Abstract

Foreign direct investment is a critical material extraction and revenue generation tool, but its role in reducing clean energy vulnerability is often overlooked. Here, we use the clean energy vulnerability index and explore how foreign direct investment mitigates energy shortages in countries abundant in critical materials such as bauxite, cobalt, nickel, manganese, and platinum. We found that from 2016 to 2021, foreign direct investment controlled large portions of critical materials in vulnerable countries, with 56% of bauxite, 59% of cobalt and nickel, 52% of manganese, and 57% of platinum. Redirecting 40% of foreign direct investment-controlled production towards the deployment of clean energy could reduce energy vulnerability in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Indonesia, South Africa, and Guinea. The foreign investment redirection could enhance global energy transition equity, offering a strategic pathway for aligning with sustainable energy goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The transition to clean energy, essential for addressing critical climate challenges, is advancing more rapidly in clean energy winners (countries that benefit from valuable renewable resources) than in clean energy losers (countries that possess essential materials for energy transition yet remain vulnerable) due to limited clean energy capacity1,2. Clean energy transition often requires several critical materials3 for lithium-ion batteries. Some critical materials are lithium, cobalt, nickel, and graphite4,5,6, platinum group of metals for electrolyzers and fuel cells7, and rare earth elements for permanent magnet motors and wind turbines8,9. Electric vehicles compared to conventional cars consume quantities of critical materials3, due to related batteries requiring lithium-ion chemistries, including lithium-ion-cathode (lithium nickel cobalt aluminum oxide, lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide, and lithium-ion phosphate)6. This stimulated the highest demand for these materials in clean energy winners (China, US,A and others)3,10 and some originated from clean energy losers, characterized by the least progress of energy transition11,12,13. However, clean energy losers would reasonably advance the energy system via their critical energy transition materials and overcome some crucial economic, geopolitical, environmental, and governance issues14.

Foreign direct investment (FDI)-related to critical energy transition materials has been employed as a material extractive, reducing supply disruption, and investors’ security15. Existing studies have concentrated on reducing supply risks of critical materials and batteries using various methods and proposed supply risk indices. From these studies, FDI reduces supply risks while increasing global material production6,16,17,18, material criticalities19, and artificial intelligence reduces technical and non-technical barriers to the investors20. However, most clean energy-deficient countries endowed with critical materials consider FDI-related mining projects as their main source of revenue (Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): 80%, Zambia: 75%, South Africa: 30%) rather than a means of clean energy development due to economic vulnerability3,21. Most of these countries remain highly vulnerable to challenges of clean energy transition22,23,24. This exacerbates the inequality to clean energy transition between material producers and consumers, which is linked to the use of FDI as a material extraction tool rather than clean energy development. The disparity in energy transition and trade networks between critical material producers and consumers can be observed in two ways: Firstly, global major critical materials are geographically concentrated in clean energy-vulnerable countries25, and their critical materials are heavily extracted through FDI from high-income economies that are clean energy winners and importing dependence12,18,26. There is evidence that 70% of global cobalt is produced from the DRC, 70% and 35.8% of platinum and manganese, respectively mined in South Africa, about 70% of global nickel is produced in Indonesia and New Caledonia27, while these countries are vulnerable for clean energy deployment28,29. These past findings highlighted a reasonable disparity in concentration geographically and end-use of critical materials and clean energy technologies. This underscores the potential need for a conceptual framework that could diversify global energy transition equity between countries rich in critical materials and clean energy winners via strategic FDI in both critical material production and energy development.

Secondly, material processing and refining capacity is concentrated in some high-/upper-income economies whose reasonable energy transition progress12,26, such as China, that processes 100% of global natural graphite and dysprosium, 90% of manganese, 70% of cobalt, and 58% of lithium27. Recent evidence shows that countries worldwide are vulnerable to post-clean energy material processing, battery, cell, and electric vehicle supply chains. China approximately controls about 80% of global cathode material production and lithium-ion chemistries18. Another crucial issue is that the global clean energy transition stimulated critical material demand while posing critical risks30,31,32,33. Since 2016, FDI controls over the mining sector, mainly mines of critical materials from clean energy losers, has increased due to key companies that hold all necessary resources and skills to advance multifaceted mines are mostly in clean energy winners (61% of lithium and 56% of cobalt controlled by five corporates)27. This has initiated the clean energy transition disparity between clean energy winners and losers. Continuous advancements in manufacturing capacity for clean energy materials, technology, electric vehicle batteries, and related chemistries, along with concentrated clean energy installation capacity in winning countries, have further intensified energy transition inequality. The current role of FDI diversifies critical materials and reduces supply risks globally16. However, the downstream benefits of critical materials, such as clean energy deployment, are largely concentrated in a set of a few countries that are heavily reliant on material imports. This inequity distribution leaves material-rich countries, despite their material endowments, at risk of deepened clean energy vulnerability. To the best of our knowledge, shifting from extractive FDI to clean energy development can mitigate clean energy vulnerability and ensure substantial energy transition equity among global countries. Redirecting a share of FDI-driven critical material extraction into clean energy projects can help boost energy capacity in material-rich but energy-vulnerable countries. This proposition can support carbon emissions reduction, thereby providing a substantial contribution to current clean energy projects34. Therefore, this study comprehensively assesses how FDI related to critical material extraction could mitigate clean energy vulnerability in material-rich but clean energy-vulnerable countries.

