Abstract

Extreme Indian Ocean dipole events (EXIODs) exert pronounced climate impacts both regionally and globally, which are closely associated with their sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTAs). Here we find an evident asymmetry in SSTA patterns between the positive (EXpIOD) and negative (EXnIOD) phases of the EXIOD. Specifically, the warm SSTA center of the EXnIOD eastern pole is confined south of Java, whereas the cold pole during EXpIODs is primarily located off Sumatra. Diagnoses with model experiments further reveal that the pattern asymmetry is attributed to the non-uniformly distributed nonlinear vertical heat advection and latent heat flux anomalies along the Sumatra–Java coasts. Due to pattern asymmetry, more frequent and intense marine heatwaves and extreme sea level rise events induced by EXnIODs occur along the Java coast. However, current climate models systematically underestimate the degree of pattern asymmetry and its influences on local marine disasters, thereby challenging accurate predictions of coastal extremes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Indian Ocean dipole (IOD) is the dominant interannual climate mode of the tropical Indian Ocean (TIO)1,2, which can operate independently of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)3. The IOD typically initiates in boreal summer or even late spring and matures in boreal autumn (September–November; SON). During its positive phase (pIOD), cold sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTAs) develop off the coasts of Sumatra and Java, accompanied by warm SSTAs in the western basin1,2 (Fig. 1c). In response to the SSTA forcing, precipitation increases over the western TIO, while dry anomalies appear over the eastern basin (Supplementary Fig. 1a), producing easterly anomalies along the equator. The easterly wind anomalies in turn cause changes in ocean currents and the tilt of thermocline that further reinforce the original SSTAs, forming a positive feedback loop referred to as the Bjerknes feedback1,2,4,5. Opposite conditions generally hold for negative IOD (nIOD) events.

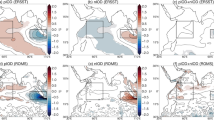

a, d SON SSTA composites for a EXpIOD and d EXnIOD events, respectively. Significant values at the 90% confidence level are stippled by black dots. Green stars mark the centre of SSTAs with maximum amplitude. b, e Spatially b symmetric and e asymmetric components of extreme IOD composites, respectively (see the ‘Identifying extreme IOD events and extracting the asymmetric component in composites’ section in 'Methods'). c EOF1-related SSTAs (°C, shading) over the TIO, obtained by regressing SON SSTAs in TIO onto the PC1 of the EOF analysis for the 85°–120°E, 0°–10°S region (see the ‘EOF analysis and metrics in CMIP models’ section in 'Methods'). Its corresponding fractional explained variance (EV) is also presented. f Same as (c), but for EOF2-related SSTAs. The great resemblance between (e) and (f) endows the mathematically derived EOF2 with a physical meaning. g Scatterplots of the standardised PC1 and PC2 of SST EOF in phase space. h Same as (g), but for the PCs of rainfall EOF. The nonlinearity of PC2 as a function of PC1 is outlined by the black fitted line with the quadratic parameter α shown.

The IOD alters the climate conditions of the TIO and surrounding continental areas as well as exerts far-reaching influences on remote regions through atmospheric teleconnections6,7. Moreover, the repercussions of IOD events could be multifaceted, widespread and long-lasting through triggering breakouts of infectious and respiratory diseases8,9, affecting regional and global carbon budget10,11, and interacting with other climate modes, such as ENSO, the Indian Ocean basin (IOB) mode, and Atlantic Niño12,13,14. In particular, extreme IOD events stand out from moderate ones as they impinge greatly on the hydrological and ecological cycles of the TIO-rim countries. For example, the 1997 and 2019 extreme pIOD (EXpIOD) events induced severe droughts and bushfires in Indonesia15 and Australia16, and meanwhile brought devastating floods to parts of the Indian subcontinent17 and eastern Africa5. By contrast, the extreme nIOD (EXnIOD) event in 2016 suppressed the East African rainfall activity during the local rainy season (October–December) to below 1 mm day−1, resulting in over 15 million people in Somalia, Ethiopia and Kenya experiencing food deficit and unsafe drinking water18. In addition, a recent study found that the EXnIOD events could induce Compound sea surface Heat-Height Extremes (CHHEXs) around low-lying island nations like Indonesia, causing more devastating impacts than heat or height extremes happen individually19.

Both EXpIOD and EXnIOD have profound climatic impacts, but their associated climate anomalies are not exactly mirror images20,21. In particular, previous studies have shown that the SSTA amplitude of the EXpIOD events is higher than that of the EXnIOD22,23,24,25 (Supplementary Fig. 2a), as reflected by the positive skewness of the dipole mode index1 (DMI; see 'Methods'). As a fundamental intrinsic feature of the IOD, the amplitude asymmetry has been extensively investigated and attributed to the nonlinearity in the thermocline feedback23,24, the shortwave radiation–SST feedback22, vertical mixing25 and nonlinear advection processes22.

Despite the overall higher amplitude of the EXpIOD compared to the EXnIOD, we found that in the Java coastal region, the observed warm SSTAs during the EXnIOD are stronger in magnitude than cold SSTAs of the EXpIOD (Fig. 1a, d, e). Along the Sumatra coasts, on the contrary, the EXpIOD SSTAs are indeed more prominent. These results suggest a pattern asymmetry of extreme IOD events—the cold pole of the EXpIOD is primarily located off the Sumatra coast, whereas the warm centre of the EXnIOD is more concentrated along the southern coast of Java, which has not been clearly identified and systematically studied. Given the prominent climatic impacts of the extreme IOD events that are closely associated with the distinct SSTA patterns, such pattern asymmetry between EXpIOD and EXnIOD holds significant implications for both Indonesia and other remote regions. Here, by combining observational analysis and model simulations, we investigate the physical causes for the pattern asymmetry and explore its coastal impacts by examining the characteristics of CHHEXs—the compound marine disaster frequently occurred in the coastal regions of Indonesia.

Results

Identifying pattern asymmetry between EXpIOD and EXnIOD events

The IOD manifests as a zonal see-saw pattern of SSTAs between the western and the eastern TIO. Meanwhile, it has been well recognised that the variability of the IOD’s eastern pole is greater than that of its western counterpart1,22. Therefore, the amplitude asymmetry between extreme IOD events primarily resides in the eastern pole and is reflected by the overall more pronounced cold SSTAs along the entire Sumatra–Java coasts during EXpIOD compared to the warm SSTAs during EXnIOD. Furthermore, the pattern asymmetry also mainly appears in the eastern pole with a meridional dipole structure (Fig. 1e; see 'Methods'), in a manner that the EXnIOD produces stronger warming around Java (compared to EXpIOD-generated cooling), whereas the EXpIOD generates stronger cooling around Sumatra coasts (compared to EXnIOD-generated warming). These results suggest that the eastern TIO is the key region for characterising and understanding the IOD asymmetry.

