Abstract

Coastal cities face increasing compound flood risks from human mobility patterns under climate change. In this study, we integrated dynamic population distribution models with numerical hydrodynamic modelling to examine mobility effects on flood risk in Hong Kong’s Kowloon area. We simulated flooding across 75 scenarios with matching rainfall and storm surge return periods (50, 100, 200 years) under current conditions and climate projections for 2060 and 2100 under intermediate and very high emission pathways. We found human mobility causes notable temporal shifts in risk distribution, with commercial areas experiencing higher daytime risk while residential areas face increased nighttime risk. Flood risk decreases with distance from coastlines, showing distinct variations between weekdays and weekends. The Night-Day Risk Ratio reveals weekday differentials ranging from 18.7% to 20.6% with minimal weekend variations, intensifying under future climate projections. These insights inform urban planning and flood management in coastal cities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global environmental risk patterns are undergoing profound changes, primarily driven by climate change and rapid urbanization. This transformation is particularly evident in coastal cities, as these areas are at the forefront of these challenges. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects that under a high-emission scenario (RCP8.5), global mean sea levels could rise by 0.43-0.84 meters by 21001. Meanwhile, the United Nations (UN) predicts that 68% of the world population will reside in urban areas by 2050, up from 55% in 2018, with most of this growth concentrated in coastal regions2. As sea levels continue to rise and coastal populations steadily grow, these areas face an increasingly complex challenge in the form of compound flooding. This phenomenon, where multiple flood drivers occur simultaneously or in close succession, has emerged as a critical issue3,4. Recent studies indicate that the probability of compound flooding events is increasing globally5,6. For instance, Emanuele Bevacqua et al. 7 found that under a high-emission scenario, compound flooding from storm surges and rainfall will increase by more than 25% globally by the end of this century7,8. Furthermore, the impact of compound flooding will be amplified by rising sea levels9,10, with ~1 in 50 people in 32 major coastal cities in the United States affected by flooding11.

Given these escalating flood risks in coastal urban areas, it is crucial to accurately assess and manage these risks through appropriate methodological frameworks. Traditionally, flood risk assessment has relied on the framework of Risk = Exposure × Vulnerability × Hazard12,13,14. This approach has played a crucial role in identifying high-risk areas and developing flood management strategies. However, it fails to account for the dynamic nature of exposure. While exposure typically depends on population distribution scenarios15, urban population distribution is not static, particularly in terms of its diurnal movement patterns. Population mobility within urban areas creates a fluid risk landscape that varies both spatially and temporally. Recent studies using various data sources have revealed substantial daily fluctuations in urban population distribution. For example, in Tokyo, the central district’s daytime population increases more than sixfold compared to nighttime16. Similarly, in New York City, Manhattan’s daytime population increases by nearly 60% due to commuters17. Residential areas may become more vulnerable at night when people return home. These temporal variations in population density, driven by human mobility, have profound implications for flood risk assessment. The concentration of people in different areas at different times of day considerably alters the exposure component of the risk equation, ultimately affecting risk assessment. Given these notable temporal variations in population distribution, researchers have increasingly sought more sophisticated methods to capture dynamic exposure patterns. In recent years, there has been growing recognition of the importance of incorporating population dynamics into disaster risk assessments. Most studies have utilized mobile phone signalling data to analyse the impact of human mobility on flood risk assessment, effectively capturing dynamic population distribution18,19. However, while mobile phone data provides new research perspectives for population dynamics analysis, its limitations in nighttime data collection make it difficult to achieve round-the-clock dynamic risk assessment. This is particularly problematic when evaluating nighttime population exposure, potentially leading to major biases in risk assessment results20,21.

To overcome these methodological limitations and address the growing challenges of climate change, a more integrated approach to population dynamics and flood risk assessment is needed. On the other hand, in the context of climate change, coastal cities face escalating risks, particularly from compound flooding caused by the combination of sea-level rise and extreme weather events22,23,24. Especially in densely populated coastal cities, there exists a complex spatiotemporal relationship between population mobility (driven by daily commuting and commercial activities) and flood risk25,26, which makes accurate understanding of dynamic population distribution increasingly critical. However, these interaction mechanisms remain insufficiently studied. To address this critical research gap and better understand these complex interactions, it is essential to develop high-resolution spatiotemporal population modelling methods based on multi-source data fusion. To this end, by integrating travel surveys, census data, land use data, and Baidu heat maps, we can construct more accurate round-the-clock dynamic population distribution models. This methodological innovation will overcome the limitations of single data sources while providing more reliable decision support for assessing compound flood risks under climate change. Furthermore, this approach will fill the theoretical gap in understanding the interaction mechanisms between population dynamics and compound flood risks in coastal cities. These improvements will ultimately provide important scientific basis for urban disaster prevention and mitigation planning in the context of climate change, with practical applications in emergency response, urban planning, and risk management.

In this study, we investigate the complex relationship between human mobility and compound flood risks under sea-level rise scenarios, using the Kowloon area of Hong Kong as a case study. By integrating dynamic population distribution models with coupled hydrodynamic modelling (LISFLOOD-SWMM), we simulate compound flooding events across various return periods and sea-level rise scenarios. Our research develops a comprehensive framework to analyse how population mobility patterns interact with flood risks across different temporal scales (weekday/weekend, day/night) and spatial dimensions. Through systematic assessment of land use patterns and dynamic population distribution, we aim to provide more nuanced insights into the spatiotemporal variations of flood risks in coastal urban areas. The findings from this study not only contribute to the theoretical understanding of human mobility-flood risk interactions but also offer practical guidance for adaptive urban planning and flood management strategies. This research aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and 13 (Climate Action)27, addressing the urgent need for climate-resilient urban development in coastal regions facing the dual challenges of sea-level rise and increasing urbanization.