Here, we introduce the clean energy vulnerability index (CVI) to measure the vulnerability of critical material-rich countries to clean energy risks. By quantifying vulnerability among these countries, we provide a comprehensive framework for mitigating clean energy vulnerability via strategically redirecting FDI related to mining projects toward energy development. We quantified the disparities between critical material producers and consumers in terms of material concentration through FDI. These aims closely align with the United Nations Secretary-General’s panel on critical energy transition materials, which calls for equity, transparency, investment, and sustainability in benefiting material-rich countries35. This study suggests that bolstering clean energy capacity in clean energy-vulnerable countries can more equitably distribute the benefits of the global energy transition, although most of the critical material producers are vulnerable to lithium-ion battery supply risks18. To achieve this, we examine FDI-driven production of key materials: nickel, manganese, cobalt, platinum, and bauxite (primary ore of aluminum) globally between 2016 (beginning of FDI intensification)36 and 2021 (last data update37). These critical materials were selected for their crucial role in clean energy technology38,39, their reasonable FDI-driven production, and the fact that their home countries are largely vulnerable to clean energy transition transition22,23,24 and lithium-ion battery supply risks18. The analysis uses company-specific data to track production flows from origin (mines, operators) to consumers (shareholders), examining the geographic distribution and shareholder control in material production to understand disparities between clean energy winners and losing producers. This study focused on critical material-rich countries but vulnerable to clean energy technology, limited to clean energy winners, although they are rich in certain materials. For instance, the major producers of lithium are Chile, Australia, and Argentina, while consumers are the USA, Australia, and China16. Briefly, we illustrate the aggregate of global production for selected materials, examine the impact of FDI and discrepancy between geographical and company perspectives, estimate clean energy vulnerability, and propose a clean energy vulnerability mitigation framework.

Our findings indicate that many countries rich in critical materials essential for energy transition face reasonable vulnerabilities in clean energy technology, as their critical materials are predominantly controlled by FDI from countries leading in clean energy technology. A shift from FDI-driven material extraction toward clean energy development could substantially mitigate the clean energy vulnerabilities, enhance energy independence in critical material-rich but energy-vulnerable countries, promote global energy transition equity, and strengthen clean energy infrastructure through targeted partnerships.

Results

Critical energy transition material production

In our preliminary analysis, we mapped the hierarchical distribution of critical energy transition material production from 2016 to 2021. We have focused on nickel, manganese, cobalt, platinum, and bauxite (primary ore of aluminum) materials, primarily extracted from economically vulnerable and clean energy-poor countries. Supplementary Figs. 1–5 and Supplementary Tables 1–5 provide detailed descriptions on how high- and upper-middle income countries controlled the reasonable share of critical material from low- and lower-middle income economies. The findings indicate substantial production control by overseas companies based on high-income and clean energy-rich economies, which are linked to the affiliations of the mines’ shareholders and material consumers. This mapping captures the material flows from producers (mines) to consumers (company shareholders), highlighting disparities in FDI-driven production.

From 2016 to 2021, reasonable FDI controlled 16 manganese mines, 26 nickel mines, 22 cobalt mines, 24 platinum mines, and 13 bauxite mines in clean energy-vulnerable countries, leading to varied production levels. For nickel, the Taganito mine in the Philippines produced 25.17%, Sulawesi in Indonesia 16.19%, and Goro in New Caledonia 5.69% of the total mapped production. Key cobalt sources included the Kamoto (9.2%) and Tenke Fungurume (12.95%) mines in the DRC, both controlled by Switzerland’s Glencore, and the Chambishi mine in Zambia, producing 9.48% under China Nonferrous Mining. South Africa, producing 85.05% of global platinum, guaranteed a substantial production share controlled by Anglo American (UK). For manganese, mines such as Kalahari and Nchwaning (17.23%) and Gloria and Tshipi Borwa (11.29%) in South Africa. Gabon’s open pit mine (12.58%) dominated production, with shareholders including Anglo American Platinum (UK), Renova Group (Russia), and Comilog and Jupiter (South Africa). Bauxite production was largely concentrated in Guinea, with the Sangaredi Kamsar mine (39.82% of Guinea’s bauxite) operated by Rio Tinto, Alcoa, and Dadco Group in partnership with the Guinean government. China’s Hongqiao Group fully controlled the Boke mine, contributing 9.19% of production. These results underscore the heavy influence of foreign ownership on material production in clean energy-vulnerable countries, revealing a structural imbalance where high-income economies control material sources crucial for clean energy transitions.

Impact of FDI on the critical material production

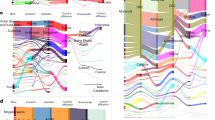

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the distribution of critical energy transition material production controlled by FDI in countries highly vulnerable to clean energy shortfalls, concentrated in companies from clean energy winners. These results indicate that critical materials are highly concentrated in companies (material consumers), while the home countries control less production. The trade flows between material producers and consumers are presented in Supplementary Fig. 6, and a detailed description is provided in Supplementary Note 1. FDI intensifies the discrepancy between government-owned enterprises in material-producing countries and foreign shareholders, with material-consuming countries dominating critical energy transition materials production. This implies that FDI-focused material extraction enables material consumers to secure critical materials and advance clean energy development more efficiently than material-producing countries. On the other hand, material producers are subjected to apparent economic growth in the long term via intensive FDI, however, most countries are economically vulnerable. From 2016 to 2021, FDI controlled over half of global production in key materials: 55.56% of bauxite, 52.47% of manganese, 59.28% of cobalt, 59.3% of nickel, and 56.59% of platinum. Regionally, cobalt production was concentrated in the DRC (49.95%), Zambia (14.32%), and Brazil (8.57%). Nickel production was highest in Indonesia (18.61%), New Caledonia (26.19%), and the Philippines (19.67%). Bauxite production was led by Guinea (45.32%), Tanzania (21.08%), and Jamaica (10.99%). Manganese by South Africa (40.72%), Morocco (31.91%), and Gabon (11.86%), while platinum is predominantly from South Africa (85.03%) and Zimbabwe (8.21%). The results further show that high- and upper-middle-income economies dominate FDI in these materials: 29.48% and 6.46% of nickel, 34.41% and 24.51% of cobalt, and 56.08% of platinum are controlled by FDI from high-income countries alone. For manganese and bauxite, high- and upper-middle-income countries control 14.96% and 15.39%, and 31.09% and 6.86%, respectively. High-income economies import a substantial portion of these materials from vulnerable countries: For example, Switzerland controls 38.98% of cobalt from the DRC, China controls 55.59% of cobalt from Zambia, the USA controls 79.2% of Jamaican bauxite, and the UK controls 60.62% of platinum from South Africa. Brazil and China hold notable shares of nickel from Indonesia and New Caledonia, while France controls 20.48% of New Caledonia’s nickel. These findings underscore a stark disparity: Although critical material-rich countries received reasonable FDI, as income revenue to boost their economic growth, some countries are clean energy-vulnerable compared to importing countries. A higher dependence on FDI as economic returns is subject to long-term deficiency of clean energy capacities in clean energy losers. This suggests that material-producing countries bear a disproportionate burden in supplying the global energy transition while receiving FDI as economic returns at the cost of clean energy vulnerability.