We further perform an empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis on the SON SSTAs, when the IOD usually matures, over the eastern TIO (85°–120°E, 0°–10°S; see 'Methods') and demonstrate the spatiotemporal features of interannual SST variabilities in this key region. The first EOF mode (EOF1) mainly describes the general IOD pattern (Fig. 1c), with its corresponding principal component (PC1) highly correlated with the DMI1 (R = 0.96). Both the PC1 and the DMI exhibit a positive skewness (0.87 vs 1.10), suggesting that the amplitude asymmetry of the IOD is largely embodied in the EOF1 mode. Indeed, the reconstructed EXpIOD by combining the EOF1 and PC1 (see “Methods”) clearly exhibits a much stronger eastern pole compared to the reconstructed EXnIOD (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Note that by reconstruction, the EOF1 can only depict a fixed IOD pattern with oscillating phases and intensities during the analysis period. As a result, this mode alone cannot capture the pattern asymmetry found in observations (compare Fig. 1e with Supplementary Fig. 3c). Interestingly, the second EOF mode (EOF2) exhibits a meridional dipole in the eastern TIO with opposite SSTAs off the Sumatra and Java coasts, closely resembling the asymmetric pattern between the two phases of extreme IOD events (Fig. 1e, f). In addition, its corresponding PC (PC2) is large and positive during both EXpIOD and EXnIOD events (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 2b). Consequently, the scatterplot between PC1 and PC2 exhibits a V-shape structure, all EXpIOD events clustered in the first quadrant and all EXnIOD events in the second quadrant (Fig. 1g). These results suggest that the EOF2 mode acts in a similar manner to both the EXpIOD and EXnIOD events, thereby playing a critical role in explaining the pattern asymmetry, and the nonlinear dependence of PC2 on PC1 enables these two EOF modes to separate as linearly orthogonal modes. Combining the first two EOF modes can well explain the IOD SST variability (explained variances = 88%) in the eastern pole region, and meanwhile fully capture its asymmetries in both amplitude and spatial pattern. Likewise, a similar meridional dipole structure can be detected in the rainfall EOF decomposition (Supplementary Fig. 1b), and their PCs also exhibit quadratic behaviour (Fig. 1h), validating the pattern asymmetry as an inherent feature of air–sea coupled extreme IOD events.

Pattern asymmetry’s evolutions and dominant processes

To explore the physical mechanism of the pattern asymmetry, we first characterise the temporal evolutions of extreme IOD events (Supplementary Fig. 4). SSTAs at the eastern pole, for both EXpIOD and EXnIOD events, emerge in April–May (AM) and gradually intensify in June–July (JJ). During this initiation stage, the two phases of the extreme IOD are largely symmetric in their spatial patterns, with the strongest SSTAs both located along the Java coasts where the climatological upwelling driven by the southeast monsoon winds appears first26,27,28, providing a favourable condition for enhancing SSTAs through the thermocline feedback27,28. During the fast-developing stage in August–September (AS), the cold SSTAs during the EXpIOD propagate northwestward along the Sumatra coasts, while the warm SSTAs of the EXnIOD are primarily enhanced locally with a westward extension to some extent. In October–November (ON) when extreme IOD events reach their peaks, the cold pole of the EXpIOD further develops and extends to the west of the Sumatra coasts, whereas the warm pole of the EXnIOD is mainly located to the south, leading to the mature phase of pattern asymmetry (Supplementary Fig. 4g, h). The discrepancies in the temporal evolutions between EXpIOD and EXnIOD are further underpinned by the distinct patterns of the mixed-layer temperature tendency (\({T}_{t}^{\prime }\); see 'Methods') in boreal summer (Fig. 2a, b). The asymmetric component of \({T}_{t}^{\prime }\) also exhibits a meridional dipole with opposite signs along the Sumatra and Java coasts (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 5), which reaches the maximum in July and August (JA) (Supplementary Fig. 5), highlighting a key season for the formation of the pattern asymmetry.

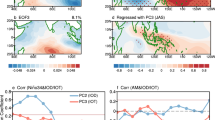

a Averaged MLT tendency (\({T}_{t}^{\prime }\)) in JA (°C month−1) for EXpIOD events. b Same as (a), but for EXnIOD events. c Spatially asymmetric component between (a) and (b), which is defined as the difference between the averaged EXpIOD and the reversed EXnIOD [EXpIOD − ( − EXnIOD)] (see the ‘Mixed-layer heat budget analysis’ section in 'Methods'). The meridional dipole represents the residuals of EXpIOD and EXnIOD events after cancelling each other out. The cooling tendency off Sumatra and the warming tendency off Java are highlighted by the northern black box (a parallelogram-shaped region extending 5° offshore from the coast of Sumatra) and the southern black box (105°–115°E, 12°–8°S), respectively. d Asymmetric components of heat budget terms averaged over the northern (southern) box in c are represented as the blue bars (red bars), and the green bars are calculated as their difference (blue minus red). Therefore, the green bar measures the contrast in the meridional dipole. Nonlinear advection (NA) denotes the summation of three-dimensional nonlinear oceanic advections (\(-{u}^{\prime }{T}_{x}^{\prime }\), \(-{v}^{\prime }{T}_{y}^{\prime }\) and \(-{w}^{\prime} {T}_{z}^{\prime }\)) by anomalous currents advecting SSTA, and linearised advection (LA) denotes the summation of three-dimensional linearised advection terms due to anomalous currents advecting mean SST and mean currents advecting SSTA (\(-{u}^{\prime} {\overline{T}}_{x}\), \(-\overline{u}{T}_{x}^{\prime }\), \(-{v}^{\prime }{\overline{T}}_{y}\), \(-\overline{v}{T}_{y}^{\prime }\), \(-{w}^{\prime} {\overline{T}}_{z}\) and \(-\overline{w}{T}_{z}^{\prime }\)). The LA terms generally show mirror images between phases with opposite signs, so that their magnitudes decrease remarkably after extracting the asymmetric components. On the contrary, the NA terms have the same sign for both phases, making their roles stand out. e Decomposition of NA into horizontal and vertical advection terms. f Asymmetric components of the LHF (\({Q}_{{lh}}^{\prime }\)).

To understand the causes of the asymmetry of \({T}_{t}^{\prime }\), we diagnose the asymmetric components of the JA heat budget terms along Sumatra and Java, respectively, and present the contrast between them (see 'Methods'). The results show that the linearised horizontal and vertical advection terms (i.e., mean ocean currents advecting SSTA and anomalous currents advecting mean SST) have little contribution to the meridional pattern asymmetry between Sumatra and Java (the green LA bar in Fig. 2d), as they generally exhibit similar spatial patterns with opposite signs between EXpIOD and EXnIOD events, thereby leading to weak signals in their asymmetric components (Supplementary Fig. 6). It is worth noting, though, that the linear terms—particularly thermocline feedback (\(-\overline{w}{T}_{z}^{\prime }\)) and Ekman feedback (\(-{w}^{\prime }{\overline{T}}_{z}\))—play an important role in the symmetric component of temperature tendency anomalies (Supplementary Fig. 7; representing the common evolution between opposite IOD phases and homogeneous variations along the Sumatra–Java coasts). This is consistent with previous studies4,22, which demonstrated that these linear terms enhance the IOD growth for both phases but with the sign of their promotive thermal contribution depending on the phases.

