Abstract

The volume of the East Antarctica Ice Sheet is equivalent to ~52 m of sea-level rise, but whether the ice sheet is a major contributor to global sea-level increase remains debated. How an ice sheet responds to climate-induced perturbations strongly depends on the physical conditions below the ice-bed interface; therefore, constraining the solid Earth structure beneath East Antarctica is critical. However, sparse seismic station coverage has limited our ability to image key characteristics. Here we employ full-waveform ambient noise tomography, an approach that better resolves Earth structure in sparsely sampled areas compared to traditional techniques, and our results reveal previously unrecognized, low-velocity anomalies under the Wilkes and Aurora Subglacial Basins. Our findings suggest thinner-than-expected lithosphere and thermally perturbed upper mantle, implying drastically different geothermal heat flux and mantle viscosity inputs compared to those from prior tomographic studies. This has notable implications for accurate ice-sheet modeling and future global sea-level projections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

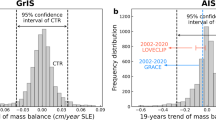

Since the early 1980s, cumulative ice mass loss from Antarctica has increased from ~50 to ~115 Gt year−1, resulting in substantial contributions to global sea-level rise1,2. While the West Antarctic Ice Sheet has been widely recognized as a major source of ice loss, the stability of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS) remains debated. Some studies suggest that cumulative EAIS contributions to sea-level rise over the last four decades (4.4 ± 0.9 mm) are almost as large as those from West Antarctica (6.9 ± 0.6 mm), with ice loss occurring at a rate of ~50 Gt year−1 between 2009 and 20171,3. These studies further suggest that EAIS loss dominantly occurs in the Wilkes Land sector (Fig. 1), a portion of the continent that may have substantially contributed to sea-level rise during past interglacial cycles4,5,6,7,8. In contrast, other studies2,9,10 indicate that ice loss in East Antarctica has only averaged ~4 Gt year−1 over the past several decades, suggesting that the EAIS mass balance is close to zero and that this portion of Antarctica does not play a notable role in the global sea-level budget.

Geographic regions of interest include the WARS West Antarctic Rift System, TAMs Transantarctic Mountains, PSB Polar Subglacial Basin, VSH Vostok Subglacial Highlands, WSB Wilkes Subglacial Basin, BSH Belgica Subglacial Highlands, ASB Aurora Subglacial Basin, QML Queen Mary Land. Red triangles denote stations used in our inversion. Black dashed lines denote faults interpreted by Cianfarra and Maggi38 and references therein. The area shown in the main map is shaded gray in the inset, which also shows the location of the Lambert Rift (orange). WA West Antarctica, EA East Antarctica.

These disparate estimates make the EAIS the most uncertain component of Antarctica’s mass balance, and this is due, in part, to our limited understanding of its underlying geologic structure and rheological properties11,12. The sensitivity, response, and resilience of the ice sheet to climate change critically depend on solid-Earth-ice feedbacks, which can either hinder or enhance ice flow. For example, rapid bedrock uplift in response to loading changes can reduce ice outflux at the grounding line and provide a stabilizing effect on the ice sheet, but this type of topographic response depends on the thickness of the lithosphere and the viscosity structure of the mantle13,14. In the vicinity of subglacial basins, faster ice flow often occurs, partially because basin sediments reduce basal friction and promote sliding15. Additionally, some large-scale basins form in response to rifting and lithospheric extension16 and are associated with elevated geothermal heat flux (GHF)17. Under high-pressure conditions beneath thick ice, increased GHF can promote melting and lubrication along the ice sheet base18,19. The large-scale Wilkes and Aurora Subglacial Basins in East Antarctica (Fig. 1) may play noteworthy roles in EAIS behavior, but limited sampling and discrepancies between both geophysical and geological models have led to uncertainty regarding the basins’ structure and their origins. These details are needed to determine how future EAIS stability will be impacted by solid Earth feedbacks20.

The Wilkes Subglacial Basin (WSB; Fig. 1) is a 1400-km-long depression that extends along the inland side of the Transantarctic Mountains (TAMs)21. Early studies22 suggested that the WSB is a fault-bounded extensional basin associated with Ross-age (~500 Ma) continental rifting, but later investigations23 argued for a flexural origin, where the basin is an “outer low” created by the Cenozoic uplift of the TAMs and the flexural rigidity of the East Antarctic lithosphere. More recent studies24 have suggested the WSB developed as a back-arc basin between the East Antarctic craton and the Ross Orogen, with extension reactivated during the Jurassic-Cretaceous break-up of Gondwana. A composite model for the WSB has also been put forth, which suggests the basin geometry results from its inherited crustal structure, glacial erosion, and flexural uplift25. Uncertainties regarding the origin of the WSB largely stem from different geophysical findings, all of which worked within their data and resolution limitations. Crustal thickness estimates beneath the WSB range from ~25 km26,27 to ~40 km28,29,30, and lithospheric thickness estimates vary from 120 to 200 km31,32,33,34. These different estimates have notably different implications for EAIS stability.

Compared to the WSB, our knowledge of the Aurora Subglacial Basin (ASB; Fig. 1) is even more limited. Geologic reconstructions of this 150-km long, 25-km wide basin suggest it is underlain by a late Mesoproterozoic craton that was sutured together during the Indo-Australian-Antarctic collision35, and some studies argue the area has been relatively unaffected by later tectonic processes28. However, others suggest that late Paleozoic to Mesozoic trans-tensional faults developed within the ASB35 and were reactivated by late Cretaceous rifting when Antarctica separated from Australia36. Alternatively, morphological interpretations of subglacial bed relief suggest that extension within the ASB is associated with Cenozoic tectonic activity, driven either by upper mantle plumes or by far-field stresses in the Southern Ocean37,38,39. The structural characteristics of the ASB are poorly constrained. Crustal thickness estimates beneath the basin range from 25 to 40 km26,30,40, while lithospheric thicknesses range from 80 to 200 km31,32,33,34.