Materials include bauxite, manganese, cobalt, nickel, and platinum. The length of each flow represents the percentage of material production controlled by FDI. Gray segments denote the percentage of production retained by host countries, while colored segments indicate production controlled by overseas consumers. Country codes used are as follows: GIN (Guinea), JAM (Jamaica), ZAF (South Africa), GAB (Gabon), BRA (Brazil), MAR (Morocco), ZWE (Zimbabwe), COD (Democratic Republic of the Congo), ZMB (Zambia), PNG (Papua New Guinea), PHL (Philippines), IDN (Indonesia), NCL (New Caledonia), CHN (China), JPN (Japan), BRA (Brazil), UK (United Kingdom), DEU (Germany), NLD (Netherlands), RUS (Russia), AUS (Australia), HK (Hong Kong), and CAN (Canada).

Quantifying clean energy vulnerabilities

Drawing on past research sources16,40, we calculated the CVI, which incorporates key factors. These factors are geopolitical risk, disparities in critical energy transition material production, processing, and manufacturing bases for clean energy, as well as FDI-driven critical material production. Figure 3 portrays the CVI of selected countries for cobalt, nickel, manganese, platinum, and bauxite materials. These results indicate that countries that are heavily reliant on critical material imports face greater vulnerability than those with substantial domestic production. Using CVI, based on the quantity of material production, FDI influence, and current clean energy capacity, we identified reasonable vulnerability to clean energy capacity among leading material producers. These include cobalt producers (DRC, Zambia, and Papua New Guinea); nickel producers (Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, New Caledonia, Philippines, South Africa, and Zambia); manganese producers (South Africa, Morocco, Brazil, India, and Gabon); platinum producers (South Africa and Zimbabwe); and bauxite producers (Guinea, Kazakhstan, and Jamaica). Current FDI structures intensify the disparity between critical material producers and consumers, especially through bilateral trade relations, as confirmed by our import, export, and earnings analysis in the context of previous studies41,42. To measure the beneficial equity in terms of energy transition progress among material producers and consumers, we calculated the beneficial inequality indicator encompasses three sub-indicators. These sub-indicators are the inequality distribution of critical materials trade, clean energy production, and the shares of electric vehicles produced and sold internationally, termed “post-material trade benefit”. Results show that most critical material producers are vulnerable to post-trade benefits compared to material importers. For instance, Gabon is more vulnerable from post-trade benefits for manganese, DRC is more vulnerable for cobalt, and Zimbabwe is more vulnerable of its platinum production. Adjusting FDI-related trade flows/ subtracting material production controlled by FDI failed to achieve a post-balanced material trade benefit between material producers and consumers (more details are available in Supplementary Note 4 and 5, related Supplementary Figs. 10–12, and Tables 8 and 9). Generally, findings reveal that countries that are heavily reliant on critical material imports face greater vulnerability than those with substantial domestic production. FDI-related material production stimulates clean energy vulnerability in critical material producers compared to material consumers.

The illustration of other sub-indicators is presented in the Supplementary Information.

Quantifying the impact of redirecting FDI towards clean energy development

Table 1 illustrates the critical material controlled by FDI, disparity in clean energy capacity between FDI based on extractive purpose and clean energy developmental FDI in most clean energy-vulnerable countries. For instance, FDI in cobalt production could potentially boost the DRC’s clean energy capacity from 0.108 gigawatt (GW) to 1922.4 GW, and Zambia’s from 0.387 to 476 GW. Similarly, nickel-focused FDI could enable Indonesia to elevate its clean energy capacity from 1.87 to 88 GW and Papua New Guinea from 0.01 to 103 GW. By converting critical materials controlled by FDI into perceptible clean energy gains, this new framework could provide a pathway for clean energy losers to advance their energy transitions. Figure 4 visualizes the aggregated extent of clean energy capacity achievable in vulnerable countries through shift from FDI-based extractive to clean energy developmental FDI. Although our findings suggest that material-producing countries should reasonably contribute to their own energy capacity, redirecting FDI toward clean energy deployment could effectively reduce current energy vulnerability issues. For example, 40% of cobalt imports to the UK, Switzerland, South Africa, and China from the DRC represent 3.91%, 15.56%, 2.64%, and 11.74% of the DRC’s potential clean energy capacity, respectively. In Zambia, 40% of China and UK cobalt imports correspond to 22.23% and 7.08%, respectively, of the estimated clean energy capacity. The 40% of Chinese imports of FDI-controlled nickel from Papua New Guinea equate to 34.07% of that country’s clean energy capacity potential. 40% of South Africa’s FDI-driven nickel exports (198kt) could correspond to 458 GW in clean energy, with exports to the UK and Russia could cover 21.3% and 10.64%, respectively, of South Africa’s estimated clean energy capacity. In Zimbabwe, 40% of platinum exports to the UK comprise 14% of the country’s potential clean energy capacity. Considering the estimated clean energy vulnerability, we have noted that an effective strategy for mitigating clean energy vulnerability in countries with critical energy transition materials is based on shifting from FDI-based material extraction towards clean energy development. Specifically, this strategy entails a framework where the materials extracted through FDI are exchanged for equivalent clean energy capacity, thereby aligning material production, processing, and manufacturing bases with clean energy objectives. This exchange framework allows countries that are currently disadvantaged in clean energy capacity to benefit from the export of their critical materials, ultimately reinforcing their clean energy infrastructure. Our aggregated findings indicate that by restructuring FDI, countries rich in critical materials (cobalt, nickel, manganese, platinum, and bauxite) can increase their clean energy capacity reasonably, surpassing the impacts of existing FDI frameworks. These findings suggest that restructured FDI in critical material exports could transform foreign investments from mere extraction into a tool for boosting clean energy capacity in material-rich but clean energy-vulnerable countries. This proposed FDI framework would enhance energy independence, promote equitable clean energy access, and stabilize global supply chains via building clean energy infrastructure directly in material-producing countries such as the DRC, Zambia, and Indonesia. In turn, it fosters international partnerships that support sustainable development and contribute to global emission reductions, offering a pathway for a fairer and more resilient global energy transition.