Results

Dynamic flood risk assessment

To address the limitation in integrating human mobility in assessing compound flood risks under climate change, our study develops a comprehensive dynamic risk assessment framework that utilizes three key components: exposure, vulnerability, and hazard. We conducted the assessment across 75 scenarios combining different flood drivers (Supplementary Table 3), focusing on the Kowloon area of Hong Kong as our study site. This comprehensive framework enables us to quantify compound flood risk by integrating spatial and temporal dimensions across multiple scenarios. Beginning with exposure assessment, we analysed population distribution patterns to capture the dynamic nature of human mobility across different time periods. The exposure assessment results are visualized in Fig. 1, which shows distinct patterns between weekday nighttime (a), weekday daytime (b), weekend nighttime (c), and weekend daytime (d) population distributions. These maps demonstrate how population exposure varies markedly across different temporal periods, reflecting the dynamic nature of urban activities.

Vulnerability is assessed through multiple socioeconomic factors, as shown in Fig. 2a–h, including age distribution, education levels, income status, and other demographic characteristics that influence the susceptibility of a population to flood impacts. The comprehensive vulnerability index (Fig. 2i) helps identify particularly sensitive areas within the study area. Vulnerability is assessed through multiple socioeconomic factors, as shown in Fig. 2a–h, including age distribution, education levels, income status, and other demographic characteristics that influence the susceptibility of populations to flood impacts. Each factor contributes differently to the overall sensitivity of populations to flooding effects. The comprehensive vulnerability index (Fig. 2i), created through standardization of all variables, synthesizes these socioeconomic factors to reveal substantial spatial heterogeneity across the study area. From the perspective of distance from the coastline, coastal areas near the ocean exhibit medium vulnerability levels (0.5–0.7), while some coastal communities show lower vulnerability indices (0.3–0.5). In contrast, inland core urban districts display the highest vulnerability (0.8–1.0). This distribution pattern emphasizes the need to develop differentiated flood risk management strategies for different regions, highlighting the necessity of targeted approaches to flood risk management.

a–h are the proportions of different populations. a Age below 15. b Low education. c female. d High mortgage, with household with mortgage greater than HK $10,000. e Age above 65. f ethnic minorities. g Low-income family (income less than HK $10,000). h Low-income population (income below HK $10,000). i Vulnerability index.

Results of the compound flood hazard assessment revealed distinct spatial patterns across the study area (Fig. 3). The LISFLOOD-SWMM coupled model simulations produced maximum flood depths across the entire study domain (Fig. 3a), with values ranging from 0.05 m to over 1.0 m. Detailed analysis of flood depths around buildings (Fig. 3b) indicated that structures could be at risk even without direct inundation, as flooding of surrounding streets was considered in the vulnerability assessment. The standardized hazard index, derived through normalization of flood depths using Eq. (6), exhibited values between 0 and 1, with higher values (shown in red) concentrated in the eastern portion of the study area (Fig. 3e). This spatial distribution of hazard indices incorporates both direct inundation impacts and the vulnerability of buildings due to flooded surrounding streets.

Our analysis of flood risk distribution under extreme conditions (200-year return period for rainfall and storm surge under the Very high SSP5-8.5 climate scenario for 2100) reveals substantial temporal and land use-specific variations in risk patterns across the study area. Figure 4 illustrates the spatial distribution of flood risk during different time periods for both weekends (a–c) and weekdays (d–f). A clear temporal variation in risk is evident, with distinct patterns emerging between daytime and nighttime periods, as well as between weekends and weekdays. On weekends (Fig. 4c), we observe that daytime risk generally exceeds nighttime risk across most of the study area, as indicated by the predominantly positive risk index differences. This pattern suggests a higher concentration of people in flood-prone areas during weekend days, possibly due to increased recreational activities or different leisure patterns. In contrast, weekdays exhibit a more complex pattern (Fig. 4f). While some areas still show higher daytime risk, there is a notable increase in regions where nighttime risk surpasses daytime risk, particularly in residential areas. This shift likely reflects the movement of people from commercial and industrial areas to residential areas during nighttime hours on workdays.

Land use-specific variations in flood risk

To characterise the spatiotemporal distribution of flood risk indices across specific category of land, we analyse the interaction between land use and flood risk by using the chord diagram, the result reveals distinctive temporal patterns in urban flood risk distribution across different land use types, characterized by three key findings (Fig. 5). First, we observe dynamic shifts in risk patterns between residential and commercial areas, driven by daily population movements. This transfer manifests most prominently in the 20% swing in residential risk (ranging from 15% to 35%) that is inversely matched by commercial area risk patterns (11% to 29%). This finding suggests that flood vulnerability follows population movements rather than being fixed to specific land use types. Second, our analysis reveals distinct temporal signatures in flood risk distribution that correspond to societal rhythms. Weekend-weekday variations demonstrate how urban flood vulnerability is fundamentally linked to weekly social patterns, with residential areas showing peak risk during weekend early mornings (35%) and commercial areas during weekday afternoons (29%). This pattern underscores how flood risk is inherently tied to human behavioural patterns rather than just physical infrastructure characteristics. Third, we find that while some land use types (particularly residential and commercial) show high temporal variability in flood risk, others, such as infrastructure (roads), maintain relatively stable risk levels (24–28%). This stability-variability contrast suggests that certain urban elements serve as consistent risk factors while others act as dynamic risk receptors that vary with human presence. These findings, based on modelling under a 200-year return period for rainfall and storm surge under the very high SSP5-8.5 climate scenario for 2100, demonstrate that effective urban flood risk management must consider not just the spatial distribution of vulnerability but also its temporal dynamics. The results challenge conventional static flood risk assessments and suggest the need for time-sensitive adaptation strategies that account for the dynamic nature of urban vulnerability.