To further understand the East Antarctic subglacial basins and how they impact the EAIS, we have developed a new model of the lithospheric and mantle shear-wave velocity (VS) structure using a full-waveform, long-period ambient noise approach. This computationally intensive method has been shown to better resolve Earth structure compared to more traditional tomographic techniques (Methods)41,42,43,44,45, particularly within sparsely sampled geographic regions46,47. This makes the full-waveform inversion method well suited to our East Antarctic study region, where few long-running seismic stations exist to date. Our results highlight previously unresolved seismic structures within the WSB and ASB, which have important implications for ice-sheet stability.

Results

Our tomographic model was developed using long-period ambient noise recorded by 133 temporary and long-term seismic stations deployed across Antarctica (Fig. 1). Interstation ambient noise correlation functions are frequently presumed to approximate Empirical Green’s Functions (EGFs; Methods)48. We extracted the Antarctic EGFs using a frequency-time normalization technique that has been demonstrated to improve the EGFs signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), thereby allowing longer-period signals to be obtained49 (Supplementary Figs. 1–4). Day-long records between each pair of stations were cross-correlated and stacked, and the resulting EGFs were then filtered into overlapping frequency bands ranging from 40 to 340 s (Methods; Supplementary Figs. 1–4).

Synthetic waveforms, simulated in a spherical grid using a 3D finite-difference waveform propagation approach50,51, were initially calculated with a modified version of the AK135 velocity model52 that incorporates crustal thicknesses from An et al.31 and crustal VP, VS, and density from Laske et al.53. We note that this same starting crustal model has been used in previous tomographic studies of Antarctica32. As the 3D velocity model was iteratively updated, the phase delay (misfit) between the synthetic waveforms and the EGFs was reduced (Supplementary Fig. 5). Sensitivity kernels, which were computed with the scattering integral technique54 (Supplementary Fig. 6), as well as different damping and smoothing parameters were also employed in the inversion (Methods). We note that our model was developed in a coordinate system rotated to the Equator to avoid the longitude singularity at the South Pole. Our final model has an average phase delay misfit of 1.66 s, a significant improvement over that of the starting model (10.34 s).

Our results show previously unresolved seismic structures beneath the East Antarctic subglacial basins. Specifically, above ~150 km depth, there is a change from slow VS beneath the northern WSB (Figs. 2 and 3; Anomaly I) to faster VS beneath the central portion of the basin (Anomaly II). At deeper depths, the WSB is underlain by fairly uniform slow VS down to ~350 km depth (Anomaly III). A more pronounced slow anomaly (IV), concentrated between ~150 and 300 km depth, is also observed near the southern end of the basin. The slow ASB anomaly (V) is even more distinctive. Its slowest VS are concentrated between ~140 and 250 km depth, but the slow ASB signature persists to ~300–350 km.

Maps show our model (left) and corresponding best-fit resolution test results (right) in the rotated coordinate system where South Pole is at (0°, 0°). The locations of the cross-sectional profiles shown in Fig. 3 are indicated on the 100 km depth panels. Green triangles indicate stations, and Roman numerals denote anomalies discussed in the text. In the left panels, bedrock topography contours21 at 500 and −500 m are highlighted by the thin solid and dashed lines, respectively.

Profile locations are shown in Fig. 2. In (a)–(c), the top panels show subglacial bedrock topography (black line) and ice coverage (blue)21. The bold horizontal line denotes sea-level, and thin gray lines denote intervals of 1 km. Geographic labels are the same as in Fig. 1. The middle panels show the model results along the profiles, where distance is in degrees, depth is in kilometers, and VS are relative to the AK135 global average Earth model52. The bottom panels are our best-fit synthetic resolution test results, which are plotted in a similar manner to the middle panels, but the thin black lines denote the vertical grid used in the inversion. Roman numerals denote anomalies discussed in the text. The dashed line in (b) marks the interpreted base of the WSB lithospheric lid.

The ASB is bordered by fast VS beneath the Belgica Subglacial Highlands (BSH; Anomaly VI) and Queen Mary Land (QML; Anomaly VII), which extend to ~150–200 km depth (Figs. 2 and 3). These fast anomalies are consistent with prior tomographic images and associated lithospheric thickness estimates for these regions55, though we emphasize that our model better delineates these different tectonic regions from one another. The fast BSH structure coincides with a magnetic high and is likely associated with the Terre Adélie Craton, a remnant of the Rodinia Supercontinent that was later amalgamated to Antarctica (Ferraccioli et al.24 and references therein). The fast VS in QML agrees with prior studies that suggest this area is underlain by Mesoproterozoic lithosphere35.

Our model also shows several other seismic anomalies that match prior continental- and regional-scale studies, thereby providing further confidence in our results. For example, we observe an abrupt change from slow VS under the West Antarctic Rift System (Figs. 2 and 3, Anomaly VIII) to fast VS beneath the TAMs, about ~100 km inland of the TAMs front, which previous investigations have associated with a 200–300 K temperature difference that may support the TAMs uplift23,56. Thicker, faster structure beneath the Miller Range (Anomaly IX) coincides with where Archean-age rocks have been identified57, and the notably fast VS beneath the Vostok Subglacial Highlands (VSH; Anomaly X) that extends to ~300 km depth in our model coincides with some of the thickest lithosphere modeled in East Antarctica55. Slow VS Anomaly XI (Figs. 2 and 3) underlies the Polar Subglacial Basin and is consistent with a region of thinner, Proterozoic-aged lithosphere58.