The vertical axis indicates the percentage of importers’ contribution, and colors delineate critical materials importers. Dark gray color indicates the remaining shares that critical material producers could add to their clean energy system. Country codes used are as follows: GIN (Guinea), JAM (Jamaica), ZAF (South Africa), GAB (Gabon), BRA (Brazil), MAR (Morocco), ZWE (Zimbabwe), COD (Democratic Republic of the Congo), ZMB (Zambia), PNG (Papua New Guinea), PHL (Philippines), IDN (Indonesia), NCL (New Caledonia), CHN (China), JPN (Japan), BRA (Brazil), UK (United Kingdom), DEU (Germany), NLD (Netherlands), RUS (Russia), AUS (Australia), HK (Hong Kong), and CAN (Canada).

Discussion

Our analysis reveals that existing FDI related to mining projects termed as “FDI-based material extractive tool” has increased the production of nickel, manganese, cobalt, platinum, and bauxite extracted from clean energy-vulnerable countries. In the context of globalization and bilateral cooperation, upper-middle- and high-income economies have intensively invested in the mining projects of these critical materials, often through full or partial ownership of mines alongside local companies, whether privately or government-owned. Between 2016 and 2021, 55.56% of bauxite, 52.47% of manganese, 59.28% of cobalt, 59.3% of nickel, and 56.59% of platinum from major mines were controlled by foreign companies through FDI-related projects, while the rest shares were controlled by domestic companies. This foreign dominance in critical material extraction has resulted in reasonable disparities in production control and post-material trade benefits (clean energy production and electric vehicles), with foreign investment driving mining operations and leaving host countries with minimal ownership.

Merging critical energy transition material production and classification of global countries in terms of income variabilities, we found diversification results. The high- and upper-middle-income economies controlled a reasonable share of production from low- and lower-middle-income economies that are highly vulnerable in clean energy. Typically, 35.94% of nickel, 58.92% of cobalt, and 56.08% of platinum extracted from clean energy-vulnerable countries are controlled by FDI from high-income countries, whose reasonable contribution in global clean energy capacity, see Supplementary Fig. 6 for trade flows and associated text. The notable example is the DRC, a low-income economy whose 0.108 GW of 5 years accumulated energy capacity29, a top global producer of cobalt, 70.4% of production is FDI controlled, and 38.98% of imports by Switzerland43. The increasing trend of FDI related to material control has been considered as an economic return for some countries, mostly low- and lower-middle-income economies3,21. However, while critical materials contribute to economic growth in certain countries, such as cobalt (DRC)44 and Nickel (Indonesia)45, long-term responses to economic growth are disrupted due to geopolitical tensions in some countries46.

From 2016 to 2021, FDI highly stimulated the critical material production in top global producers, which are clean energy losers: DRC and Zambia dominated cobalt production, Gabon and South Africa dominated in manganese, Indonesia and New Caledonia dominated in nickel, Guinea and South Africa dominated in Bauxite, and Zimbabwe and South Africa dominated in platinum. On the consumers’ side, China and Switzerland control 55.59% and 38.9% of cobalt from Zambia and the DRC, respectively. The USA controls 79.2% of Jamaican bauxite, and the UK controls 60.62% of platinum from South Africa. Brazil and China hold notable shares of nickel from Indonesia and New Caledonia, while France controls 20.48% of New Caledonia’s nickel. These findings indicate that clean energy winners import substantial amounts of critical materials via FDI compared to what remains in local hands, contributing to post-trade inequalities, particularly in clean energy production and electric vehicle development. Past studies confirmed the role of FDI as a material extractive tool to increase production while reducing supply risks, environmental issues, and related consequences, and promote the clean energy sector of importing countries6,16,17,18. Adjusting global material trade based on subtracting FDI-related trade flows, critical material supply disruptions are reduced in some countries through reducing the import materials16. Our verified results argue that FDI stimulates an imbalance between material producers and consumers. While material consumers face high levels of import dependence, material producers become vulnerable to clean energy capacity, particularly in terms of their slow transition to clean energy technologies, see Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Tables 8 and 9. The limited clean energy capacity and electric vehicles manufacturing in clean energy losers highlight the mismatches between critical material extraction and the clean energy transition, despite global efforts to mitigate climate change24,47,48.

