Abstract

We synthesise advances in the understanding of the physical processes that play a role in developing, intensifying, and terminating meteorological droughts. We focus on Australia, where new understanding of drought drivers across different climate regimes provides insights into drought processes elsewhere in the world. Drawing on observational, climate model and machine learning-based research, we conclude that meteorological drought develops and intensifies largely through an absence of synoptic processes responsible for strong moisture transport and heavy precipitation. The subsequent presence of these synoptic processes is key to drought termination. Large-scale modes of climate variability modulate drought through teleconnections, which alter drought-determining synoptic behaviour. On local scales, land surface processes play an important role in intensifying dry conditions and propagating meteorological drought through the hydrological cycle. In the future, Australia may experience longer and more intense droughts than have been observed in the instrumental record, although confidence in drought projections remains low. We propose a research agenda to address key knowledge gaps to improve the understanding, simulation and projection of drought in Australia and around the world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Drought is a severe and complex natural hazard. Globally, drought was the second leading cause of death of any weather-climate-water-related hazard between 1970 and 2019, with related economic losses exceeding $USD 250 billion1. Droughts threaten regional water and food security2,3,4, decrease economic growth5, cause long-term environmental damage6, and adversely impact human health and wellbeing7. Droughts can also be associated with other extreme events, including heat extremes as a result of higher temperatures during drought and forest fires due to vegetation drying8.

Australia is regularly affected by meteorological droughts due to its highly variable climate and ranks fifth in the world for economic damage caused by drought9. For example, the 2017–19 Tinderbox Drought that impacted eastern Australia led to substantial agricultural losses and threatened the water supply of Australia’s largest city and several regional townships10. The drought culminated in the Black Summer bushfires, the largest forest fires in Australia’s recorded history, leading to loss of lives and homes11. The economic impact from this drought, estimated at $AUD53 billion12, exposed Australia’s ongoing vulnerability to droughts.

There is high confidence that drought frequency and intensity will increase with global warming in some regions of the world13, with over 45% of the global land area projected to experience longer and more frequent meteorological droughts by the end of the 21st century14. However, the future direction of change in droughts due to climate change remains uncertain for most of Australia13. Knowledge of the physical processes associated with droughts will be increasingly required for prediction as anthropogenic climate change intensifies.

The susceptibility of Australia to drought impacts has driven efforts to improve understanding of drought processes, with the goal of increasing confidence in drought prediction and projection on seasonal to multi-year time scales. This research has moved beyond traditional studies that treat meteorological drought as a single, spatiotemporally homogenous event over a fixed region e.g. ref. 15. Instead, recent research has focussed on the nuances of the processes related to drought development, intensification and termination. Coordinated and interdisciplinary approaches have established a more holistic picture of drought processes, including information about large-scale ocean-atmosphere interactions, synoptic-scale processes, and land-atmosphere interactions and feedbacks. This information has come from a range of sources, including observations, palaeoclimate data, machine learning analyses, and climate model simulations.

This paper describes how this holistic picture of drought has evolved over the last decade by reviewing the advances in the understanding of the physical mechanisms that play a role in developing, intensifying and terminating meteorological droughts in Australia (Fig. 1). We recognise the importance of other drought types but focus on meteorological droughts—here considered as a period of unusually low precipitation that accumulates over a season or longer—to more thoroughly review the significant progress made in understanding this aspect of drought. We begin in the next section with a description of how Australian droughts can be characterised to set the scene on a complex and challenging research field. In Section 'Drought processes', we review the physical processes that cause droughts to develop, intensify and terminate and in Section 'Model assessment', we assess how well these processes are simulated in current generation climate models. In Section 'Drought predictability' we review existing capability in drought prediction, and outline expected future changes to Australian drought based on model projections in Section 'Droughts are changing'. In Section 'Drought mechanisms are changing', we consider how drought mechanisms may change in a future climate. Finally, considering the reviewed advances in our understanding of drought and remaining knowledge gaps, we outline priorities for future research in Section 'Future research directions'.

The character and variability of Australian droughts

Droughts vary in intensity, duration and spatial extent. Despite efforts to classify Australian droughts and find common drivers, a fundamental characteristic is that they generally differ from each other. Accordingly, although many indices have been proposed to define, monitor, and quantify drought, there is no single index that is universally applied16. Thus, discrepancies in drought definitions can introduce uncertainties in drought assessments17.

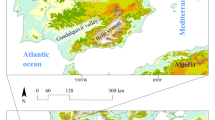

The character of droughts is highly variable across Australia, related to differences in their modulating processes and mean climate. For example, droughts in the tropical regions of northwest Australia (Fig. 2a) are typically associated with delays in the onset of the monsoon and/or failed wet seasons18 and have seen a marked reduction over past decades due to an increasing rainfall trend. Droughts in the semi-arid, Mediterranean climate of southwest Australia (Fig. 2b) have increased in frequency due to declining cool season rainfall—a change that has been attributed to anthropogenic climate change19,20. Droughts in the temperate to semi-arid regions of southeastern Australia (Fig. 2c) show high variability with no robust long-term trends. The impacts of drought can occur over various time scales, from sub-seasonal to multi-year and longer. Processes for seasonal or annual-scale meteorological droughts are often, though not always, well-defined, whereas the processes causing multi-year droughts often differ within the lifetime of the drought e.g. ref. 10.

a Time series of precipitation anomalies with drought periods marked in red (below the 15th percentile calculated over the full time series covering 1900–2023) for northwestern Australia (wet season DJF). Inset plot shows region location. b As in (a) but for southwestern Australia (cool season AMJJAS). c As in (a) but for the Murray-Darling Basin (annual). d Monthly precipitation anomalies in the Murray-Darling Basin during the period marked by the dashed box in (c); anomalies calculated and drought periods coloured, as in (a–c). e Annual precipitation anomalies (relative to 1900–2023) during the period marked by the dashed box in (c). Precipitation data is from the Australian Gridded Climate Dataset (AGCD) of gridded station observations141.

Drought metrics can be useful for monitoring and investigating the nature of droughts in terms of duration, intensity, frequency and spatial extent21 and are used to inform drought management strategies22. However, the spatiotemporal complexity of drought and its related processes means that it makes more sense to explore drought character in more nuanced ways than simple metrics that classify drought using a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Figure 2d shows monthly rainfall anomalies in the Murray-Darling Basin, Australia’s largest river basin, during the Tinderbox Drought10. These sequences demonstrate that droughts are rarely, if ever, homogeneously dry. Likewise, spatial patterns change (Fig. 2e). From a process perspective, this indicates that the relative role of the processes maintaining each drought are dynamic.

Evidence from palaeoclimate data and climate model simulations demonstrates that the observed historical period is not long enough to capture the full range of natural variability in Australian meteorological drought characteristics23,24 (Fig. 3). Historical meteorological drought frequency and intensity during the 20th century were within the range of natural (pre-industrial) climate variability of the last millennium in southwestern and eastern Australia23,24,25,26,27, although the severity of the 21st century Tinderbox Drought in southeastern Australia was likely increased by climate change10,28. In addition, palaeoclimate25,27 and climate model23 evidence suggest that Australia is naturally prone to ‘megadroughts’ lasting several decades—far exceeding the length of any drought experienced in the past 120 years. In southwestern Australia, O’Donnell et al.27 show that drought risk estimates based on observed historical observations likely underestimate the likelihood of severe droughts (i.e., droughts that are both long and intense).

