k}_{z}\) the respective horizontal and vertical diffusion coefficients. In particular, \({k}_{z}{\gamma }_{T}^{t}\) represents turbulent non-local transport of properties. The diagnostic balance of MLT is computed by averaging each term over the ML at each grid point and timestep. The exact closure of the MLHB allowed for an estimation of entrainment (or detrainment) processes and vertical advection that are characterized as MLBot processes in addition to mixing of temperature at the ML depth.

Diagnosing dominant drivers of MHWs

The tendency of a process to act as a warming or cooling mechanism during MHW onset is diagnosed by statistically analysing heat contributions from the MLHB processes during multiple events, from all grid points within a region. For every MHW identified in a given grid point we first compute the total warming and total cooling budgets separately, i.e., the total positive and total negative heat contributions from all the processes acting on the development phase of an event, and report the rate of temperature change throughout the MHW onset period (Ronset). We then determine the dominant driver of an event by identifying the process yielding the maximum positive heat contribution during MHW onset and its relative contribution to the total warming budget (in percentage). The mean probability for each physical process to govern MHW onsets in an area is determined by averaging these percentages throughout the ensemble of events from all the grid points of that area. Based on the large sample of MHW onsets identified from the total number of grid points in an area we further estimate the average warming or cooling contribution of each process individually to the respective total warming or cooling budget of MHW onset. The mean heat contribution of each MLHB physical process, as well as the dominant driver behind MHW onsets, may change with season and region, thus justifying the importance of exploring the local-scale mechanisms at play through a MLHB analysis.

Data availability

The remotely sensed Operational SST and Sea Ice Analysis (OSTIA) system data used to validate the model are available at: https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/SST_GLO_SST_L4_REP_OBSERVATIONS_010_011/description.

Code availability

The code used to analyse these data and generate the results presented in this study can be obtained from https://github.com/coecms/xmhw (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5112732). All figures were created using the software package Python.

References

Wong, A. S., Vrontos, S. & Taylor, M. L. An assessment of people living by coral reefs over space and time. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 7139–7153 (2022).

DiBattista, J. D. et al. A review of contemporary patterns of endemism for shallow water reef fauna in the Red Sea. J. Biogeogr. 43, 423–439 (2016).

Baker, A. C., Glynn, P. W. & Riegl, B. Climate change and coral reef bleaching: An ecological assessment of long-term impacts, recovery trends and future outlook. Estuar., Coast. Shelf Sci. 80, 435–471 (2008).

Glynn, P. W. Widespread coral mortality and the 1982–83 El Niño warming event. Environ. Conserv. 11, 133–146 (1984).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 543, 373–377 (2017).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Spatial and temporal patterns of mass bleaching of corals in the Great Barrier Reef. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–12 (2018).

Genevier, L., Jamil, T., Raitsos, D., Krokos, G. & Hoteit, I. Marine heatwaves reveal coral reef zones susceptible to bleaching in the Red Sea. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 2338–2351 (2019).

Chaidez, V., Dreano, D., Agusti, S., Duarte, C. M. & Hoteit, I. Decadal trends in Red Sea maximum surface temperature. Sci. Rep. 7, 8144 (2017).

Ziegler, M., Arif, C. & Voolstra, C. R. Symbiodiniaceae diversity in Red Sea coral reefs & coral bleaching. Coral Reefs of the Red Sea. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05802-9_5 (2019).

Devantier, L., Turak, E. & Al-Shaikh, K. Coral bleaching in the central-northern Saudi Arabian Red Sea, August–September 1998. In Proc. International Workshop on the Extent and Impact of Coral Bleaching in the Arabian Region. National Commission for Wildlife Conservation and Development, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (2000).

Furby, K. A., Bouwmeester, J. & Berumen, M. L. Susceptibility of central red sea corals during a major bleaching event. Coral Reefs 32, 505–513 (2013).

Monroe, A. A. et al. In situ observations of coral bleaching in the central Saudi Arabian Red Sea during the 2015/2016 global coral bleaching event. PLoS One, 13, e0195814 (2018).

Osman, E. O. et al. Thermal refugia against coral bleaching throughout the northern Red Sea. Glob. change Biol. 24, e474–e484 (2018).

Raitsos, D. E. et al. Abrupt warming of the Red Sea. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL047984 (2011).