Both checkerboard and targeted resolution tests (Methods; Supplementary Note 1) have been used to evaluate the East Antarctic seismic anomalies (Supplementary Figs. 7–13), and these results indicate that our model is best resolved between ~50 and 350 km depth. Lateral smearing is somewhat more pronounced in the ASB and QML regions, and synthetic input anomalies can vertically smear up to ~70 km, depending on their depth in the model space. That said, the main features of interest are well resolved, which allows us to further evaluate the tectonic structure of the East Antarctic basins. Sediment thickness estimates within the WSB and ASB range from 1 to 4 km and 4 to 13 km, respectively27,30; however, our targeted resolution tests (Supplementary Fig. 11) demonstrate that our model is largely insensitive to such shallow structure. Our tests also show that the slow basin structures cannot be attributed to offshore anomalies, such as those identified by Lloyd et al.32, laterally smearing inland nor from anomalies near the South Pole laterally smearing across East Antarctica (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 13). The variable structure we observe (Figs. 2 and 3) is also not well matched by the fairly uniform fast seismic velocities shown throughout East Antarctica in prior global- and continental-scale tomographic studies (Supplementary Fig. 12; Lloyd et al.32 and references therein). Therefore, the structure of the WSB and ASB require further consideration.

Discussion

Most regional-scale seismic investigations do not image the detailed structure of the WSB seen in our results, but White-Gaynor et al.59 and Zhang et al.60 reveal slow seismic velocities under the northern, coastal portion of the WSB, with faster velocities further inland, similar to Anomalies I and II (Figs. 2 and 3). These prior studies suggest that the slow, northern WSB is associated with thermally perturbed upper mantle and/or thin lithosphere. Potential field data24,27,30 and GHF estimates33,61,62 also propose thinner lithosphere and higher heat flux beneath the northern WSB compared to the rest of the basin. The deeper WSB seismic structure (Anomaly III) resembles that previously imaged beneath the Lambert Rift58 in northern East Antarctica (Fig. 1), which is interpreted to be an intracontinental rift basin that developed along pre-existing zones of lithospheric weakness during the Permian and that was reactivated by Cretaceous trans-tensional faulting (Ferraccioli et al.36 and references therein).

Our VS structure in this area is best replicated using a ~140 km thick, +3% to +6% fast lithospheric lid in the central WSB (II), no discernible lid in the northern WSB (I), and a −5% to −8% slow mantle anomaly (III; Figs. 2 and 3; Supplementary Fig. 9). Given its comparable structure at depths > 150 km to that imaged by Heeszel et al.58, we suggest the WSB is a Ross-aged rift that was reactivated during the Mesozoic24. Anomaly II has a fairly weak and varied seismic signature, which was difficult to replicate with our synthetic tests, but this structure may reflect lithosphere that has experienced metasomatism or some other type of modification63. Additionally, we suggest that the northern WSB has been further altered by Cenozoic rifting (Frederick27 and references therein), leading to thinner lithosphere27,59,60 and higher GHF33,61,62 in this area (Anomaly I). Paleogene-Neogene lithospheric flexure and/or glacial erosion25 are not precluded by our interpretation, but these cannot explain the deep structure we image beneath the WSB.

In the ASB, our observations are best matched by a synthetic model that includes a thin, seismically fast (~100 km, +4%) lithospheric lid within the basin, underlain by a slow anomaly (−7%) that extends to at least 250–300 km depth (Figs. 2 and 3; Supplementary Fig. 9). Our lithospheric lid interpretation is consistent with those from prior studies. For example, Wiens et al.55 presented lithospheric thickness estimates based on seismic constraints32 and indicated 120–140 km thick lithosphere beneath the basin. Comparable estimates were obtained from results based on thermal isostasy33 (80–100 km) as well as from a recent joint inversion of seismic, gravity, topography, and mineral physics constraints34 (~120–160 km). We note, however, that lithospheric thicknesses ≥ ~150 km are too thick to match our observations; therefore, our findings best agree with the lower estimates provided by these previous investigations.

Our most notable finding is the pronounced slow velocity structure beneath the ASB (Figs. 2 and 3, Anomaly V), which has not been recognized by any previous seismic investigation. Early surface wave models from Ritzwoller et al.64 and Sieminski et al.65 provide some indication of reduced VS (~ −1.5%) between ~200 and 300 km depth in the ASB, though neither study interpreted this region. While their results were based on very limited station coverage, they may have partially resolved the same slow ASB structure that we observe. More recent tomographic models (Lloyd et al.32 and references therein) do not show seismically slow upper mantle beneath this portion of East Antarctica, but their seismic velocities in this region are somewhat slower than those in neighboring areas. This is illustrated, for example, in Fig. 4, which shows a comparison between our VS structure and that of Lloyd et al.32. At 200 km depth, the Lloyd et al.32 results indicate fast VS beneath the ASB as well as across the rest of Wilkes Land, but the VS in the vicinity of the basins and near the coast is somewhat lower compared to regions further inland. It is challenging to directly compare resolution between our model and that from Lloyd et al.32. Both models employ phase delay measurements with fairly comparable surface wave frequency content32, so we must expect that the differences shown in Fig. 4 are primarily due to differences between the spatial and temporal coverage of the respective datasets (Supplementary Note 2). That said, it is encouraging that Lloyd et al.32 show a relative VS decrease in the upper mantle beneath the ASB compared to other parts of East Antarctica (Fig. 4), and it is also worth noting that the Lloyd et al.32 model displays pronounced low velocities in the vicinity of the ASB near mantle transition zone depths. While this slow VS structure is deeper than that suggested by our model, both datasets are likely responding to a low-velocity anomaly beneath this region.

Our tomographic model is shown on the left, and the Lloyd et al.32 model (ANT-20) is shown on the right. Both have been plotted with the same color scale (at a given depth) and are shown in true geographic coordinates.