These findings demonstrate that the FDI-based material extractive tool not only aggravates inequality in material control but also in technological applications, such as clean energy development and electric vehicle-related battery production between material producers and consumers. This is supported by discrepancy between exporting and importing countries, where materials produced from exporting countries are both processed and refined in importing countries. Again, cathode material production, battery and cells, and electric vehicles production are concentrated in importing countries, such as China, European countries, the USA, Japan, and others18. Our verified evidence showed that the current FDI framework intensifies clean energy vulnerability and global energy transition inequality, such as domestic clean energy production and electric vehicles adoption, for material-producing countries. Those analyses were conducted using the import-export dynamics and earnings distribution41,42, in the context of global energy transition inequality.

Based on our proposed CVI, we found that some global critical energy transition material producers are highly clean energy vulnerable. For instance, top cobalt producers (DRC, Zambia, and Zimbabwe); nickel producers (Indonesia and New Caledonia); manganese producers (South Africa and Gabon); platinum producers (South Africa and Zimbabwe); and bauxite producers (Guinea, Kazakhstan, and Jamaica), their material importers are all clean energy winners. DRC and South Africa were also observed to be vulnerable for lithium-ion battery chemistries18, implying severe vulnerability of their critical materials in terms of clean energy technology. This vulnerability is influenced by governance indicators, with some countries experiencing long-term governance instability that affects mining policies and bilateral trade flows, such as the DRC49. Our findings align with real estimates, demonstrating how most critical material producers are highly vulnerable to the clean energy transition29,50,51. We found that shifting from FDI-based material extraction to clean energy developmental FDI can offer a more efficient and equitable promotion of clean energy transitions in clean energy losers that are low-/lower-middle-income economies endowed with valuable critical materials. This highly responds to the United Nations Secretary-General’s panel proposition on critical energy transition materials, which emphasizes that countries and communities rich in these resources should benefit most35. Our aggregated results from Table 1 and Fig. 4 illustrate how exchanging critical material exported to high economies with equivalent clean energy capacity to be installed in material producers could reasonably accelerate the clean energy transition in clean energy losers. For example, under the existing FDI context, the DRC produced 408 kt of cobalt, equivalent to 5677 GW of energy storage capacity over 6 years (2016–2021). Shifting to clean energy developmental FDI, 40% of cobalt imports to the UK, Switzerland, South Africa, and China from the DRC represent 3.91%, 15.56%, 2.64%, and 11.74% of the DRC’s potential clean energy capacity, respectively. The 40% of Chinese imports of FDI-controlled nickel from Papua New Guinea equate to 34.07% of that country’s clean energy capacity potential of Papua New Guinea. In Zimbabwe, 40% of platinum exports to the UK comprise 14% of the country’s potential clean energy capacity.

Our results indicate that redirecting critical mineral exports toward domestic clean energy projects in critical material-rich but clean energy-poor countries could reasonably enhance their clean energy capacity, reducing reliance on foreign economies and accelerating local energy transitions. The estimates suggests that if countries, such as the DRC, Zimbabwe, and Papua New Guinea reallocated about 40% of their critical material exports (e.g., cobalt, platinum, nickel) domestically, they could realize substantial portions of their clean energy potential, ranging from 3.91% to 34% of total capacity. Implementing FDI transition for both clean energy policy and environmental policy could reasonably reduce clean energy vulnerability and ensure global energy transition equity, which are the prior responses to the current climate change issues. This response to environmental issues coincides with a past study that showed that critical materials (copper, aluminum, nickel, cobalt, and manganese) imports increase as clean energy technology increases, highlighting the potential response to climate changes52. On the side of importing countries, FDI reduces supply risks and facilitates access to critical materials for the clean energy transition, which is observed to long termly exacerbate the material imports53. Through extensive verifications of data and analysis in this study, our results are fundamental and the foundation of effective equity in the clean energy transition globally. Our findings confirmed that the proposed framework for reducing clean energy vulnerability based on shifting from FDI-related to critical material extractive tools to clean energy development could be considered as the real deal to foster energy transition. Furthermore, our results can balance material flows between exporting and importing countries, focusing on interconnected trades between critical material producers and consumers, illustrated from past studies12,24,54,55.

Policymakers ought to consider effective policies that boost the clean energy system of critical material producers, which are identified as clean energy losers. Some of these policies are follows: Firstly, encouraging FDI in mining projects that prioritize local clean energy development and economic growth over critical material exports. This shift could reduce clean energy vulnerability and reduce environmental costs by fostering clean energy infrastructure and economic gains in material-rich countries rather than exporting critical materials. Secondly, governments in critical materials-rich countries might implement policies to retain a percentage of critical materials for domestic clean energy projects. Such policies would maximize the local benefits of natural resources, contributing to clean energy sector development while reducing dependency on foreign energy imports. These policies are aligning with sustainable development goals that focus on affordable and clean energy (SDG-7) and climate action (SDG-13)56. They promote the equity shares of critical energy transition materials and sustainability between material producers and consumers, mainly benefiting the host of materials but vulnerable countries to a clean energy shortage35. Thirdly, new critical material trade agreements could be established to balance critical material exports with clean energy development goals, mandating that a share of materials traded must be invested in clean energy projects in the exporting country. Fourth, international organizations could support policies encouraging technology transfer and infrastructure development for clean energy in critical materials-exporting countries. These policy measures could reshape global supply chains, ensuring that critical materials-rich countries benefit directly from their resources by realizing sustainable clean energy technology. To effectively comprehend and implement these policies, comprehensive feasibility and cost analysis studies are essential, alongside a strong global commitment to facilitating the proposed framework in critical material-exporting countries. However, while this study offers valuable insights, it also presents certain limitations and uncertainties that should be addressed in future research to further refine and enhance the proposed framework.