Hamdeno, M., Alvera-Azcárate, A., Krokos, G. & Hoteit, I. Investigating the long-term variability of the Red Sea marine heatwaves and their relationship to different climate modes: focus on 2010 events in the northern basin. Ocean Sci. 20, 1087–1107 (2024).

Cantin, N. E., Cohen, A. L., Karnauskas, K. B., Tarrant, A. M. & McCorkle, D. C. Ocean warming slows coral growth in the Central Red Sea. Science 329, 322–325 (2010).

Krokos, G. et al. Natural climate oscillations may counteract Red Sea warming over the coming decades. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 3454–3461 (2019).

Eladawy, A. et al. Appraisal of coral bleaching thresholds and thermal projections for the northern Red Sea refugia. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 938454 (2022).

Agulles, M., Jordà, G., Hoteit, I., Agustí, S. & Duarte, C. M. Assessment of Red Sea temperatures in CMIP5 models for present and future climate. PloS One, 16, e0255505 (2021).

Genin, A., Levy, L., Sharon, G., Raitsos, D. E. & Diamant, A. Rapid onsets of warming events trigger mass mortality of coral reef fish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 25378–25385 (2020).

Alawad, K. A., Al-Subhi, A. M., Alsaafani, M. A. & Alraddadi, T. M. Atmospheric forcing of the high and low extremes in the sea surface temperature over the Red Sea and associated chlorophyll-a concentration. Remote Sens. 12, 2227 (2020).

Pineda, J. et al. Two spatial scales in a bleaching event: Corals from the mildest and the most extreme thermal environments escape mortality. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58, 1531–1545 (2013).

Kara, A. B., Rochford, P. A. & Hurlburt, H. E. Mixed layer depth variability over the global ocean. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 108, 3106 (2003).

Krokos, G., Cerovečki, I., Papadopoulos, V. P., Hendershott, M. C. & Hoteit, I. Processes governing the seasonal evolution of mixed layers in the red sea. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 127, e2021JC017369 (2022).

Wang, Y., Raitsos, D. E., Krokos, G., Zhan, P. & Hoteit, I. A Lagrangian model-based physical connectivity atlas of the Red Sea coral reefs. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 925491 (2022).

Langodan, S. et al. The climatology of the Red Sea – part 1: the wind. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4509–4517 (2017).

Zhan, P. et al. The eddy kinetic energy budget in the Red Sea. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 121, 4732–4747 (2016).

Sofianos, S. S. & Johns, W. E. Observations of the summer Red Sea circulation. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans, 112, (2007).

Yao, F. et al. Seasonal overturning circulation in the Red Sea: 1. Model validation and summer circulation. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 119, 2238–2262 (2014).

Zhan, P. et al. Submesoscale processes in the upper Red Sea. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 127, e2021JC018015 (2022).

Papadopoulos, V. P., Krokos, G., Dasari, H. P., Abualnaja, Y. & Hoteit, I. Extreme heat loss in the northern Red Sea and associated atmospheric forcing. Front. Marine Sci. 9, 68114 (2022).

Zhan, P., Subramanian, A. C., Yao, F. & Hoteit, I. Eddies in the Red Sea: A statistical and Dynamical Study. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 119, 3909–3925 (2014).

Zhan, P. et al. Physical forcing of phytoplankton dynamics in the Al-Wajh lagoon (Red Sea). Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 7, 373–384 (2022).

Papagiannopoulos, N. et al. Phytoplankton biomass and the hydrodynamic regime in NEOM, Red Sea. Remote Sens. 13, 2082 (2021).

Sofianos, S. S. & Johns, W. E. An oceanic general circulation model (OGCM) investigation of the Red Sea Circulation: 2. three-dimensional circulation in the Red Sea. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 108, (2003).

Dreano, D., Raitsos, D. E., Gittings, J., Krokos, G. & Hoteit, I. The Gulf of Aden Intermediate Water Intrusion regulates the southern Red Sea summer phytoplankton blooms. PLOS ONE 11, e0168440 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Physical connectivity simulations reveal dynamic linkages between coral reefs in the southern Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. Sci. Rep. 9, 16598 (2019).

Oliver, E. C. et al. The unprecedented 2015/16 Tasman Sea marine heatwave. Nat. Commun. 8, 16101 (2017).

