Abstract

Vegetation dynamics, as fundamental terrestrial ecosystem components, regulate precipitation and evapotranspiration, directly affecting soil moisture (SM). However, global greening’s impact on SM (drying or wetting) remains uncertain. Here, we integrate multi-source satellite observations, reanalysis data, and outputs from 12 Earth System Models (ESMs) resampled to a unified resolution (0.25°) to quantify historical vegetation-SM couplings (1982–2020) and assess their future persistence (2015–2100). Results show 49.96% and 38.19% of global vegetated areas exhibit greening-drying patterns, driven primarily by vegetation transpiration, especially in grasslands and cultivated land (42-82% sensitivity). The ESMs predicted that soil dryness is exacerbated by vegetation greening and is expected to continue in the future. Despite uncertainties arising from discrepancies in model parameterizations in ESMs and the limited representation of regional-scale feedback across SM datasets, our study provides a robust and comprehensive assessment of the widespread impacts of global vegetation greening on soil drought. The findings highlight that SM carrying capacity must be prioritized in ecological restoration strategies—particularly in vulnerable semi-arid regions where greening intensifies soil drying (e.g., Central Asia, Central Africa, and southern Australia). Our results provide critical references for guiding sustainable ecological restoration and rational cropland expansion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past four decades, a global trend in vegetation greening has been widely observed1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. As a natural “water reservoir”9, vegetation can strengthen the water cycle process through the synchronous increase in total evapotranspiration (TET) and precipitation10,11,12 and plays a significant role in the conservation of regional soil moisture (SM)11,13,14. These processes are closely related to key variables relevant to the sustainable development goals (SDGs), particularly those addressing climate change, water resource management, and land ecosystem health. Undoubtedly, climate change and CO₂ fertilization directly drive vegetation greening, while plants simultaneously respond to atmospheric moisture variations through physiological adaptations (e.g., stomatal regulation and altered water demand)2,3,15. Recent studies have shown that with the intensification of global climate change, greening significantly reduces SM through the coupling of the water cycle with the atmosphere in some regions (including the Sahel, northern India, West Asia, and the Mediterranean coast)13,16. For example, Mankin et al.17 demonstrated that enhanced transpiration from greening induces seasonal soil drought across 42% of global vegetated areas17. This is further evidenced by delayed SM responses to early vegetation growth in the Northern Hemisphere, exacerbating summer soil drought16. Moreover, the intensified water cycle leads to an imbalance in water distribution and further intensifies the probability of extreme climatic events, such as floods, droughts, and heat waves18,19,20,21,22. Conversely, other studies show greening can increase precipitation sufficiently to compensate for ET losses and enhance SM conservation in wetter regions like southeastern China11. By regulating the SM, vegetation supports ecosystem resilience and mitigates drought impacts, emphasizing its indispensable role in achieving global sustainability objectives23.

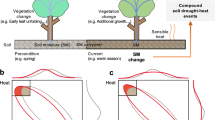

The dominant reasons for the variation in SM may be the fluctuation of regional TET components and the aggravation of the atmospheric water deficit caused by climate change. This process involves the complex coupling of biophysical mechanisms among the atmosphere, vegetation, and soil22,24,25, which integrates atmospheric, land surface, hydrological, and biological processes26,27. Specifically, as the water source of the atmosphere, SM returns approximately 60% of atmospheric precipitation through the TET process28. This indicates that the TET affected by vegetation dynamics (greening or browning) is an important flux term in the terrestrial hydrological cycle system29,30, and its dynamic fluctuation can regulate the recharge of precipitation (various forms and time lags, such as snowfall, rainfall, and snow glacier melt) to SM31. Meanwhile, results based on satellite observations and model simulations show that enhanced greening significantly increases global terrestrial evapotranspiration (>50% contribution), intensifies the water exchange between the land and atmosphere29,30, and increases the risk of drought in arid areas32,33,34,35,36. However, when the increase in precipitation is sufficient to offset the TET, their coupling effectively prevents a reduction in SM11,13. In other words, arid areas may suffer from more severe water pressure, and soil drought will be more serious than atmospheric drought and may spread to ecological drought37. Therefore, distinguishing the pattern of the influence of vegetation dynamics on SM and identifying the water flux term affecting SM are key to revealing the atmosphere-vegetation-soil coupling process under global warming.

However, most current studies have focused on the response of vegetation to carbon11,13,38 and its feedback on temperature39,40,41,42. Quantitative research on the effects of vegetation dynamics on SM (positive or negative) is scarce and controversial12, particularly on a global scale. This information is crucial for agricultural management and ecological restoration10,43. Changes in SM may affect the original vegetation process, especially in desert and arid areas, because fragile desert ecosystems are facing greater ecological security concerns owing to intensified global extreme events22,35. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the impact mechanism of vegetation dynamics on the changing trend in global SM, which is of practical significance for solving the current debate, serving the sustainable production of vegetation, and mitigating water shortage44,45.

Soil moisture directly represents soil water availability and serves as a critical constraint on actual evapotranspiration while providing important feedback to precipitation46. According to the water balance equation, precipitation is partitioned by total ET (comprising foliar interception, canopy evaporation, vegetative transpiration, and bare soil evaporation) before recharging soil moisture and other water storage components (runoff, rivers, lakes, and ice/snow)28. From the perspective of vegetation-soil moisture coupling under climate change, vegetation directly regulates soil water budget by modifying ET partitioning of precipitation19. Furthermore, as ET components feedback approximately 66% of precipitation, vegetation’s biophysical processes indirectly influence soil moisture dynamics through this precipitation feedback mechanism47. Although vegetation also affects complementary relationships between soil moisture and other water storage (e.g., runoff and lakes), these secondary effects are substantially smaller in magnitude than direct influences48. Therefore, analyzing soil moisture sensitivity to water fluxes is essential for understanding vegetation-soil moisture causal coupling, but such studies remain scarce49.

Addressing these research gaps requires support from either in situ measurements or model outputs with complete hydrological cycle representation. Current soil moisture datasets primarily derive from three sources: in-situ observations, satellite remote sensing retrievals, and model simulations (data assimilation/reanalysis products)46. For instance, the Global Land Evaporation Amsterdam Model (GLEAM)50, widely applied in hydrological, climatic and ecological research, has significantly improved spatial resolution in its fourth version (GLEAM4). This framework innovatively combines physically-based modeling with machine learning, representing one of the earliest satellite-based approaches for global ET estimation, validated against 473 global in situ sites. Representative reanalysis datasets include ERA551 and MERRA-252, which assimilate multi-source observations to ensure long-term consistency while providing multi-layer soil moisture data and complete land-atmosphere coupling variables for multivariate analysis. Studies suggest careful consideration of trend differences between surface soil moisture and total column moisture, particularly for global-scale analyses or deep-rooted vegetation regions, where multi-layer soil moisture data are preferable53. Additionally, numerous modeled soil moisture products exist (e.g., GLDAS)54, though their coarse spatial resolution and inter-model parameterization differences necessitate caution when analyzing long-term soil moisture trends and climate response heterogeneity46,55.

To advance the global assessment that is still lacking, this study aims to provide robust evidence for interpreting the causal coupling relationship between vegetation and soil moisture dynamics. By integrating multi-source remote sensing observations and reanalysis data, we reveal vegetation-soil moisture coupling patterns from 1982 to 2020, with particular focus on how vegetation changes affect soil moisture dynamics through evapotranspiration processes, especially greening-induced drying. Through sensitivity analyses of water fluxes, we identify key factors influencing soil moisture variations. Furthermore, using Earth System Model outputs, we validate the persistence of vegetation-soil moisture coupling trends under future climate scenarios (2015–2100). Our results have important guiding significance for a deeper understanding of the water cycle under vegetation–soil coupling and for formulating scientific water resource management and drought mitigation policies. These findings have a positive significance for the accurate expression of vegetation dynamics, their feedback in the ESM, and the simulation of SM and evapotranspiration components.