Methods

Material traceability and quantifying the impact of FDI on material production

Here, we present a summary of the main methods and data sources used to obtain the primary results, while details and explanations are provided in the supplementary materials, as well as in published materials. Without losing the validity of energy transition material critically3, we focused on five selected critical materials: Manganese, bauxite (primary ore of aluminum), cobalt, nickel, and platinum. These critical materials were selected due to their crucial role in clean energy technology38,39, the intensive FDI36, reasonable contribution to global critical material production and trade27,57, mostly the home countries are vulnerable to the clean energy transition22,23,24. One the case of data availability, this study aggregated the material production, FDI, ownership hierarchy, and old/new mines, companies’ information, and related affiliation obtained from the United States Geological Survey37,58, and published materials16,25. The production data was measured in a thousand metric tons for bauxite, platinum, and manganese, or metric tons for cobalt and nickel, which were converted to kilotons, except for platinum production, which was counted in metric tons. Clean energy capacity was measured in gigawatts, and electric vehicle shares were sourced from Our World in Data25. The aggregates cover 6 years, from 2016 (FDI intensification)36 to 2021 (last data update37). The overseas trade data for each material was obtained from the United Nations database37 and the World Integrated Trade Solution57,59. The study covers 16 manganese mines, 26 nickel mines, 22 cobalt mines, 24 platinum mines, and 13 bauxite mines that are operated via FDI from various global countries. Using the above information, we first applied the system of boundaries that has been employed in previous studies16,18, to map the production flow of energy transition materials from material producers (mines, location, and operators, and affiliation) to material consumers (companies’ shareholders and their affiliation), see Supplementary Figs. 1–5, Tables S1–S5, and related texts. We then quantified the impact of FDI on critical material extracted from clean energy losers, see Supplementary Fig. 6 and related Supplementary Note 1.

Estimating clean energy vulnerability index

CVI is a geometric mean of two main sub-indicators: the first sub-indicator is the material and clean energy capacity dependence, covering critical material production and clean energy capacity dependence. The second sub-indicator is the FDI and mineral production dependence (FMD), reflecting dependence on mineral production in regions affected by geopolitical risks, such as governance challenges and political instability. Both sub-indicators and the CVI were computed following established index calculation frameworks16,40,60 and normalized to a range between 0 and 1 in Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively.

\({{CVI\; norm}}_{i}\) is normalized on a 0 to 1 scale, with higher scores indicating a greater vulnerability. The raw \({{CVI}}_{i}^{{raw}}\) values were normalized based on the raw estimates (original CVI), as well as the detected minimum and maximum scores across all countries for each material. The \({{MCD}}_{i}\) is based on material production and clean energy capacity. This sub-indicator encompasses distinct ranks of material production, material processing, capacity for manufacturing material for clean energy, and installed clean energy capacity. It is computed in Eq. (3) as the symmetrical means of critical material production and clean energy capacity rates for material producers.

\({{MR}}_{p}\) is the material production rate, and \({{CR}}_{i}\) is the clean energy capacity rate for material producers; their mathematical expressions are available in Supplementary Methods.

The second sub-indicator is \({{FMD}}_{i}\) that measures the resilience of their clean energy sector and anticipates potential disruptions. FMD captures the geographical concentration of critical materials and the influence of Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), specifically political stability and governance effectiveness. This insight allows for proactive strategies that can mitigate risks associated with the clean energy transition, such as diversifying supply chains and geopolitical risks. Based on the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index60 calculation, the share of material production controlled by FDI is squared for simulating the material production concentration. Thus, the indicator can be computed as follows:

For \({{MP}}_{{FDI}}\) is the material production is controlled by FDI, \({TMP}\) is the sum of material produced in all selected countries, and WGI represents the aggregate of political stability and governance effectiveness estimates in each country. Detailed mathematical parameters, formulations, and explanations are provided in the Supplementary methods, and visualizations of the sub-indicators are available in Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8 and related Supplementary Note 2.

Quantifying the impact of redirecting FDI towards clean energy development

We propose a framework for shifting FDI from critical material extraction toward clean energy development, which could substantially reduce clean energy vulnerability in critical material-rich countries. Here, we relied on previous studies61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68 to develop an estimator that converts material production from FDI-influenced extractive activities into potential clean energy capacity. Using known parameters, such as capacity factors, conversion factors, operational factors for each clean energy technology, and the critical materials consumed, this estimator, expressed in Eq. (5), converts the volume of critical material production into equivalent clean energy capacity.

For \(0 \, < \, \alpha \, \le \, 1\) is a parameter indicating the score for material production, material processing, and manufacturing capacity for material producers, detailed in Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. S9. \({{GW}}_{{il}}\) is the clean energy capacity, l critical material type (nickel, cobalt, manganese, platinum, and bauxite). \({X}_{l}\) is the quantity of critical material extracted through FDI, \({\beta }_{l}\) is the conversion parameter, which is estimated differently for each critical material, T is the time of operation (assumed to be annually). See additional details in Supplementary Methods.

Limitations and uncertainties

This study encountered certain limitations, primarily due to the exclusion of key countries that are reasonable producers of critical materials and highly vulnerable to clean energy transitions. This exclusion was largely a result of data unavailability, particularly concerning bauxite materials within the selected databases. The proposed estimators may be subject to statistical biases and computational inaccuracies arising from over-/under-estimation, potentially introducing uncertainties and limitations. These challenges are particularly pronounced in cases where discrepancies exist in material production, processing, and the manufacturing of clean energy components (e.g., cathode materials and batteries) between producing and consuming countries. To minimize uncertainty in CVI calculations, we excluded the FDI percentage and instead focused on the volume of extracted critical materials, with scarce resource indicators. This approach prioritizes countries heavily impacted by FDI and producing higher quantities of critical material, but more vulnerable in clean energy capacity than countries producing reasonable quantities with less FDI impact. Additionally, the proposed converter from material production to equivalent clean energy capacity could be refined by incorporating factors that better reflect the realities of material processing and manufacturing capacities, including associated costs and mechanisms. We acknowledge that the CVI and the proposed converter represent point estimates that can be further refined by incorporating an economic vulnerability index, feasibility assessments, and cost analysis. This integration would enhance their accuracy and alignment with real-world conditions, particularly during policy implementation. Further studies may consider the Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient to assess the distributional benefits of critical materials, accounting for discrepancies in production, processing costs, value addition, and variations in clean energy technologies and chemistries across producer and consumer countries.

