Abstract

Machine learning models can predict laboratory earthquakes using Acoustic emission, the lab equivalent of microseismicity, and changes in fault zone elastic properties during the lab seismic cycle. Applying them to natural earthquakes requires testing their generalizability across lab settings and stress conditions. Here, we show a fine-tuned convolutional neural network (CNN) model effectively transfer across different conditions. Our model employs techniques from natural language processing, including decoder techniques, to capture the relationship between AE and fault stress. We fine-tune the regression head of a deep CNN while fixing the decoder’s weights and successfully predict lab seismic events for a range of conditions. With fine-tuning, CNN models trained on one lab fault configuration predict time to failure and shear stress for another configuration at varying fault slip rates. These results demonstrate the potential of extending lab-based methods to different conditions that could eventually include tectonic earthquakes and seismic forecasting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Enhanced abilities to predict geohazards bear substantial societal and economic benefits1. Geoscientists and engineers have long been interested in predicting catastrophic events like earthquakes, with the hope of understanding their mechanisms and mitigating associated hazards. Laboratory studies simulating seismic events have played a central role in earthquake physics, providing insight into the importance of stress drop and dynamic rupture physics2. Therefore, data on lab earthquakes have been adopted to check the applicability of machine learning (ML) to earthquake prediction3. Existing studies show that ML algorithms can use acoustic emissions (AE) and other data sets including seismic wave speed, spectral amplitude, and frequency-magnitude statistics to effectively forecast fault zone stress state and the timing and magnitude of laboratory earthquakes4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. The success implies that microearthquakes (AE) early in the seismic cycle contain information about future fault ruptures24,25.

However, while a few studies have addressed the challenge26,27,28, direct application of machine learning to natural earthquakes faces considerable issues, including the scarcity of seismic data covering multiple seismic cycles29. In contrast to the controlled conditions of laboratory experiments where 100’s of seismic cycles can be studied, tectonic faults are more complex, and data rarely include more than a single seismic cycle. The recurrence intervals of natural faults often span decades or centuries, making it impractical to accumulate sufficient seismic data for training ML models4,29,30,31. Thus, the logical alternative involves adapting models trained on laboratory data or numerical simulations to real-world scenarios, and for this purpose the integration of deep neural networks with fine-tuning techniques32,33,34,35,36,37 is a promising solution. Such models are akin to natural language processing methods that include extensive training to identify and learn the critical patterns indicative of future events. For our purpose, the fine-tuning process across varied conditions and settings is crucial to build adaptable models that might generalize laboratory-derived insights to real-world conditions. Such an approach would bridge the gap between simulated faults in the laboratory and their natural counterparts, leveraging the strengths of machine learning to enhance our understanding and forecasting capabilities in seismology.

However, current methods for predicting laboratory earthquakes, particularly in demonstrating the generalizability of ML models, face notable challenges. To date, one of the few attempts in this direction involves a model initially trained on numerical simulations and applied to lab experiments to illustrate the potential of using such models with fine-tuning for application to Earth29. However, this approach is limited because it involves yet another step, based on numerical simulations, rather than direct experimentation or the use of field data. This highlights the need, as a first step, to develop ML models that transfer across diverse lab configurations and conditions. In particular, many studies have focused on just one type of test using double-direct-shear (DDS). There is a need to expand these methods to a broader array of lab approaches, such as biaxial-loading and triaxial tests, which have played a key role in developing our current understanding of earthquake physics38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49.

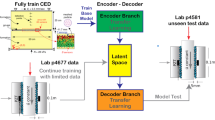

Here, we develop a deep learning (DL) convolutional model using AE signals from lab earthquakes in the DDS configuration and also for larger samples sheared under biaxial loading. Our model uses a decoder-only architecture and is designed to learn from and interpret the time-varying AE signals for predicting the evolving shear stress during seismic cycles. Initially, the model is trained on data from DDS experiments, establishing a mapping between AE signals and shear stress states. Subsequently, the majority of the model (~97%, encompassing the decoder architecture) is fixed, with only the remaining layers (constituting about 3%) retrained using limited data from other types of shear experiments. There are unavoidable trade-offs between freezing components of the network and fine-tuning. We explored a range of values and found that this approach works the best (see Methods for further information). Fine-tuning enables the model to predict various outcomes, such as friction coefficient and time to failure, in previously unseen data. We propose that our method could be pivotal in adapting data-driven techniques, successful in lab settings for predicting fault-slip characteristics, to real-world earthquake scenarios. The purpose of this paper is to describe this transfer learning approach and demonstrate its effectiveness in predicting laboratory earthquake events across different experimental configurations and conditions of stress, slip rate, and fault zone properties.