Results and discussion

Spatial distribution of coexisting greening/browning and drying/wetting

Global vegetation had a trend of 0.34 × 10−3 yr−1 over the past 40 years, with greening pixels accounting for 65.82% (sig. 11.49%) of the global vegetation cover (GVC) area (Fig. 1). The results synthesize the fusion and validation of remote sensing data from multiple sources (NOAA, GIMMS, MODIS, SIF; see Data and methods and Fig. S1). The spatial distribution of vegetation greening and browning shown by the different datasets was more consistent, and the areas of vegetation greening were mainly in central North America, the Indian Peninsula, Turkey, and Northeast Asia. Among them, GIMMS (1982–2015) had the longest span of monitoring data, and its detected trend of vegetation dynamics (greening) was 0.99 × 10−3 yr−1, with a significant greening percentage of 17.03%. In addition, over the last 21 years (2000–2020), the MODIS dataset monitored a vegetation trend of 1.50 × 10−3 yr−1, with a GOSIF of 0.87 × 10−3 W m−2 μm−1 sr−1 yr−1 and significant greening percentages of 31.11% and 32.93%, respectively.

a NOAA NDVI (1982–2020); b GIMMS NDVI (1982–2015); c GO SIF (2000–2020); d MODIS NDVI (2000–2020); and e presents a box-and-whisker plot illustrating vegetation dynamics across seven major global vegetation types: evergreen forests (EF), deciduous forests (DF), mixed forests (MF), scrublands (SB), savannahs (SN), grasslands (GL), and croplands (CL).

The four datasets revealed that vegetation browning occurred in 30% of the GVC, mainly in eastern South America, southern Africa, northwestern Central Asia, and western Australia. The percentages of browning pixels were 34.18% (NOAA), 30.75% (GOSIF), 29.65% (GIMMS), and 23.08% (MODIS). The percentages of significantly browned areas were 1.92% (NOAA), 13.87% (GOSIF), 3.75% (MODIS), and 1.53% (GIMMS). Simultaneously, the greenness of vegetation increased in the southern margin of the Sahara Desert in Africa under an extremely arid climate.

Vegetation greening affects the energy exchange and water cycle24,56. In the context of global vegetation greening (Figs. 2 and S2), 69.04% (ERA, sig. 34.75%) and 54.64% (GLEAM, sig. 30.10%) of the GVG pixels exhibited a decreasing trend in SM, with decreasing rates of 0.66 × 10−3 m3 m−3 yr−1 and 0.87 × 10−4 m3 m−3 yr−1, including southern North America, most of South America, inland Europe, central and southern Africa, central Asia, and Australia. Since 2000, SM decreases were detected in 62.04% (ERA, sig. 17.37%) and 52.73% (GLEAM, sig. 18.44%) of the GVC pixels, with rates of decline of 0.56 × 10−3 m3 m−3 yr−1 and 1.32 × 10−4 m3 m−3 yr−1, respectively. The percentages of pixels with a significant increase in SM were 30.96% (ERA, sig. 7.99%) and 45.36% (GLEAM, sig. 25.58%); they were distributed only in regions such as northeastern North America, Asia, eastern Africa, and South Asia.

a ERA SM (1982–2020); b GLEAM SM (1982–2020); c ERA SM (2000–2020); d GLEAM SM (2000–2020); and e presents a box-and-whisker plot illustrating soil moisture dynamics across seven major global vegetation types: evergreen forests (EF), deciduous forests (DF), mixed forests (MF), scrublands (SB), savannahs (SN), grasslands (GL), and croplands (CL).

To further assess the impact of vegetation dynamics on SM, we examined vegetation and SM dynamics for each of the seven vegetation types. Significant greening was often accompanied by a decrease in SM. At the 40-year scale, the rates of SM change in cropland were −1.13 × 10−3 m3 m−3 yr−1 (ERA) and −2.90 × 10−4 m3 m−3 yr−1 (GLEAM), which corresponded to a greening trend approximately 1.56 times that of the global vegetation cover area. At the 20-year scale, the decreasing trend in SM in forest systems (including evergreen, deciduous, mixed forests, and savannahs) was moderate, with an increasing trend in individual vegetation types and corresponding to a greening trend that was lower than the global average.

Causal-coupling relationship between vegetation and SM

Conventional trend tests were used to assess vegetation dynamics and soil moisture dynamics over the past 40 years. However, the different effects (positive and negative) of vegetation dynamics on SM require further study if they are to be clarified12,57,58. We categorized the causal-coupling relationships into four types according to the changes in vegetation dynamics and SM. In order to gain a deeper understanding of the extent and magnitude of greening-induced drought in the coupled vegetation-soil moisture relationship, we first identified the pixels with vegetation greening and SM decline (Figs. 3 and S3), considering that enhanced vegetation activity may respond negatively to SM according to the Granger causality hypothesis (greening G-caused drying, denoted as G-D). This was mainly located in the United States, Mexico, most of South America, Central Africa, Northern Europe, Central Asia, Northeastern Asia, and Eastern Australia (49.96% and 38.19% for NOAA-ERA, and NOAA-GLEAM-based monitoring, respectively). Enhanced vegetation activity had a possible favorable impact on SM when vegetation greening and SM increased (greening G-caused wetting, denoted as G-W), which was mainly located in central North America, southern Africa, the southwestern side of the Sahara Desert, and the Indian Peninsula (22.74% and 34.68% for NOAA-ERA, and NOAA-GLEAM-based monitoring, respectively). As a result of climate change and anthropogenic interventions, vegetation activity continues to increase, and irrigation and physiological acclimatization lead to a significant increase in evapotranspiration as the vegetation receives more water from the root zone, resulting in a significant decrease in soil moisture. Additionally, the vegetation canopy structure affects soil moisture by intercepting precipitation distribution. These patterns align with watershed-scale field measurements. For instance, Ren et al. used paired-catchment data from China’s Loess Plateau to demonstrate that vegetation restoration in arid regions significantly depletes soil moisture up to 100 cm depth, with afforested catchments showing greater moisture consumption than naturally regenerated areas, particularly during wet years59. Conversely, in humid regions like southern China and parts of India, vegetation greening enhances regional water cycling, with increased precipitation effectively replenishing soil moisture60.

Similarly, we defined browning as G-caused drying (denoted B-D), which was mainly located in northern and southeastern North America, northwestern and eastern Brazil, southern Argentina, south-central Africa, Madagascar, central Eurasia, and southeastern Australia (18.92% and 14.64% for NOAA-ERA and NOAA-GLEAM, respectively). Browning G-caused wetting (denoted as B-W) was predominantly observed near B-D (8.38% and 12.49% for NOAA-ERA and NOAA-GLEAM, respectively). In mid-latitude arid regions, decreased vegetation productivity reduces both carbon sequestration and evapotranspiration, resulting in inadequate precipitation for soil moisture replenishment61. While afforestation initiatives in these dry areas can temporarily enhance water storage through irrigation, leading to concurrent vegetation browning and soil moisture increase, the unsustainable water inputs and carbon-water trade-offs in land-atmosphere coupling will ultimately alter long-term coupling patterns62,63.