We interpret the slow ASB anomaly as thermally perturbed upper mantle. GHF estimates for East Antarctica, including the ASB, based on prior tomographic models assume uniform, fast velocities down to 250–350 km depth and average ~50 mW m−2, consistent with stable cratonic lithosphere31,62. However, GHF estimates based on other data types disagree and suggest higher heat flux in the ASB, consistent with our tomographic results and interpretation. For example, models derived from magnetic data61,66 suggest GHF values of 60–70 mW m−2 in the ASB region, while those based on thermal isostasy33 suggest GHF of ~90–100 mW m−2, perhaps even exceeding 120 mW m−2 in the area near Lake Vostok. Other lines of evidence also suggest thermal perturbation within the ASB upper mantle. For instance, the ASB area contains the greatest concentration of subglacial lakes in Antarctica27,67, and it has been argued that this requires a high geothermal contribution37. The presence of thermophilic bacteria in Lake Vostok also suggests geothermal activity68. High basal melt rates beneath the EAIS have been recognized within portions of the ASB (Pelle et al.69 and references therein), and these could be influenced by the underlying geologic structure as well. Additionally, O’Donnell & Nyblade40 argued that the high subglacial topography in central East Antarctica, such as that in the VSH, requires dynamic compensation. They suggested this could be associated with a mid- to lower-mantle source; however, that interpretation was dependent upon prior tomographic models that display fast upper mantle velocities throughout East Antarctica. Our results suggest that thermally perturbed upper mantle beneath the ASB could instead help to provide the required topographic compensation.

Far-field stresses associated with kinematics in the Southern Ocean may have reactivated a fault system within the ASB38 (Fig. 1), leading to Cenozoic extension, and this could explain the thin lithosphere advocated by our model. However, in this scenario, the slow ASB anomaly would be produced by decompression melting beneath the stretched lithosphere, a process that typically occurs only at depths above ~100 km70,71. This is inconsistent with our observations that show the slowest ASB velocities are between ~140 and 250 km depth. Alternatively, Baranov and Lobkovsky39 suggested that accelerated mantle flow and the development of local plumes led to late Cenozoic rift (re)activation within the ASB. Our model suggests that the slow ASB anomaly extends to at least 300–350 km depth, and while it may extend further, decreased resolution prevents us from constraining its full vertical extent. A localized mantle upwelling, thinning the ASB lithosphere from below, is not only consistent with our seismic observations but also with studies that advocate for geothermal activity beneath this portion of East Antarctica33,37,68.

It is also worth noting that the slow ASB anomaly could be linked to Anomaly IV at the inland end of the WSB (Figs. 2 and 3). This feature is similar to structure imaged by Zhang et al.60, though their slow velocities are concentrated at shallower depths (above 200 km) than what we observe and are underlain by a seismically fast region. Zhang et al.60 attributed their observations to a two-layer lithosphere with rift-induced cracks causing the upper, slow anomaly. While our results do not suggest such layered structure, they may still be consistent with rifting and/or thinned lithosphere. Using radar, gravity, and magnetic constraints, prior studies (Cianfarra and Maggi38 and references therein) have interpreted a series of rift segments throughout Wilkes Land (Fig. 1); however, the specific orientation and extent of these faults are unknown. Anomaly IV as well as the adjacent region with somewhat fast VS (Fig. 2) may denote where East Antarctic rifts separate the fast cratonic blocks beneath the BSH, VSH, and QML. Further, if a mantle upwelling is present beneath the ASB, as suggested above, the buoyant plume material could laterally spread beneath East Antarctica, channelized by the variable lithospheric structure, and be directed from the ASB region to the southern WSB, where it may pond beneath the thinned lithosphere72. The distribution of buoyant plume material could also broaden the lateral effects of dynamic compensation providing support for the high East Antarctic subglacial topography40.

Our newly imaged VS structure beneath Wilkes Land could have profound implications for ice-sheet models and the future behavior of the EAIS. Thin lithosphere and thermally perturbed upper mantle beneath the basins, especially the ASB, suggest increased GHF, which could dramatically impact EAIS basal melt rates. A recent study by McCormack et al.73 estimated the minimum GHF needed within the ASB to raise the basal temperature to the pressure melting point, taking ice thickness and flow velocities into account. As noted previously, the ASB area contains the greatest concentration of subglacial lakes in Antarctica27,67, which suggests that large portions of the basin should be at the pressure melting point74. McCormack et al.73 find a basin-average minimum GHF of 55 mW m−2, slightly higher than the GHF estimates provided by prior, tomographic-based models31,62, but they also emphasize that their estimates are spatially variable. Portions of the ASB require higher heat flow to reach the melting point, and the minimum GHF for these regions averages 96 mW m−2. If the slow VS anomaly we have imaged under the ASB is associated with a mantle upwelling, as we have suggested, the GHF beneath the ASB could be twice as high as that beneath “normal” continental environments19, meaning that basal conditions beneath the EAIS would readily exceed the pressure melting point. High basal melt rates can reduce ice-sheet stability and lead to accelerated ice discharge1,69,75,76.

The solid Earth response to ice mass change can also affect the stability of the EAIS. Lower viscosity mantle (resulting from increased temperature) and thinner elastic lithosphere lead to faster and more pronounced bedrock uplift when surface loading is reduced, which can slow or even prevent further ice-sheet retreat13. Using prior tomographic constraints32, Gomez et al.14 estimated an upper mantle viscosity of ~1022 Pa s beneath Wilkes Land and noted that this higher-than-average viscosity would limit bedrock uplift, thereby leading to greater ice loss in the WSB and ASB. However, our slow subglacial VS anomalies, particularly beneath the ASB, are similar to seismic velocities found beneath portions of West Antarctica by Lloyd et al.32, which are associated with much lower mantle viscosity (~1018 Pa s)14. This could result in greater bedrock uplift, perhaps generating ice-sheet stabilizing conditions, such as those suggested for portions of Wilkes Land3.

Ultimately, to resolve how the EAIS contributes to Antarctica’s mass balance1,2, the solid Earth structure beneath Wilkes Land needs to be considered. Accurate assessment of global sea-level is critical because it has profound impacts on coastal communities and infrastructure worldwide77. As such, we encourage future geophysical studies to more fully explore the lithospheric and mantle structure beneath East Antarctica and cryospheric modeling efforts to evaluate how the variable solid Earth structure, such as that suggested by our results, could alter prior estimates of EAIS behavior.