Richaud, B. et al. Drivers of marine heatwaves in the Arctic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 129, e2023JC020324 (2024).

Schlegel, R. W., Oliver, E. C., Hobday, A. J. & Smit, A. J. Detecting marine heatwaves with sub-optimal data. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 737 (2019).

Huang, B. et al. Prolonged marine heatwaves in the Arctic: 1982–2020. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL095590 (2021).

Brewin, R. J. et al. Evaluating operational AVHRR sea surface temperature data at the coastline using surfers. Estuar., Coast. Shelf Sci. 196, 276–289 (2017).

Wyatt, A. S. et al. Hidden heatwaves and severe coral bleaching linked to mesoscale eddies and thermocline dynamics. Nat. Commun. 14, 25 (2023).

Safaie, A. et al. High frequency temperature variability reduces the risk of coral bleaching. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–12 (2018).

Sahin, D. et al. Heating rate explains species-specific coral bleaching severity during a simulated marine heatwave. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 706, 33–46 (2023).

Martell, H. A. & Zimmerman, R. C. Heating rate modulates the metabolic response of the staghorn coral acropora cervicornis (Lamarck, 1816). Marine Biol. 168, (2021).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature, 543, 373−377 (2017).

Kochman-Gino, N.-R. & Fine, M. Reef building corals show resilience to the hottest marine heatwave on record in the Gulf of Aqaba. Front. Marine Sci. 10, 1215567 (2023).

Fine, M., Gildor, H. & Genin, A. A coral reef refuge in the Red Sea. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 3640–3647 (2013).

Raitsos, D. E. et al. Sensing coral reef connectivity pathways from space. Sci. Rep. 7, 9338 (2017).

Nanninga, G. B., Saenz-Agudelo, P., Manica, A. & Berumen, M. L. Environmental gradients predict the genetic population structure of a coral reef fish in the red sea. Mol. Ecol. 23, 591–602 (2014).

Ziegler, M., Seneca, F. O., Yum, L. K., Palumbi, S. R. & Voolstra, C. R. Bacterial community dynamics are linked to patterns of coral heat tolerance. Nat. Commun. 8, 14213 (2017).

Nakamura, T. & van Woesik, R. Water-flow rates and passive diffusion partially explain differential survival of corals during the 1998 bleaching event. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 212, 301–304 (2001).

Nakamura, T. Importance of water-flow on the physiological responses of reef-building corals. Galaxea, J. Coral Reef. Stud. 12, 1–14 (2010).

Berumen, M. L. et al. The status of coral reef ecology research in the Red Sea. Coral Reefs 32, 737–748 (2013).

Alsarraf, H. & Den Broeke, M. V. Using the WRF Regional Climate Model to simulate future summertime wind speed changes over the Arabian Peninsula. J. Climatol. Weather Forecast. 3, 144 (2015).

Krokos, G. et al. Seasonal variability of red sea mixed layer depth: The influence of atmospheric buoyancy and momentum forcing. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, 1342137 (2024).

Dee, D. P. et al. The ERA-Interim reanalysis: Configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q. J. R. Meteorolog. Soc. 137, 553–597 (2011).

Viswanadhapalli, Y., Dasari, H. P., Langodan, S., Challa, V. S. & Hoteit, I. Climatic features of the Red Sea from a regional assimilative model. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 2563–2581 (2016).

Hobday, A. J. et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr. 141, 227–238 (2016).

Kim, S.-B., Fukumori, I. & Lee, T. The closure of the ocean mixed layer temperature budget using level-coordinate model fields. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 23, 840–853 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Office of sponsored Research (OSR) at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) under the virtual Red Sea Initiative (Grant # REP/1/3268-01-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D. and D.E.R. conceived this study. S.D. and G.K. analysed the mixed layer heat budget in the Red Sea. D.E.R. and L.G. analysed the marine ecosystem impacts. S.D. wrote the original draft. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and editing of the manuscript (S.D., G.K., D.E.R., L.G., I.H.).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jennifer Veitch, Heike Langenberg. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Darmaraki, S., Krokos, G., Genevier, L. et al. Drivers of marine heatwaves in coral bleaching regions of the Red Sea. Commun Earth Environ 6, 120 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02096-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02096-5

This article is cited by

-

Concurrent atmospheric heatwaves intensify marine heatwaves through air-sea heat flux change in the Mediterranean Sea

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)