Spatial and temporal variations in flood risk

To determine whether flood risk varies over time at different distances from coastlines, we analyse cumulative risk index for both weekdays and weekends across all scenarios (Fig. 6a). The risk index demonstrates an overall declining trend as distance from the coastline increases, approaching zero at ~3000 m inland. By calculating the difference between weekend and weekday average risk indices at various distances (inset in Fig. 6a), we identified a critical threshold at 680 m. Within 0–680 m, the difference fluctuates between positive and negative values, indicating inconsistent temporal patterns. Beyond 680 m, weekend risk consistently exceeds weekday risk, suggesting distinct population dynamics influence flood risk differently based on distance from coastline. Figure 6b illustrates risk indices for different flooding scenarios (rainfall only, storm surge only, and compound flooding) versus distance from coastline. For storm surge only scenarios, risk indices decrease rapidly with distance, becoming minimal beyond 1000 m. Notably, compound flooding risk substantially exceeds rainfall-only risk between ~500–1200 m from the coastline. This heightened risk in the compound scenario can be attributed to storm surge reducing drainage system efficiency, thereby exacerbating inland flooding during heavy rainfall events.

a Relationship between risk index and distance from the coastline for weekdays and weekends, with inset showing the average risk index difference. b Risk indices for rainfall only, storm surge only, and compound flooding scenarios versus distance from coastline. c Violin plot showing the distribution of distances from the coastline for different land use types. d Land use in the study area.

The violin plot in Fig. 6c provides a quantitative analysis of how different land use types are distributed in relation to coastline proximity. Commercial and industrial areas demonstrate a concentrated distribution with a lower median distance from the coastline, while residential and hotel areas show a more dispersed pattern extending further inland. Recreational areas occupy an intermediate position, and roads display the most uniform distribution across all distances. Examining the spatial distribution of these land use types across the study area (Fig. 6d) provides contextual understanding of this pattern. The map reveals that commercial and industrial zones are predominantly clustered near the harbor and coastal areas, while residential areas are more widely distributed throughout the region, often behind the commercial buffer. This spatial arrangement likely contributes to the observed temporal risk patterns, as population distribution shifts between these areas on weekdays versus weekends. The proximity of commercial and industrial infrastructure to coastlines has important implications for flood risk management, suggesting that critical economic assets may face greater exposure to coastal flooding events, while residential risk patterns are more influenced by inland compound flooding mechanisms.

Night-day risk ratio

To quantify how flood risk varies depending on the time a flood event occurs and to assess the impact of SLR on these variations, we introduced a metric: the Night-Day Risk Ratio (NDRR). The NDRR, calculated as Eq. 1, provides a standardized measure of this day-night risk differential. A positive NDRR indicates higher risk for nighttime flood events, while a negative value suggests higher risk for daytime flood events. This ratio provides a measure of the relative difference between nighttime and daytime flood risks, offering insights into how population distribution at different times influences the potential impact of flood events.

where: \({NDRR}\) is the Night-Day Risk Ratio, \({\bar{R}}_{n}\) is the average of the risk index during the nighttime, \({\bar{R}}_{d}\) is the average of the risk index during the daytime.

Figure 7a illustrates the dynamic nature of flood risk under the 200-year return period for rainfall and storm surge (very high SSP5-8.5 scenario, 2100). The graph reveals distinctly different patterns between weekday and weekend flood events. For weekday flooding (gray line), we observe significantly higher risk when events occur at night. The average nighttime risk index (\({\bar{R}}_{n}\) = 5554) exceeds the average daytime risk index (\({\bar{R}}_{d}\) = 4649) by 19.5%, as calculated by the NDRR. This pattern likely reflects the concentration of population in residential areas during weekday nights. In contrast, weekend flooding events (purple line) show much smaller variations, with nighttime typically presenting only about 1.4% higher risk than daytime, which can be attributed to different population mobility patterns during weekends.

a Temporal dynamics of flood risk during a 24-h period for weekdays (gray) and weekends (purple) under the 200-year return period for rainfall and storm surge (Very high SSP5-8.5 scenario, 2100), showing Night-Day Risk Ratio (NDRR) calculations. b NDRR comparison across different scenarios combining various return periods for rainfall (T50, T100, T200) and storm surge (T50, T100, T200) under current and future climate projections.

Our analysis across multiple scenarios, as shown in Fig. 7b, reveals the complex relationship between climate change, flood timing, and societal impacts. These scenarios encompass various combinations of rainfall (R) and storm surge (S) return periods under different climate change projections. The results demonstrate notable differences in NDRR for compound flooding events across scenarios. Under scenarios with the same storm surge return period, NDRR tends to decrease as rainfall return period increases, suggesting nighttime flood events may become relatively more severe than daytime events. Under climate change scenarios, NDRR significantly increases for 2100 projections. Weekend NDRRs remain consistently low across all scenarios (all below 2%), while weekday NDRRs range from 18.7% to 20.6%. These observed trends highlight the complex interplay between population dynamics and compound flooding events, indicating that future flood risk assessments and adaptation strategies should carefully consider these temporal variations, particularly the potentially increased vulnerability during weekday nights under climate change scenarios.