Comparison of the range of multi-year drought lengths in the historical period versus longer (339-1100 years) time periods, for regions in and around the Murray-Darling Basin (MDB)—demonstrating that the historical period is too short to capture the full range of natural variability in MDB drought lengths. Each pair of density plots shows 1) the range of possible drought lengths in a model simulation (a) or palaeoclimate reconstruction (b, c) of rainfall over the MDB (in grey); and 2) the range of values for the same location in only the historical period, calculated using observations (in colours). The reconstructions and simulations target rainfall averaged over different periods and for different locations within the MDB, as shown on the inset map: a Annual total (January to December) rainfall averaged over the MDB28. b Annual (June–July) rainfall in Deniliquin, representative of rainfall in the upper Murray Basin24. c Cool season (April-September) rainfall averaged over the ‘Murray Basin’ Natural Resource Management region26. The equivalent rainfall amount values for the historical period are from AGCD, spanning 1900–2023141, and are calculated for the same locations and months as their associated modelled or palaeoclimate dataset. In all cases, multi-year droughts are defined as two or more consecutive years below median rainfall. Anomalies are calculated relative to the full length of each dataset. For reference, the vertical black line shows the notional length of the Millennium Drought (2000–2009). Note that under the quantitative definition used here to identify multi-year droughts, in some of the datasets shown, the Millennium Drought does not qualify as a single drought.

A fundamental challenge in characterising Australian meteorological droughts is that they are not necessarily continuous in time or space (Fig. 2). This has major implications for managing droughts. Attempts to classify droughts lead to the question of how best to choose an appropriate temporal and spatial scale and how to select the range of thresholds for defining drought. Drought characteristics are particularly sensitive to the choice of threshold29. These issues limit our ability to objectively identify drought development, intensification and termination. Research over recent years has challenged the traditional classification of Australian meteorological droughts, highlighted events that do not fit existing classifications, and identified that the processes related to multi-year drought may be very different over sequential years. This is compounded by multi-decadal trends in drought in some regions, such as southwestern and northwestern Australia (Fig. 2). Put simply, every drought is different and droughts change over time.

Drought processes

Variability in tropical ocean temperatures near Australia modulates interannual rainfall anomalies10,28,30, meteorological drought intensity, duration31 and frequency32. Major historical droughts in Australia have been connected to the occurrence of El Niño events33, as El Niño is strongly associated with rainfall deficits (Fig. 4a) and often precedes droughts in some parts of the country (Fig. 4b). Major droughts have also been connected to positive phases of the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD)34,35, Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO)35,36, positive phases of the Southern Annular Mode (SAM) in the cool season35,37, and negative phases of the SAM in the warm season38. However, there are many nuances to these relationships and it is now recognised that El Niño events are not always synonymous with droughts in Australia. For example, the rainfall anomalies that develop in Australia depend on the location of the warming along the equatorial Pacific39. Central Pacific El Niño events exert a stronger influence on Australian rainfall and drought than Eastern Pacific El Niño40,41. Several studies suggest a stronger influence from the Indian Ocean than the Pacific in some historical multi-year droughts in southeast Australia, including Tasmania34,35. Interactions between major modes of climate variability further modulate their influence on Australian rainfall and drought34,42,43,44,45, as observed in other regions such as the US46, Africa47, and South America48,49. For example, the 1982 eastern Australian drought involved the compounding dry conditions induced by El Niño, a positive phase of the IOD and a positive SAM35. SAM can, in turn be influenced by the southern polar stratospheric vortex. A weakening of the vortex in spring has been shown to promote the negative phase of SAM, which then promotes dry conditions over eastern Australia38, a condition also reported to influence drought in South America50. Conversely, La Niña events occurring during the Millennium Drought did not cause the drought to terminate in southern regions as the expected wet conditions were weakened by concurrent positive SAM and positive IOD events35,51.

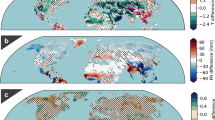

a Pearson correlation coefficient between the 12-month Standardised Precipitation Index (SPI-12) and the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) leading by 6 months over the period January 1901 - December 2022. Colours show correlation coefficients statistically significant at the 99% level based on a Student’s t-test. SPI-12 was calculated using monthly rainfall totals from AGCD141. The ONI was obtained from ref. 142 based on ERSSTv5. b Percentage of times that an El Niño event preceded a drought peak. Droughts were defined when SPI-12 < −1 and only droughts that persisted for at least 6 months were included. A drought peak is defined as the middle month of each drought event. El Niño events were identified when the ONI exceeded 0.5o for at least 3 consecutive months. The El Niño occurrence is counted between 6 months before SPI-12 < −1 and the drought peak. Over the period 1901–2022 the count is summed for all identified droughts and divided by the total number of droughts. Colours show significant frequencies of El Niño based on a binomial distribution at the 95% level. c Same as (b) but for La Niña. La Niña events were identified when the ONI remained below −0.5o for at least 3 consecutive months. d–f Same as (a–c) except for the Dipole Mode Index (DMI). The DMI143 was obtained from https://psl.noaa.gov/gcos_wgsp/Timeseries/DMI/ for the period 1901-2022. Positive (negative) IOD events were identified when the DMI was greater (less) than 0.5o for at least 3 consecutive months.

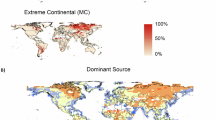

While the large-scale modes of climate variability influence moisture delivery to Australia44, the oceanic moisture sources for rainfall over the country are usually not directly connected to the focal regions of these climate modes52. Instead, large-scale climate modes influence droughts in Australia by modulating the location53 and frequency54,55 of the weather features that direct rainfall onto the Australian continent from local oceanic regions.

Recent research into the development of Australian droughts has seen a shift from associating drought solely with large-scale phenomena that are typically related to low rainfall towards viewing drought as an absence of climate processes that promote heavy rainfall over the country. Sustained periods lacking phases of La Niña and negative IOD influence the development and intensification of droughts in some parts of Australia34,56,57. The absence of these phases of large-scale variability allows droughts to develop by reducing the likelihood of heavy to extreme precipitation events. Across Australia, the absence of only around 10 moderate to heavy rainfall days in a year can lead to drought development58, with heavy precipitation events (daily precipitation exceeding 20 mm) responsible for a median of ~60% of the reduction in rainfall during drought development58. The reduced likelihood of heavy rainfall events in years without La Niña or negative IOD events means that the accumulated rainfall deficit over eastern and northern Australia tends to grow larger as the length of time since a La Niña or negative IOD event grows57 (Fig. 5). This shift in thinking recognises that dry climate conditions are a pervasive characteristic of much of the Australian continent, and that episodic wet events are critical in preventing the establishment of drought conditions.

Rainfall anomalies accumulated over (a) 12 months, (b) 12–24 months and (c) at least 36 months since the last La Niña or negative IOD month over 1901–2022. La Niña and negative IOD events, and corresponding rainfall anomalies, calculated as for Fig. 4.

Once drought conditions are established, land-atmosphere feedbacks play an important role in intensifying and sustaining drought conditions and in expanding drought-affected areas (Fig. 6). Terrestrial evapotranspiration typically contributes up to 21% of Australian seasonal rainfall through precipitation recycling52. Reduced recycling amplified southeastern droughts by up to 6% over 1979–201359. During the 2017–2019 Tinderbox Drought, terrestrial precipitation recycling declined by 25–40%, leading to the progressive intensification of the drought60. Soil moisture anomalies can also facilitate the extension of drought areas through land desiccation in upwind regions. The dry anomaly reduces the terrestrial-sourced rainfall received in downwind regions and ultimately leads to the self-propagation of droughts, most notably in regions such as southern Africa and Australia61,62. Such an effect led to an escalation of the 2005 drought in northwestern and central Australia by reducing precipitation in downwind regions by 18%61 and led to the amplification of droughts in southeastern Australia59. Large-scale land cover change has also been linked to reduced rainfall in southwestern Australia via reduced surface roughness, however this is likely a secondary influence63,64. In the monsoonal northwest of Australia, soil moisture-rainfall feedbacks and wind-evaporation feedbacks are key to maintaining negative rainfall anomalies65.

Mechanisms influencing Australian drought (a) development and intensification, and (b) termination. “Anthropogenic forcing” refers to the potential dynamic and thermodynamic changes to each mechanism due to human-caused climate change. IOD Indian Ocean Dipole. MJO Madden-Julian Oscillation. IPO Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation. SAM Southern Annular Mode. SSTs sea surface temperatures. WCBs warm conveyor belts.