Methods

Data extraction and EGF processing

Following the frequency-time normalization method described in Shen et al.49, EGFs were extracted from ambient noise recorded by all openly available Antarctic seismic stations with latitudes below 60°S, including both permanent and temporary broadband deployments. The Shen et al.49 method has been shown to improve the SNR of EGFs when compared to the one-bit normalization process78, thereby allowing longer period signals to be obtained (Supplementary Figs. 1–4). It is worth noting that other approaches for EGF extraction also exist79, which can also provide improvements when compared to traditional one-bit normalization.

Vertical component ambient noise data were collected in 24-hour increments, plus a four-hour overlapping buffer, and the instrument response was removed from each day-long segment. Incomplete days with large gaps were removed from further processing. The data were then split into discrete time and frequency windows, were normalized, and any time periods coinciding with Mw 5.5+ earthquakes were removed. For each station-station pair, the day-long signals were cross-correlated, stacked, and filtered into nine broad, overlapping frequency bands (7–40, 25–55, 40–80, 60–100, 80–140, 110–180, 145–225, 180–260, and 220–340 s). That said, the two lowest bands (7–40 and 25–55 s) were not used in the inversion due to the computational demands needed to propagate short-period waveforms (see subsequent section). SNRs were computed for the remaining frequency bands, and then the EGFs were stacked in 30-day increments (i.e., monthly stacks). The monthly stacks from each station-station pair were used to calculate the phase delay variances that are used in the inversion.

High SNR long-period EGFs typically require at least one year of continuous data recorded by instruments with 120+ s corner periods47. We required the EGFs to have SNR > 5, and some of the Antarctic stations either did not operate long enough or were not optimal for the applied analysis; hence, they were not included in the inversion. Further, a small number of stations across Antarctica were intentionally omitted for later use in tomographic validation studies. Supplementary Tables 1–3 summarize the examined stations, highlighting those that contributed EGFs to the inversion and providing metrics to demonstrate data quality, and Supplementary Figs. 1–4 show example EGFs and station-to-station EGF distribution. Of the examined 309 stations, 133 returned at least one high-quality EGF for one or more of the examined period bands (Fig. 1). Those EGFs were then convolved with the same Gaussian source-time function used in the simulation (see below).

As noted in the main text, it is commonly presumed that noise correlation functions approximate the EGFs between stations41,42,43,44,45,46; however, this is not a perfect assumption. For example, strongly heterogeneous noise distribution, if present, can affect the resulting tomography80,81,82. In such cases, the heterogenous noise sources result in pronounced asymmetry in the correlation functions (here assumed to be EGFs). To address this concern, Supplementary Figs. 1–4 demonstrate the quality and symmetry of our EGFs, illustrating that the noise source distribution for our Antarctic study does not strongly suffer from this issue (see Supplementary Note 2 for further details).

Numerical waveform simulation

Using the same approach as Lloyd et al.32, the crustal component of our starting model was developed using the parameters (VP, VS, density) from CRUST1.053 but with thicknesses from An et al.31 to more accurately represent the crustal structure beneath Antarctica. This crustal structure was then underlain by the AK135 reference velocity model52. Our starting model was used to calculate synthetic waveforms, each of which is represented by a Gaussian source-time function (centered at 22.5 s, half-width 7.5 s) virtual source, emanating from one of the 133 examined stations (Fig. 1). The synthetic data were simulated in a spherical grid using a 3D finite-difference waveform propagation method that uses complex-frequency shifted, perfectly matched layers to prevent artificial reflections50,51.

As noted in the main text, the grid was rotated to the Equator to avoid the longitude singularity at the South Pole, and it has uniform, horizontal 0.1° lateral spacing. The computation time needed to model all station-to-station synthetics trades off with the requirement to maintain a dense enough grid to ensure the shortest period waveforms are accurately modeled (i.e., at least ~15 grid points/wavelength for surface waves)51. The employed 0.1° lateral spacing allows periods 40 s and longer to be accurately represented41,46. The vertical grid spacing is irregular and increases with depth, changing from ~1/3 the horizontal spacing at the surface and becoming equivalent to the horizontal spacing at ~100-km depth. This approach improves the computational efficiency for the waveform simulations as short-period Rayleigh waves (sensitive to shallow depths) require denser grid spacing to accurately represent their shorter wavelength signals while long-period, longer wavelength Rayleigh waves can be simulated with a more dispersed grid51.

Although we focus our interpretation on the Wilkes Land sector, our model domain extends from (23.5°S, 28.5°W) to (23.5°N, 28.5°E) in the rotated coordinate system, covering the entire continent of Antarctica. This is necessary to image the deeper seismic structure with long-period data, particularly since most of the high SNR EGFs are associated with East-Antarctic-to-West-Antarctic station pairs (Supplementary Fig. 1). The high-performance computing facilities at the Alabama Supercomputing Authority were used to model our synthetics and to run the waveform inversion.

Waveform inversion

The synthetic waveforms were cross-correlated with the long-period EGF data (convolved with the source-time function) to determine associated correlation coefficients and phase delays. Data with correlation coefficients ≥ 0.7 were used to constrain the model, and a maximum allowable phase delay was also enforced during each iteration (i.e., 25 s for the first iteration and 39 s for later iterations). Ellipticity corrections were calculated from the original, unrotated station locations. The phase delays were inverted for both VP and VS structure using a sparse, damped least-squares approach83; however, at the depths that we interpret, the waveforms are primarily sensitive to the VS structure. As the 3D velocity model was iteratively updated, the fit between the synthetic and observed waveforms improved; therefore, the number of convolved EGFs constraining the model increased as the inversion proceeded (Supplementary Fig. 5). Both compressional- and shear-wave sensitivity kernels (Supplementary Fig. 6), which were computed with a scattering integral technique54, were also updated and employed during each iteration of the inversion to ensure that spatial variation effects on the wavefields were accurately represented. Trade-off curves were used to select damping and smoothing parameters that minimized data variance while maintaining low model variance, and Supplementary Table 4 summarizes how these parameters varied with model iteration. Initially, our inversion was constrained with a subset of EGFs that had SNR > 6. This was done to robustly capture the overall regional structure. In later iterations, all EGFs with SNR > 5 were employed. The model converged after five iterations (Supplementary Fig. 5; Supplementary Table 4).