Discussion

Our study on the impact of human mobility on flood risk in coastal urban areas under climate change scenarios reveals several key insights that have important implications for flood risk management and urban planning. The integration of dynamic population data with hydrodynamic modelling provides a more nuanced understanding of flood risk that challenges traditional static risk assessment approaches. The observed spatial variations show that flood risk gradually decreases with distance from the coastline (Fig. 6a), highlighting the high vulnerability of coastal areas to compound flooding events. This finding is consistent with previous studies that emphasize increased flood risk in coastal areas due to climate change and storm surges28,29. This spatial pattern may be considerably influenced by historical land reclamation practices. As shown in Fig. 8, we identified the study areas within reclaimed areas and coastal areas (within 680 meters of the coastline). This 680-meter threshold closely aligns with the average distance of the reclaimed areas along the coastline in this studied case (i.e., ~650 m), with the slight difference attributable to the unique characteristics of the reclaimed zones, including their irregular boundaries, varied development histories, and non-uniform distributions along the coastline. Land use analysis reveals similar patterns in both comparisons: reclaimed areas have higher proportions of commercial/industrial land (12%) and road infrastructure (31%) than non-reclaimed areas (3% and 16%), paralleling the distribution between coastal areas (14% and 29%) and inland areas (4% and 17%). These land use patterns help explain the observed temporal variations in flood risk between weekdays and weekends, particularly within 680 meters of the coastline, where weekday and weekend risk distributions remain similar. This temporal consistency likely reflects the concentrated distribution of commercial and transportation infrastructure in reclaimed areas, leading to persistent exposure patterns. Beyond the 680 m threshold, weekend risk consistently exceeds weekday risk, indicating that leisure and recreational patterns are increasingly influential in shaping flood risk characteristics in inland areas. The analysis of risk distribution across different land use types, combined with our understanding of reclamation patterns, provides crucial insights for urban planning and zoning policies. The persistent risk contribution in residential areas during nighttime highlights the need for emergency protection measures in these areas, while the contrasting risk pattern observed in commercial and industrial areas suggests that emergency response plans should be tailored to the specific temporal characteristics of different urban areas. These findings highlight the complex relationship between historical development decisions, current land use patterns, and dynamic flood risk characteristics, emphasizing the importance of adopting integrated approaches to coastal urban planning and flood risk management in the context of climate change.

The introduction of the NDRR provides a metric for quantifying the impact of population dynamics on compound flooding events under various climate change scenarios. The observed trend of decreasing NDRR as rainfall return period increases (with constant storm surge) suggests that more extreme rainfall events may disproportionately affect nighttime population distributions. This finding highlights a previously underexplored vulnerability dimension in flood risk assessment. The substantial increase in NDRR projected for 2100 scenarios indicates that climate change will likely exacerbate the discrepancy between nighttime and daytime risk, particularly on weekdays, where NDRRs range from 18.7% to 20.6%. This has profound implications for long-term urban planning and adaptation strategies. Interestingly, the consistently low weekend NDRRs (below 2%) across all scenarios suggest more uniform exposure patterns during non-working days, regardless of climate change intensity. This contrast between weekday and weekend risk profiles emphasizes the critical role of routine population mobility patterns in determining flood vulnerability. Our findings underscore the need for a paradigm shift in flood risk assessment and management strategies. Traditional approaches based on static population distributions may considerably underestimate or mischaracterize risk in urban areas with high population mobility. The development of dynamic flood risk maps that account for temporal variations in population distribution could greatly enhance the effectiveness of early warning systems and evacuation plans. Moreover, the observed land use-specific risk patterns suggest that urban planning policies should consider not only the spatial distribution of different land uses but also their temporal usage patterns. For instance, the high nighttime risk in residential areas might necessitate the implementation of flood-resistant building codes or the strategic placement of flood-defining infrastructure to protect these areas.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the critical importance of incorporating population dynamics into compound flood risk assessments in coastal urban environments. The complex interactions between rainfall-surge compound flooding and human activity patterns create distinct risk distributions that traditional static assessments fail to capture. This dynamic relationship becomes increasingly critical as sea levels rise, highlighting the need for time-sensitive adaptation strategies that consider both the physical processes of compound flooding and urban rhythms. As coastal cities worldwide face mounting challenges from climate change and rapid urbanization, such integrated approaches to flood risk assessment will be crucial for developing more effective protection measures for vulnerable populations and infrastructure.

Methods

Urban flood dynamic risk framework

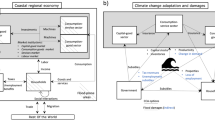

To better understand the impact of flood occurrence at different moments on flood risk, we have developed an innovative dynamic risk assessment framework. Traditional flood risk assessments typically employ a static approach, using the risk equation: Risk = Exposure × Hazard × Vulnerability. However, this method overlooks the dynamic characteristics of risk factors that change over time. To address this limitation, we propose a dynamic risk assessment framework, as illustrated in Fig. 9. This framework pays particular attention to the dynamic nature of exposure, which refers to the population, infrastructure, and natural or artificial resources that may be affected by flooding. Our study primarily focuses on the dynamic changes in population distribution. Recognizing that urban population distribution undergoes substantial changes throughout the day, we introduced a dynamic population distribution model to accurately capture these time-dependent exposure variations. Our dynamic risk assessment model can be represented as Eq. 2:

where: \(R(t)\) is the dynamic risk at time \(t\), \(E(t)\) is the dynamic exposure at time \(t\), \(H\) is the hazard, \(V\) is the vulnerability.

In this framework, Dynamic Exposure: Based on a dynamic population density model, we considered census data and passenger flow data, combined with building classification information, to generate population distribution maps for different time periods. Vulnerability: The vulnerability index incorporates multiple influencing factors, such as the proportion of elderly and child populations, reflecting the community’s sensitivity to flooding. Hazard: Flood hazard was simulated by coupling LISFLOOD and SWMM models, considering the interaction between drainage networks and surface runoff. This generated maximum water depth distribution maps for different scenarios, from which hazard indices were determined.