In contrast, the nonlinear advection terms that result from anomalous ocean currents advecting SSTA have the same sign for both phases of extreme IOD events, substantially contributing to the pattern asymmetry (Fig. 2d, e), and changes in the surface heat fluxes (\({Q}_{{net}}^{\prime }\)) play a synergetic role as well (Fig. 2d). Specifically, the nonlinear advection terms notably promote the development of the cold SSTAs off the Sumatra coast, while their effect is much weaker off Java, producing an evident contrast between the Sumatra and Java coasts (the green NA bar in Fig. 2d). Further decomposition shows that the asymmetric components of the nonlinear horizontal temperature advections (\(-{{{\bf{u}}}}_{h}^{\prime } \cdot {\nabla }_{h}{T}^{\prime }\), comprising \(-{u}^{\prime }{T}_{x}^{\prime }\) and \(-{v}^{\prime }{T}_{y}^{\prime }\)) contribute less to the meridional dipole (Fig. 2e). Although \(-{u}^{\prime }{T}_{x}^{\prime }\) is believed vital for the amplitude asymmetry22, it acts to cool the whole Sumatra and Java offshore regions (Fig. 3b) and its strength is counterbalanced by the warming effect from \(-{v}^{\prime }{T}_{y}^{\prime }\) (Fig. 3c) so that the overall horizontal advection takes a back seat. By contrast, the difference in the nonlinear vertical advection term (\(-{w}^{\prime }{T}_{z}^{\prime }\)) between Sumatra and Java accounts for 85% of the total nonlinear advection differences, being pivotal to the formation of the pattern asymmetry (Figs. 2e and 3a).

a–c Spatial distributions of the asymmetry components in nonlinear a zonal, b meridional and c vertical advection (°C month−1) in JA. d Composites of vertical velocity anomalies (\({w}^{\prime }\); m s−1, shading) in JA for EXpIOD years. g Same as (d), but for EXnIOD years. e Composites of vertical gradient of MLT (\({T}_{z}^{\prime }\); °C m−1, shading) in JA for EXpIOD years. h Same as (e), but for EXnIOD years. f Composites of JA rainfall anomalies (mm day−1, shading) and winds at 10 m (m s−1, vectors) for EXpIOD years. i Same as (f), but for EXnIOD years. Significant values at the 90% confidence level are stippled by white dots or shown as black arrows.

Causes for the spatially asymmetric vertical advection

The nonlinear vertical advection term is the product of vertical velocity anomaly (\({w}^{\prime }\)) and vertical gradient of the MLT anomaly (\({T}_{z}^{\prime }\)), in which \({w}^{\prime }\) is mainly confined off Sumatra (Fig. 3d, g) while \({T}_{z}^{\prime }\) is relatively uniformly distributed along the Sumatra–Java coasts (Fig. 3e, h). Therefore, the spatially asymmetric component of \(-{w}^{\prime }{T}_{z}^{\prime }\) is primarily determined by the distribution of \({w}^{\prime }\). Over the eastern TIO, the low-level wind anomalies during both EXpIOD and EXnIOD are anchored to the west of Java and parallel to the Sumatra coastline, as a Gill-type Rossby wave response to convective heating29 (Fig. 3f, i). Consequently, the upper ocean upwelling anomalies are not equal for the Sumatra–Java coasts. Those off Sumatra are stronger following the Ekman dynamics, whereas the much weaker wind anomalies near Java are incapable of producing significant \({w}^{\prime }\). In physics, the upward \({w}^{\prime }\) off Sumatra during EXpIOD (Fig. 3d) brings subsurface colder water to the surface, facilitating cooling anomalies migrating equatorward along the coastline, but the downward \({w}^{\prime }\) in the same place during EXnIOD (Fig. 3g) prohibits subsurface warmer water further fuelling the surface and thus leaves an asymmetric effect.

Atmospheric general circulation model (AGCM; see 'Methods') experiments forced with observed EXpIOD and EXnIOD SSTAs also support the above mechanism—the Gill-type Rossby wave response located to the northwest of heating is well reproduced (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b). Even when forced by a symmetric SSTA pattern with any amplitude and pattern asymmetries excluded (see 'Methods'), the AGCM still shows a preference for wind anomalies to the Sumatra coast (Supplementary Fig. 9a, b). This sustains that the geographical superiority establishes a favourable condition for anomalous upwelling only occurring near Sumatra, markedly contributing to the pattern asymmetry.

We also explore the reason for the relatively uniformly distributed \({T}_{z}^{\prime }\) along the Sumatra–Java coasts, which is to a large extent determined by the thermocline anomalies affected by changes in both remote equatorial winds and local alongshore winds19,27. Here we conduct a series of experiments with a linear ocean model to separate the effects of local and remote wind forcing30 (see 'Methods'). The model results exhibit nearly symmetric changes in the sea level—an indicator for thermocline anomalies—between EXpIOD and EXnIOD. When only forced by equatorial winds, the oceanic Kelvin waves propagate through the Sumatra–Java coastlines, altering the sea level in coastal regions (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). Meanwhile, due to the dissipation of the Kelvin waves as they propagate and the reflected Rossby waves near Sumatra31, the sea-level anomalies near Sumatra exhibit a larger spatial scale and stronger signals compared to those of Java. On the other hand, the alongshore winds continuously force coastal Kelvin waves, resulting in the energy concentrated near Java as it accumulates downstream (Supplementary Fig. 10c, d). When remote and local wind forcing are combined, they generate a homogeneous distribution of sea-level signals along the Sumatra and Java coasts (Supplementary Fig. 10e, f), thereby contributing less to the pattern asymmetry.

The amplifying effect of the latent heat flux

The \({Q}_{{net}}^{\prime }\) is another factor facilitating the pattern asymmetry. In JA, the asymmetric component of \({Q}_{{net}}^{\prime }\) tends to cause a greater warming along the Java coasts compared to Sumatra (Fig. 2d). This effect of \({Q}_{{net}}^{\prime }\) is dominated by changes in the latent heat flux (LHF, \({Q}_{{lh}}^{\prime }\); Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 11). Note that during both the EXpIOD and the EXnIOD, \({Q}_{{lh}}^{\prime }\) tends to strengthen the SSTAs along the Sumatra coast following the wind–evaporation–SST mechanism4 but acts a damping effect near Java (Fig. 4a, d). Hence, the warm residual in the asymmetric component of \({Q}_{{lh}}^{\prime }\) south of Java arises from the stronger damping to the EXpIOD cold SSTAs (Fig. 4a) compared to the near-zero damping to the EXnIOD warm SSTAs (Fig. 4d). This asymmetry in damping efficiency forces the already existed EXpIOD SSTA centre to decay and move towards a new place, but favours the centre of EXnIOD staying around Java.

a Anomalous LHF (converted into °C month−1) for EXpIOD events. d Same as (a), but for EXnIOD events. b Anomalous wind speed at 10 m (m s−1) for EXpIOD events. e Same as (b), but for EXnIOD events. c Anomalous near-surface sea–air specific humidity difference (kg kg−1) for EXpIOD events. f Same as (c), but for EXnIOD events. g Decomposition of anomalous LHF off the Java coast (105°–115°E, 11°–7.5°S) for EXpIOD events. h Same as (g), but for EXnIOD events. \(-\rho {L}_{v}{C}_{e} \Delta {\overline{q}}{U}_{10}^{\prime }\) and \(-\rho {L}_{v}{C}_{e}\Delta {q}^{\prime }{\overline{U}}_{10}\) denote the wind-driven and thermodynamic contributions to LHF variations, respectively. Significant values at the 90% confidence level are stippled by black dots.