Evaluating model resolution

Resolution tests allow us to evaluate how well our model recovers the seismic structure within the study region, which is not uniform since the spatial distribution of the data is uneven. That said, the same amount of forward modeling and inversion computation time as that needed to create the tomographic model would be needed for each individual test case, meaning that generating a full suite of resolution tests is resource prohibitive. Therefore, as in Emry et al.47, our resolution tests show the recovery of synthetic input anomalies after a single iteration; specifically, we use the sensitivity kernels from the final model iteration, which again correspond to stations that had SNR > 5 at each examined period range. These tests demonstrate the reliability of our tomographic model and provide guidance for interpreting the results (Figs. 2 and 3; Supplementary Figs. 7–13).

Data availability

Most of the seismic data used in this study are openly available through the SAGE Data Management Center (http://ds.iris.edu/mda). Networks 5F and 5K (see Supplementary Table 1) were operated by The University of Strasbourg and The University of Tasmania, respectively, and were provided by the corresponding institutions. Supplementary Table 1 summarizes the seismic networks used in this study. Our final model is available via the EarthScope Earth Model Collaboration (https://doi.org/10.17611/DP/EMC.1) and the U.S. Antarctic Program Data Center (https://www.usap-dc.org/view/project/p0010139).

Code availability

The waveform simulation and inversion codes were developed by Dr. Yang Shen and colleagues at The University of Rhode Island and are available upon request.

References

Rignot, E. et al. Four decades of Antarctic ice sheet mass balance from 1979–2017. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 1095–1103 (2019).

Otosaka, I. N. et al. Mass balance of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets from 1992 to 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 1597–1616 (2023).

Morlighem, M. et al. Deep glacial troughs and stabilizing ridges unveiled beneath the margins of the Antarctic ice sheet. Nat. Geosci. 13, 132–137 (2020).

Cook, C. P. et al. Dynamic behaviour of the East Antarctic ice sheet during Pliocene warmth. Nat. Geosci. 6, 765–769 (2013).

Aitken, A. R. A. et al. Repeated large-scale retreat and advance of Totten Glacier indicated by inland bed erosion. Nature 533, 385–389 (2016).

Wilson, D. J. et al. Ice loss from the East Antarctic Ice Sheet during late Pleistocene interglacials. Nature 561, 383–386 (2018).

Crotti, I. et al. Wilkes subglacial basin ice sheet response to Southern Ocean warming during late Pleistocene interglacials. Nat. Comm. 13, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32847-3 (2022).

Iizuka, M. et al. Multiple episodes of ice loss from the Wilkes Subglacial Basin during the Last Interglacial. Nat. Comm. 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-37325-y (2023).

Gardner, A. S. et al. Increased West Antarctic and unchanged East Antarctic ice discharge over the last 7 years. Cryosphere 12, 521–547 (2018).

IMBIE team. Mass balance of the Antarctic ice sheet from 1992 to 2017. Nature 558, 219–222 (2018).

Whitehouse, P. L., Gomez, N., King, M.A. & Wiens, D.A. Solid Earth change and the evolution of the Antarctic ice sheet. Nat. Comm. 10, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-08068-y (2019).

Willens, M. O. et al. Globally consistent estimates of high-resolution Antarctic ice mass balance and spatially resolved glacial isostatic adjustment. Cryosphere 18, 775–790 (2024).

Ivins, E. R., van der Wal, W., Wiens, D. A., Lloyd, A. J. & Caron, L. Antarctic upper mantle rheology. Geol. Soc. Memoirs 56, 267–294 (2023).

Gomez, N. et al. The influence of realistic 3D mantle viscosity on Antarctica’s contribution to future global sea levels. Sci. Adv. 10, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adn1470 (2024).

Anandakrishnan, S., Blankenship, D. D., Alley, R. B. & Stoffa, P. L. Influence of subglacial geology on the position of a West Antarctic ice stream from seismic observations. Nature 394, 62–65 (1998).

Baranov, A., Morelli, A. & Chuvaev, A. ANTASed – An updated sediment model for Antarctica. Front. Earth Sci. 9, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2021.722699 (2021).

Morgan, P. Constraints on rift thermal processes from heat flow and uplift. Dev. Geotecton. 19, 277–298 (1983).

Bell, R. E. The role of subglacial water in ice-sheet mass balance. Nat. Geosci. 1, 297–304 (2008).

Seroussi, H., Ivins, E. R., Wiens, D. A. & Bondzio, J. Influence of a West Antarctic mantle plume on ice sheet basal conditions. J. Geophys. Res. 122, 7127–7155 (2017).

Han, H. K., Gomez, N., Pollard, D. & DeConto, R. Capturing the interactions between ice sheets, sea level and the solid Earth on a range of timescales: a new “time window” algorithm. Geodyn. Model. Develop. 15, 1355–1373 (2022).

Fretwell, P. et al. BEDMAP2: improved ice bed, surface and thickness datasets for Antarctica. Cryosphere 7, 375–393 (2013).

Steed, R. H. N. Structural interpretation of Wilkes Land, Antarctica in Antarctic Earth Science (eds Oliver, R.L., James, P.R. & Jago, J.B.) 567–572 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1983).

Stern, T. A. & ten Brink, U. S. Flexural uplift of the Transantarctic Mountains. J. Geophys. Res. 94, 10315–10330 (1989).