Dynamic population distribution model and exposure

This study developed a comprehensive dynamic population density estimation method, as shown in Fig. 10. The method integrates three key data sources: the 2021 Hong Kong Population Census (covering 1622 census districts with detailed demographic information), the 2011 Hong Kong Transport Department’s Household Travel Survey (encompassing 121,204 single-day travel records from 35,401 households across 4863 traffic analysis areas), and real-time location-based services (LBS) data from the Baidu Huiyan platform (https://huiyan.baidu.com/). Although the travel survey data is relatively dated, comparative analysis with 2020 metro data30 indicates that it still accurately reflects Hong Kong’s overall travel patterns. Our method consists of three main components: generation of baseline population distribution maps, delineation of urban functional areas and their corresponding human activity patterns, and hourly population distribution estimation based on these foundational data.

First, we constructed baseline population distribution maps as the foundation for our dynamic population model. We constructed two critical baseline population distribution maps: a nighttime baseline map at 4:00 A.M. and a daytime baseline map at 12:00 A.M. The nighttime baseline map comprises local residents and overnight visitors. The distribution of local residents is based on census data, where we allocated census district data to 10 m × 10 m standard grids according to area proportions, with density adjustments made using building height data. Overnight visitors were distributed according to hotel occupancy rate data provided by the Hong Kong Tourism Board, proportionally allocated based on the bed capacity of each hotel.

The daytime baseline map includes two components: the remaining population in residential areas and the influx population in non-residential areas. The remaining population in residential areas is calculated based on the stay-at-home rates of different population types. Through analysis of travel survey data, we determined the stay-at-home rates for various population groups during the 12:00–13:00 period on weekdays: 7% for employed population, 53% for unemployed population, 38% for retired population, 12% for students (lunch time), 64% for housewives/househusbands, and 83% for disabled persons. The influx population in non-residential areas is derived from the total outflow population (nighttime total population minus the remaining population in residential areas during daytime, plus day visitors to Hong Kong) and allocated based on building area, height, and functional weights. Through analysis of travel survey and LBS data, we identified 11:00 A.M. as the peak activity time across various functional areas and used this as a benchmark to calculate the maximum potential population in non-residential areas. The functional weight parameters were determined based on field surveys and relevant literature: 1.0 for office areas, 0.8 for commercial areas, 0.7 for schools, 0.5 for industrial areas, and 0.3 for open spaces.

Urban functional area division and activity pattern recognition were crucial steps for accurate estimation of dynamic population distribution. The division of urban functional areas employed a multi-source data fusion method, integrating the Hong Kong Planning Department’s 2021 land use data and OpenStreetMap’s points of interest (POI) data. We adopted a hierarchical classification approach, first dividing major categories based on land use data, then further subdividing based on building types and POI density, and finally fine-tuning based on population activity patterns. As shown in Fig. 10, we divided urban space into residential areas, office areas, school areas, industrial areas, commercial areas, open spaces and recreational areas, and other areas. Each functional area has unique characteristics that determine its temporal population distribution patterns.

Based on the baseline population distribution maps and functional area activity patterns, we developed an hourly population distribution estimation methodology. We employed an improved gravity model to estimate hourly population distribution. The model expression is as follows:

where \({F}_{{ij}}\left(t\right)\) represents the population flow from area \(i\) to area \(j\) at time\(\,t\), \({P}_{i}\) is the population base of area \(i\), \({A}_{j}\left(t\right)\) is the attractiveness of area \(j\) at time \(t\), \({e}^{-{{{\rm{\beta }}}}{d}_{{ij}}}\) is the distance between areas \(i\) and \(j\), \({{{\rm{\beta }}}}\) is the distance damping parameter (calibrated to 0.15), and \(T\left(t\right)\) is the time adjustment factor.

We constructed 24 h origin-destination matrices, with grid-level population calculations divided into two categories:

Population of residential grid \(i\) at time \(t\):

Population of non-residential grid \(i\) at time \(t\):

where \({P}_{i}^{{res}}\left(t\right)\) is the population of residential grid \(i\) at time \(t\), \({P}_{i}^{{non}}\left(t\right)\) is the population of non-residential grid \(i\) at time \(t\), \({P}_{i}^{{res}}\left(0\right)\) is the initial population of residential grid \(i\), \({P}_{i}^{{base}}\) is the baseline population of non-residential grid \(i\), \({C}_{i}\left(t\right)\) is the activity factor of grid \(i\) at time \(t\), \({O}_{{ij}}\left(t\right)\) is the outflow from grid \(i\) to grid \(j\) at time \(t\), and \({I}_{{ji}}\left(t\right)\) is the inflow from grid \(j\) to grid \(i\) at time \(t\).

To generate continuous 24-h population distribution, we used cubic spline interpolation for temporal interpolation and applied a 10 × 10 grid Gaussian smoothing filter to eliminate spatial noise, while maintaining the total population conservation constraint. We also considered weekday/weekend differences and special patterns for holidays by constructing different activity coefficient matrices for various temporal scenarios.

Dynamic exposure reflects how population distribution changes over time, leading to varying levels of vulnerability at different times of day and days of the week. For instance, commercial areas may have higher exposure during weekday daytime hours due to the influx of workers, while residential areas may have higher exposure at night. To ensure comparability between different variables, we employed standardization, using Eq. (6) to scale the variables of each driving factor between 0 and 1. The dynamic population distribution model provides critical exposure data for subsequent risk assessments, enabling us to more accurately evaluate flood risks at different times and locations. This, in turn, offers more targeted decision support for urban planning and emergency management.

where: \(X\) is the normalized value, \(x\) is the original value, \(\min \left(x\right)\) is the minimum value in the dataset, and \(\max \left(x\right)\) is the maximum value in the dataset.