The \({Q}_{{lh}}^{\prime }\) is associated with changes in surface wind speed \({U}_{10}\) and near-surface specific humidity difference \(\Delta q\). During the EXnIOD, the effects of reduced \({U}_{10}\) and increased \(\Delta q\) cancel each other near Java to a large extent (Fig. 4e, f), leading to a muted damping effect (Fig. 4h). During the EXpIOD, on the other hand, wind anomalies reside away from the south of Java (Fig. 4b), allowing the decreased \(\Delta q\) to cause a weaker ocean heat loss and strongly damps the cold SSTAs (Fig. 4b, c, g). Hence, the much weaker damping effect by \({Q}_{{lh}}^{\prime }\) off Java in EXnIOD compared to EXpIOD is mainly attributed to different wind changes, which are ultimately linked to the differences in rainfall anomalies. The rainfall deficit during the EXpIOD is located further to the north than the rainfall increase during the EXnIOD (Fig. 3f, i). As a result, the associated wind anomalies are also shifted northward away from the Java coast during the EXpIOD, leading to weaker changes in local \({U}_{10}\). In AGCM experiments forced by the observed JA SSTA patterns during EXpIOD and EXnIOD, the meridional asymmetric rainfall anomalies and the magnitude contrast in \({U}_{10}^{\prime }\) near Java are indeed well reproduced (Supplementary Fig. 8c).

As time progresses to SON, nonlinear heat advections continuously enlarge the distance between the SSTA centres of EXpIOD and EXnIOD events. Accordingly, the contrasts in rainfall, Java coastal wind speed and \({Q}_{{lh}}^{\prime }\) patterns are also magnified. These results suggest that the \({Q}_{{lh}}^{\prime }\) effect provides a positive feedback that amplifies the pattern asymmetry induced by nonlinear dynamical processes.

Inhomogeneous vulnerability of coastal Indonesia to CHHEXs here

The Indonesian Archipelago is home to hundreds of millions of people as well as a diverse array of sea creatures and plants, including vibrant coral reefs, mangroves, and seagrass32. Marine disasters such as marine heatwaves (MHWs) and extreme sea-level rise (Height Extremes; HEXs) frequently occur in the eastern TIO19, often causing catastrophic impacts on low-lying Indonesian island nations that are particularly susceptible to these disasters due to the limited living space and the vulnerable ecosystem.

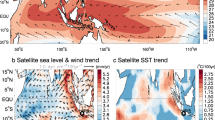

The variability around Indonesian seas is strongly affected by the IOD mode, with the Sumatra and Java coasts identified as the most variable regions (Fig. 5a, d). It has been reported that extreme disasters (MHWs and HEXs) and their compound events (i.e., CHHEXs) are at least in part induced by the EXnIOD19. Indeed, all four EXnIOD events cause prominent SST warming and sea-level rise along the coastal regions near Sumatra and Java (Fig. 5g, h). As it turns from JA to SON, the warming at the eastern pole of the EXnIOD is primarily centred to the south of Java coasts (Fig. 5b, c and also Supplementary Fig. 4h), while the associated anomalies along the Sumatra coasts are relatively weaker due to the pattern asymmetry. Accordingly, the mature phase of sea-level rise also exhibits a meridional contrast (Fig. 5e, f). The severity of both MHWs and HEXs in the Java coastal region is, consequently, 2–3 times as high as those near Sumatra, posing a much greater threat to the former region (Fig. 5g, h, yellow shading). Meanwhile, the frequency of CHHEXs in the Java region is twice that near Sumatra over the past 30 years as well (Supplementary Fig. 12). These results highlight the important impacts of the IOD pattern asymmetry on coastal environments.

a The standard deviation of monthly SSTA on each grid. b, c Same as (a), but for (b) the upper 90th percentile and c the 99th percentile, respectively. The bold temperature in each panel is the value of the sample site off Java, and other sample sites scattered across the Indonesian Archipelago are also shown for comparison. d–f Same as (a–c), but for the monthly SLA on each grid. g Scatterplots of SON-mean coastal SSTA off Java and Sumatra. The red dashed line marks the ratio of 1:1. h Same as (g), but for coastal SLA. The yellow shading represents values along the Java coast that are larger than those along the Sumatra coast. i Scatterplots of the difference in the occurrences of coastal MHWs (Java minus Sumatra) with respect to the nonlinear parameter α (Supplementary Table 1) in each CMIP6 model. The linear fit (black solid line) and its corresponding 95% confidence intervals (grey shading) are displayed together with the correlation coefficient R. An asterisk indicates statistical significance above the 95% confidence level by a two-tailed Student’s t test. The unit of the y-axis has been converted into the occurrence per 100 years. Also shown is the observed value (green star), which is estimated by directly scaling 2 times per 40 years in the recent observing period to 5 times per 100 years. j Same as (I), but for coastal CHHEXs.

Given the close association between the EXnIOD and marine disasters in the eastern TIO, it is imperative to examine whether the current generation of climate models can faithfully capture the pattern asymmetry as well as its impacts on CHHEXs. Hence, we extend our analysis to century-long numerical simulations from climate models that participate in Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6). A majority of CMIP6 models can reproduce the observed EOF2 mode of SON SSTA in the eastern TIO (all of 42 with Rp > 0.50) and simulate an evidently positive quadratic coefficient α (29 in 42 with α > 0.20), which depicts the nonlinearity between the PC1 and PC2 and thus measures the strength of the pattern asymmetry (Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Table 1; see 'Methods'). Correspondingly, these models also simulate more severe CHHEXs along Java coasts than in Sumatra (Supplementary Fig. 14), consistent with observations.

In addition, the 42 CMIP6 models with higher values of α also show a greater contrast in the frequency of MHWs and CHHEXs between the Java and Sumatra coasts (Fig. 5i, j). However, the pattern asymmetry (assessed by α) in most models (70%) is weaker compared with observations, and consequently, the models systematically underestimate the strength of marine disasters along the coastal Java regions. On the other hand, the observed value lies close to the inter-model fitted line, implying that the Java–Sumatra contrast in reality follows the same constraint with the magnitude of pattern asymmetry as in the modelled framework. This suggests that, due to the pattern asymmetry and the resultant centre preference of EXnIOD events, the coastal ecosystems and communities along the Java coast will continue to face severe risks from CHHEXs over the long term. It highlights the ongoing vulnerability of these areas to climate-induced threats.