Droughts are extreme climate events that can persist for months to years, but it is synoptic weather systems acting on daily timescales that bring drought-terminating rainfall. Only a small number of heavy rainfall events, equivalent to ~2–10 days per year, are needed to terminate Australian droughts58. Extreme rainfall (daily precipitation exceeding the local 98th percentile) events in southeast Australia are responsible for ~13% of total rainfall during drought terminations66. Similarly, heavy rainfall events (daily precipitation exceeding 20 mm) are responsible for ~70% of the precipitation surplus during drought terminations across Australia58.

The weather systems that generate drought-terminating rainfall are those that produce strong ascent and an enhanced transport of moisture into a drought-affected region (Fig. 6b). Vertically-organised deep cyclones, those that extend from the lower to the mid- and upper-troposphere, are responsible for a substantial proportion of mean and extreme rainfall in southern Australia67. When a deep cyclone over southeast Australia co-occurs with an adjacent anticyclone over the Tasman Sea, the anticyclone enhances the transport of oceanic moisture toward the continent, substantially increasing the likelihood of extreme rainfall over southeast Australia66. Rainfall from this synoptic mechanism was notably absent during droughts and present during drought termination over the period 1959-202166. This synoptic set-up has been shown to be more common during La Niña events54, providing a connection between large-scale climate modes and drought-terminating rainfall processes. Warm conveyor belts (WCBs) and potential vorticity (PV) streamers also provide the moisture transport and ascent mechanisms that are crucial to generate heavy to extreme rainfall over the Murray-Darling Basin68. WCBs were less frequent and intense and faster-moving during the development and intensification of the Millennium Drought, and more frequent and intense and slower-moving during the drought’s termination69. The slow-moving WCBs are explained by a dynamic interaction between divergent wind from the outflow of the WCB and anticyclonic PV anomalies over the Tasman Sea. The role of the speed of weather systems in rainfall has also been highlighted by Barnes et al.70, who found that slow-moving cut-off lows produce more rainfall over the eastern Australian seaboard than fast-moving systems. Reduced rainfall during the southeast Australian Tinderbox Drought was associated with a decreased frequency and intensity of rainfall associated with WCBs and PV streamers10, decreased frequency of deep cyclones with an adjacent anticyclone66, as well as a record-low number of cyclones across southern Australia71. In the southern parts of southeast Australia, including Tasmania, dry extremes are associated with blocking high-pressure systems embedded within large-scale wave train patterns72, the decay of which has been shown to play a role in ending droughts in southeast South America73. In southwestern Australia, a decreased frequency of troughs associated with very wet conditions has been linked to a long-term rainfall decline74 and may play a role in reducing drought termination in this region. In tropical northern Australia, drier conditions can be alleviated by eastward-propagating tropical wind and convection anomalies associated with the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO), with compounding influence from ENSO75 or monsoon lows76. These weather systems act in concert with large-scale modes of climate variability and land surface processes to cause droughts to develop and terminate (Fig. 6).

Model assessment

It is critical that the models used to predict the current and future behaviour of droughts are skilful. Across the world, CMIP5/6 global climate models perform well in capturing seasonal meteorological drought duration14,77. However, many models still simulate rainfall that is too frequent and light78,79 and dry spells that are not persistent enough to produce extended periods of drought80,81. In Australia specifically, biases in both mean rainfall82 and decadal-scale variability83 limit the ability of climate models to simulate multi-year droughts.

Global climate model representation of large-scale climate drivers that influence drought in Australia, including ENSO and IOD, has improved to some extent84, but more evaluation for drought-specific mechanisms is needed. Representation of large-scale climate drivers has improved through increased spatial resolution85,86 and further enhancing the representation of physical processes can strengthen this improvement87, particularly in the Pacific region where substantial model biases remain in the pattern of warming88 and teleconnections to Australia89. Model skill in capturing combinations of modes which may strengthen rainfall anomalies (e.g. El Niño, positive IOD, negative SAM and inactive MJO simultaneously), should be further evaluated. Conversely, synoptic circulation features such as low pressure systems associated with southern Australian wet and dry extremes were found to be reasonably well represented in some global climate models90.

Regional modelling at higher spatial resolution can capture some drought characteristics more accurately than global models. In eastern Australia, which has regions of complex terrain, recent regional climate model simulations show improved representation of dry day frequency and mean rainfall relative to coarser global models91 and show promise in improving simulated ENSO and IOD teleconnections to Australian rainfall92. Yet some regional models underestimate the frequency of co-occurring deep cyclones and an adjacent anticyclone, systems particularly important in terminating southeast Australian droughts66, driven by an underestimation of the frequency of upper-level cyclones67. In general, improvements gained from regional models vary by location and season and are not systematic93 and do not necessarily resolve shortcomings in the coarser resolution driving global model. Indeed, computational constraints mean regional models tend to be limited in their spatial domain and cannot cover all relevant spatial domains, such as climate mode centres of focus or locations of storm tracks, precluding explicit representation of these processes at higher resolution in regional modelling systems. Downscaling rainfall with machine learning offers a promising avenue to improve simulated rainfall characteristics at a much lower computational cost than regional climate models94, but this area is still in its infancy. Frameworks to benchmark regional model fidelity have been developed95 but evaluation specifically for drought remains limited, with most studies concentrating on mean or extreme rainfall metrics.

Land models within climate modelling systems also exhibit biases, which may have an influence on meteorological drought through land-atmosphere feedbacks. In particular, evapotranspiration is systematically underestimated by many models during seasonal-scale droughts96. These biases may be partly driving biases in atmospheric humidity in CMIP6 global climate models97, with consequences for rainfall generation.

Acknowledging these existing modelling gaps and drawing upon recent advances in process understanding highlighted in the previous section, we propose a suite of physical features of the climate system that models need to be able to represent to realistically simulate drought characteristics and processes (Table 1). Future research dedicated to model evaluation for drought processes will enable quantification of these features, allowing them to be used as shared model evaluation targets.

Drought predictability

Systematic assessment of predictability for Australian drought development, intensification and termination is lacking. Ultimately, improving drought predictability depends on integrating the varying spatiotemporal scales and domains of the processes that determine each stage of drought (Fig. 6).

The persistence of large-scale climate modes in a particular phase offers some predictability to drought development and termination across northern, eastern and southern Australia at seasonal scales57,98, with ENSO being a dominant factor that is used to communicate drought risk99,100. However, not all El Niño events lead to drought4,34,35 and not all La Niña events lead to very wet conditions42,101. Moreover, even in regions where rainfall is tightly coupled to a known mode of variability, such as the SAM in southwestern Australia98 or the MJO in northern Australia102, predictability of drought development is limited to around 1–3 months98,103. Ultimately, large-scale modes of variability are insufficient on their own to predict drought development103,104 but remain the key source of predictability beyond numerical weather prediction time scales. Poor outlooks in ACCESS-S2 (Australia’s operational seasonal prediction system105) were found to occur during seasons where intraseasonal climate modes (such as the MJO) greatly enhance or suppress precipitation more than a month after forecasts are initialised42. Existing evidence also indicates drought termination predictability may be limited in current-generation climate models, given the lack of predictability of heavy rainfall beyond a few weeks106. However, a systematic evaluation of climate models for drought-relevant synoptic features and the impact of model bias on drought predictability has yet to be carried out. Together, these pose a major challenge to the prediction of drought characteristics beyond traditional weather prediction timescales. To date, there has been limited focussed research on Australian drought prediction in seasonal prediction systems, but even small advances in drought predictability could have major benefits.