Results

Biaxial-loading experiments

The biaxial-loading experiments use a 500 mm × 500 mm × 20 mm polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) plate with an inclined fault, and a layer of simulated fault gouge with mean particle size of 0.325 mm (Supplementary Fig. 1). The fault is loaded under biaxial stresses in a servo-controlled machine with four hydraulic rams. Following a standardized procedure for reproducibility47, we apply loads slowly using both the horizontal (\({\upsigma }_{{\rm{x}}}\)) and vertical (\({\upsigma }_{{\rm{y}}}\)) rams to establish fault normal stresses that are initially 1 MPa (Fig. 1). After maintaining these stresses for 15 min, the horizontal stress \({\upsigma }_{{\rm{x}}}\) is held constant while the vertical load ram is advanced at 0.12 mm/min using displacement-controlled mode. This process increases the differential stress (\({\upsigma }_{{\rm{y}}}-{\upsigma }_{{\rm{x}}}\)), which is measured with load cells to a resolution of 0.005 MPa. The ram displacement is measured to 1 μm accuracy. All mechanical data are recorded at 100 Hz.

The upper panel shows the portion (red box) we studied. The lower panel illustrates the temporal evolution of Force_x (in green), Force_y (in blue), and Displacement_y (in red) for a fault zone shearing rate of 0.12 mm/min. The horizontal force, Force_x, remains consistent during non-slip stages, and exhibits disturbances during slip events.

The increasing differential stress increases fault zone shear stress, which triggers stick-slip events, releasing the accumulated stress (Fig. 1). The slip events are the lab equivalent of earthquakes and we monitor them using a lab seismometer consisting of a PZT sensor (300 kHz central frequency and 0.312 inch in diameter) from Physical Acoustics Corporation, positioned near the fault (Supplementary Fig. 2). The lab seismic signals are recorded at 2 MHz, throughout each experiment. An additional sensor synchronizes data from the mechanical and acoustic systems. The biaxial loading dataset in this study includes hundreds of lab earthquakes with continuous seismic records of acoustic emissions (Fig. 1). We focus on 21 stick-slip cycles over a period of 400 s, which includes approximately 800 million AE signals and 40,000 mechanical data of forces and displacement.

Double-direct-shear (DDS) experiments

In addition to the primary dataset used for training our CNN, we also used lab data from another configuration10,23. Those experiments used a double direct shear configuration and they provide additional data to assess the generalizability of our model across different types of laboratory earthquake data. We used data that are freely available and have been used in ML competitions50 designed to encourage broad participation of ML experts. These data enabled us to apply large-scale, pretrained models to different experimental scenarios.

The DDS experiments involve shearing two fault zones simultaneously between three blocks, using different granular materials. For our study, we focused on experiments p4581 (glass beads), p4679, and p5198 (both quartz powder), which have been used in previous ML/DL research (e.g., Bolton et al., 2021, Laurenti et al., 2022). This allows for a direct comparison of our methods with previous work. Details of the experiments are summarized in Table S1.

Performance of model across different datasets

We use data from both types of laboratory experiments to train a deep convolutional model with a decoder-only architecture (see Methods section for details). The model is trained with a regression-based supervised learning approach, focusing on predicting key slip characteristics like shear stress and time to failure by analyzing the AE signals from the experiments.

As a baseline, we assess the model’s performance by training and validating it exclusively on DDS data, followed by testing its efficacy on the biaxial-loading experiment data. Notably, during its training with DDS data, the model does not see any data from the biaxial experiment. The results of Fig. 2. showcase the model’s ability to generalize across different apparatuses. Note that our DL model successfully applies DDS-trained insights to the biaxial dataset. However, transferability is not always consistent. For instance, a model trained on biaxial-loading data shows poor performance when applied to the DDS dataset p4679. Rather than pinpointing a specific cause for this variation, these results underscore the nuanced and complex nature of seismic data. Each dataset possesses unique characteristics that may affect model performance in complex ways (Fig. 3). The DDS dataset, for example, includes certain patterns that are not as prevalent in our biaxial-loading data. These distinctions highlight the intricacies involved in training models that can accurately interpret diverse seismic datasets. As such, our findings illuminate the need for further research to unravel these complexities and enhance the robustness of predictive models in seismology.

a The model, trained on the DDS dataset p4679, accurately predicts seismic events in the biaxial-loading experiment. Notably, it effectively forecasts the third event in the biaxial dataset, despite its unusually small magnitude, demonstrating the model’s robust generalization across diverse seismic scenarios. b Conversely, the model trained on the biaxial dataset performs poorly when applied to the DDS dataset p4679. This illustrates the limitations in the generalization capabilities of deep learning models, highlighting that effective transfer typically occurs from complex to simpler datasets.

Initially, the model is pre-trained using the continuous AE signal from the biaxial-loading dataset, with shear force as the target. Post-pretraining, the first five layers of decoder of the deep convolutional model are kept and fixed, and only the Regression Head, constituting 3% of the total model weight, undergoes fine-tuning. This fine-tuning is carried out with a subset of DDS datasets, targeting different parameters like shear stress and time to failure. Finally, the fine-tuned model is applied to predict the remaining DDS datasets.

The model’s transferability is also influenced by variations in the lab seismic cycles. For instance, when applying the pretrained model to another DDS dataset (p4581) its performance markedly drops (see the red curve in Fig. 4). This decline can be attributed to the differing fault zone materials and character of the seismic cycles across the datasets. DDS dataset p4679 has an average repeat cycle of 35 s, which reduces to ~17.5 s when pre-slips are considered as minor slip events. This is relatively close to the biaxial dataset’s average cycle of 20 s, allowing for effective cross-experimental application. In contrast, datasets p4581 and p5198 have a much shorter average cycle of 6 s, which is less than a third of the biaxial experiment’s cycle length. These discrepancies in repeat cycles, possibly due to variations in normal stress, displacement rate, and other experimental conditions51, hinder the model’s direct applicability to these datasets.