Vulnerability

Hong Kong’s census data provided a rich set of socioeconomic indicators, covering multiple aspects at both individual and household levels. These panel data offered unique values for each Traffic Planning Unit (TPU), enabling an in-depth analysis of vulnerability characteristics across different urban areas. In constructing the vulnerability index, we focused particularly on groups that might be more susceptible to flood events, such as the elderly, children, and women. To comprehensively assess vulnerability, we selected eight key socioeconomic indicators, visually represented in Fig. 2a–h. Specifically, these indicators include: (a) Proportion of population under 15 years old, reflecting the vulnerability of children (b) Proportion of population with low education levels, indicating potentially lower disaster response capabilities (c) Female population ratio, considering potential gender-related impacts in disaster response (d) Proportion of households with high mortgage payments (over HKD 10,000 monthly), reflecting economic pressure (e) Proportion of population over 65 years old, representing the vulnerability of the elderly (f) Proportion of ethnic minorities, considering additional challenges due to cultural and language barriers (g) Proportion of low-income households (monthly income below HKD 10,000) (h) Proportion of low-income population, both (g) and (h) reflecting economic vulnerability.

To eliminate potential biases introduced by differences in numerical magnitudes between indicators, we standardized all variables. The standardization approach allows for meaningful comparisons across heterogeneous indicators by transforming them to a common scale. In our vulnerability assessment methodology, we adopted an equal weighting structure for all standardized indicators, a practice widely employed in contemporary vulnerability research for its methodological transparency and analytical robustness31,32,33. This equal weighting strategy enhances methodological clarity, reduces potential subjective bias in weight assignment, and produces assessments that are less sensitive to parameter uncertainty when empirical evidence for differential weighting is limited. We calculated the vulnerability index by summing all standardized indicator values and dividing by the number of indicators, as shown in Eq. (7):

where \(D\) represents the vulnerability index, \({X}_{D,i}\) is the i-th standardized variable, and \(n\) is the total number of variables. This method not only simplifies the calculation process but also makes the interpretation of the vulnerability index more intuitive, with the final index values ranging between 0 and 1.

Flood hazard assessment method and validation

To effectively simulate urban flood processes and serve as a tool for hazard analysis, we employed a coupled system of drainage network and surface runoff models. This system combines two widely recognized models: SWMM and LISFLOOD. SWMM is a rainfall-runoff model based on one-dimensional Saint-Venant equations, specifically designed to simulate hydrodynamic processes in urban drainage networks. LISFLOOD, on the other hand, is a surface runoff model based on two-dimensional shallow water equations, capable of effectively simulating urban surface flood processes. By exchanging information at connection nodes (manholes), we organically integrated these two models to achieve more precise flood simulation. The effectiveness of this coupled model has been validated in previous studies34,35,36.

The model parameters in Supplementary Table 1. were calibrated using a systematic two-step approach. Initially, we established appropriate parameter ranges by conducting a comprehensive literature review of similar urban flooding studies37,38,39. This provided theoretically sound boundaries for each parameter. Subsequently, we refined these parameters through an iterative calibration process using observational data from the severe flooding event that affected Hong Kong on September 7–8, 2023. This calibration focused primarily on matching the simulated maximum flood depths with observed flood depths at key monitoring locations throughout the study area. The calibration process involved adjusting parameters within their literature-established ranges until the model achieved optimal performance, quantified by minimizing the root mean square error (RMSE) and Nash efficiency coefficient (NSE) between simulated and observed maximum flood depths. This calibration approach ensured that our model could accurately reproduce historical flooding patterns while maintaining physically realistic parameter values, thus enhancing the reliability of future flood simulations.

We selected the extreme rainfall event that occurred in Hong Kong from September 7 to 8, 2023, to validate the model’s accuracy. This event set a record for the highest hourly rainfall (158 mm) since records began in 1884, more than doubling the black rainstorm warning standard (70 mm). Following the flood, we conducted a field survey of inundation points in Hong Kong on September 9, obtaining observational data of maximum water depths through interviews and measurements of flood traces. Supplementary Fig. 1 presents a comparison between model simulation results and observational data. In Supplementary Fig. 1a, the correlation coefficient (R²) between simulated and observed maximum water depths reaches 0.86, with a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 0.18 m and Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) of 0.77. These statistical metrics indicate high model accuracy, as R² values close to 1, low RMSE values, and NSE values above 0.75 all suggest excellent performance (Detailed comparative data can be found at. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15128479). Supplementary Fig. 1b, c visually compares the spatial distribution of simulated and observed water depths, further confirming the model’s reliability. These results collectively suggest that our coupled model has good applicability in the study area, laying a solid foundation for subsequent simulation analyses.

Design scenarios

According to Sklar’s Theorem40, any bivariate joint distribution function can be connected through a Copula function that links its marginal distribution functions. In this study, we fitted the marginal distributions of daily maximum water level and 24-h cumulative rainfall using gamma distributions, and after comparative analysis, selected the Joe Copula function to model the dependence structure between these two variables. The data spans from 1 January 1960 to 30 September 2023, with maximum water level records from Hong Kong’s tide observation station (Quarry Bay) and daily cumulative rainfall records from the Hong Kong Observatory station.

Supplementary Fig. 2(a) shows a scatter plot of maximum water level and 24-h cumulative rainfall, dividing the data into four zones based on their respective 95% quantile values: Zone 1 (red points) represents compound flooding events (with both extreme sea levels and extreme rainfall), Zone 2 (yellow points) represents events with extreme rainfall without extreme sea levels, Zone 3 (blue points) represents events with extreme sea levels without extreme rainfall, and Zone 4 (gray points) represents non-extreme events. Our joint return period analysis focuses primarily on the compound extreme events, which are characterized by both high water levels and extreme rainfall and are most likely to cause severe compound flooding.