Discussion

The IOD asymmetry mostly has been previously noted in the context of its overall amplitude by considering the eastern pole as a whole20,22,33. Here, we demonstrate that the asymmetry also manifests in its spatial pattern (stronger SSTAs during EXpIOD than EXnIOD off Sumatra, whereas stronger EXnIOD than EXpIOD off Java), which is described as the EOF2 of the eastern TIO interannual variability during SON. The pattern asymmetry of extreme IOD events is intrinsically linked to the processes that cause the migration of the cooling centre of EXpIOD events from Java to Sumatra with a far westward extension of SSTAs, and meanwhile anchor the warming centre of EXnIOD events off the Java coast. Thus, we could regard the EXpIOD as a propagative mode (Fig. 6a, c) while the EXnIOD as a quasi-standing mode (Fig. 6b, d). In particular, the nonlinear vertical advection, occurring along the Sumatra coast, promotes the northward movement of the cold SSTAs during the EXpIOD, while keeps the warm centre of the EXnIOD staying along the Java coast. In addition, the damping effect of the \({Q}_{{lh}}^{\prime }\) on SSTAs along the Java coast is greater for EXpIOD than EXnIOD (Fig. 6a, b). As a result, the warming centre of EXnIOD mainly forms and strengthens locally off the Java coast (Fig. 6d).

a JJA SSTAs and subsurface temperature anomalies during EXpIOD events, which nearly constitute a mirror image relative to those of b EXnIOD events. The blue three-dimensional coloured arrows represent nonlinear cold advections in cooperation with the anomalous equatorial and coastal vertical motions at the bottom of the mixed layer. Nonlinear vertical advections and asymmetric latent heat flux jointly reshape the existed SST pattern and further lead to the evident pattern asymmetry between c EXpIOD and d EXnIOD in SON.

In the budget diagnosis, the JA season is primarily considered here rather than September–October (SO), as this is the period when the SSTA centres of EXpIOD and EXnIOD begin to exhibit a tendency for separation, laying the groundwork for the contrasting temperature patterns in the following season. Although during SO, the SSTAs of EXpIOD and EXnIOD intensify, respectively, and the meridional contrast becomes more pronounced, the separation of SST patterns has already occurred by this point. Consequently, the linear advection terms no longer exhibit spatially mirror-like symmetry between the opposite phases, reflecting an outcome of the evolutionary differences originating in the JA season.

Previous studies have highlighted the role of nonlinear zonal advection (\(-{u}^{\prime }{T}_{x}^{\prime }\)) in driving the IOD skewness22,34,35, while this study focuses on the alongshore migration characteristics of the IOD SSTA centre so that coastal processes are emphasised. During JA, the nonlinear zonal advection indeed generates a widespread cooling tendency extending from the south of Java to the southwest of Sumatra (Fig. 3b). However, this cooling effect is comparable in magnitude over the northern and southern diagnostic regions (i.e., lacking a meridional contrast). Moreover, for the northern region of Sumatra, the cooling effect of \(-{u}^{\prime }{T}_{x}^{\prime }\) is not concentrated near the coast (Fig. 3b) and thus does not directly facilitate the alongshore movement of the cold SSTA centre. Combined with a substantial offset by the warming effect of \(-{v}^{\prime }{T}_{y}^{\prime }\) (Fig. 3c), the overall nonlinear horizontal advection contributes less to the meridional pattern asymmetry. Nevertheless, it should be also noted that the \(-{u}^{\prime }{T}_{x}^{\prime }\) term aids in extending the eastern pole cooling further westward and offshore with a broader spatial extent during the subsequent development in SO. Therefore, placing the northern diagnostic region more offshore would reveal a more pronounced impact of \(-{u}^{\prime }{T}_{x}^{\prime }\). However, as we focus on nearshore variations, nonlinear vertical advection (\(-{w}^{\prime }{T}_{z}^{\prime }\)) emerges as the key factor. Its cooling effect is prominent only along the Sumatra coast, facilitating the formation of pattern asymmetry (Fig. 3a).

The pattern asymmetry between positive and negative phases is not unique to the IOD. For ENSO, strong El Niño events tend to peak in the eastern Pacific, while strong La Niña events centre in the central Pacific36. Interestingly, the Pacific SSTA during extreme IOD events also reflects this characteristic (Supplementary Fig. 15a, c, e). Naturally, one might wonder about the influence of concurrent ENSO on IOD pattern asymmetry. As a preliminary analysis, we linearly removed the first two EOF modes of Pacific SSTAs (which collectively explain 78% of the variances; 20°S–20°N, 120°E–80°W) before compositing. This process effectively eliminated significant SST signals in the Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 15b, d), while the IOD pattern asymmetry in the Indian Ocean remained evident (Supplementary Fig. 15f), albeit with slightly reduced amplitude. This demonstrates that, despite modulation by ENSO, the spatial asymmetry is a robust and intrinsic feature of extreme IOD events.

Due to the pattern asymmetry, Java is more likely to be imperilled by the threats of CHHEXs compared with other Indonesian coastal regions, as revealed by our analysis. Since Java is known as one of the hotspots with flourishing fishery resources and trade37, more intense CHHEXs could have devastating impacts on its sensitive marine species and coastal ecosystems38,39. Urgent attention must be given to the extreme IOD events and their associated CHHEXs to better support the development of effective adaptation strategies.

From the climate modelling perspective, most CMIP6 models exhibit biases in simulating nonlinear parameter α, resulting in a significant underestimation of the present-day pattern asymmetry and the contrasting frequency of MHWs and CHHEXs between Sumatra and Java. Under global warming, climate models systematically project a reduction in the current positive IOD skewness33,40. However, how the pattern asymmetry between extreme IOD events will change remains unclear. Therefore, identifying the causes of the current model spread in simulating the intensity of pattern asymmetry is crucial, as it is essential for better constraining the changes in pattern asymmetry and resultant marine disasters around Indonesia under a future warmer scenario.

Methods

Observational datasets and CMIP6 models

The optimal interpolation SST analysis version 2 (OISSTv2)41 with a 1° spatial resolution from 1982 to the present is used to conduct EOF and composited analyses. OISSTv2 is derived from satellite and in situ platforms through optimum interpolation techniques, which guarantee a good performance in presenting IOD skewness35. Rainfall data are provided by the monthly analysis of the Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP)42 on a 2.5° spatial resolution from 1979 to the present, which merges various satellite observations and rain gauge data over land. The three-dimensional ocean reanalysis dataset, Estimating the Circulation and Climate of the Ocean Phase II (ECCO2)43, with a 0.25° spatial resolution from 1992 to 2021, is analysed to understand ocean dynamic processes associated with extreme IOD events. ECCO2 maintains the conservations of heat, salt, volume, and momentum, and thus is appropriate for our diagnostic analysis. Heat fluxes, wind speed at 10 m, and dewpoint temperature at 2 m are from the ECMWF ERA544, which spans from 1979 to the present on a 0.25° spatial resolution. The satellite-derived sea-level anomaly (SLA) data from AVISO with 0.25° spatial resolution during 1993–202145, together with OISSTv2, is used to detect the CHHEXs. Although the above datasets begin at different times, they all have included the years of extreme IOD events (see below), and are adequate to this study.

To show the robustness of IOD spatial asymmetry and enlarge the sample size of CHHEXs, we analyse outputs from 42 CMIP6 coupled global climate models46 (Supplementary Table 1) under the historical radiative forcing covering 165 years of 1850–2014. In these models, both SST and SLA (zos) are available. Since the present study mainly focuses on internal variability, monthly anomalies relative to the whole period’s climatology are constructed and quadratically detrended.