Recent advances in machine learning have been applied to drought prediction by drawing together the multiple remote and local factors that modulate drought risk. Lagged climatic indices are commonly exploited for their predictive performance, with ENSO a common predictor. ENSO provides rainfall predictability in northern and southeastern Australia during austral spring, reaching up to 60% of explained variability, but is significantly lower in other seasons and regions104. Additional large-scale climate indices, such as the IOD and the SAM, have been shown to improve predictive accuracy up to three months in advance for eastern Australian droughts107. Documented drought impacts, combined with multivariate machine learning methods, offer a means to predict droughts even without extreme anomalies in a single climate variable108. Moreover, multivariate machine learning methods have been used to forecast drought indices from prevailing climate conditions up to three months lead108. By incorporating real-time observations from satellites, machine learning can be deployed for seasonal and subseasonal drought forecasts. Machine learning could additionally be leveraged to generate a large ensemble of regional rainfall projections, enhancing our ability to quantify the variability in drought characteristics in the future109.

Droughts are changing

Historical and palaeoclimate evidence suggest that anthropogenic climate change may already be altering Australian droughts. The Tinderbox Drought was the first historical drought in Australia to exceed the range of natural variability of drought intensity10,28, suggesting an anthropogenic contribution to the severity of the drought. The drought intensity was likely exacerbated by the 2019 extreme positive IOD event which was also beyond the range of anticipated natural variability28. Climate model simulations suggest that anthropogenic forcing intensified the rainfall deficits in the Tinderbox Drought by ~18% with an interquartile range of −13.3 to 34.9%10. Anthropogenic climate change is also influencing drought duration. During the 20th century, droughts in eastern and southwestern Australia were, on average, longer than in the pre-industrial period23. The long-term decline in cool season rainfall in southwestern Australia since the 1970s, which has led to persistent dry conditions and impacted water resources, has also been partly attributed to anthropogenic climate change19,20.

Global climate model simulations suggest that climate change will continue to increase the risk of meteorological drought across southern Australia into the future14,32,110,111. A robust increase in seasonal drought duration and frequency is projected in southwest and parts of southeast Australia under a very high emissions scenario (SSP5-8.5)14. The intensity of seasonal droughts is also projected to worsen but with large inter-model spread in the magnitude of the future change14. Projected increases in rainfall variability will amplify these drought changes, leading to greater increases in drought intensity and duration than expected from changes in long-term mean rainfall alone14. Southwestern and southeastern Australia are also projected to spend more time under multi-year drought conditions32,112, with longer and more intense droughts110. The potential for decadal to multi-decadal droughts in Australia e.g. refs. 23,27, combined with climate change-driven drying trends across southern Australia82,113, point towards the possibility of increasing risk of long-lasting droughts and aridity in the future. Furthermore, as droughts propagate through natural and human systems, their impacts are likely to be exacerbated by climate change. Risks to water resources and agriculture are likely to increase non-linearly with higher degrees of global warming114.

Despite projections overall pointing towards increasing drought risk over southern Australia, future drought changes remain highly uncertain in some key agricultural and highly-populated regions of Australia. Low model agreement dampens confidence in future drought changes across parts of the Murray-Darling Basin, northern Australia and New South Wales (Australia’s most populous state)14,110. Downscaled regional projections do not currently improve certainty for these regions, with individual studies pointing to both decreasing and increasing incidence of drought depending on the modelling method used111,115,116.

Drought mechanisms are changing

There is evidence that some drought-promoting phases of modes of climate variability will become more frequent this century, providing insights into likely future drought risk even where rainfall changes are poorly modelled. Palaeoclimate reconstructions, observations and future projections provide consistent evidence that strong positive IOD events are becoming more frequent in a warming world117,118. The frequency of positive IOD events is projected to imminently exceed the range of natural variability over the last millennium117,119. There are also indications from palaeoclimate evidence120,121 and model simulations122 that the swings between El Niño and La Niña states are becoming larger in a warming world, with an increasing occurrence of extreme ENSO events123. These events are simulated to have larger rainfall impacts124,125 such that future El Niño events may lead to drier conditions in southern Australia than those experienced in the 20th century126. However, large climate model ensembles point to considerable uncertainties in future ENSO changes both due to differences across climate models in simulating ENSO dynamics and large interannual variability masking forced changes127. Discrepancy between models and observations on the mean-state trend in the tropical Pacific also presents a key uncertainty in future ENSO projections that needs to be resolved88. Positive trends in the SAM during summer have recently paused due to recovery of the ozone hole128 meaning that the tendency for summer SAM trends to ameliorate droughts in eastern Australia is no longer increasing. In contrast, greenhouse gas-driven positive trends in winter SAM are expected to continue this century129. These are linked to projected cool season drying trends over southern Australia82, particularly southwestern Australia19, and are expected to increase aridity and the likelihood of meteorological droughts developing. The confluence of multiple changes in climate variability towards states that promote drought development in southern Australia also implies that future droughts may be more likely to involve the compounding effects of co-occurring climate drivers.

Evidence also points towards future changes in the synoptic-scale weather systems that bring drought-terminating rainfall to southern Australia. In southwestern Australia, a decline in the number of troughs has been linked to the long-term decline in rainfall since the 1970s74. The downward trend in the number of troughs is projected to continue into the future130, indicating a decline in the opportunity for drought-terminating rainfall in this region. In southeastern Australia, model projections indicate no change in the frequency of summer WCBs131 but do indicate that deep cyclones with an adjacent anticyclone may become less frequent by the end of the 21st century66, suggesting a decline in drought-terminating rainfall from this weather system. Furthermore, there is model and empirical evidence for more frequent La Niña events132 and multi-year La Niña events133,134 that could increase the availability of atmospheric moisture in the Australian region44. However, connection to the synoptic processes required to deliver this moisture as drought-terminating rainfall is currently unclear. Together, the evidence for current and future changes in the large-scale modes of climate variability towards states that promote drought development, as well as projected declines in the weather systems that deliver drought-terminating rain to southern Australia, point towards the urgency of future research that improves early warning and preparedness for droughts.

Future research directions

Drought occurs frequently in Australia. The awareness that some pre-20th century droughts lasted longer and were more severe than those in the instrumental record further highlights Australia’s vulnerability to drought and the importance of anticipating possible changes to drought characteristics over coming decades. Recent high-impact droughts, together with the identified changes to risk of future drought, have motivated research to better understand the causes of drought in more nuanced ways than available previously. However, Australia is not the only region at risk from high-impact droughts and so the new approaches that are recognised in this review and the future research priorities outlined below should also be considered by researchers interested in drought elsewhere.

We now present four overarching priorities for drought research. While these are motivated by Australian drought research, the recommendations may inform drought research in other regions.

Every drought is different

Droughts in Australia are complex events whose drivers evolve over time. They involve sequential and compounding effects including large-scale modes of climate variability that influence the likelihood of drought-terminating rainfall events, as well as local feedback processes that can intensify drought impacts (Fig. 6). Searching for simple explanations for drought in Australia is unlikely to lead to the understanding required to improve predictability and provide strategies for drought management. It is likely that different characteristics of drought will change in different ways as warming intensifies, with changes manifesting differently across the continent. This is likely true elsewhere around the globe135.

Rather than seeking a simple explanation for drought, we argue that complexity should be embraced with the acknowledgment that there are major limits in our capacity to predict drought onset, intensification and termination. Straightforward narratives that attribute drought to a single process over its lifespan are too simple and misleading to be useful. Our analysis suggests value in a multidisciplinary approach that includes ocean scientists, atmospheric dynamicists and land scientists. In short, a more nuanced understanding and communication of drought risk in a changing climate needs to be established. Communication of drought events should not be overly simplified, especially given the risk that an event of a single driver (e.g. El Niño) could be associated with a drought in one instance and not in another.

A greater focus on drought termination

Recent research has begun to reframe drought as the absence of conditions conducive to heavy or extreme rainfall that would otherwise terminate the drought57,58,66,68. Synoptic systems responsible for heavy rainfall have also been identified as important for determining drought and drought termination in other regions, such as the US136,137 and South Africa138. Perhaps surprisingly, only a handful of synoptic-scale heavy rainfall events make the difference between drought and non-drought conditions in Australia58,66,69.