Structural and functional differences in vegetation communities can have different effects on SM64. Our results showed that, globally, the greening of forest systems had a lower average state of water retention than that offset by vegetation activities (Fig. 3). For example, the G-D combination in the mixed forest systems accounted for 56.04% (ERA) and 37.17% (GLEAM), whereas G-W accounted for 19.64% and 36.47%, respectively, followed by evergreen forests and deciduous forests. This suggests that although an increase in vegetation greening can enhance the water cycle through precipitation, the decrease in SM caused by the transpiration of vegetation is not negligible13,16,20. Furthermore, our results showed that in EF, B-D accounted for 25.10% and 18.41%, respectively, while B-W accounted for 8.95% and 17.49%, respectively. A similar situation was observed in mixed and deciduous forests. Savanna, grassland, and cropland showed intermediate characteristics between forests and scrubs. The percentage of G-D was approximately 40–50%, which was slightly larger than that of G-W, which was approximately 19-36%. However, the percentages of B-D and B-W were generally <20%.

Subsequently, the correlation between the vegetation NDVI and SM was analyzed grid-by-grid for the four specified types. Correlation analyses showed that vegetation dynamics and SM had a generalized positive pattern (55.31% for ERA and 62.73% for GLEAM) in space (Fig. 3). Significant negative correlation patterns were observed mainly in Europe, Central Africa, and southeastern China. The results of Granger causality tests for the two sets of SM data and vegetation dynamics indicators (VIs) showed that the proportionality coefficients of vegetation dynamics as the Granger cause and effect of SM changes were 1.07 (ERA) and 0.91 (GLEAM) at a confidence level of p < 0.01 (Fig. S4). However, temporal scales revealed different characteristics.

Although vegetation NDVI and SM exhibited a positive correlation pattern across more than 55% of the spatial extent, their positive correlations in all four regions showed a fluctuating downward trend over time (Fig. 4). The most significant decline occurred in the B-W region, with a rate of 0.4 × 10⁻³ per year. Additionally, different datasets displayed greater variability when monitoring the correlation between NDVI and SM in the G-D and B-W regions, whereas the results for these regions were more consistent. These findings suggest that vegetation-SM coupling relationships exhibited substantial spatiotemporal heterogeneity influenced by varying vegetation dynamics and SM change patterns.

Sensitivity of soil moisture to water flux under the influence of vegetation

To understand how vegetation dynamics influence SM changes through water flux terms in the terrestrial water cycle on a global scale, we used the classical global water balance equation for terrestrial ecosystems to derive systemic soil water storage (WB)44,65,66 and selected water flux terms for the three components of evapotranspiration (foliar interception, vegetative transpiration, and bare soil evapotranspiration) to conduct a sensitivity analysis of SM (Fig. 5)19,37. The results showed that SM dynamics accounted for the largest percentage of the sensitivity to ET, at 46.38% (ERA) and 65.57% (GLEAM). Canopy interception accounted for approximately 28.73% and 18.43% and was dominated by forest ecosystems in the northern part of the Eurasian continent, Canada, and rainforests in Africa and Brazil. Bare ground evapotranspiration accounted for approximately 12.31% and 9.35%, mainly in Canada, eastern Russia, southeastern Europe, and both sides of the 10°N latitude line in China and Africa. Systematic soil water storage accounted for approximately 12.58% and 6.65%, mainly in the vicinity of the Great Lakes in the USA, central Europe, northeastern Asia, and the southern Sahara Desert, dominated by cropland and grassland ecosystems.

For evergreen forest systems, SM was the most sensitive to canopy interception, with sensitivity weights of 49.07% (ERA) and 55.83% (GLEAM). For example, our results revealed that SM is sensitive to canopy interception in most of the Amazon, whereas direct soil evaporation is a sensitive water flux term for SM in the southern dry zone with poor vegetation cover. This is in line with the findings of a previous study on vegetation dynamics in the dry and wet Amazon67. SM was more sensitive to evapotranspiration in deciduous and mixed forests, with percentages of 41.12% (ERA), 60.30% (GLEAM), 46.60% (ERA), and 66.11% (GLEAM), respectively. Soil and water retention altered by forest policy establishment in China from 2000 to 2010 increased by 12.9% and 3.6%, respectively10. As a sensitive water flux term, SM sensitivity to soil water storage occurred mostly in croplands, with proportions of 21.55% (ERA) and 11.75% (GLEAM), respectively. Croplands are mostly artificially recharged; therefore, SM tends to interact more with groundwater. In general, the percentage of SM sensitivity to soil evaporation fluctuated in the range of 5–12% and was generally distributed in the eastern and northern parts of the continent.

Canopy interception often became a sensitive water flux term for SM in vegetation types in which trees are the dominant species. In contrast, vegetation evapotranspiration and soil water storage were dominant in areas with herbaceous or annual vegetation types such as grasslands and croplands. This may be related to the mode of recharge in these areas (e.g., grasslands tend to have seasonal precipitation and croplands tend to be artificially irrigated) as well as the degree of groundwater burial (which tends to be greater for grasslands than for the other types, averaging up to 16.25 m)12,68. Vegetation can extract water by enhancing the water cycle processes of SM transported through atmospheric circulation, allowing precipitation and runoff to redistribute water resources, during which vegetation redistribution regulates precipitation through the canopy and root systems, which in turn influences SM14. Some studies have similarly suggested that differences in SM trends may be because surface and deeper SM are controlled by different processes, including evapotranspiration induced by warming and the increase in demand driven by increased surface SM. Increased warming-induced evapotranspiration demand drives a decrease in surface SM, whereas deep SM is controlled more by antecedent moisture conditions and vegetation activity22.

Soil dryness exacerbated by vegetation greening under future climate change

To assess the future evolution of soil dryness affected by vegetation and quantitatively analyze their G-causal effects, we combined the GPP and SM data output from 12 ESMs in CMIP6 to evaluate the drought risk of SM under the influence of vegetation dynamics in global terrestrial ecosystems (Fig. 6 and Table S1). The trends of future GPP under the SSP245 and SSP585 scenarios were 2.18 kg m−2 s−1 yr−1 and 5.03 kg m−2 s−1 yr−1, respectively, while the trends of SM were 0.13 × 10−3 kg m−2 yr−1 and 3.61 × 10−3 kg m−2 yr−1, respectively. SM significantly decreased, similar to the meta-percentages of 31.05% and 30.72%, respectively. This implies that the future enhancement in vegetation activities will continue to maintain different impacts. The drought risk faced by terrestrial SM in the Southern Hemisphere was higher than that in the Northern Hemisphere. Regarding the Northern Hemisphere, the greening trend of vegetation was roughly the same in the middle and high latitudes; however, SM showed a decreasing trend in the mid-latitudes, and the low and high latitudes showed a greater increase in SM. For example, South America and Africa contributed more to the future global GPP; however, the former had a decreasing trend in SM, and the latter had an increasing trend. Eastern China, India, and the Malay Archipelago also showed significant greening trends, with SM-holding effects being more pronounced in India and less pronounced in China. SM above 60°N showed an increasing trend; however, Australia and South Africa showed decreasing trends, and vegetation activity was relatively weak in all areas. In addition, Granger causality tests of SM data and vegetation activity indicators under the two future scenarios showed that the significances (p < 0.05) of vegetation as a Granger factor for SM were more than 31.69% (ERA) and 52.06% (GLEAM). In contrast, the significances of SM as a Granger factor for vegetation were 28.46% (ERA) and 30.71% (GLEAM) (Fig. S5).

a, d, g show the spatial distribution of GPP trends. b, e, h are the spatial distribution of SM trends. c, f, i are the variations of GPP and SM with latitude. The light green shading indicates that SM is in an increasing trend, while the light red shading indicates that SM is in a decreasing trend. j is a plot of inter-annual variation in vegetation productivity for historical and future periods. And k is a plot of inter-annual variation in soil moisture for historical and future periods. The data used in this figure are the average of the output values of the 12 ESMs.