Identifying extreme IOD events and extracting the asymmetric component in composites

The DMI is the area-mean SSTA differences between the western (50°–70°E, 10°S–10°N) and eastern (90°–110°E, 10°S–0°) TIO1. It is widely used to describe the see-saw-like SST fluctuation of the IOD. An EXpIOD (EXnIOD) event is identified when the SON DMI exceeds ±1 standard deviation. Therefore, four EXpIOD events occurred in 1994, 1997, 2006, and 2019, while five EXnIOD events occurred in 1996, 1998, 2010, 2016 and 2022. The case of 2022 is not analysed here due to data limitations of ECCO2 and AVISO SLA, which ended in 2021 and August 2022, respectively.

The averaged EXpIOD (EXnIOD) is obtained by compositing the four cases: 1994, 1997, 2006, and 2019 (1996, 1998, 2010 and 2016). Its significance is tested by a conventional two-tailed Student’s t test. The spatial symmetric component between extreme IOD composites is defined as the arithmetic mean of the averaged EXpIOD and the reversed averaged EXnIOD, i.e., [EXpIOD + ( − EXnIOD)]/2, on each grid. Conversely, the spatial asymmetric component is defined as the difference between the averaged EXpIOD and the reversed averaged EXnIOD, i.e., [EXpIOD − ( − EXnIOD)], on each grid36,47. The so-derived pattern asymmetry manifests as contiguous areas with the same sign, indicating the places preferentially dominated by either positive or negative anomalies.

EOF analysis and metrics in CMIP models

For both observations and CMIP6 outputs, we perform EOF analysis to the SON-averaged field of variables (such as SSTA and rainfall anomaly) over the eastern TIO domain (85°–120°E, 0°–10°S), in which obvious asymmetry exists. The EOF analysis deconstructs the original field by EOF patterns and corresponding PCs, which are mutually orthogonal and could reconstruct the original field through the summation \({\sum }_{i=1}^{n}{EO}{F}_{i}\times P{C}_{i}\). Given so, we could reduce the dimensions of the problem by only preserving several leading modes. The long-term trend of input variables has been removed before the EOF analysis. Moderate modifications to the EOF domain yield very similar results.

The nonlinear behaviour of PCs in the phase space is determined by fitting the scattered data with a quadratic function \({{\rm{PC}}}2(t)=\alpha {[{{\rm{PC}}}1(t)]}^{2}+\beta {{\rm{PC}}}1(t)+\gamma\), in which \(\alpha\) measures the nonlinearity35. The same EOF domain is applied for CMIP6 models, and thus α and the pattern correlation of EOF2 (Rp) with the observation (OISSTv2) are obtained for each model (Supplementary Table 1).

Mixed-layer heat budget analysis

Mixed-layer heat budget analysis is conducted to show the physical processes accounting for the formation of spatial asymmetry. The mixed-layer temperature (MLT) equation can be written as:

where overbars, primes and subscripts represent climatological means, anomalies and partial derivatives, respectively. \(T\), \(u\), \(v\) and \(w\) are the oceanic temperature, zonal, meridional and vertical velocities, respectively, and they are vertically averaged over the mixed-layer depth. Here, the mixed-layer depth, which is directly offered by ECCO2, is defined using the density-based criterion with ΔT = 0.8 °C48. In the main text, for simplicity, the anomalous MLT (\(T^{\prime}\)) is regarded as a valid proxy for SSTA. The terms in the first parenthesis represent zonal, meridional, and vertical nonlinear temperature advection processes (NA) by anomalous currents advecting anomalous SST, while those in the second are linearised advection (LA) processes, representing anomalous currents advecting mean SST and mean currents advecting SSTA. \({Q}_{{net}}^{\prime }\) denotes the net surface heat flux that has been converted to the unit °C month-1, which is the sum of shortwave radiation \({Q}_{{sw}}^{\prime }\) absorbed within the mixed-layer, longwave radiation \({Q}_{lw}^{\prime }\), latent heat flux \({Q}_{lh}^{\prime }\) and sensible heat flux \({Q}_{sh}^{\prime }\), and is positive when warms the ocean. The residual term (Res.) includes thermal effects caused by mixing, entrainment, and other subgrid-scale and sub-monthly nonlinear processes. Among these, entrainment has been noted in previous studies25,49 to contribute minimally to the interannual timescale, while the signals from mixing and sub-monthly processes cannot be accurately captured by our current monthly budget analysis25. A separate, more detailed model simulation that can resolve these small-scale and rapidly varying processes is underway.

For both EXpIOD and EXnIOD, events are diagnosed separately and then averaged according to phases. The asymmetric component of each budget term is defined as the difference between the averaged EXpIOD and the reversed averaged EXnIOD [i.e., EXpIOD − ( − EXnIOD)], as did in the composite analysis. For each budget term, its asymmetric component has a spatial distribution and is averaged in two boxes, one near Sumatra (95°–105°E, 7.5°S–0°) and one near Java (105°–115°E, 12°–7.5°S), to measure its contribution to the formation of the meridional pattern asymmetry.

Latent heat flux decomposition

Following the bulk formula, the latent heat flux is expressed as:

where \(\rho\), \({L}_{v}\) and \({C}_{e}\) denote the air density, the latent heat of vaporisation for seawater, and the transfer coefficient for latent heat, respectively. They are all assumed constant here. \({U}_{10}\) is the wind speed at 10 m. \({q}_{s}\) is the saturation specific humidity at the sea surface, and \({q}_{a}\) is the atmospheric near-surface specific humidity derived from the 2-m dewpoint temperature. By decomposing each variable into the climatological mean and anomalies, the relative contributions of \({U}_{10}\) and \(\Delta q\) to latent heat flux anomalies are estimated as:

The second-order perturbation has been neglected due to its small magnitude compared to the other terms. The two terms on the right-hand side denote the wind-driven and thermodynamic contributions to the latent heat flux, respectively. In response to a positive SSTA, the increased air–sea humidity gradient (\(\Delta {q}^{\prime } > 0\)) contributes to enhance evaporation and hence damp the original SSTA as a negative feedback. Conversely, for the case of the eastern TIO, wind speed is usually reduced (\({U}_{10}^{\prime } < 0\)) in response to a positive SSTA, which weakens evaporation and corresponds to a positive feedback on SSTA.

Model experiments

To investigate the atmospheric circulation response to the SSTAs of extreme IOD events, we performed five AGCM experiments using the Community Atmosphere Model version 5 (CAM5)50. In this study, the horizontal resolution of CAM5 is 1.9° × 2.5°, and the vertical coordinate is 30 hybrid sigma–pressure levels. The control run (CR) was forced by monthly SST climatology derived from HadISST51. In the two sensitive runs (ObsEXp and ObsEXn), the observed composite monthly SSTAs over the TIO (40°–120°E, 15°S–15°N; excluding the South China Sea) of the EXpIOD and the EXnIOD were added respectively onto the climatological SST from May to the following April. A sponge layer with a width of 5° was set at the surrounding boundaries. In both experiments, the model was integrated for 30 years, and the ensemble mean of the last 20 years was used in this study. Since the atmospheric model has a short memory of initial conditions, each year’s response to the given SST forcing can be considered as an independent ensemble member52, meaning each experiment includes 20 ensemble members. The impact of extreme IOD events was estimated by the difference between the sensitive run and the control run.