To address this, we implement a fine-tuning method, akin to techniques used in image recognition and natural language processing. Fine-tuning involves adapting a pre-trained model to a new task by updating its parameters through minor additional training on the target task data52,53. This process typically starts with a large-scale pre-trained model, often referred to as the base model, which has been trained on a massive dataset to learn general features and representations. By initializing the target task model with the weights of the base model and subsequently updating them during the further training on the new task, the model can efficiently learn task-specific features, often requiring less data and training time compared to training from scratch54. A famous example is GPT-3, which is pretrained on vast text data and then fine-tuned for specific applications, like GitHub Copilot when fine-tuned with programming or ChatGPT55,56 when fine-tuned with human instructions.

In our approach, we fine-tuned the Regression Head of the deep convolutional model (the layers following the decoder) with new DDS data, while fixing the decoder’s weights trained on biaxial-loading data. We adjust the decoder to match the differing time scales of the two datasets (Supplementary Table 1). This decoder comprises several layers, each of which is composed of a Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) block57 containing dilated convolutional layers (details can be found in the Methods). The dilation factor of each layer increases exponentially as the depth of the network grows, allowing for a substantial expansion of the decoder’s receptive field to capture and process information from longer sequences. For shorter sequences like the DDS dataset p4581, we retain only the initial layers, reducing the receptive field to suit the dataset’s characteristics. Our model originally includes 9 layers, suitable for the biaxial dataset. When adapting to DDS data, we utilize only the first five layers, aligning with the sequence length and complexity of the DDS data. It’s important to note that weights of the first five layers are fixed in post-training on biaxial data and remain nontrainable during fine-tuning with DDS data, with only the Regression Head being adjustable. This fine-tuning process is illustrated in Fig. 3. In the pretraining phase, usually 70% of the data are used as the training set, while in the fine-tuning stage, only ~50% of the data are required. Furthermore, the adaptability of our model to different datasets is achieved by fine-tuning only a small fraction of the model, i.e., the Regression Head that comprises just 3.3% of the total model weights. This demonstrates the model’s flexibility, where minor modifications can effectively tailor it for varied datasets with reduced dataset size, while the majority of the model (i.e., the decoder) remains unchanged, as shown in Fig. 3.

To provide a direct comparison, we utilize datasets p4581 and p5198, previously studied15, and apply the same metric, Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) as in the previous work for consistency. The results with finetuning are shown in Fig. 5a. Remarkably, our model, with 97% of its weights derived from the biaxial dataset and only 3% fine-tuned with the DDS data, achieves RMSE metrics comparable to models trained exclusively on DDS data. This underscores the efficiency of our CNN and decoder based fine-tuning approach.

a displays predictions for shear stress, (b) the time to the start of failure (TTsF), defined as the time of maximum shear stress preceding slips, and (c) the time to the end of failure (TTeF), defined as the time of minimum shear stress after slips. The left-side figures represent results from our fine-tuned model, while the right-side figures compare these with results from a model fully trained on the same dataset in a previous study15. The evaluation metric utilizes RMSE for direct comparison. Results demonstrate that our model, initially pretrained on the biaxial loading dataset and fine-tuned with only 3% of its total weights on the new datasets, performs nearly as well as a model entirely trained on these datasets.

Moreover, our method demonstrates an ability to extend learning capabilities. Initially, the model is trained to predict shear force in the biaxial dataset. However, after fine-tuning with DDS data, it adeptly predicts new targets like Time to end of Failure (TTeF) and Time to start of Failure (TTsF), as shown in Fig. 5b, c. These targets, absent in the biaxial dataset, are learned effectively through fine-tuning, despite the pretrained model having no prior exposure to them. The success of these predictions, achieved by adjusting only the Regression Head – a mere 3% of the model’s total weight – highlights our model’s flexibility in adapting and potential for applications to different conditions.

Discussion

Our study validates previous machine learning results for lab earthquake prediction and extends those works to predict results of different experiments. This is a breakthrough in generalizing ML/DL methods for broader application to lab earthquakes. Moreover, the successful application of a model, pretrained on DDS dataset p4679, to biaxial-loading data demonstrates its cross-apparatus generalization ability. However, when the direction is reversed, the results are less predictable. This suggests a nuanced landscape of deep learning where the intricate nature of one dataset may not uniformly translate to the competency in another.

The mechanism enabling our model’s cross-experimental transferability, while not entirely transparent, is likely rooted in the shared characteristics of the lab earthquakes. In both biaxial-loading and direct shear tests, we see similar patterns of stress accumulation and release, coupled with consistent relationships between microearthquakes (AE) occurring within the fault zone prior to macroscopic failure and slip characteristics during the labquakes. This commonality likely plays a key role in the model’s ability to adapt across different types of experiments. Supporting this hypothesis, numerous laboratory studies spanning various testing apparatuses have consistently linked the evolution of acoustic emission signals with fault stick-slip behaviors16,21,22,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75. These studies reinforce the idea that the observed correlations between acoustic signals and seismic events are a fundamental aspect of seismic phenomena. Although the exact nature of these correlations cannot be explicitly outlined yet, they are implicitly captured and utilized by our deep learning model. This implicit understanding enables our deep learning model to successfully transfer and apply its learned insights across varying experimental contexts, despite differences in the specifics of each setup.