Previous studies have shown that >42% of the global vegetation area will continue to exhibit G-D characteristics in the future17,42,69. Moreover, this phenomenon was more pronounced during the summer months when vegetation activity was relatively more intense, implying greater evapotranspiration. This also implies that vegetation greening will cause more droughts in the future, especially the spread from the atmosphere to the soil and ecological drought16,22. Generally, high saturated water vapor pressure differentials or increasing vegetation activity increase the extraction of SM and lead to soil drought consistent with atmospheric drought12. Previous studies have also suggested that increased CO2 and temperatures cause plants to develop self-protective physiological processes and cause plants to develop self-protective physiological stress behaviors, such as stomatal opening and closing70,71, to ensure that their water control is maximized in a survival strategy that increases plant volume72. Our results suggest that vegetation activity acts as a SM sink in some regions globally (e.g., central North America, the southern flanks of the Sahara Desert, parts of northwestern China, India, and southern Africa); however, it is more often vegetation activity that causes soil drought, consistent with atmospheric drought. Vegetation activity often causes a decline in SM (southern China, Europe, central Africa, Brazil, and Australia).

We further explored the persistence of the sensitivity between SM and water flux term under future climate scenarios (Fig. 7). The results suggest that sensitivity of soil moisture to vegetation transpiration in the evapotranspiration component will be further enhanced in the future state of further greening of vegetation. We first examined the future sensitivity of soil moisture to different water fluxes, where SM dynamics accounted for the largest proportion of evapotranspiration sensitivity (78.17%), followed by WB (14.96%) and ES (6.43%), whereas soil moisture had the smallest proportion of EC-sensitive regions. Most of the vegetation types were more consistent with the global state, but there was a significant increase in the share of WB under the scrub (SB) type with a value of 31.00%. The relative importance coefficients of soil moisture to ET indicated that in the vast majority of regions, i.e. 85.23% (SSP245) and 87.20% (SSP585) of the global vegetation cover area, the importance coefficients of ET were positive, and those with importance coefficients exceeding 0.5 accounted for 18.20% (SSP245) and 35.39% (SSP585), respectively. Therefore, in the future, vegetation transpiration will play a more important role in influencing the vegetation-soil moisture coupling relationship.

a SM-ET importance coefficients for the SSP245 scenario. b Spatial distribution of the sensitivity of SM dynamics to the four water fluxes. c SM-ET importance coefficients for the SSP585 scenario. d Statistics on the percentage of SM dynamics sensitivity to the four water fluxes in different vegetation cover types.

Minimizing the limitations of a single dataset by combining the datasets

It is important to point out that some factors affected our determination of the causal coupling relationship between vegetation dynamics and SM because the data are usually derived from model simulations and satellite observations57,58. The monitoring results of vegetation dynamics have always been controversial owing to the updating of sensors and the modification of dataset correction methods41,58,73,74. To address these issue, we integrated four remote sensing products to represent vegetation dynamics: three NDVI products (NOAA AVHRR, GIMMS 3 g, and MODIS-C6) and one high-resolution SIF dataset, which can describe vegetation dynamics well in recent years. Two datasets were selected to represent the SM (based on the ERA5 dataset and the latest version of the GLEAM model data). The latest CMIP6 data were used for future drought risk assessments in the SM.

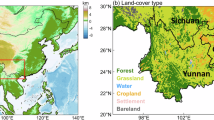

To create a long-term continuous vegetation dataset, we extended the GIMMS NDVI 3 g series to 2020 using a weighted least squares (WLS) method, combining it with NOAA NDVI and applying MODIS NDVI to constrain historical consistency. This reconstruction enhances temporal continuity, preserves consistency with original trends, and improves the robustness of long-term vegetation monitoring (Fig. S1). Crucially, the resulting NDVI time series enables consistent tracking of vegetation dynamics over nearly four decades, which is essential for evaluating global-scale coupling with soil moisture trends. Subsequent evaluation using regression models and probability density functions showed high consistency in spatial and temporal trends across datasets, supporting the robustness of the reconstructed product (Fig. S2). In regions with divergent signals, we recommend verifying findings with high-resolution satellite or ground-based data whenever possible58. To minimize uncertainty, non-vegetated areas were excluded, and analysis was stratified across seven vegetation types using the International Geosphere Biosphere Program (IGBP) land cover products rather than relying on NDVI thresholds (Fig. S6).

Considering that correlation analysis does not have a causal relationship, we specifically introduced the Granger causality test to identify vegetation-soil causality (see “Supplementary data”). The reliability of our experiment was verified by comparing the causal relationships between vegetation dynamics and SM. The Granger causality test, a foundational time series-based causal inference method75,76, employs linear autoregressive models to assess bidirectional predictive relationships in stationary (or cointegrated) systems, offering interpretability for exploratory analyses in ecology, hydrology, and geography77,78. However, as a statistical (non-mechanistic) approach, it requires careful preprocessing (e.g., differencing) to avoid spurious causality from autocorrelation or nonstationarity79. Here, we integrate Granger causality test with correlation and partial correlation analyses to rigorously evaluate vegetation-soil moisture causal coupling. The feedback process was evaluated quantitatively. Given that vegetation feedback to the soil and climate is a complex coupled process, biophysical mechanisms should be considered. For the historical period, we also evaluated the sensitivity of SM to water fluxes, such as evapotranspiration components and WB, using the classical water balance formula, which explains the biophysical influence of vegetation on SM. The material and energy cycle generated by ET can more effectively explain the response and feedback effect of vegetation on climate change80, which remains a prominent topic of ongoing research81. Examples include quantitative assessments at smaller scales and model improvements based on biophysical mechanisms82. Finally, based on these conclusions, a simple application is not advocated in policy designations. It is suggested to consider how to utilize the coupling relationship between vegetation dynamics and SM to optimize the industrial structure based on the research results to provide suggestions and references for future management.

Possible mechanisms in explaining the response and feedback of vegetation activity-soil moisture coupling relationship

As the most basic component of ecosystems, the enhancement of vegetation dynamics is generally regarded as the positive development of regional ecosystems3,60. Climate warming has been shown to enhance vegetation activity, but it may also impose drought stress on soil moisture (SM) through increased atmospheric water demand or physiological water consumption60,83. We further reviewed the coupling relationship between global vegetation dynamics and SM over a long period (1982–2020). Compared with most previous studies8,12,84, our results indicated that the global greening trend continues; however, compared with SM conservation, the phenomenon of SM decline begins to appear in an increasing number of areas. We quantified bidirectional Granger causal links, showing that vegetation dynamics acted as a significant G-cause of SM decline in over 7.7% of vegetated areas (p < 0.05), while SM influenced vegetation dynamics in 7.5% (ERA) and 8.6% (GLEAM) of areas. Greening in Central Eurasia is likely the main cause, followed by Central Africa, the Western United States, and South America. SM content increased in northeast Asia, central North America, and the Indian Peninsula. From the perspective of vegetation cover, the forest system did not conserve SM over a long time scale but aggravated the decline in SM, although this situation has improved in the last two decades. However, the inland water loss in cropland, grassland, and shrub areas has continued to increase over the last two decades.

In grasslands and savannas, vegetation usually regulates access to water based on root depth. In general, these types of vegetation, as well as cultivated vegetation, mainly consume root-zone water (average root depth of 0.2–2.5 m)85. In particular, tall trees or deep-rooted plants in arid regions often develop deeper and larger roots to capture more SM, which can interact closely with runoff and groundwater86,87. This strategy provides patients with an increased chance of survival12. Moreover, any changes in vegetation cover (e.g., deforestation or conversion of forests to other land use types, conversion of cropland to forest, and afforestation) can lead to larger hydrological responses (e.g., greater water production or soil erosion and severe depletion of groundwater)65. This signal reflects the overall reduction in SM, surface water, and groundwater levels and may have a complex coupling relationship with the carbon source sink and the exchange of latent and sensible heat56. It is also believed that this may be attributed to the impact of climate change and humans for more than a decade54,88. In general, vegetation reduces surface albedo and intercepts shortwave radiation24,89. Therefore, vegetation dynamics have different biophysical mechanisms depending on changes in latitude and dry humidity90. For example, studies have shown that forest cover in northern China has a positive impact on the water volume, whereas forest cover in tropical and temperate regions has a negative impact14.