Ferraccioli, F., Armadillo, E., Jordan, T., Bozzo, E. & Corr, H. Aeromagentic exploration over the East Antarctic Ice Sheet: a new view of the Wilkes Subglacial Basin. Tectonophysics 478, 62–77 (2009).

Paxman, G. J. G. et al. The role of lithospheric flexure in the landscape evolution of the Wilkes Subglacial Basin and Transantarctic Mountains, East Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. 124, 812–829 (2019).

Baranov, A. & Morelli, A. The Moho depth map of the Antarctica region. Tectonophysics 609, 299–313 (2013).

Frederick, B. C. Submarine sedimentary basin analyses for the Aurora and Wilkes Subglacial Basins and the Sabrina Coast Continental Shelf, East Antarctica. PhD Dissert., Texas Univ., Austin (2015).

Chen, B., Haeger, C., Kaban, M. K. & Petrunin, A. G. Variations of the effective elastic thickness reveal tectonic fragmentation of the Antarctic lithosphere. Tectonophysics 746, 412–424 (2018).

Shen, W. et al. The crust and upper mantle structure of central and west Antarctica from Bayesian inversion of Rayleigh wave and receiver functions. J. Geophys. Res. 123, 7824–7849 (2018).

Li, L. & Aitken, A. R. A. Crustal heterogeneity of Antarctica signals spatially variable radiogenic heat production. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GL106201 (2024).

An, M. et al. S-velocity model and inferred Moho topography beneath the Antarctic plate from Rayleigh waves. J. Geophys. Res. 120, 359–383 (2015).

Lloyd, A. J. et al. Seismic structure of the Antarctic upper mantle imaged with adjoint tomography. J. Geophys. Res. 125, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JB017823 (2020).

Artemieva, I. M. Antarctica ice sheet basal melting enhanced by high mantle heat. Earth-Sci. Rev. 226, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.103954 (2022).

Haeger, C., Petrunin, A. G. & Kaban, M. K. Geothermal heat flow and thermal structure of the Antarctic lithosphere. Geochem., Geophys., Geosyst. 23, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GC010501 (2022).

Aitken, A. R. A. et al. The Australo-Antarctic Columbia to Gondwana transition. Gondwana Res. 29, 136–152 (2016).

Ferraccioli, F., Finn, C. & Jordan, T. East Antarctic rifting triggers uplift of the Gamburtsev Mountains. Nature 479, 388–392 (2011).

Tabacco, I. E., Cianfarra, P., Forieri, A., Salvini, F. & Zirizotti, A. Physiography and tectonic setting of the subglacial lake district between Vostok and Belgica subglacial highlands (Antarctica). Geophys. J. Int 165, 1029–1040 (2006).

Cianfarra, P. & Maggi, M. Cenozoic extension along the reactivated Aurora Fault System in the East Antarctic craton. Tectonophysics 703-704, 135–143 (2017).

Baranov, A. A. & Lobkovsky, L. I. The deepest depressions on land in Antarctica as a result of Cenosoic riftogenesis activation. Dokl. Earth Sci. 514 https://doi.org/10.1134/S1028334X23602420 (2023).

O’Donnell, J. P. & Nyblade, A. A. Antarctica’s hypsometry and crustal thickness: implications for the origin of anomalous topography in East Antarctica. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 388, 143–155 (2014).

Gao, H. & Shen, Y. Upper mantle structure of the Cascades from full-wave ambient noise tomography: Evidence for 3D mantle upwelling in the back-arc. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 390, 222–233 (2014).

Chen, M., Huang, H., Yao, H., van der Hilst, R. & Niu, F. Low wave speed zones in the crust beneath SE Tibet revealed by ambient noise adjoint tomography. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 334–340 (2014).

Savage, B., Covellone, B. M. & Shen, Y. Wave speed structure of the eastern North American margin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 459, 394–405 (2017).

Wang, K. et al. Refined crustal and uppermost mantle structure of southern California by ambient noise adjoint tomography. Geophys. J. Int 215, 844–863 (2018).

Lu, Y., Stehly, L., Brossier, R., Paul, A. & AlpArray Working Group. Imaging Alpine crust using ambient noise wave-equation tomography. Geophys. J. Int. 222, 69–85 (2020).

Covellone, B. M., Savage, B. & Shen, Y. Seismic wave speed structure of the Ontong Java Plateau. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 420, 140–150 (2015).

Emry, E. L., Shen, Y., Nyblade, A. A., Flinders, A. & Bao, X. Upper mantle structure in Africa from full-wave ambient noise tomography. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 20, 120–147 (2019).

Shapiro, N. M., Campillo, M., Stehly, L. & Ritzwoller, M. H. High-resolution surface-wave tomography from ambient seismic noise. Science 307, 1615–1618 (2005).

Shen, Y., Ren, Y., Gao, H. & Savage, B. An improved method to extract very-broadband empirical Green’s functions from ambient seismic noise. Bull. Seis. Soc. Am. 102, 1872–1877 (2012).

Zhang, W. & Shen, Y. Unsplit complex frequency-shifted PML implementation using auxiliary differential equations for seismic wave modeling. Geophysics75, T141–T154 (2010).

Zhang, W., Shen, Y. & Zhao, L. Three-dimensional anisotropic seismic wave modelling in spherical coordinates by a collocated-grid finite-difference method. Geophys. J. Int 188, 1359–1381 (2012).

Kennett, B. L. N., Engdahl, E. R. & Buland, R. Constraints on seismic velocities in the Earth from travel times. Geophys. J. Int 122, 108–124 (1995).

Laske, G., Masters, G., Ma, Z. & Pasyanos, M. Update on CRUST1.0—A 1-degree global model of Earth’s crust. Geophys. Res. Abstr. 15, 15 (2013).

Zhao, L., Jordan, T. H., Olsen, K. B. & Chen, P. Fréchet kernels for imaging regional Earth structure based on three-dimensional reference models. Bull. Seism. Soc. Am. 95, 2066–2080 (2005).