However, this transferability isn’t always reliable. When applied to other DDS datasets with substantially different repeat cycles, performance drops. The cycle length discrepancy affects the model’s applicability, illustrating the need for dataset-specific adjustments. Here, fine-tuning proves effective. Remarkably, a model trained on biaxial data with PMMA plates and corundum gouges, retaining 97% of its original weights, can adapt its regression head to new DDS datasets with different materials and settings. This results in successful predictions of various targets. This adaptability is also crucial in real-world scenarios, where the recurrence of large earthquakes is influenced by factors such as strain rate, kinematics, and tectonic setting76, introducing complexity and variability similar to lab quakes with varying repeat cycles77. Thus, the pretrain-finetuning strategy has the potential to be highly valuable for real-world earthquakes, allowing models to be refined based on the unique geological characteristics of different regions.

In summary, our deep convolutional model, enhanced by fine-tuning, shows promising results in bridging gaps between laboratory experiments and potential for extending lab-based models to tectonic faults. This progress is a crucial step towards using continuous seismic waves to predict seismogenic fault slips. Looking to the future, an essential strategy for effectively bridging the gap between simulated laboratory faults and natural faults involves creating laboratory datasets that encompass the broad spectrum of natural fault behaviors. By ensuring that these laboratory experiments mimic the complexity and diversity of natural fault activities, deep learning models can be better trained to apply insights from the lab to real-world scenarios. This approach aims to cover the full range of natural fault characteristics in laboratory settings, facilitating the transfer of model learning from controlled experiments to natural fault predictions.

Training a large, comprehensive model becomes essential in this context. The fine-tuning technique, applied to a small segment of this model, proves invaluable. It not only conserves time and resources by avoiding the need to extensively retrain the model with scarce seismic data, but also addresses the challenge posed by the vast difference in time scales between laboratory and natural seismic events. This approach of using a broadly trained deep learning model with targeted fine-tuning holds considerable promise for advancing our ability to predict natural earthquakes and other geohazards. Moreover, incorporating Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) could further enhance this process4. By integrating physical constraints into machine learning models, PINNs can substantially reduce the amount of required training data4. However, identifying appropriate physical constraints that are applicable in both laboratory and field settings remains a challenge.

Methods

Biaxial experiments

The biaxial laboratory data is from a servo-controlled loading machine with four independent hydraulic rams to apply stresses to the fault. Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) has been commonly used as an analog to rock material in laboratory earthquake investigations78,79,80. In this work, square PMMA plates with a dimension of 500 mm × 500 mm × 20 mm are used. PMMA has the physical and mechanical properties as follows: density ρ = 1190 kg/m3, the Young’s modulus E = 6.24 GPa, the shear modulus μ = 2.40 GPa, and the Poisson’s ratio ν = 0.3. The seismic wave velocities are CS = 1.43 km/s and CP = 2.40 km/s for plane stress conditions.

The square PMMA plate is cut diagonally into two identical triangular plates, using a computer-numerical control (CNC) engraving and milling machine. Then the cut faces are polished to remove the machining lines. Subsequently, a layer of fault gouge is evenly spread across the fault plane. The fault gouge consists of white corundum particles with a mean size of 0.325 mm. We selected it owing to its dense texture, hardness, and angular particle shape. The corundum particles simulate wear material found in tectonic fault zones. Upon shearing we observe 100’s of microearthquakes in the form of acoustic emission events, which mimic seismic activities in natural faults during tectonic movements.

Data preprocessing

The acoustic emission data used in this study, either from our experiments or from the previous work with the DDS configuration follows the same processing. It is first downsampled according to its sampling frequency. Earlier studies employed a moving window to calculate various statistical features within each window3. Among these features, signal energy has been recognized as the most important feature. Since variance is proportional to the acoustic energy release, we limit our computations to the variance within each window. However, one challenge with this variance-centric approach lies in its response during the slip stage of each seismic cycle, which witnesses a substantial surge in AE events. This surge causes the variance during this period to dwarf the rest of the time by several orders of magnitude. This imbalance poses a barrier for the deep learning model in learning inter-event representation. To address this, we propose to calculate the log value of the variance, which helps preserve the temporal evolution of AE variance during events while reducing the impact of extreme values. Other approaches are certainly possible, including the use of multiple features. In our experiments, the target data, shear force, is recorded at 100 Hz whereas acoustic signals are recorded at 2 MHz. To align with the target data, the time window is set to 0.1 s, equivalent to 200,000 points and the interval is chosen to be 0.01 s equivalent to 20,000 points. For DDS data, to better compare the finetuning results with those from the model entirely trained on DDS data, we use the exact same data that were used in the previous research15, with the same time window and sliding settings. The only difference is that we use the log value of the AE variance instead of the original AE variance that was used in previous study.