These results suggest that understanding droughts and drought termination requires a focus on atmospheric dynamics and synoptic-scale processes. This includes understanding the interactions between synoptic and larger-scale processes, such as how synoptic behaviour is modulated by ocean-atmosphere modes of variability and their interactions. Also needed is an understanding of the interactions between synoptic and smaller-scale land surface processes, such as land-atmosphere feedbacks and longer-term CO2 effects on greening and water use efficiency. Key questions require knowledge of how these cross-scale processes affect the likelihood of rainfall over drought-prone regions.

Drought termination brings the risk of flooding and the opportunity to replenish depleted water stores. Understanding and preparing for these risks and opportunities will require a deeper understanding of climate-weather-catchment interactions and how they are being shaped by anthropogenic changes.

A new lens on climate and regional modelling capability

The processes a climate model must be able to represent, with the necessary degree of skill, to reliably simulate Australian droughts is particularly challenging if the perspective changes from 'what causes droughts' to 'what terminates droughts'. Capturing annual or seasonal rainfall is challenging, but capturing whether a handful of major rainfall events do or do not occur over a specific region coincident with a drought is much more difficult.

Although CMIP6-era global climate models simulate meteorological drought duration better than previous eras, biases in rainfall mean and variability continue to affect simulated drought characteristics. Fundamentally, we need better models. Selecting models with lower biases e.g. ref. 82 is a short-term solution, but evaluating models to determine why modelled rainfall is biased is a priority. We propose a fundamental pathway through evaluation of key physical processes within the climate system that have been identified as important to the development, intensification and termination of meteorological drought (Table 1).

The requirement of high model spatial resolution to resolve drought-relevant mechanisms combined with the requirement of long or large ensembles of simulations to sample drought-relevant variability poses a substantial challenge to drought research. Yet predictions and projections of future droughts are fundamentally important to the future economic prosperity and health of Australia. Ultimately, both robust predictions and projections of meteorological drought need better models than we currently have. Improving models likely requires a sustained investment and coordinated activities in model development alongside higher spatial resolution.

Expansion of instrumental and palaeoclimate observations

Empirical observations of past and present hydroclimate are needed to further process understanding and validate climate models over a range of spatial and temporal scales, from observations of sub-daily processes within the atmosphere, ocean and land, to palaeoclimate proxy records spanning millennia. An expansion of high-resolution observations including surface and ground water stores, evapotranspiration, radiation, winds, boundary layer and tropospheric processes and ocean temperatures, would aid our efforts. Additionally, there are scarce high-resolution multi-centennial records of past climate, particularly on the Australian mainland. Augmenting the coverage of palaeoclimate records and reconstructions of past hydroclimate in Australia would, therefore also be of benefit. There are newly emerging opportunities to do this, for example with multi-proxy sub-annually to annually-resolved dendrochonological records developed from tree and shrub species, including locations on the Australian mainland27,139, monthly-resolution multi-centennial coral records from nearby regions with strong SST-teleconnections to the moisture transport pathways for land-based rainfall26,44, and more distant ice core records spanning multiple millennia where shared synoptic processes link rainfall deficits in parts of Australia to accumulation and chemical impurities in Antarctic snowfall140.

In summary, rainfall in a drought-prone region like Australia relies on the transport of moisture from nearby oceans. Weather systems that enhance this transport and combine with strong ascent are needed to terminate droughts and allow a region to persist in a non-drought state. These heavy rainfall-generating processes are linked to atmospheric circulation across scales and interactions with the ocean and land. This paradigm shift away from the traditional explanation of drought as simply a period of abnormally low water availability to an understanding of the importance of heavy rainfall changes how droughts may be assessed globally. It means that to better understand drought in other parts of the world, we need to understand the causes of variability in the conditions conducive to heavy rainfall in each region, acknowledging that the causative mechanisms may change between and within droughts. Finally, the physical mechanisms involved in drought development, intensification and termination must be adequately represented in models of the climate system and underpinned by observations of past and present hydroclimate. Improved confidence in predictions and projections of drought will strengthen regional drought planning and enable stakeholders across industries to better prepare for future droughts.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the provided figures are cited within the paper.

References

World Meteorological Organisation. WMO Atlas of Mortality and Economic Losses from Weather, Climate and Water Extremes (1970–2019). https://library.wmo.int/records/item/57564-wmo-atlas-of-mortality-and-economic-losses-from-weather-climate-and-water-extremes-1970-2019#.YS4KedP7TX0 (2021).

Sousa, P. M., Blamey, R. C., Reason, C. J. C., Ramos, A. M. & Trigo, R. M. The ‘Day Zero’ Cape Town drought and the poleward migration of moisture corridors. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 124025 (2018).

Lesk, C., Rowhani, P. & Ramankutty, N. Influence of extreme weather disasters on global crop production. Nature 529, 84–87 (2016).

Vogel, E. et al. The effects of climate extremes on global agricultural yields. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 054010 (2019).

Zaveri, E. D., Damania, R. & Engle, N. L. Droughts and Deficits—Summary Evidence of the Global Impact on Economic Growth. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099640306142317412/IDU03b9849a60d86404b600bc480bef6082a760a (2023).

Peterson, T. J., Saft, M., Peel, M. C. & John, A. Watersheds may not recover from drought. Science 372, 745–749 (2021).

Vins, H., Bell, J., Saha, S. & Hess, J. J. The mental health outcomes of drought: a systematic review and causal process diagram. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12, 13251–13275 (2015).

Jyoteeshkumar reddy, P., Sharples, J. J., Lewis, S. C. & Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S. E. Modulating influence of drought on the synergy between heatwaves and dead fine fuel moisture content of bushfire fuels in the Southeast Australian region. Weather Clim. Extrem. 31, 100300 (2021).

González Tánago, I., Urquijo, J., Blauhut, V., Villarroya, F. & De Stefano, L. Learning from experience: a systematic review of assessments of vulnerability to drought. Nat. Hazards 80, 951–973 (2016).

Devanand, A. et al. Australia’s Tinderbox drought: an extreme natural event likely worsened by human-caused climate change. Sci. Adv. 10, eadj3460 (2024).

Boer, M. M., de Dios, V. R. & Bradstock, R. A. Unprecedented Burn Area of Australian Mega Forest Fires. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 171–172 (2020).

Wittwer, G. & Waschik, R. Estimating the economic impacts of the 2017–2019 drought and 2019–2020 bushfires on regional NSW and the rest of Australia. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 65, 918–936 (2021).

Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. in Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (ed. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)) 1513–1766 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.013.

Ukkola, A. M., Kauwe, M. G. D., Roderick, M. L., Abramowitz, G. & Pitman, A. J. Robust future changes in meteorological drought in CMIP6 projections despite uncertainty in precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087820 (2020).

Nicholls, N. The changing nature of Australian Droughts. Clim. Change 63, 323–336 (2004).

Zargar, A., Sadiq, R., Naser, B. & Khan, F. I. A review of drought indices. Environ. Rev. 19, 333–349 (2011).

Hoffmann, D., Gallant, A. J. E. & Arblaster, J. M. Uncertainties in drought from index and data selection. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, e2019JD031946 (2020).

Lisonbee, J., Ribbe, J., Otkin, J. A. & Pudmenzky, C. Wet season rainfall onset and flash drought: the case of the northern Australian wet season. Int. J. Climatol. 42, 6499–6514 (2022).

Delworth, T. L. & Zeng, F. Regional rainfall decline in Australia attributed to anthropogenic greenhouse gases and ozone levels. Nat. Geosci. 7, 583–587 (2014).

Rauniyar, S. P., Hope, P., Power, S. B., Grose, M. & Jones, D. The role of internal variability and external forcing on southwestern Australian rainfall: prospects for very wet or dry years. Sci. Rep. 13, 21578 (2023).

Mishra, A. K. & Singh, V. P. A review of drought concepts. J. Hydrol. 391, 202–216 (2010).