Supplementary Fig. 2b displays the combinations of maximum water level and 24-h cumulative rainfall under different joint return period scenarios. Each curve represents water level-rainfall combinations with the same joint return period (ranging from 3 to 500 years). The points marked on the graph (such as Ellen, Brenda, Hope, etc.) represent specific historical extreme events. Through these joint return period curves, we determined the critical parameter combinations for the 50-year, 100-year, and 200-year return period scenarios, which reflect the most likely structure of compound flood events. Supplementary Table 2 lists the peak storm surge water levels and 24-h cumulative rainfall values for different joint return periods. As the return period increases from 50 to 200 years, the event intensity gradually increases, providing a progressive design that enables us to evaluate the impact of compound events of varying intensities on urban flood risk.

Our study employs a comprehensive approach to assess flooding hazards by considering compound events of storm surge and rainfall, as well as their individual contributions. Based on joint return periods, we designed scenarios that include compound flooding (storm surge plus rainfall), rainfall-only flooding, and storm surge-only flooding. The return periods examined include 50-year, 100-year, and 200-year events to capture a range of hazard intensities. To account for future climate change impacts, we incorporated scenarios for the years 2060 and 2100 under both medium emission pathway (SSP2-4.5) and very high emission pathway (SSP5-8.5). This approach resulted in a total of 75 distinct cases that provide a robust basis for flooding risk assessment under varying conditions (Supplementary Table 3).

For the medium emission scenario (SSP2-4.5), we referenced the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) CMIP6 projections (https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/), which estimate daily rainfall increases of 10.7% by 2060 and 15.7% by 2100. Under the very high emission scenario (SSP5-8.5), daily rainfall is projected to increase more dramatically—by 10.0% by 2060 and 28.8% by 2100. Sea level rise projections were based on IPCC AR6 estimates, with medium emissions (SSP2-4.5) scenarios indicating rises of 0.26 m by 2060 and 0.56 m by 2100. For very high emissions (SSP5-8.5), more severe sea level rises of 0.30 m by 2060 and 0.78 m by 2100 are anticipated1. It’s worth noting that climate change impacts on storm surge levels remain controversial, with some studies suggesting increases41,42,43 and others indicating decreases44,45, with substantial regional variability. Due to these inconsistencies, our study does not consider potential changes in storm surge intensity due to climate change, focusing instead on the more established projections of sea level rise and rainfall intensification.

To transform these static values into dynamic simulations, we adopted a composite timeline model. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3a, we combined astronomical tide and design storm surge curves to create a time series of water levels. For rainfall, we assumed a spatially uniform distribution following a symmetrical triangular distribution over time. This approach simplifies model inputs while retaining key event characteristics. Supplementary Fig. 3b showcases the complex drainage system in the study area. These detailed drainage system data, provided by the Hong Kong Drainage Services Department, include key information such as pipe diameters, lengths, and invert levels, offering precise infrastructure parameters for the model.

Data availability

The data used in this study were obtained from various sources, including government databases, meteorological records, and field investigations. Supplementary Table 4 presents an overview of the data types, their record periods, and sources. The datasets of the main results in this article are available at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29087948.

Code availability

Code used in the analysis is available on request from the corresponding author.

References

IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2018).

Zscheischler, J. et al. A typology of compound weather and climate events. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 333–347 (2020).

Camus, P., Haigh, I. D. & Nasr, A. A. Regional analysis of multivariate compound coastal flooding potential around Europe and environs: sensitivity analysis and spatial patterns. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 2021–2040 (2021).

Wahl, T., Jain, S. & Bender, J. Increasing risk of compound flooding from storm surge and rainfall for major US cities. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 1093–1097 (2015).

Bevacqua, E. et al. Higher probability of compound flooding from precipitation and storm surge in Europe under anthropogenic climate change. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw5531 (2019).

Bevacqua, E. et al. More meteorological events that drive compound coastal flooding are projected under climate change. Commun. Earth Environ. 1, 47 (2020).

Xu, K. et al. Climate change impact on the compound flood risk in a coastal city. J. Hydrol. 626, 130237 (2023).

Zhong, M. et al. A study on compound flood prediction and inundation simulation under future scenarios in a coastal city. J. Hydrol. 628, 130475 (2024).

Ohenhen, L. O. et al. Disappearing cities on US coasts. Nature 627, 108–115 (2024).

Kirezci, E. et al. Projections of global-scale extreme sea levels and resulting episodic coastal flooding over the 21st Century. Sci. Rep. 10, 11629 (2020).

Raduszynski, T. & Numada, M. Measure and spatial identification of social vulnerability, exposure and risk to natural hazards in Japan using open data. Sci. Rep. 13, 664 (2023).

Knighton, J. et al. Flood risk behaviors of United States riverine metropolitan areas are driven by local hydrology and shaped by race. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2016839118 (2021).

Koks, E. E., Jongman, B., Husby, T. G. & Botzen, W. J. Combining hazard, exposure and social vulnerability to provide lessons for flood risk management. Environ. Sci. Policy 47, 42–52 (2015).

Wing, O. E., Pinter, N., Bates, P. D. & Kousky, C. New insights into US flood vulnerability revealed from flood insurance big data. Nat. Commun. 11, 1444 (2020).

Sekimoto, Y., Shibasaki, R. & Kanasugi, H. PFlow: reconstructing people flow recycling large-scale social survey data. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 10, 27–35 (2011).