For target data in our experiment, we only use shear force as the target to train our model. There is no difference between using shear force or shear stress in the context of deep learning, especially since we scale the data in practice. The raw shear forces recorded in experiments are often laden with high-frequency noise that originates from both the system and the surrounding environment. To mitigate this noise, a common method is to employ a Butterworth low-pass filter. This method eliminates high-frequency noise while preserving the integrity of the original signal’s lower frequency components. The sampling frequency of shear force is 100 Hz, and the cutoff frequency of the filter is 15 Hz.

After the denoising step, the target data may still contain trends, which could be either linear or nonlinear, that arise from non-stationary experimental conditions or systemic drifts over time. These trends, if not accounted for, may overshadow the actual seismic patterns we are interested in and consequently interfere with model learning. Therefore, a common preprocessing step in time-series analysis is detrending, which involves removing these underlying trends from the data. A simple and commonly used method for detrending involves fitting a linear model to the whole target data and then subtracting the linear predictions from the original data. This method assumes that the trend is linear and can be captured using a simple linear model.

For the target data in DDS configuration, we directly used the same data that was used in previous study, to maintain the consistency for further comparison.

The Min-Max scaler is employed to normalize the entire dataset, ensuring that the input features fall within 0 and 1. To prevent data leakage, only the training set is utilized to fit the scaler.

Training, validation, and testing splits

Given the time-series nature of our dataset, it is crucial to preserve the temporal order during the data partitioning process. We therefore adopt a contiguous splitting approach. Moreover, the partitioning is taken based on events instead of percentiles to enhance the model’s ability to learn comprehensively from each seismic cycle. Taking our experiment as an example, the dataset contains 21 events. We designate the first 14 events as the training set, the 15th and 16th event as the validation set, and the remaining 5 events as the test set. The same contiguous partitioning is done to DDS datasets. When pretraining, the dataset of the biaxial experiment is partitioned into training, validation, and test sets with approximate ratios of 7:1:2, respectively. In contrast, during the finetuning phase on DDS datasets, the allocation differs, comprising approximately 50% for training, 10% for validation, and 40% for testing. Detailed specifications of the partitioning are provided in Supplement Table 2.

Deep convolutional neural network

Inspired by the recent advancements in large language models, our model is designed with a decoder-only structure81(See Supplementary Fig. 3). It begins with a BatchNorm1d layer to accelerate model training. The decoder, constituting the core of the model, is equipped with multiple layers. Each layer is one Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) block57, responsible for learning temporal patterns within the input sequence. Each TCN block consists of two identical dilated causal convolutions. The dilation factor is set to 2i for the i-th layer, where i = 0, 1, 2, …, N, indicating the index of the layer within the TCN. This results in an exponential increase of the dilation factor as the depth of the TCN layers increases, which allows the receptive field to grow rapidly while keeping the number of parameters manageable.

After the decoder there is the Regression Head. This is a 1D convolution layer with 64 output features. A kernel size of 2 is added to further refine the extracted features, i.e., consolidating them into a more informative representation. Subsequently, two linear layers with output dimensions of 128 and 1, respectively, are utilized to transform the refined feature representation, transitioning it into an appropriate latent space and ultimately map it to the target value.

Dropout layers are intentionally omitted in later layers, based on research findings that dropout may negatively impact regression tasks82,83. Overall, the model is designed with a flexible decoder. By changing the number of layers inside the decoder, it can be adapted to different input data sequence lengths.

Model training procedure

In pretraining, we use the AdamW optimizer and a cosine annealing schedule to double control the learning rate. The period of the cosine function is set to be 50. We also use a technique known as gradient clipping to prevent extreme fluctuations and keep gradients within a defined range to avoid gradient exploding issues which are common in very deep convolutional neural network training as applied to our case. The loss function is set to Mean Squared Error (MSE). We also use the early stopping mechanism to prevent overfitting. If the validation loss does not decrease for 20 consecutive epochs, training is terminated. We use the Xavier uniform distribution to initialize the weights of layers outside the decoder and set bias terms to zero. The batch size is set to 128. Finally, we pretrained the model using two RTX 4090 GPUs. Mixed-precision training and data parallelism were used. Mixed-precision training involves using both single-precision (float32) and half-precision (float16) formats in a way that optimizes the model’s speed and memory utilization without sacrificing its accuracy or stability.

In finetuning, the process is similar but much simpler. The AdamW optimizer is also used, with a batch size of 64 for the training and validation sets, and 1 for the test set to best simulate the real predicting scenario. The same learning rate scheduler and gradient clipping methods are applied. The loss function is set to be MSE.

The optimal hyperparameter configurations for both pretraining and finetuning are listed in Supplement Table 3.

To verify the contribution of the frozen decoder part in the finetuning, we conducted an ablation study. We compared it to two model variants, one with a randomly initialized decoder then frozen, and the other with a fully trainable decoder. Our pretrained then frozen decoder model achieves the lowest loss (see Supplementary Table 4) and stable convergence. This demonstrates that pre-trained features (1) accelerate model convergence relative to random initialization and (2) result in more accurate final predictions than full training from scratch in data-limited scenarios.