Steinemann, A., Iacobellis, S. F. & Cayan, D. R. Developing and evaluating drought indicators for decision-making. https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-14-0234.1 (2015).

Falster, G. M., Wright, N. M., Abram, N. J., Ukkola, A. M. & Henley, B. J. Potential for historically unprecedented Australian droughts from natural variability and climate change. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 28, 1383–1401 (2024).

Ho, M., Kiem, A. S. & Verdon-Kidd, D. C. A paleoclimate rainfall reconstruction in the Murray-Darling Basin (MDB), Australia: 2. Assessing hydroclimatic risk using paleoclimate records of wet and dry epochs. Water Resour. Res. 51, 8380–8396 (2015).

Vance, T. R., Roberts, J. L., Plummer, C. T., Kiem, A. S. & van Ommen, T. D. Interdecadal Pacific variability and eastern Australian megadroughts over the last millennium. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 129–137 (2015).

Freund, M, Henley, B. J, Karoly, D. J, Allen, K. J & Baker, P. J Multi-century cool- and warm-season rainfall reconstructions for Australia’s major climatic regions. Climate 13, 1751–1770 (2017).

O’Donnell, A. J., McCaw, W. L., Cook, E. R. & Grierson, P. F. Megadroughts and pluvials in southwest Australia: 1350–2017 CE. Clim. Dyn. 57, 1817–1831 (2021).

Falster, G., Coats, S. & Abram, N. How unusual was Australia’s 2017–2019 Tinderbox Drought? Weather Clim. Extrem. 100734 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2024.100734 (2024).

Gibson, A. J. et al. Characterising the seasonal nature of meteorological drought onset and termination across Australia. JSHESS https://doi.org/10.1071/ES21009 (2022).

Van Rensch, P., Gallant, A. J. E., Cai, W. & Nicholls, N. Evidence of local sea surface temperatures overriding the Southeast Australian rainfall response to the 1997– 1998 El Niño. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 9449–9456 (2015).

Taschetto, A. S., Gupta, A. S., Ummenhofer, C. C. & England, M. H. Can Australian multiyear droughts and wet spells be generated in the absence of oceanic variability? J. Clim. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-15-0694.1 (2016).

Delage, F. P. D. & Power, S. B. The impact of global warming and the El Niño-Southern Oscillation on seasonal precipitation extremes in Australia. Clim. Dyn. 54, 4367–4377 (2020).

Van Dijk, A. I. J. M. et al. The millennium drought in southeast australia (2001-2009): natural and human causes and implications for water resources, ecosystems, economy, and society. Water Resour. Res. 49, 1040–1057 (2013).

Ummenhofer, C. C. et al. What Causes Southeast Australia’s Worst Droughts? Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, (2009).

Verdon-Kidd, D. C. & Kiem, A. S. Nature and causes of protracted droughts in southeast Australia: Comparison between the Federation, WWII, and Big Dry droughts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, (2009).

Power, S., Casey, T., Folland, C., Colman, A. & Mehta, V. Inter-decadal modulation of the impact of ENSO on Australia. Clim. Dyn. 15, 319–324 (1999).

Cai, W., van Rensch, P., Borlace, S. & Cowan, T. Does the Southern Annular Mode contribute to the persistence of the multidecade-long drought over southwest Western Australia? Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, (2011).

Lim, E. P. et al. Australian hot and dry extremes induced by weakenings of the stratospheric polar vortex. Nat. Geosci. 12, 896–901 (2019).

Taschetto, A. S. et al. Australian monsoon variability driven by a Gill–Matsuno-type response to Central West Pacific warming. https://doi.org/10.1175/2010JCLI3474.1 (2010).

Freund, M. B., Marshall, A. G., Wheeler, M. C. & Brown, J. N. Central Pacific El Niño as a precursor to summer drought-breaking rainfall over Southeastern Australia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091131 (2021).

Heidemann, H. et al. Variability and long-term change in Australian monsoon rainfall: a review. WIREs Clim. Change 14, e823 (2023).

Lim, E. P. et al. Why Australia was not wet during spring 2020 despite La Niña. Sci. Rep. 2021 11:1 11, 1–15 (2021).

Zhang, W. et al. Tropical Indo-Pacific compounding thermal conditions drive the 2019 Australian extreme drought. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL090323 (2021).

Holgate, C., Evans, J. P., Taschetto, A. S., Gupta, A. S. & Santoso, A. The impact of interacting climate modes on East Australian precipitation moisture sources. J. Clim. 35, 3147–3159 (2022).

Liguori, G., McGregor, S., Singh, M., Arblaster, J. & Di Lorenzo, E. Revisiting ENSO and IOD Contributions to Australian Precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL094295 (2022).

Wang, H., Schubert, S., Koster, R., Ham, Y.-G. & Suarez, M. On the role of SST forcing in the 2011 and 2012 extreme U.S. heat and drought: a study in contrasts. https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-13-069.1 (2014).

Ayugi, B. et al. Review of meteorological drought in Africa: historical trends, impacts, mitigation measures, and prospects. Pure Appl. Geophys. 179, 1365–1386 (2022).

Zeng, N. et al. Causes and impacts of the 2005 Amazon drought. Environ. Res. Lett. 3, 014002 (2008).

Marengo, J. A., Tomasella, J., Alves, L. M., Soares, W. R. & Rodriguez, D. A. The drought of 2010 in the context of historical droughts in the Amazon region. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, (2011).

Gomes, M. S., Cavalcanti, I. F., de, A. & Müller, G. V. 2019/2020 drought impacts on South America and atmospheric and oceanic influences. Weather Clim. Extremes 34, 100404 (2021).

Gallant, A. J. E. & Karoly, D. J. Atypical influence of the 2007 La Niña on rainfall and temperature in southeastern Australia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, (2009).

Holgate, C. M., Evans, J. P., Dijk, A. I. J. M., van, Pitman, A. J. & Virgilio, G. D. Australian precipitation recycling and evaporative source regions. J. Clim. 33, 8721–8735 (2020).

Cai, W., van Rensch, P., Cowan, T. & Hendon, H. H. Teleconnection pathways of ENSO and the IOD and the mechanisms for impacts on Australian rainfall. J. Clim. 24, 3910–3923 (2011).

Gillett, Z. E., Taschetto, A. S., Holgate, C. M. & Santoso, A. Linking ENSO to synoptic weather systems in Eastern Australia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL104814 (2023).

Hauser, S. et al. A weather system perspective on winter–spring rainfall variability in southeastern Australia during El Niño. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. n/a, (2020).

Ummenhofer, C. C. et al. Indian and Pacific Ocean influences on Southeast Australian drought and soil moisture. J. Clim. 24, 1313–1336 (2010).

King, A. D., Pitman, A. J., Henley, B. J., Ukkola, A. M. & Brown, J. R. The role of climate variability in Australian Drought. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 177–179 (2020).

Parker, T. & Gallant, A. J. E. The role of heavy rainfall in drought in Australia. Weather Clim. Extrem. 38, 100528 (2022).

Holgate, C. M., Van Dijk, A. I. J. M., Evans, J. P. & Pitman, A. J. Local and remote drivers of Southeast Australian Drought. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL090238 (2020).

Taschetto, A. S. et al. Changes in moisture sources contributed to the onset and development of the 2017-2019 southeast Australian drought. Weather Clim. Extrem. 44, 100672 (2024).

Schumacher, D. L., Keune, J., Dirmeyer, P. & Miralles, D. G. Drought self-propagation in drylands due to land–atmosphere feedbacks. Nat. Geosci. 15, 262–268 (2022).

Li, H., Keune, J., Gou, Q., Holgate, C. M. & Miralles, D. Heat and moisture anomalies during crop failure events in the Southeastern Australian Wheat Belt. Earth’s. Future 12, e2023EF003901 (2024).

Kala, J., Lyons, T. J. & Nair, U. S. Numerical simulations of the impacts of land-cover change on cold fronts in South-West Western Australia. Bound.-Layer. Meteorol. 138, 121–138 (2011).