Tang, J. et al. Resilience patterns of human mobility in response to extreme urban floods. Natl. Sci. Rev. 10, nwad097 (2023).

Haraguchi, M. et al. Human mobility data and analysis for urban resilience: a systematic review. Environ. Plan. B 49, 1507–1535 (2022).

Rajput, A. A., Liu, C., Liu, Z. & Mostafavi, A. Human-centric characterization of life activity flood exposure shifts focus from places to people. Nat. Cities 1, 264–274 (2024).

Balistrocchi, M., Metulini, R., Carpita, M. & Ranzi, R. Dynamic maps of human exposure to floods based on mobile phone data. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 3485–3500 (2020).

Moftakhari, H. R. et al. Compounding effects of sea level rise and fluvial flooding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9785–9790 (2017).

Perks, R. J., Bernie, D., Lowe, J. & Neal, R. The influence of future weather pattern changes and projected sea-level rise on coastal flood impacts around the UK. Clim. Change 176, 25 (2023).

Zellou, B. & Rahali, H. Assessment of the joint impact of extreme rainfall and storm surge on the risk of flooding in a coastal area. J. Hydrol. 569, 647–665 (2019).

Sirenko, M., Comes, T. & Verbraeck, A. The rhythm of risk: exploring spatio-temporal patterns of urban vulnerability with ambulance calls data. Environ. Plan. B 51, 23998083241272095 (2024).

Wang, T., Wang, H., Wang, Z. & Huang, J. Dynamic risk assessment of urban flood disasters based on functional area division—A case study in Shenzhen, China. J. Environ. Manage. 345, 118787 (2023).

Kulp, S. A. & Strauss, B. H. New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal flooding. Nat. Commun. 10, 4844 (2019).

De Dominicis, M. et al. Future interactions between sea level rise, tides, and storm surges in the world’s largest urban area. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087002 (2020).

Oddo, P. C. et al. Deep uncertainties in sea-level rise and storm surge projections: Implications for coastal flood risk management. Risk Anal 40, 153–168 (2020).

Wolff, C., Nikoletopoulos, T., Hinkel, J. & Vafeidis, A. T. Future urban development exacerbates coastal exposure in the Mediterranean. Sci. Rep. 10, 14420 (2020).

Peng, N. & Liu, X. The impact of urban scaling structure on the local-scale transmission of COVID-19: a case study of the omicron wave in Hong Kong using agent-based modeling. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 114, 1–19 (2024).

Nandi, A., Mandal, A. & Wilson, M. Can the approach of vulnerability assessment facilitate identification of suitable adaptation models for risk reduction?. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 64, 102480 (2021).

de Brito, M. M., Evers, M. & Almoradie, A. A systematic review and future prospects of flood vulnerability indices. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 1513–1530 (2021).

Müller, V. I. et al. Limitations and considerations of using composite indicators to measure vulnerability to natural hazards. Sci. Rep. 12, 5714 (2022).

Wu, X. et al. Scenario-based projections of future urban inundation within a coupled hydrodynamic model framework: a case study in Dongguan City, China. J. Hydrol. 547, 428–442 (2017).

Wu, X., Wang, Z., Guo, S., Lai, C. & Chen, X. A simplified approach for flood modeling in urban environments. Hydrol. Res. 49, 1804–1816 (2018).

Liu, P., Xue, C., Han, M. & Li, S. Process-oriented SWMM real-time correction and urban flood dynamic simulation. J. Hydrol. 616, 128889 (2023).

Sadeghi, F., Rubinato, M., Goerke, M. & Hart, J. Assessing the performance of LISFLOOD-FP and SWMM for a small watershed with scarce data availability. Water 14, 748 (2022).

Huang, Z. et al. Simulation performance evaluation and uncertainty analysis on a coupled inundation model combining SWMM and WCA2D. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 13, 613–627 (2022).

Zhou, S. et al. Study on urban flood simulation based on a novel model of SWTM coupling D8 flow direction and backflow effect. J. Hydrol. 626, 129930 (2023).

Sklar, A. Fonctions de repartition a n dimensions et leurs marges. Publ. Inst. Stat. Univ. Paris 8, 229–231 (1959).

Lin, N., Kopp, R. E., Horton, B. P. & Donnelly, J. P. Hurricane Sandy’s flood frequency increasing from year 1800 to 2100. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 12071–12075 (2016).

Chen, J. et al. Impacts of climate change on tropical cyclones and induced storm surges in the Pearl River Delta region using pseudo-global-warming method. Sci. Rep. 10, 1965 (2020).

Garner, A. J. et al. Impact of climate change on New York City’s coastal flood hazard: Increasing flood heights from the preindustrial to 2300 CE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 11861–11866 (2017).

Grossmann-Matheson, G., Young, I. R., Meucci, A. & Alves, J. H. Global changes in extreme tropical cyclone wave heights under projected future climate conditions. Sci. Rep. 14, 31797 (2024).

Muis, S. et al. Global projections of storm surges using high-resolution CMIP6 climate models. Earth’s Future 11, e2023EF003479 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Hong Kong Research Grants Council (RGC) under CRF-YCRG project no. C5002-22Y and NSFC/RGC JRS project no. N_PolyU559/22, and the Hong Kong Polytechnic University under RILS project no. 1-CDLC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhi-Yong Long: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. Huan-Feng Duan: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing— review & editing, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Mohammad Fereshtehpour and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Olusegun Dada and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Long, ZY., Duan, HF. Human mobility amplifies compound flood risks in coastal urban areas under climate change. Commun Earth Environ 6, 413 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02406-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02406-x

This article is cited by

-

Identifying Risk Transition Pattern of Compound Flooding Using the Copula Integrated Markov Chain

Water Resources Management (2025)