To demonstrate that the pronounced atmospheric responses favouring Sumatra are not driven by any subtle asymmetry between the EXpIOD and EXnIOD SSTA patterns observed in JA, we conducted two additional symmetric experiments (SymEXp and SymEXn). These experiments used mirror-like SSTAs with the same pattern and amplitude for both EXpIOD and EXnIOD but of opposite signs. The symmetric SSTA forcing was obtained by averaging the EXpIOD and the reversed EXnIOD (i.e., [EXpIOD + ( − EXnIOD)]/2) on each grid. Other configurations matched their respective sensitive runs. In these experiments, the effect of any pre-existing amplitude and pattern asymmetries in SSTAs was largely reduced. These two experiments show that even with a symmetric SST forcing pattern, the atmospheric responses to opposite-sign SSTAs are still spatially asymmetric, and wind anomalies are anchored off Sumatra rather than Java, providing a favourable condition for upwelling.

We also used the linear continuously stratified ocean model (LCSM) to quantify the effect of the remote and the local wind forcing on the sea-level variability30,53. Three different types of wind forcing during July–August were designed to force the ocean model. In the first and the second experiments, wind forcing was isolated to either the remote (70°–95°E, 5°S–5°N) or the local (95°–120°E, 15°S–0°) regions. On the other hand, we incorporated both the remote and local wind forcing in the third experiment. The model is launched from a state of rest with a realistic background stratification, and a flat ocean bottom is assumed. In this paper, the first 25 baroclinic modes are used, and the horizontal resolution is set to 0.25°. By incorporating observed wind stress anomalies during extreme IOD events, any effects of amplitude asymmetry or spatial pattern asymmetry between EXpIOD and EXnIOD in the wind field are thus accounted for.

CHHEXs in observations and CMIP6 models

The CHHEX is the intersection of MHWs regarding SST variations and HEXs regarding sea-level variations. First, MHWs are defined as monthly area-mean SSTA exceeding +1.65 standard deviations. SSTA is concerned here because the temperature departure from the seasonal cycle is important to induce abnormal behaviours in the seasonal spawning, breeding and migration of marine species. However, the rising trend of SST is excluded here as we do not study the adaptation of marine species to global warming within such a short period (1993–2021). Second, HEXs are defined as monthly SLAs exceeding +1.65 standard deviations. The seasonal cycle and trend in SLAs are retained, since the risk of coastal inundation and damages to infrastructure, drainage, and terrestrial water resources all depend on the magnitude of the total SLA. By the above definitions, CHHEXs detected here are almost the same as Han et al.19 for the period 1993–2021. As all observed CHHEXs occurred in boreal summer–winter coincided with EXnIOD events, we only look into the IOD mature phase (i.e., averaged over SON) for simplicity when analysing CMIP6 models.

A threshold, the 90th percentile, is often adopted to define MHWs54. However, it may not be optimal for the present study, due to the fact that the 90th percentile would fix the number of extreme events that can be selected, especially for our model analysis (i.e., 10% × 165 years = 16 times for both Java and Sumatra). In this study, we intend to emphasize the contrast in the intensity and frequency of MHWs and CHHEXs between coastal Java and Sumatra across Indonesia. Therefore, a relative threshold, 1.65 standard deviations, is used here. The number 1.65 is adopted as it corresponds to the upper 95th percentile in a Gaussian distribution, which fully reflects the extremity. Other thresholds ranging from 1.5 to 1.65 will not change the contrast in MHW frequency between Java and Sumatra.

Data availability

Data relevant to this study can be downloaded from the following websites: OISSTv2 at http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/thredds/wcs/Datasets/noaa.oisst.v2/sst.mnmean.nc; GPCP at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.gpcp.html; ECCO2 at https://www.ecco-group.org/data.htm; AVSIO at https://www.aviso.altimetry.fr/en/data/data-access.html; ERA5 at https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/dataset/ecmwf-reanalysis-v5; CMIP6 database at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip6/. Source data for figures (Figs. 1–5) can be found in the on-line open-access repository at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28425455.v1.

Code availability

The codes used to perform the analysis are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Saji, N. H., Goswami, B. N., Vinayachandran, P. N. & Yamagata, T. A dipole mode in the tropical Indian Ocean. Nature 401, 360–363 (1999).

Webster, P. J., Moore, A. M., Loschnigg, J. P. & Leben, R. R. Coupled ocean–atmosphere dynamics in the Indian Ocean during 1997–98. Nature 401, 356–360 (1999).

Ashok, K., Guan, Z. & Yamagata, T. A look at the relationship between the ENSO and the Indian Ocean dipole. J. Meteor. Soc. Jpn. 81, 41–56 (2003).

Li, T., Wang, B., Chang, C. P. & Zhang, Y. A Theory for the Indian Ocean dipole–zonal mode. J. Atmos. Sci. 60, 2119–2135 (2003).

Schott, F. A., Xie, S.-P. & McCreary, Jr. J. P. Indian Ocean circulation and climate variability. Rev. Geophys. 47, RG1002 (2009).

Saji, N. H. & Yamagata, T. Possible impacts of Indian Ocean dipole mode events on global climate. Clim. Res. 25, 151–169 (2003).

Cai, W., van Rensch, P., Cowan, T. & Hendon, H. H. Teleconnection Pathways of ENSO and the IOD and the Mechanisms for Impacts on Australian Rainfall. J. Clim. 24, 3910–3923 (2011).

Emmanuel, S. C. Impact to lung health of haze from forest fires: The Singapore experience. Respirology 5, 175–182 (2000).

Hashizume, M., Chaves, L. F. & Minakawa, N. Indian Ocean Dipole drives malaria resurgence in East African highlands. Sci. Rep. 2, 269 (2012).

Valsala, V., Sreeush, M. G. & Chakraborty, K. The IOD impacts on the Indian Ocean carbon cycle. J. Geophys Res Oceans 125, e2020JC016485 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Enhanced India-Africa carbon uptake and Asia-Pacific carbon release associated with the 2019 extreme positive Indian Ocean dipole. Geophys Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100950 (2022).

Luo, J.-J. et al. Interaction between El Niño and extreme Indian Ocean dipole. J. Clim. 23, 726–742 (2010).

Wang, J.-Z. & Wang, C. Joint boost to super El Niño from the Indian and Atlantic Oceans. J. Clim. 34, 4937–4954 (2021).

Zhang, L. & Han, W. Indian Ocean dipole leads to Atlantic Niño. Nat. Commun. 12, 5952 (2021).

Abram, N. J., Gagan, M. K., McCulloch, M. T., Chappell, J. & Hantoro, W. S. Coral reef death during the 1997 Indian Ocean dipole linked to Indonesian wildfires. Science 301, 952–955 (2003).

Wang, G. & Cai, W. Two-year consecutive concurrences of positive Indian Ocean Dipole and Central Pacific El Niño preconditioned the 2019/2020 Australian “black summer” bushfires. Geosci. Lett. 7, 19 (2020).