Pitman, A. J., Narisma, G. T., Pielke, R. A. & Holbrook, N. J. Impact of land cover change on the climate of Southwest Western Australia. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 109, (2004).

Sharmila, S. & Hendon, H. H. Mechanisms of multiyear variations of Northern Australia wet-season rainfall. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–11 (2020).

Holgate, C. M., Pepler, A. S., Rudeva, I. & Abram, N. J. Anthropogenic warming reduces the likelihood of drought-breaking extreme rainfall events in southeast Australia. Weather Clim. Extrem. 42, 100607 (2023).

Pepler, A. & Dowdy, A. Fewer deep cyclones projected for the midlatitudes in a warming climate, but with more intense rainfall. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 054044 (2021).

Jin, C., Reeder, M. J., Gallant, A. J. E., Parker, T. & Sprenger, M. Changes in weather systems during anomalously wet and dry years in Southeastern Australia. J. Clim. 37, 1131–1153 (2024).

Jin, C., Reeder, M. J., Gallant, A. J. E., Parker, T. & Sprenger, M. A synoptic-dynamic view of the millennium drought (2001–2009) in Southeastern Australia. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 129, e2024JD041657 (2024).

Barnes, M. A., King, M., Reeder, M. & Jakob, C. The dynamics of slow-moving coherent cyclonic potential vorticity anomalies and their links to heavy rainfall over the eastern seaboard of Australia. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 149, 2233–2251 (2023).

Pepler, A. Record lack of cyclones in Southern Australia during 2019. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088488 (2020).

Tozer, C. R., Risbey, J. S., O’Kane, T. J., Monselesan, D. P. & Pook, M. J. The relationship between wave trains in the Southern Hemisphere Storm track and rainfall extremes over Tasmania. Monthly Weather Rev. 146, 4201–4230 (2018).

Rodrigues, R. R., Taschetto, A. S., Sen Gupta, A. & Foltz, G. R. Common cause for severe droughts in South America and marine heatwaves in the South Atlantic. Nat. Geosci. 12, 620–626 (2019).

Hope, P. K., Drosdowsky, W. & Nicholls, N. Shifts in the synoptic systems influencing Southwest Western Australia. Clim. Dyn. 26, 751–764 (2006).

Cowan, T., Wheeler, M. C. & Marshall, A. G. The combined influence of the Madden–Julian oscillation and El Niño–Southern oscillation on Australian rainfall. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-22-0357.1 (2022).

Cowan, T. et al. Forecasting the extreme rainfall, low temperatures, and strong winds associated with the northern Queensland floods of February 2019. Weather Clim. Extrem. 26, 100232 (2019).

Ukkola, A. M. et al. Evaluating CMIP5 model agreement for multiple drought metrics. J. Hydrometeor. 19, 969–988 (2018).

Stephens, G. L. et al. Dreary state of precipitation in global models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 115, (2010).

Martinez-Villalobos, C., Neelin, J. D. & Pendergrass, A. G. Metrics for evaluating CMIP6 representation of daily precipitation probability distributions. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-21-0617.1 (2022).

Rocheta, E., Sugiyanto, M., Johnson, F., Evans, J. & Sharma, A. How well do general circulation models represent low-frequency rainfall variability? Water Resour. Res. 50, 2108–2123 (2014).

Moon, H., Gudmundsson, L. & Seneviratne, S. I. Drought persistence errors in global climate models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 3483–3496 (2018).

Grose, M. R. et al. Insights from CMIP6 for Australia’s future climate. Earth’s. Future 8, e2019EF001469 (2020).

Rauniyar, S. P. & Power, S. B. The impact of anthropogenic forcing and natural processes on past, present, and future rainfall over Victoria, Australia. J. Clim. 33, 8087–8106 (2020).

Chung, C. et al. Evaluation of seasonal teleconnections to remote drivers of Australian rainfall in CMIP5 and CMIP6 models. JSHESS 73, 219–261 (2023).

Rackow, T. et al. Towards multi-resolution global climate modeling with ECHAM6-FESOM. Part II: climate variability. Clim. Dyn. 50, 2369–2394 (2018).

Iles, C. E. et al. The benefits of increasing resolution in global and regional climate simulations for European climate extremes. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 5583–5607 (2020).

Bi, D. et al. Improved simulation of ENSO variability through feedback from the Equatorial Atlantic in a pacemaker experiment. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL096887 (2022).

Wills, R. C. J., Dong, Y., Proistosecu, C., Armour, K. C. & Battisti, D. S. Systematic climate model biases in the large-scale patterns of recent sea-surface temperature and sea-level pressure change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100011 (2022).

Lieber, R., Brown, J., King, A. & Freund, M. Historical and future asymmetry of ENSO teleconnections with extremes. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-23-0619.1 (2024).

Tozer, C. R. et al. Assessing the representation of Australian regional climate extremes and their associated atmospheric circulation in climate models. J. Clim. 33, 1227–1245 (2020).

Chapman, S. et al. Evaluation of dynamically downscaled CMIP6-CCAM models over Australia. Earth’s. Future 11, e2023EF003548 (2023).

Fita, L., Evans, J. P., Argüeso, D., King, A. & Liu, Y. Evaluation of the regional climate response in Australia to large-scale climate modes in the historical NARCliM simulations. Clim. Dyn. 49, 2815–2829 (2017).

Di Virgilio, G. et al. Realised added value in dynamical downscaling of Australian climate change. Clim. Dyn. 54, 4675–4692 (2020).

Rampal, N. et al. Enhancing regional climate downscaling through advances in machine learning. https://doi.org/10.1175/AIES-D-23-0066.1 (2024).

Isphording, R. N. et al. A standardized benchmarking framework to assess downscaled precipitation simulations. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-23-0317.1 (2024).

Ukkola, A. M. et al. Land surface models systematically overestimate the intensity, duration and magnitude of seasonal-scale evaporative droughts. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 104012 (2016).

Simpson, I. R. et al. Observed humidity trends in dry regions contradict climate models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2302480120 (2024).

Firth, R., Kala, J., Hudson, D., Hawke, K. & Marshall, A. ACCESS-S2 seasonal forecasts of rainfall and the SAM–rainfall relationship during the grain growing season in south-west Western Australia. JSHESS 74, (2024).

Lim, E.-P., Hendon, H. H., Hudson, D., Wang, G. & Alves, O. Dynamical forecast of inter–El Niño variations of tropical SST and Australian Spring rainfall. https://doi.org/10.1175/2009MWR2904.1 (2009).

Chiew, F. H. S., Piechota, T. C., Dracup, J. A. & McMahon, T. A. El Nino/Southern oscillation and Australian rainfall, streamflow and drought: links and potential for forecasting. J. Hydrol. 204, 138–149 (1998).

Tozer, C. R. et al. A tale of two novembers: confounding influences on La Niña’s relationship with rainfall in Australia. https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-23-0112.1 (2024).

Cowan, T., Hinds, E., Marshall, A. G., Wheeler, M. C. & Burgh-Day, C. de. Observing and forecasting the retreat of northern Australia’s rainy season. JSHESS 74, NULL–NULL (2024).

Erfanian, A., Wang, G. & Fomenko, L. Unprecedented drought over tropical South America in 2016: significantly under-predicted by tropical SST. Sci. Rep. 7, 5811 (2017).

Hobeichi, S. et al. How well do climate modes explain precipitation variability? npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 1–9 (2024).

Wedd, R. et al. ACCESS-S2: the upgraded Bureau of Meteorology multi-week to seasonal prediction system. JSHESS 72, 218–242 (2022).

King, A. D. et al. Sub-seasonal to seasonal prediction of rainfall extremes in Australia. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 2228–2249 (2020).

Dikshit, A., Pradhan, B., Assiri, M. E., Almazroui, M. & Park, H.-J. Solving transparency in drought forecasting using attention models. Sci. Total Environ. 837, 155856 (2022).