Wiens, D. A., Shen, W. & Lloyd, A. J. The seismic structure of the Antarctic upper mantle. Geol. Soc. Memoirs 56, 195–212 (2023).

Brenn, G. R., Hansen, S. E. & Park, Y. Variable thermal loading and flexural uplift along the Transantarctic Mountains, Antarctica. Geology 45, 463–466 (2017).

Goodge, J. W. & Fanning, C. M. 2.5 b.y. of punctuated Earth history as recorded in a single rock. Geology 27, 1007–1010 (1999).

Heeszel, D. S. et al. Rayleigh wave constraints on the structure and tectonic history of the Gamburtsev Subglacial Mountains, East Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 2138–2153 (2013).

White-Gaynor, A. L. et al. Heterogeneous upper mantle structure beneath the Ross Sea Embayment and Marie Byrd Land, West Antarctica, revealed by P-wave tomography. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 513, 40–50 (2019).

Zhang, H. et al. Upper mantle deformation of the Terror Rift and Northern Transantarctic Mountains in Antarctica: insight from P wave anisotropic tomography. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL086511 (2020).

Fox Maule, C., Purucker, M. E., Olsen, N. & Mosegaard, K. Heat flux anomalies in Antarctica revealed by satellite magnetic data. Science 309, 464–467 (2005).

Shen, W., Wiens, D. A., Lloyd, A. J. & Nyblade, A. A. A geothermal heat flux map of Antarctica empirically constrained by seismic structure. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL086955 (2020).

Rader, E. et al. Characterization and petrological constraints of the midlithospheric discontinuity. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 16, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GC005943 (2015).

Ritzwoller, M. H., Shapiro, N. M., Levshin, A. L. & Leahy, G. M. Crustal and upper mantle structure beneath Antarctica and surrounding oceans. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 30645–30670 (2001).

Sieminski, A., Debayle, E. & Lévêque, J. J. Seismic evidence for deep low-velocity anomalies in the transition zone beneath West Antarctica. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 216, 645–661 (2003).

Martos, Y. M. et al. Heat flux distribution of Antarctica unveiled. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 11417–11426 (2017).

Pattyn, F., Carter, S. P., & Thoma, M. Advances in modelling subglacial lakes and their interaction with the Antarctic ice sheet. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. 374, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2014.0296 (2016).

Bulat, S. A., Marie, D. & Petit, J.-R. Prospects for life in the subglacial Lake Vostok. Ice Snow 4, 92–96 (2012).

Pelle, T., Morlighem, M. & McCormack, F. S. Aurora Basin, the weak underbelly of East Antarctica. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL086821 (2020).

Nielsen, T. K. & Hopper, J. R. From rift to drift: Mantle melting during continental breakup. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 5, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GC00062 (2004).

Schmeling, H. Dynamic models of continental rifting with melt generation. TectonophysICS 480, 33–47 (2010).

Sleep, N. H. Mantle plumes from top to bottom. Earth Sci. Rev. 77, 231–271 (2006).

McCormack, F. S. et al. Fine-scale geothermal heat flow in Antarctica can increase simulated subglacial melt estimates. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL098549 (2022).

Pattyn, F. Antarctic subglacial conditions inferred from a hybrid ice sheet/ice stream model. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 295, 451–461 (2010).

Rignot, E. & Jacobs, S. S. Rapid bottom melting widespread near Antarctic ice sheet grounding lines. Science 296, 2020–2023 (2002).

Velicogna, I., Sutterley, T. C. & van den Broeke, M. R. Regional acceleration in ice mass loss from Greenland and Antarctica using GRACE time-variable gravity data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 8130–8137 (2014).

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge Univ. Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896 (2021).

Bensen, G. D. et al. Processing seismic ambient noise data to obtain reliable broadband surface wave dispersion measurements. Geophys. J. Int 169, 1239–1260 (2007).

Ventosa, S. & Schimmel, M. Broadband empirical Green’s function extraction with data adaptive phase correlations. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2023.3294302 (2023).

Basini, P. et al. The influence of nonuniform ambient noise on crustal tomography in Europe. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys. 14, 1471–1492 (2013).

Fichtner, A. Source-structure trade-offs in ambient noise correlations. Geophys. J. Int 202, 678–694 (2015).

Valero-Cano, E., Fichtner, E., Peter, D. & Mai, P. M. The impact of ambient noise sources in subsurface models estimated from noise correlation waveforms. Geophys. J. Int 239, 85–98 (2024).

Paige, C. C. & Saunders, M. A. LSQR: an algorithm for sparse linear equations and sparse least squares. ACM Trans. Math. Soft. 8, 43–71 (1982).

Wessel, P., Smith, W. H. F., Scharroo, R., Luis, J. & Wobbe, F. Generic mapping tools: improved version released. EOS Trans. AGU 94, 409–410 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Armelle Bernard and Anya Reading for providing the data from networks 5F and 5K, respectively, and three anonymous reviewers for their thorough critiques of our manuscript. This work was made possible, in part, by a grant of high performance computing resources and technical support from the Alabama Supercomputer Authority. Funding for this research was provided by the National Science Foundation (NSF; grants PLR-1643798, PLR-1643873, and OPP-1914698). The Seismological Facilities for the Advancement of Geoscience (SAGE) Data Services, which were used to access the waveforms and related metadata for this project, is funded under NSF Cooperative Support Agreement EAR-1851048. Some figures were generated with Generic Mapping Tools84.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.E.H. and E.L.E. equally contributed to conceptualization, funding acquisition, data curation and analysis, visualization, and writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Luca Dal Zilio and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hansen, S.E., Emry, E.L. East Antarctic tectonic basin structure and its implications for ice-sheet modeling and sea-level projections. Commun Earth Environ 6, 138 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02140-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02140-4

This article is cited by

-

The editors’ highlights for the five-year anniversary

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)