To move beyond confirmation of existing patterns, we introduced a four-type classification framework (G-D, G-W, B-D, B-W) to characterize different vegetation–SM causal interactions. Our coupled analysis showed that increased vegetation activity was responsible for 49.96% (ERA) and 38.19% (GLEAM) of SM decline, and browning was responsible for 18.92% (ERA) and 14.64% (GLEAM) of SM decline in the past 40 years. This framework enables a spatiotemporal mapping of vegetation–SM feedback from a directional perspective. Furthermore, we incorporated multi-source satellite-based ET and water balance products to assess the sensitivity of SM to vegetation-mediated water fluxes across vegetation types, providing mechanistic insight into biophysical feedback processes. Rapid soil moisture depletion is closely related to changes in vegetation transpiration. In 46.38–65.57% of global vegetated areas, soil moisture is more sensitive to vegetation transpiration, particularly in deciduous and mixed forest regions. Canopy interception accounted for approximately 18.43–28.73%.

SM dynamics reflect the fluctuation of water supply and demand processes in the balance of the land water cycle. For example, SM is replenished by precipitation (including retained snow and glacial meltwater), whereas plant transpiration and soil evaporation determine the surplus of SM32. Enhanced vegetation dynamics will extract more water from the soil for survival and growth and will be influenced by the dynamics of atmospheric dryness and plant physiology (changes in stomatal opening and closing due to temperature and carbon dioxide constraints)91. Vegetation dynamics can also indirectly affect soil moisture dynamics by altering precipitation partitioning through influencing radiative effects and local atmospheric cycles64. Water consumption for human activities (agriculture, living, and industry) is provided by rivers, lakes, and underground water, which indirectly affect SM content22. Therefore, SM determines water stress in natural and agricultural ecosystems92.

We projected the persistence of greening-induced soil moisture loss under future scenarios (SSP245 and SSP585) using CMIP6 ensembles and verified the stability of SM sensitivity to water fluxes. This forward-looking analysis further distinguishes our work from past studies12,14. In the future, the G-causality ratio of vegetation dynamics to SM will exceed that of SM to vegetation dynamics (causality ratio >1), with significance ratios of 31.69% (SSP245) and 52.06% (SSP585). The stress of vegetation greening on SM will further increase, and the geographical differentiation law will become more complex. The regulatory role of vegetation transpiration in vegetation–SM coupling will further strengthen, with soil moisture dynamics being more sensitive to vegetation transpiration in 78.17% of global vegetated regions.

Previous studies have shown that the amount of vegetation restored on some arid zones is already above the optimal threshold, indicating that additional vegetation planting will lead to water shortages for human activities, reflecting unsustainable development18. However, vegetation greening was coupled with increased SM in mid-high latitudes, such as in central North America and near arid regions (south of the Sahara Desert, northwest of the Tibetan Plateau, India, and central North America). This effect would be superimposed on inter-annual variations in the water cycle and help mitigate the decline in SM in arid areas13. The lower and middle latitudes (southern China, Central Europe, America, and Australia) exhibited opposite trends. Our results also showed that vegetation browning on SM was not obvious. Therefore, the effects of vegetation greening on SM should be treated dialectically. Vegetation restoration or agroforestry efforts should account for local soil moisture carrying capacity, especially in G-D regions.

Data and methods

To advance the global assessment that is still lacking, we utilized multi-source remote sensing data to construct a comprehensive 40-year satellite observation dataset complemented by two SM datasets derived from climate and biophysical process models. This dataset was employed to evaluate global vegetation and SM dynamics and to explore their coupling effects and driving mechanisms (Fig. 8). We selected the satellite-derived normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) dataset, solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF), and gross primary productivity (GPP) to represent vegetation and ERA5 and GLEAM to represent SM. Fusion data of output values from three MERRA-2 and GLDAS models (CLSM, NOAH, and VIC) were utilized to test the ability of the ERA5 and GLEAM soil moisture datasets to express trends in long-term soil moisture monitoring. We focused on the causal coupling relationship between global vegetation dynamics and SM and quantitatively identified the sensitivity of SM to different water fluxes. Finally, using GPP, SM and water flux data (evapotranspiration components and water storage) from 12 ESMs under historical and two future climate prediction scenarios (SSP245 and SSP585) in CMIP6, we analyzed the possible future drought stress of SM caused by vegetation dynamics.

Satellite observation data

Vegetation dynamic index

This study used the third-generation Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) NDVI (GIMMS NDVI 3 g, 1982–2015). To obtain a longer time series to match the SM for analysis, we used the weighted-least-variance (WLS) fitting method and the AVHRR NDVI (AVHRR NDVI V5, 1982–2020) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) climate data record (CDR) as auxiliary data to establish the functional relationship between GIMMS NDVI 3 g and AVHRR NDVI V5. First, the functional relationship was used to extend GIMMS NDVI 3 g to obtain the first version of its extension data (NG V1), and the median value of the 10 × 10 sliding window was used as a proxy to interpolate and fill the missing values. Therefore, the second function was constructed using the generated NG V1, and the missing value was filled in the same way to obtain the final GIMMS NDVI 3 g extended dataset (recorded as NOAA NDVI). In addition, to verify the accuracy, we selected reconstructed data (NOAA NDVI) from 2000 to 2015 and GIMMS NDVI 3 g for comparison. The results showed that the fitting correlation (slope) between the reconstructed and original datasets and the variance all exceeded 0.98 (Fig. S1).

To further reduce the interference caused by different datasets, we selected NDVI data recorded by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) sensor since 2000 and a new global, OCO-2-based Solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) dataset (GOSIF) with high spatial and temporal resolutions using discrete OCO-2 SIF soundings, remote sensing data from MODIS, and meteorological reanalysis data. Their temporal resolutions were 16 and 8 d, respectively, and their spatial resolutions were 1 km and 0.05°. The sixth version of MODIS alleviated the performance degradation of the fifth version of the data sensor74. The latest remote-sensing inversion variable, SIF, provides a new method for monitoring vegetation photosynthesis in space. Compared with vegetation indices based on remote sensing, SIF has been proven to be more closely related to vegetation photosynthesis and can better capture the variation caused by environmental factors93.

The historical GPP data were derived from a Long-term (1982–2018) global GPP dataset based on the NIRv94 dataset. Based on remote sensing AVHRR data of approximately 40 y and observations from hundreds of flux stations worldwide, this dataset generated global high-resolution long-time series GPP data from 1982 to 2018 at a resolution of 0.05°. The historical data of CMIP6 were compared with the annual synthetic data of the dataset using linear regression.

Land cover

The MODIS Collection 6 annual product provides land cover information at 0.05° × 0.05° resolution, formally designated as the Yearly Climate Modeling Grid (CMG) land cover product (MCD12C1). The classification algorithm incorporates a hidden Markov model-based state-space multi-temporal modeling framework, effectively mitigating spurious land cover changes induced by single-year classification uncertainties95. Accuracy assessments of Collection 6 demonstrate a 73.6% overall accuracy for the primary LCCS (Land Cover Classification System) layer95, representing a significant improvement over previous versions. Notably, the product not only identifies the dominant land cover type but also quantifies sub-grid frequency distributions of land cover classes. This enhanced characterization renders the dataset particularly suitable for investigating global-scale ecological processes and climate change interactions. We aggregated the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme classification types provided by MCD12C1 into seven broad biome types: Evergreen Forests, Deciduous Forests, Mixed Forests, Shrublands, Savannas, Grasslands, and Croplands. Evergreen Forests consist of needleleaf and broadleaf forests, deciduous Forests consist of deciduous needle leaf and broadleaf forests, shrublands are closed and open shrublands, savannas refer to woody savannas and savannas, and croplands consisted of croplands and cropland/natural vegetation mosaics (Fig. S6).