Ratna, S. B., Cherchi, A., Osborn, T. J., Joshi, M. & Uppara, U. The extreme positive Indian Ocean dipole of 2019 and associated Indian summer monsoon rainfall response. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091497 (2021).

Yang, H. & Huntingford, C. Brief communication: drought likelihood for East Africa. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 491–497 (2018).

Han, W. et al. Sea level extremes and compounding marine heatwaves in coastal Indonesia. Nat. Commun. 13, 6410 (2022).

Cai, W., van Rensch, P., Cowan, T. & Hendon, H. H. An asymmetry in the IOD and ENSO teleconnection pathway and its impact on Australian climate. J. Clim. 25, 6318–6329 (2012).

Behera, S. K. & Ratnam, J. V. Quasi-asymmetric response of the Indian summer monsoon rainfall to opposite phases of the IOD. Sci. Rep. 8, 123 (2018).

Hong, C.-C., Li, T., LinHo & Kug, J.-S. Asymmetry of the Indian Ocean dipole. Part I: observational analysis. J. Clim. 21, 4834–4848 (2008).

Cai, W. & Qiu, Y. An observation-based assessment of nonlinear feedback processes associated with the Indian Ocean dipole. J. Clim. 26, 2880–2890 (2013).

Ogata, T., Xie, S.-P., Lan, J. & Zheng, X. Importance of ocean dynamics for the skewness of the Indian Ocean dipole mode. J. Clim. 26, 2145–2159 (2013).

Nakazato, M., Kido, S. & Tozuka, T. Mechanisms of asymmetry in sea surface temperature anomalies associated with the Indian Ocean dipole revealed by closed heat budget. Sci. Rep. 11, 22546 (2021).

Susanto, R. D., Gordon, A. L. & Zheng, Q. Upwelling along the coasts of Java and Sumatra and its relation to ENSO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 1599–1602 (2001).

Chen, G., Han, W., Li, Y. & Wang, D. Interannual variability of equatorial eastern Indian Ocean upwelling: local versus remote forcing. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 46, 789–807 (2016).

Horii, T., Siswanto, E., Iskandar, I., Ueki, I. & Ando, K. Can coastal upwelling trigger a climate mode? A study on intraseasonal-scale coastal upwelling off Java and the Indian Ocean dipole. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098733 (2022).

Lee, S.-K. et al. Java–Sumatra Niño/Niña and its impact on regional rainfall variability. J. Clim. 35, 4291–4308 (2022).

McCreary, J. P. & Lighthill, M. J. A linear stratified ocean model of the coastal undercurrent. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A, Math. Phys. Sci. 302, 385–413 (1981).

Soares, J., Wainer, I. & Wells, N. C. Reflection of equatorial Kelvin waves at eastern ocean boundaries Part I: hypothetical boundaries. Ann. Geophys. 17, 812–826 (1999).

Adyasari, D. et al. Anthropogenic impact on Indonesian coastal water and ecosystems: current status and future opportunities. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 171, 112689 (2021).

Zheng, X.-T., Xie, S.-P., Vecchi, G. A., Liu, Q. & Hafner J. Indian Ocean dipole response to global warming: analysis of ocean–atmospheric feedbacks in a coupled model. J. Clim. 23, 1240–1253 (2010).

Cai, W. et al. Increased frequency of extreme Indian Ocean Dipole events due to greenhouse warming. Nature 510, 254–258 (2014).

Yang, K. et al. Oceanic processes in ocean temperature products key to a realistic presentation of positive Indian Ocean dipole nonlinearity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089396 (2020).

Dommenget, D., Bayr, T. & Frauen, C. Analysis of the non-linearity in the pattern and time evolution of El Niño southern oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 40, 2825–2847 (2013).

Dsikowitzky, L. et al. Chapter 21 —Java Island, Indonesia. In: World Seas: an Environmental Evaluation, second edn. (ed. Sheppard, C.) 459–490 (Academic Press, 2019).

Marfai, M. A. et al. Natural hazards in Central Java Province, Indonesia: an overview. Environ. Geol. 56, 335–351 (2008).

Lovelock, C. E. et al. The vulnerability of Indo-Pacific mangrove forests to sea-level rise. Nature 526, 559–563 (2015).

Ng, B. & Cai, W. Present-day zonal wind influences projected Indian Ocean dipole skewness. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 11,392–311,399 (2016).

Reynolds, R. W., Rayner, N. A., Smith, T. M., Stokes, D. C. & Wang, W. An improved in situ and satellite SST analysis for climate. J. Clim. 15, 1609–1625 (2002).

Adler, R. F. et al. The version-2 Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) monthly precipitation analysis (1979–present). J. Hydrometeorol. 4, 1147–1167 (2003).

Menemenlis, D. et al. ECCO2: high resolution global ocean and sea ice data synthesis. Mercato. Ocean Q. Newsl. 31, 13–21 (2008).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quart. J. R. Meteor. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Taburet, G. et al. DUACS DT2018: 25 years of reprocessed sea level altimetry products. Ocean Sci. 15, 1207–1224 (2019).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Wu, B., Li, T. & Zhou, T. Asymmetry of atmospheric circulation anomalies over the Western North Pacific between El Niño and La Niña. J. Clim. 23, 4807–4822 (2010).

Kara, A. B., Rochford, P. A. & Hurlburt, H. E. An optimal definition for ocean mixed layer depth. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 105, 16803–16821 (2000).

Halkides, D. J. & Lee, T. Mechanisms controlling seasonal-to-interannual mixed layer temperature variability in the southeastern tropical Indian Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 114, C02012 (2009).

Neale, R. B. et al. Description of the NCAR community atmosphere model (CAM 5.0). NCAR Tech. Note NCAR/TN-486+ STR 1, 1–12 (2010).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 4407 (2003).

Zhang, L., Han, W. & Hu, Z.-Z. Interbasin and multiple-time-scale interactions in generating the 2019 extreme Indian Ocean dipole. J. Clim. 34, 4553–4566 (2021).

Han, W. Origins and dynamics of the 90-day and 30–60-day variations in the equatorial Indian Ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 35, 708–728 (2005).

Hobday, A. J. et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr. 141, 227–238 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundations of China (42376021, 42306001, W2441014, 42192564, 42206026), the GuangDong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2024B1515040024), the Development fund (SCSIO202203) and Special fund (SCSIO2023QY01) of South China Sea Institute of Oceanology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. W.H. was supported by NSF OCE 2242193.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.-Z.W. conceived the original idea. M.X., J.-Z.W. and L.Z. designed this study. M.X. performed the analysis, created the figures and wrote the initial draft with support from J.-Z.W. L.Z. coordinated the entire research project. W.H. provided significant guidance throughout the interpretation and writing processes. H.F. conducted the AGCM experiments. H.L. carried out the LCSM experiments. M.X., J.-Z.W., L.Z., W.H. and C.W. contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. W.H. is an Editorial Board Member for Communications Earth & Environment, but was not involved in the editorial review of, nor the decision to publish this article.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Joe Aslin. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, M., Wang, JZ., Zhang, L. et al. Pattern asymmetry in extreme Indian Ocean dipoles shapes marine heat-height compound extremes around coastal Indonesia. Commun Earth Environ 6, 229 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02184-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02184-6