Hobeichi, S., Abramowitz, G., Evans, J. P. & Ukkola, A. Toward a robust, impact-based, predictive drought metric. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2021WR031829 (2022).

Hobeichi, S. et al. Using machine learning to cut the cost of dynamical downscaling. Earth’s. Future 11, e2022EF003291 (2023).

Kirono, D. G. C., Round, V., Heady, C., Chiew, F. H. S. & Osbrough, S. Drought projections for Australia: Updated results and analysis of model simulations. Weather Clim. Extrem. 30, 100280 (2020).

Eccles, R. et al. Meteorological drought projections for Australia from downscaled high-resolution CMIP6 climate simulations. EGUsphere 1–31 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2024-2341 (2024).

Rauniyar, S. P. & Power, S. B. Estimating future rainfall distributions in a changing climate for water resource planning: Victoria, Australia. Clim. Dyn. 60, 527–547 (2023).

McKay, R. C. et al. Can Southern Australian rainfall decline be explained? A review of possible drivers. WIREs Clim. Change e820 https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.820 (2023).

Henley, B. J. et al. Amplification of risks to water supply at 1.5 °C and 2 °C in drying climates: a case study for Melbourne, Australia. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 084028 (2019).

Spinoni, J. et al. Future global meteorological drought hot spots: a study based on CORDEX data. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-19-0084.1 (2020).

Ukkola, A. M. et al. Future changes in seasonal drought in Australia. (2024).

Abram, N. J. et al. Palaeoclimate perspectives on the Indian Ocean Dipole. Quat. Sci. Rev. 237, 106302 (2020).

Wang, G. et al. The Indian Ocean dipole in a warming world. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 588–604 (2024).

Abram, N. J. et al. Coupling of Indo-Pacific climate variability over the last millennium. Nature 579, 385–392 (2020).

Cobb, K. M. et al. Highly variable El Niño–Southern oscillation throughout the holocene. Science 339, 67–70 (2013).

Grothe, P. R. et al. Enhanced El Niño–Southern oscillation variability in recent decades. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL083906 (2020).

Cai, W. et al. Anthropogenic impacts on twentieth-century ENSO variability changes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 407–418 (2023).

Cai, W. et al. Changing El Niño–Southern oscillation in a warming climate. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 628–644 (2021).

Power, S., Delage, F., Chung, C., Kociuba, G. & Keay, K. Robust twenty-first-century projections of El Niño and related precipitation variability. Nature 502, 541–545 (2013).

McGregor, S., Cassou, C., Kosaka, Y. & Phillips, A. S. Projected ENSO teleconnection changes in CMIP6. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097511 (2022).

Power, S. B. & Delage, F. P. D. El Niño–Southern Oscillation and Associated Climatic Conditions around the World during the Latter Half of the Twenty-First Century. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-18-0138.1 (2018).

Maher, N. et al. The future of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation: using large ensembles to illuminate time-varying responses and inter-model differences. Earth Syst. Dyn. 14, 413–431 (2023).

Banerjee, A., Fyfe, J. C., Polvani, L. M., Waugh, D. & Chang, K.-L. A pause in Southern Hemisphere circulation trends due to the Montreal Protocol. Nature 579, 544–548 (2020).

Goyal, R., Sen Gupta, A., Jucker, M. & England, M. H. Historical and Projected Changes in the Southern Hemisphere Surface Westerlies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL090849 (2021).

Hope, P. K. Projected future changes in synoptic systems influencing southwest Western Australia. Clim. Dyn. 26, 765–780 (2006).

Joos, H., Sprenger, M., Binder, H., Beyerle, U. & Wernli, H. Warm conveyor belts in present-day and future climate simulations—part 1: climatology and impacts. Weather Clim. Dyn. 4, 133–155 (2023).

Cai, W. et al. Increased frequency of extreme La Niña events under greenhouse warming. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 132–137 (2015).

Geng, T. et al. Increased occurrences of consecutive La Niña events under global warming. Nature 619, 774–781 (2023).

Falster, G., Konecky, B., Coats, S. & Stevenson, S. Forced changes in the Pacific Walker circulation over the past millennium. Nature 622, 93–100 (2023).

Dai, A., Zhao, T. & Chen, J. Climate change and drought: a precipitation and evaporation perspective. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 4, 301–312 (2018).

Dettinger, M. D. Atmospheric rivers as drought busters on the U.S. West Coast. J. Hydrometeorol. 14, 1721–1732 (2013).

Zhang, W. et al. Fewer troughs, not more ridges, have led to a drying trend in the Western United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097089 (2022).

Conradie, W. S., Wolski, P. & Hewitson, B. C. Spatial heterogeneity of 2015–2017 drought intensity in South Africa’s winter rainfall zone. Adv. Stat. Climatol., Meteorol. Oceanogr. 8, 63–81 (2022).

O’Connor, J. A., Henley, B. J., Brookhouse, M. T. & Allen, K. J. Ring-width and blue-light chronologies of Podocarpus lawrencei from southeastern mainland Australia reveal a regional climate signal. Climate 18, 2567–2581 (2022).

Udy, D. G., Vance, T. R., Kiem, A. S. & Holbrook, N. J. A synoptic bridge linking sea salt aerosol concentrations in East Antarctic snowfall to Australian rainfall. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 1–11 (2022).

Evans, A., Jones, D., Smalley, R. & Lellyet, S. An Enhanced Gridded Rainfall Analysis Scheme for Australia. http://www.bom.gov.au/research/publications/researchreports/BRR-041.pdf (2020).

Huang, A. T., Gillett, Z. E. & Taschetto, A. S. Australian rainfall increases during multi-year La Niña. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL106939 (2024).

Saji, N. H., Goswami, B. N., Vinayachandran, P. N. & Yamagata, T. A dipole mode in the tropical Indian Ocean. Nature401, 360–363 (1999).

Acknowledgements

C.M.H., N.M., G.M.F., Z.E.G., S.H., A.M.U., J.P.E., M.O.G., J.C.P., A.J.P., N.J.A. acknowledge funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes (CE170100023). T.J.P. and D.H. are supported by funding from the Australian Climate Service. H.N. is funded by Meat and Livestock Australia, the Queensland Government through the Drought and Climate Adaptation Program, and the University of Southern Queensland through the Northern Australia Climate Program. S.R. is funded in part by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program (NESP). A.D.K. and P.G. are also supported by NESP. A.M.U. is supported by an ARC Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE200100086). This research was undertaken with the assistance of resources and services from the National Computational Infrastructure (NCI), which is supported by the Australian Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors C.M.H., G.M.F., Z.E.G., P.G., M.O.G., S.H., D.H., X.J., C.J., X.L., M.M., J.C.P., T.J.P., E.V., N.J.A., J.P.E., A.J.E.G., B.J.H., J.K., A.D.K., N.M., H.N., A.J.P., S.B.P., S.P.R., A.S.T., A.M.U. contributed to the conceptualisation and writing of the article. CMH handled the structuring of the article narrative, coordinated input from all coauthors and handled the article revisions. Authors C.M.H., G.M.F., Z.E.G., P.G., M.O.G., S.H., D.H., X.J., C.J., X.L., M.M., J.C.P., T.J.P., E.V., N.J.A., J.P.E., A.J.E.G., B.J.H., J.K., A.D.K., N.M., H.N., A.J.P., S.B.P., S.P.R., A.S.T., A.M.U. contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Holgate, C.M., Falster, G.M., Gillett, Z.E. et al. Physical mechanisms of meteorological drought development, intensification and termination: an Australian review. Commun Earth Environ 6, 220 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02179-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02179-3

This article is cited by

-

A Bayesian Framework for Spatiotemporal Analysis of Meteorological Drought Dynamics

Pure and Applied Geophysics (2025)

-

A basin scale future projection of drought characteristics using bias-corrected CMIP6 (MIROC6) model ensemble

Journal of Earth System Science (2025)

-

Climate impacts of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation on Australia

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2025)