Terrestrial ecosystem water cycle flux data

Here, we used two independent SM datasets covering 1982–2020 to detect the impact of vegetation dynamics on soil root zone moisture over the past four decades. The first dataset was the monthly SM dataset from ERA5. The arithmetic sum of the first four soil layers was selected as a proxy for SM in the root zone. The other was the satellite-derived root zone SM dataset, referred to as the Global Land Evaporation Amsterdam Model dataset (GLEAM v3.5 and v4.2)50. GLEAM is a set of algorithms dedicated to estimate terrestrial evaporation and root-zone SM from satellite data. The GLEAM dataset is based on reanalyzed temperature and radiation, remotely sensed top-level SM, L-band vegetation optical depth (VOD), and snow water equivalent from different satellite sensors; multi-source precipitation forcing was also used. We used the evapotranspiration data from GLEAM, which included vegetation transpiration (ET), soil evaporation (ES), and interception loss (EC). Water flux and soil root zone water data had the same temporal and spatial resolutions (Fig. S7).

The CRU meteorological dataset was developed by the Climatic Research Unit (CRU) of the University of East Anglia and the Hadley Centre (British Meteorological Office). The dataset was generated using angular distance weighting (ADW) interpolation with a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5°. We selected the latest monthly precipitation dataset from 1982 to 2020, resampled it using the nearest neighbor method, and synthesized annual data for analysis.

TerraClimate has good practicability by virtue of the large number of station-based observation results from various networks, such as global historical climate networks, snotels, and raws. The topographic and climatic fields of the annual reference evapotranspiration were closely related to the reference evapotranspiration based on the FLUXNET station. This study selected runoff data from 1982 to 2020 with a resolution of 0.1° × 0.1°. For verification and supplementary explanation, we selected the Linear Optimal Runoff Aggregate (LORA), which is a global gridded synthesis runoff product.

These data can effectively calculate water cycle process parameters as they fully account for water balance and incorporate satellite observations and ground station measurements. Although these data ensure reliable water storage parameters, the uncertainty in water cycle process parameters due to data discrepancies requires further attention.

CMIP6 data

We used the historical output of the sixth phase of the international coupled model comparison program (CMIP6) and the data of 12 Earth system models (ESMs) in two future climate prediction scenarios (SSP245 and SSP585), that is, the simulated data of the gross primary productivity of biomass expressed as carbon (GPP), SM (mrro), E(ET, ES, EC) (Table S1). Data on future evapotranspiration fractions were obtained from historical evapotranspiration fraction shares and future total evapotranspiration data. To further reduce the difference in the simulation data between the different models, all model data were monthly scale data in the r1i1p1 series. The spatial resolution of all data was resampled to 0.5° × 0.5° using the nearest-neighbor interpolation method.

Other SM datasets

To validate the reliability of soil moisture temporal trends, we selected widely used datasets in climate and hydrological research, which are suitable for high-resolution land surface process modeling and atmosphere-land coupling studies as supplementary data.

MERRA-2 (Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2), developed by NASA, is a global reanalysis dataset providing various surface and atmospheric variables, including soil moisture. It has a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.625° and a temporal resolution of hourly outputs. In this study, we utilized monthly aggregated annual data spanning 1982–2020. MERRA-2 integrates satellite and ground-based observations using advanced data assimilation techniques. Although its soil moisture data are primarily model-simulated, they are valuable for global-scale comparative analyses.

GLDAS (Global Land Data Assimilation System), jointly developed by NASA and NOAA, is a land surface assimilation system that combines multi-source observations and model outputs to provide land surface variables, including soil moisture. The dataset has a spatial resolution of 1° × 1°, and we employed monthly aggregated annual data from 1982–2020. GLDAS incorporates multi-source observations (e.g., satellite and in-situ measurements), making it well-suited for hydrological and climate studies. However, in regions with sparse observations, it relies more heavily on model simulations.

Methods

Significance and Granger causality test

The Granger causality test was employed96. Empirically, the soil root zone moisture affects vegetation dynamics, and an autoregressive model can be obtained:

Here, b, k and e are the fitting parameter. The surplus and loss of SM will enhance or reduce vegetation dynamics. If the strength of vegetation dynamics reacts to the SM owing to the action of energy and material flows, the following formula can be obtained:

No absolute correlation is observed between the two autoregressive models. Assuming that they exist in the same time series and that this relationship will affect the prediction, we modeled one time series.

Considering the influence of variable \({VIs}\) on \({SW}\), this time series model becomes

Now assuming that \({VIs}\) has no causal relationship with \({SW}\), and is denoted as H0 \(({\theta }_{0}={\theta }_{1}=\ldots ={\theta }_{j}=0)\), if it passes the significance test, the hypothesis is true, otherwise, the hypothesis is not true.

The t-test and F-test were used to test the significance of correlations and trends.

Weighted-least-variance (WLS) fitting

Compared with the simple minimum variance method, WLS gives each datum a different weighted value during fitting according to the different accuracies of the basic data itself. This method was consistent with the original fitting intention.

\({{VIs}}_{i},i=({\mathrm{1,2}},\ldots ,34)\) is the reference time series, \({{VIs}}_{j},j=({\mathrm{1,2}},\ldots ,39)\) is the time series to be fitted. The polynomial fit with the highest powers of \(N\) and \({r}\) is the inverse matrix of the weighting coefficient.

Sensitivity analysis method based on multiple regression equation model

The terrestrial hydrological cycle97 can be expressed in four terms: precipitation, evapotranspiration, runoff, and soil water storage change (WB)27,44. The annual water balance of a closed-land watershed can be expressed as:

where \(P\) is the annual precipitation of each pixel grid (mm yr−1); O is the amount of water supplied and discharged by the system (mm yr−1); \(\bigtriangleup {WB}\) is the change in soil water reserves of the entire system (mm yr−1); \(R\) is runoff (mm yr−1); and E is evapotranspiration, which includes vegetation, ET, bare soil evaporation, ES, and leaf interception loss, EC, in mm yr−1. We attributed the change in soil water to the combination of P, R, and E. Therefore, we used the multiple linear regression model to assess the importance of \(\bigtriangleup D\) and three evapotranspiration components. The formula is as follows:

where \({\beta }_{i}(i={\mathrm{0,1,2,3,4}})\) is the coefficient of nonrandom variables (representing \(\bigtriangleup {WB}\) and evapotranspiration components), \({\theta }_{i}\) represents the standardized variable coefficient, \(R\) indicates the importance, and the variable corresponding to the maximum regression coefficient of the same pixel was recorded as the importance variable.

Data availability

Data supporting the conclusions of this study are openly available. MODIS NDVI: https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod13a2v006/. GIMMS 3 g NDVI: https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/en/data/9775f2b4-7370-4e5e-a537-3482c9a83d88/; https://www.cen.uni-hamburg.de/en/icdc/data/land/gimms-ndvi3g.html. NOAA NDVI: https://doi.org/10.7289/V5ZG6QH9. GOSIF: https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11050517. NIRv GPP: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12981977.v2. MOD13A2 C6, https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod13a2v006/. GLEAM v3.5a: https://www.gleam.eu/. GLEAM v4.2a: https://www.gleam.eu/. ERA5:https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-single-levels-monthly-means?tab=overview. CMIP6: https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/. LORA Runoff: http://dapds00.nci.org.au/thredds/catalogs/ks32/ARCCSS/LORA/ LORA.html. TerraClimate Runoff: https://www.climatologylab.org/terraclimate.html. CRU TS v. 4.05: https://catalogue.ceda.ac.uk/uuid/c26a65020a5e4b80b20018f148556681. MERRA-2 and GLDAS-2 (VIC, NOAH, CLSM): https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets

Code availability

The data in this study were analyzed with publicly available tool packages in MATLAB and the figures were produced with MATLAB, python, and ArcGIS. All the scripts are available upon requests.