Data availability

Data related to mines, shareholders, and material production were mined from the United States Geological Survey reports37. Data related to international trade flows were extracted from the United Nations database and the World Integrated Trade Solution57,59. Clean energy capacity and electric vehicles data were sourced from Our World In Data25. Other data were sourced from published materials16,49, and summarized in supplementary materials.

References

Carley, S. & Konisky, D. M. The justice and equity implications of the clean energy transition. Nat. Energy 5, 569–577 (2020).

IEA. World Energy Outlook 2021. IEA https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2021 (2021).

IEA. The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions https://doi.org/10.1787/f262b91c-en (2021).

Applegate, J. D. 2022 final list of critical minerals. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/02/24/2022-04027/2022-final-list-of-critical-minerals.

Tian, X. et al. Features of critical resource trade networks of lithium-ion batteries. Resour. Policy 73, 102177 (2021).

Rui, X., Geng, Y., Sun, X., Hao, H. & Xiao, S. Dynamic material flow analysis of natural graphite in China for 2001-2018. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 173, 105732 (2021).

Xun, D. et al. Mapping global fuel cell vehicle industry chain and assessing potential supply risks. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 46, 15097–15109 (2021).

Geng, J. et al. Static material flow analysis of neodymium in China. J. Ind. Ecol. 25, 114–124 (2021).

Sekine, N., Daigo, I. & Goto, Y. Dynamic substance flow analysis of neodymium and dysprosium associated with neodymium magnets in Japan. J. Ind. Ecol. 21, 356–367 (2017).

Luo, X., Pan, L. & Yang, J. Mineral resource constraints for China’s Clean energy development under carbon peaking and carbon neutrality targets: quantitative evaluation and scenario analysis. Energies 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/en15197029 (2022).

Fabra, N. & Reguant, M. The energy transition: a balancing act. Resour. Energy Econ. 76, 101408 (2024).

IRENA. Global Energy Transformation: A Roadmap to 2050. International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA, 2019).

Vakulchuk, R. & Overland, I. Central Asia is a missing link in analyses of critical materials for the global clean energy transition. One Earth 4, 1678–1692 (2021).

Bazilian, M. D. The mineral foundation of the energy transition. Extr. Ind. Soc. 5, 93–97 (2018).

Trost, J. N. & Dunn, J. B. Assessing the feasibility of the Inflation Reduction Act’s EV critical mineral targets. Nat. Sustain. 6, 639 (2023).

Sun, X. et al. Reducing supply risk of critical materials for clean energy via foreign direct investment. Nat. Sustain. 7, 672–681 (2024).

Cusato, E. Transnational law and the politics of conflict minerals regulation: construing the extractive industry as a ‘partner’ for peace. Transnatl. Leg. Theory 12, 269–293 (2021).

Cheng, A. L., Fuchs, E. R. H., Karplus, V. J. & Michalek, J. J. Electric vehicle battery chemistry affects supply chain disruption vulnerabilities. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46418-1 (2024).

Velenturf, A. P. M., Purnell, P. & Jensen, P. D. Reducing material criticality through circular business models: challenges in renewable energy. One Earth 4, 350–352 (2021).

Vespignani, J. & Smyth, R. Artificial intelligence investments reduce risks to critical mineral supply. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–11 (2024).

The World Bank. World Bank country classifications by income level for 2024-2025. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/world-bank-country-classifications-by-income-level-for-2024-2025 (2024).

IRENA. World Energy Transitions Outlook: 1.5 Degrees Pathway. International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA, 2021).

Deirdre Cogan, R. G. Where Do We Stand on COP26 Climate Promises? A Progress Report. https://www.wri.org/insights/cop26-climate-pledges-tracking-progress (2022).

Bocca, R., Ashraf, M. & Jamison, S. Fostering Effective Energy Transition 2021 Edition. 1–52 (World Economic Forum, 2021).

OWID. Our World In Data (Accessed August 2022). https://ourworldindata.org/renewable-energy (2024).

Arias, A., Feijoo, G. & Moreira, M. T. Advancing the European energy transition based on environmental, economic and social justice. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 43, 77–93 (2023).

IRENA. Geopolitics of the energy transition. https://www.irena.org/Digital-Report (2024).

Murshed, M. Pathways to clean cooking fuel transition in low and middle income Sub-Saharan African countries: the relevance of improving energy use efficiency. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 30, 396–412 (2022).

IEA. Africa Energy Outlook 2022. Africa Energy Outlook 2022 https://doi.org/10.1787/2abd9ce2-en (2022).

Wang, J.-A. & Kuznetsov, V. Critical Minerals for the Sustainable Energy Transition: A Guidebook to Support Intergenerational Action (UNECE: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 2024).

The global fight for critical minerals is costly and damaging. Nature 619, 436 (2023).

Owen, J. R. et al. Energy transition minerals and their intersection with land-connected peoples. Nat. Sustain. 6, 203–211 (2023).

Lèbre, É et al. The social and environmental complexities of extracting energy transition metals. Nat. Commun. 11, 4823 (2020).