Data availability

The DDS data can be found at: https://github.com/lauralaurenti/DNN-earthquake-prediction-forecasting. The Biaxial data used in the paper can be found at https://github.com/CountofGlamorgan/TCN_paper.

Code availability

The source code and models can be accessed at https://github.com/CountofGlamorgan/TCN_paper.

References

Scholz, C. H. The mechanics of earthquakes and faulting (Cambridge university press, 2019).

Brace, W. F. & Byerlee, J. D. Stick-slip as a mechanism for earthquakes. Science 153, 990 (1966).

Rouet-Leduc, B, et al. Machine learning predicts laboratory earthquakes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 9276–9282 (2017).

Borate, P, et al. Using a physics-informed neural network and fault zone acoustic monitoring to predict lab earthquakes. Nat. Commun. 14, 3693 (2023).

Rouet-Leduc, B. et al. Estimating fault friction from seismic signals in the laboratory. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 1321–1329 (2018).

Lubbers, N. et al. Earthquake catalog-based machine learning identification of laboratory fault states and the effects of magnitude of completeness. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 13269–13276 (2018).

Jasperson, H. et al. Attention network forecasts time-to-failure in laboratory shear experiments. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2021JB022195 (2021).

Pu, Y., Chen, J. & Apel, D. B. Deep and confident prediction for a laboratory earthquake. Neural Comput. Appl. 33, 11691–11701 (2021).

Wang, K., Johnson, C. W., Bennett, K. C. & Johnson, P. A. Predicting future laboratory fault friction through deep learning transformer models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098233 (2022).

Shreedharan, S., Bolton, D. C., Rivière, J. & Marone, C. Machine learning predicts the timing and shear stress evolution of lab earthquakes using active seismic monitoring of fault zone processes. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2020JB021588 (2021).

Shokouhi, P. et al. Deep learning can predict laboratory quakes from active source seismic data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093187 (2021).

Mastella, G., Corbi, F., Bedford, J., Funiciello, F. & Rosenau, M. Forecasting surface velocity fields associated with laboratory seismic cycles using Deep Learning. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099632 (2022).

Corbi, F. et al. Machine learning can predict the timing and size of analog earthquakes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 1303–1311 (2019).

Corbi, F. et al. Predicting imminence of analog megathrust earthquakes with machine learning: Implications for monitoring subduction zones. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086615 (2020).

Laurenti, L., Tinti, E., Galasso, F., Franco, L. & Marone, C. Deep learning for laboratory earthquake prediction and autoregressive forecasting of fault zone stress. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 598, 117825 (2022).

Karimpouli, S. et al. Explainable machine learning for labquake prediction using catalog-driven features. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 622, 118383 (2023).

Delorey, A. A., Guyer, R. A., Bokelmann, G. H. & Johnson, P. A. Probing the damage zone at Parkfield. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093518 (2021).

Rubino, V., Rosakis, A. & Lapusta, N. Understanding dynamic friction through spontaneously evolving laboratory earthquakes. Nat. Commun. 8, 15991 (2017).

Rubino, V., Lapusta, N. & Rosakis, A. Intermittent lab earthquakes in dynamically weakening fault gouge. Nature 606, 922–929 (2022).

Hedayat, A., Pyrak-Nolte, L. J. & Bobet, A. Precursors to the shear failure of rock discontinuities. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 5467–5475 (2014).

Dresen, G., Kwiatek, G., Goebel, T. & Ben-Zion, Y. Seismic and aseismic preparatory processes before large stick–slip failure. Pure Appl. Geophys. 177, 5741–5760 (2020).

McBeck, J. A., Aiken, J. M., Mathiesen, J., Ben-Zion, Y. & Renard, F. Deformation precursors to catastrophic failure in rocks. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL090255 (2020).

Bolton, D. C., Shreedharan, S., Rivière, J. & Marone, C. Frequency-magnitude statistics of laboratory foreshocks vary with shear velocity, fault slip rate, and shear stress. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2021JB022175 (2021).

Bolton, D. C. et al. Characterizing acoustic signals and searching for precursors during the laboratory seismic cycle using unsupervised machine learning. Seismol. Res. Lett. 90, 1088–1098 (2019).

Bolton, D. C., Marone, C., Saffer, D. & Trugman, D. T. Foreshock properties illuminate nucleation processes of slow and fast laboratory earthquakes. Nat. Commun. 14, 3859 (2023).

Rouet-Leduc, B., Hulbert, C. & Johnson, P. A. Continuous chatter of the Cascadia subduction zone revealed by machine learning. Nat. Geosci. 12, 75–79 (2019).

Baiesi, M. & Paczuski, M. Complex networks of earthquakes and aftershocks. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 12, 1–11 (2005).

Ren, C. X. et al. Machine learning reveals the state of intermittent frictional dynamics in a sheared granular fault. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 7395–7403 (2019).

Wang, K., Johnson, C. W., Bennett, K. C. & Johnson, P. A. Predicting fault slip via transfer learning. Nat. Commun. 12, 7319 (2021).

Arrowsmith, S. J. et al. Big data seismology. Rev. Geophys. 60, e2021RG000769 (2022).