References

Myneni, R. B., Keeling, C. D., Tucker, C. J., Asrar, G. & Nemani, R. R. Increased plant growth in the northern high latitudes from 1981 to 1991. Nature 386, 698–702 (1997).

Ju, J. & Masek, J. G. The vegetation greenness trend in Canada and US Alaska from 1984–2012 Landsat data. Remote Sens. Environ. 176, 1–16 (2016).

Zhu, Z. et al. Greening of the Earth and its drivers. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 791–795 (2016).

Gao, M. et al. Divergent changes in the elevational gradient of vegetation activities over the last 30 years. Nat. Commun. 10, 2970 (2019).

Shen, M. et al. Can changes in autumn phenology facilitate earlier green-up date of northern vegetation?. Agric. Meteorol. 291, 108077 (2020).

Chen, C. et al. China and India lead in greening of the world through land-use management. Nat. Sustain. 2, 122–129 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Spring temperature change and its implication in the change of vegetation growth in North America from 1982 to 2006. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 1240–1245 (2011).

Piao, S. et al. Characteristics, drivers and feedbacks of global greening. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 14–27 (2020).

He, Q. et al. Global patterns of vegetation response to short-term surface water availability. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 14, 8273–8286 (2021).

Ouyang, Z. et al. Improvements in ecosystem services from investments in natural capital. Science 352, 1455–1459 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Divergent hydrological response to large-scale afforestation and vegetation greening in China. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar4182 (2018).

Deng, Y. et al. Vegetation greening intensified soil drying in some semi-arid and arid areas of the world. Agric. Meteorol. 292–293, 108103 (2020).

Zeng, Z. et al. Impact of Earth greening on the terrestrial water cycle. J. Clim. 31, 2633–2650 (2018).

Chen, X. et al. Quantitative association between the water yield impacts of forest cover changes and the biophysical effects of forest cover on temperatures. J. Hydrol. 600, 126529 (2021).

Peng, J. et al. Evidence for the acclimation of ecosystem photosynthesis to soil moisture. Nat. Commun. 15, 9795 (2024).

Lian, X. et al. Summer soil drying exacerbated by earlier spring greening of northern vegetation. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax0255 (2020).

Mankin, J. S. et al. Blue water trade-offs with vegetation in a CO2-enriched climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 3115–3125 (2018).

Deng, L., Yan, W., Zhang, Y. & Shangguan, Z. Severe depletion of soil moisture following land-use changes for ecological restoration: evidence from northern China. Ecol. Manag. 366, 1–10 (2016).

Feng, X. et al. Revegetation in China’s Loess Plateau is approaching sustainable water resource limits. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 1019–1022 (2016).

Yu, L., Liu, Y., Liu, T. & Yan, F. Impact of recent vegetation greening on temperature and precipitation over China. Agric. Meteorol. 295, 108197 (2020).

Christian, J. I. et al. Global distribution, trends, and drivers of flash drought occurrence. Nat. Commun. 12, 6330 (2021).

Lian, X. et al. Multifaceted characteristics of dryland aridity changes in a warming world. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 232–250 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. Future soil moisture will slowdown the advancement of ecosystem productivity in the Northern Hemisphere. Sci. Bull. 70, 347–350 (2025).

Su, Y. et al. Quantifying the biophysical effects of forests on local air temperature using a novel three-layered land surface energy balance model. Environ. Int. 132, 105080 (2019).

Zhou, S. et al. Soil moisture–atmosphere feedbacks mitigate declining water availability in drylands. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 38–44 (2021).

Chattopadhyay, N. & Hulme, M. Evaporation and potential evapotranspiration in India under conditions of recent and future climate change. Agric. Meteorol. 87, 55–73 (1997).

Chen, X. et al. 50-year evapotranspiration declining and potential causations in subtropical Guangdong province, southern China. Catena 128, 185–194 (2015).

Oki, T. & Kanae, S. Global hydrological cycles and world water resources. Science 313, 1068–1072 (2006).

Kleidon, A. & Heimann, M. Assessing the role of deep rooted vegetation in the climate system with model simulations: mechanism, comparison to observations and implications for Amazonian deforestation. Clim. Dyn. 16, 183–199 (2000).

Piao, S. et al. Changes in climate and land use have a larger direct impact than rising CO2 on global river runoff trends. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 15242–15247 (2007).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. Investigating soil moisture–climate interactions in a changing climate: a review. Earth Sci. Rev. 99, 125–161 (2010).

Jasechko, S. et al. Terrestrial water fluxes dominated by transpiration. Nature 496, 347–350 (2013).

Zhang, K. et al. Vegetation greening and climate change promote multidecadal rises of global land evapotranspiration. Sci. Rep. 5, 15956 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Multi-decadal trends in global terrestrial evapotranspiration and its components. Sci. Rep. 6, 19124 (2016).

Liu, Y., Li, Z. & Chen, Y. Continuous warming shift greening towards browning in the Southeast and Northwest High Mountain Asia. Sci. Rep. 11, 17920 (2021).

Yu, L., Xue, Y. & Diallo, I. Vegetation greening in China and its effect on summer regional climate. Sci. Bull. 66, 13–17 (2021).

Tietjen, B. et al. Climate change-induced vegetation shifts lead to more ecological droughts despite projected rainfall increases in many global temperate drylands. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 2743–2754 (2017).

Gurmesa, G. A. et al. Retention of deposited ammonium and nitrate and its impact on the global forest carbon sink. Nat. Commun. 13, 880 (2022).

Bonan, G. B., Pollard, D. & Thompson, S. L. Effects of boreal forest vegetation on global climate. Nature 359, 716–718 (1992).

Piao, S. et al. Evidence for a weakening relationship between interannual temperature variability and northern vegetation activity. Nat. Commun. 5, 5018 (2014).

Shen, M. et al. Evaporative cooling over the Tibetan Plateau induced by vegetation growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 9299–9304 (2015).

Alkama, R. et al. Vegetation-based climate mitigation in a warmer and greener World. Nat. Commun. 13, 606 (2022).

Wang, X., Chen, Y., Li, Z., Fang, G. & Wang, Y. Development and utilization of water resources and assessment of water security in Central Asia. Agric. Water Manag. 240, 106297 (2020).

Chen, X. et al. Detecting significant decreasing trends of land surface soil moisture in eastern China during the past three decades (1979–2010). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos.121, 5177–5192 (2016).

Mankin, J. S. et al. Influence of internal variability on population exposure to hydroclimatic changes. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 044007 (2017).

Guan, Y. et al. Spatio-temporal variations in global surface soil moisture based on multiple datasets: intercomparison and climate drivers. J. Hydrol. 625, 130095 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Evapotranspiration on a greening Earth. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 626–641 (2023).

Cui, J. et al. Global water availability boosted by vegetation-driven changes in atmospheric moisture transport. Nat. Geosci. 15, 982–988 (2022).

Zhang, K. et al. A global dataset of terrestrial evapotranspiration and soil moisture dynamics from 1982 to 2020. Sci. Data 11, 445 (2024).

Miralles, D. G. et al. GLEAM4: global land evaporation and soil moisture dataset at 0.1° resolution from 1980 to near present. Sci. Data 12, 416 (2025).

Hoffmann, L. et al. From ERA-interim to ERA5: the considerable impact of ECMWF’s next-generation reanalysis on Lagrangian transport simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 3097–3124 (2019).