Lema, R., Bhamidipati, P. L., Gregersen, C., Hansen, U. E. & Kirchherr, J. China’s investments in renewable energy in Africa: creating co-benefits or just cashing-in?. World Dev. 141, 105365 (2021).

UN. The UN Secretary-General’s Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals, Copenhagen (United Nations, 2024).

IEA. Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024 https://www.iea.org/reports/global-critical-minerals-outlook-2024/market-review (2024).

USGS. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center/Data (2023).

Smith, S. A. & Watts, R. Critical materials assessment program. Sol. Cells 11, 41–49 (1984).

Carrara, S. et al. Supply Chain Analysis and Material Demand Forecast In Strategic Technologies And Sectors in the EU – A Foresight Study. (Publications Office of the European Union, 2023).

Nassar, N. T. et al. Evaluating the mineral commodity supply risk of the U.S. Manufacturing sector. Sci. Adv. 6, 8 (2020).

Adão, R., Carrillo, P., Costinot, A., Donaldson, D. & Pomeranz, D. Imports, Exports, and Earnings Inequality: Measures of Exposure and Estimates of Incidence. Q. J. Econ. 137, 1553–1614 (2022).

Ciani, A. Income Inequality and the Quality of Imports. Review of World Economics Vol. 157 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2021).

Henry, A. Transmission channels of the resource curse in Africa: a time perspective. Econ. Model. 82, 13–20 (2019).

Namahoro, J. P., Wu, Q. & Hui, S. Asymmetric linkage between copper-cobalt productions and economic growth: evidence from Republic Democratic of Congo. Resour. Policy 83, 103630 (2023).

Warburton, E. Nationalist enclaves: Industrialising the critical mineral boom in Indonesia. Extr. Ind. Soc. 20, 101564 (2024).

Gulley, A. L. One hundred years of cobalt production in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Resour. Policy 79, 103007 (2022).

Layke, J. STATEMENT: 117 countries pledge to triple world’s renewable energy capacity and double energy efficiency by 2030. https://www.wri.org/news/statement-117-countries-pledge-triple-worlds-renewable-energy-capacity-and-double-energy (World Resource Institute, 2023).

IEA. World Energy Investment 2023 https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2023 (2023).

Iguma Wakenge, C., Bashwira Nyenyezi, M.-R., Bergh, S. I. & Cuvelier, J. From ‘conflict minerals’ to peace? Reviewing mining reforms, gender, and state performance in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Extr. Ind. Soc. 8, 100894 (2021).

IEA. Net Zero by 2050. A roadmap for the global energy sector. https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050 (2021).

Bencherif, Y. et al. https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2021-05/StakeholdersThematicEConsultation_UNHighLevelDialogueonEnergy_SummaryReport.pdf.

Fikru, M. G., Kilinc-Ata, N. & Belaïd, F. Climate policy stringency and trade in energy transition minerals: an analysis of response patterns. Resour. Policy 96, 105236 (2024).

Kilinc-Ata, N., Alshami, M. & Munir, K. How do strategic mineral resources affect clean energy transition? Cross-sectional autoregressive distributed lag (CS-ARDL) approach. Miner. Econ. 36, 643–654 (2023).

IRENA, KfW and GIZ. The Renewable Energy Transition in Africa (International Renewable Energy Agency, the German Development Bank and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, Abu Dhabi, Frankfurt and Bonn, 2021).

GWEC. Africa Wind Energy Handbook https://gwec.net/africa-wind-energy-handbook/ (2022).

UN. Global Sustainable Development Report (GSDR) 2023(Accessed December 2022) https://sdgs.un.org/gsdr/gsdr2023 (2022).

WITS. World Integrated Trading Solution. https://wits.worldbank.org/ (2023).

Jasinski Stephen, M. Mineral Commodity Summaries 2022 (U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), 2022).

Herfindahl, H. Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (US Department of Justice, 2018).

Herfindahl, H. Herfindahl-Hirschman Index. https://www.justice.gov/atr/herfindahl-hirschman-index (2023).

Smil, V. Energy Transitions: Global and National Perspectives https://www.nhbs.com/energy-transitions-book (Praeger, 2017).

Larcher, D. & Tarascon, J.-M. Towards greener and more sustainable batteries for electrical energy storage. Nat. Chem. 7, 19–29 (2015).

Thackeray, M. M., Wolverton, C. & Isaacs, E. D. Electrical energy storage for transportation—approaching the limits of, and going beyond, lithium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 7854–7863 (2012).

Tarascon, J.-M. & Armand, M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 414, 359–367 (2001).

Li, H. et al. Manganese-based materials for rechargeable batteries beyond lithium-ion. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2100867 (2021).

He, C., Desai, S., Brown, G. & Bollepalli, S. PEM fuel cell catalysts: cost, performance, and durability. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 14, 3 (2005).

de Frank Bruijn, A. & Janssen, G. J. M. PEM fuel cell materials: costs, performance and durability. In Fuel Cells (ed Kreuer, K. D.) (Springer, 2013).

Andre, D. et al. Future generations of cathode materials: an automotive industry perspective. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 6709–6732 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (grant number: 23&ZD107).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P.N. contributed to writing and revising the manuscript, data analysis, and methodology; W.Q. collaborated to revise the manuscript, supervision, and funding; D.W. contributed to editing the manuscript and data acquisition; and Z.N. collaborated to editing the manuscript, data acquisition, and analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Nurcan Kilinc-Ata and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Vaibhav Chaturvedi and Martina Grecequet. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Namahoro, J.P., Qiaosheng, W., Wang, D. et al. Foreign direct investment can enhance the development of clean energy in countries with critical materials. Commun Earth Environ 6, 348 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02319-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02319-9

This article is cited by

-

Foreign direct investment in mining projects reduces the global supply risk of critical materials

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

The role of mineral raw material imports in driving the energy transition

Mineral Economics (2025)