Segall, P., Matthews, M. V., Shelly, D. R., Wang, T. A. & Anderson, K. R. Stress-driven recurrence and precursory moment-rate surge in caldera collapse earthquakes. Nat. Geosci. 17, 264–269 (2024).

Jozinović, D., Lomax, A., Štajduhar, I. & Michelini, A. Transfer learning: Improving neural network based prediction of earthquake ground shaking for an area with insufficient training data. Geophys. J. Int. 229, 704–718 (2022).

Chai, C. et al. Using a deep neural network and transfer learning to bridge scales for seismic phase picking. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088651 (2020).

Lapins, S. et al. A little data goes a long way: automating seismic phase arrival picking at Nabro volcano with transfer learning. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2021JB021910 (2021).

Huynh, N. N. T., Martin, R., Oberlin, T. & Plazolles, B. Near-surface seismic arrival time picking with transfer and semi-supervised learning. Surveys Geophys. 44, 1837–1861 (2023).

Zhu, J. et al. Deep learning and transfer learning of earthquake and quarry-blast discrimination: applications to southern california and eastern kentucky. Geophys. J. Int. 236, 979–993 (2024).

Zhu, J., Li, S., Ma, Q., He, B. & Song, J. Support vector machine-based rapid magnitude estimation using transfer learning for the Sichuan–Yunnan Region, China. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 112, 894–904 (2022).

Scholz, C., Molnar, P. & Johnson, T. Detailed studies of frictional sliding of granite and implications for the earthquake mechanism. J. Geophys. Res. 77, 6392–6406 (1972).

Johnson, T., Wu, F. T. & Scholz, C. H. Source parameters for stick-slip and for earthquakes. Science 179, 278–280 (1973).

Dieterich, J. Preseismic fault slip and earthquake prediction. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 83, 3940–3948 (1978).

Mclaskey, G. C. & Yamashita, F. Slow and fast ruptures on a laboratory fault controlled by loading characteristics. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 122, 3719–3738 (2017).

McLaskey, G. C., Kilgore, B. D. & Beeler, N. M. Slip-pulse rupture behavior on a 2 m granite fault. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 7039–7045 (2015).

Okubo, P. G. & Dieterich, J. H. Fracture energy of stick-slip events in a large scale biaxial experiment. Geophys. Res. Lett. 8, 887–890 (1981).

Okubo, P. G. & Dieterich, J. H. Effects of physical fault properties on frictional instabilities produced on simulated faults. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 89, 5817–5827 (1984).

McLaskey, G. C. & Kilgore, B. D. Foreshocks during the nucleation of stick-slip instability. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 118, 2982–2997 (2013).

Ohnaka, M. & Shen, L. F. Scaling of the shear rupture process from nucleation to dynamic propagation: implications of geometric irregularity of the rupturing surfaces. J. Geophys Res. Solid Earth 104, 817–844 (1999).

Dong, P., Xia, K., Xu, Y., Elsworth, D. & Ampuero, J.-P. Laboratory earthquakes decipher control and stability of rupture speeds. Nat. Commun. 14, 2427 (2023).

Dong, P. et al. Earthquake delay and rupture velocity in near-field dynamic triggering dictated by stress-controlled nucleation. Seismol. Res. Lett. 94, 913–924(2022).

Yamashita, T. & Ohnaka, M. Nucleation process of unstable rupture in the brittle regime: a theoretical approach based on experimentally inferred relations. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 96, 8351–8367 (1991).

Johnson, P. A. et al. Laboratory earthquake forecasting: a machine learning competition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2011362118 (2021).

Karner, S. L. & Marone, C. Effects of loading rate and normal stress on stress drop and stick-slip recurrence interval. Geocomplex. Phys. Earthq. 120, 187–198 (2000).

Yosinski, J., Clune, J., Bengio, Y. & Lipson, H. How transferable are features in deep neural networks? Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 27, 3320–3328 (2014).

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proc. 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Vol. 1 (Long and Short Papers), 4171–4186, (Association for Computational Linguistics, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2019).

Huh, M., Agrawal, P. & Efros, A. A. What makes ImageNet good for transfer learning? arXiv preprint arXiv:1608.08614 (2016).

Radford, A., Narasimhan, K., Salimans, T. & Sutskever, I. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. (2018).

Radford, A. et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 1, 9 (2019).

Bai, S., Kolter, J. Z. & Koltun, V. An empirical evaluation of generic convolutional and recurrent networks for sequence modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.01271 (2018).

Marty, S. et al. Nucleation of laboratory earthquakes: quantitative analysis and scalings. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 128 https://doi.org/10.1029/2022jb026294 (2023).

Bolton, D. C., Shreedharan, S., Rivière, J. & Marone, C. Acoustic energy release during the laboratory seismic cycle: insights on laboratory earthquake precursors and prediction. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125 https://doi.org/10.1029/2019jb018975 (2020).

Shreedharan, S., Bolton, D. C., Rivière, J. & Marone, C. Preseismic fault creep and elastic wave amplitude precursors scale with lab earthquake magnitude for the continuum of tectonic failure modes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL086986 (2020).

McLaskey, G. C. & Lockner, D. A. Preslip and cascade processes initiating laboratory stick slip. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 119, 6323–6336 (2014).