Gelaro, R. et al. The modern-era retrospective analysis for research and applications, version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 30, 5419–5454 (2017).

Berg, A., Sheffield, J. & Milly, P. C. D. Divergent surface and total soil moisture projections under global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 236–244 (2017).

Rodell, M. et al. Emerging trends in global freshwater availability. Nature 557, 651–659 (2018).

Rui, H., Beaudoing, H. & Loeser, C. README for NASA GLDAS Version 2 Data Products. (2016).

Piao, S. et al. Responses and feedback of the Tibetan Plateau’s alpine ecosystem to climate change. Chin. Sci. Bull. 64, 2842–2855 (2019).

Feng, H. & Zhang, M. Global land moisture trends: drier in dry and wetter in wet over land. Sci. Rep. 5, 18018 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. Evaluation of consistency among three NDVI products applied to High Mountain Asia in 2000–2015. Remote Sens. Environ. 269, 112821 (2022).

Ren, Z. et al. Comparing watershed afforestation and natural revegetation impacts on soil moisture in the semiarid Loess Plateau of China. Sci. Rep. 8, 2972 (2018).

Deng, Y. et al. Variation trend of global soil moisture and its cause analysis. Ecol. Indic. 110, 105939 (2020).

Sun, W. et al. Soil moisture-atmosphere interactions drive terrestrial carbon-water trade-offs. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 1–10 (2025).

Liang, H. et al. Soil moisture decline following the plantation of Robinia pseudoacacia forests: evidence from the Loess Plateau. Ecol. Manag. 412, 62–69 (2018).

Huang, H. et al. Contrasting impacts of irrigation and deforestation on Lancang-Mekong River Basin hydrology. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 1–10 (2025).

Xu, R. et al. Contrasting impacts of forests on cloud cover based on satellite observations. Nat. Commun. 13, 670 (2022).

Zhou, G. et al. Global pattern for the effect of climate and land cover on water yield. Nat. Commun. 6, 5918 (2015).

Wendland, W. M. Hydroclimatology. In Climatology. Encyclopedia of Earth Science. (Springer, Boston, MA, 1987). https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-30749-4_90.

Xie, X. et al. Revisiting dry season vegetation dynamics in the Amazon rainforest using different satellite vegetation datasets. Agric. Meteorol. 312, 108704 (2022).

Fan, Y., Li, H. & Miguez-Macho, G. Global patterns of groundwater table depth. Science 339, 940–943 (2013).

Zhao, Q., Zhu, Z., Zeng, H., Zhao, W. & Myneni, R. B. Future greening of the Earth may not be as large as previously predicted. Agric. Meteorol. 292–293, 108111 (2020).

Rigden, A. J., Mueller, N. D., Holbrook, N. M., Pillai, N. & Huybers, P. Combined influence of soil moisture and atmospheric evaporative demand is important for accurately predicting US maize yields. Nat. Food 1, 127–133 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Parazoo, N. C., Williams, A. P., Zhou, S. & Gentine, P. Large and projected strengthening moisture limitation on end-of-season photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9216–9222 (2020).

Yuan, W. et al. Increased atmospheric vapor pressure deficit reduces global vegetation growth. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax1396 (2019).

Fensholt, R., Rasmussen, K., Nielsen, T. T. & Mbow, C. Evaluation of earth observation based long term vegetation trends—intercomparing NDVI time series trend analysis consistency of Sahel from AVHRR GIMMS, Terra MODIS and SPOT VGT data. Remote Sens. Environ. 113, 1886–1898 (2009).

Zhang, Y., Song, C., Band, L. E., Sun, G. & Li, J. Reanalysis of global terrestrial vegetation trends from MODIS products: browning or greening?. Remote Sens. Environ. 191, 145–155 (2017).

Granger, C. W. J. Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica 37, 424–438 (1969).

Runge, J. et al. Inferring causation from time series in Earth system sciences. Nat. Commun. 10, 2553 (2019).

Seth, A. K., Barrett, A. B. & Barnett, L. Granger causality analysis in neuroscience and neuroimaging. J. Neurosci. 35, 3293–3297 (2015).

Moraffah, R. et al. Causal inference for time series analysis: problems, methods and evaluation. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 63, 3041–3085 (2021).

Papagiannopoulou, C. et al. A non-linear Granger-causality framework to investigate climate–vegetation dynamics. Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 1945–1960 (2017).

Schlesinger, W. H. & Jasechko, S. Transpiration in the global water cycle. Agric. Meteorol. 189–190, 115–117 (2014).

Pan, N. et al. Increasing global vegetation browning hidden in overall vegetation greening: insights from time-varying trends. Remote Sens. Environ. 214, 59–72 (2018).

Rogers, A. et al. A roadmap for improving the representation of photosynthesis in Earth system models. N. Phytol. 213, 22–42 (2017).

Cook, B. I., Mankin, J. S. & Anchukaitis, K. J. Climate change and drought: from past to future. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 4, 164–179 (2018).

Fensholt, R. et al. Greenness in semi-arid areas across the globe 1981–2007—an Earth observing satellite based analysis of trends and drivers. Remote Sens. Environ. 121, 144–158 (2012).

Wang, J. et al. Recent global decline in endorheic basin water storages. Nat. Geosci. 11, 926–932 (2018).

Costantini, E. A. C. et al. Soil indicators to assess the effectiveness of restoration strategies in dryland ecosystems. Solid Earth 7, 397–414 (2016).

Wu, X. et al. Higher temperature variability reduces temperature sensitivity of vegetation growth in Northern Hemisphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 6173–6181 (2017).

Wei, X. et al. Vegetation cover—another dominant factor in determining global water resources in forested regions. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 786–795 (2018).

Betts, R. A. Offset of the potential carbon sink from boreal forestation by decreases in surface albedo. Nature 408, 187–190 (2000).

Naumann, G. et al. Global changes in drought conditions under different levels of warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 3285–3296 (2018).

Liu, L. et al. Soil moisture dominates dryness stress on ecosystem production globally. Nat. Commun. 11, 4892 (2020).

Liu, L. et al. Soil water deficit promotes the effect of atmospheric water deficit on solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence. Sci. Total Environ. 720, 137408 (2020).

Li, X. & Xiao, J. A global, 0.05-degree product of solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence derived from OCO-2, MODIS, and reanalysis data. Remote Sens. 11, 517 (2019).

Wang, S., Zhang, Y., Ju, W., Qiu, B. & Zhang, Z. Tracking the seasonal and inter-annual variations of global gross primary production during last four decades using satellite near-infrared reflectance data. Sci. Total Environ. 755, 142569 (2021).

Sulla-Menashe, D., Gray, J. M., Abercrombie, S. P. & Friedl, M. A. Hierarchical mapping of annual global land cover 2001 to present: The MODIS Collection 6 Land Cover product. Remote Sens. Environ. 222, 183–194 (2019).

Green, J. K. et al. Regionally strong feedbacks between the atmosphere and terrestrial biosphere. Nat. Geosci. 10, 410–414 (2017).

Sohail, T., Zika, J. D., Irving, D. B. & Church, J. A. Observed poleward freshwater transport since 1970. Nature 602, 617–622 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.: W2412135) and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No.: XDB0720402). Meanwhile, we gratefully acknowledge the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No.: Y2022108).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L., Z.L. and Y.C. conceived of the original design of this paper. L.J., F.L., X.W., Y.L., C.L. and Patient Mindje Kayumba improve the structure of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Duminda Nayanaka and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Dushan Kumarathunge and Mengjie Wang. [A peer review file is available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Li, Z., Chen, Y. et al. Global greening drives significant soil moisture loss. Commun Earth Environ 6, 600 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02470-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02470-3

This article is cited by

-

Decoding vegetation resilience: NDVI trends and climate impacts in Indian agriculture

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (2025)