Goebel, T. W., Schorlemmer, D., Becker, T., Dresen, G. & Sammis, C. Acoustic emissions document stress changes over many seismic cycles in stick-slip experiments. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 2049–2054 (2013).

Rivière, J., Lv, Z., Johnson, P. & Marone, C. Evolution of b-value during the seismic cycle: insights from laboratory experiments on simulated faults. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 482, 407–413 (2018).

Weeks, J., Lockner, D. & Byerlee, J. Change in b-values during movement on cut surfaces in granite. Bull. Seismological Soc. Am. 68, 333–341 (1978).

Lockner, D. The role of acoustic emission in the study of rock fracture. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 30, 883–899 (1993).

Ojala, I. O., Main, I. G. & Ngwenya, B. T. Strain rate and temperature dependence of Omori law scaling constants of AE data: implications for earthquake foreshock-aftershock sequences. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L24617 (2004).

Thompson, B., Young, R. & Lockner, D. A. Premonitory acoustic emissions and stick-slip in natural and smooth-faulted Westerly granite. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 114, B02205 (2009).

Johnson, P. A. et al. Acoustic emission and microslip precursors to stick-slip failure in sheared granular material. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 5627–5631 (2013).

Kaproth, B. M. & Marone, C. Slow earthquakes, preseismic velocity changes, and the origin of slow frictional stick-slip. Science 341, 1229–1232 (2013).

Kwiatek, G., Goebel, T. & Dresen, G. Seismic moment tensor and b value variations over successive seismic cycles in laboratory stick-slip experiments. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 5838–5846 (2014).

Goebel, T., Sammis, C., Becker, T., Dresen, G. & Schorlemmer, D. A comparison of seismicity characteristics and fault structure between stick–slip experiments and nature. Pure Appl. Geophys. 172, 2247–2264 (2015).

Goodfellow, S., Nasseri, M., Maxwell, S. & Young, R. Hydraulic fracture energy budget: insights from the laboratory. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 3179–3187 (2015).

Tinti, E. et al. On the evolution of elastic properties during laboratory stick-slip experiments spanning the transition from slow slip to dynamic rupture. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 121, 8569–8594 (2016).

Passelègue, F.X., Latour, S., Schubnel, A., Nielsen, S., Bhat, H.S. & Madariaga, R. Influence of fault strength on precursory processes during laboratory earthquakes. In Fault Zone Dynamic Processes (eds Thomas, M. Y., Mitchell T. M. & Bhat, H. S.) Ch. 12, 229–242 (2017).

Karimpouli, S., Kwiatek, G., Martínez-Garzón, P., Dresen, G. & Bohnhoff, M. Unsupervised clustering of catalog-driven features for characterizing temporal evolution of labquake stress. Geophys. J. Int., 237, 755–771 (2024).

Wang, T. et al. Earthquake forecasting from paleoseismic records. Nat. Commun. 15, 1944 (2024).

Gualandi, A., Faranda, D., Marone, C., Cocco, M. & Mengaldo, G. Deterministic and stochastic chaos characterize laboratory earthquakes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 604, 117995 (2023).

Svetlizky, I. & Fineberg, J. Classical shear cracks drive the onset of dry frictional motion. Nature 509, 205–208 (2014).

Cebry, S. B. L. & McLaskey, G. C. Seismic swarms produced by rapid fluid injection into a low permeability laboratory fault. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 557, 116726 (2021).

Guérin-Marthe, S., Nielsen, S., Bird, R., Giani, S. & Di Toro, G. Earthquake nucleation size: evidence of loading rate dependence in laboratory faults. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 124, 689–708 (2019).

Wang, T. et al. What language model architecture and pretraining objective works best for zero-shot generalization?. In Proc. 39th International Conference on Machine Learning, 22964–22984, Baltimore, Maryland, USA (PMLR, 2022).

Srivastava, N., Hinton, G., Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting. J. Mach. Learn Res. 15, 1929–1958 (2014).

Özgür, A. & Nar, F. Effect of Dropout layer on Classical Regression Problems. In 28th Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU), 1-4, Gaziantep, Turkey, (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by China Scholarship Council (Grant No. 201806080103), NSFC (Grant No.42174061 and No. 42141010). We would like to thank Dr. Peng Dong from China University of Geosciences (Beijing) and Mr. Ran Xu from Tianjin University for assistance in experiments. We would like to thank Prof. Xin Zhang from China University of Geosciences (Beijing) and Prof. Sebastian Goodfellow from University of Toronto for their constructive discussions. CM acknowledges support from European Research Council Advance grant 835012 (TECTONIC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.W.: experiments, conceptualization, methodology and writing—original draft. K.X.: conceptualization, writing—review & editing, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. W.Y.: methodology and writing—review. C.M.: conceptualization, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Sadegh Karimpouli and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Joe Aslin, Heike Langenberg. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Xia, K., Yao, W. et al. Generalizable deep learning models for predicting laboratory earthquakes. Commun Earth Environ 6, 219 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02200-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02200-9

This article is cited by

-

A comprehensive study on application of LSTM neural networks for radon-based earthquake anomaly detection in Istanbul

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2025)